Chapter 3: Consolidating a Foothold

First Night at Agat1

The day had not gone well for the enemy’s 38th Regiment. Most of the men in the two 1st Battalion companies that had tried to hold the Agat beach defenses were dead by noon, including the commander of 1/38 who was killed as he led his headquarters and reserve elements in a “Banzai” counterattack against 4th Marines assault troops. The guns of the two artillery batteries that had fired in direct support of the beach defenses had been demolished by naval gunfire and air bombardment. Only a few members of the gun crews survived the destructive fire.

On the northern flank of the beachhead, the 22nd Marines had wiped out forward elements of 2/38 that tried to hold Agat. Most of the units of the enemy battalion were still intact, however, when darkness fell. Since the battalion commander had lost contact with regimental headquarters at about 1200, he had little knowledge of how the battle was going except on his own front, where it was going badly.

To the south of the Marine positions, the 8th Company of 3/38 was committed early on W-Day to reinforce the 1st Battalion platoons that had tried to hold Hill 40 and Bangi Point. The remainder of the 3rd Battalion, spread out through a defensive sector stretching to Facpi Point and beyond, was assembled by its commander by midafternoon, ready to move against the American beachhead. Marine intelligence officers considered the situation was ripe for a Japanese counterattack—and a counterattack was coming.2

From his command post on the slopes of Mt. Alifan, Colonel Tsunetaro Suenaga had seen the Americans overwhelm his defenses along the island shore. The resulting swift inland advance of Marine infantry and tanks threatened to make a mockery of the attempt by the 38th Regiment to hold the Agat sector unless the Japanese commander regained the initiative. Suenaga, who felt that his only chance to retrieve the situation lay in an all-out counterattack, gave orders for his

battalions to prepare for a three-pronged assault against the center and both flanks of the 1st Brigade position. By word of mouth and runner, all 1st Battalion survivors of the day’s battles were ordered to assemble at regimental headquarters.

At about 1730, Colonel Suenaga telephoned the 29th Division CP to inform General Takashina of his counterattack plans. At first, the general refused permission for the attack because the regiment had been “badly mauled during the day,”3 but finally, in view of the overall battle situation, he reluctantly authorized the assault.4 Takashina cautioned the colonel, however, to make plans for reassembling his men following the counterattack in order to continue the defense of Mt. Alifan. Doubt about the outcome of the attack was obviously shared by Suenaga, who, soon after this call, burned the colors of the 38th Regiment to prevent their capture.

The pending Japanese counterattack was fully anticipated by General Shepherd’s veteran troops. All along the Marine front lines as darkness deepened, company and battalion mortars registered their fire along possible avenues of approach. Taking position offshore, gunfire support ships checked into the control nets shared with the liaison officers and spotter teams. The six pack howitzer batteries of the Brigade Artillery Group made preparations for their part in the night’s proceedings.

The early hours of the evening were tense but quiet. Occasional brief flare-ups of firing marked the discovery of enemy infiltrators. Finally, just before midnight, a flurry of mortar shells burst on the positions of Company K of 3/4, on the right flank of the brigade line. Japanese infantrymen, bathed in the eerie light of illumination flares, surged forward toward the dug-in Marines. The fighting was close and bitter, so close that six Marines were bayoneted in their foxholes before combined defensive fires drove the enemy back.5

This counterattack was but the first of many that hit all along the beachhead defenses during the rest of the night. Illumination was constant over the battlefield once the Japanese had committed themselves; naval gunfire liaison officers kept a parade of 5-inch star shells exploding overhead. Where the light shed by the naval flares seemed dim to frontline commanders, 60-mm mortars were called on to throw up additional illumination shells. The attacking enemy troops were nakedly exposed to Marine rifles and machine

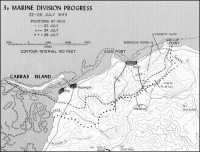

Map 26: Southern Beachhead, 22-24 July 1944

guns and the lethal bombardment directed by forward observers for heavier supporting weapons. The carnage was great, but the men of the 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry kept trying to break through the American lines.6

Hill 40, 300 yards inland from Bangi Point, became the focal point of the 3/38 attack. The platoon of Company K holding the small rise was hard pressed and driven out of its positions twice, but rallied each time, counterattacked, and recovered its ground. Similar dogged efforts by Major Hoyler’s men kept the remainder of the 3/4 defenses intact, but when small arms ammunition ran low in the forward holes, the Marines reserved their fire for sure targets. The defensive fusillade, however, had accomplished its purpose; there were few Japanese left alive in front of Company K.

In the confusion of the fighting, small groups of the enemy, armed with demolition charges, made their way through the lines headed for the landing beaches. Some of these Japanese stumbled into the night defensive perimeters of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 305th Infantry; those that did were killed by the alert soldiers. Other Japanese made life miserable for the Marine artillerymen that were firing in support of the frontline troops. As one battery executive officer recalled:

By 0130, we were up to our necks in fire missions and infiltrating Japanese. Every so often, I had to call a section out for a short time so it could take care of the intruders with carbines and then I would send it back into action again.7

Explosive-laden parties of enemy soldiers got as far as the beach road, where they disabled two weapons carriers and three LVTs before they were gunned down. A platoon from the Ammunition Company, 5th Field Depot intercepted and killed 14 Japanese headed for the brigade ammunition dump.8 The 4th Marines Tank Company also had a rough night with infiltrators; 23 were killed in and around the service park.

Not all the Japanese that found their way into the rear areas of the brigade came through the thinly spread positions on the south flank of the beachhead. A few filtered through the 22nd Marines lines on the north, and others were offshoots of the force that attacked the 4th Marines units dug in on the lower slopes of Mt. Alifan. Here, where Colonel Suenaga was in the forefront of the assault troops, the Japanese made an inspired effort to break through to the beach, but in vain. In the course of the fighting the enemy commander himself was killed.

Japanese probing attacks began hitting all along the lines of 1/4 shortly before midnight, but the fire fights that developed were just preliminaries to

the main event. At about 0230, the rumble of tanks was heard above the din of battle by the Marines guarding Harmon Road. A hurry-up call for Marine tanks was sent to the 2/4 CP, where a platoon of the regimental tank company was on alert for just such an eventuality. First two and later the remaining three mediums of the platoon moved up to the area where Company B held blocking positions on the road. At 0300, Marine infantry and tank machine guns opened up on a column of Japanese light tanks as they approached the American lines. When tracers located the targets, tank gunners and a bazooka team close by the roadside opened fire at pointblank range. The first two enemy tanks were hit by rockets before the bazooka gunner was cut down by the return fire. The 75s of the Shermans also hit both lead tanks and two others besides. Helped by the light of burning tanks and the flares which sputtered overhead, the men of Company B beat back the Japanese infantry that had accompanied the abortive tank thrust.

