Chapter 27: The Japanese Revise Their Strategy

In war something must be allowed to chance and fortune, seeing it is in its nature hazardous and an option of difficulties.—GENERAL JAMES WOLFE, 1757

Viewed from Tokyo, the war by September 1943 had reached a critical stage. The defeat at Midway in June 1942 followed by the loss of Guadalcanal and Papua early in 1943 had been serious but not fatal blows. More serious had been the loss of ships and pilots, and these, it was hoped, would ultimately be replaced. But MacArthur’s and Halsey’s victories in the Solomons and New Guinea during the summer of 1943 cast a more serious light on the situation. Obviously the Allies were making a determined assault on the Solomons, eastern New Guinea, and the Bismarck Archipelago, which the Japanese called the Southeast Area. Failure to hold the outposts in New Guinea and the Solomons, they recognized, could have disastrous consequences and might well be the prelude to an Allied advance toward Truk and the Philippines.

The Allied drive from the south was not all the Japanese had to worry about; danger lay also to the north and to the east. In May 1943 they had lost Attu and in July they had been forced to evacuate Kiska. Though there were no signs of an early offensive from the Aleutians, this was a possibility the Japanese could not overlook. The threat from the east, across the Central Pacific, was more immediate. American fast carriers had recently struck Marcus Island, Wake, and Japanese bases in the Marshalls, and American forces had occupied islands in the Ellice group, south of the Gilberts. All this activity, the Japanese reasoned correctly, could only mean the Allies were preparing to launch an offensive in the Central Pacific in the near future. Clearly, the time had come for a reassessment of Japan’s military and political situation and a realistic appraisal of her prospects for the future.

The New Operational Policy

The review of Japan’s position in mid-war was sparked by Imperial General Headquarters early in September with a comprehensive “Estimate of the

Enemy Situation.”1 The Allied offensive, the Japanese planners believed, would increase in intensity rather than diminish in the days ahead, and could be expected to reach its peak probably by the early summer of 1944. During the remainder of 1943 and through 1944, the Allies, they thought, would make a concentrated effort to capture Rabaul and other strategic positions in the South and Southwest Pacific, while opening offensives in Burma, Sumatra, and the Indian Ocean area. If the Allies succeeded in taking Rabaul, they would almost certainly drive next for the Philippines and the Mandated Islands, the Japanese believed. Oddly enough, they did not expect a “large-scale enemy offensive” in the Central Pacific, at least in 1943, because of the weakness in carrier strength.

Just what the Japanese meant by a “large-scale” offensive is not clear. Certainly it did not mean operations against the Gilberts, Nauru, Wake, or Marcus, for these were definitely considered possible Allied moves to be undertaken in concert with the offensive against Rabaul. The Allies could be expected also, if the opportunity offered, to invade the Kurils and the Netherlands Indies, to disrupt Japanese sea communications, and to bomb the occupied areas and even Japan itself.

The situation on the Asiatic mainland was no better. On review, the Japanese planners could discern no reason to believe that the Soviet Union would change its policy toward Japan and join the Allies in the Far Eastern war. But they did think Stalin might permit the United States to use air bases in Eastern Siberia. For this reason the planners held that Japan would have to maintain strong forces in Manchuria as well as in China, where there was every prospect of increased Allied air activity.

In this, situation, Imperial General Headquarters found little cause for optimism. The enemy had gained aerial supremacy in the Solomons and eastern New Guinea, and, despite the courageous efforts of Japanese troops in the area, was continuing to advance. Elsewhere, the outlook was no brighter; everywhere the Japanese turned they faced the prospect of actual or potential Allied offensives. “In short,” the Deputy Chief of the Army General Staff predicted gloomily, “the situation will develop steadily toward the decisive stage and we are rapidly approaching a crucial stage which may well decide the fate of our country.”2

