Chapter 8: The Attack of 19 April on the Shuri Defenses

Under a bright warm sun on the afternoon of 18 April, infantrymen of the 27th Division in their bivouac area north of Uchitomari inspected their weapons and struggled with their belts, harness, and bandoleers. At 1500 they began to stroll off toward Uchitomari in long, halting lines. At 1540 several men, without jackets or helmets, picked up a machine gun on O’Hara’s Knob, north of Machinato Inlet, and sauntered over to the north edge of the inlet, where they set up the weapon. There was little stir or bustle. Small groups of soldiers moved here and there, settling down at various spots to look across the inlet and wait.1

Such was the opening move in an action that was soon to swell into a heavy attack across the entire Corps front. This seemingly random movement was carefully planned. The 27th was going into position to launch a surprise penetration of the enemy’s west flank as a preliminary to the attack of the whole XXIV Corps on 19 April. For more than a week the Corps had been making feverish preparations for this attack, in the hope that one powerful assault by three divisions abreast might smash through the Shuri defenses.

Plans and Preparations

American Plan of Attack

General Hodge’s plan was to break through the enemy’s intricate defense system around Shuri and to seize the low valley and highway extending across the island between Yonabaru and Naha. He ordered the 7th Division on the east to take Hill 178, then to press south to that section of the Naha–Yonabaru road in its zone. The 96th Division, less the 383rd Infantry, in Corps reserve, was to drive straight through the heart of the Shuri defenses, seizing the town of Shuri as far as the highway beyond. For these two divisions H Hour would be 0640, 19 April. The 27th was to attack at H plus 50 minutes from positions taken

during the previous night; its mission was to seize Kakazu Ridge, the western portion of the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, and the. hilly country and coastal plain beyond to the Naha–Yonabaru highway. The 27th Division’s delayed entrance was to allow for progressive massing of artillery fire from east to west along the line as the attack developed2 (See Map 23.)

Perhaps the most striking element of the plan was its provision for a tremendous artillery preparation beginning 40 minutes before the assault groups moved out. Twenty-seven battalions of artillery, nine of them Marine, were to be prepared to mass fire on any section of the front. After 20 minutes of pounding the enemy’s front lines, artillery would lift its fire and hit his rear areas for 10 minutes, in an effort to induce the Japanese to emerge from their underground positions; then the shelling would shift back to the enemy’s front lines for the 10 minutes remaining until H Hour. This procedure was to be repeated for the attack of the 27th Division. During the preparation, aircraft and naval guns were to pound the Japanese rear areas. Rockets and 1,000-pound bombs were to be directed against the headquarters installations in Shuri. A landing force, covered by planes and naval guns and embarked in transports, was to feint a landing on beaches along the southeastern coast of southern Okinawa.

General Hodge viewed the prospect with high hopes, mingled with grim appreciation of the difficulties ahead. “It is going to be really tough,” he said two days before the attack; “there are 65,000 to 70,000 fighting Japs holed up in the south end of the island, and I see no way to get them out except blast them out yard by yard.” He saw no immediate possibility of large-scale maneuvers, but he did foresee opportunity for “small maneuver thrusts within the divisions,” and possibly later within the Corps if the Americans broke through the Shuri fortified zone.3

Terrain Features

Terrain which became increasingly formidable confronted each of the three divisions. In front of the 27th lay Machinato Inlet on the right; a low flat area covered with rice paddies and dissected by streams, later called “Buzz Bomb Bowl,” in the center; and the Kakazu hill mass and town on the left. The 96th faced several inconspicuous but strongly defended hills, such as Tombstone and Nishibaru Ridges, as well as the bold face of Tanabaru Escarpment. The 7th Division was confronted by the stout defenses of Hill 178 and the town of Ouki, which had brought it to a full stop.

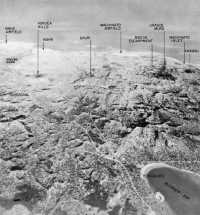

Strategic area of southern Okinawa seen from an altitude of 7,500 feet

These terrain features were merely points of the initial barrier; beyond them lay even stronger obstacles. The most prominent of these was the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, which stretched across the 27th Division’s front and most of the way across that of the 96th. The escarpment rose from the East China Sea in a jagged coral spine that steadily gained height as it extended southeastward. At its highest point, near the center of the island, Urasoe–Mura jutted upward 215 feet from the jumbled ground at its base. From this point, called Hill 196, and from most of the escarpment itself, the enemy had excellent observation in all directions. Although the escarpment came to an abrupt end near the center of the island, Japanese defenses in the rough ground around Kochi, Onaga, and Unaha extended almost to Buckner Bay. Behind this line lay the inner Shuri defenses. The core of the Japanese defensive system on Okinawa, this ground was utterly without pattern; it was a confusion of little mesa-like hilltops, deep draws, rounded clay hills, gentle, green valleys, bare and ragged coral ridges, lumpy mounds of earth, narrow ravines, and sloping finger ridges extending downward from the higher hill masses.4

American Preparations

There was virtually no change in the lines from 14 to 19 April. Patrols probed the enemy’s defenses; artillery, naval guns, and aircraft searched out and destroyed enemy mortars, artillery pieces, and installations. Ground and air observers studied the ground in front of XXIV Corps and pinpointed caves, trenches, supply points, and emplacements which were to be demolished during the artillery preparation on the 19th.

