Chapter 4: the First Days Ashore

Seizure of the Beachhead1

Optimum weather conditions for an amphibious landing prevailed at the target on L-Day when the Central Pacific Task Forces launched the attack against Okinawa on 1 April 1945, Easter Sunday. The coming of dawn revealed cloudy to clear skies and a calm sea with but a negligible surf at the shore. Moderate easterly to northeasterly winds were blowing offshore, just enough to carry the smoke away from the beaches. To the many veteran jungle fighters among the invading troops, the 75-degree temperature seemed comfortably cool.

At the target, the major naval lift and support elements moved into their assigned areas off the Hagushi beaches. Once in position, the ships prepared to debark troops. Off the Minatoga beaches on the other side of the island, the same preparations were conducted concurrently by the shipping that carried the 2nd Marine Division.

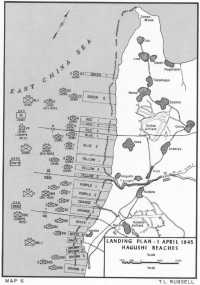

Admiral Turner unleashed his forces at 0406 with the traditional order, “Land the Landing Force,”2 and Okinawa’s ordeal began with a percussive overture of naval gunfire. (See Map 6.) The enemy reacted to the landing shortly after dawn as he mounted scattered air attacks on the convoys. In the continuing belief that the main effort was directed at the Minatoga area, the few Japanese aircraft not destroyed by American carrier air or ships’ antiaircraft guns disregarded the more lucrative targets off Hagushi and concentrated on Demonstration Group shipping. Kamikazes struck the transport Hinsdale and LST 884 as troops, mostly from the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines3 and its reinforcing elements, were disembarking for the feint run into the beaches. Reported killed were 8 Marines; 37 were wounded, and 8 were

Main batteries of USS Tennessee hurl tons of high explosives at Okinawa as assault amtracs head for the beachhead. (USN 80-G-319325)

Aerial view of the Hagushi anchorage and Yontan airfield on L plus 2, looking southeast from Zampa Misaki. (USN 80-G-339242)

listed as missing in action.4 It is somewhat ironic that units not even scheduled to land on Okinawa on L-Day sustained the first troop casualties.

Air support arrived over the target in force at 06505 and the assault forces began to debark ten minutes later. The transport areas became the scenes of purposeful activity as troops climbed down landing nets into waiting landing craft, while armored amphibians, and amphibian tractors preloaded with troops and equipment, spewed forth from the open jaws of LSTs. At the same time, tank-carrying LCMs (landing craft, mechanized) floated from the flooded well decks of LSDs (landing ships, dock). Other tanks, rigged with T-6 flotation equipment, debarked from LSTs to form up into waves and make their own way onto the beaches.6

In reply to the murderous pounding of the Hagushi beaches by 10 battleships, 9 cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 177 gunboats, the Japanese returned only desultory and light artillery and mortar fire. Even though the assault waves formed up in assembly areas within range of this fire, neither troops nor invasion craft were hit. During the early morning hours, the two battalions of the 420th Field Artillery Group on Keise Shima received heavy enemy counterbattery fire, which stopped American unloading operations on the reef for four hours but caused no damage.

Lying off each Okinawa invasion beach were control vessels marking the lines of departure (LD). Landing vehicles quickly formed into waves behind the LD and at 0800, when the signal pennants fluttering from the masts of the control vessels were hauled down, the first wave, composed of LVT(A)s (landing vehicle, tracked (armored)), moved forward to the beaches in an orderly manner behind a line of support craft. Following on schedule, hundreds of troop-carrying LVTs, disposed in five to seven waves, crossed the lines of departure at regular intervals and moved determinedly towards the shore.

Despite the ferocity of the prelanding bombardment, enemy artillery and mortars continued scattered but ineffectual fire on the invasion waves as they made the 4,000-yard run to the beach. On approaching the shoreline, the LVT(A)s fired upon suspected targets, while naval gunfire lifted from the beach area to hit inland targets. Carrier fighters that had been orbiting lazily over the two flanks of the beachhead began diving over the landing area and neutralized it with repeated strafing, bombing, and napalming runs.

As the assault waves hit the beaches, smoke was laid down on the hills east of Yontan to prevent enemy observation of the landing zone. On the other side of the island, Demonstration Group

landing craft raced toward the Minatoga beaches only to reverse their course and retire to the transport area behind a smoke screen as the fourth wave crossed the line of departure.

Neither the reef fringing the beaches nor enemy mortar fire on the beaches themselves interfered with the successful XXIV Corps landing south of the Bishi Gawa, The eight Army assault battalions were landed by six successive waves of LVTs and moved forward without opposition.

The sea wall, which had caused some concern to XXIV Corps planners, had been breached by naval gunfire. In anticipation of the early build-up ashore, engineers, landing in the first waves, blasted additional beach exits in those portions of the wall which remained standing. Upon landing, the LVT(A)s poured through these breaches, hard on the heels of the infantry, and moved to protect the flanks, while amphibious trucks (DUKWs), preloaded with 4.2-inch mortars, and tanks rolled inland.

Off the Marine landing zone, north of the Bishi Gawa, the reef was raggedly fissured and became smoother only as it neared the beach. A rising tide floated the landing vehicles over a large portion of the reef and the boulders which fringed it. On the northern flank of the 1st Marine Division, however, the large circular section of the reef off the Blue Beaches presented difficulties to the tractors attempting to cross at that point, and delayed their arrival at the beach.

During the approach of IIIAC assault waves to assigned beaches, several instances occurred when inexperienced wave guide officers failed to follow correct compass courses or when they did not guide by clearly recognizable terrain features on the shore. Some troops were thus landed out of position. For example, Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth’s 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines—assigned to RED Beach 1—was landed on the right half of GREEN 2 in the zone of the 22nd Marines (Colonel Merlin F. Schneider), and on the rocky coast line between GREEN 2 and RED 1. (See Map 6.)

Elements of Colonel Edward W. Snedeker’s 7th Marines were landed in relatively insignificant numbers on the beach of the 4th Marines (Colonel Alan Shapley). On the extreme right flank of the 1st Marine Division, however, the fourth wave of RCT-5 was diverted across the corps boundary and landed on the right flank of the 7th Infantry Division. The Marine wave consisted principally of Lieutenant Colonel Charles W. Shelburne’s 1/5 reserve—Company B—and part of the battalion command post group. By 0930, a sufficient number of LVTs had been sent to pick up all but one lieutenant and two squads, who did not rejoin their parent unit until L plus 3.7 The fifth and sixth waves of the 5th Marines landed on

Map 6: Landing Plan—1 April 1945—Hagushi Beaches

their assigned beaches after the guide officers of these waves corrected the faulty course heading followed by the fourth wave.

Despite these unexpected deviations from the landing plan, all the LVT(A)s spearheading the IIIAC attack reached the beach by 0830 and all eight assault battalions were ashore by 0900. The beaches had not been mined and opposition to the landing consisted only of sporadic mortar and small arms fire. This resulted in but few casualties and caused no damage to the LVTs. “With utter consternation and bewilderment and with a great deal of relief the assault wave landed against practically no opposition.”8

As the assault troops surged up the terraced slopes behind the beaches and sped inland, the center of invasion activity shifted from the line of departure to the transfer line at the edge of the reef. There, small boat, LVT, and DUKW control was established to unload support troops and artillery units on call. Supporting units continued to pour ashore during the morning as the attack progressed against only slight resistance. At the transfer line, reserve infantry elements shifted from ships’ boats into the LVTs which had landed assault troops earlier. Flotation-equipped tanks made the beaches under their own power, others were landed at high tide from LCMs, and the remainder were discharged directly onto the reef from LSMs and LSTs. DUKWs brought the 75-mm and 105-mm howitzers of the light field artillery battalions directly ashore.

All tanks in the 1st Division assault wave, landing from LCMs and LCTs, were on the beach by noon. One exception was a tank that foundered in a reef pothole. The captain of LST 628, carrying the six T-6 flotation-equipped tanks of the 1st Tank Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. Stuart), disregarded the operation plan and refused to allow them to launch until H plus 60 minutes.9 At that time, he set them in the water 10 miles off the landing beaches. These tanks finally reached shore after being afloat for more than five hours, but two of them were hung up on the reef because of the ebbing tide. Because the LSMs carrying Lieutenant Colonel Stuart’s reserve tanks had great difficulty in grounding on the reef on L-Day, the first tracked vehicle off the ramp of one was lost in an unseen pothole. Of the four LSMs employed, two finally landed their cargo late on L-Day, another at noon on L plus 1, and the last on 3 April.

