Chapter 5: The German Counterattack in the XII Corps Sector, 19 September–1 October

Plans for Employment of the Third Army

The Supreme Commander’s decision to make a two-pronged advance in the direction of the Ruhr and the Saar, as set forth in the directive of 4 September,1 had allowed the Third Army to launch its attack across the Moselle River and resume the push toward the Rhine. Logistical support for offensive operations by all the Allied armies was far from assured, however, and the question as to whether the subsidiary drive to the east could be maintained while the main effort was under way in the northeast remained a pressing one.

On 7 September the Combined Chiefs of Staff, representing the military staffs of the United States and Great Britain, requested General Eisenhower to state his intentions for the future conduct of operations on the European continent. The Supreme Commander’s reply followed the line of reasoning advanced in the directive of 4 September but was somewhat less optimistic of quick success and noted that the enemy forces were beginning to stiffen. Eisenhower described the immediate operation as one

to break the Siegfried Line and seize crossings over the Rhine. In doing this the main effort will be on the left. Then we will prepare logistically and otherwise for a deep thrust into Germany. ... Once we have the Ruhr and the Saar, we have a strangle hold on two of Germany’s main industrial areas, and will have largely destroyed her capacity to wage war whatever course events may take. During the advance to the Ruhr and the Saar we will be opening the deep water ports of Havre and Antwerp or Rotterdam which are essential to sustain a power thrust deep into Germany. I wish to retain freedom of action to strike in any direction so far as the logistical situation permits. At the moment and until we have developed the Channel ports and the rail lines therefrom, our supply

situation is stretched to the breaking point, and from this standpoint the advance across the Siegfried Line involves a gamble which I am prepared to take in order to take full advantage of the present disorganized state of the German armies in the West.2

The Combined Chiefs of Staff hastened to put their seal of approval on the “proposals” advanced by Eisenhower and further strengthened his hand by a cable from Quebec which called attention:–

a. “To the advantages of the Northern line of approach into Germany, as opposed to the Southern. They note with satisfaction that you appear to be of the same mind.

b. “To the necessity for opening the Northwest ports, and particularly Antwerp and Rotterdam, before the bad weather sets in.”3

All of these plans for the future obviously turned on a marked improvement in the logistical situation. By the second week of September supplies again were moving rapidly to the front from the Normandy beaches and the Channel ports; but this supply line was overextended, difficult to maintain, and, at the receiving end, subject to the caprices of the oncoming autumn weather. The stubborn German hold on Brest had prevented the use of that deep-water port, and in any case Brest was now too far removed from the main battle front. Supply over the beaches probably would be ended by the November storms. The great harbor at Rotterdam was off the axis of advance and undoubtedly would require enormous efforts to capture and rehabilitate. There remained the deep-water port at Antwerp. The city itself had been taken by Montgomery’s forces on 4 September, but the enemy still held the islands and the Schelde mouths which barred ingress from the sea. Only a major Allied attack could hope to jar the Germans loose from this strangling position and open the much-needed port.

Although the supply lines from the beaches and coastal harbors would provide a daily average of 3,500 tons each to the First and Third Armies during the period of 16–22 September, this was not enough. Both of the American armies desired a daily supply tonnage double this figure; and the 12th Army Group, utilizing the logistical experiences since D Day, had arrived at the conclusion that in days of attack each division (plus its supporting corps and army troops) would require a minimum supply of 600 tons.4 The

port of Antwerp, however, might be expected to meet the requirements of the field armies. The main supply center of the Third Army, Nancy, was 461 miles by rail from Cherbourg—but only 250 miles from Antwerp. The Cherbourg supply route, utilizing both rail and highway facilities, could provide adequate maintenance for only 21 divisions; the port of Antwerp, it was estimated, could support 54 divisions by rail alone.5

On 9, 10, and 11 September, General Eisenhower conferred with Bradley, Montgomery, and Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay (Commander of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force), following these meetings with a directive on 13 September which amplified that of the 4th:–

... the object we must now attain, one which has been foreseen as essential from the very inception of the OVERLORD plan, is the gaining of deep water ports to support major forces in the invasion of Germany. Inevitably the process of cleaning up the rear will involve some temporary slackening of our efforts toward the front. Nevertheless, without improved communications a speedy and prolonged advance by forces adequate in strength, depending on bulk oil, transport and ammunition is not a feasible operation. ... The general plan, already explained, is to push our forces forward to the Rhine, securing bridgeheads over the river, seize the Ruhr and concentrate our forces in preparation for a final nonstop drive into Germany. While this is going on we must ... secure the approaches to Antwerp or Rotterdam so that one of these ports and the lines of communication radiating therefrom can give adequate maintenance to the Northern Group of armies deep into the heart of Germany.6

The directive of 13 September restated in unambiguous terms that operations on the Allied left would “take priority in all forms of logistical support. ...” The Third Army would be permitted to push only far enough “to hold adequate bridgeheads beyond the Moselle and thus create a constant threat to the German forces and prevent the enemy from reinforcing further north by tearing troops away from the Metz area.” Once Montgomery’s forces and the First Army had succeeded in seizing bridgeheads across the Rhine the Third Army would be given the green light for an advance through the Saar and over the Rhine. However, “if, at an earlier date, maintenance of the Third U.S. Army becomes possible, this advance will be initiated at that time.” In this clause of the directive lay the permission General Bradley would need to continue the Third Army attack beyond the establishment of a firm bridgehead east of the Moselle.

On 10 September General Bradley had instructed General Hodges to continue the First Army advance and secure crossing sites on the Rhine in the vicinity of Koblenz, Bonn, and Cologne, meanwhile providing cover for the right flank of the 21st Army Group. At the same time Bradley ordered the Third Army commander to continue the eastward advance with the object of making Rhine crossings in the neighborhood of Mannheim and Mainz.7 Marshal Montgomery was quick to protest Bradley’s directive as being contradictory to the strategy agreed upon for a main effort in the northeast, but Gen. Walter B. Smith, the SHAEF chief of staff, assured the field marshal that the weight of the 12th Army Group attack would be thrown on the left in support of the 21st Army Group drive toward Antwerp and the Ruhr, exactly as General Eisenhower had ordered.8

Actually the scheme of maneuver now taking form would cause General Bradley to re-examine his planned employment of the Third Army. The 21st Army Group was in process of shifting the axis of its attack from the northeast to due north.9 The Ruhr remained the “real objective” but the execution of the new attack would be more intricate than that involved in a direct thrust northeast. Montgomery’s plan called for the Second British Army to drive north and then eastward, thus circling around the northern face of the Ruhr. The initial penetration would depend upon an airborne operation (MARKET-GARDEN) carried forward by three Allied airborne divisions. D Day for the airborne attack was set for 17 September; its object was to secure the crossings over the Rhine and Meuse Rivers in the Arnhem–Nijmegen–Grave sector. Meanwhile the First Canadian Army would be committed in the west to clear the Germans from the seaward approaches to Antwerp. This turning movement north of the Ruhr would leave a considerable gap between Montgomery’s forces and Hodges’ First Army, as the latter pushed toward the southern face of the Ruhr. As a result Bradley was forced to employ one corps from the First Army to cover the gap; this move in turn required a general realignment from south to north on the First Army front and left the Luxembourg area, adjacent to the Third Army, only lightly held.

On the morning of 12 September the 12th Army Group commander met with General Hodges, General Patton, and officers from the headquarters of

ETOUSA (European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army) and the Advance Section of the Communications Zone. Hodges reported that the First Army had enough gasoline on hand to carry it to the Rhine, plus sufficient ammunition for five days of combat. Patton also had sufficient gasoline to reach the Rhine, plus a four-day supply of ammunition. Since the supply status in both armies showed signs of improvement and since both were committed, General Bradley agreed that the two armies should continue the general advance, the main effort, of course, being made by the First Army. Bradley attached a string to the Third Army and told Patton that if he was unable to cross the Moselle with the mass of his forces by the evening of 14 September the attack in this sector would have to be discontinued. If this happened Patton was to assume the defensive on his right wing and in the sector between Nancy and Luxembourg. The Third Army would not have to abandon all offensive operations, however, but would shift the axis of attack north of the Moselle gorge in close conjunction with the drive by First Army’s V Corps.

