Chapter 8: The Sixth of June

Map 1: Situation in Europe 6 June 1944

The Invasion Is Launched

On 8 May General Eisenhower set D Day for Y plus 4, or 5 June. The plans were made (though changes would be introduced up to the last minute), the troops were trained, the preparatory softening up of the enemy was well under way. What remained was to get the men on ships and give the order to go. The vastly complicated process of organizing and equipping the assault units for embarkation began in April. It followed in general the pattern worked out in British exercises in the fall of 1943 which broke down the mounting into a series of movements bringing the troops successively nearer embarkation and at the same time providing for their equipment and assault organization. Unless the troops were already stationed near the south coast of England, they were moved first to concentration areas where they received special equipment, waterproofed their vehicles, and lost certain administrative overhead considered unessential during the assault. The second move brought them to marshaling areas located close to the embarkation points. There, final supplies were issued for the voyage, maps distributed, briefing for the operation accomplished, and the units broken down into boatloads to await the final move down to the ships.1

Force U (seaborne units of the VII Corps) was marshaled in the Tor Bay area and east of Plymouth; Force O (1st Division), in the area of Dorchester; Force B (29th Division), near Plymouth and Falmouth; and the early build-up divisions, the 9th Infantry and 2nd Armored Divisions, near Southampton. Marshaling areas for the airborne units were as follows: glider troops in the central counties between London and the Severn River; paratroopers of the 101st Division in the Newbury–Exeter area; paratroopers of the 82nd Division in the eastern half of England, north of London.2 (Map VII)

About 54,000 men, including the temporary housekeeping services of the entire 5th Armored Division, were required to establish and maintain installations for mounting the seaborne assault forces alone, and to perform services necessary to make them ready for sailing. To cook their meals, more than 4,500 new army cooks were trained during the first three months of 1944. To transport them and haul their supplies, over 3,800 trucks were operated by the Southern Base Section.

Through the first five months of 1944 individual and group assault training had continued, supplemented from January on by large-scale exercises designed to test not only assault techniques but coordination between the joint armies, smoothness of staff work in all phases of the operation, and techniques of mounting, marshaling,

loading, and unloading. These exercises culminated in two dress rehearsals for the invasion: exercise TIGER for Force U (VII Corps units) held at the end of April; the series of exercises, FABIUS, for Force O (1st Division), Force B (29th Division), and British assault and follow-up forces conducted in the early part of May.

The assault exercises were held at Slapton Sands on the coast of Devon southwest of Dartmouth under conditions simulating as closely as possible those expected in the actual operations. As a result of the exercises certain minor technical improvements were made, but the basic organization and the techniques as worked out at the Assault Training Center were unchanged.

Amid all the simulation there came one serious note of war. One of the convoys of exercise TIGER was attacked by two German E-boat flotillas totaling nine boats.3 Losses were heavier than those suffered by Force U during the actual invasion. Two LSTs were sunk and one damaged. About 700 men lost their lives.4 The loss of three LSTs to the OVERLORD assault lift was particularly critical in view of the general shortage of landing craft. General Eisenhower reported to the Combined Chiefs of Staff that the sinkings reduced the reserve of LSTs to nothing.5 The Germans realized that they had sunk landing craft but guessed that the craft had been participating in an exercise.6 The incident passed without repercussions.

After the TIGER and FABIUS rehearsals the assault troops returned to the marshaling areas to complete their last minute preparations and to wait. Troops of Force U had almost a month of waiting. It was a trying time for the men and a dangerous time for the fate of the invasion. Although troops were not briefed on operation OVERLORD until the last week in May, the fact that they were concentrated and ready to go and that they had just practiced the invasion maneuver with the organization actually to be used would have been sufficient information in the hands of enemy agents to jeopardize the operation. All troops were therefore sealed in the marshaling areas behind barbed wire and with a host of some 2,000 Counter Intelligence Corps men guarding them closely. The whole coastal area had been closed to visitors since April. Now, in addition, the camps themselves were isolated from all contact with the surrounding countryside. Camouflage discipline was more severely enforced during these weeks than at any time subsequently during actual operations. The German Air Force, though weak, was believed capable of damaging raids against troop concentrations and port areas. Actually, only one raid of any consequence did occur, when on the night of 30 May bombs were dropped in

Pre-invasion Scenes. Soldiers in mess line in one of the marshaling camps in southern England

Pre-invasion Scenes. Men and equipment being loaded on LSTs at Brixham.

a camp near Falmouth, causing a few casualties to an ordnance battalion. The enemy continued to miss his opportunities to disrupt the final preparations.

Loading of Force U, Force O, and Force B began on 30 May, 31 May, and 1 June, respectively, and all troops were aboard by 3 June. Force U craft were loaded mostly at Plymouth, Dartmouth, Torbay, Torquay, Poole, Salcombe, Brixham, and Yarmouth. They were divided into twelve convoys for the cross-Channel movement depending on their missions, assembly points, and speed. Force O was split into five convoys and the craft loaded in a relatively concentrated area including the ports of Portland, Weymouth, and Poole.7

Operation OVERLORD was ready.

On 29 May the senior meteorologist for SHAEF, Group Captain J. M. Stagg of the RAF, had drawn an optimistic long-range forecast of the weather to be expected in the first week of June. On the basis of that forecast all preparations had been made. General Eisenhower cabled General Marshall on Saturday, 3 June: “We have almost an even chance of having pretty fair conditions ... only marked deterioration ... would discourage our plans.”8 But marked deterioration was already in the cards. That Saturday evening Group Captain Stagg again came before the Supreme Commander and his commanders in chief who were meeting at Southwick House north of Portsmouth, the headquarters of Admiral Ramsay. Group Captain Stagg had bad news. Not only would the weather on 5 June be overcast and stormy with high winds and a cloud base of 500 feet to zero, but the weather was of such a nature that forecasting more than twenty-four hours in advance was highly undependable. The long period of settled conditions was breaking up. It was decided, after discussion, to postpone decision for seven hours and in the meantime let Force U and part of Force O sail on schedule for their rendezvous for the June D Day.

At 0430 Sunday morning a second meeting was held at which it was predicted that the sea conditions would be slightly better than anticipated but that overcast would still not permit use of the air force. Although General Montgomery then expressed his willingness to go ahead with the operation as scheduled, General Eisenhower decided to postpone it for twenty-four hours. He felt that OVERLORD was going in with a very slim margin of ground superiority and that only the Allied supremacy in the air made it a sound operation of war. If the air could not operate, the landings should not be risked. A prearranged signal was sent out to the invasion fleet, many of whose convoys were already at sea.9 The ships turned back and prepared to rendezvous twenty-four hours later.

On Sunday night, 4 June, at 2130 the high command met again in the library of Southwick House. Group Captain Stag reported a marked change in the weather. A rain front over the assault area was expected to clear in two or three hours and the clearing would last until Tuesday morning. Winds then of 25 to

Allied Invasion Chiefs

Left to right: General Bradley, Admiral Ramsey, Air Chief Marshal Tedder, General Eisenhower, General Montgomery, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, General Smith. This photograph was taken during a conference in early 1944.

31 knots velocity would moderate. Cloud conditions would permit heavy bombing during Monday night and Tuesday morning although there would be considerable cloudiness Tuesday. The cloud base at H Hour might be just high enough to permit spotting for naval gunfire. All this was good news, but it indicated weather that might be barely tolerable rather than ideal for the assault. After listening to the forecast Admiral Ramsay reminded the commanders that there was only half an hour to make a decision, and that if Admiral Kirk’s forces were ordered to sail for a D Day on Tuesday, 6 June, and were later recalled they would not be able to sail again for a Wednesday rendezvous, the last day for two weeks on which light and tidal conditions would be suitable for the assault.

