Chapter 4: Continuing the offensive

Attack and Counterattack1

General Geiger’s original operation plan for the coordinated IIIAC advance on 25 July called for the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to begin its assault on the Japanese defenses of Orote Peninsula. When it became obvious on the 24th that the brigade would not be able to get into position by nightfall to mount a two-regiment attack, General Shepherd sent a message to the corps commander stating that in view of the:

... delay in the relief of the 4th Marines which was not completed until 1500 today, necessity for moving 4th Marines to assembly areas and relief of 22nd Marines in line, reorganization and preparation for attack, strongly recommend assault Orote Peninsula be delayed until 26 July.2

General Geiger quickly concurred in Shepherd’s recommendation and revised the order, setting forward the time of the Orote attack to 0700, 26 July. In the day gained, the brigade would attempt to seal the neck of the peninsula from sea to harbor.

After an uneventful night, marked only by harassing artillery and mortar fires falling on the lines of 1/22 and 3/22, Colonel Schneider’s regiment prepared to attack at 0830 on the 25th. Moving out behind a 15-minute artillery preparation by brigade 75s, the two assault battalions immediately ran into heavy enemy small arms fire coming from covered emplacements in the low, irregular hills ahead. Again enfilade fire from Neye Island and the cliffs near it raked the front of the advancing Marines. An air strike was called down on Neye, naval gunfire and artillery added their firepower, and 40-mm guns of the 9th Defense Battalion pounded the precipitous island shores from positions near Agat. Along the coast, half-tracks of the regimental weapons company moved to positions from which they could fire across the narrow stretch of water at the bend of the peninsula into caves and other likely gun positions which studded the cliffs.

The fury of supporting fires knocked out some but not all of the Japanese weapons. The attacking Marines, particularly those of Lieutenant Colonel Fromhold’s 1st Battalion, which was advancing along the coast, were hard

hit. At one point in the morning’s bitter fighting, Fromhold committed his last reserve platoon, reinforced by 20 men from the 4th Marines, to back up Company C, which was driving up the Agat-Sumay Road. Just before noon, five Japanese light tanks, accompanied by infantry, were spotted ahead of Company C, and Shermans of the 22nd Marines converged on the enemy armor. A short, sharp exchange left the Japanese tanks broken and aflame and scattered the enemy troops. Not long afterwards, bazookas and tanks of the 22nd accounted for at least two more Japanese tanks that were attacking Marines on the right of the 1/22 zone.3

Although the 1st Battalion encountered the stiffest enemy resistance during the day’s advance, 3/22 was also heavily engaged. As it swung into line and closed on the harbor shore, Lieutenant Colonel Shisler’s unit met increasingly stronger Japanese fire. By early afternoon, all evidence indicated that the brigade had run up against the main defenses of Orote. To bring fresh strength to bear in the attack ordered for 26 July, the 4th Marines began taking over the left of the brigade lines shortly after noon. Lieutenant Colonel Shapley was given oral orders to have his lead battalion, 1/4, mop up any Japanese resistance it encountered moving forward to relieve 1/22. General Shepherd moved his CP closer to the fighting and set up near RJ 5, not far from the bivouac area of the brigade reserve, 2/4. Well before dark, all brigade assault units were on the day’s objective, firmly dug in, and ready to jump off the following morning. (See Map 28.)

Manning the left half of the newly won positions was the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, with elements of three companies on line and a platoon of regimental tanks guarding the Agat-Sumay Road where it cut through the American defenses. The 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines was in position behind 1/4 ready to move into the front line as the peninsula widened and allowed for more maneuver room. On the brigade right was 3/22, occupying a low rise that overlooked an extensive mangrove swamp along the shore of Apra Harbor. Backing the 3rd Battalion was 1/22, which had moved after its relief to positions near the regimental boundary in the narrowed zone of the 22nd Marines. To augment night defenses on the extreme right flank where the Piti-Sumay Road paralleled the harbor shore, Colonel Schneider attached Company E of 2/22 to the 3rd Battalion.

During the day’s fighting, the 2nd Battalion of the 22nd, operating from Atantano, patrolled extensively and mopped up enemy holdouts in the area between the Old Agat Road and the brigade front lines. Firm contact was established with the left flank of the 77th Division, which spent the 25th consolidating its hold on the FBHL and landing more of its supplies and equipment. Patrols from General Bruce’s infantry battalions ranged the hills to the northeast, east, and south hunting down Japanese stragglers.

By the 25th, the 77th Division was also probing cautiously toward Mt. Tenjo, sending its patrols to scout approaches to the hill mass. The way

was rugged and the possibility of encountering enemy defenses in the high, broken ground seemed strong. Although the mountain peak was included within the 3rd Marine Division FBHL in prelanding plans, the pattern of Japanese resistance indicated that it might fall easier to American troops attacking from the south rather than the north. No significant enemy opposition was developed by the Army patrols as they moved further toward the Asan beachhead. Their negative findings matched the experience of patrols from the 9th Marines and 2/22, which made contact along the harbor shore near Atantano about 1600.

The events of 25 July indicated that Japanese troops were scarce in the area bordering Apra Harbor, but there was ample evidence that the enemy was still plentiful and full of fight everywhere else on the heights confronting the 3rd Division. Unknown to the Marines, the eve of the 29th Division counterattack had arrived, and the bitter resistance met in the day’s close combat by the 3rd and 21st Marines had been furnished by units that were trying to hold jump-off positions for the night of 25-26 July.

General Takashina’s orders to his troops were to concentrate in the general area from Fonte Plateau to “Mt. Mangan.” The latter name was given by the Japanese to a 100-foot-high hill about 1,500 yards southwest of Fonte Plateau. Mt. Mangan marked the junction of the Mt. Tenjo Road with a trail that branched off to the head of the Fonte River valley. One principal enemy assembly area faced the positions of the 3rd Marines, the other was in front of the lines of the 21st Marines. The 48th IMB, with the 10th IMR attached, was to launch its attack from a line stretching from the east side of Fonte Plateau to the east side of Mt. Mangan. The 18th Infantry was to move out from a line of departure running west from Mt. Mangan along the Mt. Tenjo Road. The naval troops that had helped hold the approaches to Agana against the 3rd Marines were to assemble in the hills east of the Fonte River and attack toward Adelup Point. Reinforcing the naval infantry, who were mainly former construction troops operating under the headquarters of the 54th Keibetai, would be the two companies of tanks that had remained hidden near Ordot since W-Day. (See Map VIII. )

Many of the veteran Japanese infantrymen scheduled to spearhead the counterattack were killed in the bloody fighting on the 25th. The bitterest contest was joined along Mt. Tenjo Road where it crossed Fonte Plateau. Here, the road fell mainly within the zone of action of Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines.

Cushman’s outfit was attached to the 3rd Marines at 0600 on the 25th and ordered to relieve 1/3 on the right of the regimental front line. By 0930, when the 3rd Marines moved out in attack, the relief was completed, and 1/3 supported the advance of 2/9 by fire. Once their fire was masked, Major Aplington’s badly depleted companies moved back to division reserve positions behind the 21st Marines and about 1,000 yards inland from Asan Point. Again General Turnage had only one understrength infantry battalion to back up the 3rd Division front; the regiments, with all battalions

committed, had no more than a company as reserve, the battalions frequently had only a platoon.

To both sides in the battle, the big difference in the fighting on 25 July was the presence of tanks on Fonte Plateau. Assault units of 3/3 and 2/3 blasted and burned their way through a barrier of enemy cave defenses and won control of the road to the heights within an hour after jump-off. Medium tanks of Company C, 3rd Tank Battalion rumbled up the road soon after the attack began and joined the infantry in destroying Japanese positions that blocked passage upward. After engineers cleared the roadway of some bomb-mines, which temporarily stopped the Shermans, the advance resumed with infantry spotters equipped with hand-held radios (SCR 536s) pointing out targets to the buttoned-up tank gunners. In midafternoon, General Turnage authorized Colonel Hall to hold up the attack of 2/3 so that the enemy positions bypassed during the day’s action could be mopped up prior to nightfall. At the same time, the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, driving toward Fonte, was ordered to continue its attack.

