Chapter 9: The V Corps Lodgment (7–18 June)

Securing the Beachheads

Supreme in the air, the Allies began on D Day to build up a similarly crushing superiority on the ground. By the end of 6 June 1944 First Army had succeeded in landing most of eight and a third infantry regiments—only a little less than planned. For operations on 7 June five divisions were ashore and operational (although one, the 29th, lacked one of its regiments until later in the day). All of these divisions were seriously deficient in transport, tank support, artillery, and above all supplies. The worst situation was in the V Corps zone where, of 2,400 tons of supplies planned to be unloaded during D Day, only about 100 tons actually came in. Ammunition shortage was grave. Both beaches on D plus 1 were still under enemy artillery fire. On OMAHA pockets of enemy riflemen still held out at various points along the coast; beach obstacles, even after work by the engineers during low tide of the afternoon of D Day, were still only about a third cleared; beach exits had not been opened as scheduled nor vehicle parks established inland on the scale contemplated.

Nowhere in First Army zone had initial objectives been fully achieved. In the V Corps zone not only had the two assault regiments stopped far short of their objectives along the beachhead maintenance line, but they were so badly chewed up and disorganized by the hard fighting that they were scarcely capable of continuing the attack as planned. Units of VII Corps had been more successful in staking out a beachhead large enough to remove the beaches from direct enemy fire and to provide sufficient space for maneuver and build-up. The 4th Division had taken only light casualties and was in relatively good condition for subsequent attacks. Nevertheless the area was considerably smaller than desired and the initial efforts to push it out westward across the Merderet and southward toward a junction with V Corps were barred by the hard-fighting 91st Division.

The operations in the two days following the landings were a continuation of the assault phase as all units sought to reach their D-Day objectives.1 The exhaustion of the 16th and 116th Infantry Regiments in the V Corps zone required some reshuffling of regimental and battalion missions, and, in the VII Corps zone, missions of the 4th Division had to be tempered to conform to the realities of enemy opposition.

In effect, the V Corps attack continued on 7 June with two divisions abreast although the regiments of the 29th Division

did not formally come under command of Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt, the division commander, until 1700. Gerhardt had landed on the evening of D Day and with General Cota planned and directed the operations of the 115th and 116th Infantry Regiments during D plus 1. (Map XV) The third regiment of the division, the 175th Infantry, began landing at 1230 on 7 June, two hours later than scheduled, and was ashore by 1630. The 29th Division operated generally west of a line through St. Laurent and Formigny; the 1st Division, with all three of its regiments in line, operated generally to the east.

The principal 1st Division attack on 7 June was the 18th Infantry’s drive southward toward its D-Day objectives: the high ground north of Trévières and the Mandeville–Mosles area south of the Aure River. For this attack the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry, was attached. The other tasks confronting the 1st Division were to make contact with the British and to clean out the Colleville area. To accomplish the first, two battalions (the 1st of the 26th Infantry and the 3rd of the 16th Infantry) under control of the 16th attacked southeastward with the mission of taking the high ground west and southwest of Port-en-Bessin, including Mt. Cauvin. The clean-up job was assigned to the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 16th Infantry. The 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry, was held in division reserve.

Despite wide dispersion of the attacking battalions and scanty artillery and tank support, all units made good progress against slight and sporadic resistance. A marked degree of enemy disorganization had been observed beginning on the afternoon of D Day. Expected counter-attacks had not materialized and the enemy’s morale seemed low. The 1st Division realized that it was through the coastal crust and at the moment had to deal only with remnants of the 352nd Division. It was thought, however, that an armored counterattack might be in the making.2

On the right, Huppain and the forward slopes of the ridge line 1,000 yards north of Mt. Cauvin were occupied. But the enemy, strongly opposing simultaneous British attacks from the east, continued to hold a narrow wedge between American and British beachheads through Port-en-Bessin and south along the valley of the Drôm River. In the center the 18th Infantry made two crossings of the Aure, the 2nd Battalion occupying Mosles and the 3rd, Mandeville. The 1st Battalion, effectively supported by five tanks of the 741st Tank Battalion, captured the high ground at Engranville after a fight with something less than a company of German infantry which lasted most of the afternoon.

The success of the 18th Infantry attack was somewhat qualified by the inability of the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry, on the division’s right to take Formigny. Although opposition by exhausted elements of the 916th Regiment was not heavy. the battalion was unable to get moving.3

It was not until the next morning that the enemy was driven out of Formigny by a company of 18th Infantry and some tanks attacking from the Engranville position.

On the German side the 352nd Division at the end of D Day had been chiefly concerned with its open flank where the British were driving into the hole opened by the collapse of the left wing of the 716th Division. Throughout 7 June there was little General Kraiss could do to repair the damage, for his last organic reserves had had to be committed in the center where the 916th Regiment was strained to the breaking point. At noon he requested and secured the attachment of the 30th Mobile Brigade. The brigade, which came up from Coutances on bicycles, arrived only late in the afternoon, its young, inexperienced recruits tired in body and spirit from constant attacks by low-flying planes along the route. One battalion (the 513th) was committed in the vicinity of Formigny to strengthen the 916th Regiment.

The brigade, less this battalion, assembled northwest of Bayeux and was attached to the 726th Regiment with orders to attack the flank of British forces advancing on Bayeux. (See Map XIII) Action of German units in the Bayeux area during 7 June was so confused that no coherent story can be told in detail. The whole flank of the 352nd Division from the Drôm River to the division boundary east of St. Léger was falling apart. The disintegration, furthermore, was so rapid that reports reaching division headquarters were late and scattered. As evidence of the confusion, it is worth contrasting the German command picture of the action with what actually happened.4

In the early afternoon following the commitment of the 30th Mobile Brigade, General Kraiss’s headquarters believed that the 352nd Division held a thin defensive arc north and northeast of Bayeux from about Vaux-sur-Aure to Sommervieu. From left to right the units engaged were the 30th Mobile Brigade (-), elements of the 2nd Battalion, 916th Regiment, and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 1352nd Artillery Regiment. Having expended their last rounds, these units had destroyed their guns and fought as infantry. South of this line there were only scratch forces, the most important of which were remnants of Kampfgruppe Meyer (2nd Battalion, 915th Regiment and the Füsilier Battalion, 352nd Division), thought to be defending weakly northeast and north of Tilly-sur-Seulles. The Bayeux defense was believed to have held during the day, despite penetrations by British armor and a British thrust through Sommervieu which was reported to have split the 2nd Battalion, 916th, from the artillery unit. At midnight, the 352nd Division and Seventh Army supposed that the main British advance had been checked short of Bayeux and that countermeasures were in process to avert the fall of the city. While the 352nd Division commander, General Kraiss, seriously doubted that those measures would succeed in view of the depletion of his own forces and their exhaustion after constant pounding by Allied aircraft and

naval artillery, he still did not know the true extent of the collapse on his right.5

The collapse was, in fact, almost complete. In the morning of 7 June, before the arrival of the 30th Mobile Brigade on the Drôm River, two battalions of the British 56th Infantry Brigade (50th Division) entered Bayeux and by noon had cleared the city. The British then pushed out along the southwest road to occupy the high ground at Monunirel. The third battalion of the brigade in the meantime advanced about two miles southwest from Vaux-sur-Aure. On the coast, the 47th Royal Marine Commando captured Port-en-Bessin in a stiff fight beginning about 1600, 7 June, and not ending until the early morning hours of 8 June. East of Bayeux, if there were still German forces at nightfall on 7 June, they were no more than remnants with insufficient coherence even to form a resistance pocket within British lines. Two brigades of the 50th Division were south of the Bayeux-Caen highway. On their left and astride that highway was one brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division.

The converging moves of the British 50th Division and the U.S. 1st Division on 7 June had squeezed the German 30th Mobile Brigade and elements of the 726th Regiment into a narrow corridor along the Drôm River north to its junction with the Aure. (See Map XV) On 8 June the Allied vise was tightened in an effort to destroy the enemy forces separating the British and American beachheads On the American side, the mission of attacking to effect a junction with the British was assigned to the 26th Infantry. The attack, however, never gathered momentum, partly because of the difficulty of assembling the widely dispersed battalions, and partly because of heavy enemy resistance.

