Chapter 3: Main Effort in the Eifel

In early December, before the Germans struck in the Ardennes, the Supreme Commander had intended to maintain unremitting pressure on the enemy through the winter in hope of forcing him back to the Rhine. Converging attacks by the 21 and 12th Army Groups across the Rhine were to be launched in early summer, 1945. To criticism that pressure all along the line, the broad-front strategy, was indecisive, General Eisenhower had replied: “It appears to me that wars are won in successive stages and until we get firmly established on the Rhine we are not in position to make the attack which we hope will be fatal to the other fellow.”1

That the Allies were not indeed in such a position seemed fully attested by the German counteroffensive. Studying possible courses of action to follow after eliminating the German gains, the planning staff at SHAEF drew a plan that one critic called “almost a painstaking, uninspired, plodding way through to Berlin.”2 The plan actually did call for more methodical moves than before, but the timetable, as events were to prove, embodied considerable optimism.

Pointing out that even before the counteroffensive, Allied forces north and south of the Ardennes had been insufficient to insure reaching the Rhine, the planners advocated concentrating on one section of the front at a time, starting with elimination of the Colmar pocket in the French sector, and forming a SHAEF reserve of six divisions. The planners proposed then to turn to an offensive north of the Ardennes while assuming the defensive elsewhere. Not until the 21 and 12th Army Groups had reached the Rhine from Wesel south to Bonn were attacks to be resumed in the south. Not until March, after Allied forces had reached the Rhine all along the front, was anybody to cross the Rhine.3

Although never formally approved, this plan fairly represented the new emphasis on defeating the Germans west of the Rhine by stages. As General Eisenhower wrote to Field Marshal Montgomery:

We must substantially defeat the German forces west of the Rhine if we are to make a truly successful invasion of the interior of Germany with all forces available. ... As I see it, we simply cannot afford the large defensive forces that would be necessary if we allow the German to hold great

bastions sticking into our lines at the same time that we try to invade his country.4

Of eighty-five Allied divisions expected to be available in early summer, Eisenhower estimated that forty-five would be needed in defense and reserve if the Allies were at that time holding a line similar to the one actually held on 15 January, but only twenty-five if the line followed the Rhine.5

It was the SHAEF plan for cleaning up the area west of the Rhine before beginning a decisive thrust deep into Germany that incited objections from the British Chiefs of Staff. The British Chiefs feared that the plan meant a dispersion of strength and considered that Eisenhower had only enough superiority on the ground to make a single powerful thrust, backed by enough fresh divisions to maintain momentum. This was the basic point at issue when the British Chiefs on 10 January asked formally for a review of strategy by the Combined Chiefs which led to the Supreme Commander’s plan being discussed at the end of January at Malta.6

Convinced of the soundness of the plan and assured of backing by the U.S. Chiefs of Staff, General Eisenhower continued to lay the groundwork for a renewed offensive even while waiting for the Combined Chiefs to rule, though an element of the provisional hung over all plans made during the period. The Supreme Commander directed specific attention to what he considered the main effort, a drive to reach the Rhine north of the Ardennes in preparation for an eventual attack north of the Ruhr industrial area. On 18 January he ordered the 21 Army Group commander, Montgomery, to prepare plans for such an offensive.7

General Bradley’s Proposal

Through the course of the Ardennes fighting, the 12th Army Group commander, General Bradley, had been aware that General Eisenhower intended a return to a main effort in the north. Since the Ninth Army was to remain under Montgomery’s command and participate in that drive, Bradley eventually would have to relinquish divisions to bring the Ninth Army to a strength at least equal to that which had existed before General Simpson had released divisions to fight in the Ardennes. General Bradley nevertheless hoped to be able to continue to attack with his army group beyond the Ardennes to cut through northern reaches of the Eifel to the Rhine.8

