Part 2: Operations and Negotiations

Blank page

Chapter 6: The Assault

The Airborne Operations

At various airfields in North Africa during the afternoon of 9 July, British and American airborne troops, under a glaring sun, made the final preparations for the operation scheduled to initiate the invasion of Sicily.1 While crews ran checks on the transport aircraft, the soldiers loaded gliders, rolled and placed equipment bundles in para-racks, made last-minute inspections, and received final briefings. Heavily laden with individual equipment and arms, with white bands pinned to their sleeves for identification, the troops clambered into the planes and gliders that would take them to Sicily.

The British airborne operation got under way first as 109 American C-47’s and 35 British Albermarles of the U.S. 51st Troop Carrier Wing at 1842 began rising into the evening skies, towing 144 Waco and Horsa gliders. Two hours later, 222 C-47’s of the U.S. 52nd Troop Carrier Wing filled with American paratroopers of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team and the attached 3rd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry, were airborne.

The British contingent made rendezvous over the Kuriate Islands and headed for Malta, the force already diminished by seven planes and gliders that had failed to clear the North African coast. Though the sun was setting as the planes neared Malta, the signal beacon on the island was plainly visible to all but a few aircraft at the end of the column. The gale that was shaking up the seaborne troops began to affect the air columns. In the face of high winds, formations loosened as pilots fought to keep on course. Some squadrons were blown well to the east of the prescribed route. Others in the rear overran forward squadrons. Despite the troubles, 90 percent of the aircraft

Paratroopers, identified by white arm bands, preparing to emplane for Sicily

Glider Casualty

made landfall at Cape Passero, the check point at the southeastern tip of Sicily, though formations by then were badly mixed. Two pilots who had lost their way over the sea had turned back to North Africa. Two others returned after sighting Sicily because they could not orient themselves to the ground. A fifth plane had accidentally released its glider over the water; a sixth glider had broken loose from its aircraft—both gliders dropped into the sea.

The lead aircraft turned north, then northeast from Cape Passero, seeking the glider release point off the east coast of Sicily south of Syracuse. The designated zigzag course threw more pilots off course, and confusion set in. Some pilots released their gliders prematurely, others headed back to North Africa. Exactly how many gliders were turned loose in the proper area is impossible to say—perhaps about 115 carrying more than 1,200 men. Of these, only 54 gliders landed in Sicily, 12 on or near the correct landing zones. The others dropped into the sea. The result: a small band of less than 100 British airborne troops was making its way toward the objective, the Ponte Grande south of Syracuse, about the time the British Eighth Army was making its amphibious landings.

As for the Americans who had departed North Africa as the sun was setting, the pilots found that the quarter moon gave little light. Dim night formation lights, salt spray from the tossing sea hitting the windshields, high winds estimated at thirty miles an hour, and, more important, insufficient practice in night flying in the unfamiliar V of V’s pattern, broke up the aerial columns. Groups began to loosen, and planes began to straggle. Those in the rear found it particularly difficult to remain on course. Losing direction, missing check points, the pilots approached Sicily from all points of the compass. Several planes had a few tense moments as they passed over the naval convoys then nearing the coast—but the naval gunners held their fire. Because they were lost, two pilots returned to North Africa with their human cargoes. A third crashed into the sea.

Even those few pilots who had followed the planned route could not yet congratulate themselves, for haze, dust, and fires—all caused by the preinvasion air attacks—obscured the final check points, the mouth of the Acate River and the Biviere Pond. What formations remained broke apart. Antiaircraft fire from Gela, Ponte Olivo, and Niscemi added to the difficulties of orientation. The greatest problem was getting the paratroopers to ground, not so much on correct drop zones as to get them out of the doors over ground of any sort. The result: the 3,400 paratroopers who jumped found themselves scattered all over southeastern Sicily—33 sticks landing in the Eighth Army area; 53 in the 1st Division zone around Gela; 127 inland from the 45th Division beaches between Vittoria and Caltagirone. Only the 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry (Maj. Mark Alexander), hit ground relatively intact; and even this unit was twenty-five miles from its designated drop zone.2

Except for eight planes of the second serial which put most of Company I,

The Ponte Dirillo crossing site, seized by paratroopers on D-day

505th Parachute Infantry, on the correct drop zone just south of the road junction objective; except for eighty-five men of Company G of the 505th who landed about three miles away; and except for the headquarters and two platoons of Company A and part of the 1st Battalion command group, which landed near their scheduled drop zones just north of the road junction, the airborne force was dispersed to the four winds.

The planes carrying the headquarters serial, which included Colonel Gavin, the airborne troop commander, were far off course, having missed the check point at Linosa, the check point at Malta, and even the southeastern coast of Sicily. The lead pilot eventually made landfall on the east coast near Syracuse, oriented himself, and turned across the southeast corner of the island to get back on course. Assuming that the turn signaled the correct drop zone, the pilots of the last three planes—carrying the demolition section designated to take care of the Ponte Dirillo over the Acate River southeast of Gela—released their paratroopers. The other pilots, about twelve of them, dropped

their loads in a widely dispersed pattern due south of Vittoria about three miles inland on the 45th Division’s right flank.

Coming to earth in one of these sticks, Gavin found himself in a strange land. He was not even sure he was in Sicily. He heard firing apparently everywhere, but none of it very close. Within a few minutes he gathered together about fifteen men. They captured an Italian soldier who was alone, but they could get no information from him. Gavin then led his small group north toward the sound of fire he believed caused by paratroopers fighting for possession of the road junction objective.

The fire actually marked an attack by about forty paratroopers under 1st Lt. H. H. Swingler, the 505th’s headquarters company commander, who was leading an attack to overcome a pillbox-defended crossroads along the highway leading south from Vittoria. Other sounds of battle came from Alexander’s 2nd Battalion, which was reducing Italian coastal positions near Santa Croce Camerina. Near Vittoria, scattered units of the 3rd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, had coalesced and were also engaged in combat. The eighty-five men from Company G, under Capt. James McGinity, had seized Ponte Dirillo. Elsewhere, bands of paratroopers were roaming through the rear areas of the coastal defense units, cutting enemy communications lines, ambushing small parties, and creating confusion among enemy commanders as to exactly where the main airborne landing had taken place.3

But less than 200 men were on the important high ground of Piano Lupo, near the important road junction, hardly the strength anticipated by those who had planned and prepared and were now executing the invasion of Sicily.

