Chapter 6: Field Organization of the Chemical Warfare Service

The expansion of the Chemical Warfare Service field organization which began in the emergency period of course became much more rapid once war was declared. As part of the effort to meet the demands of a nation at war and at the same time supply the United Nations with the matériel to carry on war, activities at all existing CWS installations greatly increased, and the need for new installations arose.

The Procurement Districts

Most CWS procurement in World War II was effected through contracts awarded in the procurement districts.1 The day after the United States declared war on Japan, General Porter recommended to the Under Secretary of War that the number of CWS procurement districts be increased from five to seven. He wanted to activate two new districts with headquarters at Atlanta and Dallas in order to tap the industrial capacity of the southeastern and southwestern sections of the United States. For some years War Department plans had called for the activation of a new district with headquarters at Birmingham, but General Porter argued for Atlanta rather than Birmingham on the ground that Atlanta was a more important center for industries useful to the Chemical Warfare Service. The Chief, CWS, further recommended that if the establishment of the two new districts was approved, the Atlanta district be placed immediately on a procurement basis and Dallas on a procurement planning basis for the first several months, pending a more accurate survey of the latter’s capabilities. On 17 December 1941 the Office of the Under Secretary of War approved these recommendations.2

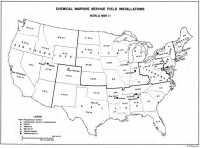

Late in January 1942 the Office of the Chief, CWS, sent Maj. Herbert P. Heiss to Atlanta to establish a procurement district office.3 A month later Col. Alfred L. Rockwood was transferred from the San Francisco Procurement District to assume command of the new Atlanta office, and Major Heiss then proceeded to Dallas to open the new office there. He arrived in Dallas on 2 March, and five days later the district was activated. With the creation of the Atlanta and Dallas districts, some of the territory formerly attached to the Pittsburgh and Chicago districts was put under jurisdiction of the new districts. The Atlanta district included the following states: Florida, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi; while the Dallas district included the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana. (See Map, page 112.) Early in 1943, Headquarters, ASF, and OC CWS decided that the continuation of the Atlanta office as a separate district office was not justified and, in April 1943, it was designated a suboffice of the Dallas district.

Of the twelve officers who were in charge of procurement districts during the war, seven were Regular Army officers and five were Reserve officers or were appointed from civilian life.4 All the Regular Army officers had training and experience in procurement planning activities before the war and several of them had attended the Harvard University School of Business Administration for two-year periods. Every one of the Reserve officers had some experience in the industrial, financial, or commercial field. Lt. Col. Robert T. Norman, commanding officer of the Atlanta district and later executive officer of the Chicago district, had been associated for fourteen years with a Washington, D. C., securities and investment house. Col. Lester W. Hurd, commanding officer of the Boston district and later of the New York district, was a well-known architectural engineer in California. Colonel Heiss of the Atlanta and later of the Dallas districts had extensive banking and industrial experience. Heiss was the only commanding officer who had come into the Army from civilian life and who had not been a member of the Reserve. Col. Clarence W. Crowell, who

Chemical Warfare Service Field Installations World War II

succeeded Colonel Heiss as commanding officer of the Dallas district, was vice president in charge of production at the Rochester Germicide Company, Rochester, New York. Col. Raymond L. Abel of the Pittsburgh district was a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh and had considerable practical experience in the field of petroleum engineering.

The United States entrance into the war brought such a vast increase in the number of contracts that the War Department decentralized authority for approval of many more contracts to the procurement districts.5 On 13 December 1941 General Porter authorized the CWS districts to negotiate contracts up to and including $200,000.6 On 3 January 1942 this authority was extended to contracts up to $1,000,000 and on 23 March this figure was raised to $5,000,000 at which level it remained throughout the war.7

The Chemical Warfare Service experienced certain difficulties in placing contracts on items other than the gas mask. Thanks to the educational order legislation, the CWS had access to the services of a number of large manufacturers experienced in gas-mask production. With other chemical warfare items the situation was somewhat different. Since the Industrial Mobilization Plan of 1939 was not put into effect, the CWS lost some well-established contractors allocated under that plan. It was necessary, therefore, to seek other potential contractors, who in many instances were small operators. While it would have been to the advantage of the government in certain cases to have had contractors with larger facilities, the small firms, generally speaking, did an outstanding job once they had converted their plants and had gained experience.8

Organizational Developments

The expansion of activities in the procurement districts necessitated a corresponding expansion of organization. Administrative units which formerly performed two or three functions were broken down into separate units. For example, in the Pittsburgh district there was a Fiscal, Property,

and Transportation Section before December 1941, but in early 1942 separate sections were activated to deal with each of those functions. In the Boston district, inspection, plant protection, and production were all under an Engineering Division until 1942 when separate sections were established. The activation of these separate administrative units would not have been possible without the increased availability of officers.

Where the ever-growing workload did not account for the activation of new administrative units, the decentralization of operations in accordance with ASF policy did. In 1942 such functions as priorities and allocations and manpower utilization were decentralized to the installations. From 1943 to the close of the war, decentralization of operations took place on pricing analysis, public relations, property disposal, contract termination, and demobilization. Units to supervise these functions were set up in the district offices and other pertinent installations.

