Chapter 6: Deployment for Battle

Reinforcement and Reorganization of the PERSECUTION Task Force

Prior to 22 April the PERSECUTION Task Force had little information concerning the intentions of the 18th Army, but soon after that date the task force learned that the Japanese unit had planned to move from Wewak toward Hollandia. In May and June, East Sector operations had produced many indications that a westward displacement of the 18th Army was in full swing.

The Decision to Reinforce Aitape

For some time the G-2 Section of Headquarters, ALAMO Force, did not believe that the movements noted by the PERSECUTION Task Force presaged a Japanese attack on the Aitape perimeter. Instead, ALAMO Force considered it more probable that the 18th Army was merely establishing strong points along the coast west from Wewak in order to delay Allied pushes eastward or to provide flank protection for the main body of the 18th Army which might attempt to bypass Aitape and Hollandia to the south and join the 2nd Army in western New Guinea.1 Strength was added to these beliefs when patrols of the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB),2 operating far inland beyond the Torricelli Mountains, reported westward movement of many small Japanese parties along inland trails.3 Because more definite information was lacking, ALAMO Force, until mid-June, clung to the idea that the 18th Army might bypass Aitape.4

The first identifications of organized enemy units east of Aitape had been secured during operations near Marubian in mid-May, when it was found that elements of the 20th Division were operating in that area.5 Later the same month the PERSECUTION Task Force discovered from captured

documents and prisoners that elements of both the 20th and 41st Divisions were along the Dandriwad River.6 Documents captured by AIB patrols at the end of May indicated that the two divisions were to attack both Hollandia and Aitape. At that time the ALAMO Force G-2 Section estimated that the 18th Army might be mounting a two-pronged assault on Aitape,7 and by early June the G-2 Section believed that the 20th Division was in place east of Aitape, waiting only for the 41st Division to move up before launching an assault against the PERSECUTION Task Force. The other division of the 18th Army, the 51st, was thought to be at Wewak, and it was believed that the unit was not to move westward. Thus, by early June it seemed evident to ALAMO Force that the Japanese parties previously encountered south of the Torricelli Mountains comprised service troops no longer needed at Wewak or troops who had started moving westward before 22 April.

The ALAMO Force G-2 Section expected that the 20th and 41st Divisions could be in position to attack the PERSECUTION Task Force by the end of June.8 General Krueger believed that a Japanese assault could gain only temporary containment of Allied forces at Aitape and that an attack would be a diversionary measure aimed at delaying further Allied advances in western New Guinea. Such action would have much to recommend itself to higher Japanese headquarters which, the ALAMO Force G-2 Section correctly believed, had already become reconciled to the loss of the 18th Army.9

On 17 June General MacArthur questioned ALAMO Force concerning the advisability of reinforcing the PERSECUTION Task Force. Though he considered it improbable that an 18th Army assault could seriously menace the Allied position at Aitape, he thought it possible that the PERSECUTION Task Force might need reinforcing if the 18th Army should muster all its available strength for an attack. He informed General Krueger that the 43rd Infantry Division was scheduled for an early move to Aitape in order to stage there for operations farther west. But that division could not arrive at Aitape before the end of the first week in July. General MacArthur therefore suggested that if it appeared necessary to reinforce the PERSECUTION Task Force before July, a regiment of the 31st Infantry Division might be made available immediately.10

To these suggestions General Krueger replied that many preparations had already been made at Aitape to meet any attack by the 18th Army. For instance, both ammunition supply and hospitalization facilities had recently been increased. General Krueger believed that the forces already at Aitape

could, if properly handled, beat off any Japanese attack that might occur prior to the 43rd Division’s arrival. If it looked necessary, however, he might send the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team to Aitape. He considered that unit preferable to a regiment of the 31st Division, since he wanted to keep that division intact for a future operation. He requested an early decision from General MacArthur as to which unit should be moved to Aitape.11

While higher headquarters was reaching a decision concerning reinforcements, new information obtained by the PERSECUTION Task Force prompted a change in plans. Documents captured after mid-June indicated that the Japanese were to complete a thorough reconnaissance south, southeast, and east of the PERSECUTION Task Force’s perimeter by the end of June in preparation for an attack by the 20th and 41st Divisions. This attack, it now appeared, awaited only the completion of the reconnaissance and the arrival of the bulk of the 41st Division in the forward area.12

By this time the PERSECUTION Task Force’s 155-mm. artillery had been sent to new operational areas in western New Guinea and tentative plans had been made to send the Beaufighter and Beaufort squadrons of No. 71 Wing westward also. General Gill, upon receiving the new information concerning enemy intentions, requested that the air support squadrons be retained or replaced; that a battalion of 155-mm. howitzers be sent to Aitape; and that the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team be moved forward immediately.13

