Chapter 5: Seizure of Northern Guam

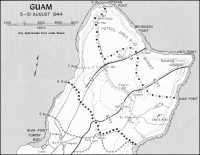

Tiyan and Barrigada1

From their hard-won positions on the Fonte heights and from the slopes of the mountain ridges that marked the trace of the FBHL, the assault troops of III Corps could easily see the broad expanse of jungle, which covered the northern plateau. Just forward of the 3rd Marine Division positions, the ground fell away sharply to a brush-covered lowland studded with small hills where the Agana River flowed into a large swamp southeast of the capital. The terrain in front of the 77th Infantry Division left flank was badly cut up by ravines formed by stream tributaries of the Pago River. Most of the rest of General Bruce’s zone of advance was also high ground, trackless and dotted with barriers of thick vegetation, which gradually grew denser on the approaches to Pago Bay. (See Map 29. )

The IIIAC scheme of maneuver for the 31 July attack called for the 77th Division to move northeast from its FBHL positions, pivoting on left flank units to come abreast of the 3rd Division on a cross-island objective line, which ran just north of Agana, turned south through the Ordot area, and then headed east to the coast at Pago Point. General Bruce’s plan directed an advance in regimental columns to effect the quickest possible passage of the 10 miles of hill country that separated Mt. Tenjo from the objective. Thorough reconnaissance had indicated that no significant enemy opposition would be encountered—and none was.

On schedule at 0630 on the 31st, the 77th Division moved out from the FBHL with the 307th Infantry in the lead. At first the soldiers were able to follow a fresh-cut road that led along the axis of advance, but the head of the column soon passed the sweating engineers and their bulldozers, which were engaged in a running battle with the rain-sodden ground. Striking out cross-country, the long, snaking line trudged over the rugged terrain in a march that seemed at times to involve more up and down movement than it did forward progress. One marcher later described his experiences graphically:–

The distance across the island is not far, as the crow flies, but unluckily we can’t fly. The nearest I came to flying was while descending the slippery side of a mountain in a sitting position. ... After advancing a few yards you find that the handle of the machine gun on your

Column of soldiers of the 305th Infantry advances cross-island on 31 July at the start of the attack on northern Guam. (USA SC272338)

Jungle trail is scouted by Marine tanks with covering infantry during the advance in northern Guam. (USMC 91166)

shoulder, your pack and shovel, canteens, knife, and machete all stick out at right angles and are as tenacious in their grip on the surrounding underbrush as a dozen grappling hooks. Straining, sweating, and swearing avails you nothing so you decide on a full-bodied lunge—success crowns your efforts as all the entangling encumbrances decided to give up the struggle simultaneously. Just before you hit the ground a low swinging vine breaks your fall by looping itself under your chin, almost decapitating you and snapping your helmet fifteen yards to the rear. ... You untangle your equipment, retrieve your helmet, and move on. The flies and mosquitos have discovered your route of march and have called up the reinforcements including the underfed and undernourished who regard us as walking blood banks. We continue to push on. ...2

Despite the difficult terrain, the 307th kept up a good pace and reached the Pago River early in the afternoon. Patrols discovered an unguarded concentration camp on the banks of the river and released a group of about 2,000 happy Guamanians. As the natives started moving back toward Agat along the column of soldiers, the Americans shared their rations, cigarettes, and whatever else they could spare with the hungry men, women, and children.

The lead unit of Colonel Tanzola’s regimental column, the 3rd Battalion, 305th Infantry, moving to the right rear of the 307th, met the only opposition that was offered to the advance of the 77th Division. As scouts of 3/305 approached the village of Yona late in the afternoon of the 31st, a number of Japanese hidden amidst the buildings opened fire. Deploying quickly, the leading company attacked and overran the village, killing 5 enemy and scattering the remainder of a force estimated at 50 men. Moving on, the 3rd Battalion reached Pago Point before nightfall and set up on a hill there in all-around defense. Companies of the other battalions of the 305th established blocking positions along the division southern boundary from that point to the FBHL, where the 4th Marines had relieved the regiment earlier in the day. With the advance of the 77th Division to the east coast, the 1st Brigade, temporarily reinforced by the 306th Infantry, assumed responsibility for pacifying the southern half of Guam.

Like the 77th Division, the 3rd Marine Division encountered little opposition on 31 July. General Turnage attacked with three regiments abreast at 0630, and by nightfall, when the advancing units held up, they had seized 4,000-5,000 yards of important terrain, including 4,000 yards of the crucial Agana-Pago Bay Road. The capital of the island was once again in American hands, and in the town plaza, amidst the shattered remnants of houses and government buildings, an advance division supply dump was operating at a brisk pace.

The honor of liberating Agana fell to 3/3, which advanced up the coastal road. At 1030, scouts of its assault platoons entered the town cautiously, threading their way through the rubble and the mines, which were strewn everywhere. Within 15 minutes, the battalion had reached the central plaza, and by noon was through the ruins and had set up in the northern outskirts on the

regimental objective. The rest of the 3rd Marines was soon up on line with the 3rd Battalion. At the start of the day’s advance, 1/3 had held positions along the northern lip of the Fonte River valley, where its lines were soon masked by the forward movement of 2/21. Temporarily in reserve, 1/3 then followed up the assault units of 2/3, which reached and secured its portion of the Agana-Pago Bay Road by noon.

The road was also the initial objective of the 21st Marines, but the lead elements of 2/21 and 3/21, with a longer distance and more rugged terrain to travel, did not reach their goal until 1350. Moving along the right boundary, 3/21 tangled with a small force of Japanese holding a pillbox near Ordot and wiped out the defenders, one of the few such clashes during the day’s advance. In the same vicinity, the 3/21 command post group, moving to a new forward position, scattered a force of 15-20 Japanese it encountered behind the lines. The enemy were evidently unaware that the Marine advance had passed them by, a tribute to the nature of the terrain.

On the right of the division zone of action, the 9th Marines had the farthest distance to go on 31 July over ground as bad as that any unit encountered. Like 3/21 on its left flank, 1/9 met and overcame resistance from a small outpost of enemy troops left behind to impede movement through the Ordot supply area. Then, at 1415, two enemy light tanks appeared out of the brush, spraying the advancing Marines with machine gun fire, killing one man and wounding three others. An alert bazooka team took care of both tanks, and the advance resumed. At 1510, the 9th Marines had reached its objective, which was partially along the cross-island road. A platoon of the division tank battalion was able to join the regiment and add strength to the antitank defenses.

Earlier in the afternoon, General Geiger had authorized the 3rd Division to continue moving forward as long as firm contact was maintained across the front. Although General Turnage alerted all units for a possible further advance, only the 3rd Marines actually moved out. The 21st Marines committing 1/21 on the left, was engaged in shifting its frontline units to the right, in order to maintain contact with the 9th Marines, while the 9th was consolidating its link with the 307th Infantry along the division boundary.

Major Bastian’s 3/3 had little difficulty in advancing from Agana once it jumped off at 1545. Before dusk, it had seized 1,200-1,500 yards of the roads northeast of the capital, one of which led to Finegayan and the other to Barrigada through the road junction village of San Antonio. On the right, 1/3 passed through the lines of the 2nd Battalion and almost immediately entered an extensive swamp, which was the source of the Agana River. The going was slow and rough, and it was dark before the lead elements could dig in on dry land. The assault battalions set up perimeter defenses for the night about a mile and a half apart, with 2/3 in reserve positions blocking the gap.

