Chapter 4: The Dragons Peninsula Campaign

Rice Anchorage1

Munda’s eventual capture was a triumph over initial frustration and failure. Admittedly, the campaign to take the airfield had been costly and time-consuming. But while the spotlight was focused on the New Georgia Occupation Force as it fought its way from Zanana Beach to the airstrip, another tense struggle was waged simultaneously in the northern part of the island in which the jungle combat was as bitter and as deadly. The results were much less conclusive. From the initial ship-to-shore movement of the Northern Landing Group through the following six weeks of fighting, this phase of the New Georgia campaign contributed as much to the feeling of disappointment and futility as the first Munda attacks.

Early plans of the NGOF called for Colonel Harry B. Liversedge’s 1st Marine Raider Regiment (less two battalions) to be a ready reserve. When intelligence reported a garrison of some 500 enemy troops with coast defense guns at Bairoko Harbor, the Kula Gulf landing was written into the attack order. Of prime concern to the Allied planners was the road connecting Bairoko with Munda airfield. Scarcely more than an improved jungle trail, the road was nevertheless a vital link between Munda and Vila, the main source of Japanese reinforcements and supplies. Bairoko Harbor was the knot which tied the overland route to the Kula Gulf barge system. An Allied ground force between Munda and Bairoko Harbor would have the double-barreled effect of cutting off the flow of enemy supplies and reinforcements to Munda as well as keeping the airfield forces and the Bairoko garrison from reinforcing one another.

Factors involved in risking a secondary attack north of the airfield had been carefully considered before a decision to land at Rice Anchorage at the mouth of the Pundakona (Wharton) River in Kula Gulf had been reached. Two areas—the Pundakona and the Piraka River in Roviana Lagoon—were scouted before the former was selected. Admiral Turner’s staff reasoned that a landing from Roviana Lagoon would be unopposed but that the resultant overland trek would be excessively slow, fatiguing, and difficult to resupply. Further, this landing would not bring the enemy under immediate attack. Despite the native trails crossing the island, a large force could not travel fast enough through the jungle to give assistance to the expected rapid seizure of Munda.

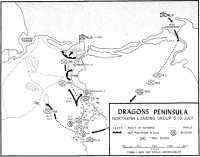

On the other hand, a landing at Rice Anchorage would likewise be unopposed, and the enemy could be taken under attack almost immediately. This would force the Japanese into one of three courses of action: withdrawal to either Munda or Vila, a counterattack in strength, or an attempt at defending the Bairoko Harbor area. The latter course, it was believed, would be the logical enemy reaction to such a threat to the Munda-Vila link. Defense by the enemy at Bairoko would keep that garrison from reinforcing Munda. Though the disadvantages of making a landing on a narrow, confined beach on the Pundakona River nearly outweighed the advantages, the Rice Anchorage attack held the most hope for success in dividing the Munda-Bairoko forces. (See Map 8.)

Liversedge’s group, augmented by the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry, was given a multiple mission in NGOF orders. After landing at Rice, the Northern Landing Group was to move overland to the southwest, capturing or killing any enemy forces encountered in the Bairoko and Enogai Inlet area. After establishing road blocks across all roads leading from Bairoko to Munda, the NLG was to advance along the Munda-Bairoko trail as far as possible to prevent any enemy supplies or reinforcements reaching Munda, and also to block any withdrawal from that area. Contact with the right (north) flank of the 169th Infantry was to be maintained by Liversedge’s command.

The Marine-Army force had only a limited knowledge of the terrain between Rice and Enogai Inlet and practically no information on Dragons Peninsula, the area between Bairoko and Enogai. For one thing, no oblique angle aerial photographs of the area were available. This type of aerial intelligence was particularly desirable, since jungle terrain photographed from high altitudes directly overhead rarely revealed anything of tactical value. In addition, the peninsula had not been scouted. The New Georgia guides had been reluctant to enter this area, fearing treachery because of vague rumors that the natives of this area were hostile to men from Roviana Lagoon.

Most of the SoPac reconnaissance patrols had been more concerned with Munda where the main effort of the NGOF was to be made. Those few patrols which ventured into the vicinity of Enogai Inlet were forced to turn back by close brushes with Japanese patrols. Only the long, narrow Leland Lagoon which borders the north shore of Dragons Peninsula had been patrolled, and this had been done in canoes. As a result, the dark stretches of jungle between Bairoko and Enogai were still an unknown area.

With the date of the landing set for 4 July, a one-day postponement was granted to allow another 37th Division unit, the 3rd Battalion of the 145th Infantry, to join Liversedge’s force. Unexpectedly, the 4th Raider Battalion was still engaged in the Viru Harbor attack and could not be withdrawn in time to join the NLG.

It was a lightly armed force. The only weapons carried, other than individual arms and light machine guns, were the 60-mm mortars of the raiders and the 81-mm mortars and heavy machine guns of the Army battalions. Noticeably lacking in artillery support, the NLG expected to have air power available upon request.

Shortly after midnight, 5 July, a covering bombardment of Kolombangara and Bairoko by a cruiser-destroyer force began on schedule. Prompt retaliatory fire from enemy shore batteries at Enogai surprised the task force, however, because the presence of large guns at Enogai as well as Bairoko had not been reported. In a matter of moments, part of the covering fires was shifted to these new targets and the bombardment continued. The destroyer Strong was the only task force casualty; it was hit at 0046, not by shellfire but by a torpedo fired by a Japanese destroyer running along Kolombangara’s northeast shore.2 The ship sank fast, but most of the crew was saved.

The actual landing of the Liversedge group started about 0130 in the midst of a torrential downpour and sporadic shellfire. For a short time the success of the amphibious venture seemed in serious doubt. Rice Anchorage could not be located in the darkness and rain. The transport group slowed and waited—uncomfortably remembering warnings of a lurking enemy submarine force—while one destroyer with a sweep radar probed ahead, seeking the anchorage. After a short delay, the Pundakona River mouth was located and the transport group moved into debarkation positions. As Marines and soldiers clambered into landing craft alongside the APDs, enemy star shells glimmered through the rainy darkness and shells splashed among the transports. This fire the raiders shrugged off with the comment, “erratic and inaccurate,”3 but it was disconcerting, too.

A shallow bar blocking the entrance to Rice Anchorage further delayed the landing operation. The landing craft, each towing 10 men on a rubber raft, were forced to return to the transports to lighten loads before crossing the reef. Some of the rations were unloaded before the boats returned for a second try. Scouting reports had termed the beach as “small.” The raiders found this almost an understatement to describe the narrow stretch of landing area hacked out of the jungle on the south side of the river, about 500 yards upstream from the anchorage. While four boats at a time beached to unload troops and supplies, the other boats jammed the river mouth or idled in Rice Anchorage waiting for a turn to unload. The black night obligingly curtained the milling confusion.

Ashore, drenched Marines and soldiers stumbled about the confined beach, slipping in the mud and tripping over hidden banyan roots. Since enemy shellfire ranged overhead to hit about 2,000 yards

Map 8: Dragons Peninsula, Northern Landing Group, 5–19 July

farther up the coast, Liversedge’s officers decided that the Japanese at Enogai were not aware of the exact location of the landing and risked the use of hooded flashlights. Thereafter, the unloading and reorganization proceeded more smoothly. Near dawn, with almost all supplies ashore, Colonel Liversedge broke radio silence with one uncoded word, “Scram.” The anxious APDs and destroyers, unhappily expecting enemy retaliation at any moment, quickly turned and headed back for the southern Solomons. The landing, although delayed, had been accomplished without serious mishap. One unit, an Army company, was taken to the wrong landing area; it went ashore farther north along the coast. The company rejoined the main body later in the day.

The NLG had been welcomed ashore by a mixed greeting committee. Heading a large group of native guides and carriers—who were obviously frightened and bewildered by the sudden influx of so many white men to their island—were an Australian coastwatcher, Flight Lieutenant J. A. Corrigan, and a Marine raider patrol leader, Captain Clay A. Boyd of Liversedge’s regiment. Corrigan had been on the island for some time, radioing reports of enemy activity in Kula Gulf and recruiting a labor force of nearly 200 natives. Small, wiry men with powerful arm, back, and leg muscles, the native carriers were to receive one Australian shilling, a stick of trade tobacco, and two bowls of rice and tea each day for carrying ammunition and rations for the NLG. A few spoke pidgin English, a jargon of simple words which bridged the language barrier. Colorful in cotton “lap laps” wrapped around their waists, they were intensely loyal to the coastwatchers.