Japanese estimates of Allied strength were fairly accurate. Ground and air forces arrayed against them they placed at 23 divisions and 2,500 planes of all types. This was only “front-line” strength; total strength, including reserves,

the planners at Imperial General Headquarters placed at 6,000 aircraft and 70 to 80 divisions. The rate of increase of these forces depended, the Japanese recognized, on a variety of factors: the situation in Europe, shipping, and U.S. production. But even assuming the Allies gave first priority to the war against Germany, the Tokyo planners reckoned that the Allies would have 4,000 aircraft and 35 divisions available for operations against Japan at the end of 1943. A year later, this total would have jumped to 7,000 aircraft and 60 divisions, assuming a shipping capacity of four to five million tons.

The main naval strength of the Allies, the Japanese knew, was concentrated in the U.S. Pacific Fleet operating out of Pearl Harbor. The nucleus of this fleet, they estimated correctly as consisting of about 6 large aircraft carriers, 15 battleships, and 15 cruisers, organized into several forces.3 Separate task forces, including 10 converted aircraft carriers, were believed to be operating in the Alaska-Aleutians area and in the waters off Australia. Allied submarines, which were responsible for the bulk of their shipping losses, the Japanese estimated at about too. Of these, by far the greatest number, about 80, were believed to be American; the remainder, British. Operating bases for the underwater craft were correctly located in Hawaii, Dutch Harbor, Alaska, and Ceylon. No mention was made of the Australian submarine base.

This estimate of the enemy’s intentions and capabilities did not hold out much promise for the future. And when the Japanese considered their own resources, the picture became even darker. Their great weaknesses, they recognized, were in aircraft and in shipping. Without an adequate supply of both, Japan could not hope to halt the Allied drive, much less open an offensive of its own. The total number of aircraft that would be required by the Army and Navy during 1944, it was estimated, was 55,000, an impossible figure in view of the fact that total Japanese aircraft production in August 1943 was only 1,360 and in September 1,470. And even if the Japanese could produce as many as 55,000 planes, the effort would so strain the economy of the nation that it would be impossible to try to match American and British naval forces, build up ground strength to a level adequate to meet a possible threat from the Soviet Union, or initiate large-scale offensive operations in China. But these goals the Japanese were apparently willing to sacrifice for air power, the Navy planners insisting only that they had to have special attack and antisubmarine craft.

The shipping problem was no less serious than the shortage of aircraft. In a period of less than two years 445 vessels totaling 1,754,000 tons had been sunk and another 414 (2,109,800 tons) dam-

Table 9—Japanese shipping losses, 7 December 1941–20 September 1943°

| Caused By | Sunk | Damaged | Total | |||

| No. of Vessels | Tonnage (in thousands of tons) | No. of Vessels | Tonnage (in thousands of tons) | No. of Vessels | Tonnage (in thousands of tons) | |

| Totals | 445 | 1,757.4 | 414 | 2,109.8 | 859 | 3,867.2 |

| Submarines | 290 | 1,233.0 | 146 | 910.7 | 436 | 2,143.7 |

| Aircraft | 75 | 303.7 | 97 | 536.2 | 172 | 839.9 |

| Mines | 29 | 85.7 | 22 | 106.2 | 51 | 191.9 |

| Sea Disasters | 51 | 135.0 | 149 | 556.7 | 200 | 691.7 |

* Only ships with a gross tonnage of more than 500 are included.

Source: Hattori, The Greater East Asia War, III, 16.

aged. By far the largest toll, over two million tons, had been taken by Allied submarines; the action of Allied aircraft accounted for another 840,000 tons. (Table 9) And there was every reason to expect that the number of sinkings would increase sharply unless drastic measures were taken. At the present rate, the Japanese estimated, shipping losses from Allied submarines alone would total 100,000 tons a month by the end of the year.4 Only a major effort to increase greatly the number of escort vessels and antisubmarine aircraft could avert this disaster.

