Chapter 7: Personnel Management

The proportion of civilians to military in the Chemical Warfare Service was far higher in World War II than in World War I.1 In November 1918 there were only 784 civilians in the CWS as compared to 22,198 military, a ratio of 3.5 percent. During the peacetime period a marked change took place, the number of civilians usually exceeding the military. (See Tables 2 and 3.) The combined total of civilian and military personnel in the 1920s and 1930s was not large, so that personnel management functions presented no particular difficulty. As the Chief, CWS, himself phrased it in the spring of 1937, “The personnel duties devolving upon the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service, are not now onerous.”2 The Personnel Office, OC CWS, was staffed with one officer and one civilian clerk.

The situation began to change in the emergency period. From 1939 on there was a rise in both civilian and military personnel rolls, until a peak was reached in late 1942 for civilians, and in late 1943 for military. The greater increase, as might be expected, took place in the military rolls. However, as already mentioned, the proportion of civilians to military in World War II was far higher than in World War I. In December 1942 the number of civilians was 46 percent of the military, in December 1943, 36.5 percent, and in December 1944, 36 percent of the military.

Procurement and Assignment of Officers

In World War I the CWS obtained officers by transfer from other branches of the Army and by direct commissioning from civilian life. The

National Defense Act of 1920 set up a quota of one hundred officers, in addition to the Chief, for the CWS as the best possible estimate under the uncertain conditions which then prevailed. This quota, which in actual numbers was not obtained until 1940, was filled mainly by officers who had served successfully in the CWS in World War I. The background of these officers varied. Some had had scientific training and experience before entering the Army while others were military specialists. The CWS had a need for both.

As vacancies arose through attrition during the peacetime years, they were filled by details or transfers into the CWS from other arms and services, particularly the Coast Artillery Corps. In selecting such replacements it was the practice of the Chiefs of the CWS to select individuals having at least excellent military ratings3 without special regard to technical qualifications. It was scarcely feasible to attempt to recruit scientific specialists from other branches of the peacetime Army. It became the policy, therefore, to rely on civilian scientists and engineers for developing the more technical aspects of the CWS program, under the general direction of officers who proved qualified to supervise research and development activities. In order to carry out the program more effectively, CWS detailed selected officers for two-year courses at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Wisconsin.

All CWS officers, including in some instances those who supervised research and development work, received a variety of assignments in the course of their military careers. They were required to train and command troops, to serve as Special Staff officers in the field, to supervise procurement and supply activities, and on occasion to fill miscellaneous jobs listed as War Department overhead. The variety of assignments in the Chemical Warfare Service was wider than in most branches of the Army, and some otherwise good officers could not adapt themselves to the system. Undoubtedly there was greater need for specialization in officer assignments and from the mid-r930s on the CWS followed that policy. By the time of the emergency, CWS officers were generally classified as specialists in military field assignments, in research, or in procurement and supply. Of course the limited activities of the peacetime years restricted the degree of specialization. This was particularly true in the realm of procurement. The emergency brought to the CWS a desperate need for officers with industrial experience. Since Regular officers were not available in sufficient numbers, the CWS

met the need by assignment of qualified Reserve officers and by direct commission of civilians with the necessary qualifications.

In addition to its relatively few Regular Army officers the CWS had a number of Reserve officers, who were generally assigned or attached to chemical regiments stationed throughout the country. In 1939 these Reserve officers totaled 2,100.4 As the need became critical these officers were called to active duty. Unfortunately many could not pass the physical examination and were eliminated. From 1940 to 1942 the War Department effected transfer of Reserve officers from other branches under a procedure whereby The Adjutant General’s Office circulated to the various arms and services the names and qualifications of especially able officers. In this way the CWS obtained some seventy officers, ranging in rank from second lieutenant to lieutenant colonel. But these sources did not come anywhere near filling the requirement for officers in the war period. The extent of the problem which the CWS faced in procuring officers may be gauged by a consideration of the number of officers who came into the service in the war years. In late 1943 this figure reached a peak of over eight thousand—in contrast to the less than one hundred Regulars of the peacetime years.

Civilians with proper qualifications provided an important source of officer procurement in 1941-42. The Personnel Division of the Chief’s office and the procurement district offices carried out a program of contacting industries where qualified civilians might be available. Pamphlets listing the specifications of CWS officers were compiled and circulated. In this way numerous civilians were attracted to the Chemical Warfare Service and granted direct commissions.5

Another source of officer material was the Army Specialist Corps, fostered by the Army as a means of building up a quasi-military corps of scientific, technical, and administrative personnel.6 This corps was activated in the spring of 1942. Its members, many of whom had minor physical

Maj. Gen. Dwight F. Davis, Director General of the Army Specialist Corps, with Lt. Col. William E. Jeffrey. Both are wearing the ASC uniform, distinguished by buttons and insignia of black plastic.

defects, wore uniforms similar to those worn by the military, but the corps was civilian and not military. The program was discontinued in the fall of 1942 because it did not prove practical. During its existence some fifty Specialist Corps officers were assigned to the CWS, many of whom were integrated into the service as Army officers, upon the corps’ deactivation.

After its establishment at Edgewood in early 1942, the Officer Candidate School became the chief source of officers so far as sheer numbers were concerned.7 Graduates of the OCS were commissioned second lieutenants and were usually assigned to CWS units. Other assignments of CWS officers were to installations, to training centers, and to the Office of the Chief.

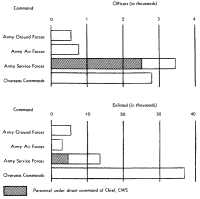

A good many chemical warfare officers were assigned or attached in the zone of interior to the Army Ground Forces, the Army Air Forces, and the Army Service Forces. (Chart 10)8

The assignment of officers within the CWS was a function of the Office of the Chief. General Porter personally assigned the commanding officers of installations and members of his own staff, while commanding officers of installations were responsible for the selection of their subordinates through the Personnel Division, OC CWS. Although the commanding officers could not always obtain the officers they wanted, the situation was certainly not as bad as some commanders alleged. There developed a tendency in one or two installations to explain all administrative deficiencies on the ground that it was impossible to obtain the services of qualified officers. The evidence does not support this contention.9 The trouble was not so much that qualified officers could not be obtained, although at times this problem did exist, but rather that there sometimes was a lack of appreciation of the potentialities of the officers on hand.

Promotion, Decorations, and Allotments

In order to assist the Personnel Division of his office in carrying out its functions, General Porter in the summer of 1942 appointed a Promotion and Decorations Board composed of the executive officer of his office and the chiefs of the Field, Industrial, and Technical Services.10 Following the publication of the very important ASF Circular 39, II June 1943, the Chief, CWS, appointed a second board, known as an Allotment Board, to deal with the allotment of civilian and military employees to CWS units and installations. This Allotment Board consisted of the executive officer, the two assistant chiefs of CWS, the chiefs of the Control and Personnel Divisions, and a recorder from the Personnel Division who had no vote.11 On 13 August 1943 the functions of the two boards were consolidated in an Allotment, Promotion, Separation, and Decoration Board.12

Before the creation of the Promotion and Decorations Board the administration of those activities in the CWS left much to be desired. Some

Chart 10—Distribution of CWS Military Personnel, as of 30 June 1944

Source: Appendix A.

commanding officers were more prone than others to recommend promotions, and personal favoritism was all too often a determining factor. Once the board began to function effectively the situation greatly improved. The board’s jurisdiction in all its functions—allotments, promotions, and decorations—was service-wide. Allotments of officers, as well as of enlisted men,

were on the basis of quotas furnished by The Adjutant General’s Office, which the board would break down to the various elements of the CWS, such as installations, Office of the Chief, and training centers. After receiving notification of their quotas those elements would forward their military personnel requisitions to The Adjutant General through the Military Personnel Branch, OC CWS. The Chemical Warfare Service always had the prerogative, which it often exercised, of requesting higher quotas, but all such requests had to carry ample justification.

