Chapter 5: End of the Campaign

Baanga and Arundel1

In a matter of days after its seizure by the NGOF, the airfield at Munda—shell-cratered, with stripped and fire-blackened palm stumps outlining the runways—was converted to an Allied base for further operations in the Central Solomons. Almost as soon as enemy resistance around the airfield was ended, the busy bulldozers of the Navy’s construction battalions were smoothing the coral landing strips and repairing revetments for use by ComAirSols planes. As the 25th Division turned north to follow the enemy’s withdrawal toward Bairoko, the 43rd Division took over defense of the airfield and began mop-up operations on the offshore islands.

Separated from New Georgia by only a few yards of shallow water, Baanga Island north of Munda Point was a ready-made sanctuary for Japanese fleeing the bigger island. As such, the densely-wooded appendage was a stepping stone along the Japanese route of retreat. The original island garrison had been small—about 100 Army and Navy troops—but the general exodus from Munda swelled the population. Tag ends and remnants of Munda’s defenders fled to the island either to go overland toward Arundel or await evacuation by barge. (See Map II, Map Section.)

On 11 August, as the 43rd Division widened its cleanup efforts around the airfield, a patrol confirmed reports of Japanese activity on Baanga. The following day, a company-sized unit moved by landing craft to the island. As the soldiers disembarked, a withering fire from the jungle felled about half of the force and forced its withdrawal. Two days later, while an artillery barrage from 155-mm guns hastily-emplaced at Munda paved the way, two battalions of the 169th made an unopposed dawn landing on the shore opposite the site of the ill-fated assault of the 12th. As the infantrymen moved inland, crossing the island from east to west, resistance stiffened. An estimated 400 Japanese manned a strong line of hastily-built fortifications blocking the advance.

On 16 August, two battalions of the 172nd Regiment went to Baanga to reinforce the attack. As more artillery units (including the 155-mm gun batteries of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion) moved into

position at Munda and on the offshore islands, and systematically knocked out every known enemy gun emplacement, resistance dwindled. Increased barge traffic on the night of 19 August indicated that the Japanese were withdrawing. The following day, the southern part of the island was quickly occupied, and two battalions then moved north along opposite coastlines. Only scattered stragglers were encountered; the enemy had abandoned Baanga. The 43rd Division lost 52 men killed and 110 wounded in the week-long battle.2

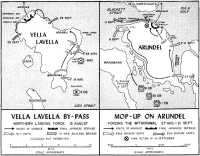

Contact with the Japanese was reestablished on Arundel. One of the smallest of the major islands in the group and virtually unoccupied by the Japanese except as a barge staging base, Arundel was within easy distance of both New Georgia and Kolombangara. Its eastern shore bordered Hathorn Sound and its northern fringe of narrow reef islands was just 1,200 yards from Kolombangara—a strategic position which became increasingly important to both forces. For the Japanese, the island was an important outpost to Kolombangara and an invaluable evacuation point. The NGOF wanted the island because Arundel in Allied hands would bring Vila airfield within range of artillery. (See Map 10.)

On 27 August, troops from the 172nd Infantry crossed Diamond Narrows from New Georgia and landed unopposed on the southeastern tip. After securing the southern part of the island, the landing force split into two reinforced companies to begin extended patrol action north along the east and west coastlines of Arundel.

As on New Georgia, the dense jungle and large mangrove swamps made travel difficult. First enemy contact was made by the east shore patrol on 1 September south of Stima Lagoon. Pushing on, the patrol fought its way through brief skirmishes and delaying actions without trouble. To help cut off the retreating enemy, the 2nd Battalion of the 172nd established a beachhead near the lagoon and reinforced the eastern patrol. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion moved by LCMs through Wana Wana Lagoon to link up with the western patrol which had reached Bustling Point on the northwest coast without so much as seeing an enemy soldier. The beachhead on that coast was then expanded to include the extreme western end of Bomboe Peninsula.