Both Eisenhower and General Smith welcomed the break and felt the decision should be made to go in on Tuesday. The gamble that worried Smith was the possibility of not being able to spot naval fire but he thought it was still the best gamble to take. To call off the invasion now meant to wait until 19 June before it could be tried again. Troops would have to be disembarked with great risk to security, as well as to morale. The 19 June date would mean acceptance of moonless conditions for the airborne drops. Finally, the longer the postponement, the shorter the period of good campaigning weather on the Continent.

Still Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory was skeptical of the ability of the air force to operate effectively in the overcast predicted. Air Chief Marshal Tedder agreed that the operations of heavies and mediums were going to be “chancy.”

General Eisenhower refused the pessimistic view. “We have a great force of fighter-bombers,” he said, and then turning to General Montgomery he asked, “Do you see any reason for not going Tuesday”?

“I would say—Go!” Montgomery replied.

“The question,” Eisenhower pointed out, “[is] just how long can you hang this operation on the end of a limb and let it hang there.”

The discussion continued a few more minutes.

At 2145 Eisenhower announced his decision. “I’m quite positive we must give the order ... I don’t like it, but there it is ... I don’t see how we can possibly do anything else.”10

There remained still a possibility that the weather might become so much worse that the decision would have to be reversed. A final meeting was held shortly after midnight. Weather charts were studied again, but nothing had changed. The invasion was launched and through the choppy waters of the Channel the 5,000 ships and craft of the largest fleet ever assembled held to their carefully plotted courses toward the transport areas off the enemy coast.

When General Eisenhower left Southwick House before dawn of 5 June, he had made the last of a long series of planning and command decisions which through three and a half years had translated the idea of the cross-Channel attack into an operation of war. The war leaders, the high commanders, the planners with whom we have been so long concerned had no choice now but to sit back and wait. They had done what they could to insure that the men who crossed the Channel on 5 June 1944 should have the greatest possible chance of success at a cost as low as careful planning could set it. Long before the armada sailed, the Combined Chiefs of Staff had focused their attention far ahead of the battle of the beaches. The SHAEF staff similarly had long been working on plans for the later phases of the operation. The nearer H Hour approached, the more heavily and exclusively the responsibility for the invasion settled on the lower commanders.

In the narrative to follow, the great names drop out. Even Eisenhower and Montgomery appear but seldom. In their place will be the corps and division commanders, the colonels, the lieutenants, and the privates. For the few will be substituted the many, as the battlefield, so long seen as a single conceptual problem, becomes a confused and disparate fact-a maze of unrelated orchards and strange roads, hedgerows, villages, streams and woods, each temporarily bounding for the soldier the whole horizon of the war.

One may say of almost any successful operation that it carried out the plan, but this is to say little of how or why it succeeded. The Normandy assault was perhaps as thoroughly planned as any battle in the history of war. Nevertheless the fighting men went in trained to improvise battlefield solutions to the immediate problems facing them-how to take out an unseen machine gun in the hedgerows, how to outflank an enemy holed

up in a stone farmhouse. The fighting in these terms proceeded not according to plan but according to the trial and error of battle. It is to the narrative of this testing that we now turn.

While the Allied invasion force steamed across the Channel, the Germans in France, so long schooled for this moment, had no direct knowledge that it was at hand. The enemy was all but blind. There had been no air reconnaissance during the first five days of June. Naval patrols scheduled for the night of 5-6 June, along with the minelaying operations for that date, were canceled because of bad weather.

The stages of alert among the various commands in the west varied, reflecting both the nebulous character of such intelligence as was available and the lack of command unity. On 1 and 2 June German agents who had penetrated Resistance groups picked up twenty-eight of the 13 BC prearranged signals ordering the Resistance to stand by for the code messages that would direct the execution of sabotage plans. The central SS intelligence agency in Berlin reported these intercepts on 3 June to Admiral Doenitz and warned that invasion could be considered possible within the next fortnight. At the admiral’s headquarters they were not taken too seriously. It was thought that perhaps an exercise was in progress.11

On the evening of 5 June OB WEST and Fifteenth Army independently intercepted the “B” messages which at this time Fifteenth Army at least understood to be warnings of invasion within forty-eight hours.12 This was at 2215,13 precisely the hour at which the transport planes carrying troops of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division began taking off from airfields in England. What happened next is not altogether clear. While Fifteenth Army put its troops on the highest alert, Army Group B apparently took no action. On the basis of past experience Rommel’s staff considered it unlikely that the intercepts warned of an imminent invasion. Rommel himself was in Herrlingen at his home, on his way to visit Hitler at Obersalzburg; he was not immediately called back. Army Group B did not alert Seventh Army. In fact the routine daily orders from Seventh Army headquarters to subordinate corps on the evening of 5 June actually canceled a planned alert for that night.14 Perhaps the chief reason for the cancellation was that a map exercise, to which a number of division and lower commanders in Seventh Army had been invited, was scheduled for the morning of 6 June at Rennes. Whatever the reason, it is apparent that General Dollmann believed on the night of 5 June that there was less cause for alarm than on many a previous night in May when his troops had been alerted.

The net effect on German preparedness of the intercepted warnings to the Resistance was therefore slight. Seventh Army was alerted only in the sense that it was in the same state of “defensive

readiness” that it had been in all through the spring. The Resistance messages of the evening of 5 June may have persuaded OB WEST that invasion was imminent, although there is evidence that Rundstedt’s intelligence officer at least rejected the warning on grounds that it would be absurd for the Allies to announce their invasion in advance over the BBC.15 In any case, a last-minute alert of the supreme headquarters in such vague terms was of little value for the command. It gave no indication of where or precisely when the Allies would strike; reconnaissance, moreover, could not be put out in time to answer these questions.

As for the Navy, it was, on 5 June, thoroughly complacent. German naval experts had calculated that Allied landings would be possible only in seas of less than intensity 4,16 with a wind force up to 24 knots and a visibility of at least three sea miles. These conditions were not being met on 5 June.17 Lacking weather-reporting stations to the west whence most of the Channel weather came, the German meteorologists were unable to make reliable predictions.18 Weather planes flew out over the North Sea daily to points west of Ireland, but the data provided by their observations were of limited usefulness. The Germans could not have forecast the break in the weather which Group Captain Stagg reported to General Eisenhower.19 Although there is no evidence that meteorologists advised German commanders that invasion on 6 June was impossible, it is clear that the generally unfavorable wind and sea conditions contributed to reducing the enemy’s alertness.20

This was particularly true of the naval command. Lulled into a sense of security by the weather and the judgment that the Allies had not yet completed essential preparatory bombardment of the coastal fortifications, Admiral Krancke received reports of the SOE intercepts on 5 June without alarm. Notice of the BBC affair was faithfully transcribed in his war diary for 6 June together with his assurances that nothing was likely to happen-all under the general heading: “Large-scale enemy landing in the Seine Bay.21

German Field Commanders: General von Schlieben

General Marcks

General Geyr von Schweppenburg

General Dollmann

The Airborne Assault

The time and place at least of the “large-scale landing” caught the Germans wholly by surprise. Seventh Army’s first knowledge that anything was afoot was a series of reports in the early morning hours of 6 June that Allied paratroopers were dropping from the skies over Normandy. At 0130 Lt. Col. Hoffmann, commander of the 3rd Battalion, 919th Regiment of the 709th Division) was at his headquarters in St. Floxel east of Montebourg. He heard aircraft approaching. The sound indicated great numbers, and, as he listened during the next hour, it seemed to him to swell louder and louder. At 0200 six airplanes flying, he thought, at about 500 feet approached the headquarters shelter and released parachutists in front of and above it. In a few minutes Hoffmann’s staff and security guards were heavily engaged with paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division in one of the opening skirmishes of the battle for Normandy.22

News of the landings spread fast. At 0215 Seventh Army ordered the highest state of alarm through the LXXXIV Corps sector. The alarm was passed at once by wire to all Army, Navy and Air Force units in the corps area. At 0220 Naval Commander Normandy (Konteradmiral Walther Hennecke)23 reported paratroopers near the Marcouf battery. During the next five minutes additional reports came in of landings in the sector of the 716th and 711th Divisions. Before three o’clock LXXXIV Corps had taken its first prisoner. The situation was still obscure, but, as reports piled in, something of the extent and scale of the operation became visible. Generalmajor Max Pemsel, Seventh Army chief of staff, had already (by 0300) concluded that the long-heralded major invasion had begun, and had correctly located the points of main effort near Carentan and Caen.24 His judgment, however, was at this time a minority report. Field Marshals Rundstedt and Sperrle and Admiral Krancke as well as Rommel’s chief of staff, Generalleutnant Hans Spieled, all thought they were probably experiencing the diversionary operation which had been expected in the Seventh Army area while the Allies prepared to strike the main blow against Fifteenth Army. But, whatever the larger estimate of the situation, local measures could be and were promptly taken. The 91st Division in reserve in the Cotentin was released to Seventh Army, attached to LXXXIV Corps, and, together with the 709th Division, was ordered to counterattack. There was actually little else to be done. All units in the Cotentin had been briefed to expect airborne operations. The meeting engagement was inevitably the individual problem of these units.