Tanks were landed early in the 6th Division zone, where each of the three companies of the 6th Tank Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Denig, Jr.) employed a different landing procedure. Tanks equipped with flotation gear swam to the reef, easily negotiated the rugged coral, continued on to the beaches, where they jettisoned their pontoons and became operational by H plus 29 minutes. The company in LCMs

came in at high tide (0930) and landed without incident. The third company successfully landed directly from the LSMs grounded on the reef but forded the deep water between the grounding point and the shore with difficulty.10

Soon after landing, the accelerated pace of the 6th Division assault to the north overextended Colonel Schneider’s 22nd Marines. Troops were taken from his left battalion, 2/22 (Lieutenant Colonel Horatio W. Woodhouse, Jr.), to guard the exposed flank. This, in turn, weakened the 22nd attack echelon and gave it a larger front than it could adequately cover. Consequently, a considerable gap developed between the 2nd Battalion and the 3rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Malcolm “O” Donohoo), advancing on the right. In less than 20 minutes after the landing, Colonel Schneider ordered his reserve, 1/22 (Major Thomas J. Myers), ashore. Upon landing, the 1st Battalion (less Company C, remaining afloat as regimental reserve) was committed in the center of the regimental zone.

Still meeting no opposition while it continued the rapid move inland, by 1000 the 22nd Marines found its left flank unit stretched dangerously thin. As he pressed the division attack to exploit initial success, General Shepherd anticipated Schneider’s request for reinforcements to cover the exposed flank, and asked corps to release one BLT of the 29th Marines.

During the unopposed 22nd Marines advance on Hanza, the 4th Marines moved on Yontan airfield against light to moderate resistance. Isolated enemy pockets, built around light machine guns, slowed the regiment only slightly as it penetrated several hundred yards inland and made contact on its right with the 7th Marines at the division boundary. By midmorning, the 4th reached the airfield and found it unguarded.

Only intermittent sniper fire coming from beyond the field opposed the 4th Marines as it swept across the air facility and secured its objective by 1300. The airfield was found to be essentially intact, but all buildings had been stripped and the antiaircraft emplacements contained only dummy guns.

As this rush carried Colonel Shapley’s regiment beyond adjacent units, a wide gap developed between its left flank and the right of the 22nd Marines, then in the vicinity of Hanza. Shapley’s regiment jumped off again at 1330 against only light resistance on its left. Tanks were called in to reduce several cave positions in this area. After these positions were neutralized, the attack continued slowly through rugged, wooded terrain. In order to maintain contact with the 7th Marines and to rectify the overextended condition of the 4th, 2/4 was released from division reserve at 1500 and immediately committed on the regiment’s left to establish contact with the 22nd Marines.

Because the division left flank was still dangerously exposed, General Shepherd regained 1/29 (Lieutenant Colonel Jean W. Moreau) from corps. Released by IIIAC at 1300, the battalion landed at 1500 and, with its left flank anchored on GREEN Beach 1, completed tying in with 22nd Marines at 1700.

The 1st Marine Division, to the south of the 6th, met with the same surprising

lack of resistance. By 0945 on the division left, Colonel Snedeker’s 7th Marines had advanced through the village of Sobe, a first priority objective, and the 5th Marines (Colonel John H. Griebel) was 1,000 yards inland standing up. With the beaches clear, and in order to avoid losing any troops as a result of anticipated enemy air attacks against the congested transport area, the division reserve was then ordered ashore. Colonel Kenneth B. Chappell’s 1st Marines embarked two BLTs, and the third was to land as soon as transportation became available.

Reserve battalions of both assault regiments were picked up by LVTs at the transfer line and shuttled to the beach before noon. The 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Edward H. Hurst), landed in the center of the regimental zone of action and then moved to the rear of Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger’s 2/7, the left flank unit. At 1400, 3/5 was positioned 400 yards behind 1/5 on the division right boundary. When the 5th Marines reserve was moved up behind the assault battalions, the commanding officer of 3/5, Major John A. Gustafson, went forward to reconnoiter. An hour later, at 1500, his group was fired on by a small bypassed enemy pocket and Gustafson was wounded and evacuated. His executive officer, Major Martin C, Roth, took over temporarily until 4 April, when Lieutenant Colonel John C. Miller, Jr., assumed command.11

Thus disposed in depth with its reserve elements echeloned to guard the flanks, the 1st Division continued its steady advance over the rolling checkerboard terrain. In addition to having developed the numerous caves that honeycombed the many hillsides in the zone, the Japanese had begun to organize other positions throughout the area and the Marines encountered innumerable field fortifications in varying stages of development. These defenses, however, were only held by small, scattered groups of service troops and home guards. According to a postwar Japanese source, these troops comprised “...a hastily organized motley unit ... facing extreme hardship in trying to achieve an orderly formation.”12

The principal bridge over the Bishi Gawa below Hiza was undamaged and standing,13 and local defense forces had made little or no effort to destroy the narrow bridges that spanned lesser streams. What proved a greater hindrance to the advance than the desultory enemy attempts at halting it was what one observer described as “an excellent network of very poor roads.”14

By 1530, the majority of IIIAC supporting troops and artillery was ashore. One howitzer of Colonel Robert B. Luckey’s 15th Marines and three of the 11th Marines (Colonel Wilburt S. Brown) were lost when the DUKWs carrying them foundered on the reef, but the remaining divisional artillery of IIIAC was landed successfully. Even

though the artillery arrived early, a combination of the rapid infantry advance and the resulting strain on communications made it difficult for forward observers to register their battalions. Corps artillery reconnaissance parties began landing at 1300, and found that “selection of position areas from map and photo study proved suitable in every case.”15

The advance was halted between 1600 and 1700, and the attacking infantry dug in, established contact all along the IIIAC line, and carried out extensive patrolling to the front. To maintain the impetus of the attack of his division on L-Day, General Shepherd had committed his entire reserve early. The 6th Marine Division remained in good shape and was well disposed to resume the advance on the 2nd. Both the 4th and 22nd Marines still maintained a company in reserve, while the corps reserve (29th Marines, less 1/29) was located northwest of Yontan airfield, in the vicinity of Hanza, after its landing at 1535.

General del Valle’s division was unable to close the gap on the corps boundary before dark and halted some 600 yards to the rear of the 7th Infantry Division on the right.16 A company was taken from the reserve battalion of the 5th Marines and put into a blocking position to close the open flank. Two 1st Marines battalions, 1/1 and 2/1 (commanded by Lieutenant Colonels James C. Murray, Jr., and James C, Magee, Jr., respectively), landed at 1757. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen V. Sabol’s 3rd Battalion was on the transfer line at 1800 but, unable to obtain LVTs, remained in the boats all night. The 1st Battalion was attached to the 5th Marines for administrative control and moved inland to Furugen, while 2/1, similarly attached to the 7th Marines, dug in east of Sobe by 1845.17

Artillery support for the Marine infantry was readily available by nightfall. The 15th Marines had established its fire direction center (FDC) by 1700, and its batteries were registered by 1830. All of Colonel Brown’s artillery battalions were prepared to fire night defensive missions, though two of the 11th Marines battalions did not complete their registration because of the late arrival of spotter planes. Since enemy action was confined to unsuccessful attempts at infiltration of the lines and to intermittent mortar and machine gun fire in the 4th Marines sector, there were relatively few requirements for artillery support that first night on Okinawa.

ICEBERG’s L-Day had been successful beyond all expectations. In conjunction with the extended initial advance of IIIAC, XXIV Corps had captured Kadena airfield by 1000, driven inland to an average depth of 3,500 yards, and advanced south along the east coast to the vicinity of Chatan. On 1 April, the

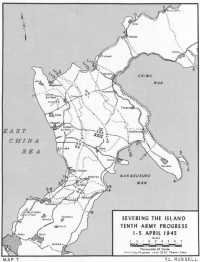

Tenth Army had landed an estimated 50,000 troops in less than eight hours and established a beachhead that was 15,000 yards wide and varied from 4,000–5,000 yards in depth. (See Map 7.) For the entire day’s operations by four assault divisions, casualties were reported to Admiral Turner as 28 killed, 104 wounded, and 27 missing.