As 3/3 was digging in, two small jeep-mounted patrols of Reconnaissance Company cleared the forward positions of the battalion and moved along the road to San Antonio. Their mission was to check the trail network

leading to Tumon Bay and Tiyan airfield. Both patrols sighted small groups of Japanese, hiding out in houses along the routes followed, and exchanged fire with them before turning back to the outskirts of Agana. As a combined patrol, the group then drove along the shore road until it was stopped by a tangle of trees blown across the path. In the gathering darkness, the reconnaissance force turned back again with little more to report to General Turnage than that some Japanese were located forward of the Marine lines. At the division CP, plans were laid for new motorized patrols the following day, this time bolstered by half-tracks and tanks.3

After a quiet night with no enemy activity, the 3rd Division attacked at 0700 on the 1st with a scheme of maneuver calculated to pinch the 21st Marines out of the front line of a narrowing division zone. General Turnage ordered the 3rd Marines to hold its positions once the 1st Battalion moved out of the swamp area and came abreast of 3/3. In advancing, 1/3 extended toward its right, closing in front of 1/21. The 21st Marines moved out with the 2nd and 3rd Battalions abreast, but 2/21 soon halted and withdrew to reserve positions when it was covered by 3/21. At 0910, the 3rd Battalion was ordered to pivot on its right and occupy the boundary between the 3rd and 9th Marines until its position was masked by the advance of the 9th. By 1400, Colonel Craig’s regiment had completed this maneuver, after moving with difficulty through heavy brush and irregular terrain to seize the remaining portion of the Agana-Pago Bay Road in its zone. The 21st Marines, less 3/21, which was attached to the 3rd Marines, was ordered into division reserve during the day, replacing 2/9, which reverted to regimental control.

With the readjustment of lines completed, the division resumed its general advance at 1500. Forward progress was steady and enemy resistance negligible. By 1745, when General Turnage called a halt, the center of the division was just short of the airfield dispersal area and the right was within easy striking distance of San Antonio.

The greatest problem facing the 3rd Division on 1 August was the hundreds of mines that the Japanese had planted on all roads leading north. The bomb-disposal teams of the 19th Marines were hard put to find, let alone remove or destroy, all the lethal explosives the enemy had buried. Inevitably, several vehicles were blown apart and their passengers killed or wounded during the day. When an armored reconnaissance patrol was attempted at 1745, its nine tanks and a half-track were turned back by a profusion of mines on the coastal road to Finegayan. The armored vehicles were able to drive along the entire western side of Tiyan airfield, where it ran along a low cliff, but they could find no usable roads that led down toward the coast. Near the far end of the airstrip, an undetermined number of Japanese opened fire on the tanks from concealed positions in the brush, but the patrol avoided a fire fight in order to return to friendly positions before dark. Like the motorized reconnaissance on the previous

afternoon, this patrol on 1 August developed little vital information on Japanese dispositions or strength in the 3rd Division zone.

Undoubtedly, the most significant accomplishment of the day was the seizure of the Agana-Pago Bay Road along its entire length. This feat provided the solution to formidable logistical problems, which would otherwise have plagued the 77th Division. The Army assault regiments, the 307th and 305th Infantry, had jumped off at 0700 on the 1st and had crossed the Pago River soon after. Inexplicably, the Japanese had failed to destroy the main bridge over the river, and 3/305 seized it without incident at 0800. Within two hours, both regiments had secured the cross-island road in their zones, a stretch including RJ 171, where an intersecting road curved north through the jungle to San Antonio. The soldiers, keeping their direction by compass bearings, pushed on through the dense vegetation, taking advantage of trails wherever they occurred and blazing new paths where there were none. All assault units were short of rations and water, but were well supplied with small arms ammunition; the Japanese had provided scant opportunity to do much firing. By nightfall, the 305th Infantry was located in perimeter defenses one and a half miles northeast of RJ 171, and the 307th was generally on line with it and in contact with the 9th Marines near San Antonio. The 306th Infantry, less 2/306 in corps reserve, was set up near RJ 171, having marched there during the day after being relieved on the FBHL by the 22nd Marines.

The 77th Division began to use the Agana-Pago Bay Road as its main supply route (MSR) almost as soon as it was captured. In planning the IIIAC drive to seize northern Guam, General Geiger had counted on the 77th Division to cut a new road from the Agat beachhead to the east coast road near Yona. Terrain difficulties, compounded by frequent rains, and the time factors involved forced abandonment of the road-building project late on the 31st. The only practical alternative to construction of a new MSR was for both divisions to use the same road, a solution that General Bruce has noted was unorthodox enough for “the books [to] say it can’t be done, but on Guam it was done—it had to be.”4 At 1620 on the 1st, General Geiger issued an order assigning the 77th Division priority over all traffic on the west coast road between Agat and a turnaround north of Adelup Point and equal priority with the 3rd Division on the road beyond Adelup as far as the division boundary.

Moving throughout the afternoon and on through the night (with headlights as far as Agana and blackout lights beyond), a steady procession of 77th Division trucks, jeeps, and trailers moved supplies and equipment across the 3rd Division zone. Three battalions of artillery and the light tank company of the 706th Tank Battalion also travelled the route on the 1st. General Bruce ordered the medium tank companies that were attached to his RCTs, the division artillery headquarters, and the remaining 155-mm howitzer battalion to make the move as early as possible on the morning of the 2nd. The

general wanted as much support available as he could get, for intelligence sources all indicated that the Japanese were present in force in the Barrigada area, the next 77th Division objective.

In order to pinpoint the suspected enemy positions, the division commander ordered an armored reconnaissance made. Fourteen light tanks moved out along the road to San Antonio at 0630 on 2 August, a half-hour prior to the general division attack. About 800 yards beyond San Antonio on the road to Barrigada, the tanks were fired on by enemy troops concealed in the thick bordering jungle. After replying to this opposition with machine gun and cannon fire, the tanks returned to the American lines at 0730. They were soon sent out again, but this time got as far as Barrigada without meeting any resistance.

At the road fork in the village, the tanks at first turned left to move toward Mt. Barrigada on the road to Finegayan. Opposite the mountain the tanks encountered a trio of trucks, backed by enemy riflemen, blocking the way. The tank gunners made short work of both trucks and defenders, killing an estimated 35 Japanese. Returning to Barrigada, the armored column moved northeast along a road that appeared to swing around the other side of the mountain. Within 1,000 yards of the village, the track had dwindled to the size of a foot trail, and the lead tank got hung up on a stump. At this moment, Japanese troops began firing from all sides with rifles, machine guns, and 20-mm guns. Some enemy soldiers tried to rush the tanks, but they were swept away by heavy fire from bow and turret guns. Once the stranded tank was able to work itself loose, the armored patrol withdrew without having suffered any losses.

As the day wore on, this morning tank action proved to be the sparring session before the main event. The 307th Infantry, after pausing along the road to San Antonio to distribute badly needed water and rations, moved out again at 1030 and ran head on into a bristling enemy defensive position covering approaches to the mountain and the village. The day’s plan of attack called for 1/307 on the left to move through the jungle, cross the road to Finegayan north of Barrigada, and seize the western slopes of the mountain; 3/307 was to move through the village and attack the southern slopes. Both units met increasingly steady resistance from Japanese manning prepared positions in the jungle and amidst the scattered village houses. Companies that had been assigned wide attack zones were crowded together as withering defensive fire channelized the assault. The regimental reserve, 2/307, was committed to the fight, and both light and medium tanks were called up to support the advance. Tank fire-support, particularly the destruction wrought by the 75s of the Shermans, helped smash an opening in the defensive barrier; tank armor shielded wounded infantrymen being evacuated under Japanese fire. When the 307th dug in for the night, it held positions in Barrigada just beyond the road junction.

On the right of the division zone, the 305th Infantry ran up against the eastern extension of the enemy position at Barrigada. Hidden in the jungle, well camouflaged and dug in, the Japanese

held their fire until the assault platoons of 3/305 and 1/305 were almost upon them and then shot with deadly accuracy. This tactic frustrated all attempts to outflank the enemy covering the open ground near Barrigada, and the battle resolved itself into a grinding tank-infantry action where gains of a few yards often took hours to win. Like the 307th, the 305th was finally able to fight its way past the Barrigada road junction and into the midst of the Japanese defenses when the approach of darkness forced a halt. The 77th Division, its combat experience thus far limited to minor patrol and defensive clashes, had had a rough introduction to the offensive in jungle warfare. In fighting often confused and frustrating, 29 men had been killed and 98 wounded, but the soldiers had proved their mettle.5

One unfortunate result of the day’s action was that a gap developed between the 3rd and 77th Divisions. In the wild tangle of trees and undergrowth along the boundary, the Marines and soldiers lost sight of each other after the morning attack began. The company of the 307th charged with maintaining contact spent most of its time out of touch with its own regiment as well as with the 9th Marines. General Turnage attached 2/21 to the 9th for the night to guard the open flank, and Lieutenant Colonel Smoak disposed his men along an unimproved trail that stretched from San Antonio to the positions that 3/9 had reached opposite Mt. Barrigada.

