Chapter 2: Japan Strikes

Pearl Harbor1

Perhaps no action in American military history has been so thoroughly documented, examined, and dissected as the Pearl Harbor attack. Investigation has followed investigation; a host of books have been written on the subject, all in an effort to pin down the responsibility in the welter of charge and countercharge. The issue of what individuals or set of circumstances, if any, should bear the blame for the success of the Japanese raid has not been, and may never be finally decided. On one point, however, there has been unanimous agreement—that the courage of the vast majority of defending troops was of a high order.

The first inkling of the Japanese attack came not from the air, but from the sea. At 0637 on 7 December, more than an hour before any enemy planes were sighted, an American patrol bomber and the destroyer Ward attacked and sank an unidentified submarine in the restricted waters close to the entrance to Pearl Harbor.2 This vessel was one of five Japanese two-man submarines which had the extremely risky mission of penetrating the Pacific Fleet’s stronghold. The midgets were transported to the target on board large long-range submarines, part of an undersea scouting and screening force which had fanned out ahead of the enemy carriers. Not one of the midget raiders achieved any success; four were sunk and one ran aground.

The Japanese attack schedule allowed the Americans little time to evaluate the significance of the submarine sighting. The first enemy strike group was airborne and winging its way toward Oahu before the Ward fired its initial spread of depth charges. The Japanese carrier force had turned in the night and steamed full ahead for its target, launching the first plane at 0600 when the ships were approximately 200 miles north of Pearl Harbor. A second strike group took off at 0745 when the carriers had reached a position 30 miles closer to the American base. Although a radar set on the island picked up the approaching planes in time to give warning, the report of the sighting was believed an error and disregarded, and the Japanese fighters and bombers appeared unannounced over their objectives.

The enemy plan of attack was simple. Dive bombers and fighter planes would

strafe and bomb the major Army and Navy airfields in an attempt to catch defending aircraft on the ground. Simultaneously, the battleships moored to pilings along the shore of Ford Island would be hit by high-and low-level bombing attacks. The shipping strike groups included large numbers of dive and horizontal bombers, since the Japanese anticipated that protective netting might prevent their lethal torpedo bombers from being fully effective. In all, 321 planes took part in the raid, while 39 fighters flew protective cover over the carriers to guard against a retaliatory attack that never materialized.

At 0755 the soft stillness of Sunday morning was broken by the screaming whine of dive bombers and the sharp chatter of machine guns. At half a dozen different bases around the island of Oahu Japanese planes signaled the outbreak of war with a torrent of sudden death. Patrol bombers were caught in the water at Naheohe Naval Air Stations, across the island from Honolulu; closely parked rows of planes, concentrated to protect them from sabotage, were transformed into smoking heaps of useless wreckage at the Army’s Wheeler and Hickam Fields, the Marines’ air base at Ewa, and the Navy’s Ford Island air station. The attack on the airfields had barely started before the first bombs and torpedoes were loosed against the sitting targets of “battleship row.” Within minutes most of the battleships at the Ford Island moorings had been hit by one or more torpedoes and bombs. If the Japanese had drawn off after the first fifteen minutes of their attacks, the damage done would have been terrific, but the enemy planes kept on strafing and bombing and the toll of ships, planes, and men soared.

The Americans did not take their beating lying down. The first scattered shots from sentries ashore and watch standers who manned antiaircraft guns on board ship flashed back at the enemy even before the bugles and boatswains’ pipes sounded “Call to Arms” and “General Quarters.” The ships of the Pacific Fleet were on partial alert even in port and most of the officers and men were on board. Crew members poured up the ladders and passages from their berthing compartments to battle stations. While damage control teams tried to put down fires and shore up weakened bulkheads, gun crews let loose everything they had against the oncoming planes. In many cases guns were fired from positions awash as ships settled to the bottom and crewmen were seared with flames from fuel and ammunition fires as they continued to serve their weapons even after receiving orders to abandon ship. On many vessels the first torpedoes and bombs trapped men below deck and snuffed out the lives of others before they were even aware that the attack was on.

The reaction to the Japanese raid was fully as rapid at shore bases as it was on board ship, but the men at the airfields and the navy yard had far less to fight with. There was no ready ammunition at any antiaircraft gun position on the island; muzzles impotently pointed skyward while trucks were hurried to munitions depots. Small arms were broken out of armories at every point under attack; individuals manned the machine guns of damaged aircraft. The rage t strike back at the Japanese was so strong that men even fired pistols at the enemy planes as they swooped low to strafe.