The production of aircraft and ships would take time. The problem facing the Japanese, therefore, was to gain the maximum time with the minimum loss, to trade space for time. The solution proposed by the planners at Imperial General Headquarters was embodied in the “New Operational Policy.” Convinced that the line eastern New Guinea–Northern Solomons–Marshall and Gilbert Islands could not be held, and was, indeed, on the verge of collapse, they recommended that a new line encompassing the “absolute national defense sphere”5 be established. Beyond this line there would be no retreat; along it would be built impregnable defenses. And while the Allies fought their way to this line, the Japanese could repair their losses in aircraft and shipping in preparation for a great counter-offensive.

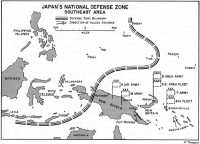

The selection of a new defense line was based on the most careful calculation of Japan’s resources and Allied capabilities. Extending from the Kuril Islands southward through the Bonins, Marianas, and Carolines, thence south and west to western New Guinea, the Sunda Islands in the Netherlands Indies, and finally to Burma, this line comprised the minimum area considered essential for the attainment of Japan’s war aims. Possession of this area would give Japan the advantage of interior lines and the raw materials and food needed to meet military and civilian requirements. Since it corresponded also to the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, its security was an essential prerequisite to the political and economic control of the nations included

within the Japanese orbit. Any reduction of the area, or the acquisition by the Allies of bases from which to strike important political and industrial targets within it, was bound to affect seriously Japan’s political position and capacity to wage war.

Based on these considerations, the Japanese planners formulated a strategy whose primary objective was the defense of this vital area. First, in recognition of Japan’s inability to hold the existing line in the Southeast Area, the Japanese would take a long backward step and establish a more restricted perimeter extending from the Carolines to western New Guinea. Next, they would erect an “undefeatable strategic position” along this new line, establishing advance bases in front of it to keep Allied air power at a safe distance and safeguard the line of communications. Finally, they would build up Japanese power within the absolute defense area, with special emphasis on air power. By utilizing the geographic advantages of this new line and of interior lines of communications, the Japanese hoped they would be able to repulse any large-scale enemy offensive and ultimately to launch a counteroffensive of their own. (Map 9)

In concrete terms, as enunciated by the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters on 15 September 1943, this new strategy or “operational policy” would require the following:–

1. Close cooperation with the Navy.

2. Strong delaying action in the Southeast Area. Allied forces advancing in this critical region were to be resisted fiercely, and delayed as long as possible. The time thus gained was to be used to build up the defenses along the new line from the Banda Sea to the Caroline Islands and to marshal the forces for a counteroffensive.

3. All-out defense in the Southwest Area, the Japanese designation for the region extending from the Banda Sea to Burma. This area was part of the absolute national defense sphere; therefore the complete destruction of any enemy forces seeking to invade the region was absolutely essential to Japan’s successful prosecution of the war.

4. Preservation of the status quo in China, while increasing pressure against the enemy to destroy his will to fight. In North China, preparations would be made to meet the contingency of Soviet-American cooperation, but no step would be taken that might bring the Soviet Union into the war.

5. Strengthening the defenses of the home islands, the oil regions of the East Indies and the shipping lanes to Japan. These measures were vital to the conduct of the war and the execution of the new operational policy.

6. Raiding operations deep behind enemy lines in every area.

7. All possible measures of operations that would bring into full play the combined fighting power of the air, ground, and naval forces; in short, any operation that promised success.6

The Decision Is Made

Japan’s military leaders had proposed a new operational policy, a strategy designed to trade space for time; her political leaders now put forward a foreign policy to match. First among the objectives of the Foreign Ministry was the preservation of peace with the Soviet Union. This was to be achieved in three ways: first, by maintaining Japanese military strength and, if possible, by winning military victories over the United States and Great Britain; second, by adopting positive measures designed to improve friendly relations with the USSR; and third, by exercising restraint but resolution