A few days later General MacArthur’s headquarters, which had secured the information from radio intercepts, informed General Krueger that the 18th Army planned to attack about the end of the first ten days in July, employing 20,000 troops in the forward area and another 11,000 in reserve.14 ALAMO Force and the Allied Naval Forces immediately rounded up ships to send the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team to Aitape, where the unit arrived on 27 June. A 155-mm. howitzer battalion was shipped to Aitape a few days later and No. 71 Wing was ordered to remain there. At the same time General Krueger reconsidered his decision not to employ part of the 31st Division and ordered preparations made to move the 124th Regimental Combat Team of that division to Aitape. Efforts were also made to speed the shipment of the 43rd Division from its New Zealand staging area to Aitape.15

When all the reinforcements arrived, the PERSECUTION Task Force’s strength would equal two and two-thirds divisions. General Krueger therefore decided that a corps

headquarters would be needed at Aitape. He chose for the command at Aitape Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall who, together with his staff of XI Corps headquarters, had recently arrived in New Guinea from the United States. The change in command was not to entail a change in the principal mission of the PERSECUTION Task Force—defense of the Tadji airstrips. To carry out his mission, General Hall was instructed to break the initial impetus of the apparently impending 18th Army attack and, when the strength of the PERSECUTION Task Force and the tactical situation permitted, undertake a vigorous counterattack. With these instructions in mind, General Hall assumed command of the PERSECUTION Task Force as of midnight 27–28 June.16

While this change in command was being effected, more information concerning the plans of the 18th Army was obtained from radio intercepts and captured documents. It became known that the 20th Division was to cross the “Hanto” River on 29 June, executing attacks toward Afua and East Sector headquarters installations, which were located at Anamo, on the beach just west of the Driniumor’s mouth.17 General Headquarters forwarded this information to ALAMO Force with little attempt at interpretation, but the ALAMO Force G-2 Section decided that the Hanto River was probably the Driniumor. The prospective attack, ALAMO Force believed, would be launched during the night of 28–29 June at a point about two miles inland from the mouth of the Driniumor. It was considered probable that the 78th Infantry, 20th Division, would aim for control of the Afua–Palauru trail, while the 80th Infantry moved on Anamo. Assuming the success of its initial attack, the 20th Division apparently planned to assemble at “Hill 56,” tentatively located about 4,000 yards northwest of Afua, and then push on toward the Tadji airfields. ALAMO Force estimated that the maximum strength with which the 20th Division could attack was about 5,200 men.18

If this interpretation of available information was correct, General Hall had but one day to prepare his new command to meet the attack of the 18th Army.

Reorganizations and Redispositions

As soon as General Hall and the few members of his XI Corps staff that he had brought forward became acquainted with the situation in the Aitape area, Headquarters, XI Corps, assumed the role of PERSECUTION Task Force Headquarters, using many men of Headquarters, 32nd Division, until the rest of the corps staff could reach Aitape. Next, the command structure of the task force was rearranged, some changes in names were made, and several troop redispositions were effected.

The western part of the main line of resistance around the airfields—the area previously assigned to the West and Center Sectors—became the responsibility of the Western Sector, under Brig. Gen. Alexander N. Stark, Jr. The eastern section of the main line of resistance was held by the Eastern Sector under General Gill. This unit also set up an outpost line of resistance along the Nigia River. General Martin’s command, redesignated the PERSECUTION Covering Force, was to continue to hold the delaying position along the Driniumor River. The

western boundary of the covering force was a line running south from the coast along Akanai Creek and the X-ray River, a little over halfway from the Driniumor to the Nigia.

Since no attacks were expected from the west, troops assigned to the Western Sector comprised principally engineers. The Eastern Sector was composed of the 32nd Division less those elements assigned to the PERSECUTION Covering Force. Supply, administration, and evacuation for the covering force were responsibilities of Headquarters, 32nd Division, which, for these purposes, acted in its administrative capacity rather than in its tactical role as Headquarters, Eastern Sector. All three tactical commands operated directly under General Hall’s control.19

While these changes were being made, the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team (less the 148th Field Artillery Battalion) had arrived at BLUE Beach and had been assigned to General Martin’s operation control. The combat team was commanded by Brig. Gen. Julian W. Cunningham, while the dismounted (and oft disgruntled about it) men of the 112th Cavalry Regiment were led by Col. Alexander M. Miller, III.20 The cavalry regiment was about half the strength of an infantry regiment. It comprised only two squadrons, each composed of three troops, as opposed to the three battalions of four companies each in an infantry regiment. Instead of the three heavy weapons companies organic to the corresponding infantry unit, the 112th Cavalry had only one heavy weapons troop. Moreover, the cavalry unit had arrived at Aitape with less than its authorized personnel. At no time during operations at Aitape did it number more than 1,500 men, in comparison with the 3,000-odd of an infantry regiment.21

Initially, it was planned that the 112th Cavalry would take up positions in the Palauru area to defend the right rear of the PERSECUTION Covering Force and act as General Martin’s reserve. General Hall, deciding that the Driniumor River line needed strengthening, changed this plan and on 29 June sent the regiment forward to the X-ray and Driniumor Rivers. Leaving the rest of the regiment at the X-ray, the 2nd Squadron moved on to the Driniumor and took up defensive positions in the Afua area. Upon the arrival of this squadron at the river, the extent of the Driniumor defenses that were previously the responsibility of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, was reduced and at the same time operational control of the infantry battalion passed to General Cunningham. This addition still did not bring the strength of the latter’s command up to that of an infantry regiment.22

About the same time, the mission of the PERSECUTION Covering Force was changed.

