Chapter 3: DEXTERITY Landings

Arawe-Z-Day to D-Day1

The focal point of DIRECTOR operations was a boot-shaped peninsula with Cape Merkus as its heel. Lying offshore from the boot’s sole are three islands, Ausak, Arawe, and Pilelo, which bound Arawe Harbor, an anchorage used by coastal shipping before the war. The beach chosen for the main Allied assault is about 1,000 yards due north of the cape on the harbor’s shore. Behind the beach, designated ORANGE Beach by planners, the ground slopes up sharply through a break in the cliffs that line the peninsula’s western and southern coasts. Most of the north shore of the peninsula and its bulbous toe are taken up by mangrove swamp, which occurs frequently in this part of New Britain; the high ground is occupied by the coconut trees of Amalut Plantation. (See Map 24.)

Between Cape Merkus and Sipul village, about 30 miles to the west, is a trackless region of swamp and jungle, a formidable barrier to movement. From the cape east, the coastal trail springs up again, forking at the Pulie River with one path leading cross island to Iboki and the other continuing along the shore until it disappears in dense rain forest. Four miles east of the neck of Arawe Peninsula (to give it the name used by Allied forces) is Lupin village, the site of a small prewar emergency landing ground. Unused by the Japanese, the airstrip was choked with kunai grass in December 1943.

The most practical way to travel along New Britain’s south coast is by boat, a fact that played the most important part in the selection of Arawe as an ALAMO Force target. Once General Cunningham’s landing force was ashore on Arawe Peninsula, it could put an end to enemy barge traffic and sever the supply and reinforcement route to Cape Gloucester. Since the Arawe-Iboki trail was known to be difficult and little-used—hardly more than a footpath—Allied planners thought it unlikely that the Japanese could move enough troops overland to threaten seriously Cunningham’s position. The proven hunting ability of Allied planes and torpedo boats made remote the prospect of any large-scale enemy movement by sea against Arawe.

In planning DIRECTOR operations, General Cunningham was hampered by a lack of intelligence of both terrain and enemy dispositions. To meet the situation as he understood it, he planned two subsidiary landings before making the assault

on Arawe Peninsula. The object of one landing was the seizure of a reported Japanese radio station and defensive position on Pilelo Island which commanded the best passages into Arawe Harbor. The second landing was designed to put a blocking force across the coastal trail just east of the foot of the peninsula. In both instances, General Cunningham strove for surprise, planning predawn assaults without air or ships’ gunfire support. The troops were to land from rubber boats instead of powered landing craft.

For the main landing, both air strikes and naval bombardment were scheduled to cover assault waves in LVTs and following waves in LCVPs and LCMs. The amphibian tractors were to be manned by Marines of the 1st Division and the landing craft by Army engineers of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. So little sure knowledge existed of reef conditions in and around Arawe Harbor that Admiral Barbey, who commanded the attack force, asked that ALAMO Force make LVTs available to carry the first waves ashore. The amphibian engineers and their boats were detailed to DIRECTOR Force to provide General Cunningham with a boat pool after the initial landings had been made.

On 30 November, General Krueger directed General Rupertus to assign 29 LVTs and their crews to DIRECTOR Force plus the Marines needed to operate 10 new armored Buffalo amtracs to be provided by the Army. The ALAMO Force commander pointed out that the tractors would be returned to division control before D-Day. The choice of the unit to fill the assignment logically fell on Company A, 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion. The company was part of the reserve combat team of the division and had had more experience handling the new Buffaloes than any other battalion unit.2

Plans called for the DIRECTOR assault troops to be carried to the objective in fast ships, vessels that could unload quickly and promptly leave the area. Later echelons carrying reinforcements and supplies would use LCTs shuttling from Finschhafen. Admiral Barbey was reluctant to risk any of his LSTs at Arawe with the BACKHANDER Operation so close at hand. He did approve, however, the use of the Carter Hall, a landing ship dock (LSD) which had just arrived in the Southwest Pacific, and of the Austrialian transport Westralia to move the men, amphibious craft, and supplies involved in the main landing. Two APDs were assigned to transport Troops A and B, 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, chosen to make the two rubber boat landings.

General Cunningham issued his formal field order for the seizure of positions in the Arawe area on 4 December; the assault troops had been alerted to their mission earlier as they assembled at Goodenough from Woodlark and Kiriwina. In addition to the task of securing Arawe Peninsula and the islands forming Arawe Harbor, the cavalrymen were to outpost the trail leading to the Pulie River and patrol vigorously to guard against enemy attacks. As soon as the task force position was consolidated, Cunningham was to send an amphibious patrol to the Itni River and Gilnit to check the possibility of overland contact with the Marines at Cape Gloucester.

The torpedo boat base called for in GHQ, Seventh Fleet, and ALAMO Force plans for Arawe remained a vague affair

at the operating level despite the definite language directing its establishment. In conferences with General Cunningham on 5 December, the fleet’s motor torpedo boat commander, Lieutenant Commander Morton C. Mumma, stated that he would assign two boats based at Dreger Harbor on New Guinea to patrol east of Arawe each night after the landing. The boats would report to the task force intelligence officer for briefing on arrival and be available for special missions on request, but they would return to Dreger with dawn. The only naval installations Mumma asked for at Arawe were emergency fueling facilities. In addition to the torpedo boats hovering near Arawe, he said another pair from Dreger would hunt barges nightly between Tauali and Sag-Sag and two others from Kiriwina would scout the vicinity of Gasmata. No boats would patrol the sector from Arawe west to the Itni because of the poorly charted reefs and shallows among the offshore islands.

The Carter Hall loaded Marine tractors and crewmen at Milne Bay on 5 December, as the Westralia picked up a company-size task group from the Boat Battalion, 592nd Boat and Shore Regiment. At Goodenough the two larger ships were joined by the APDs Sands and Humphreys, and the 112th’s assault troops came on board to take part in two practice landings, one a full-scale rehearsal of the operation. The results of the training showed that boat wave timing was off, that some junior leaders were not sure of themselves in the unfamiliar amphibious role, and that unit commanders did not always have control of their men—all faults that could be corrected with further rehearsal. Time was too short for more practice, however, as Z-Day (15 December) was approaching fast and the ships and men had to make last-minute preparations for the assault.

