Chapter 9: The Opening Blows in General Vasey’s Area

On 16 November the 32nd Division under General Harding and the 7th Division under General Vasey moved out against the enemy positions at the Buna–Gona beachhead. The Americans were on the right, and the Australians on the left. (See Map VI.) Between them ran the Girua River, the divisional boundary. East of the river, the 126th Infantry troops under Colonel Tomlinson pushed off from Bofu and marched on Buna Village and Buna Mission by way of Inonda, Horanda, and Dobodura. Warren Force, the 128th Infantry and supporting elements, under General MacNider, sent out two columns from its positions along the coast: one along the coastal track leading to Cape Endaiadere; the other against the bridge between the strips. On the other side of the river, the 25th Brigade under Brigadier Eather left the Wairopi crossing early on the 19th and moved on Gona by way of Awala, Amboga Crossing, and Jumbora. Crossing the Kumusi close on the heels of the 25th Brigade, the 16th Brigade under Brigadier Boyd began moving on Sanananda the same day via Isivita, Sangara, Popondetta, and Soputa. Believing like the Americans on the other side of the river that only a small number of the enemy remained, the Australians advanced confidently, sure of a quick and easy victory.

The Attacks on Gona

The 25th Brigade Bogs Down1

Gona was forty miles from Wairopi, and the trail, a poor one frequently lost in mud, lay through bush, jungle, kunai flat, and swamp. The 25th Brigade moved out toward Gona on 16 November, the 2/33 Battalion leading and the 2/25 Battalion bringing up the rear. There was no enemy contact on either the 16th or the 17th but the heat was intense and men began dropping out with malaria and collapsing with heat prostration. The 2/33 Battalion, Lt. Col. A. W. Buttrose commanding, reached Jumbora on the afternoon of 18 November and started to prepare a dropping ground. One of its companies moved forward to Gona to find out if the place was defended.

The company quickly discovered that there were Japanese at Gona. Major Yamamoto’s original allotment of 800 men had been reinforced by an additional hundred

Gona Mission area

men—eighty from the 41st Infantry, and the rest walking wounded from the hospital. The Japanese defense was centered on Gona Mission at the head of the trail. The mission and the surrounding native village area were honeycombed with bunkers, trenches, and firing pits, and every approach was covered. On the west lay the broad mouth of Gona Creek, an expanse of water just wide enough to make an attack from the other side of the creek unlikely. Immediately to the south, and along the east bank of the creek, was an overgrown timbered area which bristled with defense works. To the east a labyrinth of hidden firing pits with overhead cover extended

along the shore for a distance of about three quarters of a mile. With such defenses at their disposal, a resolute garrison could hope to hold for a long time.

The company of the 2/33rd which had gone on ahead to investigate ran into the most southerly of the Japanese defenses late on 18 November. The position, a strong, well-prepared one with cleared fields of fire, was about 1,000 yards south of the mission. Next morning when the 2/31 Battalion, which was now in the lead, came up, it found the sixty men of the company in an intense fire fight with an enemy who was well hidden and well dug in, and whose fire commanded every approach. The 2/31st, under its commander, Lt. Col. James Miller, attacked vigorously but could not penetrate the enemy’s protective fires. By nightfall, when it was ordered to disengage, the battalion had lost thirty-six killed and wounded.

By this time the brigade had outrun its supply. Ammunition had run low, and the troops, hungry, and racked with fevers, were without food. The supply situation righted itself on 21 November when supply planes came over Jumbora and dropped what was needed. Brigadier Eather at once assigned a company of the 2/33 Battalion to guard the supply dump. When a forty-five man detachment of the 2/16 Battalion which had previously been operating in the Owen Stanleys was made available to him that day, he ordered it to take up a position on the west bank of Gona Creek in order to cover his left flank. The 25th Brigade was finally ready to attack.

Eather’s command now numbered less than 1,000 men. Thus far he had no idea of how strong an enemy force was facing him. He did not yet realize that the Japanese defending Gona from carefully prepared positions had roughly the same number of troops that he had.

The attack began early on 22 November. The 2/33 Battalion attacked frontally along the track; the 2/25 Battalion, in reserve, moved out on the left of the track to be in position to attack from the southwest if called upon; the 2/31 Battalion, which was to launch the main attack, pushed forward on the right toward the beach, turned left, and attacked from the east.

Moving through swamp, the troops got as close as they could to the Japanese positions and then went in on the run with bayonets fixed. They did not go far. The leading troops had scarcely reached the Japanese front-line positions when the entire attacking wave was met by such intense enfilading fire from right and left that the troops had to pull back into the swamp. This abortive attack cost the 2/31 Battalion sixty-five killed and wounded.

The next day Brigadier Eather tried again. He switched the 2/25 Battalion from the left flank to the right and ordered it to launch a new attack from the east that afternoon. The 2/25th, Lt. Col. Richard H. Marson commanding, passed through the 2/31st and attacked westward, supported by fire from its sister battalion. The result was the same. No sooner had the troops approached the enemy position than enfilading fire drove them back into the swamp, like the 2/31 Battalion before them. The 2/25th lost sixty-four men in the day’s fighting, only one less than the 2/31st in the attack of the day before.

The situation had turned serious. In only three days of fighting, the brigade had lost 204 killed and wounded. There was little to show for these losses. Although the Japanese

had pulled back along the track, they were still holding the village and the mission and had apparently given as good as they got.