No tanks reached the high ground where 2/9 was fighting until late afternoon; enemy fire and mines had slowed their arrival. Support for the infantry attacking the Fonte defenses was furnished by naval guns, artillery, and mortars, reinforced by a nearly constant fusillade from light and heavy machine guns. The return fire of the Japanese inflicted severe casualties on the assault troops, but failed to halt the Marine advance into the broken terrain of the plateau. The battalion battled its way across the Mt. Tenjo Road and drove a salient into the enemy defenses of Fonte. At 1700, the reserve company, G, was committed on the left flank to lessen a gap which had opened between 2/3 and 2/9 during the afternoon’s advance.

As darkness approached, there was no letup in the ferocity of the enemy resistance and the close-in fighting continued to be costly to both sides. The situation prompted Lieutenant Colonel Cushman to pull back his forward elements on both flanks to secure better observation and fields of fire for night defense. While Companies E and G dug in close to the road, Company F in the center continued to hold a rocky prominence, about 150-200 yards to the front, that marked the limit of the day’s advance. When four tanks finally arrived at 1825, it was too dark to use them effectively so they were placed in supporting positions behind the lines. At this time, as the battalion action report noted: “The enemy was within hand grenade range along the entire line to the front and retained strong positions in caves to the right Co’s right rear.”4

These caves, bypassed during the morning’s advance, were left to the attention of a reserve rifle platoon. The resulting mop-up operation was only partially successful, and enemy troops continued to emerge from the caves for several days afterwards. Although these Japanese harassed the command post areas repeatedly, they were not in sufficient strength to have

a significant effect on the actions of 2/9.

In the zone of 2/21, which flanked that of 2/9, a similar pocket of enemy holdouts was left behind the lines when the 21st Marines attacked on 25 July. The Japanese, holed up in cave positions in the eastern draw of the Asan River, were wiped out by Company E during a morning’s hard fighting; later over 250 enemy bodies were buried in this area, which had been the target of heavy American air strikes on the 24th. Company E, once it had completed the mop-up mission, moved back into the attack with the rest of 2/21. Every foot of ground that fell to Lieutenant Colonel Smoak’s Marines was paid for in heavy casualties, and every man available was needed in the assault to maintain the impetus of the advance. When the 2nd Battalion dug in just short of the Mt. Tenjo Road about 1730, all units were fully committed to hold a 1,000-yard front. There was no reserve.

Like 2/21, the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines ended its fifth day of battle with all companies manning frontline positions. The trace of the 1,200 yards of foxholes and machine gun emplacements held by 1/21 ran roughly parallel to the Mt. Tenjo Road where it looped south from Fonte to Mt. Mangan. Despite an all-out effort on the 25th, which saw assault elements reach and cross the all-important road at many points, the Marines were not able to hold most of their gains in the face of heavy and accurate enemy fire. In the morning, the attacking units were stopped and then driven back by the enfilade fire of Japanese artillery, well hidden in the brush and irregular terrain at the head of the Fonte River valley. In the afternoon, when tank support was available for the first time, some hill strongpoints were taken in the center of the line near a quarry which was a focal point of Japanese resistance.

The freshly arrived tanks, a welcome sight to the men of 1/21, reached the heights by means of a steep and twisting supply trail, which engineers had constructed through the draw that had been cleared by Company E of 2/21 that morning. Company B of the 3rd Tank Battalion reported to Lieutenant Colonel Williams’ CP at 1615, and he immediately set one platoon of Shermans to work hammering enemy defenses in the quarry area. A second platoon of the mediums spearheaded a limited objective attack on Mt. Mangan, which was recognized as the launching point for many of the Japanese night counterattacks that had plagued the 21st Marines. When the tanks swung behind the hill, a tremendous outpouring of fire from the reverse slope cut down most of the accompanying infantry. The tanks answered with cannon and machine guns, closing in on the Japanese positions to fire point blank on any targets that showed. When the Shermans returned to the Marine lines, the tank commanders were sure that they had hurt the enemy badly—and they had. Only about 40 men were left of the 321st Independent Infantry Battalion, which had attempted to defend Mt. Mangan. Many of the luckless survivors of the 38th Regiment, that had assembled at Mangan to take part in the counterattack, were also killed.

The enemy casualties inflicted by this

tank thrust into the heart of the Japanese defensive complex may well have altered the course of action later that night, for the Japanese were not strong enough to exploit limited penetrations in the 1/21 sector. The Marines holding positions opposite Mt. Mangan were too few in number to form a continuous defensive line. Instead, strongpoints were held—natural terrain features that lent strength to the fire of Marine small arms. Gaps between squad and platoon positions were covered by infantry supporting weapons, and artillery and naval guns were registered on possible enemy assembly areas and routes of approach.

Along the boundary between 1/21 and 3/21 a considerable interval developed during the day because the 1st Battalion was held up by enemy fire, and the 3rd Battalion was able to move out to its objective within an hour after the regimental attack started at 0700. In contrast to the rest of the 21st Marines, 3/21 encountered no strong resistance on 25 July. All day long, however, sporadic fire from enemy mortars and machine guns peppered the battalion positions. Patrols scouring the hills in the immediate vicinity of the front line were also fired upon, but in general the Japanese hung back from close contact.

Despite the relative lack of opposition, Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis’ situation was precarious, because he had only two companies to hold 800 yards of terrain that seemed to be nothing but ravines and ridges smothered in dense vegetation. Not only was there a gap between 1/21 and 3/21, there was also an 800-yard open stretch between the right flank of the 21st Marines and the left of the 9th Marines, which had pushed forward well beyond the 21st during the day. Just before dark, Colonel Butler, in an effort to ease the situation on his right flank, released his only reserve, Company L, to Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis. The 3/21 commander placed this company in positions that filled a weak spot in the center of his line and enabled the companies on either flank to tighten up their defenses. As a site for his command post, Duplantis chose the reverse slope of a 460-foot hill which stood squarely on the regimental boundary and in the path of any enemy attempt to exploit the yawning space between the 21st and 9th Marines.5

Colonel Craig’s regiment made rapid progress on the 25th from the time the two assault battalions jumped off at 0700. By 0845, the regiment was on its day’s objective, a line running generally along the course of the Sasa River. At 0915, the division ordered the attack to continue with the aim of seizing the high ground on the north bank of the Aguada River. The Marines encountered very few Japanese and moved out almost as fast as the rugged terrain would permit. In the hills on the extreme left flank, an outpost of 1/9 reported clashing with small groups of the enemy during the day, but the overall intelligence picture in the 9th Marines zone indicated that few Japanese were present. Under the circumstances, Colonel Craig thought that his regiment could have advanced easily and made contact with

the brigade “at any time,”6 but considered that such a move would have served no useful purpose. By limiting the advance on the division right to a front that could be held by two battalions, General Turnage was able to draw on the 9th Marines for reserves to use in the hard fighting on the left and center of the beachhead.

As night fell, the troublesome gap between 3/21 and 1/9 was partially blocked by small Marine outposts. Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis organized his CP defenses in a small depression on the left rear of Hill 460 and set out a blocking force armed with BARs and bazookas to guard a trail that skirted the hill on the right and led toward the beaches. A 25-man detachment of the 3rd Division Reconnaissance Company held a strongpoint in the midst of the 500-yard open stretch between the hill and the shoulder of the ridge defended by the left flank company of the 9th Marines. The reconnaissance unit, composed of elements of two platoons, had been attached to the 9th since W-Day for the express purpose of maintaining contact between regiments, but on the night of 25-26 July it was simply too weak for the task at hand.

The start of the Japanese counterattack was heralded at 2330 by an artillery forward observer’s report that enemy activity was developing in the gap between the 9th and 21st Marines. Very shortly after midnight, the 3rd Marines called for artillery and naval gunfire support to silence enemy artillery, mortars, and machine guns that were hitting the left flank. Soon units all across the center and left of the beachhead perimeter were reporting Japanese probing attacks and patrol action close to the Marine lines. Darkness turned to half-light as flares went up all along the front to help spot the Japanese. Cruisers and destroyers increased their rate of fire of 5-inch star shell and followed with 5- and 6-inch high explosive at the call of shore fire control parties. To aid local defenses, 60-mm mortars of the rifle companies kept flares overhead wherever the front line was threatened.