When the 2nd Battalion’s attack near Stima Lagoon on 5 September was abruptly halted by fierce enemy resistance, the 3rd Battalion was landed to reinforce the effort. Neither battalion, however, was able to penetrate the enemy’s strong line of defense which included mine fields and booby traps as well as many machine guns. Artillery fire from Kolombangara supported the defense. The arrival of the 1st Battalion from Bustling Point, where a battalion of the 169th had assumed responsibility for the western beachhead, placed the entire 172nd Infantry on the east coast and paved the way for the commitment of the 27th Regiment (25th Division) on Bomboe Peninsula. Two batteries of 155-mm howitzers and a 4.2-inch chemical mortar company also landed at Bustling Point to support the 27th Regiment on that coast, while NGOF artillery on New Georgia emplaced on the shores of Hathorn Sound delivered counterbattery fire on Kolombangara to support the 172d’s attack on the east coast. Of the two infantry regiments, however, only the 27th Infantry was relatively fresh, although its

rifle companies were seriously understrength and its men “well seeded with malaria.”3 The 172nd had been through nearly two months of arduous fighting and was badly understrength.

While troops from the 169th held the Bustling Point area, the 27th Infantry on 12 September opened a drive east along the length of Bomboe Peninsula. The leading battalion, restricted to a narrow strip of island only 400 yards wide and unable to make a flanking attack, could only grind straight ahead when it ran into stiff opposition. Small gains with mounting casualties were the inevitable results.

As the front lines inched abreast of Sagekarasa Island, which parallels Bomboe Peninsula, a second battalion swam and waded across a lagoon to establish another front on that island. Unable to erase the beachhead in a series of screaming counterattacks that night, the Japanese then hurriedly evacuated their barge base on the extreme western tip of the island. Sounds of barge traffic each night, however, indicated that the enemy still had other bases on Stima Peninsula which could be used to resupply and reinforce the Arundel defenders.

By dusk of 14 September, the two battalions of the 27th were in secure positions astride Sagekarasa Island and Bomboe Peninsula while the 172nd Infantry pressed slowly northward along the east coast. In the gap between, stragglers from the 229th and a battalion from Tomonari’s 13th Regiment fought determinedly to hold Stima Peninsula and a corner of Arundel’s northeastern coast.

On the night of 14-15 September, the remaining battalions of the 13th Regiment on Kolombangara were loaded on barges for transfer to Arundel to begin a counteroffensive which was supposed to regain the initiative in the Central Solomons. Undaunted by the loss of Colonel Tomonari and two battalion commanders who were killed by American artillery fire as their barge beached on the Arundel coast, the Japanese unleashed a near-fanatical attempt to break out of the perimeter. The desperation thrust failed. The 172nd and 27th, reinforced quickly on line by troops from the 169th, contained the attack although the battle was touch-and-go for some time. As the attack subsided, the Japanese reverted once more to delaying tactics to preserve their thin foothold on Arundel. The repulse decided the Japanese upon withdrawal from Arundel and eventual evacuation of the Central Solomons.

The counterattack, however, resulted in Marine Corps tanks joining the 43rd Division. Alerted earlier for possible commitment, the tank platoons of the 9th, 10th, and 11th Defense Battalions moved their remaining 13 serviceable machines by LCM from Munda to Bomboe Peninsula on the 16th. While the tanks of the 9th and 10th went into bivouac, five tanks of the 11th Defense Battalion moved up to help the 27th Regiment in the Bomboe Peninsula area. The armored attack on 17 September took the Japanese by complete surprise. The heavy jungle rains apparently drowned the noise of the tanks clanking into attack position. Moving forward in two waves with infantrymen following, the Marine tanks crunched through the enemy defenses before abruptly turning to the left in a flanking

Map 10: Vella Lavella Bypass, and, Mop-up on Arundel

maneuver to complete the rout of enemy in that sector. Infantry units advanced about 500 yards in the attack. The following day, however, as four tanks and an infantry company jumped forward in another assault, the enemy suddenly opened point-blank fire with 37-mm antitank guns. Two of the 11th Defense Battalion tanks were knocked out of action, but, quick and effective covering fire by the infantry allowed the tank crewmen to escape. The attack stalled.

On 19 September, the remaining effective tanks—two from the 9th, four of the 10th—joined those of the 11th. Lined up in two ranks virtually tread to tread they started toward the enemy lines. The rear rank covered the front with fire. Concentrated blasts of 37 mm canister rounds and bursts of machine gun fire from the leading tanks withered the jungle ahead, stripping foliage from the enemy positions and hewing out an avenue of attack. Behind this shield of firepower, the infantry advanced rapidly. Afterwards described by 27th Infantry officers as one of the finest examples of tank-infantry coordination they had seen, the attack moved quickly and steadily forward.