The 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry, released from division reserve at 1745, 7 June, had moved during the night from the vicinity of Etreham to the crossroads between Mosles and Tour-en-Bessin which they occupied about dawn. There they awaited the rest of the regiment throughout 8 June. The 1st Battalion, meanwhile, bogged down on 8 June at the Aure River crossing at Etreham, where the enemy fought stubbornly to hold one side of the Drôm corridor. The 3rd Battalion remained at Formigny during the morning until it could be relieved by a battalion of the 115th Infantry. In the early afternoon it began a march down the Bayeux highway. At 1800 it attacked through the 2nd Battalion positions, and through Tour-en-Bessin to Ste. Anne which it reached shortly after midnight. During the night a violent and confused action took place at Ste. Anne as the Germans, now in process of withdrawing from the corridor, fought to keep the escape route open.

The 1st Division thus failed to trap the enemy. The British were similarly checked east of the Drôm. Elements of the 50th Division attacked and cleared Sully during 8 June but were unable to hold a bridgehead over the Drôm. Other elements of the division pressed in the northern end of the enemy corridor by clearing the château at Fosse Soucy. But, in the face of threatened enemy counterattacks, the British withdrew to high ground near Escures.

Thanks to these actions, the German 726th Regiment during the night of 8-9 June was able to extricate the bulk of its forces. This was perhaps the first German withdrawal from coastal positions accomplished on orders from division and corps. In direct disobedience of Hitler’s command to hold every inch of ground to the last bullet, the decision reflected the seriousness of the German position. During the morning of 8 June the 352nd Division was out of touch with the 726th Regiment. At about 1500, however, contact was established with the regimental commander (possibly just west of Sully). He was ordered to resist stubbornly with all available forces until nightfall and then break out to the southwest and form a defensive line from Blay east to Haley and thence south to Agy. Shortly after General Kraiss had given this order, the corps commander, General Marcks, came into the 352nd Division command post. Marcks was asked to approve the decision on the grounds that, if the troops in the Bayeux salient were sacrificed, the division would have nothing with which to repair the rip in its right flank and the way would be open for unopposed Allied marches to the south. “After a long pause, the Commanding General [Marcks] agreed. ...”6

While the U.S. 1st Division and the British converged on Bayeux the 29th Division on D plus 1 still found itself entangled in the enemy’s coastal defenses and spent most of the day cleaning up the fragments of enemy units that were shattered but not destroyed by the initial shock of the landings. In some areas small arms fire from groups of enemy riflemen or isolated strong points was almost continuous; American troops gradually became used to moving under the constant crack of bullets.

D Day had left the units of the 115th and 116th Infantry Regiments and a large part of the two Ranger battalions in the sliver of coast between Vierville and St. Laurent, where they were still meeting scattered opposition. The 175th Infantry was still afloat. A precondition for the division’s pursuit of D-Day objectives was to expand this toehold and clear room for maneuver. The 115th Infantry, after mopping up around St. Laurent, attacked generally southwest toward Louvières and Montigny, while the 116th Infantry with Ranger units undertook to clear the bluffs and go to the relief of the three Ranger companies isolated on Pointe du Hoc.

The 115th Infantry made slow progress. Moving on a broad front, the regiment found communication difficult. Furthermore, since the regiment still had no transport, ammunition and heavy weapons had to be hand-carried. Near the end of the day Col. Eugene N. Slappey requested the immediate establishment of army supply points as an urgent prerequisite for further advance.7

Colonel Canham’s 116th Infantry, on the other hand, advanced rapidly. The regiment moved in column down the coastal road with ten tanks rolling between files of infantry. Tank fire was employed to neutralize small enemy positions and the main body of the regiment pushed on past them. Before noon Canham was only 1,000 yards from Pointe du Hoc. The Rangers awaiting relief

there then numbered less than 100 effectives. Their position had seriously deteriorated during the night of 6-7 June as a result of a counterattack by the 914th Regiment which overran their outpost line and pinned the force to a strip of the headland only about 200 yards deep. While destroyer fire and the Rangers’ two mortars kept the enemy at bay, the situation remained desperate until the afternoon when two LCVPs landed water, food, and ammunition and about thirty reinforcements. At the same time a series of attacks by the relieving force from the vicinity of St. Pierre-du-Mont, although frustrated by well-placed enemy artillery fire, at least eased the pressure.

By 1630 on 7 June the 175th Infantry (Col. Paul R. Goode) had come ashore and was placed in the line in the vicinity of Gruchy. Additional landings of artillery units swelled the 29th Division’s artillery support to a total of twenty-nine guns belonging to five battalions. Although the achievements of the division on D plus 1 seemed slight measured in yards or vital objectives taken, in reality the crust of enemy defenses was broken and the division was set for a full-scale attack on the morrow.

The fighting in the VII Corps zone on D plus 1, like that in V Corps, aimed first at clearing the beachhead already staked out and second at pushing on toward D-Day objectives. (Map XVI)

The only substantial advances of 7 June were made on the north flank where the two regiments of the 4th Division pushed the enemy back two miles to his strongly fortified positions at Azeville and Crisbecq. The 12th Infantry, attacking on the left from the vicinity of Beuzeville-au-Plain, reached the forward slope of hills between Azeville and le Bisson where, faced with stiffened resistance, it halted for the night to reorganize. The 22nd Infantry on the right advanced directly on Crisbecq. It moved rapidly to a point between Azeville and de Dodainville where it began getting fire from the forts.

Both the Crisbecq and Azeville fortifications were permanent coastal artillery positions thoroughly organized for defense from land attack. Crisbecq was a naval battery with 210-mm. guns.8 Azeville contained the four French 105-mm. guns of the 2nd Battery of the 1261st Artillery Regiment (army coastal artillery). At both positions massive concrete blockhouses with underground ammunition storage and interconnecting trenches constituted the core of the fortifications and were ringed with barbed wire and defended by automatic weapons. At Azeville the main positions were outposted with concrete sentry boxes.

Attacks were launched on both forts in battalion strength and were driven back. The task at Crisbecq was especially difficult because approach to the fort was canalized along a narrow hedged trail. Open fields lay on the west, and on the east were either swamplands or steep slopes. The battalion advancing along this trail was counterattacked on the left flank and fell back in considerable confusion to re-establish a line 300 yards south of Bas Village de Dodainville. The Germans, trying to press their advantage with renewed attacks after dark, were routed by naval fire.

In the meantime, along the beach, the

3rd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry had been advancing northward with the mission of reducing the beach fortifications. Progress was slow and costly as troops came under small arms fire from the beach resistance points as well as artillery fire from inland batteries. About 2,000 yards were made during the day and two enemy resistance nests cleared. In the evening the battalion was brought inland as regimental reserve to guard against further counterattacks from the Azeville-Crisbecq positions. During the night the bulk of the battalion returned to the beach to receive the surrender of the enemy at Taret de Ravenoville who had been discouraged from continued resistance chiefly by naval shelling.

In the center of the VII Corps beachhead the day was occupied chiefly with eliminating the enemy forces south of Ste. Mére-Eglise who on D Day had prevented firm junction between the 8th Infantry on the south and the 82nd Airborne Division. A patrol of the 82nd Airborne Division got through to General Barton during the night and plans were then coordinated for the next day’s operations. In the morning the 8th Infantry, on General Barton’s order, attacked the Turqueville salient. Turqueville itself, held by the 795th Georgian Battalion, was hit by the 1st Battalion from the east. After a hard fight the Russian unit was talked into surrender by a Russian-speaking American captive. At the same time the 2nd and 3rd Battalions struck north from their positions near les Forges. The 1st and 2nd Battalions were supported by two companies of the 70th Tank Battalion.9 The 3rd Battalion on the left, advancing astride the main highway, was stopped hard at the Fauville–Ecoqueneauville ridge by machine gun and artillery fire. These troops were shaken loose, however, by the 2nd Battalion’s capture of Ecoqueneauville, and both units continued the advance. When they reached Ste. Mére-Eglise they found a German counterattack in progress, although they apparently did not recognize it as such.