Malassignment of Officers

There were two general types of officer malassignment: the assignment of officers to duties that were not military functions; and the appointment of officers to posts for which they lacked qualifications. The criticisms of the CWS by the War Department Assignment Review Board centered chiefly around the first type of malassignment. There can be no doubt that this contention of the Assignment Review Board was correct. In many instances CWS civilians carrying out certain duties were given commissions and continued to do exactly the same work as before. The CWS took the position that circumstances beyond its control had led to the granting of these commissions, that the Civil Service Commission could not furnish qualified replacements, and that the only solution to the problem was to commission those civilians who were already on the job. Had these officers been removed from their posts, the CWS maintained, especially on the scale recommended by the review board, the results would have been disastrous.

One of the rare instances when the Assignment Review Board questioned the qualifications of CWS officers for their assignments was in the case of some dozen officers holding key positions on the staff and faculty of the Chemical Warfare School in early 1944. The review board took particular exception to the lack of experience on the part of these officers. Brig. Gen. Alexander Wilson, commandant of the Chemical Warfare School, generally agreed with this contention, although he held that the situation was not nearly so bad as one might gather from merely screening the Officer Qualification Records.13 General Wilson outlined the history of how these officers came to occupy their posts. After the war broke out, he said, the number of Regular Army officers with experience in chemical

warfare training was entirely inadequate and CWS Reserve officers, most of whom had had long experience in the field of chemistry, were placed in training posts. These officers, through experience, became expert in training and administrative duties. As understudies to these officers there were a number of other officers, recent college graduates, who had little or no practical civilian experience. In time, the older officers were assigned to overseas duty, and the only officers available to fill their places were the understudies, who, while they lacked civilian experience, had had several years of training in their present assignments.14 The CWS did not find it possible to replace those officers.

Procurement and Utilization of Enlisted Personnel

Enlisted personnel rolls expanded in approximately the same proportion as officer rolls. From a total of 803 enlisted men in June 1939, the number rose to 5,591 in December 1941 and to a wartime peak of 61,688 in June 1943. The year and a half after Pearl Harbor was the period of greatest expansion. (See Appendix B.)

The majority of enlisted men assigned to the CWS went to the training center at Edgewood, which was later moved to Camp Sibert. Relatively few men were assigned to CWS installations. The Chief, CWS, was responsible for the assignment, promotion, and movement of those men in and out of the installations and for selecting those who were to attend special schools. Enlisted personnel were customarily not retained at the installations for long, since the service used them for overseas requisitions that it was continuously being called upon to fill.

Thanks to the Selective Service system, the CWS secured a number of unusually well-qualified enlisted men.15 In June 1941, for example, there were thirty-two enlisted men with college degrees in the 1st Laboratory Company. Of these, seven had doctor’s degrees and three had master’s degrees. After activation of the Officer Candidate School, men of this caliber had opportunity to apply for admission. Many of the men assigned to the installations were very well qualified for minor administrative and clerical posts. The Chemical Warfare Center, particularly, utilized their

services. When the great demand for men for overseas duty arose in 1943, all general service enlisted men were transferred from zone of interior installations to field service for eventual shipment overseas.16 Men with varying degrees of physical disability replaced these enlisted men, but this move proved generally unsatisfactory. The situation was largely rectified when members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WRAC) were brought in as substitutes for the male personnel.

Negro Military Personnel

There were few Negro troops in the Army in the peacetime period, and prior to 1940 the number of Negro units provided for in the Protective Mobilization Plan (PMP) was decidedly limited.17 No provision was made for any Negro chemical units. In the summer of 1940 the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, recommended modification of the PMP in order to provide more Negro units. The CWS initially felt the effects of the new policy when the 1st Chemical Decontamination Company, constituted as a white company in the PMP, was activated on 1 August 1940 at Fort Eustis, Virginia, as a Negro unit.18

In the summer of 1940 the War Department still had to work out many policy details on the employment of Negro troops. These included such items as the number of Negro troops to be called for active duty, the question of whether to use Negro or white officers with colored units, and the problem of what to do about the prevailing practice of segregating white and Negro troops. On 8 October 1940 the President approved the policy to be followed during the war.19 Negro strength in the Army was to be maintained on the ratio of Negroes to the whites in the country as a whole, and Negro organizations were to be established in each major branch of the service, combatant as well as noncombatant. The existing War Department policy of not intermingling white and Negro enlisted personnel was to be continued. Negro Reserve officers eligible for active duty were to be assigned to Negro units and opportunity was to be given Negroes to attend officer candidate schools. The aviation training of Negroes as

pilots, mechanics, and technical specialists was to be accelerated, and at arsenals and Army posts Negro civilians were to have equal opportunity with whites for employment.

In conformity with the above policy the Replacement Center at Edgewood opened in 1941 with a capacity of 1,000 trainees-800 white and 200 Negro.20 Negroes were trained in approximately this proportion at Edgewood and later at Camp Sibert. Since the percentage of Negro troops in Classes IV and V of the Army General Classification Test was much higher than that of white troops, the training of Negro troops as a whole presented greater difficulties than that of white troops.21

From the spring of 1942 until the summer of 1943 seventy-five CWS troop units composed of Negroes were activated at various installations throughout the country. The seventy-five units consisted of the following: 12 chemical maintenance companies (aviation), 7 chemical depot companies (aviation), 1 chemical company (air operations), 20 chemical decontamination companies, 3 chemical processing companies, 30 chemical smoke generator companies, and 2 chemical service companies. Forty-one of those companies were eventually assigned to duty overseas.22

As indicated by the large number of Negro chemical companies, the CWS had a relatively high percentage of Negro troops. As of 30 September 1943, over 17 percent of CWS enlisted men were Negro. The CWS percentage was exceeded only by those of the Quartermaster Corps, Transportation Corps, and Corps of Engineers.23

The chemical companies to which Negroes were assigned were, with one exception, service rather than combat in nature. The exception was the smoke generator company, and even this type of company in the early period of the war was considered more service than combat. Plans at that time called for the smoking of rear areas only, and the troops were trained for that mission. But as the war progressed these companies saw front-line action. Since the men were not trained for combat conditions, at first they made a poor showing. With experience these units improved tremendously and many of them had very good combat records.

The CWS trained about one hundred Negro officers at the Officer Candidate School. Upon graduation some of these officers were assigned to

chemical units, others were transferred to the Transportation Corps and the Air Forces, and those who were surplus were placed temporarily in the officers’ pool at the Chemical Warfare Center.