Against the obvious difficulties of attacking in winter over countryside equally as inhospitable as that of the Ardennes and through the West Wall, Bradley could argue that an offensive in the Eifel fitted best as a continuation of the attack to reduce the bulge. It would avoid a pause to regroup; it would insure a constant and mounting pressure against the Germans; it would capitalize on probable German expectation of an Allied

return to the offensive in the north; and it would put the 12th Army Group in a position to unhinge the Germans in front of the 21 Army Group. To at least some among the American command, rather delicate considerations of national prestige also were involved, making it advisable to give to American armies and an American command that had incurred a reverse in the Ardennes a leading part in the new offensive.9

Attacking through the Eifel also would avoid directly confronting an obstacle that had plagued Bradley and the First Army’s General Hodges all through the preceding autumn, a series of dams known collectively as the Roer River dams in rugged country along headwaters of the river near Monschau. So long as the Germans retained control of these dams, they might manipulate the waters impounded by the dams to jeopardize and even deny any Allied crossing of the normally placid Roer downstream to the north.

By pursuing an offensive that the 12th Army Group’s planning staff had first suggested in November, General Bradley saw a way to bypass and outflank the dams and still retain his ability to support a main effort farther north.10 Bradley intended to attack northeastward from a start line generally along the German frontier between Monschau and St. Vith and seize the road center of Euskirchen, not quite thirty miles away, where the Eifel highlands merge with the flatlands of the Cologne plain. This would put American forces behind the enemy’s Roer River defenses in a position to unhinge them.

To the Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, Bradley’s proposal had the double virtue of being a logical follow-up to the job of reducing the bulge and of accomplishing part of the general buildup along the Rhine that he intended before launching a major offensive deep into Germany. Yet Eisenhower saw a 12th Army Group offensive as no substitute for a main effort later by the 21 Army Group. Since Montgomery had considerable regrouping to do before his offensive would be ready, Eisenhower agreed to let Bradley hold on temporarily to the divisions earmarked for the Ninth Army and take a stab at the Eifel.

General Eisenhower nevertheless sharply qualified his approval. If the attack failed to show early promise of a “decisive success,” he intended halting it and shifting strength to the Ninth Army.11 The definition of decisive success was apparently a quick, broad penetration of the West Wall.12 Even beyond that the operation was to be subject to review at any time, and General Bradley was to be prepared to pass quickly to the defensive, relinquishing divisions to the Ninth Army.13

The Eifel Highlands

Terrain would set even narrower limits on tactics in the Eifel than in the Ardennes. Streams in the Eifel have cut even deeper into the surface of the old plateau, and unlike the patchwork patterns

in the Ardennes, the forests are vast. Although roads are fairly extensive, they twist and climb in and out of the stream valleys and through the narrow confines of farm villages.

Well defined on the southeast by the convolutions of the Moselle River, the Eifel in the north and northeast merges irregularly into the Cologne plain, roughly on a line from Aachen through Euskirchen to the Rhine some fifteen miles south of Bonn. From the Belgian border to the Rhine the greatest depth of the Eifel is about forty-five miles. In width, the region extends along the frontiers of Belgium and Luxembourg from Aachen to Trier, a distance of some seventy-five miles.

Close to the frontier, two hill masses or ridges stand out. Most prominent is the Schnee Eifel, a forested ridge some ten miles long, roughly parallel to the Belgian border east of St. Vith, rising abruptly from the surrounding countryside to a height of just over 2,000 feet. The other is an L-shaped ridgeline or hill mass forming a bridge between the Hohe Venn and the Schnee Eifel, which may be called from its highest point at the angle of the L, the Weisserstein. This ridgeline generally defines the Belgian-German border southeast of Monschau, then swings to the northeast. Part of the north-south watershed for the region, the Weisserstein in conjunction with the Hohe Venn and the Schnee Eifel also serves as the watershed between Eifel and Ardennes.

