Chapter 10: The Capture of Cherbourg (8 June–1 July)

Securing the North Flank

On 18 June, when V Corps went on the defensive in front of St. Lô, VII Corps on First Army’s right had just completed a brilliant victory-the cutting of the Cotentin-which split the German Seventh Army and sealed the fate of Cherbourg. The victory, swift and dramatic in the final stage, was preceded by ten days of hard slugging in order to break out the ring which the Germans pressed around the D-Day beachhead.

Some of the hardest fighting during the first week of the invasion took place on the north flank of VII Corps where the 4th Division, together with the 505th Parachute Infantry (82nd Airborne Division) on its left, fought to take the corps D-Day objective: the ridge line, Quinéville—Montebourg-le Ham, from the coast to the Merderet River. (Map XXI) The enemy in this area had the advantage of defending higher ground which rises gradually northward to the Quinéville-Montebourg ridge. Field fortifications were prepared throughout the area making maximum use of the network of hedgerows. In addition, the fully developed fortified areas at Azeville, Crisbecq, Ozeville, and along the beach as far as Quinéville provided strong nodes of defense. It will be remembered that the 4th Division had butted up against the southernmost defenses on 7 June but had been unable to subdue them.

After the D-Day lodgment area had been cleaned out on D plus 1, VII Corps organized a full-scale attack to the north. It was essential to reach the Quinéville-Montebourg line in order to knock out enemy batteries which kept the UTAH landing beaches under artillery fire as well as to widen the base of attack for a drive westward across the peninsula.

Four regiments attacked abreast on 8 June: the 505th Parachute Infantry and 8th Infantry west of the Montebourg highway with objectives between the Merderet River and Montebourg, and the 12th and 22nd Infantry Regiments in the zone east to the coast with final objectives along the Quinéville-Montebourg ridge.

The 8th Infantry and 505th Parachute Infantry made slow but steady progress under harassing opposition during 8 June to reach a line generally from the Montebourg highway through Magneville to the Merderet. Probing attacks farther north before dark revealed what seemed to be a prepared defense along the tributary of the Merderet just north of Magneville. Centers of resistance were apparent at the Magneville hangar and at Ecausseville. Along the creek bank machine guns

were dug in and artillery was registered on all routes of approach.1

These positions were actually part of the defense set up by General von Schlieben after the unsuccessful counterattack on Ste. Mère-Eglise on 8 June. The main German defensive line, however, was to the north along the railroad from le Ham to Montebourg and thence northeast following the main highway to Quinéville. Between 9 and 12 June troops were gathered to man this line from miscellaneous units of the 709th, 243rd, and 91st Divisions and the Seventh Army Sturm Battalion and formed into three Kampfgruppen of nominally regimental size. The east wing of the line rested securely on the high ground at Quinéville extending to the sea, but the west flank was open. It was planned that the 77th Division would tie in on the west as soon as that unit, still moving up slowly from the south, should arrive.2 The chief strength of the German defense in the meantime was its unusually strong artillery support. In addition to the artillery that von Schlieben had on 8 June (a battalion of the 243rd Artillery Regiment and two heavy motorized battalions, the 456th and 457th), on about 9 June two Russian 122-mm. guns were moved from Carteret on the west coast of the Cotentin to northwest of Quinéville. At the same time the six French 155-mm. guns of the 3rd Battalion, 1261st Artillery Regiment, were shifted from Fontenay to positions about half a mile west of Lestre. In addition the guns of two fixed coastal battalions at Videcosville and Morsalines (about four miles north of Quinéville ridge) were removed from their bases and mounted on carriages so that they could be used in the land fighting—the job being done by ordnance personnel working day and night under almost constant American fire. The effectiveness of this comparatively large aggregation of guns in support of the German defense was qualified, however, by a shortage of ammunition and by the fact that the crews were submitted to almost constant Allied naval bombardment and air attacks.3

Coordinated American attacks on 9 June had varying success. The 8th Infantry at the cost of hard fighting and heavy losses made significant gains in overcoming some of the points of heaviest German resistance. Company L took the hangar positions at Magneville by charging across open fields in the face of heavy grazing fire and at the cost of many lives. In the meantime the 2nd Battalion, assaulting Ecausseville, which was reported to be lightly held, had its leading company chewed by enemy artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire that caught it in a hedgerowed trail. The 1st Battalion, however, took up the fight late in the day and fared better. With two platoons of tanks in the lead the 1st Battalion moved up the road east of Ecausseville. At the crossroads east of the town, tanks shot up a group of houses from the rear and enabled the infantry to move in and take 100 prisoners. Ecausseville itself held out as enemy 88-mm. guns prevented the tanks from entering.

But the outflanking maneuver was successful, and during the night the Germans withdrew to their main defensive positions.

The 8th Infantry then advanced rapidly and by the night of 10 June all three battalions had reached objectives along the le Ham-Montebourg highway. But attacks toward the le Ham-Montebourg railroad line were met with very heavy enemy fire. The entire regiment therefore dug in east of the highway and established a defensive line which it was to hold until the beginning of the major drive north to Cherbourg on 19 June.

The simultaneous attack on 10 June of the 505th Parachute Infantry on the left proved more difficult, largely because of the nature of the tactical problem. The regiment was to take the Montebourg Station and le Ham. The latter town was the western anchor of the German defense line and was situated on the Merderet between two small tributaries. The plan of attack was for one battalion to seize the Station and defend to the north while the 2nd came up behind and then swung west between the creeks to le Ham.

The first part went well. Under heavy artillery rolling ahead of the attack, the 1st Battalion reached its objective within six hours of the jump-off. The 2nd Battalion, following the 1st slightly farther north than intended in order to avoid flanking fire from the left, turned to attack le Ham along the axis of the Montebourg road. The enemy troops at le Ham, some of whom had retreated there from the Station, fought stubbornly as they were pressed into their last stronghold. The attack was halted at dark still about a thousand yards from its objective.

On the morning of 11 June Colonel Ekman, regimental commander, ordered the 2nd Battalion to employ a holding attack on the north of le Ham while the 2nd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry, thrust at the enemy from the east. The attack of the latter battalion, though prepared by a fifteen-minute artillery concentration and covered by smoke, nevertheless cost heavy casualties as troops struggled through open fields and swamps. The battalion was halted short of its objective, weakened by casualties and low in ammunition. Then the enemy began to withdraw. A new attack was mounted and the battalion, widely deployed, moved in against a badly shaken covering force. Passing abandoned German field pieces the Americans entered le Ham to find it deserted. The bridge over the Merderet west of le Ham was secured, and during the rest of the day the whole position was organized for defense. On the morning of 13 June the 505th Parachute Infantry was relieved by a battalion of the 359th Infantry of the 90th Division.

The attacks of the 8th and 505th Infantry Regiments, which have been traced through to their conclusion, were only part of the general advance of the 4th Division northward which in four days pushed back the enemy into his last prepared defensive positions south of the Cherbourg Landfront (landward fortifications of the port). In the center of the division zone Colonel Reeder’s 12th Infantry, after losing 300 men in a violent fight around Emondeville during 8 June, broke loose and moved up to Joganville where it destroyed a German resistance point. Reeder then advanced another 2,000 yards. The next day his 3rd

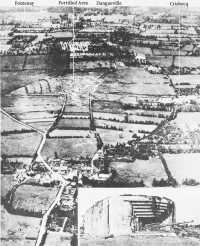

Crisbecq Fortification. In foreground is village of St. Marcouf. Inset: One of the forts.

Battalion sped north to just short of the regimental objective, 1,500 yards northeast of Montebourg, and far in advance of all other 4th Division units.

On the division’s right the attack of 8 June against the Crisbecq and Azeville fortifications repeated the experience of the day before. Two companies of the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry, led the assault on Crisbecq after a twenty-minute preparation of naval fire, together with field artillery and mortar concentrations. Advancing then under a rolling barrage which the infantry followed at about 200 yards, and under indirect fire from heavy machine guns, the two companies reached the edge of the fortified area with few losses. The third company was then passed through to blow the concrete emplacements with pole charges. The assault sections, however, used all their explosives without materially damaging the concrete and then became involved in small arms fights with Germans in the communicating trenches. A counterattack on the left at last forced the battalion to withdraw to its starting point north of Bas Village de Dodainville. Action of the 2nd Battalion before Azeville was similar, and similarly unsuccessful.

