Chapter 20: Brolo

Only along the north coast was the German withdrawal at any time seriously threatened. For that matter, the entire German northern and central sectors almost fell prey to another American amphibious end run, an operation that for a short time altered Hube’s carefully conceived timetable for the evacuation of Sicily.1

After relieving Colonel Bernard’s battalion at the Rosmarino River on 8 August, Colonel Sherman’s 7th Infantry had pushed on east along Highway 113 against steadily stiffening German resistance. By the evening of 10 August, after being knocked back once, the 7th Infantry gained a foothold across the Zappulla River just south of the highway crossing. The opposing 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment pulled back up the slopes of the Naso ridge roughly in line with Cape Orlando. It had been unable to delay the 3rd Division advance until 12 August, as originally contemplated.

The new German defensive line looked as formidable as that at San Fratello, but Patton, Bradley, and Truscott were not disposed to pick at this line. Even as the 7th Infantry fought to cross the Zappulla River, Truscott sent Johnson’s 15th Infantry inland to cross the river south of Sherman in order to gain the ridge below Naso and roll up the German line. This was to be the division’s main effort. General Patton, however, had another idea on how he could more quickly reduce the Naso ridge position.

Wanting desperately to get to Messina ahead of the Eighth Army and “trying to win a horse race to the last big town,”2 Patton called General Bradley to his command post on 10 August and ordered an amphibious end run for the next morning. The maneuver was to be similar to the

one executed three days before. Patton had wanted to launch the operation on the morning of the 10th in conjunction with the 15th Infantry’s turning movement, but a Luftwaffe attack the evening before had sunk one of the LSTs earmarked to lift the task force. This setback, together with the 7th Infantry’s trouble at the Zappulla, induced the Seventh Army commander to call off the operation for twenty-four hours.3 Now Patton was in no mood for another postponement, and he left no doubt in Bradley’s mind of this fact.

Patton was not the only American who was keen on beating Montgomery into Messina. Of late, several unfortunate remarks had allegedly been made by the British Broadcasting Corporation (the BBC)—the going on the Seventh Army front had been so easy that the troops were eating grapes and swimming while the Eighth Army was fighting hard against strong German opposition. Because the BBC was the principal radio service heard by all the troops in Sicily, Americans were quite upset by the disparaging comments. Many an American, like Patton, wanted to get to Messina ahead of the British in order to give the lie to these remarks.4 Besides, the Seventh Army’s capture of Palermo, its rapid and successful dash across western Sicily, and its entire conduct thus far in the campaign had whetted American appetites for the greater prize: to beat the proud and vaunted Eighth Army to Messina. The success of the Seventh Army had, for the first time, enabled Americans in the Mediterranean theater to hold their heads high among British and other Allied soldiers, who had been somewhat doubtful of the American soldier’s ability after Kasserine.

General Truscott, initially at least, agreed with the plan. He apparently felt that the flanking 15th Infantry could occupy the Naso ridge on the evening of 10 August. This would put the 15th in position to link up quickly with the amphibious task force.

But the 15th Infantry did not get to the Naso ridge on the 10th. Although one battalion progressed as far as the little town of Mirto, overlooking the river, enemy fire from across the way forced a halt and delayed the arrival of the other two battalions. Not until 2100 did the last of the battalions close in the new area. In addition, the lack of roads prevented artillery units from displacing forward to support a further advance. These factors, and the rough terrain, prevented any move by the 15th Infantry across the Zappulla River that evening.

With things not working out as he had planned, Truscott wanted to postpone Bernard’s landing for another twenty-four hours. When the Bernard task force had been established, General Keyes had assured Truscott that the force would be entirely under Truscott’s command and that he would have the responsibility for the timing of any operation involving the force. A delay, Truscott believed, would permit both the 7th and 15th Infantry Regiments to get into better positions from which to move forward to effect a quick link-up with the seaborne forces. As the situation on the evening of 10 August appeared to him, Truscott doubted that the two regiments could get through the Naso ridge positions fast

Pillbox overlooking Highway 113, east of the Zappulla River crossing

enough to save Bernard’s small force from the expected German reaction.