The situation on the American side was similar. The first actions of all airborne units in the Cotentin on D Day were attempts by small groups of men to carry out in the fog of the battlefield their own small portions of the assigned plan. There could be little over-all direction from above. And, in fact, little information

Parachute Troops marching onto airfield on evening of 5 June.

got through to corps and army as to what was happening.25

By the revised VII Corps field order of 28 May both U.S. airborne divisions were to land in the eastern half of the peninsula between Ste. Mère-Eglise and Carentan, establishing a beachhead from which the corps would push west and north to the capture of Cherbourg. The six parachute regiments of the two divisions, which together with organic supporting units numbered over 13,000 men, were loaded in 822 transport planes at nine airfields in England. They began taking off before midnight to fly routes calculated to bring the first serials in from the west side of the Cotentin Peninsula and over the designated drop zones between 0115 and 0130. The main flights were preceded by pathfinder planes that were to land paratroopers to mark the drop zones. Glider reinforcements would be brought in at dawn and again at dusk on landing zones that the paratroopers were expected to have cleared of the enemy. The whole airborne operation was by far the largest and most hazardous ever undertaken, and thousands of American lives depended on its success.26

The primary mission of the 101st Airborne Division was to seize the western edge of the flooded area back of the beach between St. Martin-de-Varreville and Pouppeville. Its secondary mission was to protect the southern flank of VII Corps and be prepared to exploit southward through Carentan. The latter task was to be carried out by destroying two bridges on the main Carentan highway and the railroad bridge west of it, by seizing and holding the la Barquette lock, and finally by establishing a bridgehead over the Douve River northeast of Carentan.

Two parachute regiments less one battalion, the 502nd and the 506th(-), were assigned the primary mission. The 502nd Parachute Infantry, with the 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion attached, was to drop near St. Martin-de-Varreville, destroy the enemy coastal battery there, secure the two northern beach exits, and establish a defensive line tying in the division’s north flank with the 82nd Airborne Division to the west. The 506th Infantry would seize the two southern exits.

The four battalion serials of the 502nd Infantry came in ten minutes apart led by the 2nd Battalion and regimental headquarters. The leading planes, scattered by clouds and flak, dropped the majority of the 2nd Battalion outside their assigned zone. (Map IX) The battalion as a result spent most of the day assembling and, as a unit, took no part in the D-Day fighting. The regiment’s planned artillery support did not materialize. Only one of the six howitzers of the 377th Field Artillery Battalion was recovered after the drop, and the fifty men of the battalion who assembled during the day fought as infantry in scattered actions.27

The commander of the 3rd Battalion, 502nd, Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, dropped east of Ste. Mère-Eglise. (See Map VIII.) He began then to make his way toward St. Martin-de-Varreville. Out of the darkness, toy “crickets” snapped as paratroopers identified themselves and began assembling in groups. The groups were generally miscellaneous at first. The men looked only for company and leadership. Seventy-five men, including some paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division, gathered in this way under Colonel Cole and moved steadily toward the coast. Except for an encounter with a small enemy convoy on the way, in which some Germans were killed and ten taken prisoner, the group had no trouble reaching its objective. Discovering that the guns of the St. Martin coastal battery had been removed and that the position was deserted, Cole went on to Audouville-la-Hubert where his men established themselves at the western end of the causeway without a fight.28 About

two hours later, at 0930, the enemy began retreating across the causeway from the beach. The paratroopers, lying in wait, shot down fifty to seventy-five and at 1300 made contact with the 8th Infantry (4th Division). They had suffered no casualties. Cole, having completed his mission, remained in the area to collect and organize his battalion. By the end of the day he had about 250 men. With this group he was ordered into regimental reserve near Blosville for the next day’s operations.

The 1st Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. Patrick J. Cassidy), had a much harder fight for its objectives. Colonel Cassidy, landing about in the center of the battalion zone near St. Germain-de-Varreville, collected a small force mostly of his own men and moved toward the stone buildings on the eastern edge of Mésières which were thought to be occupied by the German unit manning the St. Martin coastal battery. Without opposition the battalion secured the crossroads west of St. Martin near which the building stood. Taking stock of his position there, Colonel Cassidy found that both the northern exits for which the regiment was responsible were clear. He then made contact with a group of forty-five men of the battalion who had assembled north of his own position and ordered them to establish a defensive line at Foucarville. The situation to the west of St. Martin, however, remained obscure. Colonel Cassidy decided to keep a portion of his force (nominally a company) in reserve to block any enemy attempt to break through from the west to the beaches. A group of about fifteen men was sent to clean out the buildings on the eastern edge of Mésières. This fight was conducted almost single-handedly by S/Sgt. Harrison Summers. Summers rushed the buildings one by one, kicked in the doors, and sprayed the interiors with his Tommy gun. On occasion he had the assistance of another man, but it was his drive and initiative that kept the attack going. When the last building was cleared in the afternoon, about 150 Germans had been killed or captured.29

Near the close of this action Lt. Col. John H. Michaelis, regimental commander, arrived in the area with 200 men. Cassidy was thus free to complete his D-Day mission to cover the north flank of the regiment and tie in with the 82nd Airborne Division on the left. While the fight near Mésières was in progress the men of the 1st Battalion whom Colonel Cassidy had sent to Foucarville in the morning had succeeded in establishing four road blocks in and around the town and had trapped and largely destroyed a four-vehicle enemy troop convoy. Despite this early success the road blocks were threatened all day with being overrun by a superior enemy force that occupied prepared positions on a hill to the northwest.

The American situation was not immediately improved by Cassidy’s move north, since he came up west of Foucarville in order to carry out the plan of tying in at Beuzeville-au-Plain with the 82nd Airborne Division. He ran into trouble there. The company ordered to Beuzeville-au-Plain mistook the hamlet of le Fournel for its objective and there became involved in three separate platoon

fights which proceeded in some confusion until dark. The troops then withdrew to the south where they remained under enemy pressure during the night. Since contact was not made with the 82nd Airborne Division, Cassidy committed the reserve company on the left and moved up some spare riflemen to fill the gap between le Fournel and the road blocks around Foucarville. Even so the whole line remained very weak, and the regimental commander, having already decided to pass the 2nd Battalion through the 1st on the following day, ordered Colonel Cassidy to pull back and dig in.

During the night the Germans facing the battalion’s right flank at Foucarville unexpectedly decided to surrender, apparently because the increasing volume of American machine gun and mortar fire led them to overestimate the battalion’s strength. Eighty-seven Germans were taken prisoner and about fifty more shot down as they attempted to escape.

Here as elsewhere in the 101st Airborne Division’s early contacts with the enemy, it seems that the German dispersion of units in small packets to garrison villages and strong points took no account of the splintering effect of airborne landings in their midst, even though the enemy command expected just such landings. The isolated German units, apparently out of contact with their parent outfits, ignorant of what was occurring as well as of what German countermeasures were in the making, were prone to fancy themselves about to be overwhelmed whenever American fire was brought to bear on them with any persistence. The attackers at least had the psychological advantage of knowing the large things that had been planned, even though they seldom knew what was actually happening beyond the field or village in which they found themselves.

