Chapter 3: Assault Preparations

Training and Rehearsals1

The Pacific-wide dispersion of troops and shipping assigned to ICEBERG prevented the Tenth Army from conducting either training or rehearsals as a cohesive unit. Because of the vast distances separating General Buckner and his corps and division commanders, the latter were invested with the responsibility for training their respective organizations along the lines of Tenth Army directives. With these orders as a guide, all Marine units committed to the operation were trained under the supervision of FMFPac.

Assault preparations of ICEBERG Army divisions were hindered by the limited time available for their rehabilitation, reorganization, and training. This was especially true in the case of XXIV Corps units already in combat in the Philippines. Many of the garrison and service units which were to be attached to the various assault forces were also handicapped by the time factor because they, too, were either fighting or heavily committed in support of operations in the Philippines. In order that Tenth Army staff planners could better evaluate the combat readiness of all organizations within the command, each of General Buckner’s commanders submitted a monthly training status report to ICEBERG headquarters on Oahu.2 Since the reports lacked what an inspection at first-hand could provide, Buckner and some of his principal staff officers made a series of flying trips to each of the corps and divisions. These personal visits at the end of January 1945 “did much to weld the far-flung

units of the Tenth Army into a unified whole.”3

One determinant forcing the postponement of the Formosa–South China invasion in favor of the Okinawa assault had been the shortage of service and support troops, a shortage that still existed when the Tenth Army began its final training and rehearsal phases.4 Many of these specialist units were slated to reinforce corps and divisions for the assault and then to augment Island Command during the initial base development. Because they were too deeply involved otherwise, often with primary missions related to the build-up for the operation, the support troops could not train with the assault units they were to reinforce. The time borrowed for training would seriously disrupt the mounting and staging efforts for ICEBERG. Nevertheless, support unit commanders carried out adequate individual weapons’ qualification and physical conditioning programs which met Tenth Army training requirements. Although they were released to General Buckner’s control only a few days before mounting for the target, a number of garrison organizations were able to conduct limited training with the combat outfit to which they were attached.

The major assault components of the Tenth Army were battle-experienced for the most part, but they needed to undertake an intensive training schedule in order to bring veterans and newly absorbed replacements alike to peak combat efficiency. To accomplish this task, Army and Marine Corps units in the South Pacific, and the 2nd Marine Division on Saipan, conducted extensive programs which fulfilled the training requirements stipulated by General Buckner’s directives. General Hedge’s XXIV Corps, however, was engaged in operations on Leyte, and his divisions were not released to Tenth Army by General MacArthur until 10 February 1945,5 just two months before L-Day.

After the extended period of bitter fighting in the Philippines, however, the combat units slated for ICEBERG were understrength. General Hodge’s problems were further aggravated when his infantry divisions were required to furnish

the Leyte Base Command6 with large working parties as soon as the troops returned from mopping-up operations at the front. The servicing, crating, and loading of organic division equipment siphoned off the services of other infantrymen as well as making it impossible to impose a major training program on any of the divisions. Finally, as one command reported, the “deterioration of the physical and mental condition of combat personnel after 110 days of continuous contact with the enemy made it plain that rigorous field training in the wet and muddy terrain would prove more detrimental than beneficial.”7

Besides undertaking the many other incidental duties preparatory to mounting for Okinawa from Leyte, some Army units had to construct their own camps and make their own billeting arrangements as soon as they arrived in the rear area from the front lines. What little time was available to the Southern Landing Force before L-Day was divided between training in small-unit tactics and practice for breaching and scaling operations, in anticipation of the conditions to be found at Okinawa beaches. Because of the large influx of raw replacements into the divisions, great emphasis was placed on developing the teamwork of riflemen and their supporting weapons.

Of the three divisions in XXIV Corps, the 96th was the most fortunate in that some of its new troops arrived during mopping-up stages on Leyte. At that time, the replacements were given an opportunity to take an “active part in combat and reconnaissance patrols, gaining valuable battle indoctrination through physical contact and skirmishes with small isolated groups of Japanese.”8

According to the Tenth Army Marine Deputy Chief of Staff, General Smith:–

The conditions of the Army divisions on Leyte gave General Buckner considerable concern. This was not the fault of the divisions; they were excellent divisions. However, they had been in action on Leyte for three months and two of the divisions were still engaged in active operations. The divisions were understrength and adequate replacements were not in sight. There were [numerous men suffering from] dysentery and skin infections. Living conditions were very bad. A considerable number of combat troops had been diverted to Luzon and converted into service troops. There was some doubt as to whether re-equipment could be effected in time.9

The fighting record of the XXIV Corps on Okinawa indicates how well it overcame great obstacles in preparing for its ordeal. Once they had reconstituted their combat organizations, trained their fresh replacements, and attended to the many details incident to mounting for the target, the veteran units of this corps were able to give good accounts of themselves against the enemy.

In the South Pacific and the Marianas, Tenth Army units were not as heavily committed as the units of the Southern Landing Force, and completed a more comprehensive training program.

The 27th Infantry Division, ICEBERG floating reserve, arrived at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides from Saipan during September and October 1944. The division was undivided in its opinion that this base was a “hellhole” unfitted for the division’s rehabilitation and training because of the island’s torrid climate, its topography, and lush, tropical vegetation.10

Upon receipt of advance information that it was to take part in the Okinawa assault, the 27th instituted an accelerated combat training program which was calculated to qualify it, by 30 January 1945, for a period of prolonged operations against the enemy. Launched on 23 October, the level of the program advanced progressively from individual schooling to combined company and battalion exercises and, finally, to a two- week stretch of regimental combat team (RCT)11 maneuvers. During this staging period, in which 2,700 replacements arrived and were assigned, the division stressed training for offensive and defensive night operations.

Most Marines in IIIAC assault divisions had recently been in combat, yet their training programs were stringent and comprehensive. Like all other veteran ICEBERG forces, the Marine divisions were confronted with the need to obtain, integrate, and train replacements. Marine training overall emphasized the development of a tank-infantry-artillery team and focused attention on tactical innovations such as the use of the armored amphibian’s 75-mm howitzer for supplementary artillery support. While other Tenth Army units were required to undertake amphibious training, General Geiger’s troops did not have to, since General Buckner considered his Marine divisions eminently qualified in this aspect of warfare.

