Chapter 2: ELKTON Underway

Woodlark-Kiriwina1

The planned moves of the Allied forces in the Central Solomons-Papuan area in the summer of 1943 resembled pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Each operation in itself did not represent a serious threat to the enemy’s defense line, but, as part of a bigger picture, each was important and contributed to the success of all. The pieces fitting together formed a pattern of coordinated, steady advance.

D-Day (30 June) for ELKTON was practically a planning date only. ComSoPac operations began at Segi on 21 June; and Woodlark-Kiriwina landings two days later opened the action by Southwest Pacific forces, well in advance of the date set. The near-concurrent start was a coincidence; a two-pronged attack by Halsey and MacArthur had been postponed three times before 30 June as a mutual D-Day was accepted. A number of factors forced the delay, chief among which was the scarcity of amphibious troops required by the missions of ELKTON. The 43rd Division was the early choice as the New Georgia assault force, and that unit was scheduled for extensive ship-to-shore training prior to the operation. In the Southwest Pacific, an entire new command—the VII Amphibious Force (VII PhibFor)—was activated to assemble and train the needed troops.

Marine Corps divisions, whose specialty was such amphibious movements, were not available for assignment to CARTWHEEL operations. Two divisions were undergoing rehabilitation and training; a third was not yet combat-ready; and a fourth was still forming in the States. The result was that Marine raider and defense battalions were at a high premium to augment available Army units for the twin operations of TOENAILS in New Georgia and CHRONICLE at Woodlark-Kiriwina.

A tentative lineup of forces for the planned attacks was made in April. Admiral Halsey made a quick trip to Brisbane on the 18th to meet the general under whom he would be operating, and he and MacArthur quickly came to an agreement based upon mutual respect. MacArthur

needed some help in his amphibious venture; Halsey offered it. He ordered his Noumea headquarters to assign the 20th NCB (Acorn 5) to Brisbane and to select one combat-ready RCT plus one Marine defense battalion for further transfer to SWPA. Assignment of the Marine unit was easy; the 12th Defense Battalion had arrived in Pearl Harbor in early January and was awaiting further transfer. But the many needs of the expanding South Pacific defense area had left few Army regiments without active assignments. It was finally decided, after a musical-chair shuffle of troops, that the 112th Cavalry (dismounted) on New Caledonia would join the 12th Defense Battalion, Acorn 5, and other naval base and service units in a transfer to SWPA. Here they would serve as the Woodlark defense force. Lieutenant General Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army troops would garrison Kiriwina.

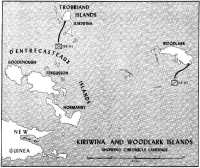

MacArthur’s targets, Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands, lay in the Coral Sea off the southeastern shore of New Guinea, about 60 miles north and east of the D’Entrecasteaux Islands. Kiriwina, in the Trobriand Group, is about 125 miles directly south of New Britain; Woodlark is about 200 miles southwest of Bougainville. Their designation as future airfield sites to support operations in both New Guinea and the Solomons sent Army engineers scrambling over them to obtain beach and terrain information to supplement native reports and aerial photography. The reconnaissance teams were wary, but prior information was correct—the Japanese had not occupied the islands. (See Map 2.)

Kiriwina, shaped like a bent toadstool, was ringed by an extensive coral reef broken by only a few narrow openings for shallow-draft boats. Twenty-five miles in length, and from two to eight miles wide, the island held about 7,500 natives, had a sub-surface coral base which would support an airstrip, and had many good trails for jeep roads. But there were no good beaches. Woodlark, about 100 miles southeast of Kiriwina, was nearly 44 miles long and from 10 to 20 miles in width. Curved in shape, it held a number of good anchorages tucked within the protected shorter arc. The beaches, however, ran inland only a few hundred yards before bumping into a coral cliff. Sparsely settled, Woodlark was covered with a thick jungle growth and dotted with large outcroppings of coral.

Together, these islands could provide bases for fighter escorts of Lieutenant General George C. Kenney’s Allied Air Forces hitting at New Guinea, New Britain, and New Ireland, and for SoPac strikes against the Northern Solomons in subsequent operations. Their capture, the JCS had decided earlier, would provide the first test of the newly formed VII Amphibious Force.

This force had come into being under the direction of Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey, who opened his headquarters at Brisbane in mid-January 1943. By April, it was apparent that the task of forming and training an amphibious force was far more difficult than had been supposed at first. An assortment of United States and Australian ships formed the transport division, and Sixth Army troops, recuperating from the hard fighting in the Buna-Gona campaign, were trained in amphibious operations. Practice landings which were sandwiched between troop lifts to New Guinea were never realistic. Few troops, ships, or pieces of heavy

Map 2: Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands

equipment could be spared from that operation for practice purposes. With an operational deadline pressing, Admiral Barbey scoured the Southwest Pacific for more ships. Some new LSTs were assigned him; others he borrowed from ComSoPac. The USS Rigel, a repair ship with none of the desired command facilities, was pressed into service as a flagship.

MacArthur, in his first conference with Halsey, had tentatively set 15 May as D-Day for the combined operation. Late in April, MacArthur announced that he could not meet this date and directed its postponement to 1 June. It was later changed to 15 June as logistical and shipping problems piled up in the Pacific. On 26 May, the general proposed the 30th of June as D-Day and requested ComSoPac concurrence. This date, MacArthur pointed out, would also coincide with landings by other SWPA forces at Nassau Bay on New Guinea, about 10 miles south of Salamaua. Halsey agreed.

The CHRONICLE forces assembled, Kiriwina’s garrison (code-named BY-PRODUCT) at Milne Bay on New Guinea and Woodlark’s garrison (code-named LEATHERBACK) at Townsville, Australia. On 21 June, nine days ahead of schedule, the advance echelon of the 112th Cavalry, with heavy bulldozers and operators from the 20th NCB, set off for Woodlark. The next night, troops and equipment were landed. The speedup resulted because the troops were ready, there would be no enemy to oppose the landing, and Barbey’s transports would need the extra time to carry two landing forces to their destinations. Kiriwina’s advance echelon was landed on the nights of the 23rd and the 25th, the last group landing across the reef over a coral causeway 300 yards long and 7 feet high which had been built by combat engineers and natives.

The main landing of the Kiriwina force, which included the 158th RCT, the 46th Engineer Combat Company, and antiaircraft artillery and service troops, was made on the night of the 29th according to the ELKTON schedule. Additional Woodlark advance echelons had been landed on the nights of the 25th and 26th, with the main landing of support elements coming on the 30th, also as scheduled. Woodlark’s garrison, in addition to the troops transferred from ComSoPac, included the 404th Engineer Combat Company as well as other service and ordnance troops.

Enemy opposition was neither expected nor received, although a fighter cover of General Kenney’s forces provided assurance of success. The landings at Woodlark proceeded smoothly throughout. With a better area in which to land and with experience gained in a last-minute rehearsal, the LEATHERBACK force went ashore with a minimum of effort. The Kiriwina operation, however, left much to be desired. Lack of prior training and insufficient equipment, complicated by poor landing areas, contributed to the confusion. In addition, the island’s coral circlet made resupply of the island difficult. Regardless of these handicaps, VII PhibFor carried 12,100 troops to Woodlark and 4,700 to Kiriwina without a casualty, while a total of 42,900 tons of supplies and equipment were unloaded without loss of a ship or landing boat.

For the Marine 12th Defense Battalion, the Woodlark landing was anticlimactic. Organized in San Diego in August 1942 under the command of Colonel William H. Harrison, the battalion trained extensively and test-fired all its armament before moving to Pearl Harbor and further combat

training. The battalion joined the LEATHERBACK force in Australia prior to the operation. Two 90-mm antiaircraft batteries went ashore from LCIs on 30 June and the remaining batteries and groups followed them ashore during the next 12 days. The first two 90-mm batteries were ready to fire by 1300 on 1 July, and the other units were in firing positions in equally short order once ashore. But the opportunity for combat firing seldom came. It was not until 27 July that a solitary Japanese plane, after making several false attempts, hurried over Woodlark to drop five small bombs. There was no damage, and the plane escaped. After that, only occasional alerts were noted in the 12th Defense Battalion’s log. Kiriwina, however, was bombed several times during construction with some damage to equipment and installations and some casualties to the BY-PRODUCT troops.

