Chapter 8: The Battle of the Driniumor, Phase II: The 18th Army Retreats

Securing the Afua Area

With the arrival of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 127th Infantry, in his area, General Cunningham decided to make another attempt to relieve Troop C, 112th Cavalry.1 The latter’s position had been uncertain for two days, but it was definitely located on the morning of the 23rd on the basis of a report from the platoon of Company I, 127th Infantry. Having reached Troop C on the evening of the 21st, this platoon had succeeded in fighting its way through Japanese lines to South Force’s command post on the 23rd. General Cunningham now sent part of the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, to relieve Troops A and B, 112th Cavalry, from their positions north of Afua. The two cavalry units were to attack west toward Troop C and, simultaneously, the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, was to push southeast toward the isolated troop.

The Relief of Troop C

The double envelopment started early in the afternoon of the 23rd. At first, the attacks of the cavalry and infantry units were closely coordinated, orders to both being issued through a radio aboard an artillery liaison plane hovering overhead. But shortly after the combined attack began, Troops A and B had to retire eastward to avoid fire from the advancing infantry battalion. Troop A thereupon turned south and retook Afua against light opposition. During the afternoon the two cavalry units established new defenses around Afua, extending their lines about 300 yards west of the village.2

About 1500 the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, having encountered only scattered

The Afua Area

resistance, moved into Troop C’s perimeter from the northwest, just as the Japanese launched a strong attack from the southwest. Darkness came before all the enemy had been repulsed, and plans for the battalion’s further advance had to be abandoned. The combined perimeter was harassed by mortar fire throughout the night, as were the two cavalry units at Afua.

Early on 24 July the 2nd Battalion sent patrols out from the perimeter—patrols which reported strong enemy defenses on high ground to the north and south. Attempts by the 2nd Battalion and Troop C to break through enemy lines to the southeast and the Afua–Palauru trail were unavailing, as was an effort by Company B, 127th Infantry, to move southwest from General Cunningham’s command post area to the combined infantry-cavalry position. Company E, 127th Infantry, trying to move northeast from the perimeter to establish contact with Company B, could get no place. The Japanese were tenaciously defending all tracks, trails, and ridge lines in the heavily jungled ground northeast of the perimeter.

General Gill, who thought South Force had sufficient troops to drive off the Japanese without difficulty, was by now dissatisfied with the situation in the Afua area. He apparently believed that South Force was not making a strong enough effort to clear the ground north and northwest of Afua, and there was a definite feeling at his headquarters that the situation around Afua was by no means critical. His G-2 Section estimated that the Japanese in the Afua area comprised only remnants of the 78th Infantry trying to break back through the restored Driniumor line to the east. If this were not the case, said General Gill’s G-2 officers, then the Japanese at Afua were merely stragglers attempting to raid South Force bivouacs for food.

But General Cunningham thought that the Japanese on his right and rear comprised elements of both the 78th and 80th Infantry Regiments, which, he believed, were trying to outflank South Force and seize control of the Afua–Palauru trail. He felt that South Force was doing everything possible to drive the Japanese away, but, as he pointed out to General Gill, the enemy was dug in on commanding ground throughout hilly and heavily jungled terrain northwest, west, and southwest of Afua, making it necessary to reduce each position by slow and costly infantry assault. Finally, said General Cunningham, the 127th Infantry had not yet been able to deploy its entire strength for further attacks and was therefore not bearing a full share of the necessary fighting.3

General Cunningham’s estimates were far closer to the truth than those at Covering Force headquarters, although even the South Force commander was underestimating the Japanese scale of effort. By 24 July the Miyake Force had been concentrated north and northwest of Afua behind South Force. General Miyake had under his command over 1,000 men—remnants of the 20th Division units which had crossed the Driniumor on the night of 10–11 July and during the next day or two. Moreover, relatively fresh troops of the 79th Infantry, 20th Division, and division headquarters were now in the Afua area. By evening of the 24th, there were at least 2,000

Japanese troops on South Force’s right flank and rear.

South Force operations on 25 July met with more success than had been anticipated, for very heavy fighting had been expected. Early that morning Companies B and E, 127th Infantry, established contact about 500 yards north-northeast of the 2nd Battalion-Troop C perimeter. Over the escape route thus opened, Troop C withdrew to the dropping ground, ending its four days of continuous combat against superior Japanese forces. The unit had lost about thirty men from Japanese action and from sickness during the period.

Afua and the Triangle

With Troop C relieved, General Cunningham decided to exploit the success of the early morning action and launch an attack south and west from the dropping ground. His plan was to clear the area between that ground and the 2nd Battalion’s position by pushing all Japanese found in the area to the region south of the Afua–Palauru trail and on into the Torricelli Mountains.

About 1100 Company A, 127th Infantry, moved into position at the western edge of the dropping ground and faced south. Company B lined up on A’s right and Company E on B’s right, at the edge of a series of jungled ridges. Company C was in reserve. One platoon of Company G was to maintain contact between Companies B and E, which were separated by some 200 yards of thick jungle. The 2nd Battalion (less Company E and the Company G platoon) was to remain at the old Troop C perimeter until sure that no more Japanese were in that area. Then it was to push south to the Afua–Palauru trail west of Company E.

The attack began about 1130. Companies B and E soon met strong opposition, but Company A, closely followed by Company C, moved rapidly toward the Afua–Palauru trail, encountering only scattered rifle fire and reaching the trail late in the afternoon at a point about 300 yards west of Afua. There it tied its left into the lines of the 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry (back in Afua since the 23rd), and pushed its right about 200 yards west along the trail to the left flank of Company B, which had not yet been able to bring its entire strength up to the Afua–Palauru trail. On B’s right, the Japanese held a strong point on a low ridge over which the trail passed, and the company had to bend its lines about 150 yards to the north and west around this enemy position.

Company E and the Company G platoon, meeting increasing resistance, reached the 2nd Battalion perimeter in the early afternoon and joined the rest of the battalion in a drive south toward the Afua–Palauru trail. By dusk the battalion had crossed the trail and was digging in about 100 yards south of that track. There was a gap of at least 100 yards between the left of the 2nd Battalion and the lines of Company B, and there was another gap on the battalion’s right, or west, flank, where Company G had been cut off during the move south. At nightfall the company was located on a ridge crossing the trail about 150 yards northwest of the main body and about 800 yards west of Afua, near the old Troop C perimeter.

The advance south had been generally successful, but by late afternoon there were clear indications that many Japanese troops remained in a triangular area formed by the dropping ground, Afua, and Company G’s ridge-line position. Rifle fire, intensifying as darkness approached, harassed the rear

and right flank of the two battalions, and the Japanese began intermittently to drop light artillery or mortar shells into the banana patch area, where the command posts of South Force, the 112th Cavalry, and the 127th Infantry were now located. Finally, Japanese patrols, coming in from the west, had scouted the banana patch area during the day, action which seemed to presage an enemy attack during the night. To get out of range of the enemy fire and danger of enemy attack, General Cunningham moved the command post installations 500 yards to the north before dark.

During the night an unknown number of Japanese troops moved around the right rear of the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, joining enemy units which had been bypassed the preceding afternoon. By early morning on the 26th, these troops had secured control of trails leading southeast through heavy jungle from the banana patch to a point on the Afua–Palauru trail near the 2nd Battalion’s command post. Meanwhile, 127th Infantry patrols had found a Japanese map which indicated that the 66th Infantry, 51st Division, was concentrating in the Kwamagnirk area.

