Chapter 16: Chemical Warfare Training of the Army

The training of the U.S. Army in chemical warfare involved more than purely defensive training to withstand enemy gas attack. It included, as well, training in the offensive employment of chemical weapons. Under prevailing political policy, the United States was to use toxic chemical agents (war gases) only in retaliation, although once gas warfare was begun by the enemy, U.S. retaliation was to be energetic. As to the other two types of chemical munitions—smokes and incendiaries—no such limitation was ever placed upon their use. The Chemical Warfare Service was intimately concerned with instructing in the defensive and offensive techniques relating to all three groups of chemical weapons.1

Antigas Training of Air and Ground Units

The training of the U.S. Army to defend itself against an enemy gas attack was certainly not overlooked before the war. Yet, for reasons described in preceding chapters, the level of this training in December 1941 could not be rated as uniformly high.

The status of gas defense training in air and ground force commands at the outset of hostilities affords an interesting contrast. The training in air units was reasonably good. In ground units it was poor. In each instance, the status of training reflected the predilection of the high command.

Air policy on chemical warfare training at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack called for the training of all individuals and all units of the Army Air Forces in defense against chemical attack, as well as for the tactical readiness of combat units for offensive action.2 The instructions were comprehensive

and exacting and, appearing over General Arnold’s name, they were accepted by all AAF elements at face value. The training directives, in short, were offshoots of a long established air policy of realism toward chemical warfare; and while it obviously would have been impossible for the several tactical air forces to carry out the directives in every detail, they did comply substantially with the spirit of these instructions. The program itself was adopted and carried forward by AAF headquarters without special prompting by the War Department. The functions of the Chemical Warfare Service under this program were to train CWS officers for duty with air units and to provide special schooling for AAF unit gas personnel.

Elements of the Eighth Air Force arriving in England in the summer of 1942 quickly recognized the grim seriousness with which the Royal Air Force approached the problems of protecting air establishments from gas attack. AAF defensive preparations were soon permeated by the same sense of realism, one which continued to influence AAF attitudes during the course of hostilities. The air command assumed that in the event of gas warfare, probably as much as 80 percent of the toxic agents employed in retaliation would be released from aerial bombs; and it seemed logical to suppose that the brunt of enemy attack would be against air force bases. Doctrine covering chemical defense of air establishments was set forth in considerable detail by the War Department in May 1942. The AAF followed this doctrine in developing protective procedures for the bases it occupied in England and Northern Ireland and, later, for bases in other theaters.3 Despite the magnitude of the training problems confronting the Army Air Forces, both G-3 and CWS were satisfied that preparations for gas defense of air bases overseas were reasonably adequate.

The situation as to training of ground force units was, as just mentioned, quite different. Here the high command took but a cursory interest in the subject, an attitude that was quickly reflected at many subordinate command posts. The standards announced in official Army publications had little meaning unless they were sympathetically approached at unit levels. And of the factors affecting gas defense training, the attitude of the commanding officer was the most influential. If the division commander was interested in this training, it was encouraged in the regiments and battalions; if not, then little was accomplished. Next to the unit commander, the chemical officer was in a position to contribute most to the success of the gas defense program.4 The combination of an interested commanding general and a

competent and energetic division chemical officer meant a satisfactory standard of training and consequently, a good state of gas discipline; but ground force units for the most part lacked such a combination.

Another factor that had a direct effect on the gas defense training picture was the over-all status of training of the organization. Until a unit had acquired some proficiency in the use of its own weapons, there was little time for such specialties as chemical warfare. Only after a commanding general had been satisfied that his organizations could acquit themselves well in their primary missions was he inclined to devote attention to antigas training.

Changes in War Department Policy

The cue as to emphasis to be placed on protection against chemical attack in the troop training program came ultimately from the War Department General Staff. For the first time in many years, the War Department annual training directive in force in 1941 omitted reference to gas defense training. This omission was no doubt a result of General Marshall’s insistence that this particular directive be streamlined and condensed; when it was written, other features of military training were more retarded and needed more emphasis than the chemical warfare training program. The reasons for this change were not made known to Chief, CWS, who was merely advised that chemical warfare training had been carefully considered and “purposely omitted.”5 This move, together with the fact that gas warfare situations were deliberately ruled out of early ground force maneuvers, was taken to indicate a general lack of interest by higher authorities in this type of training. As a result, the gas defense training situation for ground units, which had been fairly good in 1939, had deteriorated by the early months of 1942 to an all-time low. The Chemical Warfare Service had become most anxious about this matter during the summer of 1941 and was hopeful that with the perfection of their primary training, the divisions, corps, and armies would soon be able to give more attention to operations in situations of gas warfare. But the stepped-up mobilization that followed the Japanese attack seemed to preclude this possibility.