The Seaborne Operations

General Guzzoni, the Sixth Army commander, received word of the airborne landings not long after midnight. Certain that the Allied invasion had begun, he issued a proclamation exhorting soldiers and civilians to repel the invaders. At the same time he ordered the Gela pier destroyed. Phoning the XII Corps in the western part of Sicily and the XVI Corps in the east at 0145, 10 July, he alerted them to expect landings on the southeastern coast and in the Gela–Agrigento area.4

An hour later, the initial waves of the 15 Army Group assault divisions began to come ashore. Near Avola in the Gulf of Noto, on both sides of the Pachino peninsula, near Scoglitti, Gela, and Licata, small British and American landing craft ground ashore and started to disgorge Allied soldiers. Hard on their heels came the larger LCTs and LSTs with supporting artillery and armor. Offshore stood Allied war vessels ready to pound Italian coastal defense positions into submission.

Overhead, Allied fighter aircraft from Malta, Gozo, and the recently captured Pantelleria, covered the landings. Concerned lest the enemy make his maximum air effort against Allied shipping and the assault beaches early on D-day and disorganize the operation at the outset,

Allied air planners had spread their available aircraft over as many of the assault beaches as possible while maintaining a complete fighter wing in reserve. As the ground troops went ashore, fighter aircraft patrolled in one-squadron strength over all the landing areas to ward off hostile air attacks, a commitment that was decreased later in the day.5 In addition, at daylight, formations composed of either twelve A-36 or twelve P-38 fighter-bombers were dispatched every thirty minutes throughout the day to disrupt potential counterattacks by hitting the main routes leading to the assault beaches.6 Because of the heavy commitment of Allied aircraft to these and other missions, no direct or close support was available to the ground troops this day.7

The seaborne landings of the British Eighth Army were uniformly successful. Everywhere the first assault waves achieved tactical surprise and Italian coastal defense units offered only feeble resistance.8 Some fire from coastal batteries and field artillery positions inland did strike the beaches but it was quickly silenced by supporting naval gunfire and the rapid movement of assault troops inland.

In Enna, General Guzzoni received a phone call from the commander of the Naval Base Messina at 0400. The German radio station at Syracuse, the naval commander said, had announced that Allied troops had landed by glider near the eastern coast and that fighting had started at the Syracuse seaplane base. In response, Guzzoni instructed the XVI Corps commander to rush ground troops to the apparently endangered Naval Base Augusta–Syracuse. This, plus the previous information from German reconnaissance aircraft that Allied fleets were close to the southern coast as well, brought home to Guzzoni the fact that the Allies would land simultaneously in many different places. Realizing his forces would be unable to counter all of the landings, he committed his available reserves to those areas he considered most dangerous to the over-all defense of the island: Syracuse, Gela, and Licata. Of these three, Guzzoni considered Syracuse on the east coast the most serious. But he also apparently felt that the presence there of both Group Schmalz and the Napoli Division, plus the supposedly strong defenses of the naval base itself, would be sufficient to stabilize the situation and prevent an Allied breakthrough into the Catania plain. Thus, he ordered

USS Boise bombarding coastal defenses in Gela Landing area

the bulk of the Hermann Göring Division to strike the Allied landings near Gela.9

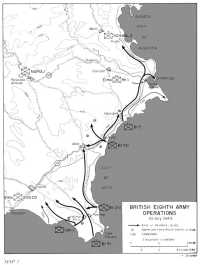

In front of the easternmost British landing the small band of British airborne troops, eight officers and sixty-five men, seized Ponte Grande. By 0800, the 5th Division held Cassibile, on the coastal highway, and by the middle of the afternoon successfully consolidated its beachhead and started north to join with the air-landed troops at the bridge site. Map 1)

But by 1500, the small band of British soldiers at Ponte Grande found themselves in difficult straits. After battling with Italian soldiers, marines, and sailors sent against them from the Naval Base Augusta–Syracuse, only fifteen men remained unwounded. At 1530, these men were overrun. Only eight managed to make their way southward to meet the advancing 5th Division, a column of which, supported by artillery and tanks,

Map 1: British Eighth Army Operations, 10 July 1943

recaptured the bridge intact. As Italian opposition disintegrated, the British column continued unopposed into Syracuse. Scarcely pausing, British troops continued northward along the coastal highway on the way to Augusta. But early in the evening at Priolo, midway between Syracuse and Augusta, Group Schmalz, which had rushed down from Catania to counter the British landings, halted the 13 Corps advance.

According to Axis defense plans Group Schmalz, in conjunction with the Napoli Division, was supposed to counterattack any Allied landing on the east coast. But on 10 July, Col. Wilhelm Schmalz had been unable to contact the Italian unit and had proceeded alone toward Syracuse. Unknown to the German commander, the Napoli Division had tried to counterattack, but some units had been turned back by British forces near Solarino, while other units were lost trying to stem British advances in the Pachino area.10

By the end of D-day the British 30 Corps had secured the whole of the Pachino peninsula as far as Highway 115, which crossed the base between Ispica and Noto. The 1st Canadian Division, the British 51st Highland Infantry Division, and the 231st Independent Infantry Brigade had gone ashore against only feeble resistance and had pushed on in good fashion.

Unloadings over the British beaches progressed slowly but steadily during the day, despite small-scale enemy air attacks that proved annoying but caused relatively little damage. By the end of the day, the Eighth Army had secured a beach-head line extending from north of Syracuse on the east coast, west to Floridia, thence southward roughly paralleling Highway 115.

The Seventh Army had a more difficult time. The gale and high seas had delayed the three naval task forces and after fighting their way to the landing craft release points in the Gulf of Gela, they were somewhat disorganized. Yet only one was seriously behind schedule, that carrying the 45th Division. Those landings were postponed an hour.

Admiral Conolly’s Naval Task Force 86 brought the 3rd Division to the Seventh Army’s westernmost assault area in four attack groups, one group for each of the landing beaches on both sides of Licata.11 Conolly’s flagship, the Biscayne, dropped anchor in the transport area at 0135. The winds had made it difficult for the LSTs, LCIs, and LCTs of his task force to maintain proper speed and formation, so that Conolly, around midnight, when it had seemed virtually impossible to meet H-hour, had ordered his vessels to go all out to make the deadline. Since he had not heard from his units, all of which had been instructed to break radio silence only to report an emergency, Conolly assumed that all his units were in position and ready to disembark the troops of the 3rd Division.