Patton agreed that this alternative operation was sound, but he did not anticipate that it would be necessary. He reasoned that the German forces opposing the Third Army along the Moselle had no reserves or defenses in depth and that once a break-through had been made the way would be cleared for a rapid advance to the Rhine. Bradley himself was none too anxious to shift the Third Army to the north. The valley of the lower Moselle was tortuous in the extreme and far less favorable than the terrain on the Metz–Frankfurt axis. Some force would have to be left to hold the sector between the First and Seventh Armies. In addition, positions would have to be secured for feeding in the Ninth Army divisions which ultimately would be moved east from Brittany.10 Even Montgomery was anxious for some continued activity in the existing Third Army zone, albeit limited in scope, and suggested that a deception plan be initiated with the object of making the Germans reinforce the Metz and Nancy sectors, at the expense of their northern front, during the period 14–26 September.11

On the morning of 14 September General Bradley was able to tell General Eisenhower: “The situation in front of Patton looks very hopeful [and] he has definitely crossed the river in strength. ...” The next forty-eight hours, Bradley believed, would tell the story as to how fast the Third Army could

go in the advance northeast from the Metz–Nancy base of operations, and whether or not Patton’s progress would justify a continuation of the attack on the existing axis.12 During the day the 12th Army Group commander visited the Third Army headquarters and there approved a plan set forth by Patton which called for a narrowing of the three corps’ fronts in order to allow a power drive in column of divisions by each corps. The proposed shift still would bring the Third Army to the Rhine on the Frankfurt axis, but with a less extended zone of attack and a southern boundary running through Mannheim instead of Karlsruhe.13

Bradley’s intended employment of the Third Army in a continuation of the advance toward the Rhine met with Eisenhower’s approval and on 15 September the latter wrote: “We shall soon, I hope, have achieved the objectives set forth in my last directive [of 4 September] and shall then be in possession of the Ruhr, the Saar and the Frankfurt area.”14 General Eisenhower was optimistic. General Bradley was optimistic. But neither of the two was more optimistic than General Patton, his staff, and his division commanders. The Third Army left and center was across the Moselle. On the right the XV Corps was in the process of closing on the west bank of the river. At various points along the front the enemy continued to offer spirited and stubborn resistance; but the successful drive by the 4th Armored Division had penetrated deep into the German rear and had indicated that the enemy was not prepared to defend in depth once his linear defenses were broken.

Patton assigned objectives to his corps commanders on 16 September.15 He ordered the XX Corps to continue the advance to seize Frankfurt, containing Metz, if necessary, with a small force. The XII Corps was directed to continue the advance “rapidly” to the northeast, take Darmstadt, and establish a bridgehead east of the Rhine. The XV Corps would remain echeloned to the right rear during the general advance but would be prepared, on General Patton’s order, to capture Mannheim or move over the Rhine via bridgeheads belonging to one of the other corps.

Although the Third Army commander’s order for a continuation of the advance applied to all three corps, he expected the XII Corps—in the center—to lead off in the initial deep penetration by a further use of line-plunging

tactics by the armor. The target date for the XII Corps attack was fixed as 18 September. The scheme of maneuver was as follows. The corps would move in column of divisions. The 4th Armored Division, already deep in enemy territory at Arracourt, would lead the column and strike hard to crack the German West Wall between Sarreguemines and Saarbrücken. If Wood’s armor succeeded in punching a hole, Baade’s 35th Infantry Division would follow through, sending one regiment to accompany the armor and using the remainder to hold and widen the gap. McBride’s 80th Infantry Division, heavily engaged in the Dieulouard bridgehead, would remain behind and mop up the enemy in its area; then it would fall into the attacking column, take Saarbrücken and continue on toward the Rhine. The advance combat command of the 6th Armored Division, CCB, already was en route to the XII Corps front and General Patton promised General Eddy that this additional armored weight would be thrown into the attack.16 Patton expected that Bradley would release the 83rd Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. R. C. Macon) from the Brittany area and assign it to the Third Army. If the 83rd arrived in time, Patton intended to use it in the XX Corps sector, sending the 7th Armored Division to reinforce the XII Corps attack. Actually, the Third Army commander had the intention of putting three full armored divisions into the XII Corps drive for a “break-through” to the Rhine. On 17 September he talked to General Grow, complimented him on the 6th Armored successes in Brittany, and ordered the remainder of the division to leave the Montargis sector at once for the XII Corps front.

Such was the ambitious scheme for a rapid advance to the Rhine. In the meantime, however, the enemy was on the march to launch a counterattack which would interrupt the execution of the Third Army plans and effectively contain the XII Corps.

The Dispositions of the Fifth Panzer Army17

In the summer of 1944 the Wehrmacht carried five panzer armies in its order of battle. The first four, by number, were operating on the Eastern and Southern Fronts. Only one, the Fifth Panzer Army, thus far had been committed

in the West. Actually it existed as a continuing organization only in name, and even the name was lost after reverses suffered in Tunisia. During the retreat through northeastern France the Fifth Panzer Army again appeared on the Wehrmacht rolls as successor to Panzergruppe West. But when the situation on the German right wing began to stabilize and the wrecked armored units were withdrawn from the line the Fifth Panzer Army headquarters was relieved from its operational role in Belgium and collected, with a few army troops, in Holland. Having determined to launch a counteroffensive against Patton’s army, Hitler turned to the Fifth Panzer Army and ordered that its staff, and that of the LVIII Panzer Corps (General der Panzertruppen Walter Krueger), be brought to Strasbourg preparatory to assuming control of this operation. When the Fifth Panzer Army headquarters arrived from Holland, on 9 September, it consisted only of an operations staff and some communications troops. However, Hitler personally had selected a chief for the Fifth Panzer Army and two days later General Manteuffel appeared to assume the command, accompanied as was customary by his own chief of staff (Colonel Wolf von Kahlden). General Manteuffel was fresh from the Russian front, where he had last led an armored division. Small, energetic, a popular leader with a reputation for extreme personal bravery, Manteuffel had been named over many his senior to command an army. He was believed to be politically sound—an important consideration for any army commander after the events of 20 July—but his reputation as a prewar armored specialist, enhanced by service in North Africa and Russia, testifies that Manteuffel’s assignment was not merely a political expedient.18

Before Manteuffel could exercise more than nominal command the maneuver space for the Fifth Panzer Army venture had been wiped out, and the 112th Panzer Brigade, designated for employment in the counterattack, had been prematurely committed—with disastrous effect. By 14 September Blaskowitz had no choice but to tell Rundstedt that any assumption of the offensive

by Fifth Panzer Army west of the Moselle and the Vosges was now out of the question. He protected himself, after a fashion, from the imputation that he lacked the “offensive spirit,” by proposing a counterattack on a smaller scale east of the Moselle. (Map II) This operation by the Fifth Panzer Army would be mounted in the St. Dié–Rambervillers–Epinal area, coordinate with the arrival of the 113th Panzer Brigade, which was on its way to Sarrebourg by rail. Thereafter, the maneuver would consist of an initial attack to secure Lunéville as a base, followed by a drive north toward Château-Salins with the intent to cut off the American armor moving east.

At OB WEST Field Marshal Rundstedt refused to take the responsibility for such a radical, though obviously necessary, change in Hitler’s plans (perhaps he had already reached the point where, as he later explained, he could only give orders to the guards on duty in front of his headquarters) and referred Blaskowitz’ request to OKW in Berlin. Twenty-four hours later OKW acceded to the new proposal. The Nineteenth Army was given permission to shorten its lines by a withdrawal on its right flank to a line through Epinal and Remiremont, in order to free the XLVII Panzer Corps for use in the Fifth Panzer Army’s attack. The 11th Panzer Division (Generalleutnant Wend von Wietersheim), licking its wounds near Belfort after the bloody rear guard actions during the Nineteenth Army retreat, should be brought up to strength, re-equipped, and handed over to General Manteuffel so as to give additional weight to the attack. Finally the 107th and 108th Panzer Brigades, whose tanks were still coming off the assembly lines, were ticketed for this new venture, with the provision that they would be given to General Manteuffel only when Hitler’s intuition told him the right moment was at hand. The Fifth Panzer Army requested additional artillery, but Blaskowitz could only say that “as a possibility” one battalion might be taken from the Nineteenth Army. Manteuffel never received his guns, which is not surprising in view of the fact that the Nineteenth Army had lost 1,316 out of its 1,481 artillery pieces during the disastrous retreat from southern France. As a substitute Manteuffel was promised support by the Luftwaffe, after Rundstedt appealed to Hitler, but this promise proved empty indeed.