Except for the Moselle the rivers of the Eifel are relatively minor streams, but they are important militarily because of their deep, twisting cuts. The main ones are the Our, running along the frontier and joining the Sauer before entering the Moselle; the Prüm, forming another north-south barrier a few miles beyond the Schnee Eifel; the Ahr, draining from the Hohe Eifel northeastward to the Rhine; and the Roer. Two of the more important towns within the generally pastoral region are Prüm and Bitburg, the latter in a relatively open stretch of countryside southeast of Prüm.

The northernmost reaches of the Eifel, the region that General Bradley hoped to avoid by making his attack south of the Roer dams, has no general geographical name, but American soldiers who had fought there had come to know it as the Hürtgen Forest. Although not so high as other parts of the Eifel, this is one of the more sharply compartmented sectors and at the time was almost completely covered with forest and the debris of the September to December battles.

The route that General Bradley chose for his main attack cut across the narrow northwestern corner of the Eifel, avoiding the rugged Hürtgen Forest. From the Weisserstein several radial ridges stretch northeastward toward Euskirchen and Bonn, and along two of these run good roads that converge at Euskirchen. Although the Roer reservoirs and the Schnee Eifel would confine the frontage of the main effort to a narrow ten to twelve miles, the advantages outweighed this factor.

Athwart the selected route ran the belt of concrete pillboxes, minefields, concrete antitank obstacles (dragon’s teeth), and entrenchments of the West Wall. From the Moselle to the northern tip of the Schnee Eifel, the fortified zone was relatively shallow, usually not as much as a mile, but it drew strength from the difficult terrain, including the gorges of

the Our and the Sauer and the heights of the Schnee Eifel. Farther north the line split into two bands that diverged as much as eleven miles. Pillboxes in the second band were considerably fewer than in the first.

The Enemy in the Eifel

It was peculiarly difficult to guess in January how strongly the Germans might defend the West Wall, though the 12th Army Group’s intelligence staff assumed that the enemy would make as stalwart a stand as possible, both because of a need to hold the Allies at arm’s length from the Ruhr and because of Hitler’s seemingly fanatic refusal to yield ground voluntarily. The large-scale Russian offensive that had begun on 12 January increased the likelihood of a determined defense of the West Wall even though the means were slipping away into the eastern void.14

Still operating under the Führer’s directive of 22 January to complete an orderly withdrawal from the Ardennes into the West Wall, German commanders were, as expected, pledged to defend the fortifications, but they were looking forward to at least temporary respite once they gained the fortified line. Detected shifts of some Allied units already had reinforced the generally accepted view that the Allies would return to a major thrust in the north in the direction of Cologne, so that the Germans naturally expected pressure to ease in the center. Because the V U.S. Corps appeared to be readying an attack from positions southeast of Monschau, the Fifth Panzer Army assumed that the Americans intended a limited attack to gain the Roer dams. Remarking relatively favorable terrain for armor around Bitburg, the Seventh Army believed that the Third U.S. Army might try to establish a bridgehead over the Our River pointing toward Bitburg but anticipated some delay before any attempt to exploit. No one at the time expected a major thrust through the Eifel.15

As January neared an end, the Germans would require another week to get the bulk of the Sixth Panzer Army loaded on trains and moving toward the east, but so occupied were the designated divisions with the move that no longer could they provide assistance in the line. Full responsibility for the defense lay with Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army on the north and Brandenberger’s Seventh Army on the south.

Even as the Americans argued the merits of a thrust through the Eifel, the German command was making the first of three adjustments designed to counter the expected Allied return to a main effort in the north. The commander of Army Group B, Field Marshal Model, transferred the XIII Corps to the Seventh Army, in the process drawing a new inter-army boundary running eastward from a point south of St. Vith through Prüm, a northward extension of responsibility for the Seventh Army. Although the boundary with the Fifteenth Army remained for the moment about three miles south of Monschau, this boundary too was to be adjusted northward on 5 February to give the southernmost corps of the Fifteenth Army to Manteuffel’s command, again a side-slipping

to the north. The third step, an exchange of sectors between headquarters of the Fifth Panzer and Fifteenth Armies in order to put a panzer command in the path of the expected Allied main effort, was destined to be delayed by the attack in the Eifel.