During the opening months of 1943 the Chief of the CWS directed all installations to activate control units in their organizations to assist the Control Division of his office to carry out its functions and to conduct control functions in the installations themselves.9 He indicated the benefits which the commanding officers might expect from such units by describing the work of the Control Division of his office. This division, he stated, had recommended measures to integrate the organization and activities of the service and to reduce the number of persons engaged in administrative tasks and paper work.10 Following receipt of General Porter’s directive, all of the CWS installations set up control units.11

The outstanding accomplishment in the Chemical Warfare Service with regard to procurement district organization was the program of standardization of organization and procedures that was launched in the summer of 1943. In a letter to the commanding officer of each district the chief of the Control Division, OC CWS, stated that studies of record-keeping activities and work-simplification surveys made in the various districts indicated a marked disparity in the business practices of the districts. This resulted in certain districts utilizing more personnel than other districts to perform tasks of a similar extent and nature, an intolerable situation in the light of the manpower shortage. One step toward rectifying the

situation was the standardization of the district organizations. The chief of the Control Division of the Chief’s office compiled a tentative draft of a manual outlining a uniform organization for procurement districts, on which he requested and received comments and suggestions by the commanding officers.12

On the basis of these recommendations, together with the principles of organization formulated by the ASF, a standard organization was set up in each district in September 1943. Local conditions dictated some variations, but in most respects all districts were organized in essentially the same manner from that time until the close of the war. The Chicago District, for example, shows the standard setup as of 15 August 1944. (Chart 6)13 This organization was in conformity with ASF Manual M603 which was published in 1944. After publication of the manual, a study of the Chicago district as typical of all CWS procurement district organizations revealed that the district organization was in substantial agreement with the standards set up by the ASF.

The standardization of organization in the procurement districts and other CWS installations facilitated the standardization of administrative procedures. Before the Control Division survey of the districts, for example, each district office had its own forms and records system. This led to endless confusion in the Chief’s office, where the data coming in from the installations had to be correlated. Until the forms and records were standardized it was extremely difficult to tell in what areas progress was being made.

Procurement District Headquarters and Field Inspection Offices

Following the activation of a separate Inspection Division in the OC CWS in May 1943,14 the technical functions of the inspection offices at all CWS installations came under the jurisdiction of the new Inspection Division. The principle of divided jurisdiction was never entirely satisfactory to a number of installation commanders, who felt that since they

Chart 6: Chicago Procurement District, Chemical Warfare Service, as of 15 August 1944

were generally responsible for the procurement of items they should be responsible for the quality of the items procured no less than for the quantity.15 But the experience in the early part of the war of having the same officer responsible for both the production and inspection of items had not proved successful. The solution adopted was to take responsibility for inspection entirely out of the hands of the person accountable for production, the installation commander, and place it with an inspection officer responsible only to the chief of the Inspection Division, OC CWS.

From the point of view of operations, the system was effective because the quality of chemical warfare items improved greatly after the spring of 1943. The commanding officers of the procurement districts felt, however, that the same objectives could have been attained had the Chief, CWS, held them personally accountable for both quantity and quality of items. Such a procedure, they believed, would have avoided the administrative problems of divided authority that sprang up after separate inspection offices were activated in the districts.

Developments in 1945

Following V-E Day the Pittsburgh Procurement District was deactivated and the Boston and New York districts were consolidated under one commanding officer. This was the result of a requirement by ASF that for reasons of economy the number of CWS installations be reduced. In June 1945 Colonel Hurd, commanding officer of the Boston district, was named commanding officer of the New York district in addition to his other duties. During the preceding month, plans had been worked out to transfer part of the Pittsburgh district’s business to the Chicago district and the remainder to the New York district and to set up a suboffice of the New York district in Pittsburgh. By V-J Day the transfers had been made, but owing to the sudden ending of the war the Pittsburgh suboffice was never activated.

The Chemical Warfare Center

The increased activities at Edgewood in research, training, manufacturing, and storage had, by the start of the war, made the designation

Chart 7: Chemical Warfare Center, as of 10 May 1942

Brig. Gen. Ray L. Avery, Commanding General, Chemical Warfare Center, Edgewood Arsenal, Md., 1942–46.

Edgewood Arsenal a misnomer. Five days after Pearl Harbor, General Porter called this fact to the attention of the War Department in a letter recommending that a Chemical Warfare Center be activated at Edgewood. No action was taken on that recommendation, and on 23 February 1942 the Chief, CWS, again recommended that a center be set up under a commanding general, with several “intermediate” commanders to supervise the functions of research and development, training, and manufacturing. On 6 May 1942 the Secretary of War approved the recommendation, and four days later the Chemical Warfare Center was activated.16

Brig. Gen. Ray L. Avery, commanding general of Edgewood Arsenal, was put in charge of the new Chemical Warfare Center. (Chart 7) Avery remained in that post for the duration of the war, retiring from active service in April 1946. The organization of the center changed little throughout the war except for the activation of units to carry out newly assigned functions. For example, in February 1943 a Control Division was established, and in May the old Inspection Office was abolished and a new Inspection Office reporting directly to the chief of the Inspection Division, OC CWS, was activated.

