Chapter 9: Large Area Smoke Screens in the ETO

The Invasion of Normandy

Almost from the very beginning of their labors Allied planners for the cross-Channel attack contemplated the use of smoke for the beaches in France and the ports that were to be developed there. In 1942 the combined British-American planning organization included an antiaircraft committee which, in turn, had a smoke subcommittee. The logistical computations for the British Haslar generator, the best model then available to the Allies, indicated such large requirements for oil as seriously to limit extensive use of the technique of large area screening. Fortunately, at this time the National Defense Research Committee brought out the M1 mechanical generator, news of which sent a mission hurrying from England to the United States. Colonel Montgomery, the American representative, reported that the new generator was five times as efficient as any existing smoke device. Substitution of the M1 for the Haslar enabled smoke planners to draw up oil requirements which were far more reasonable.1

The development of the new generator prompted attempts by CWS staff officers in England to get a smoke generator company for the theater. War Department inquiries about the requirements for such units got little response from the Eighth Air Force, which came to the conclusion that the advantages of airdrome concealment were equaled or outweighed by the interference of smoke with operations. But SOS authorities in the theater showed interest in smoke as a means of concealing supply installations and later included the ports in

Great Britain through which flowed the build-up of troops and supplies from the United States. Diminishing German air raids reduced theater interest in this type of activity, although during mid-1943 planners envisioned the use of some twenty or twenty-four smoke companies to conceal continental ports once the invasion was under way.2

With the return of General Eisenhower to London from the Mediterranean area in January 1944, planning for the cross-Channel attack began to take final shape. The troop basis for U.S. smoke generator troops now totaled twelve companies, organized into three battalions. Although these were originally listed as SOS units with a primary mission of rear area screening, Colonel MacArthur, CWS representative in the planning group, insisted that one smoke battalion be earmarked for tactical employment with the combat forces.3 And it was to be in this role, rather than through their part in the concealment of rear areas, that smoke units were to make their most effective contribution.

Brigadier G. H. Pennycock, director of chemical warfare for the British 21 Army Group, coordinated Allied smoke screening plans for the initial phase of the invasion. Colonel Coughlan, FUSA chemical officer, was in turn responsible for the operational plans for American forces. One problem which had been troubling First Army, the difficulty of landing the heavy M1 generators on the Normandy beaches, was eliminated almost on the eve of the assault with the arrival of the M2 generator which had a dry weight of only 172 pounds. Smoke troops received the first M2 on 13 May, 7 more on 24 May, 50 on the 28th, and 27 between that date and 3 June.4

Final plans for the use of large area smoke screens during the cross-Channel attack provided for smoke over the ports of England from which the invasion would be mounted and smoke over OMAHA and UTAH beaches in Normandy. In both cases the screens would be used as a means of concealing activity from German aircraft. The companies of the 24th and 25th Smoke Generator Battalions received the English port assignment; the 23rd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. William M. Fiske and including the 79th, Both, 84th, and 161st Smoke Generator Companies, was earmarked for duty at OMAHA Beach, but not

for the first three days of the operation. Chemical decontamination troops, scheduled to go ashore with the initial landings, were at first to use smoke pots and M2 generators to provide any necessary smoke. The 23rd Battalion, with two companies on land and two on offshore trawlers, would assume responsibility for the antiaircraft smoke at OMAHA Beach on D plus 3.5

Once these general plans for smoke operations were completed, the units which were to take part could begin realistic training for their projected tasks. The 30th, 31st, and 33rd Decontamination Companies received such training and were attached to engineer special brigades for the operation. The 79th and 80th Smoke Generator Companies, designated as the sea group of the 23rd Battalion, had to become accustomed to working and living on trawlers. Their offshore employment also presented communications problems which had to be worked out by the battalion. In order to insure the necessary timing and coordination the 23rd was attached to the 49th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade which had control of smoke although subject to the approval of the naval command and the veto of the tactical air command.

The two smoke generator battalions assigned to the English ports naturally began operations before the actual day of the invasion. The 25th, comprising the 85th, 86th, 165th, and 171st Smoke Generator Companies, furnished smoke in the Weymouth-Portland area. During the last part of May the Luftwaffe attacked the area three different times inflicting damage only during raids when the battalion was not ordered to make smoke. The 24th Battalion (81st, 82nd, 87th, and i 67th Smoke Generator Companies) , part of which saw action in the vicinity of Brixham, made smoke on fewer occasions than did the 25th.6

The 33rd Chemical Decontamination Company landed on UTAH Beach on D-day with the multiple mission of decontamination reconnaissance, smoke, and CWS supply.7 Although by that afternoon the unit was prepared to provide smoke on call from VII Corps, the German Air Force failed to appear in strength and the need for smoke never materialized. As a consequence, the 33rd’s main mission became that of supply; the CWS dump maintained by the unit handled over

5,000 tons of CWS Class II and IV supplies during the first three weeks on the beachhead.8

Both the 30th and 31st Decontamination Companies saw action on OMAHA Beach. The former’s 1st Platoon landed at H plus 16 minutes in the midst of the most rugged fighting of the invasion with the missions of decontamination, smoke, and supply. At first, the platoon fought alongside the infantry using small arms and grenades and later, when the beachhead was secured, it aided in evacuating wounded and in clearing mine fields. During the afternoon the portable generators that had been lost in the surf at the time of the landings were retrieved and put into operating condition. As at UTAH, there were no calls for smoke. The 1st Platoon suffered 25 percent casualties on D-day and was cited for outstanding performance of duty.9 At 1300 the 3rd Platoon landed on OMAHA to be joined by the remainder of the 30th Company on D plus T. A 25-man detachment of the 31st Decontamination Company came ashore at H plus 7 hours on 6 June and was reunited with the rest of the company on the next day. In activities which followed the pattern set by the other decontamination companies, the men of the 31st performed a series of secondary duties in the absence of gas warfare and the need for smoke.10

According to plan, the companies of the 23rd Smoke Generator Battalion were to have assumed the smoke mission at OMAHA on D plus 3. The land contingent of the battalion, the 84th and 161st Companies, arrived off the beach on the afternoon of D plus 2 and came ashore that evening. Both companies experienced a great deal of difficulty. Men and equipment became separated; some roads indicated on the map were nonexistent and others were heavily mined or subject to enemy fire. Fortunately, few German planes appeared over the area and smoke was not required.11

The 79th and Both Smoke Generator Companies, with their men and M1 smoke generators aboard thirty of His Majesty’s trawlers, on 9 June arrived off OMAHA Beach, where they served as the offshore element of the 23rd Battalion smoke installation. But they received no requests for smoke. The great storm of 18–21 June wrecked some of

M2 Smoke Generator

the trawlers and others returned to England for repair and refueling, never to return to OMAHA. Some offshore smoke troops did provide screens at Port-en-Bessin where both British and Americans were bringing ashore fuel oil and lubricants. Here, in coordination with the British, the smoke trawlers stood ready to provide screens at twilight and during nocturnal red alerts as long as this important facility seemed threatened.12

During the critical period while the Allies were fighting to secure a firm foothold in Normandy, the landing beaches were virtually free from bombing from the air, and the need for beachhead and port screening did not materialize. Equipped with M1 generators, the companies of one smoke battalion did take positions around Cherbourg and remained on the alert until mid-August, although the need for smoke never arose. Under circumstances such as these, smoke units received

unrelated secondary missions, mostly involving trucking duties. Consequently, when an opportune time did arise for using smoke in close support of tactical operations the companies were busy performing other tasks.

