Chapter 3: The Thwarted Landing

To the great relief of the weak and dispirited Port Moresby garrison, the occupation of Lae and Salamaua was not immediately followed by a move on Port Moresby. Fortunately for its defenders, the Japanese left the Port Moresby operation temporarily in abeyance and sent their carrier striking force into the Indian Ocean instead to raid the British. This was to prove a fatal mistake. For when the Japanese finally undertook to land troops at Port Moresby, it was to find that carriers of the U.S. Pacific Fleet stood in their way, and they had sent too little and moved too late.

Frustration at Jomard Passage

Carrier Division 5 Leaves for Truk

The Port Moresby landing had to wait because the Japanese had decided to commit Admiral Nagumo’s entire striking force to the raid in the Indian Ocean. They made this decision because they were after a more glittering prize—the British Eastern Fleet. They hoped that Nagumo would be able to surprise and destroy the fleet, which was then based at Ceylon, in the same way that only three months before he had surprised most of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. For such a strike, he would require all of his available carriers. Only when the raid was over would carrier strength be detached for the Port Moresby mission.

When operations in the Indian Ocean were over, the large carrier Kaga would go on to Truk to support the Port Moresby landing. The rest of Admiral Nagumo’s force, which had been months at sea, would be sent home for refitting. On hearing of the U.S. carrier strikes at Lae and Salamaua on 10 March, the Japanese began to have doubts that one large carrier would be enough and decided to send two. Admiral Nagumo, with an eye to his training needs after the Indian Ocean operation, sent the Kaga back to Japan and chose the two large carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku (Carrier Division 5), then undergoing minor repair in Japan, for the Port Moresby operation.

On 24 March the Shokaku and the Zuikaku reached Kendari in the Celebes, where the striking force was then based. Two days later Nagumo left Kendari for the Indian Ocean with five fast carriers under his command. He raided Colombo and Trincomalee, main British bases in Ceylon, on 5 and 9 April, but without catching the British Eastern Fleet at anchor as he had hoped. He did run into portions of the fleet at sea and, while other Japanese naval units operating in the area sank more than a score of Allied merchantmen, dealt it a staggering blow by sinking in quick succession an aircraft carrier, two heavy cruisers, a destroyer, a corvette, and a fleet auxiliary.

By mid-April, the raid was over. The

striking force left the Indian Ocean and, after a final rendezvous off Formosa, split into two. The main body, under Admiral Nagumo, made for Japan, and Carrier Division 5 and its escort, for Truk. The date was 20 April.1

The Orders of 29 April

At Rabaul, meanwhile, the South Seas Detachment was on the alert, waiting for orders to land at Port Moresby. There had been a Japanese landing at Lorengau in the Admiralties on 6 April by a small naval force from Truk. A larger force from the Netherlands Indies had begun a series of landings along the coast of Netherlands New Guinea earlier the same week.2 But no orders had been received to move on Port Moresby. General Horii, who had expected to receive them immediately after Lae and Salamaua were taken, inquired of Imperial General Headquarters on 15 April why there had been no action in the matter. Tokyo’s reply was received three days later. In addition to ordering Horii to begin immediate preparations for the Port Moresby landing, it alerted him to the fact that he would soon receive orders for the seizure of New Caledonia. This operation and that against Fiji and Samoa would follow the capture of Port Moresby.3

On 28 April, ten days later, at the instance of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet, Imperial General Headquarters, sanctioned operations against Midway and the Aleutians. It was agreed that these operations would follow the Port Moresby landing, and would be followed in turn by the scheduled operations against New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa.4

The decision of 28 April did not affect preparations for the Port Moresby landing. By this time they were so far advanced that General Horii was able to issue his first orders for the operation the next day, 29 April—a particularly auspicious date, Horii felt, since it was the emperor’s birthday. The orders provided that the Detachment would leave Rabaul on 4 May, under escort of the 4th Fleet, and at dawn on 10 May would make a landing at Port Moresby with the support of units of the Kure 3rd Special Naval Landing Force. The main body of the Detachment was to land on a beach seven and a half miles northwest of Port Moresby, and the 1st Battalion, 144th Infantry, and the naval landing parties, were to land on another beach to the southeast of the town. The two forces would launch a converging attack and in short

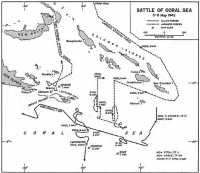

Map 1: Battle of Coral Sea, 5–8 May 1942

order take all their objectives—the harbor, the town, and Kila Kila airdrome immediately outside the town.5