Map 9: Japan’s National Defense Zone, Southeast Area

in dealing with the Soviet Union over controversial matters.7

The possibility that Germany and the Soviet Union might suddenly conclude a separate peace treaty was a contingency the Japanese could not ignore. Such a move, they recognized, would undoubtedly have a profound effect on Japan’s situation. Therefore, to ensure that the effect was favorable and the dangers minimized, the Japanese agreed that they must follow the situation closely and be prepared at the first sign of peace to move in with an offer of mediation. The timing of this offer was considered of the utmost importance by the experts in Japan’s Foreign Ministry. It should coincide, they said, with military success in the field, either by Germany or Japan, or with the successful completion of negotiations for a settlement of the China incident.

Cooperation with Germany was a political rather than a military objective for the Japanese. Thus, the measures proposed were limited to exchange of views and information, visits of dignitaries, and joint declarations of common aims and objectives in the war against the Allies. What the Japanese wanted

most from Germany were war materials and technical information. For these they were willing to exert their “utmost effort” to promote cooperation and even to hold out the possibility of German participation in the economic development of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

To cope with the political offensive being waged by the Anglo-American Allies in East Asia, the Japanese decided they must take stronger measures to convince the peoples of Asia that their destiny lay with Japan. The most effective argument, of course, was military victory, but the Japanese could not rely on that. They proposed therefore to secure the “voluntary” cooperation of the Asiatic people by fair and just treatment of the occupied nations and by propaganda emphasizing the evils of colonialism. The weakness in their argument, the Japanese realized, was the Japanese Army in China. Resistance by the Chungking government would by example encourage opposition to the Japanese everywhere in Asia. A primary aim of Japanese foreign policy, therefore, must be the settlement of the China incident.

The political program proposed by the Foreign Ministry was reviewed and accepted without dispute on 25 September at a meeting of the Liaison Conference, which, it will be recalled, consisted of the service chiefs and the Cabinet and served as a link between Imperial General Headquarters and the government. At this same meeting of 25 September the assembled political and military chiefs approved the strategic policy presented by Imperial General Headquarters. With agreement on the basic problems of political and military strategy, the leaders of the Japanese Government were ready to go before the Emperor. His assent would seal the decisions already made and give them the powerful sanction of imperial decree.8

The Imperial Conference that fixed the course Japan would attempt to follow during the next year and a half opened at to o’clock on the morning of 30 September 1943. Assembled for this meeting with the Emperor, the “August Mind” of Japan, were the highest officials of the government—the Premier and War Minister, Hideki Tojo; the Navy, Foreign Affairs, Finance, Agriculture, and Commerce Ministers; the Chiefs and Deputy Chiefs of the Army and Navy General Staffs; the President of the Privy Council, Director of the Cabinet Planning Board, and Minister for Greater East Asia Affairs; and the heads of various government departments. In accordance with custom Premier Tojo presided.

For most if not all those present at the Imperial Conference, the proceedings offered nothing new. The purpose of the conference was to secure the Emperor’s sanction for decisions already made, not to present various proposals and policies for his decision. The Japanese constitutional system did not assign the role of policy-maker to the Emperor. As the personification of national unity and the supreme symbol of Japanese life and thought, the Emperor stood above party, and faction. Ancient tradition limited his action to approval of the decisions of his ministers; precedent dictated silence. But by his presence alone, he set upon these decisions a finality and authority that could be achieved in no

other way. Thereafter, there was no turning back; only another Imperial Conference could alter or reverse the course approved by the Emperor. This was the significance of the meeting of 30 September; it witnessed, in solemn and historic fashion, a major shift in Japanese policy and strategy for the conduct of the war.

