Chapter 14: Approaching the Gaps: Saverne

Despite Truscott’s success in forcing the Moselle, the natural and man-made obstacles between the 6th Army Group and the German border were formidable. For this reason Devers was not nearly as confident as Truscott that the Vosges could be easily forced. Facing the German Nineteenth Army in mid-September, the 6th Army Group had only six divisions on line—Truscott’s three American infantry divisions and the equivalent of three French divisions under de Lattre’s control, all that he had been able to bring up from the south so far. Like the divisions in the two northern Allied army groups, these forces were overextended logistically, while the real battle for Germany had just begun. Without substantial reinforcements, it was doubtful that the 6th Army Group could play a major role in this struggle.

Regarding a sustained offensive over the Vosges with serious misgivings, both Devers and Patch considered alternate routes to the German border. The Vosges barrier could be bypassed in the north through Saverne or in the south at Belfort. The Saverne Gap was a generally narrow defile that separated the High Vosges from the Low Vosges, a somewhat lesser range that angled off to the east into Germany, where it became known as the Hardt Mountains. The much wider Belfort Gap separated the High Vosges from the Jura Mountains and the Swiss Alps. But Truscott’s initial drive for the Belfort Gap had fallen short in early September, and Patton’s Third Army had been stopped at Metz many miles west of Saverne and the Sarre River valley to the north. Since then the German defenses in both areas had grown stronger, as de Lattre’s French and Patton’s American units soon discovered. Until the First French Army could put most of its seven divisions on line, the Belfort Gap would be difficult to force, and the more narrow Saverne Gap lay in the zone of the Third Army’s XV Corps above Rambervillers and Baccarat. Devers thus had no choice but to send Truscott’s weary forces into the mountains. At the very least the effort might weaken the German defenses in the gap areas, and, if employed carefully, the better-equipped and better-supported American infantry might wear the hastily assembled German “grenadiers” thin. Nevertheless, a battle of attrition in the mountains was not a mission that the American commanders or their troops relished, and Devers and Patch continued to study the possibility

of bypassing the Vosges Mountains to the north through the Saverne Gap.

Allied Planning

By late September, Allied offensive activities throughout the northern European theater had ground to a halt. Montgomery’s drive against the Ruhr had been stopped at Arnhem, and Patton’s drive on the Saar had been halted in Lorraine. Both northern Allied army groups had outrun their supply lines, and the 6th Army Group was not in much better shape.1 Other factors contributing to the general slowdown were poor weather, which complicated both tactical and logistical problems, and increasingly determined German resistance. In Eisenhower’s mind the only real solution to the logistical problem was an early opening of the port of Antwerp in Belgium. Yet he had postponed concerted action to open Antwerp in favor of MARKET-GARDEN, the 17–24 September attempt to envelop the Ruhr industrial area from the north. But the support demands of the operation only made the already serious logistical situation of the two northern Allied army groups worse.

On the afternoon of 22 September, with the success of MARKET-GARDEN already in doubt, Eisenhower met with his major subordinate commanders, including Generals Devers and Patch, to consider new plans. For the immediate future, Eisenhower told his subordinates, the logistical situation as well as tactical considerations would continue to make it impossible to implement a broad front strategy. Instead, the main Allied effort would have to remain in the north, in the sector of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. There, he pointed out, the principal Allied objective was clearing the seaward approaches to Antwerp. But Eisenhower also agreed to allow the 21st Army Group’s offensive to continue against the Ruhr. The Ruhr effort, in turn, would still require the direct support of a companion offensive by the U.S. First Army, on the 12th Army Group’s left, or northern, wing; and the logistical support needed for the entire offensive meant that the rest of Bradley’s forces, mainly Patton’s Third Army, would have to remain in place. The same restrictions would apply as well to the U.S. Ninth Army, which on 29 September began moving eastward from Brittany to take over a sector between the First and Third Armies in the middle of the 12th Army Group.

As for the 6th Army Group, the 22 September conference specified that Devers, with his separate line of communications north from the Mediterranean, could continue his offensive toward Strasbourg as well as his efforts to push through the Belfort Gap. Although Eisenhower still considered that the 6th Army Group’s primary mission was to protect the 12th Army Group’s southern flank, the conferees recognized that a rapid Seventh Army drive to Strasbourg on the Rhine would best satisfy that requirement.

During the conference Devers reiterated

his request for another U.S. corps for the Seventh Army and specifically asked for the Third Army’s two-division XV Corps, which was operating just north of the 6th Army Group and opposite the Saverne Gap. Noting that his army group could easily support both the XV Corps and at least one more division for that corps, over its existing line of communications from the south, he pointed out that such a transfer of logistical responsibility would considerably ease the burden on Eisenhower’s northern supply system and would also allow Bradley to narrow the 12th Army Group’s wide front.