The Generators, Units, and Missions

The most influential factor in the development of the mission of forward area screening in the European theater was the appearance of the M2 mechanical smoke generator. This compact, efficient generator enabled chemical troops to establish effective smoke installations in those areas of the battlefield subject to enemy small arms fire. For example, the M2 could be emplaced on the near bank in an assault river crossing and ferried to the far side as soon as that area was cleared of enemy opposition. The M2 mechanical generator, as already mentioned, weighed only 172 pounds as compared to the ton and a half figure of the Mr. Employing the same principle as its predecessor, the M2 drew its fog oil from an external source, usually a 55-gallon drum, and was capable of producing smoke one minute after it started operation, whereas it took the M1 five minutes. The new model consumed about fifty gallons of fog oil in an hour compared to twice that amount for its predecessor.13

A total of five smoke generator battalions saw action in the European Theater of Operations. The need for some organization for the administration and control of several smoke generator companies became evident in Italy in connection with the complex Naples installation with its several smoke companies. Consequently, three battalion headquarters and headquarters detachments, the 23rd, 24th, and 25th, were organized just before the cross-Channel attack. Later the 22nd Smoke Generator Battalion entered the theater as a supporting unit of Seventh Army, and the 27th Battalion, activated in the zone of interior in July 1944, was placed in support of Ninth Army.

The basic smoke unit was the smoke generator company, I 5 of which saw action in the European theater. A smoke company consisted of a company headquarters, headquarters platoon, and operations platoon. The operations platoon comprised 4 sections, each section having 6 squads. A company equipped with M2s had a total of 50 generators,

2 per operations squad and 2 with company headquarters. Personnel of this smoke company numbered 4 officers and 131 enlisted men.14 The same company with the identical number of troops would have been equipped with only 24 M1 generators, or one per operations squad.

The mission which smoke units had originally considered their most important, the concealment of ports, never materialized in the European Theater of Operations. Experience at the time of the cross-Channel attack indicated that the Luftwaffe was not strong enough to jeopardize these basic supply installations, and this situation did not change throughout the rest of the war. Seventh Army did maintain a rather extensive smoke installation at Marseille during the period September to November 1944, but at no time did the Luftwaffe seriously threaten the port.15

The large area screening mission in the European theater did not undergo the slow transition from rear to forward areas that had marked the fighting in North Africa and Italy. The absence of any great threat by the enemy air force and the development of a mobile generator meant almost from the first that the smoke companies in the ETO would play their most significant role in the forward areas, that is, if they were to play a smoke role at all. Initially, when the German air threat failed to materialize, the smoke units found themselves assigned to a series of secondary missions—transportation, guard, and security details. Early in the fall of 1944 only four of the twelve companies assigned to the theater were available for forward area smoke operations.16 While at times the assignment of smoke companies to other missions was understandable in the absence of tactical situations which called for concealment, in other cases the transfer was not justified. The First Army, for example, could often have used smoke units in forward operations but refused to do so until the time of the Rhine crossings.

But gradually smoke companies began fulfilling forward area missions as the situation warranted. These could be of several kinds. Screens were used to conceal main supply routes. Seventh Army employed smoke units in this manner as much as any other army in the

theater, perhaps because of its previous experience in Italy. Commanders occasionally used smoke haze to cover the advance or withdrawal of troops or to cover a unit attacking a fortified position.17 But there can be no doubt whatever that mechanical smoke generators played their most important role in the theater by concealing American troops as they crossed many of the rivers which had temporarily blocked the way to eventual victory. The first such operation took place early in September at the Moselle River.

The Use of Smoke at River Crossings

General Patton’s Third U.S. Army became operational on i August 1944 and shortly thereafter began its rapid advance across France. By the end of August its forward units, outrunning their supplies of oil and gasoline, ground to a halt east of the Meuse. When the advance resumed early in September, Third Army faced an enemy with a second wind and rather good defensive positions behind the Moselle River.

As long as the Third Army had been rolling forward it doubtless had been more concerned with fuel oil than fog oil. Its rapid advance of August left little room for the tactics of concealment, smoke or otherwise. Consequently, those smoke troops which had been assigned to Third Army had left their generators and turned to transportation duties on the supply line, whose tail extended clear back to the Normandy beaches.

On 6 September Patton’s XX Corps renewed the advance with the 7th Armored Division in the van, its mission the seizure of crossing sites over the Moselle. The 5th Infantry Division, following hard on the heels of the 7th, prepared to force a crossing if the armored attack failed. On 7 September the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Walton Walker, ordered the 5th Division to pass through the 7th Armored and establish a bridgehead on the east bank of the Moselle at Dornot, six miles southeast of the fortress city of Metz. This initial attack across the Moselle proved abortive and two days later, to September, the 5th Division abandoned the precarious bridgehead. On the same

day the 10th Infantry, 5th Division, crossed the Moselle at Arnaville, three miles south of the site of the unsuccessful crossing.18

The Arnaville Crossing

The 84th Smoke Generator Company was hastily recalled from its transportation duties to support the Arnaville crossing. The excellence of German artillery and observation was such as to recommend the possibilities of smoke as a means of concealing the exposed crossing site. At this time the possibilities of the M2 generator were not widely known in Third Army; in fact large area smoke screens in tactical situations had evolved rather recently. This screen at the Arnaville assault and bridging sites was thus to provide new experiences for the various people involved—the infantry, the engineers, and the men of the smoke company.19

At the site of the crossing in the narrow valley of the Moselle, a railroad, a canal, and the river roughly parallel each other in a 500-yard belt. A small stream, the Rupt de Mad, flows through the Arnaville gap, passes under the railroad and canal, and empties into the river. East of the river lay a strip of open land beyond which rose the hills which were occupied by the enemy. North-south roads on each side of the river mark the division between river flats and the beginning of the hills. On clear days the Germans had observation of the Arnaville area from 5 or 6 miles down (north) the river and from 3 or 4 miles up the valley.

Early on 9 September Col. Robert P. Bell, commanding the 10th Infantry, and a party went forward to examine the crossing site. Despite the presence of enemy mines they were able to select suitable approaches and found two footbridges over the canal. They also determined that the river banks were suitable for the launching of assault boats and the erection of adequate bridges once the area was secured.

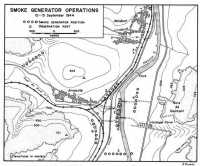

In quest of surprise, the artillery plan stipulated that there would be no preparatory fire preceding the crossing. But smoke from the generators of the 84th Company was expected to conceal the crossing sites as dawn broke on the 10th. Lt. Col. Levin B. Cottingham, chemical officer of the 5th Division, arranged for a meteorological study of the area as an aid to the smoke operations. He scanned the daily weather reports of the Air Forces and the local weather supplements of the division artillery. Arnaville residents verified that the prevailing winds were westerly and of low velocity. After a reconnaissance Cottingham and the commander of the 84th Smoke Generator Company decided on a line of generators behind Hill 303, some 2,300 yards west of the crossing site. (Map 6) . They expected that the prevailing winds would carry the smoke from these positions over the crossing sites and over the flat areas on the far side of the river. Concealed from enemy air and ground operations, engineers could erect and maintain the necessary bridges in support of the operation. Generators were not placed at the crossing site at first because of the unlikelihood of wind change and because of the 84th’s lack of experience under fire. Hill 303 protected the generators from direct enemy artillery and small arms fire, an important consideration for smoke troops who, far from battle hardened, had been driving trucks across a quiet countryside only a few days before. One smoke observation post was established at the OP of the 10th Infantry’s Cannon Company on the crest of Hill 331 , south of Arnaville. Another was located on Hill 303. Cottingham, the smoke control officer at the crossing site, used radio to keep in touch with the observation posts. The 1103rd Engineer Combat Group, commanded by Lt. Col. George E. Walker, charged with the bridge building operation, had tactical control of the screen.

Fog oil for the M2 generators was available at the Third Army depot at Troyes, 180 miles to the rear. Because the organic transportation of a smoke company was inadequate to cope with such lengthy supply lines, the division quartermaster lent the trucks for fetching the fog

Map 6: Smoke Generator Operations

oil to a company supply area four miles to the rear of the forward dump behind Hill 303. Company vehicles hauled the oil drums the rest of the way. In addition to generator smoke, the 84th had a supply of M1 and M4 smoke pots to be used for patching gaps in generator smoke and for supplemental screening.

