Chapter 4: First Steps Toward Mobilization

The lightning German attacks on Denmark and Norway in April 1940, followed by the invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands in May and the fall of France in June, brought into operation the War Department’s M-day plans. As the Allies’ situation became increasingly critical, the President outlined a vast program for defense. He proposed to call to arms the largest peacetime force in the nation’s history, to equip it fully with up-to-date weapons, and to gear the economy for rapid production of implements of war. Spurred by Hitler’s victories, Congress voted huge appropriations and granted necessary powers. The course of events in Europe underscored the urgency of American rearmament. But, before the United States could mobilize, before it could create a large, modern army and realize its industrial potential for war, it first had to build facilities for housing and training troops and for manufacturing and storing munitions. As in 1917, construction emerged as the controlling factor in preparedness.

The Defense Program

In mid-May, while German armies were overrunning the Low Countries, the President asked Congress to add $732 million to the military appropriation bill for 1941, then before the Senate. The bulk of this money was to cover costs of increasing the Regular Army to 255,000 men and procuring equipment for the Protective Mobilization Force, which might soon be called out. The President’s request included $26 million for building service schools, tactical stations, storage, shelter, and seacoast defenses. It also contained a substantial sum for breaking bottlenecks in the production of critical items—$44,275,000 to enlarge the old-line arsenals and erect four new government-owned munitions plants: two for making smokeless powder, one for loading ammunition, and one for manufacturing Garand M1 rifles. Appearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee on 17 May, General Marshall recommended a further step—expansion of the Army to 280,000, the peacetime limit set by the National Defense Act of 1920. Congress quickly acceded to these requests. The augmented bill, approved on 13 June, gave the War Department $1,756,552,958 in funds and contract authorities. A total of $133,880,887 was earmarked for construction.1

On 31 May, as the German tide swept toward Dunkerque, President Roosevelt sent a second urgent request to Congress, this one for “over a billion dollars.” Directing attention to the “almost incredible

events of the past two weeks,” he urged “the speedy enlargement of the program for equipping and training in the light of our defense needs.” Roosevelt emphasized the need for munitions plants. He declared: “These facilities require a long time to create and to reach quantity production. The increased gravity of the situation indicates that action should be taken without delay.” But while he put industrial requirements first, the Commander in Chief did not neglect the need for a larger army. He coupled his appeal for funds with a request for authority to bring the National Guard into federal service.2 The German successes in western Europe and the threatened disaster to Great Britain, which possibly might involve the surrender of the British fleet, had changed the whole rearmament picture. A new urgency gripped the nation’s military planners and Congress. No longer would modest increases in the armed forces suffice. What came to be called the defense program was, after late May, a broad build-up at the fastest possible rate, not only for the immediate goal, defense of the Western Hemisphere, but also for wider demands that might lie in the future.

Two days before his second message to Congress, on 29 May, Roosevelt took the first organizational step toward expediting the defense effort. On that date he revived the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense (NDAC), a World War I agency which had never been formally abolished.3 In a fireside chat a few evenings earlier, he had cleared the way for this move, announcing that he would call in men from industry to help direct rearmament. “It is our purpose,” the President told his listeners, “not only to speed up production but to increase the total facilities of the nation in such a way that they can be further enlarged to meet emergencies of the future.” But, he added, “We must make sure, in all that we do, that there be no breakdown or cancellation of the great social gains we have made in these past years.” He saw nothing in the situation to warrant longer hours, lower standards of pay, or poorer working conditions. Rather he envisioned the New Deal and preparedness going forward together, the one furthering the other.4 An order of 24 June named the commission’s members, three to serve full time and four part time. The fulltime advisers were to be William S. Knudsen, president of General Motors; Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., chairman of the board of U.S. Steel; and Sidney Hillman, head of the CIO’s Amalgamated Clothing Workers.5