When the DIRECTOR operation was decided upon, the Japanese defenders of Arawe were calculated at 100-150 men with the only identified units a naval antiaircraft platoon and a small radio detachment. On 5 December, reconnaissance planes sighted 12-14 enemy barges at Kumbum Island near Arawe and four more along the peninsula’s shore. Although it was conceded that these craft might be taking part in a routine supply run, ALAMO intelligence officers felt it was “prudent to assume the enemy at Arawe now has at least 500 [men] and considerable reinforcement potential.”3 General Cunningham asked General Krueger for reinforcements to meet the added threat. On 10 December, a battalion of the 158th Infantry, a nondivisional regiment, was alerted as reserve for DIRECTOR.

Cunningham also asked that a 90-mm gun battery be assigned to his force to supplement the antiaircraft fire of the two batteries of automatic weapons he already had. Although the strength of the Japanese ground garrison at Arawe and its defensive potential were perplexing questions, there was little doubt in the minds of Allied commanders that the enemy air reaction to the landing would be swift and powerful. The few heavy antiaircraft guns available were already committed to other operations, however, and Cunningham’s force had to rely on machine guns and 20-mm and 40-mm cannon for aerial defense.

Loading for the Arawe landings got underway at Goodenough during the afternoon of 13 December. As Generals MacArthur

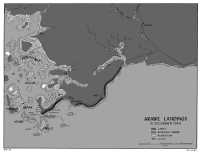

Map 24: Arawe Landing, 15 December 1943

and Krueger looked on, the Marine LVTs and two rocket-firing DUKWs, manned by Army engineers, drove into the water and churned through the stern gate and into the flooded well deck of the Carter Hall standing offshore. The assault troops who would ride the tractors, the 112th’s 2nd Squadron and supporting units, boarded the LSD while the 1st Squadron and regimental and task force headquarters rode the Westralia. Replacing the regular landing craft on the Australian ship’s davits were 16 LCVPs and 2 LCMs of the amphibian engineers. The troopers slated to make the rubber boat landings bedded down on the Sands and Humphreys, 150 men to each ship.

At midnight, the convoy sailed for Buna where General Cunningham boarded the destroyer Conyngham, Admiral Barbey’s command ship for the operation. After feinting a movement toward Finschhafen, the task force turned toward its target after dusk on 14 December and headed across the Solomon Sea. Guarding the west flank were cruisers and destroyers of Admiral Crutchley’s force and to the east was a cordon of Commander Mumma’s motor torpedo boats. Escorting the transports were nine destroyers, five of them designated a shore bombardment unit.

About 15 minutes before the convoy arrived in the transport area, a Japanese float plane scouted the ships, dropping a bomb near one of the destroyers. There was no return fire, in accordance with Barbey’s orders for dealing with night snoopers; gun flashes might reveal the presence of a ship and offer an aiming point to lurking attackers. But the Japanese pilot had reported the ships he had sighted as five destroyers and five transports, and Admiral Kusaka at Rabaul ordered planes of the Eleventh Air Fleet to attack. A Japanese submarine had also sighted the Allied ships late on the 14th, but its report did not reach enemy headquarters until after the landing.

The Carter Hall began taking on ballast before it arrived in the transport area about five miles from ORANGE Beach. By 0400 there was 4½ feet of water in the well deck and launching began. Within ten minutes all the vehicles had cleared the LSD. At about the same time, the Westralia lowered its landing craft and men began clambering down nets into the boats, while winches and rope slings handled the 40 tons of supplies and equipment figured as essential to sustain the assault troops in their first hours ashore. At 0500, the two large transports headed away in the darkness for New Guinea.

While the LVTs made ready for the run to ORANGE Beach and the landing craft circled waiting to follow the tractors’ lead, the surprise landings got underway. The APDs carrying Troops A and B hove to about 1,000 yards offshore, unloaded the cavalrymen and their boats, and started to withdraw immediately. As they had practiced, the soldiers paddled toward their target beaches in three waves of five boats each.

Troop A, which had the mission of cutting the coastal road near Umtingalu village, never reached its objective. At 0522, enemy automatic weapons cut loose from the featureless black outline that marked the shore, raking the oncoming boats. Within a few minutes, only three of the rubber craft were still afloat. From its position 3,000 yards out from Umtingalu, the supporting destroyer Shaw had difficulty seeing if the soldiers struggling in the water were in its line of fire. At 0542,

when the Shaw finally had a clear shot, two salvos of 5-inch high explosive shell were all that was needed to silence the enemy guns, The abortive landing attempt cost the 112th Cavalry 12 men killed, 17 wounded, and 4 missing in action.

When the Japanese fired on Troop A’s boats, Troop B abandoned its original landing plan for Pilelo and headed for the nearest beach on the island. Moving quickly inland after they landed, the cavalrymen isolated the small enemy garrison in caves near Winguru village and wiped them out after a fight at close quarters with bazookas, flame throwers, and grenades called into use. The troop lost one man and accounted for seven defenders in seizing its objective.

While the subsidiary landings were taking place, a column of Marine amphibian tractors started on the 5,000-yard run to ORANGE Beach. The armored Buffaloes in the lead, traveling at six knots, soon outdistanced the Alligators which were hard put to make 4½ knots. One of the control boats for the main landing, the SC-742, spotted the LVTs moving into Pilelo Passage well ahead of schedule and headed them off. The Buffaloes then circled off Cape Merkus waiting for the Alligators to catch up. Meanwhile, the slower tractors had gotten off course and had to be herded back into the prescribed boat lane. The upshot of the confusion was that the landing was delayed 40 minutes.

The pre-H-Hour destroyer bombardment was extended when it became clear that the LVTs were falling behind schedule, but the cease fire was sounded on board the ships at 0641 to conserve ammunition for antiaircraft defense. When the 5-inch shells stopped falling, the standby control boat, SC-981, began firing a spread of rockets on Cape Merkus to cover the movement of the landing vehicles through Pilelo Passage. At 0710, the DIRECTOR Force air support officer on the Conyngham called down a waiting squadron of B-25s to strafe and bomb the beach. Shortly thereafter, behind a barrage of rockets fired by the engineer DUKWs and SC-742, the assault troops of 2/112 landed.4

The bombardment silenced what little opposition there was at the beach, and the squadron moved inland cautiously but easily. Two of the Marine amtracs in the first wave were able to negotiate the steep bank behind ORANGE Beach and accompany the soldiers to their destination, the narrow neck of the peninsula. When enemy machine guns firing from the edges of the mangrove swamp pinned down the troopers, the armored Buffaloes crushed the defenders’ positions and silenced the guns. By mid-afternoon the 2nd Squadron was digging in on its objective. A pocket of Japanese riflemen left behind by the assault troops was eliminated by the 112th’s Headquarters Troop, and the peninsula was cleared of enemy forces by nightfall.