At Ewa every Marine plane was knocked out of action in the first attack.

Japanese Photograph of the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor showing the line of American battleships caught at their mooring near Ford Island. (USN 30550)

Japanese landing on Guam depicted by a propaganda artist who shows a portion of the troops and transports of the South Seas Detached Force. (SC 301167)

Two squadrons of Japanese fighters swept in from the northwest at 1,000 feet and dived down to rake the aircraft parked near the runways with machine-gun and cannon fire. Pilots and air crewmen ran to their planes in an attempt to get them into the air or drag them out of the line of fire, but the Japanese returned again and again to complete the job of destruction. When the enemy fighters drew off at about 0825 they left behind a field littered with burning and shot-up aircraft.

The men of MAG-21 recovered quickly from their initial surprise and shock and fought back with what few rifles and machine guns they had. Salvageable guns were stripped from damaged planes and set up on hastily improvised mounts; one scout-bomber rear machine gun was manned to swell the volume of antiaircraft fire. Although the group commander, Lieutenant Colonel Claude A. Larkin, had been wounded almost as soon as he arrived at the field that morning, he continued to coordinate the efforts to meet further enemy attacks.

Two Japanese dive bombers streaked over the field from the direction of Pearl Harbor at 0835, dropping light fragmentation bombs and strafing the Marine gun positions. A few minutes after the bombers left, the first of a steady procession of enemy fighters attacked Ewa as the Japanese began assembling a cover force at nearby Barber’s Point to protect the withdrawal of their strike groups. The Marine machine guns accounted for at least one of the enemy planes and claimed another probable. Two and three plane sections of fighters orbited over the field, and occasionally dived to strafe the gunners, until the last elements of the Japanese attack force headed out to sea around 0945.

Three of the Marine airmen were killed during the attacks, a fourth died of wound; 13 wounded men were treated in the group’s aid station. Flames demolished 33 of the 47 planes at the field; all but two of the remainder suffered major damage. The sole bright note in the picture of destruction was the fact that 18 of VMSB-231’s planes were on board the Lexington, scheduled for a fly-off to Midway, and thereby saved from the enemy guns.

Within the same half hour that witnessed the loss of Ewa’s planes, the possibility of effective aerial resistance was canceled out by similar enemy attacks all over Oahu. Ford Island’s seaplane ramps and runways were made a shambles of wrecked and burning aircraft in the opening stage of the Japanese assault. The Marines of the air station’s guard detachment manned rifles and machine guns to beat off further enemy thrusts, but the dive bombers had done their job well. There was no need for them to return. The focus of all attacks became the larger ships in the harbor.

The raid drew automatic reactions from the few Marines in the navy yard who saw the first enemy planes diving on the ships. While the guard bugler broke the majority of the men of the barracks detachment and the 1st and 3rd Defense Battalions out of their quarters, the early risers were already running for the armories and gun sheds. By 0801 when Colonel Pickett ordered the defense battalion machine-gun groups to man their weapons, eight of the guns had already been set up. More machine guns were hastily put in position and men were detailed to belt the ammunition needed to feed them, while rifle ammunition was issued to the hundreds of men assembled on the barracks’ parade ground. Pickett ordered the 3-inch antiaircraft guns in the defense battalions’ reserve supplies to be taken out of storage and emplaced on the parade. He dispatched trucks and working parties of the 2nd Engineer Battalion to Lualualei, 27 miles up in the hills, to get the necessary 3-inch shells. The Marine engineers also

sent their heavy earth-moving equipment to Hickam Field to help clear the runways.

Thirteen machine guns were in action by 0820 and the gunners had already accounted for their first enemy dive bomber. During the next hour and a half the fire of twenty-five more .30’s and .50’s was added to the yard’s antiaircraft defenses, and two more planes, one claimed jointly with the ships, were shot down. The 3-inch guns were never able to get into action. The ammunition trucks did not return from the Lualualei depot until 1100, more than an hour after the last Japanese aircraft had headed back for their carriers. By that time the personnel of all Marine organizations in the navy yard area had been pooled to reinforce the guard and antiaircraft defense, to provide an infantry reserve, and to furnish the supporting transport and supply details needed to sustain them.