The 3rd Marine Division did not encounter any significant opposition on 2 August for the third day in a row. As a result, the 9th Marines overran its objective, Tiyan airfield, by 0910. On order from division, Colonel Craig held his troops up at the north end of the field until the 3rd Marines could come up on line.

During this lull, a Japanese tank caused quite a bit of excitement when it broke through the extended 9th Marines lines and raced through the airfield dispersal area toward the rear of the 3rd Marines. As the tank roared by the CP of 1/3, one of the crew, scorning the main armament “opened the turret and began to shoot wildly with a pistol”6 at the Marines, who were scurrying to take cover. When the tank careened into a ditch several hundred yards farther on, the crew abandoned it and escaped into the brush. Marine mediums came up later in the afternoon and destroyed the enemy vehicle.

About the time the Shermans were blasting the hulk of the enemy tank, the 3rd Marines was striving to take as much ground as it could before dark. Colonel Stuart’s regiment had been slowed all day by dense vegetation and mines along the few roads and trails in its zone. It was 1400 before the 3rd came abreast of the 9th. At that time all division assault units continued the attack with the Japanese offering only sporadic and ineffectual resistance. As the 3rd Marines wrestled its way through the jungle along the road to Finegayan, 3/21 covered the left flank of the regiment, reconnoitering the

bulging cape formed by Saupon and Ypao Points. Where the division zone narrowed at Tumon Bay, 3/21 was pinched out of line and reverted to control of the 21st Marines as part of the reserve. So difficult was the problem of contact in the jungle that the 3rd Marines continued advancing after dusk until it could reach a favorable open area to hold up for the night. There, Colonel Stuart and his executive officer, Colonel James Snedeker, personally helped tie in the positions of assault units by the light of a full moon.

An armored reconnaissance patrol cleared the front lines of the 3rd Marines at 1815, its mission the same as that of the similar group sent out the previous evening—find the Japanese. After moving about 1,200 yards toward Finegayan, the patrol spotted several groups of the enemy, but did not engage them, turning back instead on order at 1845. This sighting confirmed previous intelligence that the Japanese were located in the vicinity of Finegayan, but there was still no strong evidence of their numbers or dispositions.

No one at III Corps or 3rd Division headquarters doubted that the lull in the battle was temporary. The Japanese already were defending bitterly one road that led to Finegayan in the 77th Division zone, and the 3rd Division was advancing astride the other main artery, which led to the junction near the village. Beyond Finegayan, the principal roads led to Ritidian Point and Mt. Santa Rosa. While there was no indication that the Japanese would defend the northernmost point of the island, aerial reconnaissance, captured documents, prisoner interrogations, and information supplied by Guamanians all pointed to Mt. Santa Rosa as the center of resistance.

Concerned though he was with the immediate struggle to break through the outpost defenses at Barrigada and Finegayan, General Geiger was also looking ahead to the capture of Mt. Santa Rosa. Once it had driven past the coastal indentation of Tumon Bay, IIIAC would be operating in a wider zone, one just as choked with jungle growth and as hard to traverse as any area yet encountered. Geiger planned to use the 77th Division to reduce enemy positions in the vicinity of Santa Rosa, leaving the capture of most of Guam north of the mountain to the 3rd Division. Under the circumstances, the corps commander believed that he could make good use of the 1st Brigade in the final clean-up drive, which would narrow the zones of attack and enable Generals Bruce, Turnage, and Shepherd to employ their men to best advantage in the difficult terrain.

Oral instructions were issued on the morning of 2 August for the brigade to be prepared to move to the vicinity of Tiyan airfield in corps reserve. General Shepherd in turn issued an operation order at 1030 directing the 4th Marines (less two companies on distant patrol ) to assemble at Maanot Pass ready to move north by 0800 on the 3rd. The 22nd Marines (less 1/22) was ordered to continue patrolling and to prepare to move on 5 August.7 Corps planned to shift responsibility for the

security of southern Guam from the brigade to a task force composed in the main of 1/22, the 9th Defense Battalion, and the 7th Antiaircraft Artillery (Automatic Weapons) Battalion, all under the defense battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel O’Neil.

Following its relief of the 77th Division, the brigade had sent out deep, far-ranging patrols to continue the hunt for Japanese stragglers and to locate and encourage Guamanians to enter friendly lines. The patrols were made strong enough—all were at least reinforced platoons—to handle any potential opposition. Although the Marines found a considerable number of defensive positions wherever units of the 38th Infantry and 10th IMR had been stationed prior to W-Day, only a few enemy troops were discovered and these were swiftly eliminated. On 2 August, a 4th Marines patrol moving toward Talofofo Bay ran across a group of about 2,000 natives, who were directed to report in to the corps compound near Agat. Civil affairs officers there were already caring for approximately 5,000 Guamanians, most of whom had filtered into American lines since 31 July. In the 3rd Division zone, an additional 530 civilians were being fed and housed in a temporary camp, and the number coming in increased sharply as the Japanese retreated to the north.

The problems involved in handling thousands of civilians were new to Marines in the Pacific, but they were anticipated. Whenever prelanding civil affairs plans went awry, there was a will to find and apply alternate solutions. Much improvisation was necessary, the corps C-1 recalled, because the supplies intended for the Guamanians, which “were loaded on a ship with a low unloading priority ... reached the beach after fifteen thousand civilians were within our lines.”8 As a result of this situation, effective emergency measures were taken. As soon as the first natives were contacted:

... every piece of canvas which could be spared by units of Corps, was turned over to the Civil Affairs Section and a camp was established south of Agat. 350 shelter tents were borrowed from the 3rd Marine Division. The Army loaned tentage for a 100-bed hospital which the Corps Surgeon borrowed from the Navy. The Corps Medical Battalion made 250 beds available for civilians. A Marine officer was assigned to build the Agat camp. 36 military police from the Corps military police were assigned to guard the camp. Badly needed trucks were borrowed from the motor pool and from two to six trucks worked constantly at hauling captured enemy food supplies and materials salvaged from bombed buildings, including the Marine Barracks. All this was immediately put to use for civilian relief.9

The Agat Camp was soon crowded, but no one went hungry; everyone had at least a piece of canvas overhead, and adequate medical attention was assured. On 2 August, as it became increasingly apparent that there was no organized enemy activity in southern Guam, corps issued an order stating that all Guamanians living south of a line from Agat to Pago Bay would be encouraged to remain at their homes, resume their normal pursuits with emphasis on agriculture, and obtain food and medical attention as necessary

from the Agat camp.10 As soon as priority camp shelter construction was well started, the Corps Service Group began to employ some Guamanians as laborers. Plans were laid to organize a native police and patrol force. The rough terrain of Guam offered ample hiding places for individuals and small groups of the enemy. It was believed that native familiarity with the mountains and jungle would be of great value in hunting down any holdouts.

Objective: Finegayan-Yigo Road11

General Obata, after surveying the positions his men had prepared at Barrigada, determined that they were unsuitable for a sustained defensive effort. Although he considered that the jungle maze around the village would be an aid to ambush and outpost action, he also believed that the dense growth would hinder the establishment of effective firing positions and would work as well to bar counterattacks. The army commander’s instructions to Major General Tamura, his chief of staff, were to fight a delaying action at Barrigada to gain time for the construction of final defensive positions in the Mt. Mataguac–Mt. Santa Rosa area. The hard fighting at Barrigada on 2 August showed how well the Japanese troops could carry out their orders to hold up the advance of the 77th Division in the eastern sector of the outpost defenses. On the 3rd, the disposition of American forces, the terrain, and the roadnet combined to bring the 3rd Marine Division into a head-on clash with the enemy deployed near Finegayan, guarding the western approaches to the final Japanese stronghold.

Ten days of hard-won experience had demonstrated that even the heaviest caliber guns had a difficult time making any impression on Japanese defenses dug into the rugged terrain of Guam. Where thick jungle cover added its mantle, the task of blasting out the enemy was doubly difficult. Impressed by the need to employ every available supporting weapon to maximum effectiveness, both Admiral Conolly and General Geiger took steps to muster a formidable array of ships, artillery, and aircraft to aid the advance to the north.