The two beach exits south of the zone of the 502nd Infantry were the responsibility of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (Col. Robert F. Sink). The 506th (less the 3rd Battalion) was to land between Hiesville and Ste. Marie-du-Mont and seize the western edge of the inundated area between Audouville-la-Hubert and Pouppeville. The 3rd Battalion, dropping just south of Vierville and charged with defending the Douve River line in the regiment’s sector, was to seize two bridges at le Port and establish a bridgehead there for subsequent exploitation southward.

Like the 502nd, the 506th experienced a badly scattered drop, but had rather better luck in assembling rapidly. Within two hours of landing, about ninety men of regimental headquarters and fifty men of the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. William L. Turner) had assembled in the regimental zone. Colonel Sink established his command post at Culoville. At the same time the 2nd Battalion (Lt. Col. Robert L. Strayer), despite a landing completely out of its zone in the sector of the 502nd Parachute Infantry to the north, succeeded in assembling rapidly about 200 of its men. Strayer had the principal regimental mission of securing the southern beach exits at Houdienville and Pouppeville. Before dawn his men headed south toward their objectives. They ran into opposition on the same road over which the 1st Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry, had passed shortly before. Delayed all morning by enemy machine guns, they did not reach

their first objective, Houdienville, until early afternoon, after the seaborne troops were already through the exit and proceeding inland.

Meanwhile Colonel Sink, at Culoville, knowing nothing of the 2nd Battalion’s movements, decided to send his reserve, the 1st Battalion under Colonel Turner, to carry out a part of the mission. Turner’s “battalion” of fifty men was ordered to Pouppeville. Again relatively light enemy opposition succeeded in harassing the march and delaying for several hours Turner’s arrival on his objective.

In the course of the delay a third unit was sent on the same mission by the division commander, Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor,30 who had no knowledge of the two previous moves. The 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. Julian Ewell), had been designated to land as division reserve with the additional task of protecting the glider landing zone northwest of Hiesville. Although three planes of the 3rd Battalion serial were shot down with the loss of three-quarters of their personnel and other planes were scattered by fog and flak, enough carried out their scheduled drops so that about 300 men of the battalion and of the division headquarters were able to assemble quickly and establish the division command post as planned near Hiesville. From there Colonel Ewell, with a group of about forty men from the line companies and some miscellaneous headquarters personnel, was sent at 0600 to clear the Pouppeville beach exit.

At about 0800 Ewell’s men reached Pouppeville and attacked to clean it out. The enemy force of approximately sixty to seventy men of the 1058th Regiment (91st Division)31 did not offer determined resistance, but it was nevertheless a slow task for the numerically inferior Americans to fight them house to house. It was noon before the local German commander surrendered. The Americans had suffered eighteen casualties, while inflicting twenty-five on the enemy and taking thirty-eight prisoners. The rest of the enemy in Pouppeville retreated toward the beach where they were caught by the advancing U.S. seaborne forces, and at last surrendered to the 8th Infantry. The first contact between seaborne and airborne forces was made at Pouppeville between Colonel Ewell’s men and the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry (Lt. Col. Carlton O. MacNeely).

Throughout D Day Colonel Sink at the 506th regimental headquarters felt wholly isolated and almost alone on the Cotentin Peninsula. Most of the time he was out of touch with his own battalions and with the division; he had little information about the enemy, and his headquarters was involved in scattered fights for its own security. The regiment unknowingly had set up in the midst of a small hornet’s nest. In the Ste. Marie-du-Mont area was the entire 2nd Battalion of the 191st Artillery Regiment which had been committed to coastal defense in the 709th Division sector.32 The battalion headquarters was in Ste. Marie

and the three batteries, each with four 105-mm. howitzers, were all in the immediate vicinity. Four of the pieces were captured near Holdy by groups of the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry. The enemy battalion headquarters was overrun by combined action of the 506th Infantry and elements of the 4th Division later in the day.33 For the most part, however, Colonel Sink had no men to spare either to clear the enemy from his immediate vicinity or even to reconnoiter to make contact with other friendly units. He believed it necessary to keep together his handful of men to protect the rear of the units engaged in clearing the causeways and to provide a nucleus for concentration of the regiment. The group maintained itself, fighting off enemy riflemen who twice during the day closed in among the surrounding hedgerows. In the evening, with forces of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, Colonel Sink controlled about 650 men.

The hedgerows, which bottled up Colonel Sink’s men in apparent isolation despite the nearness of friendly units, were to become the most important single preoccupation of American fighting men during their next two months in Normandy and would remain as their most vivid memory of the land. These hedgerows, ubiquitous throughout the Cotentin and the bocage country, were earth dikes averaging about four feet in height and covered with tangled hedges, bushes, and even trees. Throughout the entire country they boxed in fields and orchards of varying sizes and shapes, few larger than football fields and many much smaller. Each hedgerow was a potential earthwork into which the defenders cut often-elaborate foxholes, trenches, and individual firing pits. The dense bushes atop the hedgerows provided ample concealment for rifle and machine gun positions, which could subject the attacker to devastating hidden fire from three sides. Observation for artillery and mortar fire was generally limited to a single field, particularly in the relatively flat ground of the beachhead areas. Each field thus became a separate battlefield which, when defended with determination, had to be taken by slow costly advances of riflemen hugging the hedgerows to close with the enemy with rifle and grenade. Both Americans and Germans complained that the hedgerows favored the other side and made their own operations difficult. In fact, the country was ideal for static defense and all but impossible for large coordinated attacks or counterattacks. The chief burden of the fighting remained with the individual soldier and the advance of his unit depended substantially on his own courage and resourcefulness, and above all on his willingness to move through machine gun and mortar fire to root the enemy out of his holes.

The 101st Airborne Division within a relatively few hours of landing had secured the western edge of the inundated area west of UTAH Beach. The task was accomplished, not quite according to plan, but on time and with much smaller cost than anyone had thought possible before the operation.34 The remaining

Hedgerow Country. Aerial view of typical hedgerow terrain in Normandy

Hedgerow Country. Infantry crouching behind the bushes atop hedgerow.

part of the division’s D-Day task was to seize and occupy the line of the Douve River on either side of Carentan, initially to protect the southern flank of VII Corps and later to drive southward through Carentan to weld together the VII and V Corps beachheads.

The 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, was to drop south of Vierville, seize two bridges over the Douve at le Port, and establish a bridgehead on the south bank of the river. Its mission came perilously near failure at the outset. The enemy, fully alerted before the drop, not only put up a heavy antiaircraft barrage but illuminated the drop zone by setting fire to an oil-soaked building near by. Paratroopers that landed in the area were greeted by a concentration of machine gun bullets and mortar shells. Others, experiencing delayed drops, came down in or near the swamplands east of the drop zone.

The battalion S-3, Capt. Charles G. Shettle, landing near Angoville-au-Plain, collected two officers and twelve men and then proceeded at once across the flat marshy river plain toward his objective. By the time he reached the bridge at Brevands at 0430 he had picked up a total of thirty-three men, and was there reinforced by twenty more a little later and by another forty during the night of 6-7 June. Shettle’s group established themselves first on the southeast bank of the river but could not hold the position in the face of increasing enemy machine gun fire. They therefore withdrew across the river and dug in on the northwest bank. During the day the enemy did not counterattack; in the middle of the night he made only a halfhearted push toward the bridge, from which he readily backed off when the Americans opened fire. The situation at Brevands on D Day paralleled that on the northern flank where the 502nd Parachute Infantry was also holding a tenuous line facing superior enemy forces. Both defenses succeeded chiefly by grace of the enemy’s reluctance to leave his prepared positions and attack, and his confusion as to American strength and intentions. It is worth observing, however, that the Carentan canal was the boundary between the 709th and 352nd Divisions. The latter, located to the south, would not attack across the canal without orders from corps. Corps, in fact, had ordered the reserve unit, the 6th Parachute Regiment to make such an attack from the south but it did not at once come into action.35

Completion of the 101st Division’s defense of the Douve River line west to St. Côme-du-Mont was the task of the 501st Parachute Infantry (Col. Howard R. Johnson) less the 3rd Battalion. The regiment’s missions in detail were to seize the lock at la Barquette, blow the bridges on the St. Côme-du-Mont-Carentan road, take St. Côme-du-Mont if possible, and destroy the railroad bridge to the west. Of these objectives the lock at la Barquette had a special importance for the planners.

