Chapter 3: Munda Victory

Ashore at Zanana Beach1

The Allied landings in the Central Solomons and the New Guinea area caused Japanese planners some anxious moments. Plainly, the situation called for prompt action to relieve the pressure on the first defensive lines of Japan’s war-flung empire, but the question was: Where should the major effort be directed? To date, all attempts to repulse the landings had proved futile, and prospects for future success didn’t look too promising, either. Mindful of earlier basic plans to retain the Central Solomons while holding out in New Guinea, the Japanese commanders at Rabaul scheduled a conference for 4 July to reach a decision.

To General Sasaki and Admiral Ota, ruefully watching the Rendova operations from a well-protected headquarters on Kokengola Hill at Munda airfield, the situation was a bit more pressing and a lot more personal. From observation it was apparent that the troops across the channel had come to stay and were building up for an offensive in strength. When 155-mm guns and howitzers began to register on the airfield, the pattern of the campaign became all too clear. Munda was going to need reinforcements, and quickly, if it was to be held.

The two commanders reported their appraisal of the situation, and then took steps to strengthen the airfield defenses as best they could with the troops available. In a series of orders signed jointly by Sasaki and Ota, all eastern New Georgia lookout detachments were recalled on 30 June, and two recently arrived 140-mm guns and two smaller mountain guns were ordered rushed overland from Bairoko. In addition, a reserve force, the 12th Company, 229th Regiment. was alerted to move from Kolombangara to New Georgia.

As the Allied buildup on Rendova continued, however, these defensive measures began to look woefully weak, so the remainder of the 3rd Battalion, 229th Regiment, was ordered to Munda’s aid. By Sasaki’s own estimate, all defenses must be ready by dusk on 3 July. Meanwhile, the combined Army and SNLF units were exhorted to “maintain alerted conditions throughout the night and guard against enemy landings; if the enemy commences

to land, destroy them at the water’s edge.” On 2 July, the command relationship was changed. Sasaki, as the senior officer, “in response to the conditions in this area,” assumed sole command of all New Georgia garrisons. Admiral Ota, relieved of his landing forces, was assigned control of Army and Navy barge and shipping units in the area.2

The actual invasion of western New Georgia was not the direct assault on Munda airfield which Sasaki and Ota believed was coming. Instead, in a landing on 30 June which actually preceded the Rendova assault by several hours, soldiers of Companies A and B, 169th Infantry scrambled ashore on the islands that guarded the Onaiavisi Entrance to Roviana Lagoon. Lashed by heavy rain squalls and hampered by the darkness, the soldiers nevertheless managed to make contact with a waiting pre-D-Day amphibious patrol and native scouts. The landing was unopposed, but not uneventful. The mine sweeper Zane, which had been used as a transport, went aground on a small island just inside the entrance, and lay exposed as a telltale marker. Her helpless state and the landing area were ignored, however, by Japanese planes striking at the Rendova landing. The ocean tug Rail, summoned from Guadalcanal, pulled the Zane off the reef late that afternoon.

After securing the entrance islands, the soldiers began the move to Zanana Beach on the shore line of New Georgia. Earlier plans had called for Company O of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion to act as scouts for this phase of the operation, but with the raiders still at Segi and Viru, reconnaissance teams from the Rendova forces were organized. These were later augmented by a company of Fijian and Tonganese scouts, who were aggressive and skilled jungle fighters.3 (See Map 5.)

The patrols moved into the area between Zanana and the Barike River, marking water points, trails, coastal roads, possible artillery positions, and all avenues of approach to Munda. They were also ordered to probe Japanese defenses between the airfield and Bairoko Harbor, and to report all barge activity observed. One of the first radioed messages from the patrols reported a successful ambush of a Japanese group and that uniform markings on a dead enemy rifleman indicated that he had been a member of the 229th Regiment. The ambushed Japanese had been part of the 5th Company, 2nd Battalion, which had been ordered to investigate the Onaiavisi Entrance landings and “drive out the enemy who has landed there and make the area secure.”4 Later the 5th Company was told to resist stubbornly against this new phase of landings and fight to the last at their present positions. These instructions set the pattern for Japanese resistance in New Georgia.

General Hester received Admiral Halsey’s approval to proceed with the New Georgia phase of TOENAILS on 2 July. That night, elements of the 172nd’s 1st Battalion began the move from Rendova to Zanana Beach. The troop transfer was

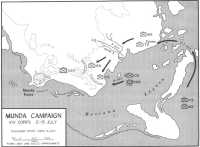

Munda Campaign, XIV Corps, 2–15 July

made in landing craft, which towed additional rubber boats carrying soldiers. Torpedo boats furnished an escort across Blanche Channel, and, at Onaiavisi Entrance, native guides in canoes took over and directed the landing craft through the lagoon to the beachhead. The following day, 3 July, Brigadier General Wing established the 43rd Division’s forward command post (CP) on New Georgia. A 52-man detail from the 9th Defense Battalion’s special weapons group arrived on 4 July and immediately emplaced four 40-mm guns for antiaircraft protection. Four .50 caliber machine guns were sited to protect the antiaircraft positions and to add depth to the firepower of the soldiers.

The Japanese air attack of 4 July at Rendova managed to make targets out of most of the troops that were to participate in the push on Munda airfield. The 172nd was still in the process of shuttling troops to Zanana Beach; and the fifth echelon of the NGOF, the remainder of the 169th Infantry and the 136th Field Artillery Battalion carried in 14 LCIs and 4 LSTs, had just arrived at Rendova Harbor. The 169th had remained in the Russells as division reserve during the early part of the operation, and the 136th was detached from the 37th Division on Guadalcanal. The air attack hit as the 169th and 136th were debarking. Unloading activities were abruptly abandoned. Luckily, no ships were hit. But for the new arrivals, the bombing attack following a sea-tossed trip from the Russells was a rough welcome to New Georgia.

Transferring their equipment and supplies to small craft from the Rendova boat pool, the soldiers began the movement to Zanana almost immediately. The 155-mm howitzers of the 136th were unloaded on one of the islands guarding Onaiavisi Entrance and positioned to provide artillery support to the troops attacking Munda. Other heavy weapons, the 105-mm howitzers of the 169th and 103rd Field Artillery Battalions were also emplaced on the offlying islands for additional fire support. By dusk of 5 July, the 172nd and the 169th Infantry were ashore on New Georgia, ready to begin the march toward the line of departure along the Barike River. A secondary landing, early on the morning of 5 July by the Northern Landing Group (NLG), commanded by Marine Colonel Liversedge, established a beachhead at Rice Anchorage on the north coast of New Georgia to threaten Sasaki’s forces from that direction.5

On the 6th, the 172nd moved west toward the Barike. Little opposition was encountered. The next day, however, as the 169th Infantry began its move to positions north of the 172nd, determined enemy opposition decisively stalled the entire regiment. Stopped short of the Barike, the 169th went into bivouac.

Accounts of the action during the night of 6 July combine fact and fancy. Reports that Japanese riflemen had infiltrated the loose perimeter set up by the 169th’s leading battalion caused a panic among the soldiers. Although the regiment had been on Guadalcanal and the Russells prior to New Georgia, the troops evidently were not prepared for jungle combat at night. Soldiers reported the next morning that enemy infiltrators threw grenades, screamed, whistled, shouted invective, and jumped into foxholes to bayonet

the occupants. After a wild night of grenade bursts, shooting, and screaming, however, no enemy dead were found in the perimeter when dawn came and the soldiers were able to look around. But NGOF casualties were numerous.

The action on the night of 6 July, which started a wave of near hysteria among the troops, seriously impaired the combat efficiency of the 169th Infantry. Despite many later aggressive and determined attacks, the 169th’s initial failures along the Barike River were attributed to an apparent lack of combat conditioning and training.6

Regardless of speculation as to whether such night attacks were wholly real or in part imagined, there was no denying the end results—the loss of many front-line troops through actual wounds and war neurosis. Later all regiments in the attack were subjected to this type of enemy tactics. In defense against such raids, 43rd Division soldiers adopted a policy of joint foxholes for two or more men protected by trip wires with noise makers attached. In addition, a rigid fire plan was adopted which prohibited promiscuous shooting and movement at night and allowed only the outside perimeter to fire or use grenades. These defensive measures restored discipline and stability.