Some of the units originally designated for the operation already were moving into position. Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division concentrated in the vicinity of Epinal, as infantry replacements came up from Germany. This division was virtually bereft of armor. Rundstedt and the inspector of armor on the Western Front (Generalleutnant Horst Stumpff) had met on 15 September

and agreed that the 21st and Panzer Lehr should receive priority on all available tanks, heavy weapons, and prime movers. Despite this, Feuchtinger would have to fight his division as an understrength infantry formation reinforced by a small tank complement. The 111th Panzer Brigade moved into Rambervillers, after having lost eleven Panthers through air attack and mechanical failures. Both the Panther and Mark IV battalions were present, but the brigade had not received its company of mobile antitank guns. East of Sarrebourg, part of the 113th Panzer Brigade was being reorganized for the march west, after having been scattered by an air attack while still entrained. On 16 September OB WEST gave detailed orders for the counterattack, hopefully enlarging the scheme submitted by Blaskowitz. The attack must begin not later than 18 September, not waiting for the arrival of the 11th Panzer Division. The first objective would be to wipe out the American forces (from the XII Corps) which had just entered Lunéville. With this blocking position in German hands the American bridgehead at Pont-à-Mousson must be erased and the Moselle line restored north of Nancy.

To meet the deadline set by Berlin, Blaskowitz charged Manteuffel with a difficult scheme of maneuver requiring the concentration of his widely scattered forces in the very face of the enemy. This would be carried out as a concentric attack aimed at the 4th Armored Division, with the right wing of the Fifth Panzer Army attacking directly west along the north bank of the Marne-Rhin Canal, while the left wing advanced north to seize Lunéville, cross the canal, and strike into the American flank. The LVIII Panzer Corps, on the right, was assigned the 113th Panzer Brigade and the troops of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division which had been able to make their way down from Metz to the Lunéville area before the American armor cut the roads east of the Moselle. The 113th would move from the Sarrebourg railhead, cross to the north of the canal between Lagarde and Moussey (some fifteen air-line miles east of Lunéville) and strike due west against the American position—now held by CCA, 4th Armored Division. There the terrain between the canal and the Seille provided excellent tank going, with firm ground, gently rolling country—offering tank defilade—and an adequate network of lateral roads leading onto the main, hard-surfaced highway between Nancy and Château-Salins. However, there was little forest cover against air attack and observation.

The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division held a thin line of pickets along the canal north of the Forêt de Parroy. This weak spot in the center of the Fifth Panzer Army

was effectively blocked by blown bridges at the canal and by the density of the forest, which precluded tank operations. According to the plan the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division would make its initial contact with the XLVII Panzer Corps, as it came north, at Chanteheux—hard by Lunéville—and then be picked up by General Krueger as the 113th Panzer Brigade rolled west.

The XLVII Panzer Corps, with the 111th and 112th Panzer Brigades and the 21st Panzer Division, was given the mission of initially holding the left (or west) flank of the Fifth Panzer Army with a minimum force between Rambervillers and Lunéville (some twenty miles), while using its main force to drive north across the canal in company with the left wing of General Krueger’s LVIII Panzer Corps. In this sector the Mortagne and Meurthe Rivers seemed to offer successive defense lines east of the Moselle; Lunéville, in its apex position at the head of a river complex, funneled the main roads leading across the canal. Finally, it was hoped that the Nineteenth Army could free enough troops to extend its right flank and take up the slack north of Rambervillers as the XLVII Panzer Corps moved to the attack.

General Manteuffel protested that the Fifth Panzer Army was not strong enough to attack on such a scale—but received peremptory orders that he would attack on 18 September. Manteuffel and his corps commanders may well have been dubious. General Lüttwitz kept the phone busy with reports that the western flank of the XLVII Panzer Corps, on the Moselle, was “wide open.” The day before the scheduled attack one panzer battalion of the 111th Panzer Brigade and the few remaining tanks of the 112th Panzer Brigade were still engaged against the French armor in the Châtel area, and it was questionable whether the Nineteenth Army could relieve them in any strength. The 21st Panzer Division had just received twenty-four tanks, but was still minus much of its infantry. General Krueger’s LVIII Panzer Corps was widely dispersed, with piecemeal commitment the only possibility. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division (Rodt), whose Reconnaissance Battalion was fighting in Lunéville, still had its rear columns in the First Army zone. The 113th Panzer Brigade had assembled its battalion of Mark IV’s, but was just in process of detraining the Panther battalion.19

The Attack at Lunéville, 18 September

Despite Manteuffel’s misgivings the Fifth Panzer Army moved in the early morning of 18 September to concentrate for the attack as had been planned. Krueger sent the 113th Panzer Brigade, still minus some of its tanks, down the road to Blâmont and at the end of the day the brigade turned toward the canal. Lüttwitz, after one last pessimistic prediction about his exposed western flank, moved northward along the Meurthe River toward Lunéville. This advance was made by seventeen tanks and the armored infantry of the 111th Panzer Brigade, which had not been engaged on the Moselle. Meanwhile the 21st Panzer Division remained echeloned apprehensively to the west of the Meurthe with its troops disposed on both banks of the Mortagne River.

The Germans and Americans were almost equally confused as to the strength and location of the opposing forces in and around Lunéville. On 15 September two troops of the 2nd Cavalry Group (Col. C. H. Reed) had tried to enter Lunéville from the south but had been beaten off by the advance guard of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. Next day the 42nd Cavalry Squadron (Maj. J. H. Pitman) had returned to the attack, while CCR, 4th Armored Division (Col. Wendell Blanchard), circled into the city from the northwest. The Germans fell back from Lunéville to the shelter of the Forêt de Parroy, northeast of the city, but then returned to filter into Lunéville and there engage the FFI and the small American contingent. On the night of 17 September the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had so many men in the city that a German agent sent out a report that the Americans had left. This report was relayed to Lüttwitz, who headed straight for Lunéville without thought of fighting for the town—and apparently with no idea that the 42nd Cavalry Squadron had a line of outposts to the southeast.

Actually, the Americans still had a firm hold on Lunéville but had not taken cognizance of the armored threat now developing from the south. As early as 15 September the cavalry had learned from prisoners that tanks were being unloaded around St. Dié. Colonel Reed reported this information at XII Corps headquarters—with a request for additional antitank support—but was told that intelligence sources indicated that the German armor would be used against the Seventh Army.20

About 0700 on the morning of 18 September the advance guard of the 111th Panzer Brigade hit the 42nd Cavalry outposts manned by A Troop. The six 75-mm. assault guns from E Troop were rushed forward to meet the Panthers, but the American shells bounced off the heavy frontal armor of the German tanks and three of the guns were destroyed in as many minutes. The cavalry fought desperately, but armored cars and machine guns were no match for the Panthers. Dismounted action by small groups of cavalrymen was more effective against the German infantry following the tanks and held the enemy advance guard in check until about 1100. During the fight Major Pitman was killed. Colonel Reed was severely wounded and had to be evacuated.21 The 42nd Squadron executive officer, Captain W. E. Potts, had organized the initial defense and, as the enemy circled in a tightening noose around the squadron, finally led the 42nd through the narrow gap remaining to the north and reached Lunéville. This gallant delaying action had won time for the remainder of the 2nd Cavalry Group to retire through Lunéville and had alerted Blanchard’s small armored force inside the city.