Construction of the airstrip on Woodlark progressed speedily; the Kiriwina field was slowed by heavy rains and the fact that much of the heavy equipment had seen too much prior service and was deadlined for repair within a few days. On 14 July, Woodlark was declared operational with a strip 150 feet wide and 3,000 feet long available. The first fighter squadron from South Pacific forces arrived on 23 July. The runway at Kiriwina was operational in late July, and on 18 August, a Fifth Air Force fighter squadron arrived on station. Kiriwina staged its first strike against enemy forces on New Guinea in late August, and later was a base for a Fifth Air Force fighter group.

No Allied strike was ever staged from Woodlark’s strip, and South Pacific aircraft commanders lost interest almost as soon as it was completed. In fact, after the capture of Munda, Woodlark was turned over to the Fifth Air Force. Kiriwina remained for a time as a fighter plane base, but later the war moved northward toward the Bismarck Archipelago and the Admiralties and left both fields far behind. However, the Woodlark-Kiriwina operation gave needed experience to a new amphibious force and provided a protective buffer to the New Georgia operation which was concurrently underway.

Occupation of Segi and Seizure of Viru2

The man who was to call the shots in the defense of Munda airfield unknowingly tripped the alarm which set the ELKTON plans into action. Major General Sasaki, in his area headquarters at Kolombangara, was irked at Coastwatcher Kennedy at Segi Plantation near Viru Harbor, and—after months of tolerating Kennedy’s presence—determined to get rid of him. Sasaki had good reasons: Kennedy’s station was the center of resistance on New Georgia, and his air raid warning activities had contributed greatly to the lack of success of Japanese strikes against Guadalcanal. On 17 June, Sasaki sent

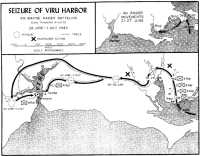

reinforcements to the Viru Harbor garrison with orders “to pacify that area.”3 (See Map 3.)

Prior to Sasaki’s decision to reinforce Viru, Segi Plantation on the southeast coast of New Georgia had been important only to the Allies. Segi was an ideal entryway into the island. Amphibious patrols had landed here, and the plantation had been a haven for many downed aviators. For the new advance, the Allies planned to build an airstrip here, but Kennedy reported on 18 June that he would not be able to hold this position if he did not get help in a hurry. The Japanese were closing in on him.

Admiral Turner ordered an immediate occupation of Segi. If Kennedy said he needed help, he was to be taken at his word. This determined New Zealander, the former District Officer for Santa Isabel Island across The Slot from New Georgia, was no alarmist. He had moved to Segi Point after the Japanese occupied the Solomons and there he had been completely surrounded by enemy garrisons. But he had held on, and his position 160 miles northwest of Lunga Point had fitted in admirably with the system of air raid warnings. His reports on Japanese flights meant that their arrival over Guadalcanal could be forecast within a minute or two. Kennedy had told the natives of New Georgia that Britain was not going to give up these islands, and the success of the Allies at Guadalcanal and Tulagi gave convincing evidence of this. He continued to live almost openly in the plantation house at Segi. There were no trails leading to his station, and the approach along the beach could be watched. But Kennedy and his natives had been forced to ambush Japanese parties to keep the position secret. Some enemy had escaped Kennedy’s attacks, however, and Sasaki had issued the order which made Kennedy the most wanted man on New Georgia.

Already at Viru Harbor was the 4th Company of the 1st Battalion, 229th Regiment, plus a few assorted naval personnel from the Kure 6th and Yokosuka 7th SNLF, a 3-inch coastal gun, four 80-mm guns, eight dual-purpose guns, and a varying number of landing craft. To augment the Viru garrison, Major Masao Hara was to take another infantry company and a machine gun platoon from his 1st Battalion and comb southeastern New Georgia for the coastwatcher’s hideout.4 When this force came close, Kennedy faded into the hills and radioed:

Strong enemy patrol has approached very close, and by their numbers and movement, it is believed they will attack. Urgently suggest force be sent to defend Segi.5

The message reached Turner at Koli Point, Guadalcanal, during the night of 18-19 June, and the admiral decided to send a force to Segi at once rather than wait until 30 June, the D-Day established by ELKTON plans. Fortunately, the admiral had combat units ready. The destroyer-transports Dent, Waters, Schley, and Crosby were standing by in Guadalcanal waters for the operations against New Georgia, and Lieutenant Colonel

Michael S. Currin’s 4th Marine Raider Battalion, which included personnel who had been to New Georgia on prelanding reconnaissance missions, was also completely combat-ready. With these ships and men, Turner could mount out a force to protect Kennedy and also thrust a toe in the Central Solomons door that the Japanese were trying to slam shut.

Currin’s battalion (less Companies N and Q, scheduled to attack Vangunu Island on 30 June) went on board the Dent and Waters on 20 June for a night run to Kennedy’s aid. This force was followed the next night by Companies A and D of the Army’s 103rd Infantry Regiment. Initially, these units would defend Segi, and then carry out the planned attack on Viru Harbor on 30 June as scheduled. With the exception of raider Company O, previously detached to duty with Turner’s Western Force but now returned to Currin, these units were part of Admiral Fort’s Eastern Force and were scheduled for use in this area of New Georgia. Thus the landing at Segi on 21 June, which set off the CARTWHEEL operations, amounted only to stepping up the timetable.

All was not smooth sailing for the Dent and Waters. The natural obstacles which had contributed to Kennedy’s security at Segi Point were hazards for these ships. There is deep, sheltered water off Segi, but the channels to this anchorage were uncharted, dismissed on the charts as “foul ground.” There are so many reefs and coral outcroppings in these waters that Vangunu appears to be almost a part of the larger island of New Georgia. There is no suitable route to Segi from the north, and only the natives and a few local pilots were acquainted with the passages to the south. Even with a local pilot sighting on Kennedy’s bonfire signal on the beach, the transports scraped bottom and rode over reefs. At 0530 on 21 June, the Marines went over the side and into ships’ boats for the landing, and by 1030, all supplies had been brought ashore and the transports were picking their way through the coral heads and reefs for a speedy return to Guadalcanal. Currin immediately established defensive positions and sent out patrols, but there was no contact with the enemy. At 0600 on the following day, the two Army companies plus an airfield survey party from Acorn 7 came ashore from the Schley and Crosby.

Kennedy was grateful that these troops had come to his rescue, but both his pioneer spirit and his scouting routine were pinched by this population influx. For peace and quiet, and to re-establish a schedule of unrestricted movements for his native scouts, he moved across the narrow channel to Vangunu Island. Currin kept contact with the coastwatcher, and, with natives provided by Kennedy, sent out patrols to determine the most suitable means of approach to Viru Harbor. At the same time, Seabees began converting Segi’s uneven and muddy terrain into an airstrip. With bulldozers and power shovels, working at night under floodlights, the men had an airstrip ready for limited operations as a fighter base by 10 July. It was the intentions of ComSoPac to have the field capable of servicing 20 planes an hour at first, and then—by 25 September—of basing about 60 light bombers.6

Burial ceremony at Viru Harbor honors Marines of the 4th Raider Battalion killed in the first American offensive on New Georgia. (USMC 57581)

155-mm guns of the 9th Defense Battalion on board an LCT off Rendova’s beach as they move to a new firing position. (USMC 60658)

The Allies had plans for Viru Harbor, too. This small, landlocked cove 35 miles from Munda was to be developed into a minor naval base for small craft. The best anchorage on the New Georgia coast, it had an entrance 300 yards wide and 800 yards long, outlined on both sides by coral cliffs. The inner harbor widened, and was fed by three small rivers, the Mango, Tita, and Viru. Previous amphibious patrols had reported the bulk of the Viru defenders to be located on the high headlands on the west side of the harbor at the village Tetemara, with another detachment at Tombe, a village facing Tetemara across the channel. But intelligence reports on the size of the Viru garrison conflicted. Early estimates had ranged from 20 to 100 men; an early-June reconnaissance patrol revised these figures to 200 enemy troops. (See Map 3.)