On 2 August, CTF 53 reorganized his gunfire support ships to cover operations along both coasts. Admiral Ainsworth, his flag in the light cruiser Honolulu, took station on the east side of the island with a battleship, another cruiser, and five destroyers. On the west, Rear Admiral C. Turner Joy in the heavy cruiser Wichita commanded a similar task unit, which was augmented by a third cruiser and four gunboats.12 All the 155-mm guns and howitzers of General del Valle’s Corps Artillery were displaced forward by the morning of 3 August to positions where they could reinforce the fires of seven

battalions of 75-mm and 105-mm and one of 155-mm howitzers. Plans were laid to increase the aerial fire support available by supplementing carrier aircraft strikes with sorties by Seventh Air Force planes. The first deep support missions flown by Saipan-based B-25s and P-47s were directed against RJ 460 during the afternoon of the 3rd. (See Map 30.)

There was heavy fighting in the 3rd Marine Division zone on 3 August at RJ 177 where the roads from Agana and Barrigada crossed. Lieutenant Colonel Randall’s 1/9 bore the brunt of the day’s action as it advanced astride the road from Agana. At 0910, when the lead company (B) was about 500 yards from the junction, its men were driven to cover by a sudden burst of fire from Japanese dug in on both sides of the route. In a rough, close-quarter battle, two Marine tanks, an assault platoon of infantry, and plentiful supporting fire from all available weapons finished off the Japanese defenders at a cost of three men killed and seven wounded. Moving through the shambles of the enemy position, which was littered with 105 dead, 1/9 continued its advance on RJ 177. Continued opposition from Japanese troops hidden in the brush and ditches along the road was steady but light. By 1300, the battalion had driven past the junction. Shortly thereafter, as fresh assault troops relieved Company B, Lieutenant Colonel Randall received orders to dig in for the night.

On both flanks of 1/9, Marine units made good progress marked by clashes with small enemy delaying forces. The jungle and the constant problems it posed to movement and contact continued to be the most formidable obstacle. When it ended its advance along the coast, 3/3 was nearly 3,000 yards forward of the positions of the 9th Marines on the division boundary. There 3/9, now commanded by Major Jess P. Ferrill, Jr.,13 held up when it reached the Finegayan-Barrigada road because the battalion had no contact with the Army units on its right. At 1615, in order to plug the gap between divisions, General Turnage attached 3/21 to the 9th Marines; the battalion moved to blocking positions along the boundary to the right rear of 3/9.

As the Marines were digging in near RJ 177 late in the afternoon, an armored reconnaissance in force was attempted. Organized earlier in the day under the 3rd Tank Battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hartnoll J. Withers, the patrol group consisted of the Shermans of Company A reinforced by battalion staff tanks, two half-tracks from Reconnaissance Company, four radio jeeps, and mounted in trucks, Company I, 3/21 and a mine-clearing detachment of the 19th Marines.

Originally, the motorized patrol was scheduled to clear American lines shortly after 1200, but it was held up by the fighting at RJ 177. When the patrol commander finally got the word to proceed at 1525, it was already too late to reach its original objective, Ritidian Point, and return during daylight. Lieutenant Colonel Withers was ordered instead to try to reach RJ 460

before turning back and to complete his mission on the following day.

Shortly after 1600, the buttoned-up half-track leading the patrol point reached RJ 177 and veered right instead of left, heading east toward Liguan and Yigo. Approximately 400 yards past the junction, Japanese forces on both sides of the road opened up on the point vehicles. For nearly two hours the small Marine force was caught up in a fire fight and partially cut off from aid. The jungle terrain limited the maneuvering of American tanks and infantry and gave the advantage to well-emplaced enemy field guns and small arms. Eventually, covering fire from Shermans with the point was able to break loose the ambushed force. When the Marines pulled back to RJ 177, they left behind a destroyed half-track and a damaged truck and took with them 15 casualties.14 Marine tank gunners reported that they had knocked out one Japanese tank, two 75-mm guns, and several machine guns.

The wrong-way turn at RJ 177 furnished ample evidence that the Japanese would dispute strongly any attempt to use the road to Liguan. The ambush also effectively killed the idea of a reconnaissance of the roads to Ritidian Point for the time being, as the enemy could be defending them as well. The risk was too great. Lieutenant Colonel Wither’s force was disbanded after it reentered American lines and its elements returned to parent units to take part in the general attack on 4 August.

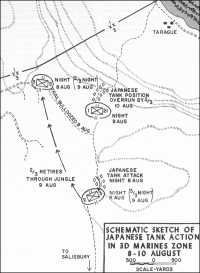

Plenty of action after dark on 3 August underscored the resurgence of enemy activity in the 3rd Marine Division zone. At 2200, two Japanese medium tanks roared down the Liguan road, crashed through the defenses set up by 1/9, firing steadily all the while, wheeled to the right at RJ 177, and sped west up the road toward Dededo. As they clattered through the positions held by 1/3, the enemy tanks continued to fire their 57-mm guns and machine guns at any target that showed. Despite all the return fire directed at them, the enemy armor escaped. This incident was the dramatic highlight of a series of clashes, which occurred all across the Marine front in the several hours before midnight. Then at 2300, American artillery fire, “placed perfectly”15 in an enemy assembly area forward of the regimental boundary, was responsible for breaking up a counterattack. After this, Japanese activity died away for the rest of the night.

In contrast with the situation in the 3rd Division zone on 3 August, where resistance was steady all day long, the advance of the 77th Division was marked by sporadic clashes with the Japanese. When the 307th and 305th Infantry Regiments moved out from their hard-won foxholes and emplacements at 0730, the enemy units that had fought so doggedly to hold Barrigada the previous afternoon had disappeared. In their stead, scattered through the jungle were lone snipers and small automatic weapons groups

which were a constant irritant but no real threat to a steady advance. By 0930, the Army regiments had secured Barrigada and with it an all-important well, which could supply the 77th Division with 30,000 gallons of fresh water daily. After a pause to reorganize and regroup, the advance continued at 1330 behind a rolling barrage fired by all four battalions of division artillery. The 307th, with tanks breaking trail, struggled through the jungle, meeting little enemy opposition on its way to the crest of Mt. Barrigada. By 1500, 3/307 had secured the summit, and shortly thereafter it began consolidating positions for night defense.

The difficulties imposed by dense vegetation and a sparse trail network kept down the pace and extent of the advance. In an effort to speed the progress of the 305th Infantry through the lush jungle, Colonel Tanzola narrowed his zone of attack and covered much of the area between Mt. Barrigada and the coast with patrols. Complicating the problems of contact and control, the Japanese fought what the regiment reported was a “good delaying action.”16 They staged a series of ambushes, which forced the Americans to deploy and maneuver against a foe that vanished as often as he stayed to fight.

The heavy opposition encountered at Barrigada on 2 August had caused the left flank units of the 77th Division to fall behind the Marines. Although some of the ground was regained on the 3rd, when the 3rd Division too was slowed by enemy resistance, at nightfall the corps line still slanted back from RJ 177 to Mt. Barrigada. Despite persistent efforts by the 307th Infantry, the combination of jungle and Japanese had defeated all efforts to make contact. In late afternoon, a tank-infantry patrol that tried to reach Marine lines using the road to Finegayan was stopped by a roadblock and then a barrier of mines, both well covered by enemy fire. One tank was disabled and had to be abandoned and destroyed when the outnumbered patrol withdrew.

This encounter with the Japanese on the Finegayan Road had an unfortunate sequel on 4 August. General Bruce, anxious to re-establish contact with the Marines as soon as possible after the attack opened that day, issued orders for another force of tanks and infantry to push through to the Marine lines. This patrol, spearheaded by Shermans, blasted its way through two roadblocks and opened fire on a third about 1045. This time, however, Company G of 2/9 held the position, not the Japanese; seven Marines were wounded before the company commander succeeded in stopping the fire poured out by the tank guns.17 Even after this unhappy incident, which was caused by a misunderstanding regarding recognition signals, there was still no contact between Army and Marine front lines. On both sides of the division boundary, assault units had already moved well

beyond the Finegayan road into the jungle.