The 84th moved into its positions during the night of 9–10 September and was ready to produce smoke at dawn. Initially the company set up only twelve generators at Position 1, a number which could be increased or decreased as the situation demanded since the full complement of fifty generators was available.

At 0115 on 10 September troops of the 1st Battalion, 10th Infantry, began loading into the boats on the near bank of the Moselle. They

Smoke screen begins to form on the Moselle River

encountered scattered small arms fire immediately and machine gun and mortar fire as they advanced over the flat open terrain across the river, but the first German artillery fire did not fall until daybreak. By this time the 2nd Battalion had also begun its crossing, assisted by the smoke of the M2 generators which opened up at 0600. Under this concealment the 2nd Battalion completed its crossing, the wounded were evacuated from the far shore, and supplies and ammunition were sent across to the embattled troops. By 0800, after close fighting and heavy casualties, the two battalions had taken two hills. Suddenly at woo the wind shifted, causing the screen to dissipate. Enemy artillery concentrated on the crossing site, now laid bare.

Within an hour Colonel Cottingham and Lt. Frank W. Young, of the 84th Company, moved four generators down to the side of an abandoned railroad embankment (Position 2 on the map). Smoke pots helped conceal the generators as they began to build up a screen,

and by 1200 the crossing site was again covered by smoke. Shortly before noon Brig. Gen. Alan D. Warnock, assistant division commander, and Cottingham looked for the commanding officer of the 84th Smoke Generator Company to tell him to keep the generators running continuously. 1st Lt. George R. Lamb, the company executive officer, was across the river reconnoitering for new emplacements, and Lieutenant Young continued to direct operations along the near bank. The company commander could not be found. At this point, Col. William H. Greene, XX Corps chemical officer, present to inspect the screening operation, joined Cottingham in a search for company personnel. There were many barrels for fog oil at the dump west of Arnaville, but no sign of smoke generator troops. The two CWS officers eventually located a group under control of the 1st sergeant who, not without difficulty, organized details to move generators and fog oil to the crossing site. Without preparation for this type of operation and without company leadership, a number of the smoke troops had to be urged to take up positions down by the river bank. Upon making his appearance in the late afternoon, the company commander was relieved and replaced by Lieutenant Lamb.

The number of generator positions was soon increased in order that an effective screen might be maintained, regardless of the direction of the wind. Position 3 paralleled a short stretch of the Arnaville–Novéant road and was later augmented by a jeep-mounted generator which patrolled the road on the lookout for any gaps in the screen. That night eight generator crews crossed the Moselle with their equipment, dug in their generators, and were ready to start operations at Position 4 at dawn of 11 September. The new smoke plan also included emergency Positions 5 and 6, located south of Arnaville, but these were never needed in the operation.20

At daybreak on 11 September the 84th began smoking operations at Position 3 on the far bank of the river. For several hours activity at the bridgehead was essentially unmolested; enemy shelling had practically ceased. The engineers had hauled several pieces of heavy equipment to the near bank and were about to begin bridge construction. Around 0900 an unidentified engineer, doubtlessly influenced by the absence of opposition and the interference of smoke with bridging

activities, ordered the smoke generators to shut down.21 As soon as the screen dissipated, hell broke loose on the bridge site. German artillery made direct hits on two pieces of heavy engineer equipment and killed or wounded several engineers. Cottingham ordered the screen re-established at once, and the engineers shifted their efforts 300 yards downstream inasmuch as the enemy had pinpointed the original bridge site. To avoid any future interference with smoking activity, the division commander assumed control at the bridge site, to be exercised by his chemical officer.

The engineers rated the value of smoke at Arnaville less highly than did the participating chemical officers. After the war, Colonel Walker expressed the view that enemy fire on the crossing site was limited more by a shortage of ammunition than by American smoke.22 Undoubtedly the enemy did suffer from a limited supply of ammunition and could not make lavish use of shells for missions of harassment and interdiction. But his interest in lucrative targets of opportunity, as evidenced by this experience on 10 and 11 September, was enough to convince the 5th Division that a smoke screen should be maintained.

A 15-hour screen on 12 September was featured by the use of a jeep-mounted generator on the valley road east of the river. About noon engineers completed a treadway bridge at the north site but had to withdraw temporarily because of heavy shelling. The screen continued on 13 September although from time to time enemy fire made the location almost untenable. That day German guns inflicted four casualties and destroyed two generators of the 84th Company and two of its trucks.

Again on the 14th enemy fire forced the engineers to evacuate the bridge site from time to time. Fluctuating winds frequently exposed generator emplacements to direct enemy observation, and the crews hurriedly moved their generators after such an exposure. Smoke pots hid upwind generators, filled gaps in the line, and maintained the screen while crews replaced or repaired generators. Enemy fire killed one man of the smoke company and wounded another. Late on the 14th, engineers completed the bridge at the south site making possible

one-way traffic across the Moselle. That day there was some decrease in enemy fire. On the 15th the 5th Division captured the dominating hill in the area, and German artillery fire further diminished with the advance of the infantry and armor. Thus the bridgehead was secured at a cost of 725 casualties in the 10th Infantry, 13 killed and 100 wounded in the 1103rd Engineer Combat Group, and 2 killed and 7 wounded in the 84th Smoke Generator Company.

Securing the bridgehead did not eliminate the need for smoke, for the Arnaville bridges, which became integral parts of the main supply route for succeeding operations of XX Corps, remained under German observation from Fort Driant and neighboring points in the vicinity of Metz. The 161st Smoke Generator Company, under the command of Capt. Charles D. Underwood, relieved the 84th on 21 September and maintained a screen at Arnaville until the 25th, when XX Corps decided that smoke was no longer necessary. Enemy artillery promptly destroyed the treadway bridge and damaged the ponton structure, stopping all traffic. In response to an engineer request for the resumption of the screen a section of the 84th returned on the 29th and established “a very comforting smoke screen.”23 Enemy guns at Fort Driant, with much of the Moselle Valley in range, continued to fire indiscriminately but failed to damage seriously the heavy ponton bridge.24

The Lessons Learned at Arnaville

The operation at Arnaville demonstrated for the first time in the European theater that smoke generators could give effective support to an opposed river crossing. The experience also served notice that certain improvements were desirable.

Even before the operation began it was evident that a smoke company had enough organic vehicles for transporting fog oil and supplies from company dumps to forward positions, but too few 21/2 -ton trucks to haul oil from the army supply point. The 5th Division solved the problem of fetching oil from the army supply by augmenting the five company trucks with additional vehicles. This matter of limited organic transportation and its effect on resupply remained a constant

problem for smoke generator companies in the fighting in France and Germany.25 The Arnaville experience also pointed out that definite plans had to be made to get generators and fog oil across the river at an early hour. This meant making an initial assignment of boats and rafts to the smoke company for that specific purpose, an assignment which quite possibly would have been made if a section of the 84th Chemical Smoke Generator Company had been a component part of the river crossing assault team.

The operation focused attention on the need for definite control of area screening. Tactical control of the screen by the engineer unit responsible for the bridge appeared logical at first. But the action of the engineers in shutting down the screen in the course of the operation caused all elements to suffer and demonstrated that in certain tactical situations it was highly desirable to clear smoke interference complaints through division headquarters where a decision could best be made. In fact, in subsequent river crossing operations the 5th Division kept control of the screen in the hands of the commanding general until his rear boundary had advanced beyond the bridge. If screening was still necessary, as it was at Arnaville, control reverted to the corps engineer unit charged with maintaining the bridge.