As a result of the information concerning the 66th Infantry and because of the growing Japanese activity south and west of the banana patch, General Cunningham decided to change South Force dispositions. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, was withdrawn from its lines along the Afua–Palauru trail and sent back to the dropping ground where it established a new westward-facing perimeter in expectation of Japanese attacks from that direction. The 2nd Battalion extended its lines to the east to cover the area vacated by the 1st, and at the same time managed to eliminate the Japanese salient which had held up Company B the previous afternoon. Efforts to extend the 2nd Battalion’s lines west to Company G were unsuccessful, and at nightfall on the 26th that unit was still in its isolated ridge outpost 150 yards from the main body.

All day on the 26th Japanese troops milled around in the rear—north and northwest—of the 2nd Battalion. At the same time the battalion received continuous harassing rifle and machine gun fire from the south, its front. It was expected that the Japanese might attack from the south and west during the afternoon, and plans were made for the 2nd Battalion’s withdrawal to Afua if the enemy attacked from more than one direction. However, the enemy scale of effort in the afternoon did not seem to warrant such a withdrawal. The battalion therefore remained in its positions and managed to push its lines slightly south. General Cunningham alerted all South Force to expect an enemy attack on the night of 26–27 July, but the hours of darkness proved almost abnormally quiet.

Nevertheless, General Cunningham’s redispositions and plans to withdraw the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, had been well advised. Despite heavy losses from combat, starvation, and disease in the Driniumor area, General Adachi was still determined to clear the Afua area, and continually sent fresh troops across the river south of that village. The 66th Infantry, which, with attached units, was at least 1,000 men strong, had crossed the Driniumor on or about 24 July. Bypassing the right flank of South Force, the regiment had moved into the heavily jungled high ground west of the banana patch and dropping ground. In addition, the remnants of the 237th Infantry, probably about 300 men strong, had finally arrived in the Afua area on 25 July and had passed to the control of the Miyake Force.

Rear elements of the 20th Division, including additional men from the 26th Field Artillery and engineer units, had also crossed the Driniumor south of Afua. The number of Japanese troops in the South Force area by nightfall on the 26th of July was at least 2,500 and may have been over 3,000.

Actually, neither the Japanese nor South Force had any accurate knowledge of each other’s strengths and dispositions in the Afua area. Each side complained that the other held isolated strong points, none of which appeared to be key positions. Both sides employed inaccurate maps, and both had a great deal of difficulty obtaining effective reconnaissance. In the jungled, broken terrain near Afua, operations frequently took a vague form—a sort of shadow boxing in which physical contact of the opposing sides was ofttimes accidental.

On the morning of the 27th General Cunningham decided to use the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, to resume an advance southward to locate Japanese forces below the Afua–Palauru trail and to overrun an enemy observation post on high ground about 500 yards southwest of Afua. After artillery fire on suspected enemy assembly areas south of its lines, the 2nd Battalion started moving at 1000. Only scattered rifle fire was encountered and by 1245 the battalion had taken the observation post. A new defensive line, anchored on the Driniumor near Afua and lying generally 400 yards south of the Afua–Palauru trail, was set up. The battalion’s right flank was about 800 yards west of the river, near the outpost of Company G, which had not participated in the southward drive.

General Cunningham had wanted the 2nd Battalion to develop its new line as a base for future operations, but Japanese troops moved onto the Afua–Palauru trail behind the battalion, threatening its communications, and the unit was therefore ordered to return to the morning line of departure. Since the enemy made little effort to hold his trail positions, this withdrawal was accomplished without incident by 1800. An outpost of platoon size was left on a ridge about 200 yards southwest of Afua. The rest of the battalion, still less Company G, dug in along the Afua–Palauru trail in essentially the same positions it had occupied the previous night. Meanwhile, the 66th Infantry had become active in the high ground 300 yards west of the dropping ground and banana patch, and elements of that unit or the Miyake Force again began patrolling along the jungle tracks leading southwest from the banana patch. During the morning Japanese patrols armed with light machine guns occupied two low ridge lines west and southwest of the dropping ground, while other enemy groups moved into high ground immediately west of South Force’s new command post area.

Since these Japanese maneuvers seriously threatened the safety of South Force command and supply installations, General Cunningham ordered the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, and part of the 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, to clear the enemy from the high ground. By late afternoon these units, by dint of foot-by-foot advances against stubborn opposition, had cleared the Japanese from three strong ridge-line positions west and southwest of the dropping ground. This action gained at least temporary security for South Force’s supply base and apparently discouraged the 66th Infantry from making any more attacks for the time being.

The next morning, 28 July, the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, continued mopping up west of the dropping ground and occupied some enemy ridge defenses which

had held out overnight. The rest of South Force engaged in local patrolling without finding any trace of sizable, well-armed groups of Japanese, but General Cunningham remained certain that large-scale Japanese attacks were imminent. He therefore decided to shorten his lines to obtain stronger defenses and to secure a base of operations for further attempts to clear enemy troops from the Afua–dropping ground-Company G triangle.

Late in the afternoon, in accordance with these plans, the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, moved north and set up a new westward-facing defensive line running south from the dropping ground and the 1st Battalion’s left. This line lay generally 200 yards west of the Driniumor. The 3rd Battalion and the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, remained in their river defenses. The 1st Squadron withdrew north and northwest from Afua, tied its right into the 2nd Battalion’s left, and established a new line running generally southeast to the 2nd Squadron’s right, anchored on the Driniumor about 2,000 yards north of Afua. With the exception of Company G, which remained in an isolated perimeter on the ridge west of Afua, South Force was now in a long, oval-shaped perimeter, ready to meet Japanese attacks from any direction. For the third time in seventeen days Afua had been abandoned to the Japanese.

The next morning the 1st Squadron and the 2nd Battalion started a coordinated attack south and west into the Afua–dropping ground-Company G triangle. The 1st Squadron encountered no opposition as it pushed south along the west bank of the Driniumor and quickly reoccupied the river line to within 300 yards of Afua. The cavalry unit then halted until the infantry battalion had moved equally far south. The latter had been delayed along the diagonal track leading southwest from the banana patch, and a dangerous gap had been created between the two arms of the advance.

The 2nd Battalion’s attack had started at 0900, with Company F on the left (east) and Company E on the right. Small patrols, moving along ridge lines west of the main line of advance, protected Company E’s right. The battalion’s progress was slow since the Japanese had set up trail blocks along the diagonal track, and since it was also necessary to probe the rough, jungled terrain on both sides for hidden enemy strong points. Company E, about 1015, found itself halted by a Japanese position containing infantrymen estimated at company strength. In an attempt to carry this position by fire and movement, the unit lost 7 men killed and 9 wounded. Company E withdrew about 200 yards to the north and called for artillery and 81-mm. mortar support. This fire was soon forthcoming and Company E moved forward again at 1400. A few slight gains were made, but the Japanese, who had established a defense in depth, clung tenaciously to every foot of ground and the advance was again halted. More artillery fire was placed on the suspected locations of enemy strong points, and Company E started southward for a third time about 1530.

