Chapter 9: Fall of the First Shuri Defense Ring

The mood of the American troops on the morning of 20 April was far different from what it had been the morning before. The feeling now was one of weariness and awareness that breaking through would be slow and costly. The most immediate and pressing objective was to consolidate the line for further advance and, in particular, to eliminate the gap of approximately a mile that existed between the 96th and 27th Divisions when darkness fell. The strong Japanese position at Kakazu Ridge lay in the middle of this gap, bypassed by the 27th Division, and the heart of the Japanese stronghold was behind it to the south. If the enemy could take advantage of the gap he might counterattack and reach the rear of both the 27th and 96th Divisions. Two points of view existed with regard to bypassing Japanese positions. One was represented by General Griner, 27th Division commander, when he ordered that the movement must be forward even if it meant bypassing Japanese and mopping them up later. The other was expressed by Colonel Halloran, the commanding officer of the 381st Infantry, 96th Division, when he said on a later occasion: “You cannot bypass a Japanese because a Jap does not know when he is bypassed.”1

The primary responsibility for ensuring that dangerous gaps did not develop between units, and that the attack along unit boundaries was coordinated, rested upon the unit commander on the right.2 The large gap in the 27th Division zone must have alarmed General Griner, since after dark, at 1930, he ordered Company B, 165th Infantry, to take up a position in front of Kakazu Ridge.

Item Pocket

In accordance with General Griner’s plan, Col. Gerard . W. Kelley, commander of the 165th Infantry, on 20 April had two battalions abreast and ready to attack on the right of the 27th Division line. The 1st Battalion, commanded

by Lt. Col. James H. Mahoney, was on the left, and the 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. John McDonough, on the right. A mile southwest of the 165th lay Machinato airfield and three miles beyond the airfield was Naha – both important objectives. Although photographs and maps did not reveal to any precise degree the strength of the Japanese or the nature of the terrain, regimental headquarters was optimistic. On the morning of the 20th Lt. Col. Joseph T. Hart, regimental executive officer, brought out a large green sign, “CONROY FIELD,” in honor of the 165th’s commander killed on Makin, and announced that he expected to nail it up at Machinato airfield by evening. He added that the regiment would “hold a dance in Naha on Saturday night.”3

Item Pocket Blocks the Way

Such hopes proved to be illusory before the fighting of 20 April was more than a few hours old. Almost immediately the regiment hit intense resistance in rough ground north of Gusukuma. When the 1st Battalion drove south along Route 1, the Japanese entrenched in this area cut off the forward elements with heavy mortar and machine-gun fire, killing five and wounding twenty-two. Only by dogged efforts was the battalion able to reach a point east of Gusukuma by nightfall. It had then lost contact with the 2nd Battalion, which was meeting equally stiff resistance west of the Japanese position. (See Map 25.)

The center of the Japanese resistance lay in the I section of Target Area 7777, which came to be called “Item Pocket” – in military terminology I is called Item. Actually, the pocket was the hub of the enemy position; from it, like spokes of a giant wheel, extended four low ridges, separated from each other by ravines and rice paddies. Potter’s Ridge ran north from the hub, Charlie Ridge to the northeast, Gusukuma Ridge to the southeast, and Ryan Ridge to the southwest. Lying between Gusukuma and Charlie Ridges and sloping to the east was a cone-shaped hill called by Americans “Brewer’s Hill.” A gulch ran along each side of the hill Anderson’s Gulch on the north and Dead Horse Gulch on the south. Both ran in an easterly direction, crossing Route 1 at small bridges just north of Gusukuma. The ground was superbly suited for active defense. Typical Japanese positions were connected by tunnels along the sides and under the crests of the ridges; Ryan Ridge, in particular, was honeycombed with such defenses. From Item Pocket the enemy had excellent command both of the coastal areas to the north and west and of the open land to the east where Route 1 ran north-south. The Japanese had long been aware of the defensive value of this position against

either a beach landing on the northwest or an attack from the north. Months before the Americans landed, Japanese troops and Okinawan laborers were boring tunnels and establishing elaborate living quarters and aid stations. The area was held by two companies of the 21st Independent Infantry Battalion of the 64th Brigade, 62nd Division, supported by an antitank company, a machine gun company, and elements of antiaircraft, artillery, and mortar units. At least 600 Japanese occupied the Pocket, reinforced by several hundred Okinawans.

Infantrymen of the 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, operating on the right of the 1st Battalion, cleaned out a system of dugouts and tunnels on the southeast nose of Potter’s Ridge on the 20th but Colonel McDonough’s men made little more progress after that day. When the 2nd started a pivoting movement to join up with the 1st Battalion on its left, the troops came under intense flanking fire from the left rear out of the Pocket. Japanese mortars on Ryan Ridge knocked out the machine gunners when they tried to lay down covering fire. The troops retreated to Potter’s Ridge after several hours’ fighting which cost them twelve casualties.

Farther to the west infantrymen managed to reach Fox Ridge, a low rise due west of the hub of the Pocket. Colonel McDonough then ordered Company E on his extreme right to use Fox Ridge as cover and to attack south to seize Ryan Ridge. The leading platoon was well up on the slope of Ryan when Japanese on top opened up with mortars, machine guns, and artillery, cutting off the rest of Company E. While the company commander, his clothes torn by bullets, and the rest of the company straggled back to Fox Ridge, the leading platoon continued doggedly ahead. Its leader, T/Sgt. Earnest L. Schoeff, managed to reach the top with eight of his men despite almost constant fire. He was ordered by radio to hold until relief came. The men hugged the ground as darkness slowly descended. Then from three directions from fifty to sixty heavily armed Japanese set upon the Americans. In wild hand-to-hand fighting the nine men beat off the attack. Pfc. Paul R. Cook fired four cases of ammunition into the enemy, shooting down at least ten before he was killed. With grenades, rifle butts, and the enemy’s own weapons, Schoeff and his men killed another dozen before the Japanese withdrew. With two of his men killed, another missing, and two wounded, Schoeff led the survivors back to his company during the night.

At 0630 on 21 April the 2nd Battalion launched another attack across the mouth of Item Pocket. The troops were supported by antitank guns which had been unloaded at the sea wall, hand carried almost 2,000 yards, and set up to fire directly into the hub of the Pocket. Within ten minutes the entire left of the battalion line was pinned down. Efforts to advance against interlocking lanes

of fire were fruitless and the men withdrew to Potter’s Ridge later in the morning. During the afternoon troops on the battalion’s right, protected from Item Pocket by Fox Ridge, moved several hundred yards along the coast on amphibian tractors. But an attack east toward the Pocket was abortive. As soon as the infantry climbed over the sea wall, the enemy blazed forth from Ryan Ridge with light artillery pieces and small arms. The first rounds were wild, and every man scrambled back safely over the wall. Another attempt under such conditions seemed out of the question. Again the troops pulled back to Fox Ridge. (See Map 26.)

Thus with little difficulty the Japanese defending the western approaches of Item Pocket repulsed the Americans on 21 April. The enemy’s defense was equally effective on the east. Here the 1st Battalion had a major supply problem on its hands. Two blown bridges along Route 1 east of the Pocket were holding up vehicles of support units. During the previous night, fire from the Pocket had driven off an engineer platoon working at the site and killed the platoon leader. Early on the 21st Lieutenant Golden, the Bailey bridge expert, came up with ten truckloads of material. His engineers worked for an hour but had to stop in the face of almost ceaseless fire from the Pocket.

Colonel Kelley then ordered scouts to find another stream crossing. A bulldozer cut a bypass around Anderson’s Gulch near the railroad, but when, about 1000, the operator nosed his machine out in the open, he was shot in the ear. General Griner, in Colonel Kelley’s observation post at the time, ordered Lt. Col. Walter F. Anderson, commander of the 193rd Tank Battalion, to push the bypass through. Anderson himself climbed into his battalion’s sole remaining “tank-dozer” and completed the bypass. A 47-mm. antitank gun, hitherto silent, scored a direct hit on Anderson’s tank, killing him and a guide. The bypass was now blocked and had to be abandoned.

This break-down in supply over Route 1 seriously affected operations east of Gusukuma. Colonel Mahoney’s 1st Battalion attacked southwest early on the 21st into Gusukuma, but without tanks or cannon the troops made little ground against machine guns in the village and fire from Item Pocket on the right rear. Mahoney’s left company did reach a point 400 yards north of the village of Yafusu – the farthest advance yet registered by XXIV Corps since 19 April – but here the troops were stopped by a network of enemy positions.