Moving Out for the Landing

The 4th Fleet had made careful preparations for the landing, and Admiral Inouye himself came to Rabaul from Truk to take personal charge of the operation. The occupation force, seven destroyers, five transports, and several seaplane tenders, was to have the support of the small carrier Shoho, which in turn would be screened by a force of four heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a squadron of submarines. Carrier Division 5, which had arrived at Truk toward the end of the month with its screen Cruiser Division 5—three heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, six destroyers, and an oiler—was to

The Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942. The Japanese fast aircraft carrier, Shokaku, is heavily damaged by Navy torpedo planes

serve as the attack force. It was to destroy Allied sea and air units seeking to attack the occupation force, cover the landings, and raid Townsville in order to immobilize Allied attempts to interfere with the landing from Australia.6

Because the invasion plan also called for flying boats to operate out of Tulagi in support of the operation, the Japanese at once sent a force to that point to prepare it for its appointed role. On 2 May, the small RAAF detachment at Tulagi and other Australian forces in its immediate vicinity learned of the Japanese approach. They set demolitions and made for Vila in the New Hebrides, where there was part of an Australian Independent Company, reaching it safely a few days later. The next day, 3 May, the Japanese landed a small force at Tulagi and began to convert it into a seaplane base.7

The South Seas Detachment began to embark at Rabaul for Port Moresby on 2 May. On 4 May, the scheduled date of departure, the transports left the harbor. The convoy met the Shoho force at a rendezvous point off Buin, Bougainville. Shortly thereafter, the Shokaku and Zuikaku and their escort rounded San Cristobal Island at the southern

The Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942. Aircraft carrier USS Lexington, seriously damaged by the Japanese, is abandoned

tip of the Solomons and took up a supporting position to the eastward of the invasion convoy. By 7 May, the Shoho force was assembling in the area between Deboyne and Misima Island in the Louisiade Archipelago preparatory to passing through Jomard Passage, a channel which would bring them safely through the reefs of the Archipelago into Port Moresby’s home waters. The transports, at Admiral Inouye’s orders, were standing on the western side of Woodlark Island. The Shokaku and Zuikaku lay in open water to the southeast.8 (Map 1)

The Battle of the Coral Sea

This time the Allies were prepared. The concentration of naval forces in the Mandates and at Rabaul, and a sudden increase of air strength in the Lae-Salamaua-New Britain-Solomons area, had given warning that the long-expected thrust at Port Moresby was at hand. To meet the danger, the Southwest Pacific Area made the best preparations it could. The Allied Air Forces, under General Brett, by this time based mainly on the newly built airfields in the Townsville-Cloncurry area, intensified their reconnaissance of New Britain, Bougainville, and the Louisiade Archipelago. Allied ground forces in northeast Australia and at Port Moresby were put on the alert. Three cruisers of the Allied Naval Forces,

the Australia, the Chicago, and the Hobart, under Rear Adm. J. G. Crace, RN, were sent to the Coral Sea to reinforce elements of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, which were gathering there preparatory to closing with the enemy.9

The Pacific Fleet, anticipating a Japanese thrust against Port Moresby, had made suitable provision for countering it. After the strikes at Lae-Salamaua on 10 March, the Yorktown had remained in the Coral Sea. On 1 May, it was rejoined there by the Lexington, and the combined force—two carriers, seven heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, thirteen destroyers, two oilers, and a seaplane tender—came under command of Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher the same day.

Late on 3 May Admiral Fletcher learned of the Japanese landing at Tulagi. Fletcher, who was on the Yorktown and out of touch with the Lexington, struck at Tulagi early on the 4th. Results were disappointing, for there were no important targets in the harbor. Early the next morning, the Yorktown rejoined the Lexington at a rendezvous point a few hundred miles south of Rennell Island, and the combined force moved out to the northwest, its search planes looking for the enemy.