Boyd had made several scouting trips to New Georgia. The last time, in mid-June, he and his men had remained with coastwatcher Harry Wickham to direct the landings at Onaiavisi Entrance and Zanana Beach before cutting across the island to link up with Liversedge. After the arrival of the NLG at Rice Anchorage, he resumed command of his company in the 1st Raider Battalion.

On one of his earlier trips, Boyd had scouted a trail leading from Rice to Enogai, and Corrigan’s natives had then chopped a parallel trail on each side of this track. After the NLG stacked all excess ammunition, equipment, rations, and blanket rolls in assembly areas prepared by the natives, the march to Enogai started over these three trails. Companies A and B of the 1st Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith, II) were assigned to move along the left trail (southern) with the demolitions platoon of the raiders heading along the right (northern) path. Thus protected on each flank, the main elements of the NLG started along the center trail with the remaining Marine companies leading and the two Army battalions following. Two companies, M and I, of Lieutenant Colonel George G. Freer’s 3/145 with a medical detachment, communications unit, and the antitank platoon remained behind to guard the supply dump.

Scouting reports had termed the Rice-Enogai area an open jungle with small, broken hills and few swamps. Rain-soaked Marines and soldiers, struggling over the sharp, irregular slopes made treacherous by the mud and hidden roots, could not agree. The meager trails, hardly more than narrow defiles gashed through the thick, sodden jungle, were trapped with sprawling banyan roots slick with

green moss, coral outcroppings, vines, and underbrush. The rain continued unabated.

The Army battalions, carrying heavier weapons and more ammunition and gear than the lightly equipped raiders, were forced either to travel at a slower pace or to stop to establish another supply dump. The soldiers, choosing to keep going, pushed on but dropped steadily behind. The leading NLG units, heading deeper into the New Georgia jungle on a course roughly south from Rice, reached the Giza Giza River late in the afternoon and set up a perimeter defense. Shortly after dark, all units were in bivouac on both sides of the Giza Giza. The NLG estimated that it had traveled eight miles during the first day. Actually, progress had been only about five miles, but undoubtedly the hardship of jungle travel had helped give every indication of greater distance. (See Map 8.)

That night, men of the Northern Landing Group listened to the distant sounds of a naval battle in Kula Gulf. A U.S. cruiser-destroyer force had intercepted a group of 10 Japanese destroyers, 7 of them transporting reinforcements. In a short but violent action, the U.S. force lost the light cruiser Helena. The Japanese lost two destroyers but managed to land 850 troops at Vila.

At daybreak on 6 July, the NLG stirred from its wet bivouac and resumed winding its way through the dripping jungle toward Enogai. The trails chopped by Corrigan’s natives ended abruptly at the river, and the Marines were forced to slash their way through the mangrove swamp lying between the Giza Giza and the Tamakau Rivers. Rain continued to drizzle through the jungle canopy. The battalions became one thin, straggling line snaking its way through the swamp on an indistinct trail. The rains drowned the radio equipment, and communication wire laid along the trail was grounded as the protective covering peeled off in the hands of the infantrymen who used the wires as guidelines. Runners carrying field messages kept Liversedge in contact with his base at Rice.

The NLG had divided into two segments early that morning. Lieutenant Colonel Delbert E. Schultz had been directed to take his 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry, along another trail to the southwest to cut the Munda-Bairoko road and establish a block there. The remainder of the NLG continued toward the Tamakau River. Captain Boyd, leading Marine Company D, reached the river shortly before noon. Much to his dismay, the small stream he had scouted early in June was now a raging, flooded torrent. The raiders and soldiers paused while equipment was carried across or ferried on rafts made from branches and ponchos. Then the infantrymen began crossing the river, single-file, over a fallen tree which bridged the swollen stream. A rope stretched from bank to bank provided an unsteady guideline, and strong swimmers fished from the river those individuals who were unfortunate enough to slip and plunge into the water.

The crossing delayed the NLG until late in the afternoon. While intermittent rains continued, the Liversedge force bivouacked for the night of 6-7 July in the midst of a swamp. Muddy and tired, the raiders and soldiers swallowed canned rations and huddled in wet ponchos under banyan roots, waiting for dawn.

Late that night, in answer to a plea from NGOF headquarters, Liversedge broke radio silence to give a progress report. A

listening watch had been set up at all halts, but the NLG commander had not used the radio in the hope that his cross-country march was still a secret. Although Liversedge carried medium-powered radios (TBX), contact with Hester some 20 miles away was made with difficulty. Such communication problems were to seriously handicap NLG operations. A high-powered radio, deck-loaded on one of the APDs, had not been unloaded during the anxious landing operations and was now back at Guadalcanal—a logistics oversight which was to be regretted many times.

First contact with the enemy came shortly before noon on the 7th of July. Liversedge’s wet and hungry men struggled out of the swamp early in the morning and moved along a tortuous ridge paralleling the west bank of Enogai Inlet. The delay caused by the Tamakau and the swamps was emphasized when the sounds of an air strike at Enogai were heard. This had been the designated day for Liversedge’s assault of that strongpoint. After moving through the native village of Maranusa I without incident, the point platoon of the NLG suddenly encountered seven Japanese riflemen. Surprise to both forces was apparent, but the Marines recovered first. In a brief fight, two of the enemy were killed before the rest fled. Uniforms identified the dead as members of the SNLF, probably from the Kure 6th, at Enogai.

Realizing that the fight had warned the Enogai garrison of an attack through the back door, Liversedge increased the speed of the advance. Griffith was directed to take his raider battalion forward as quickly as possible to take advantage of any remaining element of surprise and to screen the advance of the rest of the force. The next brush with the enemy came as suddenly as the first. The demolitions platoon, meeting a strong enemy patrol, withdrew slightly to high ground and engaged the Japanese in a hot fire fight. Boyd’s Company D then flanked the enemy and killed 10 before the Japanese fled. The brief fight cost the raiders three killed and four wounded. By nightfall, Griffith’s Marines had occupied the native village of Triri on Enogai Inlet. Liversedge’s CP was set up at Maranusa I with the NLG reserve units, Companies K and L of the 145th Infantry. Hasty perimeters were placed around each village.

The absence of defensive works at Triri further convinced the Marines that the Japanese at Enogai had not been expecting an attack from the direction of the inlet. The only item of value found at Triri was a detailed enemy map which pinpointed the location of four 140-mm guns at Enogai. As Griffith’s battalion prepared hasty defensive positions, the document was rushed to Liversedge at Maranusa I. The NLG commander immediately radioed for an air strike to knock out these weapons, but his message failed to raise a response from either NGOF headquarters or the 43rd Division. An Army radio station at Viru, hearing the request for a relay, accepted the message for transmission to ComAir New Georgia.

Early on the morning of 8 July, Griffith hurried two platoons down divergent paths north and west from Triri to ambush any enemy probing attacks. The Marines on the west trail scored first. A Japanese patrol of near-company strength, blundering along the trail without advance security, walked into the trap.

Premature firing, however, spoiled any surprise effect and the enemy withdrew without difficulty. Within a few minutes, a full-scale counterattack had been directed at the Marine ambushing party, and Griffith rushed Boyd’s Company D forward to help hold the trail. In the meantime, Colonel Liversedge picked up his command post and the two Army companies and rushed to Triri to be closer to the conflict.

The fight continued for three hours, the close jungle terrain handicapping the observation and maneuvering of both forces. Company C (Captain John P. Salmon), moving forward to relieve Company D under fire, broke the deadlock with a 60-mm mortar barrage and continuous machine gun fire. As the raiders moved forward, the enemy disengaged and fled down the trail. Fifty dead Japanese were left littered about the scene of the fight.

The Marines did not pursue. Enogai was the first objective. While the Army companies took over the defense of Triri, the raider battalion hastily reorganized and resumed the march toward Enogai along the north trail where the second ambush force had set up. The trail, however, ended abruptly in an impassable swamp. Reluctantly, after considerable time had been spent in trying to find an acceptable trail to Enogai, the battalion commander ordered the return to Triri for another start the following day.