Following the Peleliu campaign, General del Vane’s 1st Marine Division had returned to Pavuvu for rest and rehabilitation. The division was first based on the island in April 1944, arriving there after completion of the New Britain operation. At that time, and with some difficulty, the Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester veterans converted the overrun coconut groves into some semblance of a habitable cantonment. Because of its small size, Pavuvu was not particularly suited for training as large a unit as a division; its terrain limited the widespread construction of machine gun and mortar firing ranges.12 All artillery firing had to be conducted on Guadalcanal.

ranks of the 1st held some 246 officers and 5,600 enlisted Marines who had already served overseas nearly 30 months. Within that time, the division had made three assault landings and it was now to make a fourth. If the division was to go ashore at full strength, it appeared, at first, that it would be necessary for the veterans of Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu to fight at Okinawa too. A potentially serious morale problem was alleviated when the division received four replacement drafts by 1 January. These drafts, plus a steady flow of individual replacements, brought officer strength to slightly above the authorized figure and exceeded the authorized enlisted strength figure by more than 10 percent. As a consequence, all eligible enlisted Marines were able to return to the States.

At the same time, an extensive leave program was established for officers who, though eligible, could not be spared for rotation. Fifty-three of them were permitted to take 30 days leave in the United States, after which they were to return to Pavuvu. “In addition, six went to Australia and one to New Zealand. Some fifty key enlisted men [eligible for rotation] also elected to take leave in Australia in order that they could continue to serve in the First Marine Division.”13 By the time the division embarked for Okinawa, approximately one-third of its Marines had been in two invasions, one-third had faced the enemy once, and the remainder were men who had seen no combat whatsoever. The majority of the latter were replacements who had arrived at Pavuvu while the 1st was at Peleliu.

As soon as the training cycle of General del Valle’s infantry units reached the regimental level and outgrew Pavuvu’s facilities, each RCT was rotated to Guadalcanal, about 65 miles to the southeast, for two weeks of more intensive combined-arms training. Special emphasis was given to preparing the division for warfare of a type and on a scale differing in almost every respect from that which it experienced in the tropical jungles of Guadalcanal and New Britain, and on the coral ridges of equatorial Peleliu. As an integral part of a much larger force, this division was to invade, for the first time, a land mass “which contained extensive road nets, large inhabited areas, cities and villages, large numbers of enemy civilians, and types of terrain”14 not found in the South Pacific. Besides being schooled to fight under the conditions anticipated at Okinawa, the troops were trained to defend against paratroop attack and indoctrinated in the techniques of dealing with hostile civilians.

In commenting on the personnel situation of his regiment during its training period, the former commanding officer of the 11th Marines stated:–

The heavy casualties suffered at Peleliu, plus the rotation without immediate replacement of all officers and men with 30 months’ service in the Pacific after that battle, posed a severe problem. Only one battalion commander remained of the four who went to Peleliu. There were only eight field officers in the regiment including myself and the [naval gunfire] officer. Fourteen captains with 24 months’ Pacific

service were allowed a month’s leave plus travel time in the United States, and they left Pavuvu at the end of November and were not available for the training maneuver at first. I recall that the 4th Battalion (LtCol L. F. Chapman, Jr.) had only 18 officers present including himself. He had no captains whatever, The other battalions and [regimental headquarters] were in very similar shape. The 3rd Battalion had to be completely reorganized due to heavy casualties on Peleliu and was the only one with two field [grade] officers. But it had only about 20 officers of all ranks present.15

General Shepherd’s 6th Marine Division was activated on Guadalcanal in September 1944, and was formed essentially around the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. This unit had taken part in the Guam invasion and had been withdrawn from that island late in August. The infantry components of this new division were, with a few exceptions, veterans of the Pacific fighting. The 4th Marines was made up of the disbanded Marine raider battalions, whose troops had fought on Guadalcanal, New Georgia, and Bougainvillea; the infantry regiment as a whole had landed on Emirau and Guam. The 22nd Marines had participated in the Eniwetok and Guam campaigns, and the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines had augmented the 2nd Marine Division for the Saipan assault. After its relief on Saipan, 1/29 was sent to Guadalcanal to await the arrival from the United States of its two sister battalions, and eventual assignment to the 6th Division.

At the time of the 6th Marine Division activation, the division was some 1,800 men understrength and, as was the case with other IIIAC units, in very few instances did the classification of the replacements received by General Shepherd, correspond to his actual needs. Paralleling other instances, where the composition of stateside-formed replacement drafts did not satisfy critical shortages in specific specialist fields, the 15th Marines was assigned and forced to retrain antiaircraft artillerymen from disbanded defense battalions whose previous experience and training was not considered the same as that needed by field artillerymen.

Most of the men in the 6th Division had fought in at least one campaign, while others were Pacific combat veterans who were now beginning a second tour of overseas duty. The division was based on Guadalcanal, where kunai grass and steaming tropical jungle provided an excellent environment in which General Shepherd’s men could fulfill a rugged training schedule. The program began on 1 October and proceeded from small-unit exercises through large-scale combined-arms problems employing battalion landing teams (BLTs)16 and RCTs; all training culminated in an eight-day division exercise in January 1945. Anticipating how the division was to be employed on Okinawa, General Shepherd emphasized the execution of large-unit maneuvers, swift movement, and rapid troop deployment.

The IIIAC Artillery faced the same replacement retraining problems that plagued the 15th Marines. When the 6th 155-mm Howitzer Battalion and the

Headquarters Battery, 2nd Provisional Field Artillery Group, were formed in October and November 1944, their cadres were withdrawn from existing units of corps artillery. The latter was further drained when 500 combat veterans, mostly valuable noncommissioned officers, were rotated home in November. There were few experienced artillerymen in the group replacing them.

At the same time that rehearsals were being conducted for the coming operations, Brigadier General David I. Nimmer’s Corps Artillery battalions were forced to conduct training sessions (retraining classes in the case of radar technicians and antiaircraft artillerymen coming from disbanded defense battalions) in order to ensure that all firing battery personnel would be completely familiar with the weapons to which they were newly assigned. Another matter adversely affecting the artillery training program was the delay, until 15 November and 10 December respectively, in the return of the 3rd 155-mm Howitzer and the 8th 155-mm Gun Battalions from the Palaus operation. General Nimmer’s organizational and personnel problems were complicated further by the fact that approximate y 10 percent of his unit strength joined after active training ended in February, while 78 communicators and 92 field artillerymen did not join until after Corps Artillery had embarked for Okinawa.