Fight of Dead Horse Gulch

Colonel Kelley, back at his headquarters, was becoming increasingly worried about the wide vertical gap between his 1st and 2nd Battalions. Early on 21 April

Item Pocket area (photographed 10 July 1945), which the 27th Division spent nine days in taking

he decided to commit his 3rd Battalion, under Lt. Col. Dennis D. Claire, in a move designed to plug the gap and break into Item Pocket in one blow. Using Route 1 as its line of departure, Company L was to push west through Dead Horse Gulch, outflanking the Japanese covering Anderson’s Gulch. Simultaneously Company K, on L’s left, would attack northwest toward the Pocket along Gusukuma Ridge. Even moving into the line of departure was so difficult in this area swept by fire from artillery, spigot mortars, and light arms that it was 1515 before the battalion attacked.

Under a heavy smoke screen, Company L advanced along Dead Horse Gulch. In forty-five minutes the infantry was pinned flat to the ground under a hail of light-arms fire. The men could only crawl into holes. When the smoke cleared, Japanese machine gunners worked over the area. At dusk the company retreated down the gulch.

Company K, commanded by Capt. Howard E. Betts, Jr., was the other prong of the battalion attack. The company skirted the eastern edge of Gusukuma under heavy fire and drove up to the crest of Gusukuma Ridge. From here Captain Betts launched an attack down into Dead Horse Gulch with one platoon and sent the other along the crest of the ridge to cover the men on the low ground. In a savage encounter Company K fought its way almost into the heart of the Pocket. But the odds were against it; within an hour it had lost 6 men killed, 3 missing, and 15 wounded. The troops could advance no farther against the virtually intact Japanese defenses. Under cover of smoke and twilight, Betts pulled his men back to the crest of Gusukuma Ridge. He was forced to leave behind several of his wounded, who crawled into caves. A squad leader, himself wounded twice, tried to evacuate these men, but he was hit four times in the attempt and later died.

Company K had hardly begun digging in on the rocky crest of Gusukuma Ridge when the Japanese began a series of attacks that lasted four hours. The first, well-supported by enemy artillery, was driven off by the troops and artillery, but all men still in the gulch were killed in the onslaught. Low on ammunition and unable to evacuate the wounded, the men of Company K hung on under heavy fire and incessant sniping. At 2300 the enemy launched an all-out attack, striking simultaneously from Gusukuma and from the gulch. The Japanese overran and captured two machine guns and turned them on the outnumbered and disorganized Americans. Betts managed to pull his remaining men back to the 1st Battalion line, 200 yards to the south. Company K was now down to half-strength.

The engagement had a grim aftermath. Early the next morning the Japanese attacked the caves in Dead Horse Gulch where some wounded Americans had hidden. With grenades and bonfires the Japanese forced some of the Americans into the open, where they were shot; the others were stifled to death inside.

On 22 April General Griner, who was mainly concerned with coordinating the movements of his 105th Infantry with the 96th Division on the left (east) and was not too much impressed by the strength of the enemy in Item Pocket, ordered Colonel Kelley to hold and improve his positions. In conjunction with the 106th on his left, Kelley therefore shortened his 1st Battalion line to present a more compact front. A heavy air strike was delivered on the Pocket without major effect. Patrol action was intensified. All remaining Japanese were cleared out of Potter and Charlie Ridges. Artillery, well registered in, prevented the enemy from retaking any ground. (See Map 27.)

The patrols brought back information on Japanese dispositions, providing the basis for the next day’s plan. Under that plan Company I was to attack from the nose of Potter’s Ridge across the mouth of the Pocket and seize the face of Ryan Ridge. Meanwhile Company C would send a platoon over Brewer’s Hill and down into the heart of the Pocket. Then Company I was to consolidate its hold on Ryan and, together with Company K, drive along Ryan Ridge to Machinato airfield. A special assault squad was set up to establish the all-important “beachhead” on the face of Ryan Ridge. Commanded by S/Sgt. Howard Lewis, this squad consisted of twelve men, heavily armed with BAR’s, rifles, bazookas, demolitions, and a portable flame thrower.

Early next morning, the 23rd, Sergeant Lewis worked his squad through the tombs on the nose of Potter’s Ridge to the bare flat ground at the base. A Japanese mortarman opened fire on them from the top of Ryan Ridge just above the center of the Pocket. Sergeant Lewis spotted the position and sent his men toward it as their first objective. One by one the men sprinted toward Ryan Ridge. Two Japanese machine guns opened up. The lead man, together with most of the squad, took cover at the base of Ryan. Below, other enemy machine guns were firing. Lewis was now cut off from reinforcement.

Climbing from rock to rock on the craggy nose of Ryan Ridge, the squad made its way to within forty yards of the mortar position. A shower of potato-masher grenades stopped the advance. Lewis deployed his squad, sending four to the right and two to the left and bringing up his bazooka man for direct fire into the position. Advance was impossible; the area now seemed to be swarming

with Japanese trying to move in to finish off the squad. Crawling from rock to rock in Indian fashion, the Americans held them off. Lewis called for artillery fire within forty yards of his position. The rest of Company I, still waiting on Potter’s Ridge, put long-range fire on the enemy. The enemy replied with machine guns and mortars. The Pocket was an inferno of bursting shells and of rifle and machine-gun fire.

For three hours Lewis and his men held out, but it was a hopeless fight. At 1300 he called his company on the radio and said that he had only three men left capable of fighting, three being dead and seven wounded. The supporting platoon from Company I had been stopped short. The platoon from Company C had reached the crest of Brewer’s Hill but had not been able to climb down the steep side. The troops lowered charges on ropes over the side and set them off at the cave entrances, but the charges seemed to make little impression. Lewis received orders to pull back with his wounded. Two more Americans were hit on the way back, but most of the wounded were brought out. Only Lewis and one other man returned unwounded.

Item Pocket – on the fourth day of the assault – was still in enemy hands.

Captain Ryan’s Raiders, 24-25 April

The man on whom most now depended was Capt. Bernard Ryan, commanding Company F, 165th Infantry. Subjected nightly to intense artillery concentrations, harassed by numerous enemy patrols in force, compelled to evacuate his wounded and bring in his supplies by water around Kezu Point, lacking direct fire support except from his own mortars, Captain Ryan had operated largely on his own initiative. From 20 to 24 April he had watched Companies E, G, K, and I assault the Pocket from different directions. He correctly reasoned on 24 April that his turn would be next.

Captain Ryan proposed to Colonel Claire a plan calling for an attack by Company F at 0200 on the following day, 25 April, along the same general route as had been followed by Company E on 20 April. This plan was accepted by higher headquarters. Ryan was therefore astonished to receive a telephone call from Colonel Claire at 1900 on 24 April, ordering him to attack Ryan Ridge in one hour over an entirely different route – that followed by Sergeant Lewis on the 23rd. There had been a hopeless mix-up of orders.

It was now necessary for Captain Ryan to execute a complete change of dispositions and attack preparations in the dark. He was calling together platoon leaders for a new briefing when the regular evening barrage began landing in his company. Soon his communications were out and his men pinned down.

Heart of Item Pocket, looking north from Gusukuma Ridge

Later, a series of patrol actions by the enemy slowed his reorganization. In the morning, when Colonel Kelley discovered that Ryan Ridge was still in enemy hands, he ordered Colonel Claire to attack immediately and secure the ridge. Claire felt that the task was impossible and demurred. Kelley thereupon relieved Claire, and Maj. Herman M. Lutz, executive officer, assumed command. Kelley ordered Lutz to attack at 0630; Lutz decided to use Ryan’s original plan.

Captain Ryan realized that the chief obstacles were the Japanese positions in Ryan Ridge and in the heart of the Pocket. From these positions the enemy dominated much of the area between Ryan and Fox Ridges. Captain Ryan’s key to the problem was artillery fire. He reasoned that, since the direction of fire of supporting artillery would be perpendicular to his direction of attack, and the greatest possible lateral deviation would be fifteen yards, he need not worry about overs or shorts. He ordered a 20-Minute preparation on the slopes of the ridge. In briefing his company Ryan stressed the need for a speedy ground attack to exploit the artillery support. The mission would put heavy demands on a company that was tired, undermanned, and low on food, water, and ammunition.