There was one instance of marked unrest among Negro troops in the CWS. This outbreak, which occurred at Camp Sibert in July 1943, was occasioned by the improper advances of a white civilian clerk toward a Negro woman in the post exchange. Although the Negro soldiers showed no hostility toward their white officers, they were slow in obeying orders to disperse and return to their barracks. Perhaps the flare-up would have reached more serious proportions had the Negro troops not received assurance that the white clerk would be turned over to the civil authorities.24

Women’s Army Corps Personnel in the Chemical Warfare Service

In the summer and early fall of 1942, shortly after President Roosevelt signed the bill establishing the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, chemical officers, under ASF direction, made a study of possible employment of Waacs in the CWS.25 It was decided that Waacs might be used as replacements for enlisted men doing housekeeping duties in arsenals, as fill-ins for certain types of civil service positions where it was impossible to obtain civilians, and perhaps in chemical impregnating companies in the zone of the interior. In the course of this study the Personnel Division, OC CWS, contacted the WAAC to ascertain what the chances were of securing the services of WAAC officers and auxiliaries. The Personnel Division was informed that all existing WAAC units had been earmarked for assignment outside the CWS but that, notwithstanding this fact the CWS should submit a requisition, which would be filled if at all possible.26

On 7 January 1943 the Chief, CWS, sent his first requisition to the director of the WAAC for 160 auxiliaries to be made available at Pine Bluff Arsenal.27 The quota requested was not filled at the time because there were then not enough Waacs to go around, but early in April the first installment was sent to Pine Bluff. Faced with a serious shortage of stenographers, typists, bus drivers, and dispatchers—positions for which

civilians could not be obtained—this installation used the Waacs to fill those vacancies.28 A misunderstanding soon developed over the fact that the Waacs did not always replace enlisted men. The Waacs apparently had gone to Pine Bluff believing that such would be the case, although the correspondence between the Chief, CWS, and the director of WAAC discloses that the chief problem at Pine Bluff was the shortage of civilian personnel. Whatever the source of the misunderstanding, it became a serious morale factor at Pine Bluff Arsenal and led to a number of resignations in the summer of 1943 when the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was integrated into the new Women’s Army Corps, set up as an element of the Army by an act of Congress.29

Late in April 1943 Dugway Proving Ground became the second CWS installation to be assigned a WAAC unit, and in June Camp Detrick and the Chemical Warfare Center were assigned quotas of Waacs. Later WAC officers were assigned to the Office of the Chief, CWS, and to the Rocky Mountain and Huntsville Arsenals. The number of Wacs assigned to the CWS during the war totaled about seven hundred.30

WAC officers assigned to headquarters usually performed administrative duties such as those connected with time and payroll, with the motor pool, or with the public relations office. Enlisted Wacs assigned to the CWS, the vast majority of whom went to CWS installations, were employed in a variety of skilled and semiskilled occupations. General Porter summarized the situation well in a letter to Oveta Culp Hobby, director of the WAAC, on 5 July 1943, when he said:

WAAC enrollees at Chemical Warfare Service installations are engaged in activities of wide scope and variety, embracing both skilled and semi-skilled occupations. The more specialized personnel are performing the work of chemists, toxicologists, lawyers, meteorologists, mechanical engineers, etc. Others with technical training are surgical and veterinarian assistants, motion picture projectionists, radio and teletype operators, glass blowers, draftsmen and photographers. In addition, of course, your Corps is supplying stenographers, typists, mail, code, file, stockroom personnel, and copy clerks; court reporters and librarians.31

One interesting feature of Waac assignment in the CWS which General

Porter did not mention in his letter to Director Hobby was the employment of Waacs in chemical impregnating companies in the zone of the interior. As mentioned above, this possibility had been considered in the fall of 1942. In April 1943 the CWS conducted an experiment with sixty Waacs at Edgewood Arsenal to determine whether they could be used on the work of impregnating protective clothes with chemicals. The experiment proved successful beyond all expectations, and henceforth Waacs were assigned to those units, which for semantic reasons were redesignated “processing companies.”32

“Successful beyond all expectations” might be the phrase used to describe the reaction in CWS, from General Porter down, to the work of the Wacs. Those commanding officers and supervisors who were at first skeptical about employing Wacs on certain types of assignments, laboratory technicians for example, soon changed their minds once the young women got on the job. When in 1945 General Porter said of the Wacs, “We owe them a great debt,” he was expressing the sentiment of every commanding officer and supervisor in the CWS.33 The attitude of the WAC toward the CWS was likewise one of satisfaction. As the CWS WAC staff director, Capt. Helen H. Hart, expressed it, WAC personnel were accepted in all CWS installations “on an equal and respectful basis by the majority of CWS personnel,” and this situation, Captain Hart went on to say, “resulted in WAC CWS Headquarter Detachments having some of the highest morale among all WAC Detachments in the field.”34

The Expanding Civilian Rolls

The number of civilian employees in the Chemical Warfare Service jumped from about 7,000 at the outbreak of the war to a peak of over 28,000 in 1943.35 The breakdown of CWS personnel by designated groups as of 31 December 1944 is shown in Table 6.

Table 6—Actual Strength of Civilian Employees (Filled Positions), 31 December 1944

| Service and Grade or Other Groups | Employees |

| Total CWS | 23,007 |

| Departmental | 475 |

| Professional (P-1 through P-9) | 19 |

| Subprofessional (SP-1 through SP-8) | 1 |

| Clerical, Administrative and Fiscal (CAF-1 through 16) | 438 |

| Crafts, Protective and Custodial (CPC-1 through CPC-10) | 15 |

| Consultants without compensation,and $1 per annum or per month | 2 |

| Field | 22,532 |

| Professional (P-1 through P-6) | 542 |

| Subprofessional (SP-1 through SP-5) | 396 |

| Clerical, Administrative and Fiscal (CAF-2 through CAF-14) | 5,318 |

| Crafts, Protective and Custodial (CPC-3 and CPC-4) | 1,646 |

| Ungraded | 14,601 |

| Consultants and Experts | *29 |

Includes 3 without compensations or at $1 per annum or $1 per month.

Source: CWS 230.

One of the earliest personnel requirements in the CWS in the emergency period was for trained inspectors. The need first arose out of the educational order program under which two hundred gas-mask inspectors were trained at Edgewood Arsenal before being sent out to perform their duties at the gas-mask plants in the procurement districts.36 Later, in the summer and fall of 1940, the procurement district offices began hiring inspectors in connection with the procurement contracts they were awarding. These inspectors were sent to Edgewood Arsenal for training before assuming their responsibilities. After they had obtained experience on the job, these inspectors in turn retained newly hired apprentices.37

Another significant training project undertaken by the CWS in the fall of 1939 was the apprenticeship program. The project arose from efforts

of the Assistant Secretary of War. In a letter of 13 September 1939 to the chiefs of all the arms and services the Assistant Secretary called attention to the problem of procuring an adequate supply of skilled labor for producing munitions. Even though there were great numbers of unemployed, he stated realistically, a full use of all the skilled men then idle would still leave a large deficit for meeting the war needs. As a solution he proposed the use of apprenticeship programs and urged the supply arms and services, in their field contacts with industry, to “foster and encourage apprenticeship training by relating such training to the needs of national defense.”38 The Office of the Chief, CWS, sent copies of this letter to all CWS procurement districts with instructions that they be guided by its contents.39

The CWS worked on plans for an apprenticeship training program at Edgewood Arsenal from late 1939 on, but it was not until January 1942 that such a program was actually launched.40 At that time one hundred apprentices began courses in various crafts. Of that number only two eventually completed their training. The reason for this was not lack of ability or enterprise on the part of the young men, but rather the fact that almost to a man they were inducted into the armed services under the Selective Service Act. The one apprentice not inducted did finish his training. Another who returned to Edgewood as a regular employee after the war also finished his apprenticeship. On the basis of the record, the apprenticeship training program at Edgewood was anything but a success, especially in view of the fact that some of those apprentices had spent two years studying their crafts.41

As serious as the problem of obtaining suitable employees at Edgewood was the problem of retaining them once they had been hired. The chief source of difficulty was the wage rate system of the War Department. For a number of years the War Department had made efforts to keep the wage rates of its employees in line with localities where its installations were

situated through the appointment of boards to survey wages. Such surveys had been made in Edgewood in April 1925, August 1929, and November 1939.42 But the surveys could not keep up with rising wages in industry, and by the spring of 1940 the rates were again out of line. The CWS began to encounter the problem after its construction program got under way in the fall of 1940. Skilled and semiskilled workers began leaving government employ to work for private construction companies on the post, whose wage rates were about 50 percent higher than the government’s. Later the same thing happened at Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals.

