Chapter 5: CWS Administration: Pacific

The CWS in the West and Southwest Pacific, 1941–42

Defending the Philippines

After the Japanese attacked Clark Field on 8 December 1941 and brought World War II to the Philippines, Col. Stuart A. Hamilton, Chemical Officer, Philippine Department, the 14 officers, 275 enlisted men, and 12 Philippine Scouts assigned to the CWS in the Philippines immediately stepped up efforts to prepare for gas warfare.1 Intensive preparations for gas warfare in the department had begun the preceding spring with the dedication of a new impregnating plant in the Manila port area for the production of gas resistant clothing. By the day of the attack the department’s defense preparations were in many respects satisfactory, but chemical officers were disturbed that training rather than service masks had been the authorized issue to individual soldiers and that the protective clothing supply was completely inadequate even with the new plant in operation.

Both the U.S. forces and the enemy greatly feared that the other’s next move would be a gas attack. On 8 December the Japanese assault commanders on Formosa issued masks to their troops.2 In Manila, requests for masks poured in to the departmental chemical office. On 10 December General MacArthur’s Headquarters, United States Army

Forces, Far East (USAFFE) , ordered training masks exchanged for service masks. On the same day the CWS began issuing service masks to Philippine Army units. Some training and service masks were later provided for civilian employees of the Army. Chemical troops under 1st Lt. Charles A. Morgan, Jr., operated the new impregnating plant on a 24-hour basis until 23 December, when the power plant was bombed. The clothing was to provide individual protection against expected gas attacks and to equip unit gas warfare decontamination details. About a week later Colonel Hamilton supervised the destruction of the plant, along with supplies and records, to prevent capture. After the loss of the plant, the CWS contingent on Bataan continued clothing impregnation by hand in order to finish equipping the decontamination squads. A day after the plant was destroyed Hamilton moved his office into an improvised chemical laboratory in the Malinta Tunnel, Fort Mills, Corregidor. The CWS hastily completed part of a large gas-proofing project so that the ventilating blowers could be used to make the Malinta Tunnel usable for a hospital, offices, and quarters.

The few CWS officers and men not continuously used as infantry labored mightily to adapt existing materials to emergency needs. Hamilton’s men improvised field plants to produce liquid bleach (chloride of lime) for sanitation purposes both on Bataan and Corregidor. These plants used lime and liquid chlorine originally intended for decontamination of vesicant gases. Bleach was also used as an insecticide by the hospitals, around latrines, and on the battlefields. The field plant on Corregidor continued to operate even after the Japanese occupation. The CWS laboratory assayed and packaged another vesicant decontaminant, high-test hypochlorite, for water purification. The Philippine Chemical Depot staff, operating on Bataan, prepared tiki-tiki extract from rice bran for the prevention and treatment of beriberi and polyneuritis, but an effort to develop a substitute for quinine sulphate was only partially successful. The CWS also converted FS smoke fillings from Livens projectors and 4.2-inch chemical mortar shells into sulphuric acid to keep in operation the storage batteries in electric generator units, radio sets, and vehicles. After an enemy bomb destroyed the first field acid plant and killed four of its five operators, another plant was set up where production continued until the week of the Corregidor surrender. To aid the

fighting units, Lt. Frank L. Schaf, Jr., CWS, assisted by a U.S. Navy detachment, improvised a flame thrower from two 3-gallon decontaminating apparatus. The chemical depot group also contributed to the fighting units thousands of Molotov cocktails hastily improvised from beer bottles and other scrap materials.

When not busy with emergency improvisations, the CWS laboratory analyzed and described captured Japanese materials, such as gas masks and canisters, explosive charges, and flame throwers, brought in by men of the Philippine Chemical Depot. These analyses and descriptions were radioed to OCCWS, and samples of captured equipment were shipped to the United States. When surrender seemed inevitable, the CWS destroyed all remaining chemical materials. Colonel Hamilton and his surviving men were taken prisoner after the surrender of Corregidor on 6 May 1942 and remained in Japanese prison camps for the rest of the war.

Establishment in Australia

On 7 December 1941 the 3rd Chemical Field Laboratory Company was aboard a Pacific convoy carrying units and individual officers and men destined to augment the American forces in the Philippines. On 12 December Brig. Gen. Julian F. Barnes, the senior officer aboard, organized the Army forces in the convoy into Task Force, South Pacific, and appointed a general and special staff. The War Department next day ordered General Barnes’s convoy and task force to proceed to Australia where Barnes would assume command of United States troops. The convoy docked at Brisbane on 22 December, and General Barnes spent the following month straightening out the confused command situation, organizing the United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) at Melbourne, and making desperate and unsuccessful attempts to send troops, aircraft, and supplies to the Philippines. On 28 January 1942 Capt. John C. Morgan, an officer of the 3rd Chemical Field Laboratory Company, set about establishing a chemical section in USAFIA. Col. William A. Copthorne arrived on 2 February with a number of experienced officers and enlisted men. Known as the Remember Pearl Harbor Group, these men were being rushed to the Pacific to serve wherever senior command and staff officers and specialists were needed. Copthorne became chemical officer

and was assigned to the USAFIA chief of staff’s special mission for coordinating relief shipments to Corregidor.3

The CWS, U.S. Army Forces in Australia

Colonel Copthorne and Maj. John C. Morgan, now assigned as Copthorne’s executive officer, tackled the job of setting up a CWS for USAFIA. First, they had to set up and staff the territorial organization in Australia and allocate personnel and units among other organizations, both those already in the area and those being activated. Then there was the task of providing chemical supplies for American forces. The third undertaking was the establishment of CWS planning and training functions. And the fourth act was to expand and supervise CWS technical and technical intelligence functions established by the laboratory company.

Six numerically designated base sections with headquarters at Darwin, Townsville, Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth were set up on 3 March 1942. The seventh base section was established at Sydney in the following month. Sixteen CWS officers arrived in April, and Copthorne managed to assign one or two officers and one or two enlisted men to the chemical section of each base section, after a brief period of training and orientation in his own office. Chemical officers, like other base section special staff officers, were directly responsible to their chief of service in matters of plans, policies, and supply, but they served the additional function of advisers to base section commanders under whose administrative control they worked. Since the original intention of the Australian establishment was to support Lt. Gen. George H. Brett’s Far East Air Force, Copthorne and Morgan, who held a second position as chemical officer in the Air Section, USAFIA, also sought to provide chemical manpower and service for the air forces.4 His ability to accomplish such work was severely

limited by lack of officers and men and by a lack of information as to air forces chemical organization and duties. The information finally arrived from OCCWS in July, and two months later the theater acquired enough personnel to activate four chemical air operations companies, using detachments and a platoon of the 3rd Chemical Service Company (Aviation), already in the theater, as nuclei.5

Organizing the Chemical Section, U. S. Army Services of Supply

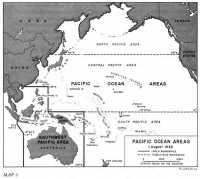

In March 1942 Allied leaders designated the Pacific as one of the three main theaters for prosecuting the war against the Axis. The Joint Chiefs of Staff in turn subdivided the Pacific into areas: the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) from Australia to the Philippines, and the Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) to the east of the Philippines, the Netherlands East Indies, and Australia. (Map 2) POA was again subdivided into North Pacific Area, Central Pacific Area (CENPAC) (including the Hawaiian, Gilbert, Marshall, Mariana, Bonin, and Ryukyu Islands) , and South Pacific Area (SOPAC) (including New Zealand and New Caledonia). POA came under the command of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz who designated a deputy to head the South Pacific Area. In April MacArthur, now in Australia, organized GHQ, SWPA, an Allied and supreme command over all air, land, and sea forces in the area.6 The Southwest Pacific Area was not technically a theater but GHQ, SWPA in mission and responsibility was an Allied headquarters as well as the senior American strategic and tactical headquarters in the area. After the creation of GHQ, USAFIA became a supply and service headquarters,7 redesignated United States Army Services of Supply (USASOS) in July. Copthorne retained his position in USAFIA and its successor. Although he was regarded as chief chemical officer for the U.S. forces, he had no direct role in GHQ. By 1 July Copthorne and Morgan had their section in operation. The