Behind the lines there was unceasing activity. General Hodge had remarked that the attack would be “90 percent logistics and 10 percent fighting”;5 the truth of this observation was borne out by the intensified activity along the beaches, the continuous bulldozing of the main supply routes, and the long lines of trucks and DUKW’s laden with ammunition and supplies rolling toward the front night and day. Among the array of weapons poised for the attack were armored flame throwers, which were to be used for the first time on Okinawa in the attack of 19 April.

Fresh troops also were brought in. The 27th Division, previously in floating reserve, had landed at the Hagushi beaches on 9 April to serve as reinforcements

Ouki Hill-Skyline area on the east coast, which was attacked 19 April (photographed 10 July 1945)

Machinato Inlet, seen shortly after the action of 19 April. Three Weasels on the road (left) were knocked out. In background (left) Buzz Bomb Bowl slopes up to Urasoe–Mura Escarpment

in the attack. It was assigned to XXIV Corps and proceeded to relieve the 96th Division in the western part of its zone. By 15 April the 27th was in position. The attack was further reinforced by about 1,200 replacements sent in to the 7th and 96th Divisions. Processed and equipped in Saipan, the new arrivals had been dispatched through the replacement battalion on Okinawa in a few hours. They were uniformly young and healthy, and mentally above average. Their arrival heightened the morale of the men in the infantry companies, but XXIV Corps still remained understrength for the heavy fighting ahead.6

Japanese Preparations

The Japanese were not idle. A 62nd Division order on 14 April warned of the attack: “The enemy is now preparing to advance on all fronts. Our front lines will necessarily be subjected to fierce bombardments.” Unit commanders were ordered to strengthen positions. Strong points were to be so distributed that the loss of one point would not mean the break-up of the whole line. Units were to “secure their weapons by placing them under cover or in a position of readiness, so that they will not be prematurely destroyed.” The enemy evidently anticipated the necessity of withdrawing, however, for he ordered secret documents to be burned “as the situation becomes untenable.”7

During the lull before the attack, the enemy redoubled his attempts to teach his troops the proper defense against American tactics and weapons. The 44th Independent Mixed Brigade on 13 April issued a “battle lesson-urgent report” describing defenses against American flame-throwing tanks and “yellow phosphorus incendiary shells.” The 22nd Regiment on 15 April described American night defensive positions and how to infiltrate through them. The 32nd Army emphasized the importance of careful selection of points from which to make close-quarters attacks on American tanks.8

Admitting that American fire power was their main concern, the Japanese paid special attention to their underground defenses. Units were cautioned to build reserve positions into which troops could move quickly from caves under attack. Simple rules were issued on 15 April for protecting the health and morale of Japanese troops in caves undergoing severe bombardment:–

Spiritual training within the cave must be intensified. ... Useless work should be avoided; whenever there is free time, get as much sleep as possible. ... Have the men go outside the cave at night at least once or twice and perform deep breathing and physical

exercises. ... Latrines should be built inside and outside the caves and, above all, kept clean. ... Take precautions against diarrhea and epidemic diseases resulting from drinking water which has been left untreated because of the inconvenience of having fire.9

Preliminary Attack of the 27th Division, 18 April

The 27th Division, on the right of the Corps line, was faced by a situation that called for the utmost ingenuity if it were to succeed in its assignment of a preliminary surprise attack. Holding the sector on the northern side of Machinato Inlet, this division, and particularly the 206th Infantry on the extreme right, was wholly under the observation of the enemy on the other side of the inlet. Any movement by the Americans, or even preparation for movement, could be clearly observed from the Japanese positions on a bluff overlooking the inlet and on the escarpment about a mile farther back. The success of any attack depended on its being prepared and executed in complete secrecy from the enemy.