As Companies A and D of the 103rd set up a defense against any further attempts by the Japanese to wipe out Kennedy’s station, raider amphibious reconnaissance teams concentrated their attention on finding the most suitable route to Viru. Several times they narrowly missed bumping into Japanese patrols or sentries as the Marines examined a number of small river inlets searching for a beach which would exit to an overland route to the rear of Viru Harbor. While Currin’s raiders scouted the area between Segi and the proposed landing site, a member of the staff, Captain Foster C. LaHue, slipped by native canoe through the bay to Hele Islands in Blanche Channel to meet the Schley and receive Admiral Fort’s orders for the Marines’ attack on Viru.

Currin had hoped to land during the night of 27 June at Regi, a village just seven miles from Viru Harbor and considerably west of Segi Plantation. From here his force could move overland to a point east of the Viru River, and there split for attacks down both sides of the inlet to seize the village of Tombe on the east bank and Tetemara on the west. Fort’s orders, however, directed only Company P to land on the 28th at Nono village, just a few miles west of Kennedy’s station. Currin was then to strike through the jungle to attack Tetemara at 0700 on 30 June, and capture the seacoast guns reported to be in Tetemara. The APDs Kilty and Crosby would then sail into the harbor and put ashore a 355-man occupation force consisting of Company B of the 103rd; one-half of Company D, 20th NCB; Battery E (less one platoon) of the 70th Coast Artillery (Antiaircraft) Battalion; and a naval base unit.

Additional paragraphs of the order gave details concerning the proposed seizure of Wickham Anchorage and the development of Segi Point, but contained no instructions for Company O of the Raiders and that portion of the 4th Raider Battalion headquarters already at Segi.7 At 1600 that afternoon, Colonel Currin radioed Admiral Fort for permission to land at Regi, to use Company O as well as Company P, and to begin the operation on 27 June rather than 28 June. The raider commander had spent 20 days in this area with amphibious patrols during March and April, and he estimated that even if he started a day earlier he would be hard-pressed to make the D-Day of 30 June at Tombe and Tetemara. An overland trek would mean tortuous trails over ridges, rivers, and swamps, and the hiking distance was considerably more than map

Map 3: Seizure of Viru Harbor, 28 June–1 July 1943

miles. Besides, the distance in miles was not a realistic indication of the problems the Marines faced in the thick jungle. Currin knew the job would be much too tough for a single company. The enemy situation had changed since Admiral Fort’s plans were made, and there was now a larger Japanese force in the Viru area with patrols active at Nono. Currin felt that if his men landed in their rubber boats at Nono they would be “sitting ducks” for the Japanese.8 Within an hour and a half, Admiral Fort had radioed his approval of the modified plan.

At 2000 on 27 June, the Marines boarded their rubber boats and started paddling the eight miles to Regi, Currin and his staff leading the way in two large Melanesian war canoes. As one Marine described the trip:–

It was a weird moonless night with black rubber boats on black water slipping silently through the many islands of Panga Bay. The trip was uneventful except for one scare. It came just before reaching Regi, while lying offshore waiting for word from native scouts who had gone ahead to make certain no Japanese were in the village. Due to the sudden appearance of a half moon which began to cast a sickly reflection, a small island appeared to be an enemy destroyer.9

The scouts came back with an “all clear,” and, by 0100, all hands were ashore, and the rubber boats were being towed back to Segi by natives in the war canoes. At dawn, the battalion followed the scouts into the jungle with Company O in the advance guard followed by the headquarters group, and with Company P furnishing the rear guard.

There were many signs of Japanese patrols, but they indicated small scouting parties rather than forces large enough to offer determined opposition. Currin instructed his Marines to meet Japanese harassment with forces no larger than absolutely necessary so that the main column could continue to advance. The Marines would have to fight against time if they were to reach Viru Harbor on schedule and silence the Japanese coastal guns before Admiral Fort’s landing forces entered the harbor.

The Marines’ battle against the New Georgia jungle began just outside Regi where the force encountered a mangrove swamp two miles wide. There was no suitable way to skirt this obstacle, so the column struck out through it. The first enemy contact was a five-man patrol that came in off a side trail and apparently surprised itself as well as the Marines by stumbling into the rear party of the raider battalion. The 3rd Platoon of Company P killed four of these men in a brief skirmish before resuming the march with the rest of the column. At 1115 another enemy group hit the rear guard, and five Marines at the end of the column were cut off from the main body as Company P drove these Japanese off with rifle and machine gun fire. The five men, evading the Japanese but unable to catch up with the column, returned to the landing site and paddled back to Segi in a native canoe they found on the beach.

In all, the force made about six miles the first day. The terrain grew more difficult as the Marines moved deeper inland, and the advance became more of an up-and-down climb than a march. The raiders bivouacked in a tight perimeter, ate their K rations, and huddled under their ponchos throughout the rainy night. Realizing that the slow going would keep him from making his assault on schedule,

Currin sent two native runners back to Segi with a message for Admiral Fort that the raiders would be a day late in reaching Viru. Kennedy had trouble contacting the Russell Islands, and when this message got through, the landing force was already underway toward Viru Harbor.

On the second day, Currin’s force covered seven miles of the difficult terrain, and was forced to make three crossings of the meandering Choi River, now swollen and swift from the heavy tropical rains. At about 1400, just as the rear guard completed its first crossing of the Choi, it drew fire from 30 to 40 Japanese in positions on the right flank of the advance. Captain Anthony Walker, commanding Company P, sent First Lieutenant Devillo W. Brown with a reinforced platoon of 60 men to deal with this enemy force. The Marines located the enemy dug in on the crest of a hill some 300 yards from the trail. The raiders wasted no time. With one squad in position for covering fire, the other two squads went up the ridge by infiltration, firing as they climbed. Eighteen enemy dead were found, but five raiders had been killed and another wounded in the attack.

Burying their dead and carrying the wounded man, Brown’s men pushed on to catch Currin’s column. The battalion crossed the Choi River again, skirted a large swamp, and then halted for the night just after crossing the Choi for the third time. There Lieutenant Brown and his platoon rejoined the battalion. Colonel Currin tried to report his position to Guadalcanal, but his radio failed him. The battalion commander could only hope that the message he had sent via runner and Kennedy during the previous night would keep the transports from sailing into range of the enemy’s 3-inch coastal gun before the raiders could get to Viru and silence that weapon.

As Currin’s force moved out on the morning of 30 June with a full day’s march remaining between it and its objective, Commander Stanley Leith’s Viru Occupation Unit in the Hopkins, Kilty, and Crosby edged toward Viru Harbor and the Japanese gun which Currin’s force was to have silenced. Leith, however, had received roundabout word that Currin was going to be a day late in his attack at Viru. Remaining close by in case the Marines were in trouble, the APDs at 0730 came within range of the enemy’s 3-inch gun, and the shells began splashing all around the ships.

Leith withdrew to the harbor mouth, where he steamed back and forth until 1000. Then, with Admiral Fort’s approval, he withdrew from Viru area and the next day put the landing force ashore at Nono. These troops, under the command of Captain Raymond E. Kinch of Company B, 103rd Infantry, would go overland to Viru, as Currin was doing. From Viru, Major Hara reported to General Sasaki at Munda Point that he had repulsed an attempted American landing.10

Early on 30 June, the raider battalion reached the trail fork from which one route extended south toward Tombe. Currin had planned to send one platoon against Tombe. The enemy opposition of the previous days, however, and the fact

that enemy patrols working the jungle between Viru and Segi Point could reinforce this village more quickly than they could Tetemara, prompted Currin to increase the size of the force attacking the east side of the harbor. Two platoons from Company P (Lieutenants Brown and Robert J. Popelka) with Captain Walker in command were assigned this mission. The attack at Tombe would be made independently of the assault at Tetemara.