After delaying most of the morning of 7 July in reorganization, the 169th resumed its push toward the Barike. Again the regiment was stopped almost immediately by aggressive enemy resistance. Although the 169th managed to overcome this first enemy opposition, the soldiers had to fight another lengthy action before reaching the low hills east of the river. The 172nd, in its zone of action, had pushed to the Barike without too much trouble. When it became apparent that the 169th could not reach the Barike River in time to begin the attack on 8 July as planned, General Hester—with Halsey’s approval—ordered the operation delayed one day. The NGOF commander also cancelled that part of his plan that called for a direct assault on the airfield over Munda bar by a battalion of the 103rd Infantry with Marine 9th Defense Battalion tanks in support. Mounting evidence that the Japanese held the area in great strength dimmed the prospects for the success of such a thrust.

After another night of infiltrators’ attacks, during which soldiers crouched sleepless in foxholes, the advance was resumed the next morning. The 172nd moved fairly easily along a coastal trail in a column of battalions. The 169th, struggling through the jungle with an open flank screened only by the Fiji scout company, was echeloned to the right rear. A heavy concentration of mortar and artillery fire on the Japanese position to the immediate front of the 169th broke resistance there; and, aided by a flanking attack by the 172nd hitting from the left, the 169th was able to push ahead. Late in the afternoon of the 8th, the fatigued 169th struggled into position on line with the 172nd to start the drive toward Munda the following morning.

NGOF in Attack: Zanana to Laiana7

Booming salvos from four destroyers at 0512 on the 9th of July signalled the start of the NGOF attack. The one-hour naval bombardment, which dumped 2,344 five-inch shells on positions in the rear of the enemy lines, was followed by a cannonade by all artillery battalions of the NGOF. The shelling combined the fires of two 155-mm howitzer battalions, one 155-mm gun battalion, and two 105-mm howitzer battalions. In all, the Munda-Barike area was battered by 5,800 rounds of high explosives. Enemy defensive positions, lines of communication, bivouac areas, and command posts were blasted for one hour before the fires were shifted to the area to be assaulted by the ground troops. As artillery lifted, 52 Navy and Marine torpedo bombers and 36 scout bombers struck, dropping high explosive and fragmentation bombs on the area. At 0900, heartened by this extreme concentration of firepower, the 43rd Division started its attack toward the NGOF objective—Munda airfield.

After clearing the initial Japanese resistance, the advancing soldiers encountered only snipers and small outposts. Progress, however, was slow. Each new enemy opposition forced deployment and attack. Hidden snipers, pinning down the advance units, held up the regiments for hours. Every step forward was a struggle against a determined enemy and multiple jungle obstacles—dense, vine-choked underbrush, steep ridges, numerous swamps, constant and enervating heat, and almost incessant torrents of rain.

The only maps provided the attacking force were sketches based on aerial photos. The drawings outlined jungle areas with conventional symbols which did not reveal the intricate, abrupt mass of hills, ridges, and swamps—jumbled without pattern—that lay under the thick jungle canopy. Contour lines on the maps were based on scouting reports, and, as 43rd Division soldiers discovered, were usually in error. The ridges and hills, bending and twisting in all directions, forced the attacking units to move in one direction, then another. As a result, by the end of the second day of the attack, both regiments had become intermingled and were attacking in virtually a single column. The initial frontage of 1,300 yards had collapsed to almost one-half that distance. In addition, the lines of communication and supply were now stretched over two miles through the jungle from Zanana Beach, an extension exceedingly vulnerable to counterattack from the north, or right, flank.

For the 169th, the advance had been particularly harrowing. Given a zone of action that forced them to cross the meandering Barike River a number of times, the soldiers slowly pressed forward over the steep ridges and through the deep swamps in the upper river region. Fatigued from the initial struggle through the jungle from Zanana, and continually harassed at night by enemy soldiers probing at the exposed right flank, the 169th was a dispirited outfit. After such a

disappointing start, the regiment mustered only lethargic attacks against enemy opposition. Wounded soldiers and combat fatigue cases wandered back along the trail to Zanana, draining the front lines of needed strength and creating a serious evacuation problem. Additionally, with the regiment so strung out, troops were needed to carry food, water, and ammunition to the attackers as well as help evacuate the wounded, tasks which further sapped the fighting strength of the outfit.

The pattern of enemy resistance developed by the end of the second day of attack, 10 July, plainly indicated that the Japanese were holding a barrier position in the high ground east of Munda airfield which they would defend in strength. The NGOF offensive—grinding against this line of mutually supporting fortifications of logs and coral, strongly defended by automatic weapons, mortars, and artillery—faltered.

As the NGOF struggled against the jungle and a tenacious enemy, engineers attempted to established a supply route to the front lines by hewing a jeep road out of the matted underbrush. Native guides pointed out a trail which took advantage of as much high ground as possible, but most of the route had to follow the marshy banks of the Barike River and in some instances ran parallel to the front lines. Bridging of the Barike was accomplished in several spots by trestles made of felled timber. Even while constructing the road in the rear of the front lines, however, the engineers were under almost constant attack from bypassed snipers and wandering squads of enemy. Bulldozer operators were a prime target, and engineer casualties mounted as the road clearing proceeded. Metal shields were eventually welded to the tractors to protect the ‘dozer operators. Since no heavy graders were available, the jeep road could not be ditched or crowned, and any traffic over the road after a rainstorm usually meant extensive road repairs.8

With the need for a closer reinforcing and resupply point made obvious by conditions to the rear of the NGOF front, Hester’s staff focused attention on Laiana Beach. Rejected earlier as a landing site because it was deemed too heavily defended and too inaccessible for quick resupply, Laiana now appeared to be the answer to NGOF logistic problems. The beach was some 5,000 yards closer to Munda, and its possession would shorten supply, evacuation, and reinforcement lines as well as put fresh attacking troops considerably closer to the main objective. On 11 July, General Hester ordered the 172nd to disengage from the frontal assault and pivot southwest in an attack toward the coast line to secure Laiana Beach. At the same time, the NGOF commander alerted the 3rd Battalion, 103rd Infantry and the tank platoon of the 9th Defense Battalion to be ready to leave Rendova for Laiana as soon as the 172nd reached the coast.

Though the 172nd was only a short distance northeast of the beach when directed to attack, the area was not secured until 13 July. Despite near-constant artillery assistance which shredded and blasted the jungle covering from defenses on the sharp hills between the 172nd and Laiana, the enemy clung stubbornly to his positions. Repeated air strikes failed to dent the defenses, and the Japanese, apparently aware of NGOF intentions, rained mortar and artillery fire between the 172nd and its

Avenger torpedo bombers wing toward New Georgia on 9 July 1943 to strike Munda airfield in support of the 43rd Division’s attack. (USMC 57685)

Marine light tank, accompanied by Army infantrymen, moves through the jungle toward the front lines on New Georgia. (SC 395877)

objective. Marine tanks and the 103rd Infantry Battalion, scheduled to land on the 12th, were held back. The 172nd reached Laiana on the 13th, and, on the following day, landing craft and tank lighters carried the reinforcements ashore. Artillery smoke shells covered the landing activities. Although the infantry hit the shore line without incident, enemy 75-mm guns hidden in the jungle fired random shots at the lighters. No hits were scored, and all tanks were put ashore without damage. From his headquarters at Munda, General Sasaki observed the smoke screening this new development; but in his orders for the 14th of July, he erroneously reported that 70 large barges had attempted to land but had been repulsed with the loss of 15 of the barges.9

While the 172nd held the new beachhead area and waited for the 169th to close the gap between the two regiments and come abreast, the Marine tanks and 3/103 moved into division reserve. A special weapons detail from the 9th Defense Battalion accompanied the infantry to Laiana and set up 40-mm, 20-mm, and .50 caliber antiaircraft weapons for protection against Japanese strafing and bombing attacks.

In the 169th’s zone, strong mortar and artillery fires were placed on Japanese defensive positions in an effort to reestablish forward movement, but the enemy resistance continued. At this time, the regiment—tired and understrength—was opposed by a determined, dug-in enemy to the front and continually harassed by snipers and infiltrators in the rear areas. On the 11th, the 169th’s commanding officer and his staff were relieved by Colonel Temple Holland and a staff from the 145th Infantry, 37th Division. The new regimental commander postponed further attacks by the 169th until the next day so that he might have time to reorganize his command.