The first serious assault on American positions was launched against the isolated Reconnaissance Company outpost. An enemy group, estimated at 50 men, attacked the Marine unit shortly after midnight, and during a brief, hot firefight killed four men and wounded five, over one-third of the American strength. Convinced that his position was untenable in the face of another attack by a superior enemy force that could hit from any direction, the Reconnaissance Company commander withdrew his men to the lines of Company B of 1/9, which held the left flank of the 9th Marines.7

Japanese troops that drove in the reconnaissance outpost were men of the 3rd Battalion, 18th Infantry. The enemy unit was assigned an objective of penetrating the Marine lines in the area held by 3/21. Surprisingly, instead of

pouring full strength through the hole that had been left open, most elements of 3/18 continued to feel out the main defenses of Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis’ battalion. Despite their superior observation of the American beachhead from positions on the Chachao–Alutom–Tenjo massif,8 and the information supplied by their patrols, the Japanese did not really make use of their best opportunity for success.

The pressure of enemy units testing the Marine defenses along the rest of the division front increased as the long night wore on. Both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 21st Marines were hit repeatedly and in gradually increasing strength. Apparently, the 2nd Battalion, 18th Infantry and the elements of the 48th Brigade in the Mt. Mangan area were looking for a weak spot that would let them break through to the Asan River draws. The draws in turn would provide a path to the division rear areas. On the Fonte front, most of the Japanese troops pressing 2/9 were part of the 2nd Battalion, 10th IMR; almost all of the 3rd Battalion had been killed during the fighting on the 25th, as had the commander of 2/10. The remainder of the Marine line on the left flank was harried by other elements of the 48th IMB and by naval troops of the 54th Keibitai. Throughout the Japanese ranks, the infantry was bolstered by service and support troops, by walking wounded that could still handle a weapon, and, in short, by everyone that could be mustered for the assault.

One important aspect of the Japanese counterattack plans went awry in the darkness—enemy tanks never reached the battle line. When night fell, the armored vehicles rumbled from their hiding places near Ordot and headed onto the trails leading to Agana. Inexplicably, the tanks got lost. Unable to find their way to the designated assembly area, the commanders of the 2nd Company, 9th Tank Regiment and the 29th Tank Company led their units back to the Ordot area before dawn broke. Hidden again at daylight from the eyes of American artillery and air observers, the Japanese tanks bided their time for a more effective role in the fighting.

Undaunted by the absence of expected armored support, the 54th Keibitai moved forward to attack in the early hours of 26 July. An intensive preparation fired by mortars and artillery crashed down on the positions occupied by 3/3 and 2/3. Led by the senior enemy naval officer, Captain Yutaka Sugimoto, the Japanese sailors launched the first of what proved to be a series of counterattacks. From Adelup Point and Chonito Cliff, Marine small arms fire crackled forth from well-dug-in foxholes and machine gun emplacements. Shells from company and battalion mortars exploded amidst those from the 105-mm Howitzers of 3/12, and drove the onrushing enemy back. Captain Sugimoto was killed in the first outburst of defensive fire; later, his executive officer was felled by a shell burst. Despite repeated attempts to break through the

Marine lines, the Japanese were unsuccessful and most of the attackers were dead by early morning. As day broke, the weary survivors, many of them wounded, fell back toward the low hills west of Agana.

One of the night’s most bitter struggles was waged on Fonte Plateau, where Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s embattled battalion strove to hold its gains of the 25th. Local counterattacks flared all along the front of 2/9 and caused a constant drain of Marine casualties. At 2200, it was necessary to pull Company F back 50 yards from its salient in the center of the line in order to consolidate defenses. Because there was little letup in the pressure that the 10th Independent Mixed Regiment applied, the expenditure of ammunition by all types of Marine weapons mounted alarmingly. Seven major counterattacks in succession ate away at the American line, but it held, often only by the slimmest of margins. The height of the battle was reached in the early morning hours when the Japanese seemed to come in unending waves and the din of weapons firing all at once mixed with the screams and yells of men caught up in the frenzy of close-quarter combat.

As “the first faint outline of dawn showed,” and “ammunition ran dangerously low”9 in the American positions, Marine tanks were able to play a significant role in the hard-fought battle. The platoon of Shermans that had spent the night behind the lines now moved to the front, where their cannon and machine guns helped break up the last desperate enemy thrust. Soon afterwards, another platoon of tanks escorting trucks loaded with ammunition passed through the lines of 3/3 and made its way up the road to Fonte Plateau. While the armor provided covering fire, riflemen and machine gunners grabbed belts and bandoleers of .30 caliber cartridges and mortar crews quickly stacked live rounds near their shell-littered firing sites. With tank support and adequate reserve ammunition, the Marines of 2/9 were solidly established and ready for renewed enemy attacks. Without the shield of darkness, the Japanese held off, however, for only about 100 men of the 10th IMR had survived the night’s fighting.

Not all of the Japanese that died on the night of 25-26 July were killed in front of the American lines. Some infiltrated through the widely spaced strongpoints of the 21st Marines and others found their way through the gap between 3/21 and 1/9. The positions manned by 1/21 and 2/21 lay generally along a low ridge that paralleled and ran north of the Mt. Tenjo Road. From this rise the ground sloped back several hundred yards to the edge of the cliffs. Over much of this area Marines waged a fierce, see-saw battle to contain enemy units that had broken through. In the thick of the fight was Company B of the 3rd Tank Battalion, which was bivouacked behind the lines of the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines. Although the tanks were cut off for a time from Marine infantry support, they were able to fend for themselves with their machine guns and 75s. Apparently the Japanese infiltrators were more interested in other and easier targets, for only one tank, which had a track blown and its engine damaged,

was put out of action during the night’s combat.

The coming of daylight brought a quick end to the limited Japanese penetration of the lines of 1/21. Fire from 60-mm mortars sealed off the area where the enemy had broken through and ripped apart the groups of Japanese that tried to make a stand. Supported by tank fire, the Marines of Lieutenant Colonel Williams’ battalion, reinforced by a company of engineers, counterattacked to restore their lines.10 Infiltrators were hunted down relentlessly, and by 0800, the enemy had been cleared from the entire area between the edge of the cliffs and the original front line of 25 July. Along this segment of the embattled 3rd Division front, the weary Marines could relax a bit and feel, as one did, that “the fireworks were over.”11

Although the fighting on the heights had subsided by early morning, the conflict was far from settled in the division rear areas, particularly in the vicinity of the wooded draws that held the Nidual River and the west branch of the Asan. Most Japanese that found their way through the gap between 3/21 and 1/9, or infiltrated the fire-swept openings in the Marine front line ended up following these natural terrain corridors toward the sea. Directly in the path of the majority of these enemy troops, the elements of 3/18 that had skirted the right flank of 3/21, was Hill 460 and Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis’ command post.

After feeling out the positions held by 3/21, the Japanese attacked in force about 0400 all along the battalion front and drove in a platoon outpost of Company K, which held the right of the line. The intensity and strength of the enemy assault mounted as dawn approached, and the Marines on the front line had all they could do to hold off the attackers. Consequently, Duplantis believed that he could not call on his rifle companies for help when the Japanese began attacking his command post. In fact, a reinforced rifle squad, the only reserve available to the commander of 3/21, was committed soon after the Japanese attacked to defend the area between the ridge positions of Company K and Hill 460. Like the Marines that held the trail block Duplantis had set out earlier that night, the outnumbered squad “went down fighting to a man,”12 overwhelmed by the enemy troops, who swept around both sides of the hill.

Perhaps nowhere else within the Marine perimeter was the situation so desperate as it was in the 3/21 CP as daylight approached. In most parts of the 3rd Division beachhead, dawn gave the Marines a better chance to wipe out the infiltrators; on Hill 460, in contrast, the increasing light furnished the

Shermans and riflemen of the 1st Brigade advance together on Orote Peninsula. (USMC 88152)

Firing line of 3rd Division riflemen engage the enemy in the hills above Asan. (USMC 88090)

Japanese better targets. From positions on the crest of the hill, enemy machine guns raked the rear of Company K and small arms and knee mortar fire poured down on the CP, less than 75 yards away. The deadly hail that swept Duplantis’ position took a heavy toll among the corpsmen and communicators, who made up a large part of the defending force. The headquarters group fought doggedly, keeping up a steady fire against the Japanese, who showed no disposition to charge the beleaguered Marines.