Meanwhile, the Japanese force had reinforced and reorganized for another attack on Triri. Late on the afternoon of the 8th, an estimated 400 Japanese struck quickly at the left flank of the thin perimeter established by the two Army companies. The lines of Company K of the 145th slowly began to give way under the continuing pressure of the enemy assaults. Company L, on the right, received only scattered sniper fire. The demolitions platoon of the raider battalion, which had remained behind with Liversedge’s CP, rushed to assist Company K in its defense just as Griffith’s battalion returned. On orders from Liversedge for a quick counterattack, Griffith directed First Lieutenant Robert Kennedy’s platoon from Company B to circle back and hit the left flank and rear of the Japanese. Kennedy’s countermove completely surprised and crushed the enemy’s left flank. The Japanese fled once more. Another 20 enemy dead were left behind. Company K, which had three soldiers wounded, estimated that 75 additional Japanese had been killed in the attempted breakthrough. Kennedy’s platoon suffered no casualties.

Capture of Enogai4

After a quiet night at Triri, the Marines again started toward Enogai the following morning. A radio team with a TBX and headquarters personnel of the raider regiment remained behind with the Army companies, but Liversedge moved out with Griffith’s battalion. The raiders had more luck this day. A good trail, apparently unknown to the Enogai garrison, was discovered and rapid progress was made by the Marines. Sounds of an air strike at Enogai indicated that the request for the destruction of the enemy guns there was

Casualties from the fighting on Dragons Peninsula are readied for evacuation from Enogai by PBY. (USMC 182121)

Column of Marine raiders crosses a jungle stream near Enogai during the active patrolling in August. (USMC 60166)

being executed. Shortly before noon, Leland Lagoon was sighted and the Marine battalion turned east toward the enemy defenses at Enogai Point. After several hours of cautious approach, the raiders were halted by the stutter of two light machine guns. The Marines paused for battle orders. As they waited, the volume of enemy fire picked up. The Enogai defense line was being reinforced.

The attack was made without mortar preparation—Company A (Captain Thomas A. Mullahey) with its left flank resting on the lagoon, Salmon’s Company C in the center, and Company B (Captain Edwin B. Wheeler) on the right flank. Boyd’s Company D was held in reserve. The frontal assault, made with grenades and machine guns, was beaten back. With the jungle daylight fast closing into deep twilight, Liversedge called off the assault. Griffith was told to hold in place and resume the attack the following morning.

The Marines’ defensive positions, facing commanding ground, were not to Liversedge’s liking, but the NLG commander wanted to keep the pressure on the enemy during the night and decided to risk a Japanese counterattack. The gamble paid off. The night passed without incident except for the sudden crash of a huge, bomb-weakened banyan tree in the command post area which crushed one raider, injured three others, and completely smashed the command’s TBX.

Breakfast on the morning of the 10th was not a problem for the raiders who had not eaten since the morning of the 9th. There was no food. After a few quiet orders from Griffith, the 1st Raider Battalion renewed the attack. Wheeler’s Company B on the right front reported no opposition and moved forward rapidly. Companies A and C, as expected, however, were hit by intense fire from rifles and automatic weapons. The two companies paused for a 60-mm mortar barrage to soften the enemy line before plunging on. Company B, at last meeting strong defensive fire, raced through a small native village on the inlet’s shore south of Enogai. Dead enemy were sprawled throughout the village. A number of machine guns were taken and turned about to put more fire on the fleeing Japanese. The breakthrough put raiders almost in the rear of the enemy lines. Opposition facing Company C in the center abruptly faltered, then scattered.

As enemy resistance began to crumble, the raider attack gained momentum. Behind a withering fire of automatic weapons and machine guns, the raiders moved through Enogai. Mortarmen, in positions on the high ground overlooking the village, dropped 60-mm mortar shells along the shoreline of Kula Gulf, trapping the village defenders between two fires. Stragglers, attempting to swim across Leland Lagoon, were machine gunned by the raiders. By early afternoon, the coast defense positions were in raider hands, and only two small pockets of enemy resistance remained. These the Marines contained, postponing mopping-up operations until the next day. Late that afternoon, Company L of the 145th struggled into Enogai, each soldier carrying rations, bandoleers of ammunition, and three extra canteens of water. Without food for more than 30 hours, the raiders had been reduced to catching drinking water in ponchos during the intermittent rains.

The food was part of an air drop which the rear headquarters at Triri had received early on the morning of the 10th. Liversedge had requested the drop the previous day. The original three-day supply of rations

carried ashore at Rice Anchorage had been stretched over five days, and fresh water was also scarce. Wounded were fed wormy rice which had been found at Triri. The situation had become tense—so serious, in fact, that the Marines were far more concerned with the prospect of continued diminished rations than they were with the threat of having another enemy garrison in their rear at Bairoko.

Anxiety increased when the planes appeared over Triri on schedule but could not locate the purple smoke grenades marking the NLG positions. An air liaison officer finally made contact with the planes and directed the air drop. Parachutes drifted down, and soldiers and Marines dodged the welcome “bombing” to collect the bulky packages. The first containers opened held only mortar shells, and the troops howled their disappointment. K-rations and chocolate bars soon followed, however. An immediate relief party was organized to carry supplies and water to Griffith’s battalion, then hotly engaged at Enogai.

That night the Marines dined on K-rations and Japanese canned fish, rice, and sake. The captured enemy rations were liberally seasoned with soy sauce found in several large barrels. Articles of Japanese uniforms were used to replace the muddy and tattered Marine uniforms. The evening passed without further activity, the Marines resting easily behind a perimeter defense anchored on Leland Lagoon on the right flank and Enogai Inlet on the left. The defenses faced toward Bairoko. During the night, Japanese barges were heard in Kula Gulf and the raiders scrambled for positions from which to repel an enemy counterlanding. The Japanese barges, however, were only seeking to evacuate stragglers from the sandspit between Leland Lagoon and Kula Gulf.

The following morning, mop-up operations began with Companies A and D moving quickly through the two remaining points of opposition, although Company D was hard-hit initially. Only a few Japanese were flushed by the other patrols, and these the Marines killed quickly. The 1st Raiders now owned all of Enogai Point between Leland Lagoon and the inlet. Japanese casualties were estimated at 350. The raiders, in moving from Triri, had lost 47 killed in action and 74 wounded. Four others were missing and presumed dead. The wounded were placed in aid stations housed in the thatched huts at Enogai.

The four 140-mm naval guns, three .50 caliber antiaircraft guns, and numerous machine guns, rifles, and small mortars were captured, in addition to large stocks of ammunition, food, clothing, two tractors, and a searchlight. Allied bombardments and bombings had not materially damaged any of the Enogai installations.

The Japanese retaliated quickly on the morning of the 11th with a bombing attack which lasted for more than an hour and left the Marines with 3 more men killed and 15 wounded. Three American PBYs were called in that afternoon to evacuate the more seriously injured, and, after landing at Rice Anchorage, the big flying boats taxied along the shoreline to Enogai where the wounded were loaded aboard from rubber rafts. Shortly before takeoff, the PBYs were bombed and strafed by two enemy floatplanes. The Marines on shore fired everything they had at the attackers, including small arms and captured weapons, but the Japanese

went unscathed and the PBYs hastily departed for Guadalcanal. On the same afternoon, headquarters personnel of Liversedge’s CP arrived at Enogai and, at 2100, seven landing craft from Rice made the initial supply run into the inlet.

Trail Block Action5

After splitting with Liversedge’s main force early on the morning of 6 July, Lieutenant Colonel Schultz started his 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry down a trail which his sketch map showed would put him in position to intercept Japanese traffic over the Munda-Bairoko trail and establish the road block which Liversedge had directed. The Army battalion was hardly on its way down the new trail when one of Corrigan’s native guides—looking at Schultz’ map—insisted that the map was wrong. The Army commander, relaying this information to Liversedge by field message, reported that he was going to press on in the hope that the trail would cross the Munda-Bairoko trail at some point.