Twice turned back, Colonel Tribolet, commander of the 22nd Infantry, on 9 June revised his tactics. He temporarily abandoned the assault on Crisbecq and concentrated on Azeville. The 3rd Battalion (less one company engaged in attacking beach defenses) was brought up to take over the mission of assaulting that position. While naval and artillery fire neutralized the Crisbecq guns, two companies circled to the west of the four Azeville blockhouses whose southern approaches had been rendered almost impenetrable by mine fields, barbed wire, and concrete one-man shelters. Although there were mines and wire on the west, too, the Germans here had not cleared fields of fire and apparently had made no preparations to cover this approach. The assaulting troops were thus able to cut their way through the wire and pick paths through the mines without removing them. Bazookas and one tank that managed to get through the mine fields opened fire on the nearest of the blockhouses but without effect. A demolition team then made three separate attempts to blow up the blockhouse. All three failed. It looked as though once more the attackers might run out of explosives and have to pull back. Then happened one of those minor miracles that may turn the course of battle. On orders of his company commander, Pvt. Ralph G. Riley took the last available flame thrower to “give it a few more squirts.” Reaching the blockhouse after running through enemy fire, Private Riley lighted his flame thrower with a match, as the firing mechanism failed, and trained the stream of blazing oil on the threshold of the door. The fire should have had no more effect than previous squirts. But it did. It hit some ammunition inside. Explosions followed. Within minutes a white flag emerged. When the firing ceased the German commander stepped out and surrendered the whole of the Azeville fortifications with their garrison of 169 men. Riley received the Silver Star. The capture of Azeville opened the way for continuing the attack north toward Quinéville. Even though Crisbecq and other known German prepared positions remained in action, General Barton,

Azeville Forts are located at upper left of photo on both sides of road. Inset: One of the forts.

in view of success all along his front, decided to bypass them and send a task force straight through to Quinéville.

But although each of the regiments of the 4th Division at the end of 9 June had succeeded in cracking determined enemy resistance no holes had been punched in the enemy’s main defenses. A task force of the 22nd Infantry4 under command of Brig. Gen. Harry A. Barber found that it was not at liberty to move through the Azeville gap for direct attack on the Quinéville positions. Germans held out in strength all along the right side of the proposed advance-at Crisbecq, Dangueville, Château de Fontenay, and Fontenay-sur-Mer. On the left, the enemy had scattered positions in the mile-and-a-half gap between the 22nd and 12th Infantry Regiments. Too weak to contain the enemy on its flanks and at the same time push ahead, and plagued by bad weather which prevented air support, Task Force Barber made little headway for the next three days.

On 12 June General Collins, VII Corps commander, decided to commit another regiment on the right to clear the fortified beach and coastal area and so free General Barber for his main mission of advancing to capture the Quinéville ridge. Collins was also anxious to take out the coastal batteries whose harassing fire on UTAH Beach threatened to slow down the unloading of supplies. Accordingly the 39th Infantry of the 9th Division, which had landed on 11 June, was committed in the zone roughly from the Fontenay-sur-Mer-St. Marcouf road where it relieved the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry.

The 39th Infantry (Col. Harry A. Flint) in part profited from the hard fighting of the three previous days which had seemed to batter unsuccessfully against the enemy’s fortifications. The 2nd Battalion found Crisbecq unoccupied, and pushed on to take Dangueville in the afternoon. Advances elsewhere were more heavily contested. The 1st Battalion cleared the beach between Taret de Ravenoville and Fort St. Marcouf, while the 3rd Battalion captured Fontenay-sur-Mer in a hard fight against an enemy whose resistance grew more stubborn as he was forced back against his main line on the Quinéville ridge.

Freed now for the attack north, Task Force Barber devoted its entire strength to the reduction of the Ozeville fortifications. Two battalions took up flanking positions from which they could deliver mortar, tank, and cannon fire on the enemy defenses while the 3rd Battalion, with a company of chemical mortars and a platoon of tanks, advanced behind artillery concentrations from two battalions. At the same time naval fire neutralized German guns at Quinéville. Bad weather again prevented the use of air, but the concentrated volume of fire was decisive. Ozeville in short order hung out the white flag. The close of the fight, however, was not to be capitulation. An American officer trying to stop the firing in order to receive the signaled surrender was shot down. Infuriated, the assault company rushed the enemy emplacements with bayonets and grenades and all but exterminated the garrison.

Capture of Ozeville was the signal for the 12th Infantry on the left to advance

to its objective on the Montebourg end of the Quinéville-Montebourg ridge. The 12th Infantry had actually reached this objective on the morning of 11 June but it was then far ahead of units on both flanks. It was therefore ordered back behind the Montebourg-St. Floxel road where it remained on the defensive until the attack on Ozeville seemed assured of success. Late in the afternoon of 12 June it reoccupied the heights of les Fieffes Dancel.5

The enemy from the Merderet to Montebourg had thus been forced back to the line of the railroad by the night of 12 June. Montebourg itself remained in enemy hands. Until 12 June General Barton felt that the limited forces at his disposal would not warrant involving any considerable numbers of them in street fighting. On that day, after reports that Montebourg was lightly held, he at last ordered Colonel Van Fleet to take the city, if it could be done cheaply.

Actually the Germans were prepared to defend Montebourg strongly as a key to the defense of Cherbourg. Located in the angle between the German line defending south under von Schlieben and the line of the 91st Division defending west, the city was ordered to be held with every available means. On 8 and 9 June twenty-five light French tanks and the 3rd Battalion of the 919th Regiment had moved in to the defense.6

When the 8th Infantry task force discovered the strength of the Montebourg garrison the attack was called off and a mixed force of infantry and armor of somewhat less than battalion size was formed to contain the city. The right-wing units of the 4th Division then set about completing their D-Day tasks. What remained was the capture of the Quinéville ridge. The 12th Infantry, which already occupied the western end of the ridge, was to hold there and protect the 22nd Infantry’s left flank while the 22nd advanced north and then east along the ridge toward Quinéville. At the same time Colonel Flint with the 39th Infantry would attack north along the beach and west edge of the inundations.

Progress of the attack during 13 June was disappointingly slow. The 39th Infantry made only small gains while Colonel Tribolet’s 22nd Infantry was able only to maneuver into position for attack in column of battalions down the ridge to Quinéville. On 14 June the attack was resumed. Tribolet’s three battalions fought their way to the nose of the ridge and captured two hills just west of Quinéville. The 3rd Battalion of the 39th Infantry in the meantime came up from the south and, when abreast of the 22nd Infantry, turned east. The plan then was for it to continue the advance on the town of Quinéville with the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry. Instead, Colonel Flint with permission of the division attacked alone, after a bombardment of Quinéville by thirty-six A-20’s.

Company K of the 39th led off the attack and at first moved rapidly. Supported by mortar fire the company entered Quinéville but at once ran into stiff opposition from Germans defending the beach positions east of the town. There was little room for maneuver and it was impossible to employ the other two companies without exposing them in open fields barred by wire entanglements.

Quinéville. Village is in foreground. At top of photograph along beach is Quinéville Bains.

Tanks could not advance because of an antitank gun on the beach and heavy enemy mortar fire. The answer was smoke. A concentration fell squarely on enemy positions and permitted Company K to push the attack to the beach fortifications. The enemy’s situation was then hopeless and he promptly surrendered. While the capture of Quinéville was accomplished, the 1st Battalion of the 39th Infantry, despite severe casualties from mines, had completed the clearing of the beach with the capture of Fort St. Marcouf.

