Chapter 4: The Roer River Dams

In one of the more sharply etched sectors of the Eifel, a few miles northeast of Monschau, German civil engineers over the years had constructed seven dams to impound and regulate the flow of the waters of the Roer River and its tributaries. These were the dams the American soldier had come to know collectively as the Roer River dams, with particular reference to the two largest, the Urft and the Schwammenauel.

Constructed just after the turn of the century on the Urft River downstream from Gemünd, near confluence of the Urft and the Roer, the Urft Dam creates a reservoir (the Urftstausee) capable of impounding approximately 42,000 acre-feet of water. Built in the mid-1930’s a few miles to the north on the Roer near Hasenfeld, the Schwammenauel Dam creates a reservoir (the Roerstausee) capable of impounding about 81,000 acre-feet. The Urft Dam is made of concrete; the Schwammenauel of earth with a concrete core. It was these two dams that the Germans might destroy or open the gates of to manipulate the waters of the Roer, flooding a low-lying valley downstream to the north in the vicinity of the towns of Düren and Jülich, washing out tactical bridges, and isolating any Allied force that had crossed the river.1

From September through mid-November, 1944, General Hodges’ First Army had launched three separate one-division attacks through an almost trackless Hürtgen Forest in the general direction of the dams, though with other objectives in mind. A combination of difficult terrain and unexpectedly sharp German reaction had stopped all three attacks well short of the dams. Realizing at last the importance of the dams to German defense of the Roer River line, the American command had tried to breach them with air strikes, but these too failed. In December a ground attack aimed specifically at seizing the dams had been cut short by the counteroffensive in the Ardennes.2

Those attacks launched through the Hürtgen Forest had been directed toward commanding ground at the town of Schmidt, two miles north of the Schwammenauel Dam The short-lived December attack had been planned as a two-pronged thrust with two divisions coming upon the dams from the south while another pushed northeastward from the vicinity of Monschau along the north bank of the Roer to Schmidt. Although the deep cut of the Roer and

General Huebner

the reservoirs themselves would have imposed a tactical divorce on the two thrusts, the best approach to the Urft Dam was from the south and the high ground at Schmidt was essential to gaining and holding the Schwammenauel Dam.

As the new V Corps commander, General Huebner, planned the February attack on the dams, he apparently had the earlier planning in mind. Furthermore, attacks then under way as part of the fading drive into the Eifel fitted in with the two-pronged pattern of the earlier plan. The drives of the 2nd and 9th Divisions through Wahlerscheid on Gemünd and Schleiden had the secondary effect of threatening the Roer dams from the south, while a limited objective attack staged by the southernmost division of the Ninth Army to protect the left flank of the First Army had the secondary effect of setting the stage for a thrust northeastward from Monschau toward the Schwammenauel Dam.

This division of the Ninth Army was the 78th (Maj. Gen. Edwin P. Parker, Jr.). Through the Ardennes fighting the division had continued to hold positions near Monschau that had been reached in the December attack toward the dams. It was a foregone conclusion that when the boundary between the First and Ninth Armies was adjusted northward, the 78th would pass to the First Army and become the logical choice for renewing the attack on the Schwammenauel Dam. Begun on 30 January, the division’s limited objective attack to protect the First Army’s left flank thus was a first step toward capturing the Schwammenauel Dam.

The 78th Division occupied a small salient about two miles deep into the forward band of the West Wall on a plateau northeast of Monschau. Containing sprawling villages as well as pillboxes, the plateau was one of the few large clearings along the German border between Aachen and St. Vith. As such, it represented a likely avenue for penetrating the West Wall and had been so used, though without signal success, in an attack in October. For want of a better name, the area has been called the Monschau corridor, though it is not a true terrain corridor, since entrance to it from the west is blocked by the high marshland of the Hohe Venn and farther east it is obstructed by dense forest and the cut of the Roer River.