As a matter of fact, the commission had already started to function. The first meeting took place at the White House on the morning of 30 May. Since NDAC was to be his coordinating agency, Roosevelt on 6 June ordered the Army and Navy to submit for its approval contracts for “all important purchases”—later defined as those amounting to $500,000 or more. Agreements for construction as well as for

supplies would be subject to this review. The commission began almost at once to chart a course consistent with the President’s aims. By late June the members were in substantial agreement that ways would have to be found to obtain earliest deliveries at lowest prices and that work would have to be spread in such a way as to reduce unemployment and utilize idle productive capacity. They recognized that these ends were attainable only if contracting methods were both flexible and streamlined.6

While the Advisory Commission was thus engaged, the War Department, too, was bestirring itself. At the instance of Assistant Secretary Johnson and his executive, Colonel Burns, supplemental estimates were in preparation and long-range plans were under consideration for an Army of 4,000,000 men. On 11 June, the day after Italy entered the war, Johnson appointed a 7-man committee “to submit a balanced program based on military needs ... for the creation of additional productive capacity.”7 The formation of this committee was but part of an intensive effort to define the Army’s objectives which began on the 11th. Knudsen had that day demanded to know how much productive capacity the country would need and when. For the next three weeks, Johnson and Marshall endeavored to find an answer.8 In June, while the scope of the defense program was becoming clear, the War Department received its first large increase in emergency funds. On the 26th the President signed the First Supplemental National Defense Appropriation Act for 1941, providing for the expenditure of slightly more than a billion dollars. Roughly one-quarter of the money was for construction. Since it came so early, this measure did not allow for a substantially larger military force than had the regular appropriation of 13 June. The enlisted strength of the Army was raised to 375,000, but there was as yet no action on the President’s proposal to call the National Guard. A total of $84,079,584 was made available for reception centers, troop housing, airfields, and seacoast defenses. More significant was the provision of $200 million for expediting production.9 This sum was almost five times as much as the act of 13 June had furnished for the same purpose—an indication of what General Marshall in mid-June termed “the rapidly developing threat ... of the world situation.”10

By the end of the month the War Department had outlined the basic plan that would guide the first phase of its rearmament effort. Known as the 30 June Munitions Program, the plan was designed primarily to create the facilities needed to equip and maintain an army of 2,000,000 men. The President approved the program on 2 July and submitted it to Congress with a price tag of $3.9 billion on the 10th, together with

a request for 15,000 planes.11 He described the objectives, aside from aircraft procurement, as follows:–

To complete the total equipment for a land force of approximately 1,200,000 men, though of course this total of men, would not be in the Army in time of peace.

To procure reserve stocks of tanks, guns, artillery, ammunition, etc., for another 800,000 men or a total of 2,000,000 men if a mobilization of such a force should become necessary.

To provide for manufacturing facilities, public and private, necessary to produce critical items of equipment for a land force of 2,000,000 men, and to produce the ordnance items required for the aircraft program of the Army and Navy—guns, bombs, armor, bombsights and ammunition.12

The last of these objectives alone meant that the War Department would build its own munitions industry. Because critical items were by definition noncommercial articles normally not produced by private industry, most of the new manufacturing plants would be government built and owned. A vast military construction effort would be necessary to achieve the program’s goal, which was, in the President’s words, the filling of “the material requirements without which the manpower of the nation, if called into service, cannot effectively operate, either in the production of arms and goods, or their utilization in repelling attack.”13

Until now the administration had not sought to muster a citizen army. It being an election year, the President was wary of anything so controversial as a peacetime draft. Pressure for compulsory military service had, therefore, to come from other sources. It was through the efforts of the Military Training Camps Association, a group of prominent New Yorkers who had served as officers in World War I, that the Burke-Wadsworth Selective Service Bill was introduced in Congress on 20 June. That same day the President named Henry L. Stimson, one of the association’s members, Secretary of War. Roosevelt publicly endorsed the selective service measure on 10 July. Two days later General Marshall appeared before the Senate Military Affairs Committee to urge speedy passage of the Burke-Wadsworth bill and prompt action to federalize the National Guard.14 For the first time in history, Congress had before it proposals to mobilize the nation’s manpower in time of peace.