The northern flank of VII Corps anchored on the Quinéville ridge was now secure. In the ensuing lull in the fighting the enemy would be allowed to build up slightly opposite the 4th Division but his attitude remained purely defensive. Actually, after the initial attempt to counterattack on 6 June, the Germans never could muster enough strength on this front to take the offensive. On the contrary, from 9 June they became increasingly concerned over their ability to hold and prevent a clean breakthrough to Cherbourg. On the 9th the 77th Division received orders to proceed to Valognes and at the same time General Marcks, the corps commander, secured the immediate release of two battalions from the Cherbourg Landfront.7 He also asked for air support, saying that the fate of his troops, pressed hard between Montebourg and Marcouf, depended on it. Third Air Force replied that bad weather made it momentarily impossible.8 Actually with all airfields in the vicinity of the coast unusable, Luftwaffe fighters were never able to intervene in the Cotentin battles.

While awaiting ground reinforcements, Marcks tried to straighten out the command situation in the Cotentin. Troops had been rushed hurriedly into battle and committed promptly on arrival to plug the defense wherever the weakness seemed most critical at the time. Reorganization became necessary. Marcks named Generalleutnant Heinz Hellmich of the 243rd Division to command a Kampfgruppe of these miscellaneous units along the Montebourg-Quinéville line. The formation of Kampfgruppe Hellmich simplified the chain of command, but at the lower levels it is probable that the mixed Kampfgruppe had considerably less cohesion in defense than regular units would have had.

On 10 June the advance elements of the 77th Division, consisting of about a battalion, arrived in the vicinity of Valognes. Two days later the bulk of the division was in position on both sides of the Merderet. General Dollmann expressed himself as satisfied that the situation was restored to balance on this portion of the front.9 Units of the new division relieved Kampfgruppe Hoffmann, which had been holding the western wing of the Montebourg line.10 But the restored balance was short-lived. Again success in the defense of one sector was almost immediately nullified by breaks in the line elsewhere. The Germans’

Montebourg line could hold only so long as their position on the west remained firm. U.S. VII Corps troops in the week following D Day hammered this position into crumbled ruins.

Attack to Cut the Peninsula

The drive north had reached only a little beyond D-Day objectives in a week of hard fighting. The delay had been caused chiefly by German success in bringing up considerable reinforcements to hold a line which the enemy command deemed vital to the defense of Cherbourg. On the VII Corps west flank on the Merderet River a similar delay of about a week in reaching D-Day objectives was caused principally by the original accidents that befell the airborne drops and by terrain difficulties in subsequent attempts to force the river crossing. Although the 91st Division was ordered to counterattack the American bridgehead from the west, the Germans were never able to concentrate in the Merderet area. The parachute drops in their midst caused heavy losses and disorganization, including the death of the division commander, General Falley, and effectively stifled the planned attacks.11

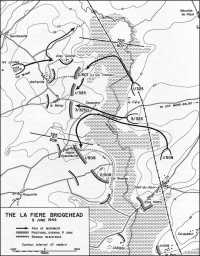

Even against relatively small enemy forces, the problem of seizing a bridgehead over the Merderet remained difficult. At the end of 7 June, there were at la Fière some 600 men of the 507th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments, together with some tanks and artillery and the 1st Battalion of the 325th Glider Infantry which had moved up with the 8th Infantry after landing by sea. West of the river were three organized but isolated groups, ranging from company to battalion size. After the failure of the attempt to establish a bridgehead at la Fière on D Day, the 82nd Airborne Division had been under violent counterattack. While elements of the division held the bridge, other units cleared the east bank of the river and established firm contact with American forces to the north and south.12

Late on 8 June two men from Colonel Timmes’ force west of the Merderet discovered a submerged but passable road across the swamps north of la Fière, crossed without incident, and reported to division headquarters. The discovery opened up a promising route to reach Colonel Timmes’ and Col. George V. Millett’s groups, isolated on the west bank, and then attack south in force to clear the enemy defending the la Fière causeway. The plan was for the 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry (Maj. Teddy H. Sanford), to cross the swamp road after dark while Colonel Millett’s force near Amfreville thrust southeast to join with Colonel Timmes. Sanford’s battalion negotiated the crossing successfully and made contact with Timmes. (Map 6) But in the meantime Millett’s attack failed as his column, fired on in the dark, fell apart. Millett and some of his men were captured; the remainder withdrew northeast toward the river and took no further part in the fighting until 10 June. Lacking

Map 6: The La Fière Bridgehead

Millett’s support, Sanford organized his men and headed for the western end of the causeway. They had not gone far when the enemy opened heavy fire. The Americans were thrown back with severe losses to Colonel Timmes’ position along the river east of Amfreville.

When Colonel Lewis, commander of the 325th Glider Infantry, reported the failure of the attack, General Ridgway, the division commander, decided to renew the attempt to force the causeway at la Fière. The mission was given to the 3rd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry, which was to move up under cover of smoke from positions at Chef-du-Pont. A fifteen-minute artillery and tank fire preparation was arranged and a reinforced company of the 507th Parachute Infantry was to follow up the causeway attack if it faltered. General Gavin, the assistant division commander, was directed to coordinate the attack.

Although the smoke screen proved too thin and the troops of the 325th Glider Infantry came under enemy machine gun fire before they reached the line of departure, the men were able to creep up along a stone wall to the jump-off point. At 1045 the attack was signaled and the men left their shelter under orders to sprint the 500 yards across the exposed causeway. Everything depended on the first dash. But it proved too much for most of the men. Under mortar and artillery fire, all but a handful yielded to the overpowering instinct to seek shelter, and though there was no shelter they threw themselves down along the roadside. Some were casualties, and later arrivals, seeing them, lost the spirit needed to carry them across. The causeway became congested with the dead, the wounded, and the disheartened. Congestion which threatened to abort the attack was made worse by a tank that got out on the causeway and hit an uncleared American mine field. An enemy tank destroyed in earlier action already blocked the road in part. The double constriction increased the difficulty of crossing and added to the casualties. Despite all this, men encouraged by Generals Ridgway and Gavin and Colonel Lewis did succeed in reaching the opposite bank and parts of two companies were able to proceed with their missions. Company E cleared Cauquigny with comparative ease as the Germans under heavy fire from the east bank were disposed to surrender.13 Company G, deploying southward, made slower progress. The delayed crossings meant that when the support company, Company F, crossed under orders to mop up the bridgehead it found no bridgehead. On the initiative of the commander, therefore, it attacked west along the main road.

In the meantime, General Gavin, lacking reports of progress in pushing out the bridgehead from the west bank and worried about the increasing congestion of the causeway, committed the company of the 507th under Capt. R. D. Rae with orders to sweep the causeway stragglers across with him. A part of Captain Rae’s company pushed westward with Company F and entered le Motey. Another part broke off to the south to seek contact with Company G. At the same time a platoon of Company E in Cauquigny was sent north to join the 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry, held up near Amfreville. This platoon was pulled back

La Fière Causeway. Merderet River is in foreground.

later when a patrol reached Major Sanford’s position and discovered that enemy pressure had so far eased that Sanford was actually freed to move as he wished. While the north flank of the new bridgehead was thus secured, fighting continued in the center and on the south, complicated by confused small unit maneuvers extremely difficult to control among the hedgerows.

The gravest threat to the new bridgehead developed during the day at le Motey. Le Motey, sited on a slight rise, afforded ideal ground for defense of the la Fière causeway. By the same token, its commanding position and the cover of its buildings provided a good assembly point for German forces to form for a counterattack. It was the intention of Company F and the company of the 507th to clean out and secure the village.

While they were proceeding to this task, however, General Gavin on the east bank of the river, unaware that the American push had already carried into le Motey and fearing a German assembly there, ordered the supporting artillery to pull back its fire and hold it on the village. One or two shells fell on American troops. Few casualties were suffered but commanders on the spot tried in vain to get word back to have the fire lifted. Company F was therefore forced to withdraw to poorer defense positions on the lower ground. In its new position the company found both its flanks open, and the commander therefore requested that Company E move up on his left.

That move was accomplished, but only after a considerable delay during which Company F, apprehensive of being surrounded, again withdrew a few fields to the east. When Company E moved up, it in effect exchanged positions with F, neither group having observed the other’s move. Company E, coming into line where it expected to find American troops, was greeted only by enemy fire from the flanks. With a sense of isolation and under the impression of being counterattacked, it pulled out in disorder.