Although the War Department General Staff declined to interpose in the issue of gas warfare situations in the 1941 army maneuvers, staff policy began to change immediately after Pearl Harbor. As a result of the January 1942 War Plans Division study of the use of toxic gases, the AGF agreed to a more realistic approach to antigas training as well as to the use of smokes

and nontoxic chemicals in future maneuvers. These measures were incorporated in a letter-directive, sent out from General McNair’s headquarters in April 1942, which contained the admission that “recent observation of ground force units indicates the need of added emphasis on the training of troops in defense against gas attacks.6

The training situation as it existed at the beginning of 1942 required an explicit War Department statement of policy. The Chemical Warfare Service proposed the issuance of such a statement as one of a number of recommendations made with a view to rectifying the entire chemical warfare position of the U.S. Army.7 On 15 June 1942, the War Department did publish a definite directive on gas warfare training.8 This directive was broad enough, yet explicit enough, to serve throughout the remainder of the war as a top-level statement of objectives. It called for a degree of perfection in unit as well as individual training that had not been attempted since the period before mobilization of the wartime Army. It required the introduction of gas situations in field exercises and directed that increased attention be given in all service schools to training in principles and methods of gas defense. If the directive could be substantially fulfilled, the Chemical Warfare Service felt, the Army need have no undue fear of gas warfare. It became one of the training responsibilities of the Chemical Warfare Service to see that War Department policy as thus expressed was carried out in zone of interior training.

Revival of Antigas Training

The turning point in gas defense training in World War II may be dated by the issue of the June 1942 War Department directive for chemical warfare training. Before then some soldiers had been taught, in basic training, how to wear a gas mask. A few had learned the specialized duties of unit gas personnel. Yet individual training had not been continuous, the numbers who had been so trained were insignificant, and the training that was given had atrophied through disuse. Units had not learned to live and fight in gassed areas and they had not been taught the offensive employment of chemical weapons. Almost half of the U.S. Army divisions had been mobilized and trained before the revised War Department policy calling for balanced chemical warfare instruction began to take effect. The question

now to be answered was, could an established training trend be arrested in mid-channel and its direction reversed?

Actually this was feasible to but a limited degree. Units that had completed mobilization training without consideration of the problems of gas warfare could only with great difficulty retrace their steps for this purpose. Divisions moving into theaters of operation unprepared for gas warfare were obliged to attempt such preparation in conjunction with theater orientation training; this was repeatedly undertaken in Hawaii and in England by units temporarily in those areas. But for divisions mobilized late in 1942 and in 1943, the General Staff insisted that protection against gas attack be woven into their unit training from the start.

In 1943 all divisions were devoting many more hours to chemical warfare training than they had in early 1942.9 Each division ran a chemical warfare school where instruction was given to selected commissioned and noncommissioned officers over a period of three to five days. The subjects covered included agents, munitions, decontamination, and first aid. The officers who completed this course of instruction were appointed regimental and battalion gas officers, and the noncommissioned officers were appointed gas NCO’s. In that capacity they trained their respective units in gas defense. The chemical officer retained responsibility for seeing that such training was up to the standards set by the War Department. A feature of gas defense training throughout the ground forces was the requirement that every man in every unit pass through the gas chamber. This exercise was always closely supervised by the division chemical officer and his staff.