The transfer of elements of the Chief’s office to Edgewood in the fall of 1942 led to some administrative difficulties, particularly in personnel matters.17 The Technical Division, OC CWS, for example, wanted to control its members located at Edgewood directly through the Washington office. The chief of the Technical Division felt that he could obtain more and better qualified employees in that way. The Chief, CWS, nevertheless,

decided that all personnel activities at the Chemical Warfare Center should be processed through that headquarters and this procedure was adopted.

The duties of the commanding general of the Chemical Warfare Center corresponded closely to those of a post commander. They included personnel administration, internal security, public relations, post inspection, and post engineer functions for all elements of the center. The centralization of administration for those activities invariably made for a greater degree of efficiency. For example, it was far more effective to have one central office administer personnel functions than to have a half dozen independent offices scattered over the post, as was formerly the practice.18

The Arsenals

The Chemical Warfare Center included an Arsenal Operations Department which supervised strictly arsenal activities. As the new arsenals at Huntsville and Pine Bluff and later at Rocky Mountain19 got into operation, the nature of arsenal activities at Edgewood changed. These new arsenals took over the bulk of the arsenal operations in the CWS, and the Edgewood plants eventually assumed the role of pilot plants, in addition to handling a number of “blitz” jobs.

On 6 May 1942 General Porter recommended to the Secretary of War that another CWS arsenal be erected near Denver, Colorado. Within a week Under Secretary of War Patterson issued a memorandum of approval for construction of the new arsenal.20 This memorandum stated that the new installation would be used for producing certain gases and for loading operations and that the necessary funds, except for the purchase of land, would be made available to the CWS by the Army Air Forces.

Construction of the new arsenal, which was designated Rocky Mountain Arsenal, was begun in June 1942. As a result of the experience gained in building earlier CWS arsenals, the quality of its construction was superior to that of the others.

In the course of the war each of the CWS arsenals came to carry out much the same type of operation. Although the original plants at the new Pine Bluff and Rocky Mountain Arsenals were built to carry out certain specific operations, other types of plants were shortly erected at both arsenals. During the war, each of the CWS arsenals manufactured toxic

agents, smoke and incendiary matériel, and with these filled shells, grenades, pots, and bombs supplied, as a rule, by the Ordnance Department.21

The physical layout of an arsenal was not without its effect upon the installation’s organization and administration. Of all the CWS arsenals, Huntsville was by far the least compact. There, three separate plant areas had been erected, each separated by considerable distances, and each in turn separated from headquarters by several miles. Two of the plant areas were duplicates of each other, because Huntsville Arsenal was built on the theory that an enemy air attack was entirely feasible and that if one area were knocked out there was a chance that the other area might be saved. The third plant area at Huntsville was used for manufacturing and filling incendiaries. In setting up an organization for the post, General Ditto arranged for each area to have its own administrative units for engineering, personnel administration, property administration, storage, and transportation.22 Although these units were responsible to higher echelon units at post headquarters, the supervision was more nominal than real. Because the system obviously made for duplication and added expense, it soon became necessary to set up a more centralized organization at Huntsville.

In contrast to Huntsville, Pine Bluff and Rocky Mountain Arsenals were compact, and therefore no basis existed for the duplication of administrative units. But those arsenals, like other CWS installations, were characterized by basic organizational and administrative defects in the early period of their existence. One of those defects was the fact that a great number of individuals reported directly to the commanding officer; in other words, there was not proper delegation of authority. Still more serious was the tendency on the part of commanding officers to organize and administer arsenals like other posts, camps, and stations. This tendency sprang from the limited experience of CWS officers in arsenal operations which were of course more technical than operations at other types of installations. Unlike the Ordnance Department, whose arsenal activities dated back many years and were carried on somewhat extensively even in peacetime, CWS operations came to a halt following World War I and

were not resumed until the emergency period.23 Consequently there were very few CWS officers, or civilians either, who were experts in arsenal activities. When war broke out, it was necessary for the Chief, CWS, to put his arsenals under the command of high ranking officers considered good administrators in the hope that they would utilize the services of Reserve officers who were experts in the technical operations.24

The defects in arsenal organization were largely overcome by the close of 1943. Under the ASF program for organizational improvement, both the Control and Industrial Divisions, OC CWS, reviewed closely the organization charts of the various arsenals. Where the charts did not conform to organizational standards, the commanding officers were contacted personally with a view to having them make the necessary changes.25

The Depots

At the time war was declared new depots at Huntsville and Pine Bluff were in the planning stages, and the site for another depot in northern Utah had not yet been selected.26 The burden on the Edgewood Depot consequently was heavy, although the situation was somewhat eased by the procedure adopted by the Supply Division, OC CWS, during the emergency period of shipping equipment directly from points of manufacture to posts, camps, and stations throughout the country. The new depots at Huntsville and Pine Bluff were ready for partial operation in the fall of 1942. The site finally selected for the new depot in Utah was in Rush Valley, Tooele County, near the town of St. John. There by early 1942 the CWS erected an immense new installation comprising 370,000 square feet of closed storage space. In July 1942 this installation was designated the Deseret Chemical Warfare Depot.27 Also in 1942, while the new depots were under construction, the Chemical Warfare Service acquired additional storage facilities in the following War Department general depots: San Antonio, Texas; Memphis, Tennessee; Atlanta, Georgia; Ogden, Utah; and New Cumberland, Pennsylvania. In March 1942 a large

warehouse at Indianapolis, which the CWS had been occupying, was selected as a depot for spare parts.28