Progress Inland

Following a relatively quiet night, which was punctuated only by sporadic sniper, machine gun, and mortar fire, Tenth Army units resumed the attack on L plus 1 at 0730. Perfect weather again prevailed, as the early morning was cool and a bright sun soon dispelled the ground fog and haze to provide unlimited visibility. While no artillery preparation preceded the jump off on the second day, all guns were available on call for support fires, and registration of all battalions, including those of the 11th Marines, had been completed. Carrier planes were on station at 0600 before the attack began.

With the resumption of the advance, the 6th Marine Division continued to the east, while its left flank unit, 1/29, began clearing operations to Zampa Misaki. Admiral Turner wanted the point captured as a site for a radar station. He also wanted the BLACK Beaches uncovered so that unloading operations could begin. Throughout the day, the 22nd Marines and 1/29 advanced rapidly against light resistance. By 1025, the latter unit had seized Zampa Misaki and found that the beaches there were unsuitable for use by IIIAC.

Major Anthony Walker’s 6th Reconnaissance Company was then ordered to reconnoiter the beaches on the north coast of Zampa and the villages of Nagahama and Maeta Saki. Walker’s scouts accomplished this mission before noon without opposition, and while doing so, encountered 50 civilians, who were taken into custody and transferred to stockades. The Nagahama beach was reported satisfactory for landing supplies.

On the 6th Division right, the 4th Marines advanced through rugged terrain, meeting intermittent enemy reaction. As the day wore on, however, pockets of stiff resistance were increasingly encountered, and at 1100, 3/4 came up against strong enemy positions, consisting of mutually supporting caves on both sides of a steep ravine. When the leading platoon entered the draw, it was met by a hail of small arms fire so heavy that the Marines could not bring out their 12 wounded until four hours later. “Every means of painlessly destroying the strongpoint was unsuccessfully tried and it was finally taken by a typical ‘Banzai’ charge with one platoon entering the mouth of the draw and one platoon coming down one side of the two noses that formed the pocket.”18

The speed of the second day’s advance again caused the assault units to become overextended. About midmorning, Colonel Shapley reported that there was a gap between his regiment and the 7th Marines, which he believed to be some 1,000 yards south of the division

Map 7: Severing the Island—Tenth Army Progress, 1–5 April 1945

boundary19 and an adjustment was requested by Shepherd. The 7th was ordered to cover the gap, a movement that placed it ahead of 1/4. In sideslipping back to its own zone, 1/4 met with stiff opposition from strongly entrenched enemy forces similar to those that had held up 3/4. With the aid of a platoon of tanks, this position was finally reduced. The two battalions killed some 250 Japanese in the course of the day’s operations before the 4th Marines attack ceased at 1830, some 1,000 yards ahead of the L plus 3 line.

During the day, Major Paul F. Sackett’s 6th Engineer Battalion repaired the strips on Yontan and placed one taxiway in good enough condition to permit a VMO-6 spotter plane to land at 1500. By 4 April, all three Yontan runways were ready for emergency landings.

Spearheaded by extensive advance patrolling, the 1st Marine Division moved out on L plus 1 unopposed except for the slight interference presented by local defense units, which were part of a force officially designated the 1st Specially Established Regiment. Activated by the Thirty-second Army on L minus 4, it was composed of 3,473 airfield service troops and Boeitai, less than half of whom were armed with rifles, In addition, the equipment of this regiment consisted of 55 light machine guns, and 18 grenade launchers. The heaviest weapons of this unit were 10 heavy machine guns and 5 20-mm dual-purpose machine cannon, For the most part, the troops were completely untrained, and even the regular Army service troops had not been given such basic infantry training as firing a machine gun.

When Ushijima pulled his combat troops south, the 1st Specially Established Regiment had been assigned the mission of servicing final air traffic on the Yontan and Kadena fields. The regiment was to destroy those fields on order after the Americans had landed and then to retire to positions from which it could deny their use to the invaders. The 1st Battalion was located in the 6th Division zone; the 2nd and part of the 3rd Battalion in the 1st Marine Division area; the remainder of the 3rd Battalion faced the 7th Infantry Division; and the 5th Company of the 12th Independent Infantry Battalion was assembled in regimental reserve at Hanza. Uniquely enough, upon interrogation of some troops captured from these organizations,

it was found that not one knew that he was in this paper organization, and only one had ever heard of it. Without exception, the prisoners gave as their unit the service or home guard element with which they had served at the airfields.

Despite their motley makeup, their commanding officer., Lieutenant Colonel Tokio Aoyanagi, determined to employ them in slowing the advance of the invaders. At 1400 on L-Day, he issued an order directing all of his battalions to hold every strongpoint, to carry out night raids, to destroy all bridges, and to construct tank obstacles. The colonel pleaded for “each and every one [to] carry out his duty with the conviction of certain victory.”20

His men were poorly armed and mostly leaderless. Moreover, they lacked communications. When the escape routes to the organized forces in the south were cut off, therefore, this haphazardly organized group collapsed. The greater portion of these troops apparently fled to the northern hills, while a few, undoubtedly, escaped to the south; 26 were captured and 663 killed by the 1st Marine Division alone. Most of those who remained in the combat area quickly divorced themselves from the military, but other operated as snipers or guerrillas dressed in civilian attire.

Reliable intelligence was meager and hard to come by owing to the lack of contact with the enemy regular forces. As tactical operations developed rapidly against light opposition, hundreds of dazed civilians filtered through the lines and into the paths of the assault forces, When the Marines met these Okinawans, they interrogated, screened, and sent natives back to division stockades. Attempts to obtain information of the enemy from the older inhabitants were stymied because of the difficulties imposed in translating the Okinawan dialect. Younger natives of high school age, who had been forced to learn Japanese by the Nipponese overlords, proved to be a lucrative source of information, however.

Even though most civilians were cooperative with the Americans, they could provide very little information of immediate tactical importance. Nonetheless, the Okinawans confirmed the picture of the Japanese withdrawal to the south, clarified the presence or absence of units suspected of being in the area, aided in establishing an order of battle, and revealed the general and specific areas to which the rest of the civilian population had fled.

Military government personnel soon discovered that local inhabitants had moved with all their belongings to caves dug near their homes to escape from the path of war. Although interpreters roving the area in trucks mounted with loudspeakers assured the natives that they would be saved and induced them to leave their refuges voluntarily, other Okinawans continued to believe Japanese propaganda and viewed the American “devils” as barbarians and cutthroats. In many cases, particularly in isolated regions, it was necessary for language and civil affairs personnel “to enter the caves and verbally pry the

dwellers loose.”21 Sometimes this resulted in troops coming upon a tragic scene of self-destruction, where a father, fearing for the lives of his family and himself at the hands of the invaders, had killed his wife and children and then had committed suicide. Fortunately, there were no instances of mass suicide as there had been on Saipan or in the Keramas.22

Specifically organized patrols were dispatched to round up civilians and transfer them to stockades in areas predesignated in military government plans. These patrols were often accompanied by language officers searching for documents, but most of the material found was of no military value. When a rewarding find was made pertinent information was orally translated to the regimental S-2, who took down matters of local significance. The paper was then sent to the division G-2 language section.

The 1st Division learned from documents captured in its zone that the Japanese authorities had actively conscripted Okinawan males between the ages of 17 and 45 since the bombings of 10 October 1944. After their induction, these men were placed into three types of organizations; regular Thirty-Second Army units, specially organized engineer units, and labor forces. In order to neutralize the effects that might result from the presence of such a large hostile group in its midst, the Tenth Army decreed that all able-bodied males between the ages of 15 and 45 years were to be detained for further screening together with bona fide prisoners of war.23

Special agents from Army Counterintelligence Corps detachments assigned the division assisted the Marines in interrogating and screening each male Okinawan detainee. Eventually, after their clearance by the American agents, cooperative and intelligent natives were enlisted to aid in the interrogations. Specially qualified Okinawans were moved to liberated villages and districts to serve as informants for the Island Command.