Survivors of the 120 Japanese soldiers and sailors who had defended Arawe Peninsula, Pilelo, and Umtingalu had withdrawn from contact with the landing force. The Army units, detachments from two temporary companies of the 51st Division, one of infantrymen, the other of artillerymen, rejoined their parent unit in

positions near the Pulie River at Didmop.5 The naval coastal antiaircraft platoon that had repulsed the landing attempt at Umtingalu, abandoned its guns and took off in precipitate retreat north up the overland trail. Coming south along the same trail, hurrying as best the jungle, rain, and frequent swollen streams would allow, was Major Shinjiro Komori’s 1st Battalion, 81st Infantry. Komori had arrived within earshot of the preliminary bombardment at Arawe, but was still four days’ forced march from the Pulie River, illustrating the difficulties of moving a large body of men through the center of New Britain.6

Intensive Japanese ground opposition to the Allied landing was yet to come, but, as expected, the aerial counterattack came on the heels of the landing. At 0855, after one flight of enemy planes had engaged the covering P-38 squadron and led it in a snarling dogfight away from the target, 30-40 naval fighters and bombers struck at the beachhead. From the Japanese point of view, the time of attack was auspicious. The only heavy antiaircraft guns left in Arawe waters were those on the Conyngham; all the other escort, control, and bombardment vessels had departed moments before. The first follow-up echelon of five LCTs, accompanied by seven engineer-manned LCMs, had just moved into Arawe Harbor to unload. The fire of machine guns and 20-mm cannon mounted on ships, LVTs, trucks, landing craft, and beach proved more than enough to beat off the attack. The total of serious damage was one LCVP blown up and a few men wounded.

Throughout the day the attacks continued, but Allied fighter squadrons were able to turn away most of the enemy planes. The vivid imaginations of the Japanese pilots supplied them with the damage that they were unable to inflict during their attacks, and Rabaul heard tales of many sunken transports and landing craft and damaged cruisers and destroyers.

Returning again and again during the next week, the Japanese planes, mostly carrier aircraft stationed at Rabaul, attempted to wipe out the Allied beachhead. Their effort was unsuccessful, although one LCT echelon arriving late on the 16th was under almost continuous air attack while it was at Arawe and had an escort coastal transport sunk, and an escort minesweeper and seven LCTs badly damaged. This was the high point of the enemy strikes; defending fighters and antiaircraft automatic weapons fire whittled down the attacker’s strength at a rate of three, four, or five planes a day, losses the Japanese could ill afford. As the fourth week of December began, large-scale air raids tapered off to night bombing runs and hit-and-run daylight missions by small numbers of enemy planes.

The frequent air attacks on Z-Day and the days immediately following severely disrupted the unloading process. An inexperienced shore party and a shorthanded naval beach party, worked to exhaustion, were unable to move supplies from ships to dumps smoothly; congestion on ORANGE Beach was constant. The beach itself proved capable of handling only two

Troopers of the 112th Cavalry wade ashore at Arawe as Marine LVTs carry in supplies on 15 December 1943. (SC 187063)

Moving off the ramp of a Coast Guard-manned landing craft, Marines move ashore on D-Day at Cape Gloucester. (USN 80-G-44371)

LCTs at a time, and other ships in each echelon had to stand by under threat of enemy air attack while waiting their turn to unload. Under the circumstances, LCT commanders were unwilling to remain at Arawe any longer than their movement orders stated, and, on occasion, cargo holds were only partially cleared before the ships headed back for Finschhafen. The problem grew steadily less acute as Japanese air raids dwindled in number and strength and the reserve supplies of the landing forces reached planned levels.

General Cunningham lost no time in making his position on Arawe Peninsula secure behind a well-dug-in defense line closing off the narrow neck. Engineer landing craft gave the general protection on his open sea flanks, and a series of combat outposts stretching up the coastal trail beyond Lupin airstrip promised adequate warning of any attempt to force his main defenses. The 112th was brought up to strength; Troop A was re-equipped by air drop on the 16th, and, two days later, APDs from Goodenough brought in the 3rd Squadron. The cavalry regiment acting as infantry and a reinforcing field artillery battalion seemed quite capable of handling any Japanese units that might come against them.

Pursuing his mission of finding out all that he could about Japanese forces in western New Britain before the BACKHANDER Force landed, Cunningham dispatched an amphibious patrol toward the Itni River on the 17th. Moving in two LCVPs, the cavalry scouts reached a point near Cape Peiho, 20 miles west of Arawe, by dawn on the 18th. There, appearing suddenly from amidst the offshore islets, seven enemy barges attacked the American craft and forced them into shore. Abandoning the boats, the scouting party struggled inland through a mangrove swamp, finally reaching a native village where they were warmly received.

An Australian with the scouts was able to get hold of a canoe and report back to Arawe by the 22nd to tell Cunningham that the waters between Cape Merkus and the Itni were alive with enemy barges. The natives confirmed this finding and also said that large concentrations of Japanese troops were located at the mouth of the Itni, Aisega, and Sag-Sag. Special efforts were made to insure that this intelligence reached General Rupertus, and Cunningham sent it out both by radio and an officer messenger who used a torpedo boat returning to Dreger Harbor.

The barges that the 112th’s scouts ran up against on the 18th were transporting enemy troops from Cape Bushing to the scene of action at Arawe. As soon as he heard of the Allied landing, General Sakai of the 17th Division had ordered General Matsuda to dispatch one of his battalions to Cape Merkus by sea. The unit Matsuda selected, the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry (less its 1st Company), landed at the village of Omoi on the night of 18 December, bivouacked, and started overland in the morning, heading for a junction with the Japanese at Didmop. Getting lost repeatedly in the trackless jungle, pausing whenever contact with the Americans seemed imminent, the battalion took eight days to march a straight-line distance of seven miles.