Plan of Attack

A captured Japanese document gave Maj. Gen. George W. Griner, Jr., commander of the 27th, an idea for the tactics to employ. This document, issued by the 62nd Division, informed the Japanese troops that “the enemy generally fires during the night, but very seldom takes offensive action.” A copy of the translation reached 27th Division headquarters as the plans for the attack were being laid, and impelled the division staff to decide on a night attack to surprise the enemy. The 27th had trained in night maneuvers shortly before embarking for Okinawa. Moreover, the terrain in front of the division made a night attack most desirable. More than 1,000 yards of open ground lay between its .front lines in the Uchitomari area and the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, which was an initial objective of the 27th. An attack during daylight across this ground, obstructed as it was by Machinato Inlet on the west, rice paddies and streams in the center, and rough ground on the division’s left (east), would enable the enemy to exploit his complete observation of the area and to bring in prearranged fires on the exposed troops. A night attack would avoid this peril and might catch the enemy napping.10

General Griner’s plan also took advantage of the fact that the Machinato area was not held in strength by the enemy but merely outposted. Accordingly, the 106th Infantry on the right (west) was to cross Machinato Inlet, advance

under cover of darkness during the night of 18-19 April toward the escarpment, and by daylight reach Urasoe–Mura where Route 1 cuts through it; then the assault troops were to push down the escarpment to the southeast and seize the vital high ground in its sector. On the division’s left (east), the 105th Infantry was to undertake an entirely different type of attack – a powerful daylight push, lacking deception or maneuver, designed to obliterate Japanese opposition by main force. The 205th was to attack from its positions before Kakazu on the morning of the 19th, clean out the town of Kakazu, and advance straight ahead to gain the crest of Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, where the regiment would hook up with the 106th on its right (west). “Nothing must be allowed to stop the forward movement,” General Griner ordered.11

Mounting the Attack

The mounting of the attack furnished a ticklish engineering problem, which was complicated by the need for secrecy. Four bridges at Machinato Inlet were to be built during the night of 18-19 April--a footbridge for the assault troops to move across during the night, two Bailey bridges, totaling ninety feet, for supporting weapons, and a rubber ponton bridge strong enough to carry ½-ton trucks loaded with supplies. Erecting these bridges in the dark would be difficult enough, but, to make matters worse, the 102nd Engineer Combat Battalion, the division engineers, had had no experience with the Bailey bridge. The division had left the United States before the adoption of this type of structure and had fought on small islands where large spans were not required. Fortunately, an officer who had helped construct several Baileys in Tunisia, 1st Lt. Irving S. Golden, had recently joined the division. Under his direction the engineers spent several days building, tearing down, and rebuilding Bailey bridges in a division rear area.

Secrecy was vitally important, but very difficult to maintain because of the excellent enemy observation and the intense activity necessary for the attack. The appearance of stock piles of bridge equipment near Machinato Inlet would alert the Japanese to the plan of crossing the inlet in strength. Consequently the 202nd Engineers assembled its equipment in rear areas in readiness for instant transportation. Pontons were inflated, and bridge sections were assembled to the maximum size that trucks could carry.

Another piece of deception was also executed cunningly. The route leading to the proposed ponton bridges was a shell-pocked, deeply rutted little jeep road

which ran by O’Hara’s Knob and ended in a rice paddy 250 yards short of the objective, the northeast edge of the inlet. The road had to be made ready to carry the traffic of trucks loaded with bridge equipment, but attempts to improve it might arouse Japanese suspicions. During daylight hours in the period before the attack a bulldozer puttered about on this road, in plain view of the enemy. When an occasional jeep became bogged down, the bulldozer chugged over to extricate the vehicle, remaining to push dirt and rocks into the ruts. The operator alternately slept, tinkered with the engine, and expressed his annoyance with sweeping gestures when still another jeep became bogged down. But at night he worked feverishly. By 18 April the road had been extended and improved and reached almost to the edge of the inlet, although it would have been difficult for an observer to estimate just what had been done to the road and when.

As the time for the attack approached, the plans took final form. General Griner hoped for a break-through and insisted that “no matter what else happens, we must advance. We do not have time to wait for units on our flanks. If they cannot move, we will push forward anyway. I do not want to hear any unit commander calling me and telling me that he cannot advance because the unit on his flank cannot advance.”12 Maj. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold, Commanding General of the 7th Division, and Maj. Gen. James L. Bradley, commanding the 96th, also instructed their commanders to push their attacks “vigorously and rapidly,” even though casualties became severe and logistical problems resulted. They believed that by this means an early success could be ensured and an extended and costly battle avoided.13

Night Attack on the Escarpment

At 1607 on 18 April a lone smoke shell, like a tentative mistaken shot, landed 200 yards east of Machinato Inlet. A breeze wafted the smoke west toward the sea and spread a thin haze over the inlet. Assault troops who had assembled casually on the northeast side of the inlet during the afternoon now waited tensely. Within a few minutes other shells landed. Veiled by smoke, infantrymen sprinted along a pipeline to the western edge of the inlet. In a few minutes Company G, 106th Infantry, had crossed the inlet in this manner and had assembled under cover of the cliffs that border the inlet on the west.

Company G’s mission was to clean out the enemy outposts in the Machinato village area in order that the bridge construction and the movement of troops across the inlet during the night might proceed without detection. Operating

by platoons, the company scaled the cliffs and maneuvered around the enemy outposts. By midnight, after a series of skirmishes, ambushes, and brief fire fights in the dark, the Japanese in the Machinato area had been cleaned out.