Map 2: Pacific Ocean Areas

technical function, involving liaison with Australian chemical warfare authorities, and the supervision of the chemical laboratory, recently redesignated the 42nd Chemical Laboratory Company, Copthorne exercised through his technical and intelligence officer, Maj. Walter W. F. Enz. Capt. Arthur H. Williams, Jr., handled fiscal and administrative matters, including supply, and was purchasing and contracting officer for the CWS. Capt. Carl V. Burke was operations and training officer. One other officer and three enlisted men completed the section.8

Copthorne was the only CWS Regular Army officer in SWPA, not only at the time of organization but also for another year. A Military Academy graduate, he was 52 years of age at the time and had seen service in World War I but not overseas. He had a variety of chemical experience, including a tour as Philippine Department chemical officer, a tour as a corps area chemical officer in the United States, and had most recently been an instructor at the Army’s Command and General Staff School.9

Supply was a very difficult matter to handle. Since there had been no preplanning for a theater headquarters based in Australia, all supplies obtained in the early period were destined for arriving organizations. There was no theater reserve. American forces supplies and services of all kinds were obtained from the Australians when possible through a necessarily complicated series of procedures which prevented a fatal drain on the Australian economy and which precluded competition among American and Allied forces for available goods and services. Captain Williams had little to work with; Copthorne wrote to OCCWS that he could determine neither theater strength nor the availability of supplies in the hands of troops.10

The Theater CWS School

The training job was more readily, although not easily, handled. Copthorne urged all base section chemical officers to give the troops as much chemical training as possible. Many of them were too shorthanded to accomplish much training outside their immediate headquarters, but Maj. Burton D. Willis, Chemical Officer, Base Section 3 in Brisbane, had a larger staff, and he could call upon the 42nd Chemical Laboratory Company (formerly the 3rd Chemical Field Laboratory) . He gave several courses in chemical warfare defense, using a classroom in the University of Queensland. Although base section training was on a part-time basis, such training was a good foundation on which to build, and Copthorne dispatched Captain Burke to open a theater school. On 12 July 1942 Burke reported to the Brisbane base section headquarters to establish a chemical warfare school for all American forces. Since no authority existed for such an establishment, Burke

officially assumed the operation of the base section school while in fact preparing for the establishment of a SWPA CWS school. The first class with thirty-three unit gas officer students was in session before the school was approved in August, and the third class, also of unit gas officers, was ready to graduate before September, when the school officially became a theater activity as part of the Chemical Warfare Service Training Center.11

Burke started his school in a converted private residence with one officer and two enlisted assistants. He called on Willis, soon promoted to lieutenant colonel, on officers of the laboratory company, the 62nd Chemical Depot Company, and on the 10th Chemical Maintenance Company to assist him with instruction. In the following year, with a peak staff of five officers, the CW school conducted thirty courses, including those for unit gas officers, unit gas noncommissioned officers, and special, technical, decontaminating, and demonstration courses for other soldiers. These courses, usually of two weeks’ duration, graduated nearly 1,000 students.12 But even this accomplishment was not equal to the task at hand of training and retraining SWPA forces in defense against gas warfare. Even before the school started, Copthorne drew upon his meager supply of officers, again supplementing them with details from the chemical service units, to establish four mobile training teams for the purpose of instructing widely dispersed units in chemical warfare defense. In driving home instruction these training teams demonstrated chemical warfare defensive and decontaminating equipment and tested procedures in which live toxic agents were used. The demonstrations and tests were usually given at company level for selected officers and NCOs. Length of instruction varied from a few hours to two days, according to the company’s needs and schedules!13

The training teams, like the school, were attached to the Chemical Warfare Service Training Center, which was supported by the base section headquarters at Brisbane. The training center, in addition to administering the school and the teams, also arranged or conducted special cooperative instruction and demonstrations which called for

Annex building, Chemical Warfare School, Brisbane, Australia

more equipment or a greater instruction load than the school or the teams could handle individually. Standard U.S. training aids and equipment were not available. Major Enz acquired a small laboratory at the University of Melbourne and manufactured gas identification sets using commercial materials and toxics furnished by the Australian and American Armies. Instructors or chemical service units fabricated other equipment and aids. The school got very little instruction and no materials from the United States, but it did benefit by an exchange of information with the Australian Antigas School near Toowoomba.14

The newly established training facilities were used by the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions, first American tactical ground forces organizations in the theater. The 41st Division had reached Australia on 7 April 1942, and the 32nd Division on 14 May 1942. Both organizations

included chemical sections, the 41st section headed by Maj. Frank M. Arthur, and the 32nd section by Capt. Edward H. Sandell. Both of these officers established division chemical warfare schools.15

When General MacArthur converted USAFIA into USASOS on 20 July 1942, general and special staffs retained their responsibilities virtually unchanged. Such reorganization as was accomplished was apparently intended to bring USASOS into line with a War Department directive for theater communications zone organization.16 Copthorne felt that there should be a chemical officer in General Mac-Arthur’s GHQ, but, he also felt that for the time being his location in USASOS permitted him close supervision of the matters in which the CWS had the greatest immediate concern.17 A position in GHQ would presumably have been an Allied staff position similar to the one which Shadle had just taken over in AFHQ. Since there was no World War I precedent and since Shadle’s was the only such CWS appointment in World War II, a like appointment in GHQ would have been unusual.

CWS Functions

CWS functions of immediate concern were those of personnel, supply, and training, as they had been earlier; but now Copthorne also had reason to become deeply interested in the technical preparations for gas warfare. As theater chemical officers the world over were then discovering or were about to discover, he had found that they had “almost an independent Chemical Warfare Service out here.”18 The manifestation of this independence in SWPA was not, as in other theaters, in the realm of supply, but rather in the provision of technical chemical information to all forces in the theater and in the exchange of information with the Allies. As far as supply was concerned, the time lag between the United States and the theater was so great that the individual service could as yet do little to influence shipments. Distribution within the theater was tightly controlled by USASOS since critically short transportation had to be centrally controlled. In technical matters, however, Copthorne had charge of the only full-fledged laboratory in the theater, and he strongly believed that it was

Colonel Riegelman

to the advantage of the service for this laboratory to handle any technical problem referred to it. Since the Japanese had reportedly employed gas in China, since they were apparently logistically capable of mounting a gas attack, and since it would be to their advantage to initiate such an attack before the American defenses were organized, Copthorne also believed that the Japanese might initiate gas warfare at any time. This possibility, he felt, called for active intelligence work and extensive technical investigation of the characteristics of available munitions in the theater’s tropical environment. He also saw the need for improvising new munitions and techniques to be used before supplies and information became available from the United States.19

In order to meet the technical portion of his functions, Copthorne had set up a Technical Advisory Board to maintain scientific liaison with the British, the Australians, and within the U.S. forces, and to advise the laboratories. Also, several of Copthorne’s subordinates had begun munitions testing. Two of them, Capt. Richard H. Cone and Lt. James W. Parker were killed in an air accident while carrying out experiments to determine whether incendiary bombs could be improvised from training bombs, using gasoline thickened with crude rubber as a filling.20

In September 1942 the chemical section went along with USASOS headquarters to Sydney, but the change in location made little change in the section’s operation. In the following month the chemical section began circulating a mimeographed Chemical Warfare information bulletin designed to apprise officers in the field of technical and intelligence developments.21 Also, during this period Headquarters, I Corps, under the command of Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, arrived in

Australia to become the senior tactical American ground command. The I Corps chemical officer was Col. Harold Riegelman, a distinguished New York attorney who had served in World War I as a gas officer and had since been prominent in Reserve activities. In the words of his commander, he was “a loyal efficient staff officer with an analytical brain who pursued his work with diligence.”22 Riegelman’s section included an officer assistant, a warrant officer, and six enlisted men.23 On arrival in Australia, Colonel Riegelman at once began to lay plans with Major Arthur of the 41st Division, and to await an opportunity to confer with Captain Sandell of the 32nd Division.