General Blaskowitz intervened about noon and ordered Manteuffel to press the attack and take Lunéville. A combined assault by the 111th Panzer Brigade and 15th Panzer Grenadier Division detachments forced CCR and the cavalry back into the north part of the city. In answer to this threat CCA, across the canal, rushed a task force to the scene while General Eddy detached CCB, 6th Armored Division, which had just closed to support the 35th Division east of Nancy, and started it for Lunéville. The first reinforcements arrived about 1600, including some tank destroyers from the 603rd Tank Destroyer Battalion which distinguished themselves in a fire fight at close quarters; as the American artillery—now comprising two armored field artillery battalions and the 183rd Field Artillery Group laid down an accurate and destructive fire, the enemy fell back behind the railroad tracks in the south quarter of the city. When night came Manteuffel ordered the 111th Panzer Brigade to disengage and move piecemeal to an assembly area at Parroy, north of the canal, for a continuation of the general advance.

Meanwhile, OB WEST had sent additional orders to the Fifth Panzer Army. The direction of the main attack on 19 September now was to be changed from north to northwest, Nancy being substituted for Château-Salins as the initial army objective. This new maneuver aimed at freeing the hard-pressed

553rd VG Division, rapidly being hemmed in by the XII Corps, and at restoring the Moselle line—either by a future attack between Nancy and Charmes or a stroke north toward Pont-à-Mousson. Execution of the plan, however, was jeopardized by the XV Corps advance across the Moselle, which justified all of General Lüttwitz’ fears for the security of his weak left flank. So Manteuffel ordered a general regrouping. The XLVII Panzer Corps was given the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and told to defend on a line from the canal, at Einville, through Lunéville, and thence along the Meurthe River, west of which the 21st Panzer Division and 112th Panzer Brigade already were fighting French and American patrols. The LVIII Panzer Corps, in return, was given the 111th Panzer Brigade to reinforce the 113th Panzer Brigade in the drive for Nancy. At midnight Manteuffel phoned General Krueger and gave him instructions for the attack the following morning—with accompanying threats of condign punishment if his orders were not strictly carried out. By 0600 all of the 113th Panzer Brigade had to be across the canal and in position at Bourdonnay, nine miles east of Arracourt, to start the drive west toward Champenoux, twenty miles away, where the armor would link up with the beleaguered 553rd VG Division. Further, General Krueger had to attack without waiting for the 111th Panzer Brigade to cross the canal and come up on his left flank. This insistence on piecemeal and immediate attack is readily understood in view of the continuing pressure from Berlin, as well as of the marked German inability to pierce the American counter-reconnaissance screen on the ground and in the air, precluding any real knowledge of the 4th Armored Division’s strength and locations. But such piecemeal efforts were ultimately to play into the hands of the 4th Armored Division, standing between the LVIII Panzer Corps and Nancy.

The Arracourt Tank Battle, 19–22 September

On 17 September CCB, 4th Armored Division, had been sent north from the Marne-Rhin Canal to aid the 80th Division. By the end of that day the XII Corps commander had canceled further movement toward the 80th upon receipt of orders from General Patton alerting the corps for an advance northeast toward the Sarre River, to be executed in column of divisions with the 4th Armored Division in the lead. The optimism so prevalent in the Third Army in early September had abated somewhat, at least among the combat elements, and General Wood phoned the corps headquarters to warn that

“this job of getting supplies across the river [the Moselle] and on the roads is getting to be a major problem. This will not be a very fast operation—no blitz.” But at 0030 on 18 September, Wood gave orders for the resumption of the advance on the following day: CCB to move from Delme on Saarbrücken; CCA to move out from the Arracourt area along the center road in the XII Corps zone (Morhange, Puttelange) and by subsidiary roads on the south flank toward Sarreguemines. News of the German attack at Lunéville only partially deranged these plans for neither Eddy nor Patton was greatly concerned. CCA, after having sent a task force to aid CCR, was ordered to stand to until the situation at Lunéville was clearer and the task force had returned; but CCB continued planning for an attack toward Saarbrücken on the following day.22

On the night of 18 September the 4th Armored Division was deployed as follows: CCR had beaten off the Lunéville attack, with slight losses to itself, and was being relieved by the combat command from the 6th Armored Division. CCB was massed near Fresnes-en-Saulnois. The main body of CCA, somewhat reduced by the Lunéville mission, was assembled around Arracourt, about twelve miles to the southeast. (Map XIX) The extended CCA sector, reaching from Chambrey (south of Château-Salins) nearly to the canal, could be only thinly outposted on the night of 18–19 September since Colonel Clarke had a relatively small force at hand: two companies of medium and one of light tanks, a battalion of armored infantry, a battalion of engineers, a company of tank destroyers and three battalions of artillery.23 The armored infantry and a company of medium tanks were deployed on the north flank between Chambrey and Arracourt. The combat command headquarters, the field artillery, and a platoon of tank destroyers were grouped in and around the town of Arracourt, while the bulk of the engineers held the south flank, withdrawn somewhat toward the west. One medium tank company, Company C of the 37th Tank Battalion (Capt. Richard Lamison), formed a combat outpost around the crossroads village of Lezey—between four and five miles northeast of Arracourt.

As yet there was no suspicion of the LVIII Panzer Corps advance from Sarrebourg, and though just before dark artillery observers had counted some

thirty tanks east of Lunéville (the second panzer battalion of the 111th Panzer Brigade had now come up) this threat appeared to be checked by the American reinforcements at Lunéville.

Just before midnight the CCA outposts near Lezey heard tracked vehicles moving in the darkness to their front. They called for artillery fire and the clanking of the treads ceased. About 0730 on 19 September a liaison officer, driving down the road near Bezange-la-Petite, ran into the rear of a German tank column but escaped notice in the thick morning fog and radioed to his battalion commander, Colonel Abrams, who was at Lezey. At about the same time a light tank platoon had a brush with some German tanks in the vicinity of Moncourt.

The 113th Panzer Brigade, with forty-two Panther tanks of the Mark V battalion and the 2113th Panzer Grenadier Regiment in the lead, had moved from Bourdonnay in a successful night march, reorganized its advance guard near Ley, and now pushed through the heavy fog toward Bezange. In the meeting engagement which followed, as in the later tank battles, the morning fog common to this area played no favorites: it protected the German armor from air attack, but permitted the American tanks to fight at close quarters where the longer range of the Panther tank gun had no advantage. A section of M-4 tanks were in an outpost position south of Lezey when the first Panther suddenly loomed out of the fog—hardly seventy-five yards from the two American tanks. The Panther and two of its fellows were destroyed in a matter of seconds, whereupon the remaining German tanks turned hurriedly away to the south. Capt. William A. Dwight, the liaison officer who had reported the enemy armor, arrived at Arracourt and was ordered to take a platoon of the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion to aid the tanks at Lezey. Just west of Bezange-la-Petite Dwight’s platoon saw a number of German tanks moving through the fog. The tank destroyers quickly deployed in a shallow depression and opened fire at about 150 yards. In the short fight that followed, three of the four American tank destroyers were lost, but not until they had destroyed seven enemy tanks.

The 113th Panzer Brigade attack developed in a series of consecutive jabs, generally made by a company of tanks and a platoon of infantry, as the enemy probed to find an opening in the CCA defenses. Meanwhile the American outposts had been drawn in, the company of medium tanks was hurried down from Chambrey, General Eddy sent the task force at Lunéville back to rejoin the command, and the armored artillery ranged in on the

attackers. The superior mobility of the American tanks and self-propelled tank destroyers gave the defenders a decided advantage. When the Panthers turned away, after the abortive attack at Lezey, Captain Lamison took four tanks from C Company and raced the enemy some three thousand yards to a commanding ridge west of Bezange-la-Petite. Arriving on the position about three minutes before eight Panthers appeared, Lamison’s tanks got set and knocked out four of the German tanks before they could return the fire; then they withdrew over the crest of the ridge, moved south a short distance, reappeared, and finished off the remaining Panthers. In the late morning the German attack turned west toward Réchicourt-la-Petite, attempting to drive around the town, first to the north, then to the south. Here again the American artillery, tanks, and tank destroyers inflicted severe losses on the enemy armor. A platoon of tank destroyers from the 704th netted eight Panthers and succeeded in driving the rest of an enemy tank company back in flight.