At the time, Devers’ proposals were especially appealing to the harried SHAEF tactical and logistical planners. Thus, after some consideration of alternatives, Eisenhower, on 26 September, decided to transfer the XV Corps to the 6th Army Group on the 29th and to add a third division to the corps sometime in October. He also decided that three more American divisions, which had been scheduled to join the 12th Army Group after landing in northern France, were to be diverted to Marseille for the 6th Army Group. All told, six divisions either in or scheduled to join Bradley’s 12th Army Group would be transferred to the 6th Army Group during September and October. However, Eisenhower informed Devers that these would be the last transfers of this nature, and he apparently did not expect them to change the role of the 6th Army Group in future Allied operations.2

Although General Bradley could hardly view the loss of six divisions to the 6th Army Group with pleasure, he saw the logistical advantages involved in the immediate transfer of the XV Corps to Devers’ command. Patton, however, was less complacent and, upon learning of the negotiations regarding his corps, told Bradley that “if Jake Devers gets the XV Corps, I hope his plan goes sour.”3 When the transfer was formally announced, Patton wrote “May God rot his guts” in his diary. But the armored commander’s colorful remarks often obscured his more serious side. Patton was obviously content to let the 6th Army Group’s infantry handle the fighting in the Vosges and was more concerned over the decision to halt the forward motion of his own army in favor of continuing Montgomery’s offensive in the north.

A Change in Command

On 29 September 1944, control of the XV Corps officially passed to the 6th Army Group and the Seventh Army. Patch thus gained a second corps with a total effective strength of approximately 50,500 troops. The main maneuver elements were the 79th Infantry Division, with about 17,390 troops including attachments; the French 2nd Armored Division, with roughly 15,435 troops including attachments; and the 106th Cavalry

Group, consisting of the 106th and 121st Cavalry Squadrons and the 813th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Corps troops, exclusive of the two divisions and their attachments, numbered around 17,680. More important, the principal commanders in the XV Corps had earned excellent reputations in the fighting from Normandy to the Moselle. The XV Corps commander, General Haislip, and the commander of the 79th Division, Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche, had both done well under Patton’s demanding eyes; and the head of the French 2nd Armored Division, Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc,4 was considered by most American leaders to be one of the finest tank commanders in the Allied army. Haislip, a West Point contemporary of both Patton and Patch, had commanded the XV Corps since February 1943, bringing it through the Desert Training Center in the southwestern United States and then, via Northern Ireland and England, to Normandy and through northern France. In the process he had put together a corps staff and supporting organization that would rival Truscott’s VI Corps in excellence. Another plus was Haislip’s close relationship with the sometimes difficult Leclerc, who was a close associate of de Gaulle and a long-time veteran of the Free French military forces. Although the French armored division commander’s temper rivaled that of de Lattre, his experience and expertise would prove invaluable in the coming battles.

The acquisition, despite General Devers’ enthusiasm and optimism, was not without its problems. Like the VI

Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip

Corps, the XV Corps was exhausted, and its logistical situation was even worse than that of de Lattre’s French units in the south. After over one hundred days of combat and pursuit, the infantry units of the 79th Division were tired, and the division was short many items of supply and equipment. All three infantry regiments were well below their authorized strength of 3,348: the 313th by about 575 troops, the 314th by 360, and 315th by 600. The division’s artillery battalions were short of well-trained personnel and ammunition as well. After visiting the 79th, General Devers estimated that Wyche’s command needed at least two weeks out of the line for rest and replenishment of both personnel and

supplies.5 For the moment, however, the unit could not be withdrawn from its current operation.

The 2nd French Armored Division was hardly in better shape. Reviewing the division’s status on 28 September, General Leclerc pointed out that the division was operating largely with equipment issued in North Africa over a year ago.6 The division’s 4,000-odd vehicles were in need of thorough overhaul, without which maintenance problems would soon become unmanageable. Moreover, much of the nearly twenty-mile front that the division was currently holding north of Rambervillers was rough, wooded, and ill-suited to armored operations, especially in wet weather. Such terrain, Leclerc pointed out, required strong infantry forces; his unit, organized along the standard lines of a U.S. armored division, had only the three armored infantry battalions and could not be expected to hold the same frontage that an infantry division with nine infantry battalions could. In addition, the division’s armored infantry companies were down to about eighty effectives, approximately one-third of their authorized strength. Leclerc therefore requested that his defensive sector be reduced as soon as possible.