When General Keyes arrived at the 3rd Division’s command post that evening to see how the planning was coming along, Truscott informed the deputy commander of his desire to postpone the end run. Knowing full well Patton’s intense feeling, Keyes replied that he doubted whether the army commander would agree to any postponement. Furthermore, Keyes said, Patton had arranged for a large number of correspondents to accompany Bernard’s force, and Patton would not relish having to tell the writers that the end run had again been delayed. Patton wanted no unfavorable publicity for the Seventh Army.

Nevertheless, Truscott picked up the telephone and called General Bradley. He explained the situation to the II Corps commander and his desire to postpone the landing. Bradley agreed, and tried to get Patton to agree. But his plea fell on deaf ears. Patton insisted that the landing proceed as scheduled. Shortly thereafter, Keyes called Patton and stated that Truscott did not want to carry out the landing. Truscott, called to the telephone, tried to explain his reasons for wanting to delay, but Patton was in no mood to listen. “Dammit,” Patton said, “The operation will go on.” In the face of this bald statement, what could Truscott do? He issued orders to Bernard to load his force for the landing.

Link-up. This was what worried Truscott. How to effect a quick link-up became

Cape Orlando (extreme left center) with Naso ridge rising inland. The railway can be detected running along the coast line. Route 113 hugs the base of Naso ridge

the major problem at the 3rd Division’s command post the evening of 10 August. At the time Patton brusquely concluded his telephone conversation with Truscott, no 3rd Division battalion was within ten miles of Bernard’s objective—Monte Cipolla, a steep hill about midway between the Naso and Brolo Rivers which dominated the coastal highway and the ground to the east and west.5 The coastal highway constituted the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division’s main escape route to the east, and Truscott knew that German reaction to Bernard’s landing would be swift and heavy. Accordingly, the 3rd Division commander committed every element in the division, including the recently attached 3rd Ranger Battalion, to break through the Naso ridge line defenses. From left to right he deployed the remainder of the 30th Infantry, then the Rangers, then the 7th Infantry, and, finally, the 15th Infantry.

Even as General Truscott prepared his link-up plan, the bulk of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division continued to hold its portion of the Tortorici line. Farther to the south, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division

Brolo Beach, from the east, showing the nose of Monte Cipolla

was holding the 9th Division at bay along the Simeto River, although it was then in the process of pulling back into Randazzo.

Immediately in the rear of General Fries’ main line of resistance along the Naso ridge, a fairly strong German force was stationed in and east of the town of Brolo maintaining guard along the north coast against the kind of landing the Americans had made at San Fratello. Under Col. Fritz Polack, it consisted of the 29th Artillery Regiment, containing the regimental headquarters; the headquarters of the regiment’s antiaircraft artillery battalion with two 20-mm. four-barreled antiaircraft guns; and parts of the 1st Battalion, 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment. Polack had located his headquarters on the northeastern slopes of Monte Cipolla; the bulk of his troops stretched eastward along the coast from Brolo.

At 1800, 10 August, Colonel Bernard’s troops completed loading near Caronia and put to sea—one LST, two LCIs, and six LCTs covered by the Philadelphia and six destroyers. At 0100 the next morning (11 August) the small task force arrived some three thousand yards off the landing beach, and the troops quickly loaded in LCVPs and Dukws for the final run-in. Thus far, Colonel Polack’s beach defenders showed no sign of having discovered the amphibious force.

The terrain in the landing area was dominated by Monte Cipolla, the base of which lies some 450 yards inland from the beach, the top of which—divided into two small knobs—reaches an altitude of some 750 feet. The slopes are precipitous, and the northeast nose—on which Polack’s headquarters was located—constituted the only usable approach to the knob nearest the beach. The terrain inland from the beach rises in terraces to the base of the hill. The terraces themselves are stone-faced, and many other stone fences and drainage ditches criss-cross the area. Covered with lemon trees, this area was soon to be called “the flats.” Parallel to the beach and only a hundred yards inland, a thirteen-foot railroad embankment, through which ran several small underpasses, extended east and west bisecting the flats, while the coastal highway, another three hundred yards inland, skirted the base of Monte Cipolla.