The purpose of the lock was to permit the controlled flow of the tide up the river channel so as to maintain a depth sufficient for barge navigation as far upstream as St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. If the lock were destroyed the swamplands of the Douve and Merderet would suffer erratic tidal flooding. On the other

hand, partial obstruction of the lock would permit controlled flooding of the same area by backing up the river flow. The latter kind of inundation had been effected by the Germans before D Day. Capture of the lock, it was believed, was tactically important in order that VII Corps might control the Douve and Merderet inundations, which together constituted a barrier to military movement across the whole eastern half of the base of the peninsula. The importance was stressed even though it was recognized that flooding and draining of the area were slow processes and that the natural swamps and flat bottomlands, crisscrossed with drainage ditches, in themselves formed a convincing obstacle to vehicle movement and a grave hindrance to infantry maneuver.

Just before D Day the drop zone for the 501st Parachute Infantry (and the 3rd Battalion, 506th) had been shifted about a mile and a half southeast-from the vicinity of Beaumont to east and south of Angoville-au-Plain-in order to bring the paratroopers down nearer their objective and avoid the antiairlanding obstacles which last-minute reconnaissance had discovered on the original drop zone. The change does not seem to have been responsible for the inaccuracy of the drop. The scattering of the 1st Battalion planes resulted from the same conditions of fog and enemy antiaircraft fire which had affected all the other airborne units and was certainly no more serious. What was serious, however, was the loss in the drop of the entire battalion command. The commanding officer was killed; the staff and all the company commanders were missing from the first critical battles.

Colonel Johnson, the regimental commander, by good fortune landed about where he was supposed to and, in the process of moving southward toward la Barquette, managed to collect some 150 men of miscellaneous units with whom he set out to accomplish his mission. The first step went well. Before the enemy had been fully alerted, a portion of the force crossed the lock and dug in on the far side. They seemed relatively secure there as the enemy made no attempt to press in on them. Colonel Johnson therefore decided to try to get the Douve bridges to the west. With fifty men he first went north to Basse Addeville, where he had ascertained that a considerable number of paratroopers had assembled under Maj. Richard J. Allen, the regimental S-3.- Although Allen’s men were already in contact with the enemy to the north and west, it proved possible to assemble about fifty of them in the early afternoon to return with Colonel Johnson to la Barquette. Met by intense enemy artillery, mortar, and small arms fire, chiefly from the rear, the force called for naval fire support through a naval shore fire control officer who had initially joined Major Allen’s unit at Addeville. Salvos from the 8-inch guns of the Quincy adjusted on enemy positions around St. Côme-du-Mont caused almost immediate slackening of the enemy fire. At about 1500 Major Allen was ordered to bring the rest of his force to the lock and he joined Colonel Johnson an hour or two later.36

Even with this support, however, it proved impossible to advance westward to the Douve bridges. The 3rd Battalion of the 1058th Regiment held St. Côme-du-Mont and the surrounding ground in force and strongly resisted with fire every move in that direction. The opposition here in the sector of the 91st Division and immediately to the south where the 6th Parachute Regiment held Carentan and the road and rail bridges was much more determined than anywhere in the coastal sector held by the 709th Division.

The unexpected strength of the enemy in the Carentan—St. Côme-du-Mont area had been discovered by the 2nd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. Robert A. Ballard), shortly before Colonel Johnson tried unsuccessfully to move westward. Colonel Ballard had assembled parts of his lettered companies and his battalion staff between Angoville-au-Plain and les Droueries. Since his assigned mission was the destruction of the Douve bridges above Carentan, he began at once an attack toward St. Côme-du-Mont. The companies, of about thirty men each, ran into strong opposition in the hamlet of les Droueries, which they had attacked frontally in the belief that not more than an enemy platoon faced them. After they were turned back initially, a renewed flanking attack was meeting some success when Colonel Ballard was ordered by Colonel Johnson to move to la Barquette to participate in the drive from that point toward the Carentan highway. The 2nd Battalion disengaged but, in attempting to move south through Addeville, was stopped almost immediately by heavy fire from the same enemy force that had opposed the attack on les Droueries. Ballard’s men remained during the night in close contact with the enemy. In the meantime, Colonel Johnson, abandoning for the time the attempt to get to the Douve bridges, consolidated the position at la Barquette, deepening the southern bridgehead, pushing out his flanks, and maintaining contact with the 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, on the east. Patrols during the night of 7 June were sent out to try to find the 506th Regiment and division headquarters, but they did not succeed and the southern line remained isolated and precariously held by groups equivalent to about three companies instead of three battalions as planned.

By the end of D Day the 101st Airborne Division had assembled only about 2,500 of the 6,600 men-who had dropped during the early morning hours.37 They were distributed in mixed units of varying size. But despite the handicaps of scattered landings and heavy losses in both men and equipment the division had carried out the most important of its D-Day tasks. Above all, the paratroopers had succeeded in clearing the way for the move of the seaborne forces inland. This was the task which had been considered so vital to the whole Allied invasion plan as to warrant the extraordinary

risk of airborne landings in heavily defended enemy territory. If the division’s defensive line north and south was weak, that weakness was for the moment balanced by the enemy’s failure to organize concerted counterattacks.

The position of the 82nd Airborne Division (Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway)38 on the west was cause for far greater concern both to General Ridgway and to the Allied command. Landing on the edge of the assembly area of the German 91st Division, it met more determined opposition in the early stages. It suffered more seriously also from scattered drops which left two of its regiments unable to assemble in sufficient force to carry out their missions.

By the revised plan of 28 May, Ridgway’s division was ordered to drop astride the Merderet River, clear the western portion of the beachhead area between the sea and the Merderet and from the Douve River north to Ste. Mère-Eglise, and establish a bridgehead on the west bank of the Merderet. One parachute regiment (the 505th) was to capture Ste. Mère-Eglise, secure crossings of the Merderet near la Fière and Chef-du-Pont, and establish a defensive line north from Neuville-au-Plain to Beuzeville-au-Plain to tie in with the 502nd Parachute Infantry of the 101st Airborne Division. The other two regiments (507th and 508th), dropping west of the river, were to consolidate the two 505th bridgeheads and push out a defensive line about three miles westward, anchored on the south at the crossroads just west of Pont l’Abbé and thence extending north in an arc through Beauvais. The 507th Parachute Infantry would defend the line of the Douve, destroying bridges at Pont l’Abbé and Beuzeville-la-Bastille. Both regiments would be prepared to attack west in the direction of St. Sauveur-le Vicomte.

Only one of the 82nd Airborne Division’s missions was carried out according to plan: the capture of Ste. Mère-Eglise. Success at Ste. Mère-Eglise was due in part to the exceptionally good drop of the 505th Parachute Infantry northwest of the city. (Map X) Most of the regiment’s planes, though initially scattered like the others, were able to circle back and release the paratroopers over the drop zone which pathfinders had clearly marked. In addition the regiment had the good fortune to come down in an area devoid of enemy. The 3rd Battalion (Lt. Col. Edward C. Krause), which was to take the town of Ste. Mère-Eglise, rapidly assembled about a quarter of its men and moved out in the early morning hours. Counting on speed and surprise, Colonel Krause ordered his men to enter the town without a house-to-house search and to use only knives, bayonets, and grenades while it was still dark so that enemy gunfire could be spotted. The enemy was caught off balance and before dawn the town had fallen—the first prize for American arms in the liberation of France. Resistance had been slight: when Ste. Mère-Eglise was cleared Krause’s men counted only ten enemy dead and about thirty prisoners. The battalion cut the main Cherbourg

communications cable and established a perimeter defense of the town.