Although Haislip accepted Leclerc’s evaluation, neither he nor Patch had any infantry to spare. The 79th Infantry was fully occupied in the northern sector of the XV Corps’ front, and all of Truscott’s infantry was committed in the Vosges. He could only hope that German inactivity would allow Leclerc to pull his units out of the line, one by one, for rest and maintenance.

Meanwhile, Haislip struggled to remedy his own logistical problems. Beginning on 29 September, the Seventh Army started to provide the XV Corps with some supplies, notably gasoline and ammunition, which alleviated the corps’ most urgent requirements. Despite Devers’ promises, however, it was not until the third week of October that rail deliveries at the Seventh Army’s main supply centers, established in and around Epinal, were able to meet all the army’s needs, including those of the XV Corps.

With the transfer, the 6th Army Group also became responsible for carrying out tactical missions already assigned to Haislip’s corps. Devers and Patch clearly understood that these missions included securing the Lunéville area and continuing to protect the right, or southern, flank of the Third Army—both of which required the XV Corps’ 79th Division to continue clearing the area east of Lunéville. Furthermore, supplementary Seventh Army orders specified that Haislip’s corps was ultimately to seize Sarrebourg, about twenty-seven miles beyond Lunéville and some ten miles short of the Saverne Gap, and in its southern sector, to assist VI Corps units in capturing and securing Rambervillers. For these operations the boundaries of the XV Corps were virtually unchanged. In the north, its border with the Third Army’s XII Corps followed the southern bank of the Rhine–Marne Canal to Heming,

General Leclerc (in jeep) and staff at Rambouillet

and from there continued northeast along Route N-4 to Sarrebourg; in the south its boundary with Truscott’s VI Corps followed a line between Rambervillers and Baccarat. Within these confines Haislip would fight his most notable battles during the coming months.7

VI Corps Attacks (26–30 September)

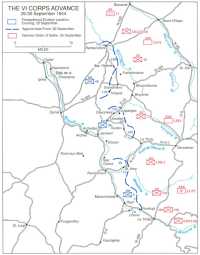

On 26 September Truscott resumed the VI Corps’ drive to the northeast, with the 45th Division on the left pushing out of its bridgehead at Epinal (Map 16). At the time, the division’s sector closely corresponded to the area defended by the German LXVI Corps, and, in fact, the effective combat strength of the defending corps was about the same as the attacking American division. But with the German defenders pulling back on Wiese’s orders and with the terrain being generally open and rolling farmland, the 45th had little trouble advancing. The 157th regiment, with elements of the XV Corps’ French 2nd Armored Division on its left, covered the fifteen miles to Rambervillers by the 29th against scattered resistance and found that the Germans were beginning to pull back even farther east toward Baccarat. South of the 157th, the 45th Division’s 180th and 179th Infantry had a tougher time, especially in the slopes and woods west of Bruyères, but managed to reach the

Map 16: The VI Corps Advance, 26–30 September 1944

Ste. Hélène–Vimenil area by the 29th abreast of one another. The month thus ended with all three of the 45th Division’s regiments on a north-south line below Rambervillers facing the Vosges Mountains.

In the middle and southern sectors of the VI Corps’ offensive, the progress of the 36th and 3rd Divisions through the Vosges foothills was much slower. Aiming directly for Bruyères, the 36th Division’s 143rd Infantry took two days to break through units of the 716th Division defending the area west of Tendon, while the 142nd, with the 141st securing its right flank, did little better against elements of the 198th Division to the south. On the 27th the 142nd managed to advance over the Tendon–Le Tholy road, Route D-11, the main lateral German communications line in the region; and on the 28th the 141st regiment, relieved of its flank security mission by units of the 3rd Division, moved in between the 143rd and 142nd regiments at Tendon for a concerted push on Bruyères. But the prognosis for a rapid breakthrough was poor. The terrain was now channeling the 36th Division’s upward advance into narrow, easily defensible corridors where the Germans were attempting to concentrate their defensive strength.

South of the 36th, the 3rd Division found itself in a similar situation. There O’Daniel had finally brought the 30th regiment as far as Rupt on the Moselle, allowing the 15th and 7th to begin moving into the Vosges east of the river on 27 September, but leaving the area south of Rupt under German control. Once inside the Vosges, the experienced 3rd Division infantrymen also found the going tough. Although the attacking units tried to bypass German defenses on the roads to Gerardmer by side-stepping behind the 141st regiment in the St. Ame region and striking northeast toward Le Tholy, the results were the same. Thus by the end of September Truscott’s forces in the north had easily reached Phase Line IV, but those in the center and south, the units that had actually begun moving into the mountains, were hardly beyond Phase Line II. Obviously a quick thrust over the Vosges was unlikely, and Devers and Patch became even more convinced that their strength might be better used reducing the German defenses in the Saverne Gap area north of the High Vosges.