The 27th Division was now on the move. At 1930 trucks carrying Bailey bridge equipment began moving out of a coral pit in the village of Isa and rolling south to the inlet. The last truckload of Bailey equipment was followed at 2000 by the first full load of material for the footbridge. The ponton bridge was shuttled forward at 2030. Shortly after dark the bulldozer began to put the finishing touches on the approaches to the footbridge and ponton bridge to enable the trucks to drop their loads at the edge of the inlet. Working in the darkness, quietly and without interruption, the engineers completed the 128-yard footbridge: by midnight and both Bailey bridges by 0300, 19 April. Only the ponton bridge caused trouble; the receding tide carried away the anchor line and some of the pontons, delaying completion of the bridge until noon of 29 April.

The 106th Infantry moved out shortly after midnight. Throughout the night a steady stream of men trudged across the footbridge. The enemy made no move to stop the crossing; Company G had done its work well. Company F of the 106th passed through Company G’s lines just before dawn and quietly advanced single file along Route r toward the road cut at the northwest end of Urasoe–Mura Escarpment. Since the cut was believed to be defended, a frontal assault up the highway would be costly, even during darkness. Near the base of the escarpment, one platoon of the company turned off the road to the right (west) and started climbing the brush-covered slope. Half an hour later the troops reached the top, still undetected by the enemy.

The platoon swung left (southeast) on the crest and silently moved down the ridge line of the escarpment toward the cut. It was now daylight. Near the cut they found Japanese soldiers sitting around fires, preparing their breakfast. The Americans immediately opened fire. Some of the enemy dropped; others fled toward the cut, leaving their weapons behind. The enemy was now alerted. Soon mortar fire began dropping on the rest of Company F as it moved up the highway. The platoon on top of the escarpment began sweeping rapidly toward the cut. For thirty minutes there was a brisk fight as the Americans closed in on the enemy; then, outflanked, the Japanese gave way and fled south from the cut.

The 206th began consolidating its hold on the northwest end of Urasoe Mura. By 0710 additional platoons were arriving on the crest near the cut and

the few remaining Japanese were being flushed out of their hiding places. The 106th prepared to push down the escarpment toward an eventual junction with the 105th. The attack had started auspiciously for the 27th Division. But by now the whole front was alive with thundering conflict.

The General Attack

As the morning mists cleared, the campaign’s largest single air strike was delivered. By 0900 Yonabaru had been hit by 67 planes spreading napalm that burned everything above ground, Iwa had been devastated by a strike of 108 planes, and Shuri by a strike of 139. A total of 650 Navy and Marine planes bombed, rocketed, napalmed, and machine-gunned the enemy. Six battleships, six cruisers, and six destroyers of the Fifth Fleet added their fire power to that of the planes and artillery. These sledge-hammer blows fell on about 4,000 combat veterans of the Japanese 62nd Division who were manning the positions.14

The greatest concentration of artillery ever employed in the Pacific war sounded the prelude to the attack at dawn. Twenty-seven battalions of Corps and division artillery, 324 pieces in all, ranging from 105-mm. to 8-inch howitzer, fired the first rounds at 0600. This concentration represented an average of 75 artillery pieces to every mile of front, and actually it was even greater as the firing progressed in mass from east to west. The shells thundered against the enemy’s front lines for twenty minutes, then shifted 500 yards to the rear while the infantry simulated a movement as if beginning the attack; at 0630 the artillery shifted back to spray the enemy’s front lines for the next ten minutes with time fire. In forty minutes American artillery placed 19,000 shells on the enemy’s lines. Then, at 0640, the artillery lifted to enemy rear areas.

The assault platoons advanced, hopeful that the great mass of metal and explosive had destroyed the enemy or had left him so stunned that he would be helpless. They were soon disillusioned; for the Japanese, deep in their caves, had scarcely been touched, and at the right moment they manned their battle stations.15 Brig. Gen. Josef R. Sheetz, Commanding General, XXIV Corps Artillery, later said he doubted that as many as 190 Japanese, or 1 for every 100 shells, had been killed by the morning artillery preparation.16

Opening action, 19 April, was the crossing of Machinato Inlet on footbridge in the early morning

Supporting artillery included this 8-inch howitzer unit, one of the first used against the Japanese in the Pacific fighting

The 7th Division is Stopped on the East

The 7th Division faced the 11th Independent Infantry Battalion, which occupied a line extending from the east coast through the high ground immediately inland. The 7th was deployed with the 32nd Infantry on the left and the 184th on the right. The plan of attack called for the 32nd Infantry to seize Skyline Ridge, the eastern anchor of the Japanese line, and for the 184th to capture Hill 178 and the area westward to the division boundary, which lay just beyond a long coral spine later known as the Rocky Crags. The main effort was to be made by two battalions down the center, along the lip of high ground leading to Ouki Hill, an extension of Skyline Ridge, high on the eastern slope of Hill 178. Once this point was reached the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, was to turn downhill along Skyline Ridge to the left (east), and the 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, was to turn right (west) uphill against the crest of Hill 178.17