To the right of the Harmon Road positions, Company A had a hard night-long struggle to hold its ground against the Japanese troops that repeatedly charged down the heavily wooded slopes of the mountain. But the Marines did hold, despite casualties that reduced one rifle platoon to a strength of four able-bodied men.9 By dawn, the worst part of the night’s battle to hold the center of the brigade line was over. As the sun came up, a Japanese tank was spotted well up in the mountain pass near the Maanot Reservoir. A Marine Sherman, one of those that had helped repulse the night’s attacks, fired four armor-piercing shells at a range later figured at 1,840 yards, and scored two hits, setting the tank afire.

Marine tanks, sharpshooting or otherwise, were not needed on the northern flank of the perimeter during the night’s fighting. Although there was a constant drumfire from enemy infiltration attempts all along the 22nd Marines lines, there was no all-out effort by the Japanese, since the commanding officer of 2/38 had received no orders to join in the counterattack of his regiment. Only his 6th Company, which was positioned near Maanot Pass, got caught up in the 38th Infantry attempt to break through the Marine lines. As a consequence, Company G on the right flank of the lines of 2/22 had a busy night of fighting, killing 30 enemy troops between 0100 and 0500. Bands of infiltrators that did get into the rear areas harassed the 22nd Marines CP until daylight, when Colonel Schneider’s headquarters troops mopped up the area.

Dawn brought a general cleanup of the surviving Japanese infiltrators throughout the brigade perimeter. Local attacks supported by tanks quickly restored the lines wherever they had contracted for better night defense during the height of the fighting. The brigade lost at least 50 men killed and twice that number wounded during the

counterattack,10 but counted over 600 enemy dead within, on, and in front of the perimeter.

After one day and a night of battle, the 38th Regiment ceased to exist as an effective fighting force. Only its 2nd Battalion was still intact, and it now started to pull back from contact with the 22nd Marines and retire toward Orote Peninsula. The dazed and scattered survivors of the counterattack, about 300 men in all, gradually assembled in the woods northeast of Mt. Alifan. There, the senior regimental officer still alive, the artillery battalion commander, contacted the 29th Division headquarters. He soon received orders to march his group north to Ordot, the assembly point for Japanese reserves in the bitter struggle for control of the high ground that commanded the Asan-Adelup beaches.

Bundschu Ridge and Cabras Island11

There were few members of the enemy’s 320th Independent Infantry Battalion left alive by nightfall on W-Day. Two of its companies, once concentrated in the Chonito Cliff area and the other at Asan Point, had defended the heights that rimmed the 3rd Marine Division beaches. The third rifle company, originally located along the shore east of Adelup Point, had been committed early in the day’s fighting to contain the attacks of the 3rd Marines. The commander of the 48th IMB, General Shigematsu, had also committed his brigade reserve, the 319th Battalion, to the battle for control of the high ground on the left flank of the American beachhead.

According to plan, as soon as the landing area was certain, General Shigematsu assumed command of most of the 29th Division reserve strength and began its deployment to the rugged hills above the Asan beaches. Elements of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Infantry plugged holes in the defenses in the center of the Japanese position, where they tangled with the 21st Marines. The 9th Company, 38th Infantry reinforced the troops holding the well-concealed emplacements and trenches atop Bundschu Ridge. From positions near Ordot, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 10th Independent Mixed Regiment were ordered to move out to reinforce 2/18, hard pressed by Colonel Butler’s Marines who had seized a lodgment on the cliffs behind Green Beach.

American carrier planes spotted the movement of the 10th IMR battalions as soon as they began to move out—about 1100. Although the regiment was only 2½ miles from its initial objective, it took most of the long, hot afternoon to reach it. Towards dusk, the leading elements of the 10th began filing their way up the steep, brush-filled valley between Fonte Plateau and Mt. Macajna. (See Map 27.)

Just about the time that the 10th IMR

was reaching the relatively open ground along the Mt. Tenjo Road, the 321st and 322nd Independent Infantry Battalions began moving toward the fighting, too. Leaving one company and a rapid fire gun unit to man its defenses at Agana Bay, the 321st started south at 2000.12 An hour earlier, the 322nd, which had 2-3 miles farther to travel, had left Tumon Bay on a forced march for the battlefield.

Using the Fonte River valley as their gateway to the heights, Japanese reserves continued to arrive at their assembly area on Fonte Plateau throughout the night. General Shigematsu, operating from his battle command post in a quarry not far from the road, dispatched reinforcements into the fight as they became available. Repeatedly, as the night wore on, small groups of enemy infantrymen charged out of the brush, hurling grenades and firing their rifles as they attempted to drive the defending Marines off the high ground. Japanese mortar fire tore at the thin American lines throughout these attacks, and casualties were heavy, but the men of the 21st Marines held. The brunt of the assaults fell on 2/21 along its right flank, but Lieutenant Colonel Smoak drew back his right company to the edge of the cliff where it held and beat back all comers.

Helped immensely by the constant flare light overhead, American mortar, artillery, and naval gunfire observers rained a holocaust on the determined attackers. According to Japanese estimates, during this one night’s fighting, 2/18 had two-thirds of its men killed or wounded, 2/10 suffered comparably heavy losses, and 3/10 lost “approximately 200 men.”13 The remaining attackers drew off at dawn to join forces with the troops that General Shigematsu had called up from Agana and Tumon Bay.

Neither of the battalions of the 48th IMB was able to make its way up through the Fonte valley in time to have a significant effect on the night’s fighting. The 321st in fact was “thrown into utter disorder”14 by Marine artillery fire as the battalion struggled upward in the darkness, and was scattered again by strafing carrier aircraft after first light. The 322nd Battalion, which followed, could do little more than move into holding positions in the Fonte area, where it arrived near dawn, and wait for a more auspicious occasion to launch a counterattack. The focus of Japanese efforts to dislodge the Marines now shifted from the center to the left of the 3rd Division lines.