CWS Baptism—The Papua Campaign

This opportunity never arose. Two regiments of the 32nd Division had been ordered forward to New Guinea in September, and on 18 October Sandell, T/Sgt. John K. King, and Sgt. Raymond F. Dasman, as the advance detail of the chemical section, reported to their commanding general at Port Moresby on the southern tip of New Guinea.24 Sandell’s was among the first chemical sections to participate in combat in World War II after the fall of the Philippines. The duties performed by the 32nd Division Chemical Section, while they might not be categorized as either administrative or staff work, which were theoretically the section’s main responsibilities, demonstrate the ingenuity with which chemical sections in many combat elements in all parts of the world approached and defined their tasks.25

Sandell and his sergeants spent a few days in the Port Moresby area locating the chemical equipment which the regiments had discarded on landing. Most of the equipment was in a deplorable state, having been scattered in odd piles about Port Moresby and exposed to the elements. The gas masks, approximately 5,000, had been collected and put under cover. USASOS had established a forward base at Port Moresby, but the base chemical officer, inexperienced and recuperating from malaria, had been unable to locate either the labor or the materials

to build storage places and to collect and store other equipment. Nearly all troops in the area had been fighting to repel the Japanese invasion until a short time before Sandell’s arrival.

Sandell managed to get a 10-man detail from the 107th Quartermaster Battalion, then assigned to the Port Moresby base, and with this help he and his men gathered, inspected, and stored any matériel that gave promise of serviceability. Sandell and his men were also given the mission of searching the jungle to discover if any native garden or jungle foods could be found to supplement the ration. From 8 to 21 November Sandell attended the New Guinea Force school on jungle tactics as a student and presented briefings on chemical warfare as an instructor.

On 27 November Sandell was ordered forward to the Buna-Gona area, where an assault had been launched ten days earlier, to see if chemical smoke or incendiary supplies would be useful in pushing the attack. The assault was going badly because locating the enemy in his cleverly camouflaged positions was difficult and driving him from well-fortified bunkers with the weapons available was almost impossible. To get a line on enemy fortifications and master the assault problem, Sandell led a patrol to a point south of the Buna Mission.26

He returned to Port Moresby, joined forces with Sergeants King and Dasman, and together they collected HC smoke pots, Australian rifle smoke grenades, thermite aerial bombs, blasting powder, gelignite, safety fuzes, detonators, and friction tape. Back in the fighting zone on 4 December, they set to work improvising hand grenades from the rifle smoke grenades. They had some difficulty persuading infantrymen to use them until an infantry captain demonstrated that it was safe to pass through the smoke released by two grenades thrown directly in front of an active bunker. The grenades were then much in demand.

On 7 December 1942 men of the 114th Engineer Combat Battalion brought forward the first two portable flame throwers to arrive in the combat area. Despite King’s one attempt to put the flame throwers in operating condition, they failed to fire properly. Flame throwers were not again used in the Papua Campaign.27 After receiving chemical and ordnance supplies on 11 December, King and Dasman refined their modified smoke grenade. Persisting in spite of a number of false starts, they also produced a dependable Molotov cocktail and developed a

hand-thrown concussion torpedo capable of killing all the occupants of a large bunker. After combat testing the improvised weapon, the 127th Infantry requested all the torpedoes the CWS sergeants could manufacture.

Captain Sandell was killed in action on 26 December 1942, and Dasman became a victim of malaria. King carried on at the front until the division was relieved late in January 1943.28 The initiative and resourcefulness of Sandell and his men fitted in well with the concept of the CWS developed by Fries and Porter.

The Principal Mission—1943

Preparedness for Chemical Warfare

In February 1943 Riegelman visited New Guinea to assess the combat situation. He felt that Sandell and his men had done a fine job under extremely difficult circumstances, but he was disturbed by the lack of chemical weapons and the evidences of the poor use of smoke in the whole campaign. Like Copthorne, he was firmly convinced that the chemical officers should learn what effect gas would have in the tropics, and he agreed with Copthorne that the best place to find out was on the spot. While he believed defensive training was better than it had been in World War I, he was still concerned about the adequacy of both training and equipment since he believed the Japanese to be capable of using gas, and feared that even if they did not, some of the jungle odors might cause gas scares, which like an actual attack would result in panic if more specific training was not given. Riegelman reported his observations to his superiors and set to work in corps headquarters to provide remedies to the problems he foresaw.29

Copthorne likewise continued to be much concerned with the tactical problems of preparedness, but he believed that his position in USASOS prevented him from acting adequately in the tactical and planning field. In February 1943 he and his section moved up to the newly reconstituted U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, a headquarters somewhat comparable to the army theater headquarters in Europe and North Africa. He took with him to Brisbane Lt. Col. John C. Morgan,

recently promoted, Major Enz, and three other officer assistants. Lt. Col. John C. Morcock, Jr., became Chemical Officer, USASOS, serving with Captain Williams and two other officer assistants.

Copthorne still felt that he should be in GHQ where the chief engineer and chief signal officer resided but recognized that although the new USAFFE was a headquarters without tactical functions, it at least promised to offer a better place for gas warfare preparedness planning than USASOS.30 USAFFE headquarters did not offer channels for formal coordination of the preparedness effort with Australian chemical warfare authorities. Although informal relationships with the Australians were good, Copthorne strongly felt that there should be a formal relationship, particularly since the Australians found it possible to communicate through their technical channels with the chemical warfare establishment in England, and thereby with the CWS and with the U.S. Chemical Warfare Committee in the United States. Copthorne himself had found neither a command nor a technical channel which permitted easy communication with the technical and planning authorities in the United States.31 The Australians had established a Chemical Warfare Service early in 1942 which like the British counterpart was a joint effort of their army, navy, and air force. Lt. Col. F. S. Gorrill of the British establishment was on duty in Australia, and in 1943 he undertook an investigation of gas warfare in the tropics.32

Staffing Problems

The move to higher headquarters and the completion of the first theater gas warfare plan in March33 again brought to the fore the problem, which had been troublesome from the beginning, of providing a chemical staff. Copthorne had still received no allotment of officers in which each officer was earmarked for the kind of job he was intended to fill. The only officers with appropriate rank, military education, and experience to fill the top positions were Col. Carl L. Marriott who arrived in April as Chemical Officer, Sixth Army, and Colonel

Riegelman. Both men already had important posts and were unavailable to the theater organization. By the end of July 1943, no requisition for CWS personnel channeled through the USAFFE G-1 had yet been filled. Copthorne took the view that most of the young Reserve officers assisting him were doing excellent, and in some cases, outstanding work, but in implementing and revising the theater gas warfare plan and the training responsibilities which were growing daily, he had no one with sufficient rank and experience to handle the operations (planning) tasks. Furthermore, a large part of offensive gas warfare planning had to originate with the air forces where preparation for the retaliatory effort would be concentrated. Neither in USASOS nor in USAFFE did Copthorne have any power to control the Fifth Air Force, which reported to GHQ through Allied Air Forces. His relationship with Maj. Walter C. Weber, Fifth Air Force Air Staff chemical officer, was so cordial that he could practically consider him as an assistant, but Weber, then the only field-grade chemical officer in the Fifth Air Force, had his hands too full with supply and service functions to give any deep consideration to long-range planning.34