Major Komori, who was designated overall commander of enemy troops in the area, reached Didmop on the 19th, having gathered in the retreating sailors from Umtingalu on his way. For a few days he paused there, organizing his forces, and waiting for 1/141 to arrive. Finally deciding to delay no longer, Komori crossed

the Pulie with his main strength on Christmas Eve and arrived on the edge of the airstrip at dawn. The 112th outposts and patrols were forced back on Umtingalu and, with the troop stationed there, retired into the perimeter. A determined probing attack in company strength was made on the American main line of resistance on the night of the 25th; 12 infiltrators were killed within the cavalrymen’s positions before the Japanese were repulsed.

Komori’s attack emphasized one of the most successful aspects of the DIRECTOR operation. By the dawn of D-Day for the main DEXTERITY landings, two Japanese infantry battalions that might have fought at the main Allied objective were tied up defending a secondary target. What effect this shift of a thousand enemy troops, most of them combat veterans of the Philippines or China fighting, had on the Cape Gloucester operation is impossible to say with any certainty. It seems probable, however, that the casualties suffered by the 1st Marine Division would have mounted and the seizure of control of western New Britain would have been delayed had the enemy not changed his troop dispositions.

Prelanding Preparations7

While action at Arawe drew the attention of the Japanese, the BACKHANDER Force made its final preparations for the landings at Cape Gloucester. Rehearsals following the pattern of the YELLOW Beach landings, with all assault elements of Combat Team C embarked, took place at Cape Sudest on 20-21 December. The long months of training bore fruit, and the first waves moved from ship to shore without incident and were smoothly followed to the practice beaches by landing ships carrying supplies and reserve forces.

At Cape Gloucester, Admiral Barbey would again control elements of his amphibious force as Commander, Task Force 76 and fly his flag on the Conyngham as headquarters ship for the operation. From Seventh Fleet and Allied Naval Forces, now under Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid who had relieved Admiral Carpender on 26 November, would come the escort, covering, and bombardment vessels to support the landings. General Kenney’s Fifth Air Force would handle all air support missions except those that could be undertaken by the 1st Division’s own squadron of light planes.

The preliminary softening-up of the target was exclusively the province of Kenney’s planes and pilots. Air raids were so frequent through the late fall that Japanese soldiers’ diaries show little recognition of the fact that air strikes intensified after 18 December, for the condition of the men being attacked was so consistently miserable that the step-up escaped their notice. One ground crewman at the knocked-out airfields noted unhappily that “enemy airplanes flew over our area at will and it seemed as though they were carrying out bombing training.”8 Japanese interceptors and antiaircraft fire never seriously challenged the daily runs of strafers and bombers.

The weight of bombs dropped on targets in the Cape Gloucester vicinity between 1 December and D-Day exceeded 3,200 tons. Over 1,500 individual sorties were flown to deliver the explosives and to search out enemy targets with cannon and machine gun fire. Up until 19 December, the bombers concentrated their attacks on the airfields and their defenses, but then target priority shifted to objectives that might impede the landings and subsequent advance of the Marines. The attacks resulted in substantial destruction of prepared positions spotted by aerial reconnaissance and in the death of scores of Japanese soldiers. The judgment of air historians viewing the campaign was that mass bombing of the invasion areas at Cape Gloucester by the Fifth Air Force virtually eliminated the combat effectiveness of the Japanese defenses.9 Hidden by the jungle’s impenetrable cover from the probing aerial camera, most of the Matsuda Force survived the protracted aerial assault. The damage to defenders’ nerves and morale is apparent from contemporary records, however, and the widespread destruction of defensive positions undoubtedly eased the task of Marine attacking forces.

Behind the screen of air activity, the assembly of Barbey’s attack force proceeded without major hitch. A complicated schedule of loadings and sailings had to be met that would enable the various echelons to reach the target on time. On the afternoon of the 24th, two LSTs with headquarters and service detachments operating directly under General Rupertus’ command and reserve elements of Combat Team C embarked, left Cape Sudest for Cape Cretin near Finschhafen. At Cretin, the two ships were joined by five others loaded with troops of Combat Team B due to land on D-Day afternoon. At 0100 on Christmas morning, six LSTs of the third echelon sailed from Sudest with men of Combat Teams B and C and BACKHANDER Force supporting elements; at Cape Cretin, an LST carrying men and equipment of 3/1 joined the ships which were scheduled to nose into the YELLOW Beaches as soon as the infantry-carrying LCIs of the second echelon landed their cargos.

The main convoy of 9 APDs and 11 LCIs got underway from Cape Sudest at 0600, 25 December. Accompanying the ships and their six escort destroyers was the Conyngham with Barbey and Rupertus on board. Not long after the assault troops departed, transports carrying reserve Combat Team A arrived in Oro Bay from Milne, and the 5th Marines and its attached units landed at Cape Sudest to await the call for employment at Cape Gloucester. The 14 LSTs which were to land on D plus one (27 December), bringing in engineer, antiaircraft, and medical units and supplies for BACKHANDER Force, loaded out on Christmas and sailed during the night in trace of the D-Day convoys. Each LST bound for Cape Gloucester was fully loaded with trucks carrying bulk cargo; those ships landing on 26 December carried an average of 150 tons of supplies apiece, and the ones due in the next day 250 tons.

To minimize the risk of sailing poorly charted waters, the five LCIs carrying 2/1’s assault troops joined the main

convoy off Cape Cretin to make the passage through Vitiaz Strait. A small-boat task group, 12 Navy LCTs plus 2 LCVPs and 14 LCMs crewed by amphibian engineers, cut directly through Dampier Strait toward GREEN Beach. Accompanying the landing craft as escorts for the 85-mile voyage from Cape Cretin to Tauali were an engineer navigation boat, a naval patrol craft, and two SCs; four torpedo boats acted as a covering force to the east flank.