One of the most important lessons learned at the Moselle was the fallacy of depending upon prevailing winds and the necessity of planning for winds from any quarter. On 10 September the prevailing wind remained constant for the first four hours and then turned variable and remained so for several days. Five valleys converged near the vital point, and at times the smoke from generators only several hundred yards apart drifted in opposite directions. Matters were made worse by difficulties in the observation and adjustment of the Arnaville screen. Colonel Cottingham decided to experiment with aerial observation because the hills which rose beyond the far bank were too insecurely held for the establishment of observation posts. Beginning on 14 September he made at least three flights daily: one at 0800, another at 1300 when convection currents began raising havoc with the screen, and the last at 1700 when the air temperature began dropping. Aerial observation revealed defects which could not be noticed from the ground, enabling the observer to anticipate the

effects of wind change. He could note smoke drift from fires in villages and streamers from artillery smoke shell and thus direct generator shifts before the development of any serious gaps. Usually such a trip in a liaison plane, borrowed from the artillery, took about fifteen minutes, but on one trip conditions were so miserable that the necessary adjustments required almost two hours.

Maintenance proved a problem despite the fact that a continuous screen required only a few generators operating simultaneously and that the average generator hours of operation in a day was only forty-four. Experience indicated that extra generators, strategically placed, obviated the need of shifting others when variations and veerings appeared in the wind or when a generator failed to operate. And as a rule three generators a day were replaced because of mechanical failures, burned-out coils for the most part. Consequently, before the end of the operation all forty-eight generators had to be employed. In subsequent operations, assignment to the division of mechanics from a chemical maintenance company brought about improvement in maintenance.

The experience at Arnaville indicated the need for additional smoke generator operators. One man per generator sufficed for rear area screening but the conditions encountered in the front lines made two operators mandatory. The additional man enabled proper reliefs and insured that someone was available for relaying messages to the next position along the smoke line. In case of a casualty, one operator could administer first aid and keep the generator operating. And two men at a position were better for morale.

Troops coming directly from the communications zone into a sector under enemy artillery and small arms fire had to make a rapid mental and emotional adjustment. A few men cracked under the strain, but the majority held up well. Nonetheless, this initial experience demonstrated that a smoke company should have combat training and a period of indoctrination before commitment to an assault crossing operation.26

The 84th Chemical Smoke Generator Company began its Arnaville operations under the additional handicap of inefficient direction before its attachment to the 5th Division. Both personal and organizational

equipment were below standard, with a number of men lacking articles of clothing, rifle belts, helmets, and canteens. Some trailers had been left at the last bivouac before reaching the division. Training in the important areas of communications and map reading was below standard. All these factors, combined with the examples of poor leadership on the part of the company commander once the 84th was committed to action, contributed to make more difficult the company’s introduction to combat. A few shifts in leadership and the example set by officers and men who did respond to demands of the situation helped mold the unit into an efficient team. That the performance of the 84th improved is indicated by the fact that General Walker awarded Bronze Star medals to an officer and four enlisted men and by the statement of the 5th Division Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, after the operation, that “a Smoke Generator Company must be included in making a river crossing.”27

The Third Army Crossing of the Saar River

After the successful campaign against Metz, which fell in late November 1944, XX Corps was ready to begin its advance into Germany.28 By 1 December the corps had reached the west bank of the Saar River and was preparing to establish bridgeheads on the east bank, in the face of the West Wall defenses of the enemy. Before reaching the West Wall, one of the most strongly fortified areas in Europe, Third Army would have to cross the open river flats, a tactical situation which could well call for a considerable use of smoke.29

The XX Corps plan for the Saar operation called for assault crossings in the Dillingen-Saarlautern sector by the 90th and 95th Divisions while the 10th Armored Division feinted a crossing near Hilbringen. The 161st Smoke Generator Company, attached to the Loth Armored Division, was ordered to screen the vicinity of the partially destroyed Merzig bridge, which, for all the enemy could know, might already have been repaired for a crossing operation.30 Beginning on 4 December the 84th Smoke Generator Company screened both flanks of the 95th

Division as it crossed the river in the vicinity of Saarlautern. The division also called for generator smoke on the captured bridge at Saarlautern and over the construction activities at Lisdorf.31

The most extended screening missions of the Saar crossing were those in the Dillingen-Pachten area, several miles north of Saarlautern, in support of the 90th Division. These operations involved the 84th and 161st Smoke Generator Companies, and elements of the 81st Chemical Mortar Battalion. The infantry began crossing before dawn on 6 December, and smoke operations began at daybreak. Entrenched behind the West Wall on the far side of the Saar River, the Germans could observe all feasible crossing sites and the road nets leading to them. Artillery and mortar fire hit throughout the river area during the whole period of the operation, and in the early phase enemy small arms fire covered the crossing sites. The smoke troops at the ferry site were still within range of small arms fire as late as 10 December.32 So heavy was hostile fire that for the sixteen days of the assault, engineers of the 90th Division were unable to erect a vehicular bridge and operated ferry traffic only with great difficulty. The variable winds which prevailed for the first six days tore gaps in the screen, so that mortar and artillery smoke shells had to be used as supplements.33

On 19 December the 90th Division began to withdraw from the east bank as part of Third Army regroupment to oppose the German breakthrough in the Ardennes. This maneuver involved the movement of nine battalions of infantry and more than 200 vehicles through a restricted crossing site which was still within range of enemy artillery and which was serviced by only a single ferry, one foot-bridge, and a few assault boats. The 84th and 161st Smoke Generator Companies screened the withdrawal successfully and were among the last troops to return to the near bank.

Screens for the crossing and withdrawal at the Saar resulted in expenditures of 151,000 gallons of fog oil and 8,500 HC smoke pots. The smoke line near Dillingen had extended for more than 2,000 yards

and covered troops and vehicles moving up to, as well as across, the Saar River and had effectively concealed traffic along roads to Saarlautern and other points. Enemy sources reported that U.S. “artificial fog” along the Saar interfered with German observation and diminished the effectiveness of his artillery fire.34

Smoke Operations at the Roer

As early as December 1944 Ninth Army was aware of the desirability of smoke support for its contemplated Roer River crossing, and it was at this time that it had secured the services of the 74th and 83rd Smoke Generator Companies.35 These units, commanded respectively by Capt. George B. Warren, Jr. ,and Capt. Augustus H. Shaw, Jr., were attached to XIII and XIX Corps. Both companies underwent training for front-line operations since preparations in the zone of interior had been directed toward the rear area mission. The German counteroffensive in the Ardennes delayed the scheduled Roer crossing. During this interval Ninth Army held smoke demonstrations in the rear area of the 29th Division to acquaint infantry and engineer commanders with the capabilities and limitations of the mechanical generator.36

With the defeat of the Germans in the Ardennes, the Allies again focused their attention on the Rhine. But the immediate objective was to cross the Roer, and Ninth Army, flanked on the right by the First Army, was to launch an assault crossing of that river and advance northeast to join forces with the First Canadian Army, which was to drive southward along the Rhine and clear its west bank. The Ninth Army sector was a broad, flat region cut by the Roer and other streams which flow generally in a northward direction. Entrenched on the far bank the enemy had excellent observation of the western approaches to the river. He also was able to flood the Ninth Army sector by the controlled release of water from the dams up the valley. As a consequence, the 10 February target date for the crossing was postponed until 23 February when Ninth Army assaulted on a 2-corps front—the

XIII on the left near Linnich and the XIX on the right in the vicinity of Jülich.