In the 77th Division zone of action, where there were no roads and few trails paralleling the axis of advance, the main struggle on 4 August was with the rugged terrain. Shermans broke trail for the assault platoons of the 305th Infantry, and tank dozers cut roads behind the plodding forward companies. On the northern slopes of Mt. Barrigada, the soldiers of the 307th, cutting their way through the mass of brush, vines, and trees, could make no use of the crushing power of the tanks. Progress was agonizingly slow, despite the absence of any strong Japanese opposition. At noon, General Bruce ordered both assault regiments to concentrate their men in one or two battalion columns in order to speed passage through the jungle. If any mopping up had to be done, reserve units would handle the task. As if to emphasize the need for this decision, General Geiger informed Bruce about an hour later that III Corps was going to have to hold up the advance of the 3rd Division until the 77th could come abreast. By 1710, when the 307th reported that all of Mt. Barrigada was within its lines, the forward positions of the two divisions were more closely aligned. Soon afterwards, corps headquarters ordered a vigorous advance all along the front for 5 August.

A factor contributing to General Geiger’s order that held up the advance of the 3rd Division on the 4th was the stubborn resistance of the Japanese defending the road leading to Liguan and Yigo. Assault units of the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines hammered at the enemy strongpoints but made little headway in the face of interlocking fire from machine guns and cannon hidden in the brush. Again the lay of the land prevented the Marines from outflanking the Japanese or from bringing the full power of supporting weapons to bear. There was only enough maneuver room for about one infantry company to take part in the fight to seize the vital road.

Elsewhere in the 3rd Division zone on 4 August, the 3rd Marines was able to secure its portion of the day’s objective with little trouble. The 2nd Battalion stood fast in its positions near the coast, and the 1st Battalion moved along the road through Dededo to seize a fork where the branches continued north in two trails about a mile apart. (See Maps 29 and 30). Both units sent strong patrols forward of their lines to range ahead in the jungle as far as 1,000-1,200 yards. The reconnaissance uncovered a formidable array of abandoned enemy defenses facing toward Tumon Bay, but discovered few Japanese.

On the afternoon of the 4th, in a move calculated to take advantage of the widening division zone of attack, the 21st Marines (less 3/21) reentered the front lines. Elements of the 1st and 2nd Battalions replaced the left flank and center companies of 1/9 by 1730 in the area between the Dededo and Liguan roads. While the 3rd Division was thus redeploying its units for an attack on a three-regiment front, the 1st Brigade was completing its move to northern Guam. General Shepherd’s CP opened near San Antonio at 1200, and the 22nd Marines (less 1/22 ) completed its move into a bivouac area near Tiyan airfield by 1530.

On 5 August, the focal point of battle in the 3rd Marine Division zone continued to be the Japanese positions along the Liguan road. Again the 9th Marines bore the brunt of the fighting in jungle so thick that at one point an American tank passed within 15 yards of a Japanese medium and failed to spot it. Throughout the day, small arms fire stemming from many mutually supporting dugouts and trenches whip-sawed the Marine riflemen, and well-sited antitank guns slowed the advance of vital supporting armor. The steady attrition of three days’ fighting had taken its toll of the enemy, however. By dusk, when a Marine half-track knocked out the last Japanese 75-mm gun, 1/9 was firmly in possession of the ground that it had fought so hard to win. On the right of the 1st Battalion, 2/9, which had passed through 3/9 during the morning’s attack, was also astride the Liguan road, having fought its way forward through the jungle against moderate resistance.

Neither the 3rd nor the 21st Marines faced anything like the organized opposition encountered by the 9th on 5 August. In the center and on the left of the division zone, small groups of the enemy that attempted to halt the advance of the infantry were quickly overrun. When 2/21, moving along the road to RJ 460, was pinned down by automatic weapons fire, a platoon of tanks made short work of the enemy defenders, the crews of two machine guns. It became increasingly apparent during the day’s advance that the Japanese did not intend to hold the western sector of the island in any appreciable strength. Reconnaissance by Marine and Army light planes spotting for artillery and naval guns and sightings by carrier planes and the B-25s and P-47s attacking from Saipan pinpointed the Mt. Santa Rosa area as the center of enemy activity.

Although the assault units of the 77th Division found few Japanese during their arduous trek through the jungle on 5 August, there was no doubt that the final enemy bastion lay ahead of the soldiers. The flood of natives that entered American lines, the few prisoners that had been taken, and the supporting evidence of captured documents reinforced the reports of aerial observers. Much of the division effort on the 5th was directed toward moving troops into position to make a concerted drive on the Japanese forces known to be holding Mt. Santa Rosa and its outworks.

Committing the 306th Infantry at 0700, General Bruce ordered it to pass around the right flank of the 307th and attack in the zone formerly assigned to that regiment. Pinched out of the front lines by the advance of the 306th, the 307th Infantry was to replenish supplies and ammunition in preparation for a move to the center of the division zone of action and a drive against Yigo and Mt. Santa Rosa when ordered by division. The 306th, its attack formation a column of battalions, completed much of its planned maneuver on 5 August despite problems posed by the jungle, a lack of useful trails, and the maddening fact that available maps proved to be unreliable guides to terrain. With General Bruce’s permission, the regiment held up for the night about 2,000 yards short of the division boundary after 1/306 and 3/306 had both secured

Map 30: Guam, 5-10 August 1944

portions of the road to Yigo near the village of Ipapao. (See Map 30.)

For the 305th Infantry, the pattern of attack on 5 August had a monotonous sameness with the actions of the previous day. Deeply enmeshed in the jungle, the two assault battalions of the regiment hacked their way forward behind trail-breaking tanks and half-tracks. Direction was maintained by compass bearings, and when 2/305, in the lead, reached what it thought was the day’s objective about 1400, it had to cut a trail to the sea in order to verify its position. The 1st Battalion of the 305th set up about 1,000 yards to the rear of the 2nd, and both units, lashed by a driving rain in the forest gloom, dug in as best they could for all-around defense. In the area occupied by 1/305, the coral subsurface was only six to nine inches below ground level; no satisfactory weapons emplacements or foxholes could be constructed.18

At 0200 on 6 August, two Japanese medium tanks, accompanied by a platoon of infantry, came clattering out of the darkness and attacked south down the trail that led into the 1/305 perimeter. A swift outpouring of small arms fire scattered the enemy riflemen, but the tanks ignored the bullets and broke through the American defenses, continuing down the trail and firing at targets on both sides. Much of the heavy return fire ricocheted off the armor and added to the lethal shower of lead and steel that lashed the surrounding brush. After one of the tanks collided with a Sherman parked on the trail, then backed off and crushed a jeep, both enemy vehicles turned and raced back the way they had come, firing steadily all the while. Behind them the Japanese tankers left 15 Americans dead and 46 wounded; many of the men were casualties because they had been unable to dig in and therefore lacked effective cover from both tank and antitank fire.

The grim saga of the Japanese tanks was not over when they broke out of the 1/305 perimeter. At 0630, scouts of 2/305 ran into them, too. In search of a better route of advance, the Army battalion was retracing its steps along the trail it had blazed on 5 August. Cannon and machine gun fire from the two tanks, which were protected by a small rise of ground, quickly swept the path clear of infantrymen. American mediums worked forward along the narrow and congested trail to join the fight, but the advantage was with the enemy armor in hull defilade. Tree bursts from the Japanese tank shells scattered deadly fragments about, pinning the American infantry to the ground. Eventually, an 81-mm mortar crew was able to get its tube in action, find a clear path through the trees for its line of fire, and lob shells into the Japanese position. This silenced the enemy armor, and assault units that outflanked the tanks and came upon them from the rear found both abandoned. Three bodies were the only evidence of the defenders’ strength. The cost to 2/305 of the sharp and unexpected clash was 4 dead and at least 14 wounded.

These two tank-infantry battles were the highlights of 77th Division action on 6 August. Enemy opposition was

light and scattered otherwise, and all units spent the daylight hours getting into position for the attack on Mt. Santa Rosa. The basic scheme of maneuver planned by General Bruce’s staff called for the 306th Infantry to make a wide sweep on the left of the division zone, advancing as rapidly as possible in column to reach the vicinity of Lulog village north of the mountain. The regiment would patrol to the division boundary to keep contact with the Marines. The 307th Infantry, with most of the 706th Tank Battalion attached, would make the main effort, attacking to seize Yigo and RJ 415, before turning eastward to take the mountain itself. The 305th Infantry (less 3/305 in corps reserve) would continue its attack toward the mountain with the objective of seizing the high ground south of it.