By mid-1943 the War Department was attacking the problem of gas warfare on a global basis. For the theaters, it was setting up standards of readiness; for the zone of interior, it was insisting that troops preparing for overseas movement should be trained in defense against gas attack, at least to a point where no more than maintenance training in this specialty would be required after they arrived overseas. War Department policy was spelled out in a radio message from the Chief of Staff to theater commanders on 31 July 1943. This message reiterated the President’s announcement on this subject, made 8 June 1943, and stated that, assuming “our enemies may take the initiative in the use of gas, it is essential that gas training, discipline, and equipment in your theater be such that in the event of surprise use of gas by the enemy, casualties may be reduced and initial retaliation will be

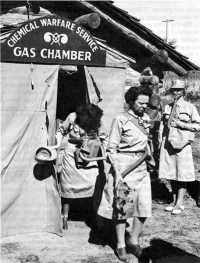

Women leaving CWS gas chamber after instruction in use of gas mask. Part of lesson is to remove mask before leaving chamber and thereby experience effects of tear gas.

heavy and prompt.”10 Reports were required from all theaters on readiness for chemical warfare as of 1 January 1944, and periodically thereafter.

The key to the readiness of overseas units to engage in gas warfare was the state of their gas discipline. The radio directive of July 1943 necessarily implied that some retraining in the theaters would have to be done before the degree of readiness called for could be attained. Yet obviously the level of this training would quickly be reduced by the continued shipment from the zone of interior of troops inadequately trained for chemical warfare. This matter was brought directly to the attention of AGF by G-3 in a memorandum which stated: “It is therefore necessary that the training of individuals and units being sent to theaters must comply strictly with established standards.”11 The War Department General Staff was determined to exact more complete compliance with the requirements of the 1942 training directive, not only by direct contact with AGF headquarters but also through employment of the Chemical Warfare Service to inspect the progress of gas defense training.

Service-Wide Inspections

During 1943 and 1944, the activities of the Chemical Warfare Service in the field of antigas training were aimed at helping the ACofS G-3 in his effort to develop a better state of preparedness for chemical warfare on the part of ground units still training in the zone of interior. An important means to this end was the procedure set up on September 1943 which provided for the technical inspection of troops and installations by representatives of technical services in order to determine the suitability of equipment and technical training.12

The chiefs of the technical services had two distinct fields of responsibility.’ Each administered an important procurement and supply agency, supervision of which was delegated by the War Department to Headquarters, Army Service Forces. At the same time each branch chief was a technical adviser to the Chief of Staff and/or the Secretary of War in his special field, the Surgeon General in the field of medicine, the Chemical Officer in the field of chemical warfare, and so forth. In this latter capacity, the relationship of the technical branch to the War Department was naturally direct rather than through the commanding general, ASF. It was the practice of the Chief of Staff, when circumstances demanded, to curtail

formality by dealing directly with the technical branches on important technical matters; this procedure was continually employed for determining the status of antigas training during the latter period of the war.

A system of inspection visits was worked out by the Chemical Warfare Service which brought about an improvement, probably as great as possible under the circumstances, in the gas defense training situation. Inspecting officers were sent out from the Field Training Branch of the Training Division, OC CWS, which was located in Baltimore. In a period of fifteen months, these inspectors visited approximately one hundred training and administrative installations of Air, Ground, and Service Forces, including unit and replacement training centers, air bases, ports of embarkation, and training and maneuver areas of field forces. Reports of each inspection were transmitted quickly to G-3, War Department General Staff, affording that office a timely picture of the state of gas defense training of units remaining in the United States. This inspection procedure did more than inform the staff; it enabled the Chemical Warfare Service to get a clear picture of the strengths and weaknesses of the chemical defense training program of the Army, for which it was technically responsible. Before inauguration of the technical inspections procedure, the rigidity of the three-command organization of the War Department precluded technical branches from gaining intimate knowledge of the status of their specialties within ground and air establishments; after 1943, this situation was greatly improved. The fact that AAF, AGF, or ASF headquarters notified the unit or installation that the CWS inspection team was acting for the War Department was itself a spur to better training and accounted for much of the improvement that was later evident.13

The technical inspections resulted in improved administration of chemical warfare training throughout the Army. Chemical officers were assigned to AGF replacement training centers to insure more effective individual training of replacements in protection against chemical attack. The Army Ground Forces made greater use of the Chemical Warfare School to train combat personnel as instructors in chemical warfare. The Chemical Warfare Service sent a dozen junior officers on temporary detail to special troop sections of corps and armies in an effort to correct chronic weakness in anti-gas training of nondivisional units. Responsibility of post chemical officers in the training of nondivisional units was clarified in 1944.14