Currin moved on toward Tetemara with a smaller force than he had originally intended. For the men with Currin, this day’s march was the worst yet. They met no enemy, but by mid-morning had to ford the Viru River and then struggle through mountainous terrain—rugged jungle ridges along the course of the Tita River which they crossed later in the day. Going was slow for the men weighted down with arms, equipment, and ammunition, and there was but an hour of daylight remaining when they came out of the bush on the bank of the Mango River. Fifty yards wide, deep and swift, the Mango was a formidable obstacle. But the Marines clasped hands and moved out, the human chain snaking the force across the river.

Beyond the Mango, the Marines were caught by darkness and a mangrove swamp. Water, knee-to-waist-deep, hiding twisted, snakelike roots under the surface, trapped the raiders. In a matter of minutes, the column was stalled as men fought to keep contact with each other. However, “tree-light”—phosphorescent wood from dead logs and trees—was provided by the native guides and re-established contact. With each man carrying a piece of this dimly glowing wood, and guiding on the piece carried by the man ahead, the column closed up and moved out. Four hours later, the Marines were out of the swamp and facing the last half-mile of steep slope to the rear of Tetemara Village. Weary raiders struggled up the slick and muddy trail, falling exhausted at the top of the ridge after crawling on their hands and knees the last 100 yards of nearly vertical slope.

On the east side of Viru, Walker’s force bivouacked a short distance from Tombe, and at 0900 on the morning of 1 July launched its attack. The surprise assault killed 13 Japanese, scattered the remainder of the small garrison, and carried the position at no loss to the raiders. The firing aroused the enemy across the harbor at Tetemara. When they rushed out in the open, they were bombed and strafed by six planes from VMSB-132 and VB-11. The strike had been requested by the air liaison party at Segi and approved by General Mulcahy in his headquarters at Rendova. It was the first strike logged in the new records of ComAir New Georgia.11

Currin’s force, moving along the high ground overlooking Tetemara, heard the explosions and firing during the air strike, but the jungle screened the planes from view.12 Fifteen minutes later, Currin attacked the village. With First Lieutenant Raymond L. Luckel’s Company O in the lead, the raiders moved down the slope, then fanned out in an attempt to confine the Japanese to an area bordered by the harbor and the sea. Luckel’s machine guns were attached to his assault platoons, and with the help of this additional firepower the advance continued slowly. A few outguard

positions were overrun before the Marines were forced to halt under steady fire from the enemy’s main line of defense.

Advance was slow and sporadic, with long periods of silence broken abruptly by a series of short, sharp fire fights lasting only a few minutes each. In an hour, the Marines had gained about 100 yards. Deciding that a buildup for an envelopment around his left flank was developing, Luckel committed his 3rd Platoon to that flank, and the advance continued. By 1305, the Marines had reached a low crest of ground from which the terrain sloped away toward Tetemara.

The bottled-up enemy, realizing their predicament, began withdrawing toward the northeast with much frantic yelling. Anticipating a banzai charge in an attempt to break through the Marine’s left flank, Currin dispatched his slim battalion reserve of the 3rd Platoon and two sections of machine guns from Company P to the aid of Company O. The reinforcements arrived just in time. In a matter of minutes, the hopeless rush of the enemy was broken, and the Marines began to move forward against spotty resistance. The 3-inch gun was captured, Tetemara occupied, and the few remaining Japanese flushed out of caves and jungle hiding places. Currin’s force counted 48 enemy dead, and captured, in addition to the 3-inch gun, the four 80-mm guns and eight dual-purpose guns of the Viru garrison, as well as 16 machine guns, food, clothing, ammunition, and small-boat supplies. Eight Marines were killed in the attack.

Even while the fighting was in progress, three LCTs sailed into the harbor with gasoline, oil, and ammunition for the proposed naval base. They remained safely offshore until Tetemara was secured, and then came in to drop their ramps and unload. Three days later, on 4 July, Company B of the 103rd Infantry struggled into Tombe after an enervating march overland from Nono. On 10 July, after a new garrison force came in to hold and develop the Viru area, the raiders returned to their old camp at Guadalcanal.13 Seizure of Viru had cost the battalion 13 killed and 15 wounded out of an original force of 375 officers and men.

Major Hara’s Viru garrison force lost a total of 61 killed and an estimated 100 wounded in the defense of Tombe and Tetemara. Another estimated 170 escaped into the jungle. Hara’s force, under orders from the Southeast Detachment to return to Munda, marched over the rugged jungle trails and reached the airfield about 19 July, just in time to take part in the final defense of that area.14

Securing Vangunu15

Another side show to the main New Georgia landing in the Munda area was

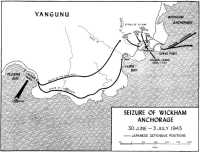

the taking of Vangunu Island for the purpose of establishing a base along the supply route between the lower Solomons and the main target area. Pre-landing reconnaissance revealed that the island would not be suitable for airfield construction as planned earlier. It could be taken with a relatively small force, however, because it was not heavily defended. Thus, it would be an economical prize for the Allies with the promise of a useful way station at Wickham Anchorage, a sheltered harbor tucked behind coral reefs between Vangunu and neighboring Gatukai Island to the east. (See Map 4.)

An amphibious scouting party sent to Vangunu in mid-June radioed Admiral Turner’s headquarters on the 20th, confirming reports that the Japanese had not reinforced the island and that beaches at Oloana Bay on the south side of the island could accommodate the landing of a reinforced battalion. Admiral Fort was then directed to occupy the island with a small force on 30 June. His D-Day landing would not be a complete surprise. Japanese sentries spotted the amphibious patrol and reported “enemy surface forces” in the Wickham area; all units were cautioned to be on the alert.16

As his landing force, Fort selected Lieutenant Colonel Lester E. Brown’s 2nd Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment; Battery B (90-mm), 70th Coast Artillery (Antiaircraft) Battalion; and half of the 20th NCB. To augment Brown’s soldiers, Admiral Fort also assigned that portion of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion which had not gone to Segi Point and Viru Harbor under Lieutenant Colonel Currin. The raider battalion’s executive officer, Major James R. Clark, commanded these units which included Company N (Captain Earle O. Snell, Jr.), Company Q (Captain William L. Flake), a demolitions platoon, and a headquarters detachment. For added firepower, Battery B (105-mm howitzers) of the 152nd Field Artillery Battalion, and a special weapons group from Battery E (40-mm and .50 caliber antiaircraft guns) of the 70th Coast Artillery Battalion were added to the Wickham Anchorage force.

The plan called for the Marines to land before dawn at Oloana Bay from APDs Schley and McKean, contact the scouting party still on Vangunu, and establish a beachhead. A first echelon of Army troops would land over this beach 30 minutes later from seven LCIs, followed by a second and final echelon of Army troops landing from seven LSTs at 1000. From Oloana Bay, Brown’s force would move inland to widen the beachhead line while Company E, 103rd Infantry, reinforced with the battalion’s 81-mm mortars, skirted along the beach eastward toward Vura Bay, reported as the main enemy base. Native scouts operating from the base of coastwatcher Kennedy near Segi Point had reported that there were approximately 100 Japanese at this point.

After a rendezvous at Purvis Bay off Florida Island, Fort’s transports sailed north beyond the Russell Islands and reached the debarkation area off Oloana Bay at 0230 on 30 June. The scouts had placed markers on the beach and were showing a signal light, but the ships arrived in the midst of such a heavy downpour that these aids could not be spotted. High winds put a bothersome chop on the sea, and the APDs and landing craft pitched and tossed as the Marines groped

their way over the side to prepare for the “blind” landing. The best radar in the task force was an old model in Admiral Fort’s flagship, the destroyer-minesweeper Trever, but it was not able to fix the position of the force accurately in relation to the beach.