This counterattack, which lasted most of the day, actually represented General von Schlieben’s supreme effort to drive in the Cotentin beachhead from the north. It will be recalled that the 1058th Regiment (less one battalion) had been ordered to attack St. Mére-Eglise on D Day. Lacking artillery, it had spent all day working through the hedgerows against spasmodic paratroop opposition and only reached Neuville by nightfall. At dawn on D plus 1 the attack was resumed. For it the 1058th now received attachments of the 456th and 457th Artillery Battalions, the 3rd Battalion of the 243rd Artillery Regiment (less one battery), the Seventh Army Sturm Battalion, and one company of the 709th Antitank Battalion with ten self-propelled 75-mm. guns.10

After preparatory fire the Sturm Battalion began the attack astride the main highway, initially to make contact with elements of the 1058th Regiment which had been cut off in action during D Day. When contact was made, the attack was reorganized and the Sturm Battalion struck down the west side of the highway, with the 1058th on the east. It is apparent that the 1058th Regiment, demoralized

Troops on Utah Beach under Artillery Fire

in the fighting of the day before, made little progress. The Sturm Battalion, however, supported by the 709th Division assault guns, which the Americans mistook for tanks, carried the attack to the outskirts of Ste. Mére-Eglise.

To the American command the situation looked gravely threatening. Ste. Mére-Eglise, besides being important as a communications hub, was the core of the 82nd Airborne Division’s position, which elsewhere was still tenuous. General Ridgway, thinking that a German armored thrust was building up, called for assistance. A staff officer met Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, VII Corps commander, at the 4th Division command post near Audouville-la-Hubert.11 Collins ordered a task force of the 746th Tank Battalion, which had been in 4th Division reserve near Reuville, to proceed at once to Ste. Mére-Eglise. The task force, commanded by Lt. Col. C. G. Hupfer and consisting of Company B, the assault gun platoon, and three headquarters tanks, drove into Ste. Mére-Eglise in the early afternoon and turned north along the Montebourg highway. A few hundred yards out of town the leading tanks came under heavy enemy artillery fire and about the same time spotted the German assault guns in column along the road. A fire fight began which, because of the column formation on each side, was inconclusive. Colonel Hupfer in the meantime reconnoitered a trail east of the main highway leading north into Neuville. Some of the 746th Battalion tanks took this route, entered Neuville, destroyed two enemy assault guns, occupied the town, and took about sixty prisoners as well as releasing nineteen captured U.S. paratroopers.12

More significantly this armored slice northward cut the German forces attacking Ste. Mére-Eglise and began a panic on the German side. For the first time in the early beachhead battles the Americans were confronting the Germans with something like massed armor in a relatively small sector. When the 8th Infantry (-) arrived north of Ste. Mére-Eglise with two companies of the 70th Tank Battalion in support, about sixty American tanks were deployed in the area. While some of the tanks of the 746th Tank Battalion were moving on Neuville, Colonel MacNeely’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, joined Colonel Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, in an infantry-tank attack to clear the enemy in the vicinity of Sigeville. Vandervoort, with the commander of the 70th Tank Battalion, Lt. Col. John C. Welborn, directing tank operations from a jeep, advanced up the highway north of Ste. Mére-Eglise, while MacNeely swept in from the west.13 In the envelopment 300 of the enemy were captured or killed.

The 1058th Regiment, thus splintered by two separate American attacks and demoralized by the presence of so many American tanks, broke and pulled out in disorder. The Sturm Battalion west of the highway and out of contact with the main force also withdrew. The retreat was checked only late in the day by intervention of General Schlieben. The division

commander rallied his panicky troops and began putting them into a defensive line about 1,300 yards north of Neuville. Convinced after the failure of the Ste. Mere attack that he no longer had the strength needed for a successful counterattack to reduce the American bridgehead, Schlieben determined that his policy must be simply to contain it and prevent a breakthrough to Cherbourg. He concentrated therefore on building a strong defensive line. He brought into the line a battalion of the 919th Regiment as well as the 922nd Regiment (243rd Division), which had arrived during the morning of 7 June. All these elements were formed into Kampfgruppe under command of Oberst Helmuth Rohrbach, commander of the 729th Regiment. Further to concentrate his strength, Schlieben ordered the withdrawal of the bulk of the troops from defenses along the east coast which were not under attack. In succeeding days this defense was to be still further reinforced until it constituted a strong barrier to the attempts of the 4th Division to push north.14

After the 8th Infantry had pushed north from les Forges, the 325th Glider Infantry began landing in the area in two serials as scheduled. Although somewhat scattered and hit by ground fire, the majority of the gliders came in where planned and rapid assembly was effected. The regiment originally intended as 82nd Airborne Division reserve was actually split: one battalion was committed in the la Fière area to strengthen attacks to force a crossing there; and one battalion was attached to the 505th Parachute Infantry for operations to the north of Ste. Mére-Eglise.

While the 82nd Airborne Division had thus consolidated its base, its principal D-Day assignment-the establishing of bridgeheads across the Merderet-came no nearer accomplishment. On the contrary, during the morning of 7 June it was touch and go whether a determined enemy counterattack might not break the division’s hold on the east bank of the river. At about 0800 the attack of elements of the enemy 1057th Regiment began to form against the American la Fére position. Mortar and machine gun fire ranged in, chiefly on Company A, 505th Parachute Infantry, which was dug in to the right of the bridge. An hour or so later four Renault tanks led a German infantry advance across the bridge. The lead tank was disabled by either bazooka fire or a shell from a 57-mm. antitank gun that was supporting Company A. Although this checked the advance, the German infantry took advantage of the cover furnished by the knocked-out tank and some burned-out vehicles, which the American defenders had pulled onto the causeway during the night, to open a critical fire fight at close range. At the same time German mortar shells fell in increasing numbers among Company A’s foxholes. The American platoon immediately to the right of the bridge was especially hard hit and eventually reduced to but fifteen men. These men, however, encouraged by the heroic leadership of Sgt. William D. Owens and by the presence in the thick of the fighting of division officers, including General Ridgway, held their line. The fight was halted at last by a German request for a half-hour’s truce to remove the wounded. When the half hour expired, the enemy did not return to the attack. A count of Company A revealed that

Planes and gliders circling Les Forges on the morning of 7 June.

Dust is raised by gliders landing in fields at upper left. Wrecked gliders in foreground are some of those that landed on the evening of 6 June.

almost half of its combat effectives had fallen in the defense, either killed or seriously wounded.15

South of the 82nd Division the 101st Division with small forces of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, and the 501st Parachute Infantry still held precarious positions on the north bank of the Douve. Isolated and short of ammunition, these troops were unable to go on the offensive on 7 June. They nevertheless scored a notable success during the day when together they killed or captured the whole 1st Battalion of the 6th Parachute Regiment. This battalion had advanced on regimental order to Ste. Marie-du-Mont on D Day and then had been cut off. Patrols sent out by von der Heydte on 7 June from St. Côme-du-Mont became involved in fighting a few hundred yards east of the town and could not get through. The isolated battalion in the meantime was already moving south. About the middle of the afternoon paratroopers at le Port and la Barquette observed the Germans (about 800 in all) advancing through the open fields and marshes north of the river and east of the Carentan highway. In independent actions the men under Captain Shettle and those under Colonel Johnson opened fire. Caught by surprise and bluffed by demonstrations designed to impress them with overwhelming American strength, the majority of the Germans surrendered. About 250 were taken by Captain Shettle’s men at le Port, about 350 by Colonel Johnson at la Barquette.16 More than half the remainder were killed in the fire fight preceding surrender. Only twenty-five men escaped to Carentan.17

During D Day no news of the actions along the Douve had reached the 101st Division headquarters. Since capture of the Douve bridges was one of the most important of the division’s missions, on which depended the immediate security of VII Corps on the south and ultimate junction with V Corps, General Taylor decided on the afternoon of D Day to send the 506th Parachute Infantry (less the 3rd Battalion) south on a reconnaissance in force. The reconnaissance, which in fact became an attack, led off on the morning of 7 June in column down the road from Culoville. Though harassed by scattered rifle fire, the 506th reached Vierville without undue delay, cleared the town, and then split, with the 1st Battalion heading down the highway to Beaumont and the 2nd diverging cross country to the left toward Angoville-au-Plain. Halted just beyond Vierville by heavy small arms fire, the attacks broke loose only after a platoon of medium tanks had been brought up and attached to the 2nd Battalion. The 1st Battalion fought its way down astride the highway to Beaumont where it was stopped by two enemy counterattacks.18 The 2nd Battalion medium tanks together with a platoon of light tanks were then sent to its support and they advanced another 1,000 yards to just east of St. Côme-du-Mont.