Two medium tanks and three armored flame throwers rumbled southward from the 7th Division’s lines on the coastal flats, passed through Ouki, and quickly moved into position at the tip of Skyline Ridge. They poured shot and flame into the cluster of enemy-occupied tombs and emplacements at the lower extremity of the ridge. The long jets of orange flame probed all openings in the face of this part of Skyline, and dark, rolling masses of smoke billowed upward. This was a new spectacle for the waiting infantry, who watched fascinated. For the enemy who died in the searing flame inside their strong points, there was hardly time to become terror-stricken. This phase of the attack lasted fifteen minutes, and then, just after 0700, the infantry moved up. All the Japanese on the forward face of the tip had been killed by the flame, but there were others on the reverse side who denied any advance across the crest. The battle of the infantry quickly erupted and smoldered along the narrow knife-edge line of Skyline Ridge. American troops clung desperately to the forward slope through two Japanese counterattacks, in which the enemy crowded forward into his own mortar fire to hurl grenades and satchel charges.

Higher up along the slope leading to Ouki Hill, the assault troops advanced about 500 yards without a shot being fired at them. Then suddenly, as they moved into a belt of ground covered by preregistered Japanese mortar and machine-gun fire, enemy weapons let loose and all forward movement stopped. Efforts to advance were unavailing throughout the day, and at 1620 the men pulled back to their former positions. The 3rd Battalion was now compelled to

give up its slight hold on the lower end of Skyline Ridge, where it had suffered almost one hundred casualties, including thirteen killed, during the day.

On the division’s right, the coral spine of the Rocky Crags, so named for the two dominating, jagged knobs, extended southward several hundred yards. It paralleled the direction of the American attack, pointing directly at the bold, white face of the Tanabaru Escarpment almost a mile away. For two days this ridge had been pounded by artillery. Company K of the 184th Infantry was directly in front of the northern point of the Crags. Patrols had not been molested. Observers had seen Japanese running about among the tombs on the slope but had not guessed that the coral outcropping was honeycombed with tunnels and caves stocked with weapons and alive with troops. Nor was it known that this area was an impact zone for artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire from preregistered enemy weapons. All this was discovered on the morning of 19 April. Company K advanced 200 yards. Then, at 0730, it entered the forbidden zone and was pinned to the ground by the enemy fire. The adjoining company on the left, raked by enfilading fire from the Crags, was also stopped. Shortly after noon, Company K pulled back from along the eastern slope of the northernmost of the crags. At the end of the day there had been no gain.

96th Division Attack Stalls

Meanwhile the 96th Division was attacking farther west, with the 382nd Regiment on the left (east) and the 381st on the right (west). The 382nd Infantry had the task of taking Tombstone Ridge and the Tanabaru Escarpment; the 381st, that of seizing Nishibaru Ridge and the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment beyond. The 3rd Battalion, 381st Infantry, on the division right at the saddle between Kakazu and Nishibaru Ridges, was a mile ahead of the division left. Facing the 96th in the Kaniku–Nishibaru sector, the 12th Independent Infantry Battalion, which had absorbed the depleted 14th Independent Infantry Battalion, defended the center. It had the 1st Light Machine Gun Battalion attached, and altogether numbered about 1,200 men.18

On the left, the 2nd Battalion of the 382nd Infantry moved out at 0640 and began occupying the series of small hills to the front, only a few of which were held by the enemy. Sniper and mortar fire from the Rocky Crags on the left was a source of trouble and caused casualties. A few spots of resistance developed but were easily overcome. At one point a Japanese popped out of a small roadside cave and satchel-charged the lead tank of a column; by a strange quirk the tank

toppled over against the hole and closed it. The road was now effectively blocked to the other tanks. A few scattered grenade fights took place but did not prevent a gain of 800 yards on the division’s left.

Immediately to the right there was no opposition to the advance of the 1st Battalion until Company C on the left and Company A on the right started a pincer move against the northern tip of Tombstone Ridge, so named because of the large number of burial tombs on either side. About seventy-five feet high and half a mile long, it was the dominating terrain feature of the vicinity. As soon as the two companies moved forward the Japanese positions on the ridge broke their silence. Company C was stopped on the east side by machine-gun and mortar fire, Company A on the west side by grenades. Artillery and tank fire was brought on the position to neutralize it. At noon Company A charged up the west slope only to find that it could neither stay on top nor go down the other side. The company commander was killed on the crest. In the midst of this action a supporting tank was lost to a 47-mm. antitank gun. At the end of the day the 1st Battalion held only a precarious position across the northwest nose of the ridge and along a portion of the west slope. The crest was nowhere tenable and the east side was wholly in the hands of the Japanese. Though Tombstone Ridge was unimposing from a distance, it harbored a maze of mutually supporting underground positions that opened on either face and made it a formidable strong point.