Chart 9: The PERSECUTION Task Force:, 28 June–11 July 1944

General Krueger, who was maintaining close touch with the situation at Aitape, wanted the Japanese to be met and fought to a decision as far on the east flank as possible. Previously, Generals Hall and Gill had assumed that the covering force might be gradually forced back from the Driniumor, but now General Hall ordered the force to retreat only in the face of overwhelming pressure. The 112th Cavalry had been released to General Martin’s control to aid in the execution of this new mission, and the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, was also made available to him. On 29 June the infantry battalion took over about 3,000 yards of the Driniumor line between the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry. Close artillery support for the covering force was provided by the 120th and 129th Field Artillery Battalions, which emplaced their 105-mm. howitzers near Anamo. Company B, 632nd Tank Destroyer Battalion, moved forward to the mouth of the Driniumor at the same time. All units reconnoitered routes of withdrawal back to the next delaying position, the Koronal Creek–X-ray River line, and planned defenses along that line so that in case withdrawal became necessary, confusion would be minimized. General Martin issued orders that no unit was to leave the Driniumor line without his instructions.23

Gathering Combat Intelligence

General Hall had strengthened the Driniumor line in the expectation that the 20th Division would attack on or about 29 June. But there was no attack on that date. It was therefore decided that the information upon which the expectation was based had been incorrectly interpreted. If so, greater credence had to be placed on conflicting evidence from radio intercepts and captured documents indicating that the 18th Army was to attack on 10 July. This interpretation was given some corroboration when a prisoner captured on 30 June divulged that the 20th Division was planning to move against the Driniumor line between 1 and 10 July.24

Reconnaissance in Force Eastward

General Hall, in an attempt to locate the 20th Division, ordered the PERSECUTION Covering Force to send strong patrols east of the Driniumor to the Harech River. A few patrols, moving along the coast, got almost as far as Yakamul, but so efficient had Japanese counter-reconnaissance operations become that this was as close as any Allied patrols came to the Harech River during the period 30 June through 10 July. In the southern sector of the Driniumor line patrols confirmed previous reports that the Japanese maintained a counter-reconnaissance screen along Niumen Creek. Here Japanese units were digging in and holding wherever and whenever patrol contacts were made. These enemy groups were not large, however, nor did the Japanese patrols encountered in the Yakamul area appear to be particularly strong. All American patrol efforts failed to disclose any evidence of large, organized Japanese units or movements. Yet both the task force and ALAMO Force were sure that at least two regiments of the 20th Division and elements of the

41st Division were located somewhere in the area between the Harech and Driniumor Rivers.25

The fact that no large enemy units could be located east of the Driniumor caused considerable worry at ALAMO Force headquarters, and General Krueger was unhappily aware that the development of the situation in front of the PERSECUTION Covering Force was being left to the volition of the Japanese. It is also possible that he wished to hurry the battle he knew was impending at Aitape in order that some of the forces there could be freed for operations farther westward once the Japanese attack had been turned back. Whatever the case, on 8 July he instructed General Hall to seize the initiative by sending a strong reconnaissance in force across the Driniumor to ascertain the enemy’s intentions and dispositions.26

These instructions got a cool reception at the headquarters of the PERSECUTION Task and Covering Forces. General Hall had planned to send at least two battalions of the 124th Infantry on an amphibious enveloping movement down the coast to Nyaparake to land in the rear of the 20th Division. General Martin was deeply disturbed when he learned that the reconnaissance units would have to be taken from the Driniumor line, which he already considered inadequately manned to meet the expected Japanese attack. Although he preferred the amphibious plan to the overland movement, General Hall could not argue the point with ALAMO Force and, by the same token, General Martin, realizing that General Hall was under pressure from higher headquarters, chose not to argue with his immediate superior. General Hall postponed the 124th Infantry’s operation until 13 July, and he ordered General Martin to begin the reconnaissance in force on the morning of 10 July.27