The two assault platoons of Company F started off at a dead run the moment the first shells were fired on the morning of the 25th. Mortars, machine guns, and antitank guns supported them. The attacking infantry was thinned out by enemy fire and natural obstacles, but thirty-one reached the top of Ryan Ridge. They found themselves perched atop a rugged razorback, full of rocks, holes, and blasted vegetation. As the artillery fire receded, Japanese began emerging from “spider holes,” pillboxes, caves, and tunnels. The thirty-one Americans were ready for them. In twenty minutes of fighting similar to previous encounters on Item Pocket ridge tops they killed thirty-five Japanese and chased a larger number off the ridge. Five of the Americans were killed and two were wounded.

The crux of the situation lay in Captain Ryan’s ability to consolidate his position; repeatedly units had gained footholds on these ridges, only to lose them to the enemy. By late afternoon the twenty-four effectives on the ridge had an average of only six rounds of rifle ammunition. They had no medical supplies, and all the aid men were casualties. Radio communication was out. The Japanese, after their first unsuccessful sortie, had rigged a noose around the perimeter and were slowly tightening it. Holding the ridge now depended on Ryan’s initiative.

Ryan fully understood the critical situation. He arranged for Company I to be moved around to his right flank. He planned to repeat the move that had worked so well in the morning. At 1605, fifteen minutes after artillery support opened up, Ryan and the rest of the company reached the crest, suffering five

casualties on the way. Company I failed to make the top, having been cut off on the slopes. After reorganizing his company Ryan departed with two men to find reinforcements – a risky mission in the dark. Company I was still unable to move up, but Captain Betts of Company K was quick to help. By midnight all of Company K were on the ridge.

With more than a hundred men now on the ridge, Ryan and Betts could take the offensive. During the morning of the 26th they swept along the crest of Ryan Ridge in opposite directions. Company F advanced rapidly southwest to a point just opposite the north end of Machinato airstrip. Betts made some progress, then ran into heavy fire near the nose of Ryan Ridge and built up a defensive position. The main task now was systematic burning out and blowing up of caves on the western slope of the ridge. The Japanese still held several areas in Item Pocket, but the Americans were on Ryan Ridge to stay. The 165th could now establish an unbroken regimental line and prepare to continue the advance south.

Item Pocket Reduced, 26-27 April

Captain Ryan’s attack on the 25th coincided with an assault launched southwest of Ryan Ridge on Gusukuma by other companies of the 165th. In bitter fighting that lasted all day the troops moved from wall to wall and tree to tree into the debris of Gusukuma. At one time Company A was receiving fire from eight machine guns, at least one 47-mm. antitank gun, and mortars. Much of it came from the eastern slope of Ryan Ridge, not yet reduced. Riflemen made the main effort. One of them, Pfc Richard King of Company A, killed a Japanese tied in the crotch of a tree, sat on a limb beside the dead sniper, and killed ten enemy soldiers before nightfall.

Fighting in and around Item Pocket raged on through the 26th. American troops were now pressing in on the heart of the Pocket from all directions. Casualties were still running high. On the 26th, a full week after the 165th began its attack, the regiment, as a result of enemy fire on Route 1, was still operating without tanks or self-propelled mounts. Attack after attack by the infantry slowly constricted the Japanese-held area. By the night of the 26th the enemy had been cleaned out of Gusukuma, Ryan Ridge, and all the area west of the Pocket. Cave positions commanding the key bridges on Route 1 were sealed off, and engineers then resumed work.

The first two tanks to arrive south of the Pocket on the 27th were quickly knocked out by 4.7-mm. gunfire. Succeeding tanks worked with the infantry in reducing the remaining positions. Pfc. Alejandro C. Ruiz of Company A administered the final blow to Item Pocket. Exasperated by machine-gun fire and

grenades which had wounded seven of his comrades, Ruiz seized a BAR and charged headlong into the remaining Japanese positions. He moved from cave to cave, killing the enemy within. At 1637 on 27 April the Pocket was declared secure. Many Japanese, however, remained; weeks later they were still emerging from the deep caves and tunnels.

General Griner had become increasingly distressed over the slow progress of the 165th. He was especially disturbed by the confused disposition of the regiment; disorganization had begun as early as 21 April and had increased as Colonel Kelley was forced to split up battalions and detach companies for various missions. On 27 April General Griner, on authority from General Hodge, relieved Colonel Kelley from command of the 265th.

Assaulting the Outer Shuri Defense Ring

While the reduction of Item Pocket was in progress, the 7th, 27th, and 96th Divisions were trying to break through the outer Shuri defense ring. The results of the intense action of 19 April had been disappointing. The day’s fighting had shown that further advance would be very difficult, and this was confirmed by the difficult fighting between the 20th and 24th.

The Japanese outer defenses to the Shuri line were anchored along a hilly mass which extended across the island in a northwesterly direction from the village of Ouki on the east to Machinato Inlet on the west. Behind this mass and echeloned to the right was the formidable Urasoe–Mura Escarpment, the western anchor of the Japanese line. A series of dominating hills which formed natural defensive positions – Skyline Ridge, Hill 178 (the highest point), Tanabaru, and Nishibaru and Kakazu Ridges – stretched along the crest of this hilly mass, and formed the core of the Japanese defense system. The approaches to this system were covered by a number of forward positions which, like Rocky Crags and Tombstone Ridge, were well adapted to the terrain. (See Map 23.)

Facing the 7th Division on the east was Skyline Ridge, barring passage along the coast. On the right of the division was Rocky Crags. Between the two was a series of concrete blockhouses and strong points which guarded the approaches to Hill 178. In the center of the Corps line, on the 96th Division front, was Nishibaru Ridge – an extension of Kakazu Ridge – and Tombstone Ridge, the northwestern slopes of which were held by the 382nd Infantry. On the west, in the area held by the 27th Division, was Kakazu Ridge. The Japanese

atop this ridge commanded Nishibaru’s western slopes and covered the 96th Division’s right flank. In the Kakazu area a gap had developed between the two divisions, and the closing of this gap was to entail the reduction of Kakazu Ridge.

The fighting between 20 and 24 April was to be as difficult as any during the campaign. These days were marked by incessant heavy attack against cave, tomb, tunnel, and dug-in positions with mutually supporting fields of fire. Mortar and artillery fire and armored flame throwers were used extensively, and the infantry engaged in costly assaults and hand-grenade duels at close range. The enemy did not give a single foot of ground; he fought until he was killed. During the first four days there was no material gain over most of the line, except for a few local penetrations. But on the 24th, after a sustained onslaught of four days of heroic effort against Skyline Ridge, Rocky Crags, and equally formidable barriers, the Americans moved into positions – among them Kakazu Ridge – in the first Shuri defense ring.

Skyline Battle

The attack of the 7th Division on Ouki Hill had been stopped on 19 April after hard and bitter fighting.4 This was only the beginning of the struggle for Skyline Ridge, and, in order to see in proper perspective the events of 20 to 24. April, the action of the 7th on 19 April must be reconsidered in detail. (See Map 28.)

At 0640 on 19 April, with Company G on the left and Company F on the right, the 2nd Battalion of the 184th Infantry, 7th Division, led the advance along high ground toward Ouki Hill.5 Company G of the 32nd Infantry trailed at the left rear. The troops had advanced 500 yards when the first mortar shells fell. Quickly the number increased, and machine-gun fire was added; at 0830, 400 yards short of Ouki Hill, the advance stopped. The troops had reached the forbidden zone. The Japanese 11th Independent Infantry Battalion with attached units was defending Skyline Ridge, the anchor of the enemy line, which fell off from Ouki Hill to Buckner Bay. This battalion had received a unit citation during the China war. Composed of five rifle companies and attached gun, machine gun, and mortar companies, it had numbered about 1400 men on 1 April, but by 19 April it had been reduced to from 800 to 1,000 men. In arranging

Skyline Ridge as seen from an observation plane. Ouki Hill and Hill 178 are beyond the top of Skyline

Smoke cover being placed on reverse slope of Skyline during the fighting of 22 April. Note tanks (arrows) and American troops on lower knob of Tomb Hill (foreground)

the defenses of Skyline Ridge the Japanese placed most of their machine guns on the forward (north) face and on the northern and eastern slopes of Ouki Hill. The 81-mm. mortars were on the reverse (southern) slope of Hill 178 to the west of the battalion guns.