Colonel Bernard’s plan for the operation was fairly simple. He planned to land Company E and the naval beach marking party at 0230 in the first wave. The rifle company was to destroy any beach defenses, clear the lemon grove between the railroad embankment and the highway, and block the entrances to the beach from the east and west. Fifteen minutes later, the tank platoon and the platoon of combat engineers were to land: the tanks, to reinforce Company E, the engineers, after assisting the tanks ashore, to make ready to receive the two self-propelled artillery batteries scheduled to land in the fourth wave. In the third wave, due to land at 0300, Bernard put his headquarters and the other three lettered companies of the infantry battalion. Companies F and G were to make their way up Monte Cipolla, with Company F to occupy the knob nearest the coast. After landing, Company H was to send one section of machine guns to each of the rifle companies and a section of 81-mm. mortars to each of the two companies on the hill. Finally, at 0315, the two field artillery batteries, the naval gunfire liaison officer, and fifteen mules (the battalion’s ammunition train) were to land. The artillery batteries were to go into

Enemy view of landing area at Brolo, from the northeast nose of Monte Cipolla

position in the lemon grove in the flats with Battery B firing to the west, Battery A to the east. Once established on their objectives, the units were to dig in, block any German attempt to withdraw to the east from the Naso ridge, and defend until relieved by the main portion of the 3rd Division.

The final run-in to the beaches started at 0210. At 0243, thirteen minutes late, the first wave touched down. (Map 8) Company E streamed from its five LCVPs and splashed ashore against no opposition. Quickly cutting passages through a double-apron barbed wire fence twenty yards inland, the rifle company crossed the railroad embankment and paused briefly to reorganize. Pushing on, the company soon cleared the lemon grove, capturing ten Germans in the process without having to fire a shot. As one rifle platoon and the weapons platoon swung to the right to block the Naso River crossing, the remainder of the company turned to the left to block the railroad and highway bridges across the Brolo River.

The second wave landed almost on the heels of the first. Although the tanks moved quickly up to the railroad embankment, intending to go through the several underpasses to support Company E, the passageways proved too small. As the tank platoon leader dismounted to search for a way around the obstacle, an Engineer officer appeared and offered his services in seeking a way either around or over the embankment. His offer accepted, the Engineer officer rushed off one way, to the east, while the tank platoon leader headed in the other direction.

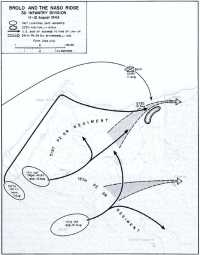

Map 8: Brolo and the Naso Ridge 3rd Infantry Division, 11–12 August 1943

Right on schedule, part of the third wave—Companies F and G in LCTs—landed, followed in another fifteen minutes by sixteen Dukws carrying the rest of the wave: Bernard, his headquarters, and Company H, which promptly dispatched its sections to support the rifle companies. The Dukws continued inland following the two rifle companies until they, too, had to halt because of the railroad embankment. At 0330, the fourth and last wave touched down; by 0400, Bernard’s entire force was ashore without loss. By this time, Company E was in its blocking positions.

Companies F and G reached the highway without incident at 0345. At the railroad, the Engineer officer returned to the tanks and reported that he had found a way around the thirteen-foot high embankment, via the Brolo River bed. The tank officer had not yet returned, so the Engineer officer offered to guide the two artillery batteries into position. His offer was accepted and the artillery pieces started to move slowly toward the east. The tank commander returned about this time and said that he, too, had located a bypass route, via the Naso River bed, and he started his tanks moving toward that exit.

Even as the tanks and artillery pieces began moving out, half of Companies F and G crossed the highway and began ascending Monte Cipolla by its northeast nose, close to the junction of Highway 113 and the secondary road which wound inland to the small mountain town of Ficarra. Thus far, not a shot had been fired. Colonel Polack’s coast defense units showed no signs of having discovered the landing.

A German motorcycle, apparently heading for Naso, suddenly came roaring down the highway. Freezing in place, the Americans allowed the motorcycle to pass. They then continued crossing the highway and ascending Monte Cipolla’s slopes. The element of surprise still might have been maintained had not a German half-track approached from the west. Seeing troops on the road, the driver halted his vehicle. As he rose from his seat to see whose troops these were, some twenty anxious American riflemen opened fire. The driver slumped back in his seat, dead. Seconds later, a small sedan with two occupants pulled up behind the half-track. A German officer stepped out to see what had happened. A well-placed bazooka round exploded the car, killing the officer and wounding the driver.