General Tojo opened the conference with a reading of the political estimate adopted at the Liaison Conference of 25 September. The Emperor listened gravely; there was no discussion. Next, the secretary read the proposed “General Outline of the War Direction Policy.” Each of the more important officials then stood up in turn, with Tojo leading off, to elaborate on the program and explain to Emperor Hirohito how his department expected to achieve the goals set out in the new program. The President of the Privy Council asked several penetrating questions and when these were answered to his satisfaction Tojo closed the conference at 3:30 p.m., with a brief statement announcing that since there was no objection, the new policy was adopted unanimously. There is no record that the Emperor spoke once during the meeting.

The New Strategy in Action

Once the stamp of Imperial approval had been secured, the Army and Navy lost no time putting into effect the new strategy. In accordance with established practice, the basic strategy was embodied in an “Army-Navy Central Agreement,” the Japanese equivalent of a U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff directive. With this central agreement outlining the major objectives of the new policy, Imperial

General Headquarters sent to the commanders in the field specific instructions on the course they were to follow in attaining these objectives. For the army commanders these instructions came from the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters in the form of a GHQ numbered order. The Navy Section issued its own order to the fleet commanders, a procedure that led to different interpretations of the central agreement and left to the separate commanders responsibility for making arrangements for coordination and concerted action of joint forces.9

The central agreement promulgated after the Imperial Conference differed in no essential respect from the policy formulated by Imperial General Headquarters on 15 September. In general terms it called for the “utmost endeavor” by the Army and Navy, acting in close cooperation, to delay the enemy drive in the strategic Southeast and Central Pacific Areas as long as possible while preparing for a large-scale counteroffensive that would end the Allied threat from the south and east. Preparations for this counteroffensive would include airfield and base development, concentration of forces in the threatened area, stockpiling of munitions and critical supplies, and active operations to cut the Allied line of communications and keep the Allies off balance. Six months were to be allowed for these preparations on the assumption that the main Allied drive would begin in the spring or summer of 1944.

Admiral Kusaka

The task of putting this plan into effect in the Southeast Area, which was outside the absolute national defense line, fell on the commander of the 8th Area Army, General Imamura, and his naval colleague, Admiral Kusaka, commander of the Southeast Area Fleet. The first was to make every effort to hold the Bismarck Archipelago and Bougainville, in anticipation of an Allied drive on Rabaul. At the same time he was to support the forces on the New Guinea side of the Bismarck barrier to fend off the Allied offensive as long as possible. In this he was to have the help of the Southeast Area Fleet, whose air and naval forces were to attack Allied convoys, in cooperation with Army aircraft, and keep open the supply lines to Japanese forces in New Guinea and the Solomons.10

General Imamura’s plans were based on the estimate that the Allied offensive in New Guinea and the Solomons was directed at the capture of Rabaul. The attack, he thought, would come in February or March 1944, after the Allies had gained control of Bougainville, and of Dampier Strait between New Guinea and New Britain. Imamura considered the possibility of an Allied encirclement of Rabaul by the seizure of the Admiralties and New Ireland, but finally decided that MacArthur would try to take Rabaul by direct assault, as, indeed, MacArthur wished to do. Enemy ground strength Imamura estimated at 19 to 22 divisions, four of which he placed in the Solomons and three in New Guinea; the remainder, though not in the combat area, he considered available for operations should the need arise. Of the 3,000 planes credited to MacArthur and Halsey, the Japanese commander thought only about half were located in the forward areas—700 in New Guinea and 600 in the Solomons.

On the basis of this estimate and his new mission, General Imamura saw his task as one of delaying the enemy drive. His main effort clearly would have to be directed toward holding Bougainville and the Dampier Strait area (Cape Gloucester in New Britain and the Huon Peninsula in New Guinea) as long as possible. This concept was much like the one he was already following, and Imamura’s new plan differed from the old only in the emphasis it placed on the critical areas.