The War Department confronted a situation it had not foreseen. For twenty years top military planners had assumed that a huge emergency construction effort would not again be necessary. But the crisis of 1940 compelled the Army to undertake an even larger building program than had U.S. entry into World War I. In 1917 the Allies had held a stable front in France, their fleets had controlled the seas, and their factories had furnished munitions to American forces as well as to their own. Now German armies stood on the shores of the Atlantic, Britain was in jeopardy, and friendly nations were seeking armaments here. Moreover, mobilization occurred before this country’s formal entry

into World War II. This time the United States, largely on its own, had to outstrip Germany’s arms production. This time, too, it had to maintain a sizable army for an indefinite period on American soil.15

Early Preparations

Even before the invasion of Denmark and Norway, preparations were under way for a large-scale building program. Early in March, a week or ten days after Hartman’s return to Washington, the Chief of Staff sent for him. General Marshall wanted to know how long it would take to house 2,000,000 men. The record of the old Cantonment Division came readily to Hartman’s mind. In 1917 there were virtually no plans to start with. Yet shelter for a million men was complete five months after work commenced. Hartman thought of the plans he had developed during the past six years—the organization charts, the studies and reports, the ideal layouts, and the mobilization drawings. Then he gave his answer. If he could know at once what units were to be housed and where, if he could get the money in May or June and begin work in July, the new Army could be sheltered before 1 December. Marshall was merely seeking information he might need if and when mobilization did take place. But to Hartman this interview was the signal to get moving.16

His first step was to check the plans. Calling for the mobilization drawings, he made a startling discovery—during his stay in California, someone had altered the drawings. The size of the barracks had been reduced, roof designs had been cheapened, and studs had been more widely spaced. Plywood had been substituted for drop siding. The new structures would be cramped and weak. Some of the materials specified were scarce. In short, the drawings would not serve. The men who had helped with the original blueprints started immediately to make another set. Colonel Hartman soon received an even ruder jolt. The remainder of his plans had disappeared. Though copies had once been on file with the Construction Division, The Quartermaster General, G-4, and WPD, not one could now be found. Except for the Blossom report, which he had kept on his desk as a reference work these past twenty years, Hartman had practically no written word to guide him.17 In charting a course for emergency construction, he had to rely primarily on his own judgment and the example of World War I.

Alert to the need for sound construction planning, Colonel Burns endeavored to help by bringing in men from industry. Through the Associated General Contractors, he obtained the names of several prominent men who might be available. One was John P. Hogan, president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. A colonel in the Engineer Reserve, Hogan

had served in France in World War I. As chief engineer of the New York World’s Fair of 1939, he had directed a $100 million construction program. Late in March, Maj. Leo J. Dillon, Burns’ executive officer, conferred with Hogan in New York. The latter agreed to head a Construction Advisory Committee under the Army and Navy Munitions Board. During April Hogan and Dillon with Roosevelt’s help recruited the following outstanding men, all of whom agreed to serve without pay: Stephen F. Voorhees, past president of the American Institute of Architects; Alonzo J. Hammond, president of the American Engineering Council; Malcolm Pirnie, general chairman of the Construction League of America; and, from the Associated General Contractors, Past President E. P. Palmer and Managing Director Harding. It was to take some time for the committee to get organized, and the first meeting did not take place until 20 May.18 Meanwhile, plans for defense construction were shaping up rapidly.

By late April the mobilization drawings had undergone a hasty overhauling. Working largely from memory, veteran employees of the Construction Division restored many of the original plans, which they then hastily revised. When completed, this latest version of the “700 series” incorporated blueprints for more than three hundred structures of various types and sizes. Included were drawings of barracks, mess halls, hospitals, bakeries, and laundries; of storehouses, shops, and administration buildings; and of recreation halls, post exchanges, and theaters. There were also blueprints for roads and utilities and layouts for typical camps. While these plans resembled the “600 series” of World War I, there were marked differences. The improved standard of living accounted for certain changes. Central heating had replaced stoves. Latrines were now inside the barracks rather than in separate buildings. Other changes resulted from motorization. The stable had given way to the garage, and road nets were more elaborate.19 Secretary Stimson called attention to still another change-producing factor:–

In 1917 the cantonments were intended to house troops for a shorter period. ... We then knew that our troops were going to France and that much of their training would be overseas. There was then strong evidence that the contending forces in the war were nearing exhaustion and that, whatever way the decision went, the end was probably not far off.