XV Corps Before the Saverne Gap (25–30 September)

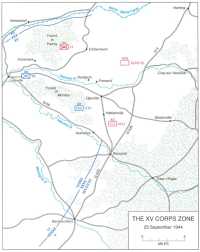

By 25 September General Patton, the Third Army commander, had already set in motion a XV Corps operation that was to continue well after the corps had been transferred to the 6th Army Group. News that the Third Army would have to go on the defensive had aroused Patton’s innate opportunism, and he had prevailed upon General Bradley to permit the Third Army to undertake some “local” operations to straighten out his lines, securing better defensive terrain and better positions from which to launch future Third Army offensives. In this process, Patton wanted Haislip’s XV Corps to expand its control of Lunéville, a railroad and highway hub close to the confluence of the Meurthe and Vezouse rivers and some eighteen miles north of Rambervillers (Map 17).

Although elements of the Third Army’s XII Corps had first entered

Map 17: The XV Corps Zone, 25 September 1944

Lunéville on 16 September, they had been unable to clear the city completely by the 20th when Haislip’s XV Corps took over the sector. Haislip immediately tasked Wyche’s 79th Division with rooting out the last German defenders and securing two thickly wooded areas to the east, the Parroy and Mondon forests. The two forests flanked the main roads to Sarrebourg, providing cover and concealment for German forces guarding the approaches to the Saverne Gap, and would have to be cleared before the XV Corps could move farther east.

While the 79th Division’s 315th regiment mopped up the Lunéville area, Wyche’s other two regiments, the 313th and 314th Infantry, moved into the Mondon forest, sweeping through most of the woods by 23 September. Then, while Leclerc’s French units finished policing the light German resistance at the southern edge of the forest, all three 79th Division infantry regiments moved up to forward assembly areas on the southern bank of the Vezouse River and prepared to move into the Parroy forest on the 25th.8

The German Situation in the Lunéville Sector

As the 79th Division massed on the Vezouse River, General Balck, the Army Group G commander, was facing a rapidly deteriorating situation.9 On his northern wing, from Luxembourg to Vic-sur-Seille, fourteen miles north of Lunéville, Army Group G’s First Army was heavily engaged across most of its 75-mile-wide front. Along Army Group G’s center, the Fifth Panzer Army, with a thirty-mile front from Vic-sur-Seille to Rambervillers, had been roughly handled by Patton’s Third Army and was currently capable of little more than defending in place. South of Rambervillers, the Nineteenth Army continued to occupy its ninety-mile front to the Swiss border, but was having increasing problems holding back the 6th Army Group as the Seventh and First French Armies brought more of their forces into the front lines. However, for Balck, a penetration of Army Group G’s center presented the gravest danger: a drive through the Saverne Gap could split his armies, isolating the forces in the High Vosges; a drive north of Saverne into the Saar industrial basin would have about the same military effect but would also severely damage Germany’s strategic war-making capabilities. From his perspective then, Truscott’s advance into the Vosges or de Lattre’s demonstrations outside of the Belfort Gap were relatively unimportant.

Balck viewed the center of his defensive line with great concern. The Rhine–Marne Canal, running east and west about six miles north of Lunéville and just off the northern edge of the Forest of Parroy, divided the Fifth Panzer Army’s sector into two parts: LVIII Panzer Corps operating north of the canal and XLVII Panzer Corps to

the south. (The canal also marked the boundary between the Third Army’s XII and XV Corps.) Since 12 September the Fifth Panzer Army, under General von Manteuffel, had been engaged in a series of costly armored counterattacks against the Third Army’s right flank. Although these operations had slowed Patton’s advance, they had also virtually decimated the armor available to von Manteuffel. As of 25 September both the Fifth Panzer Army and its two corps were panzer in name only. At the time, the LVIII Panzer Corps was continuing its fruitless counterattacks against the XII Corps, but the XLVII Panzer Corps had abandoned its attempts to recapture Lunéville on the 23rd, apparently when General Balck learned from OKW that the 108th Panzer Brigade, until then slated for commitment in the Lunéville sector, was to be transferred farther north. This unexpected loss of armor may have also influenced the German decision to abandon the Forest of Mondon and to withdraw the XLVII Panzer Corps’ right flank north across the Vezouse River.