VMO-7, the Marine observation squadron assigned to Corps Artillery, did not arrive before General Nimmer’s units mounted out, but joined them later at the target. Three days before embarkation, the commanding officer of the 2nd Provisional Field Artillery Group joined. Despite these hitches to IIIAC Corps Artillery precombat preparations, General Nimmer considered all of his embarked artillery units ready, although “both individual and unit proficiency were not up to the standards that could have been obtained under more favorable circumstances.”17

As soon as General Geiger’s staff began planning for the Marine Corps role in ICEBERG, the commanders of the IIIAC Corps Artillery and the 11th and 15th Marines established liaison with one another in order to coordinate their unit training programs. These senior Marine artillery officers “resolved that in this operation we would take advantage of all previous experience, good and bad, and give a superior performance. Accordingly, great care was given to ... the ability to rapidly mass fires of all available guns at any critical point.”18

Artillery training was directed toward attaining this capability. General Nimmer’s staff devised and wrote the standard operating procedures to be used by all Marine artillery units assigned to ICEBERG. These procedures established the techniques to be used for requesting and the subsequent delivery of reinforcing fires. During the training period, firing batteries constantly put the new doctrine into practice.

With the exception of the 12th Marines, the 2nd Marine Division artillery regiment, all other Marine artillery units in the Tenth Army conducted a

combined problem on Guadalcanal, 11–13 January. A majority of the firing missions were spotted by aerial observers. Conditions anticipated on Okinawa were simulated as closely as possible, although the large military population and the consequent profusion of various installations on Guadalcanal necessarily limited the size of the artillery ranges available for the big guns. By the end of the combined problem, when a firing mission was called in, the Marines “were able to have all artillery present, laid and ready to fire in an average of five minutes from the time it was reported.”19

General Watson’s 2nd Marine Division, reserve for IIIAC and its third major element, was in garrison on Saipan where a division-wide training program was effectively integrated with mopping-up operations against enemy forces remaining at large on the island. More than 8,000 Marine replacements received valuable on-the-job experience routing Japanese holdouts during the first months of the division training program which began 15 September. Saipan’s rapid build-up as a supply center and an air base restricted the training efforts of the division, however, and maneuver room and impact areas were soon at a premium.

In the course of his inspection trip to Tenth Army units, General Buckner visited the 2nd Marine Division. On the morning of 3 February, he trooped the line of the 8th Marines and then inspected the regimental quarters and galleys. It seemed to General Smith that the men of the 2nd Division looked very fit, and that they had made a tremendous impression on the Tenth Army commander. Buckner was particularly impressed with the battalion commanders, and told his deputy chief of staff that “he had never before had the privilege of meeting such an alert group. ...”20

A lack of suitable beaches on Saipan confined final division rehearsals to simulated landings only. Because of the indefinite nature of its employment once it had made the feint landings on L-Day and L plus 1, the 2nd Division had to select an arbitrary landing scheme of two RCTs abreast for the rehearsal pattern. Bad weather prevented LVT launchings on two days, neither air nor naval gunfire support was available, and, finally, on 19 March—the last day of the exercises—only the naval portion of TG 51.2 (Demonstration Group) was able to participate in the demonstration rehearsal.

On Espiritu Santo, the Tenth Army’s other relatively isolated unit—the 27th Infantry Division—conducted rehearsals from 20 to 25 March while its transport squadron was being loaded. This division was in the same position as General Watson’s in that it faced a profusion of potential missions. The rehearsals of both reserve divisions were

based, therefore, on a number of hypothetical landing assignments.

Satisfactory practice landings were made by all of the other Tenth Army assault divisions. IIIAC rehearsals took place off the Cape Esperance–Doma Cove beaches on Guadalcanal from 2 through 7 March. Although reefs do not exist here, a transfer line was simulated 200 yards from the shore in an attempt to duplicate actual landing conditions in the corps zone on Okinawa. During the six days of rehearsals, Rear Admiral Reifsnider’s staff officers made certain that assault wave control was emphasized and that the training of communications elements was intensified at all command levels.

Because naval gunfire and air-support units assigned to ICEBERG were committed elsewhere at this time, the token prelanding bombardment furnished by vessels in the area, and the air support supplied by F6Fs (Hellcats) and TBMs (Avengers), flying in from Henderson Field and nearby carriers, only approximated the tremendous volume of fire to be laid on the Hagushi beaches. Practice landings were made by IIIAC units on 3 March, followed the next day by a critique aboard the TF 53 flagship, USS Panamint. Other preliminary landings on the 5th preceded the landing of the entire IIIAC assault echelon on 6 March. Corps and division command posts were set up ashore, a primary communications net was established, and some equipment was unloaded. On 7 March, the reserve regiments—the 1st Marines for the 1st Division and the 29th Marines for the IIIAC—climbed down the nets into invasion craft, which were formed into boat waves, and then landed on the beaches.

General Geiger’s corps artillery units did not participate in these final rehearsal exercises except to land battalion, corps, and group headquarters reconnaissance parties. The shortage of time prevented the landing of any of the artillery pieces which were to go ashore at the target.

Nearly 3,000 miles away from Guadalcanal, in the Philippines, assault elements of XXIV Corps conducted rehearsals in Leyte Gulf from the 15th to the 19th of March under the watchful eyes of Admiral Hall and his attack force staff officers. Because the missions assigned XXIV Corps divisions varied so widely, the nature and conduct of their rehearsals tended to reflect this variance.

The 77th Infantry Division was to make the initial ICEBERG assault, the landing on Kerama Retto. In order to familiarize the troops with conditions at their impending target, practice landings were made in southeastern Leyte’s Hinunangan Bay on islands that closely resembled some of those in the Keramas. For two days, 14 and 15 March, adverse weather conditions and heavy swells prevented any landings at all, but adherence to any firm rehearsal schedule was not considered necessary since the mission of the 77th involved several landings independent of each other.

Poor weather on the 15th forced the cancellation of a planned rehearsal for the Ie Shima invasion, while only the division reserve (307th Infantry) made any practice landings on the 16th. Although General Bruce was satisfied with the rehearsals since “all elements

scheduled for a specific mission satisfactorily executed a close approximation of their mission,21 Admiral Kiland was not so confident. The Western Islands Attack Group Commander felt that “considering the complexity of the operation and the relative inexperience of naval personnel involved, the curtailment of these exercises by weather conditions made the training provided entirely inadequate.”22

On 16 March, the 7th and 96th Divisions landed under perfect weather conditions and on the 18th held unit critiques, in which certain basic discrepancies and difficulties discovered in the first exercise were ironed out. The following day, the two divisions landed again. A high-level critique was held on the 21st for the major Army and Navy commanders on Admiral Hall’s flagship, USS Teton. Also present were Admiral Turner and General Buckner. At this time, all of the XXIV Corps rehearsals were evaluated, and efforts were made to ensure that the actual landing would be better coordinated.