The task of eliminating the troublesome enemy strongpoint on Hill 460 fell to the 9th Marines. At 0655, a time when most of the division reserve and support forces were hotly engaged with infiltrators, General Turnage ordered Colonel Craig to shorten his front lines and pull back to the Sasa River and to send troops to recapture Hill 460. Craig, in turn, detailed his regimental reserve, Company L, to take the hill and assigned an officer familiar with the terrain as the temporary commander. Led by Major Harold C. Boehm, executive officer of 1/9, the men of Company L advanced toward the hill along the course of the Masso River. The approach march over difficult terrain was time-consuming, but the Japanese on 460 did not spot Boehm’s command until the Marines were about 250 yards away and ready to attack. Aided by covering machine gun fire from Company B, 1/9, shortly before noon Company L launched an assault that carried the enemy position. Twenty-three Japanese were killed on the hill and the remainder were driven toward a firing line set up by Company K of 3/21. The few enemy that survived the attack fled down the Nidual River draw to annihilation at the hands of the Marine units then mopping up the rear areas.

The clash at Hill 460 was one of a series of hard-fought actions that took place behind the 3rd Division front. Japanese infiltrators moving down the stream lines leading to the beaches continually harassed the perimeters of Marine units that stood in their paths. Throughout the night, gunners in artillery and mortar positions had to interrupt their supporting fires to beat off troops.13 The neighboring command posts of the 12th Marines and of 3/12 were beset by snipers, who had infested the high ground above the camp areas. By midmorning, artillerymen acting as infantry, aided by two Shermans from the division tank park nearby, had destroyed this nest of enemy.

One of the most serious encounters behind the lines took place at the division hospital. At 0600, about 50-70 enemy troops opened fire on the hospital tents from the high ground on the west bank of the Nidual River. Doctors and corpsmen immediately began evacuating patients to the beach while other hospital personnel and 41 of the walking wounded formed a defensive line and returned the Japanese fire. As soon as word reached General Turnage that the hospital was being attacked, he ordered the division reserve commander, Lieutenant Colonel George O. Van Orden (Division Infantry

Training Officer), to take two companies of pioneers and eliminate the threat.

Moving quickly, Van Orden’s command reached the hospital area and joined the battle. After three hours of fighting, during which the enemy force was eventually surrounded, the pioneers killed 33 Japanese at a cost of three of their own men killed and one wounded. The 3rd Medical Battalion had 20 of its men wounded, including two that later died of wounds, but only one patient was hit and he was one of the volunteer defenders. By noon, the hospital was back in operation, caring for the heavy influx of casualties from all parts of the Marine beachhead.

Even before the fighting was over at the hospital and at Hill 460, it was apparent that these two areas held the only sizeable enemy groups left within the perimeter. Any other Japanese still alive behind the lines were the subject of intensive searches by combat patrols of service and support troops. Along the front line, infantry units, often with tank support, scoured the woods and caves in their immediate areas to flush enemy stragglers. The mop-up and consolidation of defensive positions continued through the afternoon as Marine commanders made certain that their men were ready to face whatever the night might bring. While he was inspecting these defensive preparations, Lieutenant Colonel de Zayas, commanding 2/3, was shot and killed; the battalion executive officer, Major William A. Culpepper, immediately took command and continued the defensive buildup.

Conservative intelligence estimates indicated that the Japanese had lost close to 3,200 men, including 300 behind Marine lines, in the counterattack.14 The comparable casualty total for the 3rd Division and its attached units was approximately 600 men killed, wounded, and missing in action.15 It appeared to General Turnage that the enemy was still capable of mounting another strong counterattack, and he directed that all units establish the strongest possible night defense.

Early on the 26th, General Turnage had requested reinforcements from the corps reserve, and during the afternoon, General Geiger dispatched one battalion of the reserve, 3/307, overland to the Piti area to be available immediately in case of need. On its arrival the Army unit was attached to the 9th Marines. As a further safeguard, Turnage directed the organization under Lieutenant Colonel Van Orden of a provisional division reserve composed of 1/3, a platoon of tanks, and elements of eight Marine and Seabee support battalions. Most of these units spent the night of 26-27 July manning defensive perimeters or standing by for employment as infantry reinforcements.

Actually, the Japanese commanders

had no further massive counterattack in mind. To an extent not yet realized by American intelligence officers, the fruitless assault had broken the backbone of Japanese resistance on Guam. While there was no disposition to stop fighting on the part of the remnants of the 29th Division, the ground within, in front of, and behind the Marine lines was littered with the bodies of the men and with the weapons, ammunition, and equipment that General Takashina sorely needed to prolong the battle. Undoubtedly the most damaging losses were those among senior combat unit leaders, whose inspirational example was essential to effective operations in the face of obvious and overwhelming American superiority in men and material. General Shigematsu, the 4th Brigade commander, was killed on 26 July when tanks supporting the consolidation of Marine frontline positions blasted his CP on Mt. Mangan. The regimental commander of the 18th Infantry was cut down in the forefront of his counterattacking troops, and both of the battalion commanders were killed after having led their men through the Marine lines. The body of one was discovered in the Asan River draw; the other was found in the Nidual River area.16

As the senior Japanese officer on Guam, General Obata had the unpleasant duty of reporting the failure of the counterattack to Tokyo. At about 0800 on the 26th, the Thirty-first Army commander radioed Imperial General Headquarters, stating:–

On the night of the 25th, the army, with its entire force, launched the general attack from Fonte and Mt. Mangan toward Adelup Point. Commanding officers and all officers and men boldly charged the enemy. The fighting continued until dawn but our force failed to achieve the desired objectives, losing more than 80 percent of the personnel, for which I sincerely apologize. I will defend Mt. Mangan to the last by assembling the remaining strength. I feel deeply sympathetic for the officers and men who fell in action and their bereaved families.17

The following day Tokyo acknowledged Obata’s message and commended the general and his men for their sacrifice, emphasizing that the continued defense of Guam was “a matter of urgency for the defense of Japan.”18 After this, Generals Obata and Takashina and the few surviving members of their staffs concluded that their only practical course of action was to wage a campaign of attrition, whose sole purpose would be, in the words of Lieutenant Colonel Takeda, “to inflict losses on the American forces in the interior of the island.” The 29th Division operations officer explained the factors influencing this decision as:–

1. The loss of commanders in the counterattack of 25 July, when up to 95% of the officers (commissioned officers) of the sector defense forces died.

2. The personnel of each counterattacking unit were greatly decreased, and companies were reduced to several men.

3. The large casualties caused a great drop in the morale of the survivors.

4. Over 90% of the weapons were destroyed and combat ability greatly decreased.

5. The rear echelons of the American forces on Agat front landed in successive waves and advanced. There was little strength remaining on that front and the strength for counterattacks became nonexistent.

6. The Orote Peninsula defense force perished entirely.

7. There was no expectation of support from Japanese naval and air forces outside the island.19

Part of the Japanese estimate of the situation was based on a lack of knowledge of the exact situation on Orote. All communication with the Japanese command on the peninsula was lost by the evening of 25 July, but the last messages received indicated that the defenders were going to take part in the general counterattack.20

Capture of Orote Peninsula21

Commander Asaichi Tamai of the 263rd Air Group was the senior officer remaining in the Agat defense sector after W-Day. The death of Colonel Suenaga elevated Tamai, who had been charged with the defense of Orote Peninsula, to the command of all sector defense forces, including the 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry. During the period 22-25 July, the Army unit fell back toward Orote, fighting a successful delaying action against the 22nd Marines.