The Marines of 2/3 and 3/3 that had seized Adelup Point and Chonito Cliff had a precarious hold on their prize terrain. Early in the morning, the men of the 319th and 320th Independent Infantry Battalions, who had lost the positions on the 21st, tried to win them back by an all-out counterattack. The situation was serious enough for Colonel Hall to commit all his strength and, at 0605, to request reinforcement from

the division reserve. One company of 1/21 was ordered to report to the 3rd Marines immediately, the shore party on the Red Beaches was alerted to back up the lines on the left, and priority of air support was given to the 3rd Marines. Offshore the fire support ships that had illuminated and fired harassing fires in the Agana area all night were anxious to give all the help they could, but the enemy was too close to the Marine lines. The commander of the destroyer McKee could see Japanese troops attacking the men on Chonito Cliff, but could not obtain permission to fire from control parties ashore.15

While some Japanese units made frontal attacks on the Marine positions, others found their way along the dry stream bed that cut between Adelup Point and the looming cliffs. These attackers moved through the 3/3 command post area and began climbing the slopes in the rear of the Marine foxholes. Fire from Lieutenant Colonel Houser’s headquarters troops and from supporting LVTs eventually stopped this thrust and eliminated the remaining Japanese that had penetrated the lines.16 By 0830, the enemy had started to withdraw and the threat of the counterattack was ended. On the heels of the retreating Japanese, the Marines began to advance but the enemy was able to throw up an almost impenetrable barrier of artillery, mortar, and small arms fire.

The nature of the Japanese counterattacks, and of the terrain that gave them added impetus, provided the pattern for the American response. Originally, the 3rd Division had scheduled a three-regiment attack for 0700 on the 22nd. Now the 21st Marines held fast, since any advance would dangerously expose its left flank. The 3rd Marines had to come abreast of the 21st to make a concerted advance possible. The key to that advance appeared to be possession of Bundschu Ridge. Until the 3rd Marines could win its way to the top of this well-defended salient, there could be little progress on the left or center of the 3rd Division lines.

The situation was different on the right, where Colonel Craig’s regiment fought its way into the flats beyond Asan Point and eliminated most of the defending company of the 320th Battalion in the process. Elements of 3/18 then attempted to slow the Marine advance during the rest of the day. After nightfall, as the enemy battalion commander prepared to launch a counterattack, he was ordered instead to move most of his men, supplies, and equipment into the hills east of the 9th Marines positions. The Japanese were concentrating their remaining strength on the high ground, and the 18th Infantry was to hold the left flank of the main defensive positions. As a result of this withdrawal, only small delaying groups countered the advance of 1/9 and 2/9 when they jumped off at 0715 on 22 July.

Inside of two hours the assault companies of both battalions were consolidating their hold on the day’s first objective, the high ground along the Tatgua River. Resistance was light and plans were laid for a further advance which would include seizure of the villages of Tepungan and Piti. At

1300, the battalions moved out again, and by 1700, 2/9 had captured both villages and the shell and bomb-pocked ruins of the Piti Navy Yard as well. Inland, the 1st Battalion had kept pace with difficulty, as it climbed across the brush-covered slopes and gulleys that blocked its path. It was obvious that the Japanese had been there in strength; recently abandoned defensive positions were plentiful. The fire of the few enemy soldiers that remained, however, kept the advancing Marines wary and quick to deploy and reply in kind.

While 1/9 and 2/9 were driving forward to secure the coastal flats and their bordering hills, Colonel Craig was readying 3/9 for the assault on Cabras Island. The regimental weapons company, a company of Shermans from the 3rd Tank Battalion, and 18 LVT(A)s from the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion were all alerted to support the infantry, which would make a shore-to-shore attack mounted in LVTs. The morning advance of the regiment had uncovered an area, near the mouth of the Tatgua River, that Craig had designated for the assembly of troops and amphibious vehicles.

Shortly after 1400, the armored amphibians crawled out across the reef and began shelling the beaches on the eastern end of Cabras. The tractor-borne assault platoons followed, avoiding the mined causeway and moving across the reef and water. At 1425, they clattered ashore on the elongated islet.17 There was no defending fire, but there was a defense. Marines soon found that the ground was liberally strewn with mines spread out beneath a blanket of thick brush; as a result, the going was cautious and slow. At 1650, Major Hubbard reported that 3/9 had advanced 400 yards without making enemy contact, but that the combination of mines and brambles would keep his men from reaching the end of the island before dark. On order, the battalion halted and set up for night defense; two platoons of tanks reinforced the beach positions. With no opposition in sight, the early capture of Cabras on 23 July seemed assured.

Although the situation of the 9th Marines was a favorable one, the regiment was fully committed and holding far longer lines than either the 3rd or the 21st. Impressed by the need for strengthening his positions on the left and center of the beachhead and for maintaining the impetus of the attack, General Turnage asked General Geiger to attach a regimental combat team of the corps reserve to the 3rd Marine Division. The one reserve infantry battalion that was available to the division commander was “40% depleted”18 as a result of two days’ combat, as 2/21 had been pulled out of the cliff positions it had defended so ably and replaced by 1/21 late on the 22nd. Colonel Butler, wanting to give maximum effect to any 21st Marines attack on W plus 2, had requested the switch of battalions in division reserve and the last units were

exchanged in place on the shell-battered heights at 2115.

When Lieutenant Colonel Williams’ battalion moved into the lines, it had the responsibility of extending the zone of action of the 21st Marines 200 yards to the left of the regimental boundary, which had remained unchanged since the landing. This shift, which appeared to offer a better control point for contact, had been directed by General Turnage in order to improve the opportunity for the 3rd and 21st Marines to link their frontline positions. The gap had opened and stayed open, not as a result of a lack of will but of a way, to close it. Patrols attempting to find a lateral route which joined the flanks of 1/3 and 2/21 (later 1/21) could find none that did not include a time-consuming return to the lower slopes back of the beaches. No amount of maps, terrain models, or aerial photographs, nor advance intelligence from former island residents, could do full justice to the nightmare of twisting ravines, jumbled rocks, and steep cliffs that hid beneath the dense vegetation.

With such terrain on its flanks and upper reaches, Bundschu Ridge was a natural fortress for the relative handful of Japanese troops that defended it. Throughout the fighting on 22 July, Major Aplington tried repeatedly to work some of his men up onto the high ground that appeared to lead to the enemy positions. Using Company C on the right and coordinating his attack with Company E of 2/3 on the left, the 1st Battalion commander maintained constant pressure on the Japanese, but could make no permanent headway. Despite some temporary success, Marine units that fought their way to the high ground could not hold what they had won in the face of punishing enemy mortar and machine gun fire. About the only encouraging event in the day’s action came near nightfall, when the remnants of Company A were finally able to pull out of exposed positions on the nose of Bundschu Ridge, after Japanese fire, which had pinned them down, slackened and then ceased.