As the normal duties of most of the flying squadrons assigned to TAF constituted their combat training, and since they would not begin operations at Okinawa until after the landing, when the airfields were ready, they were not rewired to conduct rehearsals for ICEBERG. TAF ground personnel scheduled to travel to the target with the assault echelon, participated in the landing rehearsals that were held at Guadalcanal and Leyte. Their troop training, for the most part, was conducted aboard ship en route to the staging areas, and consisted of familiarization lectures about the enemy, his tactics, and his equipment.

Like the other Okinawa-bound Tenth Army units mounting from Pearl Harbor, Island Command troops conducted individual and unit training programs which consisted of specialist as well as combat subjects. The Island Command assault echelon was composed chiefly of headquarters personnel who were to initiate the base development plan as soon as practicable after the landing. Within this echelon also were shore party, ordnance, ammunition, supply, signal, quartermaster, truck, and water transportation units, whose support services would be required immediately after the initial assault.

At Fort Oral, California, officers to staff military government teams began assembling in late December 1944. A number of these officers had already received approximately three months of military government training at either Princeton or Columbia Universities. In California and at the staging areas where they joined the assault forces., these Army and Navy officers received instructions pertinent to the ICEBERG military government plan. Many in the Navy enlisted component in the military government section had never received any specialized civil affairs training before they arrived at Fort Oral, where they were assembled just in time to embark with the teams to which they were assigned.23

By 1945, the roll-up of enemy positions in the Pacific had progressed to the point where some Tenth Army units were able to mount and stage on the threshold of Japan. XXIV Corps prepared for Okinawa in the Leyte Gulf area, only 1,000 miles from the Ryukyus, while in the Marianas, just slightly farther away from the target, other ICEBERG forces made ready for the attack. Northern Attack Force units, however, had a considerably longer journey to the Ryukyus as they prepared in the Solomons.

Mounting and Staging the Assault24

Each attack force of the Joint Expeditionary Force was organized differently for loading, movement, and unloading at the target. The nine transport divisions in the three transrons of Admiral Hall’s Southern Attack Force were reorganized and expanded to number 11 transport divisions (transdivs). Assigned to these two additional transdivs were those ships slated to lift XXIV Corps troops at Leyte and those which were to load Tenth Army and Island Command forces waiting on Oahu. The Northern Attack Force, which was to carry IIIAC troops, was not so augmented. General Geiger was so impressed with how well the reorganization of Admiral Hall’s transport force had eased movement control and increased the efficiency of loading and unloading operations, that he requested the formation of a similar corps shipping group for future IIIAC operations.25

The commanding generals of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions were made responsible for the loading and embarkation of their respective organic and attached units, while IIIAC itself supervised the loading of corps troops. In addition, General Geiger was responsible for embarking Marine Air Group 33 (MAG-33) of TAF, which was based on Espiritu Santo, 555 miles southeast of Guadalcanal.

Although some Northern Attack Force vessels were partially combat-loaded before the rehearsal period, all required additional time off the Guadalcanal, Banika, and Pavuvu beaches to take on vital cargo and to top-off water and fuel tanks. The Northern Tractor Flotilla was the first increment of TF 53 to leave the Solomons for the staging area at Ulithi. Departing on 12 March, the holds and above decks of the landing ships in the convoy were solidly packed with amphibious vehicles, tanks, artillery, and various other combat gear. For this invasion, IIIAC wanted to avoid subjecting assault troops to the crowded conditions and debilitating effects of prolonged confinement aboard LSTs and LSMs.

While APAs were hardly luxurious, their accommodations were far better than those of the landing ships. To ease the first leg of the journey to Okinawa,

many assault wave Marines were embarked on the faster attack transports which, together with the rest of the Northern Attack Force transport groups, left from the mounting area on 15 March to join the ICEBERG force gathering at Ulithi.

The immense lagoon at Ulithi Atoll was the westernmost American fleet anchorage, staging base, and repair depot in the Pacific. Midway between the Marianas and the Palaus, Ulithi was captured without opposition in September 1944, and was developed immediately to support naval operations in the western Pacific as well as to serve as an advance base for the Philippines invasion. Once occupied and built up, the islets of the atoll served also as limited recreation areas where personnel of all services could regain their land-legs and participate in a somewhat restricted physical conditioning program.

On 21 March, both the transport group and the tractor flotilla of TF 53 arrived at Ulithi, anchored, and on the following day, APA-borne assault troops were transferred to the landing ships which were to carry them the remaining 1,400 miles to Okinawa. Once the transfer was completed, small boats began ferrying recreation parties ashore. Here the rigors of shipboard confinement were forgotten by a combination of organized athletics and an issue of not-too-cool cokes and beer.

For many of the troops, this stopover on the long voyage towards the unknown was made exciting by the fascinating sight of the constantly shifting fleet groupment whose makeup changed from day-to-day and hour-to-hour as carriers, battleships, cruisers, and smaller combat vessels departed for strikes against the enemy or returned from completed missions. In the midst of this activity, the scattered elements of the Expeditionary Troops filtered in to join those forces which had arrived earlier.

Despite the relaxing effect of sun, sand, and surf at Ulithi, the nightly alerts to the presence of Japanese snooper planes was a continual reminder that a war still existed. This grim fact was brought home to many men in the invasion force on the gloomy, fog-bound Saturday afternoon of 24 March when the battered carrier Franklin limped into the anchorage shepherded by the USS Santa Fe.

On the next day, a brilliantly sunlit Sunday, the bruised and battered Franklin could be seen more clearly as she lay at anchor. Her top rigging, aerials, and radar towers were gone or twisted completely out of shape. Her flight deck was buckled and undulating. These were the external damages wrought by the internal explosions of bombs that had penetrated to lower decks when Japanese suicide planes furiously attacked the carrier on 19 March, during TF 38 strikes against enemy shipping at Kure and Kobe. As the most heavily damaged carrier to be saved in the war, the Franklin was able to make the 12,000-mile trip to New York for repairs under her own power, stopping only at Pearl Harbor on the way.

The Northern Tractor Flotilla sortied from the Ulithi anchorage for Okinawa on 25 March and, two days later, the remainder of the assault echelon set forth in its wake. Saipan was the scene,

on the same dates, of the Demonstration Group departure.