As events developed, early stages of the American drive into the Eifel would pass north of the Seventh Army, striking primarily at the front of the Fifth Panzer Army, manned by the LXVI Corps (General der Artillerie Walter Lucht) and the LXVII Corps. It would later involve also the extreme south wing of the Fifteenth Army, a responsibility of the LXXIV Corps (General der Infanterie Karl Püchler).

Although the divisions committed in this sector still included such illustrious names as the 3rd Parachute and 9th Panzer, these were in reality little more than remnants of true divisions; and while they still fought, the German command would make little effort to rebuild them. The Germans planned instead to pull these once-elite formations from the line for rehabilitation in keeping with the theory that some respite would follow withdrawal into the West Wall. The Eastern Front had priority on replacements at this point in any case, and such replacements as did reach the west went to the infantry and Volksgrenadier divisions that were to stay behind to hold the fortifications.

In a general way, Allied intelligence anticipated this policy. It meant, in sum, that in an effort to create a reserve, the Germans would have to thin their ranks in the Eifel to a point where no coherent line would exist. Defense would have to be by strongpoints, relying of necessity on scraps and scratch outfits. The ragged ranks might be stiffened a little with concrete and barbed wire, their task eased by bad weather and rugged terrain, but the balance of forces remained hopelessly against them. Recognizing this situation, the First U.S. Army’s G-2, Col. Benjamin A. Dickson, expressed some optimism about the chances of swiftly cracking the West Wall and piercing the Eifel.16

In the last analysis, as the Third Army staff pointed out, quick success depended primarily on the enemy’s will to fight. Poorly trained and ill-equipped troops could give good accounts of themselves even in the fortifications of the West Wall and the snowbound compartments of the Eifel only if they wanted to.17 As the drive toward Euskirchen got under way, just how much the individual German soldier still wanted to fight was the question.

A Try for Quick Success

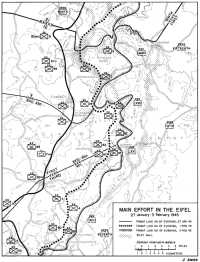

The first phase of the offensive was to be a frontal attack aimed at penetrating the West Wall on a 25-mile front from Monschau to Lützkampen, near the northern tip of Luxembourg. (Map 1) General Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps on the right wing of the First Army was to make the main effort. Holding two infantry divisions in reserve for exploitation, Ridgway was to strike with two others to pierce the fortified line between the Schnee Eifel and the Weisserstein astride the Losheim Gap. Named after a town along the border, the gap is a narrow corridor that in 1914, 1940, and 1944 had served German armies well as

Map 1: Main Effort in the Eifel, 27 January-3 February 1945

Men of the 82nd Airborne Division pull sleds in advancing through the Ardennes snow.

a débouché. Once through the gap, the airborne corps would have access to one of the main routes leading to Euskirchen.

At the same time, General Huebner’s V Corps on the north was to penetrate the western spur of the West Wall in the Monschau Forest and protect the army’s left flank by crossing northern reaches of the Weisserstein and seizing Schleiden and Gemünd, both important road centers astride a more circuitous but usable route to Euskirchen. To exploit success by either Huebner or Ridgway, the First Army’s General Hodges held in reserve Collins’s VII Corps with two infantry and two armored divisions.18

The Third Army’s role in this first phase of the operation was to protect the First Army’s right flank. General Patton planned to attack at first only with Middleton’s VIII Corps, whose northernmost division, the 87th, was to advance abreast of the XVIII Airborne Corps to the vicinity of Losheim while the 4th and 90th Divisions to the south broke

through the West Wall along and just south of the Schnee Eifel. These two divisions then were to block to the southeast, whereupon Patton intended to insert a fourth division on the right of the 87th to advance northeast with the 87th. With protection of the First Army assured, Patton then might advance with three corps abreast northeast to the Rhine or turn southeast to take the West Wall in flank and roll it up southward to Trier.19

The line of departure for the attack was irregular. In the north, where units of the V Corps still held the positions on which they had stabilized the northern shoulder of the counteroffensive some weeks earlier, it ran from Monschau south to the ridgeline that served as an outpost of the Hohe Venn near Elsenborn. Below that point, the attack would begin from positions gained during the last few days of fighting. Those generally followed the highway leading into St. Vith from the north. Beyond St. Vith the line retracted to the southeast generally along the trace of the Our River and the German frontier.