This fearsome mass assault, coupled with the Japanese decision to quit Arundel, settled the fight for the island. That night, despite near-continuous artillery and mortar barrages, Japanese barges began evacuating the bulk of Arundel’s defenders. While enemy artillery fire from Kolombangara kept the two American regiments from closing in, the remainder of the 13th Regiment was withdrawn the next night. On 21 September, with only a few overlooked stragglers to contend with, the NGOF declared Arundel secured.

Instead of being a routine mopping-up job, the fight for Arundel had unexpectedly developed into a major operation which required the principal elements of three infantry regiments as well as armored and artillery support. Japanese losses in three weeks of fighting were 345 counted dead, although the enemy must have lost considerably more. Countless shallow graves dotted Arundel’s northern coast, and the lagoons and Blackett Strait yielded many other bodies of enemy dead who had been killed in evacuation attempts or had drowned attempting to swim to Kolombangara.

Allied losses for the island’s capture were relatively light, 44 killed and 256 wounded. Army observers credited the timely support of Marine Corps tanks for abruptly terminating the campaign and preventing the loss of additional Allied lives.

Vella Lavella4

With Munda taken and the Allied drive slowly turning toward Vila airfield, the Japanese in mid-August had every right to expect that the decisive battle in the Central Solomons would be fought on the big, volcanic island of Kolombangara. But Admiral Halsey, a former Naval Academy halfback, knew the value of an end run in warfare as well as in football. Ten days after Munda was captured, the Allies skirted the strongly defended positions prepared by the enemy on Kolombangara and hit at lightly-held Vella Lavella.

The decision to switch targets was made a month earlier. On 12 July, just six days after asking for Admiral Turner’s plans for Kolombangara, Halsey changed his mind and directed that this island be sidestepped and Vella Lavella taken instead. By this time it was obvious to the staff of ComSoPac that Munda was not going to be taken as quickly as estimated and that the island of Kolombangara, with nearly 10,000 entrenched defenders, would be even harder to take. Further, Vila airfield was reported to be poorly drained and poorly situated. If a better airfield site could be found, the chance to land virtually unopposed at Vella Lavella would be a much sounder tactical move.5

A reconnaissance team which scouted the island in late July returned to report that the southern end of the island near Barakoma drained sufficiently well to enable construction of an airfield there, and that there were adequate beaches, bivouac areas, and MTB anchorages in the area. Vella Lavella, the patrol reported, differed little from New Georgia. A dense jungle of tangled creepers and huge trees covered the island from coastline to the low but sharp mountain peaks in the interior. One of the most developed islands in the group before the war, Vella Lavella’s European-type buildings included a hospital, several missions, and a leprosarium. (See Map 10.)

Coastwatchers on the island added to the report. Only about 250 Japanese were estimated to be occupying the northern part of the island where Vella Lavella’s irregular coastline provided many coves for protection for barges shuttling between Kolombangara and Bougainville. The natives on the island had remained friendly to the Allies, and were well organized. They had, in fact, aided the many survivors of the USS Helena who had managed to swim to the island and had assisted in their evacuation by fast APDs on 16 July.6

On 11 August, orders were issued by ComSoPac for the seizure of Vella Lavella by Admiral Wilkinson’s Task Force 31. The forces on New Georgia were directed to continue the cleanup operations in the Munda area and to interdict Vila airfield by artillery fire. The Allies had decided that enemy troop concentrations on Kolombangara did not necessitate an attack, that neutralization of the island would be as effective as occupation and not as costly in terms of troop casualties or supplies.

Further, soggy Vila airfield was no longer deemed worthy of capture.

The Northern Landing Force (NLF),7 organized to attack and occupy Vella Lavella, comprised the Army’s 35th Regimental Combat Team which included the 64th Field Artillery Battalion, the 58th Naval Construction Battalion, and the Marine 4th Defense Battalion, as well as additional Army and Navy support units. Brigadier General Robert B. McClure, the 25th Division’s assistant commander, was named to head this organization.

Embarkation of major units began at Guadalcanal on 12 August. That same night, an advance force landed near Barakoma to mark channels and landing beaches and to select bivouac areas and defensive positions. After being forced to fight their way to shore, however, through fire from a motley collection of survivors from sunken barges, the reconnaissance group hurriedly requested reinforcements. The next night an infantry company landed to help them.