The retreat was checked by officers on the west bank of the river before it acquired the momentum of a general panic, and fortunately the enemy made no move. The bridgehead was saved and the line was redressed. The four companies that had crossed from la Fière were securely tied in on the north with the 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry, plus Colonel Timmes’ force. On the south, contact was made with the 2nd Battalion, 508th Parachute Infantry, under command of Colonel Shanley.

For Shanley the la Fière bridgehead served as a long-overdue relief. He had fought for three days in a virtual state of siege on Hill 30. Although he had a relatively large force occupying strategic ground that might have provided a basis for developing a bridgehead at Chef-du-Pont, he attracted such heavy enemy pressure that he had to fight hard and ingeniously just to maintain his position. As far as the command on the east bank of the river was concerned, Shanley’s men were isolated and apparently the only thought was to rescue them. One such attempt made on 9 June failed. Not until the bridgehead was established at la Fière and tied in with Hill 30 did Shanley’s real contribution to the division’s battle become clear. In denying to the enemy control of the west bank of the Merderet and in absorbing a large measure

of the enemy’s striking force which might otherwise have been pointed more sharply at la Fière, he had done much to assist the ultimate establishment of a bridgehead.14

Late in the afternoon of 8 June the Merderet bridgehead was consolidated as the 1st Battalion, 508th, was moved in between Colonel Shanley and the 325th. With all units west of the Merderet at last brought within a single bridgehead, the crossing was ready for exploitation in the first step of the major corps effort to cut westward across the peninsula.

This mission was given to the 90th Division (Brig. Gen. Jay W. MacKelvie), which had begun landing on D Day, and verbal orders were issued by General Collins on 9 June.15 The 359th Infantry had been attached to the 4th Division to assist the latter in the attack north in accordance with the original operational plan that contemplated committing the entire 90th Division on the 4th Division right for a coordinated advance on Cherbourg. Despite the change in plan, the 359th Infantry was to remain at first with the 4th Division while MacKelvie operated west of the Merderet with his remaining two regiments, the 357th and 358th. The initial divisional objective was the line of the Douve where the river flows south between Terre-de-Beauval and St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. (Map XXII) The northern part of this objective was assigned to the 357th Infantry attacking through the lines of the 82nd Division just west of la Fière. The 358th Infantry would cross at Chef-du-Pont attacking toward Picauville, Pont l’Abbé, and St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. When the 82nd Airborne Division had been relieved by the 90th’s attack, it would first hold the line of the Merderet River and then, following the 90th Division, would take over the security of the VII Corps south flank along the Douve.

The attack of the 90th Division jumping off early in the morning of 10 June went badly from the start. The 357th Infantry (Col. Philip H. Ginder) scarcely advanced beyond the perimeter of the 9 June bridgehead. Just beyond le Motey the regiment ran into strongly entrenched troops of the 1057th Regiment (91st Division). The 2nd Battalion in the lead recoiled under its first experience with heavy enemy fire and was relieved in the afternoon by the 1st Battalion. But the latter, attacking toward Amfreville, made virtually no progress. Since the 325th Glider Infantry had stayed in position after being passed through, the bridgehead, though scarcely enlarged, remained secure. Ginder lost ninety-nine men in the action.

On the left, the 358th Infantry (Col. James V. Thompson) advanced a few hundred yards west of Picauville before meeting serious resistance. It then halted on Thompson’s order and the forward companies dug in. Thompson felt that his position was insecure. Germans still held out in a chateau to the rear which had been bypassed in the advance, and an engineer-infantry detachment ordered to blow the Beuzeville-la Bastille bridge over the Douve had been deterred from its mission by heavy enemy fire from across the river. When the regiment

tried later in the afternoon to resume the attack westward, it was unable to move. Both the 1st and 3rd Battalions dug in on the forward line. The bulk of the 129 casualties of the 1st Battalion, 358th Infantry, during the first day of action appear to have been from mortar and artillery fire.

On 11 June both regiments continued the attack, but nightfall found them still short of the D-Day objective line set for the 82nd Airborne Division by the original plan. The 357th Infantry was still fighting in the vicinity of les Landes, and the 358th had encircled but not captured Pont l’Abbé. Next day the 359th Infantry, released from attachment to the 4th Division, was committed between Ginder and Thompson on a 1,000-yard front and assigned objectives along the Douve in the center of the division zone.

South of the 90th Division zone the 508th Parachute Infantry, reinforced and under command of Brig. Gen. G. P. Howell,16 was ordered to attack across the Douve on 12 June to seize the area between the river and the Prairies Marécageuses and join with the 101st Airborne Division at Baupte. By the same order the 325th Glider Infantry was given the mission of defending the north bank of the Douve westward as the 90th Division advanced.17 After a night crossing of the river at Beuzeville-la Bastille, Howell marched to his objective without a fight worth mentioning and reached Baupte by 0800. What happened was that the 100th Panzer Replacement Battalion, which was holding this sector with a large number of foreign personnel and makeshift equipment, broke at first contact with the Americans and pulled out. The debacle not only opened a new hole in the German lines but resulted in exaggerated reports of the strength of the American penetration. German countermeasures were taken in the belief that American armor had broken through in strength.18 The Kampfgruppe of the 265th Division, which was just arriving, was diverted to hold the Baupte-les Moitiers sector and was ordered reinforced by one battalion of the 1049th Regiment of the 77th Division to be brought down from the Cherbourg Landfront.19

While the 508th Parachute Infantry drove unexpectedly into a hole in the enemy lines, the 90th Division continued its sticky movement through defended hedgerow country. By 13 June it had struggled to its initial objectives roughly on a line from Gourbesville to Pont l’Abbé. The latter town was captured by the 38th Infantry after bombing and artillery concentration had leveled it, leaving, as the regimental commander remarked, only two rabbits alive. Criticizing its own failures in the four-day attack, the 90th Division afterward pointed out that training lessons had not been properly applied, particularly the doctrine of fire and maneuver and the precept of closely following artillery.20 In the hedgerow country the normal difficulties of any division green to combat were greatly intensified. In a country

where each field constituted a separate battlefield and where there was no chance of seeing what was happening on either side control was at times impossible. To the shock of experiencing hostile fire for the first time was added the demoralizing invisibility of an enemy entrenched in natural earthworks and concealed in the thick vegetation that luxuriated on their tops. These conditions were, of course, pretty general throughout the Normandy fighting and each division had to work out a solution. General Eisenhower believed that the 90th Division’s special difficulties were due to the fact that the division had not been “properly brought up.”21 On 13 June General MacKelvie, who had commanded the division since 19 January 1944, was relieved without prejudice and replaced by Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum.22 Two regimental commanders were relieved at the same time.

The division was left in the line, but General Collins decided to reorganize completely his attack scheme. The main attack west was to be taken over on 14 June by the 9th Division (Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy) and the 82nd Airborne Division.23 Detailed verbal orders for the attack were issued by General Collins on 13 June. The 82nd Airborne Division was assigned the southern part of the 90th Division’s original attack zone with an axis of advance along the Pont l’Abbé–St. Sauveur-le Vicomte road; the 9th Division in the northern half of the zone would attack toward Ste. Colombe. The 90th Division, when passed through, would wheel north to take objectives along a line from le Ham to Terre-de-Beauval covering the north flank of the westward drive. On General Collins’ request, General Bradley assigned the 79th Division to VII Corps as a replacement for the 90th, but as it turned out the 79th was not used in the attack.

Attack on 14 June began in the south where the 358th Infantry advanced 1,000 yards west of Pont l’Abbé. General Ridgway committed his regiments about noon, the 325th Glider Infantry and the 507th Parachute Infantry abreast, left and right of the highway respectively. Despite an evening counterattack which forced back the right flank of the 507th, the division by night had pushed forward about a mile. While the 358th Infantry was relieved, the 39th began a pivot northward toward its new objectives, opening a gap in the lines near Gottot. Here the 9th Division’s 60th Infantry (Col. Frederick J. de Rohan) was committed, attacking through the narrow zone in column of battalions. Under enemy mortar and artillery fire, the lead companies advanced slowly to reach the Valognes-Pont l’Abbé highway by dark.