The soldiers moved down the inland trail without undue difficulty; the ground was more rolling and less swampy than in the coastal area. Crossing the Tamakau proved no problem farther upstream, and, late on the afternoon of 7 July, Schultz informed Liversedge that he had reached a trail junction which he believed to be the main Munda-Bairoko trail and that a block would be established the following morning. Footprints on the trail, evidence of recent use, convinced Schultz that he had indeed reached his objective. He also requested that rations be carried to him, and reported that the native carriers had become apprehensive and had returned to Rice.

The next morning, 8 July, Schultz set up his road block. Company I defended the approach from the north and Company K the approach from the south. Company L filled in a thin perimeter between I and K.

The first enemy contact was made shortly after 1300 when a squad of Japanese, sighted coming down the trail from the north, was taken under fire. The fight was brief, the enemy quickly fleeing back toward Bairoko. Two hours later a full-scale attack by 40 to 50 Japanese hit Company I’s outposts, driving them back into the perimeter, but the enemy did not penetrate the battalion’s defenses. The afternoon’s engagement cost the Japanese about 7 killed and 15 to 20 wounded. One American was killed and three others wounded.

After a quiet night, Schultz sent patrols forward on each trail in an attempt to locate the enemy. No contact was made in either direction, although an abandoned enemy bivouac area was discovered about two miles down the Munda fork of the trail. Schultz also tried to contact the 169th Regiment, by this time supposed to be well on its way to Munda field. Unknown to Schultz, neither force was in position to make contact. That night, after listening to reports from his patrols, Schultz reported to Liversedge that he believed himself to be about six miles north of Munda.

Early on the morning of 10 July, the battalion was hit on the right flank by about 50 Japanese and then on the left flank by a larger force of about 80 men. Both probing attacks were repulsed, the

Japanese losing 14 killed in the two skirmishes. After a number of similar searching attacks, the Japanese suddenly unleashed a strong attack on the right flank at the junction of Companies I and L. The Army positions were quickly overrun, but an orderly withdrawal was made. The Japanese force, estimated at more than two companies, quickly occupied a small ridge and set up a number of automatic weapons and heavy machine guns.

Company K hurriedly organized a strong counterattack with the battalion’s reserves, but the enemy’s hold on the rise remained intact. An 81-mm mortar barrage, which Schultz directed to be placed along the ridge, kept the enemy from continuing the attack further. The following day, 11 July, Company K attacked again toward the ridge, but was driven back. A later attempt by the same company was also repulsed. Casualties, however, in both attacks were few. That night, Company K was hit in return by a bayonet charge. The banzai attack was beaten back with only three soldiers being wounded.

Schultz’ force, by now just as ill-fed and unkempt as Griffith’s battalion, was on 1/3 rations. The food problem had become more acute on the afternoon of the 11th when Company I of the 145th Infantry arrived from Triri to reinforce Schultz’ battalion. A food drop that same afternoon had been greatly disappointing. As Schultz had predicted in an early report to Liversedge, the jungle prevented aircraft from spotting either flares or colored panels. Consequently, the air drop was wide of the mark. Schultz’ men, engaged closely with the enemy, could recover only a few of the packages, and these contained mostly mortar shells. Most of the ammunition was found to be outdated and of the wrong caliber, and nearly all the rations were spoiled. Little of either could be used.

The next morning, Company I of the 145th moved up to the rear of the 148th’s positions and then lunged forward toward the ridgeline, following a heavy machine gun and mortar preparation. The position had been abandoned. The absence of any dead or wounded enemy indicated that the withdrawal had been effected during the night. The positions around the trail block were restored, and, with the arrival of some natives with rations from Triri, the situation began to look brighter. Defense of this area had cost Schultz 11 killed and 31 wounded. Japanese casualties were estimated at 150.6

Enogai: 12-19 July7

Another attempt by the Japanese to reinforce Vila and Munda through Kula Gulf was partially blocked shortly after midnight on 12-13 July. An Allied force of 3 cruisers and 10 destroyers ambushed 4 enemy transports escorted by several destroyers and a light cruiser. Enemy torpedos damaged two U.S. cruisers, the Honolulu and St. Louis, and the New Zealand

cruiser Leander, The U.S. destroyer Gwin was sunk, and two others were damaged slightly in a collision. The Japanese lost only one cruiser in the engagement, and managed to land 1,200 troops on Kolombangara. The battle, however, persuaded the Japanese to abandon further attempts to run the gantlet of Kula Gulf. Thereafter, the enemy resorted to attempts to sneak barges through the waters west of Kolombangara. The battle also lessened the threat of a counterlanding against Liversedge’s force.

At Enogai, the possibility of such an enemy attempt had been considered and the defenses of the captured village strengthened and extended. Marines strung captured barbed wire from Enogai Inlet across the point to Leland Lagoon and constructed defensive positions behind this line, but the Japanese did not attempt to regain the area. Enemy bombing attacks, too, became less frequent.

Enogai became the new NLG command post. Liversedge directed that supplies at Rice Anchorage be moved to the new CP, and, with the exception of a small detail, 3/145 moved to Triri. Rice then became a relay point where APDs anchored to unload supplies into landing craft. The busy small boats then skirted the shoreline to Enogai, carrying supplies to the NLG and evacuating wounded on the return trip.

For some time, Liversedge had been concerned about his tactical situation. His original orders had given him the dual mission of capturing or destroying Japanese in the Bairoko-Enogai area while blocking the Munda-Bairoko trail, but the distance between his command post at Enogai and Schultz’ trail block was too great for effective control. A new landing area on the upper reaches of Enogai Inlet made resupply and evacuation of the trail block easier by eliminating much of the overland hike, but the combined boat trip and march still took considerable time. Moreover, General Hester on 9 July had insisted that Liversedge keep his battalions within supporting distance of each other. So, as soon as Enogai had been captured and a defensive perimeter established at Triri, the Marine colonel turned his attention to the trail block where Schultz’ battalion had suddenly found itself facing first a determined enemy of considerable strength and then no enemy at all.

Following the withdrawal of enemy forces from the trail block area on 12 July, no further Japanese troops had been encountered. Combat patrols, hitting along the Munda-Bairoko trail in both directions, failed to make contact. With Munda under heavy attack, this seemed surprising since it appeared logical that the Japanese would make some attempt to reinforce the airfield. Disturbed by the reports from the trail block, Liversedge sent his operations officer Lieutenant Colonel Joseph J. McCaffery, to check Schultz’ position. McCaffery left Triri on the morning of the 13th accompanied by part of the regimental staff and the 145th’s Company K.

He later radioed Liversedge that the situation at the trail block was “okay,” and that the defense of the trail was tight and not split as had been reported. Rations were needed badly, since natives could not carry enough supplies to support the augmented trail block force and the front lines could not be weakened to supply carriers. An air drop was requested.

By this time, however, Liversedge was already en route to the trail block for a

personal reconnaissance. The NLG commander left Enogai with a small patrol on the 15th of July and, after bivouac on the Triri trail, joined McCaffery and Schultz early on the morning of the 16th. One day at the defensive position was enough to convince Liversedge that the trail block should be abandoned. Schultz’ battalion, unable to contact the 169th and at a considerable distance by boat and foot from the supply base at Enogai, was definitely out on a shaky tactical limb. Moreover, 3/148 was in a weakened condition, and many soldiers were ill from eating contaminated food. Their ability to ward off a sustained attack was questionable. Resupply was a problem, too; very little of the rations dropped were recovered. The intended purpose of the trail block seemed to have been served:–

The presence of our force at the road block since 8 July had materially assisted in the capture of Enogai by holding enemy forces at Bairoko in position and preventing them from reinforcing their Enogai garrison. It further established the fact that the enemy was not using the Bairoko-Munda trail as a supply route.8

On the morning of the 17th, executing Colonel Liversedge’s orders, Schultz directed his battalion to abandon the trail block, and the two companies of the 145th Regiment and 3/148 retraced the path to Triri. There the soldiers changed clothes, bathed, and ate a good meal after nearly two weeks in the jungle. Their rest was to be short-lived, though.

At Enogai, the Marines, now rested and well-supplied, had been actively patrolling the trails toward Bairoko. Enemy contacts after the capture of Enogai had been limited to an occasional brush between opposing patrols, which resulted in brief fire fights with few casualties to either side. The raiders lost one killed and one wounded during the period 13-17 July. Japanese planes, however, continued to make Rice Anchorage and Enogai a favored target. Each night enemy floatplanes droned over the NLG positions to drop bombs from altitudes of about 500 feet. No damage was inflicted, and no casualties resulted.