After a delay of fifteen minutes, 1st Lt. Daniel R. Leffel, commanding Company G, 184th Infantry, sent a squad under S/Sgt. Gordon P. Foster to feel out the enemy. Keeping close to the ground, the men had moved slowly forward fifty yards when a Japanese machine gun and enemy riflemen a few yards away fired point-blank into them, killing Foster and four others with the first spray of bullets. Pfc. Kenneth J. Klawitter was wounded seriously but could not be reached by the rest of the squad. Lieutenant Leffel radioed for a flame tank. T/Sgt. Garret Schultz, acting 1st Sergeant, tried to rescue Klawitter but was shot in the side as he started to bring him back. Both men then hugged the earth for such protection as it gave. Each move of Company G brought an enemy mortar concentration immediately. Company G, 32nd Infantry, on the left (east), also was stopped.

Down below along the coastal flat Company I, 32nd Infantry, 7th Division, went through Ouki and, following tanks and armored flame throwers, moved against the lower tip of Skyline Ridge, while Company L maneuvered into position on the right (west) for a frontal attack against the ridge. One platoon of Company I assaulted the nose of the ridge after the flame tanks backed away, found that all Japanese at this point had been killed, and occupied the forward face of the tip at 0710. Mortar fire covered the crest and prevented further gain. By this time the leading platoon of Company L, under 1st Lt. Lawrence T. O’Brien, had climbed up the slope of Skyline to the right (west) and started west along the side of the ridge. One hundred yards ahead a northward jog in the ridge and a dip in the crest allowed the enemy on the reverse slope to fire eastward through the dip to the forward face of Skyline. Machine-gun fire, directed against O’Brien’s platoon, now came through the depression, and O’Brien and his men dashed to an abandoned pillbox on the crest. This brought the platoon within grenade range of Japanese on the other side, and the men were forced to scatter. Knee mortar shells began to fall, plummeting almost straight down. Watching the sky, the men could see the descent of the small black objects in time to dash from the calculated point of impact.

To the right of O’Brien’s men another platoon of Company L started up the slope and came into the line of fire of a machine gun that kept silent until the men were exposed. With its first burst the gun wounded nine men, almost half

the platoon, which fell back disorganized to the base of the ridge. Meanwhile the third platoon of Company L, which had taken refuge from mortar fire in burial tombs near the lower tip of the ridge, was trapped inside by a Japanese machine gun that put a band of fire across the entrances of the tombs when anyone tried to get out. In the Ouki coastal area combat patrols of Company B protected the regiment’s left flank, encountering several strong points and killing numerous enemy soldiers.

Just before 1200 a platoon from Company K, west of O’Brien’s position, reached a point within ten feet of the crest of Skyline Ridge. Japanese on the reverse slope made it impossible to occupy the crest, which was just wide enough for a footpath, and only glimpses of the southern side could be secured by a momentary raising of the head. Fortunately the slope of the ridge was so steep that most of the grenades coming over the top rolled down the incline before they exploded. The Company K platoon was hit almost immediately by a counterattack of about fifty Japanese who crawled up on the reverse slope and began to throw grenades. Artillery was called for to help repel the counterattack, but four rounds fell short and killed or wounded most of the platoon. Another platoon was sent forward at once to replace it. Before it could dig in it was struck by a second counterattack of more than a hundred Japanese. The attackers pressed forward through their own mortar fire to a point just under the crest on the south side and engaged in a close-quarters grenade battle. The knife-edge crest of Skyline Ridge now looked from a distance as though it were smoldering. This close fight lasted for an hour, and at the end all of the second platoon had been killed or wounded but six men, who dropped back to the base of the ridge.

Meanwhile enemy pressure against O’Brien’s men down the ridge to the left had not lessened, and it was evident at 1330 that the 3rd Battalion did not have enough strength to push ahead. There were not more than twenty-five men of Companies L and K left on Skyline Ridge. These men were trying grimly to hold on in the hope that the 2nd Battalion, higher up on the approach to Ouki Hill, could get through and start a drive down toward them, or that the platoon cooped up in the tombs below could escape and help.

During all this time the troops in front of Ouki Hill had made no progress. A flame tank had come up and burned out the position encountered by the unlucky squad in the morning, and on its way back it had picked up Klawitter and Schultz, who, badly wounded, had been near the enemy machine gun. Schultz died on the way to the rear.

At 1525 the G Companies of the 32nd and 184th Regiments undertook to resume the attack which had been stalemated since early morning, but with no great promise of success. Along the base of Ouki Hill both companies were pinned to the ground at 1620 by an extremely heavy enemy 81-mm. mortar concentration. Amid the din of exploding mortars slivers of flying metal filled the air. In small groups or singly the men dashed back in short spurts toward their former position. Many were killed instantly while in flight. One man running wildly back toward safety stopped suddenly and assumed what appeared to be an attitude of prayer. In the next instant he was blown to bits by a direct hit.6

There was now no hope that the remnant of the 3rd Battalion near the bottom of Skyline Ridge could stay there, and by 1730 the exhausted men had pulled back to their starting point of the morning. The 3rd Battalion had lost approximately one hundred men along Skyline Ridge during the day. At 2000 the 32nd Infantry was ordered by General Arnold to resume the attack at 0730 the next morning. Rain, which had begun in the afternoon, continued steadily on into the night.

Though American disappointment was keen and losses heavy in the Skyline Ridge fight on 19 April, it was not a one-sided affair. During the day the 1st and 5th Companies of the defending Japanese battalion had been all but annihilated. The 1st Company was wiped out when a tank fired into a cave, setting off satchel charges and killing most of the men, whereupon the company commander committed suicide. The other three companies of the battalion were reduced to about fifty men each in the battles for Hill 178, Ouki Hill, and Skyline Ridge. The machine gun and battalion gun companies each had about eighty men left.

On 20 April the attack centered against Ouki Hill. Skyline Ridge itself was left alone after the experience of the day before. The 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, and Company G, 32nd Infantry, moving out at 0730, were checked almost at once by enemy mortar and machine-gun fire, and the situation remained stalemated all morning. Two armored flame throwers, however, successfully penetrated 400 yards in front of the infantry to burn out an enemy mortar position on the west slope of Ouki Hill. This led Lt. Col. Roy A. Green of the 184th to call Col. John M. Finn of the 32nd Infantry and obtain his approval of a plan for covering the Japanese positions on Ouki Hill and the eastern part of Hill 178

with a mortar concentration and smoke while blanketing Skyline Ridge with a 4.2-inch chemical mortar barrage, as a prelude to an attack on Ouki Hill in which tanks would precede the infantry. Company G of the 184th, now down to nineteen riflemen, was attached as a platoon to Company G of the 32nd Infantry for the assault. It was launched at 1445.

The Japanese, blinded by the smoke, apparently did not see the advancing troops until they were on the lower slopes of Ouki Hill. Heavy mortar fire then began to fall, threatening to break up the American attack. At the critical moment 1st Lt. John J. Holm and S/Sgt. James R. W. McCarthy, the platoon leader and the platoon sergeant of the leading platoon, scrambled on toward the top of the hill, yelling to the others to follow. Individually and in groups of two’s and three’s the men responded, and a feeble line was built up just under the crest. It was none too soon, for a counterattack struck immediately from the other side. Both Holm and McCarthy were among those killed, but the Japanese were repulsed and lost thirty-five killed. Just before dark a platoon from Company F, 184th Infantry, joined the little group on Ouki Hill from the American lines 400 yards to the rear. Tanks brought supplies to the isolated men, and halftracks evacuated the wounded. The Japanese shelled the forward face of the hill throughout the night. Five men were killed and eighteen wounded, all in their foxholes; the two company commanders and several platoon leaders were among the casualties. Before dawn the enemy made another counterattack; although some Japanese came close enough to throw satchel charges, the attack was repulsed.

During the night Japanese with light machine guns infiltrated behind Company G’s lines, and at an opportune moment on the morning of 21 April they opened fire, killing or wounding nine men before being killed themselves by tanks and armored flame throwers. It was nearly 0900 before Company F, hampered by enemy mortar and artillery fire, was able to start the attack down Skyline Ridge. At first there was no resistance, and within forty-five minutes the men reached a deep road cut through the middle part of the ridge. Here they were halted by mortar fire. Company E, 32nd Infantry, coming up on the left (east), was stopped in the cut by a Japanese machine gun emplaced on the narrow crest and by grenades that were rolled down on the leading third platoon. The mortar section then adjusted on a point where Japanese had been seen, not more than twenty yards ahead of the foremost man. (See Map 29.)