While Company E was deploying to begin its third attack, the entire right flank of the 2nd Battalion was harassed by Japanese patrols. As a result the 1530 advance could not develop, and about 1800 the right flank units of the battalion withdrew. While this withdrawal was under way, an estimated two companies of enemy infantry struck from a low jungled ridge immediately west of Company E. Company F had not met much opposition during the day but had moved slowly southward so as not to

lose contact with the rest of the battalion. Now it was withdrawn into the main battalion perimeter to aid in throwing back the enemy attack from the west. A sharp fire fight took place on the battalion’s right, and 2 men were killed, 39 wounded, and 9 were counted as missing. Total casualties for the day were 11 killed, 50 wounded, and 9 missing.

Though harassing by enemy patrols continued, the 2nd Battalion was successful in beating back the main attack after some twenty minutes of hard fighting. General Cunningham felt that the battalion had done all that could be expected of it during the day and ordered it to withdraw to the dropping ground. This retreat, begun about 1930, was accomplished during the night of 29–30 July, and the battalion reached the dropping ground about 0830 on the latter day. Because this withdrawal left the 1st Squadron exposed to attacks from the northwest and west, the latter unit was withdrawn to the lines of the 2nd Squadron, north of Afua.

During the 30th and 31st of July only local patrol action was carried out by most units of South Force as General Cunningham prepared plans for another offensive into the triangle. Major combat activity revolved around the withdrawal of Company G, 127th Infantry, from its exposed outpost west of Afua. On the afternoon of the 29th the unit had been driven more than 400 yards east of its original position by Japanese attacks and had established new defenses on high ground about 300 yards west of Afua. On the 30th the company was surrounded and spent all day fighting off a series of small-scale attacks. The next morning it fought its way north to the dropping ground, where it arrived about 1330. Thence, it moved on to the Driniumor and joined the rest of the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, which had switched positions with the 3rd Battalion.

South Force’s oval-shaped perimeter now varied in depth from 400 to 800 yards. The 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, was on the north, facing the river but with its left flank bent westward. On the Driniumor south of the 2nd Battalion was the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, the lines of which now reached to within 1,500 yards of Afua. Extending about 400 yards west of the 2nd Squadron’s right flank was Troop C of the 1st Squadron. The rest of the 1st Squadron faced west and anchored its north flank on the banana patch. North of the 1st Squadron were the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 127th Infantry, extending the western side of South Force’s perimeter north through the dropping ground, 500 yards beyond to General Cunningham’s command post, and to the north tip of the 2nd Battalion’s lines.

During the period from 13 to 31 July, South Force had suffered almost 1,000 casualties, of which 260 had been incurred by the 112th Cavalry. For the understrength cavalry regiment, this was a casualty rate of over 17 percent. The 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, had also lost heavily and was in need of rest, reorganization, and re-equipment—needs which had prompted General Cunningham to change the places of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 127th Infantry. South Force casualties were as follows: 106 killed, 386 wounded, 18 missing, and 426 evacuated as a result of disease and sickness. South Force estimated that it had killed over 700 Japanese.4

Allied and Japanese Plans

General Cunningham planned to start a new attack on 1 August, with Company K, 127th Infantry, and Troop G, 112th Cavalry, moving southwest from the dropping ground in a reconnaissance in force to the Afua–Palauru trail. The two units were to probe for enemy defenses, avoid battle, and return to the dropping ground to report their findings before dark on the 1st. The entire 3rd Battalion and one cavalry troop were to be combined in a striking force for an attack into the triangle on 2 August, aiming for objectives selected during the previous day’s reconnaissance. Not even the preliminary steps of this plan could be executed. For days the Japanese had been bringing reinforcements forward to the Afua area to make further efforts to roll up South Force’s right flank, efforts which were to necessitate many changes in General Cunningham’s plans.

Despite continued lack of success in achieving decisive results at Afua, and though by the 25th of the month it had begun to appear to General Adachi that the 20th Division and Miyake Force could not secure even the Afua area, the 18th Army had not given up along the Driniumor. The 18th Army Commander had already devised a plan to send all elements of the 41st Division still east of the Driniumor across that river via the Kawanaka Shima crossing. This move was to entail operations by the 238th Infantry, the 239th Infantry, the 41st Engineer Regiment, the 41st Mountain Artillery Regiment, and the bulk of the 8th Independent Engineer Regiment, part of which was already west of the Driniumor with the 20th Division. Once across the Driniumor, the 41st Division units were to establish contact with the remnants of the 237th Infantry, send some men south toward the 20th Division to help cut American lines of communication, and mount new attacks on the Anamo–Tiver area.

On the afternoon of 25 July General Adachi himself moved up to the 41st Division’s command post (apparently located on Niumen Creek east of Kawanaka Shima) to supervise that unit’s preparations for attack. The 18th Army commander soon discovered that the 41st Division was in no condition to assault the center of the Driniumor line and, at the same time, he learned that the operations of the 20th Division in the Afua area were not going as well as had been expected. Considering how best to employ the 41st Division, he decided to send that unit south along the east bank of the Driniumor, have it cross the river south of Afua, join the 20th Division on the west side, and participate in a two-division attack to secure the Driniumor area from Afua north to the junction of the Anamo–Afua trail with the river.

Accordingly, on the morning of 26 July, General Adachi issued orders for the 41st Division to start moving south. The 1st Battalion, 239th Infantry, was left in the Kawanaka Shima area to set up a counterreconnaissance screen and to put up a show of strength designed to deceive the PERSECUTION Covering Force as to the intentions of the rest of the division. The remainder of the 239th Infantry, together with division headquarters, the 238th Infantry, and the engineer and artillery troops started south at 1600 on the 26th, aiming for a ford across the Driniumor south of Afua.

Final orders for the two-division attack west of the Driniumor were issued by the 18th Army on 28 July, orders which were based on expectations that the 41st Division

could complete its redeployment in time for the attack to begin on the evening of the 30th. This was too optimistic. The 238th Infantry, the 41st Mountain Artillery, and the 8th Independent Engineers were across the river in time but the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 239th Infantry, had missed the crossing point on the Driniumor and were lost. Fortunately for the 18th Army, the South Force withdrawals on 29 and 30 July gave the 20th and 41st Divisions time to complete their organization. New orders were issued for the attack to start on 1 August, with the 20th Division on the west and the 41st Division on the east. The strength that the 20th Division (including the 66th Infantry, the 26th Field Artillery, the bulk of the 37th Independent Engineers, the 20th Engineers, remnants of the 237th Infantry, and various small service units) could muster for the attack was a little over 2,000 men. Most of these troops had been without food for some time. They were suffering from starvation, malaria, and skin diseases, and morale was cracking. They were short of both ammunition and weapons. The 41st Division and its attached units, totaling nearly 1,750 men by the morning of 1 August, were in equally bad shape. Nevertheless, General Adachi was determined to make one last attack with the nearly 4,000 troops now available to him in the Afua area.5

The Japanese Retreat from Afua

At 0620 on 1 August, about two companies of Japanese attacked from the southwest against the lines of Troop C, 112th Cavalry, situated about 1,500 yards north of Afua. General Cunningham immediately canceled the planned reconnaissance in force into the triangle area and turned his attention to this new threat. The first Japanese assault units were quickly reinforced, and the enemy moved forward against Troop C in massed waves along a narrow front. A bloody battle ensued as the enemy, apparently determined to commit suicide, continued his mass attacks. South Force called for artillery support, which was quickly forthcoming and which greatly helped Troop C to throw back the enemy assaults.