The 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. Benjamin H. Vandervoort), in the meantime had assembled half of its men and was moving northward to establish the regimental defense line through Neuville-au-Plain and Bandienville. (See Map VIII.) At 0930 the enemy counterattacked Ste. Mère-Eglise from the south and the regimental commander, Col. William E. Ekman, ordered his 2nd Battalion back to aid in the defense. Before turning back Colonel Vandervoort detached a platoon under Lt. Turner B. Turnbull and sent it to organize a defense at Neuville which was reported to be lightly held by the enemy. Turnbull moved through the town without opposition and deployed his men on the high ground north of the town. He was hardly in position before the enemy attacked with a force outnumbering the defenders about five to one. The platoon fought stubbornly and for eight hours held its ground. The small action had a significance which Turnbull did not realize at the time. The fight at Neuville kept the enemy in the north at arm’s length while the defenders of Ste. Mère-Eglise beat off the simultaneous enemy attack from the south. The cost of the platoon’s gallant stand was heavy. Only sixteen of the forty-two men who had gone to Neuville-au-Plain survived to be withdrawn late in the afternoon to rejoin their battalion.

In Ste. Mère-Eglise the 2nd Battalion of the 505th on its arrival at about 1000 took over the northern half of the perimeter defense, permitting the 3rd Battalion to strengthen its position on the south. Two companies were held in reserve inside the town. By agreement between the battalion commanders, Colonel Krause took charge of the defense. The first enemy thrust up the Carentan road, made in strength of about two companies supported by some armor, was repulsed. Krause then ordered a counterattack. Company I with eighty men was instructed to move out south, turn east, and hit the flank of the enemy, whose main positions were astride the highway. The attack, however, hit only a single enemy convoy moving southward. Having destroyed the convoy with grenades, Company I returned to Ste. Mère-Eglise. The enemy made no further serious effort during the day to dislodge the Americans.39

The prompt occupation of Ste. Mère-Eglise and its defense were a boon for which the 82nd Airborne Division had increasing reason to be grateful as the day’s actions along the Merderet River developed. The establishment of bridgeheads over the Merderet was the mission of the 1st Battalion of the 505th Parachute Infantry, attacking from the regiment’s drop zone east of the river. Ultimate success in this mission, however, depended on the ability of the 507th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments to occupy the west bank of the river in force. The 507th and 508th drop zones lay in the triangle at the confluence of the Douve and Merderet Rivers—an area of about twelve square miles—and along the outer perimeter of the VII Corps planned beachhead. Presence of the enemy in the scheduled drop zones prevented the pathfinders from marking them, and the pilots of the two regimental serials, looking in vain for the markers, in most cases delayed

flashing the jump lights until they had overshot the zones. Both regiments were thus widely dispersed and many paratroopers, heavily laden with equipment, dropped in the swamplands along the river.

Absorbed naturally with the basic problem of assembling, these paratroopers tended to collect along the embankment of the main railroad from Cherbourg to Carentan, both because it was high dry ground and because it was a recognizable terrain feature. By following this embankment south, they crossed the river and arrived in the vicinity of la Fière with the river between them and their objectives. The only large group which, under command of Brig. Gen. James A. Gavin, Assistant Division Commander, tried to push down along the edge of the swamps on the west bank of the river was delayed in starting until dawn by vain efforts to recover equipment from the swamps. With daylight, enemy fire west of the river became intense. Gavin therefore had to give up the attempt and moved his men on down the embankment to join the others west of Ste. Mère-Eglise.40

By the middle of the morning 500 to 600 men of miscellaneous units had gathered at la Fière, which was one of the two known crossings of the Merderet in the 82nd Airborne Division zone. The la Fière crossing was an exposed narrow causeway raised a few feet above the river flats and extending 400 to 500 yards from the bridge over the main river channel to the gently rising hedgerow country of the west shore.

Two of the first groups on the scene, portions of Company A of the 505th and a group mostly of the 507th Parachute Infantry under Lt. John H. Wisner, had tried to rush the bridge in the early morning but were repulsed by machine gun fire. When General Gavin arrived, he decided to split the la Fière force and sent seventy-five men south to reconnoiter another crossing. Later, receiving word that the bridge at Chef-du-Pont was undefended, he took another seventy-five men himself to try to get across there. The groups remaining at la Fière made no progress for several hours. Then General Ridgway, who had landed by parachute with the 505th, ordered Col. Roy Lindquist, the commanding officer of the 508th Parachute Infantry, to organize the miscellaneous groups and take the bridge.41

In the meantime west of the river about fifty men of the 2nd Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry, had collected under the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Charles J. Timmes. Shortly after the drop, Timmes had passed through Cauquigny, the tiny village at the west end of the la Fière causeway. But he did not stay. Hearing firing in the direction of Amfreville, he reckoned that paratroopers were attacking the village from the north and decided to support the attack by advance from the east. His estimate proved wrong; the enemy firing was actually directed against his own group. Unable to proceed toward the village Timmes withdrew his men to a

position along the river east of Amfreville and began to dig in. When the position was organized about midmorning, he sent a patrol of ten men back to Cauquigny to establish a fire position to dominate the west end of the la Fière causeway. The patrol set up a machine gun in the Cauquigny church, and awaited developments.42

At noon the forces around la Fière gathered for a coordinated three-company attack. In two hours one company under Capt. F. V. Schwarzwalder succeeded in carrying the attack across the causeway, and established contact with Timmes’ patrol. The way was then open to consolidating the bridgehead and completing one of the most important of the 82nd Airborne Division’s missions. The initial success, however, was not followed up. Probably because it was difficult in the hedgerow country for any unit to tell quickly what was going on beyond its immediate limited observation, the first crossing by about seventy-five men was not immediately reinforced. Furthermore Schwarzwalder’s company, instead of holding on the west bank, decided to proceed on to Amfreville to join the 2nd Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry, to which most of the men belonged. As Schwarzwalder move out, the enemy began to react to the initial American attack with artillery, small arms fire, and at last a tank sally.43 It was in the middle of this counterattack that belated American reinforcements arrived on the west bank and were immediately disorganized and beaten back. The bridge was lost. Colonel Timmes’ group east of Amfreville reinforced by Schwarzwalder’s company was isolated under heavy and continuing enemy pressure which effectively prevented it for the next two days from any further active attempts at accomplishing the division’s mission. The enemy tried to follow up his advantage with attacks across the causeway. These netted him only temporary footholds on the east bank but during the day compelled the Americans to bring back most of the troops sent earlier to probe out crossings of the river to the south.

While the la Fière bridge was won and lost, the attempt to cross at Chef-du-Pont about two miles south had reached a temporary deadlock, as a relatively small number of Germans dug in along the causeway tenaciously resisted all efforts to dislodge them.44 Late in the afternoon, after most of the paratroopers had been recalled to strengthen the la Fière position, the under-strength platoon left at Chef-du-Pont under Capt. Roy E. Creek was threatened with annihilation by an enemy counterattack. Under heavy direct fire from a field piece on the opposite bank and threatened by German infantry forming for attack on the south, Creek’s position seemed desperate. At that moment a glider bearing an antitank gun landed fortuitously in the area. With this gun the enemy was held off while about a hundred paratroopers, in response to Creek’s plea for reinforcements, came down from la Fière. The reinforcements gave Creek strength enough to beat off

the Germans, clear the east bank, and finally cross the river and dig in. This position, however, did not amount to a bridgehead and Creek’s tenuous hold on the west end of the causeway would have meant little but for the action of the 508th Parachute Infantry west of the river.