The noise of the rifle fire and the exploding of the bazooka round woke all Germans in the neighborhood, including Colonel Polack and his headquarters troops on Monte Cipolla. Gathering fifteen men around him, Polack opened fire on the leading elements of Companies F and G. Machine guns in Brolo began to fire seaward, while other machine guns and the 20-mm. guns located on high ground east of Brolo opened up on the landing beach. By the light of flares, Polack’s men delivered accurate machine gun fire that cut down several of the Americans. But the rest pushed on, grabbing at long shoots of grass and small bushes to pull themselves up the steep slope.

Seeing that his headquarters personnel could not stop the Americans, Polack gathered up the unit’s classified documents (including Hube’s evacuation order of 10 August) and made his way down the far slopes of the hill into Brolo. Here, from a nearby switchboard, he called General Fries and informed the division commander

Digging in a machine gun position on Monte Cipolla, 11 August

of the situation. For the first time, Fries knew that the bulk of his division was in danger of being cut off. He ordered Polack to attack the American beachhead as soon as possible, using the elements of the 1st Battalion, 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the antiaircraft unit, and a few German tanks located east of Brolo.

Companies F and G managed to reach the top of Monte Cipolla at 0530; within thirty minutes both companies were dug in. Down on the flats, however, the artillery and tanks were having a difficult time trying to get into position to support the rifle companies. Three of the tanks bellied trying to cross ditches on the beach side of the railroad; the last two were damaged trying to knock down stone fences. Though the tanks could be used as fixed guns, their inability to maneuver made them practically useless in the action that was soon to follow. The artillery batteries were more fortunate, and though they had difficulty traversing ditches and terraces, they managed to get around the embankment and into firing positions before daylight in the lemon grove north of the highway.

With the coming of daylight, Polack’s men in Brolo turned their guns from the beaches and began sweeping the eastern slopes of Monte Cipolla. Bernard’s men soon found it hazardous to make the long climb down to the beach, and those on the beach found it equally hazardous to climb up. Some fifteen men—mainly communications personnel and ammunition bearers—were killed during the course of the early morning trying to work on the slopes of the hill. The battalion’s mule train carrying badly needed ammunition from the Dukws up to the machine guns and mortars on top of the hill lost all but two of its fifteen animals to the German fire. From this time on, ammunition resupply was hazardous, spotty, and largely unsuccessful.

Trying to aid Bernard’s men, the Philadelphia had opened fire shortly after 0530 at prearranged targets in the area, and then shifted her fires under the shore party’s direction to Polack’s units massing to strike back at the seaborne force. To the west, General Fries had ordered the 6th Company, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (then deployed in a reserve position near Naso), to attack the American beachhead from the east. He also ordered a smaller German force at Ficarra to attack the Americans he now knew to be on Monte Cipolla.

The first German ground reaction noted by Bernard’s companies came at 0700 when the Germans from Ficarra sent two reconnaissance vehicles down the secondary road to probe the American lines. Company G allowed the two vehicles to come close, opened rapid fire, set the vehicles on fire, and scattered the occupants. Shortly thereafter, the main German force of thirty men began working their way down the Brolo River bed. Again Company G allowed the Germans to come close before opening fire. Dropping in mortar concentrations and opening up with the heavy machine guns, Company G proceeded to decimate the German force. The survivors beat a hasty retreat up the river bed, dragging their wounded with them.

For almost an hour the situation remained fairly quiet. Then, the 6th Company—about one hundred strong—made its effort down the Naso River bed, marching boldly forward. Engaged by Company H’s machine guns, the Germans stopped and began deploying. But before they could get into an extended formation, Company H’s mortars opened fire, and round after round dropped in on the German company. Trapped between the high banks of the river, the Germans broke and ran. The Americans estimated they killed and wounded at least seventy of the attacking force. This thrust proved to be the last German attack from the south, and this sector remained fairly quiet until after darkness fell.