At 1230 General Arnold, 7th Division commander, arrived at Colonel Finn’s observation post. A discussion of the situation led these commanders to conclude

that it would be best to delay assault on the lower half of Skyline Ridge until the fall of Hill 178, which would make the enemy’s position on the lower ground untenable. Orders to this effect were received by Maj. John H. Duncan, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, a few minutes after 1400. The order was nullified, however, by an incident then taking place.

When, east of the road cut, a man in the stalled third platoon, Company E, was killed, Sgt. Theodore R. MacDonnell, a gist Chemical Mortar Company observer, was impelled to drastic action. MacDonnell had frequently joined men on the line and shown qualities of a determined infantryman. Now, infuriated, he gathered up a handful of grenades and ran in the face of the machine-gun fire along the slope to a point underneath the spot where he believed the enemy gun to be located, and then started up the 20-foot embankment. When he looked over the crest he failed to spot the gun, but he did see three enemy soldiers and grenaded them. He made two trips to the bottom of the embankment for fresh supplies of grenades, but it was not until his third trip to the crest that he located the machine gun. MacDonnell then slid back to the bottom, grabbed a BAR, and mounted the embankment with it, only to have the weapon jam after the first shot. He skidded to the bottom, seized a carbine, and went back up for the fifth time. On reaching the crest he stood up and fired point-blank into the machine-gun position, killing the gunner and two covering riflemen. MacDonnell then hurled the machine gun down the slope behind him. A mortar that he found in the position was also sent crashing down the hillside. Sergeant MacDonnell was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism on this occasion.7

Lt. Fred Capp, commanding Company E, sent troops to reinforce MacDonnell immediately, and the position was consolidated. Then Company F, on orders given as a result of this sudden development, pressed the attack down Skyline Ridge, and by 1800 the entire forward face of the ridge was occupied and only a knob at the lower tip was causing trouble. As evening fell a lone 105-mm. shell from friendly artillery landed short on Company E along the ridge, killing 4 and wounding 9 men, 3 of whom died later.

The next day, 22 April, the 32nd Infantry held the forward face of Skyline Ridge but made no effort to advance. Patrols, however, worked over large sections of the southern slope and one patrol reached the eastern face of Hill

178, finding few Japanese. Three sets of trench lines were found on the southern slope of Skyline Ridge, one of them at the very top. There was a maze of caves, and, though many were blasted shut, others could be examined. On the lower tip of Skyline Ridge one cave contained approximately 200 Japanese dead, another about 100, a third 50, and a fourth 45. Bodies had been neatly stacked. Altogether, about 500 dead Japanese were counted on Skyline Ridge. Most of the bodies showed artillery and mortar wounds; many others had neat rifle holes or had been burned by flame. Approximately 200 rifles, 4 heavy machine guns, and a number of knee mortars were found piled in a cave, apparently salvaged from the battlefield. These circumstances seemed to indicate that the Japanese had intended to bury their dead and use the weapons at a later time. Japanese weapons destroyed or captured on Skyline Ridge totaled 250 rifles, 4 heavy machine guns, 19 light machine guns, 20 knee mortars, a 20-mm. gun, and a 75-mm. field piece.

On the night of 22-23 April Skyline Ridge was well covered by enemy artillery. On 23 April the 32nd Infantry remained on the north slope of the ridge except when patrolling or closing caves. An enemy pillbox 400 yards away, which had survived three direct hits by a 37-mm. gun, restricted movement on the south slope until it was destroyed the following day.

The 11th Independent Infantry Battalion had defended Skyline Ridge effectively and well; for this, together with subsequent action in the vicinity of Maeda on the other side of the island, it was to receive a unit commendation from the commanding general of the 62nd Division. The battalion had only about three hundred men by the night of 22-23 April and was relieved by elements of the 22nd Regiment. This was the first appearance of 24th Division troops in front-line combat positions. The remnants of the 11th Battalion crossed the island and fought on ensuing days in the Maeda area.

During the night of 23-24 April a heavy fog set in over southern Okinawa. Under its protection, while delivering heavy artillery fire against the American front lines, the Japanese withdrew from their remaining positions around Hill 178.

The Battle of the Crags

The 7th Division’s attack against the Rocky Crags on 19 April had uncovered a formidable position. The height of the crags was such that they covered from the northwest the approaches to Hill 178. They themselves were protected by machine guns emplaced on elevated ground 200 yards east and by long-range machine-gun fire and mortars on Hill 178 to the southeast, on the Tanabaru

Escarpment to the south, and on high ground to the west. The tall, blunt coral pinnacle itself was honeycombed with caves and connecting tunnels.8

An attack against the crags on 20 April gained no ground. General Arnold then came to the conclusion that the position was the key to Hill 178. The 7th Division’s main effort was now shifted to the right, and, to give strength here, Company B, 17th Infantry, was attached to the 184th Infantry and came into the line at 1630, 20 April. After a limited advance the company pulled back to escape enemy hand grenades and dug in for the night.

Company B resumed the attack on 21 April, but it was soon stopped by machine-gun fire. Tanks and armored flame throwers then worked over the western face of the northernmost crag at close range. This enabled infantry to gain the west side of the northern crag. Just over the crest, on the other side, Japanese could be heard talking. An effort was made to move over to the east side, but the first man to show himself was shot through the face, and no advance was possible. A tank and infantry attack on the western face of the southernmost crag also failed. Company B fell back to its starting point of the morning.

The next day Battery B of the 31st Field Artillery Battalion rolled a 155-mm howitzer to a point within 800 yards of the crags. Here, firing against the eastern face, it quickly shot seven rounds. Great chunks of coral were blown loose. The Japanese swung a machine gun on the howitzer and raked the point of the hill, hitting two of the gun crew and pinning the remainder and General Arnold, who happened to be present at this time, to the ground.

Tanks and infantry started forward and crossed the open ground on the western side of the crags. The flame tanks moved up to the base of the southern crag and sprayed its face with great jets of liquid flame. Eight Japanese hurled themselves at the armored flame throwers with satchel charges but were cut down before they could reach the tanks.9 Immediately after the billows of black smoke had cleared, the infantrymen, who had followed the tanks closely, moved up to the base of the hill. But the Japanese again emerged from within the crag to man machine guns and to drop grenades and knee mortar shells from the coral crest. All but twelve men of the platoon were wounded in a few minutes. Another platoon, working along a ledge near the crest, was driven back in a close-quarters grenade fight. Artillery hit one of the tanks and set it on fire. At

Rocky Crags west slope was attacked by flame thrower tanks shortly before capture of the point shown above

The heart of the Japanese defenses in Rocky Crags. It had been chipped and scarred by artillery fire and demolitions directed against enemy lodged deep inside the hill

noon Capt. Charles Murphy halted the attack, planning to resume it at 1600 after reorganizing the company and evacuating the wounded.

In the meantime the 155-mm. howitzer, which had been immobilized by machine-gun fire early in the day, was moved to another position under protection of smoke. It now went back into action, firing forty-three rounds, each a target hit. The shape of the coral peak was altered, and the newly pulverized rock glistened white.

At 1600 two platoons attacked again along the west side. Three medium tanks and three armored flame-throwers led the way, shelling and burning the crag. The infantry then moved in so close to the Japanese soldiers that one could hear the enemy rifle bolts click. Enemy artillery became active and once again hand grenades and knee mortar shells were dropped on the attackers from above. In this attack 18 out of 31 men were casualties, and only 5 were left fit for duty. At the end of the day, 22 April, Company B of the 17th Infantry had been reduced to 40 percent strength as a result of two days’ fighting at the crags. At the same time elements of the 184th Infantry east of the crags had been held to virtually no gain by the network of fire from the crags and supporting positions.

With Company B exhausted, the remainder of the 1st Battalion of the 17th Infantry took up the attack on 23 April after the crag had been pounded once more by all available weapons and burned by the flame tanks. There was almost no opposition. At 1030 the Rocky Crags were in American hands. The price had been 186 casualties in four days to the 3rd Battalion, 184th Infantry, and 57 casualties in two days to Company B, 17th Infantry – a total of 243 men.

