Chapter 3: The Southern Lifeline

Strategic Reappraisal1

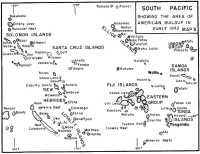

In December 1941, reverse followed reverse in the fortunes of the Allies in the Pacific. The Japanese seemed to be everywhere at once and everywhere successful. Setbacks to the enemy schedule of conquest were infrequent and temporary. On the Asian mainland Hong Kong fell and Japanese troops advanced steadily down the Malay Peninsula toward Singapore. in the Philippines Manila was evacuated and American-Filipino forces retreated to Bataan and Corregidor for a last-ditch stand. To the south the first Japanese landing had been made on Borneo, and superior enemy forces prepared to seize the Netherlands East Indies. The capture of Wake and Guam gave the Japanese effective control over the Central Pacific from the China coast to Midway and Johnston. (See Map 1, Map Section)

By the turn of the year only the sea area between the Hawaiian Islands and the United States and the supply route from the States through the South Pacific to New Zealand and Australia were still in Allied hands. The responsibility for holding open the lines of communication to the Anzac area2 rested primarily with the U.S. Pacific Fleet. On 31 December that fleet came under the command of the man who was to direct its operations until Japan unconditionally surrendered—Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (CinCPac).

As soon as he arrived at Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was given a dispatch from Admiral Ernest J. King, the newly appointed Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (CinCUS, later abbreviated as CominCh). King’s message outlined Nimitz’s two primary tasks as CinCPac. He was to use his ships, planes, and men in:

1. Covering and holding the Hawaii-Midway line and maintaining its communications with the west coast.

2. Maintaining communications between the west coast and Australia, chiefly by covering, securing and holding the Hawaii-Samoa line, which should be extended to include Fiji at the earliest possible date.3

Although the Japanese had severely damaged the Pacific Fleet in their Pearl Harbor raid, they had concentrated on

ships rather than installations, and the repair facilities of the navy yard were virtually untouched. Round-the-clock work promptly restored to operation many vessels which might otherwise have been lost for good or long delayed in their return to fleet service. But Nimitz’s strength was not enough to hazard a large scale amphibious offensive, even with the addition of reinforcements sent from the Atlantic Fleet. In the first few months of 1942, Allied strategists had to be content with defensive operations. The few local attacks they mounted were hit-and-run raids which did little more than boost home-front morale at a time when most news dealt with defeat and surrender.

From 22 December to 14 January, the political and military leaders of the United States and Great Britain met in Washington (the ARCADIA Conference) to chart the course of Allied operations against the Axis powers. The Americans, despite the enormity of the Japanese attack, reaffirmed their decision of ABC-1 that Germany was the predominant enemy and its defeat would be decisive in the outcome of the war. The Pacific was hardly considered a secondary theater, but the main strength of the Allied war effort was to be applied in the European, African, and Middle Eastern areas. Sufficient men and materiel would be committed to the battle against Japan to allow the gradual assumption of the offensive.

One result of the ARCADIA meetings was the organization of the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS), a supreme military council whose members were the chiefs of services in Great Britain and the United States. The CCS was charged with the strategic direction of the war, subject only to the review of the political heads of state. The necessity of presenting a united American view in CCS discussions led directly to the formation of the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) as the controlling agency of American military operations.

On 9 February 1942, the first formal meeting of General George C. Marshall (Chief of Staff, United States Army), Lieutenant General Henry H. Arnold (Chief of the Army Air Corps), Admiral Harold R. Stark (CNO), and Admiral King (CominCh) took place. Expect for the combination of the offices of CominCh and CNO in the person of Admiral King which took effect of 26 March (Admiral Stark became Commander U.S. Naval Forces Europe) and the addition of Admiral William D. Leahy as Chief of Staff to the President on 20 July, the membership of the JCS remained constant for the duration of the war. As far as the Marine Corps was concerned their representative on the JCS was Admiral King, and he was consistently a champion of the use of Marines at their greatest potential—as specially trained and equipped amphibious assault troops.4

On 10 January 1942, the CCS, acting with the approval of Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt, set up a unified, inter-Allied command in the western Pacific to control defensive operations against the Japanese along a broad sweep of positions from Burma through Luzon to New Guinea. The commander of ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) forces holding the barrier zone was the British Commander in Chief in India, General Sir Archibald P. Wavell; his ABDA air, naval, and ground commanders were respectively an Englishman, an American, and a Dutchman. But ABDA Command had no chance to stop the Japanese in the East Indies, Malaya, or the Philippines. Wavell’s forces were beaten back, cut off, or defeated before he could be reached by reinforcements that could make a significant difference in the fighting. By the end of February Singapore had fallen and the ABDA area was split by an enemy thrust to Sumatra. Wavell returned to India to muster troops to block Japanese encroachment into Burma. On 1 March ABDA Command was formally dissolved.