General Fries, nevertheless, continued his efforts to knock Bernard’s men off their lofty perch. Placing heavy fire on all points on the hilltop and on the slopes of the hill, the German commander at 0900 started a truck-borne infantry column—another of his reserve units—eastward from Cape Orlando toward the Naso River. Fries was deliberately weakening his Naso ridge positions in attempts to open a way to the east. He had to regain control of the coastal highway if he expected to get the bulk of his division out of the American trap.

The Philadelphia spotted the German column and opened fire, knocking out several vehicles and forcing the rest to leave the highway. Continued firing

scattered the German infantrymen. Thirty minutes later, an artillery forward observer on Monte Cipolla spotted two German tanks with some infantry on the highway, also moving toward the Naso River. Bringing Battery A in on the target, the forward observer forced the tanks to leave the road well before they could reach the river, and the German infantrymen to seek shelter north of the highway.

By this time, Bernard’s 81-mm. mortars, because of the mule train’s failure to get up the hill, were low on ammunition and could fire only harassing missions in support of the artillery batteries. Bernard’s firepower was reduced even further when, at 1025, the Philadelphia and her covering destroyers set a course for Palermo. Having attended to all the prearranged targets and having received no more requests for fire after the shoot on the truck convoy, Admiral Davidson figured that his task had been accomplished and that the two field artillery batteries could handle any further German threat. Thus far, only four enemy aircraft—Italian torpedo-bombers—had made any sort of threatening gesture toward the American warships, but Davidson felt that the longer he lay off Brolo the greater the danger that enemy air would strike at his ships. Since he was assured of Allied air cover only until 1200, Davidson thought it wise to have the protection of the shore-based Allied antiaircraft guns at Palermo.

To the west and across the Naso ridge, the units of the 3rd Division which General Truscott had so carefully lined up the preceding evening had started their attacks to break Fries’ hold and link up with Bernard’s force. In his command post on the eastern edge of Terranova, Truscott anxiously awaited the outcome of the drive. Having committed everything he had to the effort, there was nothing more he could do but wait. Leaving nothing to chance, Truscott had dispatched a liaison officer, Capt. Walter K. Millar, with a powerful jeep-mounted radio, to go along with Bernard’s force. Through this radio, Truscott hoped to keep track of the situation at Monte Cipolla. Throughout the early morning, starting at 0600, Millar’s messages were most reassuring, and General Truscott began to feel better even though the progress of his other units up the Naso ridge was slow in the face of extensive German mine fields and of light to heavy German fire.

The German division was in a bad way. By noon, Fries had pulled the bulk of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment back behind the Naso River. Near the coast, the 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment was caught between the 7th Infantry on the west and Bernard’s battalion on the east. Whereas the 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had a relatively free and protected route to the rear from the Naso ridge—by moving cross-country through Ficarra to San Angelo di Brolo (on the first defensive phase line as laid down by General Hube)—the northern German regiment had only the coastal highway for withdrawal. Fries ordered the regiment to fight to open a way to the east by falling back off the Naso ridge, first behind the Naso River, then behind the Brolo River, and then to Piramo, the northern hinge of Hube’s first phase line. With these orders Lt. Col. Walter Krueger, commanding the 71st, began assembling what troops he could spare to try to force a passage along the highway. Krueger also turned one of his attached field artillery battalions around and began firing to the east.

Colonel Polack continued his efforts to

Lt. Col. Lyle A. Bernard and his radioman in the command post atop Monte Cipolla

assemble his scattered units for an attack against the American beachhead. By 1100, Polack managed to get together two infantry companies mounted on personnel carriers plus several tanks, brought them into Brolo, and began probing toward Company E along the Brolo River.

Polack’s assembling of troops did not go unnoticed on Monte Cipolla. Company H’s mortars began firing slowly on the town. Battery B joined in, but, because of the short range, encountered some difficulty in placing effective fire on the town. Polack sent snipers and machine guns into the buildings overlooking the river to keep up a steady fire on the single American rifle platoon guarding the highway bridge. At 1140, seriously worried by this new German threat, Bernard began relaying messages by radio through Company E to Captain Millar requesting an air strike and naval gunfire on Brolo. Twenty minutes later, Bernard asked for long-range artillery support: the 3rd Division had some attached 155-mm. guns (Long Toms) that could reach Brolo, although the town was at the extreme range of these guns.

