Chapter 15: Officer Candidates

OCS Role in Officer Procurement

During World War I the Chemical Warfare Service obtained its officers either by transfer from other branches or by the direct commissioning of specially qualified civilians. Prior to World War II a substantial body of Reserve and National Guard officers had been developed, a group which, it was recognized, would have to be reinforced in time of emergency by the temporary commissioning of some technical specialists. While the need for officer candidate training was appreciated, there was no expectation that this training would contribute materially to the officer procurement program in a major war. Actually the CWS Officer Candidate School in World War II provided a total of 6,413 second lieutenants, many of whom rose to field grade before the end of hostilities.1

When war was declared, nearly one thousand CWS officers were on active duty, 90 percent of whom were nonregulars. After Pearl Harbor the officer procurement curve began to rise more sharply. The officer strength of the CWS stood at approximately 1,800 when the first OCS class of 20 second lieutenants was commissioned at Edgewood on 4 April 1942. Most of the officers then on duty were Reservists or men having other military background. It became clear by this time that other sources would have to be tapped to provide the large increase of officers required by the expanding CWS program.

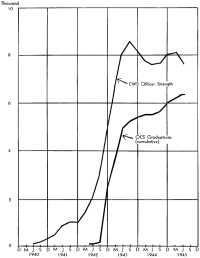

Compared to the number of officers procured from other sources, the OCS contribution was negligible even in the late summer of 1942, when CWS officer strength of three thousand included only two hundred OCS graduates (Chart 11). The rapid rise in OCS output, which began in the fall of 1942, brought the two lines into approximate balance so that for the next nine months the increase in officer strength had an almost direct

Chart 11: Chemical Warfare Service Officer Strength and OCS Graduations: May 1940–July 1945

Source: Annual Reports of the Secretary of War, 1940-41, Appendix A, CWS-OCS Class Records.

relation to OCS graduations; in other words, during this period the Officer Candidate School was almost the only source from which the Chemical Warfare Service derived its new officers. When both lines began to level off toward the end of 1943, total officer strength still exceeded OCS graduations by approximately three thousand; yet two out of every three CWS officers had received their commissions at the Officer Candidate School.2

Capacity Targets

The Army’s officer candidate program of World War II got under way in July 1941 with the opening of ten schools.3 Each was under direct control of the chief of an arm or service. No school was authorized for the training of CWS officer candidates at this time although provision was made for CWS soldiers selected as officer candidates to be trained and commissioned in other branches.4 In August the Chief, CWS, was advised by the War Department to be prepared to open a small chemical warfare OCS in January 1942. The War Department confirmed this decision in November 1941, when it increased the number of officer candidate schools from ten to thirteen and established a total capacity for 3,595 students, of which the CWS school was allowed a quota of twenty.5

It soon became standard procedure for the War Department to set quarterly the capacity of each officer candidate school. Using this figure as a basis, the branch concerned drew up an allocation of vacancies to senior commands such as armies, corps areas, and replacement training centers. This allocation was reported to The Adjutant General, who then handled the distribution of quotas, including those to overseas commands.6 The War Department thus retained control over the size of the schools. Such centralized control appeared necessary since capacities of the schools were dictated by requirements for officers which in turn were computed from a frequently changing troop basis.

This arrangement held until March 1943, when control over officer candidate enrollment was delegated to the three major commands of the

War Department. After a year of operation under this arrangement the War Department in March 1944 resumed control over OCS enrollments, returning to a procedure essentially similar to that which had been in force initially.7

The Chief, CWS, was advised informally from time to time by the General Staff as to major changes in OCS capacity foreseen by variations in the chemical troop basis. The first of several such notifications came shortly after the declaration of war when the CWS was directed to plan for the expansion of its officer candidate school to a capacity of 100 “at the earliest practicable date,” with the understanding that further slight increases might be necessary.8

The latter proved to be an understatement. Four months later, the Chemical Warfare Service was instructed to expand its officer candidate school to accommodate a total of 1,150 enrollees, this goal to be reached by September 1942.9 Within a few weeks, and while plans were being made to accomplish this increase, the CWS studied the current troop basis as then listed for 1942 and computed the CWS officer requirements for 31 December 1942 to be:10

| Total | 5,091 |

| CWS officers with AAF | 800 |

| AGS and ASP’ units | 1,186 |

| Branch duty | 3,105 |

On the basis of these figures, the Chief, CWS, recommended to the War Department that capacity of its officer candidate school be increased from the then authorized figure of 1,150 to a new level of 3,068. This recommendation was formally approved in June 1942.11 By this time the OCS had produced, in two classes, a total of 46 second lieutenants.