A new push by the 169th on the 12th, following a rolling artillery barrage, failed to gain ground, however, and a return was made to the line of departure. The following morning, 1,000-pound bombs dropped by 12 scout bombers of Com Air New Georgia further hammered the defenses holding up the 169th’s progress. Pilots returning from the strike noted that the target area marked by smoke shells was 600 yards east of the grid coordinates given in the air mission request, an indication of the difficulties the 169th was experiencing in locating its position on the ground. The whole regiment was committed to the attack after the air strike, but only the 3rd Battalion on the left managed to gain ground. Successful in seizing the crest of a small knoll about 600 yards to the front, the battalion hung grimly to its position and repelled several strong counterattacks. During the next two days, the 3rd Battalion took 101 casualties, dead and wounded. Despite strong enemy pressure, the infantrymen held their position. Barrages fired by supporting artillery units boxed the front and flanks of the salient, and discouraged the development of a large-scale Japanese counterattack.

In an effort to aid the beleaguered 3rd Battalion, the 1st Battalion attacked on the 15th toward a dominating rise of ground about 400 yards to its right front. When opposition failed to develop, the attackers clambered to the top of the ridge, only to find deserted pillboxes, abandoned foxholes,

and empty trenches. The Japanese defenders had finally withdrawn.

The victory lifted the spirits of the entire regiment, but more heartening was a glimpse of the NGOF’s ultimate objective—Munda airfield. On its coral white runways and taxiways some three miles away could be seen wrecked and burned enemy planes. With new vigor, the 169th took over the enemy positions and prepared to defend the newly won ridgeline.

Counterattack Preparations10

While General Hester’s NGOF fought its way from the Barike to Laiana, General Sasaki’s defenders were operating on the simple strategy of trading space for time. Considerably outnumbered, the 229th Regiment and 8th CSNLF had nevertheless forced the invading American division to move slowly and cautiously. Sasaki’s defensive lines had reduced the NGOF invasion to a groping, stumbling advance—much in contrast to the swift, hard-hitting operation envisaged earlier by the Americans. The Japanese played for time during which reinforcements could arrive.

The plight of the Munda defenders had received immediate attention. General Imamura, commanding the Eighth Area Army at Rabaul, on 3 July ordered the New Georgia defense augmented by the remainder of the 13th Regiment as well as by additional antitank, mountain artillery, engineer, and medical units. In addition, the rear echelons of the 229th Regiment, which were still in the Shortlands area, were ordered to join their parent unit. A number of large landing barges were also dispatched to New Georgia. Most of the fresh troops were to stop at Kolombangara, but the elements of the 229th, the antitank units, and most of the engineers were to go directly to Munda.11 In all, Imamura ordered about 3,000 troops from the Shortlands-Faisi area to the New Georgia Group. More reinforcements were to follow. The joint Army-Navy conference at Rabaul, on 4 July, cemented the understanding between the Eighth Area Army and the Southeast Area Fleet that the main sea and air effort would be directed against the Central Solomons while the troops already on New Guinea would hold out without additional help for the time being.

Imamura’s promised reinforcements started to New Georgia on schedule, but the transports bumped into an Allied destroyer force lurking in Kula Gulf and turned back to the Shortlands to await a better time. The next night, 5-6 July, the transports sailed again, and, although part of the force was ambushed by Allied ships, the Japanese managed to land about 850 troops on Kolombangara.12 On New Georgia, General Sasaki shoved all available 229th Regiment, 8th CSNLF, and 38th Division support troops into the defense of the airfield in an attempt to hold out as long as possible. His line of fortifications,

spiked with seacoast and dual-purpose guns, ringed the coastline of Munda Point for some 6,500 yards and then swung inland from Roviana Lagoon for almost 3,000 yards. As NGOF troops were to find out, it was a formidable area to crack.

Sasaki’s tactics in the defense of the terrain between the Barike River and his main positions around the airfield were to counterattack continually in the hopes of offsetting any gain which the NGOF might make. Skillfully deploying the forces available, his field commanders ordered one company to hold and threaten a flank of the Allied line while other units slipped to the rear of the attackers to raid and cut communications. This infiltration had the calculated two-fold effect of creating casualties and demoralizing the attacking force. In instances where it became necessary to hold a particular strong point, an ambush squad with orders to fight to the death was left in position.

While part of the Munda defense force wrestled with the advancing Allied units, other engineers and soldiers feverishly built pillboxes, dug trenches, and cleared lanes of fire in defensive lines to the rear. Each time the Japanese gave ground, they fell back to another strong position. Well-camouflaged and protected, the barrier of mutually-supporting positions allowed Sasaki’s troops to contest any advance stubbornly. The terrain was an ally, since it hid the Japanese defenses and forced the Allied attackers to battle against the jungle and enemy troops simultaneously. Sasaki had another advantage, too. He was close to Bougainville and the Shortlands, and although reinforcements—mainly machine gun, antitank, and artillery units—dribbled into New Georgia in an unsteady stream, his strength remained nearly constant. Troops from Kolombangara, transported to Munda by barges during the night, were at the front lines the next day.

With the Allied lines inching slowly toward Munda, the Japanese were aware that the only means of re-establishing any type of order in New Georgia depended upon a strong counterattack. Weighing the time element against the danger, the Japanese decided on a delaying action in the Munda area while a counterattacking force struck through the upper Barike River region. As reinforcements arrived at Kolombangara, this counteroffensive was kept in mind. The ground attack would be staged simultaneously with a sea campaign, which would cut Allied supply lines while the air fleets pounded the Allied lines and rear areas on New Georgia.13

The 13th Regiment, which had moved in parcels from the Shortlands, was selected to straighten the lines in New Georgia. On 8 July, Colonel Tomonari was alerted to send the 2nd Battalion to Bairoko Harbor to help Commander Saburo Okumura’s Kure 6th SNLF defend that area from another but smaller Allied landing force. At the same time, Tomonari was to relinquish command of Kolombangara’s defenses to the commander of the Yokosuka 7th SNLF and with the remaining two battalions of the 13th Regiment advance to Munda for the new attack.14 Okumura, at Bairoko, was to cover the 13th’s advance from Kolombangara and then defend the Bairoko area without further assistance. Sasaki’s orders

to Tomonari were for the counterattacking force to move to a bivouac area on a plantation about five miles north of Munda. The 13th was to remain there until Sasaki deemed that the time was opportune for the attack.

To ensure that the operation would go smoothly, Sasaki established a liaison post at the plantation area and then sent a guide to meet Tomonari at Bairoko. Plans proceeded without a hitch as the first echelon of about 1,300 men moved by barge to Bairoko on 9 July. On the 11th, another 1,200 troops moved across Kula Gulf and a further 1,200 men made the cross-channel journey by barge on the night of the 12th. The movements were postponed several days by naval action in the gulf, but just as soon as they were able to make the crossing, all units of Colonel Tomonari’s attacking force, mainly the 1st and 2nd Battalions, assembled at Bairoko.

In moving into the bivouac area, Tomonari’s force abruptly ran into a trail block set up by part of Colonel Liversedge’s Northern Landing Group. In a brief but sharp encounter, the American force scattered the 13th Regiment’s leading elements, and reported to Liversedge that a large movement of Japanese reinforcements had been prevented from reaching Munda. Actually, Tomonari had broken off the engagement so as not to disclose the impending counterattack. Instead of staying to slug it out with the NLG, Tomonari withdrew his two battalions, and Sasaki’s guides then led the Japanese soldiers toward Munda over another trail. By the morning of the 13th, Tomonari’s main elements were at the plantation assembly area.

With two regiments now in position to oppose the landing force hitting toward Munda on the south, Sasaki was confident of his ability to reclaim the initiative. Some of his optimism could have been used by his superiors, however, because Army-Navy disagreements were stalling the progress of further help in the airfield’s defense. The Navy, seeking the commitment of an additional Army division in New Georgia, wanted reassurance that Navy installations in Bougainville, the Shortlands, and Rabaul would be protected. The Navy suggested a possible 2,000 troops for the Rice Anchorage area, 3,000 more for Munda airfield, another 2,000 to take over the Roviana Lagoon islands, and an additional 4,000 to be used as an attacking force.