In the face of such problems, Copthorne increased his strength as best he could. It had been demonstrated by the time of the move to USAFFE that the existing organization for securing chemical technical intelligence through unit gas officers and NCOs was ineffective. Copthorne accordingly assigned Maj. John A. Riddick, who had been Enz’s assistant, to head a new Intelligence Section in his office. He charged Riddick with securing six junior officers and twelve NCOs to organize and train six technical intelligence teams. Riddick found the officers and men and brought them into the USAFFE Chemical Section for training. At the same time the headquarters rule that all captured equipment must be channeled to the Australians was relaxed. The teams soon went out on attachment to combat units. Riddick compiled their findings, together with laboratory analyses and descriptions of captured enemy equipment, and forwarded the resulting report to chemical officers and unit gas officers as well as to the headquarters of other theaters and areas in contact with the Japanese.35

At the same time the CWS SWPA began to rotate chemical officers among assignments so that as many officers as possible could have field

Colonel Marriott examining Japanese gas mask

and staff experience. Lt. Col. Robert W. Smith became Morcock’s executive, and Maj. Irving R. Mollen came from Base Section 3 to be his supply officer. The Melbourne base section chemical officer came in to be supply officer in the USAFFE section for a few months and then returned to Melbourne. Another field officer was assigned to a brief tour as operations and training officer in the Chemical Section, USAFFE, before becoming commandant of the school. Maj. Carl V. Burke replaced Colonel Morgan as executive officer in the USAFFE section after Morgan became CWS Liaison Officer with the Australian Army, a position established in place of formal coordination. Colonel Willis moved from Brisbane to Townsville since Townsville was the base most actively in support of forward operations. He then served a short tour in the Advance Section, USASOS, in New Guinea, and returned to Townsville. Morcock moved out to become chemical officer of the Advance Section and Colonel Smith took his place in USA SOS.36

Coordinating the Theater CWS

Copthorne felt the CWS in the United States should provide gas warfare technical and preparedness doctrine for the tropics, or else that it should assist him and his colleagues in the Pacific areas in formulating such doctrine, but he was not satisfied that his appeals for help had received sufficient attention in the United States.37 He found communication with the Central Pacific Area chemical staff too difficult in 1943 to offer adequate opportunity for coordinated study of chemical problems, but his colleagues in the South Pacific were closer

and had more experience with tropical warfare so there the opportunities for exchange of information seemed better. The Chemical Section, U.S. Army Forces in the South Pacific Area (USAFISPA), had been organized by Col. Leonard J. Greeley in August 1942. In November 1942 Greeley was designated Deputy Chief of Staff, USAFISPA, and Lt. Col. Joel L. Burkitt became chemical officer. While the USAFISPA Chemical Section had been hampered by shortage of manpower, lack of chemical materials, and the perpetual Pacific problems of difficulties in communication and transportation, its staff, as Copthorne knew, had kept in close touch with the combat organization chemical officers.38

Copthorne decided that he might be able to accomplish gas warfare doctrinal formulation by “committee.” He accordingly invited Greeley and Burkitt along with the principal chemical officers in SWPA to a conference at the SWPA CWS school from 1-3 July 1943. Col. Robert N. Gay, Chemical Officer, XIV Corps, then in SOPAC, joined Greeley and Burkitt. From SWPA came Marriott, Riegelman, Lt. Col. Lyle A. Clough, Chemical Officer, 32nd Division, Lt. Col. James O. Andes, who was soon to replace Clough, and Major Arthur, along with principal members of the USAFFE and USASOS staffs. The conference first “defined” the tropics in terms of the effect of prevailing meteorological conditions and terrain on gas warfare. Next the conferees observed demonstrations of incendiary, flame, and smoke weapons and munitions. They then spent a day on tactical gas warfare requirements and a half a day on tactics of smoke employment. The meeting concluded with a half-day session on ammunition supply requirements. The principal value of the conference appears to have been that the chemical officers were able to agree on what they did and did not know. What they did know or were able to conclude concerning the performance of available munitions in the tropics was stated as area tactical doctrine for the employment of chemical agents and weapons. A list of items related to munitions performance characteristics about which they were in doubt was drawn up for investigation in the theater or referral to OCCWS.39

As Riegelman expressed his views on the conference, “Everybody

profited enormously. Everybody contributed values from his own experience.”40 But in retrospect, the conference was more significant than its immediate value in providing a forum for the exchange of experience and as a means of formulating temporary doctrine would indicate. Its significance lay in the fact that it presented practically the only means of integrating the CWS in SWPA. It accomplished for Copthorne a measure of the coordination of effort which Rowan achieved in the ETO through supply control and continuous personal liaison. It was less successful as a means of control than Rowan’s because a conference is a transitory affair, and in the SWPA the means of sustaining its coordinating benefits were few. The organization of the SWPA forces, the tremendous physical distances over which the forces in the theater had to move troops and matériel, and the continuing difficulty of communication within the theater and with the United States all militated against maintaining a continuously coordinated effort. Copthorne could only hope to provide a link between research and the firing line by enlarging and continuously revitalizing his two greatest sources of strength, control of technical intelligence and authority to advise on, and sometimes even to make, CWS personnel assignments. He also still sought to build up the function of formulating supply policy and the capability of planning within his own staff.

A temporary hitch in the operation of Copthorne’s plans came in September 1943 when he and the other service chiefs were transferred back to USASOS. Except for about two weeks’ confusion attendant upon the move, the transfer had little impact on Copthorne’s functions because the promise of improved prestige and capability and of better lines of communication in USAFFE had not been fulfilled. An officer remained in the G-4 office in USAFFE as CWS representative. The reorganized USASOS office included Enz, Burke, and Riddick in their respective technical, training, and intelligence positions. Smith became supply officer and Mollen remained as his assistant. A lieutenant colonel recently arrived from the United States became operations and training officer. Two other officers and two warrant officers completed the section. Intelligence trainees were transferred to the 42nd Laboratory for further training.41

Preparedness—The Theater CWS Situation at the End of 1943

After the period of adjustment, prospects for the chemical section became brighter. Lt. Col. John P. Youngman, a supply officer with considerable background and experience whom Copthorne had long wanted in the theater, arrived from the United States to take over the supply position. Colonel Smith became Copthorne’s deputy. Maj. Jack F. Lane, a young officer with a training background, arrived to take a training center assignment. Lt. Col. Augustin M. Prentiss, Jr., a vigorous, young (28 years old) Military Academy graduate with infantry, CWS, and air experience, also arrived from the United States to become Chemical Officer, Fifth Air Force. Major Weber became Chemical Officer, V Air Force Service Command, thus giving Prentiss an opportunity to devote his time to planning and policy.42

Lt. Col. Donald G. Grothaus and Maj. Richard T. Brady of the Field Operations staff, OCCWS, agreed with Copthorne’s estimate of his problems and accomplishments during their visit to the theater late in 1943 and early in 1944. Grothaus agreed with Copthorne that the Pacific was the most likely area for the initiation of gas warfare, and he pointed out, as Copthorne had, that the CWS deficiency of knowledge as to the employment of gas in the tropics was a serious drawback in planning and could well be a vital defect should actual gas operations commence.43 He also noted that Prentiss was hampered in planning for gas warfare retaliation by a lack of information on the effectiveness of toxic munitions in a tropical environment.