Not only was the CWS losing employees to industry because of wage rates. It was also losing them to other nearby government installations. For, surprisingly, there was no uniform wage rate system throughout neighboring government installations, and employees were leaving Edge-wood to accept higher rates of pay for the same type work at the naval installation at Bainbridge, Maryland, and at the Aberdeen Proving Ground.43

In the summer of 1941 the Personnel Division, OC CWS, requested the U.S. Employment Service (USES) to survey the situation at Edgewood. The USES readily complied and set up a wage scale of unclassified positions. This system did not prove satisfactory chiefly because the CWS did not have enough people trained to administer it. In the fall of 1941 the commanding officers at Edgewood and other CWS installations requested and received permission to raise the wages of their civilian employees. This they did by raising the grades of the laboring, craft, and mechanical positions (so-called upgraded), a procedure which led to trouble later on. What they should have done was to adjust the wage rates for all positions, white collar and ungraded, to conform to the percentage rise in general wage rates in the area. The grades of the jobs represented relative differences in skill levels, and by raising the grades for some jobs and not for others due recognition was not given to skill differentials. Since each installation was given authority to make its own grade adjustments, the entire wage structure soon became illogical and unworkable.

Late in December 1941 the Chief, CWS, in an effort to disentangle the wage rate situation, requested the director of personnel of the War

Department to appoint a specialist in wage administration to the CWS.44 This request was given favorable consideration. A civilian wage specialist, Floyd Van Domelen, was commissioned in the CWS and assigned to the Personnel Division of the Chief’s office in May 1942. He set to work immediately to draw up a wage rate plan, a task he completed by August 1942. The CWS was about to put the plan into operation when the ASF issued a directive to set up a wage administration system throughout its entire organization. In compliance, the CWS refrained from putting its own plan into operation and participated instead in the over-all ASF plan.

The ASF wage administration plan called for the activation of a Wage Administration Agency whose authority included setting wages for the laboring, craft, and mechanical employees in the field installations.45 This agency was set up, and under its direction the CWS established alignments called ladder diagrams in each of its installations. These ladder diagrams set up the positions which were not subject to the Classification Act of 1923, as amended—laboring, craft, and mechanical positions—in accordance with the difficulty and responsibility of each job. The Wage Administration Agency then surveyed the wage rates in industrial establishments in the vicinity of each installation to determine the prevailing rate for each particular type of position and the resulting wage schedule was applied to the installation. The Wage Administration Agency collected its data on local wage rates through locality wage survey boards which it set up in the service commands. Representation on these boards was not confined to a single arm or service, but various appropriate elements of the ASF were represented. For example, the Locality Wage Survey Board which was activated at Aberdeen Proving Ground in the fall of 1942 under the commanding general of the Third Service Command had a CWS representative from Edgewood Arsenal.46 In the opinion of perhaps the most competent authority on wage administration in CWS, the ASF methods of handling the wage problem were far superior to previous methods.47 Once the new system began to function, other arms and services were no longer able to outbid the CWS for employees. The Navy still could, of course; over-all reform had to wait until a later day.

Administration From Washington

The activities of the emergency period led to an increase in the number of employees in the Chief’s office. About a dozen civilians were added to the rolls as a result of the educational order program. Several of these were engineers and the remainder were clerk-stenographers.48 During 1940 and 1941 the number of new employees continued to increase, so that by the time war was declared there were over 250 civilian employees in the overcrowded CWS headquarters offices in Washington. Included were employees with specialist, professional, and clerk-stenographer ratings. During the war this number was to be multiplied several times. In November 1942 the figure reached a wartime peak of 675 civilian employees. From then until the close of the war there was a progressive decline in numbers. (See Table 3.)

The advent of war brought about a revolutionary change in the functions and responsibility of the CWS in regard to personnel administration. Before Pearl Harbor the War Department procured, appointed, classified, and promoted all civilians. The only function left for the CWS was assignment. This procedure was too time-consuming and unwieldy for wartime. A week after the December attack, General Porter requested the Secretary of War to grant him authority to handle all civilian personnel functions in the CWS.49 The Secretary of War answered this request, and perhaps others like it, with the issuance on 23 December 1941 of War Department orders authorizing decentralization of personnel administration to bureau, arm, and service levels. As a result of this and its other orders throughout 1942 and 1943, the War Department effected gradual decentralization to the field installation level.50

The decentralization of personnel administration from the ‘War Department to the Chemical Warfare Service necessarily brought about a considerable increase in the responsibilities of the chief of the Personnel Division of General Porter’s office. This post was occupied from 1938 until September 1942 by Col. Geoffrey Marshall. Colonel Marshall was succeeded by Col. Herrold E. Brooks who remained chief throughout the war. In

contrast to the situation in 1937, when the unit administering personnel activities in the Chief’s office consisted of one officer, whose time was “considerably occupied on other than personnel work,” and one clerk, there were in August 1944 nine officers and thirty-six civilians on duty with the Personnel Division of the Chief’s office.51 From 23 December 1941 until

September 1942 the Personnel Division of the Chief’s office was responsible for administration of civilian activities in the OC CWS, as well as for prescribing regulations for the administration of civilians in the field installations. On 1 September 1942, under War Department orders, the commanding officers of the field installations assumed authority to make appointments and to carry out practically all other personnel functions.52 From that time until the end of the war, the Personnel Division, OC CWS, acted merely as a staff agency with regard to the personnel administration and activities of the installations.

The administration of personnel functions in the Office of the Chief was handicapped in the early period of the war by a dearth of officers trained in personnel management. Since few officers with this training were available, it was necessary for officers on duty to learn through experience. Consequently it was difficult for the division to carry out all the recognized activities of a large industrial personnel organization. As the officers in the Personnel Division gained experience, the situation improved.

Recruitment of Civilian Personnel in the Office of the Chief of Chemical Warfare Service

It is ironic that when the CWS was occupying inadequate headquarters in the city of Washington in the early period of the war it could have secured all the personnel it needed, but that when the headquarters was moved to more spacious quarters at Gravelly Point, Virginia, in January 1943, it was impossible to secure a sufficient number of employees. The Gravelly Point location was chiefly responsible for this predicament. Employees living in Washington had to pay two fares—one on the bus within the city and the other on the bus between Washington and Gravelly Point —and on the average it took an hour to get to work. The shortage of personnel in the Chief’s office was not overcome until employees were able

to make car pool arrangements and until a number of civilians residing on the Virginia side of the Potomac were brought into the office.

After outbreak of war, the War Department received permission from the Civil Service Commission to recruit employees from a central pool in Washington. The Chief’s office obtained its workers from this source until the pool was discontinued in January 1943. For several months thereafter OC CWS recruited employees on its own. Workers already on the job were urged to contact any of their acquaintances who might be likely prospects. Various CWS installations were combed for any surplus stenographers and typists. Later in 1943 the ASF set up another pool, or recruiting service, which it called the Pre-Assignment Development Unit. This agency remained active until the close of the war.