The company of medium tanks which had been sent to Lunéville returned in the afternoon and Colonel Clarke was ready to counterattack. A combined force from Companies A and B, 37th Tank Battalion, led by Maj. William L. Hunter, wheeled south through Réchicourt, caught the Germans in the flank, and knocked out nine Panthers with the loss of only three tanks. As the day ended, the 37th Tank Battalion turned its attention to mopping up the German infantry west of Moncourt, and finally, guided through the night by burning German tanks, assembled in the vicinity of Lezey.

The German armored attack appeared to have spent itself. General Patton, who had come to Arracourt from the Third Army headquarters at Etain, talked with General Wood and agreed that CCA should begin the push toward Sarreguemines the next morning, reinforced by CCR, which had arrived from Lunéville during the day. On the whole there appeared to be no reason for worrying further about a German threat in the Arracourt sector, since CCA reported that forty-three enemy tanks, mostly factory-new Panthers, had been destroyed,24 and that its own losses had been only six killed and thirteen wounded; three American tank destroyers and five M-4 tanks had been knocked out.

Elsewhere, the Fifth Panzer Army had been no more successful on 19 September. The 111th Panzer Brigade, supposed to be north of the canal that morning, was misdirected along the way by a patriotic French farmer and did not make contact with the 113th Panzer Brigade at Bures until late in the afternoon. The 111th Panzer Brigade did not reach Krueger in full strength. Some of its tanks had not yet come up from the depots, and low-flying American planes had inflicted much damage on the column during the march north. Over to the west the security line set up along the Mortagne by the 21st Panzer Division, and the remnants of the 112th Panzer Brigade, had been pierced at several points by the forward columns of the XV Corps, and during the night of the 19th this defensive line was withdrawn to the east bank of the Meurthe. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, in the north, was trying desperately to set up a blocking position between the Meurthe and the town of Einville, on the canal. With the XLVII Panzer Corps thus heavily engaged General Lüttwitz had to tell his superiors that he had no troops to attack north of the canal.

General Blaskowitz was very dissatisfied with the day’s showing and ordered Manteuffel to continue the LVIII Panzer Corps attack without regard to the losses already suffered or the crippled condition of the 113th Panzer Brigade. Early the following morning the LVIII Panzer Corps made a gesture toward carrying out the army group commander’s orders by sending some tanks from the 111th Panzer Brigade out on patrol; but the rest of the corps remained stationary between Ley and Bures, while General Manteuffel tried hard to persuade Blaskowitz that the attack must be abandoned in its entirety. All he got for his pains was a sharp reprimand for not possessing “the offensive spirit” and further orders insisting that the drive toward Nancy must be continued.

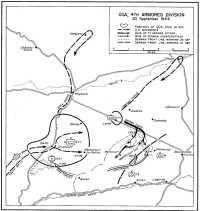

On the morning of 20 September CCA began to move out toward the northeast,25 leaving one company of the 35th Tank Battalion near Arracourt to cover the concentration of the 320th Infantry (-), CCR, and the 602nd Tank Destroyer Battalion, which were moving in to take over the area. (Map 5) To the north CCB, which had initiated the scheduled attack on the previous day, was fighting in a thick blanket of fog to clear a road through Château-Salins, after attempts to bypass on miserable side roads had bogged down. At 1130 the head of one column of CCA had reached Hampont and

Map 5: CCA, 4th Armored Division, 20 September 1944

another was closing on Dieuze when General Wood radioed that enemy tanks had returned to the attack near Arracourt and that a task force must be sent back to the scene at once. Actually, only eight German tanks were involved, having made a sortie toward the 191st Field Artillery Battalion just as it was ready to limber up and join the march column. This attack was readily handled by the 155-mm. howitzers, firing high explosive at one thousand yards, and by the appearance of the rear guard tanks and some tank destroyers,

which allowed none of the attackers to escape. But Colonel Clarke led his whole combat command to turn back and sweep up the entire area “once and for all.”

By midafternoon the sweeping operation was under way. Colonel Abrams assembled a force consisting of three medium tank companies of the 37th and two companies of the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion near Lezey, while the artillery adjusted its supporting fires, and then drove down on Ley. While Abrams had been gathering his people the Germans had moved to parry the coming blow by dispatching a Captain Junghannis and a group of Mark IV tanks and 88-mm. guns from the 111th Panzer Brigade reserve to positions on Hill 260 and Hill 241 west of Ommeray. The main American force went through Ley with hardly a shot fired. But C Company, 37th Tank Battalion, which was covering Colonel Abrams’ flank east of Ley, ran head on into the fire of Junghannis’ tanks and guns. Between Ley and Ommeray rise two low hills with a narrow valley between: Mannecourt on the west and Hill 241, slightly higher, on the east. Company C, coming over Mannecourt Hill, met a fusillade from the Germans on the forward slope of Hill 241. In a fight lasting about three minutes C Company lost five or six tanks—but inflicted about the same number of tank casualties on the enemy. Then the Americans drew back from the crest and waited for Colonel Abrams to come up with B Company. When Abrams arrived the two companies maneuvered into new positions and engaged in a brief tank duel which brought the losses for both sides to some eleven or twelve tanks apiece.26 Darkness was coming on and Colonel Abrams finally turned aside to complete the sweeping operation by a night attack southward, taking Moncourt27 and then bivouacking with his main body back at Lezey. On CCA’s south flank Major Kimsey and a small force had been sent during the afternoon to mop up along the canal. West of Bures five Panthers on patrol were destroyed, but when Kimsey tried to move into Bures the German tanks, fighting from cover, outranged the M-4’s and the Americans had to give up the attack.

Throughout the day CCA had held the initiative, but the additional armored weight given the LVIII Panzer Corps by the 111th Panzer Brigade prevented any clear-cut decision.28 General Blaskowitz, however, was far from satisfied by the events of 20 September and the Army Group G War Diary noted critically that “the Fifth Panzer Army shows a marked tendency to limit itself to defensive action.” Again General Manteuffel was given a lecture on tactics and enjoined to regain his “operational freedom” by returning to the offensive and initiating counterattacks immediately after every American attack. Manteuffel’s plea that the combat value of the two panzer brigades was “very limited” brought no reply from above. When Abrams took Moncourt, later in the evening, Manteuffel seized the opportunity to report that his lines had been broken at Ommeray, some two and a half miles farther east. He asked for permission to withdraw the LVIII Panzer Corps to a new and shorter line between Gélucourt and Lagarde, while redressing his southern flank, across the canal, by a general withdrawal in the XLVII Panzer Corps sector to a position east of the Forêt de Parroy and the Forêt de Mondon. Blaskowitz’ only reply was a short homily on tactics and an order to counterattack.

Manteuffel’s plea for a general withdrawal did not coincide with a new plan of attack which OB WEST had ordered with an eye to closing the gap opening between the First and Fifth Panzer Armies as CCB probed around Château-Salins and CCA pushed toward Morhange and Dieuze. Rundstedt instructed the First Army to gather reserves for an attack southeast from Delme. The Fifth Panzer Army, reinforced by the 11th Panzer Division whose advance elements were just coming up from Sarrebourg, in turn was ordered to strengthen its right wing and attack to the north so as to meet the First Army drive near Moyenvic.

The failure to achieve an early and brilliant victory in the armored counterattack had provided Hitler with an excuse to get rid of Blaskowitz, who, although politically suspect, had not become involved in anti-Nazi intrigues and cabals. On 21 September Hitler relieved General Blaskowitz and gave the command of Army Group G to General der Panzertruppen Hermann

Balck; Colonel Friedrich von Mellenthin replaced Generalleutnant Heinz von Gyldenfeldt as chief of staff.

Balck came from an old military family; his father had written a well-known textbook on tactics which had been translated and used for instruction in the United States. Balck had fought as a young officer through the four years of World War I and subsequently took part in the early mechanization of the Reichswehr. After winning recognition in the Somme campaign of 1940, he spent some months as a staff officer at OKH. Later, in the Russian campaigns, he commanded the famous 11th Panzer Division, led the XLVIII Panzer Corps in the fierce battles around Lemberg, and briefly held the position of commanding general of the Fourth Panzer Army. Both Balck and Mellenthin came to the West with no experience against the Western Allies—a fact which Rundstedt always held against the new appointees. Politically, Balck long had held the reputation of being an ardent Nazi. His personal bravery was well established (he had been wounded six times), he was known to be an optimist, and he had a long record of successful offensive operations. On the other hand Balck already had been ticketed as an officer prone to take too favorable a view of things when the situation failed to warrant optimism. From his earliest days as a junior commander he had built up a reputation for arrogant and ruthless dealings with his subordinates; his first days in command of Army Group G would bring forth a series of orders strengthening the existing regulations on the enactment of the death penalty. He was, in short, the type of commander certain to win Hitler’s confidence.