Realizing only too well now that he faced a strong, well-entrenched enemy, Brigadier Eather called for an air strike to soften up the Japanese position. When it was over, he planned to attack again with the 3rd Infantry Battalion which had meanwhile come under his command.

The air force flew over Gona on 24 November and gave the place a thorough bombing and strafing. On the next day the 3rd Battalion, now less than 200 strong, attacked Gona from the southwest. For the first time the attack was well prepared. Not only did the 2/25 and 2/31 Battalions fire in its support, but four 25-pounders which had reached Soputa on 23 November fired 250 rounds of preparatory fire before the troops jumped off. Under the command of Lt. Col. Allan G. Cameron, the battalion got about fifty yards inside the Japanese position but, as in the case of the other attacks, was met by such intense fire that it too had to withdraw. The attack, though a failure like the rest, had one redeeming feature: unlike the inadequately prepared attacks which had preceded it, casualties were relatively light.

The 21st Brigade Opens Its Attack

By now the 25th Brigade was no longer in condition to attack. The total strength of its three battalions amounted to less than 750 men—two were under 300 men, and one, the 2/31st, was under 200. The troops were exhausted, and the number of sick from malaria and other causes was increasing daily. What was left of the brigade could still be used to contain the enemy but could scarcely be expected to do more. The task of clearing Gona fell therefore to General Vasey’s reserve unit, the 21st Brigade, Brig. Ivan N. Dougherty commanding. It was only about 1,100 strong, but the men, after a long rest at Port Moresby, were fit and ready to go.

Advance elements of the new brigade began moving into the line on 28 November. By 30 November the brigade had completely taken over. Pending the receipt of orders returning it to Port Moresby, the 25th Brigade took up a position along the track just south of Gona and lent such support as it could to the 21st Brigade, whose opening attacks on the place were, to Brigadier Dougherty’s chagrin, proving no more successful than its own.2

The capture of Gona, which the Australians had thought initially to be undefended, had turned out to be an extremely difficult task. After almost two weeks of attack, it was still in enemy hands. The Japanese had suffered heavy losses and had been forced to contract their lines until they held little more than a small area immediately around the mission, but they were still resisting with the utmost tenacity, and their perimeter had yet to be breached. The almost fanatical resistance of Major Yamamoto’s troops served its purpose. Australian troops that might otherwise have been available for use elsewhere in the beachhead area were at the end of the month still trying to take Gona.

The 16th Brigade Moves on Sanananda

The Australians Reach the Track Junction

The leading battalion of the 16th Brigade, the 2/2nd, Lt. Col. C. R. V. Edgar commanding, was across the Kumusi by the early morning of 16 November. Edgar struck out at once for Popondetta. Behind him in order were Brigadier Boyd and his headquarters, the 2/3 Battalion, and the 2/1 Battalion.

The men plodded along without rations, tired and hungry. They were gnawing green papayas and sweet potatoes, whatever they could find. Some were so hungry they chewed grass.

A torrential rain struck the next day, turning the track into a sea of mud. Even minor creeks were almost impossible to ford. The troops still had no food, and that day fifty-seven men of the 2/2nd collapsed on the trail from exhaustion, heat prostration, and hunger.

There was no food on the 18th—only a rumor that the planes would drop some at Popondetta. The 2/2nd reached Popondetta that evening, but there was no food there either. Rations would be waiting for them, the troops were told, at Soputa, a day’s march away.

Leaving some troops at Popondetta to prepare an airstrip, the brigade pushed off for Soputa on 19 November, the 2/3 Battalion leading. Rations had been dropped during the morning at Popondetta and caught up with the troops by noon, at which time the men had their first meal in three days. The battalion approached Soputa toward evening and ran into resistance just outside the village. Maj. Ian Hutchinson, the battalion commander, at once deployed his troops for attack. Darkness fell before the battalion could clear out the enemy, and the weary troops dug in.

Next morning the Japanese were gone. Brigadier Boyd sent a covering force to the Girua River crossing, about half a mile east of Soputa, and the 2/3 Battalion marched out along the track in pursuit of the Japanese. Finding no enemy after a half-hour march, the troops were busily eating breakfast by the side of the track, when the 2/1 Battalion, taking the lead, pushed past them. After about fifteen minutes of marching through brush and scrub, the 2/1 began debouching onto a broad kunai flat and there was met by heavy enemy fire, including artillery fire.3

The 2/1st had to run into Colonel Tsukamoto’s most southerly outpost. This outpost was manned by a covering detachment whose mission was to delay an advancing force, thus giving Tsukamoto time to complete preparations for the defense of his main position at the junction of the Cape Killerton and Soputa-Sanananda tracks.

Lt. Col. Paul A. Cullen, the battalion commander, ordered an immediate attack. One company of the 2/1 started moving frontally up the track. A second company started flanking on the right. A third composite company moved out wide on the left. The troops in the center and on the right made some gains at first, but by noon they were meeting strong resistance that balked further progress that day. The company on the left under command of a particularly aggressive young officer, Capt. B. W. T. Catterns, did better. This force, ten officers and eighty-one enlisted men (all that was left of two companies), made a wide detour

around the Japanese right flank, taking particular care to keep clear of the kunai flat which the enemy was defending. By evening Catterns was about two miles behind the Japanese and in position to come in on their right rear.