The CWS had considerable difficulty in obtaining qualified accountants, fiscal experts, and statisticians through the Civil Service Commission, both for the Chief’s office and the installations. The need was met in part by dollar-a-year men and by experts from private industry who were loaned to the CWS.53

Training of Civilian Employees in the Office of the Chief of Chemical Warfare Service

As early as 10 July 1941 the Secretary of War called the attention of the chiefs of War Department bureaus, arms, and services to the importance of training civilian employees.54 Soon after Pearl Harbor a training program got under way in the Chemical Warfare Service.55 Training in the Chief’s office consisted in the main of elementary and advanced instruction in stenography and typing, in the operation of machine records and automatic punch machines, and in interoffice correspondence routing and distribution.56

Employee Relations

Employee relations, which included counseling and personal services, had been traditionally carried on in the CWS in connection with other

personnel activities, such as assignments, wage rates, and efficiency reports. Since the personnel offices supervised these functions, they felt that they should also deal with any problems arising in connection with the functions.

The theory that separate employee relations units were needed to carry on civilian personnel counseling originated in the ASF. In conformity with an ASF directive to appoint an employee counselor, General Porter brought Miss Dorothy A. Whipple, who had had experience counseling school teachers in the Detroit City school system, into his office in September 1942. Miss Whipple headed an Employee Relations Section in the Personnel Division until the reorganization of the Chief’s office in 1943. As a result of that reorganization the Employee Relations Section was raised to the status of an executive branch, where it remained for the duration of the war.57

The separation of employee relations functions from other personnel functions did not make for improved administration. In many instances the Employee Relations Section had to consult with the Civilian Personnel Branch before any type of action could be taken or recommended. This was necessary because of the technical nature of the problems arising, such as job classification matters, and because the Civilian Personnel Branch had the complete personnel record of the employee in its files. It was a mistake to have attempted the separation of the functions.

Installation Management of Civilian Personnel

The Edgewood Arsenal employed more civilians than any other CWS installation. (Table 7) The difficulty which Edgewood experienced in the emergency period and in the first year of the war in obtaining and retaining civilian workers has already been mentioned. The differences in wage rates between the Chemical Warfare Center and other nearby installations, it will be recalled, was largely overcome as a result of the work of the Locality Wage Survey Board in the fall of 1942. These results did not come overnight, however, and in early 1943 the situation was still considered so critical that Brig. Gen. Paul X. English, chief of the Industrial Division, OC CWS, proposed that Edgewood Arsenal utilize military as well as civilian employees in its plant operations.58 The chief of arsenal operations

Table 7—Peak Civilian Personnel Figures at Principal CWS Installations during World War II

| Installations | Peak figure | Date |

| Arsenals | ||

| Huntsville | 5,946 | 31 Mar 1944 |

| Edgewood | 8,886 | 31 Mar 1943 |

| Pine Bluff | 8,074 | 31 Mar 1944 |

| Rocky Mountain | 2,676 | 30 Jun 1945 |

| Procurement Districts | ||

| Atlanta | 339 | 30 Sep 1942 |

| Boston | 1,042 | 31 Dec 1942 |

| Chicago | 1,721 | 31 Dec 1942 |

| Dallas | 373 | 30 Sep 1944 |

| New York | 1,200 | 31 Dec 1942 |

| Pittsburgh | 1,331 | 31 Dec 1942 |

| San Francisco | 453 | 31 Mar 1942 |

| Depots | ||

| Eastern | 317 | 31 Dec 1942 |

| Southwest—Gulf | 633 | 31 Dec 1944 |

| Midwest—Pine Bluff | 411 | 30 Sep 1945 |

| Deseret | 532 | 30 Jun 1945 |

| Indianapolis | 319 | 30 Jun 1945 |

| Northeast | 91 | 30 Sep 1945 |

| Biological Warfare Installations | ||

| Camp Detrick | 22 | 30 Jun 1945 |

| Vigo Plant | 180 | 30 Sep 1945 |

| Granite Peak | 0 | –– |

| Horn Island | 0 | –– |

| Other CWS Installations | ||

| Dugway Proving Ground | 61 | 31 Dec 1944 |

Source: Extracted from Station Files in custody of Mr. Michael D. Wertheimer, O Civ Pers, OACofS, G-1, DA.

at the Chemical Warfare Center, Col. Henry M. Black, contended that it would not be feasible to employ military and civilian workers in the same plant, chiefly because the military would become dissatisfied with working for what they would consider a lower rate of pay, and that the prospects of obtaining a sufficient number of the military to operate the plants seemed remote.59

The problem was referred to James P. Mitchell, chief of the Civilian Personnel Division, ASF, who decided against the utilization of military personnel at the manufacturing plants at Edgewood.60 He believed that the civilian manpower situation at the Chemical Warfare Center could be improved by cooperative action between the ASF and the CWS. Toward that end Mr. Mitchell himself took the following specific steps: (1) he arranged with the Transportation Corps to make four additional buses available for service between Baltimore and Edgewood; (2) he detailed to the Baltimore area an ASF labor supply officer, who was to give every possible assistance to CWS; and (3) he directed the Civilian Personnel Division, ASF, to investigate the possibility of raising wage rates at the Arsenal Operations Department on the ground that it was a hazardous manufacturing unit. At the same time Mr. Mitchell requested the CWS to carry out the following procedures: (1) detail an officer or a civilian or both from the Chemical Warfare Center to the Baltimore office of the U.S. Employment Service with authority to interview the referrals who would be given priority, and hire those qualified; (2) keep a day-by-day record of the number of referrals, number interviewed, number employed, number rejected, and reasons for rejection; (3) maintain a daily list of new employees reporting for work and the number of separations with the reasons for separations; and (4) maintain a close check on the transportation system between Baltimore and Edgewood.61

Implementation of Mr. Mitchell’s suggestions brought a definite improvement in the manpower situation at Edgewood. But the Chemical Warfare Center had to take an additional step before it solved its labor difficulties. Never able to obtain enough male employees the installation began hiring women in growing numbers. By January 1944, 40 percent of the employees of the arsenal operations were female. At that time approximately 45 percent of all employees were Negroes.62 The same general pattern was characteristic of the other two CWS arsenals which were situated in the South, namely, Huntsville and Pine Bluff, both with a large percentage of Negro employees and female workers. Rocky Mountain Arsenal had a large

Women at Pine Bluff Arsenal assembling M50 incendiary bombs.

number of women employees but comparatively few of its workers were Negroes.

Arsenal employees were divided into the following broad categories: common labor, semiskilled mechanics, skilled mechanics, machine operators, maintenance and construction workers, chemical and mechanical engineers, production supervisors, and personnel for administrative duties such as accounting and plant protection. So far as sheer numbers went, recruitment of civilians at the Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals was not nearly as difficult as at Edgewood. Both arsenals were located in predominately agricultural areas and had access to pools of seasonal labor. Workers were available in great numbers during the agricultural off-season periods but were more difficult to obtain at other periods. The Civil Service regional offices, the U.S. Employment Service, and the War Manpower Commission cooperated in recruiting civilian personnel for the arsenals.