Although this ambitious new objective, equaling a thousand graduates a month, was officially adopted, it was never attained. The peak of OCS production came in December, when 895 graduates received commissions.

But already the trend of enrollments had begun to decline. The situation had been correctly appreciated two months earlier by the Training Division, OC CWS, when an analysis was made of the officer candidate procurement program. This predicted the following officer requirements as of 1 July 1943:12

| Total | 7,740 |

| Plus 5% attrition | 387 |

| Grand total | 8,127 |

| CWS officers with AAF | 1,500 |

| AGF (including CW units) | 2,595 |

| Service commands | 650 |

| CWS installations | 2,995 |

The CWS therefore had to plan in October 1942 to more than double its commissioned officer strength during the next nine months. It expected to obtain 1,400 officers by direct appointment to the then authorized Army Specialist Corps. A mere handful of ROTC graduates could be counted on. The remainder of the new officers needed would have to come from the Officer Candidate School. The Training Division estimated that classes then in session or scheduled would meet most of this requirement and that after I January 1943 the OCS production rate would be greater than needed. The Chief of the Training Division, therefore, recommended that the school capacity be reduced to 1,440 students.13 As it turned out, this was still somewhat beyond CWS requirements. Decreasing demand for officers was strikingly reflected by the cutback in authorized capacity to zoo as of 1 July 1943.14

In March 1944 the Chief, CWS, was advised by The Adjutant General that because of declining requirements the CWS Officer Candidate School would be closed with graduation of the 28th Class on 8 July 1944. This action was viewed with misgivings by the CWS. General Porter immediately submitted a formal recommendation that the school not be closed; that instead it continue to operate on a stand-by status to accommodate three

classes per year of fifty students each.15 Although the CWS was at this time somewhat overstrength in officers, two good reasons supported this proposal. The requirement for platoon leaders with chemical mortar battalions was continuous. And immediate need for additional officers was forecast should gas warfare materialize—a consideration that always influenced CWS planning. But in spite of these strong arguments against entirely disbanding the efficient OCS organization that had been developed during the preceding two years, the War Department decided otherwise and directed that the school be suspended on 8 July.16

This dictum remained in effect for over two months, during which time only one class (the 28th) was in session at the school. Shortly before the graduation of this class the War Department changed its mind and revoked the suspension order.17 The 29th class was accordingly convened on 17 July 1944, and by October four classes were being accommodated with a total enrollment exceeding 700 students. No further major changes of capacity were directed until after the cessation of hostilities.

The wide fluctuations which thus characterized top level direction of CWS officer candidate training had the inevitable effect of confusing the administrative operation of the school.

Facilities

The first OCS classes conducted at Edgewood Arsenal were housed in newly built structures provided in connection with the Chemical Warfare School enlargement program of 1941. This arrangement was satisfactory as long as the OCS enrollment was small. In order to accommodate the greatly increased student body projected for the summer of 1942, it became necessary to provide much more extensive facilities than could be made available in the immediate vicinity of the Chemical Warfare School. The pending transfer of the Replacement Training Center to Alabama provided an answer to the problems of increased OCS facilities—in fact, the requirement for OCS training at Edgewood Arsenal was one of the reasons influencing the War Department decision to relocate the Chemical Warfare Service RTC.

The inadequacies that hampered the training of replacements at Edge-wood Arsenal also hindered the training of officer candidates, once the vacated RTC area was occupied by the Officer Candidate School in the

summer of 1942. Lack of sufficient barracks was temporarily met by housing several hundred officer candidates in tents; yet need for other facilities was imperative. New temporary construction, authorized by the War Department to meet OCS requirements, and substantially completed by December 1942, included: 8 school buildings, 2 mess halls, 1 administration building, I post exchange, I supply building, and 17 barracks.18

Although academic and administration buildings for the accommodation of officer candidates were eventually provided in adequate measure, field training facilities at the Chemical Warfare Center were never entirely suitable. This was particularly true of ranges for firing of chemical mortars and for the reconnaissance and occupation of mortar positions. Because competition between the Chemical Warfare Center and Aberdeen Proving Ground for the use of the limited range areas on Gunpowder Neck was keen, it was necessary to reschedule a great deal of officer candidate training.