General Turnage planned an all-out attempt to erase the Bundschu salient on 23 July and to make sure that there was a firm and permanent juncture between the 3rd and 21st Marines. In a way, the Japanese helped him by sacrificing more of their men in another fruitless attempt to break through the left flank positions of the 21st Marines on the night of 22-23 July. The counterattack that developed against 1/21 was not the one, however, that was planned. The operations officer of the 29th Division, Lieutenant Colonel Hideyuki Takeda, had issued careful instructions to the commander of the 321st Independent Infantry Battalion to work his assault units up close to the Marine lines, to throw grenades at the unsuspecting Americans, and then to withdraw in the resulting confusion.19 In the heat of combat, the enemy assault platoon commanders ignored their orders and charged the Marines. The results were devastating. Japanese casualties were heavy, and only about 50 men of what had been a 488-man

battalion remained when the last attackers pulled back at about 0300.

The losses suffered by the Japanese in this attack, and the steady attrition of two days of battle, were rapidly thinning the ranks of the 29th Division and 44th IMB. Although there were thousands of service and support troops of varying quality left alive to fight, the number of veteran infantrymen was fast shrinking. The valley between Fonte Plateau and Mt. Macajna, site of the division field hospital and that of the naval guard force too, was crowded with wounded men. Aggravating the medical situation was the fact that the Fonte River, which coursed the valley, was so fouled by blood and bodies that it could not be used as a source of drinking water. Thirsty Japanese troops holding the arc of Asan defenses received short water rations from the small supply that could be carried in from Sinajana.

The enemy situation was deteriorating and no one knew it better than General Takashina. His aggressive defensive tactics had cost him many casualties. Faced with what appeared to be almost certain defeat by a superior force, he had the choice of conserving his strength and prolonging the battle as long as possible or trying to obtain a decisive advantage by a massive, coordinated counterattack. By the 23rd, the enemy division commander had made his decision, the key decision in the Japanese defense of Guam. He would stage a full-blown attack employing all the men and guns he could bring to bear on IIIAC positions, while he still had substantial strength in veteran troops. At 1300 on the 23rd, he issued orders outlining areas of responsibility for combat and support units in preparing for the assault.

A lot of fighting, and a lot more casualties on both sides, occurred before the Japanese were ready to strike. On the morning of the 23rd, the 3rd Marines continued its attack to seize a firmer hold on the ridges which overlooked every part of the beachhead. To give Major Aplington more men, and thus a better chance to bridge the troublesome gap between the 3rd and 21st Marines, Colonel Hall attached to 1/3 a provisional infantry company formed from his regimental weapons company. Referring to Bundschu Ridge, he reported:–

I am going to try to advance up that mess in front of me. What I really need is a battalion whereas I have only 160 men to use on that 500-yard slope. They might move to the top but they couldn’t advance on. Company A is down to about 30-40 men with an air liaison officer in charge. Company E is down to half strength. They have no strength to push on.20

To give the new thrust as much impetus as possible, every available supporting weapon—naval guns and carrier air, field and antiaircraft artillery, half-tracks and tanks—bombarded the wooded slopes ahead of the 3rd Marines before the regiment attacked at 0900. In the center, parallel drives by the 1st and 2nd Battalions converged on the Bundschu strongpoint, but the Japanese position was strangely silent. During the night, the enemy had pulled back to fight again on some other ridge of the many that still lay ahead of the Marines. Defense of Bundschu had cost the 9th Company, 38th Infantry,

Map 27: 3rd Marine Division Progress, 22-26 July 1944

30 casualties, but the return exacted from the 3rd Marines was far greater.

Assault platoons of 1/3 and 2/3 linked up atop the ridge at 1108, and the battalions spent the rest of the day cleaning out nests of enemy riflemen and machine gunners who held out in deftly hidden cliff side and ravine defenses within the Marine lines. The concealment offered the Japanese by the dense vegetation and the cover by numerous caves and bunkers made the task of consolidating the newly won positions a formidable one. The incredible complexity of the cut-up terrain in this relatively small area was clearly demonstrated by the failure of all attempts to make permanent contact on the frontline boundary between the 3rd and 21st Marines, On the 23rd, a 1/3 patrol in radio contact with both regiments moved out from the left flank of 1/21 and “attempting to rejoin its own lines in broad daylight, over a gap of a few hundred yards ... was lost.” The 3rd Division comment on the plight of the patrol was sympathetic, noting that “the innumerable gulleys, valleys, and ridges might as well have been gorges and mountains.”21

The continued existence of the gap plagued Marine commanders, but the Japanese did little to exploit its potential.22 In fact, they, like the Marines, peppered the area with mortar fire at night to discourage infiltrators.

What the Japanese were really concerned about was readily apparent on the 23rd, once 3/3 opened its attack. The enemy reaction was swift, violent, and sustained; a heavy fire fight ensued. Lieutenant Colonel Houser’s battalion, by virtue of its hard-won positions at Adelup Point and Chonito Cliff, threatened to gain command of the Mt. Tenjo Road where it climbed to the heights. Once the Marines controlled this vital section of the road, tanks and half-tracks could make their way up to Fonte Plateau and bring their guns to bear on the enemy defenses that were holding back the units in the center of the 3rd division line.

During the morning’s fighting, Houser was hit in the shoulder and evacuated; his executive officer, Major Royal R. Bastian, took command of 3/3. At 1217, the major reported that his assault companies, I and K, had seized the forward slopes of the last ridge before the cliff dropped off sharply to the rear and the Fonte River valley. The Japanese used their positions on the reverse slope to launch counterattacks that sorely pressed the Marine assault troops. Major Bastian put every available rifleman into the front, paring down supporting weapons crews for reinforcements, and his lines held. By 1400, Colonel Hall was ordering all his units to consolidate their hold on the ground they had won and to tie in solidly for night defense.

The main thrust of the 3rd Division attack on 23 July was on the left flank; the rest of the division kept pressure on the Japanese to its front. The battalion on the right of the 3rd Marines, 1/21, had its hands full destroying a network of caves and emplacements that covered the sides of a depression just forward of its nighttime positions. The 3rd Battalion,

21st Marines spent the day improving its positions, establishing outposts well forward of its lines, and tangling with small groups of Japanese, who themselves were scouting the American defenses. In general, the right half of Colonel Butler’s zone of action was as quiet as it had been since the night of W-Day.

