Chapter 10: Large Area Smoke Screens in the Pacific

Large area smoke operations in the Pacific contrasted sharply with those in Italy, France, and Germany. By concealing rear area installations and forward area operations, CWS smoke generators in Europe had performed a vital service. The few smoke units in the Pacific, on the other hand, were inactivated while still in the training stage. The role of smoke in the Pacific was restricted mainly by geography and by the decision which gave the war against Germany priority over the Japanese conflict. Geography was an especially limiting factor. It dictated that a good deal of the fighting in the Pacific would be done by the naval arm. The most effective use of smoke in the Pacific was in the form of anchorage screens maintained by the Navy to conceal the vulnerable vessels involved in the numerous island hopping campaigns so typical of the war against Japan.

Early Attempts To Introduce Area Screening in SWPA

In the early phases of the war in the Southwest Pacific Area commanders who considered area screening as a means of concealing airfields from enemy air attack ran up against several serious problems.1 These included not only a lack of a suitable means for static screening and a shortage of smoke materials but also a scarcity in shipping, both within the immediate area and from the United States to SWPA. If smoke was to be used the means and material would have to be devised locally.

When an industrial survey disclosed that large quantities of the FS smoke material could be produced in Australia, Colonel Copthorne, Chief Chemical Officer, USASOS SWPA, assigned the 42nd Chemical

Laboratory, then in Brisbane, the mission of developing both a large and a small smoke generator which could employ this chemical smoke. Tests in the summer of 1942 revealed deficiencies in the large model which was dropped entirely later in the year after word came that the newly developed mechanical smoke generator would soon be made available to the theater. The 42nd Laboratory Company went on to develop a small smoke generator which was to see limited use in the theater.

In January 1943 the Commanding General, USASOS SWPA, approved a project for concealing an advanced base or port with smoke and requisitioned two smoke generator companies from the United States to carry out the project. The harbor at Port Moresby, New Guinea, was chosen as the site for the first smoke installation, although military authorities realized that another port might be more critical by the time the smoke units arrived. After an on-the-spot survey of Port Moresby, Colonel Copthorne recommended that some generators be mounted on barges or power boats to insure adequate smoke coverage.2

In May 1943 the theater asked the Chief, CWS, to comment on its tentative plans for a smoke installation at Milne Bay, which, as had been foreseen, was now a more exposed harbor than Port Moresby. These plans, which included the employment of generators both on land and on water to conceal shipping activity in the harbor, suffered from a lack of power boats on which to mount the generators which were to be waterborne. The theater requested the War Department to send several craft suitable for this purpose along with the two smoke companies requisitioned earlier in the year.3

In July SWPA pressed the War Department for the immediate shipment of the two smoke companies and speculated on the reduced requirement for smoke pots if three smoke generator battalions were assigned.4 People in the Southwest Pacific Area were also concerned with the possibility that the two companies, which by September had not yet arrived, would be equipped with the 3,000-pound M1 generator, instead of the new lightweight M2.5 Meanwhile, in response to the

Smoke generator in a DUKW on Milne Bay

theater’s interest in large area screening, General Porter in August 1943, sent Maj. Roy E. Halverson, a trained smoke officer, to the Southwest Pacific Area.6 Major Halverson made surveys at Milne Bay, Oro Bay, and Goodenough Island, concluding that the establishment of smoke installations at any of these locations would be a difficult proposition. He confirmed Colonel Copthorne’s view that the lack of road nets at advanced ports would entail heavy dependence upon water transportation. Not only were appropriate craft in short supply but the M1 smoke generator was rather bulky for this type of employment. In fact, the successful screening of port facilities in the Southwest Pacific seemed to require an amphibious smoke unit, a type that so far had not been foreseen by planners in Washington.7

By mid-1943 the Japanese were raiding Goodenough Island regularly and Milne Bay, New Guinea, occasionally. The theater proceeded with its plans to station the two smoke generator units temporarily at Milne Bay where they could be adapted to island employment and

trained for more difficult operations at a more advanced port.8 But the 10th and 170th Smoke Generator Companies landed at Sydney, instead of Milne Bay. Shortage of shipping and the higher priority of other units precluded the immediate transshipment of these units to Milne Bay, and the two companies remained in Australia for almost two full months after their arrival in October 1943. As a result, smoke company training at Milne Bay did not begin until January 1944 and then only under the greatest difficulties. The base commander could not permit a considerable amount of smoke over the area because his installation was operating under pressure, day and night. Of even greater importance was the lack of craft on which to mount the smoke generators. Boats could be borrowed for short periods, but none could be assigned to the smoke troops. General Porter, Chief, CWS, arranged to ship four J boats which, shortly after arrival, were severely damaged by a storm.