Loading operations of the 2nd Marine Division were eased by the fact that its lift, Transron 15, had laid over briefly at Saipan in February while en route to Iwo Jima. At that time, division transport quartermasters (TQMs) obtained ships’ characteristics data which proved more accurate than the information provided earlier by FMFPac. As a result, the TQMs were better able to plan for a more efficient use of cargo and personnel space.

In addition to the responsibility for loading his reinforced division, General Watson was given the duty of coordinating the loading of all ICEBERG Marine assault and first echelon forces elsewhere in the Marianas and at Roi in the Marshalls.26

In preparing for Okinawa, the only real problem confronting General Mulcahy’s Marine air units was the coordinated loading of ground and flight elements. According to the logistical planning, planes and pilots were to be lifted to the target on board escort carriers, while ground crews and nonflying units were to make the trip in assault and first echelon shipping. AS the organizations comprising the Tactical Air Force were widely dispersed, their loading and embarkation was supervised, of necessity, by local commanders of the areas where the air groups and squadrons were based.

Mounting from Oahu in the TAF assault echelon were the headquarters squadrons of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing and MAG-43, and Air Warning Squadrons (AWSs) 7 and 8. Headquarters Squadrons 2 and 43 became the headquarters commands of TAF and General Wallace’s Air Defense Command, respectively, The TAF transport quartermaster coordinated the mounting out of the Oahu-based units with his opposite numbers on the staffs of the Tenth Army and the 2nd MAW. The Marines from AWS-8 and the forward echelons of Mulcahy’s and Wallace’s headquarters commands left Pearl Harbor on 22 February, while AWS-7 departed Pearl the same month in two increments, one on the 10th and the second on the 21st.

Colonel John C. Munn’s MAG-31 embarked from Roi and Namur in the Marshall Islands. The group service squadron and ground personnel of Marine Fighter Squadrons 224, 311, and 441 boarded transport and cargo vessels which, in turn, joined the ICEBERG convoy forming at Saipan. Flight personnel and their planes went aboard the escort carriers Breton on the night of 22–23 March, Sitkoh Bay on 24 March and were staged through Ulithi where they were joined by Marine Night Fighter Squadron 542.

MAG-33 (Colonel Ward E. Dickey) mounted from Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. While IIIAC was responsible for the embarkation of the MAG, the group itself supervised the loading of its ground and service elements which joined the Northern Attack Force off Guadalcanal. The pilots of VMF-312, -322, and -323 flew their F4Us (Corsairs) to Manus via

Guadalcanal and Green Island. There they boarded the escort carriers White Plains and Hollandia. Already on board the latter was VMF(N)-543 which had boarded the vessel at Pearl Harbor on 11 March. Its ground personnel had departed from the same port three weeks earlier.

Outside of the TAF chain of command, but closely related to its combat functions, were Landing Force Air Support Control Units 1, 2, and 3. Two weeks after returning to its Saipan base from the Iwo Jima operation, LFASCU-1 loaded aboard ship for an immediate return engagement with the enemy at Okinawa. The other two LFASCUs were based at Ewa, T.H., where they trained for ICEBERG, and mounted for the invasion in February 1945, later staging for the target through Leyte.

As it had no need for an intermediate staging area, the XXIV Corps departed for Okinawa directly from Leyte. General Bruce’s 77th Infantry Division, which was to open the Ryukyus operation with the assault on Kerama Retto, finished loading its landing ships on 18 March and its transports on the 20th, each echelon leaving for the target on the day following. The 7th and 96th Divisions conducted their own loading under the supervision of XXIV Corps TQMs, who spotted Southern Landing Force shipping at the most satisfactory point on the landing beaches. The Southern Tractor Flotilla departed Leyte during the morning hours of 24 March; the transport groups followed three days later.

By the evening of 27 March, all ICEBERG assault elements were at sea, converging on Okinawa. Soldiers and Marines aboard the transports and landing vessels had already made themselves as comfortable as possible under the crowded conditions and had settled down to shipboard routine. Officers and key NCOs reviewed their unit operation plans, examined maps and terrain models of the landing area, and held daily briefing sessions with their men. At the same time they squared away their combat gear for the invasion, most of the men of Hebrew and Christian faiths also prepared themselves for religious observances of Passover or Good Friday and Easter, all three holidays falling within a few days of each other in 1945.

Neutralizing the Enemy27

After the first carrier strike of 10 October 1944,, Naha’s fire- and explosion-gutted ruins furnished the Japanese defenders with visual evidence of the effectiveness of American naval air power and served as an ominous portent of the future. One observer, a Japanese soldier, complained in his diary that, “the enemy is brazenly planning to completely destroy every last ship, cut our supply lines, and attack us.”28

Okinawa was not visited again by Vice Admiral John S. McCain’s Fast Carrier Force (TF 38) until 3 and 4

January 1945, when, in conjunction with a heavy attack on Formosa, the Ryukyu and Sakashima Islands were also struck. Commenting on this raid, a Japanese replacement confided in his diary that “seeing enemy planes for the first time since coming to Okinawa somehow or other gave me the feeling of being in a combat zone.”29 The return of the Navy planes on 22 January reinforced his first impression and further shook his seeming complacency, as that day’s diary entry implied resentment. “While some fly around overhead and strafe, the big bastards fly over the airfield and drop bombs. The ferocity of the bombing is terrific. It really makes me furious. It is past 1500 and the raid is still on. At 1800 the last two planes brought the raid to a close. What the hell kind of bastards are they? Bomb from 0600 to 1800!”30

During January, TF 38 struck Formosa and the Ryukyus twice, and made some uninvited calls on South China coastal ports, all while covering the Luzon landings. After its last attack, the force retired to Ulithi where reinforcing carriers were waiting to join. On 27 January, the same day that Admiral Nimitz arrived at his new advance headquarters on Guam,31 the command of the Pacific fleet’s striking force was changed and Admirals Spruance and Mitscher relieved Halsey and McCain. When Mitscher’s carriers departed Ulithi on 10 February, it was in the guise of Task Force 58, which was destined to continue the work that TF 38 had begun.

As a diversion for the 19 February Marine landing on Iwo Jima, and to reduce the Japanese capability for launching air attacks against the expeditionary force, Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Force struck at the Tokyo area on 16–17 February and again on the 25th. In between these attacks, Mitscher’s planes and ships supported the Iwo assault from D-Day until the 23rd. at which time they sortied for the 25 February Tokyo strike. As TF 58 retired to Ulithi on 1 March, planes of Task Units 58.1, 58.2, and 58.3 photographed Okinawa, Kerama Retto, Minami Daito, and Amami O Shima, and bombed and strafed targets of opportunity. These three units returned to Ulithi on the 5th.