Although these measures were helpful, gas defense training remained inadequate. In a report to the Deputy Chief of Staff as late as March 1944, ACofS G-3 (Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter) stated:

As a result of several reports from overseas theaters indicating a deficiency in chemical warfare training, the Army Ground Forces were directed to include chemical phases in all maneuvers of divisions and larger units. ... It is the opinion of this division that chemical warfare training in the Army has not yet reached a satisfactory standard. ... The division will continue to pay particular attention to the progress of chemical warfare training.15

This judgment was made at a time when full-dress rehearsals were being staged for the invasion of Europe and when American offensives already were beginning to roll in the Central and Southwest Pacific. A year later the situation had scarcely improved. A survey of units formally inspected by The Inspector General during the second quarter of 1945 showed 30 percent to be deficient in defense against chemical warfare and 35 percent unqualified in decontamination procedures.16 This was a discouraging picture, coming at the end of two years of intensive effort to improve the readiness of the U.S. Army for gas warfare. Despite explicit directives which eventually were supported by all the pressure that G-3 could bring to bear, the fact remained that gas defense training during World War II did not attain a standard satisfactory to the General Staff. The reasons for this situation are worth considering, since they bear on future training of this type.

Shortcomings in Antigas Training

The apathy with which gas defense training was so often regarded by the ground forces may have been rooted in a basic conviction that gas, like the incendiary, had become primarily an air weapon and that its future employment would be principally strategic rather than tactical. Such views were frankly held by air units and accounted for much of the vitality that marked AAF training in chemical warfare throughout the war. Perhaps the principal reason why AGF preparations for chemical warfare did not more nearly approach the objectives set by the Staff is the fact that many commanders never did take seriously the prospect of gas attack in ground combat.

This attitude, prevalent in GHQ in the early days, became even more

pronounced as the war drew on toward its end. Among the field forces there continued to persist a widespread belief that such comprehensive training as the General Staff demanded was not required. According to the nature and habit of soldiers, this negative attitude, while never openly expressed, still effectively prevented the breath of life from fully entering the antigas training program.

Actually the gas defense program as set down on paper proved to be more comprehensive than circumstances demanded. It undertook to cover more ground than was feasible in view of the psychological factors involved. Until poison gas was really in the air, it was clear that troops would go so far and no farther in energizing protective measures. This fact emerges from an analysis of reports of inspections of gas defense training made by the Chemical Warfare Service during the latter stages of the war.

Notable was a general lack of carefully prepared standard operating procedures for defense against chemical attack.17 There was little or no inclination on the part of units to require the occasional wearing of gas masks at work, in firing weapons, or in tactical exercises. Frequent deficiencies were reported in methods of decontaminating food, water, and equipment. In the field of collective protection, defects in training showed up most clearly, and it was here that the unit commander’s attitude was most influential. If unconvinced of the need for chemical warfare training he assigned chemical officers and unit gas officers to other duties which precluded their attention to gas defense. In half of the units surveyed, gas officers and NCO’s were not well trained so that instruction was poor. In many instances there were insufficient local schools for training of instructors; where there were schools, however, the training was either excellent or superior. Finally, the failure of army and corps chemical officers to make regular inspections of gas defense training in subordinate units, the inspection reports stated, appeared to be a contributing reason for many unsatisfactory ratings since 27 percent of the units inspected reported never having been visited by CWS staff officers.18

Other weaknesses were disclosed by these reports which pointed to defects in the program itself. For example, the basic War Department training guide (FM 21-40) had certain objectionable features. This 271-page manual was too technical for general training use, and failed to differentiate between what should be taught the instructor and what the average trainee

needed to know about chemical warfare.19 The designation of unit gas officers and noncommissioned officers by regimental, battalion, and company commanders was called for in the manual but was not prescribed in appropriate tables of organization. Failure of the War Department to provide more authentic authorization for unit gas personnel led to endless difficulties.

While some failures in antigas training were thus attributable to indifference on the part of local commanders, some were due to improper supervision, and others grew out of defects in the gas defense program. All of these defects would probably have been corrected quickly enough in the event of gas warfare. The antigas training program of World War II should be judged in the light of what it actually was—a preparatory rather than a final defensive scheme. As such, it might be rated as satisfactory. Much of the time employed in this training was at the expense of other types of military instruction. If at times the degree of preparedness achieved appeared excessive to local commanders, it was on the other hand a source of assurance to high echelons—which were much more sensitive to threats of hostile gas attack.