Elements of the 508th, amounting to about two companies of men under command of Lt. Col. Thomas J. B. Shanley, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, were the most important of at least four groups of paratroopers who assembled west of the Merderet but who for the most part, being forced to fight for survival, could contribute little toward carrying out planned missions. Dropped near Picauville, Colonel Shanley gathered a small force of paratroopers—too small to proceed with his mission of destroying the Douve bridge at Pont l’Abbé. He tried during the day to join other groups in the vicinity with whom he had radio contact, but under constant enemy pressure he was unable to effect a junction until late in the day. It had then become apparent to him that he was engaged with an enemy force of at least battalion strength, and he decided to withdraw to the battalion assembly area on Hill 30. In fact, the Germans, elements of the 1057th Regiment, had been pushing eastward in this area most of the day under orders to counterattack in order to wipe out American parachutists west of the Merderet. Colonel Shanley’s resistance undoubtedly helped save the forces at la Fière and Chef-du-Pont. Once he was firmly established on Hill 30, he formed a valuable outpost against continuing German attacks and a few days later would be in position to contribute substantially to establishing the Merderet bridgehead. For Colonel Shanley’s success three enlisted men have received a large share of the credit. They were Cpl. Ernest T. Roberts, Pvt. Otto K. Zwingman, and Pvt. John A. Lockwood who, while on outpost duty in buildings at Haut Gueutteville, observed the forming of a German counterattack by an estimated battalion of infantry with tank support. They stayed at their posts holding off the enemy attack for two hours and allowing the main body of Shanley’s force to establish an all-around defense at Hill 30.45

As reports of the airborne landings came in to the German Seventh Army headquarters and the extent of the landings became apparent, General Dollmann ordered a series of moves designed to seal off the airhead and destroy it. (Map 2) The 709th Division with the 1058th Regiment (91st Division) attached was ordered to clear the area east of the Merderet.46 At the same time the 91st Division counterattacked from the west using the 1057th Regiment and the 100th Panzer Replacement Battalion in an attempt to wipe out paratroopers who had landed west of the inundated area. The 6th Parachute Regiment under control of the 91st Division was to attack through Carentan from the south.47 Finally at the end of the

Merderet River Crossing at Chef-du-Pont. Village of les Merieux is in lower right-hand corner of picture.

[Image on this page merged with previous page]

German Counterattack in the Cotentin. Reproduction of a captured OB WEST map dated 6-7 June 1944.

day the Seventh Army Sturm Battalion was ordered to move against the American bridgehead from the vicinity of Cherbourg, attacking in the direction of Ste. Mère-Eglise. A regiment of the 243rd Division was ordered to move by night to Montebourg.48 By means of these moves and concentric counterattacks Dollmann was sure at first that he could cope with the Cotentin landings without moving in any additional forces. It was only in the evening that his optimism waned, as the 91st Division reported that its counterattack was making very slow progress because of the difficulties of maneuvering in the hedgerow country. In fact the attack had scarcely materialized at all except in local actions along the Merderet.

Similarly the 1058th Regiment, apparently harassed by scattered American paratroopers, could not get moving in its attack toward Ste. Mère-Eglise. By evening its advance elements were still north of Neuville-au-Plain. Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, commander of the 709th Division, ordered it to resume the attack on Ste. Mère-Eglise the next morning. He attached to it two motorized heavy artillery battalions, the 456th and 457th (each with two 150-mm. guns and a battery of Russian 122-mm. guns), and the company of self-propelled guns of the 709th Antitank Battalion.49

For the general sluggishness of German reaction in the Cotentin, there seem to be several explanations. In the first place two of the three division commanders, von Schlieben and Generalleutnant Wilhelm Falley (of the 91st Division), together with some of the subordinate commanders, were at Rennes attending a war game when the invasion struck. Schlieben did not get back to his headquarters near Valognes until noon. Falley on his return was killed by paratroopers. To the uncertainty caused by the commanders’ absence was added the confusion of disrupted communications. Von Schlieben, for instance, during the day had no contact with two of his battalions in the thick of the fighting, the 1st Battalion, 919th Regiment, in the UTAH Beach area, and the 795th Georgian Battalion near Turqueville. In attempting counterattacks against scattered U.S. riflemen the Germans experienced the same difficulties with the hedgerow country that the Americans did. Finally the LXXXIV Corps headquarters, far away in St. Lô, could not exercise effective control and coordinate the action of the three divisions in the peninsula. On the other hand communications were not set up to enable the division commanders to effect their own coordination.50

The experience of the 6th Parachute Regiment illustrates in striking fashion the confusion and lack of coordination in the initial German reactions and throws a strange half-light on the D-Day battles in the Cotentin. The commander of the regiment, Major Friedrich-August Freiherr von der Heydte, was at his command post north of Periers when the Allied landings began. But telephone lines to the 91st Division and to LXXXIV Corps were broken during the night by open action of the French Resistance. It was not until about 0600 that von der

Heydte was able to reach General Marcks at LXXXIV Corps headquarters by a private line and get his orders, which were to attack with his regiment through Carentan and clean out the rear area of the 709th Division between Carentan and Ste. Mère-Eglise. Von der Heydte arrived in Carentan in the morning and found no Allied troops and very few Germans. He got in touch with his battalions and ordered them to assemble southwest of Carentan. He then climbed the church steeple in St. Côme and looked around. The picture before him was, he said, overwhelming. He could see the Channel and the armada of Allied ships, covering the water to the horizon. He could see hundreds of small landing craft plying to the shore unloading men and tanks and equipment. Yet, for all that, he got no impression of a great battle in progress. It was then about noon. The sun was shining. Except for a few rifle shots now and then it was singularly quiet. He could see no Allied troops. The whole scene reminded him of a summer’s day on the Wannsee.51

It was apparently his impression that no seaborne U.S. troops had come inland in the direction of St. Côme. In accordance with that impression he made his dispositions. He ordered his battalions to come up to St. Côme; the 2nd Battalion was then instructed to proceed to Ste. Mère-Eglise and attack and destroy any enemy encountered. The 1st Battalion was to move to the high ground near Ste. Marie-du-Mont and protect the regiment from any enemy thrusts inland from the sea. The 3rd Battalion was to return to Carentan to provide the regiment with a defense in depth, and the attached 3rd Battalion, 1058th Regiment, was to remain with von der Heydte in St. Côme-du-Mont. The 1st and 2nd Battalions moved out at about 1900. By midnight the 1st Battalion had marched apparently without serious trouble through the territory occupied by the 101st Airborne Division and reached the vicinity of Ste. Marie-du-Mont. The 2nd Battalion moved north and possibly reached the vicinity of Fauville. Both battalions sent a number of American prisoners back to the regimental headquarters.

During the night the landing of U.S. glider reinforcements impressed von der Heydte as new large-scale airborne landings. They cut off the 2nd Battalion from the regiment and from the 1st Battalion. (In reality, both battalions were already cut off by the advance of the 8th Infantry inland, but this development was apparently unknown to von der Heydte.) He ordered the battalions to maintain contact with each other and pull back to form a crescent defense of St. Côme. Only the 2nd Battalion acknowledged receipt of the order and reported that it was not in touch with the 1st Battalion. As for the 1st Battalion, it set out on the morning of 7 June to rejoin the regiment, moving south toward Carentan. It never got there, for at the Douve River it ran into the 101st Airborne Division units and surrendered almost to a man.52

The experience of the 6th Parachute Regiment was typical of the inability of the German forces to concentrate against the landings, even when, as in the case of

Crossing the Channel. Columns of LCI(L)s (above) heading for the French coast

Crossing the Channel. Troops on deck of LCI(L) on D-Day morning

the 82nd Airborne Division, they were scattered and relatively weak. Thanks to this failure, the 82nd was able to maintain itself while it gradually built back its strength. At the end of D Day, the division was strongly ensconced in the vicinity of Ste. Mère-Eglise but was precariously situated outside the main VII Corps beachhead. It had no contact with the 101st Airborne or 4th Infantry Divisions. It had assembled only a fraction of its own men. Planned seaborne reinforcements had not arrived. The bulk of the glider reinforcements (the 325th Glider Infantry) were not due until the next morning. At the end of the day, the division reported that it controlled only 40 percent of its combat infantry and 10 percent of its artillery.53 The first estimate sent on to VII Corps indicated total casualties of about four thousand.54 The bulk of these, however, were the missing paratroopers scattered far and wide in enemy territory. Revised calculations in August 1944 showed D-Day losses of 1,259 including 156 known killed and 756 missing, presumed captured or killed.55

Hitting the Beaches

While U.S. airborne troops dropped on the Cotentin and British paratroopers landed near Caen, the invasion fleet was bringing the main body of the Allied armies to the shores of Normandy. The assault convoys, after turning back for the day’s postponement, reassembled during the morning of 5 June and sailed again for the transport areas 22,000 to 23,000 yards off the French coast in the Bay of the Seine. Behind mine sweepers which cleared and marked ten lanes through old enemy mine fields in the Channel, the huge convoys, under constant air umbrella of fighter squadrons flying at 3,000 to 5,000 feet, made an uneventful voyage unmolested by the enemy either by air or sea.56 H Hour for U.S. beaches was 0630.