At 0135, 10 July, Admiral Conolly’s assumption that all units were in position

Licata and beach areas to the east toward Gela. Note Licata’s cliffs in left foreground

was not altogether correct. Particularly in the west, the landing ships and craft carrying the 7th RCT had had considerable difficulty making headway in the heaving Mediterranean. All were late in reaching the transport area, but no one had reported that fact to Admiral Conolly.

By using all four of his assigned beaches, General Truscott had adopted two axes of advance for his assault units—actually axes that formed the outer and inner claws of a deep pincer movement against Licata. The left outer claw consisted of the 7th Infantry Regimental Combat Team (Col. Harry B. Sherman) landing over RED Beach. The left inner claw, consisting of a special force (the 3rd Ranger Battalion; the 2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry; a company of 4.2-inch mortars; a battery of 105-mm. howitzers; and a platoon of 75-mm. howitzers) under the command of the 15th Infantry’s executive officer, Lt. Col. Brookner W. Brady, was to land over the two GREEN Beaches. As the right inner claw of the pincer, and the counterpart of the special force, the remainder of the 15th Infantry, led by Col. Charles R. Johnson, was to land over YELLOW Beach. Meanwhile, the right outer claw, the 30th Infantry Regimental Combat Team (Col. Arthur R. Rogers), was to assault across BLUE Beach. Each assault was to move in columns of battalions. Combat Command A, under Brig. Gen. Maurice Rose of the 2nd Armored Division, constituted the 3rd Division’s floating reserve, prepared to land in support of any of the assaulting units or for commitment against Campobello to the north, Agrigento to the west, or Gela to the east.

The division’s assault plan, involving two distinct pincer movements one inside the other, was somewhat complicated. Its execution was aided by the intensive training program undertaken after the end of the North African campaign; by General Truscott’s extensive knowledge of amphibious and combined operations learned in England and in North Africa; and by the extremely close and pleasant working relations which existed between the division and Admiral Conolly’s naval task force. The assault was further facilitated by the weakness of the enemy’s defenses in the Licata area, probably the weakest of all the Seventh Army’s assault areas. Only one Italian coastal division, backed by a few scattered Italian mobile units, stood initially in the 3rd Division’s path. Two Italian mobile divisions—Assietta and Aosta—and two-thirds of the German 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, the only effective fighting forces in the XII Corps sector, were well off to the west near Palermo.

Fully exposed to the westerly wind that was churning up the surf, the LSTs carrying the 7th Infantry had great difficulty hoisting out and launching the LCVPs that would take the assault waves to RED Beach. When one davit gave way and dumped a boatload of men into the water, nine men were lost. Nevertheless, around 0200 the small craft were loaded with troops and in the water, and soon afterwards they were heading for the rendezvous area. The LCVPs had trouble locating the control vessels, which had been serving as escort ships during the voyage across the Mediterranean and which had not been able to take their proper places. Shortly after 0300, already fifteen minutes beyond the time scheduled for touchdown on the beach, the attack group commander ordered the LCVPs in to shore. He was fearful

The right flank beach at Licata, 10 July 1943

that the LCIs, scheduled to land at 0330, would use their superior speed to overtake the LCVPs and he was unable to contact the LCI flotilla commander.

As it was, the first wave, Lt. Col. Roy E. Moore’s 1st Battalion, did not touch down until 0430. The delay was imposed partly by the late start, partly by the longer run to the beach than was originally contemplated because of the faulty disposition of the LSTs in the transport area. The latter error also helped cause the LCVPs to land at the far right end of the beach rather than at the center as planned. The small craft met no fire on the way in, and only light and ineffective artillery fire on the beach after the landings were made.

RED Beach lay in a shallow cove, the seaward approach clear of rocks and shoals. Only 8 to 20 feet deep, 2,800 yards long, the beach at its widest part was backed by cliffs, many reaching a height of 60 feet. Exits were poor: a small stream bed near the center, three paths over the cliff at the left end. Lying in the Italian 207th Coastal Division’s zone (as were all the division’s landing areas), RED Beach was probably the most heavily fortified of all. Artillery pieces dominated the exits and most of the beach; numerous machine gun positions

Highway 115, the coastal road, shown running west to Licata in the distance

near the center and western end provided the defenders with ample firepower to contest an assault landing; an extensive defensive position along some 350 yards of the bluff line contained three coast artillery pieces and another ten machine gun emplacements, all connected by a series of trenches; and the San Nicola Rock at the right end and the Gaffi Tower off the left end gave the defenders excellent observation posts and positions from which to place enfilading fire.

Once ashore, the 1st Battalion promptly set to work. While one company turned to the west and began clearing out beach defenses, a second swept the center of the landing area and set up a covering position on three low hills just inland from the beach. The third company wheeled to the east and occupied San Nicola Rock and Point San Nicola, completing both tasks an hour and a half after landing. (Map IV)

The six LCIs bearing Maj. Everett W. Duvall’s 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry, had assembled just east of the LST anchorage, more than two miles farther offshore than planned. Unaware of this, the flotilla started for shore at 0240, exactly on the schedule planned for the second wave. At this moment the 1st Battalion’s LSTs were completing their launching of the LCVPs. Because the 1st Battalion’s landing craft had veered to the right, the

LCIs carrying the 2nd Battalion saw no signs of small boat activity as they passed the LSTs. Assuming that the assault had not yet started, the flotilla commander turned his craft back to the LST anchorage to find out whether H-hour had been postponed.

After ascertaining that no delay was in order, the flotilla commander again turned his craft shoreward. He sighted a control vessel herding a number of LCVPs toward shore. Recognizing thereby that the assault wave was behind schedule, he halted his own craft, planning to wait twenty-five minutes to give the 1st Battalion time to clear the beach. At 0415, as the sky began to get light, he started the final run to shore. There was no evidence of the 1st Battalion’s LCVPs. The LCIs sailed straight toward the center of RED Beach, the troops of the 2nd Battalion little realizing that they constituted an initial assault wave.

The LCIs were about 450 yards from the beach in a wide, shallow V-formation just opening into a line abreast formation when enemy artillery batteries opened a heavy fire directed chiefly at the left half of the line. The LCIs increased their speed temporarily, then 150 yards from shore slowed down quickly, dropped stern anchors, and beached at 0440 in the face of heavy small arms fire on the beach. The LCIs on the right side of the line escaped the heaviest fire because the Italian gunners could not depress their gun tubes enough to take these craft under fire.