Grothaus praised Copthorne’s policy of setting the service units, such as the chemical laboratory, to work on any technical problem within their range of competence whether the solution would have chemical significance or not. He believed that these services performed for a number of theater elements had added significantly to the respect for and acceptance of the CWS in the theater. Other factors increasing respect resulted from four successful Fifth Air Force smoke operations

in New Guinea,44 and from excellent liaison with the Australian forces. One CWS officer, Capt. Howard E. Skipper, had been sent to work in the Australian Chemical Warfare experimental station, and Grothaus believed that the CWS should provide more help, both in manpower and materials, to further the Australian experiments on gas in the tropics. Another source of increased respect was the record of the 4.2-inch chemical mortar battalion in the South Pacific Area. In the United States this mortar battalion had been assigned to SWPA, but since the SWPA chemical staff was not informed that the unit was authorized to fire high-explosive shells nor that such shells were available, the battalion had been given so low a movement priority as a gas warfare unit that it was diverted to SOPAC.45 Reports filtering into SWPA on the effectiveness of the chemical mortar using high-explosive shells made several ground commanders eager to obtain battalions for their own employment. On the debit side, Grothaus, again as Copthorne had, deplored the poor condition of CWS matériel arriving in the theater and indicated that OCCWS action to improve the situation was imperative. Also, despite some recent improvements in the manpower situation, SWPA still had a greater shortage of experienced officers than any other major theater. While strict theater personnel ceilings prevented large additions to the theater CWS complement, Grothaus was of the opinion that in future shipments OCCWS could do much to make up in quality what was lacking in quantity.

Major Brady, whose specific mission was to investigate intelligence, was so impressed with Major Riddick’s accomplishments that he forwarded to OCCWS Riddick’s schedule for training technical intelligence teams. Brady recommended that these teams be trained in the United States. He visited some of the teams which had begun to operate in forward areas with command sanction early in November and approved their activities.46 The intelligence teams were a valuable aid to the CWS SWPA for the remainder of the war. Copthorne later

commented that the organization for intelligence was so effective that it should stand as an example for all similar theater activities.47

CWS, Southwest Pacific Area, 1944–45

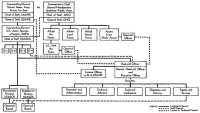

The year 1944 was somewhat paradoxical for the Office of the Chief Chemical Officer, USASOS. On the one hand, the supply situation was good; the condition of equipment had improved; planning capabilities improved throughout the year; training was progressing smoothly; technical intelligence was working well; and technical investigations continued to produce worthwhile information. On the other hand, until late in the year, the advance of forces toward the Philippines put increasingly greater distances between Copthorne’s immediate staff and the CWS in the field, thereby making communication increasingly more difficult. Even the advanced echelons of USASOS communicated more readily with the combat forces than with their own main echelon. Thus, while the USASOS Chemical Section was successfully accomplishing its aims and missions, the chief chemical officer, because of the organization of the theater and its physical setup, had a less important role in the operation of the theater CWS as a whole. (Chart 7)

A Solution for Technical Planning Problems

Copthorne made a trip to Washington in the spring of 1944 for consultations in OCCWS, where he gave special attention to his manpower and planning problems. Lt. Col. William A. Johnson, an officer whom Copthorne had several times requested, arrived in the theater during Copthorne’s absence to take over the operations and training functions. In June the theater gas warfare plan was revised, and the revision indicated a considerable improvement in the theater situation both with respect to supply and plans. Technical and munitions performance information was still deficient, but a team of two officers sent out to SWPA by OCCWS had made a preliminary survey of requirements for information on gas warfare in the tropics just before Copthorne’s departure, and OCCWS was soon to set up a project for assessment of gas in tropical situations in the western hemisphere.48

Chart 7: Organization of Chemical Section, Headquarters, United States Army Services of Supply Southwest Pacific Area, 1 June 1944

Source: Adapt d from: SWPA Personnel and Administration, CWS 314.7; Organizational Manual, U.S. Army Services of Supply, SWPA, revised 1 Jun 44, ASF 200; Cannon, Leyte: Return to the Philippines, P. 25.

By the end of 1944 the SWPA gas warfare planning enterprise at last reached the echelon where it had been in theory but not in fact for three years.49 Copthorne personally went on temporary duty with G-3, GHQ, to make another revision of the gas warfare plan. This superior headquarters could coordinate the activities of the ground, naval, air, and service commands affecting plans for gas warfare. The remaining technical problems were also approaching solution. In November 1944 the theater and the Allies concurred in a proposal forwarded to the theater by General Waitt for the establishment of a Far Eastern Technical Unit (FETU) to investigate the performance of toxics and toxic munitions in the theater. Enz had originally suggested such an establishment to OCCWS. FETU, under the command of Lt. Col. John D. Reagh, completed its tests and analyses during 1945 and in the process furnished needed planning data to the theater. The unit employed officers and civilian scientists from the United States and drew upon the theater CWS for assistance, service, and supply.50

Theater Training—Final Phase

The Chemical Warfare Service training center continued to be a SWPA focus for chemical training during 1944 although corps and division courses had become common in the latter half of 1943. Early in 1944 the distance of most combat units from Australia made it impractical to send large groups back to Brisbane. A new Chemical Warfare Service training center was therefore established at Oro Bay in New Guinea. At first the school remained at Brisbane, but gave some assistance in conducting courses at Oro Bay. About the middle of 1944, a little less than two years after its establishment at Brisbane, the school moved to Oro Bay where it remained until early in 1945. The Chemical Warfare Service Training Center and the school were subsequently re-established in the Manila area, but the war ended before the school was in full operation.51

In the Oro Bay location, the training center and school came under the jurisdiction of the Chemical Officer, Intermediate Section, USA-SOS. Intermediate Section (later New Guinea Base Section) was a forward area service and supply command with jurisdiction over all

but the most forward bases. Copthorne had secured the transfer of Colonel Gay from SOPAC to SWPA in December 1943 to be Chemical Officer, Intermediate Section. In January 1944 Colonel Gay became chemical officer of an advanced headquarters of USASOS and Burke, recently promoted to lieutenant colonel, became Intermediate Section chemical officer. In this position, Burke was in charge of direct support to the combat forces as supplied by the New Guinea bases. This was a difficult position since the occupant in effect served two masters. General instructions and command came from USASOS, but decisions on allocation of resources and requests for supply, services, and training came primarily from Sixth Army.52

The CWS in the Combat Forces, 1944–45

The SWPA combat forces had from the beginning enjoyed a greater degree of independence than most similar forces elsewhere in the world because the nature of the area, as noted earlier, made closely coordinated operation extremely difficult. The independence, at least with respect to chemical matters, increased throughout 1944. Sixth Army was the principal U.S. Army ground combat organization in the theater in 1944, although Eighth Army was to be organized late in 1944 and to become operational in 1945.53 Colonel Marriott presided over the Sixth Army chemical establishment. Maj. Leonard L. McKinney was assistant, deputy, and frequently operations officer, for Colonel Marriott.54 The Sixth Army Chemical Section included a supply officer with one or sometimes two assistants, and usually an operations officer. Colonel Marriott was invalided home in mid-1944 and was replaced by Col. John R. Burns.55

The Sixth Army Chemical Section had a major hand in determining tactical policy, and it not only allocated incoming resources among the supporting bases, but also allocated resources among subordinate combat organizations. The allocation duties meant distributing to Sixth Army organizations such combat units as the chemical mortar

battalions, which belatedly became available to the theater with the activation of one battalion and the arrival of another in mid-1944, and of such service units as were available. But service units were not readily available. When, late in 1943, Marriott asked Copthorne how he might obtain one of Copthorne’s service units, Copthorne wrote, “you might just as well have nonchalantly asked me how you could get my right arm or even my bed at Lennon’s.56 Copthorne was understandably reluctant to give up any service unit since USASOS units were already thinly spread in detachments in an attempt to meet supply and service requirements. But even had he been willing and able to release a unit, the organizational cleavage between service and combat forces was so deep that USASOS did not feel that it was responsible for supplying units to the combat forces. It was USASOS policy to retain its badly needed units.57 Eventually, USASOS policy was changed to permit the release of one unit in January.58 Sixth Army parceled out this unit, and later others, in detachments to divisions to service flame throwers, recondition shell, and handle supply. These detachments were subsequently converted into cellular units, that is, units composed of smaller self-supporting elements, to perform the same functions.