Even more of a problem than the inability of the Marines to come to grips with the enemy or their difficulty in obtaining usable intelligence was the dislocation of the logistical plan and the subsequent strain on supporting units that resulted from the unopposed and rapid troop advance. The logistics annex of the operation plan had been based on the premise that the landings would be stubbornly contested, and unloading priorities were assigned accordingly. When the uncontested landing permitted the immediate debarkation of troops who had not been scheduled ashore until 2 or 3 April, landing craft originally allocated to move cargo were diverted for this troop movement. As a result, the unloading of supplies was delayed on L-Day.

Because the road net ranged in degree from primitive to nonexistent and in

order to prevent traffic congestion, LVTs were not sent too far inland. The front lines were supplied, therefore, by individual jeeps, jeep trailers, weasels, and carrying parties, or a combination of all four. As forward assault elements moved farther inland, the motor transport requirement became critical and a realignment of unloading priorities was necessary. As a consequence, the unloading of trucks from AKAs and APAs was given the highest priority.

By the night of L plus 1, all of the units supported by the 11th Marines had moved beyond artillery range, and Colonel Brown’s regiment had to displace forward, The movement of 1/11 (Lieutenant Colonel Richard W. Wallace), in particular, was long overdue. Artillery displacements were not yet possible, however, since organic regimental transportation had not landed and no other prime movers were available. Two battalions were moved forward on L plus 2 by shuttle movements and an increased transportation capability, which resulted when more trucks came ashore and were made available. The other two battalions moved up on the 4th. Although it had been planned to have the bulk of Corps Artillery on the island by the end of L plus 1, and all by the end of L plus 2, it was not until 10 April that General Nimmer’s force was completely unloaded. “This melee resulted from the drastic change in unloading priorities.”24 Fortunately, unloading operations were improved by L plus 2.

Engineer battalions organic to the Marine divisions were generally relieved of mine removal tasks by the unfinished state of Japanese defenses, but there was no letup in their workload. Owing to the accelerated movement forward, the “narrow and impassable stretches of roads [and] lack of roads leading into areas in which operations against the enemy were being conducted, the engineers were called upon more than any other supporting unit.”25 A priority mission assigned to the engineers was the rehabilitation of the airfields after they had been captured. Their early seizure permitted work to begin almost immediately, and after the engineers had reconditioned Yontan airfield beyond merely emergency requirements, the first four-engine transports arrived from Guam on 8 April to begin evacuating the wounded.26

The only real problem facing General del Valle’s units during the second day ashore, and one that tended to check a more rapid advance, was “the difficulty of supply created by the speed with which our units were moving and by lack of good roads into the increasing rough terrain.”27 In viewing the lack of any formidable resistance to either one of his assault divisions, General Geiger gave both of them permission to advance beyond the L plus 5 line without further orders from him.

Bewildered civilians wait to be taken to military government camps in the wake of the swift American advance across the island. (USMC 117288)

Two marines of the 6th Division safeguard a young Okinawan until he can be reunited with his family. (USMC 118933)

By 1500 of L plus 1, the progress of the 5th Marines had caused its zone of action to become wider, and in order to secure the division right flank and maintain contact with the 7th Infantry Division, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 1st Marines were echeloned one behind the other on the corps boundary. Upon landing that morning, 3/1 moved inland to a point east of Sobe and remained there in division reserve.

As the 1st Marine Division had not yet located the center of the enemy defenses or determined his strength, “the weakness of the resistance ... [remained] a source of astonishment” to General del Valle.28 During the day, attempts at infiltration and the occasional ambushing of patrols by small hostile groups had little effect on the tactical situation. When the troops dug in at 1600, the division position was stabilized for the night on a line generally conforming to the L plus 5 line in the 7th Marines zone, while the 5th was slightly short of it.

To search out enemy positions, the 1st Reconnaissance Company (1st Lieutenant Robert J. Powell) was ordered to scout the division zone on 3 April, taking a route that followed along the corps boundary to the base of the Katchin Peninsula on the east coast. On this same day, the assault regiments were to continue the attack with an advance to the L plus 10 line. Because there had been only slight activity on the 1st Division front during L plus 1, the 11th Marines fired only five missions. While night defensive fires were planned for the second night ashore, they were not called for.

On this day in the XXIV Corps zone, the Army divisions also were able to exploit unexpectedly light resistance. The 7th Infantry Division had reached the east coast at Tobaru overlooking Katsuren Wan (Bay), effectively cutting the island in half and severing the enemy line of communications. Units of the 96th Division had advanced to the east and south, and succeeded in penetrating irregularly defended positions, some of which consisted merely of road mines and booby-trapped obstacles. At the end of L plus 1, General Bradley’s front lines extended from the vicinity of Futema on the west coast to approximately one mile west of Unjo in the east.

By the close of 2 April, all assault division command posts had been established ashore, and the beachhead and the bulk of the high ground behind the landing beaches firmly secured. Enemy observation of Tenth Army movement and dispositions was thus limited, and any land-based threat to unloading operations removed.

Commenting on the conduct of Marine operations for the two days, General Buckner signaled General Geiger:–

I congratulate you and your command on a splendidly executed landing and substantial gains in enemy territory. I have full confidence that your fighting Marines will meet every requirement of this campaign with characteristic courage, spirit, and efficiency.29

During the night of 2–3 April, enemy activity was confined to sporadic sniper,

machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire, and intermittent infiltration attempts by individuals and small groups. Undeterred by this harassment, General Geiger’s corps jumped off at 0730 on the 3rd and again found slight opposition to the attack.

The 6th Marine Division resumed the offense in the same lineup with which it had ended the previous day. (See Map 7.) Both the 4th and 22nd Marines advanced an average of more than 7,000 yards through difficult and heavily broken terrain to seize the dominating Yontan hill mass and the division objective beyond. While the 22nd Marines moved forward, 1/29 patrols covered the entire Zampa Misaki without discovering any enemy troops on the peninsula. There was no repetition of the fierce clashes experienced by the 4th Marines the preceding two days. Throughout the day, the division was supported by tanks, which operated along the hazardous narrow trails existing on the precipitous ridge tops to the front.

By midmorning, the axis of advance of the 6th Division began to swing to the north as the towns of Kurawa and Terabaru were gained. Scattered rearguard action from withdrawing enemy troops was the only resistance encountered by the 22nd Marines advancing on Nakadomori. In order to develop the situation on the division front and to determine the nature of Japanese defenses in the Ishikawa Isthmus, General Shepherd ordered his reconnaissance company to scout the coastal road from Kurawa to Nakadomori, and, at that point, to cross the isthmus to Ishikawa. Supported and transported by a reinforced platoon from the 6th Tank Battalion, the tank-infantry reconnaissance force completed the assignment and returned to its lines before nightfall. In the course of the patrol, the Marines made no enemy contacts and were fired upon only once from the vicinity of Ishikawa.

While 1/4, the right battalion, had relatively easy going most of the day, 3/4 on the left lagged behind because of the increasingly difficult terrain. When the division attack ceased at 1700, General Shepherd’s troops were tied in with the 1st Division nearly a mile northeast of Kubo.

Following its sweep of Zampa Misaki, Lieutenant Colonel Moreau’s 1/29 occupied new reserve positions east of Yontan airfield from which it could support either division assault regiment. At 2000, when IIIAC warned of an imminent enemy airborne attack, Moreau was reinforced with a tank company, which was deployed to defend the airfield by 2300; no Japanese paratroops or airborne infantry landed that night.

The only notable enemy activity experienced by the 1st Division during the hours of darkness, 2–3 April, occurred in the 7th Marines sector where the Japanese attempted extensive infiltration. In the fire fight that ensued, 7 Marines were killed and 7 wounded, while approximately 20–25 of the would-be infiltrators perished.

This brief flurry was not an indication of an imminent major engagement for when del Valle’s three combat teams pushed forward on 3 April they met only light opposition on the left and virtually none on the right. “Our ever-widening zone of action prohibited the

‘hand-in-hand’ advance of some small island operations and our units were able to maintain contact and clear their areas only by patrolling to the flanks and front.”30 With the resumption of the advance, motorized units of the 1st Reconnaissance Company began a series of patrols which were to encompass almost all of the division zone of action. In the morning, the Ikebaru–Napunja area was reconnoitered, after which the company was ordered to proceed down the Katchin Peninsula. Completing this mission by 1300, Lieutenant Powell’s scouts were ordered up the east coast to Hizaonna and to return to division lines before dark. During the entire trip the only sign of enemy activity was a lightly held tank trap.