Originally the depots located at CWS arsenals had the same name as the arsenals, which led to confusion in the mails. In July 1943, therefore, the names of those depots were changed as follows: Edgewood Chemical Warfare Depot to Eastern Chemical Warfare Depot, Huntsville Chemical Warfare Depot to Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot, and Pine Bluff Chemical Warfare Depot to Midwest Chemical Warfare Depot.29 The latter two depots were under the jurisdiction of the commanding officers of the arsenals to which they were attached. While not officially designated as a depot, a storage area at Rocky Mountain Arsenal was used to store items not shipped immediately to ports of embarkation.

In 1944 the CWS acquired the last of its wartime depots when ‘Jo() acres of the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works were transferred to the CWS and designated the Northeast Chemical Warfare Depot.30 (Chart 8)

The administration of the Eastern, Gulf, and Midwest Depots had one characteristic in common:31 in each case housekeeping functions were performed by an adjoining installation. In the case of the Eastern Depot the Chemical Warfare Center took care of those functions, while the Gulf and Midwest housekeeping functions were handled by Huntsville and Pine Bluff Arsenals respectively. In contrast to those three depots the other three —Deseret, Northeast, and Indianapolis—were responsible for their own housekeeping activities. In the CWS sections of general depots the Quartermaster Corps had responsibility.

Standardization of Depot Organizations

In no type of installation was such uniformity of organization achieved as in the depots. This was the result of the intense interest which the ASF showed in storage and distribution activities. Early in 1943 the ASF made a survey of operating and storage methods in typical depots under

Chart 8: Schematic Diagram, Chemical Warfare Supply, as of 6 December 1944

its jurisdiction. Its findings were published in Depot Operations Report No. 67, March 1943, which, after making a number of criticisms of current depot administration, went on to recommend basic organizational changes. Chief among the changes was the activation of storage, stock control, and maintenance units in all technical services headquarters and in all depots.

Pursuant to ASF directives the chief of the Supply Division, OC CWS, took immediate steps to reorganize his division to include Storage, Stock Control, and Maintenance Branches.32 Col. Norman D. Gillet also directed the depots and the chemical sections of ASF depots to set up similar units. By the summer of 1943 this had been accomplished. By the fall, control units had also been activated in the depots, and the commanding officers could thereby better maintain organizational standards established by higher echelons. The publication of ASF Manual M417 in 1944 also served as a guide to depot commanders on organizational standards. Chart 9 shows a typical depot organization, that of the Eastern Depot, in April 1945.

Training Installations and Facilities33

Camp Sibert

The expanded training program of the Army had by late 1941 led to the need for additional CWS training facilities. In recognition of this fact, G-3 on 2 December 1941 advised the Chief, CWS, that a new chemical warfare replacement training center would be required in 1942.34 With an adequate training area not available at Edgewood, it was necessary to consider locating the training center elsewhere. A survey of the Maryland countryside failed to disclose a large tract of reasonably priced land suitable for the purpose, and a decision was made to locate a site elsewhere. In the spring of 1942 an area near Gadsden, Alabama, in Etowah and Saint Clair Counties, was surveyed and selected. This site included 36,300 acres of sparsely inhabited rolling Alabama farmland, ample for a 5,000-man replacement training center and also able to accommodate, as stipulated by the CWS, eventual expansion to 30,000 to provide for unit training. Promise of good health conditions and suitability for year-round training led the

Chart 9: Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland: Eastern Chemical Warfare Depot, as of 20 April 1945

Chart merged onto previous page

General Shekerjian, Commanding General, Replacement Training Center, Camp Sibert, Alabama

CWS to determine on this location for its new training center.35 The Chief of Engineers was accordingly directed in May 1942 to construct the housing facilities for a 5,000-man replacement training center with completion date set for 1 December 1942.36 The new reservation was designated Camp Sibert in honor of the first Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service.37 Col. Thomas J. Johnston was made commanding officer while construction was still under way. When the RTC was moved from Edgewood to Camp Sibert in the summer of 1942, Colonel Johnston became the camp commander and Brig. Gen. Haig Shekerjian, the RTC commander.

In the fall of 1942 the War Department authorized activation of a Unit Training Center (UTC) at Camp Sibert. Activation of the UTC, Chemical Warfare Service officials felt, would require another headquarters since the functions of replacement training and unit training were so different that it would be impracticable to include them under one command.38 Therefore the UTC was activated as a separate CWS installation in September 1942. The War Department letter authorizing the installation was indorsed by the Fourth Service Command to the commanding general of the CWS Replacement Training Center instructing him to activate and assume command of the new Unit Training Center.39 Accordingly General Shekerjian became responsible for replacement and unit training activities.

General Bullene, Commander, Unit Training Center, Camp Sibert, Alabama. (Photograph taken in 1952.)