Patrol reports definitely established the fact that the Japanese intended to defend Bairoko Harbor. Several patrols reported glimpses of Japanese working parties constructing emplacements and digging trenches east of the harbor. Two-man scouting teams, attempting to get as close to Bairoko as possible, returned with the information that the high ground east of the Japanese positions had not been occupied by the enemy and that two good trails leading to this area had been found. The scouts reported that a battalion could reach this position in two and one-half hours. There was still no reliable estimate of the size of the defending force at Bairoko, however.

Upon his return from the trail block on the 17th, Liversedge was greeted with the news that Lieutenant Colonel Currin’s 4th Raider Battalion would arrive the next day to augment the NLG. The NLG commander had requested this reinforcement shortly after the capture of Enogai. Major William D. Stevenson, the regiment’s communication officer, had hitchhiked a ride on one of the PBYs carrying casualties out of Enogai on 11 July and had gone to Guadalcanal to relay Liversedge’s request personally to Admiral Turner.

Tentative approval for the reinforcement was given. After conferring with Currin, Stevenson returned to Enogai with supplies and mail.9

Early on the morning of the 18th, four APDs anchored off Enogai Point and the 4th Marine Raiders debarked, bringing additional supplies and ammunition with them. Liversedge, who had expected a full battalion, was taken aback when Currin reported his battalion nearly 200 men understrength. The captures of Viru Harbor and Vangunu, as well as recurring malaria, had taken their toll. Liversedge put the NLG sick and wounded aboard the APDs to return to Guadalcanal and turned his attention toward the seizure of Bairoko Harbor. The orders were issued late that afternoon, after a conference with his battalion commanders at the Enogai CP.

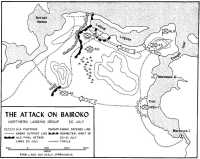

Approach to Bairoko was to be made by two columns. Two full-strength companies (B and D) of the 1st Raider Battalion and the four companies of the 4th Raider Battalion were to make the main effort, advancing along the south shore of Leland Lagoon straight toward Bairoko and the north flank of the Japanese positions. Schultz’ battalion was to move from Triri toward Bairoko to hit the south flank of the Japanese positions. Freer’s 3/145 was to remain in reserve at Triri and Enogai. The departure time was set for 0730, with an air strike scheduled for 0900 to precede the actual attack on the harbor defenses.

As soon as Liversedge’s orders had been given, Schultz and Freer returned to Triri, and Currin and Griffith began a last reconnaissance. A reinforced platoon from Wheeler’s Company B under the command of Second Lieutenant William J. Christie moved down the sandspit between Leland Lagoon and Kula Gulf to get into position for the morning’s attack and to protect the seaward flank. At 1600, an air strike by 18 scout bombers and 19 torpedo bombers pounded the east side of Bairoko Harbor while 8 mediums strafed Japanese supply dumps and bivouac area. The strike marked the fourth time since 15 July that Bairoko had been worked over by ComAirSols planes.

That night Enogai was rocked in return by enemy bombing and strafing attacks that lasted nearly seven hours. Ten Marines were wounded. The NLG wondered: Had the enemy accurately guessed the date for the NLG attack or were the Japanese just giving as good as they had received in the air attacks of the previous days? If the former, enemy intelligence work had been much better than the NLG’s.

Although the Liversedge force knew the general location and nature of the Japanese defenses at Bairoko, there was a disturbing lack of intelligence about the size of the Japanese garrison. The prelanding estimate had been about 500 enemy at the harbor. The 350 Japanese encountered and killed at Triri and Enogai were identified as members of the Kure 6th SNLF. Schultz’ attackers at the road block had not been identified, but were believed to have been from the Bairoko garrison. The NLG concluded—wrongly—that only about two reinforced companies held Bairoko.

At the time of the Rice Anchorage landing, Enogai was lightly defended by a detachment from Commander Okumura’s Kure 6th SNLF. When Liversedge’s force split on the second day, the Japanese

believed that two regiments were attacking Dragons Peninsula and ordered half of the 2nd Battalion, 13th Regiment from Vila to Okumura’s assistance. The reinforcements included a machine gun company. The new troops were to have been rushed to Enogai to defend the coast defense guns but the move was made too late. By the time the 2nd Battalion units reached Bairoko, Enogai had been captured. When Liversedge’s intentions to continue the attack toward Bairoko became more evident, more reinforcements were rushed to the harbor. These included several companies of the 2nd Battalion, 45th Regiment and the 8th Battery of the 6th Field Artillery Regiment which had recently arrived from Bougainville.

Since contact with the enemy had been negligible after the capture of Enogai, the NLG had no basis for comparison of strength and were not aware of the added enemy capability to defend Bairoko. Patrols did not aggressively test the Japanese defenses; in fact, no probing attacks against the outposts guarding Bairoko were attempted. The only enemy prisoner taken during this period was a badly burned pilot, rescued from an offshore island and immediately evacuated. In effect, the NLG was facing an unknown quantity in its attack against the harbor.

“I Have Committed the Works”10

The approach to Bairoko by the raiders began over trails and terrain now familiar through much patrolling. Wheeler’s Company B led the approach march with Company D (now commanded by First Lieutenant Frank A. Kemp, Captain Boyd having been evacuated with malaria), the demolitions platoon, Currin’s 4th Raider Battalion, and the regimental command post following in column. The two companies in the 1st Battalion had been brought up to near-full strength for the attack by taking men from Companies A and C. These understrength companies remained behind with the 145’s Company L at Enogai. (See Map 9.)

As the NLG file moved through the dripping jungle, scrambling over sharp coral rocks and climbing low but steep hills and ridges, the Marines waited to hear the first sounds of bombing and strafing which would indicate that the 0900 air strike on Bairoko’s defenses was being executed. The raiders waited in vain—there would be no strike.

Unknown to Liversedge, his request was apparently made too late. The support strikes by ComAirSols for 20 July were already scheduled and the planes allotted. The NLG commander, however, did not know this. Considerable difficulty was encountered in transmitting the message on the afternoon of the 19th, but the message was finally cleared. Scheduling of the strike was not confirmed, Liversedge’s communication officer recalls:

Acknowledgment was requested, as I remember, but this acknowledgment did not come until night. It was actually nothing more than an acknowledgment of the receipt

of the message by the staff officer on duty at the headquarters addressed.11

Without air support, the odds for success in capturing Bairoko lengthened considerably. Disappointed but determined, the two Marine battalions kept moving forward.

The first shots came shortly after 1015. A Japanese outpost opened fire on the NLG column, and Wheeler and Kemp quickly deployed their companies into attack formation. The outpost was overrun. Without pause, the raiders continued forward, feeling their way through the tangled jungle. At 1040, Griffith informed Liversedge by message that he was deployed and pushing forward against several machine guns.

Five minutes later, the raiders were in a violent, all-out battle. A sudden eruption of intense and accurate fire from close range raged at them. The Marine attackers were pinned down, closely pressed against banyan roots, logs, and coral outcroppings, unable to move against the withering fire from automatic weapons and machine guns which raked the jungle. Recovering quickly, the Marines returned the fire, the battle racket becoming louder. As the intensity of the firing increased, the din was punctured by hoarse shouts and curses as the Marines tried to maneuver against the murderous fire pouring from the jungle facing them.

Confronting the raiders was a series of log and coral bunkers dug into the rising ground under banyan roots, and well camouflaged with palm fronds and branches. The ridge ahead blazed with fire from these low fortifications. Similar to those encountered by the NGOF in its approach to Munda, the emplacements supported each other with lanes of interlocking fire. Further protection was furnished by Japanese soldiers in trees overhead who sniped at the Marines with Nambu (.25 caliber) light machine guns. Okumura had prepared his defenses well.