By April 1944 it was evident that smoke training operations would have to be shifted to a less active port. Chosen was Base E at Lae, on the northeastern coast of New Guinea, where ships anchored while awaiting a call to a more exposed port9 and, consequently, where practice screens would not interfere with normal port operations. Another advantage was the short distance to the air base at Nadzab, up the Markham River from Lae. The air base was an ideal place to test screening of air installations and a source of aircraft from which to observe the practice screens. The companies moved to their new location in mid-July and immediately experienced greater success with their training program. The road net facilitated land training, and boats were available for working out problems in the bay. In mid-August Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment, 26th Smoke Generator Battalion, under the command of Maj. Allen H. Williams, arrived from the United States and took charge of the two smoke companies.10

A Question of Mission

In June 1944 the commanding general, USASOS, recommended to General MacArthur the employment of smoke generator units during the early stages of an amphibious operation for screening supply dumps

as well as for concealing ships engaged in unloading.11 He proposed that the 10th and 170th Smoke Generator Companies be equipped with suitable craft and trained to use the new lightweight M2 generators, then en route to the theater. General MacArthur agreed that the smoke troops could be profitably employed in future operations and suggested the transfer of the two companies to the Sixth Army for amphibious training under an engineer special brigade.12

Col. Carl L. Marriott, Sixth Army chemical officer, opposed this suggestion, indicating that the USASOS recommendation was merely an admission that it had been unable to interest the 14th Antiaircraft Command in the value of the smoke units. Reasons given by Colonel Marriott for this lack of interest included inappropriate equipment, the fact that the Esso generators were too unwieldy, and the reputation of the two smoke companies at Milne Bay for “smashing up” their equipment.13 CWS officers at Milne Bay refuted this last argument, attributing damaged equipment to the work of the elements, not to careless maintenance.14 In arguing against the assignment of the two smoke companies to Sixth Army, Marriott also brought up the matter of control. In an assault landing these units initially would be controlled by the naval task force commander. On the other hand, smoke operations to conceal ships just off the beaches would have to be coordinated by a second agency, the one charged with the control of antiaircraft artillery and fighter aircraft. Marriott recommended that USAFFE should clarify the question of control and assign the smoke units to the 14th Antiaircraft Command, a troop unit not under Sixth Army.15

Early in September 1944, and before any decision was reached on the control of the smoke units, a group of Sixth Army officers witnessed a smoke demonstration at Lae which featured the recently arrived M2 mechanical generator, smaller and more economical and efficient than its predecessor. Without exception, the officers were most enthusiastic about the capabilities of the new mechanical

generator and requested that every effort be made to obtain smoke companies for Sixth Army to be used on beachheads and airstrips.16

It seems that the final decision regarding the assignment of the CWS smoke companies pleased no one. The two companies were not assigned to the Sixth Army, nor to an antiaircraft artillery command, as recommended by Colonel Marriott. In October the commander of the USA Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area, unaccountably ordered that the 70th and 170th Chemical Smoke Generator Companies be inactivated and that the personnel so released be used to activate two quartermaster truck companies.17 This decision marked the end of efforts to prepare the two units for combat and prompted Navy officers to question the wisdom of eliminating the smoke units in face of the increasing need for smoke in beach operations.18

The officers and men of the headquarters of the recently arrived smoke generator battalion received assignments with the chemical warfare school at Oro Bay. There they taught and prepared studies for the employment of smoke in future operations. The new lightweight M2 generators, which arrived in the theater in August, were turned over to the Navy along with the supply of fog oil and most of the floating smoke pots.19

Renewed Interest in Smoke

The smoke companies had hardly been inactivated before ground commanders in the area began inquiring about their availability. The XI Corps, for example, became interested in smoke after learning of the successful employment of the mechanical generator at Anzio.20 Chemical officers at the CWS conference at Oro Bay wanted to know how long it would take to train combat troops in the use of the lightweight M2 generator for forward area operations. At this time, October 1944, about 100 of these generators were in or en route to the theater.21 A month later Lt. Col. David D. Hulsey, Chemical Officer,

6th Infantry Division, asked Col. Harold Riegelman, Chemical Officer, I Corps, whether any smoke troops were available to screen river crossings. The answer was: in the absence of smoke units ground troops would continue to rely on mortar smoke shell and smoke pots for that type of mission.22