While the Eastern and Western Assault Groups of Barbey’s force approached their respective beaches, one possible objective of DEXTERITY operations was occupied by a reinforced boat company of the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. On 20 December, General Krueger approved a plan to set up a long-range radar on Long Island, about 80 miles west of Cape Gloucester, after Australian coastwatchers had reported the island free of enemy troops. Acting on an operation plan published only three days before embarkation, the engineer boat group began its shore-to-shore movement from Finschhafen on Christmas afternoon. Preceded by an advance party that landed from torpedo boats, the engineers and an Australian radar station went ashore on the island on the 26th. The lodgment on Long Island removed one target from the list of those that might be hit by 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, held back from employment at Cape Gloucester.10

STONEFACE Trail Block11

Although they occurred simultaneously as complementary operations within the overall BACKHANDER concept, the landings at GREEN and YELLOW Beaches are seen clearer when examined separately. The primary mission of Lieutenant Colonel Masters’ 2/1, reinforced, was a defensive one—to land, seize a trail block, and hold it against all comers. The first mission of the rest of General Rupertus’ force was offensive in nature—the capture of Cape Gloucester’s airfields. Masters’ command, code-named the STONEFACE Group, was scheduled to rejoin the rest of the 1st Division once the airfield objective was secured. (See Map 25.)

The LCIs with the STONEFACE Group embarked broke off from the convoy headed for the YELLOW Beaches at 0422 on D-Day morning. Accompanied by two escort and bombardment destroyers, the Reid and Smith, the troop-laden landing craft headed for a rendezvous point about four miles off the New Britain coast opposite Tauali village. Contact with the small-boat group that had made the voyage through Dampier Strait was made later than had been planned, but the transfer of assault troops to LCMs began

immediately, and the lost time was recovered.

Engineer coxswains, moving in successive groups of four, brought their boats alongside the three LCIs that carried the two assault companies, E and F. The Marines were over the side and headed for the line of departure within 10 minutes. Accompanying the four landing craft that formed the first wave were two other LCMs carrying rocket DUKWs of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade’s Support Battery; the rockets were intended for a beach barrage to silence opposition in the few minutes just before the landing.

As the column of LCMs moved lazily toward the line of departure, throttled down to keep from getting ahead of the landing schedule, the troops could hear the sound of naval gunfire at Cape Gloucester, seven miles away. Falling into formation behind the assault craft, two LCIs with most of Companies G and H on board made up the fourth wave. Bringing up the rear with a cargo of guns and vehicles and 575 tons of bulk stores were 12 LCTs organized in waves of three. The ships carried 20-days’ supplies and five units of fire for Masters’ 1,500-man force; the men themselves carried one unit of fire and a day’s rations.

From his headquarters on the Reid, the Commander, Western Assault Group, Commander Carroll D. Reynolds, ordered the prelanding supporting fires to begin on schedule. The two destroyers cruising 5,400 yards offshore fired 675 rounds of 5-inch at targets behind the beach and to its flanks as far as Dorf Point on the north and Sag-Sag to the south. After 20 minutes, the ships’ fire was lifted and Commander Reynolds radioed a waiting squadron of B-25s to attack; for insurance the Reid fired two star shells as a visual signal. As the medium bombers began making bombing and strafing runs along the long axis of the beach, the first wave of LCMs left the line of departure. The planes were scheduled to cease their bombardment when the landing craft were 500 yards from GREEN Beach, an event calculated to occur at 0743. At that moment, the engineer DUKWs began firing the first of 240 rockets they arched ashore.12 Two strafers made a last minute pass at beach targets after the DUKWs opened up but fortunately avoided the plunging rockets.13 At 0748, the first LCMs grounded on the beach and dropped their ramps.

The Marines of the assault companies moved quickly across the volcanic sand, mounted the slight bank bordering the beach, and then advanced cautiously into the secondary growth that covered the rising ground beyond. There had been no enemy response from the beach during the bombardment and there was none now that the Americans were ashore. Well-dug trenches and gun pits commanding the seaward approaches had been abandoned, and there was no sign of active Japanese opposition. The second and third waves of LCMs landed five minutes apart, adding their men to the swelling force ashore. At

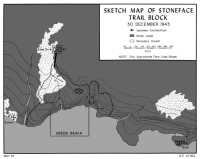

Map 25: Sketch Map of the STONEFACE Trail Block, 30 December 1943

0754, an amber star cluster was fired to signal a successful landing to the waiting ships.

The engineer LCMs retracted after delivering the assault troops and headed out to a rendezvous point a mile and a half from shore. When the beach was clear, the LCIs landed, dropped their twin bow ramps, and the Marines of Companies G and H filed down into shallow water. At 0830, the first of the LCTs hit, and the others followed in rapid succession as general unloading began.

The shore party was composed of a headquarters under 2/1’s operations officer, a labor platoon of 130 men drawn from all the major elements of the STONEFACE Group, and a beach party of amphibian engineers.14 Supplies were channelled through four predesignated unloading points into as many dumps set up in the area just off the beach. In each dump, similar amounts of rations, fuel, ammunition, and organizational equipment were further segregated to cut down possible losses to enemy air action. The absence of Japanese planes on D-Day, combined with unseasonably fine weather and a light surf, did much to ease the task of the inexperienced shore party. By 1715 the last LCT had been emptied and was assembled in the rendezvous area for the voyage back to New Guinea.

The convoy departed at 1900, leaving behind two LCVPs and four LCMs for offshore defense. The engineer boats anchored inside a reef outcrop about 200 yards from the beach with their stern guns pointing seaward. Lieutenant Colonel Masters gave the job of organizing the beach defenses to the Army engineer detachment commander, Major Rex K. Shaul, and assigned a platoon of LVTs and a platoon of the 1st Marines Weapons Company to his command. Inland, the STONEFACE commander disposed his three rifle companies along a 1,200-yard-long perimeter that ran along the ridges overlooking the beach. At its deepest point, a salient where a causeway led into the Marine lines, the perimeter was 500 yards from shore. The riflemen were carefully dug in by nightfall, and Company H’s heavy machine guns were emplaced amidst the foxholes where their fire could be most effective. The battalion weapons company’s 81-mm mortars were set up to fire in front of any part of the defensive position. In reserve behind each rifle company was a platoon of artillerymen. These provisional units had been formed on Masters’ order as soon as it became apparent that Battery H of 3/11 could not find a firing position that was not masked by precipitous ridges.