The pitched battle went on, both sides firing at a rapid rate. Wheeler’s company, with its right flank near the end of the lagoon, was unable to move forward and could not make contact with Christie’s platoon on the sandspit. Heavy firing across the lagoon indicated that Christie, too, was engaged. Kemp’s company, on the left, finally regained fire superiority, however, and began to inch forward in an attempt to take high ground to the front. As casualties began to mount in both companies, Griffith moved his sole reserve unit—the demolitions platoon under Marine Gunner Angus R. Goss—to the left flank for protection from attacks from that direction. At 1105, after 20 minutes of furious combat, Griffith reported to Liversedge: “Harry: I have committed the

Map 9: The Attack on Bairoko, Northern Landing Group, 20 July

works. ... Movement forward continues. Sam.”12

By noon, the first line of enemy resistance crumbled, broken under the relentless pressure of the raider units. Unable to use the 60-mm mortars because of the jungle canopy, lacking the new flame-thrower weapons, and without air or artillery support, the Marines breached Okumura’s defensive line by knocking out first one pillbox and then another by demolitions and overwhelming small-arms fire. But losses were heavy and progress was slow.

Shortly after noon, with the 1st Battalion clearly needing quick assistance, Liversedge committed Currin’s battalion to the fight. Company P (Captain Walker) was in close support behind Griffith’s battalion, and thus able to move quickly into the line. Kemp’s Company D, which had moved steadily ahead despite numerous casualties, was receiving heavy fire on its left flank and Walker now attacked toward this opposition. Goss’ demolition platoon, in turn, circled through the rear of the 1st Battalion to take up a new position on Kemp’s right flank to bridge the gap between Company D and Company B.

Walker’s fresh company, under orders to attack southwest to the shores of the inlet before turning north to hit the enemy’s right flank, was barely able to move forward before criss-crossing fire from both right and left flanks held it back. While Walker scouted his front lines to determine the location of the machine guns facing him, Captain Snell moved his Company N into position behind Walker’s unit to refuse the left flank and support Walker’s attack. The battle continued in full fury all along the line, the raider gains measured a yard at a time. Contact with the platoon on the sandspit still had not been made. Christie’s unit, facing a marshy swamp backed by a strong line of Japanese fortifications, could not advance. Seven enemy machine guns, pouring a deadly fusilade over the swamp and along the shores of the sandspit, resisted every attempt at forward movement.

In the next two hours, the raider attack slowly punched through two different defensive lines, uncovering a number of bunkers on the reverse slopes. Company D, riddled with casualties by the heavy and continuous enemy fire, scrambled to the top of a ridge line which overlooked the harbor at Bairoko, about 500 yards away. But between the raiders and their objective lay another series of formidable fortifications. Hoping to cement Kemp’s position on the commanding terrain, Liversedge directed First Lieutenant Raymond L. Luckel’s Company O into the gap between Company D on the ridge and Company P. Both companies had been hit hard by several machine guns in this area, and Luckel’s company was ordered to silence these weapons. As Company O lunged forward, the maneuver reduced fire on Company P and Company N. Walker and Snell then moved their companies forward to take a small ridgeline to the left front.

At this time, the NLG front lines arched in a wide U pointed towards the harbor with Company D as the leading unit. On the left flank, Currin had three companies, bent around to the southwest. Griffith’s two companies and the demolitions platoon, on the right, had managed to move nearly to the end of the lagoon, but a slight gap still existed between the

battalion and the lagoon’s shoreline. Liversedge, in an attempt to plug this gap and try once more to contact Christie, moved First Lieutenant Leonard W. Alford with a reinforced platoon from Company O to this flank. Alford’s platoon made a spirited attack, but the volume of enemy fire prevented movement beyond that of Wheeler’s company. The move, however, tied Christie’s platoon closer to the main NLG line.

At 1445, sporadic but accurate mortar fire from enemy positions on the inlet suddenly changed into an intense barrage that shook the attacking lines. The Marines, without weapons for counterbattery fire, could only press closer into their shallow positions behind scant cover on the ridge lines and try to weather the pounding. Estimated to be 90-mm rounds, the shells inflicted further casualties, mainly from tree bursts overhead. The barrage was immediately followed by a screaming counterattack. Kemp’s company, bearing the brunt of the enemy charge, was pinned between searing fire from the front and the mortar shelling. Withdrawing to the first ridge taken, Kemp organized a counterattack of his own, and with a badly depleted company stormed back to his old position in a sudden rush. The quick conquest was the first visible crack in the Japanese defenses. Marines reported the enemy fleeing, many of them without weapons. Griffith sent a hasty note to Liversedge, advising the NLG commander that the addition of just one company (L of 3/145) would take Bairoko by night. The Japanese, Griffith believed, were on the run, but casualties were heavy among the raiders and reinforcements would be needed.

Unfortunately, there were no ready reserve units. Nothing had been heard from the Army battalion which was supposed to hit the south flank of the enemy, but sounds of firing from that direction indicated that Schultz was engaged. Freer’s battalion, scattered between Rice, Triri, and Enogai was not in position to help, even if those bases could have been left unguarded. Company L at Enogai had been ordered to the front lines with ammunition, rations, and blood plasma at 1400, but had not yet arrived. Liversedge would have to take the Japanese position with the troops already at hand.

Following Company D’s return to its former position, the 4th Battalion found movement easier, and Companies N and P managed to move forward in the face of stiffening fire to extend the NLG lines more to the southwest. But the move was costly; both companies received heavy casualties. Company Q (Captain Lincoln N. Holdzkom), the sole remaining company as yet uncommitted, moved up to the rear of the other three 4th Battalion units to be in position for an attack when directed.

By 1600, the Japanese had been pushed, still defiant and dangerous, into an area on the Bairoko Harbor headlands about 300 yards wide and 800 yards long. Their back to the sea, the enemy defenders kept up a sustained and murderous machine gun and mortar fire that showed few signs of slackening. In an effort to strike one last, conclusive blow, Liversedge ordered Company Q into the lines. Holdzkom’s company moved around the left flank of Company N in an attack straight into the teeth of heavy enemy fire. Action along the rest of the front line dwindled as the fury of the attack on the south flank increased. Now all combat units had been committed; only the demolitions platoon of Currin’s battalion remained as security for the command posts in case of an enemy breakthrough. Wheeler’s Company B,

requesting reinforcements for a last attack, was told that no help was available.

The outcome of Liversedge’s last attempt to take his objective was not long in doubt. Despite the vigor of Company Q’s attack, the overwhelming fire of the enemy won. Badly depleted in a matter of moments, Company Q was forced to retire. Repulsed, the company reeled back, virtually noneffective through its losses. The tactical situation had been opportune for one last heavy punch to knock out the enemy defenders, but without artillery, air support, or other heavy weapons, the raider battalions could not deliver it.

During the early part of the Marines’ attack, Colonel Liversedge heard nothing from Schultz, who was supposed to have hit the enemy’s other flank. From his command post just behind the raiders’ front lines, the NLG commander tried to contact Schultz by telephone to order registration of the battalion’s 81-mm mortars on the harbor’s defenses. The wires, however, were dead, apparently grounded somewhere in the relay linking Liversedge to Enogai and then to Schultz. And, in this crucial moment, the TBXs carried by the raider regiment failed to reach even the short distance back to Enogai. Chagrined by the absence of contact with 3/148, and desperately needing assistance in his bid to capture Bairoko, Liversedge, at 1345, directed McCaffery to take a small patrol and try to contact Schultz as soon as possible. For the operations officer, this entailed a rugged trip to Enogai, then a boat ride to Triri, and a subsequent march to Schultz’ position.

The first word Liversedge had from Schultz, a field message from Enogai at about 1500, was not encouraging:

Harry: Steve [Stevenson] has contact with Dutch. Dutch has been hit 3,400 yards from Triri. Steve told Dutch to keep pushing and try to connect with our outfit. Artillery fire is falling between Rice and Triri. LaHue.13

Schultz’ battalion had departed Triri on schedule that morning, Company K leading the column down the Triri-Bairoko trail. Progress was slow, the heavy machine guns and mortars carried by the soldiers adding to the difficulty of movement over the slippery jungle terrain. By noon, the battalion had reached a point on the trail where enemy positions had been reported, but the Japanese had apparently evacuated the area. The only enemy contact was a glimpse of a Japanese patrol of about 15 men moving hurriedly down the trail ahead of the column, but no shots were fired. Shortly afterwards, however, the chatter of an enemy light machine gun sent the column off the trail. Several probing attacks were made to determine the enemy position, and at 1515 Schultz sent a message to Enogai for relay to Liversedge:

Light Horse Harry: Have met Nips about 3½ miles down trail. Have not yet hit Munda–Bairoko trail. Strength of enemy undetermined, but know they have four automatic weapons. We are attacking. Will keep you informed as situation develops. They hold high ground to our front. Dutch Del.14

Schultz then moved his companies into attack formation and ordered a mortar barrage on the Japanese positions. The

preattack bombardment was to start at 1600. Enemy strength, Schultz decided, was about one company. Shortly after the mortar barrage began, Liversedge was able to contact Schultz directly by telephone and advise him of the situation that faced the Marines on the right flank. Schultz must establish contact with the main positions at Bairoko—and soon—Liversedge told him, or the attack on Bairoko would fail.