In the course of their attacks on battleship row and the ships in the navy yard’s drydocks, the enemy planes had strafed and bombed the Marine barracks area, and nine men had been wounded. They were cared for in the dressing stations which Pickett had ordered set up at the beginning of the raid to accommodate the flow of wounded from the stricken ships in the harbor. Many of these casualties were members of the Marine ship detachments; 102 sea-going Marines had been killed during the raid, six later died of wounds, and 49 were wounded in action.3

The enemy pilots had scored heavily: four battleships, one mine layer, and a target ship sunk; four battleships, three cruisers, three destroyers, and three auxiliaries damaged. Most of the damaged ships required extensive repairs. American plane losses were equally high: 188 aircraft totally destroyed and 31 more damaged. The Navy and Marine Corps had 2,086 officers and men killed, the Army 194, as a result of the attack; 1,109 men of all the services survived their wounds.

Balanced against the staggering American totals was a fantastically light tally sheet of Japanese losses. The enemy carriers recovered all but 29 of the planes they had sent out; ship losses amounted to five midget submarines; and less than a hundred men were killed.

Despite extensive search missions flown from Oahu and from the Enterprise, which was less than 175 miles from port when the sneak attack occurred, the enemy striking force was able to withdraw undetected and unscathed. In one respect the Japanese were disappointed with the results of their raid; they had hoped to catch the Pacific Fleet’s carriers berthed at Pearl Harbor. Fortunately, the urgent need for Marine planes to strengthen the outpost defenses had sent the Lexington and the Enterprise to sea on aircraft ferrying missions. The Enterprise was returning to Pearl on 7 December after having flown off VMF-211’s fighters to Wake, and the Lexington, en route to Midway with VMSB-231’s planes, turned back when news of the attack was received. Had either or both of the carriers been sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor, the outlook for the first months of the war would have been even more dismal. The Japanese success had the effect of delaying the schedule of retaliatory attack and amphibious operations

in the Central Pacific that had been outlined in Rainbow 5. A complete reevaluation of Pacific strategy was necessary.

The critical situation facing the outpost islands was clearly appreciated and an attempt was made to get reinforcements to Wake before the Japanese struck; it did not come in time. The tiny atoll was one of the first objectives on the enemy timetable of conquest.4 Midway was more fortunate; when the Lexington returned to Pearl on 10 December with its undelivered load of Marine scout bombers, they were ordered to attempt an over-water flight to the atoll. On 17 December, ten days after the originally scheduled fly-off, 17 planes of VMSB-231, shepherded by a naval patrol bomber, successfully made the 1,137-mile flight from Oahu to Midway. It was the longest single-engine land plane massed flight on record, but more important it marked a vital addition to Midway’s defensive potential.

The outpost islands needed men and materiel as well as planes. Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, Commandant of the 14th Naval District, gave the responsibility for organizing and equipping these reinforcements to Colonel Pickett. On 13 December, all Marine ground troops in the district were placed under Pickett as Commanding Officer, Marine Forces, 14th Naval District. The necessary reinforcements to be sent to Midway, Johnston, and Palmyra were drawn from the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Defense Battalions. By the month’s end the first substantial increments of men, guns, and equipment had been received at each of the outposts.5 They were not safe from attacks by any means, but their positions were markedly stronger.

Guam Falls6

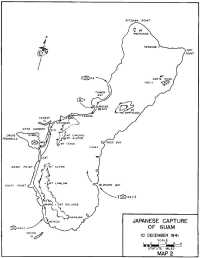

The Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922 provided for the maintenance of the status quo in regard to fortifications and naval bases in certain areas of the Pacific. American adherence to these terms through the 14-year life of the treaty had the practical effect of weakening the defenses of the Philippines and preventing the development of Guam as a naval stronghold. The Hepburn Board of 1938 recommended that Guam be heavily fortified and garrisoned,7 but Congress failed to authorize the expenditure of the necessary funds. Unhappily, the planners of Rainbow 5 had to concede the capture of the island in the first stages of a war with the Japanese. It was almost as if they could look over enemy shoulders and see the terse direction to the commander of the Japanese Fourth Fleet to “invade Wake and Guam as quickly as possible”8 at the onset of hostilities. (See Map 2)

Guam was a fueling station for naval vessels making the long run to and from the Orient, a relay point for the trans-Pacific cable, the site of a naval radio station, and a stop for Pan American clippers. Assigned to protect its 20,000 natives and its 228 square miles of rugged, jungled terrain was a token force of 153

Marines. Backing them up was a Guamanian infantry unit, the 80-man Insular Force Guard, and a volunteer native naval militia with 246 ill-armed and ill-trained members.9 The island’s government departments and naval station activities were manned by 271 regular Navy personnel. A naval officer, Captain George J. McMillin, was both island governor and garrison commander.