Although this first attempt at unified Allied command was short-lived and unsuccessful, it set a pattern which governed operational control of the war through its remaining years. This pattern amounted to the selection as over-all commander of a theater of an officer from the nation having the most forces in that particular theater. His principal subordinates were appointed from other nations also having interests and forces there. Realistically, the CCS tried to equate theater responsibility with national interest. On 3 March the Combined Chiefs approved for the western Pacific a new dividing line which cut through the defunct ABDA area. Burma and all Southeast Asia west of a north-south line between Java and Sumatra were added to Wavell’s Indian command and the British Chiefs of Staffs were charged with the strategic direction of this theater. The whole Pacific east of the new line was given over to American JCS control.

The Joint Chiefs divided the Pacific into two strategic entities, one in which the Navy would have paramount interests, the Pacific Ocean Area (POA), and the other in which the Army would be the dominant service, the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). (See Map 1, Map Section for boundary.) Naval planners had successfully insisted in JCS discussions that all positions such as New Caledonia, the New Hebrides, and New Zealand which guarded the line of communications from Pearl Harbor to Australia must be controlled by the Navy. In terms of the air age, the JCS division of the Pacific gave the Army operational responsibility for

an area of large land masses lying relatively close together where land power supported by shore-based air could be decisive. To the Navy the JCS assigned the direction of the was in a vast sea area with widely scattered island bases where the carrier plane reigned supreme.

The American commander in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, was the Joint Chiefs’ choice to take over direction of SWPA operations; Admiral Nimitz was selected to head POA activities. Formal announcement of the new set-up was not made until MacArthur had escaped from Corregidor and reached safety in Australia. On 18 March, with the consent of the Australian government, MacArthur was announced as Supreme Commander of the SWPA (CinCSWPA). The JCS directive outlining missions for both Pacific areas was issued on 30 March, and the confirmation of Nimitz as Commander in Chief of the POA (CinCPOA) followed on 3 April. By CCS and JCS agreement, both commanders were to have operational control over any force, regardless of service or nation, that was assigned to their respective theaters.

Nimitz still retained his command of the Pacific Fleet in addition to his duties as CinCPOA. The fleet’s striking arm, its carriers and their supporting vessels, stayed under Nimitz as CinCPac no matter where they operated. In the final analysis, however, the major decisions on employment of troops, ships, and planes were made in Washington with the advice of the theater commanders. MacArthur was a subordinate of Marshall and reported through him to the JCS; an identical command relationship existed between Nimitz and King.

Samoan Bastion5

The concern felt in Washington for the security of the southern route to Australia was acute in the days and weeks immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack. Despite world-wide demands on the troops and equipment of a nation just entering the war, General Marshall and Admiral King gave special attention to the need for holding positions that would protect Australia’s lifeline. Garrison forces, most of them provided by the Army, moved into the Pacific in substantial strength to guard what the Allies still held and to block further Japanese advances. Between January and April nearly 80,000 Army troops left the States for Pacific bases.

An infantry division was sent to Australia to take the place of Australian units committed to the fighting in the Middle East. At the other end of the lifeline, a new division was added to the Hawaiian Island garrison. Mixed forces of infantry, coast and antiaircraft artillery, and air corps units were established in early February at Canton and Christmas Islands, southwest and south of Pearl Harbor. At about the same time a New Zealand ground garrison reinforced by American pursuit planes moved into the Fiji Islands, and a small garrison was sent to the French-owned Society Islands to guard the eastern approaches to the supply route. In March a task force of

almost division strength arrived in New Caledonia and the Joint Chiefs sent additional Army garrison forces to Tongatabu in the Tonga Islands, south of Samoa, and north to Efate in the New Hebrides. By the end of March 1942 the supply route to Australia ran through a corridor of burgeoning island strong points and the potential threat of major Japanese attacks had been substantially lessened. (See Map 1)