This absence of significant enemy activity carried over into the 9th Marines zone. Squad-sized Japanese units made sporadic harassing attacks both day and night, but there was little organized enemy opposition. The 3rd Battalion finished its occupation of Cabras Island early in the morning and at division order, turned over control of the island to the 14th Defense Battalion at 0900. An hour later, Colonel Craig received word from division that his 2nd Battalion would replace 2/21 in division reserve. The regimental commander ordered 3/9 to take over the lines held by Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s unit. The relief was effected at 1230, and Cushman moved 2/9 to the positions formerly occupied by 2/21.

Once it was released to Colonel Butler’s control, Lieutenant Colonel Smoak’s battalion moved to an assembly area near the 21st Marines left boundary. In the attack on the 24th, 2/21, which was all too familiar with the rugged terrain, would spark the drive to close the gap between regiments. The lone infantry battalion in reserve was all that General Turnage could spare from the front lines; he had learned earlier in the day that he could expect no immediate reinforcement from the IIIAC reserve. General Geiger had decided that the situation ashore did not warrant the landing of a 77th Division combat team in the Asan beachhead.

Enemy activity was markedly less after dark on the 23rd than it had been on previous nights. Only 2/21 was seriously threatened, and the Japanese thrust at its lines was turned back by artillery and naval gunfire. Since most of the 3rd Division front was held by strongpoints only, the support provided by the howitzers of the 12th Marines and the guns of destroyers and cruisers standing by offshore was vital. The constant harassing fire laid on enemy-held territory and the prompt interdiction of actual or suspected routes of approach to the American positions held the Japanese in check.

The fourth day of attacks to expand the 3rd Division beachhead saw no spectacular gains, but Marine assault platoons were able to make steady progress. Yard by yard, they increased their hold on the high ground, and, on the left particularly, won positions that gave access to the Mt. Tenjo Road. Not unexpectedly, the hardest fighting took place in a densely wooded draw in the troublesome boundary area between the 3rd and 21st Marines.

Lieutenant Colonel Smoak’s battalion stirred up a hornet’s nest when it attempted to center its drive to the heights on the draw. In it, Japanese troops were set up in mutually supporting cave positions whose machine guns drove the Marines to cover. Emboldened by this temporary success, the enemy made two counterattacks, which were readily beaten back. Assault units, moving upward on the flanks of the Japanese position, were able to bring fire to bear on the caves, but could not silence the enemy guns. A supporting

air strike at 1205 enabled a platoon working its way up the bottom of the draw to advance 200 yards before heavy fire again forced a halt. This time the carrier planes, although they were mainly on target, dropped three bombs amongst the Marines, causing 17 casualties. Although this unfortunate accident marked the end of the day’s advance, 2/21 had accomplished its mission. When Smoak adjusted his lines for night defense, he was able to tie in strongly with both 1/3 and 1/21. The gap was finally closed.

Highlighting the action on this same day, in the relatively quiet sector of the 9th Marines, was the first attempt to contact the brigade. In the morning, a 30-man patrol worked its way south along the Piti-Sumay Road, while a covey of six LVT(A)s guarded its Apra Harbor flank. Scattered rifle and machine gun fire coming from the high ground inland, coupled with fragments flying from a bombing and shelling of Orote Peninsula forced the patrol to turn back after it had gone 2,600 yards. It found evidence that the Japanese had once occupied the area in force and discovered “huge dumps of all classes of supply near the [Aguada River] power plant, enough to service a regiment, but no traces of the regiment.”23

If the 18th Infantry had disappeared from one shore of the harbor, there was ample evidence to show that there was no lack of Japanese on the other side. Soon after night fell on the 24th, the 9th Marines spotted enemy barges along the coast of Orote near Sumay, star shells were fired by the call fire support ship assigned to the regiment, the destroyer Franks ,24 and the area of Japanese activity was hammered by newly emplaced 90-mm guns of the 14th Defense Battalion on Cabras Island. At 2010, after receiving permission from the shore fire control party with 3/9, which was spotting for it, the Franks illuminated the suspected area with its searchlight in order to conserve star shells.25 The light on the ship was shuttered when two 14th Defense searchlights on Cabras took over the sweeping search of cliff, beach, and water, looking for targets for the 90s. The night’s events showed plainly that the Japanese on Orote Peninsula were stirring. The Marine observers who knew it best were those who were charged with its capture.

Closing Off Orote Peninsula26

The heavy losses suffered by the enemy 38th Infantry in its counterattack on the 1st Marine Brigade perimeter opened the way for a rapid advance on

the 22nd. Isolated from the rest of the Japanese garrison, the remaining troops were incapable of fighting a delaying action on all fronts. The enemy could muster strength enough to put up a stiff fight to block one route of advance—the road to Orote Peninsula. The task of opening that road fell to the 22nd Marines; the rest of the brigade was charged with the mission of reaching and securing the Final Beachhead Line where it ran along the Alifan–Taene massif, crossed Maanot Pass, and reached the high ground leading to Mt. Tenjo. (See Map 26.)

General Shepherd’s plan for the brigade operations on W plus 1 called for the 1st and 3rd Battalions of Colonel Tanzola’s 305th Infantry to pass through the left flank of the 4th Marines and attack to seize and hold Maanot Pass. The 2nd Battalion of the 305th was to remain in brigade reserve. The 305th was given responsibility for maintaining contact with the 22nd Marines, which was to move out echeloned to the left rear of the Army regiment, making its main effort on the left along the Agat-Sumay Road. The initial objective of the 4th Marines was the capture of Mt. Alifan and the seizure of the ridge leading toward Mt. Taene. Once the regiment secured this commanding ground, 3/4 was to drive south to take Magpo Point, extending the south flank of the beachhead 1,200-1,500 yards beyond Hill 40 and Bangi Point.

By 0740, it became apparent that 1/305 and 3/305 would need several hours to regroup and reorganize after the unavoidable delay and disorganization resulting from their nighttime landing, Consequently, General Shepherd ordered 2/305 to move forward and relieve 2/4 in position. The 4th and 22nd Marines jumped off at 0900, and the 305th followed suit an hour later, passing through elements of both 2/305 and 2/4 and striking northeast through Maanot Pass. Colonel Tanzola’s men found their first taste of combat an easy one to take. Except for scattered opposition by individuals and the sporadic fire of one mortar, the regiment met little resistance. The 3rd Battalion, on the left, took its part of the day’s objective by 1300, and the 1st Battalion, slowed by thick underbrush and more rugged terrain, came up on line at dusk. Most supporting units of the 305th RCT, including half-tracks, antitank guns, and tanks, came ashore during the day, and the 305th Field Artillery moved into firing positions and registered its 105-mm howitzers.27

The terrain problems posed by the heavily wooded slopes that slowed the advance of 1/305 were multiplied in the zone of the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines. The day’s objective included the top of Mt. Alifan and the direction of advance was up. The steep sides of the mountain were covered with dense, thorny undergrowth, and only a few trails wound their way through the sprawling tree roots and tangled vines. The mountain itself was a formidable obstacle, but the Japanese made it even more difficult. On the lower slopes, bunkers, reinforced with coconut logs, and some of the numerous caves contained Japanese defenders. These were

methodically eliminated by the grenades and rifle fire of assault squads of Company C and Company G, attached to 1/4 after the 2nd Battalion was relieved by the 305th Infantry.