The Fight for Nishibaru Ridge

To the west of the 7th Division, in the center of the line, the 96th Division was having a difficult time.10 (See Map 30) Early on 20 April the 1st Battalion, 382nd Infantry, fought off an attempt by the Japanese to wrest from them the toe hold gained the day before on Tombstone Ridge. The 3rd Battalion relieved the 1st at 0730 and attacked south from the northern part of Tombstone Ridge. Company L ran into trouble at a small, tree-covered, conical hill just east of the southern end of Tombstone Ridge. A bitter fight lasting all afternoon took place there. The Japanese held firm and finally even counterattacked with bayonets through their own knee-mortar fire. Company L withdrew at 1700 after suffering thirty-two casualties. On succeeding days this particular Japanese

strong point was to hamper operations against Nishibaru Ridge. Meanwhile Company I fought down the length of Tombstone Ridge, wiping out the enemy in caves and tombs, and reached the southern end in time to help Company L by supporting fire. But because of the strong point in front of Company L the battalion was unable to cross the draw between Tombstone and Nishibaru Ridges.

The 3rd Battalion, 382nd Infantry, .having drawn abreast at the southern end of Tombstone Ridge, and the 1st Battalion, 381st Infantry, in position to the right (west), attacked Nishibaru Ridge at 1100. The attack, launched without artillery support, surprised the Japanese, and Companies A and B were on the crest of Nishibaru Ridge at 1125. The inability of the 3rd Battalion of the 382nd to cross the draw from Tombstone Ridge left the 1st Battalion of the 381st exposed on the left. Company C of the 1st Battalion, ordered up to protect this exposed flank, was met by heavy enemy fire and suffered many casualties in the three and a half hours it took to cross the draw, but at 16oo it was abreast of Company A on Nishibaru Ridge. During the afternoon the commander of Company A was killed; only four officers were left in the three rifle companies now on the northern slope of the ridge.

The success of the 1st Battalion of the 381st in reaching Nishibaru Ridge led Colonel Halloran, the regimental commander, to order the 2nd Battalion of the 381st to attack at 13oo and come abreast on the right. Japanese guns on the tip of Kakazu covered much of the ground over which the attack had to be made, and the platoon nearest Kakazu lost half its strength in crossing the 250 yards to Nishibaru Ridge. The 3rd Battalion, 381st, still farther over on the division right, was unable to move at all because of the bypassed Kakazu position. Spigot mortar fire was heavy all day in the Nishibaru Ridge area, for it was here that the Japanese had one of their main concentrations of these huge mortars.11 In the afternoon one of the big “flying boxcars” lazily wobbled down into the midst of Company E, 381st Infantry, on the northern slope of the ridge, killing four and wounding six men.

Severe punishment was meted out to the 2nd Battalion of the 381st, exposed on its right flank to automatic weapons fire from Kakazu Ridge and to a heavy mortar barrage, but Companies E and G held firm. By nightfall the 96th had five rifle companies dug in along the northern slope of Nishibaru Ridge.

The tremendous explosions of the spigot mortars, the showers of knee mortars, and the drumming of enemy automatic fire caused many cases of combat

fatigue during the day. In the fighting of 20 April both the 96th and the 27th Divisions suffered more casualties than did the Japanese. This was the only time during the campaign that American casualties in two army divisions exceeded those of the enemy facing them.12

In the fighting for Nishibaru Ridge maneuver was difficult. On the division left flank, enemy positions in the Rocky Crags dominated the 2nd Battalion, 382nd, and limited activity to patrols. On the division right flank, Japanese fire power located on the tip of Kakazu Ridge in the 27th Division zone immobilized the 3rd Battalion, 381st Infantry. This meant that the division’s effort had to be made in the center. The foothold gained on 20 April on the western part of Nishibaru Ridge indicated that the logical move would be to attack to the left (east) along the ridge from the positions already gained.

The 1st Battalion, 382nd Infantry, replaced the 3rd Battalion, 382nd, at the southern end of Tombstone Ridge, and at 0720, 21 April, the latter began a circling march to the rear and westward to reach Nishibaru Ridge through the 381st Infantry. Once on the ridge to the left of Company C, the battalion reorganized and attacked eastward. It gained ground steadily until 12, 45, when the first of three Japanese counterattacks struck. The first counterattack, of platoon strength, was beaten off. A second counterattack, of company strength, was launched at 1330 from the village of Nishibaru and developed into a bitter close battle. Lt. Col. Franklin W. Hartline, battalion commander, went from company to company encouraging the men. The heavy machine guns of Company M were carried up the steep northern slope and aided greatly in beating back the attack. The tripod of the first gun had just been set up when the gunner was killed. S/Sgt. David N. Dovel seized the weapon and fired it from the hip, dodging from one point to another to escape knee-mortar fire. A short distance away another gun was set up, but it was hit almost immediately and put out of action. The gunner, Sgt. John C. Arends, and 1st Lt. John M. Stevens then took BAR’s and dashed over the crest, firing point-blank into the attacking enemy. The weapons platoon leader of Company I was killed while directing fire from his mortars, which were only thirty-five yards below the crest of the ridge. At another point American 60-mm. mortars used an elevation of 86 degrees to fire on Japanese knee mortars only 30 yards away. In repulsing this counterattack the 3rd Battalion, 382nd Infantry, killed approximately 150 Japanese.13 A

Nishibaru escarpment area, which the 96th Division took

On 21 April the 3rd Battalion, 382nd attacked eastern end of Nishibaru escarpment by moving through the 381st’s zone to the ridge, then turning east. Men of the 3rd Battalion are shown moving forward in support of this attack

third counterattack at 195 from Hill 143, 400 yards south of Nishibaru, was easily stopped. During the day the 3rd Battalion, 382nd, accounted for 198 of the enemy. The 3rd Battalion, 383rd Infantry, had tried to come up on the left of the 3rd Battalion, 382nd, while the latter was under counterattack to give help, but hidden machine guns and mortar fire had stopped it at the gorge.

On the right portion of the division’s center, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 381st Infantry, undertook a coordinated attack at 0630, 21 April, to capture Nishibaru village. The 1st Battalion was on the left and the 2nd Battalion was on the right. Because the slope of the ridge was too steep to negotiate, tanks could not be used. The 1st Battalion and Company E on its right had just cleared the crest of Nishibaru Ridge when they were stopped in their tracks by intense enemy fire. Company G, on the right of the two battalions, moved down to the southwest corner of the village of Nishibaru. Here it received a hurricane of mortar fire and discovered enemy troops infiltrating on its right front and massing on its left in the village. In the fight that followed, the heavy machine guns attached to Company G were fired like BAR’s, braced without tripods against a low stone wall. Cross machine-gun fire from the tip of Kakazu on the west and from the southern slope of Nishibaru Ridge to the east laced across Company G’s position. At 1400 a smoke screen was laid, and the battalion withdrew to a line just over the crest of the ridge, carrying its dead on hastily improvised sapling-and-poncho litters. At the end of the day the reverse (southern) slope of Nishibaru Ridge and the village of Nishibaru were still in enemy hands.

By the evening of 21 April the heavy casualties inflicted on the 382nd Infantry had reduced its combat efficiency about 50 percent, and it was relieved by the 383rd Regiment on 22 April. The 2nd Battalion, 382nd, having suffered little in the preceding days, was now attached to the 383rd Regiment for operational control.

The 383rd Infantry picked up the attack against Nishibaru Ridge, directing its assault against the “Gate,” a saddle in the ridge. To the left (east) of the Gate the ridge line rose again to the bold Tanabaru Escarpment. The 2nd Battalion of the 383rd, on the right, attacked at 1100 down the Ridge toward the Gate. Nishibaru, a hornet’s nest the day before, was occupied by Company E without difficulty, and Company G occupied high ground facing Hill 143 to the south. Company F, advancing against the front of the ridge, encountered heavy fire and lost four company commanders, killed or wounded, in half an hour. Satchel charges, hand grenades, and knee mortar shells hurled into the company by the Japanese forced it back beyond throwing range of the coral pinnacles.

The 3rd Battalion, attacking the Gate on the left, made no appreciable gain. Of one group of ten men, including the Company L commander, on the side of a small hill, all were wounded except the officer. Company I, farther to the left, ran into fire from ten enemy machine guns emplaced near the Tanabaru Escarpment. The foremost platoon leader was killed just as he ordered his men to withdraw from this overwhelming volume of fire. Light tanks came up to the gorge in front of the ridge, and since they were unable to cross they remained there and poured thousands of rounds of machine-gun fire at the slope in a vain effort to silence the enemy guns.