The final location of the Officer Candidate Division at a distance of some two miles from the Chemical Warfare School proper had the inescapable effect of lessening intimate supervisory control of officer candidate training by the school authorities. This minor difficulty might have been avoided had more integrated planning of OCS facilities been feasible.

Selection of Candidates

One out of every five candidates who entered the CWS Officer Candidate School failed to complete the course. Important among the several reasons which explain this waste of training effort were defects in the system of officer candidate selection.

Until the closing months of the war, final selection of students to attend the course was made by senior field commanders to whom quota allotments were made by the OC CWS. Criteria for selection were announced by the War Department. A direct relationship was evident between the caliber of selectees and the size of quotas. As long as enrollment was limited, there was little difficulty in obtaining qualified men to meet the quotas. After the demand for officers rose rapidly in 1942, a less impressive type of officer candidate began to appear at the school. This was a consequence of War Department policy probably as much as it was a result of mistakes by selection boards at Army installations.

Initially, students were required to attend schools of their own arms and

services unless they were found particularly qualified for service in another branch.19 The acute shortage of officers which developed immediately after the declaration of war necessitated a reversal of this policy. In February 1942, the War Department announced that “it is essential that all schools be filled to capacity for each course with the most highly qualified applicants, irrespective of the arm or service of applicants.”20 The enlisted strength of the Chemical Warfare Service was inadequate to provide enough candidates to fill the quotas that were being set up in the spring of 1942. The classes, therefore, became crowded with airmen, infantrymen, and soldiers from other services, mostly men who for one reason or another were unsuccessful in obtaining admission to officer candidate schools of their own branches. The emphasis placed by the CWS officer candidate course on chemical mortar operations proved extremely difficult for men who lacked basic training with chemical organizations, and this accounted for many turnbacks and eventual separations.

Another factor which in the view of the school authorities interfered with the selection of more suitable candidates was lack of appreciation by selecting officers of the necessary qualifications of an officer candidate. Organization commanders were under constant pressure to fill OCS quotas. That many men were sent to the Edgewood Arsenal school who were ineligible for other courses appeared evident to the instructional staff.

Action was finally taken by the War Department toward remedying what had been a source of irritation for two years—the sending of improperly selected trainees to officer candidate schools. In September 1944 certain technical branches, including the CWS, were authorized to make final selection of candidates provisionally selected by local commanders.21 The controlling factor in this action on the part of branch chiefs was the academic qualification of the applicant, other qualifications having presumably been passed by field commanders. This promising departure in selection procedure was carefully observed by the Chemical Warfare Service. A board of three officers was appointed to study the individual records of applicants as they came in. Only four classes (Nos. 33-36) were enrolled under the new procedure, so that experience with it was limited. Data relating to these four classes are of some significance.22

The CWS selection board rejected approximately two out of every three applications presented to it. The result was to limit enrollment in the four final classes to a total of 253 candidates (not counting turnbacks); these classes were the smallest that the school had accommodated since the summer of 1942. This almost drastic action did have the result of cutting losses, under the system of central selection, to the comparatively favorable figure of 15.9 percent. Reduction of losses due to academic failure was particularly notable. Leadership losses, however, now stood in the order of four to one over academic failures—a proportion much higher than encountered earlier.23 This merely emphasized a fact already recognized—that it is easier to eliminate potential failures on the academic level than in the field of leadership.

A small percentage of the officer candidates were Negroes. The records of these men were in no way distinguishable from those of white students. The Chemical Warfare Center made no distinction between candidates on the basis of race with no segregation whatever in the dormitories or the mess halls. White and Negro students, of course, sat in the same classes.24

Staff and Faculty

Before 1942 the academic organization of the Chemical Warfare School was based on the type of subject taught rather than on the type of student. This division of the faculty into groups of technical specialists was logical since up to that time commissioned officers were almost the only students attending the school. The introduction of the officer candidate course into the school curriculum brought about for the first time the development of a faculty group for a special category of students.