At times when the manpower situation was stringent, those agencies

assisted the arsenals in conducting recruiting campaigns. Advertisements were run in local papers, and employees were urged to hand out printed leaflets to their relatives and friends on the need for workers. A spectacular touch was added when airplanes dropped handbills about this need over the adjoining countryside. Recruitment of workers, in other respects, was not lacking in the elements of human interest. There was, for example, the incident at Huntsville Arsenal when, in the spring of 1943, the president of a college for Negro girls in Georgia stepped into the office of the commanding officer and offered the services of approximately one hundred young women in the graduating class. The offer was gratefully accepted. The young women from Atlanta University came to the arsenal fully aware of the rather distasteful nature of some of the work, but they did a job, which in the opinion of one qualified to judge, could hardly have been surpassed.63

Alabama and Arkansas agricultural workers, the most common type of employees readily available to the Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals, were almost entirely unskilled laborers. Although their native intelligence was undoubtedly equal to that of any similar group in the United States, they were decidedly limited in educational background. A great many, particularly among the Negroes, could not read or write, and this made for difficulties in training them for semiskilled occupations. It was impossible, because of time restrictions, to attempt training for skilled occupations. Skilled workers, technicians, and typists had to be obtained from other areas, generally from localities considerably distant from the arsenals.

The differences in the wage scales between local industry and the government, such as existed at Edgewood, were not a problem at Pine Bluff and Huntsville Arsenals. The agricultural workers who went to work at Pine Bluff and Huntsville had never before done factory work and were completely unaccustomed to the comparatively high rates paid by the arsenals. A number of the Negro women who were hired had previously been engaged as domestics at a rate very far below that of the arsenals. Most of these workers had never experienced such prosperity, a fact which was not, as far as the war effort went, an unmixed blessing. In far too many instances, employees would not work any more days in a pay period than necessary for mere existence.

Rocky Mountain Arsenal had access to a comparatively high number of skilled male workers, but to relatively few unskilled or semiskilled. For many years before the war, Denver was noted as a center for small-scale skilled industries. The advent of the emergency attracted a number of these skilled mechanics and technicians to the airplane and shipping industries on the west coast. Others remained at home, even though they were not able to carry on their trades because of shortages of raw material. Many of these skilled workers were willing to take employment only if it offered wages commensurate with the rates to which they had been accustomed. But they would not accept assignments as semiskilled workers, and consequently the arsenal had some difficulty in securing that type of labor.64 Unskilled women workers, as already indicated, were plentiful and the arsenal experienced no difficulty in filling labor requirements in that group. From late 1943 on, prisoners of war (POW’s) were used at Rocky Mountain, except in the plants area.65

In 1942, in an effort to secure semiskilled workers, the commanding general of Rocky Mountain Arsenal set up schools in Denver and the surrounding towns. Shortly after the arsenal was activated, a number of semiskilled workers were obtained from an unexpected source. The commanding general learned that sugar mill workers in the vicinity of Brighton, Colorado, had skills very similar to those required by chemical plant operators. General Loucks, commanding general of Rocky Mountain Arsenal, sent the chief of the Personnel Branch and his assistant to interview these workers. The two administrators found that they were usually occupied in their trade for a few months of the year and were very glad to go to work at Rocky Mountain Arsenal provided they were released for mill work from October to December. The arsenal readily agreed to this stipulation and the sugar mill workers were brought to the arsenal.

The centralization of personnel functions at the Chemical Warfare Center has already been referred to.66 Huntsville Arsenal also experienced the need for a centralized personnel organization, for at that installation, where all activities were highly decentralized, personnel functions were no exception to the rule. Each operating division at the arsenal had its own personnel officers who were invariably officers of company grade subject to the command of the respective division chiefs. Although there was a personnel division at headquarters, it was lacking in effective authority.

In the spring of 1944 an audit team from the Office of the Secretary of War visited Huntsville and found defects in the methods of wage administration employed at the arsenal. This discovery led to a survey by the Personnel Division, OC CWS, which resulted in a number of suggestions not only on wage administration but also on the centralization of civilian personnel functions, the substitution of civilians for military as personnel officers, and the training of operating officials in sound personnel practices. From July to December 1944 those measures were largely carried out at Huntsville and resulted in a marked improvement in personnel administration.67

At Pine Bluff and Rocky Mountain Arsenals the administration of civilian personnel functions was centralized almost from the start. At Pine Bluff the chief of the civilian personnel unit reported to the chief of the Administration Division of the Arsenal Operations Office, and at Rocky Mountain to the commanding general.

The Depots

Graded civilian employees at the depots, as at the arsenals and other CWS installations, were selected in accordance with civil service qualification standards and Classification Act salary schedules. Ungraded employees were hired on the basis of job descriptions, designations, and wage schedules approved by the Civilian Personnel Branch of the Chief’s office.

Three of the CWS depots, Eastern, Midwest, and Gulf, were closely associated with Edgewood, Pine Bluff, and Huntsville Arsenals, respectively, and were faced with identical problems of personnel procurement. The outstanding need at depots, as at arsenals, was for skilled labor. Skilled workers were just not available, and it was necessary to train apprentices on the jobs. It took some time before a satisfactory staff of foremen was functioning at most of the depots. As at arsenals, many women were hired and trained to do jobs formerly handled by men, and many Negro workers were also brought in.

At the three remaining CWS depots, Indianapolis, Northeast, and Deseret, the procurement of workers, unskilled as well as skilled, was beset with difficulties. The Northeast Depot, in the Buffalo—Niagara Falls

vicinity, was in a labor area that was critical throughout the whole period of the war. At the time the depot was activated, the ,90th Chemical Depot Company was brought from Edgewood for extended field training. This company remained for a little over a month, during which it rendered invaluable assistance in carrying out operations at the depot. The 190th Chemical Depot Company was replaced for a short time by troops of the 71st Chemical Company (Smoke Generator), but in September 1944 the 71st received change of station orders. Then, in the fall of 1944, the depot secured from the commanding general of the Second Service Command an allotment of fifty enlisted men who had returned from overseas. This experiment, unfortunately, did not prove satisfactory because of the caliber of men allotted, and very shortly the entire detachment was withdrawn.68

Although never able to obtain all the civilians it needed, the depot did secure the services of a corps of loyal and efficient workers from the following sources: (1) employees of the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works who stayed on the job after CWS took over the installation; (2) local residents; (3) seasonal employees such as school teachers and farmers; and (4) relatives of employees solicited through personal appeal.

The Indianapolis Depot was situated in an area dotted by defense plants which absorbed most of the available labor supply; in addition, two other armed forces depots in the vicinity competed with the CWS depot in procuring civilian employees. One of these was an Ordnance Department depot and the other an Army Air Forces depot. The CWS Indianapolis Depot managed, notwithstanding, to hire and train a number of civilians. In January 1945 prisoners of war provided a new source of labor.69

If the manpower situation at Buffalo, Niagara Falls, and Indianapolis was bad, it was much worse at the Deseret Depot in the remote reaches of Utah. There the labor supply was practically nonexistent, and an unusual recruitment program had to be initiated in the fall of 1943 by Lt. Col. William S. Bacon, the commanding officer. Bacon, who had had considerable experience with laborers of Mexican and Spanish ancestry, obtained permission to recruit outside the state of Utah and arranged for setting up recruiting offices in New Mexico. Experience had taught him that it was useless to attempt to employ these workers without making provisions for their families. He therefore provided for the transfer of as many married couples and children as the housing facilities at Deseret would permit. But

that was only the beginning of his project. He next had to make certain that they would remain on the job after they arrived at that isolated post. In other words, he had to provide the newcomers with the necessary shopping and recreational facilities. Under Colonel Bacon’s direction, a grocery store, drug store, notion shop, restaurants, bars, and dance halls were erected. All profits accruing from these enterprises poured back into the general welfare fund. With so little in the vicinity to attract them, few of the workers had any desire to go outside the camp and thus their services were available day or night in the event of an emergency.70 The entire project of recruiting and transporting these workers from New Mexico to Deseret was a unique and farsighted undertaking.