At the same time that the 506th Infantry was attacking south, the 2nd Battalion of the 501st Infantry, which on D Day had fought an isolated and inconclusive action around les Droueries, continued its attempt to push westward into St. Côme-du-Mont, still held in some force by two battalions under von der Heydte’s command. This attack, coordinated in early afternoon with Colonel Sink, commanding the 506th Infantry, and supported by six medium tanks of the 746th Tank Battalion and the guns of the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, made substantial headway. But it was a typical Normandy battle-cleaning out dug-in enemy riflemen and machine gun positions from the hedgerows field by field. The battalion did not get far enough west to tie in with the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry. The latter was therefore ordered to withdraw to Beaumont and all units held during the night, reorganizing for resumption of the attack the next day.

The small American gains of 7 June encouraged the Germans to feel that they had at least frustrated the Allied time schedule.19 On the other hand, their own countermeasures planned for the day had also been checked, and, in general, it was clear that the invasion had succeeded in gaining a foothold. The build-up race was on.

On the Caen front the 21st Panzer Division had called off its counterattack on the evening of D Day short of its objectives. (See Map XIII.) Throughout 7 June the division remained on the defensive except for small unsuccessful attacks east of the Orne against the British airborne forces. The 12th SS Panzer Division began arriving in assembly areas between Caen and Bronay during the day and Panzer Lehr Division formed to its left rear, north and northeast of Tilly-sur-Seulles. In the afternoon the reconnaissance battalion of the 12th SS Panzer Division was committed to reconnoiter the wide gap between the 21st Panzer and the 352nd Divisions.20 But air attacks had so delayed the assembly of I SS Panzer Corps and caused such heavy casualties that the corps postponed until the morning of 8 June the scheduled two-division counterattack to recapture Courseulles. Rundstedt on 7 June had decided to put his own armored staff, Panzer Group West under General Geyr, in charge of the attack. Geyr was attached to Seventh Army and ordered to take over the sector on both sides of the Orne River and west as far as Tilly-sur-Seulles, seal off the penetrations at Caen and in the 352nd Division sector, and counterattack the Allies who had broken through southeast of Bayeux. But Geyr did not arrive to take over until the night of 8-9 June. In the meantime I SS Panzer Corps had decided to make only a limited-objective attack with the 12th SS and 21st Panzer Divisions and a Kampfgruppe of Panzer Lehr Division, pending the arrival of the tanks of the latter division. The attack of 8 June to gain a line of departure for the later planned three-division attack made little progress and before evening both

divisions had gone over to the defensive.21 The 12th SS was holding positions astride the Caen-Bayeux road between Authie and Carpiquet. The 21st Panzer Division, also on the defensive, was split on either side of the Orne. Panzer Lehr remained in assembly areas near Thury-Harcourt, southwest of Caen. As the attack failed to materialize on 8 June and Allied pressure continued to build up, the plan for a bold strike to the coast with two armored divisions abreast was abandoned. Seventh Army, concerned over the loss of Bayeux, decided to maneuver to recapture it. I SS Panzer Corps intended, therefore, to hold north and west of Caen while directing Panzer Lehr and portions of the 12th SS Panzer Division on Bayeux. Thus, as General Geyr commented later, the fist was unclenched just as it was ready to strike.22

While Seventh Army indulged fatal second thoughts concerning its critical right flank, Field Marshal Rommel began to focus attention on the threat to Cherbourg. Reports of large-scale Allied airborne and glider landings in the Coutances–Lessay area caused him on the morning of 7 June to order the immediate move of both the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division and the 77th Division to meet the threat. He believed that the Coutances landings were part of an Allied move to cut off Cherbourg and the whole Cotentin Peninsula and that it was therefore an “unconditional necessity” to counter with all available forces. The risk of weakening Brittany by the transfer of the 77th Division could be accepted, he thought, since it looked as though the Allies were fully committed in Normandy.23

Later in the morning Seventh Army assigned the task of cleaning up the west coast of the Cotentin to the II Parachute Corps then in Brittany. In addition to the 77th Division and the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, already under orders to move, the corps was to command the 3rd Parachute Division. The latter received marching orders to move by motor to assembly areas near those planned for the 17th SS northeast of Avranches. The 77th Division, which received orders to move by foot at 1015, actually began moving out at 1500. By 2000, advance elements of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division had crossed the Loire. But traffic thereafter was interrupted by Allied air attacks on the Loire bridges which lasted for an hour and a half and scored twenty-four hits on a railroad bridge that the division had been using. With requisitioned vehicles the 3rd Parachute Division formed an advanced motorized group consisting of one battalion from each of the regiments, two engineer companies, two artillery batteries, and the antiaircraft and signal battalions. This group moved out, surprisingly, without opposition from the air. But Seventh Army reported that movement of the remainder of the division was dependent on motor transport space from the two corps remaining in Brittany and requested an additional 2,000 tons from OB WEST and other reserves. On the morning of 8 June after General der Fallschirmtruppen Eugen Meindl, commanding II Parachute Corps, had personally

confirmed that the reports of airborne landings in the Coutances area were without foundation, the II Parachute Corps with two divisions was diverted to St. Lô.24

Concern over the defense of Cherbourg again faded before the greater urgency of holding at Caen. This reaction was not due to ignorance of the true situation. On the contrary, on the evening of 6 June a copy of the VII Corps field order had been picked up by the 914th Regiment from a boat that drifted ashore in the mouth of the Vire River. The next evening a copy of the V Corps order was taken from the body of an American officer killed at Vierville-sur-Mer. The Germans thus had in their hands the entire scheme of maneuver and order of battle for American units in the first phase of the invasion.25

The fact that possession of these plans had no effect on the German conduct of operations throws considerable light on the tactical and strategic problems facing the enemy command. From the plans, Seventh Army and OB WEST learned that the major immediate objectives of Bradley’s forces were Cherbourg and St. Lô. But this news, after the first day, was hardly a revelation. The plans were confined to outlines of the initial phase and did not reveal American intentions beyond the establishment of a lodgment including Cherbourg and St. Lô. Even if they had revealed the planned American push into Brittany, however, the Germans could not have profited materially from the knowledge. Rommel was not free to shift the weight of his defense to the American flank to block either the assault on Cherbourg or Bradley’s planned move southward toward Brittany. The major operational threat, from his point of view, remained the possibility of a British breakout at Caen and a sweep to Paris. Without British plans, the Germans could not be sure that such a move had not been calculated. Even if it had not, a German collapse on that sector would undoubtedly be exploited to turn the flank of Seventh Army. In short, complete knowledge of American intentions could not have altered the logic of the battle dictated by terrain, the disposition of forces, and the location of the strategic objectives.26

One fact might have been deduced from the plans: that they envisaged such a large commitment of force as to rule out a second major landing attempt. General Dollmann drew this conclusion. Field Marshal Rundstedt was inclined to agree. But OKW and Hitler figured the evidence was inconclusive. Again the fact that British plans were missing left a large realm for speculation and, according to German intelligence estimates, a large uncommitted military force.