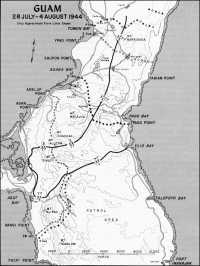

When the 1st Brigade closed off the neck of the peninsula on 25 July, it sealed the fate of some 2,500 Japanese soldiers and sailors who were determined to die fighting in its defense. Although more than half of Commander Tamai’s troops were lightly armed and hastily trained aviation ground crewmen and engineers, he had a strong leavening of experienced ground defense units of the 54th Keibitai. Even if many of the Japanese were not trained in infantry tactics, they were apparently experts in the use of pick and shovel and well able to man the fixed defenses, which they had helped build. Their handiwork, a formidable belt of field fortifications, stretched across the peninsula just beyond the marsh and swamp area and generally along the O-3 Line, the initial brigade objective in its attack on 26 July. (See Map 28.)

Before the men of the 1st Brigade could test these hidden defenses—whose presence was suspected but not yet confirmed—they had to deal with the Japanese troops that took part in the general counterattack ordered by the 29th Division. In contrast, the counterattack on the brigade defenses was made by about 500 men and the action was concentrated in a narrow sector near the regimental boundary. The left flank unit of the 22nd Marines, Company L, bore the brunt of the Japanese thrust, helped by the withering fire of the right flank platoon of the 4th Marines from Company A.

The assembly area for the Japanese attack force, principally men of 2/38, was the mangrove swamp in front of the 22nd Marines. In apparent preparation for the assault, sake was passed about freely, and the Marines manning forward foxholes could plainly hear the

resulting riotous clamor as the Japanese worked themselves up to fever pitch. Finally, just before midnight, a tumultuous banzai charge erupted out of the swamp as a disorganized crowd of yelling, screaming men attacked the positions held by Company L. The resulting carnage was almost unbelievable, as artillery forward observers called down the fire of brigade, 77th Division, and III Corps artillery on the surging enemy troops. At one point, the shells of pack howitzers of the 22nd Marines were brought to within 35 yards of the front lines in order to check the Japanese.22 The few scattered groups that won their way through the barrier of exploding shells criss-crossed by machine gun fire were killed in frenzied hand-to-hand fighting with Marines of Company L. By 0200, the action died down, and all supporting weapons resumed normal fires for the night defense.

Daylight revealed a gruesome scene, for the mangled remains of over 400 enemy dead lay sprawled in front of the Marine lines in the impact area where over 26,000 artillery shells had fallen during the counterattack. Marine casualties in Company L were light, despite the close-quarter combat, and the flanking platoon of the 4th Marines did not lose a man, although it counted 256 Japanese bodies in the vicinity of its position. Any information that might reveal the exact cost of the counterattack to the Japanese, who evacuated their wounded during the night, was buried with the Orote garrison. There was no doubt, however, that 2/38 ceased to exist as an effective fighting force. Save for small groups of soldiers that continued to fight on, enemy naval troops now had the main responsibility for the defense of Orote.

The night’s counterattack had no effect on General Shepherd’s attack plan for 26 July. A thorough air, naval gunfire, and artillery preparation exploded on enemy-held areas, and at 0700, the 4th Marines moved out in a column of battalions, 1st in the lead, supported by the regimental tank company. On the right of the brigade front, the assault elements of 3/22 and 2/22 were heavily shelled as they were preparing to jump off. The Marines were convinced that their own supporting ships and artillery were off target, although subsequent investigation indicated that Japanese artillery was again taking advantage of American preparatory fires to strike some telling blows without detection. Regardless of its source, the effect of the fire was demoralizing to the 22nd Marines, and it was 0815 before the assault units were reorganized and ready to move out.

The delay in the attack of the 22nd Marines opened a gap between the regiments, which was bridged by Company L of 3/4. Another 3rd Battalion company, I, followed in trace of the swiftly advancing tank-infantry spearheads of 1/4 to mop up any bypassed enemy. Major Green’s 1st Battalion met only light resistance until it approached the O-3 Line, where heavy brush on the left and the threat of enemy fire ripping across the more open ground on the right slowed the advance. Anxious to maintain the impetus of the attack and to make more

Map 28: Capture of Orote Peninsula, 25-30 July 1944

effective use of the comparatively fresh units of the 4th Marines, General Shepherd at 1145 ordered a change of regimental boundary that would enable Lieutenant Colonel Shapley to employ all his battalions in assault. All terrain east of the road from RJ 15 to Sumay went to the 22nd Marines, while the 4th Marines took responsibility for the wider zone to the west.

Initial resistance to the 22nd Marines, once its attack was launched, was slight, and 2/22 patrols, wading deep into the mangrove swamp, encountered only snipers. Along the Sumay Road, where there was room to maneuver and firm ground to support their weight, the regimental tanks moved out with 3/22. At 1220, the 3rd Battalion reached RJ 15 and discovered that the Japanese had planted an extensive field of aerial bomb-mines across the 200-yard corridor between the swamp and a wide marsh lying west of the road junction. Unable to advance further, the Shermans set up a firing line along the high ground that overlooked the junction and the minefield beyond.

The mined area was covered by a nest of Japanese machine guns, which the assault infantry did not discover until a sudden outburst of automatic weapons fire pinned the lead platoon down in the midst of the mines. Spotting the Japanese strongpoint, a cluster of brush-covered bunkers northwest of the road junction, the tanks fired low over the heads of the ground-hugging infantry to hit gun ports and disrupt the enemy fire. When Japanese mortars opened up from defilade positions behind the bunkers, the tank company commander called down high-angle artillery fire to silence them, which also set afire an ammunition and a supply dump in the area. With the aid of the tanks, the Marines of 3/22 were able to pull back to relative safety, but too late in the day for any further attempt to force the minefield.

On the left of the brigade line, tanks also played a prominent part in the afternoon’s advance. The 4th Marines, maneuvering to get three battalions on line, began to move into heavy vegetation as forward elements approached the O-3 Line. The Shermans broke paths for accompanying infantry where the going was toughest and helped beat down the scattered opposition encountered. In midafternoon, heavy enemy machine gun and mortar fire hit 2/4 as it was moving into the center of the regimental front. Shortly thereafter, leading elements of the 1st Battalion were raked by intense fire from enemy positions in the dense undergrowth ahead. Japanese gunners had a clear shot at the Marines along well-prepared fire lanes cut through low-hanging branches and thick ground cover, often before the Americans were aware that they were exposed. It was readily apparent that an extensive and gun-studded belt of Japanese defenses had been encountered. At 1730, when brigade passed the order to dig in, both regiments consolidated their positions along O-3 except on the right, where the 22nd Marines set up in the swamp, refusing its flank and covering the resulting gap with artillery and mortar fire.

After a quiet night with no unusual enemy activity, the brigade attacked in the wake of an extensive air, naval gunfire, and artillery preparation. Neither this fire nor the night-long

program of harassment and interdiction by American supporting weapons seemed to have much effect on the dug-in Japanese. The 4th Marines had as its attack objective an unimproved trail, about 700 yards forward of O-3, that stretched completely across the regimental zone. Except along the Sumay Road, the intervening ground was covered with a thick tangle of thorny brush, which effectively concealed a host of mutually supporting enemy pillboxes, trenches, and bunkers well supplied with machine guns, mortars, and artillery pieces.

In the narrow corridor forward of RJ 15, 3/4 faced a low ridge beyond the marsh area, then a grass-choked grove of coconut palms, and beyond that another ridge, which concealed the ground sloping toward the old Marine Barracks rifle range and the airfield. On the 22nd Marines side of the Sumay Road, the mangrove swamp effectively limited maneuver room beyond RJ 15 to an open area about 50 yards wide.

The terrain and the enemy dispositions gave special effect to the attack of Major Hoyler’s battalion. With Companies I and L in the lead, and a platoon of tanks moving right along with the assault troops, 3/4 broke through the enemy defenses along the first low ridge to its front during a morning of heavy and costly fighting. The tank 75s played the major role in blasting apart the Japanese gun positions. During the afternoon, the tank-infantry teams made their way through the coconut palms at a stiff price to the unprotected riflemen. By the time 3/4 had seized and consolidated a secure position on its objective, Company L alone had suffered 70 casualties.