By nightfall on D-Day, the STONEFACE Group had established a tight perimeter defense encompassing all the objectives assigned it. The main coastal track lay within the Marine lines, denied to enemy use. Probing patrols into the jungle and along the coast did not discover any Japanese troops until dusk, when there was a brief brush with a small enemy group near the village of Sumeru, just north of the beachhead. The Japanese faded away into the jungle when the Marine patrol opened fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Masters was unable to contact General Rupertus directly to report his situation. Mt. Talawe, looming between the two Marine beachheads, proved an impenetrable barrier to the battalion’s radios. Since the set of the amphibian engineers was intermittently able to reach ALAMO Force, word of the STONEFACE Group’s dispositions eventually reached the division CP on the morning of the 27th. Except for the fact that his force was located in a radio “dead spot” for overland communication,15 Masters was in excellent shape to accomplish his mission.

Ashore at the YELLOW Beaches16

On Christmas morning, a Japanese coastwatcher hiding out in the hills above Cape Ward Hunt on New Guinea spotted the Eastern Assault Group en route to its target. This enemy observer’s report of the ships’ passage, sightings by a Japanese submarine scouting the area, or, perhaps, the last frantic message from a reconnaissance plane that was shot down shortly after noon while it was skirting the convoy, may one or all have been responsible for Rabaul’s deduction that the assault group was headed for Cape Merkus. On the strength of this faulty judgment, the Eleventh Air Fleet and Fourth Air Army planned a hot reception for the ships at Arawe on the 26th.17

The path of the invasion convoy during daylight hours had been plotted to mislead the Japanese. Once night fell, the moonless dark that ALAMO planners had waited for, the ships shifted their course to a more direct route through Vitiaz Strait. The destroyers, transports, landing ships, and escorts steamed along at 12 knots while Admiral Crutchley’s cruiser force ranged ahead to take position in gunfire support areas lying off the Cape Gloucester airfields.

Maintaining the convoy’s pace proved to be too much of a strain on the engines of a harbor mine sweeper (YMS) which was scheduled to clear the waters off the YELLOW Beaches. The ship broke down finally and fell out at 2120, returning to Cape Cretin; earlier, another YMS had been taken in tow by an APD to keep it in the convoy. As Admiral Barbey’s ships began to move into the transport area, the two YMSs that had completed the voyage, two destroyers, and two SCs operated together to locate, clear, and buoy the channel leading to the YELLOW Beaches. (See Map IV, Map Section.)

The destroyers, taking a radar fix on the wreck of a Japanese destroyer that was hung up on the reef 7,000 yards offshore, found the entrance to the channel in the darkness. Using their sound gear to locate shoals along the passage, the destroyers gave their bearing and distance to the YMSs which would then “strike off for the shoal as a dog after a bone.”18 The minesweepers

and a destroyer’s whaleboat buoyed the three principal reef obstacles on schedule, and one of the YMSs swept the channel which proved to be free of mines. Immediately, the destroyers moved inside the outlying reefs to deliver close-in fire on the eastern flank of YELLOW 2. The SCs, which had also controlled the Arawe landing, proceeded to line of departure and standby stations to handle the waves of landing craft.

Throughout the clearance and marking of the channel, a mounting drumfire of naval bombardment marked the approach of H-Hour (0745). At 0600, the two Australian heavy cruisers of Task Force 74 opened up on targets in the vicinity of the airfields with the first of 730 rounds of 8-inch high explosive fired during the next 90 minutes. The 6-inch guns on the American light cruisers sounded next, firing 2,000 rounds between 0625 and 0727 at Target Hill and the YELLOW Beach area. Escort destroyers with the cruiser force and those that had worked with the harbor control unit exploded 875 5-inch shells ashore while the larger ships were firing and, later, in the few moments immediately preceding H-Hour. The ground just inland from the beaches and the hills to the southeast drew most of the destroyer fire. Targets of opportunity were few since no evidence of enemy movement or opposition developed ashore during the Allied bombardment.

From 0700 to 0720, while naval gunfire was concentrated on the beaches and airfields, five squadrons of B-24s dropped 500-pound bombs on the Target Hill area. Then, on schedule, at the call of a command plane aloft, naval gunfire on the beaches lifted and a squadron of B-25s streaked in over Target Hill to let go eight tons of white phosphorous bombs on its naked crest. Smoke soon obscured the vision of any enemy who might still have been using the hill as an observation post, and three medium bomber squadrons began working over the beaches.

As General Rupertus had feared when he argued against its use,19 smoke from Target Hill drifted down across the landing beaches pushed on by a gentle southeast breeze. By H-Hour the shoreline had disappeared in a heavy haze, and within another half hour the approach lanes were obscured as far as the line of departure, 3,000 yards out. Coxswains of the leading boat waves handled their craft boldly, however, and the smoke posed no severe problem of control or orientation.

The first four waves of LCVPs assembled in succession as the APDs carrying the assault troops sailed into the transport area, two and three ships at a time. Once the Marines of 1/7 and 3/7 were over the side, the APDs left for positions outside the reef to await the return of their boats. The 12 landing craft in the first wave, 6 for each beach, moved from column into line at the control boat centered on the line of departure. At about 0730, the SC-981 dropped the wave number flag it was flying, and the assault platoons headed for the smoke-shrouded beaches. Following waves were dispatched at five-minute intervals.

Taking station on the flanks of the first wave as it moved shoreward, two rocket LCIs made ready to fire a stunning barrage onto possible beach defenses to cover

Shore party marines struggle to build a sandbag ramp for LSTs in the surf at Cape Gloucester’s YELLOW Beaches. (USMC 68999)

105-mm howitzers of 4/11, set up in a kunai grass clearing, fire in support of Marines attacking toward Cape Gloucester’s airfields. (USMC 69011)

the interval between the last B-25 strafing run and the wave’s landing. When the boats were 500 yards out, the LCI rockets began dropping ashore and worked inland as the Marines approached the beach. At 0746 on YELLOW 1 and 0748 on YELLOW 2, the LCVPs grounded and dropped their ramps.