Five of the LCIs beached successfully. One stuck on the false bar off the shore line, tried three times without success to ride over the bar, landed a few troops in rubber boats, and finally transferred the remainder of its troops to an LCI bringing in the third wave. The heavy surf added to the difficulties of the five craft that did manage to ride over the false beach. One lost both ramps soon after they were lowered and was able to land its troops only after salvaging the port ramp.

Almost constant enemy fire harassed the boats. Soldiers in some instances became casualties before they reached the ramps, others were hit while disembarking. The LCI on the left flank drew the heaviest fire, a flanking fire from both left and right. The Italians shot away her controls and communications as she beached, and though able to lower both ramps, the LCI started to broach almost immediately and had to cut the ramps away. She swung completely around until her stern rested on the shore. Disdaining normal disembarkation procedures, the troops scrambled over her stern and dropped to the beach. By 0500, the bulk of the 2nd Battalion was ashore. Two companies swarmed inland and seized Monte Marotta (some four and a half miles inland west of the north-south Highway 123), while the third turned northeast after landing, cut the railroad, and established a roadblock at Station San Oliva where the railroad crossed Highway 123 some three and a half miles northwest of Licata. By 1000, after bypassing most of the enemy resistance along the beach, the 2nd Battalion was on its objectives and successfully drove off a dispirited counterattack launched against Station San Oliva by an Italian coastal battalion, a XII Corps reserve unit.

While the five 2nd Battalion LCIs were trying to retract from the beach, six LCIs carrying Lt. Col. John A. Heintges’ 3rd Battalion came in, along with three LCIs transporting part of the engineer beach group. With some overlapping of the 2nd

Battalion’s LCIs, the 3rd Battalion touched down at 0500 on the left end of RED Beach and received the same heavy fire from the shore defenders which was peppering the leftmost LCI of the 2nd Battalion group. In fact, it was not until the LCIs’ guns went into action to provide covering fires that the 3rd Battalion troops were landed.

The section of beach where the 3rd Battalion landed—near Gaffi Tower—had not been cleared either by the 1st or 2nd Battalion. Nevertheless, despite wire entanglements along the side of the bluff and despite heavy Italian rifle and machine gun fire from positions along the top of the bluff, the battalion pushed aggressively inland and cleared the immediate beach area. One company, after capturing nineteen Italians along the cliff, pushed westward and inland, took the tower, and occupied the high ground just south of the railroad and coastal highway. The other two companies occupied the hill mass north of the highway. An eight-man demolition section pushed on to the west through a defile and blew the railroad crossing over the Palma River, some two miles in front of the battalion’s hill positions.

The LCI bearing Colonel Sherman and his staff came ashore near the center of the beach as dawn was breaking. Tangling with another LCI on its way to assist the broached LCI of the first wave, the boat lost both ramps after only fifteen men had disembarked. The LCI commander tried to discharge the rest of his troops by rigging wooden ladders and rope lines over the side of the boat. But the weight of individual equipment hampered the men, and they floundered in the water, helpless against the fire coming from shore. The craft commander stopped the unloading by this method, deliberately broached the LCI, and sent the RCT command group over the sides. The RCT headquarters opened ashore at 0615, just inland from the beach on top of the cliff.

Naval gunfire might have helped the small craft to the beach, but the two fire support destroyers assigned to RED Beach—the Swanson and the Roe—had collided near Porto Empedocle at 0255 and were concerned with their own troubles. However, help was arriving. At 0520, with enemy fire still falling on the beach, twenty-one LCTs carrying the RCT’s supporting armor and artillery approached through the heavy seas. Fearful for the safety of the LCTs landing under enemy fire, the commander of the RED Beach naval force ordered the craft to halt until the fire could be silenced. But four of the LCTs, either ignoring the order or failing to receive it, kept on going and beached at 0630. The four carried the 10th Field Artillery Battalion. Unloading quickly, utilizing the full-tracked mobility of its M7’s the artillery unit established firing positions 500 to 1,000 yards inland and began firing in support of the infantry units.12

At about the same time, the destroyer

Shore-to-shore LCT at Licata Beach

Army donkeys wading ashore at Licata

Buck, which had been serving as escort for the LCT convoy, was sent in by Admiral Conolly to take over the RED Beach fire support role.13 The cruiser Brooklyn, which had been firing in support of the GREEN Beach landings, also moved over on Conolly’s orders and opened fire on Italian artillery positions which had been firing on RED Beach.14 By 0715, Italian fire had slackened appreciably. Seven minutes later, Conolly ordered the remaining LCTs to beach regardless of cost. Two additional destroyers moved over to assist the Buck in laying a smoke screen on the beaches to cover the LCT landings. Concealed by the smoke and covered by the Brooklyn’s six-inch guns, the LCTs touched down without incident. By 0900 the supporting tanks and the 7th Infantry’s Cannon Company were ashore, followed soon after by the remainder of the engineer beach group and two batteries of antiaircraft artillery.

The 7th RCT’s assigned objectives were secured by 1030 and its establishment of a defensive line on the arc of hills bordering the western side of the Licata plain assured the protection of the beachhead’s left flank. Heavy equipment and supplies were pouring ashore and being moved inland over the soft sand.

A mile to the east of RED Beach and three miles west of Licata, GREEN Beach, flanked by rocks, had the most dangerous approach. Divided into two distinct parts by the Mollarella Rock (82 feet high), which was joined to the island by a low, sandy isthmus, the western part (350 yards wide and almost 20 yards deep) was rockbound except for a short stretch of about 150 yards, the eastern part (400 yards wide, 40 yards deep) lay within a snug cove with a mouth 200 yards across. The eastern beach opened into a stream bed and to a number of tracks providing good vehicular and personnel exits to Highway 115, about a mile and a half inland. The west beach also possessed exits, but its limited size would restrict its use to personnel traffic. Both appeared to be obstructed by barbed wire entanglements. Gun positions on Mollarella Rock dominated the west beach. Immediately back of a stretch of vineyards on the sector of land forming the beach, a defensive position containing at least four machine gun positions and a trench and wire system had been located.