The Army turned thumbs down. The Eighth Area Army had no intention of further reinforcing the New Georgia area. To Army planners, there was no way in which the war situation could be altered, and, as a matter of fact, a reappraisal of the situation had convinced them that Bougainville could not be held long if the Allies attacked there. While this difference of opinion existed, General Sasaki would have to make do with the Southeast Detachment Forces already at hand and those few scattered rear echelon and support troops which destroyer-transports could rush to Kolombangara for barge transfer to New Georgia.

Marine Tanks vs. Pillboxes15

The occupation force’s struggle to advance on New Georgia was anxiously

watched by the remainder of the NGOF on Rendova and the barrier islands. Artillerymen, executing fire missions, noted that front lines did not move forward. Landing craft coxswains, returning from supply runs to Zanana and Laiana beaches, brought back reports of the fighting and distorted stories of the Japanese infiltration raids. All NGOF units knew that the 172nd was stalled in the hills west of Laiana and that the 169th was understrength and fatigued by the struggle through the jungle. Despite the continual and intense pounding by three 155-mm and three 105-mm gun and howitzer battalions, which seemed to have leveled all above-ground installations, the enemy still seemed as strong as ever and apparently as disposed to continue the fight. Air strikes, which included as many as 70 planes, bombed the enemy defenses without apparent results except to strip foliage from the jungle.

Realization that more Allied troops would be required had come early in the campaign. On 6 July, General Hester had requested, and had been granted, the use of the 148th Infantry (less one battalion with the NLG) as division reserve. The 145th Infantry (also less one battalion with the NLG) was additionally attached to Hester’s NGOF. Both regiments were alerted for possible commitment to combat and, prior to 14 July, were moved to Rendova where they would be readily available.

With the addition of two regiments as NGOF reserve, a needed change in the command structure became more apparent. For some time, observers had believed that General Hester’s 43rd Division staff, split between the two tasks of directing a division in combat and a larger occupation force in a campaign, had been unequal to the job. Moreover, on the 13th, General Griswold of the XIV Corps had some disquieting reports for Admiral Halsey and General Harmon:–

From an observer viewpoint, things are going badly. Forty-three division about to fold up. My opinion is that they will never take Munda. Enemy resistance to date not great. My advice is to set up twenty-fifth division to act with what is left of thirty-seventh division if this operation is to be successful.16

Halsey, on 9 July, had directed Harmon to name a corps commander to take command of all ground troops on New Georgia. Now, after Griswold’s first-hand report from the front lines, Halsey told Harmon to take whatever steps he thought necessary to straighten out the situation. Griswold and his XIV Corps staff was ordered to assume command of the NGOF and Hester was returned to the command solely of the 43rd Division.17 All ground forces, including those of the 37th Division, now in the NGOF, as well as the 161st Regiment from the 25th Division, were assigned to Griswold’s command. The new NGOF leader, requesting a few days for reorganization, promised a prompt, coordinated attack. The command change was effective at midnight, 14 July, a date which happened to coincide with the long-planned relief of Rear Admiral

Turner by Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson as Commander, III Amphibious Force. Turner returned to Pearl Harbor to take command of amphibious forces in the Central Pacific.

The addition of tanks and a fresh battalion of infantry to the forces at Laiana beach buoyed the hopes of the NGOF that the impetus of the attack could be resumed. The tank platoon of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion had landed on Rendova with its parent unit, but had not been required for seizure of the island. The tanks later moved to Zanana Beach to support an engineer mission shortly after the NGOF began its attack. The marshy ground in the vicinity of the Barike balked attempts to use armor in support of infantry operations, however, so the eight tanks were withheld from action until Laiana was taken. Here, it was reported, the ground was more firm and could support armored operations.

Forward movement of the 172nd Infantry in the Laiana area had virtually ceased when the Marine armor arrived. The enemy’s defensive line, a series of pillboxes dug into the hill mass rising just forward of the American lines, stubbornly resisted attack. Infantrymen attempting to push ahead were driven back by fierce machine gun fire from the camouflaged positions. In the hopes that a coordinated tank-infantry thrust could crack the defenses, an attack was planned for 15 July.

On the morning of the 15th, three tanks reported to the 2nd Battalion, 172nd on the left, while another trio of tanks moved toward the 3rd Battalion on the right. Tangled underbrush hid stumps and logs that hampered attempts to get into position, and the drivers had to back and turn the machines constantly to move ahead. In the left zone, the first opposition, which came from a log and coral emplacement, was promptly knocked out by 37-mm high explosive rounds and machine gun fire. Two grass bivouac shelters were peppered with canister rounds18 and machine gun fire, and six to eight dead enemy were reported in each by the 172d’s infantrymen following the machines.

Further progress was stopped, however, by enemy machine gun and rifle fire which began to pour from other camouflaged positions. The infantrymen sought cover. The Marine tanks, without infantry support, were forced to resort to a deadly game of blind man’s bluff. Hit from one direction, the tanks wheeled—only to receive fire from another quarter. By alternating canister with high explosive rounds, the tankers stripped camouflage from emplacements and then blasted each bunker as it was uncovered. Enemy soldiers attempting to flee the positions were killed by machine guns. Opposition gradually ceased, and the infantrymen moved forward. The advance marked the first significant gain in several days.

In the right zone, the other three tanks were also blasting hidden positions which supporting infantrymen marked with tracer bullets. At one time the tanks were under fire from five hidden bunkers and dugouts. Combat was so close in the thick, hilly jungle that in several instances the muzzles of the 37-mm guns could not be depressed enough to engage the enemy positions. Continually drummed upon by small-arms fire, and blasted repeatedly by grenade and mortar bursts, the armor withdrew after clearing the enemy from one hill. The 3rd Battalion immediately

occupied the positions and set up defenses. The only casualty suffered by the Marines in the engagement was one driver injured when a hidden log jammed its way through a floor hatch.

On the following day, three tanks with six infantrymen following each machine moved around the base of the hill taken by the 3rd Battalion and pushed through the heavy jungle toward the next hill. The tanks raked the underbrush with fire and then pumped explosive shells into the enemy positions. A number of pillboxes, dugouts, and enemy shelters were knocked out. Only rifle and automatic weapons fire opposed the advance, and the infantrymen quickly moved forward. In the 2nd Battalion zone on the left flank, defenses on the coast were outflanked by the tanks, which maneuvered along the shore line firing at the blind sides and rear of the bunkers. After nearly 200 yards of progress, the tankmen discovered they were without infantry support and returned to the lines. A second attack was stalled by heavy mortar fire which drove the supporting infantrymen back to their foxholes.

Unprotected by infantry, the tanks kept firing to the front and sides to keep enemy soldiers from attacking. Heavy jungle growth limited visibility to only a few yards and restricted maneuver of the machines. While trying to disengage from the battle, the tanks were rocked by heavy explosions, apparently from magnetic antitank grenades tossed against the machines by enemy soldiers hidden in the dense thicket all about the armor. The rear machine was blasted twice, and each of the other two tanks was damaged slightly by similar explosions. Swiveling and turning, the tanks fired at every movement in the brush, and, by sweeping the jungle with canister and machine gun fire, managed to break clear and crawl back toward friendly lines.

That night, the 3rd Battalion, 103rd Infantry relieved 2/172 in the left zone and another coordinated tank-infantry attack was scheduled. Working all night, 16-17 July, the Marines had five tanks available for combat. By prior agreement, 30 infantrymen were to accompany each machine and the tanks were not to move unless soldiers supported them. The day’s attack had hardly begun, however, before stiff enemy opposition developed. Machine gun and rifle fire spewed from a number of concealed positions, and bullets ricocheted among the infantrymen following the armor. Soldiers, returning the fire, attempted to locate the emplacements so that the tanks’ 37-mm guns could be directed against the enemy.

As the tanks maneuvered toward the enemy defenses, the lead machine was suddenly sprayed with flame thrower fuel by a Japanese in a camouflaged position. The fuel did not ignite, and the enemy soldier was quickly killed. In such close combat, however, even nearby infantrymen could not protect the tanks from hidden enemy soldiers who suddenly appeared to toss magnetic grenades on the tanks. The third machine, hit by such a missile, took a gaping hole near the hull. Two crewmen were wounded. A hasty look behind them convinced the Marines that the infantrymen had fallen behind, and that protection was gone. Covering each other by fire, the tanks moved back with one of the undamaged vehicles towing the disabled machine.