Early on 6 May, after a great deal of search by carrier-based planes had failed to locate the enemy, Allied Air Force B-17’s, reported a large force west of Misima Island moving in the direction of Jomard Passage. Admiral Fletcher, who was then fueling at a point roughly 700 miles southeast of Rabaul, at once ordered the tanker Neosho and its escort, the destroyer Sims, to move south to a fueling rendezvous point believed to be out of the enemy’s way. The rest of the fleet moved northwestward in the direction of the Louisiade Archipelago. The next morning, as the Louisiades came within range, a task force of cruisers and destroyers was given the mission of blocking the southern end of Jomard Passage, and the main force prepared to engage the enemy.10

Ironically, the rendezvous point of the fueling group, chosen because it was believed to be out of harm’s way, brought the Neosho and the Sims within easy range of the positions the Shokaku and Zuikaku had taken in order to cover the movement of the occupation force through Jomard Passage. Early on the 7th, a Japanese search plane sighted the tanker and its escort and reported them to the Japanese carrier commander, Rear Adm. Tadaichi Hara, as a carrier and a cruiser. Hara at once ordered out all his planes for the kill. The Japanese carrier pilots made short work of the two ships. The Sims sank at once, and the Neosho was left in a sinking condition.

Just before noon the same day, search planes from the Yorktown discovered the Shoho and a part of its screen off Misima Island. Planes from both the Lexington and the Yorktown immediately closed in. The carrier and a light cruiser, which was escorting it, were hit, and they sank immediately.

There the day’s action ended. Despite feverish search activity on both sides, neither side had thus far succeeded in definitely locating the main body of the other.

The opposing carrier forces finally located each other in the early morning of 8 May and their planes joined battle at once. On the Allied side both the Lexington and the Yorktown were damaged, the Lexington seriously. On the Japanese side the Shokaku was heavily damaged, though the damage was by no means fatal; and the Zuikaku, though undamaged, lost most of its planes. With the Shoho gone and the Shokaku in no condition to continue the fight, Admiral Inouye, whose oil was running low, broke off the engagement and withdrew to the north. Admiral Fletcher, who had the problem on his hands of saving the Lexington, its planes, and its crew, withdrew in turn to the south. The Shokaku got back safely to Truk, and the transports carrying the South Seas Detachment reached Rabaul, but the Lexington developed uncontrollable gasoline fires and had to be abandoned and sunk.

The battle was over. The Allies had suffered heavier losses than the Japanese, but the fact that the latter had been turned back from Port Moresby left the victory, strategically at least, with the Pacific Fleet.11

On 9 May, Imperial General Headquarters advised General Horii that because of the action at the Coral Sea the invasion of Port Moresby would have to be temporarily suspended. He was assured, however, that he would not have long to wait for a resumption, for it had been definitely decided that the operation would be carried out sometime in July.12

The landing had miscarried completely. Thanks to the U.S. Pacific Fleet, the Southwest Pacific Area now had a respite in which to continue with the barely begun task of reinforcing Australia’s approaches.

Securing the Approaches

GHQ Authorizes BOSTON

Believing that the Japanese would strike at Port Moresby again with at least a division of troops and carrier and land-based aircraft “any time after June 10,”13 General MacArthur and his staff at once set themselves to secure the area to the maximum extent that the available means would allow.

The means were growing. On 14 May the 32nd U.S. Infantry Division, under command of Maj. Gen. Edwin F. Harding, arrived in Australia with the rest of the 41st Division. A day later, the 14th Australian Infantry Brigade Group, 3,400 strong, began moving to Port Moresby with 700 attached Australian antiaircraft troops.14

One of the lessons of the Coral Sea had been that to cover Port Moresby’s eastern approaches effectively the Air Force would have to have a base at or near the southeastern tip of New Guinea. A base in the low-lying regions in that area would do more than provide protection for Port Moresby’s uncovered flank. It would give the Air Force a new staging point for attacks on Japanese bases to the north and northwest and one, furthermore, that was not subject to the turbulences and other operational hazards that beset flight over the Owen Stanleys. Ultimately it would provide a point of departure for an advance along the southeast coast.15

These considerations were not lost on General MacArthur. In a letter to General Blamey on 14 May, he wrote that a careful study of weather and operating conditions along the southeast coast of Papua had resulted in a decision to establish new airdromes there for use against Lae, Salamaua, and Rabaul. Noting that suitable sites appeared to be available in the coastal strip between Abau and Samarai near the southeast tip of Papua, he asked Blamey if he had the necessary ground troops and antiaircraft units to protect these bases. When General Blamey replied that he had the troops, General MacArthur authorized the construction of a landing strip 50 feet by 1,500 feet at BOSTON, the code name for Abau–Mullins Harbor area, a wild and largely unexplored coastal area requiring an immense amount of development. The new field (so the orders read) was to be built “in a location susceptible of improvement later on to a heavy bombardment airdrome.”16