The first class of twenty officer candidates was taught by instructors assigned to the various technical divisions of the school, and most of whose specialties were involved to some extent in the OCS course. From the graduates of the first class, four second lieutenants were selected for detail as OCS instructors. Subsequent classes provided many more instructors and tactical officers to meet the rapidly increasing requirements of late 1942. At the same time older and more experienced instructors were drawn in lesser numbers from other departments of the school.

The CWS Officer Candidate School was headed by a field officer, usually

a lieutenant colonel, who was officially styled Director of the Officer Candidate Division of the Chemical Warfare School.

Training operations were divided among three sections—academic, field service, and troop command. The academic section handled all technical instruction. Tactics and basic military instruction were responsibilities of the field service section. Infantry drill, physical training, mass athletics, and guard duty were all conducted by the candidates themselves under supervision of tactical officers who were members of the troop command section. The latter section was also responsible for the military administration of the corps of candidates.

The three operating sections accounted for all the scheduled and nonscheduled activities of officer candidate training on a simple, well-defined basis. The activities of the three sections were in turn coordinated by an assistant director in charge of instruction. This officer also was responsible for the provision of training aids, the preparation of schedules, and the maintenance of students’ grades and ratings. In 1944, the office of the assistant director in charge of instruction was reorganized as the plans section of the school on a level with the three operating sections without, however, changing these designated functions.

Since the officer candidate course aimed at two distinct objectives—the development of military leadership and training in military techniques—two somewhat distinct types of faculty members were required: the tactical officer and the technical instructor. Tactical officers were assigned to the platoons, companies, and battalions into which the corps of candidates was organized. It was their special function to observe and report on the manner in which the candidates carried out the various staff assignments incident to the command of these units. An important duty of the tactical officer was to detect those disqualifying defects in bearing and personality which, as “leadership deficiency,” accounted for the relief of at least one out of every five who failed the course. It was the tactical officer more than anyone else who was responsible for developing the potential leader into a dependable platoon commander. Thus in a broad sense the tactical officer was an instructor, although he taught less by precept than by example and suggestion. Tactical officers were usually recruited from promising graduates of recent OCS classes, the number assigned being directly proportional to the size of the student body. The able manner in which these newly commissioned second lieutenants assumed the role of tactical officer appeared to minimize need for more formal preparation for this important work.

The academic instruction of candidates was in the hands of officers who

for the most part were somewhat older, more experienced as teachers, or who were otherwise qualified in specialized subjects. Building up this part of the faculty on the whole presented more of a problem than did selection of the tactical officers and supervision of their work. Well-qualified teachers were difficult to obtain and many of the new instructors did not prove adequate. In an effort to improve the situation the school instituted a teacher training course in November 1942. This course, which was conducted by two officers experienced in teacher training, was ten hours in length and was given over a five-day period. It resulted in considerable improvement in the instruction at the OCS.25

Although the job of forging a competent OCS faculty proceeded at a fairly rapid pace, progress along these lines could scarcely keep up with the accelerated growth of the school during the first year of its existence. The factor of instructor competence was directly related to the curve of instructor strength. Between June and October 1942 the strength of the staff and faculty soared from 31 to 215. This rate of expansion definitely exceeded the rate at which new instructors could be assimilated into the school staff. It was not until after the peak had been reached and instructor strength began to recede in the spring of 1943 that the highest standards of training effectiveness were reached.

A fair picture of the school at the end of December 1942 is afforded by the report of a training inspection conducted by an infantry officer, Col. C. L. Irwin.26 At this time, 1,880 officer candidates were in training, the ratio of instructors to students being 1 to 15.8. Instructors were reported as being well qualified in their subjects. However, their presentations were not being adequately supervised, nor was the instructor training program sufficiently advanced. These were criticisms aimed more particularly at the Chemical Warfare School than at the Officer Candidate Division of the school. For some time the OCS had been separated physically from the administrative headquarters of the Chemical Warfare School and was naturally inclined to seek emancipation from the academic control of the commandant’s staff.