To carry out this plan, General Imamura had 2 armies, the 17th and 18th, 2 independent divisions, some nondivisional units, support and service troops, and an air army. The 28th Army, with headquarters at Madang, was responsible for the defense of eastern New Guinea and had assigned to it 3 divisions, the 20th, 41st, and 51st. The 17th Army in the Solomons had only 1 division, the 6th, located on Bougainville, but a nondivisional strength consisting of the 4th South Seas Garrison Unit, plus 1 artillery and 4 infantry battalions. To this 17th Army strength must be added the naval ground units in the central and northern Solomons, which constituted a fairly large body of well-trained combat troops.

Troops in the Bismarck Archipelago, on New Britain, New Ireland and the Admiralties, were under the direct control of 8th Area Army. The largest strength was concentrated on New Britain at whose eastern end stood Rabaul, the last stronghold of the Southeast Area. Guarding this critical area as well as western New Ireland was the Rabaul Defense Unit, composed of the 38th Division and attached elements. The western end of New Britain, facing Dampier Strait, was held by the 65th Brigade, while the central portion was reserved for the 17th Division, scheduled to arrive shortly from Shanghai. In the Admiralties, with its strength concentrated on Los Negros, was the 51st Transport Regiment.

The Army air strength of the Southeast Area, consisting of the 6th and 7th Air Divisions, was organized into the 4th Air Army. Except for one air brigade assigned to the support of the 19th Army in the Banda Sea area, this air force operated chiefly in eastern New Guinea and western New Britain, in defense of Dampier Strait. Air support for the Bismarck Archipelago and the northern Solomons was furnished largely by shore-based naval aircraft of the 11th Air Fleet based at Rabaul and in southern Bougainville.

On 7 October 1943, General Imamura issued the revised plan for operations in the Southeast Area. The 18th Army in New Guinea was to occupy and defend the coastal region along Dampier Strait, particularly Finschhafen, and the Ramu Valley in the interior. To the 17th Army in the Solomons, Imamura assigned the task of holding Bougainville, and to the 65th Brigade on New Britain the eastern shore of Dampier Strait. The 4th Air Army was to provide support as required, with the primary mission of destroying any enemy forces attempting to land in the Dampier Strait region. If this proved impossible and if the enemy established a foothold on Bougainville or in the critical Dampier Strait area, then all Japanese troops under his command, ruled General Imamura, would “trade position for time, to the end that the enemy offensive will be crushed as far forward as possible under the accumulation of losses.”11

The main burden of holding the Central Pacific rested on Admiral Mineichi Koga, Combined Fleet commander at Truk. Directed to push preparations for holding the Carolines and the Marianas, both of which were included in the absolute national defense sphere, Admiral Koga had to rely largely on

Army reinforcements to fortify the bases in his area. All together, Imperial General Headquarters allotted for this purpose approximately forty infantry battalions, as well as tanks, artillery and other support.12 (Table 10) But many of these forces were lost at sea as a result of Allied submarine attacks and never reached their destination. Those that did, Koga used to reinforce the Gilberts and Marshalls, thereby weakening his defenses in the Marianas and Carolines.

From the Army point of view, the assignment of troops intended for the Marianas and the Carolines to outlying positions in the Marshalls was a serious error. But even more serious, many Army officers believed, was the fact that the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters, by emphasizing the naval mission to meet and engage the enemy fleet, failed to impress on Admiral Koga the necessity for husbanding his strength along the vital national defense line. Koga, the Army held, had not been given proper guidance, with the result that the new operational policy was never properly carried out in the Central Pacific.

Among the orders issued by Imperial General Headquarters on 30 September were those to the commander of the Southern Army, Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, directing him to expedite preparations for the expected counteroffensive. Originally, the Southern Army headquarters had controlled Japanese operations in the entire Southern Area from Malaya to Guadalcanal, but its jurisdiction had been gradually restricted as new commands were formed in the Solomons and New Guinea to meet the Allied offensive in 1942 and 1943. It was time, Imperial General Headquarters decided in October 1943, to carve out another piece from Terauchi’s domain. This piece, which extended from the 8th Area Army boundary at longitude 140° east westward to Makassar Strait and from latitude 5° north southward to Australia, included most of Dutch New Guinea, Halmahera, the Celebes, Timor, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. In the view of Imperial General Headquarters, this area had now assumed a critical importance as the pivotal point for the projected counteroffensive. More important, perhaps, was the fact that the area included the sea approaches to the Celebes and South China Seas—objectives of the Allied drive across the Central Pacific—and covered the route to the Philippines favored by General MacArthur.13