On the far left of Lieutenant Colonel Shapley’s zone, the enemy resistance was lighter than that encountered by 3/4, and the 1st Battalion was on its part of the objective by 1100. Led by path-making tanks, the 2nd Battalion reached the trail about a half hour later. Both units then set up defenses and waited for the 3rd Battalion to fight its way up on the right. At about 1500, while he was inspecting dispositions in the 1/4 area, the regimental executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel D. Puller, was killed by a sniper.

Shortly after this, when tanks supporting Hoyler’s battalion ran out of ammunition, Shermans from the platoons that had advanced with the left and center of the Marine line moved over to cover 3/4 while it was digging in. From firing positions ahead of the infantry, these tanks spotted a company of Japanese moving in the open along a road atop a ridge some 300 yards away. Cannon and machine gun fire tore apart the enemy column and scattered the luckless troops. At 1830, their job well done for the day, the tanks returned to their bivouac for maintenance and replenishment.

Armor also played a significant role in the day’s action on the 22nd Marines front. Supporting tank fire helped Company G, leading the regimental assault in the narrow zone between swamp and road, to thread its way through the minefield that had held up the advance on the 26th. Under cover of smoke shells fired by the Shermans, the regimental bomb disposal officer disarmed enough mines to clear a path

through the field for the tanks to move up with the lead riflemen. Engineers then cleared the rest of the mines while 2/22 continued its advance, meeting the same type of determined opposition that had slowed 3/4 on its left. Fire from the barrier of Japanese positions, which confronted the brigade all across the peninsula, took a heavy toll of Marines, particularly unit leaders. Three of the four company commanders were hit during the day’s fighting as was the new battalion commander, Major John F. Schoettel.23

At 1415, after 2/22 had won some maneuver room east of the road to Sumay, the 3rd Battalion moved up on the right to join the battle. Since much of the zone assigned 3/22 was swamp, there was only room for Company L in assault. This company tried unsuccessfully to outflank the enemy defenses by moving along the coast, but was stopped by vicious automatic weapons fire. Despite the determined Japanese defense, the 22nd Marines kept inching ahead, utilizing tanks to blast bunker firing ports so that accompanying infantry could move in with flamethrowers and demolitions.

At 1700, the brigade ordered the 22nd to dig in on commanding ground for the night. In an effort to seize the most defensible terrain, Colonel Schneider stepped up his attack, calling for increased artillery support and for carrier air to bomb and strafe the Japanese. The response was prompt, sustained, and effective. The wing guns of the attacking aircraft sprayed enemy defenses close enough to the American lines for 2/22 to report it as “too close” for safety at 1802, and thankfully as causing “no casualties, but plenty close” at 1810 when the planes drew off.24 Whatever the precipitating cause—bombing, strafing, artillery fire, or steady unrelenting tank-infantry pressure—about 1835 the enemy troops confronting the 22nd Marines suddenly bolted from their defenses and ran. Taking swift advantage of the unusual Japanese action, a rout almost unprecedented in Pacific fighting, the Marines surged forward close on the heels of the fleeing enemy.

The approach of darkness stopped the attack as the 22nd Marines reached high ground overlooking the Marine Barracks area. The precipitate advance opened a 500-yard gap between 2/22 and 3/4, which Company C of 1/22 closed. Two men of the company were killed and 18 wounded in a flurry of Japanese mortar fire that struck the Marine unit as it set up defenses in the flare-spotted darkness. The remainder of the 1st Battalion, which had moved from Atantano to reserve positions near RJ 15 during late afternoon, was alerted to back up Company C. There was no further significant enemy reaction, however, anywhere along the front that night.

The preparation for the brigade attack on the 28th included 45 minutes of air strikes, 30 minutes of naval gunfire, and a final 30 minutes of artillery fire. Perhaps as a result, when the 22nd Marines attacked at 0830, the regiment swept forward against little opposition.

At 1005, Colonel Schneider reported his troops had reached the O-4 Line, and General Shepherd ordered the advance to continue, “echeloning units to the left rear as necessary to maintain contact with the 4th Marines.”25 Major Schoettel’s battalion concentrated its drive on the capture of the Marine Barracks area, while Lieutenant Colonel Shisler’s 3rd Battalion entered the battered ruins of Sumay. Tanks supported the assault troops of both battalions, but found the litter and rubble in Sumay so mine-strewn that support had to be confined to overhead fire until engineers could clear the streets. Before the armor halted, one Sherman and its crew were completely destroyed when it hit a 1,000-pound bomb-mine. In the face of desultory opposition, the 22nd Marines was able to seize the barracks ruins, the whole of Sumay, and the cliffs along the harbor shore before dusk. For stronger night defense, 3/22 pulled back to high ground east of the town and dug in at 1750.

In contrast with their weak defense on the 22nd Marines front, the Japanese facing the 4th Marines were ready and able to make the Americans pay dearly for every foot of ground they won. The enemy defenses were arrayed in depth, along a 300-yard stretch of ridgeline guarding the approaches to the rifle range and airfield. Beneath the thorn bushes and other varieties of densely-clustered jungle growth lay almost 250 emplacements and bunkers, many of them strong pillboxes constructed of coconut logs, cement, and earth. Minefields were cleverly hidden amidst the brush along all approaches to the enemy positions.

Both 2/4 and 3/4 had run up against the outskirts of this defensive complex in the previous day’s fighting. The difficulties imposed by the terrain and the pattern of Japanese defending fires and minefield prevented the Marines from outflanking the enemy position, and left Lieutenant Colonel Shapley no choice but to order a frontal assault. The extensive preparatory fires for the attack on 28 July appeared to have made no impression on the Japanese; there was no letup in the volume of enemy fire. When the regiment advanced, a slugging match ensued in which Companies E and I spearheaded the determined assault. Throughout the morning and early afternoon, riflemen working closely with tanks gradually forced their way into the nest of enemy emplacements. At 1545, about 20-30 Japanese charged out of the remaining key strongpoint in a futile attempt to drive the Marines back; every attacker was quickly killed. Shortly thereafter, in an attack that General Shepherd had personally ordered during a visit to the front lines, two platoons of Marine mediums and a platoon of Army light tanks led a 4th Marines advance that smashed the last vestiges of the Japanese defenses and swept forward to positions just short of the rifle range. Tied in solidly with the 22nd Marines at the Sumay Road by nightfall, the regiment was ready to carry out the brigade commander’s order to seize the rest of the peninsula on the 29th.

Assigned missions for the attack on 29 July gave the 22nd Marines responsibility for cleaning the Japanese out of

the barracks area, the town of Sumay, and the cliff caves along the coast. The prime objective of the 4th Marines was Orote airfield. To make sure that the attack would succeed, Shepherd arranged for a preparation that included the fires of eight cruisers and destroyers, six battalions of artillery (including one from the 12th Marines), and the heaviest air strikes since W-Day. To increase direct fire support for the infantry, the Marine commander asked General Bruce for another platoon of Army tanks, which would work with the one already assigned to the brigade, and for a platoon of tank destroyers as well.

When the brigade attacked at 0800, following a thunderous and extended preparation, there were few Japanese left to contest the advance. By 1000, General Shepherd was reporting to General Geiger: “We have crossed our O-5 Line and are now rapidly advancing up the airstrip meeting meager resistance.”26 An hour later, Shepherd ordered the 22nd Marines to hold up its attack at the O-6 Line and directed the 4th Marines to take over there and capture the rest of the peninsula.

In moving toward O-6, the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines encountered and handily overcame resistance from a strongpoint located near the ruins of the airfield control tower. This proved to be the only significant opposition that developed during the day. The relief of the 22nd Marines on O-6 took place without incident at 1500; and Lieutenant Colonel Shapley held up his advance about 500 yards beyond this objective line. At 1600, while the infantry dug in, two platoons of riflemen mounted the regimental tanks and a reinforcing platoon of Army lights and made a combat reconnaissance to Orote Point. Only two Japanese were sighted and they were killed. When the tank-infantry patrol reported back, General Shepherd declared the peninsula secured.