Meanwhile, various units of the Sixth Army resorted to limited area screening with whatever smoke weapons or equipment was available. The 2nd Engineer Special Brigade used the small FS generator developed by the 42nd Chemical Laboratory Company to conceal LCMs unloading at Colasion Point from rifle and machine gun fire.23 But the M1 and M4 smoke pots proved to be the mainstays for area screening. Smoke from these munitions successfully concealed the Tacloban airstrip on Leyte from Japanese bombers during the full moon period of November 1944.24 In the Zamboanga operation in western Mindanao Colonel Arthur, chemical officer of the 41st Infantry Division, organized a smoke pot line along one side of an airstrip then under construction after Japanese artillery had damaged heavy engineer equipment.25 During the Luzon Campaign, the Sixth Army used smoke pots far more extensively than previously to conceal road and bridge construction from enemy observers.26 The increased use of smoke in the Sixth Army resulted from the stepped-up activity of the Japanese air force; the shift to larger land masses for maneuvering, along with a decrease in the amount of jungle fighting; the availability of smoke weapons and munitions; recent emphasis by commanders and chemical officers on the importance of smoke in combat; and the fact that the use of smoke had proved beneficial in saving lives and equipment.

Another possible mission for large area screening, the concealment of airfields, was beginning to take shape in the Pacific Ocean Areas.

In the summer of 1944 United States forces captured Guam, Tinian, and Saipan in the Marianas group and immediately began constructing airfields from which to stage bombing attacks against Japan. These bases became operational in the fall and early winter of 1944, and B-29’s of the XXI Bomber Command began their assault on the Japanese homeland.27 In turn, these airfields in the Marianas were subjected to enemy air raids, infrequent and largely ineffective, but nonetheless “an expensive nuisance, which, if unchecked, could have become more costly.”28

Even as the Advanced Echelon, XXI Bomber Command, was staging at Hickam Field, Oahu, its chemical officer, Maj. John Barrows suggested the use of smoke generators to conceal the B-29’s when they reached the Marianas. The Commander in Chief, POA, turned down this request on the ground that the available shipping space was needed for more vital supplies.29 General Waitt, Assistant Chief CWS for Field Operations, brought the subject up again during his November 1944 visit to Saipan. Noting the vulnerability of the B-29’s to Japanese attack—several of the planes had already been destroyed by enemy air action—Waitt insisted that the use of smoke could conceal the expensive aircraft without interfering with the antiaircraft screen. Later on in Hawaii, he urged Admiral Nimitz and General Richardson to adopt this plan.30 Despite the merits of the case, and the fact that eleven B-29’s had been destroyed and forty-three others damaged, the plan for screening the Marianas airfields against enemy attack never got off the ground. The interests of the strong antiaircraft artillery defenses were considered paramount.31 In any event, enemy air attacks ceased early in 1945 when Iwo Jima with its air bases fell to U.S. Marine forces, thus eliminating the trouble at its source.

The question of employing smoke troops at airfields arose again in

connection with Operation ICEBERG, the campaign against the Ryukyus chain. Because of the proximity of the islands to the Japanese homeland, American planners correctly anticipated that their assault would provoke a great amount of enemy air action. The Navy made excellent use of smoke at Hagushi Beach, Okinawa, during the earlier phases of the operation, but withdrew its smoke personnel in the post-amphibious phase when Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, commanding Tenth Army, assumed leadership ashore of the land forces of the operation. Originally, the Army planned to use smoke generators to conceal airfields and beaches during Phases II and III of ICEBERG, during the occupation of Ie Shima and the establishment of control over northern Okinawa, and during the seizure of additional islands in. the Nansei Shoto. The 28th Smoke Generator Battalion, comprised of the 67th, 68th, and 71st Smoke Generator Companies, received the Okinawa assignment. Unfortunately, the 71st Smoke Generator Company was not available in time for operations on Ie Shima. Although the Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment, 28th Chemical Smoke Generator Battalion, and elements of the 67th and 68th Smoke Generator Companies arrived at Okinawa on 12 June, Phase III of the operation was canceled. The remainder of the two companies arrived on Okinawa early in July, but Japanese air activity had diminished considerably, and the need for smoke no longer existed.32

Although the planning for the invasion of Kyushu, the southernmost island of the homeland of the enemy, had not been completed when Japan surrendered, it appeared certain that smoke generator troops would have seen extensive use had the invasion been mounted. Colonel Copthorne, now Chemical Officer, Army Forces, Pacific, arranged with representatives of the operations officer of his headquarters and with the commander of Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet, for the use of five chemical smoke generator companies during the early stages of OLYMPIC, as the operation was dubbed. Earmarked for the eastern shore of Kyushu were the three companies of the 28th Smoke Generator Battalion. The two quartermaster truck companies which had formerly been the 10th and 170th Smoke Generator Companies were to be reconverted to smoke units and earmarked for operations on the western shore of Kyushu. During the initial stage of the operation

and under control of the Navy, the companies were to screen ship concentrations, harbors, and beaches. Once the invasion forces had successfully landed, smoke troops would revert to Army control. How these units were to be assigned in support of tactical operations on Kyushu was still a matter of conjecture when the war came to an end. Upon orders of AFPAC, Eighth Army prepared a study on the use of smoke troops in land operations on the island. It recommended in July 1945 that twelve M2 mechanical generators be issued to the chemical service platoon assigned to each combat division and that two smoke generator battalions, each with four companies, be redeployed from Europe and assigned, one each, to the two invading armies.33