Bernard’s first message caused a stir at Truscott’s command post in Terranova.

The 3rd Division commander did not know that Admiral Davidson had withdrawn the warships and he could not understand why Bernard was asking for naval support. Thinking that Bernard’s shore fire control party’s radio had gone bad, he got several of his staff officers to telephone urgent messages to Seventh Army for naval and air support. These requests had just gone out when Bernard’s second message came in. Truscott ordered the 155-mm. guns—though firing at the maximum range—to open fire on Brolo. At the same time, he renewed the requests for naval and air help. Word on the naval support was slow to arrive, but Seventh Army stated that the XII Air Support Command had promised an air mission, although it could not give a specific time when the mission would be flown or the number of planes to participate. General Truscott was really worried now—his forward units were still moving slowly up the Naso ridge, but they were still some hours away from a linkup. He knew Bernard’s force was too small to beat off a serious German counterattack.

Actually, help was already on the way. Just as Admiral Davidson’s warships were about to enter Palermo harbor, the Admiral received word from TF 88’s liaison officer at the Seventh Army of Truscott’s urgent request for gunfire support. Turning the cruiser back to the east, taking two destroyers along to cover, Davidson sped back along the coast, and shortly after 1400 began firing on Polack’s troops in and around Brolo. By this time, Bernard was adjusting the 155-mm. guns on Brolo. And just as the Philadelphia opened fire, the air strike materialized in the form of twelve A-36’s that dropped bombs on Brolo and on the area just east of the town. Thirty minutes later, twelve more A-36’s zoomed in over the area and strafed the German assemblage.

The combination of American fires proved too much. Polack’s men scattered, trying to avoid the rain of American shells. Three German tanks remained in Brolo, however, huddled near the stone buildings, and escaped damage. Unfortunately, at just this moment, the shore fire control party’s radio link with the Philadelphia stopped functioning. Not wanting to fire on targets without shore control, and since friendly air seemed to have the situation well in hand, Admiral Davidson at 1505 withdrew his warships a second time and turned again for Palermo.

Now a new threat to Bernard’s beachhead appeared. On the west side of the Naso River, Colonel Krueger had managed to get together a battalion of infantry for an attack across the river. The rest of his regiment he left in position to delay any American attack from Naso or Cape Orlando. At about the same time, General Truscott left his command post to visit his forward regiments; he wanted personally to urge them on with all possible speed. Truscott, because of the German mines and demolished roads, could reach only the 30th Infantry which was then trying to cross the coastal flats into Cape Orlando. From Colonel Rogers’ command post, Truscott called Colonel Sherman and told the 7th Infantry commander to forget the town of Naso and push forward as quickly as possible on Rogers’ right.

The 1st and 3rd Battalions, 30th Infantry, began crossing the Zappulla River at 1420 under a smoke screen laid down by supporting chemical mortars. The 1st Battalion soon ran into terrain that was heavily mined and booby-trapped, and

moved only slowly through the coastal flats toward Cape Orlando. The 3rd Battalion also was slowed by much the same type of obstacle, but it managed to keep pace with the 1st Battalion. The 7th Infantry renewed its attack at 1500 straight up the west slopes of the Naso ridge, but its advance, too, slowed in the face of extensive mined areas. Along the ridge, Colonel Krueger’s remaining defenders strengthened the mined areas with sporadic artillery fire, frequent periods of heavy small arms fire, and with just enough infantry action to keep the American units from rushing quickly forward.

Within the beachhead, the situation worsened by the minute. After the withdrawal of the American warships, and the ending of the air strike, the three German tanks that had taken shelter in Brolo, supported by a few infantrymen, started toward the eastern end of the highway bridge. The one American platoon guarding the bridge crossing managed to drive off the German foot soldiers, whereupon, the tanks halted just at the river’s edge and opened fire on this annoying group of Americans. At the same time, Polack’s 20-mm. guns (undamaged by either the naval or air strikes) resumed heavy firing on the flats and on Monte Cipolla’s slopes. From the west, Krueger’s field artillery battery joined in. On Monte Cipolla, Bernard rushed off another message to General Truscott: “Repeat air and navy immediately ... Situation still critical.”