Up ahead and to the west, Nishibaru Ridge was under attack. This ridge was separated by a depression and a ravine, upper Kakazu Gorge, from the southern end of Tombstone Ridge, to which it ran at right angles for a mile in a generally east-west direction. Nishibaru Ridge was an extension of Kakazu Ridge, separated from it by only a wide, shallow saddle, through which passed Route 5, the Ginowan–Shuri road. The stream which emptied into Machinato Inlet began in the hills northeast of Tanabaru and ran along the northern base of Nishibaru and Kakazu Ridges the entire way to the sea, forming at times, as in front of Kakazu, a gorge-like bed.

The 1st Battalion, 381st Infantry, moved from its position just north of Kaniku through the western part of the town and pressed forward into the open, despite machine-gun fire from southeast Kaniku. Company C on the left was only a short distance from Tombstone Ridge and had a difficult time because of enemy fire from this elevation paralleling its course. The company fell behind, and soon some of the men were pinned down in the open, unable to continue until dark. Huge spigot mortar shells began falling at 1045, adding their

Battle for Tombstone Ridge, like many others on Okinawa, did not permit much use of heavy armored weapons because of uneven terrain. Above an M-7 self-propelled 105-mm. howitzer, supporting 96th Division troops, fires at a Japanese position

Men of the 1st Battalion, 381st Infantry, bend low as they run through burning ruins of western Kaniku, 19 April

tremendous explosions to the din. A part of the battalion reached the northern face of Nishibaru Ridge, but even this slight gain was lost when the battalion withdrew from the exposed position at the end of the day.

On the division’s right, the 3rd Battalion of the 381st Infantry waited for thirty-five minutes in its place along the southern bank of the gorge for the 1st Battalion, still not in sight; the assault troops of the 3rd Battalion then moved out, Company K on the left and Company I on the right. As soon as they passed over the lip of the gorge embankment, the troops from Company K drew knee mortar, machine-gun, and rifle fire from cave and tomb positions in Nishibaru Ridge. One squad rushed an enemy position, killing five Japanese and destroying a machine gun and two knee mortars. But immediately above it a second and then a third machine gun opened up, killing four and wounding two of the small group. Despite these difficulties two platoons managed by 0830 to advance over the crest of the ridge as far as the upper edge of the village of Nishibaru. Here all progress ended when showers of mortar shells and hand grenades formed a frontal barrier and enfilade machine-gun fire from both flanks was added. The survivors drew back over the crest and dug in on the forward slope, hoping that if they held out there help would come during the day. Company K had its third commanding officer in twenty-four hours; the first had been killed, the second wounded.

On the right, the first three men of Company I who tried to cross the hump of ground in front of Nishibaru Ridge were one after the other killed. Machine-gun fire came from the western end of Nishibaru Ridge directly in front and from the nose of Kakazu Ridge across the road to the right front. Exposure for even a moment meant death or a wound. It was here that the 96th Division joined the 27th Division, the boundary running just west of the Ginowan–Shuri road at the saddle between Kakazu and Nishibaru Ridges. Lt. Col. D. A. Nolan, Jr., commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 381st Infantry, realized the necessity for coordinated effort after the morning of death and failure. He crossed over to the adjoining unit, Company C, 105th Infantry, 27th Division, to discuss with Capt. John F. Mulhearn, its commanding officer, the possibility of a joint attack using five tanks which Colonel Nolan had available. But this proposal could not be acted upon because Captain Mulhearn was then preparing, as part of a battalion movement, to start his men around Kakazu to the right. It was now midafternoon, and, realizing that he could not hope to advance with the Kakazu area on his right front vacated, Colonel Nolan obtained authority from his regimental commander, Col. M. E. Halloran, to

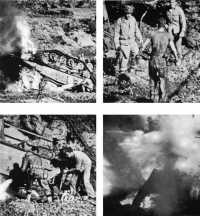

Death of a tank. A series of photos enlarged from a movie film of Okinawa fighting. Sherman tanks, supported by riflemen, are assaulting Japanese cave positions, and in the engagement a tank is overturned by a Japanese land mine. One of the crew is thrown clear by the blast. Infantrymen fight flame with fire extinguishers in an effort to rescue four tank men trapped in the vehicle. Before rescue can be effected fire reaches ammunition in the tank, and the resulting explosion leaves only a battered metal hulk

move his men back into the protection of the gorge.19 Before this withdrawal began, one of the five tanks ventured through the saddle between Kakazu and Nishibaru Ridges and was immediately destroyed by a swarm of Japanese attacking with satchel charges from the nose of Nishibaru Ridge.