Charging ashore to the sound of their own shouts, the Marines splashed through knee-deep water onto narrow strands of black sand. There was no enemy response—no sign of human opposition—just a dense wall of jungle vegetation. On many stretches of YELLOW 1, the overhanging brush and vines touched the water; there was only a hint of beach. Led by scouts forced to travel machete in one hand, rifle in the other, the assault platoons hacked their way through the tangled mass, won through to the coastal trail, and crossed it into the jungle again. Once they had passed over the thin strip of raised ground back of the beaches, the men encountered the area marked “damp flat” on their maps. It was, as one disgusted Marine remarked, “damp up to your neck.”20

Under the swamp’s waters was a profusion of shell and bomb craters and potholes, places where a misstep could end in painful injury. An extra obstacle to the terrain’s natural difficulty were the hundreds of trees knocked down by the air and naval gunfire bombardment. The roots of many of the trees that remained standing were so weakened that it took only a slight jar to send them crashing. The swamp took its own toll of casualties, dead and injured, before the campaign ended.

Enemy firing first broke out to the west of YELLOW 1 where Company I of 3/7 had landed. Confused by the smoke, the LCVPs carrying the company’s assault platoons reached shore about 300 yards northwest of the beach’s boundary. Once the Marines had chopped through the jungle to reach the coastal trail, they came under long-range machine gun fire issuing from a series of bunkers lying hidden in the brush. The company deployed to take on the Japanese and gauge the extent of the enemy position.

The task of reducing the bunkers fell to 3/1 which was charged with leading the advance up the trail toward the airfields. The men of the 1st Marines’ battalion began landing from LCIs on YELLOW 1 at 0815, and the last elements were ashore and forming for the advance west by 0847. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Hankins started his men forward on a two-company front 500 yards wide, passing through 3/7, which temporarily held up its advance to the beachhead line. The swamp on his left flank soon forced Hankins to narrow his assault formation to a column of companies. At 1010, the Japanese opened up on Company K in the lead, soon after it had passed through the firing line set up by Company I of 3/7. The ensuing fight was the bitterest struggle on D-Day.

For a short while the course of the battle seemed to turn against the Marines—both the commander and executive officer of Company K were killed; bazooka rockets failed to detonate in the soft sand covering the enemy bunkers; flame throwers malfunctioned when they were brought into play; and antitank and canister shot from 37-mm cannon proved ineffective against the log-reinforced dugouts. The

break of fortune came when an LVT which had come up from the beachhead with ammunition tried to crash into the enemy position. The vehicle got hung up between two trees, and the well-protected Japanese broke from cover to attack the cripple, killing its two machine gunners. The driver managed to work the tractor loose and caved in the nearest bunker by running over it. The Marine riflemen took advantage of the LVT’s success and cracked the defensive system, killing or scattering the defenders of the four bunkers that had held up the advance.

Medium tanks had been requested for support as soon as it became apparent that 3/1 was up against a fortified position. A platoon of Shermans arrived shortly after Company K won its fight21 and led Company I forward through the ruined emplacements. Only a few snipers were encountered on the way to the 1-1 Line, the first objective on the coastal route to the airfields. Lieutenant Colonel Hankins reported 1-1 secure at 1325 and received orders to hold up there and dig in for the night. The brief but bitter fight for the bunkers cost 3/1 seven Marines killed and seven wounded. The bodies of 25 Japanese lay in and around their shattered defenses.

On the opposite flank of the beachhead, the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel John E. Weber), making Combat Team C’s main effort, had driven to Target Hill by noon and seized the left sector of the beachhead line. A platoon of Company A flushed and finished off the only opposition, the few dazed defenders of two gun positions on Silimati Point. Company B’s men, picking their way through the swamp in an area where two feet of mud underlay a like cover of water,22 took the day’s prime objective and found ample evidence that the Japanese had used Target Hill as an observation post.

The task of seizing the center of the beachhead was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Odell M. Conoley’s 2nd Battalion of the 7th. The unit was ashore and assembled by 0845, though the men on two LCIs that had eased their way into the beach had to wade through neck-deep surf. The sodden condition of the unfortunate Marines that had to breast the water to shore was soon matched by that of many others when 2/7 had its bout with the swamp. The battalion passed through a Japanese supply depot south of the coastal trail and ran into scattered opposition as it advanced into the jungle again. A scout in Company G was the first Marine killed and other casualties occurred as the leading companies struggled through the 900-yard width of the swamp to rising ground. By late afternoon, Conoley could report his battalion had reached dry land and was digging in. LVTs brought up ammunition, and 2/7 got set for counterattacks that irregular but hot enemy fire promised. Both flanks hung open until they were dropped back to the swamp’s edge.

The 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, led by Lieutenant Colonel William R. Williams, reached its assigned portion of the beachhead line after threading its way through the swamp barrier and crossing the only

large patch of kunai grass within the planned perimeter. Williams’ unit met no serious opposition during its advance, but late in the afternoon, when division ordered a shift to the west to link up with Combat Team B, a small group of enemy troops attempted to infiltrate through the gap that opened. The battalion was recalled to its original positions and dug in along the edge of the kunai grass for night defense.

When the second echelon of LSTs arrived and began unloading on D-Day afternoon, the remaining rifle battalion assigned to the BACKHANDER assault force landed and moved into position. The 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Walker A. Reaves) filed up the coastal trail past long lines of trucks waiting to move into the limited dump areas available. The unit’s own equipment and combat team supplies, mobile loaded in organic vehicles, followed when traffic would allow. Accompanying the infantrymen when they moved out of the beachhead to the 1-1 Line was the 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines (Major Noah P. Wood, Jr.), Combat Team B’s direct support pack howitzer battalion. The artillery batteries set up along the coastal trail within the perimeter established by 1/1 and 3/1. General Shepherd and Colonel Pollock visited Colonel Whaling’s CP at 1800 to pass on a division attack order for 0700, 27 December.

In contrast to the relative ease with which 2/11 reached its firing site, the two artillery battalions assigned to Combat Team C spent most of the day getting their guns into effective supporting positions. The lighter 75-mm howitzers of 1/11 had been loaded in LVTs in anticipation of the difficulties that would be met in the “damp flat.” This forethought paid dividends, since the amphibian tractors were able to move the guns directly from the LVTs to the battery locations which had been picked from maps and aerial photographs. The battalion’s preselected positions proved to be in the midst of the swamp, but Lieutenant Colonel Lewis J. Fields directed his commanders to set up their guns around the edges wherever a rise of ground gave firm footing. The LVTs knocked down trees to clear fields of fire, hauled loads of ammunition and equipment to the guns, and helped the tractor prime movers and trucks get across the swamp. Fields’ howitzers began registering at 1400,23 five and a half hours after they landed, and 1/11 was ready to fire in direct support of the 7th Marines all along the perimeter by nightfall.