The special force, spearheaded by the 3rd Ranger Battalion, touched down at 0257, just twelve minutes behind schedule. Moving smartly, three Ranger companies cleared the beaches and Mollarella Rock and established a defensive line on the high ground at the left end of GREEN West, while the other three companies cleared the way inland to the western edge of Monte Sole. Lt. Col. William H. Billings’ 2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry, went in over GREEN West at 0342, reorganized, passed through the Rangers at Monte Sole as planned, and thrust toward Licata, the left inner claw of the planned pincer movement. Clearing enemy hill positions as they moved eastward, the men of the 3rd Battalion by 0730 had possession of Castel San Angelo, but a strong naval

Bringing Up Supplies by cart at Licata Beach

Italian Railway Battery on Licata mole destroyed by American naval bombardment on D-day

bombardment of Licata in support of the YELLOW Beach landings prevented the battalion from pushing immediately into the city.

YELLOW and BLUE Beaches east of Licata were much better for assault landings. Beginning not quite two miles east of the mouth of the Salso River and running almost due east for a mile and a half, YELLOW Beach was of soft sand, about 60 yards deep at the western end, narrowing gradually to 15 yards at the eastern end. Licata on the left and the cliffs of Punta delle due Rocche on the right would serve as general guides in the approach. Many good paths and cart tracks ran from the beach across a cultivated strip to Highway 115, here only some 400 yards inland. One-half mile to the east lay BLUE Beach, which consisted generally of firm sand with occasional rocky outcrops. Not quite a mile wide, BLUE Beach deepened from 15 yards on the left to 60 yards on the right. Low sand dunes backed up the right half of the beach; a low, steep bank, the left half. Exits for personnel and vehicles were easy and plentiful, and Highway 115 ran everywhere within 500 yards of the beach.

Naval bombardment was the American answer to the only real Italian interference with the YELLOW Beach landings. The opposition consisted primarily of an Italian railway battery on the Licata mole, an armored train mounting four 76-mm. guns. When the naval fire finally lifted, the train had been destroyed and other Italian resistance silenced. Soldiers from both GREEN and YELLOW Beaches swarmed into Licata, while a battalion which had swung north from YELLOW Beach to the bend in the Salso River moved south into the city shortly after.

At BLUE Beach, farthest to the right, the Italian defenders put up a somewhat bigger show of resistance, though not so strong as that offered at RED Beach. With the 30th RCT forming the right outer claw of the pincer, the naval task force had been delayed in reaching its transport area. The LSTs leading the convoy moved into position and began anchoring at 0115. But the anchorage later proved to be well south of the correct position, thus forcing the LCVPs carrying the assault battalion to make a much longer run to the beaches than planned. Despite this, the first LCVPs grounded just two hours after the LSTs had begun anchoring and only a half-hour behind schedule. The first wave met some rifle and machine gun fire from pillboxes on the beach, and some artillery fire from guns on Poggio Lungo, high ground off to the right. Like its counterpart on the far left, the 7th RCT, the 30th RCT before noon occupied its three primary objectives: three hill masses bordering the eastern side of the Licata plain

Shortly after daybreak Admiral Conolly took the Biscayne close in to shore so that both he and General Truscott could see the beaches. What they saw was encouraging, and reports from two light aircraft that had taken off from an improvised runway on an LST confirmed their impressions.15 The infantry troops were on their objectives or about to take them. The airfield and city of Licata

Enemy Defense Positions along coast road east of Licata

were in hand. Artillery and armor were moving into position to support further advances. One counterattack had been beaten back. The beaches were well organized, men and equipment coming ashore without difficulty. The Seventh Army’s left flank seemed well anchored. In the process, the 3rd Division, its commander ashore by midmorning, had suffered fewer than 100 casualties.

Ten miles southeast of the 3rd Division’s BLUE Beach, and extending twenty miles to the southeast, General Bradley’s II Corps was landing to secure three primary objectives lying at varying distances inland from the assault beaches: the airfields at Ponte Olivo, Biscari, and Comiso. Ponte Olivo, along with the city of Gela, was the responsibility of the left task force, the 1st Division; the others belonged to the 45th Division.

East of the mouth of the Gela River, high sand dunes with scrubby vegetation lay back of the coast. Three miles east of the city and adjacent to and on the inland side of the coastal highway (Highway 115) was the Gela–Farello landing ground, an intermediate division objective. Farther to the east, relatively high ground (400 feet at Piano Lupo, one of the paratroopers’ objectives) flanked the right side of the Gela plain and separated the Gela River drainage basin from that of the Acate River, which empties into the gulf six miles east of Gela. The Acate River, which swings to the northeast at Ponte Dirillo, and its tributary, the Terrana Creek, marked the boundary between the division task forces of the II Corps.16

From Gela, the railroad paralleled the coast to Ponte Dirillo, but the highway, while initially following the coast line, swung inland some five miles east of Gela as it wound around Piano Lupo. From the height of Piano Lupo, a good secondary road branched off northward to Niscemi, following high ground on the eastern edge of the Gela plain. From this point, known to the paratroop task force as Road Junction Y, the coast road took a sharp turn to the southeast to cross the Acate River at Ponte Dirillo.

Another good road, Highway 117, led directly inland from Gela, paralleling the western bank of the Gela River for five and a half miles. A vivid line bisecting the treeless plain, the highway crossed to the east side of the river at Ponte Olivo to a triple road intersection. There, while Highway 117 continued on its northeasterly course, a secondary road swung almost due east to Niscemi, another ran northwest to Mazzarino. In the right angle formed by Highway 117 and the secondary road to Niscemi lay the Ponte Olivo airfield.17

In contrast with the 3rd Division’s assault plan of landing initially only one battalion from each assault force, the 1st Division plan committed two assault battalions from each regimental task force

simultaneously, the third battalion remaining in reserve.

To capture Gela, General Allen, the 1st Division commander, created what he called Force X, a special grouping of Rangers and combat engineers.18 Under Colonel Darby (commander of the 1st Ranger Battalion), the force was to land directly on the beach fronting Gela, one portion on each side of the pier. While the special force worked on the city, the division would make its main effort east of the Gela River, where the division’s two remaining combat teams were to land over four sections of the three-mile-long beach extending southeast from the river. For want of natural boundaries, the four sections were given color designations arbitrarily marking off one section from the other.

The two left sections of the beach—YELLOW and BLUE—were assigned to Col. John W. Bowen’s 26th RCT. While one battalion forced a crossing over the Gela River to aid Force X to subdue Gela, the remainder of the 26th RCT was to bypass the city on the right, cut Highway 117, and occupy high ground two miles to the north. There the RCT would be ready to attack Gela from the landward side if the city still held out, or move farther inland to take other high ground overlooking Ponte Olivo from the west.