The war threat was so real by October 1941 that all women and children of U.S. citizenship were evacuated from Guam. On 6 December the garrison destroyed all its classified papers and like other Pacific outposts awaited the outcome of the U.S.-Japanese negotiations in Washington. The word came at 0545 on 8 December (7 December, Pearl Harbor time). Captain McMillin was informed of the enemy attack by the Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet. In less than three hours Saipan-based Japanese bombers were over the island.

The initial enemy target was the mine sweeper USS Penguin in Apra Harbor; this small ship’s 3-inch and .50 caliber guns were the only weapons larger than .30 caliber machine guns available to the Guam garrison. Under repeated attacks, the Penguin went to the bottom, and her survivors joined the forces ashore. The attack continued throughout the daylight hours with flights of bombers hitting the various naval installations and strafing roads and villages. The island capital, Agana, was cleared of civilians, and the few local Japanese were rounded up and interned.

That night a native dugout landed near Ritidian Point on the northern cape of the island, and the three men in it were captured. They claimed to be Saipan natives sent over to be on hand as interpreters when the Japanese landed. These natives insisted that the Japanese intended to land the next morning (9 December) on beaches near Agana. Captain McMillin suspected a trick. He believed that by this ruse the Japanese sought to draw the Marines out of their prepared positions in the butts of the rifle range at Sumay on Orote Peninsula. He decided not to allow this information to cause a shift of his major defensive force from a position which guarded important Apra Harbor.

By guess or knowledge the Saipan natives had one of the landing sites located accurately, but they were off on their time. The 9th brought no landing, but the bombers came back to give Guam another pounding. The Insular Force Guard was posted to protect government buildings in Agana, but the rest of the island’s garrison remained at their assigned posts. Lieutenant Colonel William K. McNulty’s 122 Marines of the Sumay barracks continued to improve their rifle range defenses, and the 28 Marines who were assigned to the Insular Patrol, the island’s police force, kept their stations in villages throughout Guam.

After the Japanese bombers finished for the day all was quiet until about 0400 on 10 December. At that time flares burst over Dungcas Beach north of Agana, and some 400 Japanese sailors of the 5th Defense Force from Saipan came ashore. While the naval landing party moved into Agana where it clashed with the Insular Force Guard, elements of the Japanese

Map 2: Japanese Capture of Guam

South Seas Detached Force (approximately 5,500 men)10 made separate landings at Tumon Bay in the north, on the southwest coast near Merizo, and on the eastern shore of the island at Talafofo Bay.

At Agana’s plaza the lightly-armed Guamanians, commanded by Marine First Lieutenant Charles S. Todd, stood off the early Japanese attacks, but their rifles and machine guns did not provide enough firepower to hold against a coordinated attack by the Dungcas Beach landing force. Captain McMillin, aware of the overwhelming superiority of the enemy, decided not to endanger the lives of the thousands of civilians in his charge by further and fruitless resistance. “The situation was simply hopeless,” he later related.11 He surrendered the island to the Japanese naval commander shortly after 0600, and sent orders to the Marines at Sumay not to resist. The word did not reach all defenders, however, and scattered fighting continued throughout the day as the enemy spread out to complete occupation of the island. But this amounted to only token resistance. There was no chance that the determined Japanese might be driven off by a force so small, even if the defenders could have regrouped. Guam had fallen, and it would be two and a half years before the United States was in a position to win it back.

During the two days of bombing and in the fighting on 10 December, the total garrison losses were 19 killed and 42 wounded including four Marines killed and 12 wounded.12 The civilian population suffered comparable but undetermined casualties. The Japanese evacuated American members of the garrison to prison camps in Japan on 10 January 1942, and the enemy naval force that had been present at the surrender settled down to duty as occupation troops.