This arrangement was not satisfactory to the Chief, CWS, who believed that efficient administration required separate commanding officers for the UTC and the RTC. By January 1943 the number of units in training at Sibert had reached fifty-four, as compared with thirteen two months before, and General Porter thereupon appointed Col. Egbert F. Bullene, chief of the Training Division in his office, as commanding officer of the Unit Training Center.40 Bullene was promoted to brigadier general on 27 April 1943, so that both the RTC and the UTC were commanded by general officers each of whom enjoyed a status of relative independence. Meanwhile, Colonel Johnston continued to command the post, providing services and utilities for both training centers. Between the two centers a rivalry developed, which was open and probably not unhealthy.

Within less than three months these administrative arrangements met with opposition from the commanding general of the Fourth Service Command, who objected to communicating with two general officers, each of whom commanded autonomous installations at the same military station. On 24 May 1943 he recommended to the ASF that existing instructions be amended to permit him to assign General Shekerjian as post commander and commanding general of the RTC, with Bullene, as Shekerjian’s subordinate, to command the UTC.41 General Porter opposed this recommendation but General Somervell sustained it, and appropriate orders were accordingly issued. The new arrangement continued in effect until the UTC operations were suspended in March 1944.

The commanding general of the service command had ample authority on which to base his recommendations of 24 May, for just twelve days before the ASF had designated Camp Sibert a Class I installation of the

Fourth Service Command.42 This was in conformity with ASF policy in 1943 of emphasizing the role of the service commands in technical training.43 The chiefs of the technical services resisted this policy because they naturally disliked surrendering direct control over their branch training. When General Porter heard that Camp Sibert had been made a Class I installation, he wrote a letter to General Somervell in which he questioned the wisdom of the move. “Great pains,” he declared, “have been taken to insure the proper functioning of the training activities at Camp Sibert which are essential not only for their product but as a laboratory for the development of chemical warfare matériel of new and untried types. ... the radical change proposed might well cancel a considerable part of the progress made.” To this General Somervell replied that he was convinced the new system would work well, and he urged General Porter to give it “a fair and impartial trial.44 Actual transfer was made in July 1943, and from that time until the close of the war the Chief, CWS, was responsible only for the promulgation of training doctrine, the establishment of student quotas, and the preparation of training programs.

West Coast Chemical School

In July 1943 the CWS asked the ASF for authority to establish a chemical warfare school toward the West Coast. The recommendation was advanced as a means of providing final instruction for military personnel moving into Pacific theaters of operations and of eliminating extensive travel for those selected at western stations for training in chemical warfare. The functions of the new school would be: (1) to provide for short technical refresher courses of one-week duration for CWS officers in the Far West who were scheduled for overseas duty; (2) to provide short courses for units gas officers who could not be economically sent to the Chemical Warfare School at Edgewood; (3) to conduct training for civilians, as directed by the Office of Civilian Defense; and (4) to meet requests of naval authorities for training naval personnel on the Pacific coast in gas defense.45

The reaction of the ASF to the proposal for another chemical warfare school under the jurisdiction of the Chief, CWS, was not favorable. Instead, the chief of the Training Division, ASF, on II September 1943 directed that a chemical warfare school be set up at Camp Beale, California, as a Class I installation under the jurisdiction of the commanding general of the Ninth Service Command.46 Such a school, known as the West Coast Chemical School, was activated in October 1943, and the first class assembled on 13 December.47 As of 8 March 1944, loo students were in attendance at the school, 56 of whom were officers and 44, enlisted men. These included personnel from the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps.48 Col. Maurice E. Jennings was named commandant of the school.

The school at Camp Beale was so located that it could operate with little interference from other activities at the post. Its physical layout consisted of six 2-story barracks buildings, two mess halls, a I-story supply building, a I-story headquarters building, and a 1-story building used for a library, a day room for enlisted men, a post office, and a publications supply room. The commanding general at Camp Beale was most cooperative in furnishing the school with any facilities it required.

Experience finally demonstrated, however, that it was not feasible to operate the school as an activity of a service command, and on 24 April 1944 General Porter requested the director of Military Personnel, ASF, to relocate the school at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal. The Chief, CWS, gave a number of reasons why he preferred to have the school at Rocky Mountain. There it would have the benefit of an environment meeting the special needs of the CWS, where the commanding general could furnish the school with chemical warfare matériel, and where the students would be impressed with all the activities of a CWS installation. More direct liaison would be afforded between the instructors at the school and the Chief’s office, and thus the staff of the school could keep up to date on current developments in the CWS. The weather and terrain at Rocky Mountain Arsenal were more conducive to the use of smoke and chemical agents in training than at Camp Beale, and finally the housing and classroom facilities at the arsenal were more suitable for conducting classes.49 General Porter’s

recommendation to move the school was approved by the ASF on 14 May 1944 and on 1 June by the Secretary of War.50 From June 1944 until the close of the war the school, which was now renamed the Western Chemical Warfare School, was an activity of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal. Col. George J. B. Fisher succeeded Colonel Jennings as commandant when the school was moved to the Rocky Mountain Arsenal. In July 1945 Colonel Fisher was transferred to overseas duty and was succeeded by Col. Harold Walmsley, who remained commandant until the close of the war.