Colonel Burns and Col. Ralph C. Benner, Chemical Officer, Eighth Army, continued to work on the problems of chemical tactical policy and of allocation of men, units, and materials for the remainder of the war in the Pacific. They had the job of receiving and evaluating plans and requirements which originated in echelons subordinate to the army headquarters. They, in turn, translated these plans and requirements into the concepts of the whole organization, coordinated them through staff in their own headquarters, and dispatched them through command channels to GHQ. Using both technical and command channels, the Army chemical officers received reports of chemical activities and problems and maintained continuous inspections to insure the greatest possible effectiveness at field levels.59

Below army level, 1944 and 1945 saw the culmination of a great change which had taken place since the tragic and heroic

improvisations of the 32nd Division Chemical Section in the Papua Campaign. USASOS and Sixth Army managed during 1943 and early in 1944 to obtain a sufficient supply of essentials such as smoke pots, hand grenades, 4.2-inch chemical mortar shells, and individual protective equipment. Colonel Riegelman in I Corps and his subordinates in the divisions plunged into training and tactical work, and by the time of the Hollandia operation early in 1944, they had defensive training of the individual soldier well in hand.60 I Corps had also officially adopted a policy of using smoke shell to provide a target area marking system. Riegelman secured approval for the concept of attaching a mortar company to each assaulting division under the operational control of the division chemical officer. The misuse of smoke concealment which Riegelman had found in his first tour in New Guinea had been corrected by troop training and by orienting commanders.61

Flame thrower techniques had also been perfected, and the weapon itself had been improved through the extraordinary efforts of both USASOS and field chemical officers and men. The weapon still had its faults and maintenance and repair problems were to plague SWPA forces for the duration of the war. With respect to tactical employment of the flame thrower, Sixth Army declared that the weapon logically belonged with the infantry rather than with the engineers, who had brought it into the Pacific. Both Sixth Army and I Corps developed an infantry team for the tactical employment of the flame thrower, and Sixth Army officially set up a team training program which was materially aided by a roving demonstration team organized by Colonel Gay in the USASOS advanced echelon.62

Other corps chemical officers, Col. Francis H. Phipps, X Corps, Lt. Col. John L. Bartlett, XI Corps, and Lt. Col. Richard R. Danek, XIV Corps,63 like Riegelman who was replaced by Col. Frank M. Arthur in 1945, for the most part performed tactical and training functions. They concerned themselves with supply only with respect to critical

items, such as the gas mask and 4.2-inch mortar shell, or in emergency situations. Depending on the training and talents of each officer, corps chemical officers also performed a variety of staff and operating tasks not directly related to chemical warfare or completely unrelated, depending upon their capabilities. Riegelman, who had been an infantry officer as well as a gas officer in World War I, did a study on the reduction of Japanese cave defenses on the island of Biak, an operation which had combined infantry and chemical techniques.64

Division chemical officers had their hands full.65 As their top priority function, they were directly responsible for gas warfare training of every man in the division. They accomplished what training they could through their own sections and also made use of traveling training teams. By these means and by sending quotas (ideally, one officer per company and one noncommissioned officer per platoon) of unit gas officers and gas noncommissioned officers to theater and other schools, they could train UGOs and UGNCOs and in turn help them establish unit schools and training periods. The training activity was a constant one since malaria, battle casualties, and ordinary shifts in personnel frequently necessitated the establishment of an entire new roster of UGOs and UGNCOs who would likewise be required to give instruction down to the last private in the last squad. Corps chemical officers and command inspectors checked on divisional chemical training periodically.

The division chemical officer’s duty of next priority was supply. He cleared requirements statements for gas masks and other protective supplies, smoke pots, grenades, mortar shell, and various items of chemical equipment with the division G-4, and, if necessary, with the Ordnance and Quartermaster officers. When supplies were received

or in transit, the chemical schedule in loading, storage, issue, and service plans had to be cleared again with general and special staff officers, and the actual operation of supply followed down to the regimental and special staff levels. Division chemical officers in the Pacific found that cooperative plans, sometimes employed in other theaters, for combining chemical issue and service operations with those of ordnance or engineer sections seldom worked since these services normally used their own resources to the limit. Since, in such combined arrangements, the chemical sections relied heavily on the facilities and services which Ordnance and Engineers provided in the Pacific, the division chemical officer acquired the additional duty of securing and supervising his own service detachments which occasionally worked as ,far forward as regimental supply to issue chemical materials, service flame throwers, and handle mortar shell. The assistant division chemical officer often devoted full time to supply and service which included field improvisation or adaptation of matériel.

Planning, staff, and advisory functions also occupied the chemical officer—at least part of the time. Some of this work was chemical; some was not. The division chemical officer might find himself assigned to liaison, reconnaissance, or observer duties, or he might move out of the staff field into the supervision of combat loading or beach discharge of cargo. Lt. Col. Nelson McKaig, 25th Division chemical officer, an agricultural chemist in civilian life, inspected and supervised divisional food preparation and spent a considerable period setting up a divisional rest camp on Luzon. There were always the additional details that every staff member drew, such as sitting on courts-martial, assisting in command inspections, acting as fire hazards inspector, savings bond officer, and the like. There was an initial impression that the chemical officer had little to do in the absence of gas warfare, so that the division chemical officers may have been assigned a proportionately larger number of staff, command, and operating details than their colleagues. Some division chemical officers, like their colleagues in Europe, welcomed such details because of the opportunity, lacking in the course of ordinary chemical activities, to keep in touch with members of the staff and subordinate units. Some believed, as did Colonel Copthorne, that any service rendered by the CWS increased the prestige and acceptability of the service.

Colonel Copthorne (left) with General Waitt at Colonel Copthorne’s Oro Bay quarters in October 1944

A Second Theater CWS Conference

To return to the theater level, the respect for the service was increasing, and after the middle of 1944, Copthorne again laid plans for coordinating the chemical warfare effort for the Pacific through the best means available to him—a service conference such as the one which had been so successful in 1943. The second theater CWS conference, held from 10--13 October at Oro Bay under the official direction of Maj. Gen. J. L. Frink, Commanding General, USASOS, was considerably more extensive in scope than the previous conference, but the theme was still the tactical employment of chemical warfare, including aerial and land smokes and incendiaries, the chemical mortar, and the flame thrower.66

General Waitt and Lt. Col. Jacob K. Javits attended as representatives of OCCWS. Col. George F. Unmacht, Chief Chemical Officer, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas, and Colonel Greeley represented POA, while Colonel Kellogg and others represented the China-Burma-India theater. The Australian Army, the American corps, divisions, and chemical mortar battalions also sent chemical officer delegates as did USAFFE and USASOS. The Navy sent some of its officers having chemical duties. Colonel Prentiss, now Chemical Officer, Far East Air Forces (a headquarters supervising the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces) attended with other representatives of the air forces. Also present were Dr. W. A. Noyes and several other civilian scientists of the National Defense Research Committee.