Creeping stealthily forward, the Australians surprised a number of Japanese at their evening meal, killed about eighty of them, and established a strong, all-around perimeter just east of the track. The Japanese attacked Catterns all day on 21 November, hitting him repeatedly from three sides. Though they were running short of ammunition, Catterns’ troops in a stirring defense not only beat off the enemy but inflicted heavy casualties upon him.

The Australians on the right were quick to profit from the enemy’s absorption in Catterns’ attack. Two companies of Colonel Edgar’s 2/2 Battalion, under Capts. Athelstan K. Bosgard and Jack M. Blamey, pushed around the enemy’s left flank and kept going. By evening they had gained 3,000 yards and had taken an enemy rice dump in an abandoned banana plantation, about 600 yards east of the track. As the Australians moved into the dump area, the Japanese rallied, mounted a strong attack, and brought the drive on the right to a complete halt.

Catterns had meanwhile won his battle. Unable to dislodge him, the Japanese covering force fell back that night to the track junction, abandoning still another prepared defensive position on the kunai flat which it was now no longer in a position even to try to hold.

Catterns lost sixty-seven of his ninety men in the engagement, but his attack was a brilliant success. Not only had it turned the enemy’s flank, but it had made possible the deep penetration on the right. Left with no choice but to withdraw, the Japanese had pulled all the way back to their main defenses in the track junction.

When the attack was over and Catterns’ company had been relieved by a company of the 2/3 Battalion, the Australians had a new east-west front line which was pivoted on the track and lay within easy attacking distance of the enemy positions immediately south of the track junction. The Australian left was just south of the perimeter Catterns had held on the 21st, a slight withdrawal having been ordered there for tactical reasons. In the center the Australians were astride the track several hundred yards to the south of the main Japanese defenses covering the track junction. On the right, to the southeast of the junction, they held the banana plantation and the rice dump, their forward foxholes in the relatively open plantation area being only thirty or forty yards away from those of the enemy.

By this time the strength of the brigade after not quite two months of action had gone down from almost 1,900 officers and men to a force of barely 1,000. Most of the companies in the line were at half strength or less. Catterns’ company, for instance, had only twenty-three officers and men, and the company of the 2/3 Battalion that relieved his unit had less than fifty men. The two companies on the right under Captains Bosgard and Blamey did not exceed forty men each, and the other companies were similarly depleted.

Despite their dashing showing on 21 November, the troops of the brigade were in poor physical condition. They were feverish, hungry, and exhausted, and an ever increasing number were being hospitalized for malaria and other diseases. The brigade was still a fighting force. It could still hold, but its men, for the present at least, were too

worn out to do more. Until they had a little rest another force would have to take over the attack. That force, by decision of General MacArthur, was to be Colonel Tomlinson’s 126th U.S. Infantry, the regiment to which General Harding had given the task of taking Buna Village and Buna Mission.4

General Vasey’s Given the 126th Infantry

Because he could make no radio contact with the 7th Division, and had no assurance that the Australians would get to Soputa in time to close his inward flank, General Harding ordered Colonel Tomlinson on the morning of 18 November to march on Buna via Popondetta and Soputa. Tomlinson, who was then at Inonda, was told that, if the Australians were at Popondetta by the time his leading elements got there, he was to order his troops back to Inonda and, as previously planned, move them on Buna via Horanda and Dobodura.

Early on 19 November Colonel Tomlinson sent Major Bond and Companies I and K, 126th Infantry, across the Girua River to find out if the Australians had as yet reached Popondetta. Bond made contact with an Australian unit just outside of Popondetta at 1130 that day. When he learned that the main Australian force had already passed Popondetta and was on its way to Soputa, Bond ordered his two companies back to Inonda. The regiment, which had been down to its last C ration on 18 November, had rations and ammunition dropped to it at Inonda on the 19th and began marching on Buna, via Horanda, and Dobodura, the 2nd Battalion as before leading.5

At Port Moresby meanwhile, higher headquarters, with General MacArthur’s approval, had decided to give the 126th Infantry to General Vasey for action on the Sanananda track, rather than let it proceed as originally planned to Buna. The point was made that there seemed to be more Japanese in General Vasey’s area than in General Harding’s, and that the main effort would therefore have to be made west of the Girua River. If need be, higher headquarters decided, this was to be accomplished at the expense of the offensive effort on the eastern side of the river.

After this decision, General Vasey was told that he could have the 126th Infantry if he thought he needed it to take Sanananda. Knowing only too well how tired and depleted the 16th Brigade was, General Vasey accepted the offer with alacrity, and General Herring at once ordered Colonel Tomlinson to Popondetta with instructions to report to General Vasey.6

The diversion of the 126th Infantry to General Vasey’s command greatly disturbed General Harding, who could see little justification for the diversion of half his troop strength to General Vasey just as he was about to use it to take Buna. In a message “For General Herring’s eyes only,” he urged that the decision to take the 126th Infantry away from him be reconsidered as likely to lead to confusion, resentment, and misunderstanding. The message went out at 0100, 20 November, and General Herring,

in a stiff note, replied at 1420 that the decision would have to stand, and that he was counting on Harding to make no further difficulties in the matter.7 General Harding had no further recourse. He would have to make out as best he could at Buna without Colonel Tomlinson’s troops.