The main landing force departed Guadalcanal on 14 August on a split-second, staggered schedule. The slowest transport group, LSTs, started first and was passed later by the faster APDs. In this manner, the transports which had departed Gaudalcanal in reverse order arrived off Vella Lavella in the proper order and at the right time.

Debarkation of troops began at dawn on 15 August, the APDs unloading quickly in one hour. The first snag in the invasion schedule occurred when it was discovered that the beach could accommodate only 8 of the following 12 LCIs. The LSTs, which arrived later at the correct time, were forced to stand offshore waiting to unload. Limited beach areas had resulted in the very delay and exposure which it was hoped the staggered schedule would prevent. There was, however, no enemy opposition ashore. As the beachhead widened, soldiers reported scattered Japanese troops fleeing northward.

Shortly before 0800, just as the LCIs were in the unloading stage, the first of four frantic Japanese air attacks struck. After making one pass at the protective destroyer screen standing offshore, the enemy bombers and fighters turned their attack on the LCIs and LSTs, evidently figuring that the smaller transports carried the bulk of invasion troops and supplies. All four attacks were driven off by alert planes from ComAirSols and the fierce antiaircraft fire from the task force destroyers.

The fighter cover came from Munda airfield, which had begun operations only the day before. As a dividend for having won an airfield closer than Segi or Guadalcanal, the Allies were able to keep an umbrella over the beachhead most of the day. Despite the presence of this air cover, however, the Japanese persisted in sporadic attacks, striking from different altitudes and directions. The results were negligible. None of the ships in the convoy were damaged, and during the day more than 4,600 troops and 2,300 tons of equipment and supplies were unloaded at Barakoma. Twelve men were killed and 40 wounded in the day’s attacks. That night, as the convoy withdrew slowly down Gizo Straits, the ships fought off repeated torpedo attacks. Enemy floatplanes kept the area lit with flares.

The successful jump from Munda to Vella Lavella asserted Allied domination in the Central Solomons. Failing to repulse the landing, officers of the Eighth Fleet and the Seventeenth Army hastily called a conference to consider making a counterlanding on the island. One battalion was all that could be spared, it was decided. This proposal was promptly squelched by Eighth Area Army. Such a move would require at least two brigades, the higher headquarters decided; and, in view of the existing difficulties in reinforcing and resupplying other Central Solomons garrisons, the idea was better forgotten. The only help the stragglers on Vella Lavella received was reinforcement on 19 August by 290 Army and 100 Navy personnel.

The NLF beachhead expanded rapidly. Within the first 20 days of the operation, 6,505 troops, 1,097 tons of rations, 843 tons of gasoline and oil, 2,247 tons of ammunition, 547 vehicles, and 1,011 tons of other classes of supplies were landed. Shipping was to have been unloaded during night hours, but the attacks on the convoys in the narrow confines of Gizo Strait changed that schedule. After 18 August, the convoys arrived and departed Barakoma during daylight hours, protected during the unloading and passage through Gizo Strait by Allied planes from Munda.

There was little opposition to the advance of the NLF. By 18 August, the three battalions of the 35th Infantry had established a firm defensive perimeter across the southern end of the island. Behind this protective barrier, airfield construction began immediately. The Marine 4th Defense Battalion provided antiaircraft and seacoast defense.

As the fight for Vella Lavella progressed, the 35th began driving the enemy before it. Toward the end of August, increased resistance was met on the east coast near Lambu Lambu, and it was 15 September before the regiment’s assault battalions broke through the Japanese defenses to overrun the barge base at Horaniu on the northeastern coast. The enemy, however, escaped and fled north.

At this point, the 14th Brigade of the New Zealand 3rd Division landed at Barakoma with two infantry battalions, the 35th and 37th, as the main units. In a reshuffle of command, Major General H. E. Barrowclough of the 3rd Division was named as commanding general of all Allied forces on Vella Lavella. With the arrival of a third New Zealand battalion, the 30th, the American frontline troops were relieved. On 25 September, the colorful New Zealanders—the majority of whom disdained the use of steel helmets to wear their distinctive flat visored field hats—began their attack.

While the 35th Battalion leapfrogged around the west side of the island in a series of landings, the 37th Battalion began moving by landing craft up the northeastern coast, making landings at various points to cut off the fleeing Japanese. When cornered, the enemy soldiers fought stubbornly and fiercely for survival, but it was apparent that they were not under a single command or organized into a single unit.