First Attack on Midway13

Part of the Japanese striking force which raided Pearl Harbor was a task unit of two destroyers and a tanker which proceeded independently from Tokyo Bay to a separate target—Midway. The mission of the destroyers was implied in their designation as the Midway Neutralization Unit; they were to shell the atoll’s air base on the night of 7 December while the Japanese carrier force retired from the Hawaiian area. (See Map 10, Map Section)

Dawn of 7 December found five seaplanes of Midway’s patrol bomber squadron (VP-21) aloft on routine search missions; two other (Dutch) patrol bombers had just taken off for Wake, next leg of their journey to the Netherlands East Indies. On the Sand Island seaplane ramp two more PBYs (Catalina patrol

bombers) were warming up to guide in VMSB-231 which was scheduled to fly off the Lexington that day. At 0630 (0900 Pearl Harbor time) a Navy radio operator’s signal from Oahu flashed the first news of the Pearl Harbor attack. A few minutes later a dispatch from Admiral Bloch confirmed this report and directed that current war plans be placed in effect.

Commander Cyril T. Simard, the Island Commander, recalled the Dutch PBYs (which were then put to use by VP-21), established additional air search sectors, and ordered Lieutenant Colonel Harold D. Shannons’ 6th Defense Battalion to general quarters. The remainder of the day was spent in preparation for blackout, and in issuing ammunition, digging foxholes, and testing communications. All lights and navigational aids were extinguished after it was learned that the Lexington, with VMSB-231 still on board, had been diverted to seek the enemy’s Pearl Harbor striking force.

Air searches returned late in the day without having sighted any signs of Japanese ships or planes, and the atoll buttoned up for the night with all defensive positions fully manned. At 1842, a Marine lookout saw a flashing light some distance southwest of Sand Island, but it quickly disappeared, and it was about 2130 before the one operational radar on Sand began picking up what seemed to be surface targets in the same general direction. Simultaneously two other observers, equipped with powerful 8x56 night glasses, reported seeing “shapes” to seaward.

Shannon’s searchlight battery commander, First Lieutenant Alfred L. .Booth, requested permission to illuminate, but his request was turned down. Senior officers did not want to risk premature disclosure of defensive positions. It was also erroneously believed that friendly ships were in the area, and there were strict orders against illuminating or firing without specific orders.14

The apprehension of these observers was justified. The Japanese destroyers Akebono [ed.: Rising Sun lists Sazanami] and Ushio had left their tanker Shiriya at a rendezvous point some 15 miles away and made landfall on the atoll at about 2130. By the time Lieutenant Booth had been cautioned about his searchlights, the two enemy ships had their guns trained on Midway and were ready to make their first firing run. The firing began at 2135.

The first salvos fell short, but as the destroyers closed range on a northeast course the shells began to explode on Sand Island. The initial hits struck near Battery A’s 5-inch seacoast guns at the south end of the island. and subsequent rounds bracketed the island’s power plant, a reinforced concrete structure used also as the command post of a .50 caliber antiaircraft machine-gun platoon. One round came through an air vent and exploded inside the building. The Japanese ships then suspended fire while they closed on the atoll for a second firing run.

In the island’s power plant First Lieutenant George H. Cannon, although severely wounded, directed the re-establishment of wrecked communications and the evacuation of other wounded. He refused evacuation for his own wounds until after Corporal Harold R. Hazelwood had put the switchboard back in operation. Cannon died a few minutes after reaching the

aid station, but for this action he received posthumous award of the Medal of Honor. He was the first Marine so honored in World War II.

Meanwhile the enemy ships opened fire again, this time at closer range, and Commander Simard ordered Shannon to engage targets of opportunity. Japanese shells set the roof of the seaplane hangar on Sand ablaze, lighting up the target for the enemy gunners, and accurate salvos struck the Pan American radio installation, the island laundry, and adjacent shops. At 2153 the Marine searchlight crews got Shannon’s orders to illuminate, but by then only the light on the south end of Sand could bear on the ships. This light silhouetted the Akebono about 2,500 yards south of the island, before a near miss from one of the destroyers put it out of commission. Crewmen reacted immediately to get the light back in action and on target, but Battery A’s 5-inchers stayed silent because communication damage had prevented passing of Shannon’s command to open fire.15