When Balck took over his new command on 21 September he immediately ordered the First Army to start its drive past Château-Salins, still in German hands, toward Moyenvic, and set 0700 the next morning as H Hour for an attack by the right wing of the LVIII Panzer Corps. This attack aimed at the seizure of the high ground southeast of Juvelize, preparatory to an advance on Moyenvic when the 11th Panzer Division joined Manteuffel.

CCA made another sweep on 21 September, this time south to the canal past Bures and Coincourt, preceded by air raids over the sector and intense artillery fire. To their surprise the Americans met little opposition, except some infantry and a few dug-in tanks, for the LVIII Panzer Corps had refused its southern flank in conformity with the withdrawal by the right and center. Unaware of the impending German attack General Wood ordered the 4th Armored Division to take the next day for rest and maintenance, prior to an attack by both combat commands to clean out Château-Salins

where the garrison thus far had defeated all attempts to take the town and had damaged seven American tanks the previous day. The 9th Tank Destroyer Group and 42nd Cavalry Squadron were brought up to hold the ground between Ley and the canal.

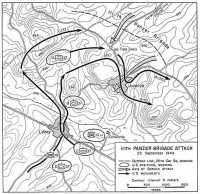

The morning of 22 September was fogbound and murky, giving the German assault force protection from the dreaded Jabo’s.29 But the attack toward Juvelize began nearly three hours late because of the tardy arrival of an infantry battalion which had been sent forward by the 11th Panzer Division to relieve the 111th Panzer Brigade, the latter being intended for use in the subsequent attack against Moyenvic. (Map 6) In the first phase of the assault the blow was taken by the 25th Cavalry Squadron, which was screening CCA’s left flank and observing the roads between Dieuze and Moyenvic. During the previous night German patrols had laid white marking tape up to the cavalry lines and now the advance guard of the main enemy force, circling around to the north of Juvelize, sneaked in on the squadron with tanks and infantry. In some instances the German tanks came within seventy-five yards of the cavalry pickets before they were observed. The thin-skinned cavalry vehicles were no match for the enemy and seven light tanks were lost in the melee. But C Company of the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion, in hull defilade behind the center of the cavalry line, succeeded in destroying three of the German tanks.30 This prompted the rest to turn back to the northeast, leaving the German infantry assault force stranded west of Juvelize.

The sun finally broke through and the XIX TAC flew into the area, strafing and bombing, while Colonel Abrams led the 37th Tank Battalion and the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion in a counterattack to take Juvelize and break up the German advance. Some of his tanks circled to the northwest and seized the hill at les Trois Croix looking down into the valley east of Juvelize along which German reinforcements were moving from the Bois du Sorbier. Fourteen enemy tanks were destroyed here by tank and artillery fire at ranges from 400 to 2,000 yards,31 and Colonel Heinrich Bronsart von Schellendorf, commander of the 111th Panzer Brigade, was mortally

Map 6: 111th Panzer Brigade Attack, 22 September 1944

wounded.32 The P-47’s broke up the remaining attackers, with the help of the armored field artillery, and cut them down as they straggled back to the northeast. Manteuffel’s urgent pleas for help from the Luftwaffe remained unanswered and he reluctantly sent his last armored reserve, a few tanks from the 113th Panzer Brigade, east of Lezey to hold astride the Moyenvic–Bourdonnay road. The German attempt to reach Moyenvic had ended in disaster. Only seven tanks and eighty men were left in the 111th Panzer Brigade

when night fell, and a scheduled continuation of the attack by the 111th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which was marching up from the 11th Panzer Division, was called off as useless.

The tank battles fought from 19 through 22 September had cost CCA fourteen medium tanks and seven light tanks, totally destroyed, and a casualty list of 25 killed and 88 wounded. The German losses cannot be accurately determined, but two panzer brigades had been wrecked as combat units—without bringing the Fifth Panzer Army appreciably closer to the Moselle or the 553rd VG Division.

The XV Corps Advance to La Vezouse River, 21–24 September

The failure of the Fifth Panzer Army attack north of the Marne-Rhin Canal had a counterpart in the reverses suffered by the XLVII Panzer Corps south of the canal. General Lüttwitz’ security line hardly had been established along the lower Meurthe, after the withdrawal from the Mortagne, before the pursuing XV Corps attacked the new river position. The boundary changes between the XV and XII Corps gave General Haislip an opportunity to flank the Meurthe line by a turning movement through Lunéville, where the Meurthe bridges were held open by the XII Corps armor. (Map XVIII) The 313th Infantry, charged with executing this maneuver, detached one battalion at Lunéville, to aid the armor in the street-to-street battle for possession of the city, and the remainder of the regiment turned southeast to attack along the enemy bank of the Meurthe.

On 21 September the 313th (-) hit the outposts of Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division at the village of Moncel, just outside of the Forêt de Mondon. Moncel was taken. But when the 313th reached the forest it was brought sharply to a halt by heavy fire from the main German position—a line of foxholes and trenches masked by the woods. General Wyche, the 79th Division commander, had planned a coordinated attack against the Forêt de Mondon on 21 September as a necessary prelude to an advance on the Forêt de Parroy. While the 313th probed the German positions on the north edge of the forest, therefore, the 3rd Battalion of the 314th began a bitter fight to cross the Meurthe River and penetrate the forest from the west. Three companies succeeded in crossing the river near St. Clément, but were met by a hot fire when they moved forward onto the flat, bare plain which here extends some two thousand yards back to the forest. This narrow bridgehead,

on the very edge of the Meurthe, could not be maintained and when night came the battalion fell back across the river.

On 22 September General Lüttwitz attempted to ease the growing pressure on his north flank by local counterattacks around Lunéville. At Moncel three enemy tanks and a small party of infantry broke through the lines of the 313th Infantry and reached the northwest quarter of the town, where they were surrounded and killed or captured. Lunéville continued to be a sore spot for the Americans since it lay adjacent to the Forêt de Parroy, from whose recesses the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division launched new forays on the city at will. Two battalions of the 315th, which had just been brought up from reserve to take over the city, were hit during the day by an attack that reached the stadium in the northeastern suburbs, but the enemy was again driven out.

The 79th Division continued its drive to dislodge the 21st Panzer Division and the few remaining tanks of the 112th Panzer Brigade from the Forêt de Mondon, but with little immediate success. Here, as elsewhere in Lorraine, the veteran German proved himself a skillful and tenacious forest fighter. At the northern edge of the woods, although the 313th Infantry inflicted heavy punishment on the German grenadiers, it could make no real headway. The 314th forded four companies across the Meurthe but found it impossible to move forward any heavy weapons without a bridge; nor could the infantry attack the German positions in the woods without close-up artillery and tank support. The drive halted until dark, when a bridge could be built.