The 74th Smoke Generator Company supported the crossing of the 84th Division in the XIII Corps sector. On the night of 22–23 February the 74th used smoke pots from 2000 to 0315 while engineer and infantry troops concentrated on the near bank; the assault began at the latter hour under concealment of smoke which drifted toward the far side. At first, the smoke company used only pots for fear that the noise and placement of the mechanical generators would disclose the position and intention of the infantry, separated from the enemy only by the Roer River. But after the crossing the 74th used both mechanical generators and pots in smoking the bridge sites. Each day it stood by prepared to smoke on call. Each night from 1700 to 0700 hours it screened several bridges in the vicinity of Linnich from enemy aircraft. The 74th continued these missions until 3 March, first in support of the 102nd Division and then while attached to the 19th Antiaircraft Artillery Group. The screening at Linnich was generally successful despite understandable complaints about the irritating effect of HC smoke and some interference with traffic and friendly artillery observation. The smoke materially aided bridging operations and, according to infantrymen of the 1st Battalion, 333rd Infantry, effectively concealed the flash from their 60-mm. mortars.37

While the Linnich assault was in progress, XIX Corps crossed the Roer upstream on a 2-division front, the 29th Division on the left at Jülich and the 30th Division on the right in the Pier–Schophoven area. Corps assigned the 83rd Smoke Generator Company (less one section) to the 29th Division which in turn attached it to the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion. The smoke plan for the operation stipulated that Company A, 92nd Chemical Mortar Battalion, use white phosphorus shells to supplement the generator smoke in the event of unfavorable winds. Screening began at 0350, twenty minutes after the initial assault, along a 2-mile smoke line opposite Jülich. Under cover of this smoke engineers worked with little hindrance by the enemy. A request by the division engineer that smoke be continued after daybreak to keep observed enemy fire away from the bridge sites was overruled by corps because

of interference with the observation of corps artillery.38 Shortly after the screen lifted hostile artillery fire destroyed one of the bridges under construction. It was the opinion of the division engineer that smoke might well have saved the bridge, and the XIX Corps staff was convinced that better smoke coordination was needed in future operations.39

Several miles upstream the 30th Division planned to cross the Roer River in the vicinity of Schophoven and Pier and drive north to the Cologne–Jülich highway along which the enemy might launch a counterattack against the Jülich bridgehead of the 29th Division. It expected that the crossing would be difficult because of the swollen channels, the many pools of water from the recent floods, the spongy soil, and the lack of cover. In fact, during November Ninth Army had considered a crossing in that vicinity impracticable.40

The infantry began the crossing by boat at 0330 23 February after a 45-minute artillery preparation reported to have been one of the heaviest concentrations of fire experienced in the European theater.41 Along the 8,000-yard division front 246 artillery pieces, 35 mortars of the 92nd Chemical Mortar Battalion, and 36 guns of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion participated in the preparation. The initial assault force encountered only light opposition. The 119th Infantry crossed at the north site, opposite Schophoven, while one battalion of the 120th Infantry crossed to the south, opposite Pier. A mile of low, boggy ground and water separated the two sites.

The smoke plan called for screens over both these sites, as well as over the area between them, during the twelve daylight hours of 23 February. If conditions should prevent the effective screening of both bridge sites, the northern bridge was to have priority. The division commander maintained control of the use of smoke, while the division chemical officer supervised its operation. The critical observation posts of the enemy were in the towns on the far bank and along the low ridge of hills to the northeast. At first, only one section (twelve

generators and crews) of the 83rd Smoke Generator Company was available, supplemented by a detachment of seventeen infantrymen, several mechanics from the 57th Chemical Maintenance Company, and two men from the division chemical section. For several nights preceding the jump-off, smoke troops went forward and dug foxholes, established supply dumps, and prepared generator emplacements.42

The smoke troops moved into position at 0245 on 23 February. The din of the heavy artillery preparation drowned the noise of movement and darkness hid the exact location of the bridging area. Smoking began at 0630. The generators provided good concealment at the northern site but unexpected winds at the south site tore gaps in the screen. The smoke line was extended to the southeast. In mid-morning engineers ceased construction on the south bridge becau.se of accurate artillery fire, which was probably adjusted when gaps appeared in the screen. After one battalion crossed on boats and Alligators, the 120th Infantry transferred its effort to the northern site where the 11 9th, under effective smoke concealment, was crossing without much difficulty.

Smoke concealed the northern crossing throughout the day. While engineers worked on a treadway bridge, infantrymen crossed a foot bridge and overran enemy positions on the east bank of the river. Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs, commanding the 30th Division, ordered the screen continued during the coming night and the next day. The request for the night screen was prompted by the Luftwaffe which had been rather active during the previous two nights and which was using a number of jet-propelled planes. Another section of the smoke company came from the 29th Division at Jülich to help maintain the screen.

During the night of 23-24 February the 30th Division extended the bridgehead to the northeast, capturing the towns of Hambach and Niederzier and eliminating enemy observation of bridge sites from the east. The northern bridge was opened to passage of armor at midnight. By dawn the wind was from the north and smoke troops established pot positions on the far bank along the western edge of the Krauthausen–Selgersdorf road. Troops and armor advancing over this route were exposed to observed fire from the woods beyond Hambach, so the smoke line was moved eastward across the road, 100 yards into the

fields. For the same reason, other smoke positions were established north of the Selgersdorf–Daubenrath road. Chemical troops captured four prisoners while setting up these final positions in an area infested with enemy mines.

Division headquarters ordered smoke over both the northern and the southern bridges for the night of 24-25 February. But the supply of smoke pots was exhausted by about 1530 hours and the M2 generators were in need of repair after a long period of continuous operation. Moreover, the crews were fatigued from thirty-three hours of continuous duty. Consequently, the decision to use smoke that night was canceled. By morning the 30th Division had driven the enemy beyond range of observation, and smoke was no longer necessary.

Large area screening activities along the Roer contributed to the success of 30th Division operations in several ways. Smoke over the northern area enabled the engineers to start construction of a vehicular bridge five hours earlier than had been anticipated. The enemy never had an opportunity to deliver observed fire, a circumstance that enabled the 29 5th Engineer Combat Battalion to maintain uninterrupted bridging operations. In fact, there was not a single engineer casualty from enemy fire at the northern bridge. As a result of this building feat, the first armor moved across the Roer River at H plus 21, fifteen hours ahead of schedule.43 Another benefit of the screen was the concealment of infantry and armor units moving up to, across, and beyond the river, particularly those units in the vicinity of Selgersdorf. In two instances the infantry called for extension of the smoke coverage near the front line. Captured prisoners stated that, while they believed the Roer offensive was imminent, the darkness at the time of the initial attack and the subsequent screening confused the Germans as to the exact location of the American effort. The plan for the Roer crossing had called for only twelve hours of smoke, but during operations screening continued without cessation for thirty-three hours. This extension was indicative of the effectiveness of the screen and the value which General Hobbs placed upon smoke.44

First Army crossed the Roer on the right of Ninth Army. The VII Corps, on the left, crossed near Duren and advanced northeastward

to protect the right flank of Ninth Army. The 104th and 8th Divisions spearheaded the corps attack. The other two corps of First Army, the III in the center and the V on the right, initially remained on the defensive but were prepared to advance on or after D plus 2.45

Forward area screening developed slowly in the First Army. There was none during 1944, with the exception of an August operation at Mayenne, France, which shielded a bridge against enemy air bombardment. But the smoke tests that Col. Kenneth A. Cunin, army chemical officer, ran at Liege in late 1944 impressed at least one high ranking commander, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, commanding VII Corps. Collins and his engineer officer, Col. Mason Young, both saw great possibilities in using the mechanical smoke generator in assault river crossings and the general attempted to get some to support his corps’ assault of the Roer. Circumstances prevented the use of smoke generators in the Roer crossing. Col. Jack A. Barnes, VII Corps chemical officer, had too little time to collect the equipment or to assemble suitable trained troops. In fact, the only trained smoke units were the 79th and 80th Smoke Generator Companies and these, the First Army commander decided, could not be released from the secondary duties to which they had been assigned. Any screening operation would therefore have to depend upon the smoke pot and the white phosphorus shells of the chemical mortar. The plan for using smoke in the sector of the 104th Division was abandoned when its artillery commander objected to possible interference with observation.46