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas B. Hughes’ 4th Battalion’s 105-mm howitzers needed every bit of assistance they could get to reach the kunai grass patch. LVTs broke a path through the swamp’s tangle of trees and undergrowth for the tractors and guns and provided extra pulling power where it was needed. And the need was constant. The progress of each howitzer through the swamp was a major operation which often found the men of the firing section chest deep in water hauling on drag ropes or pushing mired wheels while tractor winches and LVTs in tandem applied full power to keep the guns moving. All supplies and ammunition had to be carried in amphibian tractors, since no truck could negotiate the tortuous trail through the swamp. Despite the incredible difficulties, the first battery was in position and ready to fire at 1330, the second was registered by 1700,

and the third was pulling into the clearing as darkness fell.24

While the division assault troops were consolidating their hold on the beachhead, Lieutenant Colonel Ballance’s shore party was coping with the confusion of problems arising from the unloading of equipment, vehicles, and bulk stores brought in by the LSTs. The carefully-thought-out plan of overlapping dumps to be used by each landing ship was adapted to meet the situation posed by the swamp. All supplies had to be crowded on the narrow strip of dry land between beach and swamp, nowhere more than a couple of hundred yards wide. The coastal track was crammed with vehicles almost as soon as the first seven LSTs beached at 0840, and the jam never eased during the rest of the day.

On the beaches themselves, the shore party constructed sandbag causeways out to the LSTs that grounded and dropped their ramps in the water. Although VII Amphibious Force reported that D-Day’s “four foot surf around the ramps was of no consequence,” and that “thick growth and soft ground behind the beach was the retarding factor”25 in unloading operations, the men that wrestled sandbags in the water had a different opinion. Actually, the slowness of unloading was due to a combination of factors, not the least of which was the reluctance of the drivers of the mobile loaded trucks borrowed from ALAMO Force to chance being left behind on New Britain when the LSTs pulled out. Numerous trucks were abandoned and “stranded on the beach exits for quite some time”26 before Marines could move them to the dumps and get them unloaded.

The first echelon of LSTs retracted at 1330 with about 100 tons of bulk stores still on board in order that the D-Day landing schedule could be kept. As the seven ships in the second echelon beached and started unloading about an hour later, the long-expected Japanese aerial counterattack materialized. As the enemy planes dove through the gunfire of American fighters covering the beachhead, a squadron of B-25s bound for a routine bombing and strafing mission in the Borgen Bay area flew low over the LSTs. In a tragic mistake of identity, the ships’ gunners shot down two of the American planes and badly damaged two others. Compounding the original error, the B-25s that had weathered the LSTs’ fire bombed and strafed 1/11’s position on Silimati Point, killing one officer and wounding 14 enlisted men.

The enemy planes that hit the beachhead were only a small portion of an attack group of 88 naval fighters and dive bombers dispatched from Rabaul after they had returned from a morning’s fruitless raid on Arawe. Most of the Japanese pilots concentrated on the ships offshore and the damage they did was severe, although they suffered heavily in the process. The radar on the fighter director ship, the destroyer Shaw, had picked up the enemy when they were about 60 miles away and vectored two P-38 squadrons to intercept, while the escort vessels cleared the reef-restricted waters off the coast and steamed out to sea to get maneuver room. The interceptors missed contact but wheeled quickly to get on the enemy tails, and a vicious dog fight took place all over the sky as the American and

Japanese fighters tangled. Some of the dive bombers evaded the defending fighters to strike at the destroyers. The Shaw was badly crippled by near misses, two other ships were damaged, and the Brownson, which took two bombs directly back of its stack, sank within a few minutes. One hundred and eight officers and men went down with their ship, but the rest of the crew was rescued while the enemy planes were being driven off.

The toll of lost planes, pilots, and crews was still enough so that the Japanese never again attempted a daylight raid on Cape Gloucester in comparable strength. Just what the exact enemy loss was in the several attacks mounted by Army and Navy pilots on 26 December cannot be discovered. The total was probably more than the 18 planes recalled by the Japanese in postwar years,27 and a good deal less than the 57 planes claimed by American pilots while the heat of battle was on them.28 From 27 December on, Allied air strikes mounted from South Pacific bases kept Rabaul’s air garrison too busy flying defensive missions to devote much effort to Cape Gloucester.

By nightfall on D-Day, it was evident that the BACKHANDER Forces’ main beachhead on New Britain was secure. General Rupertus had left the Conyngham at 0800 and was on the beach before the advance echelon of his command post set up at 1030. The CP location, like so many positions chosen prior to the landing, proved to be too “damp” for effectiveness and was moved to dry land by noon. Troops landed according to plan, and 11,000 men were ashore when the second LST echelon retracted at 1800. Although 200 tons of bulk stores returned in these ships to New Guinea, they were sent back on turn-around voyages and the temporary loss was not a vital one. All guns and vehicles on the LSTs had landed. During the day’s sporadic fighting, the 1st Division had lost 21 killed and 23 wounded and counted in return 50 enemy dead and a bag of 2 prisoners.

At 1700, after it became evident that the Japanese were warming up to something more effective than harassing fire, particularly on the front of 2/7, Rupertus dispatched a request to ALAMO Force that Combat Team A be sent forward immediately to Cape Gloucester. While it seemed obvious that the troops already ashore could hold the YELLOW Beaches perimeter, the task was going to require all of Colonel Frisbie’s combat team. The planned employment of 3/7 as Combat Team B reserve could not be made, and Rupertus considered that the 5th Marines was needed to add strength to the airfield drive and to give him a reserve to meet any contingency.

All along the front in both perimeters, the Marines were busy tying in their positions as darkness fell, cutting fire lanes through jungle growth, and laying out trip wires to warn of infiltrators. For a good part of the men in the foxholes and machine gun emplacements, the situation was familiar: Guadalcanal all over again, Americans waiting in the jungles for a Japanese night attack. The thick overhead cover was dripping as the result of an afternoon rain that drenched the beachhead and all that were in it. The dank swamp forest stank, the night air was humid and thick, and the ever present jungle noises mingled with the actual and the imagined sounds of enemy troops readying an assault.