All units of the division were ordered to halt at 1700 on ground most favorable for defense. On the left, the 7th Marines had pushed forward against moderate opposition over increasingly difficult terrain. As the regimental commander later stated:–

The movement from the west coast landing beaches of Okinawa across the island to the east coast was most difficult because of the rugged terrain crossed. It was physically exhausting for personnel who had been on transports for a long time. It also presented initially an almost impossible supply problem in the Seventh’s zone of action because of the lack of roads.31

Despite these hardships, Snedeker’s troops gained 2,700 yards of enemy territory and dug in for the night after overrunning a strongpoint from which heavy mortar, 20-mm, and small arms fire had been received. Shortly thereafter, Colonel Snedeker received permission to exploit what appeared to be an apparent enemy weakness and to continue the attack after the rest of the division had ended it for the day. He then ordered his reserve battalion to pass between 1/7 and 2/7 and advance towards the village of Hizaonna on the high ground overlooking the east coast.32

The major fighting in this advance occurred when the 81-mm mortar platoon was unable to keep up with the rest of 3/7. Company K, following the mortars, became separated from the main body upon reaching a road fork near Inubi after night had fallen. When he became aware of the situation, Lieutenant Colonel Hurst radioed the company to remain where it was and to dig in after its repeated attempts to rejoin the battalion were defeated by darkness and unfamiliar terrain. An estimated platoon-sized enemy group then engaged the Marines in a heavy fire fight, which continued through the night as

the Japanese effectively employed mortars, machine guns, and grenades against the isolated unit. By noon on 4 April, a rescue team from 3/7 was able to bring the situation under control and the company was withdrawn after having sustained 3 killed and 24 wounded.33

With its right flank anchored on Nakagusuku Wan, 1/1 held a line sealing off two-thirds of the Katchin Peninsula. The 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, meeting negligible resistance from armed civilians,, occupied the high ground immediately west of Gushikawa, where the eastern shore could be covered by fire. During the day’s gains, “supply had been almost nonexistent and the troops were without water and still depending on the food they landed with.”34

The advance of the 5th Marines gained momentum throughout the day, the troops having met only a four-man enemy patrol. The 1st Battalion reached Agina, where 3/5 was committed on the right to contact 2/1. One thousand yards away, on the left of the regiment 2/5 occupied the village of Tengan and then advanced to the east coast of Okinawa.35

By the end of L plus 2, the 1st Marine Division had driven to the coast, advancing 3,000–5,000 yards, and thus placed its lines 8–13 days ahead of the ICEBERG schedule. The 6th Division meanwhile, had moved through difficult and heavily broken terrain honeycombed with numerous caves to gain 3,500–7,000 yards of enemy ground in its zone.

At dark on 3 April, the 6th Division left flank was anchored at the base of the Ishikawa Isthmus, thereby placing the Tenth Army 12 days ahead of schedule in this area. During this same day, the XXIV Corps had reached the eastern coast in force and its units had begun reorganizing and regrouping for the attack to the south. The 7th Infantry Division had secured the Awashi Peninsula, and pivoting southward in a coordinated move with the 96th Division, secured an additional 3,000 yards before the end of the day. In the vicinity of Kuba-saki, the 32nd Infantry came up against its first real opposition on Okinawa, when it made contact with an enemy force estimated at 385 men. The regiment overran the enemy position and finally took Kuba-saki. After completing the wheel to the right, the 96th Division reorganized its front lines, putting its units in position for the southerly drive.

While observation planes, OYs (Consolidated-Vultee Sentinels), operated from Yontan airfield during the day, the 6th Engineer Battalion and the 58th Seabees continued working on the field. An F6F (Grumman Hellcat) from the carrier Hancock made an emergency landing at 1110, and the pilot reported that, in his opinion, the runway could

satisfactorily accommodate all types of carrier planes. The other runways were expected to be operational for fighter-type aircraft by noon on the 4th.

Because of the very favorable situation that had developed during the day, General Buckner removed all restrictions he had placed on movement past the L plus 10 line and ordered IIIAC to seize the L plus 25 line at the earliest possible time. Geiger then ordered the 6th Marine Division to continue the attack on 4 April and to take the L plus 15 line, prepared to continue the advance to the L plus 20 line. General del Valle’s division was ordered to advance to the L plus 20 line. (See Map 7.)

The continuing cool and clear weather on 4 April again served as a welcome change from the torrid humidity of the Philippines and the Solomons. Following a quiet night, broken only by the fighting in the Inubi area, the IIIAC jumped off on schedule at 0730 on L plus 3.

As the 6th Division pushed forward, no enemy hindered the 4th and 22nd Marines advance to the L plus 15 line. General Geiger’s reserve, the 29th Marines (Colonel Victor F. Bleasdale), less its 1st Battalion, had reverted to division control earlier, and Shepherd assigned it as his reserve. When it became apparent that the day’s objectives would be reached by noon, the assault regiments were ordered to continue beyond the L plus 15 line to additionally assigned division objectives.

With all three battalions in the assault, the 22nd Marines reached their Phase 1 objective at 1250. Organized as a fast tank-infantry column, Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse’s 2122 sped up the west coastal road. All the while, he sent patrols inland along the route to maintain contact with 1/22 patrol columns in the interior of the regimental attack zone. On the right, the 3rd Battalion reached Ishikawa before noon, having gradually pinched out the 4th Marines when that regiment reached the coast at about the same time. Colonel Shapley was then ordered to reconsolidate his unit in the Ishikawa area, and to prepare to support either division flank unit in the attack northward. In the course of the morning operations, exceedingly rough terrain, and the logistical support problems it posed, created greater obstacles to the advance than did the enemy.

At 1300, the attack up the Ishikawa isthmus was resumed, with RCT-22 and 1/29 attached36 taking over the entire division front from the west to the east coast. Advance was rapid in the afternoon as patrols met only scattered resistance until 1730, when a Japanese strongpoint, built around several heavy machine guns, fired upon a 3/22 patrol north of Yaka. Night defenses were not taken up until after this obstacle was reduced by units of Donohoo’s 3/22 and Moreau’s 1/29, the latter having assumed the 1/22 sector when Major Myers’ unit was placed in regimental reserve.

When the 6th halted for the day, its Marines had advanced over 7,500 yards and held a line that stretched across the isthmus from a point just south of Yakada on the west coast to Yaka on

the east. In this day’s fighting, the increasingly rugged terrain forecast the difficulties to be faced during the march northward. Supply lines were strained almost to their limit as they were extended across numerous ravines and steep valleys in the mountainous interior. Despite this, the troops were fed and logistical replenishment continued as the division prepared to continue the advance the next day.

With the exception of the few enemy positions encountered in its push to the east coast, the 1st Marine Division still did not have a clear picture of what Japanese defenses lay ahead on 4 April. As on the day before, the attack jumped off without artillery preparation. Rapid progress with little resistance was the general order, except on the left where the 7th Marines was still busy with the enemy in the vicinity of Inubi. The 2nd Battalion reached the east coast by 1130 and, shortly thereafter, made firm contact with the 4th Marines. On the extreme right of the regiment, light but stubborn enemy fire enfiladed the 1/7 right flank, and delayed its arrival at the coast until 1700. Because of the rapid advance of the regiment over a roadless terrain, Colonel Snedeker requested supply airdrops during the day. The first drop was made at Hizaonna at 1400, about the same time that General del Valle’s new CP was opening at a point between Ikebaru and Napunja.

After dark, when the 7th Marines was consolidating its positions on the L plus 15 line, the enemy began numerous attempts at infiltrating American lines. Although 45 Japanese were killed as they probed the regimental positions, it was difficult to obtain any information regarding the units represented by these men, who employed rifles, grenades, bayonets, and sharply pointed bamboo spears, which the Marines promptly dubbed “idiot sticks.”37

In the center of the division line the 5th Marines reached the shores of Kimmu Wan by early afternoon, when the battalions consolidated their positions and established firm contact with all flanking units. The same day, the 1st Marines occupied Katchin Peninsula in orderly fashion by noon and set up its defenses. Once these two regiments were in position on the L plus 15 line, they initiated patrolling to the rear to eliminate bypassed positions, a task in which the reconnaissance company and the division reserve (3/1) also participated.