The new line that Lt. Gen. Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, commanding the XLVII Panzer Corps, was to hold originated at Henamenil, on the Rhine–Marne Canal about six miles northeast of Lunéville, passed south across the western face of the Forest of Parroy to the north bank of the Vezouse near Croismare, and then ran southeast along the Vezouse about seven miles to the vicinity of Fremenil. Here the defenses—which were hasty in nature—crossed back over the Vezouse and followed a ridge line south past Ogeviller and Hablainville for about seven miles to Baccarat. The corps also maintained a salient at Azerailles, three miles northwest of Baccarat, to block Route N-59, leading southeast from Lunéville. For the moment Balck and von Manteuffel decided to leave the defensive dispositions of the Fifth Panzer Army unchanged in the south, from Baccarat to Rambervillers, but both commanders remained concerned about the possibility of a VI Corps drive on the Saverne Gap from the vicinity of Rambervillers.10

Defending the new line from the Rhine–Marne Canal to Fremenil was the responsibility of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The rest of von Lüttwitz’s sector was held by the virtually tankless 21st Panzer Division; Group Oelsner, a provisional infantry regiment; and part of the 113th Panzer Brigade. Some troops of the 16th Division were also in the XLVII Panzer Corps’ area, while in reserve was the 112th Panzer Brigade, reduced to less than ten tanks.11 In case of a dire emergency, General von Lüttwitz could call on several fortress battalions digging in along forward Weststellung positions about fifteen miles east of Lunéville.

Understrength to begin with, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division also

lacked some of its organic units.12 For example, a regimental headquarters, a panzer grenadier battalion, an antitank company, and a battery of artillery were deployed well to the north with the First Army, while a battalion of artillery and a tank company were operating north of the Rhine–Marne Canal with the LVIII Panzer Corps. Shortages were especially acute in the infantry (panzer grenadier) elements, where most battalions had fewer than 350 troops, less than half their authorized strength. On the other hand, von Lüttwitz had been able to beef up the division with several provisional forces—units with limited offensive capabilities, but adequate for defense. In the Parroy forest the division had deployed the 1st and 3rd Battalions, of its 104th Panzer Grenadier Regament; Blocking Detachment Berkenhoff, an infantry battalion largely made up of Luftwaffe personnel; seven to ten tanks or self-propelled assault guns; and more mortars, artillery, and antitank pieces. Additional artillery emplaced on rising ground east of the woods had likely targets within the forest carefully registered. Effective German infantry strength in the forest was initially about 1,200, with total troop strength probably less than 2,000.

The Forest of Parroy

Well before the XII Corps entered Lunéville on 16 September, the Fifth Panzer Army had established bases and depots deep in the Forest of Parroy, using its cover as an assembly area for troops and armor mounting counterattacks against the Third Army’s right flank. Subsequently, the forest had served the same purpose during German attempts to recapture Lunéville, and German artillery hidden in the forest had continued to harass XV Corps’ positions and lines of communication in the Lunéville area. Von Lüttwitz knew he would have to make a stand in the forest, not only to hold back American progress toward the Weststellung and the Saverne Gap, but also to protect the southern flank of the LVIII Panzer Corps as the latter continued its armored counterattacks in the sector north of the Rhine–Marne Canal.

Roughly ovoid in shape, the Forest of Parroy extends about six miles west to east and over four miles north to south, covering an area of nearly thirty square miles (Map 18). Much of the forest area is flat, but thickly wooded with mostly secondary growth of hardwoods, a few stands of older, bigger timber, and an occasional patch of conifers. Unlike most European forests, the Parroy was also characterized by a thick undergrowth that drastically limited observation and visibility. One third-class east-west route, the Haut de la Fait Road, passed through the center of the forest where it bisected the equally poor north-south Bossupre Road. In addition, the forest was crisscrossed with fire lanes, logging tracks, and beds of abandoned narrow-gauge railroads of World War I vintage, most of which could accommodate armored vehicles, but on a strictly one-way basis. Other features included deteriorated trenches and minor defensive installations dating back to World

Map 18: 79th Infantry Division in the Parroy Forest, 25 September–9 October 1944

War I. To these the defenders had added mines, barbed wire, road and trail blocks, new trenches, and timber-roofed dugouts; while the poor September weather produced cold and often torrential rains, fog and mist, mud, and swampy spots—all of which made the Forest of Parroy an unpleasant place in which to travel, let alone fight a pitched battle.

In the fluid combat conditions that had existed earlier in September 1944, the bulk of XV Corps might well have bypassed the Forest of Parroy, leaving follow-up forces to surround, isolate, and clear any Germans that remained. But with the limits imposed on offensive operations, General Patton decided to secure the area by force in order to acquire better positions for subsequent XV Corps attacks. If undisturbed, German infantry, artillery, and armor in the forest could control the main highway (N-4) leading to Sarrebourg and the Saverne Gap, severely hampering a rapid advance eastward.