At the same time that the fast carriers were making their forays, American submarines and naval patrol bombers ranged the western Pacific taking a steadily increasing toll of Japanese shipping. The bottom of the China Sea was littered with the broken hulls and loads of enemy transports and cargo ships which never reached their destinations. Almost complete isolation of the Okinawa garrison was accomplished by mid-February 1945 through the combined efforts of Navy air and submarine forces. It soon became apparent to General Ushijima that his Ryukyus command stood alone since “communications between the mainland

of Japan and Formosa had been practically severed.”32

The neutralization and isolation of Okinawa was furthered by the continuous series of strategic air strikes on the Japanese industrial network by Army Air Forces bombers, which mounted attacks from bases in China, India, the Philippines, the Marianas, and the Palaus. Massive raids on the factories of the main islands as well as on outlying sources of raw materials hindered Japan’s ability and will to continue the war. Giant super-fortresses also rose from airfields in the southern Marianas in steadily increasing numbers to hit Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, and Kobe, widening the fire-swept circle around the expanse of previously devastated areas. During the interludes between carrier-plane attacks on the Ryukyus, B-29 appearances over Okinawa became so commonplace that the Japanese defenders referred to their visits as “regular runs.”33

With the approach of L-Day, the tempo of covering operations was accelerated throughout the Pacific. For its final strike on Japan prior to the Okinawa landing. TF 58 steamed out of the Ulithi anchorage on 14 March. Four days later, carrier-launched planes interdicted Kyushu’s heavily-laden airfields, and attacked installations on Shikoku and Honshu islands on the 19th. The task force did not escape unscathed this time, however, for the enemy was ready and retaliated with heavy counterstrikes during which the Japanese pilots displayed reckless abandon and a wanton disregard for their lives. Five carriers and other ships in the task force were hit hard. A temporary task group composed of the damaged carriers Wasp, Franklin, and Enterprise, the cruiser Santa Fe, and Destroyer Squadron 52 returned to Ulithi for necessary repairs, The ships remaining in TF 58, the carriers, the battleship force, and the protective screen, were reorganized into three task groups of relatively equal strength on 22 March. With this force, Admiral Mitscher then began the final run on Okinawa for the beginning of the preinvasion bombardments.

Pre-invasion Preparations and the Kerama Retto Landing34

The first elements of the ICEBERG force to appear at the target were the doughty sweepers of Mine Group One, which began operations off Kerama Retto and the southeastern coast of Okinawa on 24 March, just two days before the 77th Infantry Division was to land in the Keramas. After the minecraft cleared a channel outside the 100-fathom curve off the Minatoga beaches, part of Admiral Mitscher’s battleship force., temporarily organized as TF 59, steamed through the swept area and bombarded Okinawa while TF 58 planes covered and neutralized enemy shore

installations. By late afternoon, as TF 59 withdrew to rejoin the carrier force, the mine vessels finished that day’s planned program of preliminary sweeps.

During these operations, the Amphibious Support Force, with elements of the Gunfire and Covering Force (Admiral Deyo serving as Officer in Tactical Command), had completed the run from Ulithi and deployed into approach formation. Two fire support units left TF 54 to begin their respective assignments—one unit to cover the sweep conducted between Tonachi Shima and Kerama Retto, and the other to cover the mine sweepers off Okinawa and to begin bombarding the demonstration beaches. An important TF 52 element was the Underwater Demolition Flotilla, consisting of 10 underwater demolition teams (UDTs) organized into two groups, Able and Baker. On the afternoon of 24 March, the high speed destroyer transports (APDs) of Group Able and destroyers of TF 54 formed for the next day’s UDT and NGF operations at Kerama. The remainder of Admiral Deyo’s force was concentrated and ready to repulse all Japanese surface or air attacks.35

A carefully planned feature of the ICEBERG operation was this concentration of naval strength. With ample sea room and sufficient fighting power to eliminate any or all of the remnants of the Japanese Navy, TF 58 lay to the east of the Ryukyus in the Pacific Ocean. In the East China Sea,, to the west of Okinawa, the majority of the combat ships of the Amphibious Support Force was concentrated, ready to stop any attempt to reinforce or evacuate the garrison. At night, the ships assigned to the bombardment of Okinawa’s southeastern coast retired together so that their mission could be resumed without delay the following morning. In the event of any surface action, each of these task groups was able to operate and support itself independently.

As vaster areas surrounding Okinawa were swept clear of mines, destroyers and gunboats began patrol operations and made the beleaguered enemy’s isolation a certainty. Shipborne radar picket stations, disposed from 15 to 100 miles offshore, encircled the island to protect the invasion force from the constant threat of surprise enemy air attacks. Aboard the destroyers and destroyer minesweepers serving as picket vessels were fighter-director teams which controlled the combat air patrols (CAPs) of carrier planes which orbited overhead during the hours of daylight. When Japanese flights were detected on picket radar screens, the CAP was vectored out to intercept and destroy the enemy. The bulk of the heavy losses incurred by the Navy during the battle for Okinawa was borne by the vessels comprising the radar picket fleet. The value of their services in protecting the vulnerable transport

and service areas is measured by the large number of Japanese planes shot down before they had reached their objectives.

Although the destructive TF 58 raids on Kyushu had temporarily disrupted enemy plans for air attacks from the home islands, the Japanese managed to mount an increasing number of raids from fields in the Formosa area. Once it became apparent that Okinawa was to be invaded and that Okinawa waters held lucrative targets, forward elements of the 8th Air Division rose from their fields in the Sakashimas to make their first Kamikaze attack on ships standing off Kerama Retto at dawn on 26 March.36

Beginning with this first hour-long enemy air raid, the loss of lives and damage to ships mounted as Japanese bombers and suiciders made sneak attacks on the amphibious force in the dawn and dusk twilight hours.37 As part of its planned schedule of preliminary operations supporting ICEBERG, Vice Admiral Sir H. Bernard Rawling’s British Carrier Force (TF 57) struck Sakashima Gunto on the 26th and 27th. Since the carriers had blocked the use of Sakashima and Kyushu, the Japanese had to use Okinawa-based planes to attack the American invasion forces. The employment in three suicidal forays of all available aircraft, including trainers, liaison craft, and planes of a Special Attack Unit which managed to fly in from Kyushu, led to the complete elimination of the air strength of the Okinawa garrison by 29 March.38

Claims of enemy airmen who survived to return to home bases were grossly exaggerated, but their destructiveness was extensive. A summary of damages to American forces for the period 26 to 31 March reveals that six ships, including Admiral Spruance’s flagship Indianapolis, were crashed by suicide-bent enemy pilots. Near misses accounted for damage to 10 other vessels, while floating mines sank 2 ships and an encounter with a Japanese torpedo boat gave another American ship minor damage.