At about noon, the climb for the mountain peak began, an ascent that grew steadily tougher as the Marines went higher. Fortunately, the Japanese did not contest the last stages of the advance when packs and all excess gear were discarded to lessen the burden on the sweating climbers. Finally, at 1530, a patrol reached the very top, where it could see the other side of the island. The peak proved to be indefensible, so night positions were dug in on the lower slopes, where 1/4 tied in with 1/305 on the left. On the right, where the lines of the battalion extended southwest along the ridge leading to Mt. Taene, the flank hung open.

In order to help block this gap, Company E of 2/4 was attached to 3/4 late in the afternoon of the 22nd. Major Hoyler’s companies had begun their attack at 1100 to extend the beachhead south. Resistance was light on all company fronts, and naval gunfire, artillery, and mortars helped discourage any Japanese attempt to hold in strength. Company K, advancing across the low, rolling ground along the shore, was supported by a platoon of Shermans, which knocked out enemy machine gun nests before they could do any damage. Once the battalion had reached and secured Magpo Point, extending its lines inland, the tanks set up close to the frontlines to bolster night defenses. There was no significant number of Japanese in front of 3/4, however, to stage a repeat of the wild counterattack on the first night ashore. The few survivors of 1/38 and 3/38 were already assembling behind Mt. Tenjo to move north to Ordot.

The pattern of light and scattered resistance, which marked the advance of the other regiment of the brigade, was repeated in the right portion of the 22nd Marines zone of action. Moving out at 0900, 2/22 had little difficulty in eliminating the few Japanese it met; naval gunfire knocked out several pillboxes, which might have meant more serious opposition. The battalion was held up more by the extreme difficulty of getting supplies up to its assault platoons than it was by enemy activity. LVTs, which might have negotiated the broken, trackless ground, were in such short supply and so vital to the ship-to-shore movement that General Shepherd forbade their use inland except in emergency situations.

Along the shore, where 1/22 attacked astride the Agat-Sumay Road, the supply situation was not a problem but amphibian tractors were still needed. Here the call went out for LVT(A)s to act in lieu of tanks and half-tracks. During the morning’s action, mediums of the 22nd Marines Tank Company helped clear the way through partially abandoned defenses outside Agat, where the enemy had held up the advance on W-Day. Armor had to stop at the Ayuja River, since the only bridge over it had been demolished and the banks were too steep for fording. When the request went back for engineers, LVT(A)s were asked for too, and a platoon was ordered up, to come in by sea if necessary, in order to join the advancing infantry. By late afternoon, Company C of 1/22 had taken Road Junction 5 (RJ 5) and won its

way about 300 yards beyond, fighting through a nest of enemy pillboxes. Company A on the right flank had crossed Old Agat Road. At 1800, Lieutenant Colonel Fromhold ordered his men to dig in along a line about 50-100 yards back of their farthest advances in order to set up stronger defensive positions tied in with 2/22.

The second night ashore in the southern beachhead was a relatively quiet one. There were infiltration attempts at various points all along the perimeter and occasional fires from Japanese mortars and artillery emplaced on Orote Peninsula, but no serious threats to the perimeter. Should another large-scale counterattack come, however, it would be met by a markedly increased volume of supporting fires. Most of the men and guns of General del Valle’s III Corps Artillery had landed during the day; the “Long Toms” of the 7th 155-mm Gun Battalion to support the 3rd Division and the shorter range pieces of the 1st and 2nd 155-mm Howitzer Battalions to reinforce the fires of the 1st Brigade and the 77th Division.28 The Light Antiaircraft Group of the 9th Defense Battalion had landed on the 22nd also and sited its .50 caliber machine guns and 20-mm and 40-mm guns in positions where they could improve beach defenses. Lieutenant Colonel Archie E. O’Neill, commanding the 9th Defense Battalion, was placed in charge of all shore party, LVT, and LVT(A) units used to defend the beaches and inland beach area perimeter.29

On 23 July, General Geiger was prepared to send thousands of men and guns of the 77th Division ashore in keeping with the prelanding scheme of maneuver. The corps commander conferred with General Bruce early on the 22nd and authorized the landing of all but one infantry regiment of the floating reserve. The 307th RCT, less its reinforcing artillery battalion, was to stay on board ship for the time being while the need for its commitment in the 3rd Division beachhead was assessed. General Bruce issued warning orders for the landing to all units of his division at 1400 on the 22nd and followed through with a request to Admiral Reifsnider that the 306th RCT be landed on White Beach 2 at the earliest practicable daylight hour on the 23rd. The Army regiment, commanded by Colonel Aubrey D. Smith, was slated to relieve the 4th Marines in its positions along the southern flank of the beachhead.

At 0800 on the 23rd, the 22nd Marines and the 305th Infantry attacked to seize an objective line that ran across the neck of Orote Peninsula to Apra Harbor and then southeast to the ridge leading to Mt. Tenjo and south along commanding ground to Maanot Pass. The 305th, with the 1st and 3rd Battalions in assault, encountered little opposition to its advance and secured its objective, part of the FBHL, without difficulty. By the day’s end, Colonel Tanzola’s regiment was digging strong

defensive positions along the high ground overlooking Orote Peninsula.

General Bruce had intended to relieve the 4th Marines with the 306th Infantry by nightfall on the 23rd so that the Marine regiment could move north to take part in the brigade attack on Orote Peninsula. Since no LVTs or DUKWs could be spared from resupply runs, the soldiers of the 306th had to wade ashore, like those of the 305th before them. Admiral Reifsnider recommended that the men come in at half tide at noon, when the water over the reef would be about waist deep. This timing precluded the early relief of the 4th Marines. The first battalion to land, 3/306, began trudging through the water at about 1130. Three hours later, the Army unit, reinforced by a company of 1/306, began relieving 3/4 in place; a platoon of Marine 37-mm guns and one of Sherman tanks remained in position as a temporary measure to strengthen night defenses. The remainder of Colonel Smith’s combat team came ashore during the afternoon and went into bivouac behind the 4th Marines lines. Colonels Smith and Tanzola met with General Bruce in the 77th Division advance CP ashore at 1400 to receive orders for the next day’s action, when the division would take over responsibility for most of the brigade-held perimeter.