But Captain Jean H. Buckner, commanding Battery D’s 3-inch antiaircraft guns, could now see the large Japanese battle flag on the Akebono’s foremast, and he ordered his guns into action. Splashes could not be made out, although illumination was excellent, and Buchner’s fire control men were positive that the shells were either passing through the ships’ superstructures or into their hulls. Battery B (First Lieutenant Rodney M. Handley) on Eastern Island now added its 5-inch fire to the battle and .50 caliber machine guns opened up on the targets which were well within range. This firing from the Marine batteries kept up for five minutes before the Japanese succeeded in knocking out the searchlight. Although some observers believed that the Ushio had also been hulled, results of this Marine fire have never been determined.16 Both Japanese ships returned soon after the light was shot out and a Pan American clipper captain flying overhead that night en route from Wake reported seeing an intense fire on the surface of the sea and the wakes of two ships on the logical retirement course of the destroyers. Both enemy ships, however, returned to Japan safely, despite any damage that might have been done by the Marine guns.

The enemy fire has cost the 6th Defense Battalion two killed and ten wounded;17 two men from the naval air station were killed and nine wounded. Material damage on Midway was not too severe and was confined to Sand Island; the airfield on Eastern Island was not touched. The seaplane hangar had burned, although the frame was still intact, and one plane was lost in the flames. Another PBY was badly damaged by shell fragments, and fragments also caused minor damage to a number of buildings. The garrison had stood off its first Japanese attack, but there was little comfort in this. The defenders estimated—correctly—that the enemy would be back sooner or later with a much more serious threat.

With the outbreak of war, completion of the coastal and antiaircraft defenses of Midway took first priority and Marines were treated to the welcome and unusual

sight of the civilian contractor’s heavy equipment turned to 0n dugout and battery construction. Authorities at Pearl Harbor were determined to get reinforcements to the atoll and within a week after VMSB-231 made its historic long flight from Oahu, two batteries of the 4th Defense Battalion with additional naval 3-inch and 7-inch guns for coast defense were being unloaded. On Christmas, the Brewster Buffaloes of VMF-221 flew in from the Saratoga which had been rushed out to Pearl from San Diego after the Japanese attack. This carrier had taken part in the abortive attempt to relieve Wake. The next day the island received another contingent of 4th Defense Battalion men, the ground echelon of VMF-221, and much needed defense materiel when the seaplane tender Tangier, which had also been headed for Wake, unloaded at Midway instead. By the end of December the atoll, which was now Hawaii’s most important outpost, had for its garrison a heavily reinforced defense battalion, a Marine scout-bomber and a fighter squadron, and VP-21’s patrol bombers. Midway was in good shape to greet the Japanese if they came back, and the passage of every month in the new year made the atoll a tougher nut to crack.18

The Southern Outposts19

Tiny Johnston Island, set off by itself in the open sea southwest of Hawaii, proved to be a favorite target of Japanese submarines in the first month of the war. It was too close to the Pacific Fleet base at Pearl and too limited in area to make it a prize worth risking an amphibious assault, but its strategic location, like an arrowhead pointing at the Japanese Marshalls, made damage to its air facilities well worth the risk of bombardment attempts. The airfield on the atoll’s namesake, Johnston Island, was only partially completed on 7 December, but temporary seaplane handling facilities were in operation at Sand Islet, the only other land area within the fringing reef. There was no permanent patrol plane complement, but Johnston was an important refueling stop and a couple of PBYs were usually anchored in the lagoon.

The news of the outbreak of war created a flurry of activity on Johnston, and the civilian contractor’s employees turned to at top speed to erect additional earthworks around the Marine guns and to prepare bomb shelters.20 No Japanese ship or submarine made its appearance on 7 December, perhaps because the first day of war found the Indianapolis and five destroyer minesweepers at Johnston testing the performance of the Higgins landing boat on coral reefs.21 These ships were

immediately recalled toward Pearl to form part of the extensive search pattern for the enemy carrier force, and Johnston’s defense rested with its own slim garrison. Major Francis B. Loomis, Jr., Executive Officer of the 1st Defense Battalion, caught while returning to Pearl by air from an inspection of the western outposts, assumed command of the Johnston detachment as senior Marine officer present.

Shortly after dark on 12 December a submarine surfaced 8,000 yards off Sand Islet and began firing green star clusters which burst high over the island. The 5-inch battery could not pick up the vessel in its sights, but it fired on star shell in the general direction of the submarine. The submarine ceased firing immediately as she evidently was not seeking a duel.