Company L came up from reserve to close the gap between the 1st and the 3rd Battalions. This movement drew enemy fire, and on reaching the gorge the company dug in along the edge. From there it gave fire support for the withdrawal of the other companies in front. While it was thus engaged three spigot mortar shells fell on the company and buried several men. The number of 81-mm. mortar shells that fell on the 381st Infantry during the day in front of and on Nishibaru Ridge was estimated at 2,200. By 1700 the 3rd Battalion had suffered eighty-five casualties, including sixteen killed.20

Kakazu Ridge Is Bypassed

Meanwhile various maneuvers were taking place on the right in the 27th Division zone. Following the two battalions of the 106th Infantry that had crossed Machinato Inlet under cover of darkness and had established themselves before dawn on the western end of the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, the 3rd Battalion of the 106th left Kakazu West at 0600; it was crossing Machinato Inlet when the general attack got under way elsewhere. The battalion mounted the escarpment and took a position along the crest between the other two battalions. The Reconnaissance Troop was now on the extreme right of the escarpment.

The only other 27th Division unit on the front line ready to join in the initial assault was the 1st Battalion of the 105th Infantry. This battalion was deployed along Kakazu Gorge, with Kakazu Ridge, immediately in front, its initial objective. Company C was on the left, next to the Ginowan–Shuri road; Companies B and A, in the order named, were to the west, the latter being initially in reserve. The attack of the 1st Battalion was planned to combine a frontal assault against the ridge with a sweeping tank attack around the east end of Kakazu Ridge. The two forces were to meet behind the ridge near the village of Kakazu and to join in a drive to the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment beyond.

The troops began moving up to the ravine on schedule at 0730, fifty minutes after the attack began on the east and in the center. At 0823 the leading elements were on the crest of a little fold of ground lying a short distance beyond the ravine, facing Kakazu Ridge 200 yards away across open ground. Now, as they started to move quickly down into the open swale, machine-gun and mortar fire from close

range struck them. At once there were casualties, and casualties kept mounting. Those in the open were pinned down; those behind could not reach them. The tip of Kakazu and the western slope of the saddle were ablaze with enemy guns.

At 0830, just before the infantry left the protection of the little fold in front of Kakazu, tanks in groups of three and four in column formation began moving across Kakazu Gorge; they then continued southward through the saddle between Kakazu and Nishibaru Ridges. Altogether about thirty tanks, self-propelled assault guns, and armored flame throwers moved out of the assembly area that morning for a power drive, against the Japanese positions, Company A of the 193rd Tank Battalion making up the major part of the force. Three tanks were lost to mines and road hazards in crossing the gorge and the saddle. As the tanks moved down the road in column, a 47-mm. antitank gun, firing from a covered position to the left on the edge of Nishibaru Ridge, destroyed four tanks with sixteen shots, without receiving a single shot in return. The tank column hurried on south to look for a faint track leading into Kakazu that had shown on aerial photographs: the column missed it, lost another tank to antitank fire, and then in error took a second little-used trail farther south and began working over enemy positions encountered in the face of the escarpment and in the relatively flat country to the east of Kakazu. Discovering that they could not reach the village from this point, the tanks retraced their way to the main road, turned back, found the right trail, and were in Kakazu shortly after 1000. They moved around and through the village, spreading fire and destruction; Kakazu was completely shot up and burned during the next three hours. Fourteen American tanks were destroyed in and around the village, many by mines and 47-mm. antitank guns, others by suicide close-attack units, and more by artillery and mortar fire. During the day six tanks in the Kakazu–Nishibaru area were destroyed by suicide attackers using 22-lb. satchel charges, which were usually thrown against the bottom plate. A majority of the tank crew members were still living after the tanks had been disabled, but many were killed by enemy squads that forced the turret lids open and threw in grenades.21

At 1330, since it was now evident that infantry would not be able to reach them, the tanks received orders to return to their lines. Of the thirty tanks that had maneuvered around the left end of Kakazu Ridge in the morning, only eight returned in the afternoon. The loss of twenty-two tanks on 19 April in the Kakazu area was the greatest suffered by American armor on Okinawa in a single engagement.22 The tanks had operated wholly without infantry support. Four of the twenty-two were armored flame throwers, and this was their first day in action. Some crew members of tanks destroyed by antitank gun fire dug pits under their tanks and remained hidden forty hours before they escaped, incredibly unmolested by the scores of Japanese within 100 yards.

The Japanese had guessed that a tank-infantry attack would try to penetrate their lines between Nishibaru Ridge and Kakazu Ridge, and they had prepared carefully for it. Their plan was based on separating the infantry from the tanks. The 272nd Independent Infantry Battalion alone devised a fire net of four machine guns, two antiaircraft guns, three regimental guns, and the 81-mm. mortars of the 2nd Mortar Battalion to cover the saddle between the two ridges. The machine guns were sited at close range. In addition, two special squads of ten men each were sent forward to the saddle for close combat against the infantry. One group was almost entirely wiped out; the other had one noncommissioned officer wounded and three privates killed. The enemy defense also utilized the 47-mm. antitank guns of the 22nd Independent Antitank Gun Battalion and close-quarters suicide assault squads. So thorough were these preparations that the Japanese boasted “Not an infantryman got through.” (See Map 24.)