The enemy there was an old foe, having held the sector when the 78th made its first attack in mid-December and

having tried in vain to penetrate the 78th lines in early stages of the counteroffensive. This was the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division with a strength of about 6,000 men.3 The division was a part of Püchler’s LXXIV Corps of the Fifteenth Army, destined to be transferred on 5 February to control of the Fifth Panzer Army.4

The object of the limited attack was to extend the 78th Division’s holdings to the south and southeast to gain the north bank of the Roer River from Monschau to Einruhr, the latter guarding passage of the Roer along a highway leading southeast to Schleiden. The assignment was to be divided between the 311th Infantry on the east and the 310th Infantry on the west, each responsible for taking two of five villages in the target area. Attached to the 78th Division, Combat Command A (CCA) of the 5th Armored Division was to take the fifth village in the center with the help of a battalion of the 311th Infantry. Because the 310th Infantry would be rolling up the West Wall as it advanced, a platoon of British flame-throwing tanks, called Crocodiles, was assigned in support.5

The attack began with a good break. Although the division commander, General Parker, had intended a half-hour artillery preparation, General Simpson, with an eye toward building a reserve for the Ninth Army’s coming offensive, cut the ammunition allocation so drastically that Parker had to reduce the preparation to five minutes. Accustomed to longer shelling before an American attack, the Germans in the pillboxes in front of the 310th Infantry waited under cover for the fire to continue. They waited too long. In a matter of minutes, men of the 310th Infantry were all around them. In three hours they cleared thirty-two pillboxes and took the village of Konzen. Their final objective, the next village to the south, fell the next morning. So swift was the success that the flame-throwing tanks saw little use.

In the center, the tanks of CCA had trouble with mines concealed by deep snow, but by late afternoon they managed to work their way in the wake of the infantry to the fringe of Eicherscheid. With infantrymen close behind them, they roared into the village and began a systematic mop-up just as darkness came.

Only on the extreme left wing of the 311th Infantry, at Kesternich on the road to Einruhr, was the story basically different. There the 2nd Battalion already held a few of the westernmost houses, the sole lasting gain from a bitter fight for the village in December. Yet despite long familiarity with the terrain and the most minute planning, the first companies to enter the main part of the village found control almost impossible. Although the men had studied the location of the houses from a map, they were difficult to recognize. Many were destroyed, some were burning, and the snow hid landmarks. Communications with tankers of the supporting 736th Tank Battalion failed early. Mines accounted

for two tanks, antitank fire two more.6

With the Germans doggedly defending each building, it took two full days to clear the last resistance from Kesternich. Capturing the town might have taken even longer had it not been for a squad leader in Company E, S. Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley. Each time Kelley’s squad assaulted a building, he was the first to enter. Although wounded twice early in the fighting, he refused evacuation. His left hand useless, he continued to fire his rifle by resting it across his left forearm. Late on the second day, Kelley led an assault on a machine gun position. German fire cut him down as he expended the last three rounds from his rifle and knocked out the machine gun.7

In the two-day action, the 311th Infantry lost 224 men, the bulk of them from the 2nd Battalion. Just why Kesternich cost so much became clear as artillery observers found they could direct observed fire from the village on all remaining German positions west of the Roerstausee.

Toward Schmidt

In advance of the pending shift of the First Army’s boundary to the north, the 78th Division on 2 February passed to operational control of the V Corps. That evening the division commander, General Parker, traveled to headquarters of the V Corps to receive from General Huebner the order for the capture of Schmidt and the Schwammenauel Dam. The task, Huebner told Parker, was the most vital at that time on the entire Western Front; until the dam was in hand, the Ninth Army dared not cross the Roer. Added to this glare of the spotlight was the fact that the 78th Division had had only limited battle experience and the fact that the very name of the town of Schmidt had become a kind of bugaboo among American soldiers after the beating another division had taken there in November. All the ingredients for a bad case of the jitters were present at the start.

As General Parker prepared his plan of attack, it was obvious that terrain would narrowly restrict the force that could be applied against Schmidt and the dam. Schmidt lies spread-eagled on the eastern slopes of a high hill mass, in general an east-west ridge with fingers poking out to north, northeast, and south. Adjacent high ground to the north beyond the little Kall River, which in German hands had contributed to failure at Schmidt in November, was controlled by the neighboring XIX Corps.