By 0800 the Japanese had withdrawn and the battle area had become strangely quiet. Patrols were sent out from the cavalry perimeter to reconnoiter. These parties counted 180 dead Japanese in front of Troop C’s lines, and it was considered probable that the enemy had carried off many more dead and wounded. Troop C, on the other hand, had lost but 5 men killed and 6 wounded. Examination of the enemy dead disclosed that elements of both the 80th and 238th Infantry Regiments had participated in the attacks.

About 0830 Troop G moved southwest out of the Troop C area to undertake part of the planned reconnaissance in force. The troop patrolled 600 yards to the southwest and returned to Troop C early in the afternoon, having encountered only scattered rifle fire. Meanwhile, a platoon of Company K, 127th Infantry, had patrolled to high ground west of the dropping ground. Upon its return to South Force lines at 1600, this unit reported only minor opposition.

General Cunningham interpreted the lull in fighting after 0800 as an indication that the Japanese might be assembling stronger forces for another attack. Documents captured by Troop G and Company K patrols during the day supported this idea, and disclosed that the Japanese might launch an offensive during the night of 1–2 August or early on the 2nd. About 0300 on the 2nd, Troop G (which had moved to the southwest edge of the dropping ground the previous evening) was subjected to a small attack. This action turned out to be but a minor skirmish and General Cunningham suspected that it was a reconnaissance maneuver in preparation for a stronger attack. In anticipation of such an assault the remainder of the 2nd Squadron was removed from its river positions and disposed as a mobile reserve at the South Force’s command post. The 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, stretched its lines to cover the river positions vacated by the cavalry.

Although the movement of the 2nd Squadron had apparently been well advised, the Japanese did not attack the command post area. Instead, at 1900, elements of the 41st Division struck the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, at its lines south of the dropping ground. This attack was preceded by fire from a 70-mm. or 75-mm. artillery piece which the Japanese had managed to sneak into the area within 150 yards of Company B, 127th Infantry. Following a few rounds from this weapon, Japanese infantry charged forward in four separate waves, employing perhaps 300 men on a very narrow front. Few of the enemy got near Company B’s positions, for the attack was thrown back with artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire, which caused heavy losses among the enemy forces. By 2030, action in the dropping ground area stopped for the night.

The 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, on the left rear of the 1st Battalion, was attacked by another group of Japanese at 1945. This action was probably meant to have been coordinated with the attack on Company B, but, if this were the enemy’s intention, something had gone wrong. Apparently there had also been some mix-up in unit dispositions, for both enemy efforts had entailed the use of elements of the 78th, 80th, and 238th Infantry Regiments. After the day’s action was finished, the combined effective strength of the first two units was probably not more than 250 men, and the 2nd Battalion, 238th Infantry, was practically wiped out. The desperate attacks during the day had been carried out with a complete disregard for self-preservation, and had probably cost the Japanese 300 men killed and at least twice that number wounded.

During the early hours of the next morning, 3 August, the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, again heard enemy activity to its front, and about 0730 a small Japanese party struck between Companies A and C. This attack was quickly repulsed, principally by mortar fire from 1st Battalion units. By noon all activity in the 1st Battalion area had ceased, and the Japanese had withdrawn to the southwest. The rest of the day was quiet in the South Force sector. In the afternoon reinforcements arrived for South Force as the 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, moved into the perimeter from Palauru. The new arrivals took up defensive positions on the north flank, facing west behind the river lines of the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry.

The arrival of reinforcements did not result in any relaxation of vigilance on General Cunningham’s part, for he expected more enemy attacks. A great deal of Japanese movement across the Driniumor south of Afua had been observed by patrols during

the day, and recently captured prisoners reported that the 238th and 239th Infantry Regiments were to resume the offensive on 4 and 5 August. The South Force commander warned all his units to remain alert.

At 0615 on the 4th, elements of the 41st Division, probably supported by a few men from the 20th Division, streamed out of the jungle southwest of the 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, in a last desperate charge apparently designed to cover the withdrawal of other 18th Army remnants east of the Driniumor. The initial Japanese attacks were well coordinated but they soon degenerated into a series of small, independent, suicidal assaults. Violent action continued in front of the 1st Squadron for about two hours, during which time nearly 200 Japanese were killed at the very edge of the squadron perimeter, principally by machine gun and rifle fire. How many more of the enemy were killed by artillery and mortar fire during the period cannot be estimated, but the banzai tactics undoubtedly cost the Japanese more than the 200 dead counted in front of the 1st Squadron which, in the same two hours, lost only 3 men killed and 4 wounded.

By 0900 the last enemy attacks had ceased and the remaining Japanese had withdrawn generally to the south. Troop E, moving south across the front of the 1st Squadron in pursuit of the retreating enemy, encountered only scattered rifle fire and could find only nine enemy stragglers, all of whom they killed. In the afternoon other patrols of the 2nd Squadron, operating on the east bank of the Driniumor opposite Afua, established contact with elements of the 124th Infantry, which was completing a wide enveloping movement east of the Driniumor. On orders from Headquarters, PERSECUTION Covering Force, General Cunningham now began to plan final mopping up in the Afua area by coordinated operations of South Force and the 124th Infantry.

Envelopment to the East

Even before the Japanese had begun to withdraw from the Afua area, General Hall had prepared plans to carry out the final part of the mission assigned to him by ALAMO Force—a strong counteroffensive against the 18th Army.6 On 29 July, despite (or perhaps because of) the still unsettled situation around Afua, General Hall had decided that the time was ripe to launch the counterattack. For this purpose, he decided to employ the entire 124th Infantry, reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry. The 2nd Battalion, 124th Infantry, which had been patrolling in the Palauru–Chinapelli area, was relieved from that duty by the 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, and on the 30th joined its regiment at the Driniumor. The 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, was already at the river.7

South Along Niumen Creek

The plan of attack for the first phase of the counteroffensive was for the 124th Infantry, reinforced, to move directly east from the Driniumor beginning at 0800 on 31 July.8 This attack was to be carried out

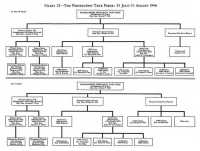

Chart 12: The PERSECUTION Task Force, 31 July–11 August 1944

with three battalions abreast along a front of 3,000 yards, and the fourth in reserve and in position to protect the right flank of the advancing force. The four battalions were to move east to the line of Niumen Creek, destroying all enemy found between that stream and the Driniumor within the 3,000-yard-wide zone of responsibility. Upon their arrival on the Niumen the battalions were to reorganize and prepare for further advances either east or south upon orders from General Hall.

Tactical control of the counteroffensive was vested in Col. Edward M. Starr, commanding officer of the 124th Infantry, whose counterattack organization was to be known as TED Force.9 The 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry, was commanded by Maj. Ralph D. Burns;10 the 2nd Battalion by Lt. Col. Robert M. Fowler; the 3rd Battalion by Lt. Col. George D. Williams; and the 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, by Maj. William F. Lewis. To avoid confusion, the four battalions were referred to by the last names of their commanders rather than by their number designations.

Fowler’s battalion, attacking along the coast, was to be supplied by ration trains moving along the coastal trail from Anamo. The rest of TED Force, pushing through trackless, dense jungle, was to be supplied by airdrop. The 149th Field Artillery Battalion, augmented by the Cannon Company, 124th Infantry, was responsible for artillery support, but when necessary the 129th Field Artillery was to add its fire to that of the 149th. All the artillery units were emplaced on the beach west of the Driniumor’s mouth. The positions which the 124th Infantry and the 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, left vacant on the Driniumor were to be occupied by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 128th Infantry.