The Army commander, not knowing whether his present attack would succeed, reported that he did not think it possible that contact with the Marine units could be made before nightfall. McCaffery, who had reached Schultz after the attack had been started, could only urge that Schultz push forward as rapidly as possible. The battalion’s attack carried forward only a few hundred yards before stiffening enemy resistance stopped the advance. Schultz then ordered his men to dig in and hold the ground taken. He had, he figured, reached a position from which he could launch an attack the following morning.

For Liversedge, Schultz’ failure to attack aggressively on the left flank was the final blow in a series of sharp disappointments. To his front, the battle din had subsided into an uneasy calm broken occasionally by the stutter of a machine gun or the sharp report of a rifle. While both forces—the Japanese compressed into a corner and the Marines clinging tenaciously and tiredly to shell-pocked ridges won through sacrifice and courage—waited for the next move, Liversedge asked Griffith to reconnoiter the front lines and report what action could be taken. Griffith’s recommendation: withdraw.

By this time the Raiders (1st and 4th) had nearly 250 casualties, or about 30 percent of the force. We had another 150 men tied up getting them evacuated to aid stations and to Enogai. There was nothing to do but pull back to reorganize, re-equip, get some rest, try to get something to cope with the Jap 90-mm mortars, and get the wounded out.

The decision to pull back was made by Harry the Horse on recommendation from me after I had talked to Currin and his and my company commanders and had made a personal reconnaissance of the front. Harry had a mission and was understandably loath to abandon it. The final determining factor was the Japanese capability to reinforce from Vila Stanmore during the night by barge. We were already up against a stone wall, low on ammunition and out of water, and had a responsibility to 200 wounded men. In any case, reorganization was a paramount requirement. I feel that the decision to withdraw was entirely sound and the only sensible one to have made.15

Victory had been close. At 1630 Griffith had joined Kemp on his hard-won ridgeline overlooking Bairoko. The harbor was about 300 yards away—but still unattainable. For more than seven hours, the raiders had been in continuous attack, trading punch for punch with the enemy and had almost won. Exhausted and nearly out of ammunition, with almost as many men wounded as were still fighting, the raiders could only retire, carrying their dead and wounded. The positions won through courage and indomitable will could not be held during the night because there were no other troops ready to pick up the fight. Regretfully, Liversedge ordered the withdrawal of his forces.

The retirement began shortly after 1700. First to leave were the litter cases, about 90 in number. Marines from the battalion and regimental headquarters companies carried the wounded off the ridgeline in crude stretchers made from folded

ponchos and tree branches. The walking wounded followed, a thin stream of lurching, bloody men who had remained in the fight despite injuries. While Companies N and P held the main positions, Company Q pulled back. Companies O and D disengaged next. Despite a continued spatter of enemy mortar and machine gun fire, the retirement was orderly, Marines assisting the wounded and each other whenever necessary. As they moved back, the men salvaged weapons and ammunition which had been dropped in the fight.

As the abrupt jungle darkness closed in, the rest of the raider companies disengaged to retire to the high ground east of the end of the lagoon. A rough defensive perimeter was set up both flanks resting on the lagoon. Company L of 3/145, which arrived at 1800 with badly needed medical supplies and water, also moved into the defensive line. Christie’s platoon, pulled back a short distance on the sandspit, blocked a possible enemy counterattack from that direction.

After seeing 80 walking wounded start the long and tortuous night march back to Enogai, the Marines settled down into an uneasy rest in their shallow foxholes. That night Liversedge made another request for air support. To forestall any swift counterattack by the Bairoko defenders, the NLG commander asked that the area between the NLG perimeter and the harbor be worked over by a bombing and strafing attack the next morning. Liversedge then concluded his request with: “You are covering our withdrawal.”16

The night of 20-21 July passed with only one enemy attack to test the hasty perimeter. A light Japanese force attempted to penetrate the defenses on the west flank, but was repulsed by Companies B and D in a sharp fight that wounded nine more Marines and killed another. Four dead Japanese were found the next morning.

At dawn on the 21st, another group of walking wounded started toward Enogai where three PBYs waited. The main body of the NLG followed, the Marines carrying the more seriously wounded men on stretchers. Shortly after the grueling march began, a group of Corrigan’s natives appeared to take over the stretcher bearing. Progress was slow and exhausting as the natives and Marines, burdened with extra weapons and packs, labored over the rough terrain. A stop was made every 200 yards to rest the wounded and the carriers. The main body of troops had gone about halfway to Enogai when the Marines were met by Company I, 3/145, which had hurried from Triri to take over the rear guard. The rough march was further eased when a number of the wounded were transferred to landing craft about halfway down Leland Lagoon. After that, the march speeded and by 1400 all troops were within the defensive perimeter at Enogai. Christie’s platoon, which retired down the spit, also arrived without incident.

Schultz, who had been surprised at the abrupt change of events, had kept his soldiers on the alert for a morning attack if a switch in orders came. When the order for withdrawal was repeated, Schultz turned his battalion around and within several hours was back at Triri.

During the march toward Enogai, the Marines had been heartened by the sounds of continuous bombing and strafing attacks

at Bairoko. Although Liversedge’s request for air support the night previous had been received at 2244, well past the required deadline for such requests, the ComAir New Georgia headquarters apparently read the appeal in the NLG message and the request was passed to ComAirSols. Every available plane, including some outmoded scout planes, was diverted to attack the enemy positions at Bairoko. The strikes began at 0950 on the 21st and lasted until 1710, long after the raiders had reached the base at Enogai. In all, 90 scout bombers, 84 torpedo bombers, 22 medium bombers, and 54 fighter planes took part in the continuous air attack. A total of 135 tons of bombs were dropped on enemy positions, and strafing attacks by the mediums started a number of fires in supply dumps and bivouac areas. The only resistance by the Japanese was a flight of 17 fighters which attempted to intercept the last flight of medium bombers, but was driven off by the Allied fighter cover.

Evacuation of the wounded from Enogai continued despite attempts by Japanese planes to strafe the big, lumbering PBYs which landed in Enogai Inlet. The interruptions delayed, but did not halt, the removal of wounded for hospitalization at Guadalcanal. With all the troops in bivouac at Triri or Enogai, a sobering count of wounded and dead was made. The 1st Battalion with two companies in the attack had lost 17 killed and 63 wounded. Currin’s battalion counted 29 dead and 137 wounded. In the action along the trail south of Bairoko, Schultz lost 3 killed and 10 wounded.17

The raiders had faced an estimated 30 machine guns in coral and log emplacements, cleverly camouflaged with narrow, hard-to-detect firing slits. Only 33 enemy dead had been counted during the day-long attack, but the evidence of much blood in the bunkers which had been reduced indicated that the Japanese casualties had been considerably higher.

The following day, 22 July, Liversedge received orders from Griswold to remain at Enogai and Rice Anchorage. Active patrolling was to be continued, and the NGOF was to be apprised of any hostile troop movement from Bairoko to Munda. Evidently, no further attempt to take the well-fortified harbor would be made for a while. With these orders, the conflict on Dragons Peninsula settled down to a state of cautious but active watchfulness.

Occasional fire fights flared as opposing patrols bumped into each other, but close contact between the two forces was infrequent. The Japanese reclaimed the high ground overlooking Bairoko and reconstructed their fortifications. Evidently hoping to keep the NLG off balance, the enemy harassed the Enogai positions nightly with bombing attacks by one or more planes. Some nights the number of such attacks or alerts reached as high as seven. The Allies, meanwhile, pounded Bairoko with short-range shelling from three destroyers on 24 July and bombed the harbor defenses on 23 and 29 July and 2 August. For the most part, however, the operation reverted to a routine of enervating patrolling and air raid alerts. Of particular benefit was a rest camp established by Corrigan’s natives near Rice Anchorage where Marines were able to relax for three days away from the weary monotony of patrols and air raids.