Today not only are we facing a most dangerous emergency but there is strong evidence that this emergency may be very prolonged.20

With this situation in mind, Hartman introduced more durable features into the plans. Two important changes were the substitution of concrete foundation piers for wooden posts and the addition of termite shields. Another, aimed at reducing maintenance costs, was the addition of canopies, or, as they were generally called, “aqua medias” or

“eyebrows.”21 When Hitler attacked through the Low Countries, the Construction Division had on hand drawings for quick, cheap, and serviceable camps—drawings that still lacked complete details but could nevertheless be made to do.

Three days before the big German offensive, on 7 May, the G-4, General Moore, asked the division to compute the cost of sheltering 1,200,000 men. The estimating task fell to Major Nurse. It was a formidable assignment. Since sites were still unchosen, he could not forecast requirements for utilities, roads, and railroad spurs—all expensive items. How much clearing and grading would be necessary was any man’s guess. The same was true of drainage. Wages and prices were certain to rise; the question was how far. And, while plans for typical buildings were now available, bills of materials were still in the writing. Using the records of the 1939 projects and such other information as he could gather, Nurse arrived at a figure of $800 per man for divisional cantonments. This was a rock-bottom estimate. Keeping within it would probably take considerable doing, but to ask for more was to invite refusal. Hartman checked the figures and double-checked them, as did Joseph A. Bayer of the Funds and Estimates Section. Then, the three men called on General Moore.22 “When we presented our estimates,” Bayer recalled, “he seemed shocked they were so high. We felt that they were low and we did expect difficulty in accomplishing our mission with the moneys we had requested.”23

Even at this late date, few in the General Staff recognized the need for an all-out construction effort. The hope persisted that large numbers of men might be housed in tents and existing buildings, that the experience of World War I need not be repeated. Describing the General Staffs attitude during the spring of 1940, General Gregory said: “In the original mobilization plans, you see, it was planned to call up a unit and put them in fairgrounds, tents, and buildings. They couldn’t seem to get that out of their heads, to realize that they would need something more, that they would need some place in which to train successive groups of men.”24 At a mid-May conference, General Marshall said that the shortage of shelter was “no serious obstacle” to the raising of a million men.25 The Chief of Staff made no pretense of being an expert in logistics. As a matter of fact, he left logistical matters largely to General Moore.26

Confronted with Nurse’s figures, the G-4 refused categorically to entertain so high an estimate. Even assuming that divisional cantonments were to be built and that the 700 series plans would be followed—the General Staff had not yet finally accepted either proposition—the price was out of line, he said. Hartman emphatically disagreed, maintaining that

the Quartermaster figure could only be trimmed by dropping desirable features, such as paved roads, theaters, and recreation halls. Judging from experience, such action seemed inadvisable. Hartman pointed out that the camps of World War I had barely been started before demands arose for these and similar refinements. Moore nevertheless reduced the estimate to $650 per man by eliminating the “frills.” Then, fearing that Congress would refuse even that amount, he slashed the figure again, this time to $400. Hartman, Nurse, and Gregory fought hard for a realistic estimate, but General Moore held firm. In the end The Quartermaster General got orders to use $400 per man as the basis of future requests. At the time, there was speculation as to whether Moore was acting on orders from above.27 Questioned about this later, he replied:–

I was responsible for cutting the estimates. It was contemplated at that time that all training was to take place in the South where tents could be used. The neutralism in Congress made it expedient to keep estimates as low as practicable. We asked for what we thought we could get. The estimates were checked with what it cost to build a construction town at Fort Peck, Montana, per man, in 1934.28

In terms of the construction task ahead, Moore’s figure was appallingly low. Before many days had passed, the General Staff accepted the fact that some divisional cantonments would indeed be necessary. Shortly thereafter the Staff adopted the 700 series plans as standard for emergency projects. Colonel Hartman tried to gauge how far $400 per man would go. First he set aside $50 per man for utilities, a small sum but all that Moore would allow. Then he went down the list of facilities the G-4 had approved, counting the cost of each. When the total reached $350, he drew a line. Above it were the bare essentials, barracks, mess halls, storehouses, hospitals, and temporary roads.