As of 1 June, the Germans had estimated that the Allies had combat forces in the United Kingdom equivalent to eighty-five divisions including eight airborne divisions.27 The Allied high command,

aware that the enemy was overestimating British and American strength, made every effort to sustain the illusion. In addition, the Allies made use of the high regard in which General Patton was held by the Germans to persuade them that an army group under his command still remained in England after 6 June. The existence of this large reserve force was easy for the Germans to believe since it fitted with their preconceptions that a second major landing would strike the Kanalküste. The Allies fostered this belief by various ruses so successfully that not until July did OKW finally appreciate that no second landing would take place. In the meantime the Fifteenth Army remained tied to the Kanalküste.

Tactically, German knowledge of American plans might have made some difference by enabling the Germans to mass reserves and stage counterattacks at points along the planned axes of the American advance. Such a concentration of reserves was actually carried out by Seventh Army in and around St. Lô, but even without knowledge of American intentions the Germans would probably still have chosen to defend St. Lô because of its importance as a road junction and the terrain configurations that made it defensively strong. For the rest, the Germans could never maneuver with enough freedom to exploit any tactical situation. Instead of being able to mass reserves in accordance with plan, General Dollmann picked up the reserve companies and battalions as they straggled in, delayed and decimated by air attacks, and put them in to plug gaps in his lines wherever the immediate danger seemed gravest. The policy of maintaining an intact defense, whether wise or not, meant that German tactical commanders in disposing their reserves were continually confronted with emergencies and never with tactical choices. Absorbed, therefore, in sealing off today’s penetrations, they had no resources with which to face tomorrow’s threat.

Junction between V and II Corps

The failure of both V and VII Corps to make any substantial progress toward the vital joining of the beachheads, together with the general slowness of the advances on D-Day objectives, had become a matter of concern to General Eisenhower, General Montgomery, General Bradley, and both corps commanders. The American build-up was far behind schedule, particularly in the landing of supplies. At the end of D plus 1 not more than a quarter of the planned 14,500 tons were ashore. The troop build-up, planned at about 107,000 for the first two days, was 20,000 short. Scarcely more than half the 14,000 vehicles had been disembarked.28 Delayed build-up was in part due to technical difficulties of unloading and in part to the slow advance inland. Rapid expansion of the beachhead was vital to permit the massing of supplies and reinforcements. Both expansion and reinforcement were necessary to defend the lodgment against the expected full-scale enemy counterattacks which, it was thought,

U.S. Commanders. Left to right: General Bradley, Gerow, Eisenhower, and Collins.

might come any time after D plus 3 and would almost certainly come during the first week.

General Eisenhower toured the assault area by mine layer with Admiral Ramsay on 7 June and ordered that the immediate tactical plan be altered to give priority to a concerted drive by both corps to link up through Isigny and Carentan. General Bradley gave orders accordingly during the afternoon of 7 June. For VII Corps the changed priority resulted in assigning to the 101st Airborne Division the sole task of capturing Carentan with reinforcements to be provided if necessary. V Corps gave the 9th Division the primary mission of seizing Isigny while the 1st Division continued the push east to join with the British and south to expand the beachhead.29

Plans for the employment of the 29th Division were discussed that evening at General Gerhardt’s command post in a rock quarry just off OMAHA Beach. (See Map XV.) The mission of taking Isigny was given to the 175th Infantry; it was to drive between the 116th and the 115th straight for its objective while the other two regiments cleared either flank of the advance. The 747th Tank Battalion (less Company B) was attached to the 175th Infantry and the attack jumped off that night. Advancing along the Longueville-Isigny road with tanks leading the columns of infantry, the regiment captured la Cambe before daylight and met its first real resistance about three miles west of that town. Antitank guns knocked out

one tank in front of the town and artillery fire disabled six more to the west. However, isolated enemy resistance, here and in other villages north and south of the Isigny road, was overrun, in some cases with the aid of naval fire. There was no organized resistance in Isigny itself, and it was entered and cleaned out during the night of 8-9 June. The town was partially gutted and burning from heavy naval bombardment.

The speed of the 175th Infantry’s advance collapsed the left flank of the 352nd Division and opened a hole in German lines comparable to the disintegration at Bayeux. The sector overrun was the responsibility of the 914th Regiment and had contained, in addition to the remnants of that regiment, a battalion of the 352nd Artillery Regiment and the 439th Ost Battalion. In the Grandcamp area, where the 116th Infantry was attacking, were additional units of the 914th Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the 1716th Artillery Regiment which manned fixed coastal artillery positions there. General Kraiss recognized that in view of the increasing pressure on his center and right he could not expect to hold with his left. At about the same time that he ordered the 30th Mobile Brigade and 726th Regiment to pull out of the Drôm corridor, he gave similar orders to the 914th Regiment. They were to fight to hold all positions during the day but withdraw the bulk of their forces at night south of the Aure. A small bridgehead was to be held at all cost northeast of Isigny. The isolation of the various units in the Grandcamp-Isigny area as well as the presence of valuable artillery pieces there complicated the problem of withdrawal. It required time to organize and carry out. No time was granted. The 914th Regiment found itself unable to offer effective resistance on the road to Isigny. The battalion of the 352nd Artillery Regiment had to pull out in such a hurry that its guns were abandoned, thus reducing division artillery for the fighting on 9 June to fourteen guns. The Ost battalion which was supposed to blow the bridge at Isigny across the Aure retreated without doing so.

The fall of Isigny meant that the 352nd Division could no longer block the corridor between the American bridgeheads. The 914th Regiment was ordered to organize a defense south of the Aure in the vicinity of Hill 35 near la Madeleine to prevent the division’s left flank from being rolled up. Kraiss counted on the Aure inundations to cover the gap in his lines between Isigny and Trévières30

While the main 29th Division attack gathered momentum that carried it without pause to its objective, both the 115th and 116th Infantry Regiments had cracked resistance in the coastal area, and virtually completed the seizure of the whole of the high ground north of the Aure River by the end of the day. The troops of the 115th met almost no resistance, although lack of transport brought them tired and without rations to their objectives overlooking the river. The 116th Infantry, reinforced with Rangers and two companies of tanks, and supported by destroyer fire, achieved the relief of the Rangers on Pointe du Hoc before noon and then proceeded to Grandcamp where, because of a canalized approach over a flooded area, it ran into a nasty fight lasting until dark. One battalion

St. Côme-du-Mont area

Picture on this page merged with previous page

of the 116th had been detached to sweep south of the main regimental advance toward Maisy. The Maisy position was taken on 9 June and the rest of the area mopped up to the Vire River.

With dispatch V Corps had completed its part of the drive to join the American beachheads. The 101st Airborne Division had a much harder time. (Map XVII) After the failure of the 506th Parachute Infantry (Colonel Sink) on 7 June to wrest St. Côme-du-Mont from the 6th Parachute Regiment, a much larger attack was mounted the following day. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 506th were reinforced with the 3rd Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry,31 the 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry, eight light tanks, and the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. The glider battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Ray C. Allen, on the left wing of the attack was to pass to the east of St. Côme-du-Mont, proceed down the main highway, and blow the bridges on the Carentan causeway. Colonel Ewell’s battalion of the 501st was to attack to the south of St. Côme to cut the highway there while Colonel Sink’s two battalions (506th) drove in column directly into the town. Behind effective artillery preparatory fire followed by a rolling barrage, the attack jumped off at about 0500.32 The glider battalion bogged down in the hedgerows. But Colonel Ewell’s men, despite considerable confusion and intermingling of units, reached their objectives south of St. Côme within three hours. In the meantime the battalions of the 506th pressed against the town from the east and artillery continued to fall heavily on the German defenders. In the first hour and a half, the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion fired about 2,500 rounds of 105-mm. high explosive.

The brunt of the U.S. attack was borne by the 3rd Battalion, 1058th Regiment, which on 7 June had been reinforced by two companies of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Parachute Regiment, from Carentan. Early in the morning, the 1058th men under heavy artillery fire began to show signs of cracking. Von der Heydte, still in charge of the defense, had no more reserves to bring up. Observing that men of the 1058th were beginning to straggle in retreat westward and having lost contact with the 1058th battalion headquarters, von der Heydte decided to pull out his own units and such troops of the 1058th as he could contact. The withdrawal involved some severe fighting with Ewell’s battalion posted south of the town, but eventually the majority of the Germans got out to the west and retreated on Carentan following generally the axis of railroad embankment.