Thus the XVIII Airborne Corps still was from eight to twelve miles away from the forward pillboxes of the West Wall, which followed the eastward-bulging contour of the Belgian-German border. Since the countryside in this bulge is either heavily wooded or studded with villages, the troops making the main effort faced a difficult task even to reach the fortified line.

The 1st Infantry and 82nd Airborne Divisions of the XVIII Airborne Corps opened the attack on 28 January. The next day the VIII Corps attacked with the 87th, 4th, and 90th Divisions. On the 30th, the V Corps jumped off in the north.

The story of all these first attacks could be told almost in a word: weather. By the end of January the month’s unusually heavy snowfall and low temperatures had left a snow cover one to two feet deep everywhere and in some places drifts up to a man’s waist. Snow glazed the hills, choked the valleys and the roads, and hid the enemy’s mines. On the first day, it snowed again all day and into the night.20

Plowing through the deep snow, the two divisions of the XVIII Airborne Corps encountered only sporadic opposition, often taking the form of occasional patrols or scattered rifle fire. Yet men marching all day through the snow even without sight or sound of the enemy were exhausted when night came from sheer physical exertion. It would take the two divisions four full days to traverse the eight to twelve miles from their jump-off positions to the high ground confronting the West Wall in the Losheim Gap.

It was in some ways a curious twilight war. One night, for example, a patrol from the 82nd Airborne Division, sent to investigate a report that the adjacent 87th Division had occupied a village near Losheim, found no soldiers, American or German. Behind blackout curtains the villagers had their lights on. Now and then a shell crashed nearby, and between times the paratroopers could hear babies crying.

On the other hand, an enemy who was nowhere in particular might be anywhere.

Traffic jam on a slick Ardennes road

As happened at the village of Holzheim, where on 29 January a company of the 82nd Airborne’s 508th Parachute Infantry seized 80 prisoners while overrunning the village. Leaving the prisoners under a 4-man guard, the bulk of the company had moved on when a German patrol sneaked back into the village, overpowered the guards, and freed the prisoners. Onto this scene stumbled the company’s first sergeant, Leonard A. Funk, Jr. Surprised, he pretended to surrender, but as the Germans moved to disarm him, he swung his submachine gun from his shoulder and opened fire. Seizing German weapons, the 4-man guard joined the fight. In the melee that ensued, 21 Germans were killed and the rest again surrendered.21

Or as happened one night early in the attack when a platoon of paratroopers advanced down a narrow road between three-foot banks of snow thrown up by German plows. Three tanks rumbled between the files of riflemen. Out of the darkness, dead ahead, suddenly appeared a German company, marching forward in close formation. The banks of hard snow

on either side of the road meant no escape for either force. The paratroopers opened fire first, their accompanying tanks pouring withering machine gun fire into the massed enemy. Surprised and without comparable fire support, unable to scatter or retreat, the Germans had no chance. Almost 200 were killed; a handful surrendered. Not an American was hurt.

Foot troops moved slowly, but they could always move. Behind them artillery, supply, service, and armored vehicles jammed the few cleared roads. Especially congested was the zone of the 1st Division where every few hundred yards a partially destroyed village knotted the roadnet. When leading riflemen of the 1st Division reached the West Wall, only one artillery battalion had managed to displace far enough forward to provide support. Trucks bringing food and ammunition often failed to get through. Had the opposition been determined, the traffic snarls could have proved serious; as it was, the only tactical result was to slow the advance.