By early October, the New Zealanders were in position to put the squeeze on the Japanese, who had been backed into a jutting piece of land between Marquana and Watambari bays. The two battalions of the 14th Brigade made contact and joined for the final push to crowd the enemy into

the sea. A Japanese prisoner reported that the tired and hungry enemy force was willing to surrender, but that Japanese officers would not permit it.

On the night of 6-7 October, Allied troops heard voices and the sound of barges scraping coral, but the supporting fires were ordered too late. The next morning, only littered stocks of Japanese equipment and supplies were scattered over the peninsula. The enemy cornered on Vella Lavella—589 by Japanese accounts—had been successfully withdrawn.

The New Zealanders had estimated that the Vella Lavella campaign would end in less than two weeks. The conclusion came several days early—one of the few successful timetables in the Central Solomons fighting. The 14th Brigade casualties totaled 32 killed and 32 wounded. Japanese losses for the defense of the entire island were about 250.

The price for an island of considerable strategic and operational value was not exorbitant. Allied casualties for the seven weeks of fighting were less than 150 killed, most of these in air attacks. The practice of bypassing a strong point to hit at a weaker point somewhere else was now established. Future Pacific operations followed the strategy initiated in the Aleutians and used with success in the Central Solomons.

Marines at Vella Lavella8

Success of the Rendova beachhead had proven the value of a Marine defense battalion in a landing effort. When the task organization to seize Vella Lavella was planned, the inclusion of a similar unit seemed logical. Closest and most available was the 4th Defense Battalion, then on Guadalcanal. Organized at Parris Island in 1940, the battalion was stationed at Efate, New Hebrides, before transfer to New Zealand, then Guadalcanal. Its organization was similar to other Marine defense battalions—155-mm seacoast artillery group, 90-mm antiaircraft group, a special weapons group of 40-mm, 20-mm, and .50 caliber weapons, and a tank platoon.

By nightfall of the first day ashore at Barakoma, about two-thirds of the light antiaircraft weapons were in temporary firing positions. Other guns of Major McDonald I. Shuford’s special weapons group were kept set up on two LSTs in the harbor, an innovation which increased the firepower of the beachhead. The addition was effective. A total of five enemy planes were claimed by the 4th the first day.

During the next six days, other echelons of the battalion arrived and moved into positions to defend the beach. Only the air defense units of the battalion got into action, however. The 155-mm gun groups, which moved ashore shortly after the original landings, were in coastal defense positions ready to fire within a few days, but the need never arose. The tank platoon

which landed on 21 August was never committed to action.

After the initial landings, the Japanese bombing attempts dwindled in frequency and ferocity. During the early part of the operation, the enemy attacks were pressed home with fanatical fury and many reckless planes were knocked spinning into Vella Gulf. Later the Japanese became more cautious, and fewer mass assaults were attempted. Since any activity at Barakoma was readily discernible from Kolombangara, the arrival of Allied ships was generally followed closely by a strike by a conglomerate force of enemy bombers, fighters, and float planes. Most of the attacks were less than vigorous, however, as the Japanese pilots soon gained a healthy respect for ComAirSols planes and the accurate shooting of the 4th Defense Battalion. By late August, those few enemy planes that did attack usually did not get close enough to bomb accurately.

During the Vella Lavella operation, 15 August to 6 October, the 4th Defense Battalion compiled an enviable accuracy record. During 121 different air attacks aimed at the island, the Marine antiaircraft gun crews knocked down the following: 90-mm gun group—20 planes; 40-mm batteries—10 planes; 20-mm batteries—5 planes; the .50 caliber weapons of the special weapons groups—4 planes; and the .50 caliber weapons of the seacoast artillery group—3 planes. The total: 42.

Other Marines, not part of the NLF, also took part in the Vella Lavella operation. After the 35th RCT moved past Horaniu, establishment of a Marine advance staging point on the island was ordered. Planning for the Bougainville operation was already underway, and the I Marine Amphibious Corps wanted a base closer than Guadalcanal to the Northern Solomons. On 17 September, the new Commanding General, IMAC, Major General Charles D. Barrett, who had taken command of the corps on the 15th, named Major Donald M. Schmuck to head the proposed Corps Forward Staging Area, Vella Lavella. The task organization included elements of the Marine 4th Base Depot, a motor transport company, a special weapons battery, a communication team, part of the Navy’s 77th Seabees, as well as two provisional infantry companies from the 3rd Marine Division. All told, the forward echelon of Corps Troops included 28 officers and 850 men.