The Regiment Arrives at Soputa

On 19 November Colonel Tomlinson was ordered by New Guinea Force to report to the 7th Division. Surprised by the order, Tomlinson immediately tried checking with General Harding by radio to make sure that there was no mistake. Unable to make radio contact with Harding, he got in touch with the rear echelon of the regiment at Port Moresby. Learning from the regimental base that he had indeed been released from the 32nd Division, he began moving on Popondetta early on the 20th. Accompanied by a small detail, including Captain Boice, his S-2, and Captain Dixon, his S-3, he reported to General Vasey at Popondetta that afternoon. Vasey at once sent him to Soputa where he was to come under the command of Brigadier Boyd.

The regiment had already begun moving. Major Bond and the men of Companies I and K, who had been on their way back to Inonda when the orders came for the regiment to cross the Girua and come under Australian command, led the march to Soputa. Major Baetcke, whom Colonel Tomlinson had left in command at Inonda, departed for Soputa with the rest of the regiment the same afternoon. Only an airdropping detail and a couple of hundred natives were left at Inonda. Their instructions were to bring forward all the supplies accumulated there as quickly as possible.

Although it had rained during the preceding few days and the march was through heavy mud, the troops made good time. By the evening of 21 November, the whole force—regimental headquarters, Major Boerem’s two companies and platoon of the 1st Battalion, Major Smith’s 2nd Battalion, the 17th Portable Hospital, the Service Company, and a platoon of Company A, 114th Engineer Battalion—had reached Soputa. The men arrived wet and hungry. They were at once attached to the 16th Brigade and assigned a bivouac near Soputa.

General Vasey in the meantime had set 22 November as the day that the Americans were to be committed to action. With the successful advance of the 16th Brigade on 21 November, the plan now was that the brigade would hold and make no further attempt to advance until the Americans had taken the track junction.8

The situation was to the liking of the depleted and exhausted 16th Brigade. As the Australian historian Dudley McCarthy puts it, “ ... the Australians were content to sit back for a while and watch the Americans. There was a very real interest in their observation and a certain sardonic but concealed amusement. The Americans had told some of them that they ‘could go home now’ as

they (the Americans) ‘were here to clean things up.’ “9

The Americans Take Over

The Troops Move Out for the Attack

On the evening of 21 November Colonel Tomlinson, who, with Captains Boice and Dixon, had already reconnoitered the front in the company of both General Vasey and Brigadier Boyd, met with his battalion commanders to plan the next morning’s attack. Little was known about the terrain ahead. The map being used at the time by the 16th Brigade was the provisional 1-inch-to-1-mile Buna Sheet. In addition to being inaccurate, it was blank as far as terrain features in the track junction were concerned. All that it showed was the junction, the Cape Killerton track, and the Soputa-Sanananda track. The rest was left to the troops to fill in.

As he started planning for the attack, Colonel Tomlinson knew only that heavy bush, jungle, and swamp lay on either side of the junction, and that the junction itself was covered by well-prepared enemy defenses, location and depth unknown. The Japanese position, he noted, was an inverted V. To flank it, he would have to attack it in a larger V. His plan was therefore to use Major Bond’s 3rd Battalion to probe the enemy position and move behind it in a double envelopment from right and left. When that maneuver was completed, he would send in Major Smith’s 2nd Battalion and, as he phrased it, “squeeze the Japanese right out.”

Tomlinson quickly worked out the details of the attack. While Major Boerem’s detachment tried attacking frontally along the track, Major Bond’s battalion would move up into the 16th Brigade’s area and, from a central assembly point about four miles north of Soputa, would march out on right and left to begin the envelopments. The 2nd Battalion, in need of rest after its march over the Owen Stanleys, was to remain in the Soputa area in reserve, to be called upon when needed.10

The 2nd Battalion had no sooner settled itself in its bivouac than New Guinea Force ordered it back across the Girua River to rejoin the 32nd Division. General Herring gave the order in response to a request from General Harding for the reinforcement of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, which had run into difficulties on General Harding’s left flank. Major Smith’s battalion left Soputa for the river crossing, half a mile away, early on 22 November. It got there only to discover that the river, which was unbridged, was in flood and could not be forded. A cable was thrown over the river, and the troops crossed in hastily put together rafts, which were guided to the other side by the cable. The battalion finished crossing the river late that evening and fought thereafter on the eastern side of the river.11

Major Smith’s battalion and the bulk of Colonel Carrier’s battalion—some 1,500 men—were now both east of the Girua

River.12 Colonel Tomlinson was left with the command only of the 126th Infantry troops west of it—Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Major Boerem’s detachment, Major Bond’s 3rd Battalion, the regimental Cannon and Antitank Companies, a detachment of the Service Company, and attached medical and engineer troops—a total of 1,400 men.13 The Cannon and Antitank Companies were still at Wairopi and would not arrive at Soputa for some time. The envelopments would have to be made with the troops at hand—Major Boerem’s detachment and Major Bond’s battalion.

Though he was now without his reserve battalion, Colonel Tomlinson proceeded as planned with the envelopments. Major Boerem’s detachment would engage the enemy frontally along the track, and the 3rd Battalion—Companies I and K on the left and Company L on the right—would make the envelopments, supported by elements of Company M.

Companies I, K, and L, strengthened in each case by machine gun and mortar elements from Company M, left the regimental bivouac area near Soputa at 0640, 22 November, their faces daubed with green for action in the swamp and jungle terrain facing them. The troops had been issued two days’ rations, hand grenades, and as much .30-caliber and .45-caliber ammunition as they could carry. Twenty rounds had been issued for each mortar, and arrangements had been made to have additional rations, equipment, and ammunition brought forward as needed by native carriers and by Company M.