It was 1 February—the fifth day of the attack—before the two divisions of the XVIII Airborne Corps could begin to move against the West Wall itself. Close by on the right, reflecting the day’s delay in starting to attack, the Third Army’s 87th Division needed yet another day to reach the pillboxes.

North and south of the main effort, the V Corps and the bulk of the VIII Corps hit the West Wall earlier. One division near Monschau, the 9th, northernmost unit of the V Corps, was already inside the fortified zone at the time of the jump-off on 30 January.

The 9th Division (Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig), moving southeast from Monschau, and the 2nd Division (Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson), striking north through the twin border villages of Krinkelt-Rocherath, near Elsenborn, were to converge at a road junction within the Monschau Forest astride the northern end of the Weisserstein at a customs house called Wahlerscheid. Both divisions would have to pass through Wahlerscheid, a pillbox-studded strongpoint, before parting ways again to continue toward Schleiden and Gemünd. Contingents of the 99th Division meanwhile were to clear the Monschau Forest west of the converging thrusts, and the Ninth Army’s southernmost division was to make a limited objective attack to protect the left flank of the attacking corps.

In the long run, the V Corps would benefit from the fact that its attack struck along the boundary between the Fifth Panzer and Fifteenth Armies, but in the early stages the presence of West Wall pillboxes would mean stiffer resistance than that against the main effort. Yet nowhere was the resistance genuinely determined. The Germans of General Püchler’s LXXIV Corps and General Hitzfeld’s LXVII Corps simply had not the means for that kind of defense. As elsewhere, deep snow was the bigger problem, while ground fog and low overcast restricted observation for artillery and denied participation by tactical aircraft altogether.

Approaching within a few hundred yards of the Wahlerscheid road junction late on 31 January, the 9th Division repulsed a counterattack by an understrength German battalion. Soon thereafter patrols discovered that the pillboxes at Wahlerscheid were organized for defense only to the south, a response to the

fact that the 2nd Division in December had hit these same pillboxes from the south in the abortive attack toward the Roer dams. The 9th Division’s 39th Infantry moved in on the rear of the fortifications early on 1 February. The 2nd Division in the meantime was fighting its way through Krinkelt-Rocherath, scene of an epic stand by the same division during the counteroffensive, and then moving into the Monschau Forest to come upon Wahlerscheid from the south.

As night came on 1 February, both the 2nd and 9th Divisions were ready to file past Wahlerscheid. In three days the attack of the V Corps had begun to show genuine promise.

On the south wing of the offensive, the 4th (General Blakeley) and 90th Divisions (Maj. Gen. Lowell W. Rooks) of the VIII Corps at the same time had run into the stiffest fighting of all, partly because of the obstacle of the Our River. The lines of departure of the two divisions lay close to the Our, and for the 90th and the right regiment of the 4th, crossing the river was the first order of business. Narrow and shallow, the Our was frozen solid at some points and easily fordable at others, but steep, slippery banks were a barrier to wheeled traffic and, as it turned out, to tracked vehicles as well. Yet what made the river most difficult was that it was tied into the West Wall defenses. Although the main line lay two to three miles behind the river, the Germans had erected at every likely crossing point fortified outpost positions.

Aiming at the southern end of the Schnee Eifel, one regiment of the 4th Division on the first day, 29 January, tried to cross the Our four miles southeast of St. Vith. As the leading battalion approached the crossing site, a fury of small arms fire erupted from the east bank. Although one rifle platoon got across before the worst of the firing began, the rest of the battalion backed off to look for another site. Casualties were relatively light—for the entire regiment for two days, 9 killed, 29 wounded—but it was noon the next day before all men of the leading battalion were across the Our.

A few miles to the south two regiments of the 90th Division had much the same experience. The leading battalions of each regiment came under intense fire at the selected crossing sites opposite the German outposts, but individual companies managed to maneuver to the south to cross the river and come upon the opposition from the rear.