General Hall now had at his disposal fifteen infantry battalions and two understrength, dismounted cavalry squadrons. Three infantry battalions of the 32nd Division and the two cavalry units were assigned to General Martin’s PERSECUTION Covering Force. To accomplish his primary mission—defense of the Tadji strips—General Hall felt it necessary to hold at least six infantry battalions of the 32nd Division near the airfields. The three battalions of the 124th Infantry (which had arrived in echelons at BLUE Beach beginning on 2 July) he decided to hold out of action temporarily either as a reserve or, when possible, to execute the amphibious envelopment already planned. Having thus committed the 124th Infantry and six battalions of the 32nd Division to stations in the Tadji-BLUE Beach area, General Hall had no choice but to take the reconnaissance in force units from General Martin’s Driniumor River troops. By this action, the PERSECUTION Covering Force’s defenses were weakened along the very line where the Japanese were first expected to strike.28

For the reconnaissance in force eastward, General Martin chose the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, and the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry. The infantry was to advance along the coast and the cavalry overland from Afua. The maneuver was to be carried out in an aggressive manner. Minor opposition was not to slow the reconnaissance, and the forces were to push rapidly eastward to the Harech River. Once on the Harech, the two units were to consolidate, patrol to the south and east, and prepare for further advances upon orders from General Hall. Units remaining along the Driniumor were to send out patrols to their respective fronts in the area between the reconnaissance units in order to locate any Japanese forces in that area.29

The reconnaissance started about 0730 on 10 July as the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, Company B leading, waded across the mouth of the Driniumor. Progress down the coast was rapid and uneventful until 1000 when, at a point about three miles east of the Driniumor, the leading elements were held up by a Japanese unit estimated to be a company in strength, which was dug in along the coastal trail. The infantry could not take the enemy position by assault, and artillery support from the 105-mm. howitzers at Anamo was requested. This fire, quickly and accurately delivered, killed some Japanese and scattered the rest. Company B resumed the advance but was stopped again at enemy positions on the banks of a small stream 300 yards farther east. This time one artillery concentration failed to dislodge the Japanese and, finding it impossible to outflank the enemy defenses, the forward infantry units were disengaged while a second concentration was brought down on the enemy positions.

After the artillery fired, Company B continued the advance until 1745, by which time it had reached a point less than a mile west of Yakamul. In terrain that afforded good positions for night defenses, the company dug in, while the rest of the battalion established a perimeter running westward along the coastal trail. Not more than fifty Japanese had actually been seen during the day. Casualties for the 1st Battalion were five killed and eight wounded.30

At the southern end of the Driniumor line the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, right arm of the reconnaissance in force, delayed its departure until the 1st Squadron moved up to the Driniumor from the X-ray and did not leave Afua until 1000. The 2nd Squadron did not follow any trail but, having been ordered to avoid contact with the enemy during the first part of the movement eastward, cut its way through heavy jungle over alternately hilly and swampy terrain. The nature of the terrain slowed progress so much that at 1445, when the advance was halted for the night, the squadron was not more than a mile east of the Driniumor. No contact with enemy forces had been made during the day.31

General Hall was not satisfied with the progress the two arms of the reconnaissance had made during the day. He was especially disappointed in the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, which, he felt, should have been able to move farther eastward. Both the infantry and cavalry units were ordered to resume the advance eastward in a more aggressive manner on the morrow. Further efforts were to be made by both units to maintain contact with forces back on the Driniumor. The 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, had been unable to maintain contact, either physically or by radio, with regimental headquarters.32

Redispositions Along the Driniumor

Back on the Driniumor sweeping changes in dispositions had taken place.33 (Map 5). The 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, had to assume responsibility for the positions vacated by the 1st Battalion. The 2nd Battalion’s sector now extended from the mouth of the Driniumor to the junction of the Anamo–Afua trail with the river bank. This was a straight-line distance of about 5,000 yards, but configurations of the Driniumor’s west bank made it over 6,000 yards (almost three and a half miles) on the ground.

Company F, 128th Infantry, was on the left of the 2nd Battalion guarding the west bank from the mouth inland about 3,900 yards or over two miles. The northern portion of the company zone was very well organized, having been developed by various units since the middle of May, but positions in the southern quarter of the sector had not been completed. To the right of Company F was Company E, in position along a front of 1,250 yards. South of Company E, tying its right flank into the left of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, was Company G, spread over a front of about 1,000 yards, Company G’s machine gun positions and riflemen’s foxholes were closer together—about sixty to seventy-five yards apart—than those of the other 2nd Battalion companies. The company also had some low barbed wire strung in front of its position. Company E had little or no wire and its strong points were about ninety yards apart. Company G’s lines were shortened about 100 yards late in the afternoon when a rifle platoon of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, assumed responsibility for that much of the company’s area.