This much and no more could be had within the limit imposed. Hartman was under no illusions that other features would not soon be added. Although he could not avoid a sizable deficit, he did hope to prevent the shortage of funds from hampering the building effort.29 When the Hogan committee met in Washington late in May, the draft of a fixed-fee contract was ready for review. Although the members suggested several changes, they approved the agreement and recommended its use.30 Noting that work on detailed plans and specifications could not start until sites were picked, they reported to ANMB on 10 June: “Attempts to let competitive contracts without adequate contract drawings inevitably result in confusion, delay, and increased costs over any other method ... the first priority contracts should and must be done on a management basis.”31 The construction press echoed

the committee’s views. Advocating use of fixed-fee contracts on emergency projects, the editors of the Engineering News-Record argued:–

Its advantages for the government lie in the speed with which work can be gotten underway, in flexibility of handling changes in plans, in increased efficiency through being able to work with the contractor as a partner, and finally in reduced cost by eliminating the necessary contingent items in a competitive bid. To the contractor the negotiated agreement offers freedom from uncertainty of labor rates, material prices, weather, and unforeseen difficulties. It also gives the contractor assurance of a profit. ... Without question such a contract is the proper instrument for the job at hand.32

With these opinions, Colonel Hartman fully agreed. Moreover, from his standpoint, there was still another advantage. Fixed-fee contracts, unlike lump sum, could be let on the basis of “guesstimates.”

Toward the end of May, at Woodring’s request, the chairmen of the Military Affairs Committees, Senator Sheppard and Congressman Andrew J. May, introduced twin bills to authorize use of negotiated contracts in this country. Although the old law of 1861 permitted waiver of advertising in emergencies, Secretary Baker had been roundly criticized for invoking that authority in 1917. This time the War Department sought congressional approval beforehand. The bills made good progress at first. The House took only three days to act on the proposal. But when the matter came before the Senate on 10 June, a hitch developed, as Senator McKellar offered an amendment to outlaw “what is known as the cost-plus system of contracting.” Reminded “how much trouble was caused” by the contracts of World War I, the Senate agreed to the rider.33 On learning what had happened, Hartman appealed through the Secretary of War to Senator Sheppard, who promised to help. At Sheppard’s urging the House and Senate conferees threw out the McKellar amendment and in its place adopted the following clause: “the cost-plus-a-percentage-of-cost system of contracting shall not be used ... , but this proviso shall not be construed to prohibit the use of the cost-plus-a-fixed-fee form of contract when such use is deemed necessary by the Secretary of War.” The Act of 2 July 1940, which empowered the Secretary to let contracts “with or without advertising,” contained this clause.34 Hartman had crossed the congressional hurdle. He had still to convince his superiors that fixed-fee contracting was unavoidable.

When the fixed-fee measure entered the legislative mill, the Hogan committee turned its attention to another aspect of the problem—the capacity of industry. Through the AGC the committee learned how many construction firms were available and how much work they could handle. According to information furnished by Managing Director Harding, the nation had approximately 112,000 contracting enterprises. Nearly 80,000 functioned as subcontractors, while 17,000 more were small general contractors whose business had amounted to less than $25,000 in 1939. Some 10,000 firms were in the $25,000 to $100,000 bracket and 5,000 were in the

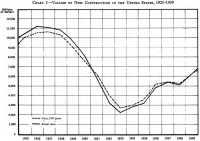

Chart 2: Volume of New Construction in the United States, 1925–1939

Source: H Doc 330, 80th Con. 1st Sess, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789–1945: A Supplement to the Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington, 1949), p. 108.