Again, Admiral Davidson was flashed the word that his guns were needed at Brolo; again, the XII Air Support Command promised another air strike, again without mentioning numbers of planes or time of mission.

Before either Davidson’s warships or Allied planes could come to Bernard’s aid, the three German tanks crossed the Brolo River. The platoon of American infantrymen scattered, most moving toward the beach to join with the other platoon at the railroad bridge. As the tanks waddled slowly down the highway, Battery B tried to engage them with direct fire, but a high wall near the bridge not only limited observation but also prevented the howitzers from opening fire. German infantrymen, who crossed behind the tanks, turned to engage the Americans near the railroad bridge. The tanks continued moving slowly along the road, seemingly intent on going through the American beachhead. Battery B tried to displace to positions from which it could fire on the tanks, but the Germans spotted this movement. In the ensuing fire fight, the tanks knocked out two of the American guns and two ammunition half-tracks. The exploding ammunition drove the Battery B crews from their other two guns, although one crew returned to its vehicle and moved it onto the highway, just around a bend in the road. No sooner had it gone into position than the lead German tank rounded the bend. The American artillery crew fired first, and missed. Then the tank fired, and also missed. The second rounds from both vehicles, fired almost simultaneously, struck home. Both the tank and the self-propelled gun started to burn furiously.

From Monte Cipolla, Company F, overlooking the fight below, sent a shower of rifle fire on the other two German tanks without much effect. Company H’s mortars and machine guns remained silent, hoarding their few remaining rounds for a last-ditch stand.

On the right, Battery A had finally managed to maneuver its guns into position

to fire on the last two German tanks. The battery set one on fire, whereupon the last turned and trundled slowly back to the east. Before recrossing the river into Brolo, the tank paused for a brief moment to destroy the unmanned but still serviceable Battery B howitzer. The German infantrymen followed the tank back across the river.

Worried about Company E, Bernard started Company F down Monte Cipolla to take over the Brolo River defenses, telling Company F’s commander to send what he could find of Company E to the Naso River to defend from that direction. One platoon of Company E was still in position there, and Bernard hoped that by consolidating the remnants of Company E into one group, he could use it to hold on to the highway crossing. Because of continued German fire, Company F’s progress down the hill was slow, and it was almost 1600 before the company debouched on to the flats and moved to the river line.

Unfortunately, Company F’s arrival in the flats coincided with the promised air strike. Seven A-36’s swept in low over Monte Cipolla at just about 1600. Apparently not fully oriented to the ground, the pilots dropped two bombs on Bernard’s command post, killing and wounding nineteen men, and the rest on Battery A’s howitzers. Though Company F was unscathed, when the smoke cleared the infantrymen discovered that the four remaining artillery pieces had been destroyed. With nothing left to support the two companies in the flats, Bernard ordered everybody up onto Monte Cipolla. Bernard figured the time had come to make his last-ditch stand.

The Philadelphia arrived back on the scene just as Bernard finished ordering everybody up out of the low ground. Seeing the vessels, an officer from the shore fire control party commandeered a Dukw to take him out to the cruiser to get supporting fires. Through some misunderstanding, three of the other Dukws (all loaded with ammunition) followed. An artillery officer took a fifth Dukw to recall the three carrying ammunition. Thus, practically all of the task force’s remaining ammunition supply headed out to sea. The Dukws managed to make the cross-water run successfully. After taking the men aboard, the cruiser began firing on Cape Orlando, Brolo, and the highway east of Brolo. Admiral Davidson did not want to bring the fires in any closer to Monte Cipolla.6

After about fifteen minutes of naval fire, just before 1700, eight German aircraft struck the three American warships. In a brisk thirty-minute fight which featured violent evasive actions by the ships, near misses from German bombs, and the appearance of friendly aircraft, only one German plane managed to make its escape. The cruiser claimed five of those shot down. Again, Admiral Davidson decided to withdraw his warships. He was still devoid of communications with Bernard’s force; his ships were still prey for enemy air attacks. He could see nothing that he could do to ease Bernard’s situation. Again, the warships set a course for Palermo, this time going all the way.