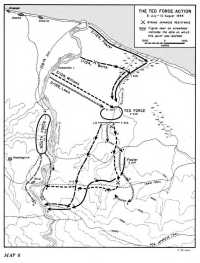

All three battalions of the 124th Infantry began crossing the Driniumor on schedule at 0800, 31 July, moving into terrain concerning which only incomplete and sometimes inaccurate information was available.11 (Map 8) As a result, the records of

TED Force are often inadequate and contradictory. Narrative reports and journals of the units engaged record many map and grid locations that are obviously erroneous and many others of doubtful value. It could hardly be otherwise. The available maps did not accurately depict the terrain and the two available sets, one a 1:20,000 photographic mosaic produced in May and the other a 1:63,360 terrain map dated in January, were mutually irreconcilable at many points. Again, the units involved did not maintain as complete records as they would have in more static situations, for they did not have the means or time to do so. Each battalion engaged operated more or less separately, communicating almost entirely by radio without sending written reports and overlays back to higher headquarters.

The situation in regard to locating units east of the Driniumor is well described by Maj. Edward A. Becker, the S-3 of the 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry, during the operation:–

We discovered, after leaving the Driniumor, that the only features that could be recognized on the map were the river, the coast line, and a trace of Niumen Creek; the rest of the operational area was just a mass of trees. . . . Because of this we knew we would have to find other means of identifying our location. We found the answer by using the two methods outlined below:–

(A) Twice a day the . . . [artillery liaison] plane would fly over our position and contact . . . [the artillery liaison officer]; he would let the pilot know when he was directly over us. The pilot would then fly to the Driniumor, turn around and fly directly E [east]; as he passed over us he would give us the distance from the R [river]. He would then repeat the procedure from the ocean by flying S [south]—the intersection of these lines would be our position.

(B) To check the above method (the whole area was dotted with artillery registrations which had been previously fired) the pilot would circle our position and get the concentration number from the [artillery] intersection towers located on the coast. He would then relay the number to us in this manner—200 yds E [yards east] of concentration 250 (we had these concentration No.’s [numbers] plotted on our maps). This again would be our position; if there was any appreciable difference in these two methods, then we would repeat the procedure until the error was found. . . .12

Determining which artillery units fired specific missions for TED Force also presents difficulties, inasmuch as the records of both the artillery and infantry units provide contradictory information concerning times and concentrations and because the infantry units did not keep complete records of requests for artillery fire. It would appear that the available maps were so inaccurate that only by a major miracle was TED Force saved from destruction by its own supporting artillery. Actually, however, the situation was not that bad. Most of the artillery fire was controlled quite accurately through the use of liaison planes. TED Force infantry units would fire a few rounds of mortar fire into the area where an artillery concentration was desired. The ubiquitous liaison planes would fly over the point and men in the observation towers on the coast, taking sights on the plane, would order fire on previously mapped concentrations. Necessary adjustments were made by radio through the liaison aircraft.

Such was the communications and mapping picture that faced TED Force as it

moved eastward from the Driniumor on 31 July. Colonel Fowler’s 2nd Battalion advanced along the beach, meeting no opposition. Shortly after 1200 the main body reached the most westerly of Niumen Creek’s two mouths—actually a swampy area about 3,000 yards east of the Driniumor. During the afternoon Fowler’s lines were extended almost 1,200 yards up the Niumen, but no trace of Burns’ 1st Battalion could be found. The latter unit’s advance company had been held up about 800 yards east of the Driniumor by elements of the 1st Battalion, 239th Infantry, which had been left along the river when the rest of that Japanese regiment had moved south to Afua on 26 July.13 Burns’ men continued to encounter strong opposition from 239th Infantry elements throughout the day and did not break off contact until 1730, when the battalion bivouacked for the night still 800 yards west of Niumen Creek. Company A had become separated during the day and remained some 550 yards northwest of the main body for the night. Both sections of the battalion were out of touch with the rest of TED Force.

The 3rd Battalion, 124th Infantry (Williams), crossed the Driniumor at a point about 3,000 yards inland and reached the Niumen about 1400, having encountered only scattered rifle fire. Lewis’ 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, which followed Williams’ command, made no contact with the enemy and bivouacked for the night about 500 yards west of Williams. All battalions spent the next day, 1 August, consolidating and patrolling along Neumen Creek, and Burns’ unit moved up into line with the others.

While this consolidation was going on, General Hall reached a decision as to further operations by TED Force. Since the intensity of Japanese attacks on South Force had not yet decreased, the task force commander directed TED Force to move south along Niumen Creek to the foothills of the Torricelli Mountains, nearly six miles inland. All Japanese encountered were to be destroyed and the east-west trails which the enemy was using to supply and reinforce his troops at Afua were to be cut. After reaching the hills, TED Force was to swing west toward a point on the Driniumor about 2,000 yards south of Afua. If the Japanese activity near Afua had not abated by the time TED Force reached the Driniumor, then the unit would cross the river, move northwest, and fall upon the rear of Japanese units harassing South Force.

Colonel Starr’s interpretation of the general mission and of the situation was as follows:–

To me, my first priority was to cut off the line of Japanese retreat, wherever it was, as well as the supply route of the enemy forces concentrating on Afua. Second priority was to destroy all enemy forces en route. Further based on my estimate of the situation and the enemy forces opposing me, as well as the terrain, I was convinced that any one of the four battalions under my control could take care of itself until support arrived if it became isolated or cut off. If properly handled this is a sound principle, of course, but considering the obstacles of terrain and weather, and the absence of a supply line and evacuation route, it was open to question.14

It was expected that movement south could start by 1100 on the 2nd, but supply difficulties and the amount of time the battalions consumed getting into position along the line of departure (a small western tributary

Map 8: The TED Force Action, 31 July–10 August 1944

of the Niumen about 3,000 yards east of the junction of the Anamo–Afua trail with the Driniumor) prevented the realization of these hopes. Instead, Burns’ and Fowler’s units slowly moved south through heavily jungled terrain to Williams’ perimeter. Colonel Starr moved his headquarters from the mouth of the Driniumor to Williams’ area, and supplies were laboriously carried inland from the coast or airdropped at Williams’ position. The night of 2–3 August proved quiet, and TED Force made final preparations to attack south at 0800 on 3 August.

The advance started on schedule, with Williams’ battalion on the left and Lewis’ on the right. Burns’ men followed Lewis’ while Fowler’s unit temporarily remained in reserve. Not more than 100 yards south of the line of departure both Williams’ and Lewis’ battalions encountered strong opposition from troops of the 239th Infantry. The Japanese, depending for the most part on well-concealed riflemen to delay the advance, maintained a tenacious defense throughout the day. Lewis’ battalion outflanked the Japanese in its zone and was able to advance about 900 yards by nightfall. Williams’ unit gained only 300 yards during the day and bivouacked about 500 yards to the left rear of Lewis’ battalion. Contact between the two was tenuous because of enemy patrol action and the jungled terrain. Just before dark both battalions dropped slightly back from their most advanced positions in order to allow supporting artillery to place fire on the still resisting enemy.