By nightfall all the riflemen of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, were in the new defensive positions. The heavy machine guns of Company H were disposed along the bank of the river between infantry strong points (bunkers or groups of foxholes), their lines of fire tied in with those of the rifle companies’ light machine guns and automatic rifles (BARs). Company H’s 81-mm. mortars were emplaced about 200 yards west of the river and were registered in on area targets along the bed and the east bank of the Driniumor. The 60-mm. mortars of the three rifle companies had targets overlapping those of the larger weapons. The forward battalion command post was about 800 yards west of the Driniumor, behind the center of Company E’s sector. The remainder of the battalion headquarters, together with a tank destroyer platoon, was located on the coast just west of the river’s mouth. The battalion had no reserve which it could move to meet a Japanese attack.

Map 5: Situation Along the Driniumor, Evening, 10 July 1944

South of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, the 3rd Battalion of the 127th Infantry had a sector about 2,500 yards or almost a mile and a half long. Company I was on the left, with every available man in position along 1,400 yards of curving river bank. Strong points were about 100 yards apart and the company had no protecting wire. Company K, with a nearly straight stretch of bank about 1,100 yards in length to hold, was on the right of Company I. The dispositions of Company M’s heavy weapons were similar to those of Company H, 128th Infantry. Company L of the 127th, which had sent many patrols east of the Driniumor during the day and which had lent one of its rifle platoons to Company G, 128th Infantry, was not on the line. Instead, the unit

Driniumor River, in area held by the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry

guarded the battalion command post, which was situated about 700 yards west of the Driniumor behind Company K.

The 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, south of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, was responsible for about 3,000 yards of the Driniumor line. This distance was divided about equally between Troop B on the left (tying into the lines of Company K, 127th Infantry) and Troop A on the right. The line extended to a point about 500 yards south of Afua, where Troop C took up support positions. Troop C did not place many men along the river but concentrated at Afua to refuse the south flank of the PERSECUTION Covering Force and to provide a reserve for the 112th Cavalry. Weapons Troop’s heavy machine guns were disposed for the most part in the sectors of Troops A and B. Headquarters of the 112th Cavalry and General Cunningham’s command post were situated about 200 yards west of the Driniumor behind Troop B. A small rear echelon group of the 112th Cavalry remained on the X-ray River at the Afua–Palauru trail crossing to protect the overland line of communications back to BLUE Beach.

Along the coast west of the Driniumor, at Anamo, Anopapi, and Tiver, were located field artillery units, tank destroyers, and the headquarters installations of the PERSECUTION Covering Force.34 Communications from these units to those on the Driniumor were carried out for the most part by radio, although some telephone wire was used. Units along the river communicated with each other by means of sound-powered telephone.

Intelligence, 10 July

Many bits of information concerning the intentions of the 18th Army were now available to the PERSECUTION Task Force. Corroborating evidence for the idea that an attack might take place on 10 July was secured that day when the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, captured a member of the 237th Infantry, 41st Division. This prisoner divulged to interrogators in the forward area that the Japanese attack would come that night, but back at task force headquarters, where final interrogations were made, his information was evaluated as indicating the assault would be made within the next day or two. The prisoner believed that the attack was to have two axes, one along the coast and the other across the Driniumor about midway between Afua and the river’s mouth.35

In addition to the foregoing information, the units remaining on the Driniumor reported increasing enemy activity east of that river during the 10th. Japanese movements seemed especially intensified in the zone patrolled by the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry. One battalion patrol, returning to the Driniumor on 10 July after three days along Niumen Creek, reported having seen at least two large groups of Japanese, one about fifty-five strong, along the east bank of the Niumen. These troops appeared to have been moving in a purposeful manner along freshly cut trails and were said to have been in good condition, well clothed, and strongly armed. Another patrol of the same battalion worked its way east of the Niumen on the morning of 10 July and discovered a recently

established Japanese bivouac area, capable of holding about sixty-five troops. On its way back to the Driniumor, this patrol ambushed two small, well-armed parties of Japanese only 700 yards east of the 3rd Battalion’s lines.36

Another patrol, moving east in the northern sector of the 3rd Battalion zone, encountered two groups of Japanese on the west bank of the Niumen. These two parties, both of platoon size and well-armed, were moving rapidly south along new trails. The American patrol saw only a few more Japanese during the day but discovered many signs of heavy enemy movement between the Niumen and Driniumor. The patrol leader, an unusually imperturbable sergeant of Company I, 127th Infantry, who had had extensive patrol experience, was greatly excited by these signs of Japanese activity. Although his patrol had not actually seen more than fifty enemy soldiers, the sergeant felt that a strong attack on the lines of Company I, 127th Infantry, or Company G, 128th Infantry, was imminent.37

On the basis of this and other patrol reports Lt. Col. Edward Bloch, 3rd Battalion commander, alerted his force to expect a Japanese attack during the night. The sergeant’s information and conclusions also prompted Colonel Bloch to assign a rifle platoon of his reserve company, L, to Company G, 128th Infantry, on his left flank. There is no evidence that Colonel Bloch informed higher headquarters of his actions and there is no indication that the Company I patrol sightings were reported to an echelon higher than General Cunningham’s headquarters.38