The conference made a series of recommendations that were considerably more authoritative than those of the earlier conference. The

Chemical Warfare Officers during the Oro Bay Conference, October 1944

conferees sought a simple table of toxic ammunition requirements based on operational trials under tropical conditions. This, as already indicated, they were soon to get.67 They asked for new aerial toxic munitions, impregnated clothing with increased durability, new gas grenades, and tactical training material reflecting the behavior of chemical agents in the tropics. Other requests were for more manpower for mortar battalions, improved mortars, more spare parts, more and improved field equipment and munitions. But the significance of this conference, as of the previous one, was not so much in what was recommended and requested as it was in the indication of joint effort and the revelation of considerable technical knowledge, much of which had been accumulated through considerable effort and three years of theater experience. General Waitt was particularly impressed by the fact that the conference permitted an exchange of views and experiences among chemical officers of all the Pacific areas, and he noted that the presence of individuals from the United States tended to lessen the view held by some theater officers that they had been neglected by OCCWS.68

The Office of the Chief Chemical Officer—Final Phase

In September 1944 Colonel Copthorne and a part of his section moved to Hollandia and in October the remainder of the section followed from Australia. This office in Hollandia served as the base for setting up the Philippine operation. Copthorne visited Leyte during the campaign in December, and early in February moved his office to that island. These moves placed the USASOS Chemical Section nearer the nerve center of the theater and considerably eased communication with the forward elements. But even better things were to come. At the end of March the office of the chief chemical officer moved with the advanced echelon of USASOS to Luzon. Here command, service, and supply activities were being centered, and, while the chief chemical officer still had no official control or function outside of USASOS, his technical ties and his supervision of theater gas warfare planning at last gave him a very effective tool for controlling the theater CWS.69

General MacArthur was named, after the return to the Philippines, to command the U.S. Army Forces, Pacific (AFPAC) , with jurisdiction over all Pacific theaters. In July 1945 Copthorne achieved what since April 1942 he had considered to be his rightful place—he was named Chief Chemical Officer, AFPAC. He finally had technical control of the CWS not only in the service command but also in the air forces and the ground forces.70 Of the theater chemical officers in World War II only General Shadle as Chief Chemical Officer, AFHQ, enjoyed a comparable official position.

The war in the Pacific ended in September. Most of the officers who had served Copthorne during the long period of the war had already returned to the United States, but he remained as Chief Chemical Officer, AFPAC, until October 1945 when he was succeeded in turn by Col. Sterling E. Whitesides, Jr., and by General Loucks, both of whom served brief tours. Brig. Gen. Egbert F. Bullene served from July 1945 to March 1946 as Chemical Officer, Army Forces, Western Pacific—the administrative, supply, and service command which was organized to succeed USASOS in supporting the invasion of Japan but which was diverted instead to closing out the activities of SWPA or rebuilding them to suit occupation needs. Until his departure Copthorne worked, in a new context, on the same kind of problems which had occupied his attention since February 1942; he requested and assigned personnel, made plans, traced supplies, sought information, established intelligence procedures, and tried to put the CWS component of the occupation forces on a firm technical footing.71

Organizing the Chemical Warfare Service, Hawaiian Department

The Emergency

Lt. Col. George F. Unmacht, Chemical Officer, Hawaiian Department, was having breakfast on the morning of 7 December 1941 when

he saw Japanese planes dropping bombs.72 Within half an hour, Unmacht reported to the department headquarters from his office at Fort Shafter and directed Maj. James M. McMillin, Commanding Officer, Hawaiian Chemical Warfare Depot, Schofield Barracks, to begin issuing service gas masks to departmental troops then equipped with training masks. Lt. James E. Reilly and the men of the 5th Chemical Service Company (Aviation) on duty at Hickam Field also saw the attack and sprang into action. They shot down one of the attacking planes.73

Hawaiian Department authorities at the time feared that other air attacks would be made and that these attacks would include the use of gas. Unmacht’s first responsibility, therefore, was to prepare against aerial gas attack. Leaving M/Sgt. Ralph I. Libby in charge of the Fort Shafter office, Unmacht reported to the departmental advance command post at Aliamanu crater. By noon he had telephoned all CWS staff officers and units on Oahu and had made sure that all were preparing for gas attack. The CWS officer ranking next to Unmacht, Lt. Col. Maurice E. Jennings, Chemical Officer, Hawaiian Air Force, also reported to the advance command post, with an enlisted assistant. Lieutenant Reilly and Lt. Melvin F. Fincke remained at Hickam Field while Lt. Willard H. Blohm took up duty at Wheeler Field. The CWS officers with the air force had the assistance of the chemical aviation company. Major McMillin and 1st Lt. William J. Tanner continued to operate the depot at Schofield Barracks where Capt. Howard S. Leach, Commanding Officer, Company A, 1st Separate Chemical Battalion, was, in addition to his other duties, post chemical officer. The men of Company A, whose second in command was 1st Lt. Rubert D. Chapman, were assigned to guard the depot, haul munitions, and furnish details for the post.

Maj. John H. Becque, Chemical Officer, 25th Infantry Division, was on duty at the Aliamanu crater post with the division staff. Unmacht secured the appointment of 1st Lt. Woodson C. Tucker as Acting Chemical Officer, 24th Infantry Division, which lacked a

chemical section, on the afternoon of 7 December. Unmacht was himself joined that afternoon by 1st Sgt. Roland P. Fournier and one other enlisted man. These 11 officers and approximately 375 enlisted men made up the CWS, Hawaiian Department, until 11 December when 2 Reserve officers reported for duty.

During those first few days the CWS established several supply points in addition to the depot and, with the help of a Civilian Conservation Corps company, completed the issue of service masks. McMillin also put into operation a reconditioned impregnating plant, a chloride of lime production plant, and a toxic land mine and shell-filling plant, all of which had been refurbished in the month before the attack.74 One Reserve officer at once began converting a plant of the Pacific Guano and Fertilizer Company, of which he had been an employee, to the production of bleach.

Civil Defense

Since the CWS had the only available supply of sirens and horns, intended to be used as gas alarms, these were distributed as warnings for air attack pending the acquisition of an air alert system from continental United States. The CWS reconditioned training masks turned in by troops and reissued them to the home guard, civil defense officials, police, firemen, public utilities employees, and other civilians in key positions. At the cabled request of the Hawaiian Department, the Chief CWS gathered 478,000 new and used training masks in the United States and shipped them to Hawaii. When these masks began to arrive early in 1942, Unmacht’s men set civilian crews to work reconditioning the masks and modifying them with sponge rubber padding to fit oriental faces and the faces of children. Civilian masks were issued through first aid stations.

Unmacht and nearly all of his officers, including several newcomers in the theater, together with 2nd Lt. Edouard R. L. Doty, who gave up the post of territorial civil defense director to be commissioned, became involved in extensive civil defense training. Unmacht, promoted to colonel on 12 December 1941 and made territorial coordinator for gas defense in January, gave almost 300 public talks and radio broadcasts. A total of 68,000 civilians attended schools for specialized chemical warfare defense. After the middle of 1942 civil defense

activities began to decrease, but civil defense training continued until mid-1943.75

Organization—Departmental Chemical Office

Meanwhile, in February 1942, Unmacht reorganized his immediate office, which in December had consisted only of Libby’s Administrative Section, to include an Administrative Section under a civilian employee, Miss M. Allegra Clifton, a Training and Civil Defense liaison Section under Lieutenant Doty and a Supply Section under Lieutenant Libby, recently commissioned. In July a further reorganization introduced an executive officer, Capt. James H. Batte, changed Doty’s section to Plans and Training, and put 2nd Lt. Roland P. Fournier, who had been commissioned with 2nd Lt. Ralph I. Libby, in charge of supply. This reorganization in part reflected the addition of responsibilities and individuals to handle them, but it also helped prepare for the strategic and organizational decisions then being made in the Pacific theater. The Hawaiian Department organization, after the organization of the Pacific areas, continued to be the senior Army command for the Central Pacific Area. There was at the time no chemical representative on Admiral Nimitz’ joint and Allied POA staff nor on his Pacific fleet staff. The supreme command and the fleet command were based in the Hawaiian Islands.