A map overlay outlining this operation plan and projecting a new division boundary beyond Liguan was distributed to all 77th Division units on 5 August. On the same date, the corps operation plan, incorporating the basic scheme proposed by the 77th Division, was also distributed. There was no overlay with the corps plan, but its language clearly stated that there was a change in the division boundary, and gave its map coordinates. Unfortunately, the new boundary and that shown on the 77th Division overlay did not coincide from the vicinity of Mt. Mataguac to the village of Salisbury. The result was that “the zone of action of the 306th Infantry, making its sweep around Mt. Santa Rosa on the division left was ... partially within the 3rd Marine Division’s operational area.”19

As part of its move into attack position, 1/306 closed to the division boundary northwest of Ipapao during 6 August and made contact with 2/9. The 3rd Battalion of the 306th advanced to within 2,000 yards of Yigo, securing a large section of the road, which was to be the axis of the attack by the 307th Infantry. Behind the assault units of the 306th, the road was cleared of the enemy back to RJ 177. General Geiger authorized the 77th Division to use those portions within the zone of the 3rd Division in order to move supplies and equipment from Barrigada dumps to the new forward area.

In late afternoon, while he was reconnoitering the site of a new CP near Ipapao, the 77th Division chief of staff, Colonel Douglas C. McNair, was killed by a sniper.20 This incident grimly demonstrated the ease with which individuals and small groups of the enemy could avoid detection by mop-up forces.

The fact that many Japanese could hide out in areas supposedly secured by Army and Marine units was in part a result of enemy defensive tactics and American measures taken to combat them. Since 29th Division forces were concentrated along key roads and trails, 3rd and 77th Division attack plans were adapted to meet this situation. As a result, the approach of the 77th to Mt. Santa Rosa was made by means of a few strong battalion and

regimental columns, which smashed their way north through the jungle whenever trails were not available. On 6 August at 0900, General Turnage issued orders for the 3rd Division to advance in column along the roads and trails leading north, patrolling and mopping up for 200 yards on either side in dense vegetation, and to the edge of first growth in more open country. As was the case in the Army zone of action, contact between Marine assault units would be made at designated objectives, usually lateral trails or road junctions. The attack formations ordered by Generals Bruce and Turnage and approved by General Geiger were designed to keep maximum pressure on the Japanese and to deny the enemy any more time to build up his defenses.

Early on 6 August, before the 3rd Division altered its attack formation for a more rapid advance, the assault regiments made local attacks to straighten the front lines and reach a predesignated line of departure. The 9th Marines killed the few Japanese that were still alive in the ruins of the defenses along the Liguan road. On the division boundary, a tank-infantry patrol of Company G, 2/9 moved out to destroy an enemy roadblock on a trail leading into the 77th Division zone. Part of the defending force was a Japanese tank, which scored three hits on a Marine medium before being knocked out by return fire. Enemy infantry fled the roadblock and was hunted down by the Marine force, which killed 15 men before it turned back after reaching a point about 1,000 yards inside the Army zone.

At 1045, the 3rd Division moved out all across the front in what was essentially a series of parallel battalion columns. No longer deployed in skirmish line, the Marine units made great strides forward against minimal opposition. The 3rd Marines, with 3/3 in assault, moved ahead 5,000 yards, along the road to Ritidian Point. When Major Bastian’s lead units reached the day’s objective, the 2nd Battalion came up and extended to the left, while 3/3 moved to the right to contact the 21st Marines. After the new front line was occupied, 1/3 relieved the 3rd Battalion in position so that 3/3 could shift to the right and pass through 2/21 on 7 August. This realignment was a preliminary maneuver to the entry of the 1st Brigade into the attack to the north.

The 21st Marines, like the 3rd, shifted to a column of battalions when the new attack formation was ordered. With 2/21 in the van, the regiment moved 4,000 yards and reached its objective, a trail junction on the road to RJ 460 by 1300. Then the 1st Battalion moved up and extended to the right in rugged jungle terrain, while 2/21 contacted the 3rd Marines to the left. The 9th Marines, with 1/9 preceding 2/9, followed a small trail that was the trace of the division boundary to the point where the boundary veered sharply northeast toward the coast between Pati Point and Anao Point. At this turning, 1/9 moved to the northwest along a trail that angled in the direction of the positions held by the 21st Marines. The battalion set up for the night without having made contact with 1/21. For the first time in three days, however, the right flank battalion of the 3rd Division (2/9) was in visual contact with the left flank battalion

(1/306) of the 77th Division when the frontline units established their night defensive perimeters.

During the afternoon’s advance, corps headquarters passed the word that its operation plan for the attack against Mt. Santa Rosa would be effective at 0730, 7 August. General Shepherd was notified that his brigade would pass through the positions held by 2/3 and 1/3 and assume responsibility for an attack zone that included the western part of the island and the northern end from Ritidian Point to the village of Tarague. (See Map 30). Shepherd alerted the 4th Marines to make the relief of the 3rd Marines battalions and to move out in assault the following morning.

In its narrowed zone of action in the center of the island, the 3rd Marine Division was directed to continue its attack and to assist the 77th Division, which would be making the principal corps effort to destroy the remaining Japanese. Priority of fires of corps artillery and naval support ships was given the Army division. Targets assigned for morning strikes by Seventh Air Force planes were all picked with the aim of softening up the defenses of the key Santa Rosa heights. The heavy bombing and shelling of areas behind the enemy lines in northern Guam had been going on for days. As one Japanese survivor recalled the period, the bombardment was nerve-wracking and destructive, and often seemed all too thorough to the individual, since American aircraft:–

... seeking our units during daylight hours in the forest, bombed and strafed even a single soldier. During the night, the enemy naval units attempting to cut our communications were shelling our position from all points of the perimeter of the island, thus impeding our operation activities to a great extent.21

The Final Drive22

Before the 77th Division launched its final drive on 7 August, assault units of the 306th and 307th Infantry advanced to occupy a line of departure closer to the attack objectives. Twenty P-47s from Saipan strafed and bombed Mt. Santa Rosa as the infantrymen were moving out. The 306th Infantry plunged into the jungle, following trails that would skirt Yigo on the west, while the 307th guided on the road to the village and reached the last control point on its approach march by 0900. As the leading company of 3/307 was nearing this area, 600 yards from the road junction at Yigo, its men were harassed by small arms fire. The Americans deployed and poured a heavy volume of return fire into the thick brush ahead. Within an hour all opposition had faded away.

Once all units were in position on the designated line of departure, General Bruce issued orders for the general attack to begin at noon. In preparation, 10 B-25s roared in over the mountain dropping 120 100-pound bombs on the south slopes and firing 75 rounds at Japanese positions from nose-mounted

75-mm cannon.23 For an hour before H-Hour, support ships pounded the heights and possible enemy assembly areas, and then in the final 20 minutes before jump-off, seven battalions of artillery fired a preparation on defenses in the vicinity of Yigo. As the fire lifted on schedule and the assault troops warily advanced, supporting tanks had not yet made their way through the barrier of troops, trucks, and jeeps on the narrow, crowded road. At 1215, the light tanks caught up with the leading elements of 3/307 about 400 yards from the village and passed through the infantry front lines.

Overrunning and crushing several enemy machine gun positions, the lights topped a small rise where the ground was sparsely covered with brush. A seeming hurricane of enemy fire struck the armor from hidden positions ahead, and a radio call for help went out to the mediums. When the heavier tanks came up, a raging duel of armor and antitank guns ensued. With their freedom of action hampered by the jungle, the tanks were channeled into the fire lanes of enemy guns. Two lights were knocked out, one medium was destroyed and another damaged, and 15 tank crewmen were casualties before the short, furious battle was over. Infantrymen that tried to outflank the Japanese strongpoint by moving through the jungle, which crowded the road, were driven to cover by deadly and accurate machine gun fire.

Suddenly, the fight ended almost as quickly as it began, when the enemy force, 100-200 men, was soundly beaten by elements of 3/306. Moving from his position on the left flank toward the sound of the firing, and keying his location to the distinctive chatter of the enemy machine guns, the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Gordon T. Kimbrell, led a platoon of Company K through the jungle and rushed the Japanese position from the rear. Surprise was complete and the defenders were killed or routed. Other elements of 3/306 wiped out enemy infantry holding out closer to the village road junction. With the welcome aid of this flanking attack, which accounted for 105 Japanese, the 307th and its supporting tanks were able to sweep through the shell-pocked ruins of Yigo. As the 307th turned toward the mountain, 3/306 moved out up the road toward Salisbury. (See Map 30.)