These workers, almost without exception unskilled, were the main source of labor at Deseret. A small number of other workers from Tooele and Salt Lake City came to work at the depot each day, after provision had been made with a public service company for their transportation.

There was no standard organization for administering personnel activities in the depots. Certain depots had no personnel units. The personnel activities of the Gulf Depot, for example, were administered by Huntsville Arsenal. The Eastern Depot had a personnel division until September 1942, when its functions were taken over by the personnel division of the Chemical Warfare Center. The other CWS depots each had personnel units.

The CWS sections of general depots were under the central administration of these depots, and therefore there were no separate personnel units at these sections. Their personnel allotments were based on the over-all allotments of the depots.

The Procurement Districts

The personnel requirements of the procurement districts included the following general categories: (1) chemists and engineers for chemical analyses and production methods; (2) clerical, administrative, and fiscal personnel; (3) inspectors; and (4) warehouse employees.

In recruiting employees, the procurement districts generally possessed certain advantages over the other types of CWS installations. All of the district offices, and even the suboffices, were located in large cities where a sizable pool of professional, skilled, and clerical labor was available. A great many of the district employees lived within easy commuting distance

of their work, and few problems of transportation arose. At the time war was declared and for about six months thereafter, there was an abundance of applicants for positions in all the procurement districts. The district office simply notified the local office of the U.S. Civil Service Commission or the U.S. Employment Service of its needs, and they were filled. A gradual deterioration set in thereafter, the result of a number of factors.

Among the most significant of these factors was the ability of private industry to pay higher wages than the government. It is ironic that in a number of instances those companies owed their prosperity to government contracts and yet they carried out recruiting campaigns which attracted employees away from government service. At times these recruiting campaigns became aggressive to the point of impropriety. Certain war contractors on the west coast for example, used the phrase “permanent jobs” in advertising vacancies; when the impropriety of this was called to their attention they obligingly changed the wording to “jobs with permanent companies.” The only recourse open to the procurement district offices, under the circumstances, was to provide for more rapid promotions and this they did.

Another factor which complicated the personnel situation was the growth in the number of field inspection offices, the aftermath of the increased number of contracts. The CWS had to make provision with the Civil Service Commission to permit chief inspectors in certain field offices to hire all personnel under blanket authorities issued by the commission. As time went on the procurement districts, like other installations, hired more and more women to do jobs formerly done by men.

In all of the districts there were units administering personnel functions. These units became more and more standardized in the wake of the district reorganizations from July 1943 to the close of the war.71

There were no personnel units at the CWS sections of the ports of embarkation or at the CWS government-owned, privately operated plants. Requests for funds to cover authorization of civilian positions in the chemical sections of the ports were forwarded through the commanding officers of the ports to the Office of the Chief, CWS. It was incumbent upon port chemical officers to supply the Chief’s office with pertinent data relating to the jobs, such as organization charts and job descriptions.72 The OC CWS, particularly the Supply Division, kept close watch on all port

activities. Personnel administration of CWS plants was a function of the procurement district in which the particular plant was located.

Employee Relations at Chemical Warfare Service Installations

The on-and-off-the-job problems of employees in the CWS were confined almost exclusively to the Chemical Warfare Center and the arsenals. Difficulties arose on such matters as housing, transportation, care of the children of working mothers, adequate eating accommodations, and recreation. The failure to solve these problems was a contributory factor to the comparatively high rates of absenteeism and turnover at certain CWS arsenals during the war.73 To reduce the rates of absenteeism and turnover, employee relations officers were appointed at the various installations in 1943.

Although employee relations problems arose at all arsenals, they came up in varying forms and degrees. For example, the housing problem at Edgewood, Huntsville, and Pine Bluff grew out of an absolute shortage of housing units, and arrangements had to be made with the Federal Housing Authority to erect housing projects near those installations. At Rocky Mountain, the housing problem was confined to arrangements made by the installation for the rental of houses to new employees.

Transportation was another problem which varied in difficulty from place to place. All the arsenals were faced with this problem, which was aggravated by the rationing of gasoline and tires. Nevertheless, the situation was more serious at Huntsville and Pine Bluff than at Edgewood and Rocky Mountain, because most of the workers at the former installations had to travel long distances over poor secondary roads.

Employee problems at the arsenals differed in degree of difficulty also with respect to the provision of eating accommodations. All the arsenals felt the need for cafeterias, but the need was more pressing at Huntsville and Pine Bluff, where many of the workers brought lunches that were not conducive to the health and strength of efficient factory workers.

An employee relations problem of considerable importance, which was always present at Edgewood, Huntsville, and Pine Bluff, was the preservation of amicable relations between members of the white and Negro races. In matters of racial segregation the prevailing cultural patterns could not be entirely ignored, particularly in view of the urgent need for uninterrupted production. Therefore the procedure was followed of accepting a

certain amount of segregation, but of providing equal rights, facilities, and privileges to both races.

Training Civilian Workers

On-the-job training was widespread during the war at all CWS installations, particularly at the arsenals and depots. Under the circumstances, it could not have been otherwise. Hundreds of new employees were being hired, mostly in jobs of a semiskilled nature, and some provision had to be made immediately for training them at least in the fundamentals. Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals had the services of a small cadre of experienced employees who had come from Edgewood Arsenal, but there were too few of these to train all new applicants. To supplement the number of instructors, the arsenals sent some of the most promising of the new employees to Edgewood for training and, upon their return, placed them as instructors to fresh recruits. Rocky Mountain Arsenal after activation was fortunate in having access to employees from all of the other CWS arsenals, employees who could act as instructors to new trainees.

Even before the new employee got to his job his training began. At the personnel office where he was hired he received instruction on his status and rights as a government worker. When he reported to the branch to which he was assigned he was instructed on the duties of his job and on matters of safety. Shortly after being hired he had the opportunity, if he was an employee of the Office of the Chief or of most CWS installations, of attending a course of about four hours’ duration where CWS equipment and products were demonstrated to a small group of new, and even perhaps some old, employees. This introductory type of training was known as orientation training.

The matter of safety was brought to an employee’s attention on many occasions, particularly if he was working in an arsenal. Practically every course and program conducted at CWS arsenals during the war included some instruction on safety.

The CWS received helpful guidance from a series of three training programs inaugurated by the ASF in August 1942, programs which had been developed cooperatively by the Army and the Industry Agency of the War Manpower Commission. These three programs, each of which covered ten hours of instruction, provided for the training of supervisors in the “basic skills of how to instruct, how to lead, and how to manage the technical aspects of their jobs” and were named respectively, Job Instructor

Training, Job Relations Training, and Job Methods Training.74 Later a Job Safety Program was inaugurated and the four programs became known collectively as the “J” series.

The “J” series led to the inauguration of training programs on a large scale throughout the ASF. Those programs expanded far beyond the “J” series and were aimed at meeting the particular needs of zone of interior installations.

Arsenal Training Programs

Because of the nature of their operations, the arsenals needed more extensive training programs than other types of installations. Typical of all CWS arsenals was Rocky Mountain, which between the fall of 1942 and the end of 1945 conducted, in addition to the “J” series, some half dozen courses. These included the following courses offered on a continuing basis: a two-week to six-week course for inexperienced chemical engineers, a one-week course in analytical procedures for new chemists, and a four-week to eight-week course at factories for instrument makers and refrigerator plant operators. The following additional courses were given as indicated: a one-month course (four 2-hour sessions per week) in chemical plant operation and safety, conducted by the University of Colorado (course was given twice), a two-month course (two 2-hour sessions per week), conducted simultaneously by three Colorado universities (course given once), and a six-week course for laboratory technicians at the University of Denver (course given once).