The next enemy attack came at dusk three days later. The supply ship Burrows had delivered a barge load of supplies originally intended for the Wake garrison and picked up 77 civilian construction employees for return to Pearl when a sentry atop Johnston’s water tower spotted a flash to seaward and sounded general quarters. The flash had been spotted by the batteries also, and the 5-inch control estimated the range at 9,000 yards. The 3-inch director and height finder made out two ships, one larger than the other. The first two enemy salvos bracketed Johnston and the third struck near the contractor’s power house and set off a 1,200-gallon oil tank which immediately fired the building. A strong wind whipped up 50-foot flames from the oil fire, and “as observed from the Naval Air Station at Sand Islet, Johnston Island seemed doomed.”22 The Japanese continued to fire for ten minutes at this well-lighted target and they hit several other buildings. The 5-inch guns delivered searching fire, and just as the Marines were convinced they were hitting close aboard their targets, the enemy fire ceased abruptly.

The enemy vessels had fired from the obscuring mists of a small squall and spotters ashore never clearly saw their targets, but the defenders believed that they had engaged two surface vessels, probably a light cruiser and a destroyer. Later analysis indicated, however, that one or more submarines had made this attack. Fortunately no one in the garrison was hurt by the enemy fire, although flames and fragments caused considerable damage to the power house and water distilling machinery. The Burrows, although clearly outlined by the fire, was not harmed. The fact that its anchorage area was known to be studded with submerged coral heads probably discouraged the Japanese from attempting an underwater attack, and Johnston’s 5-inch battery ruled out a surface approach.

During the exchange of fire one of the Marines’ 5-inch guns went out of action. Its counter-recoil mechanism failed. After this the long-range defense of the island rested with one gun until 18 December when two patrol bombers from Pearl arrived to join the garrison. This gun was enough, however, to scare off an enemy submarine which fired star shells over Sand Islet after dark on 21 December. Again the simple expedient of firing in the probable direction of the enemy was enough to silence the submarine. The

next night, just as the ready duty PBY landed in the lagoon, another submarine, perhaps the same one that had fired illumination over Sand, fired six shells at the islets. Both 5-inchers on Johnston now were back in action and each gun fired ten rounds before the submarine submerged. The patrol plane was just lifting from the water as the last enemy shot was fired. Only one shell hit Sand, but that one knocked down the CAA homing tower and slightly wounded one Marine.

Johnston Island was clearly a discouraging place to attack, and the shelling of 22 December marked the last enemy attempt at surface bombardment. It was just as well that the Japanese decided to avoid Johnston, because reinforcement from Pearl soon had the atoll bursting at its seams with men and guns. An additional 5-inch and a 3-inch battery, 16 more machine guns, and the men to man them arrived on 30 December. In January a provisional infantry company was sent and eventually the garrison included even light tanks. The expected permanent Marine fighter complement never got settled in at Johnston’s airfield. The island became instead a ferrying and refueling stop for planes going between Pearl and the South and Southwest Pacific.

Palmyra, 900 miles southeast of Johnston, also figured in the early development of a safe plane route to the southern theater of war. But before the atoll faded from the action reports it too got a taste of the gunfire of a Japanese submarine. At dawn on 24 December an enemy raider surfaced 3,000 yards south of the main island and began firing on the dredge Sacramento which was anchored in the lagoon and clearly visible between two of Palmyra’s numerous tiny islets. Only one hit was registered before the fire of the 5-inch battery drove the submarine under. Damage to the dredge was minor and no one was injured.

Colonel Pickett’s command at Pearl Harbor had organized strong reinforcements for Palmyra and these arrived before the end of December. Lieutenant Colonel Bert A. Bone, Commanding Officer of the 1st Defense Battalion, arrived with the additional men, guns, and equipment to assume command of the defense force. On 2 March the official designation of the Marine garrison on Palmyra was changed to 1st Defense Battalion and former 1st Battalion men at other bases were absorbed by local commands. The Marine Detachment at Johnston became a separate unit.

After these submarine attacks of December, Palmyra and Johnston drop from the pages of an operational history. The atolls had served their purpose well; they guarded a vulnerable flank of the Hawaiian Islands at a time when such protection was a necessity. While the scene of active fighting shifted westward the garrisons remained alert, and when conditions permitted it many of the men who had served out the first hectic days of the war on these lonely specks in the ocean moved on to the beachheads of the South and Central Pacific.