Earlier on the 29th, at 1530, a ceremony took place at the ruins of the Marine Barracks that had special significance to all Americans on the island and on the waters offshore. To the accompaniment of “To the Colors” blown on a captured Japanese bugle, the American flag was officially raised on Guam for the first time since 10 December 1941.27 Present to witness this historic event were Admiral Spruance and General Holland Smith, ashore on an inspection trip, and Generals Geiger, Larsen, and Shepherd as well as the brigade regimental commanders and those few officers and men that could be spared from the fighting still going on. Fitting honors for the occasion were rendered by a platoon of

the men that had repossessed the barracks for the Marine Corps. In a brief address, General Shepherd caught the spirit of the event, saying:–

On this hallowed ground, you officers and men of the First Marine Brigade have avenged the loss of our comrades who were overcome by a numerically superior enemy three days after Pearl Harbor. Under our flag this island again stands ready to fulfill its destiny as an American fortress in the Pacific.28

Last-gasp resistance by the scattered enemy survivors was confined to sniping and bitter-end defense of caves and dugout hideaways, principally in the cliffs that bordered Apra Harbor. Many Japanese committed suicide when American troops approached; others tried to escape the peninsula by swimming to the low-lying ruins of Ft. Santa Cruz in the middle of harbor.29 The swimmers were shot, captured, or turned back by a watchdog platoon of LVT(A)s. On the opposite side of the peninsula, Neye Island, long a source of galling enemy fire, was scouted by an LVT-borne patrol of the 9th Defense Battalion and found deserted. Brigade intelligence officers conservatively estimated that at least 1,633 enemy troops had been killed on Orote by 30 July. The cost of those deaths to the brigade was 115 Marines killed, 721 wounded, and 38 missing in action.

The end of the battle for possession of the peninsula coincided with a realignment of the IIIAC battle line. While the brigade had been clearing the Japanese from Orote, the 3rd Division had fought its way to complete control of the Fonte heights, and the 77th Division had patrolled all of southern Guam looking for enemy troops. While the two divisions prepared to drive north in line abreast and wipe out the remaining Japanese, the brigade was to take an active role in reserve, guarding the corps rear area, mopping up the peninsula, and hunting down enemy stragglers in the southern mountains.

Nothing signified the change of ownership of Orote Peninsula better than the landing on its airfield of a Navy TBF from the Chenango on 30 July. Touching down first to test the surface of a 2,000-foot-long strip cleared by six hours of feverish engineer activity, the plane circled and came down again at 1650.30 Once the field proved ready, the escort carriers USS Sangamon and Suwanee each launched two VMO-1 observation planes to become the first elements of what was eventually to

become a powerful American aerial task force based on Guam.31

Fonte Secured32

When the 3rd Marine Division re-opened a full-scale attack to secure the Fonte heights on 27 July, there was little evidence of the Japanese decision to withdraw to the northern sector of Guam. The enemy seemed as determined as ever to hold his ground, and the day’s fighting, focused on the left center of the division front, cost the Marines over a hundred casualties. Holding out, often to the last man, Japanese defenders made effective use of the broken terrain which was honeycombed with bunkers, caves, and trenches.

The twisted and broken remnants of a power line, which cut across Fonte Plateau and ran in front of Mt. Mangan, became the initial objective of 2/3, 2/9, and 2/21, which bore the brunt of the assault. (See Map VIII.) The battalions flanking the plateau fought their way forward to the line shortly before noon and then held up awaiting the advance of 2/9. Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s unit had been strafed and hit by bombs falling short during the aerial preparation for the morning’s attack, and the resulting reorganization had held up the assault companies for 80 minutes. About 1300, just after it finally came up on line with 2/3 and 2/21, 2/9 was hit hard by a surging counterattack, which boiled up out of the thick brush that blanketed the plateau. Company G, on the left of the battalion front, met most of this thrust by 150-200 Japanese troops. The tanks working with the infantry played a large part in the repulse of the attack, which finally subsided after almost two hours of hot, close-quarter action.

Shortly after this fight died down, Cushman recommended that his battalion stop its advance and dig in strongly for the night. A formidable strongpoint, a large cave-rimmed depression, which appeared to be the key to the remaining Japanese defensive system, lay just ahead in the path of 2/9. When division authorized a halt for the night, Cushman sent out scouts to find the best way to attack the strongpoint, issued replenishment supplies, and built up reserve ammunition stocks for the next day’s drive.

While the fighting on the flanks of 2/9 was not so frenzied as it was on the plateau itself, there was ample evidence here too that the Japanese had not lost their will to fight. Neither 2/3 nor 2/21 could advance much beyond the power line without being exposed to enemy flanking attacks. Toward the center of the division line, tank-infantry teams of 1/21 were heavily engaged all day in cleaning out enemy troops holed up in caves and dugouts in the vicinity of some demolished radio towers. Some Japanese still manned defenses in the quarry area near the center of the battalion zone, even after three days of

Map 29: Guam, 28 July-4 August 1944

constant attacks with explosives, gunfire, and flame. Despite the spirited enemy resistance, both here and on the plateau, the heavy Japanese losses foretold the end. The 3rd Division attack order for 28 July called for all three regiments to seize the FBHL in their zone.

The 9th Marines was to have the difficult task of driving south up the rugged slopes of Mts. Chachao and Alutom and along the ridge approaches to Mt. Tenjo. The crest of Tenjo was made an objective of the 77th Infantry Division, and the boundary between divisions was altered to show this change from the original landing plan. (See Map 29.) The axis of the Marine attack was plotted in the zone of 3/21, and, on the 27th, 3/9 moved into positions behind Lieutenant Colonel Duplantis’ battalion, ready to pass through on the 28th. The 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, attached to Colonel Craig’s regiment, relieved 3/9 on the right of the Marine line so that Major Hubbard’s men could spearhead the regimental assault on the peaks that loomed ahead.

The III Corps attack on the 28th was successful on all fronts, and the day ended with the Final Beachhead Line from Adelup to Magpo Point in American hands. At 0800, in a bloodless advance which culminated a week of patrol and mopping-up action in the hills between the two beachheads, a company of 1/305 seized the peak of Mt. Tenjo. The 2nd Battalion of the 307th Infantry then moved up to occupy the mountain and extend its lines north toward the new division boundary. Patrols of the 9th Marines made contact with 2/307 on the heights during the afternoon.

The 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines relieved 3/21 on position at 0800, and at 0910 began moving forward behind tightly controlled artillery and machine gun support. The 21st Marines battalion was attached to the 9th Marines to guard the open left flank behind Major Hubbard’s assault companies. Inside of a half hour, 3/9 was on its initial objective and abreast of 1/9 and 3/307. An hour later, Colonel Craig ordered a general advance of the three battalions toward the Chachao–Alutom massif. Although Craig had not received the IIIAC map overlay showing the new division boundary, he could plainly see the Army infantrymen on Mt. Tenjo’s slopes, so he contacted the commander of 2/307, while both officers were checking the flank positions of their units, and arranged a mutually satisfactory boundary.33 When the corps overlay arrived, its boundary was found to coincide with that worked out by the two commanders.

The only serious resistance encountered by the 9th Marines was centered on a strongpoint located on Mt. Chachao. Manned by a company of Japanese troops, presumably remnants of the 18th Infantry, this complex of machine gun nests and trenches guarded the trail along the ridge leading to Mt. Tenjo. Once 3/9 had developed this position, Major Hubbard called down artillery fire on the defenders to cover the infantry approach and conceal the movement of tanks to the rear to cut off the enemy escape route. When the artillery fire lifted, Companies I and K,

rushing the Japanese, drove steadily forward along the ridge, destroyed everything in their path, and charged the last emplacements with bayonets behind a shower of hand grenades. When the battle was over, 3/9 counted 135 Japanese dead in its zone. The victory enabled the 9th Marines to secure its objective from Apra Harbor to the 21st Marines boundary near Mt. Mangan.

In its drive to the FBHL, Colonel Butler’s regiment overran the 29th Division headquarters caves, located near the head of the Fonte River valley close to the wrecked radio towers, and wiped out the last defenders of Mt. Mangan as well. In both actions, tanks were in the forefront of the fighting and the Japanese tried desperately to knock them out with grenades and hand-carried antitank mines. Well covered by riflemen of 1/21 and 2/21 and their own machine gun fire, the tanks escaped unscathed from numerous fanatic attacks by individuals and small groups. By the time the 21st Marines were ready to dig in at dusk, all was quiet around the radio towers. The reverse slope defenses of Mt. Mangan were finally silenced.