The fighting near RJ 415 did not end until midafternoon, and when the two assault battalions of the 307th had moved into position to attack east, the day was already spent. On General Bruce’s orders, the 307th dug in about a half mile beyond Yigo and made preparations to renew the attack at 0730 on the 8th.

On the right of the division zone of action, the 305th Infantry spent another hard day cutting its way through the trackless jungle toward the mountain. Enemy opposition to both assault battalion columns was light, but the rate of advance was maddeningly slowed by the difficult terrain. The troops ended the day close enough to their objective, however, to get caught in the fringe of an afternoon bombing attack; 2/305 suffered several

casualties from a misdirected bomb. The 3rd Battalion of the 307th, strafed at about the same time, luckily escaped injury.

In an unexpected twist of fate, 3/305, in division reserve but under corps control, had one of the day’s hardest fights. It was ordered to clean out the area near the new 77th Division CP, where Colonel McNair had been killed on the 6th. A platoon uncovered an enemy strongpoint deftly hidden in the jungle about 500 yards from the headquarters camp. A fierce fire fight broke out. Elements of two rifle companies and a platoon of mediums were called up to surround the Japanese, estimated at company strength. Six hours of desperate close-quarter fighting followed before the defenders were wiped out at a cost of 12 Americans killed and 21 wounded.24

The column of 1/306, which advanced on the division left on 7 August, made good progress after the noon jump-off time. When its leading platoons reached a trail junction near the division boundary about 1500, they ran into a strongpoint built around two machine guns and manned by 40-50 Japanese. The fight to eliminate this opposition took much of the rest of the afternoon, with the result that the 1st Battalion set up for the night just on the edge of the area that corps maps showed as part of the 3rd Marine Division territory. If 1/306 had continued its advance, it would have encountered elements of the 9th Marines.

The 3rd Division assault troops met little enemy resistance on 7 August. With bulldozers and tanks breaking trail where none existed and attack formations narrowed to battalion columns, all three regiments reached and secured their objectives by midafternoon. They held up along a trail from RJ 460 to the boundary near the village of Chaguian, generally 5,000 yards forward of their line of departure.

On the right, 1/9 and 2/9 moved out in attack with the 1st Battalion in the fore. A few isolated enemy stragglers were killed, and signs of fresh tank tracks were found by patrols that scouted toward the 21st Marines, advancing in the center of the division zone. The 21st, with 3/21 in the van, found no fresh evidence of the enemy as it struggled forward along the scant tract of meandering trails. On the far left, 3/3 led the 3rd Marines attack along the road to RJ 460. At 0850, a few enemy artillery shells exploded among the advancing troops but with little effect. About two hours later, the Marines discovered the source of this fire when the tank-infantry point found a 75-mm gun posted to hold a roadblock. After a brief flurry of fire, the defenders fled to the north and the advance continued at a good pace. When it dug in for the night, the regiment was in contact with the 4th Marines on the left and the 21st Marines on the right. The favorable reports by the 3rd Marines of the day’s action added to an already optimistic picture at the 3rd Division CP. General Turnage ordered all assault units to continue their advance to the sea in the morning.

The situation in the 1st Brigade zone proved equally promising after the results of the advance on 7 August were evaluated. When the 4th Marines attacked along the roads to Ritidian

Army tanks hit and aflame during the attack of the Yigo village road junction near Mt. Santa Rosa. (USMC 92083)

Jungle foliage almost hides a Marine patrol from view as it nears Tarague on 9 August. (USMC 93894)

Point, its progress was so rapid that General Shepherd alerted the 22nd Marines to move forward behind the 4th, ready to join the assault as the zone widened to the north. At a trail junction about 2,000 yards short of RJ 460, Company L of 3/4, was fired upon by an enemy 75-mm gun, which wounded the company commander and two men. A supporting platoon of mediums quickly demolished the gun and a mortar position nearby, and blew apart the roadblock they had covered. Inexplicably, the Japanese gunner had fired three ineffectual rounds of high explosive at the tanks, although over 100 armor-piercing projectiles lay nearby.25 Aside from this brief encounter, little opposition developed. The 22nd Marines reached a position behind 1/4 on the left of the brigade zone in late afternoon, ready to move into the attack on order.

The capstone to the good news of 7 August was furnished by planes of MAG-21.26 During the day VMF-225 began flying routine combat air patrols from Orote, relieving Navy planes of this responsibility. At the same time, the Seventh Air Force command on Saipan was notified that Marine night fighters would take over all night air patrol duties. Although the Marine Corsairs and Hellcats were not slated to provide close support for ground troops, they could be called upon in that role if needed. With its own air defense garrison in operation, Guam was a long step forward in its development as a major Allied base for further moves against Japan.

Despite the cheering events of 7 August, none of the American commanders had any idea that the fight for the island was over. On the night of 7-8 August, it was the Japanese tanks, as it had been so often in the past few days, that added a fresh reminder of the enemy spirit. Harried by air attacks, artillery, and naval guns, the Japanese could not move any armor in daylight along major roads and trails, but at night, after the flock of Marine and Army observation planes had landed, the tanks could shift into attack position.

About 0300 on 8 August, the soldiers holding the northern sector of the 3/306 perimeter heard tanks rumbling down the road from Salisbury toward them. Three Japanese mediums with an undetermined force of accompanying infantry loomed out of the darkness, all guns blazing away. Alerted by the unmistakable clatter, the men of the 306th were ready and replied to the attack with every weapon they could muster. The enemy infantry was quickly driven off, one tank was knocked out by a rifle grenade and a second was stalled by heavy machine gun fire. The remaining medium abandoned the fight and towed the cripple away. Morning’s light showed the Japanese losses to have been 18 men, including 3 officers, and the cost to 3/306 for holding its ground, 6 men dead and 18 wounded.

Unshaken by this attack, the 3rd Battalion led the advance of the 306th on 8 August, heading cross-country by a narrow trail for Lulog. The few

Japanese encountered appeared to be dazed and shocked by the downpour of bombs and shells that had preceded the attack. By 1040, the battalion reached the village, and patrols headed for the coast on General Bruce’s order. In view of the slight opposition, the 77th Division commander had revised his plan for encircling Mt. Santa Rosa to include not only the movement of 1/306 along what was believed to be the division boundary to a blocking position at Salisbury, but also the advance of 2/306 through that village and on to the coast near Pati Point. As the 2nd Battalion, following its orders, approached Salisbury, Marine artillery shells hit along the column and wounded several soldiers, an unfortunate incident attributable to the confusion of boundary overlays in the hands of the two divisions. The swift protest of the violation of his supposed zone of action by Colonel Aubrey D. Smith of the 306th brought an equally prompt and sure reply from the neighboring 9th Marines. This exchange led to the discovery of the cause of the boundary confusion and its resolution by Colonels Smith and Craig.

Before the 306th proceeded further with General Bruce’s plan, the division commander saw a POW report—which later proved false—placing 3,000 Japanese in the area just north of Mt. Santa Rosa. A cautious view of this intelligence prompted Bruce to order 1/306 to close on the 3rd Battalion at Lulog and 2/306 to stand fast in reserve 1,200 yards northeast of Yigo, ready to close any gap between the 306th and 307th Infantry.

A strong reason for believing that major Japanese forces were located in the zone of the 306th lay in the results of the 8 August attack by the other regiments of the 77th Division. No significant enemy opposition was developed by the 305th Infantry as it neared its objective; the 307th eliminated 35 bombardment-dazed Japanese on the lower slopes of Mt. Santa Rosa, but found no one manning defenses on the bare upper reaches. Patrols to the sea by the 305th and 307th uncovered few signs of the enemy.

Under the circumstances, Colonel Smith ordered 2/306 to fill a gap between the 307th on the mountain and the rest of his regiment dug in near Lulog. In the course of this move, designed to block possible Japanese escape routes through dense jungle, elements of the 306th and 307th mistook each other for the enemy troops and exchanged artillery and tank fire. Ten casualties were incurred before the mistake was discovered. After this unfortunate mishap, the night was quiet.