That evening, 3/1 was ordered to take over the defense of Yontan airfield from the 29th Marines on 5 April. Tentative plans were formulated to release the 7th Marines to IIIAC in order to assist the 6th Division in its drive north. The next day, the 7th Marines (less Hurst’s 3/7, which was attached to the 5th Marines) went into IIIAC reserve with orders to occupy and defend the village of Ishikawa, pending further tactical developments.38

In the course of its four-day drive across Okinawa, the 1st Marine Division found only negligible resistance, and this from Japanese units of undetermined strength employing delaying or rearguard tactics. The question remained: Where was the enemy? The division had killed 79 Japanese, captured

2 prisoners of war (POWs), and encountered 500–600 civilians, who were quickly interned.

To the south of the 1st Division, the tactical situation in the XXIV Corps zone had been undergoing radical change. (See Map 7.) Army assault divisions had aggressively exploited the initial lack of enemy resistance. During the same time, they were hampered less by supply difficulties than the Marine divisions had been. Once General Hedge’s divisions had wheeled to the right on 3 April for the drive southward, the lines were reorganized and preparations made for fresh assault units to effect passage of the lines the next day. The corps was now ready for the Phase I southern drive.

The 7th Division pushed forward on 4 April only to meet stiffening resistance from hostile artillery-supported infantry at Hill 165.39 After a day’s fighting, the division drove the Japanese from this dominant piece of terrain and continued forward to net approximately 1,000 yards for the day. Meanwhile, in the 96th Division zone, Army infantry battalions were held up by reinforced enemy company strongpoints several times during the day. Heavy Japanese machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire impeded the advance, but by the night of 4 April, the XXIV Corps had seized the L plus 10 line, which had been originally designated the southernmost limit of the Tenth Army beachhead.

An increasing volume of enemy defensive fires was placed on the Army divisions as they moved out for their fifth day of ground action. On the XXIV Corps left flank, resistance came mainly from small, scattered enemy groups in the hills and ridges bordering the east coast. In the 96th Division zone to the right, both assault regiments became heavily engaged with Japanese outpost strongpoints during L plus 4. About noon, an enemy counterattack was broken up by tank-artillery supported infantry action just when the right flank regiment of the 96th, the 383rd Infantry, drove unsuccessfully against the first of a series of prepared ridge positions guarding the approaches to Kakazu. Four tanks were lost during the day’s fighting, one to a mine and the others to enemy antitank fire. Compared to the long advances of the previous four days of ground action, the 96th Division was able to take only 400 yards on L plus 4.

the Swing North40

Although the Japanese forces in the south offered an increasingly stiff defense as their positions were uncovered, the exact whereabouts of the main enemy strength in the northern part of the island remained as clouded as was his order of battle. Even though Phase I of the ICEBERG plan did not specify any action beyond isolation of the area

above the Ishikawa Isthmus for the IIIAC, General Buckner believed that it would be profitable to exploit initial Marine successes. As a result, on 5 April he ordered IIIAC to reconnoiter Yabuchi Shima, to conduct a vigorous reconnaissance northwards to the Motobu Peninsula, and to initiate preparations for the early completion of Phase II. (See Map II)

At the same time that the 6th Division conducted its reconnaissance up the isthmus, the 1st Division entered a period devoted primarily to defensive activity. Supplies were brought up from the rear, positions were improved and camouflaged, and all units began heavy patrolling to the rear. At noon on L plus 4, a 1st Marines patrol waded across the reef to Yabuchi Shima from the Katchin Peninsula, captured five Boeitai, and reported the presence of some 350 civilians.

The nearly perfect weather which had prevailed since L-Day, deteriorated with light rain over scattered areas in the early evening of the 5th. Although there was no evidence that it was organized, enemy activity behind the lines increased during the day but only from small separated groups apparently operating independently of each other. Of this period, a regimental commander noted:–

There [were] almost daily patrol contacts with well-armed enemy groups. ... Some of these groups were wandering aimlessly about while others occupied well defended, organized, and concealed positions. These patrol operations were extremely valuable in giving to the officers and men of the regiment added confidence in each other and helped all to reach a peak of physical perfection ... independent patrols ... often under fire, added greatly to the ability of the leaders of small units.41

Because it was necessary to move supplies forward to support the advance, the 6th Division delayed H-Hour on the 5th until 0900. At that time, armor-supported infantry columns were dispatched on deep reconnaissances up both sides of the isthmus, the 6th Reconnaissance Company on the left (west) flank and Company F, 4th Marines on the right. The latter advanced 14 miles before turning back in the late afternoon. During the day, the patrol had been delayed three times by undefended roadblocks but met no opposition until the tanks entered Chimu., where two of the enemy encountered were killed and a Japanese fuel truck was destroyed. The drive up the other side of the island was unopposed, but the tanks could not bypass a destroyed bridge at Onna. The reconnaissance company, forced to continue on to Nakama by foot, returned to the lines that evening.

While 6th Division mobile covering forces searched out routes of advance, the assault battalions rapidly moved forward, detaching companies as necessary to reduce bypassed enemy pockets of resistance inland. Although the terrain had become more difficult to negotiate and the enemy increasingly active, the division gained another 7,000 yards. The 22nd Marines held the general line Atsutabaru–Chimu, with the 4th Marines (less 1/4 bivouacked at Ishikawa)42 2 located in assembly areas just behind the front line, prepared to pass through early the next day. At 1000 on

Heavy undergrowth on the Ishikawa Isthmus hinders the progress of a 4th Marines patrol advancing to the north of Okinawa. (USMC 116527)

Grinning troops of the 29th Marines in M-7s heading for Chuta in their drive towards Motobu Peninsula. (USMC 117507)

the 5th, the 29th Marines were released to parent control by IIIAC and moved to an assembly area in the vicinity of Onna.

As the 6th Division began its dash up the isthmus on 6 April, the 7th Marines in corps reserve patrolled the division zone south of the Nakadomari–Ishikawa line43 while the 6th Reconnaissance Company mopped up enemy remnants from this boundary north to the Yakada–Yaka line. After its lines had been passed by the 29th Marines on the left and the 4th Marines on the right, the 22nd reverted to division reserve and began patrolling back to the area of responsibility of the reconnaissance company.

Because there were only a few roads inland, Colonel Shapley planned to move rapidly up the main road along the shore, detaching patrols from the advance guard to reconnoiter to their source all roads and trails into the mountainous and generally uninhabited interior. In order to maintain control during the anticipated rapid advance, the regimental march CP moved out in a jeep convoy at the head of the main body. By 1300, 2/4 had been used up by the detachment of small patrols, and the 3rd Battalion then passed through in accordance with the prearranged plan of leapfrogging the battalions. When the regiment halted for the day at 1600, it had advanced seven miles, encountering only scattered enemy stragglers. The supply operations of the 4th Marines on L plus 5 were hampered more than usual by the fact that three bridges along the route had been bombed out earlier by friendly air.

The 4th Marines resumed operations the next morning deployed in the same manner in which it had halted the night before—3/4, 1/4, and 2/4 in that order. The advance on L plus 6 was virtually a repeat of the previous day as the regiment continued the push up the east coast, the lead battalion dissipating its strength with the dispatch of patrols into the interior. As a result, the 1st Battalion (Major Bernard W. Green) passed the 3rd at noon and led the way to the regimental objective, opposed only by the difficult terrain, poor roads, and fumbling enemy defense measures.

Nearly all such efforts failed, however, for in very few instances was the 6th Division drive slowed. Enemy defensive engineering efforts were almost amateurish, for abatis, with neither mines nor booby traps attached or wired in place, were pushed aside easily by tank-dozers or bulldozers. Even basic defensive combat engineering principles were violated by the Japanese, who did not distribute their mines in roads and defiles in depth. They even failed to cover with either infantry fire or wire what they had placed. On the whole, the mines were little more than a nuisance and caused but few casualties.44 Bridges were often incompletely destroyed by Japanese demolitions, and Marine engineers were able to save valuable time by utilizing the remaining structural members as foundations for new spans in hasty bridge construction.