Despite costly harassment from Japanese air attacks, Admiral Blandy’s force proceeded with its primary task of preparing the target for the assault. Four Group Able UDTs cleared beach approaches in Kerama Retto on 26 March and began blowing Keise Shima reefs the next day. Because Okinawa’s offshore waters had not been completely cleared of mines, the reconnaissance and demolition work scheduled for the 28th was delayed a day. Elements of Group Able scouted the demonstration beaches on the 29th, while Group Baker teams reconnoitered the Hagushi beaches.

During this reconnaissance of the west coast landing area, Group Baker swimmers discovered approximately 2,900 wooden posts embedded in the reef near its seaward edge and stretching for some distance on either side of the Bishi Gawa. These posts, which were on the average six inches in

Landing craft form up for the run to Kerama Retto beaches on 26 March 1945. Viewed from USS Minneapolis. (USN 80-G-316830)

155-mm guns of the 420th Field Artillery Group are set up on Keise Shima to shell enemy main defenses prior to the Tenth Army assault landing. (USA SC205503)

diameter and from four to eight feet in height, were generally aligned five feet apart in rows of three or four. Although some of these obstacles were loose, a few were set in concrete and the rest wedged into the coral. On 30 March they were blown up with hand-placed charges. All but 200 posts were destroyed by L-Day and it was believed that the landing would not be hindered by those that remained.39

Accompanying the UDTs during the beach reconnaissance and initial demolitions operations were assault troop observers, who acted as liaison and reconnaissance personnel.40 Their primary function was to brief the UDTs on the schemes of maneuver and location of the landing areas of their respective assault units, to make certain that specific beaches were cleared, and to obtain current intelligence concerning the beaches and surrounding terrain. As soon as these preinvasion operations had been completed (29 and 30 March), the observers were returned by ship to join their parent organizations in the approaching attack groups. In general, the intelligence reports submitted by the observers favored a successful landing across the entire Tenth Army front.

Because the waters surrounding Okinawa had been heavily mined,41 the scheduled NGF bombardment did not begin until 25 March (L minus 7) when TF 54 fire support vessels were able to close to ranges of maximum effectiveness. Carrier air was able to pound Okinawa repeatedly, however, and was met by only ineffectual and desultory fire from enemy antiaircraft defenses. In the course of the 3,095 sorties that the TF 52 Combat Air Support Control Unit (CASCU) directed against Okinawa prior to L-Day, special attention was given to the destruction of submarine pens, airfields, suicide boat installations, bridges over the roads leading into the landing area, and gun positions. After the pilots were debriefed, each day’s strike results were evaluated by the CASCU on board Admiral Blandy’s flagship, USS Estes, and considered together with damage estimates of ships’ guns. The schedule of air missions and the NGF plans were revised and coordinated, and plans for the next day’s sorties and shoots were then issued.

Initial target lists compiled by the Tenth Army artillery section and TF 54 intelligence section were constantly revised as analyses, based on aerial observation and photo reconnaissance, were received. As new evaluations were made of the destruction of enemy positions and installations, and new targets tabulated, cards listing the corrected data were delivered to the target information centers (TICs) of IIIAC and XXIV Corps. From the time that the bombardment of Okinawa began until L-Day, General Nimmer’s TIC received copies of all dispatches sent from the objective by CTF 54. From these reports, all information relative to the discovery, attack, damage, and destruction

of targets in the IIIAC landing zone was excerpted and used to bring the target map and target file up-to-date.42

Although Admiral Blandy’s bombardment force expended 27,226 rounds of 5-inch or larger-caliber ammunition on Okinawa, extensive damage was done only to surface installations, especially those in the vicinity of the airfields. As the ground forces were to discover later, the Japanese sustained little destruction of well dug-in defenses, and few losses among the men who manned them. On the day before the landing, as a result of his evaluation of the effect of air and NGF bombardment, CTF 52 could report that “the preparation was sufficient for a successful landing.”43 Admiral Blandy also stated that “we did not conclude from [the enemy’s silence] that all defense installations had been destroyed. ...”44

A prerequisite which Admiral Turner felt would guarantee the success of ICEBERG was the seizure of Kerama Retto and Keise Shima prior to L-Day. Because of the advantages to be gained by all ICEBERG assault and support elements, the taking of these islands was made an essential feature of the Tenth Army operation plan. Naval units, particularly, would benefit since the Keramas provided a sheltered fleet anchorage in the objective area where emergency repairs, refueling, and rearming operations could be accomplished. Once the envisioned seaplane base was established, Navy patrol bombers could range from Korea to Indochina in search and rescue missions and antisubmarine warfare operations. With the emplacement of XXIV Corps Artillery guns on Keise Shima and their registry on Okinawa, preliminaries for the main assault would be complete.

Even if the Keramas had had no value as an advanced logistics base, they would have been taken. The suspected presence of suicide sea raiding squadrons in the island chain was confirmed when the 77th Infantry Division landed, and captured and destroyed 350 of the squadrons’ suicide boats. Their threat to the Okinawa landing was undeniable, for these small craft were to speed from their hideouts in the Keramas’ small islands to the American anchorages. Here, “The objective of the attack will be transports,, loaded with essential supplies and material and personnel ...” ordered General Ushijima. “The attack will be carried out by concentrating maximum strength immediately upon the enemy’s landing.”45 The surprise thrust into the Keramas frustrated the Japanese plan and undoubtedly eased initial ICEBERG operations at the Hagushi beaches. At the time that the 77th was poised to strike the Keramas, the islands were defended by approximately 975 Japanese troops, of whom only the some 300 boat operators

of the sea raiding squadrons had any combat value. The rest of the defense was comprised of about 600 Korean laborers and nearly 100 base troops.