Over the other two sections, RED 2 and GREEN 2, the 16th RCT under Col. George A. Taylor was to come ashore. After reducing the beach defenses, the regiment was to cross the railroad, bypass the long, swampy Biviere Pond on the force’s right, cut the coastal highway, and move along the highway to Piano Lupo to join Colonel Gavin’s paratroopers. From there, the 16th RCT was to drive on Niscemi.

Although the Italian XVIII Coastal Brigade (thinly stretched from west of Gela to below Scoglitti) caused no serious concern, the Livorno Division, concentrated to the northwest near Caltanissetta, and the bulk of the Hermann Göring Division, assembled to the northeast near Caltagirone, presented serious problems. Two fairly strong Italian mobile airfield defense groups at Niscemi and at Caltagirone were also in position to strike.

Short one combat team—the 18th RCT was a part of the Seventh Army’s floating reserve; shy supporting armor, for only ten medium tanks were in direct support of the entire 1st Division; with no division reserve (the parachute task force was to form the division reserve after link-up)—the 1st Division faced the strongest grouping of enemy forces in Sicily.

In three long columns, with transports in the center and LSTs and LCIs on the flanks, Admiral Hall’s Naval Task Force 81 brought the 1st Division to the Gela area in the center of the Seventh Army zone. The eleven transports reached their proper stations at 0045, 10 July. Thirty minutes later, eleven of the fourteen LSTs were in position (the other three turned up later in the 45th Division’s zone). The twenty LCIs came up just a few minutes later. Shortly before midnight the wind had dropped, and as the transports and landing ships and craft anchored offshore, the sea leveled off into a broad swell. Behind Gela the entire coastal area, it seemed, was aglow as the result of fires started by the preinvasion aerial bombardments and because the few paratroopers at Piano Lupo had

Road Junction Y, the road to Niscemi at its junction with coastal Highway 115, seen from the Piano Lupo area

lighted a huge bonfire. The beach contours appeared plainly in silhouette.

While the two Ranger battalions on the left were sailing toward shore, a great flash and loud explosion signaled the destruction of the Gela pier in accordance with Guzzoni’s instructions. An enemy searchlight fixed its beam on the boats, but the destroyer Shubrick, designated to render gunfire support if the enemy detected the invasion, immediately opened fire and knocked the light out after five quick salvos. Three salvos destroyed a second light.19 By this time, Italian coastal units were at their guns, and mortar and coastal artillery fire began to fall around the landing craft. The Shubrick and soon afterwards the cruiser Savannah returned a steady stream of naval gunfire.20 Five hundred yards offshore, the Rangers came under machine gun fire, and some Rangers answered, as best they could, with rockets from their bazookas.21 As the enemy fire continued, the Rangers touched down at 0335, fifty minutes late, followed shortly by the 39th Engineers.

Incurring a few casualties from mines on the beaches, losing an entire platoon from one company to enemy rifle and

Italian prisoners taken at Gela on D-day

machine gun fire, the Rangers finally cleared the beach defenses and by dawn pushed up the face of the Gela mound into the city. Two companies under Capt. James B. Lyle wheeled to the west and captured an Italian coastal battery of three 77-mm. guns on the western edge of the mound. None of the guns had been fired, although an ample supply of ammunition lay in the battery position. Though the Italians had removed the gun sights and elevating mechanisms, the weapons could still be fired. Captain Lyle decided to turn the guns around, face them inland, and use them, if necessary, against any enemy force moving against his positions. As the two Ranger companies prepared hasty defensive positions straddling Highway 115, Lyle manned the Italian artillery pieces with Rangers who had a working knowledge of this particular weapon. He also set up an observation post in a two-story building from which he could adjust the fire of the captured guns.

In the meantime, the remainder of the special force had worked its way through the city and had established a defensive

perimeter around the northern and eastern outskirts. By 0800, the entire city had been cleared of resistance, two hundred Italians taken prisoner, and a strong line formed facing inland. The three companies of 4.2-inch mortars were ashore and ready to fire. Portions of the town were still burning, and clouds of billowing smoke poured into the sky.

To the southeast, the 26th RCT was coming on strong to link up with the special force. Having met little resistance at the beaches, the 1st Battalion (Maj. Walter H. Grant) by 0900 was nearing Gela, while the other two battalions were across the highway, past the Gela–Farello landing ground, moving slowly inland to cut Highway 117 north of Gela. The 16th RCT had slightly more trouble. Enemy searchlights picked up the assault waves on their way in, but no opposition came from the beach defenders until the troops started to disembark, just two minutes after the scheduled H-hour. From several pillboxes on the beach and from a few scattered Italian riflemen, light and largely ineffective fire fell upon the leading American infantrymen, then petered out. Yet vigorous enemy machine gun fire from apparently bypassed positions struck the second wave. Even after these positions were eliminated, the Italians continued to be active, firing mortars and artillery against the third and fourth waves, which landed after 0300. Not until 0400 when supporting naval guns opened up—from the cruiser Boise and the destroyer Jeffers—did the enemy fire begin to diminish.22

Holding one battalion in reserve, Colonel Taylor sent two battalions of his 16th Infantry toward Piano Lupo in order to link up with Colonel Gavin’s parachute force. The leading battalions made contact with Company I, 505th Parachute Infantry, which had been holding the southern portion of Piano Lupo since early morning, but they were unable to locate the sizable numbers of paratroopers they expected.

Thus, by 0900 on 10 July, the 1st Division, with much less difficulty than anticipated, was well on its way to securing the first day’s objectives: Gela, the Gela–Farello landing ground, and Niscemi. Unfortunately, General Allen was unaware that the important high ground in front of the 16th Infantry was not in the firm possession of the paratroopers.

On the far right of the Seventh Army’s assault area, Admiral Kirk’s naval task force brought the 45th Division to offshore positions in the face of a fairly rough sea and heavy swell. The landings in that area had been postponed one hour, but the pitch and roll of the ships, straggling, and confusion dispersed and disorganized the assault waves.23

The 45th Division would land southeast of the Acate River, along a coast line extending fifteen miles in a smooth arc almost devoid of indentation. The stretch of sandy, gentle beach was broken only by a few patches of rocky shore or

The coastline west from Scoglitti

low stone cliffs. The only harbor was the tiny fishing village of Scoglitti, where two rocks jutting above the water marked the entrance to two coves forming a haven for fishing boats. The passage was only some fifty yards wide, with a rocky bottom at a depth of eight feet. A mile southeast of Scoglitti lay the low headland of Point Camerina, a rocky bank about fifty feet high faced by five small patches of underwater rocks. At Point Branco Grande, two miles down the coast, and at Point Braccetto, a little farther along, submerged rocks fronted low cliffs.