Admiral Fort called off the landing until the weather cleared, or until dawn when the beach could be seen, but the APDs either did not receive or misunderstood these orders and went ahead with the landing. The whole operation became a classic example of how not to land troops on a hostile beach. At 0345, while in the midst of debarkation, the APD commanders decided that their ships had not been correctly positioned, so they moved 1,000 yards to the east and continued the operation. The move added to the confusion, since it forced the landing craft to cross paths with the seven LCIs, resulting in thorough dispersion of the landing craft just as they were heading toward the beach. Regaining contact proved impossible and the coxswains had to do the best they could on their own. Not having been given anything but a general course to the beach, they landed in widely separated spots along seven miles of the Vangunu coast. Six boats, but no men, were lost in the pounding surf.17

Two boats carrying the 1st and 2nd Platoons of Company Q managed to stay together, but they headed in the wrong direction and finally grounded on a reef approximately seven miles west of Oloana Bay. The craft which contained Second Lieutenant James E. Brown’s 1st Platoon managed to clear the reef, but in doing so lost its rudder. Marines tied buckets to the ends of lines and then guided the boat by trailing these buckets astern and pulling on the lines like reins. The boat carrying Second Lieutenant Eric S. Holmgrain’s 2nd Platoon broached to in the surf on the reef. Holmgrain and his men waded and swam nearly two miles to shore and set up a local defense until dawn. Brown remained just off shore with his platoon boated. The next morning, Holmgrain hiked his platoon along the beach toward Oloana Bay while Brown steered along the coast with his buckets. The McKean spotted this craft and sent out a sound boat in which Brown finished his trip.

The other scattered Marines met no opposition and were able to regroup at Oloana Bay. There the first waves of soldiers landed in calmer seas at 0700, followed by the remainder of the force within an hour. The amphibious scouts reported to Colonel Brown that the Japanese garrison was not at Vura as expected, but was instead occupying Kaeruka, a small village about 1,000 yards northeast of Vura Bay on another coastal indentation. Colonel Brown immediately issued new orders, designating the mouth of the Kaeruka River as the objective, and just before 0800, the drenched force moved out. Company E retained its original mission of capturing Vura village. There this force would hold up and prepare to give mortar support to the other units attacking

Map 4: Seizure of Wickham Anchorage, 30 June–3 July 1943

Kaeruka. Companies F and G of the 103rd, along with Marine units and eight native guides, would swing inland along a coastwatcher trail, which it was believed had not been discovered by the Japanese, and assemble on high ground some seven miles from the beachhead. This hilly terrain would give the attackers an attack line of departure just east of the Kaeruka River and 700 yards from the village where the Japanese were camped. Artillerymen and Seabees would hold the beachhead at Oloana.

At Vura village, Company E met 16 enemy armed with two light machine guns, but the mortars quickly knocked out this opposition. The company then prepared to support the other attacking force which had to deal with a more difficult march and stronger enemy defenses.

The driving rain had turned the coastwatcher trail to slick mud and the Vura and Kaeruka Rivers into shoulder-deep torrents. Swimmers strung ropes across these streams and the Marines and soldiers then managed to cross, each man pulling himself along the ropes. Brown’s force finally reached its line of departure at 1320. By this time all scattered Marine units, including the two platoons which grounded on the reef seven miles from the landing beach, had rejoined their parent companies, much to the gratification of Colonel Brown:–

This in itself was a considerable feat because some of the landing boats had gone ashore far down the coast ... and the Marines were all heavily laden with weapons and ammunition.18

The attack jumped off without preparatory fires. The rain had put all radios out of commission, and Colonel Brown could not contact either Vura for mortar fire or Oloana Bay for artillery support. The Marines, commanded by Major Clark, and the soldiers moved south from their line of departure at 1405. On the right, Company Q (raiders) guided on the meandering Kaeruka River with orders to cross the river farther south to turn the left flank of the enemy. Company N (raiders) in the center drove straight towards the Japanese; and on the left, Company F of the 103rd Infantry moved to position for a partial envelopment of the Japanese right. The 103d’s Company G, in reserve, stood ready to exploit any weakness in the Japanese defenses and to protect the American flanks.

Off Company Q’s right, the Kaeruka River made a 300-yard loop to the east before turning south again to flow 300 or 400 yards into the sea. This long bend in the river partially enclosed the Japanese camp on the coast and made the stream, in effect, a major obstacle facing the Marine companies. Fifteen minutes after the Marines moved from their line of departure, Company Q began to draw fire from enemy riflemen hidden in trees and camouflaged spider traps.19 As the Marines deployed, they met heavier fire from Japanese positions across the river. At 1445, Major Clark told his raider companies to cross the river, reduce the opposition, and then attack the main enemy positions.

Marines of Company Q struggled down the slippery bank of the river, crossed over and climbed the other side. But the Japanese concentrated so much rifle and machine gun fire on the crossing site that only

one squad of Company N managed to cross before the attack was called off. Contact between the soldiers and Marines was now broken, and while the two Marine companies attempted to tie together, patrols were sent out to re-establish contact with the Army companies.

On the left, soldiers of Company F tried to envelop the right of several Japanese machine guns which they encountered shortly after starting the attack. This maneuver further broke contact between the soldiers and Company N. Colonel Brown then sent Company G to fill the gap. The reserve company moved almost directly south toward the beach meeting only scattered opposition. Although both flanks of the American advance had lost contact with the center unit, this unhandy tactical maneuver split the Japanese force. As Company G moved through the gap between Companies N and F and reached the beach, it placed itself squarely in the enemy rear, and the Japanese opposing the Marines and Company F gave way in disorder.

Resistance in front of Company Q faded, and Company N moved up quickly through the jungle to exploit the confusion of the enemy and drive them to the southwest. The Marine companies, one on each side of the river, then pressed on to the beach below the village of Kaeruka. The soldiers of Company F also reduced the opposition facing them, reaching the beach shortly thereafter. Twelve Marines were killed in the action and 21 wounded; Army casualties numbered 10 killed and 22 wounded. One hundred and twenty Japanese dead were counted.

As Colonel Brown displaced his command post forward from the line of departure, Major Clark established a perimeter defense along the beach east of the river. Company G, the raider demolition platoon, and Company Q dug in facing seaward. Company N tied in on Company Q’s right flank extending inland along the east bank of the Kaeruka River. Soldiers of Company F closed the perimeter with a line which faced inland. Patrols were set out to mop up any bypassed enemy, but darkness forced these men back to the perimeter before any contact could be made. Intermittent enemy mortar fire exploded inside the perimeter and along the beach during the early part of the night, and Japanese machine guns harassed the northern portions of the perimeter, but no attempt at penetration was made.

At about 0200, the American force hit a jackpot. Defenders reported three enemy barges approaching the beach. This was evidently a supply run, bringing food and reinforcements to a Japanese garrison which no longer existed. As the barges moved out of the darkness toward the beach area near the junction of the demolitions platoon and Company G, they met an overwhelming reception. A concerted burst of rifle and machine gun fire set the three barges foundering and drifting out of control. The Japanese called out, evidently believing they were being fired upon by friends, and for a time did not return the fire. The barges continued to drift toward the beach, and Company Q added rifle grenades to the small-arms fire that the other units along the beach directed into the landing craft. The Japanese finally returned the fire, and a few enemy soldiers jumped overboard and splashed ashore. The demolitions platoon killed these with hand grenades. One barge sank offshore and the others broached to in the surf. The fight was over in half an hour, and 109 of an

estimated 120 Japanese were dead.20 Two Marines and one soldier were killed.

The choice of beach defense, made in half darkness, without the aid of maps, was particularly fortunate. Unknown to Major Clark, the beach was the only possible landing point in the entire area; and an unsuspecting enemy had picked that night to resupply and reinforce his garrison. The Japanese “had walked blindly into a hornet’s nest. For the Marines, it was like filling an inside straight.”21

The next morning (1 July) patrols searched for the remnants of the Japanese garrison and learned that the main group of Japanese survivors was digging in at Cheke Point, a bulge of shoreline about 500 yards east of the Kaeruka River. Despite the success of the defense the night before, Colonel Brown marched his force back toward Vura village since he considered it a more suitable defensive area and his troops could be more easily supplied. Moreover, Cheke Point was readily identifiable from the air, and artillery fire from Oloana Bay coupled with air strikes could neutralize the position with considerable saving of lives. A few Japanese harassed the column with long-range fire from machine guns and a 37-mm gun, inflicting some casualties, but the enemy made no organized counterattack.