General Wyche, with Haislip’s approval, had originally planned a frontal attack from the west combined with a single envelopment on the east side of the forest. After meeting little German opposition in the Mondon forest, the two commanders expected the same here, hoping that the 106th Cavalry Group and one infantry regiment of the 79th Division could sweep through the forest, while an armored task force of the French 2nd Armored

Parroy Forest

Division struck northeast across the Vezouse River to isolate the woods on the east. The operation was to begin on 25 September after heavy Allied air strikes.

From the start, little went according to plan. Poor flying weather forced postponement of the air strikes, and Wyche was unable to start his attack until the 25th. In the interim, Leclerc had sent a small force over the Vezouse, but German artillery fire broke up the French infantry formations and the soggy ground confined the French armor to the roads, leading Leclerc to pull his units south, back across the river, before the 79th Division had even begun its assault into the forest.

Continued inclement weather caused Wyche to postpone air and ground attacks on the 26th and 27th, and finally Haislip decided to relieve Leclerc’s division of its part of the operation and leave the entire task to Wyche. Meanwhile, American patrols into the forest had discovered that the Germans were preparing to defend the woods in strength. Accordingly, Wyche revised his plans, deciding to send two infantry regiments into the forest from the west while the cavalry group screened the area to the north along the Rhine–Marne Canal. Abandoning the whole concept of isolating the forest on the

east, both Haislip and Wyche probably felt that a less complex approach—concentrating their superior artillery and infantry resources in one sector—was the best solution considering the terrain and weather.

The American attack into the Parroy forest finally began on 28 September, one day before the XV Corps was to pass to 6th Army Group control. The air attack began at 1400 followed by the ground assault of the 313th and 315th Infantry at 1630 that afternoon. However, of the 288 bombers and fighter-bombers scheduled to participate in the preparatory strikes, only 37 actually arrived, again because of poor flying conditions; and the results of the 37-plane attack against a target covering some thirty square miles were negligible. In addition, the two-hour interval between the last air strikes and the beginning of the 79th Division’s ground attack gave the Germans ample time to recover from whatever shock effect the limited bombardment may have had. As a result the 79th Division infantrymen found themselves locked in a bitter struggle with the German defenders as soon as they began to penetrate the forest.

Even as the 79th Division began its attack, General Balck was again reassessing the situation in the area. North of the Rhine–Marne Canal the LVIII Panzer Corps’ counterattacks had ground to a halt with more heavy losses in German armor and infantry. With no reinforcements, Balck instructed the Fifth Panzer Army to go on the defensive all across its front. To protect the Saverne Gap, he regarded both the Forest of Parroy and the Rambervillers sector as critical. Believing the latter to be more vulnerable, however, he instructed von Manteuffel and Wiese on the 29th to give defensive priority to the Rambervillers area, where the French 2nd Armored Division and the VI Corps’ 45th Infantry Division threatened the boundary between the two armies. To assist von Manteuffel in this task, he moved the boundary of the Fifth Panzer Army eleven miles south of Rambervillers, making the XLVII Panzer Corps responsible for the area. Von Manteuffel, in turn, moved his internal corps boundary south, allowing the LVIII Panzer Corps, under Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, to direct the defense of the Parroy forest, while the XLVII Panzer Corps concentrated its efforts in the Rambervillers–Baccarat region.

Simultaneously Balck and von Manteuffel reorganized the Fifth Panzer Army in order to simplify command and control problems, consolidating battered units and strengthening existing divisions. In the process, the 11th Panzer Division absorbed what was left of the 111th Panzer Brigade; the 21st Panzer Division took over the 112th Panzer Brigade (less a battalion of the 112th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which went to the 16th Infantry Division); and the hard-hit 113th Panzer Brigade was incorporated into the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. This left Army Group G with only one panzer brigade in reserve, the 106th, which had not yet arrived from the First Army’s area, and Balck and von Manteuffel made tentative plans to commit this brigade in the Rambervillers area.

Balck ended the month of September by admonishing his three army commanders not to surrender any

ground “voluntarily.” Every penetration of the forward lines was to be restored by an immediate counterattack. Too often, Balck informed them, reserve forces had been frittered away by premature commitments to weak points and to sections of the front only presumably threatened. In the future, all withdrawals would need his personal approval and would only be authorized if they improved current defensive positions. The Hitler order still stood—to hold west of the Weststellung in order to allow completion and garrisoning of fortifications there. The defense of the Parroy forest would represent the first test of Balck’s orders.