This route was also taken during the day by the 2nd Battalion, 6th Parachute

Regiment, pulling back from north of St. Côme. With surprising ease the 2nd Battalion disengaged and streamed southward. Most of the men swam the Douve and arrived in Carentan with few losses. There von der Heydte with the bulk of two battalions plus elements of the 1058th Regiment organized his defense. Late on 8 June he had learned that Isigny had fallen and, primarily concerned with possible attack against Carentan from the east, he at first placed the whole 2nd Battalion on that side of the city.33

The U.S. 101st Airborne Division, meanwhile, with the occupation of St. Côme-du-Mont, completed the clearing of the enemy north of the Douve and east of the Merderet. Preparations began at once for an all-out attack on Carentan from the north. In preparation for that attack, the 101st Airborne Division, by the night of 8 June, had grouped three regiments along the Douve with a fourth regiment assembled in reserve near Vierville. The 502nd Parachute Infantry was placed in line on the right flank from the junction of the Douve and Merderet Rivers to Houesville. The 506th Parachute Infantry was assembled astride the Carentan highway, and the 327th Glider Infantry, which had come in by sea, relieved elements of the 506th and 501st Parachute Infantry Regiments at la Barquette and le Port. The 501st Parachute Infantry was in reserve.

The scheme of this attack had been worked out by the division in England. It appeared then that the only feasible route of attack was across the river flats in the vicinity of Brevands. Accordingly VII Corps on 8 June ordered attack in this zone. On 9 June, however, Colonel Sink led a patrol across the causeway toward Carentan. He was fired on and returned before reaching the city. The reports he sent back were apparently misinterpreted to indicate that Carentan was only lightly held. It was therefore considered possible to make a two-pronged attack across the causeway and through Brevands to envelop the city.34

The final plan was for the 327th Glider Infantry to make the main effort on the left, crossing the Douve near Brevands to clear the area between Carentan and Isigny and join with V Corps near the highway bridge over the Vire. Since the key to possession of this objective area was Carentan, the 327th planned to use the bulk of its force in an attack on the city from the east. At the same time the 502nd Parachute Infantry, relieved of its defensive mission on the right flank by the 501st, would cross the causeway over the Douve River northwest of Carentan, bypass the city on the west, and seize Hill 30. To secure Carentan after its capture, the 101st Airborne Division had the additional mission of occupying the high ground along the railway west of the city as far as the Prairies Marécageuses.

The causeway over which the 502nd Parachute Infantry was to attack was banked six to nine feet above the marshlands of the Douve and crossed four bridges over branches of the river and canals. One of the bridges was destroyed by the Germans. Difficulties in repairing this under fire forced postponement of the right wing of the division attack, first scheduled

Carentan Causeway. In foreground is northwestern tip of Carentan. Circles indicate position of bridges.

for the night of 9-10 June. It was the middle of the afternoon of 10 June before the 3rd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole) advanced over the causeway single file. The men moved in a low crouch or crawled, and it took three hours for the point to cross three of the bridges. Then the enemy opened fire from a farmhouse and hedgerows, methodically searching the ditches with machine guns. At the fourth bridge a Belgian Gate had been drawn so far across the road that only one man at a time could squeeze by it. Under cover of artillery fire, which all afternoon worked on enemy positions, this maneuver was tried. Six men made it; the seventh was hit, and the attempt was abandoned in favor of building up additional fire. Mortars were brought forward. The stalemate, however, lasted until midnight while enemy fire and a bombing and strafing attack after dark took heavy toll of the thin battalion line stretched across the causeway. After midnight, resistance slackened and three companies were able to filter men through the bottleneck and across the last bridge where they could deploy on either side of the highway.

The nub of the opposition seemed to be a large farmhouse to the west of the road on ground that rose sharply from the marshes. In the morning of 11 June after attempts to knock this out with artillery had failed, Colonel Cole, battalion commander, ordered a charge which he and his executive officer, Lt. Col. John P. Stopka, led. Followed at first by only a quarter of their 250 men, Cole and Stopka ran through enemy fire. The charge gathered momentum as more men got up and ran forward. The farmhouse was not occupied but the Germans had rifle pits and machine gun emplacements in hedgerows to the west. These were overrun and the Germans killed with grenades and bayonets.35

The heavy casualties and disorganization of the battalion prevented Cole from following up his advantage. Instead he sent word back to have the 1st Battalion of the regiment pass through and continue the attack south. The 1st Battalion, which was near the fourth causeway bridge when request came to move forward, reached Colonel Cole’s position through heavy fire. But since it was as hard hit and disorganized as the 3rd Battalion it was in no better condition to move on. Both battalions set up a defensive line and held on during 11 June against determined German counterattacks, which on one occasion threatened to break through. The 2nd Battalion took over the line during the night, but the 502nd Parachute Infantry was too exhausted to renew the attack and the 506th Parachute Infantry was sent to its relief.

While the bitter battle of the Carentan causeway was being fought, the left wing of the 101st Airborne Division attack had carried south and made tenuous contact with V Corps units east of Carentan. In the early morning hours of 10 June all three battalions of the 327th Glider Infantry were across the Douve near Brevands. One company, reconnoitering to Auville-sur-le Vey, met the 29th Reconnaissance Troop and Company K of the 175th Infantry. The 175th Infantry (9th Division) had followed up the capture of Isigny by sending Company K to take the

Vire bridge at Auville-sur-le Vey while the main body of the regiment moved toward objectives in the Lison-la Fotelaie area to the south. The bridge was found to have been destroyed and the company, reinforced with the reconnaissance troop and a platoon of tanks, fought most of the day of 9 June to force a crossing. They forded the river late in the afternoon, seized Auville-sur-le Vey, and held it during the night while engineers built the bridge behind them. Contact with the airborne unit the next day was only the beginning of the link between the corps. A savage fight remained for the possession of Carentan as well as some confused and costly maneuvering to clear the ground to the east.

The Germans meanwhile made plans to reinforce the city, whose defense Field Marshal Rommel considered vital not only to prevent the junction of the American beachheads but to forestall any attempt by General Bradley to cut the Cotentin by a drive southwest across the Vire toward Lessay and Périers. As immediate stopgap measures LXXXIV Corps sent von der Heydte two Ost battalions and remnants of the defenders of Isigny. He placed these troops, of limited combat value, on the east side of the city and concentrated the two battalions of his own regiment on the north. But this was still admittedly a weak defense for such a critical objective. Late on 9 June Rommel decided to commit the II Parachute Corps (Meindl), which was on its way up from Brittany, to counter this threat.36 Under Meindl’s corps, the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division (Generalmajor der Waffen-SS Werner Ostendorff) was assigned the primary mission of blocking an Allied westward thrust. Ostendorff’s orders were to move to positions southwest of Carentan prepared to counterattack south of the city.

These plans were frustrated by the difficulty of getting the units into position. On 8 June the move of Meindl’s troops was reported greatly delayed by air attack and sabotage. Ostendorff’s division had been forced by continued severe air attacks on the railroads to make most of its march northward by road. Shortage of gasoline then further delayed the move. By the end of 11 June only Ostendorff’s forward elements had reached their assembly areas southwest of Carentan.37

While awaiting reinforcements and holding off the concentric attacks of the 101st Airborne Division, von der Heydte in Carentan was running desperately short of ammunition. It was impossible to bring up resupplies by truck in view of the shortage of motor transport and gas and Allied air interdiction of the roads. OB WEST at last considered the need so critical that an air supply mission was flown during the night of 11-12 June and eighteen tons of infantry ammunition and 88-mm. shells were dropped to von der Heydte on a field south of Raids, some seven miles southwest of Carentan.38 This, the first air supply mission attempted by the Germans in Normandy, came too late to save Carentan.

On 10 June the bulk of the 327th Glider Infantry pressed in on Carentan from the northeast. Its initial objective

was to seize the highway and railroad bridges over the Vire-Taute Canal and so seal off the city from the east. The regiment advanced rapidly until at 1800 it came within five hundred yards of its objective. Stopped by enemy fire from the east bank, it reorganized and resumed the drive with two battalions abreast on either side of the Carentan–Isigny highway. The men fought until midnight through those last five hundred yards and succeeded at last in clearing the enemy from the east bank and digging in along the hedgerows beside the canal.