On 23 April an armored bulldozer came up and prepared a crossing over the gulch. Medium tanks of Company B, 763rd Tank Battalion, then crossed over and took the ridge and the Tanabaru Escarpment under direct attack. Armored flame throwers joined in the assault and burned the north face of the escarpment and the slope of the ridge as far west as the Gate. The infantry made only limited gains despite the effective work of the armor. The Japanese held out on the high points and repulsed the attacks by grenades and satchel charges. Elsewhere in the division zone the fighting tapered off sharply.

It was clear on the evening of 23 April that the Nishibaru–Tanabaru line was nearly broken. Four battalions were on the ridge line, and all the high ground had been occupied except the Tanabaru Escarpment and the extreme western part of Nishibaru Ridge opposite the tip of Kakazu. These were taken the next day with ease because the bulk of the Japanese forces had withdrawn to the south.

The Battle of the Pinnacles

The long, high Urasoe–Mura Escarpment was a natural defensive position that became progressively more difficult to breach eastward from the coast. Toward the middle of the island it was higher and its northern face was almost sheer cliff. This part of the escarpment fell within the left end of the 27th Division zone and continued on into that of the 96th Division. The village of ISO, which lay just beyond the crest of the escarpment, was a key Japanese defensive position occupied by the 21st Independent Infantry Battalion and by elements of the 1st Heavy Mortar Regiment, armed with spigot mortars. On 20 April the Japanese 64th Brigade took over the line from the crippled 63rd Brigade as far east as Nishibaru. Its troops, deployed from the west coast eastward, consisted of the 23rd, the 21st, the 25th, and the 273rd Independent Infantry Battalions. The 4th Independent Machine Gun Battalion, cooperating with the 22nd Antitank Battalion,

supported the 62nd Division in the Kakazu–Ginowan area. In the fighting from 19 to 22 April the 4th Independent Machine Gun Battalion was to be more successful than at any other time on Okinawa.14

The heart of the defensive network around Iso was a high, rocky pinnacle, designated “West Pinnacle,” which rose from forty to fifty feet above the ridge itself, just northeast of the village of ISO. Studded with caves, crevasses, and scores of little nooks and crannies, this pinnacle was difficult to approach from any direction and was impervious to artillery and mortar fire. Tunnels branched out from it in all directions; some emerged in ISO, others as far away as 200 yards to the west. The other strong point was a towering height on the escarpment, the “East Pinnacle,” located from 450 to 600 yards southeast of the West Pinnacle. The crest of the escarpment here was hollowed out with burial vaults, most of which had courtyards in which the Japanese had carefully placed machine guns interdicting all approaches. Midway between the two pinnacles a road climbed to the top of the escarpment and cut through the crest in a sharp turn. A strong road block filled the cut, and the road itself was mined.15

On the night of 19 April the 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry, was on the top of the escarpment, spread around one end of the West Pinnacle. The 2nd Battalion, 105th, was not on top of the escarpment but joined the 3rd at the road cut through the ridge and then bent its line eastward down the slope. On the morning of 20 April heavy fighting developed quickly around the two pinnacles. Colonel Winn, 105th regimental commander, ordered his 2nd and 3rd Battalions to continue the attack south after the 2nd Battalion came up on the escarpment abreast of the 3rd Battalion. Enemy guns from the pinnacles, however, interdicted the crest of the escarpment in this area and the 2nd Battalion was unable to reach the top. Colonel Winn came up to look over the situation, and at 1200 he ordered the two battalions to attack at 1230, regardless of fire conditions. Colonel Winn himself organized the 2nd Battalion and launched an attack by a new route. Company E was left to attack as before, but Companies F and G were sent along the base of the escarpment to a point beyond the East Pinnacle, where they turned west and scaled the cliffs to reach the top north of the village of Nakama. Both companies immediately started south down the reverse slope toward a road at the bottom. In this rapid movement they approached the Japanese in the area from the rear and surprised them. (See Map 31.)

At the road both companies halted, F on the left and G on the right, to organize for an attack on Nakama to the south. While the two company commanders were discussing by radio the tactics to be used in the attack, Company F received the first blow-an intense mortar barrage that fell on its left flank, nearest Nakama. Japanese could be seen swarming through the town. After half an hour Capt. Edward C. Kidd, commanding Company F, radioed Capt. Louis F. Cudlin, who commanded Company G, that the enemy was working around Company F’s left flank and into the rear. The two company commanders decided to pivot their lines to face eastward to meet the threat. From his position Cudlin could see only part of one platoon of Company F. He decided to make the shift when these men changed position.

Just after the two company commanders finished their radio conversation, Captain Kidd was wounded and his radio destroyed. Machine-gun and mortar fire was now coming from directly behind Company F. Within only a few minutes all the remaining officers and most of the noncommissioned officers were killed or wounded. Without leaders and smothered with fire, Company F lost all organization and most of the men ran for the edge of the escarpment. But the little group out front on the right in view of Company G was oblivious to what was happening behind them; it held fast and fought on, and the Japanese soon turned their attention to them. Shortly the group discovered that they were all alone, and one of them came running over to Captain Cudlin, shouting, “Where the hell is F Company?” This was the first inkling Cudlin had that anything was seriously wrong.

Captain Cudlin immediately ordered his platoon leaders to execute the swinging movement to face east, but it was too late; Japanese were already closing in on his right rear from the East Pinnacle, and the force which had just finished off Company F was closing in from the other side. The two assault platoons of Company G were deployed along the forward (south) edge of the road, which was cut into the reverse slope of the escarpment. The north side of the road was a 6-foot embankment, and in trying to escape the men had to dash across the road, scramble up the embankment, and then climb a 100-yard slope that ran at a 35- to 50-degree angle to the top of the escarpment. Enemy machine guns set up on either side swept this ground with enfilading fire as soon as the first man started back. Mortars and grenades filled the area with flying metal fragments, and enemy riflemen fired as fast as they could reload. In the dash up the slope some of the men were killed and others wounded; still others dropped down to hide behind rocks and bushes.

The 3rd Platoon and the machine guns had been left on the edge of the escarpment when the two assault platoons of Company G moved to their advanced positions. Disorganized elements of Companies F and G now fell back through these men. It was discovered at this time that Japanese had infiltrated to the low ground below the escarpment on the north, and this added to the prevailing consternation. The Japanese, now in a good position on the flanks along the escarpment, set up a merciless fire on the men stampeding down the cliff. Men were hit and fell to the bottom to lie still; others stumbled and went sprawling headlong to the ground below. Still others, running with all their might, reached the lines of the 1st Battalion, which had come up and had faced east to meet the Japanese. Companies F and G had been completely surrounded and badly mauled by enemy from the bypassed East Pinnacle and by Japanese, estimated at two companies, who had turned Company F’s left flank.

The 3rd Battalion, 105th, with the 1st Battalion, 106th, abreast, had meanwhile, after some initial delay, advanced without too much opposition some 200 yards southwest of Iso and had taken up positions there for the night.

During this disastrous day the 2nd Battalion lost fifty men killed and forty -three wounded, nearly all of them in Companies F and G. Total casualties of the 27th Division on 20 April amounted to 506 men-the greatest loss for an Army division during any single day on Okinawa.16

On the next day, 21 April, the struggle for control of the escarpment continued, still centering on the fight for the two pinnacles. The 1st and 2nd Battalions, 205th Infantry, were reorganized overnight and operated against the East Pinnacle. Both the 3rd Battalion, 105th, and the 1st Battalion, 106th, turned back to deal with the West Pinnacle. Neither of these efforts met with success. At one time four different groups were working on the West Pinnacle, while a Japanese sniper sat somewhere in the folds of coral, picking off men one by one.

The day, however, saw one definite improvement. On the day before a Japanese officer had been killed and a map was found on his body showing the location of mine fields on the road from Machinato to the top of the escarpment. By 0900, 21 April, the road was cleared of mines and a supply line opened as far as the road block on top of the escarpment, and by noon the road block itself had been removed. At 1400 tanks went through the cut, and armor was at last on the escarpment. In the meantime the problem of supplies on the crest of the

The Pinnacles, center of the 27th Division’s fighting on Urasoe–Mura Escarpment

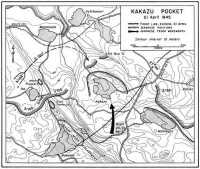

Map 5: Kakazu Pocket

escarpment had become critical, and air drops for the 2nd Battalion of the 106th Infantry were necessary on 21 and 22 April.17

On 22 April the 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, supported by self-propelled guns of the 106th Cannon Company, which moved over a path prepared by an armored bulldozer, systematically searched out and destroyed enemy positions in its rear along the escarpment. Japanese soldiers were still hidden somewhere in the West Pinnacle, which the enemy used as an observation point and as a control center for spigot mortar fire. But the enemy machine guns behind the lines at this point had been destroyed, and supply lines to Iso were for the first time free from serious harassing fire. The 1st Battalion, 106th, now had pulled back 600 yards to straighten and shorten the lines along the escarpment

and to establish contact with the 105th Infantry on the east. In the 105th Infantry zone, Colonel Winn continued to reorganize the 1st and 2nd Battalions.