Virtual paralysis of the 90th Division, however, continued and the 359th and 357th Infantry Regiments made little progress. Two full days of fighting were required for the 357th to take Gourbesville, while the 359th inched forward and a battalion of the 358th committed on 15 June on the division right flank achieved little.

Whatever may be the full explanation of the 90th Division’s continued slow progress, there is no question that the German defense on the north and northwest was substantially stronger than on the west. While Landrum faced elements of the recently arrived 77th Division, opposition to the drive due west was still only the 91st Division, now beaten down to a battle-weary Kampfgruppe. The bringing up of the Kampfgruppe of the 265th Division did not reinforce the 91st, since the bulk of the new unit was committed in the Pretot area south of the Douve where the Germans thought a large-scale break-through threatened. General der Artillerie Wilhelm Fahrmbacher, who replaced Marcks as commander of LXXXIV Corps after the latter’s death in an air attack on 12 June, reported to Seventh Army on 14 June that a large-scale American attack westward could not be held because of the splitting and mixing of units, the fatigue of the troops, and the lack of sufficient ammunition.24

He was right. On 15 June the 82nd Airborne Division accelerated its advance against decreasing opposition. The 325th Glider Infantry got within 1,000 yards of St. Sauveur-le Vicomte while the 505th Parachute Infantry, after relieving the 507th, established its night line just south of Reigneville. The 60th Infantry on the other hand was hit shortly after the jump-off by a strong counterattack supported by tanks which drove it back to its line of departure. Fighting through the remainder of the day succeeded in recovering only about half the lost ground. Resistance here turned out to be the enemy’s last stand east of the Douve.

Colonel de Rohan’s direction of attack had been shifted slightly to point more nearly due west, increasing the divergence between his advance and that of the 359th on the right. This permitted another regiment to be committed between them. The 47th Infantry (Col. George W. Smythe) was brought in to attack shortly after noon for the high ground west of Orglandes. Colonel Smythe’s advance was rapid, though he was bothered by the exposure of his north flank which was harassed by enemy fire from the vicinity of Orglandes. Despite this the regiment reached its objective by dark.

In planning the continuation of the attack on 16 June, General Collins decided to drive to the Douve with his southernmost regiment (the 325th) regardless of whether commensurate advances could be made on the rest of the front. The whole attack would thus be echeloned to the right rear, as each regiment refused its right to tie in with the regiment to the north of it. Speed in reaching the Douve seemed essential in order to forestall enemy reinforcement. Although the only enemy opposition consisted

Tank entering St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. Company A of the 746th Tank Battalion supported the 325th Glider Infantry in the advance on St. Sauveur.

of small groups fighting delaying action, it seemed possible that, given time, the Germans might be able to organize a coordinated defense along the Douve. The main effort of the corps, General Collins announced on 15 June, would now be to cut the peninsula. To give more weight and cohesion to the attack the 39th Infantry was returned to the 9th Division, and in addition the 39th Infantry was attached, with the result that the division resumed the attack with four regiments in line. The 90th Division committed only the 358th Infantry in its zone. The 82nd Airborne Division employed the 325th Glider Infantry and the 505th Parachute Infantry in the attack while the 507th relieved the 508th in the Baupte sector and the latter regiment passed to reserve in the vicinity of Pont l’Abbé.

The attack of the 82nd Airborne Division again made rapid progress on 16 June, and before noon both the 325th Glider Infantry and 505th Parachute Infantry had reached the line of the Douve opposite St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. They were joined here by the 508th, released from reserve. General Ridgway, observing the enemy withdrawing from St. Sauveur, asked and received corps permission to continue his advance. The city was occupied easily as artillery interdicted the escape routes north, south, and west. The 505th and 508th together established a bridgehead 2,000 to 3,000 yards in depth.

Actually the Germans had been pulling out through St. Sauveur all during the night and it looked as though they were in general retreat. General Collins therefore decided to accelerate his attack. Before noon he called General Eddy of the 9th Division and directed that, instead of stopping at the limited objectives (Reigneville, Hautteville-Bocage, Orglandes) assigned in the original order, Eddy should push his leading regiments, the 47th and 60th, all the way to the Douve line, while the 39th swung around to protect the north flank. Eddy ordered Colonel de Rohan to advance the whole 60th Infantry to the river. Colonel Smythe was assigned objectives for the 47th Infantry on the high ground just east of Ste. Colombe. Smythe had a hard fight in the area of Hautteville-Bocage and Biniville on the last high ground east of the Douve, but pushed on to the main highway west of Biniville.

While this advance was going on, the 2nd Battalion of the 60th Infantry under Lt. Col. Michael B. Kauffman, with the support of a company of tanks of the 746th Tank Battalion, made a cross-country sweep, avoiding enemy contact except for a brush with some machine gunners, and entered Ste. Colombe. Scarcely pausing there, Kauffman’s lead company began crossing the river without any preparatory fire. The Douve at this point splits into three small streams and the road traversing the river flat runs for almost 1,000 yards between Ste. Colombe and Néhou on the west bank. Both towns are built on the hills rising from the river valley, but the slopes are gradual and observation restricted by the ubiquitous hedgerows. With tanks in the vanguard, the crossing of the first two bridges proceeded uneventfully. But the third bridge was out and the tanks turned back. Enemy artillery fire began to range in on all three rifle companies. Company E reached the west bank and dug in before Néhou, under increasing enemy artillery and direct

Ste. Colombe–Néhou area. Circles indicate position of bridges.

large-caliber fire. The other two companies, disorganized by enemy fire, either dug in between the bridges or withdrew to Ste. Colombe. Company G was at last moved up to support Company E on the west bank and during the night the 3rd Battalion was brought up to bolster the shaky line.

Hitler Intervenes

By the end of 16 June, the 9th and 82nd Divisions together had broken the last enemy defenses east of the Douve in their zones and had given impetus to what looked like a precipitate German withdrawal that might be followed rapidly to the sea. As a matter of fact the way was open, and the withdrawal was actually the retreat of disorganized remnants; the 91st Division had been smashed beyond repair.

For the Germans, the threatened splitting of their Cotentin forces was serious enough in itself. But the crumbling of the 91st Division was not a unique or merely local failure; it took place against a background of developing crisis in the whole German defense of the west—a crisis that in the view of OKW demanded not tactical doctoring but far-reaching revision of policy.

During the first week of operations there remained a chance that German armor in the beachhead might be able to seize the initiative at least locally and that, by so doing, might so far check the Allies as to allow the Germans to restore a balance of forces. Whether or not that was ever a real chance, by the end of the week it was becoming increasingly illusory. On 12 June General Marcks, the LXXXIV Corps commander, who was respected throughout the German west army as an inspired leader, was killed. His death coincided roughly with the loss of Carentan, the capture of the Quinéville ridge, which strained von Schlieben’s Montebourg line to the breaking point, another postponement of offensive action against Caen by the I SS Panzer Corps, and a discouraging survey by Seventh Army of the resources remaining in Brittany to reinforce the Normandy front. This survey turned up only a handful of mobile battalions suitable for transport to the battle area.25 In Normandy Seventh Army had no closed front, no prepared positions behind the front, and no possibility of even making up the losses in front-line units, much less of building up a striking reserve.