The weather was still cause for concern. During the passage a gusty wind blowing from the west at fifteen to twenty knots produced a moderately choppy sea with waves in mid-Channel of from five to six feet in height. This was a heavy sea for the small craft, which had some difficulty in making way. Even in the assault area it was rough for shallow-draft vessels, though there the wind did not exceed fifteen knots and the waves averaged about three feet. Visibility was eight miles with ceiling at 10,000 to 12,000 feet. Scattered clouds from 3,000 to 7,000 feet covered about half the sky over the Channel at H Hour becoming denser farther inland. Conditions in short were difficult though tolerable for both naval and air forces.57

Most serious were the limitations on air operations. Heavy bombers assigned to hit the coastal fortifications at OMAHA Beach had to bomb by instruments through the overcast. With concurrence of General Eisenhower the Eighth Air Force ordered a deliberate delay of several seconds in its release of bombs in order to insure that they were not dropped among the assault craft. The result was that the 13,000

bombs dropped by 329 B-24 bombers did not hit the enemy beach and coast defenses at all but were scattered as far as three miles inland. Medium bombers visually bombing UTAH Beach defenses from a lower altitude had slightly better results, although about a third of all bombs fell seaward of the high-water mark and many of the selected targets were not located by pilots. Of 360 bombers dispatched by IX Bomber Command, 293 attacked UTAH Beach defenses and 67 failed to release their bombs because of the overcast. On the whole the bombing achieved little in neutralizing the coastal fortifications.

At about 0230 the Bayfield, headquarters ship for Task Force U (Rear Adm. Don P. Moon) and VII Corps (Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins), dropped anchor in the transport area off UTAH Beach. Twenty minutes later the Ancon, flagship of Admiral Hall and headquarters ship for Task Force O and V Corps, reached the OMAHA Beach transport area. Unloading of assault troops into the LCVP’s that would take them to the beaches began.

Up to this point there had been virtually no enemy reaction. The German radar stations still in operation had failed to pick up either the air or the sea approach. Because of bad weather Admiral Krancke had no patrol boats in the Channel during the night, nor did he order them out after he heard of the airborne landings. Tidal conditions would not permit them to leave the harbors before daylight and, besides, Krancke was still not sure that a major attack was in progress. Shortly after three o’clock, however, Naval Commander Normandy reported sighting ten large craft lying some seven miles off the coast north of Port-en-Bessin. This news, in conjunction with an increasingly sharp definition of the extent of the airborne landings, at last convinced Admiral Krancke that he was confronting a large-scale landing. He gave such orders as he could. The Western Defense Forces were to patrol the coastal waters; the Landwirt submarines were to be alerted; the 8th Destroyer Flotilla was to move up from Royan to Brest; the 5th Torpedo Boat Flotilla was to reconnoiter the Orne estuary area; and the 9th Torpedo Boat Flotilla was to patrol off Cap de la Hague. The torpedo boats of the 5th Flotilla left Le Havre at 0430, but an hour out of port they met six Allied warships escorted by 15 to 20 destroyers. After firing torpedoes at the Allied vessels, the small German boats were attacked from the air. They succeeded in driving off the attackers with antiaircraft fire, but then had to return to Le Havre to replenish their load of torpedoes and ammunition. Two torpedo boat flotillas reconnoitering out of Cherbourg were forced by heavy seas to return to port at dawn. This virtually concluded German naval activity for the day. Admiral Krancke wrote in his diary: “It was only to be expected that no effective blow could be struck at such a superior enemy force.”58 He made plans, however, to attack the Allied fleet that night.

German coastal batteries began sporadic firing at 0535, or only fifteen minutes before Allied naval bombardment opened prearranged counterbattery fire. Projectiles from Allied battleships and cruisers and destroyers continued to thunder over the heads of the troops making the final run-in to shore until a few minutes before the touchdown. Beach drenching

was then taken up by the close-support craft. Although the time schedule went generally according to plan on both American beaches, the volume of fire laid down on vital targets was considerably less at OMAHA than expected. Most enemy coastal defenses were sited to cover the beaches rather than the sea approaches. They were therefore well concealed from observation from the sea and were correspondingly difficult to hit. The beach drenching seems generally to have missed its targets; a large percentage of the rockets overshot their marks.59

Naval gunfire coupled with the air bombardment, however, had one important effect at OMAHA Beach which was not at first apparent to the assaulting troops. The Germans credit the Allied bombardment with having detonated large mine field areas on which they counted heavily to bar the attackers from penetrating inland between the infantry strong points. Preparatory fire seems also to have knocked out many of the defending rocket pits. But it was supporting naval gunfire after H Hour which made the substantial contribution to the battle, in neutralizing key strong points, breaking up counterattacks, wearing down the defenders, and dominating the assault area.

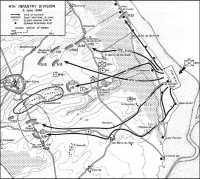

In the VII Corps zone the 4th Division (Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton)60 planned to land in column of regiments on a two-battalion front of about 2,200 yards. The 8th Infantry (Col. James A. Van Fleet), with the 3rd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry attached, would make the initial assault. It would first occupy the high ground along the road between Ste. Marie-du-Mont and les Forges and would be prepared to move with the bulk of its force thereafter westward across the Merderet River in the zone of the 82nd Airborne Division. One battalion would be left in the area west of St. Martin to protect the division’s north flank until the arrival of the 22nd Infantry. The 22nd Infantry (Col. Hervey A. Tribolet), next infantry unit to land, beginning at H plus 85 minutes, would turn north from the beaches to seize the causeway across the inundations at les Dunes de Varreville. Continuing the push northwest, the regiment would capture Quinéville and occupy the high ground at Quinéville and Fontenay-sur-Mer. In the center of the beachhead the 12th Infantry (Col. Russell P. Reeder), landing after H plus 4 hours, would advance with two battalions abreast to seize the high ground between Emondeville and the Merderet River. One battalion of the regiment was at first designated as division reserve to pass to division control in the vicinity of Turqueville. By the late May change of plan, following the alteration of the airborne missions, the battalion was instead released to regimental control and the 12th Infantry was assigned the additional mission of seizing a crossing over the Merderet at le Port Brehay just southwest of the regiment’s main objective area. One regiment (the 359th Infantry) of the 90th Division, the first follow-up division, was attached to the 4th Division to begin landing on D Day.61 It would assemble in reserve

Troops on Utah Beach. The troops wading ashore were photographed shortly after H Hour. Note DD tanks on beach

Troops on Utah Beach. Soldiers take shelter behind sea wall while awaiting orders to move inland

near Foucarville. In May, enemy activity was observed on the St. Marcouf Islands flanking UTAH Beach on the north. It was therefore decided to land detachments of the 4th and 24th Cavalry Squadrons two hours before H Hour to clean out what was suspected to be an enemy observation post or mine field control point.