Before noon Colonel Starr realized that Williams’ and Lewis’ battalions were probably not going to break through the Japanese opposition on 3 August. Ordering them to continue their fights, he instructed Burns’ command to bypass the engagement and strike overland on an azimuth of 195 degrees (roughly, south-southwest). By dusk Burns’ command had advanced unopposed 900–1,000 yards and dug in for the night nearly abreast but 400 yards west of Lewis’ battalion and out of contact with it. Fowler’s unit bivouacked for the night at the line of departure, protecting the dropping ground, which was vital to continued advance since TED Force could by now be supplied only from the air. Casualties during the day had been incurred only by Williams’ and Lewis’ units and totaled 14 men killed and 14 wounded.

During the night strong artillery concentrations were placed in front of Williams and Lewis and at 0800 on 4 August both resumed the advance. The terrain encountered on 4 August and subsequent days during the operations of the TED Force east of the Driniumor proved next to impassable. Dense jungle undergrowth covered the ground; the area was thick with heavy rain forest; low but knifelike ridges, separated from each other by deep gullies, were encountered; and swampy spots were plentiful. To add to the difficulties, rain fell during the day—a downpour which turned much of the ground into a quagmire and flooded many dry stream beds. A few new, rough trails, recently cut by the Japanese, were found, but mud made them nearly useless as routes of advance. Low clouds coming in from the Torricelli Mountains to the south prevented ration and ammunition drops and increased communication difficulties. Battalions ran low on drinking water, for weather conditions prevented resupply of water purification tablets and the assault companies had neither time nor equipment to clean water by other means. Radio communication between battalions, from battalions to TED Force headquarters, and

from the latter to higher echelons was nearly nonexistent, for the heavy jungle and the damp weather cut down the efficiency of all radio equipment.

First contact on 4 August was made by Williams’ men, who surprised a platoon of Japanese in bivouac scarcely 100 yards south of the line of departure. Eight Japanese were killed and the rest fled. Williams’ and Lewis’ battalions then continued southward against only scattered rifle fire. The units covered about 1,000 yards in a southerly direction during the day and bivouacked on a clearly defined east-west trail. Fowler’s battalion was not committed during the day, but remained in reserve at the dropping ground with the regimental command post.

On the west, Burns’ battalion had moved southwestward away from the rest of Force. The unit encountered no opposition but found itself in such a maze of steep ridges and deep gullies that the pace of advance was slowed to little more than 100 yards per hour. After marching over ten hours and covering over 1,000 yards, the battalion set up night defenses on the same trail upon which Williams’ and Lewis’ commands had bivouacked about 1,300 yards to the east-northeast. Casualties for all parts of TED Force had been light on the 4th. Only 8 men had been wounded as opposed to about 50 Japanese killed and 3 captured.15

It had been hoped that the advance on the 4th would carry TED Force south to the main Japanese supply route, but the trail reached by Burns’, Lewis’, and Williams’ battalions was another route which had not been used by military traffic for some time. Possibly, it was a section of the native trail to Afua and, as such, purposely avoided by the Japanese inasmuch as parts of it could be seen from the air. In any case, the track cut on the 4th lay about 1,200 yards north of the east-west trail which most of the Japanese forces moving to and from the Afua area had been using. Colonel Starr, realizing that the main Japanese supply route had not yet been severed, ordered his units to continue southward on the 5th, on which day the advance was resumed about 0800 hours with Williams leading and Lewis’ battalion about 400 yards to the rear. Pushing south along now precipitous and mountainous banks of the upper Niumen, Williams’ unit was opposed by only scattered rifle fire until 1100, when it was decisively halted by a strong Japanese force conducting a stubborn defense.

TED Force and the Withdrawing 18th Army

Unknown to any part of the PERSECUTION Task Force, the 18th Army had been seriously considering withdrawal from the Driniumor since at least as early as 28 July. Supplies for 18th Army units in the Afua area were nearly exhausted, and General Adachi estimated that every last crumb of food would be gone by 3 August. No more supplies could be brought forward. Moreover, the front-line units were suffering increasingly heavy casualties from combat, starvation, and disease; they had no more artillery support and could obtain none; weapons of all kinds were either being destroyed or rendered useless by lack of lubrication oil; and no reinforcements were available.

Disturbed by the heavy casualties and plagued by insoluble logistic problems, General Adachi, on the afternoon of 31 July, issued orders alerting his forward units to

prepare for withdrawal, which apparently was to begin on 4 August. The assaults on South Force after 31 July were actually a part of General Adachi’s withdrawal plan, which was designed to throw the PERSECUTION Covering Force off balance, to put forth one last “glorious” effort to overrun American positions (and perhaps secure supplies), and to cover the withdrawal.

On 1 August General Adachi learned that American forces were active in the Yakamul area. It was erroneously reported to him that this was an amphibious operation, a maneuver which the 18th Army commander had feared for some time (actually, the report referred to patrolling by the 2nd Battalion, 124th Infantry, along the coast from the mouth of Niumen Creek). He therefore ordered the remaining elements of the 237th Infantry to extricate themselves from the operations in the Afua area and hurry back to Yakamul to reinforce service units in that vicinity. Events moved so rapidly that the remnants of the 237th Infantry never got to Yakamul. Instead, the advance of TED Force made it necessary for General Adachi to change his plans and accelerate a general withdrawal.

Communications within forward units of the 18th Army had so broken down that it was not until 3 August that General Adachi learned of the TED Force movement across the Driniumor, although the 1st Battalion, 239th Infantry, had been in contact with TED Force since 31 July. When General Adachi did hear of the American movement, he grossly underestimated the strength of TED Force. Thinking that the American operation was being carried out by only 400 troops, General Adachi merely changed the orders of the 237th Infantry and instructed that regiment to hold the 18th Army’s crossing point on the upper Niumen Creek.

On the same day, 3 August, General Adachi issued detailed plans for the withdrawal of all 18th Army units to the east side of the Driniumor, a withdrawal which was to begin on 4 or 5 August. The 66th Infantry, 51st Division, was to protect the 20th and 41st Division units as they crossed the Driniumor. The continued advance of TED Force on 3 August prompted General Adachi to change his plans and early on the 4th he ordered the 20th Division to start retreating at noon that day and the 41st Division to break contact on the 5th. On the latter day, learning that TED Force was approaching the point at which the 18th Army’s main line of communications crossed the upper reaches of Niumen Creek, General Adachi ordered the 8th Independent Engineers to aid the remnants of the 237th Infantry in holding the crossing point.

It was this combined 237th Infantry–8th Engineers force that Williams’ 3rd Battalion, 124th Infantry, had encountered about 1100 on 5 August. The composite Japanese unit was dug in along a 1,000-foot high ridge across Williams’ line of advance and threatened to outflank the battalion by occupying other high ground nearby. Despite artillery and mortar support, Williams’ men were unable to advance. Colonel Starr ordered Lewis’ unit to bypass the fight and continue south to locate and cut the Japanese main supply route. Fighting at Williams’ front continued through most of the afternoon, and Colonel Starr realized that the Japanese force could not be dislodged that day. Fowlers’ battalion was brought up to the rear of Williams’ and late in the afternoon set up a new perimeter with the regimental command post. Before dark,

Williams’ men withdrew slightly from their most forward positions so that artillery concentrations could be placed along the front.

Lewis’ unit, which had moved off to the southeast to bypass Williams’ fight, made little progress in very rough terrain and was cut off from the rest of TED Force before it could swing westward. Burns’ battalion, still far to the west of the other three, had encountered little opposition during the day and had reached the main Japanese supply route late in the afternoon at a point about 1,500 yards east of the Driniumor. The position of Lewis’ unit for the night is not certain, but it was apparently near the same trail some place east of Williams’ unit, which had done its fighting on or near one section of the main trail.