It was here in the Kakazu–Urasoe–Mura Escarpment area that the most extensive reorganization of Japanese units had taken place just before the American attack. The remnants of badly shattered battalions were combined into a composite unit of about 1,400 men that consisted largely of members of the 272nd Independent Infantry Battalion but also included elements of the 13th, 15th, and 23rd Battalions. The 21st Independent Infantry Battalion stood ready to support the 272nd. The 2nd Light Machine Gun Battalion added its fire power.23

While the tanks were operating alone behind the enemy’s lines, the 1st Battalion, 105th Infantry, was pinned to the ground in front of Kakazu Ridge. A 34-man platoon from Company A that moved out ahead of the main attack

was allowed to pass over Kakazu Ridge undisturbed only to walk into a trap. When the platoon reached the northern edge of Kakazu village, the trap was sprung. None of the men in the platoon returned during the day, but by separating into small groups and hiding in rubble and in tombs most of them escaped death. Six men returned to the American lines that night, seventeen made their way out the next day, and two more were rescued on 25 April. Eight had been killed and others badly wounded.24

With the 1st Battalion of the 105th Infantry completely stopped, the 2nd Battalion was ordered at 0907 to move up on the boundary at the extreme left and apply pressure along the Ginowan–Shuri road. In coming up to reconnoiter this ground, the battalion commander was hit four times when he jumped over a low stone wall into the open ground opposite the tip of Kakazu. When the 2nd Battalion finally attacked at 1225 in an attempted movement around to the left, it was turned back at the east end of Kakazu Ridge. Simultaneously with the movement of the 2nd Battalion, the 3rd Battalion, which had relieved the 3rd, 106th Infantry, in the morning, moved down from Kakazu West, bypassed Kakazu village, and by 1535 had two companies, L and I, on top the Urasoe Mura Escarpment, on the east side of the 106th Infantry. During the afternoon the weather had become increasingly unsettled, with high wind and some rain.

At 1530 Capt. Ernest A. Flemig, who had assumed command of the 2nd Battalion, 105th Infantry, earlier in the day, asked to be allowed to move around the west end of Kakazu Ridge to join the 3rd Battalion on the escarpment. This permission was given by Col. W. S. Winn, the regimental commander, at approximately 1600. The battalion moved off and by 1800 had taken up a position on the slope at the base of the escarpment below the 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry. At the same time, the 1st Battalion, 105th, was ordered in front of the village of Kakazu to become regimental reserve. “Front” as represented by the position actually taken by the 1st Battalion was southwest of the village in front of the escarpment. Thus by late afternoon the entire Kakazu Ridge front had been abandoned by the 105th Infantry. It was just before this shift of positions that Colonel Nolan made his suggestion for a joint attack. In front of Kakazu Ridge during the day, two battalions of the 105th Regiment had suffered 158 casualties: the 1st Battalion, 105, and the 2nd Battalion, 53.

On the western end of the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, the 2nd Battalion of the 106th Infantry tried to work south after its successful night attack; but it ran

West end of Urasoe–Mura escarpment, area of 27th Division attack (photographed 10 July 1945)

into a series of cave, tomb, and tunnel positions along the ridge to the west of Route 1 and was fought to a standstill. This was the beginning of what later became known as the Item Pocket battle. Elsewhere on the escarpment the 106th was, in general, stopped after its presence was discovered at daybreak. Elsewhere on the escarpment the 106th was also unsuccessful in advancing to the south, but it did extend its lines to the east to join the 3rd Battalion, 105th.

The bridges across Machinato Inlet were subjected to Japanese artillery and mortar attack shortly after daybreak. Direct tank fire silenced a gun firing from a cave position in the face of the escarpment, but 320-mm. mortar shells then began dropping in the crossing area, known as “Buzz Bomb Bowl.” An enemy artillery barrage on the crossing area began at 1530, and by 1600 one of the Bailey bridges and the ponton bridge were out, only the footbridge remaining. This was the beginning of a week-long struggle to keep bridges across the inlet.

The big attack of 19 April had failed. At no point had there been a breakthrough. Everywhere the Japanese had held and turned back the American attack. Even on the west, where the front lines had been advanced a considerable distance by the 27th Division, the area gained was mostly unoccupied low ground, and when the Japanese positions on the reverse slopes of the escarpment were encountered further gain was denied. Everywhere the advance made early in the morning represented only an area lying between the line of departure and the enemy’s fortified positions. As a result of the day’s fighting the XXIV Corps lost 720 dead, wounded, and missing.