Inland was a broad, relatively open plain sloping gradually to the foothills of the mountain core of southern Sicily, which held the cities and larger towns.24 Highway 115 proceeded eastward beyond the Acate River, swinging gradually inland and upward, following a southeasterly course cutting across the center of the 45th Division’s zone through Vittoria (36,000) and Comiso (23,000) to Ragusa (48,000 people), the Seventh Army’s eastern boundary and coordinating point with the British Eighth Army. Seven miles north of Biscari was the Biscari airfield; three miles north of Comiso was the airfield of that name.

Avenues of approach from the assault beaches to the airfields were limited and poor. Between the relatively uninhabited stretch of coast line and the highway there were no good roads. A fourth class road connected Scoglitti with Vittoria; a scarcely better road led from the eastern beaches through the little town of Santa Croce Camerina to Comiso. An unpaved road followed the east bank of the Acate River from the western beaches as far as Ponte Dirillo, while a secondary road connected Highway 115 and Biscari with the junction near Ponte Dirillo.

To insure the capture of Scoglitti (which could be used as a minor port); to narrow the gap between the 45th Division and the 1st Division on the left; and to put the assaulting units on as direct a route as possible to the Biscari and Comiso airfields, General Middleton selected two sets of beaches for his landing, one on each side of Scoglitti, with a total frontage of some 25,000 yards.

Three beaches northwest of Scoglitti—RED, GREEN, and YELLOW—nicknamed Wood’s Hole by the naval force, actually constituted an extension of the 16th RCT’s beaches and were similar in terrain. Lying in an uninterrupted line for almost four miles, the beach area was of soft sand which rose gradually for half a mile to an uninterrupted belt of forty- to eighty-foot sand dunes. Pillboxes were scattered along the beaches, the dune line, and the highway. A few coastal artillery batteries dotted the area.

Two regiments would land there. On the left, Col. Forrest E. Cookson’s 180th RCT would come ashore with two battalions abreast, the left battalion to seize Ponte Dirillo (also a paratrooper objective), the right battalion to take Biscari. On the right, Col. Robert B. Hutchins’ 179th RCT would send its left battalion to seize Vittoria, then the Comiso airfield, the right battalion to capture Scoglitti.

On the division right, Col. Charles M. Ankcorn’s 157th RCT was to land over two beaches southeast of Scoglitti. Included in an area nicknamed Bailey’s Beach, pressed between Point Branco Grande and Point Braccetto, these beaches were quite different from those to the west. Rock formations and sand dunes came almost to the water’s edge, and

rocky ledges jutted into the surf. The beaches, GREEN 2 and YELLOW 2, were small, ten to twenty yards deep, less than a half-mile wide. Neither was suitable for bringing vehicles ashore.

Landing nine miles southeast of the other combat teams and fifteen miles northwest of the 1st Canadian Division, the 157th RCT constituted an almost independent task force. Yet Ankcorn had to get to Comiso as quickly as possible to join with the 179th RCT for a coordinated attack on the airfield. Colonel Ankcorn therefore planned to land a battalion on each of his beaches, the one on the right to move due east to capture Santa Croce Camerina, the left battalion to bypass the town to the north for a direct thrust to Comiso. The RCT’s major effort would follow the left battalion’s axis of advance. All of the 45th Division’s supporting armor, a medium tank battalion, was attached to the 157th.

Enemy forces in the division’s zone were few and scattered, mainly troops from the XVIII Coastal Brigade, right flank units of the 206th Coastal Division (where the 157th RCT would be landing), and a mobile airfield defense group at Biscari. The Hermann Göring Division might be expected to strike at part of the division’s beachhead, but disposed as it was in the Caltagirone area, it posed a more serious threat to the 1st Division’s landings. If the 179th and 157th RCT’s moved fast enough, they would have little to fear from enemy attempts to interfere with their juncture at Comiso.

An unexpected benefit came from the dispersed paratroopers who landed in large numbers in the division’s zone. At the very time the 45th Division started ashore, Captain McGinity’s Company G, 505th Parachute Infantry, was making its way toward Ponte Dirillo; Major Alexander’s 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, was reorganizing preparatory to moving on Santa Croce Camerina; Lieutenant Swingler’s forty paratroopers were reducing an Italian strongpoint along the Santa Croce Camerina–Vittoria road; and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 505th, were creating confusion and havoc in the rear areas of the XVIII Coastal Brigade from the Acate River east to Vittoria.

In a few cases, postponing the division’s landings led to some additional difficulties, particularly in the 180th RCT, the westernmost landing force. The transport Calvert’s crew did a splendid job of getting the landing craft loaded with Lt. Col. William H. Schaefer’s 1st Battalion and into the water. Thirty of the thirty-four boats of the first four waves were circling in the small craft rendezvous area by 0200 and, under guidance of a control vessel, started for shore shortly thereafter. But the Calvert had performed too well. Her small boat waves were far ahead of the others. Just before 0300, as word of the H-hour postponement reached the Calvert, her commander had no choice but to recall the four assault waves to the rendezvous area. When the control vessel arrived back near the transport, the assault waves were in a bedraggled condition: some of the small craft had straggled, others had lost the wave formations and had headed off in various directions. When the control vessel received new orders to take the assault waves in to the beach to meet the new H-hour, she obediently turned to execute the order. The result of this movement back and forth in unfamiliar waters and in complete darkness was that the 1st Battalion, 180th Infantry, landed late and badly scattered. What could be collected of the first wave

eventually touched down on RED Beach at 0445, almost three hours after its start. Parts of the other three waves arrived at brief intervals thereafter.