The 8th Division planned to cross south of Duren with the 28th Infantry on the right at Lendersdorf and the 13th Infantry on the left. After the crossing, the 28th Infantry was to protect the corps right flank until III Corps entered the fight. The 13th Infantry did not plan to employ smoke at the crossing, but the 28th Infantry made provisions for using HC pots to conceal the initial assault and the subsequent bridge construction. S/Sgt. Robert J. Cesari of the 80th Smoke Generator Company gave training in smoke tactics to the infantrymen of the reserve battalion who were to man the pots. On the eve of the attack Capt. Kirk J. Ruger, commanding the 80th, was attached to the division as smoke observer and adviser. He was especially concerned with screens planned for the two bridges which were

to be built by the 294th Engineer Combat Battalion in the vicinity of Lendersdorf.47

The 28th Infantry jumped off near Lendersdorf early on 23 February. The smoke from HC pots, the haze from shell fire, and the morning mist concealed the crossing site until shortly after i 000. During this phase the two bridge sites (Nos. 9 and 10) received sporadic and unobserved small arms and mortar fire. But at 1000 the west wind ceased, the screen lifted, and accurate enemy artillery fire began to come in on bridge site 1o. Captain Ruger’s suggestion to have Company D, 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion, fire WP shells against enemy positions on the right flank across the river was ruled out for fear that friendly troops might be in the impact area. In the absence of wind the use of smoke pots would have been ineffective.

There was also trouble at the bridge site No. 9, visited by Ruger in midafternoon. Engineers had suspended all activity on this treadway bridge because of the direct fire from an enemy self-propelled gun on the opposite bank, accompanied by small arms fire. The division’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. Charles D. W. Canham, insisted that the bridge be started promptly, regardless of cost, and asked Ruger to recommend the use of smoke so as to conceal renewed attempts at construction. A light northwesterly wind had set in by this time and Ruger suggested a smoke installation through Lendersdorf augmented by floating pots which, because of the curve in the stream, would establish a semicircular smoke line around the crossing site. But in the meantime enemy fire had increased so much that all work was postponed at this site and concentrated on bridge No. Io. Company D, 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion, was then ordered to establish a smoke screen on the far bank where the Roer River intersected the III–VII Corps boundary. Sergeant Cesari had already set up a smoke line around bridge No. 10 and his smoke detail of ten men from the 28th Infantry had placed the pots. The heavy fire, however, had scattered the detail and Cesari had to light the pots himself. The smoke drew additional fire, but the engineers were able to resume work on the footbridge. Chemical troops maintained HC and WP screens

from 1630 until darkness. That night the Luftwaffe bombed and strafed the bridge site while enemy artillery continued to fire into the area.48 Next morning the commanding officer, 28th Infantry, on the advice of Captain Ruger, ordered Company D, 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion, to continue the screen on the high ground to the southeast. German artillery fire on the bridge sites lessened but did not cease. Obviously the enemy knew the location of the engineers. Later in the day jet fighters strafed the bridge sites, by now without smoke probably because the pot supply was exhausted. That night enemy planes dropped flares and continued to bomb and strafe the area, damaging the bridge at site No. 9 and some engineer equipment. The air effort which continued until noon of the 25th had as many as twenty planes over the area at one time.49

Smoke was not effectively used to support the Roer crossing of the 28th Infantry. VII Corps correctly estimated during the planning stage that the enemy could seriously oppose any crossing in the 28th Infantry sector for at least three days. The two bridge sites remained within mortar range of an enemy-held area on the right flank which was not engaged by American forces until 26 February, or three days after the 28th Infantry attack. Projected smoke could have been employed here profitably, as Captain Ruger suggested, if suitable coordination had existed. Under the prevailing northwest wind mechanical generators could have concealed the bridges effectively without seriously interfering with infantry or artillery operations. For the most part, the smoke would have drifted into enemy-held territory opposite III Corps. The area to be covered was too large to be effectively hidden by smoke pots. The 4.2-inch chemical mortars placed smoke on observation points to the southeast, but only after the enemy had ranged in on the bridges. And none of these screens could conceal the bridge sites from an attack. German artillery fire and bombing delayed the construction of the two bridges, so that they were not finished until more than forty-eight hours after the fighting began, and then at a cost of 23 wounded engineers.50 Smoke, if properly employed, undoubtedly would have reduced enemy observation and probably

would have lessened the time required for construction and the number of engineer casualties suffered in the process.51

The Use of Smoke at the Rhine River Crossings

When the Allies terminated the Rhineland Campaign on 21 March 1945 they found themselves, with one exception, poised along the west bank of the Rhine, ready for the final assault. The exception was the Remagen bridgehead in the First U.S. Army sector, where a combination of fortuitous circumstances and aggressive action by the leaders and men of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, secured on 7 March the only Rhine River bridge taken intact by the Allies. During the fourth week in March the Ninth, Third, and Seventh U.S. Armies successfully assaulted the Rhine. In each case, units of the four armies used smoke generator companies to conceal either their actual assault crossing or the crossing sites during the period of build-up.

The unexpected capture of the Ludendorff railroad bridge on 7 March and the rapid expansion of the bridgehead radically changed the First Army plans for the Rhine crossings. Under the new plan VII Corps would expand the Remagen bridgehead northward to the Sieg River. As army forces cleared the far bank of the Rhine, its engineers, under the concealment of smoke, would build bridges first at Rolandseck, then Königswinter, then Bonn. Because of success at Remagen, conventional assault crossings in the VII Corps sector were unnecessary. Bridge sites might be subject to artillery and mortar fire but not to any serious amount of small arms fire.52

The day after the capture of the Ludendorff bridge the engineers at the bridge site requested a smoke generator unit. When First Army replied that none was immediately available the engineers at Remagen had to depend upon whatever pots they could hurriedly gather. Finally, on 10 March, First Army relieved its smoke units from other duties and gave them five days to be ready for screening missions, whereupon the 79th and Both Smoke Generator Companies retrieved their smoke

equipment from its six months’ storage. On 15 March the two units received march orders and, early next morning, the 79th departed for Remagen and the 80th Company headed for VII Corps in the vicinity of Rolandseck.53

During the early phase of the Remagen operation the Germans held the high ground on the east bank with observation over the bridges and the approaches thereto. Artillery fire continually impeded, and at times halted, the movement of First Army troops through the area.54 To provide for the increased traffic, III Corps engineers built two bridges which the enemy attempted to destroy by artillery and mortar fire, by bombing, and even by demolitions. Mechanical smoke generators would have expedited the erection of the bridges, according to an engineer officer, but by 16 March, when the 79th Smoke Generator Company (Capt. Morris W. Kane) arrived, the urgent need for smoke had ended.55

The first VII Corps units passed through the Remagen bridgehead on 15 March and within two days they had cleared the area opposite Rolandseck. Engineers started bridging the Rhine at Rolandseck on the night of 16-17 March and at dawn the 80th Smoke Generator Company began concealing the bridge site. The next afternoon most of the company departed for another bridge site at Königswinter although several squads remained at Rolandseck until 23 March. Meanwhile, the 79th Company had moved from Remagen to Königswinter and set up generators on the east bank of the Rhine. Smoke operations at this site, featured by the use of boat-mounted generators, also ended on 23 March.56

An extensive First Army screening operation took place along the Rhine at the southern outskirts of Bonn. Under technical control of the 23rd Smoke Generator Battalion, smoke was started at os o 1, 21 March, and continued without interruption for sixty-one hours. After

23 March the smoke troops remained alerted for five days, ready to operate against bombers, but the threat never was to materialize.