The 3rd Battalion moved up to its designated assembly area, and there, about four miles north of Soputa and about 1,000 yards south of the track junction, Major Bond established his CP. Continuing up the track, Major Boerem’s detachment passed through a company of the 2/3 Battalion under Capt. N. H. L. Lysaght, the most advanced unit on the trail, and began moving into position immediately to Lysaght’s front. Companies I and K, Capt. John D. Shirley and Lt. Wilbur C. Lytle commanding, accompanied by Capt. Meredith M. Huggins, battalion S-3, moved out on the left at 0940; Company L, under Capt. Bevin D. Lee, pushed off on the right an hour and a half later. Company M, under Capt. Russell P. Wildey, less such of its machine gun and mortar elements as were with the companies in attack, went into bivouac 200 yards to the rear of Major Bond’s CP. (Map 8)

By 1100 Companies I and K had passed through the Australian troops on the left—two companies of the 2/2 Battalion under command of Capt. Donald N. Fairbrother. At 1445 Company L had reached the right-flank position in the banana plantation held by the remaining two companies of the 2/2nd under Captains Bosgard and Blamey. By this time Major Boerem’s detachment had passed through Captain Lysaght’s company and was dug in immediately to its front. The rest of the 2/3 Battalion was in position behind Lysaght to give the center

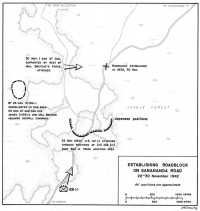

Map 8: Establishing Roadblock on Sanananda Road 22–30 November 1942

depth and serve as a backstop should the Japanese try to break out from the track junction. Colonel Tomlinson’s attack was almost ready to go.14

The Envelopments Begin

At 1100 Company K under Lieutenant Lytle moved out into the no man’s land on the Australian left. Company I under Captain Shirley followed immediately, swinging wide around Lytle’s left. Colonel

Tsukamoto had patrols in the area, and Company K ran into the first of them at 1110, only ten minutes out. The patrol was a small one, and Lytle had no trouble dispersing it. Company I, which was covering Company K from the left, ran into a much larger force at 1215. Shirley started flanking on right and left, and the Japanese after a heavy exchange of fire withdrew. At 1300 Company K again received fire, probably from the same force which had tried to ambush Company I. Lieutenant Lytle started flanking, and the enemy again withdrew.

The two companies suffered light casualties in these encounters—four killed and four wounded. The terrain was heavy bush and swamp, hard to get through, and with no prominent terrain features from which to take a bearing. Having had very little training in patrolling, the troops got their directions skewed during the frequent harassing encounters with the enemy. By the end of the day they found themselves only about 350 yards north of the Australians and not, as they had planned, several times that distance from them.

Captain Lee’s Company L, with a platoon of Company M attached, left the banana plantation, which was on the west bank of a small, easily forded stream, at about 1500 and attacked in a northwesterly direction. After gaining perhaps 200 yards, the company was stopped in its tracks by heavy crossfire. It lost three killed and several wounded and made no further advance that day.

The company had just dug itself in for the night when Colonel Tsukamoto attacked with several hundred fresh 144th Infantry replacements who had reached Basabua the night before and had been immediately assigned to his command. Company L, helped by the two Australian companies, threw back the attack and inflicted heavy losses to the enemy. Company L alone claimed to have killed forty Japanese that night, with a further loss to itself of two killed and one wounded.15

Colonel Tomlinson had planned to continue the attack during the afternoon of 23 November. But with Companies I and K completely out of position on the left, and Company L on the right stopped almost as soon as it moved out of the plantation area, he had to postpone the attack until his flanking companies were more advantageously situated to launch it.

The delay would be an advantage for the front by this time was rapidly becoming organized. The airstrip at Popondetta opened for traffic on 23 November, and a section of four 25-pounders of the 2/1 Australian Field Regiment, Maj. A. G. Hanson commanding, was flown in and went into action the same day from a point north of Soputa. Additional 81-mm. mortars were rushed to Company L, and the available native carriers and troops of Company D began bringing out the wounded and carrying rations to the troops on both flanks.16

Companies I and K, trying to get into position for the attack after their slow advance of the day before, got off to an early start on 23 November. Except for some heavy firing at daybreak, which caused

them no casualties, the two companies met no interference from the enemy all day. Progress was steady, and by 1410 Captain Shirley was able to report an uninterrupted advance.

Though they themselves were not too sure of their location, Companies I and K had by the following evening reached a clearing in the swamp to the left of the track, about 1,200 yards north of their line of departure and about 1,000 west of the Killerton trail. The two companies, now together and in position to attack, settled themselves in the clearing for the night, preparatory to attacking eastward in the morning. After three sleepless nights the weary men were not as alert as they should have been. Japanese patrols approached to within a short distance of their perimeter and suddenly subjected them to heavy crossfire. Taken completely by surprise, the troops pulled back into the swamp in disorder.

Learning of the new setback, Colonel Tomlinson, who had counted on finally attacking on 25 November, at once ordered Major Bond forward to take command of the two scattered companies and to attack on the 26th.

On the right Company L had been making virtually no progress. By the evening of 24 November, it was just where it had been on the evening of the 22nd—on the outskirts of the rice dump, about 200 yards from its line of departure.