Col. Joseph H. Harper, who had taken command of the 327th Glider Infantry that afternoon, now decided against any attempt to rush the bridge in favor of moving a portion of his force north to cross on a partly demolished footbridge and approach Carentan through the wooded area along the Bassin à Flot. Most of the regiment would hold positions along the canal and support the attack by firing into the city. After a patrol had repaired the footbridge, three companies crossed under enemy mortar fire during the morning of 11 June, but were unable to advance more than a few hundred yards before they were stopped by enemy fire from the outskirts of Carentan.

In the evening of 11 June, First Army decided to commit another regiment and coordinate the two wings of the attack by forming all units into a single task force under command of Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, artillery commander of the 101st Airborne Division. The 506th Parachute Infantry was to take over from the 502nd the attack on the west toward Hill 30. Colonel Harper would continue to hold east of Carentan while attacking with a battalion plus one company along the Bassin à Flot. The 501st Parachute Infantry was to be taken from defensive positions north of the Douve and committed through the Brevands bridgehead. It was to drive east of the 327th Glider Infantry in a wider envelopment of Carentan designed to link with the 506th Infantry south of the city at Hill 30.

Gerow’s corps was drawn only slightly into this new effort. The bulk of V Corps continued the drive south to expand the beachhead. But inasmuch as the 101st Airborne Division task force was now wholly absorbed with the envelopment of Carentan it became necessary to use V Corps units to protect the east flank in the area between the Douve and Vire Rivers. The bridgehead at Auville-sur-le Vey was reinforced on 11 June by the 3rd Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division, which had begun landing on 9 June. In addition, on 12 June, the 175th Infantry was ordered to reconnoiter in force in the region of Montmartin-en-Graignes and seize two bridges over the Vire-Taute Canal, to secure the still insubstantial link between the corps from German counterattack from the south.

The city of Carentan blazed during the night under concentrations of naval fire, artillery, mortars, and tank destroyer guns. The attack of the 506th Parachute Infantry got started at 0200,12 June, and advanced rapidly against slight resistance. On his objective, Hill 30, Colonel Sink at 0500 ordered the 2nd Battalion to attack into Carentan. Despite interdictory artillery fire and some spasmodic machine gun fire the battalion entered the city within a few hours. At the same time the 327th Glider Infantry on the northwest attacked out of the woods at Bassin à Flot and

Carentan and Hill 30 Area

[Picture merged onto previous page]

drove rapidly into the center of town. The two units met at about 0730. Only enemy stragglers remained to contest possession of the city. While the concentric attack squeezed into the city, the wider envelopment made equally rapid progress as the 501st Parachute Infantry swept down east of Carentan and made contact with the 506th half an hour after the entry into the city.39

The closing of the trap had captured the objective, but few enemy prisoners were caught. The fact is that von der Heydte had pulled out of the city before dark on 11 June without being observed and had set up a defense line to the southwest.40 This new resistance line was discovered in the afternoon (12 June) when General Taylor attempted to push the attack to the southwest. His objective was to establish a deep defense of Carentan hooked up on the right with the 82nd Airborne Division, which was driving south across the Merderet in the direction of Baupte.41 The 506th Parachute Regiment thrust out on the axis of the Baupte road while the 501st attacked along the Périers road. But both bogged down and by the end of the day had reached out only a few hundred yards from the line of departure near Hill 30.

The simultaneous effort to secure the ground east of Carentan on 12 June proved just as inconclusive as the push westward. In the morning a task force consisting of two companies of the 175th Infantry, reinforced by mortars and heavy machine guns, crossed the Vire. Enemy outposts of the newly arrived mobile Kampfgruppe of the 275th Division42 observed the crossings but made no serious attempts to interfere with them. Not far from Montmartin, however, the Germans ambushed and badly cut up one company on a hedgerow-lined road. Remnants of the company withdrew north of Montmartin to re-form and there joined with the remainder of the task force. Into this position in the afternoon came the 1st Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry, which with the 2nd Battalion had attacked south early in the afternoon after the capture of Carentan. The combined force then secured high ground south of Montmartin. The 2nd Battalion in the meantime had been checked at Deville to the northeast. During the night Colonel Goode, 175th commander, took a company across the Vire to attempt to reinforce General Cota but stumbled into a German bivouac. Colonel Goode was captured. Remnants of his force straggled back across the Vire.43

The fighting southeast of Carentan had been on a very small scale and was not in itself important, but, in the course of it, reports came in to General Bradley’s headquarters of a strong concentration of German forces in the area, including the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. Signs pointed to a possible enemy build-up of three divisions with the probable mission of counterattacking in force between Carentan

and Isigny where, General Bradley pointed out, “we are very weak.”44 As communications were temporarily out between First Army and V Corps, Bradley sent a letter by courier to Gerow ordering him to move a battalion of tanks and a battalion of armored infantry from the 2nd Armored Division into the Montmartin-en-Graignes area “prepared for action to the south.” The movement was to be completed by daylight and coordinated with the 327th Glider Infantry. In addition Bradley ordered that the 116th Infantry be held in reserve for possible commitment on the right of the 175th. By 0630 of 13 June the 2nd Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, in accordance with these orders had joined the 3rd Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry, already west of the Vire, and the task force was ready to move south. The move, however, did not take place, for by morning Carentan was being threatened from the southwest rather than the southeast and the armored task force was diverted to go to the support of the 506th Parachute Infantry.

After the fall of Carentan, the Germans planned to counterattack with the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division to retake it. But the attack was delayed on 12 June because the battalion of assault guns, which moved north by train, was held up in the assembly areas by air attacks. With the guns in position on the morning of 13 June, Ostendorff attacked. The attack hit both the 506th and 501st Parachute Infantry Regiments at about 0630 and during the morning drove them back to within 500 yards of Carentan. (Map 4) The 502nd Parachute Infantry was brought down to Carentan to reinforce the defense of the 506th. At 1030 the armored task force arrived and in the early afternoon the 101st Airborne Division resumed the initiative. The 502nd drove through the 506th, and the 501st continued on its mission of the day before. With close support from the 14th Armored Field Artillery Battalion the enemy was thrown back with estimated losses of 500 men. A defensive position was secured along the road from Baupte to the Carentan–Périers highway.

On the east the company of the 175th Infantry beleaguered at Montmartin was pulled out and Colonel Harper established a line north of the main railroad linked with the 29th Division to the east. Now V and VII Corps were securely joined, although the strip between them still lacked depth for adequate communications and defense. First Army, however, now had resources to deepen it and on 13 June the mission was assigned to XIX Corps, which became operational the next day.

Operations to fuse the two First Army beachheads have been traced through to their conclusion because they form a single story with few direct contacts with what was going on elsewhere in Normandy. The actions described were considered by the high command as of first importance. They did not, however, constitute a main effort by the First Army. Larger forces were being used simultaneously to expand the beachhead westward and southward. Virtually the whole of V Corps during the week of 8-14 June was pushing south through the bocage country making rapid progress against a disintegrated German defense.

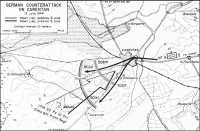

Map 4: German Counterattack on Carentan

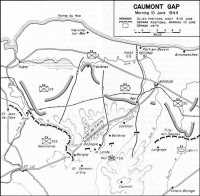

The Caumont Gap

From its D-Day objectives reached on 8 June, V Corps ordered a three-division attack designed simply to push out the lodgment area in conformity with the advance of the British on the left. The 2nd Division (Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson),45 which had begun landing the evening of 7 June, had enough units ashore by midday of the 9th to be operational and it took over 5,000 yards of the 1st Division front north of Trévières. (See Map XVIII). Here the main effort of the corps was to be made with the final objective of seizing the Forêt de Cerisy, high ground which always figured prominently in V Corps plans as a possible assembly area for enemy counterattack forces and as ground dominating the whole corps beachhead. The 1st Division on the east was to put its main effort on its right and advance to seize three towns: Agy, la Commune, and Vaubadon, on high ground along the St. Lô–Bayeux highway. The 29th Division, on the other flank, would seize the north bank of the Elle River from la Communette west to the Vire. A portion of its forces, as already noted, would operate west of the Vire to establish contact with VII Corps. Each division was to attack with two regiments abreast and each was to leave all or part of the third regiment prepared to defend

the D-Day positions. Positions gained by the attack would be organized for defense in depth. Both latter measures were insurance against enemy counterattack in strength, a contingency that continued to figure prominently in Allied calculations.