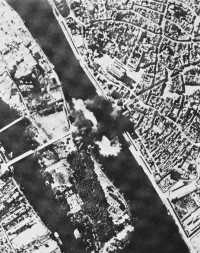

Still worse was the situation in the rear areas, where Allied air power assisted by saboteurs of the French Resistance had so effectively sealed off the battlefields that supplies and replacements could not hope to keep up with the need. Before 6 June Leigh-Mallory’s tactical air forces had knocked out all the bridges across the Seine River between Mantes-Gassicourt and the sea. (See Map V. ) Between 6 and 15 June at least eight bridges over the Loire were destroyed and all were severely damaged.26 The Seventh Army quartermaster noted on 13 June that rail traffic since the invasion had been 90 percent paralyzed. No transport at all had come into the army area from the east.27 One bridge over the Loire at Tours had been repaired on 17 June to the extent

Seine River Bridge at Mantes-Gassicourt under bombardment by aircraft of Ninth Air Force.

that it was possible to push cars across it, although it could not support the weight of a locomotive. An officer from army headquarters was assigned to make sure that five trains a day were moved across.28

Interdiction at the river lines was reinforced by air attacks on the rail centers of the Région Ouest and by continual strafing attacks which made the Germans refrain from risking rail movements that would otherwise have been possible. For example, although some rail lines remained passable between Paris and Orléans traffic along them was negligible. In the week ending mid-June only four trains came through; in the three succeeding weeks, none at all.29 Within the Seventh Army area, the routes between Normandy and Brittany had been mostly destroyed by bombing and sabotage. Engineers worked night and day repairing the lines, but they could not keep up with the rate of destruction. Finally, even on the undestroyed routes, few undamaged locomotives could be found to move the trains.30

The total effect of constant air attacks, dispersed over main and secondary lines and small wayside stations, was much greater than the reduction in rail capacity statistically computed. In the first place, because losses of equipment and personnel through line attacks became insupportable in view of already grave shortages, the Germans were forced to ban nearly all daylight movements, thus cutting two-thirds of their capacity. In addition, cumulative disorganization caused by the unpredictability of rail movements resulted in an increasing paralysis that made impossible even traffic which was not physically blocked. Finally, once the rate of attack outstripped the rate of repair, attacks causing only minor damage had the same effect as destruction of large portions of the rail system.

Examples of the effect of interdiction on troop movement have already been noted. The effect on supply was at least as serious. During the first ten days of the battle Seventh Army received from OB WEST supply depots a little over one million gallons of gasoline against estimated requirements of almost four million. To make up part of the deficit, about a third of the 900,000 gallons in army stock piles was consumed. In the same period ammunition requirements were 6,700 metric tons.31 Against actual consumption of about 5,000 tons, deliveries amounted only to 3,000, leaving again a deficit to be made up out of local reserves. Against ten days’ ration requirements of 5,250 tons, only 200 tons were delivered.32

By the middle of June, rail supply had become impracticable. For supply by road Seventh Army was allocated 1,300 tons of transport space, of which only about one-quarter was serviceable because of unreliable French drivers and the disrepair of the vehicles.33 With this truckage Seventh Army needed to bring up daily 3,200 tons

of ammunition, gasoline, and rations for a defensive action or 4,500 tons for attack. Although the army had substantial stores of ammunition on hand, most of it was captured material and most of it was in Brittany. Dollmann estimated a minimum need for 3,000 more tons of transport space and a daily arrival of eight to nine trains carrying gas, ammunition, rations, and vehicles and equipment.34 He looked with envy at the vehicles with a capacity of 15,000 tons which were being held for the support of Fifteenth Army. But requests for transfer of trucks from Fifteenth Army were rejected by Rundstedt and OKW who, in view of the estimates that large Allied forces still remained in England, held to their belief that the Kanalküste was threatened by a second landing. Allocation of more trucking might have eased the shortages, but it was perfectly clear to General Dollmann that there was only one real solution. He wrote on 11 June that it was absolutely essential that the German Luftwaffe be committed in strength to eliminate the unbearable enemy air superiority.35 Supplies must be able to move by day if the army was to be nourished for offensive action. Armor must be rendered mobile, not only by sufficient deliveries of gasoline, but by protection from direct attack both in the battle zone and on the approach marches. Rail movement of troops and supplies could be resumed only if one line was protected with all available forces, engineers, Flak, and fighter planes.36 Without such air support, the transport situation would certainly get progressively worse. The German Army would continue to have its strength drained away far behind the battle lines.

Hitler’s solution to this dilemma was to exhort the dying man to fight harder. On 12 June Seventh Army received word that every strong point and resistance nest surrounded by the enemy must fight to the last man and the last bullet in order to prepare for the counterattack which would strike through to the coast. Hitler bluntly ordered Seventh Army to wipe out the Allied beachhead between the Vire and Orne Rivers.37 What Dollmann would use to counterattack with was not immediately clear. Hitler had taken one constructive step in canceling a planned attack at Kowel on the Eastern Front so that the II SS Panzer Corps with the 9th SS and the 10th SS Panzer Divisions could be released for employment in the west.38 But the move of these reinforcements would consume many days. Furthermore, it was the opinion of Keitel and Jodl in OKW that the time had passed when the situation could be patched up. Only a bold revision of strategy could hope to meet the crisis.

Keitel and Jodl believed that the situation was very serious. If the Allies once fought their way out of the beachhead and gained freedom of action for mobile warfare, then all of France would be lost. The

best hope of avoiding that defeat, they felt, lay in an unsuccessful Allied landing attempt at some other point. But they questioned whether the Allies would make such an attempt unless they could be compelled to by the long-range rocket bombardment of London soon to begin. If there were no second landing, a chance still remained of isolating the Normandy beachhead. To that end, they thought, German efforts should be directed with all possible means.39 On 13 June Jodl recommended to Hitler that the risks of landings on other fronts now be accepted and the maximum forces moved into the critical fight for France.40

Three days later Hitler sent an order to Rundstedt which conformed in tone to the recommendations of OKW but in substance amounted to no more than another attempt to patch up the front without altering the basic strategy.41 The order told Rundstedt to concentrate his forces, taking the risk of weakening all fronts except that of Fifteenth Army. Specifically, one infantry corps (the LXXXVI) was to be moved up from First Army. The 12th SS Panzer, Panzer Lehr, and 2nd Panzer Divisions were to be relieved by infantry divisions to be transferred from Holland and the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Armies. But the Fifteenth Army in return was to get two new divisions from Norway and Denmark, and the Nineteenth Army’s loss would be made up by transfer of one division from Germany and by naval alarm units. Preparations were to be made for a mass armored counterattack using the three panzer divisions relieved from the line and the four panzer divisions that were on their way to the battle area (the 2nd SS from southern France, the 1st SS from the Netherlands-Belgium border, and the 9th SS and 10th SS from the east).

The plan looked good on paper. Without really weakening any front—the Fifteenth Army would actually be strengthened—seven armored divisions would be freed for offensive action. What the plan failed to take into account was simply the sum of the military realities of the battle developing in Normandy. To discuss the future conduct of operations in more realistic terms, Rundstedt had asked that either Jodl or Warlimont come to France. On 16 June Hitler decided to come himself. Accordingly he flew from Berchtesgaden to Metz and then drove to a spot near Soissons where he met Rundstedt and Rommel on the morning of the 17th. There was an irony in the meeting place. Hitler, the field marshals, and their aides gathered in a concrete bunker that had been designed and built in 1940 at the height of Hitler’s success to serve as his headquarters for the invasion of England. It had never been used until this mid-June meeting called to discuss measures to check the swelling flood of military disasters. The pall of defeat hung over the meeting.

He [Hitler] looked sick and tired out. Nervously he played with his spectacles and with colored pencils which he held between his fingers. He sat bent forward on a high stool while the field marshals remained standing. His old personal magnetism seemed to have gone. After brief and cool

greetings, Hitler, raising his voice, first expressed sharp dissatisfaction with the successful Allied landings, found fault with the local commanders, and then ordered that fortress Cherbourg be held at any cost.42

The field marshals sought in vain to impress Hitler with the need for comprehensive revision of the conduct of operations in the west. What they wanted above all was freedom of action, including permission to draw reserves at will from coastal areas not immediately threatened by invasion. They deplored the dependence on fixed defense of fortified areas and recommended certain withdrawals in order to shorten their lines and mass their forces. They predicted the fall of Cherbourg and asked that future plans be made accordingly.43

To Hitler any proposal to withdraw, whatever its motive, was evidence of defeatism. He made no direct reply but talked instead of how the tide would soon be turned by the V-weapons. The meeting ended without decision, but Rommel and Rundstedt could not have been left in any doubt that Hitler would continue to demand an absolutely rigid defense of every inch of ground. His decision on the Cotentin crisis was characteristic.