It would be hard to get at Schmidt along the route from the southwest that the 78th Division had to take. Except for a narrow woods trail from Woffelsbach, close by the Roerstausee, the only feasible approach from this direction is along a lone main road following the crest of the Schmidt ridge. The road passes from the open ground of the Monschau corridor through more than a mile of dense evergreen forest before emerging again into broad fields several hundred yards west of Schmidt, where it climbs Hill 493 before descending into the town. A narrow but militarily important

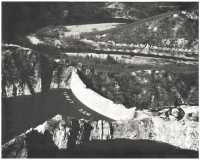

The Urft Dam

feeder road parallels the main road on the north for a few miles before joining the main road at a point where the Germans had constructed a nest of wooden barracks, believed to be strongly fortified.

In addition to normal attachments, the 78th Division was to be reinforced by the reserve combat command of the 7th Armored Division, an engineer combat battalion, fires of V Corps and 7th Armored artillery, and planes of the XIX Tactical Air Command. Jump-off was scheduled for 0300, 5 February.

General Parker intended first to clear the rest of the Monschau corridor and seize a line running inside the woods from the Kall River in the north through the nest of barracks to the Roerstausee. (Map 2) From there the attack was to proceed almost due east along the axis of the main road into Schmidt, thence, while subsidiary drives secured villages north and east of the town, southeast to the Schwammenauel Dam. The 309th Infantry, attacking with its 3rd Battalion from within the Monschau corridor at Rollesbroich, was to make the main effort in the first phase, seizing the barracks at the juncture of the feeder road

The Schwammenauel Dam

and the main highway. Thereupon the 310th Infantry was to pass through and take Schmidt.

The attack began on a bright note, for late in the afternoon of 4 February a company of the 9th Division reached the Urft Dam after little more than a cross-country march. Although American artillery fire had done some damage to outlet tunnels, the big dam still was intact.

The beginning of the 78th Division’s attack went well—unexpectedly well. The 3rd Battalion, 309th Infantry (Lt. Col. Floyd C. Call), got off on time at 0300, 5 February, and in rain-drenched darkness moved cross-country through a web of pillboxes. The infantrymen slipped past at least 35 concrete pillboxes and bunkers from which 135 Germans later emerged; but not a shot disturbed them.

As the battalion advanced through successive checkpoints and the word came back over the field telephones, “No enemy contact,” commanders prepared the next step. It looked like a penetration, but could it be exploited? Engineers and reconnaissance troops moved out to see if the roads were clear, particularly the feeder road north of the main highway, the main axis of the 309th’s

Map 2: The Capture of Schmidt and the Schwammenauel Dam, 5–9 February 1945

advance. Meanwhile, other troops of the division, including attached tanks of the 7th Armored Division’s CCR, prepared to clear the remaining villages in the Monschau corridor.

A little after daylight, General Parker alerted the 310th Infantry for an immediate move through the 309th. Fifteen minutes later Colonel Call reported his battalion “advancing toward the final objective” and meeting small arms fire for the first time.8 Shortly thereafter the infantrymen of the 309th overran the German barracks, catching some men sleeping, others eating breakfast. Movement orders for the 310th Infantry,

meanwhile, had to await inspection of the road. Inevitably, that took time.

During the wait the commanders considered other possibilities. General Parker thought of sending the 309th out farther than originally planned. General Huebner at V Corps contemplated more drastic changes. Before 0830 he ordered the 78th Division to form a task force built around the 311th Infantry to cross the Roer at Ruhrberg over the Paulushof regulating dam, one of the lesser dams in the Roer system, plow through rough, wooded country between the Urftstausee and the Roerstausee, and come upon the Schwammenauel Dam from the south. At the same time the 9th Division was to send a force across the Urft Dam to block forest roads that the Germans might use to move against the 311th Infantry.9 These maneuvers were to take place during the night of 6 February. In the meantime the main effort by the 78th Division against Schmidt was to continue.

Shortly before 0900 on the 5th it became clear that mines and craters for the present ruled out use of either the feeder road or the main highway toward Schmidt. The 310th Infantry, General Parker ordered, was to proceed cross-country without supporting weapons. In two hours the infantrymen were on the march.

Men of the 309th Infantry meanwhile had begun to run into resistance as the Germans awoke to their threat. A company on the right received what was reported to be a counterattack, though it apparently was no more than an aggressive defense by a few German squads. A fire fight took place nevertheless, and in the woods where control is difficult, it checked the advance. The attack, which had flamed so brilliantly, began to show signs of sputtering out.