North of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, patrols of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, reported only one unusual contact during the 10th. A party from Company G, operating near Niumen Creek, encountered a combat patrol of twenty Japanese. A running fire between the two groups ensued, and the American patrol was forced back to the Driniumor. A report of this action was sent to regimental headquarters, but there is no evidence that it was relayed to any higher echelon of the task force.39

In the zone of the 112th Cavalry, a patrol from the 1st Squadron, moving east along a line parallel to and north of the 2nd Squadron, surprised a party of ten Japanese about 1,200 yards east of Afua. These enemy troops, who were armed with at least one machine gun, retired to prepared defenses after a sharp skirmish. The American patrol leader estimated that there were at least forty Japanese, all well-armed, milling around in the same vicinity. This information reached task force headquarters late in the afternoon.40

Despite the fact that cumulative intelligence now presented strong evidence that a major Japanese attack was about to be launched against the Driniumor River line, the G-2 Section of Headquarters, PERSECUTION Task Force, apparently did not believe that such an attack was imminent. Some sort of attack was expected at an indefinite future date, but the PERSECUTION Task Force daily intelligence report for 10 July, published about 1800 that day, gave little

indication that an immediate Japanese assault could be expected:–

Westward movement of strong enemy patrols including intense activity just E [east] of NIUMEN CREEK indicates possible strong outposts to cover assembly of main body in preparation for attack.41

At PERSECUTION Covering Force headquarters the prevailing opinion was more apprehensive. General Martin was concerned about the possibility of a Japanese attack during the night of 10–11 July, and he was worried over the disposition of the forces along the Driniumor, which had been seriously weakened by the movement eastward of the reconnaissance-in-force units. What the attitude of most of the rest of the staff officers and unit commanders of the PERSECUTION Task and Covering Forces was is unknown, although General Martin had warned the Driniumor River units to be on the alert and Colonel Bloch of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, certainly expected some action during the night.42

Back at task force headquarters, General Hall had little choice but to accept his G-2’s estimate at face value. Although he had been expecting a Japanese attack ever since 5 July, he had little or no reason to believe that the night of 10–11 July might pass any differently than those immediately preceding it.43 About 2330 he radioed to General Krueger that the situation in the PERSECUTION Covering Force’s area gave every indication that the reconnaissance in force eastward could be resumed the next morning according to plans.44 Within fifteen minutes after the dispatch of this message, it became evident that the situation along the Driniumor was anything but well suited to the plans of the PERSECUTION Task Force.

The 18th Army Moves West

At approximately 2350 Japanese light artillery (70-mm. or 75-mm.) began lobbing shells into river bank positions occupied by elements of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry. This fire, giving the first indication that the Japanese had artillery so far west, was augmented within a few moments by mortar and machine gun fire. At 2355 the Japanese artillery became silent. At this signal, Japanese infantry began charging across the Driniumor into the 2nd Battalion’s defenses.45

The 18th Army’s Plan

The 18th Army had been long preparing its attack and had developed elaborate plans for the “annihilation” of the PERSECUTION Task Force. Prior to 22 April the 18th Army had started withdrawing westward from Wewak, but after the Allied landings at Hollandia and Aitape, plans for the future employment of the 18th Army had to be revised. On 2 May Imperial General Headquarters ordered the 18th Army to bypass Hollandia and Aitape and join the 2nd Army in western New Guinea. General Adachi, the 18th Army’s commander, had no stomach for such a maneuver. A previous bypassing

Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi, Commanding General of the Japanese 18th Army

withdrawal from the Huon Peninsula in late 1943 and early 1944 had cost his army dearly, and movement across the Ramu and Sepik Rivers in March and April gave promise that his losses of men and supplies would increase at an alarming rate. He believed that a withdrawal through the hinterland to western New Guinea might literally decimate the 18th Army and perhaps result in much greater loss than would an attack on Hollandia or Aitape. On the other hand, should it remain immobile at Wewak, the 18th Army could contribute nothing to the Japanese war effort and would lose all vestiges of morale. Terrain in the Wewak area was not suited to protracted defense nor to farming which could make the 18th Army self-sufficient, and supplies available there could only last until September. The only means by which more supplies could be obtained, morale kept high, and the Japanese war effort furthered, was to attack and seize Allied positions.46

Although his orders to bypass and withdraw to western New Guinea were not canceled until mid-May,47 General Adachi, apparently on the basis of earlier broad directives from the 2nd Area Army,48 had already produced an outline plan of an attack against the Hollandia–Aitape area. At first he considered retaking Hollandia, with the seizure of the Aitape region as a necessary preliminary step. However, he soon realized that the Hollandia venture was overambitious and he therefore limited the project to an attack on Allied forces at Aitape.