Despite these successes, the 4th and 90th Divisions advanced only slowly through deep snow against scattered but determined nests of resistance for the next three days. Partial explanation lay in that both divisions were facing the 9th Panzer Division, a shell of a unit but one still capable of steadfast defense at selected points. By 1 February the 90th Division was in sight of the West Wall around the villages of Heckhuscheid and Grosskampenberg, while the 4th Division still had several villages to clear before climbing the slopes of the Schnee Eifel.22

These two divisions were destined to continue their attacks into the West Wall but as part of another operation. On 1 February, the Damocles sword that had hung over the 12th Army Group’s offensive from its inception suddenly fell.

A Shift to the North

On 1 February General Eisenhower ordered General Bradley to cancel the 12th Army Group’s drive on Euskirchen and shift troops north to the Ninth Army.23 He made the decision even though Bradley’s thrust, while slowed by weather and terrain, was encountering no major opposition from the Germans. Only a complete breakthrough could have saved Bradley’s offensive, and that was yet to come.

Several considerations prompted the Supreme Commander’s decision. Continuing pressure from Field Marshal Montgomery, some feeling of pressure emanating from the meeting of the Combined Chiefs at Malta, Eisenhower’s own unswerving conviction that the best way to victory was in the north against the Ruhr—all played a part. Also, Eisenhower in mid-January apparently had given Montgomery at least an implicit promise that he would make a decision on Bradley’s offensive by the first day of February.24

Eisenhower’s order halting the Eifel offensive was in its formal, written form clear-cut. “It is of paramount importance,” the directive said, “... to close the Rhine north of Düsseldorf with all possible speed.”25 To achieve this, the First Canadian Army was to attack not later than 8 February and the Ninth Army not later than 10 February. The Ninth Army was to receive the equivalent of the resources loaned the 12th Army Group at the start of the Ardennes counteroffensive, or at least five divisions. With thinned ranks, Bradley’s armies were to go on the defensive except in the north where the First Army was to seize the Roer River dams and, subsequently, to jump the Roer to protect the Ninth Army’s right flank.

Informally, General Eisenhower modified these terms considerably. Even though Bradley was to relinquish troops immediately to the Ninth Army, the Supreme Commander would allow his offensive in the Eifel to continue until 10 February with the declared objective of gaining a line from Gemünd to Prüm that would include the Weisserstein and the Schnee Eifel and thus afford control of the Losheim Gap for possible future operations. Yet no matter how far this attack had progressed by 10 February, the First Army from that time was to concentrate on a primary mission of attacking across the Roer to protect the Ninth Army’s flank.26

Disappointed with the Supreme Commander’s decision, General Bradley nevertheless took hope in the possibility that he later might turn the First Army’s attack across the Roer to the south, perhaps to join in a thrust by the Third Army to clear the entire Eifel region. In that General Eisenhower granted the Third Army permission to “continue the

probing attacks now in progress,” on the theory of preventing the enemy from shifting reinforcements to the north and with a view to taking advantage of any chance to improve the army’s position for future action, Bradley found real encouragement. At headquarters of the Third Army “probing attacks” were popularly known as the “defensive-offensive,” which meant, in more widely understood terminology, a major attack. Bradley knew, too, that the Supreme Commander himself well understood General Patton’s special lexicon.27

Patton’s orders, issued on 3 February, scarcely mentioned defense. The Third Army, Patton directed, was to continue to attack on its left to seize Prüm, to drive northeast with its right from the vicinity of Echternach to take Bitburg, and to be prepared to continue to the Rhine.28

Since the job of taking Prüm fell naturally to the VIII Corps and thus constituted a continuation of the attack then in progress, though in a different context, the Third Army’s drive into the Eifel was barely troubled by the decision of 1 February. The First Army was more severely straitened. While General Patton gave up only two divisions to the Ninth Army, one of which was an inexperienced unit from the army reserve, General Hodges had to surrender the two reserve infantry divisions of the XVIII Airborne Corps and the three divisions of the VII Corps that had been standing by to exploit in the Eifel. Although headquarters of the VII Corps was to remain under the First Army, General Collins was to assume responsibility for the southern portion of the Ninth Army’s Roer River line, the same front the corps had held before the counteroffensive, and prepare to attack to protect the Ninth Army’s flank. In addition, the V Corps had to mount an attack against the Roer dams.