Despite the fact that hopes of reaching the Driniumor had not been realized, the Force advance on the 5th had been successful within the limitations imposed by terrain, logistic problems, communications difficulties, and Japanese opposition. The main Japanese line of communications had been severed, although the section held by Burns’ battalion showed signs of having been abandoned for some time. Over 100 Japanese had been killed at a cost to TED Force of only 3 men killed and 14 wounded. Plans for the 6th were for Lewis’ battalion to continue its flanking movement while Fowler’s unit, bypassing Williams’ fight, was to envelop the Japanese left. Williams’ men were to continue their attack and Burns’ battalion was to hold its position astride the trail.

Action on the 6th started earlier than TED Force expected. About 0300 approximately 400 Japanese attacked Williams’ perimeter. This enemy force comprised elements of the 41st Division, supported by men of the 26th Field Artillery of the 20th Division and some remnants of the 8th Independent Engineers. Attacking under cover of fire from machine guns, mortars, and 75-mm. mountain guns, the Japanese force was attempting to secure fords over the upper reaches of Niumen Creek and protect the withdrawal of other elements of 18th Army units from Afua. Though surprised, Williams’ men held back the initial onslaught. Reportedly, Japanese riflemen then climbed trees surrounding Williams’ perimeter to pin down the American troops while other Japanese continued to attack on the ground.

Fowler’s unit, under orders to bypass Williams’ fight and move around the enemy left, started moving about 0800 hours but soon found the terrain made it impossible to avoid contact with the Japanese opposing Williams. The Japanese, having control of most commanding ground in the area, stopped Fowler’s leading company. Action was not rapid. The terrain made all movements slow and laborious, and much time had to be taken to coordinate artillery support fire properly. Under cover of artillery fire, another company of Fowler’s battalion, creeping slowly through ravines and up an almost vertical cliff, worked around to unoccupied high ground on the Japanese left. The rest of the battalion was successfully disengaged to secure more commanding terrain in the same area. The Japanese, finding themselves outflanked and subjected to increasingly heavy artillery and mortar fire, began to withdraw southward in mid-afternoon, relieving the pressure on Williams’ front.

Fowler’s battalion, in enveloping the Japanese left, had moved north and then westward and the maneuver had carried the unit by dark to a point just north of the main trail about 750 yards east of Burns’ battalion. Williams’ men withdrew to reorganize, after disengaging from the enemy

Artillery supporting TED Force. C Battery, 129th Field Artillery Battalion, firing from the coast near Anamo

forces late in the afternoon; at dark, having resumed the march westward, they secured high ground north of the trail. The ground covered during the day by Williams’ battalion was little more than 500 yards west of the position it had occupied the previous night. The unit probably could have moved farther, but Colonel Starr halted it so as not to increase the distance from Lewis’ battalion which was, in effect, lost. The unit had laboriously struggled over extremely rough and trackless ground during the day, fighting in the afternoon against a number of Japanese who had withdrawn from Williams’ front. For the night, Lewis’ men set up a perimeter about 800 yards south-southeast of the scene of Williams’ fighting.

Burns’ men, patrolling from their perimeter astride the main trail, discovered a new trail about 800 yards to the south. The Japanese, having abandoned the western section of the trail on which Burns’ battalion was bivouacked, had recently cut the new trail in order to escape from artillery and aerial bombardment, and had been using this new trail since late July. Plans were made to send a strong force south to cut the new route, but Major Burns decided to have

artillery interdict the Japanese who had been discovered by patrols on the new trail. Artillery fired throughout the night while Burns’ battalion prepared to move in force south to the new trail the next morning.

TED Force action on the 6th probably accounted for some 350 Japanese killed or wounded,16 while the TED Force battalions lost only 11 men killed and 2 wounded. Again, the advance had not carried to the Driniumor although General Gill, at PERSECUTION Covering Force headquarters, had been pressing Colonel Starr to move on to the river. But Colonel Starr, not sure that all the principal Japanese escape routes had been cut, asked that he be allowed to continue advancing southward, ultimately to approach Afua from the southeast. This plan was approved by General Gill. Plans were made to push on to the Driniumor on the 7th—plans which again could not be carried out.

On the 7th movement began at 0800, and Burns’ unit pushed rapidly south toward the new trail. Fowler’s command, initially moving west along the main trail, encountered some stiff opposition from Japanese who were attempting to escape from Burns’ men. Fowler’s battalion turned south and southwest from the main trail and, advancing at a fairly good speed over very rough terrain, joined Burns’ unit on the new trail about 1130. By noon the two battalions had killed over 75 Japanese. Pushing generally westward toward Afua and moving the bulk of the battalion to high ground south of the new trail, Burns’ unit bivouacked for the night still about 1,100 yards east of the Driniumor, and Fowler’s men were in the same general area.

Williams’ unit, with regimental headquarters, pushed laboriously westward and by nightfall, having met little opposition, bivouacked on the main trail at a point almost due north of Burns’ and Fowler’s new positions. Lewis’ progress was again painfully slow over the incredibly rough terrain in which the unit found itself. There was some opposition from 41st Division remnants, and Lewis’ movement was also slowed by the necessity for carrying along thirteen wounded men on litters. By dark the battalion had progressed scarcely 500 yards in a westerly direction and was still south of the main trail. Casualties in TED Force from enemy action were light on the 7th: only 1 man killed and 3 wounded. Faulty mortar ammunition, however, killed 8 more men and wounded 14 others, and early the next morning misplaced artillery fire from the 120th Field Artillery Battalion killed 4 men and wounded 22 others in Burns’ unit.17

On the 8th, Burns’ and Fowler’s battalions pushed on to the Driniumor, reaching the river at a point about 1,000 yards south of Afua. On the way, Burns’ men discovered a Japanese hospital area. Most of the Japanese there indicated no willingness to surrender but, on the contrary, began to commit suicide or fire at the advancing American troops, who summarily dispensed with those Japanese failing to commit suicide.18 Williams’ unit reached the Driniumor at 1700, but Lewis’ battalion, which had reached the main trail during the morning, was again delayed by scattered Japanese opposition. and the necessity of carrying

wounded men. The battalion remained more or less lost until 1100 on 10 August, when it reached the Driniumor at a point about 300 yards north of Afua. The same day all of TED Force moved back to the BLUE Beach area for a well-deserved rest.

Results of TED Force Operations

TED Force reported that during its wide envelopment maneuver it killed about 1,800 Japanese. Most of these casualties TED Force inflicted upon the 18th Army while the four American battalions were moving westward toward the Driniumor, and many included the sick, wounded, hungry, exhausted, and dispirited Japanese troops who were unable to keep up with the rest of the retreating 18th Army. Combat losses within TED Force were about 50 men killed and 80 wounded, of whom about 15 were killed and perhaps 40 wounded by misplaced American artillery fire or faulty mortar ammunition.19 How many TED Force men were rendered hors de combat by tropical fevers, psychoses, and other ailments is unknown, although it is known that all four battalions lost some men from such causes.