Less than 600 enemy dead had been counted in the two-day fight for Yigo and Mt. Santa Rosa. Since intelligence officers had estimated a tentative garrison strength of 1,500 soldiers, 1,000 sailors, and 2,500 laborers in the 77th Division zone, it seemed probable that many Japanese had slipped away into the jungle. Although all 7 of the enemy artillery pieces thought to be part of the defense had been accounted for, only 5 of the 13 tanks reported in the vicinity had been knocked out.

Some enemy elements, which might have been units fleeing the Mt. Santa Rosa action, cropped up in the zone of the 9th Marines on 8 August as 3/9, moving along the trail from Salisbury

to the coast, met and overcame successive small pockets of resistance. By the time orders were passed to dig in, Major Bastian’s men had reached a point about 800-1,000 yards beyond Salisbury. At that village, 2/9, which was following the path taken by the 3rd Battalion, held up and established a strong blocking position. The 1st Battalion, in reserve, patrolled in the vicinity of Mt. Mataguac and killed 25 Japanese in scattered encounters. Colonel Craig, whose CP was located in the 1/9 patrol area close to the division boundary, notified the nearest Army unit that his men had sighted considerable enemy activity near a brush-covered hill just within the Army zone of action.27 Available intelligence indicated that the enemy headquarters might well be located in this area.

In the center of the 3rd Division zone, the 21st Marines passed into reserve at the start of the 8 August attack. Redrawn regimental boundaries pinched the 21st out of the front line, but gave it a large triangular patrol area, about 3,000 yards along each leg, to clear of Japanese. One patrol of the many threading their ways through the jungle discovered a truck, which contained the bodies of 30 Guamanians, who had been beheaded; in the same area, near Chaguian, 21 more bodies of natives, who had been as brutally murdered, were found the next day. Subsequent intensive investigation revealed that these victims had been impressed at the concentration camp near Yona to work on the defenses at Yigo. These gruesome discoveries spurred the Marines to a grim determination in their task of hunting down and eliminating the Japanese.

Although there were signs of recent Japanese activity throughout the jungled interior, particularly along the trails, relatively few enemy were found by the 3rd Marines moving northeast on the left flank of the division. The 3rd Battalion, which could follow a trail along the boundary, was able to make rapid progress. It reached RJ 460 and moved 1,500 yards further to the northeast before holding up for night defense. Patrols found their way to the cliffs overlooking the sea before returning to the perimeter for the night.

The 2nd Battalion was not so fortunate as the 3rd, for the trail it followed in the morning attack soon ended in a wall of jungle. A second trail which was supposed to intersect the first, a narrow pathway leading from Salisbury to the coastal village of Tarague, proved to be 1,300 yards away through the brush. Major Culpepper had no choice but to plunge ahead into the tangle, with relays of men cutting their way through the mass of vegetation, in order to reach his objective. All heavy weapons were left behind to come up with the bulldozers and tanks that followed the trace of the infantry column, building a wider trail, which could be used by trucks and jeeps. When 2/3 broke through to the Salisbury-Tarague trail, a patrol headed south to contact the 9th Marines. Not far from the new trail junction, an enemy blocking force was encountered and a fire fight broke out. When the last shots died away, 19 dead Japanese were found in the remnants of the enemy position, but it was too late to continue any further south, The patrol retraced its steps

and rejoined the battalion, which had moved north on the trail toward the coast. On Colonel Stuart’s order, 2/3, still minus its supporting weapons, dug in along the trail at a point roughly two miles north of Salisbury. (See Map 31.)

Helped by good trails that paralleled its direction of attack, the 1st Brigade reached the northern tip of Guam on 8 August. On General Shepherd’s order, the 22nd Marines moved into the line on the left at the start of the morning’s attack, relieving elements of 1/4. As the battalion columns advanced in approach march formation, there was little enemy resistance. Shepherd ordered 2/22 to send a patrol to Ritidian Point lighthouse, where air observers had reported Japanese activity. Company F drew the mission and advanced rapidly while carrier aircraft hit each successive road and trail junction to the front. By 1500, the company had reached Ritidian Point and had begun to work a patrol down a twisting cliff trail to the beach. A small force of Japanese tried to ambush the Marines but was easily eliminated. Following Company F, the remainder of 2/22 set up a defensive perimeter near Mt. Machanao. The 3rd Battalion dug in on the road about halfway between RJ 530 and RJ 460.

The 4th Marines, experiencing little difficulty in seizing the day’s objectives, set up night defenses in a series of perimeters, which stretched from the position held by 3/22 back down the road to RJ 460 and thence along the trail to Tarague as far as the defenses established by 3/3. Vigorous patrolling during the day had located few Japanese in the brigade zone of action. That night in a surprisingly honest broadcast, that might almost have been a IIIAC situation report, Radio Tokyo announced that American forces had seized 90 percent of Guam and were patrolling the remaining area still held by the Japanese.

Emphasizing the closeness of the end on Guam, IIIAC had placed restrictions on the use of supporting fires since 7 August. On that day, corps headquarters cancelled all deep support naval gunfire missions except those specifically requested by the brigade and divisions. Those headquarters could continue call fire on point and area targets, but had to coordinate closely and control each mission precisely. The last strike by Saipan-based P-47s was flown on the afternoon of the 7th. B-25s made their final bombing and strafing runs on Ritidian Point targets the next morning.28 After the strikes in support of 2/22 approaching the northern tip of the island, carrier planes were placed on standby for possible supporting strikes but never called. For the last stages of the campaign, artillery was the primary supporting weapon, and battalions of brigade and division howitzers displaced forward on the 8th in order to reach firing positions that would cover the stretches of jungle that remained

Map 31: Schematic Sketch of Japanese Tank Action in 3rd Marines Zone, 8-10 August

in Japanese hands.

On the night of 8/9 August, the center of action was the position occupied by 2/3 on the Salisbury-Tarague trail. At 0130, enemy mortar fire crashed down in the perimeter, heralding a tank-infantry attack launched from the direction of Tarague. The Marines immediately took cover off the trail and opened fire with every weapon they had. The fury of defending fire succeeded in annihilating the Japanese riflemen. The tanks continued firing and edged forward without infantry support when bazooka rockets and antitank rifle grenades, both in poor condition from exposure to the frequent rains, proved ineffective against the Japanese armor.

At 0300, when three enemy mediums had advanced into the midst of his position, Major Culpepper ordered his company commanders to pull their men back into the jungle and to reassemble and reorganize in the woods behind his CP.29 Miraculously, a head count taken 45 minutes later when the companies had found their ways through the dark jungle showed that there were no American casualties despite the prolonged firefight. Culpepper radioed Colonel Stuart of his actions, and as dawn broke, 2/3 struck out cross-country, cutting a trail toward the positions held by 3/3. (See Map 31. )

As his 2nd Battalion fought its way through the jungle, Colonel Stuart, whose CP was located in the 3/3 perimeter, bent every effort toward getting heavy weapons onto the trail where the Japanese tanks were last reported. Bulldozers plowed their heavy blades through the thick growth and tanks followed, crushing or knocking down all but the biggest trees. By noon, a rugged track usable by tanks and antitank guns was cut through to the Salisbury-Tarague trail. Leaving a blocking force at this junction, 3/3 moved south with tank support toward the scene of the night’s action. The enemy mediums had disappeared, however, and 3/3 set up where 2/3 had dug in the night before. At 1500, 1/21, which had been attached to the 3rd Marines the night before, was ordered to move up to the trail and advance toward Tarague. When the battalion received the word to set up for the night, it was 1,500 yards from the coast. At the other end of the trail, 3/21, operating under regimental control, set up a blocking position at Salisbury. Completing the picture of a day of maneuvering to trap the enemy tanks, 2/3 reached the division boundary road after a hard trek through the jungle and established a night perimeter where 3/3 had been located on 8 August. (See Map 31.)

While the 3rd Marines concentrated its efforts on destroying the Japanese armor, the 9th Marines advanced to Pati Point. With 2/9 leading, followed by 1/9, the regiment attacked along a trail on the division boundary and patrolled every intersecting path. The 3rd Battalion in reserve sought the Japanese as aggressively as the assault units. About 1030, one of 3/9 patrols fought the day’s major action when it discovered a trail-block built around a light tank and two trucks. A sharp, brief battle eliminated all opposition and accounted for 18 Japanese.