The initial plans for a move against Aitape, evolved at 18th Army headquarters on 26 April, set 10 June as the date for the completion of attack preparations. The assault units were to be the 20th and 41st Divisions supported by the 66th Infantry of the 51st Division.49 On or about 1 May the first outline plan was supplemented by an attack order setting forth details of objectives, assignments, and timing. The 20th

Division, already ordered to secure the Yakamul area and screen the deployment of the rest of the 18th Army, was now instructed to soften all Allied resistance east of the Nigia River by the end of June. It appears that General Adachi believed the PERSECUTION Task Force’s main line of resistance to be located along the Nigia, and there are indications that as early as the first week of May he thought that the first strong Allied defensive positions would be encountered along the Driniumor River.

After securing the ground west to the Nigia River, the 20th Division was to throw its strength against the Nigia defenses while the 41st Division, after the 20th had broken through the Nigia line, was to move from Chinapelli northwest toward the Tadji airfields. The 20th Division’s attack was apparently to be made along a narrow front at some point between Chinapelli and the mouth of the Nigia. Provision was also made for a simultaneous assault along the beach to divert Allied attention from the main offensive. The date for the assault on the supposed main line of resistance of the PERSECUTION Task Force was now set for 10 July.50

The first step in mounting the offensive against Aitape was to concentrate most of the available strength of the 18th Army at Wewak. By the end of May over 50,000 troops of that army had been withdrawn across the Ramu and Sepik Rivers and, with the exception of the regiments of the 20th Division already dispatched toward Aitape, were reorganizing at Wewak.51 By no means were all the troops available to General Adachi trained in ground combat. Many of them were service personnel, others belonged to air force ground units, and some were naval troops which had recently passed to the control of the 18th Army. The 20th Division’s three infantry regiments were greatly understrength and probably totaled few more than 3,000 trained infantrymen. The entire strength of the division, including about 1,000 men of the 26th Field Artillery Regiment and other organic or attached troops, was about 6,600 as of the end of May. The 41st Division contained less than 4,000 infantry effectives and a total strength of some 10,700. The 66th Infantry of the 51st Division, also scheduled to participate in the attack on Aitape, did not number more than 1,000 men. Altogether, General Adachi mustered for service in the attack about 20,000 troops. Of these, not more than 8,000 were trained infantrymen. About 2,500 were artillerymen with 70-mm. and 75-mm. guns, some 5,000 were to be engaged in supply operations in direct support of the infantry and artillery, and the remaining 4,500 were various types of overhead and service personnel who were to fight as infantry or engage in normal duties such as signal operations, maintenance, headquarters work, and the like. Another 15,000 troops were to be engaged in the movement of supplies forward from Wewak toward the front. The remaining 20,000 troops of the 18th Army were to garrison the Wewak area or, because of shortages of supply and poor physical condition, could not be expected to engage in active operations.52

Considering his supply situation, General Adachi was possessed of a rather remarkable degree of aplomb when he ordered the

18th Army to attack. He considered that his men had enough infantry weapons—though there were only 13,142 rifles, 726 machine guns, 561 grenade dischargers, 22 light mortars, thirty-six 75-mm. mountain guns, and forty-two 70-mm. guns—but only half enough ammunition. Ammunition for the 70-mm. and 75-mm. guns was critically short. Communications equipment was nearly gone and was not expected to last through June. There were serious shortages of clothing, blankets, and mosquito nets. The last-named deficit promised a high incidence of malaria, and there was a critical shortage of malaria preventives. Other types of medical supplies were sufficient except those for diarrhea and skin diseases. Food, even with half-rations for all troops, would not last beyond the end of August. Except for a single submarine mission late in May, the 18th Army could get no more supplies by sea or air, and General Adachi knew it. The army had few trucks or barges with which it could move the supplies it possessed and had little equipment with which to improve existing roads or build new ones. Barge and truck movements westward could be made only at the mercy of Allied air and sea patrols (mostly Australian aircraft and Seventh Fleet PT boats based at Aitape) while heavy rains further hampered troop and supply movements over all roads and trails west from Wewak.53

General Adachi soon found that his sanguine expectations of clearing the PERSECUTION Task Force from the area east of the Nigia River by the end of June were not to be realized. The 20th Division’s westward movement had been delayed in the series of skirmishes along the coast east of the Driniumor in late May and early June. Further delay occurred as inclement weather and increasing Allied air and PT activity made the 18th Army depend entirely upon hand-carry for supply movement. The 20th Division’s forward units ran out of supplies in mid-June and halted, as did advance elements of the 41st Division. The bulk of the 41st Division, slowly moving westward from Wewak, was now assigned the task of hand-carrying supplies forward.54

Practically the only result of the employment of the 41st Division as a service unit was a complete loss of troop morale. The division’s efforts to improve the supply situation proved futile, the physical stamina of the troops dropped because of unsanitary conditions, and the units engaged in supply movements found it next to impossible even to sustain themselves. Part of the 20th Division had to exist temporarily on less than eleven ounces of starchy food per day, and some of the forward units subsisted for a short while solely on sago palm starch. No reserve of supplies could be built up in the forward area.