End of a Campaign18

The virtual stalemate on Dragons Peninsula ended on 2 August. The XIV Corps, poised for a last headlong breakthrough to Munda field, directed the NLG to rush another blocking force between Munda and Bairoko to trap any retreating enemy. After a hurried night conference with his battalion commanders, Liversedge ordered Schultz’ battalion on a quick march down the Munda-Bairoko trail from Triri. The 4th Raider Battalion, at Rice, returned to reserve positions at Enogai and Triri. Schultz’ battalion, leaving Triri on the 3rd, moved quickly past its old positions abandoned on 17 July to another trail junction farther southwest. Here he established a road block. On 5 August, as Munda fell, Liversedge joined him with a reinforcing group (Companies I and K) from the 145th Infantry and a reinforced platoon from each of the two raider battalions. The first enemy contact came on 7 August when a patrol from Schultz’ battalion encountered Japanese building a defensive position and killed seven of them.

Contact between the forces capturing Munda and Liversedge’s command was made on 9 August when a patrol from the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Ryneska, appeared at Schultz’ road block.

The following day, 10 August, on Griswold’s orders, operational control of the NLG passed to the 25th Division. Control of Schultz’ battalion passed to the 27th Infantry, and Ryneska’s battalion joined the NLG in Schultz’ place. Leaving the road block position to be defended by Ryneska’s outfit, Liversedge and his Marine-Army force returned to Triri and Enogai. There the Marines had been actively patrolling to determine if the enemy was preparing to make another determined stand at Bairoko. Heavy barge traffic, however, and lack of aggressive resistance indicated that Bairoko was being evacuated. Meanwhile, the nightly enemy air raids continued with practically the same results as before: “No casualties, no damage, no sleep.”19

On 9 August, a light antiaircraft battery from the 11th Defense Battalion arrived at Enogai. The 50 Marines with 40-mm antiaircraft guns and .50 caliber machine guns were a welcome addition to the base’s defense. The first night that the battery was in action, the 40-mm guns scored a hit on a surprised Japanese plane which hurried away trailing smoke. The gleeful Marines scored the hit as a “probable.” Thereafter, the nightly enemy raiders climbed considerably higher; and as the altitude increased, the accuracy of the bombing decreased.

The final assault on Bairoko was made on 24 August after two regiments of the 25th Division (161st and 27th) had pushed inexorably toward the last Japanese stronghold. In the late afternoon of 24 August, Ryneska—whose battalion had advanced steadily toward the objective on the Munda-Bairoko trail—sent a message to Liversedge that he was one hour’s

march from the southern end of the harbor and that he was going into Bairoko on the following morning “come hell or high water.”20 Ryneska’s message was followed by another message from the 3rd Battalion, 145th (now commanded by Major Marvin D. Girardeau) which had advanced from Enogai over the raiders’ route of 20 July. A company from that battalion reported that it had entered Bairoko without opposition. The harbor had been evacuated. Composite raider companies, formed from the effective members of each battalion, were in reserve at Triri and Enogai but were not needed for the final phases. The long fight for Bairoko was over.

On the 28th, General Collins, commanding the 25th Division, arrived at Enogai and after an appraisal of the situation ordered the Marines withdrawn. That night and early on the 29th of August, the raiders went aboard APDs. By 1130 on the 30th, the raiders were back at Guadalcanal. The last entry in the 1st Raider Regiment Journal, at midnight of 31 August 1943, is significantly eloquent: “1st Marine Raider Regiment relaxes (bunks, movies, beer, chow).”21

The Marine raider battalions which returned to Guadalcanal were a pale shadow of the two units which had originally been assigned to the NLG. Malnutrition, unavoidably poor sanitary conditions, exposure, fatigue, and continued loss of sleep and malaria had taken their toll. Battle casualties had been unexpectedly high—25 percent of the total command of the 1st Battalion, 27 percent of the 4th. Griffith’s battalion had lost 5 officers killed and 9 wounded, with 69 enlisted men killed and 130 wounded. Currin’s battalion, in three operations (Viru, Wickham, and Bairoko) had 2 officers killed and 8 wounded, 52 enlisted men killed and another 160 wounded. Of the 521 men remaining in the 1st Battalion, only 245 were judged effective by battalion medical officers. Only 154 Marines out of the 412 officers and men in the 4th Battalion could be classed as effective. The doctors concluded that further commitment to combat at this time was impossible:

Not more than fifty percent of the present personnel would be able to move out on a march without extreme exhaustion and of these, the undermining of physical and nervous stamina has been so great as to render none of them capable of exerting sixty percent of their usual offensive effectiveness.22

Conclusions

The contributions of the NLG to the eventual success of the New Georgia campaign appear slight in a postoperational review. The trail block, as originally situated, lost all surprise value and usefulness after one engagement. The Japanese did not contest its presence further, and simply moved reinforcements to Munda over another route. As later reconnaissance proved, the actual location of the trail block should have been another 1,200 yards farther southwest at the junction of the main Munda-Bairoko trail.

Liversedge’s force, in attacks on Enogai and Bairoko, inflicted a large number of casualties on the enemy and forced the Japanese to commit additional troops to the Dragons Peninsula area—troops which the enemy could have used to advantage in the defense of Munda. This,

perhaps, was the principal benefit derived from the NLG’s operations at Enogai and Bairoko.

The failure of the attack on Bairoko can be ascribed to the burden of handicaps under which the NLG labored—lack of intelligence, poor communications, the vital need for supporting air and artillery, and insufficient support from higher echelons. Each handicap, in its turn, contributed to the eventual failure.

Operational planning was handicapped by the failure of the NGOF in making maps, mosaics, and aerial photographs available to the NLG prior to the landing. Other than the operational mosaic, the Liversedge force received only one high-level stereographic set of prints of Bairoko, which revealed nothing. And, as Liversedge later pointed out, no provision was made for the NLG to receive further intelligence.23

Realistic estimates as to enemy strength and reinforcement capabilities were lacking. On a par with the assumption that Munda would be captured in a matter of days was the equally poor reasoning that the Japanese would not stoutly defend against an attack on their major port of entry into New Georgia. Pre-attack patrolling by the Marine and Army battalions was extensive but, as Liversedge admitted, not aggressive enough to force the enemy to reveal the added strength of the Bairoko defenses.

The serious disadvantage imposed by communication failures in the dripping jungle balked the operation constantly. Contact with NGOF headquarters at Rendova was difficult, and NLG messages usually had to be relayed by a variety of stations, including those at Segi and Guadalcanal. Not all the communications woes were equipment failures, however. In some instances, transmission of messages was refused. After Enogai was captured, Liversedge reported, permission to transmit three urgent messages to the NGOF was not granted, and the NLG was directed to clear the message with another station, unknown to the NLG. The urgent messages to the NGOF were finally cleared after 15 hours of waiting.24

The attack on Bairoko, started and continued without air bombardment, the only supporting weapon available to the NLG, raises questions which existing records do not answer. Since his request for air preparation on the objective had apparently been rejected and there was no assurance that another request would be honored, Liversedge undoubtedly believed that a higher echelon had deemed air support unnecessary for the attack. As the next day, 21 July, was to prove, however, air support—and lots of it—was available. The only restriction, apparently, was that requests had to reach the headquarters of ComAirSols on Guadalcanal before the end of the working day.

Another question unanswered was the complete absence of any supporting artillery. Although it would have been impossible to pull artillery pieces through the jungle from Rice to Enogai, there seems to be no reason why artillery could not have been unloaded at Enogai after that village was captured. It is believed that one battalion of 105-mm howitzers could have been spared from the many battalions then at Munda. Based at Enogai, these guns would have made a vast difference in the attack on Bairoko.

Naval gunfire support, as known later in the war, was at this point, in mid-1943 still in the exploratory stages; “reliable, foolproof communications and the development of gunnery techniques for the delivery of accurate, indirect fire from afloat onto unseen targets”25 ashore had not been fully worked out yet. As before, records do not indicate the reasons why Allied planners waited until after the repulse at Bairoko to plaster that enemy point with air and naval bombardments.