Actually the initial Japanese war plan contemplated no advances into the South Pacific to cut the line of communications to Australia. The Allied leaders, however, can be forgiven for not being clairvoyant on this point, for the enemy’s chance to seize blocking positions along the lifeline was quite apparent. Samoa seemed to be one of the most inviting targets and its tiny garrison of Marines wholly inadequate to stand off anything but a minor raid. The necessity for building up Samoan defenses as a prelude for further moves to Fiji and New Caledonia had been recognized by Admiral King in his instructions to Nimitz to hold the Hawaiian-Samoa line,6 and reinforcements from the States to back up those instructions were underway from San Diego by 6 January. These men, members of the 2nd Marine Brigade, were the forerunners of a host of Marines who passed through the Samoan area and made it the major Marine base in the Pacific in the first year of the war.

Only two weeks’ time was necessary to organize, assemble, and load out the 2nd Brigade. Acting on orders from the Commandant, the 2nd Marine Division activated the brigade on 24 December at Camp Elliott, outside of San Diego. The principal united assigned to the new command were the 8th Marines, the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines, and the 2nd Defense Battalion (dispatched by rail from the east coast). Colonel (later Brigadier General) Henry L. Larsen was named brigade commander. A quick estimate was made of the special engineering equipment which the brigade would need to accomplish one of its most important missions—completion of the airfield at Tutuila. Permission was obtained to expend up to $200,000 in the commercial market for the purchase of such earth-moving equipment as could not be supplied from quartermaster stocks. When the first cargo ship arrived at San Diego on New Year’s day, the brigade went on a round-the-clock loading schedule. Sixty-two hours later all assigned personnel and gear had been loaded and the 4,798 officers and men were on their way to Tutuila.

When the news of Pearl Harbor reached Samoa, Lieutenant Colonel Lester A. Dessez, commanding the 7th Defense Battalion, ordered his troops to man their positions. The Samoan Marine Reserve Battalion was called to active duty and assigned to reinforce the defenses. Despite a spate of rumors and false alarms, no sign of the Japanese was evident until the night of 11 January, when a submarine shelled the naval station for about seven minutes from a position 10,000-15,000 yards off the north shore where the coast defense guns could not bear. The station suffered only light damage from the shells, some of which fell harmlessly into the bay, and two men were wounded slightly by fragments. The Marines remained on alert but received no further visits from the enemy.

On 19 January radar picked up signs of numerous ships, and observation stations on the island’s headlands soon confirmed the arrival of the 2nd Brigade.

While still at sea, General Larsen had received orders from the Navy Department appointing him Military Governor of American Samoa and giving him responsibility for the islands’ defense as well and supervisory control over the civil government. As soon as the ships docked antiaircraft machine guns of the 2nd Defense Battalion, were promptly unloaded and set up in the hills around Pago Pago harbor. The 8th Marines took over beach defense positions occupied by the 7th Defense Battalion and immediately began improving and expanding them. The artillerymen of 2/10 and the 2nd Defense set up their guns in temporary positions while they went to work on permanent emplacements. Navy scouting amphibians of a shore-based squadron (VS-1-D14) attached to the brigade soon were aloft on a busy schedule of antisubmarine and reconnaissance missions.

The airfield on Tutuila was only 10 per cent completed when Larsen arrived, but he directed that construction be pushed around the clock, work to go on through the night under lights. He also detailed the brigade’s engineer company to assist the civilian contractors in getting the field in shape. For the 2nd Brigade’s first three months in Samoa, its days were filled with defense construction. There was little time for any combat training not intimately connected with the problems of Samoan defense. The work was arduous, exacting, and even frustrating, since the brigade had arrived during the rainy season and the frequent tropical rainstorms had a habit of destroying in minutes the results of hours of pick and shovel work.