The Plan of Reinforcement

On 20 May, the same day that he authorized the construction of an airfield at BOSTON, General MacArthur issued a comprehensive plan to his commanders for the “reinforcement of combat means” in northeast Australia and New Guinea. Under terms of this plan, the Air Force would bring its existing pursuit squadrons at Port Moresby up to full strength, and U.S. antiaircraft troops at Brisbane would be transferred to Townsville, Horn Island, and Mareeba, Cooktown, and Coen, the bases in the Cape York Peninsula. These bases, Port Moresby, and the new base at BOSTON were to be fully stocked with aviation supplies, bombs, and ammunition, so that when an emergency arose the Air Force would be able to use them for the interdiction of enemy “movements through the Louisiades and along the southeast coast of New Guinea.” The construction or improvement of the airfields in northeast Australia and in New Guinea was to be accelerated, and the transport to them of reinforcements and supplies was to be arranged by USAFIA, in consultation with Allied Land Forces.17

When completed, the new air bases in northeast Australia and the York Peninsula would advance the forward bomber line by as much as 500 miles. They would bring the bombers as close to Port Moresby as it was physically possible to get them without

actually basing them there, and would place them in position for active defensive and offensive action. The new fields and dispersal areas at Port Moresby would not only facilitate the progress of the bombers as they staged through it in their tramontane attacks upon the Japanese bases in North East New Guinea and New Britain but would also permit more fighters and light bombers to be based there. The field at BOSTON, in addition to providing its offensive possibilities, would help to thwart any further Japanese attempt to take Port Moresby from the sea.

On 24 May Allied Land Forces picked the garrison for BOSTON and assigned it its mission. Being apparently in some doubt that BOSTON could be held, Land Force Headquarters instructed the troops chosen that they would be responsible for ground defense of the area against only minor attacks. If the enemy launched a major attack against them, they were to withdraw, making sure before they did so that they had destroyed “all weapons, supplies, and material of value to the enemy.”18

Milne Bay

The field at BOSTON was never built. When an aerial reconnaissance of the eastern tip of New Guinea was ordered on 22 May,19 it was discovered that there were better sites in the Milne Bay area. On 8 June, a twelve-man party, three Americans and nine Australians, under Lt. Col. Leverett G. Yoder, Commanding Officer, 96th U.S. Engineer Battalion, left Port Moresby for Milne Bay in a Catalina flying boat to reconnoiter the area further. A good site suitable for several airfields was found in a coconut plantation at the head of the bay. Developed by Lever Brothers before the war, the plantation had a number of buildings, a road net, a small landing field, and several small jetties already in place. Impressed by the terrain and the existing facilities, Colonel Yoder turned in a favorable report on the project the next day.20

Colonel Yoder’s report was at once recognized at GHQ to be of the greatest significance. Here at last was a base which if properly garrisoned could probably be held, and GHQ lost no time ordering it to be developed. Construction of the field at BOSTON was canceled on 11 June. The following day, GHQ authorized construction of an airfield with the necessary dispersal strips at the head of Milne Bay. A landing strip suitable for pursuit aviation was to be built immediately, and a heavy bomber field was to be developed later on.21

On 22 June, GHQ authorized a small airfield development at Merauke, a point on the south coast of Netherlands New Guinea, in order to give further protection to Port Moresby’s western flank.22 On the

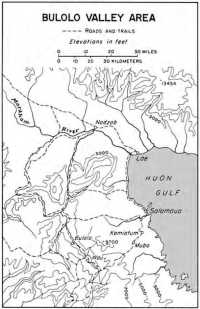

Map 2: Bulolo Valley Area

same day, Milne Bay’s initial garrison—two companies and a machine gun platoon on loan from the 14th Australian Infantry Brigade at Port Moresby—left Port Moresby for Milne Bay in the K.P.M. ship Karsik, and early on 25 June the troops disembarked safely at Milne Bay. Four days later, the K.P.M. ship Bontekoe came into Milne Bay with a shipload of engineering equipment, and Company E, 46th U.S. Engineers. The new contingent immediately began working on the base.

The 7th Australian Infantry Brigade, one of the better-trained militia units, was ordered to Milne Bay from Townsville on 2 July. The brigade commander and advance elements of the brigade left by sea within the week, arriving at Milne Bay several days later. The rest of the brigade arrived shortly thereafter, and a squadron of RAAF P-40’s came in toward the end of the month.23 Port Moresby’s vulnerable eastern flank was no longer uncovered.