Although no long gains had been made in the three-day attack, the commitment

of armor on the extreme left flank of the NGOF front had helped wedge an opening into Sasaki’s defenses. A line of pillboxes stretching from Laiana beach northwest for more than 400 yards had been breached. Typical of the defenses was a cluster of seven pillboxes which covered a frontage of only 150 yards, each position defending and supporting the next. Overhead and frontal protection consisted of two thicknesses of coconut logs and three feet of coral. Skillfully camouflaged, with narrow firing slits, the bunkers were virtually a part of the terrain and surrounding jungle.

Tomonari Repulsed19

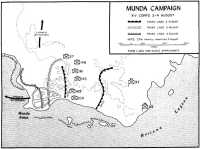

The Japanese counterattack hit just as the NGOF paused to consolidate its gains, restore contact and communication, and effect a reorganization and reinforcement. Through coincidence or superior combat intelligence, General Sasaki committed the 13th Regiment at a time when its appearance would provide the greatest shock effect. (See Map 6.)

Following its arrival at Bairoko and the move to the plantation area, the Tomonari Force scattered in small groups to reassemble north of the Barike River area. Sasaki’s orders to Tomonari were:–

The 13th Regiment will immediately maneuver in the area of the upper reaches of the Barike River; seek out the flank and rear of the main body of the enemy who landed on the beach east of the Barike River and attack, annihilating them on the coast.20

To accomplish this task, Colonel Tomonari was to take over the defensive positions in the designated area and establish a base from which attacks could be staged. Colonel Hirata’s 229th, with as much strength as possible, was to coordinate with the 13th and attack the American left flank.

Despite Sasaki’s precautions, however, the Tomonari Force was observed moving toward the Barike. On 17 July, the 43rd Division Reconnaissance Troop, screening the open right flank of the NGOF, reported that a large body of enemy, numbering from 200 to 300 men, had been observed moving toward the rear of the NGOF. One platoon of the troop attempted to ambush this force but was overrun. Sasaki’s admonitions to keep contact notwithstanding, communication between the Tomonari Force and the 229th was broken, and the two counterattacks were never synchronized. On the right flank of Sasaki’s units, the 3rd Battalion, 229th was kept off balance by the tank-infantry attacks of the 172nd. Farther north, the 169th was in a commanding position and was able to call down artillery fire on any observed group of enemy infantry, and thus effectively forestalled any threat of a push through the center of the line. Only the attack from the upper Barike materialized.

Shortly after dark on the 17th, enemy troops hit almost simultaneously at the rear area and beach installations of the 43rd Division. Soldiers helping to evacuate wounded were themselves cut down.

In a series of sharp skirmishes, Japanese infiltrators struck at the medical collecting station, the engineer bivouac area, the 43rd Division CP, and the beach defenses. For a short time, the fate of the command post was held in one thin telephone line. Although most lines were cut, contact with the artillery units on the adjacent islands was still open over one line, and support was urgently requested. Accurate and destructive artillery fire that virtually ringed the command post was the quick reply. In several instances, concentrations within 150 yards of the CP were requested and received. In a matter of moments, the Tomonari Force was scattered, and although the CP area was under attack all during the night, repeated concentrations falling almost within Allied positions kept any large-scale assault from developing.

In the beachhead area, Army service units, the 172d’s antitank company, and the 9th Defense Battalion’s antiaircraft detachment were also hit. A Marine patrol, investigating the CP situation, returned to report that a body of enemy infantry of near battalion strength was moving between the CP and the beach. Reclaiming two .30 caliber machine guns from an Army supply dump by piecing together parts from a number of guns, half of the 52-man Marine detachment went forward to set up an ambush ahead of the advancing Japanese, while the other half remained behind to man the antiaircraft defenses. The ambush stopped the first enemy attack, and, after the Marines fell back to the beach defenses, the attack was not renewed. The reason was apparent the next morning. Two Marines who volunteered to remain behind at the ambush had effectively stopped the counterattack by repulsing four attempts. Only one of the two Marines survived the attack, which left 18 enemy dead littered about the guns.

The night of 17 July virtually ended all Japanese attempts to regain the initiative. The Tomonari Force, in small groups, appeared from time to time in various areas, raiding and infiltrating, but was not an effective threat. Up to the time of the resumption of the NGOF attack, Sasaki still harbored hopes that he could collect his scattered forces for another attempt, but the rapidly-accelerating Allied buildup nullified all his efforts.

Corps Reorganization and Attack21

A number of Army units were close at hand for ready reinforcement of the NGOF lines. These were promptly ordered to New Georgia when the Japanese

counterattacked. The 148th Infantry was on Kokorana when the emergency alerted that unit at 0100 on the 18th; the 1st Battalion, dispatched immediately, came ashore at Zanana fully expecting to find the beach area in enemy hands and the 43rd Division CP wiped out. By this time, however, the serious threat had passed and when the regiment was assembled, it began moving to the front lines. Although an advance party was hit by remnants of the 13th Infantry, the 148th pushed forward aggressively, cleared the opposition, and moved into the rear area of the 169th by nightfall of the 18th.

The 145th Regiment, which already had one battalion in place as reserve for the 43rd Division, reached the rear of the 169th lines on the 20th. Upon the arrival the same day of Major General Robert S. Beightler, the 37th Infantry Division assumed responsibility for the sector and the 169th Infantry was relieved. Colonel Holland, who had directed the 169th in its capture of the hills overlooking Munda, returned to command of the 145th. The 169th’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, tired and badly depleted, departed for Rendova for a needed rest. The 3rd Battalion remained on New Georgia as 43rd Division reserve.

The arrival of other units also strengthened the NGOF lines. The 161st Infantry, detached from the 25th Division on Guadalcanal, debarked on the 21st. Attached to the 37th Division, the regiment moved into bivouac on the division’s right flank. The remainder of the 103rd Regiment joined the 3rd Battalion on New Georgia on the 21st and 22nd of July, and, from that point on, the 103rd (less the 1st Battalion still at Segi) fought as a regiment. Additional antiaircraft protection against the periodic Japanese air raids on New Georgia and Rendova was provided by a detachment of 4 officers and 140 men from the Marine 11th Defense Battalion. Alerted early in the campaign for possible commitment, a 90-mm battery, augmented by four 40-mm guns and four .50 caliber machine guns, was sent to Kokorana Island from Guadalcanal on 18 July.

During the period 18-24 July, while the NGOF swelled in size as fresh regiments poured in, the front lines of the New Georgia Force remained static. At this time, the main positions of the NGOF traced an irregular pattern through the hilly jungle in a northwest direction from Laiana Beach to the steep hills guarding the northern approach to Munda. Into this 4,000-yard front, still about three miles from Munda, General Griswold moved the two divisions with orders to continue the attack on the 25th. In the southern sector, General Hester’s 43rd Division had the 103rd Infantry (Lieutenant Colonel Lester E. Brown) anchored to the coast with the 172nd Infantry (Colonel Ross) on the right. In the 37th Division’s zone of attack on the north, General Beightler had placed the 145th Infantry (Colonel Holland) on the left flank and the 148th Infantry (Colonel Stuart A. Baxter) on the extreme right flank with the added mission of protecting the right flank and rear of the NGOF. The 161st Infantry (Colonel James M. Dalton) was assigned as the interior unit between the 145th and the 148th. To insure a rapid advance, the frontline units were directed by General Griswold to bypass all strong points, leaving these for the reserve units to eliminate.

Combat action during the period in which the NGOF reorganized and rested was limited. As each front-line unit moved into place, patrols sought to determine

the disposition and strength of the Japanese units to the front. Occasionally, scattered bands of 13th Regiment’s soldiers were encountered, and a number of confused, short skirmishes resulted. Casualties to both sides were light.

The NGOF had one advantage. The ground fighting had been relatively free of air interference, and most of the bombing attacks were by friendly planes on rear area enemy defenses. The Japanese had attempted but failed in several attempts to locate the NGOF front lines for a bombing and strafing attack. Segi, Wickham, and Viru, however, were visited regularly by nocturnal aircraft which the troops—conforming to South Pacific custom—tagged with the euphemisms of “One-Bomb Bill” or “Washing-machine Charlie.” Most of the Japanese air attempts, though, appeared to be aimed at Rendova where the bulk of supplies was stockpiled. An alert air cover, helped by antiaircraft batteries, kept enemy planes at a wary distance.