The First Army was to try again to penetrate the West Wall in the Eifel, but under the revised conditions chances of decisive success were meager.

An End to the Offensive

For four more days, through 4 February, the thrusts of the XVIII Airborne Corps and the V Corps continued much as before, particularly in the zone of the airborne corps where the 1st Infantry and 82nd Airborne Divisions at last entered the West Wall. While not every pillbox was manned, the cold, the snow, the icy roads hindering support and supply, and the strength lent the defense by concrete shelters still imposed slow going. By 4 February the two divisions had advanced little more than a mile inside the German frontier, although a sufficient distance to insure control of the first tier of villages on a five-mile front within the Losheim Gap. The advance represented a penetration of the densest concentration of pillboxes in this part of the West Wall.

The V Corps meanwhile made substantially greater progress. Indeed, had any authority still existed to turn the Eifel drive into a major offensive, the advances of the V Corps after clearing the Wahlerscheid road junction on 1 February might have been sufficient to justify alerting the forces of exploitation.

On 2 February both the 2nd and 9th Divisions pushed almost four miles beyond Wahlerscheid, one in the direction of Schleiden, the other, Gemünd.

Much of their success again could be attributed to the luck of striking astride the boundary between German units. As early as 29 January the northernmost unit of the LXVII Corps, the 277th Volksgrenadier Division around Krinkelt-Rocherath, had lost contact with the southernmost unit of the LXXIV Corps, the 62nd Infantry Division, whose southern flank was at Wahlerscheid. Even after the 277th Volksgrenadiers began to withdraw into the West Wall on the last two days of January, no contact or even communication existed between the two units.29

In driving southeast from Monschau, the 9th Division had virtually wiped out the 62nd Infantry Division. As units of both the 2nd and 9th Divisions poured northeast through the resulting gap at Wahlerscheid on 2 February, outposts of the 277th Division on higher ground two miles to the southeast could observe the American columns, but the 277th’s commander, Generalmajor Wilhelm Viebig, had no way of determining what was going on. Although Viebig’s artillery could have damaged the U.S. units, so seriously depleted were his ammunition stocks that he decided to fire only if the Americans turned in his direction.

As darkness came on 2 February, Viebig’s corps commander, General Hitzfeld, learned of the penetration. Ordering Viebig to extend his flank to the north, he also managed to put hands on small contingents of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, which had been withdrawn from the line for refitting. Yet despite these countermoves, the 9th Division by nightfall of 3 February stood less than two miles from Gemünd, the 2nd Division only a few hundred yards from Schleiden.

Had the Americans been intent on exploiting their limited penetration, Hitzfeld would have been hard put to do anything about it, but the hope of major exploitation through the Eifel by the First Army was beyond recall. General Hodges on 4 February made it official with a letter of instructions spelling out various shifts of units for his newly assigned tasks.30 Not only was the VII Corps to move northward to take over a portion of the Ninth Army’s Roer River line but the XVIII Airborne Corps also was to shift to assume responsibility for a part of the Roer line adjoining the VII Corps. The V Corps was to extend its positions southeastward to relieve the airborne corps while at the same time attacking to seize the Roer dams.

Occurring late on 6 February, relief of the airborne corps signaled an end to the offensive in this part of the Eifel. The line as finally established ran along high ground overlooking Gemünd and Schleiden from the west, thence southeastward across the northeastern arm of the Weisserstein to the boundary with the Third Army near Losheim.

Blessed from the first with little more than ambition, the main effort in the Eifel had ground to a predictable halt.