The Forest and the Fight

During these deliberations the U.S. 79th Division and the German 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had been battling throughout the western section of the Parroy forest. The 79th had attacked from the west with two regiments abreast—the 315th Infantry north of the Fait Road and the 313th Infantry to the south. Both regiments made painfully slow progress against determined German resistance, and, by evening on the 30th, the attacking infantry had penetrated scarcely over a mile into the dense forest. During this period the fighting quickly fell into a pattern that continued throughout the battle. Abandoning any attempt at a linear defense, the Germans maintained a thin screening line opposite the Allied advance and concentrated their troops at various strongpoints. By day, German forward artillery observers, hidden in prepared positions, called down predetermined artillery or mortar barrages on advancing American troops; and the concentrations were often followed by small infantry-armored counterattacks moving at an oblique angle down one of the firebreaks or dirt tracks. During the night, smaller German infantry patrols attempted to infiltrate the flanks and rear of the attacking American forces, disorganizing them and interfering with resupply efforts. Often when one American unit was forced back, the others stopped their forward progress to avoid exposing their flanks to further German attacks. Poor visibility in the forest compounded American command and control problems, and the frequent German counterattacks put the attackers on the defensive much of the time. Again and again disorganized American units were forced to fall back, reorganize, and launch counterattacks of their own to regain lost ground.

On 1 October both sides sent reinforcements into the battle. The LVIII Panzer Corps deployed two battalions of the 113th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, 113th Panzer Brigade, into the forest accompanied by additional armor. On the American side, Wyche sent his third infantry regiment, the 314th, into the fray. The division commander wanted the 314th Infantry to move into the forest from the south, just east of the main penetration, and push against the flank of the defenders facing the 313th Infantry, allowing that regiment to drop back in a reserve role.

Although well executed, the maneuver did not seem to shake loose the German defenses. The 79th Division’s progress remained painfully slow and

it was not until 3 October that the last battalion of the 313th Infantry was relieved. On the same day the Germans once again reinforced their troops in the forest, this time with the 2nd Battalion of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, and a few more tanks and self-propelled guns. Wyche, meanwhile, with Haislip’s approval, shortened the front line of the 315th Infantry by making the 106th Cavalry Group responsible for the northern part of the American advance and allowing the 315th to concentrate its forces just above the Fait Road. Between 4 and 6 October, American infantry units renewed their attacks, pushing eastward through the middle of the forest and overrunning several German strongpoints near the juncture of the Fait and Bossupre roads. The Germans then counterattacked with the understrength 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion (from the 11th Panzer Division), forcing elements of the 315th Infantry back from the crossroads. But elsewhere the Americans held their ground. Temporarily exhausted, both sides spent 7 and 8 October patrolling, reorganizing, and resupplying their forces and, in the American camp, preparing to resume the offensive on the morning of the 9th.

The new attack began with a diversionary demonstration at daybreak by the 1st Battalion, 313th Infantry, reinforced with tanks, south of the forest. Evidently, the ruse met with some success, for the Germans shelled the roads along the Vezouse throughout the morning and provided little direct fire support to their troops in the Parroy forest. There XV Corps and 79th Division artillery laid down the heaviest preparatory barrage of the entire operation, clearing the way for the main attack which began at 0650, with ample artillery support on call. Initially two battalions of the 315th Infantry drove eastward north of the Fait Road, while the 3rd Battalion, 315th Infantry, and the 2nd Battalion, 314th Infantry, concentrated against the German strongpoint at the central crossroads, finally overrunning that position about 1800. Meanwhile, two battalions of the 313th Infantry moved into the line south of the 2nd Battalion, 314th Infantry, and pushed eastward south of the crossroads; still farther south the rest of the 314th Infantry aggressively patrolled through the southern third of the forest. At dusk the 79th Division’s center had advanced only a mile and a half beyond the central crossroads, but the infantry commanders hopefully noted that German resistance was beginning to diminish.

During the evening of 9 October Krueger outlined the status of his forces to von Manteuffel and reported that he was unable to restore the situation with the forces available. The loss of the interior roads and the central strongpoints made further defensive efforts costly, especially if the Americans began to threaten the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division’s routes of withdrawal. The only uncommitted forces were two battalions (with an aggregate strength of about 550 troops) of the division’s 115th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and two fortress battalions,13 but using these units would deprive the defenders of their

last reserves and leave no maneuver units for operations east of the forest. Accordingly, the LVIII Panzer Corps commander requested permission to withdraw from the Parroy forest to a new defensive line, and the Fifth Panzer Army and Army Group G had no choice but to approve the request.

Except for some rear-guard detachments, the main body of German troops in the forest withdrew during the night of 9–10 October to a new defensive line several miles east of the woods, tying in with the XLVII Panzer Corps’ 21st Panzer Division at Domjevin, with the inter-corps boundary later moving a few miles south to Ogeviller. German losses during the fight for the Forest of Parroy, 28 September through 9 October, numbered approximately 125 men killed, 350 wounded, over 700 missing (most of them taken prisoner), and about 50 evacuated for various sicknesses.14 More significant, however, they had now lost their principal forward defensive position along the approaches to the Saverne Gap.