An improved situation was reported following a training inspection of the Officer Candidate School in June 1943.27 At that time the student body was down to 470 officer candidates. Ratio of instructors to students was

to 3.3, a fact which indicated that faculty reductions had not kept pace with the shrinking instructional load of the school. However, the instructor-student relationship was reported as being very satisfactory, largely because sufficient instructors were available to permit organizing small classes of from thirty to thirty-five students. Instructors were found to be well qualified. Instruction was adequately supervised under the general direction of the assistant commandant, Chemical Warfare School. Training of the faculty in instructional procedures was well advanced. The pattern of teaching methods followed in the course indicated real progress in emphasizing applicatory work, as indicated by the following figures:28

| Teaching method | Percentage of course |

| Outdoor exercise | 52 |

| Conference | 26 |

| Classroom exercise | 10 |

| Film | 5 |

| Map problem | 4 |

| Lecture | 3 |

Training Program

The officer candidate course emphasized general military rather than specialist training. It was by no means a satisfactory substitute for a basic course of instruction in the duties of a technical branch such as the CWS. But in 1942 the demand for young officers was urgent and immediate. The time allotted for OCS training was little more than enough to qualify candidates to meet the responsibilities of platoon commanders in modern warfare. Since there was no assurance that once an OCS graduate left the Chemical Warfare Center he could ever return for more schooling, the program for officer candidate training had to be drawn up with this in mind. About two-thirds of the instruction was directed to the duties of junior combat commanders, which by and large were well covered. The remaining third of the program was in the nature of basic training in CWS subjects, the coverage of which was necessarily sketchy.

The primary objective of CWS officer candidate training was, from the start, the production of combat rather than staff officers. A steady demand for lieutenants to serve with chemical mortar battalions quickly absorbed many graduates of the Second to the Eleventh Classes. Once the first phase of battalion mobilization was completed, increasing numbers of graduates

went to chemical service-type companies. The stress on qualifications for combat leadership persisted into 1943 when the mobilization of additional chemical mortar battalions was begun. The requirements of the Army Air Forces for junior CWS officers were running so heavy in the last half of 1942 that special emphasis was placed on training in aviation subjects for the Sixth to the Thirteenth Classes. However, the long-range mission of the OCS course was “to train officer candidates in the basic military subjects which will qualify them as combat platoon officers.”29

Focusing of OCS training upon the needs of mortar battalions had both advantages and disadvantages. Although these units were clearly outside of the operational control of the Chemical Warfare Service, the provision of officers to command them was a CWS responsibility which the branch regarded as of primary importance. If the officer candidate could qualify for mortar company duty, he was presumed to be potentially capable of succeeding in other assignments. The result of this policy was that the CWS officer candidate who survived to graduation emerged as primarily a combat leader even though the proportion of CWS officers who attained combat duty was relatively small. The concentration of OCS training upon a target which varied from the norm for CWS officers may have been objectionable in theory, yet in practice it proved successful.

The prewar plan of the Chemical Warfare Service for officer candidate training had been written in general terms. If an officer candidate school were to be operated under the Protective Mobilization Plan, it would be “established and conducted” by the Chemical Warfare School. Classes of three-month duration would begin at M-30, M-60, and monthly thereafter. Each class would have about 150 candidates.30

The length of course as here indicated merely conformed to provisions of Mobilization Regulations 3-1. The schedule for the first course was thus developed by the Chemical Warfare School to cover thirteen weeks of instruction. This period of training continued in effect until May 1943, when the War Department extended the length of all OCS courses to seventeen weeks.31

The lengthening of the officer candidate course paralleled the extension of replacement training from thirteen to seventeen weeks, a move also directed by the War Department during the summer of 1943. The selection

of identical time-cycles for both enlisted and officer candidate training was somewhat coincidental. The proposal to add four weeks to the OCS course was initiated by Army Service Forces some time before extension of replacement training was taken under consideration.32 The idea of lengthening the course, although opposed by Army Ground Forces, was approved by the War Department for two special reasons. As was true of replacement training, there was clear need for more emphasis on the strictly military training of officer candidates. Another weighty consideration at the time was the question of failures and turnbacks at all officer candidate schools, a matter which had assumed such proportions by the end of 1942 as to require special study by The Inspector General. A longer training period, it was argued, would result in fewer rejects and more graduates.