From a new perimeter at Vura, Brown sent out patrols and organized a coordinated attack on Cheke Point. By this time, with the help of Seabees, the 105-mm howitzers of the 152nd Field Artillery Battalion were in position, and after registering on Cheke Point, fired all day 2 July. In the afternoon, Admiral Fort’s flagship added naval gunfire to the pounding. On the morning of the 3rd, 18 SBDs from ComAir New Georgia staged a strike on Cheke Point while Brown’s force moved forward. Kaeruka was reoccupied without a shot and even Cheke Point was taken with little opposition since the bombardments had forced the Japanese to evacuate the area. Brown’s attack killed seven Japanese and destroyed supply and ammunition dumps which had been overlooked earlier.

On 4 July, the Marines, detached from Colonel Brown’s force, went back to Oloana Bay on LCIs. There they rested until 8 July when they were sent across to Gatukai Island east of Vangunu to look for some 50 to 100 enemy troops which natives reported were holding that small island. The Marines patrolled Gatukai for two days but did not locate any Japanese, although bivouac areas attested to recent occupation. After one night back at Oloana Bay, the Marines returned to Guadalcanal on 12 July to rejoin the remainder of the battalion which Colonel Currin had just brought back from the operation at Segi Point and Viru Harbor. Casualties within Major Clark’s original force of 18 officers and 350 men totaled 14 dead and 26 wounded.

Beachhead at Rendova22

Allied occupation of Segi on 21 June provided the clincher to a Japanese error in judgment. The New Georgia defenders were set to repel an invasion; night and day Allied radio traffic and reports of a troop and transport buildup in the Guadalcanal area had convinced them that an attack was imminent. To intercept such a move, the Japanese assembled their air attack forces at Buin and deployed to defend the Central Solomons. Then, when the occupation of Segi occurred without further immediate buildup, the enemy was positive that the operation was only a limited infiltration, and that the abrupt decline of radio traffic meant a curtailment of further plans. On 26 June the air fleet was ordered to return to Rabaul.

This strategy backfired. A Japanese submarine spotted Turner’s task force near Gatukai on the night of the 29th, but, before the Japanese could determine the significance of the submarine’s report, Vila and Buin were rocked by naval bombardments and Turner’s force was dropping anchor in Rendova Bay. The attacks at Vila and Buin were a diversion only, planned to place striking units in position to protect the Rendova landing. The bombardments were conducted in a driving rain which shielded the retirement of the cruisers and destroyers. Unfortunately, the poor weather also cancelled a Fifth Air Force strike at Rabaul which was supposed to cripple further the Japanese potential to lash back at the New Georgia landings.

The Rendova operation cast the Japanese command in the role of a poor second-guesser:–

The next enemy counter-offensive was estimated in various ways and a series of measures was taken to meet the situation. However, we hardly anticipated that the enemy would first occupy the small islands across from Munda at the time of the invasion of Munda and that they would proceed with their operations under the cover of heavy guns on these islands. Therefore, the landing on Rendova Island completely baffled our forces.23

For the Rendova-bound attackers, the movement from Guadalcanal was uneventful. The task force streamed north from Koli Point at 1545 on the 29th. Screened by destroyers, the six transports and two APDs sailed in a double column north of the Russells before turning west and then northwest again to head up Blanche Channel. Shortly before dawn, the same weather front which shielded the bombardment

forces covered the invasion fleet, and troops aboard the transports had only hazy glimpses of the rain-drenched volcanic peak which identified Rendova. (See Map II, Map Section.)

The invasion site was on the north end of Rendova, a haunch-shaped island nearly 20 miles long and 8 miles wide. Mountainous and densely wooded, Rendova was a fitting counterpart to the other islands in the group. Few of the marshy beaches along its otherwise irregular, steep coastline could be used as landing sites, and most of the shoreline was fouled by coral patches. The island’s best anchorage was Rendova Harbor, a cove three-fourths of a mile wide and one and one-half miles long, protected by a barrier of three small islands. The cove had two deep-water entrances and prelanding reconnaissance teams had designated the eastern of the two as the funnel for the ship-to-shore landing movement.

While the escorting destroyers took up their screening positions—the Jenkins, Gwin, Radford, Buchanan, and Farenholt echeloned at 1,000 yard intervals to the northwest and the McCalla, Ralph Talbot, and Woodworth blocking Blanche Channel to the east—the transports began unloading. Troops from the McCawley, Algorab, Libra, and President Adams were to land on the east beach of the cove; the troops from the President Hayes and President Jackson would go ashore on the west beach.

At 0640, only minutes after arriving at debarking stations, the transports had landing craft lowered and headed toward the beach 3,000 yards away. Through the slot between the offshore islets, the boated troops could see Rendova Mountain and the relatively flat area of the Lever Brothers plantation at its foot which was the landing area. There was some momentary confusion as the flood of boats hit the entrance; but quickly forming into columns, the landing craft plowed on toward shore. As the boats scraped to a halt, disorganized enemy machine gun and rifle fire from the plantation area greeted the disembarking troops.

This was the first indication that plans had been fouled-up. Companies C and G of the 172nd Infantry, scout troops called “Barracudas,” were supposed to have landed from the APDs Dent and Waters an hour earlier, secured the beachhead, and then provided a covering force for the first wave of troops. The enemy resistance, obviously, was evidence that the beachhead had not been taken. The Barracudas, missing the rain-obscured beacon fires, had drifted some 10 miles down the Rendova coast before landing. Then, realizing that they had missed the designated beach, they reembarked and headed upshore toward the cove. They arrived in time to land unopposed over a beach secured by soldiers of the 103rd, Seabees of the 24th NCB, and Marines of the 9th Defense Battalion.

The amphibious maneuver was not a classic. The beachhead had not been expanded beyond 15 yards or so, and in this confined space, soldiers, Seabees, and Marines milled about in the midst of a growing mountain of supplies. Only the first wave had been coordinated. After that, eager coxswains rushed back to the transports for additional loads, and the ship-to-shore movement became an uncontrolled race. To add to the confusion, an occasional enemy machine gunner would spray the landing area from the interior of the plantation, drawing in return a flurry of uncontrolled shots from riflemen on shore

and automatic weapons from the landing craft. Eventually, combat patrols were organized, and soldiers of the 103rd and 172nd began to push inland in skirmish lines, flushing snipers and hidden machine gun nests.

The landing area had not been defended in any great force.24 Sporadic and desultory fire had been the enemy’s only resistance to the invasion. Although warned earlier of the possibility of a landing, the Rendova garrison had gone back to sleep and awoke to find an invasion fleet in its front yard. Too late to defend the harbor in force, most of the garrison fled to the hills to escape later to Munda by canoe. Wet batteries silenced the enemy radios, and contact with Munda could not be made. The first warning the airfield defenders had of the invasion across the channel was a message flashed by lights and flares from a lookout station on a promontory south of the harbor. After inflicting nine casualties, including a face wound to the commander of the 172nd Infantry, Colonel David N. M. Ross, the Japanese defenders finally fled the plantation area, leaving 65 dead behind.

The end of ground resistance marked the end of enemy efforts to dislodge the invasion force until the air fleets at Rabaul could get into action. General Sasaki at Munda could offer only slight opposition. Intermittent shellfire began to register in the transport area and around the destroyers shortly after the invasion was launched, but only the Gwin was hit. Two veterans of Guadalcanal sea action, the Buchanan and the Farenholt, took up the challenge and fired shells back at suspected points, meanwhile changing direction and speed so that the Japanese batteries could not register on them. It was estimated that seven guns were silenced, but the destroyer screen and the Japanese continued the sporadic exchange throughout the unloading activities.