Prompted by these considerations, the planners in Tokyo took steps to reorganize the defenses of this area. In a series of orders dated 29 October, they established a separate command under the direct control of Imperial General Headquarters, organized an area army headquarters to direct operations, and assigned to it an additional army and three more divisions. (Chart 16) The headquarters designated for the area was General Korechika Anami’s 2nd Area Army, then in Manchuria. Under it would be the

Table 10: Japanese Army Reinforcements, Central Pacific, September 1943–January 1944

| Island | Unit | Date of Arrival |

| Carolines: | ||

| Truk | 52nd Division: Division Headquarters, 19th Infantry (less 2nd Battalion), 3rd Battalion, 150th Infantry, (Remainder of division left Japan in January 1944) | December 1943–January 1944 |

| Mortlock | 4th Nanyo Detachment | January 1944 |

| Ponape | 3rd Nanyo Detachment, 2nd Battalion, tank and machine cannon companies of KO Detachment | November 1943, January 1944 |

| Kusaie | 2nd Nanyo Detachment, KO Detachment (less elements) | November 1943, January 1944 |

| Marshalls: | ||

| Eniwetok | 1st Amphibious Brigade (less 2nd Battalion and Engineer Units) | September 1943–January 1944 |

| Jaluit | 2nd Infantry Battalion (less 2 companies, Nanyo Detachment) | September 1943 |

| Mille | 1st Nanyo Detachment (less 2nd Battalion), 3rd Infantry Battalion, one Mountain Artillery Battalion (less one company), one engineer company (less one platoon) of KO Detachment | September–November 1943 |

| Maloelap | One infantry company, 1st Amphibious Brigade, One infantry company, 1st Nanyo Detachment | September 1943—January 1944 |

| Wotje | One infantry company, 1st Amphibious Brigade, One infantry company, 1st Nanyo Detachment, One machine gun company | September 1943—January 1944 |

| Kwajalein | 1st Infantry Battalion (less 2 companies), 1st Amphibious Brigade, Engineer Units | January 1944 |

Source: Hattori, Greater East Asia War III, 52.

19th Army, already in the area, and the 2nd Army, which, like the 2nd Area Army, was to be transferred from Manchuria. To the former was assigned an additional division, the 46th from Japan; to the latter the 3rd and 36th Divisions, then stationed in China. With the arrival of these units, and others, General Anami would have under his control two armies and a total of five battle-tested and fresh divisions, one of which, the 36th, was organized and equipped for amphibious operations.14 Already in the area, was the 7th Air Division.

The wholesale shifting of forces and supplies required by these orders placed a serious strain on the already overburdened Japanese shipping facilities. It was almost a month before General Anami established a provisional headquarters at Davao in the southern Philippines and only on 1 December did he assume operational control. At the time, 2nd Army had no combat units at all and the 19th Army, for which reinforcements would not arrive until February 1944, had only two divisions whose elements were scattered among the islands west of New Guinea. Even if shipping had been available, it would have been impossible to concentrate forces for a sudden emergency. The arrival of the 36th Division on 25 December and its subsequent assignment to the Geelvink Bay area made it possible at least to provide protection for what was considered the most important strategic position in the 2nd Army zone. But this still left the northeast New Guinea coast from Wewak to Sarmi virtually undefended.

If General Anami had reason to complain about the shortage of ground forces, he had even more reason to fear for his air defenses. His only air unit was the 7th Air Division, then recuperating at Ambon from the heavy blows it had suffered in eastern New Guinea during the summer and early fall. When Anami assumed control of the division it had only about fifty planes operational, and virtually all these were involved in local defense and escort missions in the 19th Army area. There were none to spare for the 2nd Army, and, in view of the critical shortage of planes everywhere, little prospect of getting more.