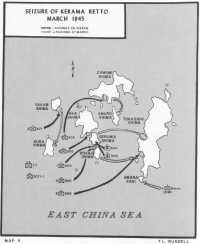

On 26 March, the day following the sweep of Kerama waters by the minecraft and reconnaissance of its beaches by UDT personnel, Admiral Kiland’s Western Islands Attack Group moved into position for the assault. A battleship, two large cruisers, and four destroyers had been assigned to provide NGF support for the landing, but only the 5-inch guns of the destroyers were used extensively. The capital ships were not called on to fire but remained on standby. As LSTs disgorged their cargo of armored amphibians and troop-laden assault tractors for the run to the beaches, carrier planes orbited the transport area to ward off Japanese suicide planes which were beginning to filter through the outer fighter screen. Aircraft bombed the beaches as the assault waves were guided toward the target by LCIs assigned to give close-in support.46 (See Map 5.)

At 0801, the first of the four assault battalions of the 77th hit its target and in a little over an hour’s time the other three had attacked their own objectives. Before noon, General Bruce saw that the rapid progress of his landing teams ashore would permit yet another landing that day, so he directed the 2nd Battalion, 307th Infantry, a reserve unit, to take Yakabi Shima. Since this island’s defenders offered little resistance, it was secured by 1341. By the end of the day the 77th had done quite well, having seized three Kerama islands outright and established a firm foothold on two others.

Within a six-day period, 26–31 March, at a cost of 31 killed and 81 wounded, the 77th Infantry Division completely fulfilled its mission as the vanguard of ICEBERG Expeditionary Troops. In the process of removing, the threat posed by the Japanese to operations in the Kerama anchorage, General Bruce’s troops killed 530 of the enemy, captured 121 more, and rounded up some 1,195 civilians. All of the enemy were not disposed of, however, for scattered Japanese soldiers remained hidden in the hills of the various Kerama islands and even occasionally communicated with units on Okinawa.47

Marine participation in pre-L-Day activities was confined to the operations of Major James L. Jones’ FMF Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion. For the Keramas invasion, it was split into two tactical groups, one under the battalion commander and the other under his executive officer. Only two companies of the battalion were available for anticipated missions, since Company B had been assigned to the V Amphibious Corps for the Iwo Jima landing and did not return to its parent organization until after L-Day.

On the night of 26–27 March, while the 77th consolidated its conquests and prepared for the next day’s battles, Major Jones’ men landed on and reconnoitered the reef islets comprising

Map 5: Seizure of Kerama Retto, March 1945

Keise Shima.48 When reconnaissance of the small group revealed no trace of the enemy, the Marines reboarded their APDs with information of reef, beach, and terrain conditions. Their findings were then forwarded to the 77th Division intelligence officer for evaluation and distribution to the units which were to land on Keise Shima.

During the night of 27–28 March, scouts from Company A landed on Aware Saki, a small island off the southern tip of Tokashiki Shima. Again there was no evidence of the enemy. The only encounter with the Japanese occurred on 29 March, during early morning landings on Mae and Kuro Shima, two small islands which lie between the Kerama Retto and Keise Shima. At 0630, a suicide boat, apparently manned by only one soldier, was observed heading at high speed for Mae Shima’s beach from Tokashiki Shima. The one-man regatta was brought to a speedy and spectacular end as the explosive-laden craft disintegrated under a hail of machine gun fire. A reconnaissance of Kure Shima shortly thereafter indicated no troops or civilians, nor any installations.

In order to remove some of the obstacles to the landing of XXIV Corps Artillery units on Keise Shima on 31 March, UDTs blasted a path through the off-shore coral reefs early that morning, and this completed the work they had begun on the 27th. Then, after 2/306 landed unopposed and determined that no enemy had slipped back to Keise after the Marine reconnaissance, men and equipment of the 420th Field Artillery Group went ashore and immediately set up to fire. By 1935, the group’s 155-mm guns (“Long Toms”) began registering on preselected targets in southern Okinawa. There, the Japanese later reported, they “incessantly obstructed our movements by laying an abundant quantity of fire inside our positions, the fire being directed mainly to cut off our communications.”49 Also landing on Keise were part of a team from an Army air warning squadron and an AAA (automatic weapons) platoon which, when ashore and set up, became part of the area antiaircraft defense system.

Already beset by American carrier-based strikes and by ships’ gunfire which blasted Okinawa in a precise and businesslike manner, the Japanese felt that the artillery fire from Keise was overdoing it a bit. A special attack unit was formed to raid the island artillery emplacements, and the 5th Artillery Command’s 15-cm guns were ordered to conduct counterbattery fire in an attempt to destroy the American Long Toms. Neither measure attained success, and the Thirty-second Army was never able to enforce its order to “stop

the use of enemy artillery on Keise Shima.”50

Before L-Day, the floating naval base in the Kerama Retto was functioning at a high pitch. From watery take-off lanes, seaplanes rose to harass enemy submarines and shipping in the China Sea. Kamikaze-damaged vessels were salvaged and repaired on an around-the-clock schedule, while the rearming, refueling, and revictualling of healthy ships kept pace. Without this frontline logistical facility, “many more ships and personnel of the service force than were available in the Okinawa area would have been required at sea to make replenishment an accomplished fact for all fleet forces.”51

In contrast to the conspicuous prelanding operations of ICEBERG forces in the target area, the Thirty-second Army was able to surround its tactical dispositions with a greater degree of secrecy. Not until after the landing on Okinawa and relentless probing by the assault forces did the Tenth Army learn what the strength of the enemy was and where his positions were. Before L-Day, American knowledge of enemy dispositions was sketchy, and as late as L minus 1 (31 March), the G-3 of the 6th Marine Division was told that “the Hagushi beaches were held in great strength.”52

The factor which tipped the scales in favor of an unopposed Allied landing on the Hagushi beaches was General Ushijima’s decision to defend the southeast coast of Okinawa in strength. When the 2nd Marine Division made its feint landings on D-Day and D plus 1, the Japanese commander’s staff believed its earlier estimate that “powerful elements might attempt a landing [on the Minatoga beaches]” was fully justified.53 Consequently, a substantial portion of the artillery and infantry strength of the Thirty-second Army was immobilized in face of a threat in the southeast that never materialized.

Although Ushijima’s command had prepared for an American landing elsewhere, from the Japanese point of view the Hagushi beaches remained the most obvious target. Even while propaganda reports—mostly untrue—of successful Kamikaze attacks against the invasion fleet bolstered Japanese morale, the commander of a scratch force formed from airfield personnel on the island warned his men not “to draw the hasty conclusion that we had been able to destroy the enemy’s plan of landing on Okinawa Jima.”54 The commander of

the 1st Specially Established Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Tokio Aoyangai, proved himself clairvoyant, for in less than 24 hours after his message had been distributed, the Northern and Southern Attack Forces were moving into their transport areas ready to launch the assault.