Early Training

The July 1942 organization remained in effect during the second half of 1942. In this period emphasis shifted from immediate defensive preparations to preparation for combat in the Central Pacific Area. The area mission up to that time had been indirect support of operations in SOPAC and SWPA, and Hawaii had operated as a staging point for units bound south of the equator. This responsibility had entailed checking supply and training and providing either or both when required for troops outward bound. After the middle of 1942 it became increasingly evident that Hawaii would serve as a base for mounting forces for combat in the Central Pacific under CENPAC or POA command. The CWS, Hawaiian Department, stepped up troop training as its immediate share in the expected CENPAC

Colonel Unmacht watching trainees wash gas from clothing, Hawaii

responsibilities. Unmacht did not establish a theater school as Copthorne had done in SWPA, but he inaugurated a series of gas officer and gas NCO courses for various elements of the department and for combat organizations. While the first informal instruction had been given to a group of air wardens only a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the first course, for 278 UGOs and UGNCOs, was given 17–18 August 1942 in the Fort Shafter gymnasium. Two more advanced courses were given in September and October, and training for the year was brought to a rousing finish during three days in December when the departmental CWS staged a chemical warfare maneuver with 1,295 participants.

Position of the Theater Chemical Officer

At the end of 1942 the Hawaiian Department reorganized from an advance and rear echelon structure in which both echelons were responsible for all functions under the direction of the rear echelon, to a more conventional combat forces, service forces, and air forces pattern and added an echelon for military government since the territory was still under military control. Unmacht remained the department chemical officer with responsibilities in all four fields. His position was unique among chief chemical officers overseas in that he was both staff officer and commander of the chemical warfare troops not assigned to other organizations.76

In actually commanding troops, Unmacht came closer to the manual definition of a chief of service than any other chief chemical officer. But this was not the only way in which Unmacht’s position differed from the positions of the other chief chemical officers. The Hawaiian Department and its successor commands, U.S. Army Forces, Central Pacific Area (USAFICPA) , U.S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas (USAFPOA) , and U.S. Army Forces, Middle Pacific (USAFMIDPAC) , were in fact theater headquarters of the kind envisioned in the War Department organization manuals, and in these headquarters, unlike those in Europe, North Africa, and the Southwest Pacific, a commander, who did not double also as a supreme commander, was resident.77 Unmacht therefore had more opportunity to present his

proposals directly to his commander, Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons, until May 1943 and Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr., thereafter, than did chief chemical officers in other theaters and areas. As Unmacht himself phrased the relationship, “We receive a lot of encouragement and impetus from topside.78 With the theater naval command, which stood in a position roughly comparable to supreme headquarters in other theaters, Unmacht had a good relationship although the Navy took little interest in chemical warfare until combat experience proved the value of the chemical mortar and flame throwers. Navy and Marine Corps officers assigned to chemical duties were usually junior, but commanders frequently consulted Unmacht on chemical supply and training. A reciprocal agreement was worked out whereby the CWS would use the Navy impregnation plant at Pearl Harbor in return for impregnating Navy uniforms. When in the summer of 1944 Navy interest in chemical warfare quickened, Admiral Nimitz, in his capacity as Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, appointed a chemical officer to his own staff—Capt. Tom B. Hill, USN, who worked in close cooperation with Unmacht.79

The Offensive Period in the Central Pacific

Organization of the Theater Chemical Office, 1943–45

On the eve of combat operations in the Central Pacific, Unmacht twice reorganized his office to reflect the increase in activities relating to combat planning and training. In January 1943 Captain Doty, recently promoted, became executive officer and chief of a new Intelligence Division. Reilly, now a captain, became chief of Plans and Training Division and was assigned an officer assistant. Except for redesignation as divisions, administration and supply remained unchanged from the 1942 organization. At the end of June 1943, with an increased workload and greater availability of officers, Unmacht again reorganized his office on a pattern very similar to that prescribed in prewar planning for a theater chemical office. Doty, now a major, became operations and executive officer. Intelligence Division was given the added duty of supervising technical functions. Unmacht

Chart 8: Organization of Chemical Office, Headquarters, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas, 1 April 1945

Source: History, CWS USAFMIDPAC, Annexes Ia and IIIa.

had detailed a few men with technical experience to set up a small laboratory with locally obtained equipment and supplies. At the end of 1943 a laboratory company arrived to assume technical duties. The Plans and Training Division was enlarged and redesignated Operations and Training Division.

The June 1943 reorganization established the form from which the theater chemical section varied but slightly until 1945 At that time an organization consisting of five policy and supervisory divisions and one administration division was approved. (Chart 8) Lt. Col. Edouard R. L. Doty, again promoted, remained as executive officer with duties as assistant chemical officer, supervisor of the theater chemical plan, and liaison officer to field chemical sections and the Navy. Operational planning, base development, personnel and unit assignments, and redevelopment planning were assigned to the Operations Division. Capt. Jerome K. Holmes, in civilian life a chemist, headed the Intelligence and Technical Division which supervised intelligence and laboratory operations and which prepared or supervised the preparation of all technical and intelligence reports. Maj. R. Beverly Caldwell headed the Special Projects Division which was charged with training, inspections, supervision of, and planning for, defense against biological warfare, and technical developments outside the usual laboratory sphere. The Toxic Gas Warfare Division was assigned supervision of gas warfare doctrine development, surveillance of toxic munitions, and liaison with the air forces, which in this theater, as in the rest of the world, had become virtually independent of the local Army command.

Colonel Unmacht delegated operating supply functions and detailed supply planning to the Chemical Office, Central Pacific Base Command, which had been organized under Maj. Roland P. Fournier on 1 July 1944. In his own office, Unmacht retained the Supply and Logistics Division. To this division the CWS chief assigned policy functions relating to operational projects and forecasts for requirements and transportation and analysis functions relating to supply reporting.

Gas Warfare Preparedness

The Chemical Section, Hawaiian Department, like the chemical sections all over the world, had a paramount interest in gas warfare preparedness. Although Unmacht had devoted most of his attention after the Pearl Harbor attack to immediate individual and collective

protection, he also surveyed the department’s ability to retaliate in the case of gas warfare. There were some toxics in the area, but the means of retaliation, like the possibility of being able to reach any enemy force, were indeed slim in 1942. Even had they been ample, however, the nearest target was so far away as to make the immediate possibility of retaliation a remote one. Unmacht set about improving the supply status and at the same time inaugurated both offensive and defensive training. He also arranged to check on both methods of training.

In June and July 1942 the War Department ordered chemical offensive training in the theaters, and the CWS in the Central Pacific complied by providing training for CWS units and chemical sections.80 In August the department CWS initiated a schedule for spot-check inspections of Army units in the Central Pacific to determine their readiness for gas warfare. Of the 522 units inspected by the end of October, 12 percent proved to be thoroughly prepared, 69 percent satisfactorily prepared, and 19 percent partially prepared or without any preparation. Renewed training, especially of UGOs and UGNCOs, and new issues of supplies soon enabled all units to come up to acceptable standards of preparedness. While these preparedness measures were being accomplished, the War Department in December 1942 called for the submission of a gas warfare plan.81

The first Hawaiian Department gas warfare plan, which was coordinated with the local Navy and Marine Corps commands, was dispatched to the War Department on 8 February 1943. The plan simply indicated that in the event of gas warfare maximum use of available weapons and equipment would be made, and no request for special supplies was included. The heart of the plan consisted of a detailed plea for the immediate provision of chemical units and manpower, including a chemical weapons regiment, air and ground service troops, and chemical staff personnel.82 The War Department at first indicated that no troops were available but in July requested restudy and resubmission of the troop request.83 Unmacht replied by reviewing the problems of preparedness. In his opinion these were: (1) lack of

suitable aircraft and trained airmen for toxic spray missions; (2) lack of chemical troops for ground retaliation and for providing artificial smoke protection; (3) inadequate decontamination troops and lack of centralized control over decontamination squads in the Seventh Air Force; and (4) insufficient manpower for service operations. Unmacht asked first priority for service units and a smoke generator battalion since such troops were urgently needed. He assigned a lower priority to, but still cited an urgent need for, nine CWS staff officers in addition to the fifteen authorized, and a chemical mortar battalion.84