Nor could General Anami expect much help from his naval colleague, commander of the newly formed 4th Expeditionary Fleet. This force was a fleet only in name, consisting largely of several naval special base units and some special landing troops, scattered throughout the area. There was a navy air unit at Kendari in the Celebes, but it, too, had only about fifty planes and most of its experienced pilots had been moved to Rabaul. The real strength of the Japanese Navy in this region lay in the Southwest Area Fleet, with headquarters at Surabaya. In the event of a naval threat from the south by way of the Indian Ocean, it was this organization rather than the 4th Expeditionary Fleet that would go into action. Any threat from the east would presumably be met by the Combined Fleet at Truk.

Even without the strong protests from the field, the high command in Tokyo could not have failed to see how weak were the defenses of western New Guinea and the Central Pacific. There was no shortage of troops or munitions; Anami was promised reinforcements that would

Chart 16: Organization of Japanese Forces in Pacific and Southeast Asia, November 1943

have given 2nd Area Army a total strength of 320,000 men. Nor could Admiral Koga complain that Imperial General Headquarters refused to send him troops when he asked for them. The trouble was shipping. At the Imperial Conference of 30 September, the Army and Navy had asked for additional ships to move the troops and supplies needed to carry out the new operational policy.15 They had received only 250,000 additional tons, barely enough as it turned out to meet the losses from enemy action. The rest had been allocated to civilian agencies for the war production program. Under these circumstances, the monthly requirements of 2nd Area Army for 450,000 gross tons of large and medium-sized transports and 150,000 gross tons of smaller ships for a period of four months proved too heavy a drain on the resources of Imperial General Headquarters.

The shortage of shipping was not an absolute shortage; 2nd Area Army’s requirements might still have been met had it not been for the competing demands of other theaters and the unexpectedly heavy losses from Allied submarines. From November on, the Central Pacific was regarded as the more critical area and enjoyed a higher priority than the Southeast Area. But the ship losses there proved most serious. In December, the total was 300,000 gross tons, and during the first month of the new year, the figure rose to 460,000 (including ships heavily damaged)—the highest yet recorded since the start of the war. It was largely for this reason that shipments to the zd Area Army were virtually discontinued during February and March 1944, even though an additional 300,000 tons of shipping was allocated to the armed forces in that period.

The Japanese were having trouble also meeting the goals set for aircraft production. By the end of the year it was evident these ambitious goals, though successively reduced, would not be met, partly because Japanese industry was not equal to the task and partly because of the shortage of shipping and shipping losses. Thus, instead of the 4,000 planes that should have come off the assembly lines each month, Japanese military forces received during the first quarter of 1944 only about half that number.

Essential also to the success of the new strategy adopted at the end of September was the airfield construction program designed to furnish bases from which to meet the Allied threat and support the planned counteroffensive in the spring of 1944. In General Anami’s area alone, 100 new airfields, echeloned in depth and mutually supporting, were to be built. The task was a gigantic one and impossible of execution even though combat units were put to work as labor troops. The shortages of critical materials, and lack of mechanized equipment, labor, and engineering skill, combined with the difficulties of transportation brought the construction program to a grinding halt almost before it had got started. As a result, few of the projected air bases were ever completed.

In the final analysis, the success or failure of the plans so hopefully made in September depended on the ability of the Japanese forces in New Guinea,

the Solomons, and the Central Pacific to halt the Allied drive, or at least hold long enough to permit the assembly of troops and supplies needed for an effective defense, and, ultimately, a counteroffensive. But even while these plans were being drawn and the forces required moved into the critical areas, General MacArthur, Admiral Nimitz, and Admiral Halsey had begun to push against the outposts of the absolute national defense line.