On 14 June it had been clear to Rommel that he must reckon with an American break-through at St. Sauveur that might cut the peninsula. He decided accordingly that two divisions (the 709th and the 243rd) were sufficient for the defense of Cherbourg and that the 77th Division should be moved to defend against the Americans’ westward push. Seventh Army issued orders accordingly and provided that, if the peninsula were cut or a break-through threatened in the Valognes sector, the 709th, 243rd, and remnants of the 91st Division should fall back on Cherbourg.44 Against this contingency, LXXXIV Corps divided the Cotentin forces into two groups: Group von Schlieben, to be charged with the defense of Cherbourg and comprising chiefly the troops on the Montebourg line (except the 77th Division); and Group Hellmich, which with the 77th Division and all troops south and west of the Merderet would have the mission of building a defensive line along the Prairies Marécageuses north of la Haye du Puits.45

The 77th Division apparently had trouble disengaging on the north front,46 and no major moves were made on 15 June. On the morning of the 16th General Fahrmbacher of LXXXIV Corps telephoned army that the planned division of forces must be carried out at once. Group Hellmich was already completely cut off from supplies and fought out; it could only hold for a matter of hours. Only two companies of the 91st Division and scattered elements of the 243rd Division remained between the Americans and the west coast. Fifteen minutes after Fahrmbacher had made his report and urgent request for immediate action, Seventh

Army was informed by Army Group B that Hitler had forbidden the planned withdrawal of Group von Schlieben on Cherbourg.47 This meant that it would be impossible to shift the 77th Division from von Schlieben’s right flank, that nothing therefore could be done to prevent the cutting of the peninsula, and that the 77th Division would be sacrificed in a bitter-end fight to hold Cherbourg. The sacrifice furthermore promised to weaken rather than strengthen the defense of Cherbourg. With limited supplies in the fortress and little possibility of bringing in more, an increase in the number of defenders would simply reduce their endurance.

Rommel was at LXXXIV Corps headquarters when the Hitler order reached him late in the afternoon. In an effort to make the best of an impossible situation, Rommel then decided that the 77th Division without giving ground should send weak elements to the south. After Rommel had left the command post, Fahrmbacher called Seventh Army to say that he had decided to shift the whole 77th Division to the vicinity of St. Sauveur. “The Chief of Staff [Pemsel] reminded him of the Führer order and asked whether he had permission of Field Marshal Rommel for this move. ... General Fahrmbacher replied that Rommel had not given his specific approval but that they had talked about these measures only in that sense.”48 Army thereupon forbade the move. The orders earlier given to the 77th Division to disengage and move south were countermanded.49 During the night of 16-17 June command in the Cotentin remained paralyzed, letting slip what was in the judgment of both corps and army commanders their last chance to rescue the 77th Division from the closing trap.

Thus the time for action passed. The following day witnessed only anticlimax. On the morning of 17 June Hitler at Soissons issued a new order. He still did not authorize the 77th Division to pull out to the south. Instead he directed Rommel to defend Cherbourg under all circumstances as long as possible; Schlieben was permitted to withdraw, but only under pressure. This decision ignored the fact that, after the American break-through to the coast, the country to the north would be undefended between Valognes and the west coast, and that Schlieben’s whole position could thus be bypassed. Interpreting rather freely this relaxation of the original stand-fast order, Seventh Army at once ordered the 77th Division to move south to assembly areas near la Haye du Puits.50 In the afternoon through OKW came a second order scarcely more realistic. Schlieben, instead of pulling back into the more or less prepared positions of the Cherbourg Landfront, was now instructed to establish a line between St. Vaast-la Hougue and Vauville which he was to hold to the last.

Both the delay in making these decisions and the unworkable compromise that they entailed resulted in disastrous confusion which sacrificed the bulk of the 77th Division without profit. Still more disastrous for the Germans than the tactical blunder was the principle that underlay it. The crisis of the Seventh Army, strained beyond endurance in its attempt to seal off the Allied beachhead, was to be met by pretending that it did not exist. The renewed determination to hold everything meant that in the end nothing could be held. The principle that withdrawals should be undertaken only after enemy penetrations had made them impossible to organize in orderly fashion meant gaining a few hours for the defense today at the cost of the battle tomorrow. While the Germans were paralyzed in the Cotentin, General Collins on 16 June prepared the final coup to strike to the coast, and at the same time alerted both the 4th and 79th Divisions for the next step—the drive north. The 4th Division was ordered to prepare for attack on Valognes; the 79th Division was to get one regimental combat team ready for movement on four hours’ notice. The intention was to pass the 79th through the 90th Division as soon as the latter had reached its objective line from le Ham to Terre-de-Beauval. (See Map XXII) Concurrently, in anticipation of an early completion of the drive to the west coast, the southern flank was being organized to hold while VII Corps turned north toward Cherbourg. On 15 June VIII Corps (Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton) had become operational with the attachment of the 101st Airborne Division. The mission of VIII Corps was the organization of defensive positions from Carentan west across the peninsula. The 82nd Airborne Division would come under its control and, in preparation for this, was ordered to attack south on 17 June to establish a bridgehead south of Pont l’Abbé about a mile and a half deep. The 9th Division would extend its zone south, attacking with one regiment westward through the St. Sauveur bridgehead. The main effort of the 9th Division on 17 June was to be made by the 60th Infantry, attacking through Néhou to capture Hills 145 and 133 dominating the west coast in the 9th Division zone. The 47th Infantry, attacking from St. Sauveur toward St. Lô-d’Ourville, would protect its left flank. The 39th Infantry would seize and hold the ground between Hautteville-Bocage and Ste. Colombe until the 90th Division reached its objective.

The attack drove ahead so fast against nothing more than straggler units of a completely disorganized enemy that original objectives were changed and battalions of both the 60th and 47th Infantry regiments were pushed up to cut the coastal road at Grande Huanville and Barneville-sur-Mer. Escape routes to the south were effectively blocked when, during the night and the following morning (18 June), elements of the 77th Division attempted to carry out the ordered withdrawal to la Haye du Puits. West of Hill 145 on the morning of 18 June, an enemy column, largely of artillery vehicles, was caught on the road and methodically destroyed by the guns of the 60th Field Artillery Battalion, abetted by infantry and antitank fire. This column and others destroyed near Barneville and north of le Valdecie presumably included much of the 77th Division artillery, which was wholly lost in the attempt to evacuate it

to the south. On the other hand, the 3rd Battalion, 243rd Artillery Regiment, successfully passed through the Americans at Barneville during the night.51 In the meantime a bitter night fight developed around St. Jacques-de-Néhou where the 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, attached as reserve to the 60th Infantry, occupied positions astride a north-south road. Elements of the 77th Division trying to move south attacked here before daylight on 18 June. Riflemen fought at close quarters, without artillery support, for the 60th Field Artillery Battalion was forced to displace by the attack. Mortars at ranges of as little as 20 yards fired some 900 rounds. A limited withdrawal was at length directed and carried out in orderly fashion. After daylight, as enemy pressure let up, the battalion prepared for a counterattack. After a heavy artillery preparation reinforced by 81-mm. mortars which fired their entire basic load, the battalion pushed back to its original positions, taking 60 prisoners and counting about 250 enemy dead. Among the Germans who fell here was the 77th Division commander, Generalmajor Rudolf Stegmann, fatally wounded by a fighter-bomber attack.

The 9th Division lines were not penetrated on 18 June by any substantial enemy force. But the next day, after the 357th Infantry (90th Division) had relieved the 47th Infantry near St. Lô-d’Ourville, a battalion of the 1050th Grenadier Regiment (77th Division) captured a bridge over the Ollande River along with more than a hundred Americans and enabled Oberst Rudolf Bacherer (commanding the 77th Division after the death of General Stegmann) to lead about 1,400 men through to the south.

Relief of the 47th Infantry by the 357th Infantry of the 90th Division was the beginning of the new phase of corps operations. Control of the 90th and of the 82nd Airborne Division passed on 19 June to VIII Corps, charged with responsibility for the security of VII Corps’ south flank. The 9th Division, relieved of defense of the ground it had won in the drive across the peninsula, began to regroup for the attack on Cherbourg in conjunction with the 79th and 4th Divisions.