Colonel Copthorne approved the idea of giving mechanical smoke generators to chemical service platoons, calling attention to the growing tendency of combat troops to demand larger and larger smoke screens and arguing that the use of fog oil by the service platoon would reduce the tonnage of mortar and artillery smoke ammunition. The chemical officer of Sixth Army, Colonel Burns, opposed the plan. He felt that the chemical service platoons had neither the men nor the transportation for the conduct of screening operations. Moreover, he considered impractical any attempt to substitute a fog oil screen for a projected smoke screen because they served “different tactical purposes.”34 There could be no doubt that chemical service platoons in the combat area were fully occupied in the supply and maintenance of chemical supplies and were already short of transportation facilities. But Burns’s statement concerning tactical screening ran counter to the experience of U.S. forces in Europe who frequently used fog oil to save mortar and artillery ammunition. V—J Day found still unanswered this question of how the combat divisions in the Pacific could best be supported by smoke generator personnel.

The Navy’s Use of Smoke

Naval operations in Pacific waters, particularly in the last two years of the war, were accompanied by an extensive use of smoke. Although the Navy had its own arsenal of smoke munitions, including HC pots and the Besler mechanical generator, its use of CWS equipment was not uncommon. CWS personnel also contributed to the fulfillment of the Navy’s smoke mission.

The question of concealing Pearl Harbor with smoke was one of long standing, and the Army, before World War II, had discouraged at least one Navy suggestion for screening that most important installation.35 It was natural that the matter would assume a much greater significance after 7 December 1941. Although early in 1942 a special smoke board set up by Admiral Nimitz recommended against screening the Pearl Harbor area, the M1 mechanical smoke generator was scarcely off the assembly line before the Navy obtained fifteen of the items for use in the Hawaiian Islands.36 Knowing little or nothing about the generators, Navy officials at Pearl Harbor requested Colonel Unmacht to service and demonstrate the machines. By March 1943 he had gotten possession of all fifteen generators, trained men from the 91st Chemical Mortar Company in their operation, started a program for training Navy personnel, and had demonstrated the generators along the Honolulu waterfront and at Pearl Harbor.37

The Navy’s interest in area screening prompted General Richardson, commanding the Hawaiian Department, to take a renewed interest in smoke equipment. Earlier, he had attempted unsuccessfully to secure fifty generators without taking any smoke troops. The Chief, Chemical Warfare Service, had strongly opposed this suggestion, arguing that the efficient operation of the generators required trained men available on a 24-hour basis.38 Richardson was still unwilling to substitute smoke generator troops for others on his troop basis for Hawaii. Again the War Department replied that the Hawaiian Department could not have the equipment without the troops, although as a compromise it was willing to send a cadre of smoke specialists, provided that General

Richardson activate a smoke unit within the theater.39 During the negotiations, Colonel Unmacht argued that the need for smoke was far greater in Hawaii than along the west coast of the United States, where smoke units were then stationed. He believed that the situation justified 500 smoke troops despite the presence at Honolulu and Pearl Harbor of 10,000 men assigned to fighter, antiaircraft, and barrage balloon units. Unmacht’s arguments that smoke troops, man for man, contributed more to antiaircraft defense than those of any other service were not persuasive enough to cause the Hawaiian Department to substitute smoke troops for other types.40

The Navy made one more attempt to secure a smoke installation for Pearl Harbor, suggesting that its facilities be screened with existing equipment—15 mechanical generators and 1,100 obsolete stationary generators. General Richardson referred the proposal to Colonel Unmacht who pointed out that, in comparison with mechanical generators, the stationary models consumed too much oil and required too many men to operate. Besides, he argued, there was not enough equipment on hand to screen Pearl Harbor effectively. Unmacht used this opportunity to try again to convince the Hawaiian Department to ask for smoke generator companies.41 The diminishing need for smoke at the islands served to nullify this last attempt to get a full-scale smoke installation at Pearl Harbor.