The task force was to land at two points: Juno river and Ruravai beach, on Vella’s east coast. Part of the organization was to begin the establishment of a base camp while the combat elements provided local security. Hastily organized, the forward echelon made one practice landing at Guadalcanal before proceeding to Vella Lavella. On 25 September, troops went ashore by landing craft at Juno river while LSTs beached some three miles north at Ruravai beach.

Unloading at both points proceeded without incident until about 1115, when 15 Japanese bombers and about 20 fighters swept over. After one brief sideswipe at the destroyer screen offshore, the enemy planes turned toward Ruravai. Some 40-mm and .50 caliber antiaircraft weapons had been hastily set up on the beach, and these opened with a steady fire that was accurate and effective. Three bombers were downed and a fourth damaged. Two of the doomed bombers, however, managed to complete their bombing runs before crashing in the jungle. The other planes continued to bomb and strafe. One 40-mm crew and gun was destroyed by a

direct hit and a second crew knocked out of action. Volunteers quickly manned the second gun and continued the fire.

As the bombing attack ended, Allied fighter cover appeared to clear the sky in a series of running dogfights. But the landing area at Ruravai was a shambles. Exploding ammunition continued to wreak havoc. Casualties and damage to supplies were high. One LST had been sunk outright, others had been damaged. A total of 32 men on the beach had been killed and another 58 wounded.

The Japanese did not let up. Each day brought a number of pressing air attacks. Despite frequent interruptions, the construction of roads, LST beaching areas, and base installations continued. The work was further handicapped by wandering bands of enemy stragglers, which necessitated active combat patrols as well as increased guards at all construction projects. Progress, however, was fairly rapid.

On 1 October, as the second echelon of corps troops (including the 2nd Parachute Battalion), arrived, the Japanese struck another heavy blow. Four air attacks during the day resulted in further damage and more casualties. One LST was sunk and another damaged. The Japanese lost only one plane. Convinced at last of the futility of trying to land men and supplies over a beach inadequately protected against air attacks, IMAC then directed all further echelons and supplies to be unloaded at Barakoma under the protection of the guns of the 4th Marine Defense Battalion. The supplies were then trucked to Ruravai, where wide dispersal and increased aircraft defense measures ensured fewer losses.

After surviving a number of such severe air strikes during the next week (while Barakoma was studiously avoided by the Japanese), the Corps Staging Area was replaced on 8 October by the newly arrived Vella Lavella Advance Base Command. Some troops were returned to their parent organizations; others remained at the base under the new command. Ruravai was seldom used for its intended purpose, since most ships preferred the loading facilities at Barakoma. Later, however, the sawmills and hospital of the base command proved valuable during the Bougainville campaign by providing timbers for bridging and ready medical facilities for seriously wounded men. Its construction had proved costly, however. In the two weeks at Vella Lavella, the Forward Echelon had lost 17 men killed and 132 wounded during the many air attacks.

Japanese Withdrawal9

As the campaign in the Central Solomons drew closer to its inevitable end, the Japanese efforts during August and September became those of near-desperation. The Allied attack on Vella Lavella, which effectively shunted the enemy forces at Kolombangara to the sidelines of the war, had the added effect of nearly isolating Japanese garrisons from the main sources of supplies and reinforcements in the Northern Solomons. Aggressive action by Allied destroyer squadrons tightened the blockade. Camouflaged enemy barges, trying to keep the supply lanes open by sneaking along the coves and breaks of island coastlines were hounded and

New Zealand troops of the 14th Brigade land on Vella Lavella to relieve American soldiers battling the Japanese. (SC 184437)

Munda airfield after its capture and reconstruction, as seen from the control tower atop Kokengola Hill. (SC 233548)

harassed by the vigilant MTBs and the black-hulled Catalina flying boats (“Black Cats”) which prowled the waters of Vella and Kula Gulfs. Nearly stymied in their barge supply attempts, the Japanese finally resorted to supplying garrisons by floatplanes and submarines.

These inadequate measures and a careful second look at the strategic situation forced the enemy to make the only decision possible: general evacuation of all forces from the Central Solomons. The operation began with the removal of troops from the seaplane base at Reketa on Santa Isabel Island in early September. An Allied patrol, landed from an MTB on 3 September, verified the absence of enemy troops. Quantities of rations and ammunition found on shore indicated that the withdrawal had been hurried.