The only other area of enemy opposition to the 3rd Division advance on 28 July was located in the depression on Fonte Plateau. Here, Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s careful preparations paid off in a smoothly executed attack. Utilizing tank, machine gun, and bazooka firing positions that had been pinpointed by reconnaissance the previous afternoon, 2/9 cut loose with a deadly crossfire which blanketed every cave entrance in the pit. Under cover of this fire, a picked assault group with flamethrowers and demolitions worked its way down from the rim and methodically destroyed every enemy position without losing a man. Once this strongpoint was reduced, 2/9, working with 2/3 and 2/21, was able to clear the rest of the plateau area and secure its share of the FBHL. Cushman’s battalion, in four hectic and wearying days of hard fighting for control of Fonte had lost 62 men killed and 179 wounded, but it had captured the anchor position of the enemy defenses.

As night fell across the island on the 28th, reports came in from all along the new Marine positions that scattered Japanese holdouts, who had purposely or unknowingly been bypassed during the day’s advance, were trying to infiltrate the lines heading north. This attempted exodus from the Marine beachhead by a relative handful of enemy survivors reflected the orders that had been passed by the 29th Division following the unsuccessful counterattack of 26 July.

The able-bodied fighting men were directed to disengage on the night of the 28th and withdraw through Ordot to prepared positions near Barrigada and Finegayan, there “to engage in delaying action in the jungle in northern Guam to hold the island as long as possible.”34 All sick and wounded combatants and Japanese civilians not attached to fighting units were started north on the night of the 27th, the division hospital and its patients to a position behind Mt. Santa Rosa and the civilians to “a safe area further north.”35 Accompanying this first

echelon was the Thirty-first Army commander, General Obata, and three of his staff officers, who left the Fonte headquarters at midnight on the 27th to move to Ordot. At the same time, one of General Takashina’s staff was also sent to Ordot to marshal all available motor transport and move rations and supplies to storage areas in the jungle north of Mt. Santa Rosa.

General Takashina and Lieutenant Colonel Takeda remained behind at the Fonte headquarters when the withdrawal began, and as a result were directly involved in the fighting on the 28th, when Marine tanks attacked the 29th Division cave CP area. At about 1100, as it became increasingly apparent that the dwindling number of Japanese defenders could not stop the rampaging tanks, General Takashina decided to make a break while there was still a chance to escape north. Then, as Takeda recalled the events, the two Japanese officers:

... stole out of the headquarters cave and ran straight between some enemy tanks and jumped from a cliff. The U. S. tanks, sighting the two persons, fired volleys of tracer bullets. Fortunately for the two, they managed to escape into a dead angle of the tank guns. About 1400 hours they reached a small stream at the northern foot of Mt. Macajna when the division commander was shot by machine gun fire from a U.S. tank, and died a heroic death, his heart having been penetrated by a bullet.36

With Takashina’s death in battle, the tactical command of all Japanese forces remaining on Guam was assumed by General Obata. He had only a few senior officers remaining to rally the surviving defenders and organize cohesive units from the shattered remnants of the battalions that had fought to hold the heights above the Asan-Adelup beaches. All through the night of 28 July, Japanese troops trudged along the paths that led from Fonte to Ordot, finding their way at times by the light of American flares. At Ordot, two traffic control points guided men toward Barrigada, where three composite infantry companies were forming, or toward Finegayan, where a force of five composite companies was to man blocking positions. As he fully expected the Americans to conduct an aggressive pursuit on the 29th, General Obata ordered Lieutenant Colonel Takada to organize a delaying force that would hold back the Marines until the withdrawal could be effected.

Contrary to the Japanese commander’s expectations, General Geiger had decided to rest his battle-weary assault troops before launching a full-scale attack to the north. The substance of his orders to the 3rd and 77th Divisions on 29 July was to eliminate the last vestiges of Japanese resistance within the FBHL, to organize the line of defense, and to patrol in strength to the front. All during the day, small but sharp fights flared up wherever 3rd Division Marines strove to wipe out the isolated pockets of enemy defenders that still held out within the beachhead perimeter. A very few Japanese surrendered, and most of these men were dazed, wounded, and unable to resist further. Almost all the enemy died fighting instead.

Although they made few contacts with retreating Japanese, Marine and Army patrols began to encounter

increasing numbers of Guamanians, who started to move toward the American lines as the enemy relaxed his watch. Intelligence provided by the natives confirmed patrol and aerial observer reports that the Japanese were headed for northern Guam. There was no strong defensive position within 2,000 yards of the FBHL, and there were ample signs of a hasty withdrawal. Patrols found a wealth of weapons, ammunition dumps, and caves crammed with supplies of all types in the area ringing the III Corps position. The discoveries emphasized the sorry plight of the ill-equipped and ill-fed men, who were struggling north through the jungle, punished by constant harassing and interdiction fires by Corps Artillery and the machine guns and bombs of carrier air.

The 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines was relieved on line by 1/3 on the 29th and was placed in division reserve for a short and well-earned rest. As the 3rd Marines was readied for a new phase in the battle, the regiment received a new commander, Colonel James A. Stuart, who had been the D-3. As a part of a division-wide shift in individual command and staff responsibilities, Colonel Hall was reassigned duties as the D-4.37 The changes seemed to be in keeping with the aura of preparation and reorientation that was prevalent throughout the IIIAC positions. Everywhere the assault troops and the service and support units were refurbishing equipment and stockpiling ammunition and supplies for the drive into the northern jungle.

Although the Japanese were no longer in close contact with the Americans, the patrols sent out on the 30th ran into scattered enemy fire as soon as they began to move up from the belt of lowland between Agana and Pago Bays and onto the northern plateau. All reconnaissance and other intelligence indicated that the Japanese were ready to defend the road that forked north of Agana, one branch leading to Finegayan and the other to Barrigada. (See Map 29.)

A Base of Operations38

Before General Geiger was ready to launch a drive north on an island-wide front, he needed assurance that his rear was secure from attack. Equally as well, he had to be certain that he possessed the supplies and support forces necessary to sustain an advance by two divisions through extremely difficult country against an opponent that was battered but by no means beaten.

To answer one requirement, knowledge

Pontoon barge loaded with fuel drums at the reef transfer line off Guam. (USA SC 210553)

Guamanian women wash their clothes in a shell hole in the midst of a refugee tent city behind American lines. (USMC 92233)

of the enemy situation in southern Guam, the 77th Division sent infantry patrols deep into the mountains and jungle in the vicinity of the FBHL. On the 27th, General Bruce ordered the 77th Reconnaissance Troop to investigate reports that the Japanese might still be present in strength, particularly in the center of the island near Mt. Lamlam. Five small patrols set out, two for objectives on the east coast, two to the southeast, and one down the southwest coast. Although the sickness of one member forced the patrol to Ylig and Pago Bays to turn back after it had covered 8,000 yards, the others stayed out three days checking all signs of the Japanese. Scattered opposition was encountered from snipers and small units by the patrols when they moved south along the mountainous spine of the island, but there was no evidence of enemy resistance in strength. As the mission of the patrols was reconnaissance not combat, the soldiers evaded most of the enemy troops they spotted, noting that the Japanese were all headed north. Other patrols sent out on the 29th and 30th travelled along the 77th Division proposed route of advance to Pago Bay. They gained valuable terrain intelligence to aid General Bruce in planning the difficult movement of his regiments east and then north through the jungle to come up on line with the 3rd Marine Division.

Once General Geiger knew that no significant Japanese force was present in southern Guam, he assigned responsibility for its control and pacification to his smallest major tactical unit, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. Plans were formulated for General Shepherd’s regiments to relieve elements of the 77th Division when the fighting on Orote ended.

In many ways, the assault phase of the Guam operation was partially over when IIIAC was ready to launch its northern offensive. Apra Harbor, the key objective of the dual landing operation, had been secured and was being converted into a major anchorage. Seabees and engineers had cleared beaches that had been battlegrounds and had rebuilt and replaced roads and bridges to handle heavy vehicular traffic. Extensive supply dumps, repair facilities, and other service installations had begun to take on the appearance of order and permanence.