After mid-1943 smoke screening activities in the Pacific Ocean Areas were confined to the combat zones. The first of the island campaigns in the Central Pacific Area was the V Amphibious Corps’ assault on the Gilberts. Plans for Tarawa, the objective of the 2nd Marine Division, called for curtains of smoke laid by carrier planes, as well as the use of Army M1 and M4 smoke pots loaded on landing craft, to conceal mine sweeper activity and the assault waves of marines as they rendezvoused for the final run. The actual operation saw limited use of smoke. The aircraft screens were deemed unnecessary, although the pots on the landing craft did obscure the assault craft from enemy observation. Smoke activity during the difficult days after the assault proved to be of more importance. Six landing craft, stationed at various positions to the windward, used smoke pots

to shield ships anchored in the lagoon during enemy night air attacks, at times aided by LSTs equipped with smoke pots.42

Area screening of anchorages became accepted procedure for operations in the Marshall Islands, the next step up the island ladder. The Navy rehearsed the planned smoke procedures during January 1944 and put them into practice during the invasions of Kwajalein, Roi-Namur, and Eniwetok. In brief, small craft burned M1 and M4 HC pots, furnished by the CWS depot in Hawaii, while the cargo and personnel ships employed the Navy’s Besler mechanical smoke generators for the first time. The glare from the pots and their fire hazard emphasized the need for a small lightweight generator which could be mounted on small craft for this type of operation.43

The Marianas campaign in the summer of 1944 saw further Navy successes with anchorage screening. Between 15 June (D-day) and 7 July, the Saipan anchorage had a total of 19 hours of smoke entailing 57,000 gallons of fog oil and 11,400 smoke pots. The commander of the Joint Expeditionary Force called it “the greatest factor in the extremely effective defense of the transport area against air attack. During the repeated attacks 100 bombs were dropped in the vicinity of the transport area, but were obviously dropped blindly. ...”44

The Navy set up a most complete smoke installation at Guam. Emplaced mechanical generators lined the landlocked harbor while small craft with mounted generators patrolled the entrance. Resembling those established during 1943–44 at Bizerte, Naples, and Anzio in the Mediterranean theater, this was one of the few smoke installations in the Pacific which depended upon land-based mechanical generators as the primary means of screening. Ironically, enemy air forces never tested the smoke defenses.45

On 20 October 1944 Sixth Army launched its operations against the Philippine Islands with the assault on Leyte. The Japanese response was immediate, including the commitment of a substantial part of Japan’s air reserves.46 During the first stage of the operation U.S. carrier-based planes twice laid screens over the invasion beaches of X and XXIV Corps. Floating smoke pots enabled two beached LSTs to resume unloading after an interruption caused by enemy mortar fire. For the first four days the Japanese concentrated their air activity during the hours of daylight. Antiaircraft defenses during this period consisted for the most part of U.S. carrier-based fighters which prevented any serious damage to the ships or the targets onshore. This procedure restricted smoke to the twilight periods and night alerts. In the next four days, when enemy planes averaged 175 sorties, the Navy used smoke extensively during day as well as twilight and night attacks. After 27 October the smoke again was restricted to twilight, moonlight, and nocturnal alerts. This return to former tactics, which were continued in operations at Lingayen Gulf and Okinawa, came about for several reasons: the ineffectiveness of the daytime screens except under ideal low-speed wind conditions, the fear that the smoke generators would not hold up under extended use, a shortage of fog oil, the establishment of an airstrip at nearby Tacloban, and the fact that daytime smoke precluded observation by the antiaircraft batteries at the same time that it allowed enemy aircraft glimpses of the masts of the assembled ships.47

Antiaircraft defenses at Leyte Gulf were largely successful. Few, if any, ships received hits while hidden by smoke although several destroyers outside the screen suffered damage. This accomplishment was the greater because Leyte marked the first appearance in force of the Japanese kamikaze planes. By preventing Japanese pilots from sighting individual targets, smoke did much to reduce the effectiveness of these suicide missions. After the operation the commander of Southern Attack Force commented that “area smoke, properly employed, is

invaluable for protecting a transport area from enemy air attack at night or at twilight.”48

The landings at Lingayen Gulf in Luzon saw some use of smoke pots to conceal the beaches from direct observation by enemy artillery until American counterbattery fire could silence the opposition.49 Once the beachhead was secured the Navy regularly screened the anchorage at dawn and dusk for a daily total of about two hours. The Leyte experience led to improvements in the screens at Lingayen Gulf. Smoke boats arranged in lines at distances of 500, 1,000, and 2,000 yards windward from the ships resulted in a more uniform screen than had been the case at Leyte. Ships under smoke at Lingayen suffered no damage from the dawn and dusk air raids, despite the frequent 15- to 20-knot sea breeze. Denied observation of the anchorage, the Japanese planes made several hits on destroyers and escorts patrolling outside the concealed area. The supply situation at Lingayen Gulf was much better than that at Leyte which had seen the near depletion of fog oil and smoke pots.50