In contrast, the transport Neville, carrying Lt. Col. Clarence B. Cochran’s 2nd Battalion, had a most difficult time launching her small craft. It took almost four hours to load most of the first four assault waves. At 0337, about three-fourths of the total number of landing craft started in to shore even as the ship’s crew still struggled to get the remaining landing craft loaded and launched. But like the 1st Battalion’s waves, the 2nd Battalion’s first assault waves scattered on the way in, and only five boats of the first wave touched down on RED Beach at 0434, eleven minutes before the first wave from the Calvert. Only three boats from the second wave found the beach, three minutes later. Seven boats from the third wave touched down at 0438, and eight boats from the fourth wave made it at 0500. Fortunately for both of Colonel Cookson’s assault battalions, Italian opposition at the shore line was negligible. Though Italian machine guns fired briefly at the Neville’s decimated second wave, no one was hit.

The rest of both assault waves were scattered from RED Beach 2 in the 16th RCT’s sector all the way down the coast to Scoglitti. Colonel Cookson and part of his RCT staff landed on the 1st Division beach. Instead of a compact landing along twelve hundred yards of coast just east of the Acate River, the 180th RCT was scattered along almost twelve miles of shore line.

Of the 2nd Battalion, only Company F landed relatively intact. With this unit, plus a few men from Company E, Colonel Cochran started inland after first clearing out some pillboxes. Following the secondary road parallel to the Acate River, Cochran’s small force was at Ponte Dirillo by dawn, there to find and join McGinity’s paratroopers. With Cochran in command, the combined American force put a guard on the bridge and then established and consolidated its position on the high ground just to the north to block the coastal Highway 115.

Meanwhile, Colonel Schaefer had gathered what he could find of his 1st Battalion. Just before daylight, he began moving inland across the dune area to the highway. There he paused to reorganize before marching on Biscari.

The landing craft that could retract from the beaches returned to the transport Funston to get the 3rd Battalion, 180th Infantry (Lt. Col. R. W. Nolan), ashore. The first wave was ready to go at 0700 and the commander of the wave’s control vessel, who had been with the Calvert’s waves on the earlier landings, started the wave shoreward. But soon after leaving the rendezvous area, the wave commander noticed that landing craft from other transports were crossing his front and heading toward shore on a northwesterly course. Mistakenly concluding that RED Beach had been shifted, he changed course and followed the other craft. The Funston’s first wave grounded on the 16th RCT’s RED Beach 2, west of the Acate River, as did the second and fourth waves. For some strange reason, the third wave landed on the correct RED Beach at 0800. The 3rd Battalion troops which landed in the 1st Division’s sector, almost 300 men from all units of the battalion, banded together under three officers and started the three-mile trek to the correct beach area. The group crossed the Acate River about 0900, met the battalion’s executive

officer who had landed with the third wave, and moved into an assembly area just inland from the beach, there, in II Corps reserve, to await further orders.

On the other two Wood’s Hole beaches, the landings proceeded more smoothly. The first waves of the 179th RCT touched down either right on time or just a few minutes late against no enemy opposition. The only resistance occurred after daylight, when fire flared briefly from an Italian pillbox against the fifth wave.

Lt. Col. Earl A. Taylor’s 3rd Battalion on the left quickly secured the dune line. After a speedy reorganization, the battalion moved inland, reached Highway 115, and as day broke turned toward Vittoria. Sixty paratroopers of the 3rd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, and three howitzers from Battery C, 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, joined Taylor’s battalion, taking places in the line of march.

Lt. Col. Edward F. Stephenson’s 1st Battalion had turned southeast immediately after landing to work toward Scoglitti. One company remained on the beach to clear enemy installations, while the others pushed along the dune line to Point Zafaglione, which dominated Scoglitti from the north and which proved to be well fortified against a seaward approach. Attacked from the landward side, the Italian garrison of seventy artillerymen quickly surrendered.

At Bailey’s Beach the landings of the 157th RCT proceeded smoothly, although a few landing craft grounded on the rocky ledges thrusting out into the surf.

From the transport Jefferson, Lt. Col. Irving O. Schaefer’s 2nd Battalion started toward shore at 0303. Battling wind and sea, grazed by what appeared to be friendly fires from supporting warships, the control vessel veered off course and at 0355 finally touched down, not on GREEN 2, but on the southern end of YELLOW 2 close to Point Braccetto. A few scattered rifle shots greeted the first Americans ashore but caused no casualties. A machine gun crew surrendered without firing a shot. There was little will here to contest the invasion.

The Jefferson’s second wave veered off even farther to the right. About fifty yards offshore, the boat crews finally woke to the fact that they were heading straight for the rocks at Point Braccetto and into a ten- to twelve-foot surf. Too late to change course, the first two landing craft went broadside into the rocks and capsized. Twenty-seven men drowned, weighed down by their equipment and pounded against the submerged rocks. The other landing craft managed to get to the point without capsizing, and their passengers with some difficulty crawled ashore.25

Six of the seven landing craft from the third wave followed close behind. In vain did the men already on the rocks try to wave off the approaching boats. Only two of the six incoming craft grounded on sand. Four hit the rocky area along the north side of Point Braccetto, and though able to unload their troops and cargo, were unable to retract. The seventh boat, far off course from the beginning,

Landing Heavy Equipment over the causeway at Scoglitti

landed most of Company G north of Scoglitti on the 179th RCT’s beaches.

The first wave from the transport Carroll, carrying Colonel Ankcorn, his RCT staff, and Lt. Col. Preston J. C. Murphy’s 1st Battalion, touched down an hour after the Jefferson’s first wave, a delay caused by the loading and lowering of the assault craft. All six of the Carroll’s waves landed within the next hour on the correct beach—YELLOW 2. No assault troops landed on GREEN 2.

Despite the lateness of its landing, the 1st Battalion was the first to leave the immediate beach area. The 2nd Battalion, disorganized by its troubles with the rocks, spent some time in reorganizing and worked mainly on clearing enemy installations along the shore line. Nevertheless, by 0900 both battalions were pushing inland toward Santa Croce Camerina and Comiso. Though enemy resistance around Point Braccetto and Point Branco Grande had been eliminated, the sandy hinterland behind the beaches made it all but impossible to move the RCT’s vehicles inland to follow the assault battalions. Eventually, after much effort, a third

beach—BLUE 2, south of Point Braccetto—was opened, and the original beaches closed.

Across the entire Seventh Army front by 0900, 10 July, infantry battalions were pushing inland. The assault had been accomplished with a minimum of casualties against only minor enemy resistance. Supporting armor and artillery were coming ashore; mountains of supplies began appearing on many of the beaches; and commanders at all echelons were urging their troops to keep up the momentum of the initial assault.