With so much at stake, commanders grew uneasy. General Parker an hour before noon ordered the 309th Infantry to go as far as possible beyond the barracks and at the same time directed the 310th Infantry not to move into forward assembly areas as planned but to pass immediately through advance units of the 309th Infantry and press the attack. These orders stood less than fifteen minutes; the corps commander, General Huebner, intervened. It seemed to Huebner unsound in the face of seemingly slight resistance to halt the attack while waiting for a new regiment to take over. The 309th, moreover, was the freshest unit in the division. At his instigation, the 309th was to continue to Schmidt, reinforced by its 1st Battalion, heretofore attached to the 310th Infantry. All troops were to advance without supporting weapons until roads could be opened.10

The order was difficult to execute. The 1st Battalion of the 309th in order to rejoin its parent regiment had to pass through two battalions of the 310th that had already begun to move forward. It was two hours before men of this battalion began to pass through and late afternoon before they arrived at the forward positions. The 2nd Battalion had been clearing pillboxes around the barracks and could not assemble immediately to move on to the east. The 3rd Battalion still was mopping up the pillbox belt that had been negotiated so rapidly before dawn by the 2nd Battalion.

As night came, General Parker—apparently

with the concurrence of General Huebner—directed that all units resume their original missions. The 310th Infantry was to pass through the 309th at 0300 the next morning, 6 February.

Both regiments were in low spirits, thoroughly confused by the day of changing orders.11 Men of at least one battalion of the 309th learned that both division and corps commanders were displeased with their performance. The men of the 310th Infantry were tired, wet, and frustrated, and the regimental commander warned that they would be in poor condition for the next day’s attack. The day of 5 February closed on frayed nerves.

While the 311th Infantry had escaped most of the confusion, that regiment’s progress, too, was slow. The order to cross the Roer at Ruhrberg General Huebner canceled in the afternoon when reconnaissance revealed that the Germans had blown a great gap in the roadway over the Paulushof Dam and that the swollen Roer was too deep and swift to ford.

The order never had interrupted operations. One battalion continued to push across cruel terrain north of Ruhrberg, the back way to Schmidt. Although resistance was never resolute, the job of clambering through woods, up and down steep hills, and challenging a succession of pillboxes wore the men out. Yet they took the hamlet of Woffelsbach and thus, by nightfall, were roughly on a line with the 309th Infantry in the main attack.

Since all attempts to speed the main attack had failed and one had backfired in added delays, pressure for quick success increased. General Huebner ordered that the attack on Schmidt itself be made at daylight on 6 February and that the Schwammenauel Dam be taken, if possible, the same day. The First Army commander, General Hodges, was to arrive at the division command post in the morning, which was a military euphemism for “Get cracking, or else!”

At 0300 on 6 February, the 310th Infantry began passing through the lines of the 309th with two battalions in column, but hardly had the men crossed their line of departure when they came under intense grazing fire from automatic weapons. As the men went to ground, commanders temporarily lost control. At daylight, the men rallied, but commanders in the thick woods had no real idea where they were. The day was overcast, and dim light filtering through heavy fir branches scarcely brightened the gloom under the trees. Enemy artillery and mortar fire ranged in. One battalion counted about 200 rounds of mortar fire in half an hour. Apparently unobserved, the shelling caused few casualties, but it was enough to stymie advance. Tanks coming up the road to support the attack drew antitank fire and backed into hull defilade out of contact with the infantry.

In early afternoon the infantry tried a new attack, but it had no punch. Since observers were unable to adjust artillery by sight in the thick woods, artillery preparation was worse than useless, serving only to fell trees and branches in the path of the infantry. Commanders still had only a vague idea of where the men were.

Just before dusk, Company A on the extreme right walked into an ambush.

The Germans allowed the lead platoon to pass through their positions, then opened heavy small arms fire on the company headquarters and two platoons that followed. The incident disorganized the company and produced wild rumors in the rear. Artillery observers reported that the entire right flank was disintegrating; Company A was “cut to pieces.”12 At division headquarters word was that a substantial counterattack was in progress and had achieved a considerable penetration. Seven men from Company A reported at regimental headquarters that they were the sole survivors.