The naval commander at Lingayen Gulf strongly recommended that LCVP (landing craft, vehicle and personnel) smoke boats should be fitted with the CWS lightweight smoke generator as soon as possible. The smoke cloud produced by this mechanical generator not only was more persistent, but it was without the toxicity of HC smoke. Frequently, both at Leyte and at Lingayen, men aboard ships became ill when ventilating systems drew in the HC-laden air. And there was always the storage problem and fire hazard presented by smoke pots.51

In preparing for the campaigns of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the Navy in the Pacific received technical assistance from members of the Amphibious Smoke Committee. Capt. N. F. Chamberlain, CWS, and three naval officers of the committee reported to the Commander, Amphibious Forces, U.S. Pacific Fleet, on 5 November 1944 for

temporary duty as smoke specialists. In Hawaii they lectured on the experimental work done at the Amphibious Training Base, Fort Pierce, Fla.,52 trained air and naval crews and infantry troops in the employment of smoke munitions and equipment, prepared training directives, and assisted in writing smoke plans for scheduled operations. The committee appeared in Hawaii at a rather opportune moment, for interest in smoke screening had reached a high point with the news of how kamikaze pilots had been baffled at Leyte.53

On 22 December 1944 the committee, before many high-ranking combat commanders in the POA, including ten admirals and a number of Marine and Army generals, successfully staged in Hawaii a large-scale demonstration on the use of smoke in landings. Vice Adm. Richmond K. Turner, Commander, Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet, was among those impressed by the capabilities of smoke. As a result of the demonstration members of the smoke committee were requested to participate in subsequent landing operations as smoke advisers.54

At Iwo Jima the Navy used a limited quantity of smoke during the initial assault, including screens laid by carrier-based planes as the first wave approached the beach.55 Later, screens concealed ships in the anchorage from kamikaze planes during sixteen different night raids. No vessel under the screen suffered damage, although five enemy bombs straddled the USS Auburn.56 Beach and shore party personnel had been specially trained for the employment of portable smoke generators on the island, but none actually made the landing.57 The satisfactory performance of waterborne generators negated the need for landing the palletized generators, an operation which would have been imperiled by the heavy sea and currents.

The most extensive and prolonged area screening operation in the Pacific took place at Okinawa. Anticipating that the Japanese air forces would desperately oppose any landing so close to the homeland, framers of the task force smoke plan specifically provided for night coverage of the anchorage and further directed the commanders of

attack forces and groups to draw up detailed plans for other uses of smoke. The latter provision resulted in limited use of smoke in connection with underwater demolition team activities, landing feints, the assault on Ie Shima, and mine-sweeping activities. But the anchorage screens were another matter. Okinawa saw the kamikaze campaign reach a crescendo,58 and in an effort to minimize the terrible destruction caused by these riders of the “heavenly wind” the Navy expended more fog oil and smoke pots at the Hagushi Beach anchorage than in any other single operation of World War II.59

In addition to the customary means of smoking from small craft and ships the Navy on L-day plus i took ashore forty-five mechanical generators and divided them between the north and south sectors of Hagushi Beach. Next day these generators went into operation. The southern line, commanded by Captain Chamberlain of the Amphibious Smoke Committee, had twenty-five emplacements; the northern line had about fifteen. Limited training of the generator operators did not prevent the shore contingent from maintaining an adequate screen over the anchorage.60

A word about the operation of the screen. The senior officer present afloat ordered smoke when unidentified planes, as shown by the radar screen, seemed likely to attack. All ships under the screen withheld antiaircraft fire, because smoke was an ample safeguard against the few planes which penetrated the outside fighter defense and because AA fire might disclose the location of the ships.61 During the night of L-day (1 April) smoke covered the anchorage for a total of 6 hours and 3 2 minutes. Smoke concealed the anchorage and beaches during 40 of the 46 nights between L-day and 16 May, with the average screen lasting slightly more than 2 hours. From 17 May until 21 June, the day the island was secured, the Navy resorted to smoke practically

every night for an average of one hour and 27 minutes, although one night of unusual Japanese air activity resulted in an 8-hour screen. Estimated expenditures of smoke materials for the Okinawa operation were 2,475,000 gallons of fog oil, 3 5,000 land smoke pots, and 47,500 floating smoke pots, or floats as they were known to the Navy.62

Comments on smoke operations at Okinawa were of special importance because of their influence on planning for the invasion of Japan. Captain Chamberlain reported that the initial skepticism among ship captains as to the value of smoke over the anchorage quickly changed “to an almost frantic clamor for smoke cover when it was found that only those ships outside the smoke screen were being hit by suicide planes.”63