By mid-June General Adachi realized that he was almost certainly going to encounter a strong American force along the Driniumor, but even an attack against that river line could not be mounted by the end of the month. On the 19th he therefore postponed efforts to attack the expected defenses along the Driniumor until at least 10 July, leaving to an undetermined date an attack on the Nigia line.55

Deployment for the Attack

By the end of June General Adachi, taking a realistic view of the situation, knew

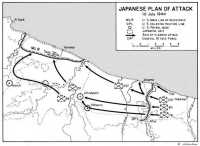

Map 6: Japanese Plan of Attack, 10 July 1944

that his supply problems alone had already defeated him. Nevertheless, he felt that he could not withdraw without offering battle and, exhorting his troops to overcome Allied material and numerical advantages by relying on spirit, he ordered the 20th and 41st Divisions to attack the Driniumor defenses on the night of 10–11 July.56

The final attack plan was issued at 1500 on 3 July from the 18th Army’s forward command post somewhere among the upper reaches of the Harech. (Map 6) The focal point of the 18th Army’s attack was an island in the Driniumor on the left of the sector held by Company E, 128th Infantry, an island designated by the Japanese “Kawanaka Shima” (literally, Middle of the River Island). The main body of the 237th Infantry, Col. Masahiko Nara commanding, was to cross the Driniumor at Kawanaka Shima beginning at 2200, 10 July. Support fire was to be provided by the 1st Battalion, 41st Mountain Artillery, and was scheduled to start at 2150. Elements of the 8th Independent Engineers were to reinforce the 237th Infantry. After crossing the Driniumor, Colonel Nara’s force was to move west toward Koronal Creek and

northwest to clear Anamo and the other Paup villages, on the coast west of the Driniumor’s mouth.

South of Kawanaka Shima, on the left of the 237th Infantry, the 20th Division was to begin its attack at 2300, under cover of support fire from the 26th Field Artillery. The 20th Division’s units were divided into two groups. The Right Flank Unit, under Col. Tokutaro Ide and comprising the 80th Infantry, with attached engineers, artillery, and medical personnel, was to line up across the river from the right of Company E, 128th Infantry. Also operating under Colonel Ide was the Yamashita Battalion, which, though positive identification cannot be made, was probably the 1st Battalion, 237th Infantry. Below Colonel Ide’s command and opposite Company G, 128th Infantry, was the Left Flank Unit, under Maj. Gen. Sadahiko Miyake, Infantry Group commander of the 20th Division. General Miyake’s force consisted of the 78th Infantry (under Col. Matsujiro Matsumoto) and attached engineers, artillery, and medical units. After forcing a way across the Driniumor, the Right Flank Unit was to move directly overland to Chinapelli, while the Left Flank Unit was to seize and clear the Afua area and move on to Chinapelli over the Afua–Palauru trail.

There was a fourth Japanese assault unit, the Coastal Attack Force, under Maj. Iwataro Hoshino, the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 41st Mountain Artillery. Major Hoshino’s group comprised the headquarters and the 1st Battery of his battalion; a machine gun section of the 6th Company, 237th Infantry; and the Regimental Gun Company, 237th Infantry. The Coastal Attack Force (the unit which had delayed the advance of the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, along the coast on 10 July) was to co-operate with the attack of the 237th Infantry and pin down with artillery fire the Allied units located on the coast east and west of the Driniumor’s mouth.

Assuming the success of the initial attack on the Driniumor line, the Japanese assault units were to prepare to drive on the Tadji airstrips. The 237th Infantry was responsible for initial reconnaissance of Allied defenses expected to be encountered along the Nigia River, while the 20th Division was to regroup at Chinapelli. The 66th Infantry, 51st Division, was to move forward as quickly as possible after the attack on the Driniumor line, and, bypassing the Tadji area to the south, was to strike the Allied main line of resistance from the Kapoam villages, southwest of the airfields.57

During 10 July the two assault echelons of the 20th Division moved slowly into position. Part of the 78th Infantry got into an area allocated to the 80th, causing considerable confusion and probably accounting for the movements of Japanese troops in various directions as observed by PERSECUTION Covering Force patrols during the day.

Because of communications difficulties, the 237th Infantry and the 41st Mountain Artillery were not alerted for the attack until 7 July. The units were delayed further in last-minute attempts to secure supplies and, as a result, did not start moving forward to the line of departure until 9 July. Their final attack orders were not issued until the afternoon of the 10th, and the 237th Infantry’s rear elements were just moving into line along the Driniumor when the guns of the supporting artillery opened fire at the scheduled hour, 2350.58