Research and Development Facilities

During the emergency period it became evident that the facilities for research, development, and testing at Edgewood were not adequate for the large-scale program being inaugurated. As mentioned above, a new technical research center had been constructed by December 1941, and by that time also a new CWS laboratory had been erected on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.51 Later the CWS acquired the use of a laboratory at Columbia University. Both laboratories became CWS installations.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Laboratory.52

In the autumn of 1940 Bradley Dewey, president of the Dewey and Almy Chemical Company, who had headed the Gas Defense Production Division, CWS, in World War I and had kept up an active interest in the service in the peacetime years, suggested that a new CWS development laboratory be established at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.53 The following February the proposition was discussed at a conference of high ranking CWS officers and outstanding scientists in Washington.54 The

purpose of the conference was described in these words: “To consider the possibility of providing for additional development space and facilities for the Chemical Warfare Service in order that any new ideas, devices, or processes developed on the laboratory basis by the National Defense Research Committee might be tested out on a large scale to determine their probable application for military purposes.”55 Conference members decided to approach Dr. Karl T. Compton, president of MIT, on the possibility of the CWS obtaining additional facilities there.

By mid-March an agreement had been drawn up between the CWS and MIT which provided for a half-million dollar laboratory on grounds to be leased to the CWS upon approval of the War Department and the National Defense Research Committee.56 Under this agreement the services of the MIT faculty, for advisory and consultant purposes, were made available to the Chemical Warfare Service. The new development laboratory when erected was made a Class IV installation of the CWS under Army Regulation 170-10 and was put under the command of Capt. Jacquard H. Rothschild. As of 28 May 1943 the organization chart of the installation called for 117 officers and 215 civilians. Because of the nature of its activities, the laboratory was organized along functional lines; the divisions were Protective Materials, Respiratory, Chemical Development, and Engineering and Test. The laboratory continued in operation until 21 August 1945.

Columbia University Laboratory57

The transfer of the incendiary bomb program to the CWS in the fall of 1941 created the need for a laboratory devoted to the development of incendiary munitions. Col. J. Enrique Zanetti, whom General Porter had named as chief of the Incendiaries Branch in his headquarters, was a member of the Columbia University faculty in chemistry and was therefore intimately acquainted with the potentialities of the university’s laboratories. Zanetti envisioned an arrangement between CWS and Columbia such as already existed between CWS and Massachusetts Institute of Technology: the university would lease laboratory and office space to the Chemical Warfare

Service and make available the services of its faculty members in engineering and chemistry, and CWS would establish an administrative unit at the university. Late in 1941 Colonel Zanetti approached Columbia’s president, Nicholas Murray Butler, on the proposition, and in early 1942 President Butler agreed to the arrangement. On 31 January 1942 the War Department approved the proposition, and a formal contract, similar to the CWS-MIT contract was drawn up.58

In April 1942 Lt. Col. Ralph H. Talmadge was put in command of the Columbia laboratory, which was designated a Class IV activity. A peak personnel figure of 43 was reached at the laboratory in May 1943; of those, 23 were officers, and 20 were civilians. The civilian employees were not under federal civil service but were hired and trained by the university.

When the Incendiary Branch of the Chief’s office was inactivated in June 1942, supervision of the Columbia CWS laboratory was turned over to the Technical Division, OC CWS. The scope of the laboratory’s activities was broadened to include development work not only on the incendiary bomb but also on other items such as the 4.2-inch chemical mortar and the flame thrower. On 31 December 1943 the CWS-Columbia University contract was terminated and the laboratory’s functions transferred to the Chemical Warfare Center.

Testing Facilities

The expansion of CWS research and development activities created a demand for new chemical warfare testing stations. At the start of the war all chemical warfare testing was done at Edgewood, where the Technical, Medical, and Inspection Divisions, the Chemical Warfare Board, the Chemical Warfare School, and the adjoining Aberdeen Proving Ground of the Ordnance Department all shared the same testing fields. By the time war was declared these facilities were already greatly overcrowded. To complicate matters still more, testing at the arsenal was becoming more hazardous because of the growth of populated areas adjacent to the arsenal. New testing grounds in a more sparsely populated locality were sorely needed. Experience had demonstrated that this new locality should be characterized by climatic and geographic features more favorable to the

testing of various chemical warfare matériel than found in eastern Maryland.59

Dugway Proving Ground

On 3 January 1942 General Porter sent Maj. John R. Burns to Salt Lake City to investigate the possibilities of a testing ground in Utah. Major Burns, after conferring with the Army’s district engineer and the representative of the Federal Grazing Service in Salt Lake City, recommended a tract some eighty-five miles southwest of the city, lying partly in the Salt Lake Desert and partly in the Dugway Valley. Burns’ recommendation met with the approval of the OC CWS and the War Department, and a 265,000-acre stretch of land was acquired and developed into the CWS Proving Ground, Tooele, Utah.60 On I March 1942 the installation was activated with Burns, then a lieutenant colonel, in command. From its inception to the close of the war Dugway conducted tests on both experimental and fully developed munitions.