Admiral Turner made a number of recommendations for future smoke operations, which, for the most part, concerned logistics. Again, planning for the Okinawa operation had not provided adequate quantities of fog oil and pots, either in the forward area or in reserve. Consequently, supplies were almost exhausted several times during an operation. He advocated equipping all merchant ships with fog oil generators and expanding the maintenance facilities for smoke equipment. Both measures would further increase the requirements for fog oil to 8,000 barrels (approximately 400,000 gallons), an amount he considered a minimum for planning an operation the size of the one at Okinawa. This weekly replenishment figure was double that requested (although not always supplied) for Okinawa. Turner also emphasized that smoke personnel should be recognized as specialists and urged that CWS smoke generators units be provided for onshore assistance.64 It seems that if the Pacific war had continued, smoke would have played an important role on sea as well as on land.

Screens for Airborne Operations

Airborne operations in the Pacific differed considerably from those in the war against Germany. The difference was largely a matter of

size; the geography of the Pacific area, as noted earlier, dictated that most ground operations there would be on a smaller scale than those on the land mass of Europe. The forces in the Pacific received more modest allotments of men and matériel than did those in Europe. Perhaps the very small size of the Pacific airborne operations made them more suitable for support by air-land smoke screens. In any event, in contrast with experience in Europe, half of the six airborne operations in the war against Japan had the benefit of smoke.65

The first of the air-screened paratroop landings, indeed the first airborne operation in the Pacific, took place in eastern New Guinea at the airstrip near Nadzab, a village some twenty-five miles up the Markham River from the coastal town of Lae.66 The landing at the Nadzab strip, an overgrown facility about a half a mile north of the river, took place on the morning of 5 September 1943, the day after an Australian-American amphibious task force went ashore near Lae. The successful completion of these missions would lead to control of New Guinea’s Huon Peninsula and increased control of the straits between New Guinea and New Britain. More immediately, the seizure of Nadzab would prevent Japanese reinforcement from the Wewak area and would enable C-47’s to fly in the Australian 7th Division for a move down the Markham River to Lae.67

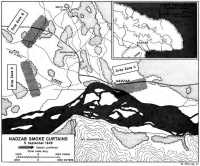

The 503rd Parachute Infantry regiment made the jump at Nadzab. Little enemy opposition was expected, but because the Japanese did have troops in the vicinity of Lae and at the Heath Plantation, between Lae and the immediate objective, there was some chance of encountering one of the daily patrols which scouted the Nadzab area. To take care of any such possibility the airdrop was preceded by B-25’s which worked over the area with .50-caliber machine guns and parachute fragmentation bombs. Seven A-20s followed armed with smoke tanks to screen each of the three drop zones from possible enemy observation. (Map 7) Eighty-one C-.47’s fell in behind the smoke-laying A-20s. The troops began jumping at 1020 and within five minutes the entire

Map 7: Nadzab Smoke Curtains

force was on the ground. No Japanese were encountered; casualties were minor.68 No doubt the distinct success of the landings was the result of the total lack of opposition at Nadzab.

The smoke phase of the operation, while generally successful, revealed the expected inadequacies in procedure which accompany any such pioneering effort. Each of the seven A-20s carried four M10 smoke tanks, a versatile munition which served also as a spray tank for toxic agents. Slung under the wings of aircraft, the M10 tank

had a capacity of thirty gallons and when filled with the smoke agent FS weighed a total of almost 550 pounds.69

On the morning of the Nadzab operation weather conditions were almost ideal for putting down a curtain of smoke. The wind was blowing from northwest to southeast at an estimated five miles an hour. Although the sky was clear there was a high overcast. The 80° temperature was accompanied by a humidity of 85 percent, a favorable condition for a good curtain, dependent as FS is on the moisture in the atmosphere.70

In 2 groups of 2 and one of 3, the A-20 attack aircraft laid the screens over Nadzab at an altitude of 250 feet and a speed of 225 miles an hour. Each of the tanks was filled with 19 gallons of the agent, or a total for the 28 tanks of approximately 532 gallons. In each formation the pilot of the lead plane discharged 2 tanks, counted 4 seconds, and discharged the remaining 2. Staggered slightly to the rear, the other A-20 went through the same procedure, allowing for a slight overlap to insure the continuity of the screen. The smoke settled quickly to the ground and then rose to an average height of 400 feet along each of the three 4,500-foot screens. Each screen lasted about 2 minutes, the length of time prescribed in the operational plan. Still effective after 5 minutes, the smoke rose, bunched, and dispersed after 10 more minutes had passed.