Advance to the Cherbourg Landfront

Plans for the final drive on Cherbourg were developed during 18 June by General Collins in consultation with General Bradley and some of the division commanders. The original plan to attack with the 4th and 90th Divisions, while the 9th Division blocked the St. Lô-d’Ourville corridor on the west coast, was changed in favor of a stronger attack designed to move fast and take maximum advantage of German disintegration. A fresh division, the 79th, was to replace the 90th, which would take over the 9th Division responsibility for blocking along the west coast. Three divisions, the 9th, 79th, and 4th, would then jump off abreast. (Map XXIII) On the right, the 4th Division was to bypass the coast defenses in order to advance directly on Cherbourg as rapidly as possible. To screen its right flank the 24th Cavalry Squadron was committed. The 4th Cavalry Squadron under 4th Cavalry Group control was also to be put in line to attack between the 9th and 79th Divisions. Thus

VII Corps would commit its full combat strength in the attack.

Through capture by the 9th Division of field orders of the German LXXXIV Corps and the 77th Division, VII Corps had a pretty accurate picture of the state of German defenses in the peninsula. General Collins knew of the splitting of German forces and of the order to General Schlieben to withdraw on the fortress Cherbourg. The last-minute attempt of the 77th Division to pull south of the 9th Division lines had been cut off, and it could be assumed that disorganization existed in the western half of the German lines. By attacking fast and hard VII Corps might exploit the disorganization as well as push General Schlieben’s planned withdrawal into a rout. The VII Corps G-2 estimated that the enemy would fight delaying actions and would stand for a defense of Cherbourg on the line of hills ringing it to a depth of about five miles. Fixed defenses in this position had been reconnoitered and plotted accurately long before D Day. Although the exact number of German troops at General Schlieben’s disposal for the defense of Cherbourg could only be guessed at, it was known that all his major combat units (the 709th, 243rd, 91st and 77th Divisions) existed only in fragments. The total enemy force locked in the peninsula was variously estimated at between twenty-five and forty thousand including Flak and naval personnel and Organization Todt workers.

The estimate of enemy capabilities proved substantially correct. The 9th Division, beginning its attack at 0550, 19 June, found nothing in front of it, and the 60th and 39th Infantry Regiments marched rapidly to their designated objectives between Rauville-la Bigot and St. Germain-le Gaillard before noon. The 4th Cavalry Squadron kept pace until it reached Rocheville. There it was delayed by enemy resistance and at noon the squadron lagged slightly behind the 9th Division.

To keep the 9th Division attack going, it was necessary to protect its right flank. A battalion of the 359th Infantry (90th Division) was brought up to hold the Rocheville area. The 4th Cavalry Squadron was attached to the 9th Division and its zone extended northward. These arrangements completed by the middle of the afternoon, General Eddy ordered resumption of the attack. Still without opposition, the 39th Infantry reached Couville and St. Christophe-du-Foc while the 60th Infantry, bypassing les Pieux, put leading elements into Helleville. The cavalry, delayed briefly by enemy artillery and small arms fire near Rauville-la Bigot, nevertheless kept abreast and entered St. Martin-le Gréard that night. From Rocheville east the corps attack met increasing opposition. The 79th Division (Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche)52 attacked from the line Golleville-Urville, the objective of the 90th Division in its week-long push north from the Merderet bridgehead. The 313th Infantry (Col. Sterling A. Wood) on the left reached its objective, the Bois de la Brique, west of Valognes against only slight resistance. But the 315th Infantry (Col. Porter B. Wiggins), which was supposed to bypass Valognes to

the west and cut the Cherbourg highway northwest of the city, was held up by fire from Urville and a counterattack at Lieusaint. At night it was still southwest of Valognes. General Wyche then decided to leave Wiggins there in position to contain the city, move Wood’s regiment to the right of the division zone, and commit the 314th on its left. The 314th Infantry (Col. Warren A. Robinson) moved out during the night and came up abreast of Wood about dawn.

In all the VII Corps zone, only the 4th Division encountered organized resistance. Since General Barton had held the line from Quinéville to Montebourg Station for four days, the enemy had had ample time to prepare defenses against the anticipated thrust to Cherbourg. Barton ordered the 8th and 12th Infantry Regiments to attack abreast on a northwest axis on either side of Montebourg. The 24th Cavalry Squadron screened the right flank while the 22nd Infantry was held in reserve. Through probing by patrols during the division’s four days in place, it was known that elements of the Seventh Army Sturm Battalion and the 729th Regiment (estimated at 1,000-1,500 men) were dug in generally along the spur railroad that runs from the main Cherbourg line just north of Montebourg. The plan was to strike through this prepared line before daylight, and both regiments jumped off at 0300. Fighting all along the line was similar. None of the forward battalions were able to break the German defenses in the dark although at least one company walked right through the line without being fired on. Where the enemy fought, however, he was in deep entrenchments and difficult to dislodge. Control of the attacking troops was tenuous and some units got lost. It was not until daylight that the attack could start moving with tank support. Then both regiments broke the German line. Schlieben began to withdraw. The 8th Infantry at nightfall was just south and east of Valognes; the 12th Infantry was on its right. The 3rd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry entered Montebourg at 1800 and found it deserted. Later in the evening the 22nd Infantry was concentrated on the division right flank to take part in a three-regiment attack the next day.

The resistance in front of the 4th Division on 19 June was actually little more than a gesture by General Schlieben at carrying out his orders to fight his way slowly back to fortress Cherbourg. The orders could scarcely have been carried out. On his west flank, General Schlieben had no positions to hold and only disorganized troops who would have been needlessly sacrificed if they had attempted a stand. The plunge forward of the 9th and 79th Divisions during 19 June rendered defense of the sector opposite the 4th Division useless and dangerous. During the night, therefore, General Schlieben ordered a general disengagement on this front and drew all his force back to the fortress ring immediately defending Cherbourg. Delaying actions were ordered, but the battle-weary troops did not stop to fight them.53

When the 4th Division resumed the attack on 20 June, it found open country ahead. At first the troops advanced cautiously. They paused to investigate Valognes. The city was choked with rubble but no enemy were in sight. By noon it was clear that the enemy had broken all contact and the regiment took route march formations on the roads and walked north. In this way all arrived by nightfall on their objectives in a line from le Theil to the Bois de Roudou. This line was just in front of the main enemy defenses of Cherbourg, and as the leading companies approached they brushed with enemy outposts and in some cases came under severe hostile artillery fire.

The experience of the 79th Division on 20 June was similar. Both the 313th and 314th Infantry Regiments advanced to the road running roughly east-west between the Bois de Roudou and St. Martin-le Gréard. On that line both met resistance which clearly indicated that they had hit outposts of the Cherbourg defenses. Eloquent of the haste with which the Germans had withdrawn was the capture intact at one point of four light tanks and an 88-mm. gun and at another of eight tanks. The 315th Infantry during the day cleared stragglers from the Valognes area and then moved into reserve positions behind the lead regiments.

The 9th Division, which on 19 June had already come up against the outer veil of the main enemy defenses, had quite a different experience on 20 June. On wings of optimism in the course of the rapid unopposed advance of 19 June, VII Corps had given General Eddy objectives deep inside fortress Cherbourg: Flottemanville-Hague, Octeville, and positions athwart the Cherbourg-Cap de la Hague road.

The plan outlined on the afternoon of the 19th was complicated by the dual mission of the division: to breach the Cherbourg fortress by capture of what were thought to be its two main defenses in the 9th Division zone, Flottemanville and the Bois du Mont du Roc; and to block the Cap de la Hague where it was known the enemy had prepared defenses to which he might fall back for a prolonged last stand. The latter mission was given Colonel de Rohan’s 60th Infantry with orders to drive straight north to seize positions from Hill 170 through Branville to the sea. Colonel Flint with the 39th Infantry would initially contain the enemy to the east while the 47th Infantry followed behind de Rohan as far as Vasteville, then turned east in front of Flint’s positions to attack the Bois du Mont du Roc. Colonel Flint would support this attack with fire, then move on north across the rear of the 47th Infantry to attack Flottemanville.