Three trends in gas defense training of the U.S. Army during the course of the war were definite enough to deserve notice. These were:

Simplicity: Elimination of technical and nonessential detail from instructional material employed in basic training.

Concentration: Need for more intensive training of selected specialists, and less chemical warfare training for the Army as a whole.

Differentiation: Frank recognition of the essential distinction between training needed before the employment of toxic chemicals and that needed after a gas warfare phase begins.

In the matter of simplifying instruction, a great deal had been accomplished by the end of hostilities. A move toward simplification of gas defense training was made possible by the introduction of gas detector kits and other devices for indicating the presence of toxic chemicals.20 These lessened the importance that had always been placed on nasal identification of war gases by the individual soldier, a knack which was particularly difficult to teach. Another perennial obstacle in training was the old terminology of toxic agents. This terminology was eventually simplified in line with British practice of grouping casualty agents into three easy

M9 Chemical Detector Kit. Developed at Edgewood Arsenal in 1944, the M9 kit was one of several devices used to determine presence and type of toxic chemicals.

classifications: blister gases, choking gases, and nerve poisons.21 The trend toward more simplified anti-gas training is tangibly indicated by the publication of a graphic training aid which reduced to postcard size a summary of protective measures.22

While the trend during the latter stages of the war was toward curtailing and streamlining basic instruction in chemical warfare, this tendency was accompanied by a rising emphasis on the specialized training of both officers and enlisted men designated as unit gas personnel. The introduction late in the war of a gas officer at the company level indicated at once the continued concern of the War Department in the scheme of gas protection and the need for concentrating instruction in this field.23 Less reliance upon local schools and greater utilization of service schools for training of antigas specialists was evident as the war ended.

Flame, Smoke, and Incendiaries

The need for training troops in the employment of flame weapons arose largely, although not entirely, from the fact that new flame techniques were introduced in World War II. The flame thrower of World War I had serious limitations which restricted its use to very special situations. For this reason the weapon was not regarded seriously by the CWS and its use was seldom taught at service schools. But the development of thickened fuel from 1940 on, together with mechanical improvements, markedly increased the military

potential of flame projection and did so at a time when tactical operations in the Pacific demanded a weapon of this type.

Fuel thickened by napalm and other materials was even more widely used by tactical air than it was by ground forces, once its value as a filler for fire bombs had been determined. Training in flame warfare was essentially technical training in the Army Air Forces; yet with ground forces it had to be both technical and tactical.

Little flame-thrower training of any kind was undertaken in the Army until mid-1943 when flame throwers began to be manufactured and distributed on an appreciable scale.24 While responsible only for the supervision of training in the maintenance and operation of the weapon, the Chemical Warfare Service also became involved in instruction with respect to its tactical use. In 1943 a ten-hour course was introduced at Camp Sibert and given to all replacements. This course covered not only maintenance and operation but also tactical employment of the flame thrower. Many of the replacements who took the course were later assigned to infantry units responsible for the employment of the flame thrower in combat.25

Both the Corps of Engineers and Infantry had a responsibility for the employment of the flame thrower. Engineer responsibility stemmed from its mission of demobilizing enemy fortifications, a type of operation in which flame throwers could play an important role. Instruction on the tactical use of the flame thrower was included in a three-week course, “Attack on Fortified Areas,” given to field grade officers at the Engineer School, Fort Belvoir.26

Instruction in maintenance and operation of the flame thrower was offered in infantry and armored divisions where the commanding generals showed an interest. In these divisions the chemical officers inaugurated courses of instruction for gas officers or a limited number of enlisted men from each company. Generally, the division chemical officer carried on this instruction on his own initiative, but in certain divisions the commanding officer of the engineer battalion cooperated closely with the chemical officer.27

All infantry and armored divisions devoted some time to smoke training

Medium tank equipped with flame thrower firing on entrance to enemy cave. Picture taken on Okinawa, 1945.

although the amount of time varied greatly as between divisions. In the early period of the war the shortage of smoke pots and grenades was a factor in the lack of emphasis placed on smoke training. But the chief factor, as in other phases of chemical warfare training, continued to be the attitude of the individual commander. In some divisions little attention was paid to smoke training at any time during the war, while in others approximately as much time was given to this type training after mid-1942 as to gas defense training.