By 21 March the Third Army had reduced the Saar-Palatinate triangle, except for the mopping-up phase, and three of its corps had reached the Rhine. General Patton insisted that the enemy be given no chance to recover from the defeat in the Palatinate. Third Army planned to secure crossings over the Rhine River promptly and then advance to the northeast. The VIII Corps, on the left, would attack between Koblenz and Bingen and XII Corps was to cross the Rhine between Bingen and Worms. XX Corps, on the right flank, would continue mopping-up activities and then cross through the bridgehead of either VIII or XII Corps.57

The XII Corps attached the 84th and 161st Smoke Generator Companies to the 5th and 90th Divisions, respectively, for the assault crossings. The 162nd Smoke Generator Company was to support the 87th and 89th Divisions of VIII Corps operating north of Bingen. The 81st Company was trucking for XX Corps but would be available for smoke operations on short notice. With four smoke generator units on hand, the Third Army could not only use smoke at the crossings but could also lay deceptive screens. There was some thought of placing a large dummy screen at Mainz because the enemy apparently believed that an initial crossing attempt would be made at that point.58

Previous Third Army smoke generator operations had emphasized concealment from artillery observation, as enemy aircraft had been relatively inactive. During February, for example, only thirty-two enemy planes were reported over the entire Third Army zone, and of these only two made attacks, both of them strafing.59 But as the Army approached the Rhine, enemy air activity increased. On 20 March large numbers of German aircraft, including the new jet-propelled Me.262, attempted to bomb bridges and strafe troops. On that date the Luftwaffe made a total of 314 sorties in the XII Corps zone alone.60 This increased enemy air activity, even though temporary, was a distinct threat to the Rhine bridging operations and suggested that the crossing sites be screened against air as well as against artillery observation.

The 5th Division made the first crossing of the Rhine for the Third Army on the night of 22–23 March in the Oppenheim-Nierstein area. Two regiments had already crossed when, at dawn, the 84th Smoke Generator Company provided smoke from both sides of the river. Each day thereafter the 84th established a heavy screen at dawn and dusk, the periods when the engineer bridges were most vulnerable from the air. During the night the 84th maintained a haze which could be readily thickened in case of attack. In daylight, fighter planes and AA guns fought off enemy aircraft. A number of the generator positions along the near bank were atop a hill and the smoke, although blanketing the bridges from the air, was not dense enough on the ground to hinder traffic.61 Additional generators were mounted on Dukws, but were not needed.

The importance of screening the Oppenheim-Nierstein area can be judged by the traffic which crossed the Rhine at that point. Five divisions, with supplies and supporting troops, passed over its three bridges between 23 and 27 March. And between 24 and 31 March, 60,000 vehicles crossed in support of the XII Corps assault. The smoke screen which initially concealed this area was approximately two and a half miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide. None of the bridges sustained damage during the area’s four major air attacks.62

For several days after the crossing at Oppenheim-Nierstein the increased activity of enemy aircraft necessitated the continuance of smoke generator operations. On 24 March, 138 enemy planes attacked bridges, installations, and troop concentrations in the XII Corps sector. During the next day the sorties increased to 231. Heavy enemy aircraft losses and the overrunning of many fighter fields by the Third Army’s advance soon reduced the threat posed by the Luftwaffe, and on 26 March only three German planes appeared over the XII Corps.63 As a matter of precaution, smoke generator operations continued at Oppenheim–Nierstein until 31 March.

While the 5th Division was crossing at Oppenheim, the 90th Division was cleaning up Mainz and threatening to cross the Rhine either there or to the north. In support of this feint the 161st Smoke Generator

Company, on 23 March, made smoke at several points between Bingen and Mainz. On the same day the 90th Division swung south, crossed the Rhine at Nierstein, and assumed control of the southern portion of the 5th Division bridgehead, an action which obviated the need for smoking the Rhine between Mainz and Bingen. Two days later a detachment of the 161st moved into Nierstein and extended the smoke line which the 84th Smoke Generator Company had already established there.64 By 26 March all major units of XII Corps were well beyond the Rhine and were attacking points along the Main River in the vicinity of Frankfurt. The 161st Smoke Generator Company then moved forward and screened the bridges.

The divisions of VIII Corps crossed the Rhine between Bingen and Koblenz. The precise sites were Rhens and Boppard in the 87th Division sector, and Oberwesel, St. Goar, and Wellmich in the sector of the 89th Division. The 162nd Smoke Generator Company divided its generators and crews between the two divisions. The smoke plan at Boppard called for screens for the assault crossing of the 345th Infantry and for the ponton bridge building activities of the 1102nd Engineer Combat Group. The 162nd made the first smoke at Boppard on 25 March from 0620 to 0635, just before the 345th Infantry attack. The generators smoked again at 0650 and remained in operation until late that night. With a favorable wind, the cloud traveled across the river and filled the valley. That night the wind shifted from south-southeast to northeast and the 162nd, in order to conceal the bridge operations, moved its generators across the river. The smoke crews continued the screen throughout the next day, 26 March, under a steady rain of enemy artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire. The operation ended 26 March.65

Meanwhile, on the night of 24 March one section of the 162nd set up a smoke screen in support of a deceptive move made by the 353rd Infantry, 89th Division. The ruse was successful in that the enemy directed a large amount of artillery and small arms fire into the screened, but unoccupied area. The actual assault came early on 26 March; smoke operations ceased after half an hour because of

interference with forward observation. The crews of the 162nd remained in position, until 28 March, in case the enemy shelled the bridge site.66

The 162nd Smoke Generator Company also provided smoke for the assault of the 354th Infantry, 89th Division, opposite Wellmich, on the morning of 26 March from 0600 to 0630. Enemy artillery and small arms fire at the time of the successful crossing was heavy but unobserved.67 At the same time, the company set up five generator positions near Oberwesel for the crossing of the 355th Infantry, 89th Division, and smoked from 0550 to 1700 hours, 26 March, while two battalions crossed the river. The screen not only covered the crossing site but also denied observation to enemy forces located at Kaub, upstream on the far side of the Rhine.68 The Luftwaffe was not as active against VIII Corps bridge sites as it was against those of XII Corps although artillery and small arms fire were heavier. But despite heavy initial resistance the 87th and 89th Divisions advanced rapidly to the east, and by 28 March the Rhine mission of 162nd Smoke Generator Company was over.

The 8rst Smoke Generator Company supported XX Corps, which did not enter the picture until 27 March, when the 80th Division attacked across the Rhine and Main just southeast of Mainz and cleared the area around Kastel and at the junction of the two rivers. As soon as the infantry cleared the far bank, the smoke company screened the bridging operations, with half of the unit on either side of the river. Under smoke, the Third Army engineers built a 1,896-foot steel tread-way bridge, probably the longest floating tactical bridge of the war.69 The 81st continued to operate at Mainz until the evening of 1 April.70

Early in March 1945 the 3rd and 45th Divisions of Seventh Army began preparations for the Rhine crossings. These divisions and various supporting organizations converged on Lunéville, France, to make use of the several lakes in the area for specialized training. Among the units supporting the 3rd Division was the 540th Engineer Combat

Group with the 69th Smoke Generator Company attached. Supporting troops of the 45th Division included the 40th Engineer Combat Group and the 78th Smoke Generator Company. These attachments were to carry through the entire period of the Rhine crossings so that trained and coordinated teams would be ready to support the assault.71

Divisions of XV Corps led the Seventh Army assault across the Rhine. The initial crossings were to be made between Gernsheim and Ludwigshaven by the 45th Division on the left and the 3rd Division on the right, the first crossing north, the second south of the city of Worms.72 All five companies of the 22nd Smoke Generator Battalion received screening assignments for the assault crossing, the first time all had been committed to the same forward area operation. Battalion headquarters was relieved from all other duties on the eve of the crossing and placed under direct control of the Seventh Army chemical officer. Previously, the battalion commander had occasionally participated in the Rhine crossing preparations, but generally his headquarters had performed other duties. As it turned out, the most important battalion function at the Rhine was logistical, the coordination of the supply of fog oil to the various smoke companies.73