After scattered outposts on Gizo and Ganongga Islands returned to Kolombangara on the 19th and 23rd of September, the only remaining enemy troops were the small force defending Arundel, a sizeable body of troops on Kolombangara, and the stragglers back-tracking along the coast of Vella Lavella—about 12,000 troops in all, by Japanese estimates.

Weighing two factors—the direction of the Allied effort and the capability of the 13th Regiment on Arundel to conduct a delaying action—the Japanese scheduled the withdrawal for late September during a moonless quarter. The northern coast of Kolombangara was designated as the evacuation point. Landing craft from the Buin area, would ferry troops across The Slot to Choiseul for further transfer to Bougainville. Sick and wounded would be evacuated by fast destroyers.

The Japanese schedule began none too early. By 27 September the fighter airfield on Vella Lavella was operational although not yet completed, and enemy troops on Kolombangara were caught in a vise between ComAirSols planes at Munda and Barakoma. In addition, Allied 155-mm guns and howitzers emplaced on New Georgia’s northern coast were pounding a steady tattoo on Kolombangara’s defenses.

The effect of waning moonlight—plus the increased barge activity—was not lost on the Allies. By late September it became evident that all Japanese activity was directed toward withdrawal. Immediately, all available Third Fleet destroyer squadrons rushed with protecting cruisers into interception duty in Vella and Kula Gulfs.

The planned withdrawal began, but was disrupted many times by the sudden appearance of Allied planes and ships. On the night of 28 September, the Japanese managed to load 11 destroyers with 2,115 sick and wounded for a quick sprint to safety at Bougainville. Despite the Allied interference and considerable loss of small craft and men, the Japanese relayed another 5,400 men by landing barges to Choiseul during the next few dark nights and an additional 4,000 men were picked up by six destroyers. In the squally weather and murky darkness of the period, the Allied destroyers were hard-pressed to keep track of all enemy activity. In a number of instances, the destroyers had to choose between steaming toward targets which radar contacts indicated as small craft or heading towards reported enemy destroyer forces. Sometimes contact could not be made with either target. Allied ships, however, reported a total of 15 barges sunk on the nights of 29 and 30 September.

During the night of 1-2 October, all available Allied destroyers steamed through The Slot seeking the main Japanese evacuation attempt. Few contacts were made in the pitch darkness. About 20 of the 35 barges encountered were reported sunk. The following night the Allied ships again attempted contact with the Japanese but could not close to firing range. Aware that the enemy destroyers were acting as obvious decoys to lure the attackers away from the barge routes, the Allied ships abandoned the chase and returned to The Slot to sink another 20 barges.

Further enemy evacuation attempts were negligible, and the Allies reasoned that the withdrawal had been completed. A patrol landed on Kolombangara on 4 October and confirmed the belief that the Japanese had, indeed, successfully completed evacuation of all troops. Jumbled piles of supplies and ammunition attested to the fact that the enemy had been content to escape with just their lives. The withdrawal, the Japanese reported later, was about 80 percent successful, the only losses being 29 small craft and 66 men.

The final evacuation attempt was made on 6 October from Vella Lavella. A sizeable enemy surface force was reported leaving Rabaul in two echelons, and three U.S. destroyers moved to intercept the enemy. Another Allied force also hurried to the scene. Contact was made in high seas and a driving rain. In a fierce battle which lasted less than 12 minutes, the United States lost one destroyer to enemy torpedoes and two other destroyers were badly damaged. The Japanese lost only one of nine destroyers, and during the battle the transports managed to evacuate the troops stranded almost within the grasp of New Zealand forces.

The removal of troops from Vella Lavella ended the Japanese occupation of the New Georgia Group. The loss of the islands themselves was not vital, but the expenditure of time and effort and the resultant loss of lives, planes, and ships was a reverse from which the Japanese never recovered. There could only be a guess as to the number of casualties to the enemy in the various bombings, sea actions, and land battles. Postwar estimates placed the number at around 2,733 enemy dead,10 but this does not account for the many more who died in air attacks, barge sinkings, and ship sinkings. In any event, the units evacuated after the costly defense of the New Georgia Group were riddled shells of their former selves, and few ever appeared again as complete units in the Japanese order of battle.