The progress of the 79th Division had been slow on 22 September, but the situation of the opposing XLVII Panzer Corps was growing more precarious by the hour. On the north flank the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, still minus one of its regiments, was straining to hold between Lunéville and the canal as a cover for the left flank of the battered LVIII Panzer Corps. The 21st Panzer Division, now hardly at regimental strength, held a line along the east bank of the Meurthe that already had been extended past the breaking point and was almost completely bereft of antitank weapons and assault guns. The few tanks left to the 112th Panzer Brigade, after the debacle at Dompaire, had been reduced to one Panther and six Mark IV’s. Furthermore the brigade had lost nearly all of its transport and was moving on foot. Harassed as it was by the evening of 22 September, the XLVII Panzer Corps received news of still another threat when OB WEST sent radio warning that an American airborne landing could be expected in the rear of the corps—probably

on the following morning. General Manteuffel asked for permission to withdraw the entire Fifth Panzer Army, but at midnight General Balck refused, citing “the clear Führerbefehl” that the army must reach the 553rd VG Division east of Nancy. All the help Balck’s headquarters could give was one battalion of Flak which was sent to Blâmont, in the rear of the XLVII Panzer Corps, for use against the anticipated airborne attack.33

This threat of vertical encirclement failed to materialize on 23 September. But the 79th Division began to close on the Forêt de Mondon in a series of hand-to-hand engagements and by noon the enemy was retreating to the east, under such cover as the German batteries in the Forêt de Parroy could provide. Although the Forêt de Mondon had been wrested from the German defenders and the area between the Meurthe and Vezouse Rivers freed, the battle had won some time for Lüttwitz and had taken heavy toll among the American battalions taking part. The 3rd Battalion of the 314th Infantry, which finally broke the German hold, suffered nearly two hundred casualties in the frontal assault across the Meurthe and lost most of its officers.34

The 2nd French Armored Division, reinforced by the reserve combat command which had come up from the Moselle, crossed its armored infantry over the Meurthe between Flin and Vathiménil during the night of 22–23 September and sent tank patrols through the southern part of the Forêt de Mondon, reaching Bénaménil on La Vezouse River. There enemy tanks and infantry made a stand and drove off the French. One patrol did succeed in crossing the river on 23 September and chased the headquarters of the 112th Panzer Brigade out of Domjevin. Late in the afternoon a battalion of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, which had been rushed down from the north, retook the town and re-established the river defense line. That night the last German rear guard detachments crossed the river and the XLVII Panzer Corps organized to defend a new position which extended from the Forêt de Parroy to Croismare—on La Vezouse River—followed the river, turned south along the ridge between Ogéviller and Hablainville, and then tied in with the Nineteenth Army at the Meurthe River near Azerailles. Here Lüttwitz’ harassed troops entrenched, and awaited the resumption of the American advance.

The Continuation of the Tank Battles, 24–29 September

After the German attack on 22 September the 4th Armored Division was given a day’s respite, while the American cavalry scouted to the east and the XIX TAC continued to interdict the enemy-held roads and strafe isolated targets designated by the armor. However, prisoners reported that a new attack was in the offing and early on 24 September the blow came—this time delivered by the First Army in the CCB sector, west of Château-Salins.

Two days before, Hitler had repeated his orders that contact must be established with the 553rd VG Division, that all the enemy north of the Marne-Rhin Canal must be destroyed, and—specifically—that the First Army and Fifth Panzer Army must join in the Château-Salins–Moyenvic sector. To effect this junction Field Marshal Rundstedt took the 559th VG Division from the sector north of Metz and assembled it at Morhange, with the 106th Panzer Brigade in support. Division Number 462 was left to cover the gap by extending its front to the north past Thionville. At the same time General Priess and the XIII SS Corps took command east of Nancy.

On the morning of 24 September, CCB was concentrated in the area between Château-Salins and Fresnes-en-Saulnois, screening in front of the 35th Division and awaiting orders to continue the offensive to the northeast. At dawn an unusually heavy concentration of artillery fire broke on the command, and enemy tanks and infantry were in on the American positions before the division artillery could be brought to bear. Two regiments of the 559th VG Division attacked on three sides of the CCB perimeter in a mounting melee. Shortly after 0830 the main enemy effort was launched against the American right flank by a tank thrust from Château-Salins. This coordinated attack threatened to have serious results when, about 1000, the skies cleared and the P-47’s came into the fight. In fifteen minutes the attack was broken and the Germans were in flight, leaving eleven wrecked tanks behind them and about three hundred dead. Although no further assaults were made, the German artillery, firing from the shelter of the Forêt de Château-Salins, continued a heavy shelling all through the afternoon, destroying an American aid station and spraying the area with fragments from time shells. CCB sustained 120 casualties in this action but at the end of the day still held its ground.

Now the Fifth Panzer Army prepared to return to the attack. On the night of 24 September Rundstedt appealed to OKW to abandon the Fifth

Panzer Army counterattack and send the remaining armor north to the Aachen front, where an Allied break-through seemed imminent. But Hitler brusquely ordered Manteuffel to continue the fight. General Manteuffel had asked for two new armored divisions to replace the crippled and decimated panzer brigades. There were no reserves at hand, however, and he had to be content with such elements of the 11th Panzer Division (Wietersheim) as had reached his army. The 11th Panzer Division, popularly known as the “Ghost Division,” was one of the most famous armored units in the Wehrmacht. It had captured Belgrade and then had fought continuously on the Eastern Front, where it was cited three times in 1943 for distinguished action. In February 1944 the division was badly mauled during the Korsun encirclement and had to be transferred to southern France for rest and reorganization. In August it was given the difficult task of covering the retreat of the Nineteenth Army—since it was the only armored division south of the Loire. After the retreat from southern France the division took up position in the Belfort Gap, from which it moved on 18 September to reinforce the Fifth Panzer Army. Although the 11th Panzer Division had lost heavily during the Rhone Valley battles it still had most of its artillery and infantry. However, a Kampfgruppe (consisting of a tank company, the assault gun battalion, and some infantry) had to be left behind in the Belfort region, and a few tanks were destroyed by air attacks on the rail journey to Sarrebourge,35 where the division detrained. When the 11th Panzer Division finally was committed on the Fifth Panzer Army front, General Wietersheim, an able and experienced commander, had only the 110th and 111th Panzer Grenadier Regiments, sixteen tanks, and two batteries at his disposal—hardly the force required for an advance to Nancy. All told, however, the Fifth Panzer Army had about fifty tanks when it resumed the attack.

The fate of the 111th Panzer Brigade on 22 September had prompted General Manteuffel to seek for surprise on 25 September by moving the axis of his attack farther to the north. (Map XX) On the night of 24 September scouting parties reported that Moyenvic was unoccupied and that Marsal was only weakly held. The main attack by the 11th Panzer Division jumped off the next morning at 0900—two hours later than scheduled—because of a steady downpour that slowed up tanks and guns as they moved into position. The thin cavalry screen on the American north flank was easily brushed aside

and the Germans seized Marsal, where, under a smoke screen, they reorganized to fan out in attacks toward the south. One prong of the German drive continued through Moyenvic and by noon had come to a halt at Vic-sur-Seille—finally effecting the junction with the First Army which Berlin had decreed.

This quick success on the north flank dictated a widening of the attack and about 1000 General Manteuffel ordered a general advance along the whole LVIII Panzer Corps front, its object to be the seizure of a line reaching from Moncel-sur-Seille (some seven miles west of Moyenvic), diagonally through Bezange-la-Grande and Bathelémont, back to the canal at Hénaménil where the XLVII Panzer Corps still held. Manteuffel called on Lüttwitz to support the attack from south of the canal with counterbattery fire on the American artillery massed behind the hills northeast of Bathelémont; but such an artillery duel could profit the Germans very little for it is doubtful whether Lüttwitz had a score of guns available in his entire corps. The German attack corps had a fair number of artillery pieces (about two battalions), but, just as in the case of the relative armored strength, the American superiority was pronounced; at least six field artillery battalions were brought into play during the course of the battle.

At noon the enemy began to shoulder his way against CCA’s north flank in an attempt to widen the corridor of assault. Ten tanks rolled down from the north and hit the 37th Tank Battalion, northeast of Juvelize, but were handily beaten off by the American M-4’s—which outnumbered them and held positions on the slopes above the German line of approach. Next, infantry in about battalion strength, reinforced by a few tanks, tried to drive in the outpost lines manned by the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion (southeast of the 37th Tank Battalion), the 25th Cavalry, and the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, the latter two holding on the north flank along a line running west. These attacks continued sporadically throughout the afternoon and evening in a steady rain which curtained off the battleground and left the decision to men, tanks, and guns. The enemy occupied Moncourt, but elsewhere the Americans held their ground and blunted the spearhead of the German drive by successful counterattacks.