The next day, 25 November, the 25 pounders and the mortars gave the Japanese positions a thorough going over. In the process, however, an 81-mm. mortar shell fell short and landed in the command post that Captain Lee was sharing with Captain Blamey. Blamey and one other Australian were killed, and Captain Lee and five others—Australians and Americans—were wounded. Captain Bosgard took over command of the Australians in the area, and Maj. Bert Zeeff of the Americans. Major Zeeff, executive officer of the 3rd Battalion, went forward that night from battalion headquarters. Zeeff reached the plantation area with a few men from Battalion Headquarters Company at about 0100 on the 26th. He slept in the same CP in which Captain Blamey had been killed. At daybreak, after a heavy mortaring of the plantation area by the Japanese, Zeeff inspected the Allied position. He found the Australians in the center of the line, with the Americans in a semicircular position on left and right. The Australians were behind a heavy log breastwork, which, as Zeeff recalls, was “grooved and creased” with enemy fire. The attack obviously was making no progress, and it was clear to Zeeff that he would have to use some other axis of approach if he was to reach the track.

Instead of trying to crash through the strong enemy positions forward of the plantation area, Zeeff tried a new tactic. Leaving part of Company L and twenty men from 3rd Battalion headquarters in place in the plantation area, he recrossed the stream with the rest of his force, about 100 men, side-slipped along the stream for about 600 yards, and prepared to hit the enemy through the gap between Boerem’s positions on the track and the allied right flank.17

Natives with supplies and ammunition for the front lines taking a brief rest along a corduroy road

The long-delayed attack was now finally ready. The 25-pounders and the mortars opened up about 1300, 26 November, shortly after Companies I and K, under Major Bond, pushed off to the eastward toward the Killerton trail. At 1320 the artillery and mortar fire ceased. Companies C and D, Major Boerem’s two companies, attacked straight north along the track, and Company L, with attached elements of Company M and battalion headquarters, under Major Zeeff, crossed the stream and pushed northwestward.

Major Bond’s eastward thrust hit stiff resistance. After several hours of indecisive fighting and the loss of five killed and twenty-three wounded, Bond’s two companies consolidated about 700 yards west of the Killerton trail. Major Boerem’s companies ran into such heavy machine gun and mortar fire that they were stopped after an advance of less than a hundred yards. Colonel Tomlinson, Captain Boice, Captain Dixon, and other members of the regimental staff who were observing Boerem’s attack were pinned to the ground and managed to extricate themselves only after the enemy fire lifted. Zeeff did somewhat better. He pushed ahead for about 350 yards before running into heavy fire from several hidden machine guns that killed and wounded several of his men. The advance, which had begun so promisingly, was brought to a complete halt. The troops began aggressive patrolling to pinpoint the enemy positions, but so skillfully were they

“Fuzzy wuzzy” natives carrying a wounded soldier to a first aid station in the rear area

hidden that Zeeff’s patrols could not at once locate them. Dusk came, and the troops dug in for the night in foxholes which immediately filled with water.18

The Establishment of the Roadblock

Early on 27 November Major Bond reported that, although everything on his front was at a stalemate, he was holding and preparing to attack. The next morning, while Colonel Tomlinson was adding up his battle casualties (which by that time were more than 100 killed, wounded, and missing), the Cannon and Antitank Companies under Captain Medendorp finally reached Soputa from Wairopi. The men, exhausted and very hungry, were given food and allowed to rest, their first respite in some time.

Colonel Tsukamoto meanwhile continued attacking savagely on his left, on the assumption apparently that the Allied

troops on that flank presented the greatest threat to his position in the track junction. The Japanese attacked all day on 27 November. Their pressure was directed principally at Zeeff, whose forward perimeter was now between 300 and 400 yards from the track, but intermittent glancing blows were sent also against the Australian and American positions in the banana plantation. The heaviest attack of the day came toward evening. It was beaten off with the help of Major Hanson’s 25-pounders and the excellent observation of one of Hanson’s forward observers, Lt. A. N. T. Daniels, who was with Zeeff. Daniels switched the artillery fire from Zeeff’s front to Bosgard’s and back again to such good effect that the Japanese attack soon dwindled to nuisance fire only. In repelling the Japanese, Zeeff’s troops suffered considerable casualties, and the Australians in the plantation area, now down to about fifty men, lost Captain Bosgard, whose death came only two days after Captain Blamey’s.

Zeeff had meanwhile been joined by seventy men from Major Boerem’s detachment—thirty-seven men from Company C and thirty-three from Company D. Still facing the task of cleaning out the Japanese immediately to their front, the group spent the day of the 28th in patrolling and locating the hidden enemy positions. One of Zeeff’s platoon leaders, 1st Lt. Henry M. Crouch, Jr., accompanied by Lieutenant Daniels, stalked and ambushed a party of eight Japanese. In a particularly daring foray, Sgt. Robert R. McGee of Company L led the patrol that located the main enemy position standing in the way of the advance and helped to wipe it out. The next day, rations, ammunition, and hand grenades were brought forward and distributed to the troops. Zeeff was ready to push forward again. His orders were to move northwest to make contact with the troops on the left flank, who, he was told, would try to hit the Soputa-Sanananda track the next day.19

General Vasey had hoped to open up a new front for his Australians by having them cut over from the Killerton trail to the Soputa-Sanananda track at a point well to the north of the area in which the Americans were operating. On 28 November, on the very eve of the American attack, he learned that the plan was impracticable. Strong Australian patrols sent out on 24 and 26 November reported that the intervening swamp barred access from one track to the other that far north. The farthest north the crossing could be made, General Vasey was told, was where the Americans were about to make it. The Americans, in short, had stumbled upon exactly the right spot to make the envelopment, and the envelopment was ready to go.