Burns, raised to the rank of colonel in August 1942, was succeeded as commanding officer at Dugway on 28 November 1944 by Col. Graydon C. Essman who remained in command until the close of the war. The commanding officer at Dugway was responsible for both testing and housekeeping functions. To supervise the testing activities he appointed a director of operations.61 Military strength at the post reached its peak in the summer of 1944, when there were over one hundred and fifty commissioned officers and over a thousand enlisted men on duty. These numbers included over one hundred members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). There were few civilian employees at Dugway because of its inaccessibility.62

San Jose Project

The leasing of San Jose Island to the U.S. Government had been preceded by considerable reconnaissance of the Caribbean area for a suitable site to carry on chemical research under tropical conditions.63 In the fall of 1943 Col. Robert D. McLeod, Jr., and Dr. Carey Croneis of the National Defense Research Committee made a thorough search of the territory

adjoining the Panama Canal Zone for a peninsular site but found none suitable. Then by plane they searched the entire coast of Panama. They finally decided on San Jose, some sixty miles from the Pacific entrance to the canal, because the climate and topography were suitable and the foliage was of the desired character.64 After consulting with the district engineer, Colonel McLeod forwarded his recommendations to the Chief, CWS, on 25 October 1943.65

General Porter wanted to make doubly sure of the suitability of the proposed site, so after reviewing McLeod’s suggestions he sent General Bullene, whom he had selected to direct the project, to the Panama area. Bullene confirmed McLeod’s findings, and thereupon the Chief, CWS, recommended to the General Staff that the island be acquired. The General Staff held up the recommendation pending assurance that the tests would not harm the rare animal, plant, or reptile life on the island. After Bullene secured a signed statement to that effect from the director of the National Museum in Washington, the General Staff gave its approval.66

On 9 December 1943, the Chief of Staff directed Lt. Gen. George H. Brett, Commanding General, Caribbean Defense Command, to lease San Jose Island for the period of the war and one year thereafter. General Brett was informed that General Bullene would arrive at the Caribbean Defense Command headquarters on II December and the command was to build “roads, trails and camp sites” for the San Jose Project. On 16 December, General Brett requested the government of Panama to lease the island to the government of the United States. To this request the Panamanian Government gave ready assent.67

Shortly after General Bullene’s arrival in Panama, a crew of native workmen under the supervision of Mr. Russell Foster, engineer adviser to

the Corps of Engineers, landed on the beach at San Jose and began to cut a trail inland. Original plans called for the completion of the entire testing program within a period of about two months, and construction was undertaken with this time limit in mind. It was not long before drastic revisions of the time schedule had to be made. General Bullene insisted that every precaution be taken against the possible spread of malaria on the island, even though this precaution might slow up construction. His previous experience in the tropics had impressed upon him the need for such measures, and in addition it was well known that an important English project had failed because precautions against malaria had not been taken. After differences arose between the CWS and the Corps of Engineers on the building schedule, Bullene requested that the commanding general of the Caribbean Defense Command transfer responsibility for all construction to CWS jurisdiction.68 This was done, and Russell Foster was transferred to CWS jurisdiction as an engineer adviser. Under Foster’s supervision 30o buildings, some 3 miles of 20-foot roadway, 109 miles of 10-foot roadway, and 14 miles of foot trails were constructed by August 1944.69

From the project’s inception until early in September 1944, military personnel rolls averaged about five hundred officers and enlisted men.70 As the initial phases of the tests were concluded the chemical companies were returned to the mainland.71 By November 1941 there were 43 officers and 413 enlisted men attached to the San Jose Project, and a year later, with the war over, the number stood at 37 officers and 300 enlisted men.72

In addition to Army personnel, representatives from the following organizations were stationed at San Jose: U.S. Navy, British Army, Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Air Force, and the National Defense Research Committee. General Bullene described the project as a united effort of all these participants to secure certain technical data which would be useful in winning the war. Therefore he insisted that no distinction be made between nationals or organizations and directed that men be assigned to duties for which they were best qualified. Members of the NDRC, he

ruled, were to occupy the position of commissioned officers and were to be accorded the same consideration as officers.73

By July 1944 the installation organization consisted of an administration director, a technical director, an intelligence officer, an advisory council, the adjutant, and the chief of the Army Pictorial Division, Signal Corps, which made films of the project. The administration director was responsible for the quartering, rationing, messing, supply, medical attention, discipline, and morale services for all persons on the project. The technical director, Colonel McLeod, was charged with the direction and supervision of all technical tests and the preparation of the reports of tests which would be forwarded to the commanding general through the Advisory Council. The Advisory Council was a very important element in carrying out the mission of the project. It was made up of the executive officer, technical director, chiefs of the principal technical divisions, and other designated key personnel. The duties of the Advisory Council were to analyze and interpret the technical data of the various tests as an aid to the commanding general in reaching sound conclusions in his reports to higher authority and to prepare such operational instructions for the using arms and services as were required.

In order to insure that the testing at San Jose would not be obstructed by administrative difficulties, the Chief, CWS, activated a San Jose Project Division in his office on 27 September 1944.74 Under this arrangement the San Jose Project became a branch of the new division. General Bullene was made chief of the San Jose Project Division, at the same time retaining command at the project.