Training of infantry and armored units in smoke operations emphasized, first of all, the defensive aspects. The chemical officer, in units where smoke training was stressed, had each company march through a smoke screen in order that the men might learn the difficulty of keeping direction. Secondly, the offensive use of smoke was treated. The chemical officer and his staff instructed units in the use of smoke pots, grenades, and colored smokes for marking and signaling. Smoke was employed in battalion exercises and in army maneuvers.

Because of the shortages in the supply of incendiary bombs, particularly

in the early period of the war, little stress was laid on training in defense against this type munition. Most divisions limited their activity to mass demonstrations. In the few divisions where the supply situation was satisfactory, much more time was devoted to defense against incendiaries. In the Both Infantry Division, for example, the chemical officer set up a procedure whereby a number of 4-pound thermite bombs were dropped from trees so that members of his staff could conduct practical training in putting out fires and otherwise neutralizing the effects of the bombs.28 In at least one division, the 75th Infantry Division, each man in each company was trained in the use of incendiary grenades.29

Corps chemical officers were responsible for evaluating the results of chemical warfare training in the divisions of their respective corps. In addition, they conducted such training for nondivisional troops throughout the corps. Generally the corps chemical officer conducted this training in the same manner in which the division chemical officer trained prospective gas officers.30 A unique practice was introduced by the chemical officer of IV Corps, Col. Hugh M. Milton II. In March and April 1942, Colonel Milton established a traveling school which visited training installations throughout the corps. Courses of instruction were drawn up with the assistance of division chemical officers, a number of whom acted as instructors. First to take the courses was the staff of the corps. This was followed by instruction of division personnel, which took ten days. The purpose behind this type of school—it was generally referred to as the “circus”—was to impress the students right at the start of their divisional training with the importance of chemical warfare.31

Supervision of training in defense against gas warfare remained the principal mission of the Chemical Warfare Service so far as training the Army in chemical warfare was concerned. Next came the supervision of training in the use of smoke. This was followed, in order of priority, by training in the use of the flame thrower and defense against the employment of incendiaries.

In summary the effectiveness of training against gas warfare is somewhat difficult to assay, because this type of warfare was not resorted to during the war. That this training, as late as March 1944, was not satisfactory, was

the conviction of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3. That his judgment appears to have been correct is borne out by the reports of CWS inspectors as late as 1945. One of the chief reasons behind this lack of preparation was the attitude of certain ground force commanders who were convinced that gas warfare was not imminent and who therefore failed to emphasize this type of training. In all instances commanding generals of divisions assigned additional duties to chemical officers.

White the attitude of those commanders with regard to gas warfare is understandable, it is more difficult to understand their attitude toward other types of chemical warfare—smoke, flame, and incendiaries. There certainly was no question about the probability of the use of those munitions on the battlefield. Yet throughout the various ground force divisions there was anything but uniformity in the amount of time and effort devoted to this type of training. But perhaps it is possible to censure ground force commanders too severely. Under pressure to conduct training programs of all kinds the commanding generals naturally had to rely upon the advice of their chemical officers. And in some instances the chemical officers were not active enough in “selling” chemical warfare to their commanders.

The training of the Army for gas warfare, conceived of as the primary training mission of the CWS in the prewar years, unexpectedly became a secondary mission in World War II. What had loomed in peacetime as a more or less secondary mission—the training of service type units and re, placements—actually became the chief training responsibility during the war. Of great importance too was the training of chemical mortar battalions which were organized in numbers not contemplated in the peacetime period. Although the ground forces had jurisdiction over these battalions, the CWS had a very active interest in their training. Thus did the exigencies of war and changes in War Department organization and policies make unforeseen requirements in Chemical Warfare training.

Nor was the distinction between plan and reality confined to the training activities of the Chemical Warfare Service. After responsibility for the development, procurement, and storage of incendiary bombs was transferred from the Ordnance Department in the fall of 1941, the CWS undertook a program for which no peacetime plans had been drawn, a program that developed into one of the most important wartime efforts. The assignment of the biological warfare mission to the CWS shortly before the outbreak of war led to large-scale research and development in this new field of endeavor.