The seventeen-week program went into effect at Edgewood Arsenal with the Twenty-sixth Class beginning 5 July 1943. Failures were less in this and succeeding classes than they had been under the thirteen-week program. This was due in part to the fact that training quotas by then had dropped and made possible such a high margin of supply over demand that a more satisfactory type of candidate was being enrolled. The longer course did permit a desirable elaboration of general military training which was principally represented by applicatory field exercises. (Table 16)

The Problem of Failures

The officer candidate course differed from all other service school courses in that the OCS student was constantly subjected to searching personal scrutiny. The candidate had to satisfy the staff and faculty as to his aptitude for eventual commissioned rank. At best, the initial selection of candidates had been provisional; it was the responsibility of the school to determine finally, as a result of close observation over an extended period of time, those who actually were qualified, both mentally and physically, to assume the responsibilities of military leadership. In OCS training the function of separating the fit from the unfit ranked barely second in importance to the function of pedagogy.

Under War Department policy, no candidate was relieved from an officer candidate school before completion of one third of the course, except for disciplinary action or at his own request.33 During the last two thirds of each

Table 16: Hours of Scheduled Instructions, CWS OCS

| Subjects | 13-Week Program (to July 1943) | 17-Week Program (after July 1943) |

| General Subjects | ||

| Total | 427 | 562 |

| Assault course | 0 | 8 |

| Bayonet technique | 0 | 8 |

| Booby traps | 0 | 8 |

| Camouflage | 5 | 13 |

| Combat organization tactics | 39 | 0 |

| Combat orientation | 0 | 13 |

| Company administration | 26 | 36 |

| Dismounted drill | 19 | 37 |

| Field fortifications | 2 | 8 |

| General tactics | 45 | 82 |

| Infantry weapons | 17 | 43 |

| Inspections | 11 | 13 |

| Interior guard duty | 3 | 3 |

| Map and aerial photo reading | 32 | 37 |

| Marches and bivouacs | 3 | 3 |

| Mass athletics | 18 | 18 |

| Mess management | 7 | 7 |

| Meteorology | 9 | 9 |

| Methods of instruction | 10 | 10 |

| Military discipline and customs | 4 | 3 |

| Military law | 13 | 10 |

| Miscellaneous subjects | 4 | 19 |

| Motor transport | 18 | 18 |

| Physical training | 38 | 39 |

| Sanitation and first aid | 8 | 13 |

| Scouting and patrolling | 19 | 36 |

| Signal communications | 8 | 8 |

| Student presentations | 20 | 20 |

| Supervised study | 12 | 12 |

| Tactical march | 9 | 0 |

| Training management | 28 | 28 |

| CWS Technical Subjects | ||

| Total | 211 | 296 |

| Antigas protection | 54 | 63 |

| Chemical agents | 26 | 26 |

| Chemical mortar technique | 56 | 70 |

| Chemical tactics | 0 | 59 |

| CWS aviation | 30 | 40 |

| CWS matériel | 17 | 17 |

| Chemical warfare developments | 0 | 3 |

| Gunners’ examination | 28 | 18 |

Source: CWS OCS Records.

course, however, there was a constant weeding out of candidates for failure to meet the exacting standards of the schools. This process at the CWS school was fair, it was fully understood by the candidates, and it was impartially administered. The school authorities from the start adopted a firm stand in resisting pressures from any direction that involved discrimination for or against any candidate. The success of the school in withstanding such pressures did much to ease the troublesome question of separations. Candidates who successfully completed the course were convinced, upon graduation, that they had won commissions through their own efforts.

For purposes of supervisory control, the course of instruction was divided into two-week “blocks,” with each block given a distinctive initial. The candidate’s work was measured in each of these periods, the yardstick of measurement differing for academic and for nonacademic progress. Often the two types of instruction merged to such an extent that it was impossible to draw a clear line between them. In either case, action leading to dismissal usually grew out of formal reports on the student’s work. The report on graded papers was a reasonably precise, objective evaluation of academic progress while the report on nonacademic activity often had to be based upon the observer’s opinion.

Failure in academic subjects was relatively easy to determine. The school devised a scheme of graduated markings under which a discredit point value was established for all rated papers falling beneath the passing grade of seventy. This table was published in mimeograph form and a copy furnished to each candidate upon enrollment. Whenever accumulated discredit points in any two-week block exceeded designated limits, the student was called before the school executive and warned that he was being placed on a probationary status as to academic deficiency. In many cases this action was sufficient to spur the candidate to better grades. Where deficiency continued, the candidate was eventually directed to appear before a board of officers who considered his case personally. When the established limit for relief bad not been exceeded by more than two discredit points and where the candidate was outstanding in leadership or possessed desirable military experience, the board frequently acted to turn him back to a subsequent class or even, in exceptional cases, to permit him to continue into the next block on a probationary status. But, in most instances, separation from the school by reason of academic failure was automatic when the scale of discredit points for relief was exceeded.