Once it was relieved, the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines was ordered to move to positions near Agat and was attached to the 22nd Marines as a nighttime reserve. One company of the 4th, F, had already been attached to the 22nd as a reserve during the day, and a platoon of the 4th Marines tanks was also sent to back up the regiment driving towards Orote.

During the morning’s advance, the 22nd Marines had met only light resistance. The Japanese appeared to be falling back before the assault platoons of 1/22 and 2/22. Colonel Schneider’s regiment keyed its movement on Company I, attached to 1/22, which had relieved Company C as the unit charged with fighting its way up the Agat-Sumay Road. The attack plan called for the companies on the right of Company I to swing north and west across the neck of the peninsula. By noon, tanks were again available to support the attack, since a tank dozer and tankmen armed with pick and shovels had built a causeway across the Ayuja.

Prior to the attempt to close off the neck of the peninsula, the attacking Marines paused while an intensive air, artillery, and naval gunfire preparation was laid on the difficult terrain that lay ahead. Much of the ground that lay between the Agat-Sumay and Old Agat Roads was covered with rice paddies interspersed with small hillocks and stretches of thick brush. It was terrain calculated to spread the attacking troops thin and to make contact and any concentration of unit strength difficult. The defending Japanese infantry, presumably from 2/38, had organized the ground effectively, taking good advantage of natural obstacles. Enemy supporting artillery and heavy mortars on Orote Peninsula, well registered in the area of Marine advance, frequently timed their fires to coincide with American preparations, a practice that led to a rash of reports about American fires falling short into friendly lines.

Once the Marines jumped off, they found that the little hills ahead were infested with enemy riflemen and machine gunners. When squads of men advanced into the open paddies, small arms and light mortar fire pinned them down in the mud and water. Heavier guns positioned on Orote raked the lines with enfilade fire. Stretcher bearers and ammunition carriers attempting to reach the front lines were driven back by the hail of explosions, only to come on again with the needed aid. Supporting tanks could not maneuver in the soft footing of the paddies, and when they tried to use the roads, one was knocked out by 37-mm antitank fire and another was disabled by a mine. In a wearying afternoon marked by repeated but fruitless attempts to reach its objective, the 22nd Marines suffered over a hundred casualties. As darkness approached, the units that had been pinned down were able to shake loose and pull back to better night defensive positions along the Old Agat Road, giving up about 400 yards of untenable ground in the process.

On the night of 23-24 July, there was still a considerable hole between the flank units of the 305th Infantry and the 22nd Marines, but the Japanese took no advantage of the gap. Instead, at about 0200, counterattacks by small units, attempts at infiltration, and harassing fires from mortars and artillery were directed against the Marine positions along Old Agat Road at the boundary between 1/22 and 2/22. The Brigade Artillery Group was quick to respond to requests for supporting fire, and the fire support ships offshore joined in with increased illumination and heavy doses of 5-inch high explosive. The flurry of Japanese activity died away quickly beneath the smother of supporting fires.

General Shepherd and his operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas A. Culhane, Jr., worked out a plan of attack for the 24th that was designed to outflank the Japanese defensive complex encountered on 23 July. Issued at midnight, the brigade operation order called for two battalions of the 22nd Marines to attack in column on a 200-yard front with the left flank resting on the coast. Once through the narrow corridor between the rice paddies and the sea, the trailing battalion would extend to the right, seize en route the troublesome hill defenses that had stopped the previous day’s attack, and then drive for the shore of Apra Harbor on a two-battalion front. In an attack simultaneous with the main thrust up the Agat-Sumay Road, the remaining battalion of the 22nd would advance on a 400-yard front on the right of the regimental zone, jumping off from Old Agat Road with an objective of seizing and holding the shore of Apra Harbor. The 4th Marines, when relieved by the 306th Infantry, would assemble in brigade reserve in the vicinity of RJ 5. One platoon of the 4th Marines tanks and a platoon of LVT(A)s would be attached to the 22nd Marines to beef up the attack along the coast.

The time of the attack was set for 0900 following a lengthy softening-up of the target by air, naval gunfire, and artillery, with corps 155-mm howitzers adding their heavier metal to the fires of the brigade 75s. The attack was delayed an hour to increase the effect

of cruiser and destroyer bombardment along the southern coast of Orote Peninsula, where suspected and known Japanese positions could pour fire into the western flank of the attacking Marines. At 1000, Company C of 1/22 led off a column of companies driving forward from a line of departure at Apaca Point. The regimental tank company, reinforced by the platoon of the 4th Marines Shermans, moved out with the assault rifle squads.

The enemy reaction to the advance of 1/22 was immediate; artillery and mortar shells exploded among the leading units and automatic weapons fire whipped across the front. Taking advantage of natural cover and of the shelter provided by the tank armor, riflemen of Company C kept moving forward. When five enemy tanks suddenly appeared to block the advance, the Marine mediums made quick work of destroying them, and continued forward using their 75-mm guns and machine guns to blast concrete and coconut log emplacements.30 As the leading units reached the area beyond the rice paddies, fire from enemy guns concealed in the cliffs of Orote near Neye Island became so troublesome that two gunboats were dispatched to knock them out. In a close-in duel, both craft, LCI(G)s 366 and 439, were hit by enemy fire and suffered casualties of 5 killed and 26 wounded.31 But their 20-mm and 40-mm cannonade beat down the fire of the Japanese guns, and a destroyer came up to add 5-inch insurance that they would remain silent.

At 1400, after the ship and shore gun battle had subsided, the rest of 1/22 started moving up on the right of Company C. The 3rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Clair W. Shisler), echeloned to the right rear of the 1st, now had maneuver room to attack and roll up the line of enemy positions that had held up the 22nd Marines’ attack across the rice paddies on W plus 2. Moving quickly, 3/22 took and demolished the strongpoint and then turned north toward the harbor. Lieutenant Colonel Shisler’s companies encountered the same type of light-to-moderate small arms, artillery, and mortar fire that confronted 1/22 and the going over rugged terrain was slow. By dusk, the 1st Battalion was dug in on its objective, but the 3rd Battalion had to set up its night defensive perimeter about 400 yards short of the harbor shore. This gap was well covered, however, as a result of the success of the attack by 2/22 on the right of the regiment.