When the 6th Division drive towards the north began, each assault regiment was assigned one company of the 6th Engineer Battalion in direct support. A platoon from each of these companies was attached to advance guards to clear roadblocks, remove mines, and build bypasses for combat vehicles around demolished bridges. The remainder of each company followed up the advance, repairing and replacing bridges and widening narrow thoroughfares wherever possible to accommodate two-way traffic. Following closely in the wake of the assault regiments, the third company of the engineer battalion further improved roads and bridges.

At the end of the Ishikawa Isthmus, where the mountains came down to the sea, engineer services were in even greater demand as they were required to widen roads that were little more than trails.45 The infantry advance was slowed by the terrain as well as by the near-physical exhaustion of the patrolling Marines, who had been going up and down the thickly covered broken ground. Despite this tortuous journey, the 4th Marines had made another seven miles by the late afternoon of 7 April. Then, just north of Ora, the 1st Battalion set up a perimeter defense with its flanks secured on the coast. Colonel Shapley’s CP and weapons company were located in the village itself, while 3/4 and 2/4 were deployed in defensive perimeters at 1,000-yard intervals down the road.

On the west coast, the 29th Marines had seized its next objective on 7 April, again with little difficulty. Advance armored reconnaissance elements reached Nago at noon to find the town leveled by naval gunfire, air, and artillery. Before dark, the regiment had cleared the ruins and organized positions on its outskirts.

As the advance northwards continued, the difficult road situation had made it imperative to locate forward unloading beaches from which the 6th Division could be supplied. (See Map II) When Nago was uncovered, it was found suitable for this purpose, and IIIAC requested the dispatch to this point of Marine maintenance shipping from the Hagushi anchorage. On 9 April, cargo was discharged for the first time at Nago, relieving the traffic congestion on the supply route up the coast from Hagushi.46

When planning for ICEBERG, General Shepherd had determined that Major Walker’s company would be employed only in the reconnaissance mission for which it was best fitted and trained. In effect, the unit was intended to serve as the commanding general’s mobile information agency. Pursuant to this decision, the reconnaissance company, supported and transported by tanks, was dispatched up the west coast road ahead of the 29th Marines in an effort to ascertain the character of Japanese strength on Motobu. After the company scouted Nago, it swung up the coastal road to Awa, and then, after retracing its steps to Nago, crossed the base of the peninsula in a northeasterly

direction to Nakaoshi.47 Before returning to Nago for the night, the patrol uncovered much more enemy activity than had been previously revealed in the division zone of action and had met several enemy groups that were either destroyed or scattered.

From the very beginning of the drive to the base of the Motobu Peninsula, the 15th Marines was employed so that each assault regiment had. one artillery battalion in direct support and one in general support. The rapidity of the 6th Division advance during this phase of the campaign forced the artillery regiment to displace frequently, averaging one move a day for each battalion and the regimental headquarters. To keep up with the fast moving infantry, the artillerymen were forced to strip their combat equipment to a bare minimum; they substituted radio for wire communications and by leapfrogging units, managed to keep at least one artillery battalion in direct support of each assault infantry regiment throughout the advance up the isthmus.48

Augmenting the 15th Marines, 6th Division artillery support was reinforced by the 2nd Provisional Field Artillery Group (Lieutenant Colonel Custis Burton, Jr.) which displaced to positions north of Nakadomari on the eve of the drive up the Ishikawa Isthmus. Four days later, when resistance on Motobu Peninsula began to stiffen., the 15th Marines was reinforced further by the attachment of the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion as artillery. The following day, the corps artillery supporting the advance was moved to Besena Misaki, a promontory at the southern extremity of Nago Wan, where it remained throughout the period of Marine operations in the north.49

Motobu Uncovered

Owing to the lack of intelligence about the location of the enemy, and a Tenth Army order to avoid unwarranted destruction of civilian installations unless there was a clear indication or confirmation of enemy presence, naval gunfire support was not used extensively in the drive up the Ishikawa Isthmus. After 5 April, however, all IIIAC naval fire support was diverted to the 6th Division zone of action. As the Marines moved north, these ships kept pace, firing up the numerous ravines leading down to the beach. Each assault battalion was furnished a call-fire ship during the day, and each regiment was furnished a ship to fire illumination at night.50

The Tenth Army gained land-based air support when TAF squadrons from MAG-31 and -33 arrived ashore on 7

Japanese 155-mm gun captured in the heart of Mount Yae Take had previously commanded the entire coastal road along southern Motobu Peninsula. (USMC 122207)

Suicide boats found at Unten Ko on 10 April by Marines of 2/29. Note warning that boats had been booby trapped. (USMC 127905)

and 9 April.51 The 6th Division did not need them immediately during the first two weeks in the north, however, for the division advance had been rapid and suitable targets scarce. Daylight combat air patrols were flown almost as soon as the squadrons landed, but strikes in support of ground operations did not begin until L plus 12, and then they were directed at Japanese targets in the XXIV Corps zone in the south. As enemy resistance stiffened on Motobu Peninsula, Marine air was called upon to destroy emplacements, observation posts, and troop concentrations.52

After the division had gained the base of the Motobu Peninsula and had begun extending reconnaissance operations to the west on 8 April, aerial observation and photo studies confirmed the fact that the enemy had chosen to make his final stand in the rugged mountains of the peninsula. In order to reduce this Japanese bastion, and at the same time maintain flank security and continue the drive to the northernmost tip of Okinawa, General Shepherd needed to reorient the axis of operations and redeploy his forces. Consequently, the 22nd Marines was taken out of division reserve and set up on a line across the island from Nakaoshi to Ora to cover the right and rear of the 29th Marines attacking to the west. Assembled near Ora, also, was the 4th Marines, which was positioned to support either the 29th Marines on Motobu or the 22nd in the north.

During the next five days, the 4th and 22nd Marines combed the interior and patrolled in the north, while the 29th probed westward to uncover the enemy defense.53 On L plus 7, 2/29 moved northeast from Nago to occupy the small village of Gagusuku. The 1st Battalion, initially in reserve, was ordered to send one company to secure the village of Yamadadobaru, a mission accomplished by Company C at 0900. An hour later, the battalion as a whole was ordered to the aid of Company H, 3/29,54 which had encountered heavy resistance in the vicinity of Narashido. By 1500, 1/29 had converged on this point and, despite heavy enemy machine gun and rifle fire, had reduced two strongpoints, after

which Lieutenant Colonel Moreau’s men dug in for the night.

Intending to locate the main enemy force on Motobu, the 29th Marines moved out on 9 April in three columns; the 3rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Erma A. Wright) on the left flank, the 2nd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel William G. Robb) on the right flank, and Moreau’s 1st Battalion up the mountainous center of the peninsula. All three columns encountered opposition almost immediately. This was an indication that the division may have at last hit the major enemy resistance in the north, and it was located in the area from Itomi west to Toguchi.

In the 3/29 zone on the left, roads were found to be virtually impassable as a result of effective enemy use of roadblocks, mines, and demolitions. The 6th Engineer Battalion reported that from Nago westward on the Motobu Peninsula the enemy had been even more destructive. They had demolished every bridge and blasted numerous tank traps in the roads. The Japanese had been careful to place these obstacles at points where no tank bypass could be constructed. Traps that had been made in the narrow coastal roads were put at the foot of cliffs where back fill was unavailable. Those in the valleys were always located where the road passed through rice paddies, When the crater was in a cliff road, trucks had to travel long distances to obtain fill for the hole.55

In the center, 1/29 was to occupy and defend Itomi before nightfall; about 600 yards short of the objective, however, the battalion was met by a strong enemy force and compelled to dig in for the night in place. The north coast was patrolled as far as Nakasoni by Robb’s 2nd Battalion, which destroyed supply dumps and vehicles and dispersed small enemy groups. The battalion also scouted Yagachi Shima with negative results.

The next day, L plus 9, Robb’s men seized Unten and its harbor, where the Japanese had established a midget submarine and torpedo boat base. The base had been abandoned and large amounts of equipment and supplies were left behind by approximately 150 Japanese naval personnel, who were reported to have fled inland to the mountains. Toguchi, on the other side of the peninsula, was captured by 3/29, which sent patrols inland to Manna. On 10 April, 1/29 pushed forward through Itomi, and on the high ground north of the town it uncovered numerous well-prepared positions from which the enemy had fled.