Biological Warfare Installations75

Mention has been made of the biological warfare installations established in World War II.76 Camp Detrick, the first and most important of those installations, was activated on 17 April 1943 under the command of Lt. Col. William S. Bacon.77 Bacon was succeeded by Cols. Martin B.

Chittick and Joseph D. Sears. Actual construction of the camp, which came to occupy an area of more than five hundred acres, was not completed until June 1945. By then a small, self-contained city had been built containing more than 245 separate structures, including quarters for 5,000 workers. At the peak of operations in August 1945 there were at Camp Detrick 245 Army officers and 1,457 enlisted personnel, 87 Navy officers and 475 enlisted men, and 9 civilians, exclusive of civilian consultants.

By September 1944 the program at Camp Detrick, conducted jointly by civilian scientists and employees of the Chemical Warfare Service, the Medical Department, and the Navy, included research and development on mechanical, chemical, and biological methods of defense against biological warfare, production of agents and munitions for retaliatory employment, development of manufacturing processes through engineering and pilot plant studies, development of safety measures for protecting personnel on the post and its surrounding communities, and devising of suitable inspection procedures for production plants.78 Within a year of its activation the technical staff had grown to such proportions, and the range of research operations was so wide, that it became difficult for key personnel in one unit to keep abreast of progress in other units. Consequently, a tendency toward duplication of effort developed in some of the laboratories, a problem not finally solved until almost the end of the war.

Horn Island, off the Mississippi coast, was selected as a field test site in early 1943, and construction got under way in June. No special structures, such as necessary at Camp Detrick, were required on the island aside from quarters for the test personnel and technical buildings adjacent to the grid area of the test site. The one unusual feature of the installation was an eight-mile narrow-gauge railroad which had to be constructed because building roads on the sandy island was not practicable. Track, locomotive, and wooden cars were shipped from Fort Benning, Georgia, and installed by a company of Seabees.

Administratively, Horn Island was a substation of Camp Detrick from its activation until June 1944 when it became a separate installation under the jurisdiction of the Special Projects Division, OC CWS.79 Because of its

proximity to the mainland, only the most restricted of field tests could be made on the island. As the biological warfare program expanded, it became obvious that a larger and more remote test area was necessary for the field program envisioned.

The biological warfare installation known as Granite Peak, a 250-square-mile area at Tooele, Utah, was activated in June 1944 as the principal large-scale test field. Administratively, Granite Peak was a subinstallation of Dugway Proving Ground, to which it was adjacent, and many of the administrative duties of the post were operated or supervised by the Dugway Proving Ground post commander. The biological warfare and chemical warfare field installations achieved a high degree of cooperation in their test activities. For example, the proving ground detachment flew all airplane missions required by Granite Peak operations, and existing Dugway facilities provided the meteorological forecasting service required at the Peak.80 Nevertheless, Granite Peak retained full autonomy over all its technical operations. Its test operations reached their height in July 1945, when 10 Army officers and 97 enlisted men, and 5 Navy officers and 55 Navy enlisted men were engaged in conducting tests.

The Vigo Plant, near Terre Haute, Indiana, was an Ordnance Department plant which was turned over to the CWS in May 1944.81 Its mission was the production of agents being developed at Camp Detrick. Vigo was considered to be a pilot plant rather than an arsenal, because of the experimental and highly technical nature of operations that were required before it could be proved for its intended purpose and accepted by the chief of the Special Projects Division and the Assistant Chief, CWS, for Matériel. Proof of the plant was considered to mean operation of all facilities at sufficiently high levels and for sufficient lengths of time to demonstrate the plant’s capacity to perform its mission.82 As plans for the operation of the Vigo Plant were made, it was proposed to limit the scale of operations to proving the plant, training personnel, providing end items for surveillance and proof testing, and accumulating material in anticipation of military requirements. The personnel involved in this operation in July 1945

consisted of 115 Army officers and 863 enlisted men, 32 Navy officers and 304 Navy enlisted men, and 65 civilians.

Organizational developments in the CWS during World War II included the expansion of existing organizational structures, particularly in the procurement districts, the activation of new administrative units in all installations to carry out functions delegated by the Army Service Forces, and the setting up of entirely new organizations such as the Chemical Warfare Center, the training center at Camp Sibert, and the new CWS laboratories, testing grounds, and biological warfare installations.

In its administrative no less than in its operational activities, the CWS felt the influence of the ASF. But only with regard to the depots was ASF influence direct and predominant. ASF headquarters specified that a standard organization be established in each depot. In the procurement districts and arsenals ASF initiative was never so pronounced. There the CWS generally inaugurated and carried to completion all actions of an administrative nature. These actions were, of course, subject to ASF approval.

In contrast to ASF activity at the depots, whose revised organizational structures were looked upon approvingly by key personnel in the CWS, the ASF decision to put Camp Sibert under the jurisdiction of the commanding general of the Fourth Service Command, was not viewed with favor by the Chief, CWS. General Somervell, nevertheless, stood by the ASF directive to make Sibert a Class I activity of the Fourth Service Command, as noted above. General Porter undoubtedly had that situation in mind when in September 1944 he set up the San Jose Project Division in his office to supervise all activities of the Panama installation. Porter was taking a precaution to insure that all responsibility for San Jose would remain under CWS control.