General Larsen took immediate steps after his arrival in American Samoa to ascertain the status of the defenses in Western (British) Samoa, 40 or so miles northwest of Tutuila. On 26 January the brigade intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel William L. Bales, flew to Apia, the seat of government on the island of Upolu, to confer with the New Zealand authorities and make a reconnaissance of Upolu and Savaii, the two principal islands. The New Zealanders were quite anxious to cooperate with the Marines since they had a defense force of only 157 men to guard two large islands with a combined coastline of over 250 miles. Bales whose investigation was aimed primarily at discovering the feasibility of developing either or both of the islands into a military base, reported back that Upolu’s harbor facilities, road net, and several potential airfield sites made it readily susceptible to base development. He found, on the other hand, that Savaii had no safe major anchorages and that its lava-crusted surface did “not offer airfield sites that could be developed quickly by the Japanese or anyone else.”7 On his return to Tutuila, Lieutenant Colonel Bales reported to General Larsen that:–

In its present unprotected state, Western Samoa is a hazard of first magnitude for the defense of American Samoa. The conclusion is unescapable that if we don’t occupy it the Japanese will and there may not be a great deal of time left.8

Naval authorities in Washington and Pearl Harbor recognized the desirability

of occupying Western Samoa and extended their interest to include Wallis (Uea) Island, a small French possession 320 miles from Tutuila on the western approaches to Samoa. Negotiations were entered into with New Zealand regarding the defense of Western Samoa, and the Free French government in regard to he occupation of Wallis. In March warning orders were sent out to Larsen’s brigade and both marine divisions to be prepared to furnish troops for the garrisoning of Western Samoa and Wallis.9 Negotiations for the use of land and other facilities in Western Samoa were completed on 20 March when Larsen and a New Zealand representative signed an agreement giving the Americans responsibility for defense of all the Samoan islands. This group, together with Wallis, was now considered a tactical entity and a new Marine brigade was to be organized to occupy the western islands.

As an advance force of this new garrison, the 7th Defense Battalion was sent to Upolu on 28 March, and a small detachment was established on Savaii. In the States, the 1st Marine Division at New River, North Carolina, organized the 3rd Marine Brigade on 21 March with Brigadier General Charles D. Barrett in command. Its principal units were the 7th Marines and the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines. The 7th’s 3rd Battalion and Battery C of 1/11 were detached on the 29th to move overland to the west coast for further transfer to Samoa as part of the garrison for Wallis. General Larsen meanwhile had been directed to organize the 8th Defense Battalion of Tutuila, as the major element of the Wallis garrison. To exercise overall authority, Headquarters Samoan Area Defense Force was established on Tutuila. Major General Charles F. B. Price, who was appointed to this command, arrived with his staff at Pago Pago on 28 April from the States. On 8 May the 3rd Marine Brigade convoy arrived off Apia and General Barrett assumed military command of Western Samoa. At the end of the month, the 8th Defense Battalion (Reinforced) under Colonel Raphael Griffin moved into Wallis.

More than 10,000 Marine ground troops were stationed in the Samoan area by the beginning of June, and reinforcements arrived in a steady flow. Marine air was also well established. General Larsen’s interest and pressure assured that Tutuila’s airfield was ready for use on 17 March, two days before the advance echelon of MAG-13 arrived. The new air group, organized on 1 March at San Diego, was earmarked for Price’s command. Initially the group commander, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J. Walker, Jr., had only one tactical squadron, VMF-111, operating from Tutuila’s airfield, but VMO-151, a scout-bomber squadron, joined in May with the arrival of the 3rd Marine Brigade convoy. The amphibians of the Navy’s VS-1-D14 squadron were also put under Walker’s command and sent forward to operate from Upolu and Wallis while the airfields projected for those islands were rushed to completion by naval construction battalions.

Like the rest of the garrison forces in the South Pacific which were rushed out to plug a gaping hole in Allied defenses, General Price’s defense force was never called upon to conduct the island defense for which it was organized. Samoa might

Map 3: South Pacific

well have become a target for enemy attacks, but the decisive Battle of Midway forced the Japanese to curb their soaring ambition.10 Samoa became a vast advanced combat training camp instead of a battleground. Most of the units coming there after the arrival of the 2nd Brigade drew heavily on the recruit depots for their personnel,11 and for these Marines Samoan duty was an opportunity for learning the fundamentals of teamwork in combat operations. As the need for defense construction was met and the danger of Japanese attacks lessened, Samoa became a staging area through which replacements and reinforcements were funneled to the amphibious offensives in the Solomons.12 Units and individuals paused for a while here and then moved on, more jungle-wise and combat ready, to meet the Japanese.