How effective would these smoke curtains have been if the paratroopers had landed in the face of enemy opposition? Maj. Tristram J. Cummins, Jr., Chemical Officer, Fifth Air Force, felt that two of the screens were too close to the wooded areas to have screened the observation of Japanese had they been located in the outer fringes of the woods. If the screen had been placed 2,000 feet from the woods, the troopers could have landed and organized with a potential enemy still cloaked by the drifting smoke. The operation also disclosed shortcomings in filling equipment and difficulty with the attachment of tanks to the aircraft.

It seems that little use was made of the lessons learned at Nadzab in the application of air smoke to the next Pacific airborne operation—

Smoke shields a paratroop drop, New Guinea

the jump at Kamiri airdrome on the island of Noemfoor. Capture of the island, which lay just off the coast of northwestern New Guinea, would neutralize the Japanese on nearby Biak and provide airstrips for the Allied advance on the Vogelkop Peninsula. Again, the jump was made by paratroopers of the 503rd Parachute Infantry regiment; their 3 July 1944 airborne attack followed by one day the amphibious landing of the 158th Regimental Combat Team (RCT).71 Because of the success of the assault landing, the troopers of the 503rd landed without encountering enemy opposition. Two smoke missions preceded the airdrop. B-25s used M47A2 white phosphorus bombs to blanket nearby Kornasoren airdrome and its antiaircraft batteries. Then three A-20 attack bombers, each with two M10 smoke tanks, moved in the van of the C-47’s with their cargo of paratroopers.

The weather, similar to that at Nadzab but with a bit more humidity, favored the use of smoke. But the six smoke tanks on the three attack bombers, not enough to lay a screen for the required two and a half miles, produced a patchy, hole-filled curtain over the airdrome. Consequently, the troopers jumped into a undeveloped screen and were still jumping as the smoke began to dissipate and as a southeasterly wind blew it directly over the drop zone, creating hazard and confusion. The hard surface of the airstrip, the debris with which it was cluttered, and the low altitude from which the jump was made combined to produce casualties totaling 10 percent, an abnormally high rate. Next day another battalion jumped onto the same airstrip, this time without a smoke screen. Casualties were 8 percent, high enough. for the task force commander to call off a scheduled third jump.72

By way of explanation for the rather shoddy smoke operation, the Fifth Air Force chemical officer cited insufficient notice of the impending mission and the lack of opportunity for the wing chemical officer to participate in the operation’s logistical planning. Whatever the fault, the fact remained that not only was smoke for the mission inadequate but no planes were in reserve to patch up the screen once it got spotty.73

The last use of smoke in Pacific airborne operations took place on 23 June 1945 over the Camalaniugan airstrip in northern Luzon. The airdrop, carried out by a reinforced battalion of the 511th Parachute Infantry, coincided with a drive down the Cagayan River valley by Sixth Army’s 37th Division and the occupation of the coastal town of Aparri by a Ranger task force. Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, Army commander, expected that this combination of actions would pinch out the remaining Japanese forces in northern Luzon.74

Smoke was needed to conceal the troopers from the observation of Japanese forces suspected to be in positions in the wooded hills four miles to the southeast of the airstrip. Three B-25s, each equipped with a single tank, laid down an intervening screen. The E1 tank, developed in the Southwest Pacific by the V Air Force Service Command,

carried 167 gallons of liquid FS smoke and featured a discharge valve which could be opened and closed during the course of a mission.75 This was in decided contrast with the M10 smoke tank, used at Nadzab and Noemfoor, which expended smoke all at one time.

The weather over northern Luzon was ideal for the smoke mission. The three B-25’s took off from an airfield to the south and arrived over the target at 0855. A pair of planes made the initial run, one a scant 10 feet above the grassy surface, the other, 25 feet. They flew parallel to one another, 30 yards apart and one echeloned 100 feet to the rear, at speeds between 230 and 240 miles an hour. After an interval of several minutes the third plane reinforced the screen by laying smoke between the existing streamers at an altitude of 50 feet. Within a matter of minutes the original planes made a return run, this time at altitudes of 75 and 110 feet. The third B-25 completed the mission by making its second pass at 120 feet. The net result was a dense screen which was effective for over an hour. The first wave of C-47’s dropped its paratroopers a little after 0900, and within half an hour the second and third waves landed. The operation was featured by seven gliders which brought in artillery and heavy equipment. Jump casualties came to 7 percent of the participating force. There was no enemy opposition.76

All of the air screening operations in the Pacific were carried out unhampered by enemy opposition, certainly a factor which contributed to their over-all success. But this much can be garnered from the Pacific experience: given proper planning, an adequate amount of smoke correctly placed, and good weather conditions, smoke delivered by air could add great insurance to the success of any airborne operation.