The main effort was to be on the left. On 29 November Colonel Tomlinson ordered Major Baetcke, his executive officer, to proceed to Major Bond’s position on the left flank and take command of the troops there. These troops now included Companies I and K, elements of Company M and 3rd Battalion headquarters, and the Cannon and Antitank Companies. The last two units had moved up from Soputa and taken up a position on Bond’s rear. Baetcke’s instructions were to attack eastward on 30 November and, in concert with a further frontal attack by Major Boerem, and an

attack on the right by Major Zeeff, to establish a roadblock to the rear of the main enemy position in the track junction.

Baetcke reached Bond’s position late on the morning of 29 November. He was accompanied by 1st Lt. Peter L. Dal Ponte, commanding officer of the Service Company, whom he had chosen to be his assistant. As nearly as could be made out, Bond’s position to the west of both the Cape Killerton trail and the Soputa-Sanananda track lay about 700 yards from the one and 1,600 yards from the other. Baetcke quickly worked out a plan of attack. The line of departure was to be about 200 yards northeast of Bond’s main position and about 500 west of the Killerton trail. At the prescribed time the troops would attack straight east and move astride the Soputa-Sanananda track 1,400 yards away.

The units in assault would be under command of Major Bond, who was to be accompanied by Lieutenant Daniels. The attacking force of 265 men was to include Company I under Captain Shirley, the Antitank Company under its commanding officer Capt. Roger Keast, a light machine gun section of Company M, and a communications detachment from 3rd Battalion headquarters. Company K and the Cannon Company, both under command of Captain Medendorp, were to be in support. Led by Lieutenant Lytle, Company K would take up a position behind the line of departure and execute a holding attack by fire. The Cannon Company, under its commander, 1st Lt. John L. Fenton, would remain in reserve to the rear of Company K and would come to its aid should it come under enemy attack.

Early on the morning of 30 November the 126th Infantry attacked the Japanese on the right, in the center, and on the left. The attack on the right by Company L met no opposition for about 150 yards but was then brought to a complete halt by a strong Japanese force that Colonel Tsukamoto had deployed there for just that purpose. Companies C and D in the center did not do as well and gained only a few yards. The real success of the day was registered on the left.

Major Bond’s force left the line of departure at 0900, after a ten-minute artillery and mortar preparation. It moved in column of companies, Company I leading. The supporting fire of Company K proved very effective and drew strong, retaliatory fire from the enemy. At first the troops had no trouble dealing with the enemy to the front. About four hundred yards beyond the line of departure, as they started moving through a large kunai patch, they were met from virtually all sides by hostile rifle, mortar, and machine gun fire. Major Bond was wounded about 0930 and had to be evacuated. The attack lost its momentum and for a time bogged down completely. Learning of the difficulty, Major Baetcke came up from the rear, rallied the troops, and, leading the way, cleared the enemy out of the kunai flat. Captain Shirley took command and the attack continued.

After eliminating the resistance on the kunai flat, the troops fought several minor skirmishes with small parties of the enemy who seemed to be patrolling the area. About a thousand yards out, they ran into jungle and swamp terrain more difficult than anything they had previously encountered. The undergrowth in the jungle was almost impenetrable, but the real difficulty came when the men reached a 300-yard stretch of knee-deep swamp. The Japanese, who had cut fire lanes commanding the swamp, temporarily stopped Captain Shirley’s troops with knee mortar and machine gun fire just as they

were trying to clear it. Shirley’s men finally succeeded in crossing the swamp and dispersing the enemy. A little way out of the swamp the troops came upon a well-traveled trail leading generally eastward and followed it. At 1700 Company I’s scouts reported an enemy bivouac area directly ahead.20 What followed is best told by one who was present.

At this point Captain Shirley ordered his Company I, deployed with two platoons abreast and supporting platoon following in center rear, to insert bayonets and assault the ... enemy position (endeavoring to get his objective prior to darkness). The attack was well executed and successful. Captain Shirley, after driving the enemy from this position, organized perimeter defense by emplacing his rifle platoons of Company I west of the road; 1 LMG Squad, Company M, near the road on the northern portion of the perimeter; and 1 LMG Squad, Company M, on the southern portion of the perimeter. AT Company had been [deployed] east of the road. The perimeter was in and established by about ... 1830. ... About two hours later we were getting heavy mortar fire in the perimeter and later attacks from the northeast on the AT Company’s sector, and subsequently from the northwest on Company I’s sector. Both were repulsed with few casualties.21

In storming the bivouac area, the Shirley force had killed a score of Japanese; it had captured two disabled Ford trucks, a variety of auto repair tools, a little food, and some medical supplies; most important of all, it had gained its objective. The captured bivouac area, a comparatively open, oval-shaped space about 250 yards long and 150 yards wide, lay astride the track 1,500 yards to the north of the track junction and approximately 300 south of the Japanese second line of defense higher up on the track. The long-sought roadblock, to the rear of the Japanese positions in the track junction, had finally been established.22

Zeeff’s Recall

Now that the Shirley force had cut through the Japanese line and established itself on the track, it remained to be seen whether the Zeeff force, now only a few hundred yards south of it, could link up with Shirley. Held up on 30 November while Shirley was moving steadily to his goal, Major Zeeff experienced no difficulty moving forward the next day. His men advanced northwest in order to join Shirley in the roadblock. The Japanese, apparently diverted from the threat on their left by the new threat on their rear, had relaxed their pressure, and Zeeff’s force moved steadily ahead.