Among failures attributable to leadership deficiency, the largest number were rooted in lack of force, aggressiveness, or an unimpressive military

bearing. Physical defects, which showed up more sharply in OCS than in basic training, were also the direct cause of many failures.

Each time a candidate was observed in a supervisory or command capacity, such as marching a section to class, or commanding a platoon at infantry drill or calisthenics, he was graded by his commissioned superiors. At biweekly intervals these and other ratings based upon military deportment were tabulated. Twice during the course, each candidate was required to grade every other member of his platoon in military leadership so that the students’ own ratings combined with the ratings of the platoon, company, and battalion commanders provided an index to the relative standing of each trainee.34 This system of marking while not perfect did afford a useful guide in indicating which candidates might be below average in qualities essential to military command.

Demerits assessed for conduct delinquencies were also taken into consideration in determining a candidate’s ability to accommodate himself to the disciplinary requirements of the course. Delinquencies were grouped into four classes, each carrying appropriate demerit values. These were published for the information of candidates in an OCS instruction circular.35 Serious offenses were in most cases brought before an Honor Committee of the student body which recommended to the director of the Officer Candidate School whether the offense merited dismissal. Misconduct, however, accounted for only a small number of separations; on the whole the behavior of officer candidates was exemplary.

When the cumulative class record of the candidate, either academic or nonacademic, definitely fell below the standard set by the school, appearance before the Status Board was mandatory. This board consisted of three officers, at least one being of field grade. The board interviewed the individual, considered the records, and, where deficiency in leadership was involved, discussed the matter with his platoon commander. The personal impression made by the candidate upon the board obviously carried considerable weight in the determination of each case. After the hearing, the Status Board recommended to the commandant, Chemical Warfare School, that the candidate either be relieved from the course, be turned back to a succeeding class, or in exceptional cases be continued on probationary status. The action of the commandant on these recommendations was final.

There was a relationship, as has been indicated, between the type of selectee sent to the Officer Candidate School and the size of the student quotas. In the first six CWS classes, enrolling an average of thirty-six students, losses from all causes were negligible. The problem of failures began with the Seventh Class, which had 226 students. It became acute late in 1942 under the simultaneous impact of two adverse factors—an accentuated demand for officer candidates and an overrapid development of the instructional staff.

The whole problem of failures was closely studied by the school authorities, especially when (with the Fifteenth Class) losses climbed to the high figure of 33.4 per cent.36 A survey of failures completed by the school on 4 August 1943, disclosed a number of interesting facts. Of 5,388 enrollees who had entered the school up to and including the Twenty-second Class, only 1,420 candidates had a background of CWS experience; and failures ran consistently higher for men whose basic training had been in other branches.37 It was notable that the number of Medical Department soldiers sent to the school was disproportionately high, almost equaling the number of candidates selected from CWS units. From the case histories studied at this time it was apparent that:

a) Many candidates came to the school under the misapprehension that the course was primarily scientific rather than tactical in nature.

b) Many listed the CWS school on their applications as a secondary choice without having serious interest in chemical warfare.

c) Others filed applications largely because their organization commanders were required to fill OCS quotas.

The high rate of failures experienced late in 1942 and early in 1943 began to fall off in the latter year, after which a generally downward trend was followed until the end of the war. In the thirty-six OCS classes conducted at the Chemical Warfare Center prior to the cessation of hostilities, a total of 8,068 candidates were enrolled. Of these, 1,660 were relieved from the school before graduation.38 Academic failures accounted for 696 dismissals. Resignations, unclassified as to cause, totaled 415. Leadership deficiencies were directly responsible for 352 separations. Other causes were: miscellaneous (including physical defects), 144; conduct, 53. Of all OCS

students, 8.6 percent failed for academic reasons, 4.3 percent for leadership deficiencies, and .7 percent for bad conduct. These percentages were somewhat higher than those in AGF officer candidate schools.39

Although the full implications of the recorded causes of failure of CWS officer candidates may be subject to some question because of uncertainty as to the real reasons behind separations by resignation, the figures are clear enough to indicate a definite preponderance of losses due to academic deficiency and lack of leadership.40 Another serious cause of failure was the inability of many candidates to master military tactics and techniques, particularly those relating to chemical warfare.