Lieutenant Colonel Hart’s battalion was getting ready to move out from Old Agat Road at 1000 when lead elements were hit by fire, which appeared to herald an enemy counterattack. At almost the same time, fragments from the heavy naval shelling in support of the Marine attack began hitting along the front lines. While the troops were waiting for this fire to be lifted and moved farther ahead, they spotted a column of about 100 Japanese moving across the front towards the flank

of 1/22. Mortar and artillery fire was called down on the enemy, scattering the group, and the Marine battalion prepared for a counterattack, but none came. Once the confusion caused by the shelling and the abortive counterattack was straightened out, the attack was rescheduled. At 1300, 2/22 moved out with patrols to the front and overran a succession of small dumps and abandoned cave positions along the road; the latter were seared by flamethrowers to eliminate any stragglers. Only a few Japanese were encountered in the advance to the harbor and these were soon killed.

Once 2/22 had reached its objective, it was ordered to continue its advance east along the coast and to occupy the high ground at the road junction village of Atantano. In late afternoon, while it was moving into position through the dense underbrush which blanketed the area, the battalion was harassed by enemy fire. In view of its exposed position, 2/22 was reinforced for the night by Company F of 2/4, which marched into the Atantano perimeter at about 1850. The remainder of 2/4, attached to the 22nd Marines as a nighttime reserve, was moved up after dark to the Old Agat Road, where it set up all-around defenses to plug the gap between 3/22 and 2/22.

All units of the 4th Marines were available to back up the 22nd by the evening of 24 July as a result of the day’s shifting of troops and reorganization of areas of responsibility within the southern beachhead. At 0800, the 77th Division assumed control of the entire perimeter east of Old Agat Road, and the 306th Infantry took command of the defenses formerly held by the 4th Marines. During the morning and early afternoon, elements of the 306th relieved companies of 1/4 in position. At 1400, while Lieutenant Colonel Shapley’s Marines were shifting to a bivouac area north of Agat, General Bruce opened his CP ashore close to the area where the 307th Infantry was assembling after a rough passage to shore.

On the 23rd, General Bruce had requested that two battalions of the 307th be landed and placed under his command so that he would have enough men to expand the perimeter to the originally planned FBHL. General Geiger felt that this expansion, which involved the movement of the southern flank over 3,000 yards south to Facpi Point, was no longer desirable or necessary. The move would also leave IIIAC with only one uncommitted infantry battalion in reserve. The corps commander did decide, however, that the situation now warranted the landing of the reserve, to remain under corps control. The 307th began crossing the reef at 1300 on the 24th. The luckless soldiers had to wade to the beach, like all 77th Division infantrymen before them. Their ship to shore movement was complicated by heavy ground swells raised by a storm at sea; two men were lost when they fell from nets while clambering down the sides of rolling transports into bobbing LCVPs.

The landing of the last major element of IIIAC on 24 July found both beachheads soundly held and adequately supplied. The price of that secure hold was high to both sides. The III Corps count of enemy dead consisted of the conservative figure of

623 bodies buried by the 3rd Division and the 1st Brigade estimate of 1,776 Japanese killed. By enemy account of the four days’ fighting, the casualty totals must have been significantly higher, particularly on the Asan front. In winning its hold on the heights, the 3rd Marine Division had had 282 of its men killed, 1,626 wounded, and had counted 122 missing in action. For the same period, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade casualty totals were 137 killed, 700 wounded, and 87 missing; the 77th Infantry Division had lost 12 men and had 20 wounded.

Supply and Evacuation32

By nightfall of W plus 3, most of the logistical problems that had arisen during the first days of the assault phase had been solved. For Guam, the majority of such problems had been anticipated and countered by a proper mix of ships, service troops, and equipment. The veteran planners of TF 53 and IIIAC were well aware that the success of an amphibious operation depended as much upon rapid and effective unloading and distribution of supplies as it did upon the courage and aggressiveness of assault troops. Profiting from lessons learned in earlier campaigns, the task force vessels and shore parties were able to put an average of 5,000 tons of vehicles, supplies, and equipment ashore in both beachheads during each of the first four days.

The prime obstacle to unloading progress was the reef which denied landing craft access to shore. And the prime weapon in combatting the reef was the LVT. The III Corps logistics officer observed that without them “the unloading of assault shipping would have proceeded only under greatest difficulty.”33 Hampered only by the limitation that it could not operate effectively in rough or irregular terrain, the DUKW was almost equally useful. The amphibious vehicles were used everywhere on the reef and in the immediate beach and dump area, and, as most men of the 77th Division discovered, proved to be too valuable as cargo carriers to be used to transport troops after the assault waves landed. As a result of their almost continuous operation, many of the vehicles were deadlined by operational mishaps and mechanical failures. Herculean efforts by crewmen and mechanics kept the daily unserviceability rate to about 35 percent for amphibian tractors and 40 percent for amphibian trucks. Spare parts were at a premium, particularly for the newly acquired DUKWs of III Corps Motor Transport Battalion, and vehicles knocked out by enemy guns and others wrecked by surf and reef obstacles were cannibalized to keep cripples going.

The pontoon barges and cranes at reef edge were a vital part of the unloading process. In the shallower water over the coral shelf off Asan, versatile tractor-mounted cranes could maneuver in waist-deep water dragging, lifting, and carrying as the load to be landed required. Where the water was too deep off both Asan and

Agat, the barge-mounted cranes swung bulging cargo nets from boats to vehicles and lifted out the heavy drums of fuel and water that were often floated and pushed to the beaches by men of the reef transfer battalions.34 Since few wheeled vehicles could make shore under their own power, tractors and LVTs were used to tow most trucks from the ramps of LSTs onto dry land.

By 24 July, nine LST unloading points had been opened on the reef off each beachhead and landing ships had been about half emptied. The transports and cargo vessels that had carried the assault units to the island were 90 percent unloaded, and those that had brought the 77th Division had landed 25 percent of their cargo. At 1700, Admiral Conolly reported that 15 of the big ships were cleared of landing force supplies, and preparations were made to return the first convoy of those emptied to Eniwetok on 25 July.

Many of the APAs that had served as casualty receiving stations during the first days of fighting were among those that were sent back. The hospital ship, Solace, which arrived according to plan on 24 July, took on board some of the most seriously wounded patients from the transports lying offshore. The transports Rixey and Wharton, both remaining in the area, loaded those walking wounded that would require no more than two weeks hospitalization. Once the major unit hospitals were fully established ashore, these men would be landed to recuperate on Guam and rejoin their units. Many of the 581 casualties that filled the Solace when she sailed on W plus 5 were men loaded directly from the beaches that had been hit in the heavy fighting on 25 and 26 July.