Early on 26 March, for a brief period just before as well as during the assault crossings, the 163rd and 168th Smoke Generator Companies drew German attention from the actual sites by maintaining feint screens in the sectors of the 71st and 36th Divisions. Meanwhile, the 45th and 3rd Divisions crossed the river in the Worms areas on 2-regiment fronts. Enemy opposition to the 45th Division petered out quickly and no smoke was needed although the 78th was in position. This was not the case with the 3rd Division in its Ludwigshaven–Worms sector. Here initial resistance to the early morning attack was weak, but by 04430, an hour and a half after the assault began, hostile artillery pinned down all troops in the area, and engineer operations at the upstream crossing site stopped. One engineer company suffered fifty-four casualties. Although German artillery fire hit three smoke company vehicles, the unit lost no men to enemy action. The intense

artillery fire did prevent a platoon trying to take over smoke pots in assault boats from reaching the west bank. Fortunately, the southwest winds eliminated the need for pots across the river. At 0700 the 1st Platoon, from positions in the near bank generated a fog oil screen between the enemy on Friesenheimer Island and the crossing site, a maneuver which effectively blocked German observation of troop and boat movement. At 1030 the 1st Platoon with six generators crossed the river in Dukws only to be pinned down for several hours by enemy fire with four generators still on the craft. The two that were gotten off maintained a haze between Sandhoffen and the crossing site which “greatly reduced the accuracy of enemy fire on the engineer operations.74

The two assault battalions in the 30th Infantry sector completed their crossings by 0305, and the 2nd Platoon, 69th Smoke Generator Company, set up a smoke pot line on the far bank two and a half hours later. Just before daylight smoke began to pour from the pots across the river and from mechanical generators on the near shore. The variant winds caused smoke to be needed on all sides. The smoke haze denied observation to German troops on an island in the river which held out until several hours after daylight. Because the infantrymen took over the storm boats which had been allotted to the smoke troops, their own being destroyed by enemy artillery, the supply of smoke pots and the crossing of the generators were both delayed. By 0930 the smoke troops had four generators in operation across the river and half an hour later a wind shift to the southwest minimized the problem of smoke supply to the far bank.75

During the day the commanding general, 3rd Division, ordered that smoke be made over both sites on a 24-hour basis. After 27 March the Luftwaffe, not hostile artillery, became the greater threat. The 2nd Platoon, 69th Smoke Generator Company, continued to smoke the ponton and treadway bridges, which the engineers built near Worms, until 31 March. The 1st Platoon concealed the heavy ferry site with smoke until 30 March then moved to Ludwigshaven and screened the

bridge which connected that city with Mannheim. The 78th Smoke Generator Company moved to Mannheim on 1 April and set up a smoke line around the bridge which was erected over the Neckar River, but smoke was not needed. CWS troops maintained both installations until 5 April.76

On the eve of the Rhine crossing the Ninth U.S. Army was still with the British 21 Army Group, an attachment which had taken place at the time of the German counteroffensive. On its left was the British Second Army with a boundary near Wesel; on its right, just upstream from Dusseldorf, was the First U.S. Army, holding the left sector of General Bradley’s 12th Army Group. Ninth Army designated its XVI Corps to make an assault crossing in the sector between Orsoy and Buderich. Initially, XIII and XIX Corps were to hold the west bank of the Rhine opposite the Ruhr, later to follow through the XVI Corps bridgehead. Chemical units available to XVI Corps for screening operations included the 27th Smoke Generator Battalion and the 74th and 83rd Smoke Generator Companies. The 89th and 93rd Chemical Mortar Battalions also were to contribute to the smoke mission.

Ninth Army screening operations along the Rhine River were divided into two phases, those before the crossing and those in connection with the assault. The purpose of smoke in the first phase was to conceal movement on the west bank and confuse the enemy as to Army intentions and crossing preparations. For eight days before the assault, smoke intermittently covered sixty-eight miles of the front north of Dusseldorf held jointly by British and American troops. The plan provided for “smoking” days and “nonsmoking” days, according to a schedule which was coordinated with air reconnaissance activities. In the Ninth Army sector the 74th and 83rd Smoke Generator Companies and provisional personnel performed these preliminary missions with smoke pots, the mechanical generators being conserved for the main crossing effort. Enemy reaction to the employment of smoke during the first phase was varied. Prisoners stated that at first the Germans expected the assault after each smoke operation, but after continued feints they became confused as to Allied intentions. In some localities the Germans were extremely sensitive to smoke and

replied promptly with inconsequential fire. A German radio broadcast boasted that an American attempt to cross the Rhine under smoke had been repulsed. On the whole, however, the enemy showed little reaction. A more important result of the smoke was expediting Allied troop and supply movements, particularly in the British and Canadian sectors where many dumps were located in exposed areas.77

The XVI Corps plans for the Rhine operation called for a 2-division crossing in the vicinity of Wallach, Mehrum, and Milchplatz. Naval craft were available for the initial assault and the engineers were ready to bridge the Rhine, a task which they anticipated would be no more difficult than that of bridging the Roer River under flooded conditions. After the crossing, the Ninth Army was to drive eastward, contain the enemy in the Ruhr pocket to the south, and maintain contact with the British Second Army on the left.

Smoke plans for the crossings provided for concealing the bridge sites for forty-eight continuous hours, if necessary. Under no circumstances was smoke to interfere with the airdrop of the First Allied Airborne Army at Wesel, scheduled to begin at moo hours on the first day. Maj. Robert H. Kennedy, commanding the 27th Smoke Generator Battalion, supervised the activities of the two smoke generator companies and operated the corps smoke control center. The artillery agreed to furnish liaison planes for observation of the screen. With the additional assistance from the artillery meteorological sections, the smoke control center would be advised of screening conditions anywhere in the army area at any particular moment. Any complaints about the interference of smoke with operations were to be referred to the smoke control center, with the matter reconciled by the G-3. Elements of the 89th Chemical Mortar Battalion would screen the right flank of the corps sector, opposite Orsoy, along the Rhein–Herne Canal.78 The 83rd Smoke Generator Company and two sections of the

74th would conceal the crossing sites of the 30th Division near Wallach and Mehrum, while the other two sections of the 74th Smoke Generator Company were to smoke at Milchplatz for the 79th Division crossing. Generator positions, as far as practicable, were to take advantage of the protection afforded by the dike on the west bank. Where necessary, the smoke troops were to use pots over the low land between the dike and the river. The first smoke was to appear at dawn on 24 March.79

The Ninth Army assault crossing of the Rhine River began on the night of 23-24 March. After heavy preparatory fire the initial waves of the 30th and 79th Divisions jumped off at 0200 and 0300 hours, respectively. Resistance was not serious and by daybreak thirteen battalions of infantry had crossed and secured four bridgeheads, several thousand yards deep. Within twenty-four hours the front lines had advanced approximately six miles beyond the Rhine.80

At dawn, smoke from the generators along the dike line concealed the ferrying operations of the assault boats from enemy ground and air observation. Fear that the haze might drift over the Wesel airdrop area and impede paratroop operation proved groundless. In midmorning the wind shifted from west to east, through south, and the smoke troops moved pots and generators across the river and screened from the far bank. Smoke continued on the first day until after dark. On 2S and 26 March smoke covered the bridges in the 30th Division sector during the daylight hours. But at Milchplatz, in the sector of the 79th Division, the generators remained idle until enemy guns had ranged in on the bridge site.81 From 27 to 31 March the smoke troops operated only during the periods from 0500 to 0800 and from 1700 to woo hours, when the bridges were most vulnerable to air attack. Enemy aircraft strafed the generator lines during the nights of 24, 25, and 26 March, and artillery fire lasted through 24 and 25 March, but the smoke troops suffered only two casualties. The only damage to smoke equipment occurred during the movement of Alligators and tank destroyers during the hours of darkness of the initial assault. Smoke was not required after 31 March.82

Planned as a 48-hour operation, smoke actually was used at the Rhine crossings for a period of eight days. During the first two days of the crossing the frequent shifts of wind direction made screening difficult, especially at Milchplatz, although the concealment of crossing activities was generally effective.83

Summary