During the first two days of the drive to clear Motobu Peninsula, frequent enemy contacts were made in the difficult terrain northwest and southwest of Itomi. Night counterattacks increased in intensity; one particularly strong attack, supported by artillery, mortars, machine guns, and 20-mm dual-purpose cannon, struck the 1/29 defense perimeter on the night of 10–11 April and was not broken up until dawn.

Patrols from 2,/29 were sent out on 11 April to make contact with 1/29 near Itomi. They met little opposition but substantiated previous intelligence estimates locating the main Japanese battle position in an area between Itomi and Toguchi. As a result of this verification, 2/29 (less Company F) was recalled from the north coast and ordered to set

up defensive installations and tie them in with 1/29 on the high ground near Itomi. Company F continued patrolling. During the day, 1/29 patrols scouted just to the north and northeast of Itomi and met only light resistance. On the other hand, 3/29, moving inland to contact the 1st Battalion, ran into heavily defended enemy positions at Manna and was forced to withdraw under fire to Toguchi.

In compliance with Admiral Turner’s expressed desire that Bise Saki was to be captured early for use as a radar site, the 6th Reconnaissance Company was ordered to explore the cape area on 12 April, and to seize and hold the point unless opposed by overwhelming force. As anticipated, resistance was light, and the area was captured and held. That evening, Company F, 29th Marines, reinforced the division scouts. Overall command of this provisional force was then assumed by the reconnaissance company commander.56

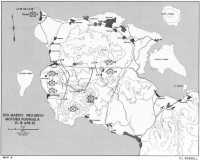

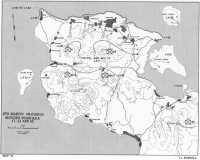

In order to fix more definitely the hostile battle position, the 29th Marines continued probing operations. On the 12th, the 1st and 2nd Battalions were disposed in positions near Itomi, and 3/29 was located in the vicinity of Toguchi. (See Map 8.) Company G was sent north to contact the reinforced division reconnaissance company and to meet 2/29 at Imadomari. Company H was ordered east to meet 1/29 at Manna, and Company I was ordered to patrol to the high ground south and east of Toguchi and to remain there overnight. As these last two companies proceeded on their missions, they came under intense fire that prevented the completion of their assignments unless they were to risk sustaining unacceptable casualties. Under cover of prompt call fires from the destroyer Preston, LVT(A) fire, and an 81-mm mortar barrage, Company I was withdrawn while Company H served as rear guard. Both companies had organized a perimeter defense at Toguchi by midafternoon when the battalion CP received considerable artillery and mortar fire. The day’s action cost the battalion 9 killed and 34 wounded.57

Because of this significant enemy reaction in the Toguchi area, Company G, upon its arrival at Imadomari at 1415, was recalled by the battalion. When Company H had been hit in the morning, 3/22 was alerted for possible commitment, and in the afternoon it was ordered to assemble in division reserve at Awa. Battalion headquarters and Companies I and K completed the motorized move after 1700, and L arrived at 0900 the following morning.

By the night of 12 April, General Shepherd’s division was confronted with a fourfold task: to continue occupation and defense of the Bise area; to secure the line Kawada Wan–Shana Wan and prevent enemy movement through that area; to seize, occupy, and defend Hedo Misaki, the northernmost tip of Okinawa; and to destroy the Japanese forces on Motobu Peninsula.58 On 10 April, 1/22 had established a perimeter defense at Shana Wan from which it

conducted vigorous patrolling eastward to the coast and north towards Hedo Misaki. By the 12th, battalion patrols had contacted the 4th Marines on the east coast; 3/4 was ordered to move to Kawada the next day.

During the period 8–12 April, the 4th Marines, located near Ora, patrolled all areas within a 3,000-yard radius of the regimental bivouac. On the 10th, Company K was sent north along the east coast on extended patrol after which it was to rejoin its battalion at Kawada. While in the field, the company relied on LVTS for daily support and evacuation. In a week’s time, the patrol had travelled 28 miles up the coast.

Assigned the capture and defense of Hedo Misaki, Woodhouse’s 2/22 moved rapidly up the west coast on 13 April in a tank- and truck-mounted infantry column, “beating down scattered and ineffective resistance.”59 At 2110, the 2/22 commander reported that a patrol had entered Hedo by way of the coastal road and that the entry had been opposed only by 10 Boeitai.60 As soon as the rest of the battalion arrived, a base was set up and patrols were sent out to make contact with the 4th Marines advancing up the east coast.

At the end of the second week on Okinawa, on Friday, 13 April (12 April in the States), ICEBERG forces learned of the death that day of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Memorial services were held on board American vessels and behind Tenth Army lines; those who could attend these services did so if the fighting permitted. One senior officer of the 1st Marine Division said later:–

It was amazing and very striking how the men reacted. We held services, but services did not seem enough. The men were peculiarly sober and quiet all that day and the next. Plainly each of them was carrying an intimate sorrow of the deepest kind, for they paid it their highest tribute, the tribute of being unwilling to talk about it, of leaving how they felt unsaid.61

the Battle For Yae Take

While three of its four assigned missions in the north were being accomplished by extensive patrolling against little or no opposition, the 6th Marine Division found that destroying the firmly entrenched bulk of the enemy was becoming an increasingly difficult problem. Company I had apparently touched a sensitive nerve during its probings near Toguchi, judging by the immediate enemy reaction. This assumption was confirmed on the night of 12–13 April, when the 29th Marines encountered some English-speaking Okinawans, who had at one time lived in Hawaii.

The Marines were told that there was a concentration of 1,000 Japanese on the high ground overlooking the Manna–Toguchi road south of the Manna River. The civilians said further that the enemy force was commanded by a Colonel Udo, and that it contained an artillery unit under a Captain Kiruyama.62 Previous

reports of enemy order of battle were corroborated by the operations of strong combat patrols; the 6th Division now firmly fixed the Japanese defenses in an area some six by eight miles surrounding the rugged and dominating Mount Yae Take.63 (See Map 8.)

The ground around this towering 1,200-foot-high peak prohibited extensive maneuvering and completely favored the defense. Yae Take was the peninsula’s key terrain feature and its heights commanded the nearby landscape, the outlying islands, and all of Nago Wan. The steep and broken approaches to the mountain would deny an attacker any armor support. Infantry was sure to find the going difficult over the nearly impassable terrain, The Japanese defenses had been intelligently selected and thoroughly organized over an obviously long period. All natural or likely avenues of approach were heavily mined and covered by fire.

It was soon concluded that approximately 1,500 men were defending the area and that the garrison, named the Udo Force after its commander, was built around elements of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade. Included in this group were infantry, machine gun units, light and medium artillery, Okinawan conscripts, and naval personnel from Unten Ko. In addition to 75-mm and 150-mm artillery pieces, there were two 6-inch naval guns capable of bearing on the coastal road for 10 miles south of Motobu, on Ie Shima, and all of Nago Wan.64

General Shepherd’s estimate of the situation indicated that reduction of the Yae Take redoubt was beyond the capabilities of a single reinforced infantry regiment. In face of this conclusion, the 4th Marines (less 3/4) was ordered to move from the east coast to Yofuke. The 29th Marines was ordered to continue developing the enemy positions by vigorous patrolling on 13 April and to deploy for an early morning attack on the next day.65

Complying with General Shepherd’s orders, Colonel Bleasdale again attempted to clear the Itomi–Toguchi road66 and join his 1st and 3rd Battalions. As elements of 1/29 moved out of Itomi towards Manna, they were ambushed and hit hard again by the 20-mm cannon fire coming from the commanding heights. Probing north from Awa, 3/22 patrols also came under fire. Before these patrols could withdraw under the cover of their battalion 81-mm mortars, an hour-long fire fight ensued. Adding to the general harassment from the enemy, artillery fire was placed on 3/22 positions in the afternoon.

At this same time, Japanese counterbattery fire was delivered against the

Map 8: 6th MarDiv Progress—Motobu Peninsula, 14 April 1945

emplaced artillery of 2/15 (Major Nat M. Pace). This heavy bombardment inflicted 32 casualties, including two battery commanders and the executive officer of a third battery, and destroyed the battalion ammunition dump and two 105-mm howitzers.67 Air strikes were called in on the suspected sources of the fire and 3/22 dispatched patrols in an attempt to locate the enemy mortar batteries. Fires and exploding ammunition made the Marine artillery position untenable, so Pace’s men withdrew to alternate positions.68