It was a frustrating experience for the Munda defenders:–

Because of insufficient preparations and installations, our naval guns could not engage the enemy. Because of the range, the mountain guns were not able to fire against the enemy. Therefore, our unit was in the predicament that the enemy landed in broad daylight while our unit watched helplessly.25

While soldiers of the 103rd and 172nd pressed inland against spotty resistance, the establishment of a base of operations began in the continual downpour of rain. Unenthusiastic infantrymen were organized as working parties to sort and disperse the jumbled piles of ammunition, rations, lubricants, and other materials. The mushrooming dumps of supplies accentuated the fact that an insufficient beach control party and working party had been provided, and that too high a priority had been given to barracks bags,

officers’ locker boxes, tents, chairs, and other personal comfort items.26

As the unloading continued, cargo-staging areas turned into seas of mud through which trucks churned and skidded. The road through the plantation area soon became a quagmire which caught and held all wheeled vehicles. Tractors were required to extricate them. Culverts, which had been judged strong enough to support heavy traffic, crumbled under the weight of loaded trucks and increased the difficulty of movement. Finally, only the wide-tread prime movers, the amphibian tractors of the 9th Defense Battalion, and the bigger tractors of the Seabees could plow through the mud. All other vehicles stalled, and infantrymen had to hand-carry most supplies to designated dumps, bivouac areas, and gun positions.

Tank lighters were unloaded by soldiers wading through 50 feet of knee-deep water. Later unloading proceeded faster after bulldozers pushed ramps of coral out to the lighters. Cargo was finally shunted to offshore islands in an effort to relieve the congestion, and, with virtually every truck mired down, a message was sent to the ships to delay sending in more vehicles. The mud, however, had convinced observers that future scouting of landing beaches would include engineer as well as tactical reconnaissance.

With the landing well underway, 32 fighter planes from ComAirSols appeared overhead, and troops on the beach and sailors on the ships breathed easier. Their concern was well-founded. Because of the poor weather, General Kenney’s Fifth Air Force had been able to hit Rabaul with only 25 bombers in the 5 days prior to the landing, and the Japanese were still able to launch a powerful counterpunch through the air from Rabaul, Buin, Ballale, and Kahili airfields. It was not long in coming. The Eleventh Air Fleet at Rabaul dispatched a strike of 26 medium bombers and 8 carrier bombers shortly after dawn. Picking up a fighter escort of 72 planes at Bougainville, the flights swept down on Rendova. Intercepted by the Allied fighter cover, the enemy formations were forced away from the landing area, but in their reckless attempts to strike a crippling blow to the invasion, the Japanese lost 18 bombers and 31 fighters. Two hours of valuable unloading time, however, had been lost by the ships maneuvering to escape the enemy bombing runs.

At 1505, with all the troops unloaded and most of the supplies on the beach, Admiral Turner decided that the attack force had stretched its luck long enough and ordered the return to Guadalcanal. As the ships headed down Blanche Channel, a flight of about 50 Japanese fighters and torpedo bombers swung in over Munda Point and started bombing and strafing runs. The Farenholt dodged two torpedos before being bumped by a third—a dud; the McCalla was bracketed front and rear while a third torpedo plunged under the ship. The McCawley was not as lucky. A solid hit amidships opened a gaping hole, and Turner’s flagship came to a dead halt. The admiral transferred his flag to the Farenholt, and the Libra took the McCawley under tow. After surviving

another attack by 15 dive bombers, the McCawley continued to settle and was abandoned. That night, three more torpedos slammed into the transport and it sank. Believed the victim of an enemy submarine, the McCawley actually was sunk by an American MTB which had mistaken her for an enemy ship.

The day’s air action cost the Japanese heavily. Determined to stop the invasion, the Eleventh Air Fleet flooded the skies with every type of plane available. Despite the waiting interceptors of ComAirSols, the Japanese plunged recklessly toward Rendova. Fighter protection for the bombers was insufficient, however, and each attack resulted in scores of flaming crashes. Claimed kills in the one morning and two afternoon raids totaled 101 enemy planes; Marine squadrons (VMF121, -122, -213, and -221) reported downing 58 of them. The Allies lost 17 planes, but 8 pilots were fished out of the water by PBYs and torpedo boats. In addition, ComAirSols hit Vila with 16 torpedo bombers and 12 scout bombers in a morning strike, and then bombed Munda with an afternoon strike by 25 medium bombers, 18 scout bombers, and 18 torpedo bombers. These attacks further crippled Vila and Munda, and forced the Japanese to contest the Rendova landing without any close-in points for rearming and refueling.

The same false optimism which had given Admiral Yamamoto a distorted picture of the success of the April I Go operation prevailed, though, and surviving enemy pilots reported that they had sunk 2 destroyers and 1 cruiser, damaged 8 transports, set 2 destroyers afire, and downed 50 planes. Their own losses they set at 17 attack bombers and 13 fighters. Despite the seeming top-heavy score reported by the Japanese, they ruefully admitted that “... due to tenacious interference by enemy planes, a decisive blow could not be struck against the enemy landing convoy.”27

That night, the Japanese hastily tried to assemble a strong raiding force in the Shortlands area for a counterlanding on Rendova, but only five of the destroyers made contact at the rendezvous area. Moving south around Vella Lavella, the force arrived off Rendova at about 0130 on 1 July. Ironically, the same rain squalls which resulted in more mud ashore reduced visibility to such an extent that the Japanese ships could not determine the debarkation point and were forced to withdraw.

The abortive naval raid climaxed a confusing day of action that saw many elements of the landing force fill roles never laid out for them in operation plans. Typically, Marines of the 9th Defense Battalion who went ashore early on 30 June to provide antiaircraft protection for the beachhead found themselves instead taking part in its seizure. The unexpected role as infantry was handled competently, and often eagerly, by the Marine gunners.

Prior to the operation, Colonel Scheyer had divided his battalion into four task groups. The special weapons group (Lieutenant Colonel Wright C. Taylor) was to land on 30 June and position eight 40-mm weapons on one of the offshore islands, Kokorana. The 20-mm guns and .50 caliber machine guns were to be used on Kokorana and Rendova for beach defense and protection for the antiaircraft weapons. The 90-mm group, under the direction of Major Mark S. Adams, was to land one battery on 30 June on Kokorana

for immediate antiaircraft protection, with another two batteries to be landed and emplaced on Rendova on 1 July. Lieutenant Colonel Archie E. O’Neil, in command of the 155-mm artillery group, was to land his big guns on the 1st and 2nd of July to deliver neutralization fire on Munda airfield positions and to support the eventual assault on the airfield. The tank platoon, under First Lieutenant Robert W. Blake, was to land in later echelons and wait on Rendova for commitment in the final push on Munda.

Initial resistance by the Japanese did not delay execution of the 9th’s missions. Quickly organizing the advance parties into combat patrols, the Marines secured Kokorana before starting the job of clearing firing areas for the 90-mm battery. Some assistance in unloading was given by Seabees and late-arriving Barracudas. On the east beach of Rendova, Marines seeking possible gun positions frequently found themselves ahead of the front lines engaged in flushing snipers. One patrol of the 9th wiped out a machine gun nest during such a reconnaissance. For the 9th Defense Battalion, this was the first close contact with the enemy, and many Marines took the opportunity to turn infantrymen and help secure the island.

While the beach perimeter was being expanded, Marines selected spots for future battery positions, command posts, fire direction centers, and observation posts. Telephone lines were strung, and fields of fire for the big guns cleared by blasting down palm trees. By the end of the first day ashore, the advance elements of the 9th Defense Battalion were bivouacked on Rendova’s beach and along the plantation road. Battery E of the 9th (90-mm guns) was in position on Kokorana, and had fired its first shots against a low-flying enemy fighter at 1645. Twelve 40-mm guns, eight 20-mm guns, and eighteen .50 caliber machine guns were set up along the beaches on both islands, bolstering the defense positions. Only one small hitch had delayed the quick installation of the 90-mm battery on Kokorana. The gun director was missing, and members of the battalion had to rummage through scattered piles of material on Rendova’s shore until they found it.