Early that afternoon Zeeff’s troops crossed the track and, moving to a point about 250 yards west of it, surprised and wiped out a party of thirty-five to forty Japanese. Zeeff reported the skirmish to Colonel Tomlinson

at 1515 and, told him that he thought his troops had crossed the track. To prevent enemy interception of the message Zeeff spoke in Dutch, a language familiar to many of the Michigan troops present, and a Dutch-speaking sergeant at headquarters interpreted for Colonel Tomlinson.

Zeeff dug in at 1625 on Tomlinson’s orders. Within the hour the Japanese struck from right and front. After a brisk fire fight in which Zeeff lost two killed and three wounded, the enemy withdrew. At 2100 Colonel Tomlinson ordered Zeeff to move back to the east side of the road as soon as he could and to push northward from there to make the desired juncture with the troops in the roadblock. At that point the wire went dead, and Zeeff was on his own.

The troops fashioned stretchers for the wounded from saplings, telephone wire, and denim jackets, and the next morning began moving from their night perimeter on a northeasterly course to recross the track as ordered. Their withdrawal was no easy task. The enemy kept up a steady fire, and it was here that Pvt. Hymie Y. Epstein, one of Zeeff’s last medical aid men, was killed. Epstein had distinguished himself on 22 November by crawling to the aid of a wounded man in an area swept by enemy fire. He had done the same thing on 1 December. This is the scene on the afternoon of the 1st, as Zeeff recalled it:

I was prone with a filled musette bag in front of my face; Epstein was in a similar position about 4 or 5 feet to my left. Pvt. Sullivan was shot through the neck and was lying about 10 feet from me to my right front. Epstein said, “I have to take care of him.” I said, “I’m not ordering you to go, the fire is too heavy.” [Despite this], he crawled on his stomach, treated and bandaged Sullivan, then crawled back. A few minutes later, Sgt. Burnett ... was shot in the head, lying a few feet from Sullivan. Epstein did the same for Burnett, and managed to crawl back without being hit.

Epstein’s luck did not hold. To quote Zeeff again: “The next morning just before daybreak, Pvt. Mike Russin on our left flank was hit by a sniper. Epstein went to him, ... but did not return as he was shot and killed there. We buried him before moving out . ...”23

Toward evening, while the troops were digging in for the night at a new perimeter a few yards east of the track and about 500 south of the roadblock, Sergeant McGee, whom Zeeff had sent out to reconnoiter the area immediately to the northward, came back with discouraging news. Strong and well-manned enemy positions, beyond the power of the Zeeff force to breach, lay a couple of hundred yards ahead. Zeeff had scarcely had time to digest the news when the Japanese were upon him again. After a wild spate of firing, the attack was finally beaten off at a cost to Zeeff of five killed and six seriously wounded.

By this time Colonel Tomlinson was satisfied that Zeeff could neither maintain himself where he was nor break through to the roadblock. His perimeter was directly in the line of Allied fire, and there was no alternative but to get him out of there as quickly as possible before he was hit by friendly fire or cut to pieces by the enemy. The wire had been repaired, and at 2000 that night Tomlinson ordered Zeeff to leave the area immediately, warning him that it was to be mortared the next day. Zeeff was to bring

Making litters for the wounded

back his sick and wounded but was not to bother burying the dead.

The job of making litters for the six newly wounded began at once and went on through the night. Saplings were cut and stretchers made. By 0330 the stretchers were loaded and the march began. Walking in single column, and guiding themselves in the dark with telephone wire, the troops moved south for about 900 yards and then turned east toward the familiar little stream that flowed past the banana plantation.

The terrain was swampy, and the march slow. The men were spent and hungry, and eight soldiers had to be assigned to each stretcher. Four would carry it for fifty yards, and then the other four would take over. Two of the stretchers broke down en route, and the troops struggled forward with the two wounded men as best they could. Shortly after daybreak the procession reached the stream, where Captain Dixon was waiting with stretchers and stretcher bearers. The wounded were attended to immediately, and the rest of the troops, most of whom had been eleven days in combat, returned to regimental headquarters and were allowed to rest.

Zeeff had not accomplished his mission, but he and his troops had done something that in retrospect was electrifying. They had threaded their way through the main Japanese position on the track, manned by some 2,000 enemy troops, and had come out in

good order, bringing their wounded with them.24

The Ensuing Tasks

General Vasey had by now lost all hope of an early decision on the Soputa-Sanananda track. He simply did not have enough troops to secure such a decision. The 16th Brigade had less than 900 effectives left and was wasting away so rapidly from malaria and other sicknesses that there was no longer any question of assigning it any further offensive mission, especially if the mission was of a sustained nature as any offensive thrust on the track was likely to be. All that the brigade was now in condition to do was hold. If not relieved in the near future, it would soon be unable to do even that.25

The weight of the attack would therefore have to continue on the Americans. But they too were beginning to sicken with malaria, and their effective strength was between 1,100 and 1,200 men, not the 1,400 it had been on 22 November when they had first been committed to action. This was scarcely a force sufficient to reduce a position as strong as that held by Colonel Tsukamoto, especially since the latter actually had more men manning his powerful defense line than the Allies had available to attack it.