Air support missions requested by General Mulcahy as ComAir New Georgia were generally directed at the easily identifiable targets around Munda field. Close air support for troops fighting in dense jungle had proven impractical with target designation so difficult. Air-ground coordination, struggling against the handicaps of visibility and communications, was not helped by the inaccurate operation maps. Even though gridded, the photo-mosaics were not precise enough for such close work, where a slight error might result in heavy NGOF losses. Then, too, in the fighting where daily progress was measured in 200- or 300-yard gains, the troops were reluctant to withdraw for an air strike. Soldiers reported that when they had pulled back to provide a zone of safety for air strikes or artillery and mortar preparations, the enemy simply moved forward into the abandoned area and waited for the bombing or artillery to lift before moving back into their original positions in time to defend against the expected ground attack.

Requested support missions were flown by Strike Command, ComAirSols. The New Georgia support was in addition to the repeated bombing and strafing strikes at enemy shipping and airfields at Kahili, Ballale, Vila, Enogai-Bairoko, and Bougainville. The planes flew cover for task groups and friendly shipping as well. During the period 30 June to 25 July, the start of the corps offensive in New Georgia, the Strike Command squadrons flew 156 missions involving 3,119 sorties. In addition to more than four million pounds of explosives dropped on enemy installations, the ComAirSols planes counted 24 enemy ships sunk and another 28 damaged. A total of 428 fighter planes and 136 bombers were reported as destroyed by ComAirSols pilots. Strike Command losses in the Central Solomons during the period were 80 planes.

The final push on Munda promised the hardest fighting of the campaign. Between the NGOF and its objective were more than 4,500 yards of low but steep hills, irregular and broken, densely covered with tropical rain forest, and laced with enemy defenses. Reports of the patrols and observation of bunkers already taken indicated that the enemy soldiers were dug in and covered by low, two-level camouflaged coral and log emplacements with deadly interlocking fields of fire. Trenches bulwarked by coconut logs connected the bunkers. NGOF soldiers were

well aware that the enemy would have to be routed from these positions and that resistance until death was standard practice. Further, the soldiers knew that the enemy often abandoned one bunker to man another, and then, after the first bunker had been overrun, returned to defend it again. An area gained in attack during one day had to be cleared of infiltrators the following day.

Prior to the 25 July attack by the NGOF, an attempt was made by Marine tanks to crack the hill complex south of Laiana Beach and bring the 43rd Division units on a line with the 37th Division. Withdrawn from further engagements in that sector after the 17 July attack, the 9th Defense Battalion tanks were sent into action again on the 24th. An artillery preparation prior to 0700 pounded a 100-yard zone in front of the lines before the armor moved out from the lines of the left battalion of the 172nd Infantry. Repulsed by a strongly defended position in that sector, the Marine tanks tried again from the adjoining battalion of the 103rd Infantry on the left. Although several pillboxes were knocked out, the tanks were forced to withdraw after one machine was blinded by hits on the periscope. Two other machines sputtered with engine trouble caused by low-octane fuel and overheating. The withdrawal was made under fire, the disabled machine under tow by another.

Another point of tenacious defense was met by the 161st Infantry. Dalton’s regiment, attempting to move up to the line of departure, was told that only two pillboxes were to his immediate front. A reinforced platoon, making the initial attack, knocked out the two pillboxes but then uncovered another network of fortifications. A strong company was sent into the area. Two more pillboxes were knocked out, but 12 more were uncovered. At this point, the regiment moved in and knocked out these strong points before discovering more pillboxes. At last, with the 25 July attack impending, the regiment bypassed the fortifications and moved up to the line of departure. But before the pocketed strong point was reduced, “it took the combined efforts of two battalions, 3,000 rounds of 81-mm mortar fire, the use of tanks, and the passage of seven day’s time.”22

As General Griswold’s NGOF poised for the final make-or-break assault on Munda, his adversary was forced to face the contest with a dwindling stack of chips. XIV Corps intelligence officers estimated that General Sasaki had lost about 2,000 troops, including 1,318 counted dead, of the more than 4,500 which he had available earlier.23 His biggest gamble had failed—matched and beaten by a larger reserve. The 13th Regiment had now filtered back toward Munda to take up defensive positions to the northeast. The main units of the 229th Regiment, which had so bitterly contested the advance of the NGOF from the Barike, had taken steadily mounting casualties. Nearly cut off from the rest of the command by the pressure of the NGOF attack, the 229th took up final positions in the Munda hills, the battalions and companies considerably intermingled. General Sasaki, hoping to avoid some of the pounding aimed at Kokengola Hill, moved his headquarters from the airfield to the plantation north of it.

Map 6: Munda Campaign, XIV Corps, 25-30 July

With the worsening situation in New Georgia came new realization and uneasiness that Japanese positions in Bougainville would be as quickly overrun. A seaplane carrier protected by five destroyers, trying to reach that island on 22 July, was attacked by a force of 16 dive bombers, 18 torpedo bombers (all from VMTB-143), and 16 heavy bombers which stopped the reinforcement effort cold. Only 189 men out of 618 Army personnel aboard the carrier survived. Also lost were 22 tanks, heavy equipment, guns, fuel, and ammunition destined for the Central Solomons defenders. The destroyers, however, managed to land some troops.

Sasaki continued to hope for reinforcements, but the Allied clamp on Kula Gulf was too tight. The only major unit to reach New Georgia was the understrength 230th Regiment, a remnant from the Guadalcanal withdrawal. Only about 400 men reached Munda, and these were put into the final defense around Kokengola Hill. The pincers movement of the NGOF and the concentrated shelling and bombing counted toward making the Central Solomons situation doubtful, but the blockade of Kula Gulf by Allied destroyer forces, torpedo boats, and night and day air patrols was perhaps the telling factor. “Consequently,” the enemy was forced to admit, “the fate of the Munda sector became a matter of time.”24

General Sasaki, a realist, confessed that the Allies had complete material superiority and that a sustained push by the NGOF would collapse his command. Although he was envious of his opponents’ artillery, communication, and large landing boats, he was critical of the NGOF soldier—who, he said, advanced slowly, failing to take advantage of his strength and equipment:–

They awaited the results of several days’ bombardments before a squad advanced. Positions were constructed and then strength increased. When we counterattacked at close quarters, they immediately retreated and with their main strength in the rear engaged our pursuing troops with rapid fire. The infantry did not attack in strength, but gradually forced a gap and then infiltrated. Despite the cover provided by tank firepower, the infantry would not come to grips with us and charge. The tanks were slow but were movable pillboxes which could stop and neutralize our fire.25

The defense of the airfield had also depleted Sasaki’s forces. The Japanese soldier, fatigued and muddy, was forced to fight in some instances on only one rice ball a day. Kept irritated and sleepless by the constant bombardment, the Munda defender was gaunt, weary, and hungry—but still determined. Despite the hardships, morale was high and the Japanese soldier was “prepared to die in honor, if necessary.”26

The NGOF attack, now corps-size, opened on 25 July when five-inch shells rained upon the Munda area from seven destroyers. At 0630, heavy bombers began dropping 500-pound bombs and followed up with a rain of 120- and 300-pounders. Next came flights of torpedo bombers and scout bombers which dropped 2,000-pound and 1,000-pound bombs. In all, 171 planes took part in the saturation bombing of the area paralleling the entire front lines. Special attention was given to defensive positions in the

hills near the lagoon and the heavily defended strong point in the center of the Japanese defensive line, which the NGOF troops called Horseshoe Mountain because of its U-shaped appearance. Bibolo Hill, guarding Munda, was also worked over. (See Map 6.)

As the attack began, Japanese air units attempted to retaliate. At 0930, a flight of from 60 to 70 enemy fighters bore down on New Georgia, but the air cover provided by ComAirSols held off the attack. Additional Allied fighter planes, hastily scrambled from Segi’s newly completed airstrip, arrived in time to discourage a second attempt by the enemy planes.