The truth was that there had been no counterattack and no penetration, but defensive fires from what may have been the enemy’s main line of resistance were heavy and damaging. The 310th Infantry commander, Col. Thomas H. Hayes, decided to call off the attack for the night, pulling his advance battalion back to consolidate with another in a night-time defensive position. Seventy-five men of Company A filtered back to join the defense.

As night came, men of the 310th Infantry had little to console them for the day’s sacrifices. Instead of attacking Schmidt, they had barely struggled past the line of departure. Paying the penalty for the confusion and haste of the day before, they had blundered under pressure from higher headquarters into an ill-prepared attack in the darkness through unknown woods against unknown positions and had suffered the consequences that basic training doctrine predicts.

To give the stumbling attack a boost, General Parker on 7 February committed all three of his regiments. The 310th Infantry was to continue along the axis of the main road and take the crest of the high ground, Hill 493, outside Schmidt. The 309th Infantry on the left was to drive northeast through the woods to Kommerscheidt, just north of Schmidt. The 311th Infantry on the right was to push northeast through the woods from Woffelsbach and take Schmidt itself.

Although a half-hour artillery preparation preceded the new attack, it fell on German positions manned at that point only by a small rear guard. Having managed to use the dense woods and American errors to sufficient advantage to make a stiff fight of it for a while, the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division, lacking depth, had fallen back during the night. The 309th Infantry met little opposition until it reached Kommerscheidt. There a heavy concentration of mortar fire sent the men diving into water-filled shellholes and foxholes, relics of the November fighting. Men of the 310th Infantry, accompanied by tanks of the 744th Tank Battalion, walked and occasionally rode along the main road to occupy Hill 493 by midmorning.

In the rough wooded terrain on the right, the 311th Infantry had slower going, but with considerable finesse men of the leading battalion surrounded and knocked out a succession of pillboxes. At small cost to themselves, they gathered in 117 prisoners during the day. Taking advantage of the 310th Infantry’s advance to Hill 493, another battalion of the 311th Infantry with the support of a company of tanks marched down the main road toward Schmidt and arrived at the woods line in time to launch

an attack in early afternoon. With infantrymen riding the tanks, the column prepared to make a dash over the crest of Hill 493 and across a mile of open fields into the town.

Hardly had the lead tank crossed the crest of the hill when armor-piercing shells struck it three times. As the tank burst into flames, the other tanks scurried back to the woods line.

Reorganizing, the infantry set out to do the job alone. Covered by fire from light machine guns, one company plunged across the crest of the hill. Despite persistent German fire, most of the men had by late afternoon gained the westernmost houses in the northern part of the town. Another company tried to come in through a draw south of Schmidt but found the approach covered by fire from automatic weapons. Night was falling as the company gained the first houses. Only at this point did the tanks arrive to help in a house-to-house mop-up of the town.

Toward the Dam

On the same day that the first American troops entered Schmidt, 7 February, a regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division began to attack southward across the corps boundary to cross the deep draw of the Kall River and move cross-country to cut the enemy’s escape route from Schmidt, the road from Schmidt northeast to the Roer at Nideggen. Terrain imposed such limits on the advance that by the time the 311th Infantry got to Schmidt, little hope remained for a sizable prisoner bag. The next day another regiment of the 82nd Airborne crossed the Kall gorge and relieved the 309th Infantry in Kommerscheidt so that the 309th could participate in the final thrust on the Schwammenauel Dam.

General Parker’s plan for the final thrust called for the 310th Infantry to pass through Schmidt early on 8 February and drive east and southeast along the highway to Hasenfeld at the foot of the dam. As soon as the 310th had advanced far enough along this road to uncover a line of departure for an attack southward against the dam, the 309th Infantry was to follow and move cross-country to take the dam.

If this plan was to be executed swiftly, Schmidt had to be fully in hand, a condition General Parker believed already met. On 8 February the men of the 310th Infantry discovered otherwise. Many of the houses, particularly those along the road to Hasenfeld, remained to be cleared, and the Germans yielded none without a fight. Noontime came and went, and the 310th still was battling to get past the last houses and into the open.