Company F, with men from the engineer platoon and the artillery batteries, got back up on Monte Cipolla before complete darkness set in. Bernard expended the last of his mortar ammunition in a concentration

on a suspected German assembly area across the Naso River. This he followed with rifle and machine gun fire on the bridge to cover Company E’s disengagement. The latter unit, still badly disorganized, began dribbling in to Bernard’s command post a short time later. Some of the company never made it to the hill, but dug in on the flats for the night, fighting as best they could with rifles and hand grenades against the retiring German columns. Bernard passed the word for the units on Monte Cipolla to break into small groups and move back toward the 3rd Division’s lines as soon after daybreak as possible.

By 1900, the 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment was in control of the highway and a narrow stretch of land on each side. Glad to have opened an escape route, it paid little attention to Company E’s survivors still in the flats. At 2200, Colonel Krueger began withdrawing his units to the east, taking with him his vehicles. Krueger made no attempt against Monte Cipolla.

At his command post in Terranova, General Truscott was becoming increasingly worried about Bernard’s small force. Captain Millar, before ascending Monte Cipolla, had sent one last message just before 1900 to General Truscott and then destroyed his radio set. Only part of the message (which asked again for naval support) got through; General Truscott felt that the small American force had been overrun before the complete message could be dispatched: he could see “the final German assault swarming over our gallant comrades.” To add to his worries, both the 7th and 30th Infantry Regiments reported they had lost contact with their leading battalions; the units had outrun their communications with the regimental command posts.

Unknown to General Truscott, both regiments by 2200 had gained the Naso ridge and were even then starting down the eastern slopes to link up with Bernard’s force. By this time, the bulk of Colonel Krueger’s regiment had made good its escape to the east, past the trap which had been so neatly set but which could not be held.

The 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, crossed the Naso River and entered the flats. Men from Company E leaped from their hiding places to greet the relieving force. Patrols were immediately dispatched to Monte Cipolla to locate Colonel Bernard, who, hearing the sounds of firing which marked the approach of the bulk of the division, rescinded his previous instructions for the men to make their way to the east after daybreak. At 0730, 12 August, Bernard made contact with a 1st Battalion patrol. His force—minus 177 men killed, wounded, and missing—came down off the hill.

The 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry, moved through to take up the pursuit of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, which had been forced to give up its portion of the Tortorici line twenty-four hours ahead of time. For a short while, this withdrawal had posed a threat to General Rodt’s evacuation of Randazzo. But the 29th was able to slip into position in front of Patti, where Rodt’s escape route from Randazzo came out to the north coast. Here, aided by the terrain, Fries was not only able to gain back the day he had lost, but to hold open Rodt’s escape route as well.

Except for forcing General Fries to give up the Naso ridge a day ahead of time, no mean feat considering the natural defensive strength of the position, Bernard’s landing accomplished little. But the

operation had come close to trapping a large part of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, and had come even closer to rolling up the whole northern sector of Hube’s defensive line. It was only because Bernard’s force was too small, and because continuous air and naval support was not available, that Hube’s entire northern flank was not rolled up and cut off from Messina. If a stronger force had been landed—at least an RCT—and if continuous naval and air support had been provided, General Fries could hardly have cleared a way out of the trap along the coastal highway.

Operations against the rear of the German defensive line undoubtedly would have eased the way for the bulk of the 3rd Division, and would have made for a quicker link-up. Pressure from front and rear might have so hampered Fries’ regiments that probably few if any of the Germans could have made their way to the east. With Fries’ division out of the way, advance east along Highway 113 might have been virtually unopposed. In conjunction with American advances from Randazzo, General Truscott might have effectively severed General Rodt’s withdrawal routes to Messina. This, in turn, might have led to a rapid dash into Messina where at least a part of the Hermann Göring Division could have been prevented from making good its escape.

As it turned out, the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, which suffered about the same number of casualties as the 3rd Division, made good its get-away. It managed to withdraw most of its heavy equipment to Hube’s first phase line just east of Piraino—three miles from Brolo—thus holding open Rodt’s escape route to the north coast. If the German division’s morale was damaged by this second American amphibious end run—and it must have been—its physical capability for fighting more delaying actions was only slightly weakened.