Enemy resistance broke first on either flank of the attack and then disintegrated all through the corps zone. Despite this collapse, however, certain units had hard fighting on 9 June. The 29th Division, after clearing Isigny in the morning, pushed south with the 175th Infantry on the right, the 115th on the left.46 The 175th Infantry, having smashed the 914th Regiment in its rapid seizure of Isigny, advanced southward against only scattered opposition. Near la Forêt, 352nd Division stragglers defending a supply dump held off the American advance long enough to permit the evacuation of the bulk of the supplies. This action cost the Germans an estimated 125 killed. The 175th Infantry then moved on down to its objectives in the Lison-la Fotelaie area before nightfall.

The 115th Infantry, during the night preceding the attack, reconnoitered crossings of the Aure River. The crossing promised to be difficult since the river flats were flooded to a width of half a mile to two miles. Although nowhere deep under water they were marshy and crisscrossed by drainage ditches. During the night 2nd Lt. Kermit C. Miller of Company E took a platoon across south of Canchy. Entering Colombières on the south bank, which had been hard hit by American artillery, Miller’s patrol caught a considerable force of Germans by surprise, cut down about forty of them, and took a dozen prisoners. Thanks to this action the regiment’s crossing the next day was unopposed, for Colombières turned out to have been the only defended locality on the south bank of the river within range of the Canchy crossing. The lack of opposition was extremely fortunate, for the physical difficulties of crossing the swampy flats made progress very slow and exposed the troops for several hours as they struggled through the mud and waited for improvised bridges to span the few impassable streams. Two battalions were across by 1100. The third followed after enemy fire frustrated an attempt to cross a narrower portion of the river valley farther east. Once across, the 1st Battalion moved to Bricqueville and the 3rd Battalion farther south to la Folie. Neither had met serious opposition. But the 2nd Battalion ran into trouble from the start. Turning west to clean out the Bois de Calette, from which enemy riflemen were harassing bridging operations at the la Cambe-Douet causeway, the battalion brushed with enemy bicycle troops near Vouilly. Although the wood was not occupied in force the battalion took three hours to flush snipers from the thick brush. Then heading south for le Carrefour it took a wrong turning that added three miles to the six-mile march to its objective. Thoroughly exhausted the troops reached their initial objective at 0230, 10 June. Leading units moved off the road. Reconnaissance to establish a temporary defensive position was difficult in view of the condition of the men and the dark night. Most of the men simply dropped to the ground and were almost at once asleep.

While the rear of the column still waited on the road to move into the bivouac area, an enemy infantry and armored vehicle column blundered down the road in retreat from the Aure valley fighting. A machine pistol was fired. American rifle shots replied. The enemy swung into action, sprayed the road with machine gun fire, and sent armored vehicles (probably self-propelled 88-mm. guns) down the road, firing into hedgerows and fields. The 2nd Battalion men, scattered, confused, and disorganized, could offer no effective resistance. One man had presence of mind to take a bazooka and attack the enemy guns, knocking out two of them. But the greater part of the battalion—its commander, Lt. Col. William E. Warfield, killed—dispersed in small groups and retreated north and west during the night. In the melee 10 men were lost, including 11 officers. The next day the battalion was reorganized with 110 replacements, moved back into the line, and the 115th Infantry proceeded to its objectives on the Elle River without opposition.

On the opposite flank of the corps attack the left wing of the 1st Division drove forward against rapidly collapsing resistance. The 26th Infantry reached its objectives, Agy and Dodigny, at night. The 18th Infantry, held up initially by a single enemy strong point, at length bypassed it leaving it to be cleared by the reserve battalion. Thereafter moving rapidly, with strong artillery support on known enemy positions, possible assembly areas, and roads, it continued to advance through the night. It met no enemy after midnight and arrived by morning abreast of the 26th Infantry. During 10 June it moved down to its objectives on the St. Lô-Bayeux highway. Only the 3rd Battalion at the edge of the Forêt de Cerisy met resistance.47

In the center of the corps zone the newly landed 2nd Division had a harder time, in part because it hit the center of the 352nd Division, which despite the collapse of both wings continued to hold out during 9 June in strong defenses about Triévières and in part because it lacked most of its artillery, transportation, communications (wire and radios), machine guns and mortars, as well as a large part of its supporting troops.48 For the attack of 9 June, one company of tank destroyers and one company of tanks were attached.

While the 38th Infantry attacked Triévières from the north, the 9th Infantry struck to the east to cut the Trévières–Rubercy road. The 9th Infantry had relieved the 18th Infantry at Mandeville and Engranville. The line of departure for its attack was due east of Trévières but the 2nd Battalion was at Engranville north of the Aure at 1100 when it received orders to jump off. It spent the whole day fighting to the line of departure, unable without heavy weapons to overcome enemy flanking fire from the direction of Trévières. By midnight, however, it reached the initial objective, Rubercy. The 3rd Battalion, starting from the Mandeville area, fought down the road toward

Rubercy but made very slow progress and was still short of the objective by dark. A gap of at least 4,000 yards separated the battalion from the 1st Division on the left. This was covered only by patrols of the 18th Infantry.

The attack on Trévières by the 38th Infantry ran into difficulties aggravated by its total lack of mortars and machine guns, the hedgerow terrain, and a stubborn though not numerous enemy. The Aure River had been selected as the line of departure, but both the 2nd and 3rd Battalions ran into opposition before reaching it. Progress was slow. The men were continually pinned down by enemy fire difficult to locate among the hedgerows and still more difficult to neutralize with only light infantry weapons. The attacking troops were given direct support by accurate fire from two batteries of the 38th Field Artillery Battalion. But the attack was kept moving chiefly by bold leadership. The success of the 3rd Battalion in crossing the Aure under heavy German machine gun fire was due at least in part to the intrepidity of Capt. Omery C. Weathers of Company K who led his men through the fire at the cost of his own life.49 Col. Walter A. Elliott, the regimental commander, unable to depend on communications in the typically fragmental maneuver of groups of men through the fields and orchards, spent most of the day moving between his battalions pushing the attack forward. Late in the afternoon the regiment, still short of its objective, was ordered by General Robertson to continue the attack to take Trévières that night. By midnight the 2nd Battalion had occupied the town except for a small strong point on the southern edge which was cleaned out the following morning.50

The Germans’ abandonment of Trévières however, was not due primarily to the efforts of the 38th Infantry. The 352nd Division with both flanks torn open had at last decided to pull out of an untenable position. At about 1900, 9 June, General Kraiss reported his hopeless situation to General Marcks at LXXXIV Corps and received orders to withdraw far to the south to establish a defense along the Elle River from Berigny to Airel. The withdrawal was to take place during darkness and to be completed by 0600, 10 June. For the defense of this new line of about ten miles, General Kraiss had 2,500 men, 14 artillery pieces, 16 antiaircraft guns, and 5 tanks.51

The withdrawal of the 352nd Division allowed the 2nd Division on 10 June to march to its objectives west and south of the Forêt de Cerisy. About ninety enemy stragglers were rounded up during the advance. Both the 1st and 2nd Divisions spent the day of 11 June virtually out of contact with the enemy, reorganizing the ground won and preparing for a new attack. The 1st Division units had made no advances since noon on 10 June. The only fighting on 11 June took place at the southern tip of the Forêt de Cerisy where the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry, fought to dislodge a stubborn group of enemy well dug in at the Haute-Littée crossroads. Even patrols probing far in