More Reorganizations

During 11 and 12 October, the 79th Division and the 106th Cavalry Group cleared the remainder of the forest and pushed on to the new German defensive lines to the east. A final advance by all the 79th’s regiments on the 13th managed to secure Embermenil, in the center of the German line, but elsewhere the division made only limited progress in the face of heavy German artillery and mortar fire and flooded ground. Thereafter the dispositions of the division remained essentially unchanged.

The subsequent inactivity of the XV Corps was due in part to the redeployment of many Third Army support units, which had to be returned by the 15th. At the request of General Devers, Bradley agreed to allow Haislip to retain two heavy field artillery battalions, but the XV Corps lost four field artillery battalions, four antiaircraft gun battalions, a three-battalion engineer combat group, a tank destroyer battalion, and some lesser units, forcing Haislip to pause while he redistributed his remaining support forces.

On the German side Army Group B was once again to be strengthened at the expense of Army Group G, not only to satisfy Army Group B’s immediate requirements, but also in preparation for the Ardennes offensive scheduled for December.15 The bulk of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division withdrew from its lines opposite the 79th Division during the night of 15–16 October, and on 17 October the sector passed to the control of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division,16 with an effective

infantry strength of no more than a few battalions. To bolster the division for its defensive mission, Army Group G reinforced it with the 1416th Fortress Infantry Battalion, the 56th Fortress Machine Gun Battalion, and the 42nd Panzer Grenadier Replacement Battalion.

Next, the Fifth Panzer Army headquarters passed to Army Group B’s control on 16 October, leaving Army Group G with only two subordinate army commands, the First and the Nineteenth. The First Army assumed command of the LVIII Panzer Corps in the north, and the Nineteenth Army took control of the XLVII Panzer Corps in the south. A new boundary, separating the First and Nineteenth Armies, began at Ogeviller and ran northeast across the Vosges to pass a few miles north of Strasbourg. The XLVII Panzer Corps’ attachment to the Nineteenth Army was short-lived, and one day later, on 17 September, OB West also transferred this headquarters to Army Group B’s control, providing the Nineteenth Army with the LXXXIX Corps headquarters as a substitute.

Logistical problems, bad weather, and, apparently, slow intelligence analysis helped prevent the 79th Division from taking advantage of the German redeployments east of the Parroy forest. Moreover, the XV Corps was waiting for the 44th Infantry Division—the new third division that Eisenhower had promised Devers in September—to reach the front before the 79th Division resumed the offensive. The 44th Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Robert L. Spragins, closed its assembly area near Lunéville on 17 October and during the next few days took over 79th Division positions from the vicinity of Embermenil south to the Vezouse River, while the 79th concentrated on a narrower front for a new attack.

On 21 and 22 October the three regiments of the 79th Division, advancing abreast across a front of almost two and a half miles, gained nearly a mile and a half in a northeasterly direction from Embermenil, thus securing better defensive terrain as well as better observation of German positions. On the 23rd the 44th Division started to relieve the 79th Division in place, which then began a much needed rest. Tragically, for General Patch, commanding the Seventh Army, the relief came two days too late. His son, Capt. Alexander M. Patch III, commanding Company C of the 315th Infantry, was killed by German mortar fire on 22 October, and the army commander was to feel the loss deeply for many months to come.

For the remainder of October the 44th Infantry Division played a rather static role, but one that prepared the new division for forthcoming offensive actions. Its activities were limited mostly to patrols and artillery duels, and little attempt was made to gain new ground. Elements of the 106th Calvary Group maintained contact with Third Army units along the line

of the Rhine–Marne Canal and undertook limited reconnaissance, but adopted a generally defensive attitude.

To the south, the French 2nd Armored Division continued to rest and refit. From 30 September to 3 October, units of the division had supported the advance of the VI Corps’ 45th Division to the Rambervillers area, culminating in several sharp engagements along the Rambervillers–Baccarat highway. On the 3rd the French armor was relieved of its responsibilities in the zone by the VI Corps’ 117th Cavalry Squadron, and, as planned, the division went on the defensive for the remainder of the month.

During this period the French division kept three of its four combat commands17 in the line, rotating each to the rear for sorely needed rest, rehabilitation, and vehicle maintenance. From 3 through 30 October the division lost approximately 35 men killed and 140 wounded, most of them as a result of German artillery or mortar fire.18 As dusk came on the 30th, the division was preparing to launch an attack to seize Baccarat, an operation that once again would alarm the German high command and divert their attention from the more direct approaches to the Saverne Gap.