NGOF artillery, firing parallel to the front lines, lashed the area to be attacked; and, with this awesome display of firepower to pave the way, the NGOF regiments began to move forward. One Japanese soldier, astounded by the volume of shelling, wondered, “Are they intending to smash Munda with naval and heavy artillery?”27 In the 43rd Division sector, the 9th Defense Battalion tanks were called to rescue troops of 3/103 held up by a strong point. Aided by a flanking movement of the 172d’s 2nd Battalion, the tanks slashed through the rear of the enemy positions facing the 103rd, and the Japanese hastily abandoned their positions to flee toward the next line of hills. Elements of the 103rd then pushed toward the relatively clear plantation area between Laiana and Munda. The advance was about 500 yards. The 3rd Battalion of the 169th then moved out of reserve positions to fill the gap between the 103rd and the 172nd.

The main effort of the first day’s attack was made in the 37th Division zone. The 145th Infantry, the left flank unit, held its positions in order to straighten the NGOF lines, while the 161st and 148th pressed the attack. Stiff resistance from the defenders of Horseshoe Mountain held the 161st to a slight gain, but the 148th easily advanced about 600 yards against occasional fire from small outposts. By nightfall, the NGOF had pressed itself against the Japanese front lines.

Marine tanks were in support of both divisions the following day. A newly arrived weapon making a first appearance in the fighting, the flame thrower, was combined with tanks from the 9th Defense Battalion to crack a belt of 74 pillboxes on a 600-yard front which faced the 103rd and 172nd regiments. The day’s attack put the 43rd Division well into the rear of the Laiana defenses. Farther north, the 145th continued to hold fast while the 161st attempted to crack the resistance to the front. A fresh Marine tank platoon, six of the machines from the 10th Defense Battalion, was committed to action in an attempt to clear the Horseshoe Mountain defenses.

After a five-hour struggle against the thick jungle and steep terrain, a total of 14 pillboxes had been demolished. The tanks, crashing through a thick underbrush tangled by fallen logs and stumps, finally located the enemy fortifications near a large clearing. Infantry support, however, was often pinned down by murderous enemy fire, and the tanks were forced to twist and turn, pivot and backtrack, to keep enemy riflemen from assaulting the machines with magnetic grenades. Three tanks were knocked out and abandoned before the Marine tankers could disengage from the furious fighting. The strong point remained, however, only partially silenced. That night, close-in artillery fire ringed the abandoned tanks so

that enemy soldiers could not use them as pillboxes.

On the far right, Colonel Baxter’s 148th Infantry continued to drive ahead against only slight resistance, advancing another 800 yards the second day. The move, however, put the 37th Division far ahead of the 43rd Division. To straighten the lines, the next attack effort would be directed against the enemy in the south. If the 103rd and 172nd could press past the open south side of the Horseshoe Mountain defenses, the penetration might relieve the pressure on the central portion of the NGOF line.

Marine tanks were to spearhead the 43rd Division attack in the south on the 27th, but the advance had hardly started before the lead tank was blasted by an antitank gun. Confusion resulted. The first tank, with casualties among the crew, stalled. As it started again and attempted to back up, it rammed the. second tank. A third tank was hit immediately by antitank fire. As a fourth and fifth machine moved up, one was blasted by magnetic mines and the other, after raking the jungle with machine gun fire, was also disabled by a grenade. All machines, however, by mutual fire assistance, managed to limp back to friendly lines. But the day’s attack virtually ended the combat efficiency of the 9th Defense Battalion tank platoon. Of the eight machines brought ashore, five had been disabled that day, a sixth had been disabled previously, and two others were under repair. Four tanks were reported deadlined permanently. In addition, the platoon had a number of drivers and crewmen killed or wounded.

Progress along the line on the 27th had been slight, for two localized strong points continued to hold up the advance. The 43rd Division still faced a rugged defensive area in the south which repeated tank-infantry assaults had failed to dent, and the 37th Division was hung up against the Horseshoe Mountain line, kingpin of Sasaki’s resistance. To XIV Corps observers, it was plain that the capture of either strong point would result in the downfall of the other.

On 28 July, 3/103 followed four Marine tanks into attack on the coast area after a 30-minute mortar and artillery preparation. The attack proved to be the finest example of tank-infantry tactics of the campaign. With the machines guarded and supported by the infantry, the battalion advanced in a series of spurts. For the first time, the tanks were operating over relatively flat and open terrain with dry footing. Enemy opposition began to falter, then dwindled rapidly, as the attackers rushed ahead. Even three direct hits by antitank guns on the lead tank failed to stop the attack. The enemy gun emplacement was overrun a few moments later. Completely routing the enemy in a 500-yard advance, the infantrymen took up defensive positions while the tanks continued to range ahead. One tank was hit, but managed to limp back to the lines. The day’s advance had completely broken the Japanese defenses in the south.

In the north, the 161st jumped off in an attack without prior artillery preparation and caught the enemy unawares. In a brief skirmish, the 161st occupied a ridge which had held up the advance for two days. At this time, the attention of the NGOF was suddenly drawn to the right flank where the 148th had abruptly found itself in trouble. As Colonel Baxter ruefully admitted later: “Don’t forget, being

too aggressive can often get you into as much hot water as doing nothing.”28

Baxter’s regiment, pushing ahead against weak and scattered opposition, had reached the Munda-Bairoko trail, but in so doing had opened a hole between the 148th and 161st. With two battalions in the attack, the 148th had been unable to plug the gap, and, as at the Barike River earlier, alert Japanese soldiers quickly infiltrated. That night, the rear supply dump of the 148th was under determined attack by an enemy force of considerable size. Support troops managed to beat off a three-sided enemy assault by using ration boxes and supply cartons as barricades, much in the manner of frontier wagon trains under attack by Indians. Elements of the 148th, which had reached as far as Bibolo Hill west of the airfield to confirm indications that the enemy was abandoning that front, now rushed back to the defense of the supply dump. In this instance, the 148th virtually had to fight its way to the rear as about 250 Japanese in small bands with machine guns and mortars, probably remnants of the Tomonari Force, harassed the unit for three nights. The 148th reached the supply dump and established contact with the 161st before turning about to resume the attack toward the northern part of Bibolo Hill.

Although the 43rd Division, now under the command of Major General John R. Hodge who had relieved General Hester, continued to push forward along the coast in rapidly increasing gains, the center of the NGOF continued to be snagged on the enemy defenses on Horseshoe Mountain. First break in the barrier came on 30 July when the 172nd attacked and occupied a small ridge complex southeast of the main defenses. The following day, 31 July, the 169th attacked and completed the reduction of the southern anchor of the Japanese strong point. The advance, however, still failed to break the Horseshoe defenses.

On 1 August, the 43rd Division punched through to the outer taxiway of Munda airfield. The move put the Allied force almost in the rear of Sasaki’s last strong point, and enemy resistance on Horseshoe Mountain suddenly dissolved. The airfield defenders had at last succumbed to the steady pressure of the NGOF.

The withdrawal had been ordered after the New Georgia Defense Force had become steadily weakened by lack of ammunition, food, and additional troops. Although a few destroyers managed to make Kolombangara, practically all Japanese transportation and supply lines had been strangled. On 29 July, an officer courier of the Eighth Fleet had arrived at Munda to relay to Sasaki the order to fall back to the line of hills ringing Munda for a last-ditch stand. The airfield was to be defended even at the price of Kolombangara. Reinforcements would come. Following instructions, Sasaki pulled what scattered elements he could find back to his last defense. As the campaign drew to a close, his line was held by the 229th Regiment on the south part of Bibolo Hill with the undermanned 230th Regiment on Kokengola Hill. On the extreme left flank were units of Tomonari’s 13th Regiment.29 Remnants of the 8th CSNLF were combined with Army units for a last-ditch stand.

At the close of the fighting on 2 August, the 43rd Division was perched on the last

low row of hills overlooking Munda airfield, and the 37th Division was gradually tightening the lines around the northern part of the airfield. The following day, Hodge’s troops captured the southern part of Bibolo Hill while the 37th Division moved cautiously but swiftly through isolated pillbox areas northwest of the field. The 148th, reaching the Munda-Bairoko trail once more, ambushed a large force of enemy fleeing the area. (See Map 7.)