The Bulolo Valley

Reinforcement of the troops in the Bulolo Valley, held up in late April when the threat to Port Moresby was at its height, was resumed when the 5th Australian Independent Company, the reinforcing unit, again became available for use in the Bulolo Valley. The company and an attached mortar

platoon were flown to Wau on 26 May; and the troops in the valley, by this time known as KANGA Force, began preparing for the long-delayed attacks on Lae and Salamaua.24 (Map 2)

The attacks were meant to be purely defensive—to delay the enemy and throw him off stride. Should KANGA Force succeed in seizing Lae and Salamaua, it was planned to base pursuit planes immediately at Lae and to send further reinforcements to the

area by sea. To hold the area for two or three weeks, it was hoped, would greatly delay the enemy and cause him to postpone further major action against Port Moresby.25

The operation ran into difficulties. Learning from the natives that the Japanese were planning a major attack on the Bulolo Valley, the commander of KANGA Force had to split his troops and put part of them on the defensive. The first attack of KANGA Force, made with only a part of the unit’s strength, was launched on Salamaua in late June. Sixty Japanese were killed and considerable damage was done, but the approach of enemy reinforcements from Lae caused the attackers to withdraw. A raid on Lae several days later had the same result. Forty Japanese were killed, but KANGA Force had to withdraw again in the face of superior numbers.26

The diversion had failed. KANGA Force obviously was not strong enough to dislodge the enemy, even for a few days.

Kokoda

One further loophole in Port Moresby’s scheme of defense remained. From Buna, a point on the northeast coast of Papua, a difficult and little-known trail led over the Owen Stanleys to Port Moresby via Kokoda, a small plateau in the foothills of the range on which there was a small mountain airfield. General MacArthur’s headquarters realized that an enemy force landing at Buna could quickly invest Kokoda and move on Port Moresby through a nearby 6,000 foot mountain pass known as the Gap (Map I). An inquiry was made into the matter during the first week in June, and it was discovered that Maj. Gen. Basil Morris, who, as GOC, New Guinea Force, was in command of the Port Moresby area, had thus far made no move to send a force to defend it.27

Alive to the danger, General MacArthur wrote to General Blamey on 9 June:–

There is increasing evidence that the Japanese are displaying interest in the development of a route from Buna on the north coast of southern New Guinea through Kokoda to Port Moresby. From studies made in this headquarters it appears that minor forces may attempt to utilize this route for either attack on Port Moresby or for supply of forces [attacking] by the sea route through the Louisiade Archipelago. Whatever the Japanese plan may be, it is of vital importance that the route from Kokoda westward be controlled by Allied Forces, particularly the Kokoda area.

“Will you please advise me,” he concluded, “of the plan of the Commander, New Guinea Force, for the protection of this route and of the vital Kokoda area.”28 General Morris, who was also head of the Australia-New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU), the military government of Papua and the territories of the Mandate, replied several days later, but the reply was scarcely reassuring. There were, Land Forces was told, several ANGAU officers in

the area with radio sets; native constables were to be found in all the villages; and two platoons of the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB), a light reconnaissance unit made up principally of natives, were constantly patrolling the area. The PIB was being reinforced, the report continued, and a company of infantry at Port Moresby was being readied for movement to Kokoda on short notice. It was considered “most unlikely,” the report concluded, that “any untoward incident” could occur in the area without the knowledge of the district officer.29

General Chamberlin made it clear to Land Forces that he did not consider these measures adequate provision for Kokoda’s security. But he decided to take no further action in the matter when he learned that General Blamey’s headquarters had sent a radio message to General Morris ordering him “to take all necessary steps to prevent a Japanese surprise landing along the coast, north and south of Buna, to deny the enemy the grasslands in that area for an airdrome, and to assure that we command the pass at Kokoda.”30

In the radio General Morris was told that, as matters stood, enemy troops that landed at Buna could reach the vital passes in the Kokoda area before reinforcements from Port Moresby could get there. He was reminded that the forces in the Kokoda area were “entirely native, very weak, and probably not staunch,” and was ordered to take immediate steps “to secure the vital section of the route with Australian infantry,” and “to prepare to oppose the enemy on lines of advance from the coast.”31

Five days later, General Morris established a new unit, MAROUBRA Force, and gave it the mission of holding Kokoda. The new force included the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion (less one company) from the 30th Brigade, and the PIB—280 natives and twenty whites. One company of the battalion, Company B, was ordered to Kokoda on 26 June, but did not leave until 7 July, eleven days later. The rest of the battalion, on orders of General Morris, remained on the Port Moresby side of the range, training and improving communications at the southern end of the trail.32