The First Army commander, General Hodges, made no effort to hide his dissatisfaction with the pace of the attack. The target date for the Ninth Army’s offensive across the lower reaches of the Roer, 10 February, was little more than a day away; but not until the 78th took the dam could the Ninth Army move. The First Army artillery commander, Brig. Gen. Charles E. Hart, had seen to it that 40 battalions of artillery (780 guns) could be called upon to help the attack; General Hodges found it hard to understand why with this amount of artillery they could not “blast a road from our present front line positions straight to the dam.”13

Shortly before noon on 8 February, General Hodges telephoned the V Corps commander, General Huebner, to express again his dissatisfaction. A few minutes later the commander of the 9th Division, General Craig, walked into the V Corps headquarters on a routine visit. How long, Huebner asked Craig, would it take to shift a combat team of the 9th Division to Schmidt to attack the dam? Craig said he could do it “immediately.” Huebner told him to move not only a combat team but also the division headquarters. When Craig arrived in Schmidt, the 78th Division’s 309th and 311th Regiments were to be attached to the 9th Division.14

Placing a telephone call to his division command post, General Craig urged such speed in the movement that first units of his division already were en route to Schmidt before he himself got back to his command post. Turning over its sector to the 2nd Division, the 60th Infantry led the way. A second regiment followed as a reserve, while the third regiment remained behind under attachment to the 2nd Division. By midnight men of the 9th were in Schmidt getting set to attack before daybreak the next morning.

General Craig directed the 311th Infantry to clear wooded high ground along the north and northeast banks of the Roerstausee while the 60th Infantry took over the drive to Hasenfeld. The 309th Infantry remained on alert to move against the dam itself.

Despite the introduction of a new commander and a veteran unit, the going on 9 February again was slow. Not until late afternoon did either the 60th Infantry on the road to Hasenfeld or the 311th Infantry along the northeast bank of the reservoir advance far enough to enable the 309th Infantry to begin its attack against the dam. It was 1800—after nightfall in this period of short winter days—when the leading 1st Battalion, 309th, passed through the 311th Infantry and headed for the dam.

Groping through the darkness, the 1st Battalion upon approaching the dam split into two groups, one to gain the top of the dam and cross over, the other to reach the lower level and take the power house. Those men moving against the lower level were particularly apprehensive lest the Germans at any moment blow the dam, sending tons of concrete, earth, and water cascading down upon them.

With the upper group was a team from the 303rd Engineer Battalion, specially briefed on the nature of the big dam. The engineers pressed forward at 2300 to begin a search for demolitions. German fire at first forced them back, but by midnight they were at last able to start.

The engineers intended to cross the dam to the spillway and there descend into an inspection tunnel that intelligence reports stated ran through the dam. Crouched low against continuing German rifle fire, the men raced across but found a portion of the spillway blown and access to the tunnel denied. There was only one other way, to slide down the 200-foot face of the dam and gain the tunnel through its bottom exit.

Although the task was slow and treacherous, the engineers accomplished

Damage to the Schwammenauel dam causes flooding of the Roer River

it. Entering the tunnel, they expected at any moment to be blown to kingdom come. The explosion never came. Subsequent investigation revealed that the Germans already had done all the damage intended. They had destroyed the machinery in the power room and had blown the discharge valves. They had also destroyed the discharge valves on a penstock that carried water from the upper reservoir on the Urft to a point of discharge below the Schwammenauel Dam, which explained why they had allowed the Urft Dam itself to fall into American hands intact. Together the two demolitions would release no major cascade of water but a steady flow calculated to create a long-lasting flood in the valley of the Roer.15

Allied commanders could breathe easily again. The reservoirs that directly and indirectly had cost so many lives at last were in hand. It would have been better, of course, had the Schwammenauel Dam been taken intact, thus

obviating any change in the Ninth Army’s plan for crossing the Roer; but it was enough that the Germans had been forced to expend their weapon before any Allied troops had crossed the river downstream.

In the end the success belonged basically to the 78th Division. For all the dissatisfaction with the pace of the attack, this relatively inexperienced division had driven through rugged terrain over a severely canalized approach. Dense forest had nullified much of the artillery’s power, as weather did for air support. Too many cooks had appeared from time to time to meddle in the tactical broth, but once the pressure was off and the division’s role could be assessed with some perspective, General Huebner could remark to General Hodges that he had “made him another good division.”16