During the night General Wood moved CCB down to take over the line of the 320th Infantry (-) between Réchicourt and the canal, on the right flank of CCA, while the 35th Infantry Division occupied the former CCB

sector west of Château-Salins. On 26 September the 4th Armored Division reorganized its front with a slight withdrawal to the west, as part of the shift to the defensive which had been ordered for the Third Army. General Manteuffel seized the opportunity offered by the American withdrawal to report the uncontested occupation of Juvelize and Coincourt as “victories,” and then prepared to resume the attack toward the west.

Manteuffel switched the direction of the LVIII Panzer Corps attack on 27 September so as to bring his main force to bear against the American south flank. An armored task force of about twenty-five tanks was scraped together from the 11th Panzer Division, 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, and the two panzer brigades. These tanks, reinforced by the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 11th Panzer Division, which had just come up from the Nineteenth Army front, were given the mission of making an envelopment by a march along the narrow road between the canal and the Etang de Parroy—following this by an attack to take the camel back, at Hills 318 and 293, and Arracourt. Both Manteuffel and Balck were gravely concerned with the American possession of this camel-back plateau, east of the Arracourt–Bathelémont road, since its two hills rose to command long reaches of the ground held by the Fifth Panzer Army. The attack on 27 September, then, would be a fight to deny the Americans the observation which, coupled with their superiority in artillery, effectively barred the road to Nancy. General Wietersheim, the 11th Panzer Division commander, opposed this new plan, for his experience with American planes and artillery during the retreat from southern France dictated the dispersal rather than the concentration of tanks in attack. Manteuffel, still thinking in terms of his experience with massed armor on the Eastern Front, was adamant—in addition he had been promised that fifty planes would fly cover over his tanks during the attack.

At 0800 the LVIII Panzer Corps (minus the armored task force) began a series of bitter diversionary attacks along the left and center of the 4th Armored Division perimeter. A battalion of grenadiers and a few tanks struck with particular fury against the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion (Lt. Col. Arthur West), which had been withdrawn to the new main line of resistance and had taken over the sector between Bezange-la-Petite and Réchicourt. Colonel West’s battalion occupied a front of some 3,500 yards. Its left flank extended tenuously beyond the edge of Hill 265, west of Bezange; between its right flank and the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion a gap

existed which neither of the battalions had the rifle strength to fill. The German assault bent the thin American line but could not break through.36 At Hill 265 the enemy succeeded in gaining a foothold, but at this point 1st Lt. James H. Fields inspired his men to stand fast, though he had been rendered speechless by wounds in the head and throat. When two German machine guns caught the Americans in a withering cross fire, Fields took up a light machine gun from its dead crew and knocked out both of the German weapons. For gallantry in this action Lieutenant Fields received the Congressional Medal of Honor. On the north flank the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment advanced as far as Xanrey. But while the Germans were reorganizing for a continuation of the attack some American tanks entered the town, under cover of smoke and artillery fire, and killed about 135 of the grenadiers—abruptly terminating this phase of the enemy maneuver.

About 1000, Manteuffel’s armored task force began the main attack, but its advance guard had gone only as far as Fourasse Farm, some 1,800 yards west of Bures, when the American artillery brought the tanks to a halt. During the night General Wietersheim switched the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment around from the north flank and put it in on his south flank to reinforce the tank group. One of its combat patrols filtered through to the north of the farm and captured Hill 318 after a sharp fight. Hill 318, and the plateau from which it projected, now became the focal point for the whole German effort. At daybreak on 28 September the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion retook the hill, but the fight continued through the morning, surging back and forth on the crest. About noon, the 51st got a firm hold. One last enemy counterattack was broken up by shellfire from American batteries to the northeast, raking the flank of the German assault column. In the center of the 4th Armored Division line German infantry and assault guns drove in close to the CCB positions under cover of a smoke screen. But by midafternoon the superiority of the American artillery began to tell, and the appearance of the Jabo’s broke off the action.

When darkness came the Germans again sent a shock force, this time supported by a few tanks, up the forward slope of Hill 318. This assault drove

the Americans back over the crest and onto the reverse slope, where they were caught by a well-executed barrage laid down by German guns. Just before midnight the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion regained the crest, after a preparatory shelling by four battalions of artillery had broken the German hold. The enemy retaliated promptly. CCB was hit by heavy-caliber artillery fire which continued for nearly one hour—causing thirty-five casualties in one company alone. Under cover of this fire the 11th Panzer Division extended its hold on the camel back, took Hill 293, and drove on to seize the high ground at the eastern edge of the Bois du Bénamont. However, the infantry from the 51st, crouched in foxholes close to the crest of Hill 318, refused to give ground.

The German attack had made important gains during the night of 28–29 September, but the 4th Armored Division had added to its estimable record as an assault force and had proved to be equally tough and stubborn on the defensive. Here, as in previous engagements, the XIX TAC had given yeoman support to the American troops fighting on the ground. General Weyland sent 107 fighter-bombers to aid the XII Corps during 28 September. One squadron, the 23rd, made a strike at Bures which nearly leveled the village and cut up the German reserves assembling there, thus weakening still further the ability of the enemy to exploit an attack that had been initiated successfully.

The morning of 29 September broke with a thick fog obscuring the battlefield. The exhausted German infantry tried to push on toward Arracourt but made no headway. Meanwhile, a platoon of medium tanks from the 8th Tank Battalion moved up Hill 318 in the fog, and when the haze finally lifted the tank commander directed the American planes onto the German tanks which had assembled under the screening fog in the valley below. After several mishaps—which included the dropping of propaganda leaflets instead of bombs37—the air-ground team began to close on the enemy. By the middle of the afternoon the Germans were streaming back through Fourasse Farm, and the rout was checked only when a few tanks were brought up to form a straggler line east of Parroy. Remnants of the 2nd Battalion of the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (Captain Schneider) and a few tanks from the Reconnaissance Battalion, 11th Panzer Division, held bravely to their positions in the Bois du Bénamont, all the while under heavy fire from American tank

destroyers and cavalry assault guns. When night came the survivors filtered south through the American lines.38

The back of the Fifth Panzer Army attack was broken on 29 September; nor was there any further possibility of creating a new force for a continued effort to reach the Moselle River. During the afternoon, while the remnants of Manteuffel’s armored task force were being hunted down around Bures by the fighter-bombers, General Balck made a personal visit to Rundstedt’s headquarters at Bad Kreuznach. He told the C-in-C West that he still intended to wipe out the Pont-à-Mousson bridgehead and recover the Moselle defense line, but that he would need a “minimum” of three additional divisions, forty or fifty tanks, twenty or thirty assault guns, fifty antitank guns with prime movers, four battalions of heavy artillery, and four battalions of engineers. Rundstedt had no troops to give Army Group G, for Hitler and Jodl had decided to throw the few reserves still available on the Western Front into an attack against the Second British Army, at this time driving forward to surround the Fifteenth Army between the Rhine and the Maas. Balck, therefore, had no choice but to order the Fifth Panzer Army to go over to the defensive.

Both Balck and Manteuffel must have felt uneasy about giving up a project cherished by Hitler, for both hastened to go on record in their respective War Diaries. Balck wrote that Army Group G always had attempted to build up sufficient tactical reserves to make counterattacks possible, but that local commanders constantly had whittled away such reserves by committing them wherever a thin portion of the line was menaced by the enemy. He added, furthermore, that withdrawals had been made without permission of the Army Group headquarters, and that losses of towns and territory had occurred which were never reported to the higher headquarters. Manteuffel contented himself with repeating the report made by General Krueger on the battles fought in the previous days by the LVIII Panzer Corps. Said Krueger, the enemy had superiority in the air and in the artillery arm. There was no cover in this area for tanks and infantry; whenever the weather cleared the American planes descended on the corps—while all requests for the Luftwaffe were answered by reports that the German airfields were weathered in. American artillery was ceaseless, firing day and night—“a regular drum fire.”

Finally, the Americans held the high ground, looking deep into the corps area, and so long as Hill 318 was in American hands no success was possible.

The Lorraine tank battles had ended, except for a last American tank sweep on 30 September, and this sector relapsed into quiet. The 4th Armored Division took up stabilized positions north and east of Arracourt, while the German infantry dug in a few hundred yards away. On 12 October Wood’s division was relieved by the 26th Division and went into corps reserve.