The training program at Rocky Mountain Arsenal, elaborate as it was, did not provide any extensive training for clerks and stenographers. There was a good reason for this, namely, that Rocky Mountain was never faced with any serious shortage of workers in these categories. At Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals, on the other hand, clerks and stenographers were at a premium all during the wartime period. Among the most important features of the training program at Huntsville and Pine Bluff was the training, on a continuous basis, of clerks and typists. The most promising candidates among the girls in the plants were transferred to the offices and trained as clerks and typists.

Since Huntsville and Pine Bluff were not situated near colleges or universities, these arsenals made no effort to carry out a cooperative training

program with private educational institutions. The Chemical Warfare Center and Rocky Mountain Arsenal were more alike in this respect. The various colleges in Baltimore cooperated with the CWS in setting up courses for its employees. At times the U.S. Office of Education also cooperated. For example, in 1945 the CWS, in cooperation with the U.S. Office of Education and the University of Baltimore, organized a fifteen-week course, two and one-half hours per week, for supervisors. By July 1945, 178 supervisors had completed this course and the results, in the opinion of the commanding officer of the CWC, were excellent.75

In the administration of the training programs some arsenals did a better job than others. Those installations with the best civilian training records followed a few basic principles which made all the difference between good and bad administration. Among these principles the following three were outstanding: (1) all supervisors were required to take certain basic instruction, such as the “J” series; (2) the commanding officer personally encouraged the training programs; and (3) there was good coordination between the military and civilian key personnel on all training matters.

Depot Training

The most extensive training program at the depots, as at the arsenals, was on-the-job training. Within six months after the declaration of war, it was impossible to hire trained workers such as crane or fork lift truck operators, and consequently new employees had to be trained on the spot to perform these operations. The same situation prevailed at all of the depots throughout the wartime period.

The “J” series was introduced into the depots at the same time as at other installations. Courses at special training schools were also initiated. From 1943 until the close of the war, selected depot employees, both military and civilian, were dispatched to the Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin, to take a one-week course in packing and packaging.76 The training of depot employees was closely supervised by the Supply Division, OC CWS. Training units were set up at those depots where

there were personnel organizations, such as the Indianapolis Depot and the Deseret Depot. At other depots such as Eastern, Midwest, and Gulf, the administration of training was the function of the training unit of the adjoining arsenal.

Training in the Procurement Districts

The most pressing manpower need of the procurement districts in the early part of the war was for inspectors. In the emergency period, as indicated above, newly hired inspectors were sent from the districts to Edgewood Arsenal for training. These employees upon their return to the districts helped train more recently hired inspectors. Once war got under way this method could not satisfy the greatly expanded need for inspectors.

To fill this need, the Chemical Warfare Service began an intensive’ drive to procure female as well as male employees. It scoured the colleges in the procurement districts for women who would qualify as inspector apprentices. Once trained, those college women did excellent work. For certain types of inspection, such as that of munitions, the training standards were lower, and a high school, vocational school, or even a grade school education was considered sufficient background. The minimum requirement for inspectors of chemicals always remained high: a college background in chemistry or chemical engineering.

The training of new inspectors was carried out in cooperation with the city and state departments of education and with various private schools. In the San Francisco district, for example, a course for inspectors was inaugurated in December 1941 in cooperation with the California State Department of Education. This course included instruction in measuring instruments and gauges, basic metallurgy as applied to inspection, and miscellaneous subjects such as principles of spring design and testing.

The state of California furnished teachers for this course. In other districts, such as Boston, training was conducted almost entirely in private educational institutions such as the Durfee School at Fall River or Northeastern University in Boston. In still other districts, like Dallas, the district training unit itself conducted training courses for inspectors; a well-qualified civilian put in charge laid out the courses of instruction, obtained suitable texts, and arranged for the procurement of training films and other training aids.77

Utilization of Employees

There was an extravagant waste of manpower in many war industries during World War II. This waste occurred not only in government plants but also in those operated by private industries. In some instances, cupidity or mismanagement or a combination of both was responsible. In a greater number of cases the cause was due to other factors, the most important being the extremely rapid expansion of the industrial facilities of the country as a result of the demand for matériel in the first year of the war. Contracts were let out to corporations or individuals who never had had experience in manufacturing the particular items called for in the contract. They had to learn by trial and error. Among other things, these manufacturers were totally unacquainted with the best methods of employing manpower in their plants, a technique they had to learn as time went on. Older government plants had a certain amount of experience, of course, in producing their particular products, but the tremendous increase in the demand for more and more of all types of items led them to place secondary emphasis on the conservation of manpower. The newer government plants, like the industries which converted to wartime manufacture, were in a more serious predicament.

The Chemical Warfare Service, like the other technical services, was faced with the problem of conserving manpower. As early as July 1942 the Commanding General, ASF, called attention to the need for better use of personnel. He informed the Chief, CWS, that many of the War Department offices were not using their employees to best advantage and urged a survey to ascertain the number and function of clerical workers by grade.78 This was the beginning of a drive by General Somervell to conserve manpower, a drive which was to continue throughout the wartime period. Time and again he reiterated, either through personal statements or through official administrative action, the necessity for efficient utilization of personnel, both military and civilian.79 In conformity with this policy great emphasis was placed on work simplification and work measurement programs throughout the ASF.80

In June 1943, it was disclosed, General Somervell had promised General Marshall that he would reduce the number of ASF operating personnel by 105,000 and that Under Secretary of War Patterson and James Mitchell, director of ASF personnel, had assured Congress there would be a cut of at least 100,000 in civilian personnel in the ASF.81 After the ASF apportioned this figure among its various elements, the Chemical Warfare Service was cut back 2,424 employees in July 1943.82

The CWS record for reducing the actual number of its personnel during the war was not outstanding. At times when many other branches and services were showing a decrease in their employment rolls, the CWS was showing an increase. But there was a very good reason behind the CWS increase: the expanded chemical warfare procurement program in the second half of the war. The CWS did not reach its peak of procurement before 1944.83 Had the war continued, the Service would undoubtedly have reached peak procurement in 1945 or later, because at the time the war came to a close the demand for items like the flame thrower and the incendiary bomb was rising.84 Although the CWS did not show a marked decline in the actual number of its employees, the CWS record in making the best use of its manpower was in the main impressive, as members of the ASF staff noted on various occasions.85

On 4 March 1943 General Porter appointed a Manpower Utilization Committee to supervise all projects aimed at conserving manpower in the CWS.86 The Control Division, OC CWS, acted as the operating agency for this committee and, through the control units at the installations, administered work simplification and later work measurement programs on a continuing basis. On 24 January 1944 the Chief, CWS, appointed a Personnel Utilization Board of five military members, headed by General Loucks, to survey the employment needs of each CWS installation and make recommendations on better utilization of personnel.87

Utilization of Personnel at Arsenals

Of all CWS civilian personnel 85 percent was engaged in activities related to procurement.88 This type of activity was the most amenable to work measurement, an operation on which the CWS put great emphasis, particularly at the arsenals. Both the Control and Industrial Divisions, OC CWS, scrutinized the personnel utilization reports of the arsenals very closely and called upon the commanding officers to explain any apparent failures to cut down the number of man-hours. In this way the arsenals became conscious of the importance of the work simplification and work measurement program and strove to make better records in their personnel utilization indexes.