The next day, 1 July, troops and supplies in the second echelon of the Western Landing Force began to arrive, and the four LSTs and five LCIs encountered the same unloading problems that had plagued the assault troops. The ships had to approach the island at slow speed, inching along through the shallow water until grounded by mud at considerable distance from shore. Vehicles which attempted to churn through to the beach became bogged and had to be rescued by tractors. The weight of heavy artillery pieces, towed ashore by tractors in tandem, further ruined the road along the beach, and, after the guns were manhandled into position, traffic of any kind over the road was impossible.

While the rain poured on, almost without cessation, most of the personnel ashore were pressed into service again as beach working parties to carry rations, fuel, ammunition, communication gear, and other supplies from the jumbled piles on the beach to dumps inland. Attempts to gain some measure of traction for vehicles in the soft underfooting met with failure. Seabees tried to corduroy the former road with 12-foot coconut logs, but the logs and steel matting they used soon sank under the mud. In addition, areas believed

suitable for gun positions or bivouac areas became swamps, and dispersion of troops was almost impossible. Soldiers and Marines who attempted to dig foxholes morosely watched their efforts become sunken baths.

Despite the difficulties caused by the rain, by the end of the second day ashore, two guns of Battery A of the Marines’ 155-mm gun group were in permanent positions on Rendova and had test-fired several rounds at Munda. Battery B of the same group was ashore in a temporary position but had not fired. In addition, two 90-mm batteries were in place and all special weapons dug-in nearby for protection. The Marines, unable to dig habitable positions in the mud, built above-ground shelters with coconut logs and sandbags.

Army artillerymen, taking positions on Kokorana, found the island had a solid coral subsurface that held the 155-mm howitzers without difficulty. Moreover, since the island was open on the north side, no fields of fire had to be cleared. Soldiers of the 192nd Field Artillery Battalion pushed their guns into position, took general aim at Munda some 13,000 yards distant, and began firing registration shots late the second day. While the Army artillerymen and Marines struggled with their heavy guns, ammunition, generators, and radar units, combat patrols of the 43rd Division secured over half of Rendova. The stage was being set for the move to New Georgia.

Air activity during the second day was limited. The ComAirSols fighter cover over Rendova intercepted and fought off only one attempted enemy attack. The covering fighters also mounted guard over a strike by 28 torpedo and scout bombers at Vila, which further reduced that field to a nonoperational status. Before returning to Guadalcanal, each fighter plane worked over Munda defenses, strafing possible bivouac areas. General Mulcahy, assuming an active role in the operation, scheduled and directed the strike which helped American forces rout the enemy at Viru Harbor.

The third day ashore, 2 July, promised to be just as wet as the previous two days. While the 103rd and 172nd Infantry prepared for the move to New Georgia, the Marine 155-mm guns and the Army 155-mm howitzers continued firing registration missions on Munda airfield. Direct observation was used, with spotters clinging precariously to perches atop palm trees. As yet, no artillery fire control maps were available, so only area targets were selected. The 192nd Field Artillery and the Marine group fired with impunity; fears that the Japanese could retaliate with counterbattery fire proved unfounded.

It was at this point, shortly after 1330, that the Japanese air commander at Rabaul, Admiral Kusaka, finally had his inning. His timing was perfect. The ComAirSols fighter cover had reluctantly been withdrawn under threat of bad weather, and the Japanese bombers arrived only a few minutes after the Allied fighters departed. An early-warning radar unit was temporarily out of operation, while its generator was drained of diesel oil mistakenly used in place of white gasoline.

The Japanese flight, variously estimated at from 18 to 25 medium bombers, swung in over the east side of Rendova Mountain, catching the troops in the open on the beach. A bombing pattern that stitched the beachhead from one end to the other quickly dispelled any illusion that these might be friendly planes. There was time only for a shouted, “Condition Red,” before troops frantically sought cover. But

Gun crew of Battery C, 9th Defense Battalion is revealed in the flash of a 90-mm shell fired at Japanese night raiders striking at New Georgia. (SC 185876)

many were caught in the open, an extra dividend to the attractive target of ships, equipment, and supplies jammed into a restricted area. Many of the bomb salvos hit ration and fuel dumps; others exploded ammunition dumps. Highest casualties occurred among the Seabees concentrated on a promontory off the beach. A dynamite dump there was hit, its blast adding to the casualties of the bombing. The peninsula was promptly dubbed “Suicide Point.” Further, the clearing station of the 43rd Division was hit, which reduced the amount of assistance which could be given. Most of the victims were rushed to ships in the bay for treatment of wounds.

Because of the confusion, early estimates of the number of dead and wounded varied widely. Some men were reported missing, either killed by exploding ammunition or direct hits, or, more probably, removed to ships and hurried to Guadalcanal for treatment. In all, 64 men were killed and another 89 wounded. Seabees in the boat pool and soldiers in the 43rd Division bivouac areas sustained the heaviest casualties. In spite of the congestion, damage to matériel on the beach was relatively light. Besides the ammunition and fuel dumps hit, two of the 155-mm guns were scarred by bomb fragments, two 40-mm guns were damaged, and three amphibian tractors were holed. All were repairable, though, with the exception of one of the tractors.

The attack’s success was the result of many factors. For one thing, Army radar units had gone out of commission shortly after landing, and although a Marine radar unit had been landed on 1 July, it was this one that was being drained of diesel fuel. Also, on the day previous, the troops had believed a flight of American medium bombers to be enemy planes and had scrambled for cover. This day they believed the enemy planes to be the same mediums back on station. A third factor was lack of dispersion. Shelters had been dug along the beach, but the troops were now busy handling other matériel, and had not provided other protection. But as a result of the raid, the area became dotted with foxholes—deep foxholes.

By 3 July, the routine of operations ashore was established. Troops of the 43rd Division began the shuttle to Zanana Beach on New Georgia, and the big guns of the 9th Defense Battalion and the 192nd Field Artillery picked at Munda’s defenses, seeking for a hidden strong point, a bivouac area, or a supply or ammunition dump. A 130-foot coast artillery observation tower of 1½-inch angle iron made spotting easier than viewing from a swaying palm tree. Erected on high ground about 200 yards back of General Hester’s command post at the foot of Rendova Mountain, the tower provided a central point from which Marine and Army spotters could radio corrections to the artillery fire direction center and then observe the strike of the shells on Munda airfield and its bordering hills across the channel, and on the nearby islands off New Georgia’s shore. In time, a system was developed whereby films dropped near the tower by photographic planes were immediately picked up, developed, and then studied for assessment of damage to Munda defenses.

On the night of 3 July, the enemy attempted to follow up its devasting strike of the 2nd with an attack from the sea. A Japanese naval force suddenly appeared offshore and spattered the Rendova beachhead area with a bombardment

which did little or no damage. Allied destroyers and torpedo boats forced the enemy ships to withdraw hastily without accomplishing the hoped-for crippling blow to the invasion troops.

As following echelons of the Western Landing Force unloaded on 4 July, a desperate Japanese command at Rabaul tried once more to knock the invasion force off Rendova. Since the air attack on 2 July represented the only measure of success in their efforts so far, the Japanese repeated the act. The cast and the script remained the same, except for the final curtain. This time the Japanese found themselves holding the wrong end of a Fourth of July Roman candle. From a force of more than 100 planes trying to press home on attack through the ring of Allied interceptor planes, only 16 bombers were able to swing over Rendova Mountain in the repeat performance. But this time, alerted by sound locators and radar, the 9th Defense Battalion antiaircraft batteries were ready, and 12 of the 16 bombers and an escorting fighter were knocked down in flames. The 90-mm guns expended a total of only 88 rounds, a feat which the Marines jubilantly proclaimed a record for rounds per plane.

This attack on Rendova was the last daylight assault on the island of any size made by the Japanese air fleet. From this point on, the attacks were made at night. Although the ComAirSols fighter cover still maintained a vigil over Rendova, the focus of the air war shifted to New Georgia as the troops shuttled from the beachhead at Rendova to the beachhead at Zanana. There the second phase of Operation TOENAILS was to begin.