The relatively low battle casualty rate (little more than 2 percent from enemy action), while indicative of the ineffectiveness of Japanese opposition, is also a tribute to the leadership within TED Force and to the teamwork of all ranks under the worst possible climatic and terrain conditions. It is especially noteworthy that the bulk of the personnel engaged in the enveloping maneuver were members of the 124th Infantry, a unit on its first combat mission, and that the 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, had been extensively reorganized and had received many inexperienced replacements since its last action against the Japanese.

To summarize, the objectives of the Force maneuver had been to cut the Japanese lines of communication to the east in order to render the enemy’s positions around Afua untenable, and, if necessary, to fall upon the 18th Army’s Afua forces from the flanks and rear. While the envelopment was not as successful in accomplishing these missions as had been anticipated, or as it was thought to be at the time of its completion, the maneuver did force the 18th Army to accelerate its already planned withdrawal from the Driniumor.

The End of the Aitape Operation

While TED Force had been moving toward the Driniumor, South Force had been mopping up in the Afua area. The banzai attacks against the front of the 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, on the morning of 4 August had been undertaken by the 18th Army to cover the withdrawal east of the Driniumor and marked the last coordinated efforts made by the Japanese in the Driniumor area. General Cunningham could now execute his plans to clear the enemy remnants from the Afua region.

A combined attack by TED Force and South Force had originally been scheduled for 4 August, but had been postponed because TED Force could not reach the Driniumor by that day.20 On 5 August it was decided that South Force would attack south

Native litter bearers evacuate a casualty across the Driniumor River near Afua Village

the next day, whether or not TED Force reached Afua in time to participate. It was in preparation for this attack that the 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, had been sent to the Driniumor from Palauru, and at the same time General Gill released the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, to General Cunningham for participation in the 6 August action.

The South Force commander ordered three of the infantry battalions available to him to clear the ground south and west of his command post area to the Afua–Palauru trail. One of the battalions was to move south along the west bank of the Driniumor, clear Afua, and then move on to a Japanese fording point about 2,000 yards upstream from Afua. Simultaneously, on the east bank, a Composite Squadron, comprising two cavalry troops and an infantry company, was to advance south to the ford. Tactical control over all these attack operations was vested in Colonel Howe, the commander of the 127th Infantry.

The Composite Squadron crossed the Driniumor at 0800 on the 6th and pushed south through heavy but disorganized Japanese rifle fire. It halted for the night about 500 yards north of the ford and reported that many Japanese were crossing the ford to the east. West of the river, one infantry battalion reached the Afua–Palauru trail late in the afternoon at a point about 300 yards west of Afua, having encountered only scattered resistance. Another battalion pushed units south along the west bank to a point opposite the Composite Squadron, and the third continued operations it had begun on the 5th of August to clear the jungled, broken terrain west of South Force’s command post.

Patrolling in the same areas continued for the next two days, as South Force waited for TED Force to reach the Driniumor. South Force patrols reported ever decreasing opposition and found increasing evidence that the Japanese were in full flight to the east. On the evening of 9 August General Gill reported to General Hall that no more resistance was to be expected along the Driniumor or in the Afua area. The Japanese, said General Gill, had retreated and the PERSECUTION Covering Force could be relieved. The Battle of the Driniumor was over.

On 10 and 11 August most of South Force and all of TED Force returned to BLUE Beach and on the latter day the 103rd Infantry, 43rd Division, began to relieve all units of the PERSECUTION Covering Force still on the river. The relief of the 127th Infantry was completed on the 13th, and the 128th Infantry, which was still holding the old North Force positions, returned to BLUE Beach three days later. The PERSECUTION Covering Force ceased to exist as a separate unit on the 15th and its missions were assumed by a new organization which, designated the Tadji Defense Perimeter and Covering Force, was commanded by Maj. Gen. Leonard F. Wing, the commanding general of the 43rd Infantry Division.21

From 16 to 25 August principal combat missions in the Aitape area were carried out by the three regiments of the 43rd Division. The 169th Infantry operated on the west flank, the 172nd Infantry south of the Tadji strips and along the Nigia, and the 103rd

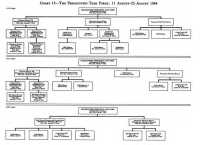

Chart 13: The PERSECUTION Task Force, 11 August–25 August 1944

Infantry along the Driniumor. The latter regiment sent patrols east from the Driniumor along the coast as far as Marubian, and up the Drindaria River to Charov and Jalup, where no American troops had been since early June. As far east as the Drindaria there was no sign of organized Japanese resistance, and all Japanese in the area seemed to be withdrawing in confusion to the east. At the mouth of the Dandriwad River, however, the Japanese maintained organized delaying positions, through which American patrols did not attempt to push.22

On 25 August General Krueger, ALAMO Force commander, convinced that the 18th Army no longer constituted any threat to the Aitape perimeter or the Tadji airstrips, declared the Aitape operation over.23

Conclusions

The most obvious result of the Aitape operation was that two and one-third reinforced divisions of the 18th Army had been shattered in vain attempts to recapture the Aitape area and delay the Allied drive toward the Philippines—neither of which objectives had been achieved. Instead, the 18th Army had suffered a decisive and costly defeat; it could no longer be a serious threat to Allied forces anywhere in New Guinea.

The Aitape operation had served a number of other purposes for the Allies. First, the Tadji airstrips had provided a base from which planes could have flown support missions for ground operations at Hollandia, had such support proved necessary. Second, the PERSECUTION Task Force’s victory over the 18th Army prevented the latter unit from threatening more important Allied positions at Hollandia. At Aitape, one regimental combat team of the 31st Infantry Division received its first combat experience, and the whole or parts of three other divisions and all of another regimental combat team had further experience in combat which helped prepare those units for subsequent operations in the drive toward the Philippines or in the latter islands themselves. Finally, the Aitape area served as a staging base for troops engaged in three later operations along the New Guinea coast and in the Philippines.

Securing the Aitape area and defeating the 18th Army had cost Allied forces to 25 August approximately 440 men killed, 2,550 wounded, and 10 missing.24 According to American counts, Japanese losses in the Aitape area from 22 April to 25 August were 8,821 killed and 98 captured, of whom 2,669 were killed and 34 taken prisoner during

the period 2–9 August.25 According to Japanese sources, the American figures are a little conservative, for the Japanese estimated that the 18th Army lost about 9,000 men of the 20,000 employed in the forward area just for the period 1 June through 5 August. As the 18th Army units withdrew, effective combat strength of the 20th Division’s three infantry regiments was down to an average of less than 100 men; the regiments of the 41st Division averaged about 250 men; and the 66th Infantry, 51st Division, was reduced to 150 effectives. All Japanese infantry units lost most of their battalion, company, and platoon commanders, and the bulk of their crew-served weapons. All the artillery brought to the Aitape area was lost, and rations and supplies of all other types were completely exhausted in the forward area.26 The sacrifices were in vain.

Although a major battle—essentially defensive in character—had developed at Aitape, this action proved but incidental to the progress of the Southwest Pacific Area’s drive toward the Philippines. Even while the battle along the Driniumor was being fought, other forces under General MacArthur’s command had been moving northwestward up the coast of New Guinea. This drive had progressed as rapidly as the assembly of supplies and the availability of ground forces, air support, amphibious craft, warships, and cargo ships would permit. On 17 May, long before anyone at Aitape knew that the 18th Army was going to attack or that a battle was going to be fought along the Driniumor River, Allied forces had landed in the Wakde–Sarmi area of Dutch New Guinea, about 275 miles northwest of Aitape.27