Losses among trainees returned from overseas garrisons to attend OCS courses ran higher than among other categories of trainees. This was partly the result of selecting overseas veterans on the basis of their combat records rather than their intellectual or educational background. The temptation was also strong for some enlisted men to utilize an OCS assignment as a pretext to return to the continental United States without serious intention of completing the course. Although precautionary instructions in this matter were issued by the War Department in 1943, the high rate of failures among overseas candidates at the CWS Officer Candidate School continued until the end of the war.41 It is doubtful if, on the whole, full use was made by overseas commands of OCS facilities within the United States, or if, in fact, such use was feasible. Organizations had been carefully combed for CWS candidates before they moved overseas. Battlefield promotions were frequent; in the Mediterranean area where casualties among chemical mortar units were high, this means was frankly adopted in preference to officer candidate training. In the Southwest Pacific an Officer Candidate School was operated for the benefit of deserving enlisted men of most arms and services, including the Chemical Warfare Service. The War Department, seemingly as a matter of equity to forces overseas, regularly allotted OCS quotas to theater commanders; yet in the experience of the CWS Officer Candidate School the training of overseas veterans was scarcely rewarding.

In the record of the Officer Candidate School one sees repeated the pattern so characteristic of other phases of chemical warfare training. The

distinct stages of this pattern are: first, the handicap of a deliberately delayed start; second, the sudden imposition of a heavy and actually excessive training load; third, limited progress while the load is heaviest toward achieving satisfactory training standards; and fourth, attainment of a highly satisfactory status of training after the critical stage of mobilization has passed.

A criticism raised by officers intimately concerned with operation of the CWS Officer Candidate School was the lack of planning as a result of which unexpectedly heavy loads were suddenly thrust upon the school. This situation was unquestionably disconcerting to those responsible for OCS operation. Such radical capacity changes as have been recorded were easy to decide upon at high levels of authority, yet they were extremely difficult to carry out at the operating level. It was not feasible for the CWS to plan in detail very much in advance because of unpredictable variations in War Department policy regarding chemical warfare, variations which were so painfully reflected in the efforts of the Officer Candidate School to keep abreast of the increasing demands placed upon it during 1942. At the same time it is clear that in some respects CWS planning for the training of officer candidates was inadequate. For example, in the four months which followed the War Department’s warning order of August 1941 that the CWS would inaugurate an officer candidate school, it does not appear that active steps were taken to provide even the modest facilities which the project then entailed.

Experience of the Chemical Warfare Service OCS indicates that where officer candidate training is undertaken as branch schooling rather than as branch immaterial schooling, it is necessary to observe some relationship between the size of the branch and the output of the school. At the time the CWS Officer Candidate School was operating at maximum capacity the branch was able to provide no more than a quarter of the candidates who were being enrolled. It was, therefore, not accidental that in this period the peak of student failures was reached.

The effectiveness of OCS training was influenced by another situation over which the school had no control. There developed in 1943 a sizable overproduction of CWS officers. Despite careful estimates of officer requirements, second lieutenants began coming off the OCS production line much faster than they could be absorbed. The expedient adopted was to put the surplus OCS graduate in an officers’ pool until he was needed for an active assignment. But to do this—which usually meant spending several months marking time—had a corroding effect; it dulled the keen edge of zest and enthusiasm which had been built up by OCS training. Some men, after they

finally drew manning table jobs, were able to recover from the frustrations of pool assignment. Others were not.

One of the problems never entirely solved in World War II was how to handle the CWS officer candidate who possessed desirable technical qualifications but who nevertheless lacked aptitude for military leadership in the degree demanded by OCS standards. Such men, through no fault of their own, measurably swelled the ranks of rejectees. Many of them compared favorably with officers who entered the CWS directly from civil life, yet neither they nor the Army profited from their unfortunate tussle with the Officer Candidate School. This fact was recognized late in the war, when the practice was begun of rating OCS graduates according to demonstrated capacity for either combat or service assignment.