On 23 April two assault companies of the 1st Battalion, 105th, which had relieved the 2nd Battalion, climbed on top of the escarpment to the east of the East Pinnacle in much the same manner as had the 2nd Battalion on 20 April, and similarly caught the enemy by surprise. Company C reached the crest of the escarpment at the edge of the East Pinnacle stronghold and found itself in the midst of the enemy. A wild hand-to-hand fight ensued in which bayonets, clubs, and grenades were used, and more than a hundred Japanese were killed within an hour. S/Sgt. Nathan S. Johnson led the battle and was himself credited with killing more than thirty of the enemy. On one occasion he jumped over a small mound of earth and found himself among a dozen Japanese. He killed eight with his rifle and clubbed the other four to death.18 At the end of the day the 27th Division held the escarpment as far east as the edge of Nakama, the division boundary.

The end of the West Pinnacle fight came abruptly, on the night of 23 April. Precisely on the hour of midnight the enemy bugler within the pinnacle, who had in previous days and nights frequently sounded his bugle as a signal, blew a call, and thirty Japanese soldiers emerged in a wild yelling banzai charge, rushing straight into the lines of the 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, dug in south of Iso. There they were wiped out.

The Kakazu Pocket

On 20 April, while the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 105th Infantry, were involved in the disastrous battle on the escarpment, it was left to the 1st Battalion to mop up the Kakazu Pocket. All three rifle companies of the battalion were involved by noon in a grim fight for the village. The 96th Division had complained about the bypassed Japanese stronghold on its right flank, and General Hodge, XXIV Corps commander, had ordered General Griner to have Kakazu Ridge cleared by nightfall.19 By 1635 the 1st Battalion had fought its way to the western edge of Kakazu village and had swept Kakazu Ridge almost to its eastern tip.

Just when it seemed that the 1st Battalion, 105th, might be able to clear the Kakazu Pocket, it was ordered to the escarpment to support the 2nd Battalion and prevent a break-through. Company A was left behind to clean up the village of Kakazu. A 16-man patrol went into the village and passed through its rubble-strewn

streets without receiving a shot. At 1700 it reported to Colonel Winn that there were no enemy troops in Kakazu. He was not satisfied for he could hear small-arms fire from the direction of the village, and he instructed Capt. Louis F. Ackerman, commander of Company A, to make another check of the village. The patrol was not fired on as it retraced its steps toward the village, but Captain Ackerman had barely stepped into the street when he went down with a shot in the back. Four men in succession were killed trying to rescue him, and then the entire patrol was scattered. Only one man returned that day, although three other survivors were rescued on 24 April. Kakazu was still a death trap.

During the night of 20-21 April, Japanese in large numbers came from the escarpment, moved around the left flank of the 27th Division, set up mortars and machine guns in the Kakazu area, and occupied the pocket in strength.20 this increased opposition the division Reconnaissance Troop slowly fought its way toward the village of Kakazu and reached its edge at 1145, 21 April: There the entire troop was pinned down, and a platoon of tanks was called up. In three more hours of creeping and of fighting into the rubble of Kakazu only fifty yards were gained. The troop then pulled back, and at 1600 division artillery placed mass fire on the village. Later it tried to enter, but the Japanese emerged from underground and stopped it with a wall of fire. (See Map 32)

The events of 21 April in the Kakazu Pocket placed the 27th Division in a bad situation. The enemy was in force behind its lines; the division had no reserve; and there was a broad gap between it and the 96th Division. Available combat strength was stretched thin. While retiring from the front lines as division reserve, the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, was ordered into position on Kakazu West, “that damned hill,” as the men called it.21 There they had dug in by nightfall.

On the evening of 21 April General Hodge ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Bradford, Assistant Division Commander, 27th Division, to take command of operations in Kakazu Pocket with full authority to coordinate action with the 96th Division. At the same time General Hodge directed that the right-flank elements of the 96th Division should not “be moved out of their own zone except by agreement with CG 96th Div. or specific orders from this Headquarters.” XXIV Corps considered the enemy positions holding up the right flank of the 96th Division to be within the 27th Division zone of action.

During the night of 21-22 April the Japanese placed heavy artillery fire on the lines of the 105th Infantry, and before daylight they started an attack around the regimental left flank. Naval star shells illuminated the front, and naval fire was called in to break up the attack.22

On the afternoon of 22 April General Griner requested a battalion from XXIV Corps reserve to help deal with the enemy in Kakazu Pocket, estimating the Japanese force there to be at least a battalion. General Hodge ordered the 3rd Battalion, 17th Infantry, to proceed at once from the 7th Division zone on the east to the Kakazu area. In the steadily worsening situation, General Griner in the afternoon of 22 April directed the 102nd Engineer Battalion to assemble near Machinato Inlet as division reserve and to be prepared to fight as riflemen. By night, there was not only a 1,200-yard gap between the 96th Division and the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, at Kakazu, but also a gap between the 3rd Battalion, 106th, and the 1st Battalion, 105th, at the bottom of the escarpment. If the enemy broke through in either place he could cut through to the coast and the service installations in the rear. At 2000 General Griner ordered the 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, less Company F, to leave its position near Machinato and move to the left flank. With the aid of these troops the gap between the 105th Infantry and the 3rd Battalion of the 106th was closed by trio. The larger gap between divisions, however, remained open. At 2130, 22 April, the 27th Division had every rifle company committed to a defensive line that stretched southeast of Kakazu village to the west coast beyond Gusukuma.

On the night of 22 April General Hodge decided to form a special force to eliminate Kakazu Pocket once and for all. A formidable force of four battalions of infantry was assembled from the 27th, 7th, and 96th Divisions, supporting units of tanks, armored flame throwers, self-propelled assault guns, and 4.2-inch chemical mortars, and was given the mission of taking the ridge and town of Kakazu. These units were placed under the command of General Bradford, Assistant Division Commander, 27th Division, and were known as the Bradford Task Force. On 23 April plans were completed and the troops moved into place for an attack to take place the next day.

The 24th of April dawned dark and rainy after a night marked by unusually heavy enemy artillery fire. After a 23-minute artillery preparation the Bradford Task Force attacked at 0730, determined to fight its way through the Kakazu Pocket. No enemy resisted it; the Japanese had vacated their

Urasoe–Mura escarpment

Image merged onto previous page

Kakazu village, center of Kakazu Pocket, looking south to Urasoe–Mura Escarpment

Kakazu pocket area (photographed 10 July 1945), looking south

positions in the Pocket during the night. Within two hours all battalions reached their objectives. In the afternoon, adjacent battalions of the 96th and 27th Divisions dug in along the division boundary at the foot of the Urasoe–Mura Escarpment and had solid contact with each other for the first time since 19 April. On 24 and 25 April, when it was at last possible to examine the Kakazu area, approximately six hundred Japanese bodies were counted, and there was evidence of mass burials and of many dead in sealed caves.

Never again on Okinawa did the Japanese have such an opportunity of inflicting major damage on the American Army as in the period from the evening of 19 April through 22 April in the Kakazu area. That they could not take advantage of it was due to the fact that almost all their infantry reserves were in the southern part of the island. A landing feint off the Minatoga beaches simultaneously with the attack of 19 April had been designed to keep them there.23

The First Lane Falls

The ease with which the Bradford Task Force gained its objectives the morning of 24 April was no isolated phenomenon. On the eastern side of the island the 7th Division walked up to the top of Hill 178 with only a few scattered, random rounds of artillery dropping in the area. There was no small-arms or automatic fire. All but a few enemy bodies had been removed or buried; the usual litter of war was largely missing and weapons and stores had been removed, indicating a planned and orderly withdrawal. (See Map 33.)