More than three months of combat had been costly to the New Georgia Occupation Force, too. Casualties to the many units of the NGOF totaled 972 men killed and 3,873 wounded. In addition, 122 died of battle wounds later, and another 23 were declared missing in action. Marine Corps units, other than the 1st Marine Raider Regiment, lost 55 killed and 207 wounded.11

Conclusions

New Georgia lacked the drama of the early months of Guadalcanal and the awesome scope of later battles in the Central

Pacific. Instead, it was characterized by a considerable amount of fumbling, inconclusive combat; and the final triumph was marred by the fact that a number of command changes were required to insure the victory. There were few tactical or strategic successes and the personal hardships of a rigorous jungle campaign were only underscored by the planning failures. And too, the original optimistic timetable of Operation TOENAILS later became an embarrassing subject. For these reasons, a postwar resumé of the battle for the Central Solomons pales in comparison with accounts of later and greater Allied conquests.

The primary benefit of the occupation of the New Georgia Group was the advancement of Allied air power another 200 miles closer to Rabaul. The fields at Munda, Segi Point, and Barakoma provided ComAirSols planes with three additional bases from which to stage raids on the Japanese strongholds in the Northern Solomons and to intercept quickly any retaliatory raids aimed by the enemy at the main Allied dispositions on Guadalcanal and in the Russells. Behind this protective buffer, relatively free from enemy interference, the Allies were able to mass additional troops and matériel for future operations. This extended cover also gave Allied shipping near immunity from attack in southern waters. Although most fleet activities continued to be staged from Guadalcanal, the many small harbors and inlets in the New Georgia Group provided valuable anchorages and refueling points for smaller surface craft.

The capture of the Central Solomons also afforded the Allies the undisputed initiative to set the location and time for the next attack. The simple maneuver of bypassing Kolombangara’s defenses won for the Allied forces the advantage of selecting the next vulnerable point in the enemy’s supply, communication, and reinforcement lines. The Japanese, guarding an empire overextended through earlier easy conquests, could now only wait and guess where the next blow would fall. The New Georgia campaign presented the Japanese in his true light—an enemy of formidable fighting tenacity, but not one of overwhelming superiority. His skill at conducting night evacuation operations, demonstrated at Guadalcanal and confirmed at New Georgia, could not be denied, however. Both withdrawals had been made practically under the guns of the Allied fleet.

On the Allied side, the campaign furthered the complete integration of effort by all arms of service—air, sea, and ground. Seizure of the Central Solomons was a victory by combined forces—and none could say who played the dominant role. Each force depended upon the next, and all knew moments of tragedy and witnessed acts of heroism. The New Georgia battles marked a long step forward in the technique of employment of combined arms.

There were valuable lessons learned in the campaign, too—lessons which were put to use during the many months to follow. As a result of the New Georgia operation, future campaigns were based on a more realistic estimate of the amount of men and time required to wrest a heavily defended objective from a tenacious enemy. Another lesson well learned was that a command staff cannot divide itself to cover both the planning and administrative support for a campaign as well as the active

direction of a division in combat. After New Georgia, a top-level staff was superimposed over the combat echelons to plan and direct operations.

On a lower level, the tactics, armament, and equipment of individual units were found basically sound. As a result of campaign critiques, a number of worthwhile equipment improvements were fostered, particularly in communications where the biggest lack was a light and easily transported radio set. From the successful operation of Marine Corps light tanks over jungle terrain came a number of recommendations which improved tactics, communication, and fire coordination of the bigger and more potent machines, which were included in the task organization for future jungle operations. The battle against the enemy’s bunker-type defenses on New Georgia also pointed up the desirability of tank-mounted flame throwers. Experimental portable models used in the fight for Munda had proved invaluable in reducing enemy pillboxes. Increased dependency upon this newly developed weapon was one direct result of its limited use in the Central Solomons fighting.

Throughout the entire campaign, the improvement in amphibious landing techniques and practices was rapid and discernible. Despite seeming confusion, large numbers of troops and mountains of supplies were quickly deposited on island shores, and rapid buildup of men and material continued despite enemy interference. One contributing factor was the increased availability of the ships needed for such island-to-island operation—LCIs, LSTs, LSDs, and the workhorse LCMs. By the end of the Central Solomons campaign, two years of war production was beginning to make itself felt. Equipment and ships were arriving in bigger numbers. The efficiency of these ships and craft was, in part, a reflection on the soundness of Marine Corps amphibious doctrines—vindication for the early and continued insistence by the Marine Corps on their development and improvement.12

Blank page