As the two divisions resumed the attack on 4 August, the only opposition facing the 43rd Division came from Kokengola Hill in the middle of the airfield. While a rain of artillery and mortar shells blasted the hill, Marine tanks from the 10th and 11th Defense Battalions roamed about the airfield, flushing snipers and blasting rubble-hidden fortifications. The tanks from the 11th Defense Battalion had been hurriedly dispatched to take part in the assault of the airfield after the 9th Battalion’s tanks had been deadlined. Alerted on Tulagi since 30 June, the Marine tankers reached New Georgia on 3 August, just in time to join the final attack.

North of Munda, while the 145th mopped up the last shreds of opposition, the 161st and 148th Regiments plunged rapidly through to Diamond Narrows. In that final drive, the 37th Division soldiers staged a slashing, stabbing charge that overwhelmed all outposts. That night, the last shots fired were those sent after Japanese trying to swim to islands across the Narrows.

The following day, 5 August, tanks of the 10th and 11th Defense Battalions—accompanied as a courtesy gesture by the sole remaining operational tank of the 9th Defense Battalion—made five sorties over the airfield. The only fire received was from Kokengola Hill, and this the Marine tanks quickly squelched with 37-mm rounds. At 1410, the airfield was officially declared secured, and Allied troops took over the enemy fortifications ringing the war prize which had taken more than a month of bitter combat to obtain. Along the blasted and cratered runways were hulks of 30 enemy airplanes, some still in revetments. All were stripped of armament and instruments. None would ever fly again. Japanese supplies, including tasty tinned foods, beer, sake, and rice gave triumphant infantrymen a change from the weary routine of combat rations.

Beach defenses were strengthened the next day, and grimy soldiers bathed, washed clothes, and rested from the tough grind of battle. Patrols, ranging far to the north, reported no opposition. The patrols’ only result was the capture of one forlorn Japanese soldier, whom one officer described as typical of the enemy who were thwarted in their attempts to hold their precious airfield: “Injured, tired, sick, no food, dirty torn clothes, little ammunition and a battered rusty rifle.”30 For both victor and vanquished, the campaign had been hard.

The fall of Munda almost coincided with another disaster which heaped additional misery upon the Japanese. In a belated and ill-fated attempt to help Sasaki hold the Central Solomons, the Seventeenth Army at Bougainville organized two well-equipped infantry battalions, bolstered by the addition of artillery and automatic weapons. The troops were taken from the 6th and 38th Divisions. The reinforcement unit started for New Georgia on the night of 6 August in four destroyers. As the ships steamed through the

Map 7: Munda Campaign, XIV Corps, 2–4 August

north entrance of Vella Gulf trying to make Kolombangara, an ambush set by an Allied force of six destroyers (Commander Frederick Moosbrugger) struck suddenly. In a matter of moments, three of the Japanese destroyers were in flames and sinking. The ambush in Vella Gulf resulted in the loss of 820 Army troops and 700 crew members in a single stroke. It was the last attempt by the Japanese to reinforce the Central Solomons.

Munda’s capture was marked by the commitment of the 27th Infantry from Major General J. Lawton Collins’ 25th Division. Augmented by division support troops, the regiment joined the NGOF on 2 August and took over the mission of guarding supply and communication lines along the 37th Division’s right flank. After Munda was taken, the 161st Infantry reverted to 25th Division control and joined the 27th Infantry in a new push toward Kula Gulf.

With hardly a pause at the airfield, the two regiments pivoted north to complete the rout of all enemy forces in the area between Diamond Narrows and Bairoko Harbor. Only spotty resistance was encountered, for increased barge activity revealed that the Japanese were feverishly trying to evacuate the scattered remnants of the New Georgia garrison. After two weeks of locating and eliminating Japanese positions north of Munda, the 27th Infantry declared its zone secured. The 161st, meanwhile, had advanced toward Bairoko after knocking out enemy strong points on two jungle peaks. The final ground action on New Georgia came on 25 August, when the 161st Infantry combined with Liversedge’s force to attack the harbor area from three sides—only to find that the Japanese had just completed evacuation of the area. All organized enemy resistance on the island was ended.

Rendova: Final Phase31

During the period that NGOF soldiers slogged their way through jungle mud on the way to the airfield, the Rendova force settled into a routine of firing artillery missions and combatting enemy air raids. After the initial units of General Hester’s force departed for New Georgia, the harbor at Rendova became the focal point for all reinforcements, supplies, and equipment moving into the Central Solomons.

During July, daily transport shuttles from the rear echelons on Guadalcanal poured a total of 25,556 Army, 1,547 Navy, and 1,645 Marine troops into Rendova for eventual commitment in New Georgia. Additionally, the beaches at Rendova and its offshore islands became piled high with rations, oil and lubricants, ammunition, vehicles, and other freight, all of which found its way to the NGOF.

This bustling point of entry—with troops unloading and stockpiles of material lining the beaches—was a tempting target to the Japanese. The Rendova air patrol of 32 fighter planes constantly flying an umbrella over the island drained the resources of ComAirSols, but, at the same time, was a successful deterrent to enemy attacks. During the New Georgia campaign, only three enemy hits were

registered on ships in the harbor by bombers or torpedo bombers, and only one horizontal bombing attack was able to close on Rendova during the daylight hours when the fighter umbrella was on station.

Playing a major role in the defense of the harbor, the 90-mm batteries and the Special Weapons Group of the 9th Defense Battalion shot down a total of 24 enemy planes during the month of July. For the Marine antiaircraft crews, the defense of Rendova was virtually an around-the-clock operation which was a deadly contest of skill between enemy and defender. The Japanese tried all methods of attack, including hitting the target area with planes from various directions and altitudes simultaneously. Since large areas of the search radar screens were blocked by mountains on New Georgia, this approach route became the favorite of the Japanese pilots. Warnings for attacks from this direction were so short as to be almost useless, so Marines were forced to keep at least one 90-mm battery manned continually with fire control radars constantly in operation. The Marines found that early in the campaign the enemy pilots dropped their bomb loads as soon as they were fired upon or pinpointed by searchlights. Later attacks, however, were pressed home with determination, and only well-directed shooting deterred them.

Marines also had a prominent part in the artillery support of the NGOF. After registering on Munda field prior to the NGOF overland attack, the Marine 155-mm guns began a systematic leveling of all known enemy installations and bivouac areas. Since the exact location of the NGOF front lines was ill-defined most of the time, the Marine group left the close support firing missions to Army 105-mm units which were much nearer to the combat. The Marine guns were directed instead against rear installations, supply and reinforcement routes, and targets of opportunity.

Most of the firing missions were requested by NGOF headquarters with corrections directed by aerial observers or spotters at the 43rd Division observation post. The Marine group had notable success interdicting supply dumps, bivouac areas, and enemy positions in the immediate vicinity of Munda field. Cooperation between air spotters from the 192nd Field Artillery Battalion and the 155-mm Group of the 9th Defense Battalion reached such a high state of efficiency that missions were fired with a minimum of time and adjustment. The Marines were occasionally rewarded by the sight of towering columns of smoke, indicating that a supply or ammunition dump had been hit.

Ammunition problems plagued the 155-mm batteries. On the 13th of July, just as the NGOF stalled against General Sasaki’s defenses, an ammunition restriction was placed on the Marine batteries and the number of rounds expended dropped abruptly. After four days of limited firing, all shooting was stopped entirely while the NGOF reorganized in New Georgia. The only mission fired during this interval was on 20 July in answer to an emergency request to keep Japanese troops from moving back into an area which had been shelled and neutralized previously. The ammunition limitation resulted from powder becoming wet and unserviceable in containers broken from much handling. Further compounding the difficulties was the fact that during the period of ammunition scarcity, 11 miscellaneous

lots of powder were used which resulted in varying initial velocities. Marines could only guess from one shot to another whether the shell would be over the target or fall short. When the powder situation was remedied and the 43rd and 37th Divisions began the final drive for Munda, the Marine gunners, now experienced field artillerymen, returned to firing accurate missions.

After the fall of Munda, the 9th Defense Battalion began the move to New Georgia to help defend the newly won prize. Antiaircraft batteries were placed around the airfield and 155-mm gun positions established on offshore islands and at Diamond Narrows. The 9th was relieved on Rendova by the Marine 11th Defense Battalion, which moved to that island from Guadalcanal to take part in the final stages of the Central Solomons fighting.