Table 4: Construction Workers in the United States, June 1940

| Classification | Number |

| Total | 2,627,157 |

| Masons | 137,934 |

| Carpenters | 697,479 |

| Electricians | 266,880 |

| Engineers | 58,091 |

| Painters | 352,127 |

| Plasterers and cement finishers | 73,120 |

| Plumbers and steam fitters | 213,634 |

| Sheet metal workers | 68,789 |

| Laborers, building | 372,092 |

| Laborers, road and street | 259,523 |

| Apprentices | 40,105 |

| Truck and tractor drivers | 87,383 |

Source: Report of the AGC to Constr Advisory Comm, ANMB, Jun 40, sub: Constr Workers in the Continental U.S. USW Files, 134 Constr.

$100,000 to $1,000,000 category. At the top of the industrial pyramid were 500 big concerns whose individual gross receipts had exceeded $1,000,000 during the previous year. As Harding pointed out, these statistics did not tell the whole story. Hit hard by the depression, the industry had not yet fully recovered. (Chart 2) Allowing for some shrinkage during the lean years of the thirties, Harding estimated unused construction capacity at about $3 billion dollars. If, as he indicated, there was plenty of contracting talent available, the Army’s job would be primarily one of choosing firms wisely and quickly putting them to work.35

A second industrial element, construction manpower, also came in for a good deal of study by the Hogan committee. With eight million unemployed in the country, the supply of unskilled labor was for all practical purposes unlimited. But Hogan and his colleagues had reason to think that getting enough skilled workmen might be difficult. The industry, which had employed 3,340,000 persons in 1929, offered jobs to only 1,610,000 a decade later. The sensitivity of construction to changes in the business cycle had lessened its appeal for young men. Moreover, the unions, long dominated by a philosophy of job scarcity, had rigid entrance requirements.36 At the committee’s request, the AGC took a census of construction workers. The count turned up 2,627,157 experienced workmen. (Table 4) This number might prove adequate, Chairman Hogan said, “provided all were usefully and advantageously used.” He nevertheless predicted trouble. The survey showed that three out of every five workers lived in the New England, Middle Atlantic, and Great Lakes States, far from the probable centers of emergency construction activity, the South, Midwest,

and Southwest. Furthermore, many skilled craftsmen had enrolled with WPA and might be unwilling to give up their relief status to take temporary defense jobs. Considered from the standpoint of productivity, the outlook was hardly brighter. Throughout most of the industry, hand methods still prevailed. Union workmen were accustomed to a 30-hour and nonunion to a 40-hour week. Under the circumstances, shortages were almost certain to develop. Contractors, pressed for speed, would compete for trained workmen. Wages would spiral and efficiency decline. Although he offered no solution, Hogan recommended that some means be found to prevent local shortages. “Otherwise,” he warned, “we will only be repeating conditions that existed during the last World War, which were notorious.”37

The committee also considered requirements for architects and engineers. At Hogan’s suggestion, professional societies began canvassing their members, 115,000 in all, to find out how many would be free to take emergency assignments. The information was to be of great value. The immediate problem, however, was one of time. Reporting to the Munitions Board on the outlook for defense construction, the committee listed lack of detailed plans as “the principal bottleneck.”38 To fit typical blueprints to the sites, to lay out roads and utilities, and to complete contract and working drawings would, they said, take 20,000 engineers, architects, and draftsmen a full year. Early projects would have to start with a minimum of plans, but for later ones thorough preparations could and should be made. The committee recommended that $15 million be granted at once for architectural and engineering services and that $35 million more be added later. In this way, they maintained, six months could be saved on the Army’s long-term projects and one year cut from mobilization schedules.39 The proposal was an excellent one. Unfortunately, Assistant Secretary Johnson did not act upon it.

While accepting the committee’s help, Colonel Hartman was consulting men more familiar with emergency construction. During June various leaders of the old Construction Division of the Army showed up at the Munitions Building. Some came to volunteer their services, among them General “Puck” Marshall. Others came at Hartman’s invitation. A telephone call to Whitson brought both him and Gunby hurrying to the Capital, where they were joined by Gabriel R. Solomon and Frank E. Lamphere, Gunby’s successors in the old Engineering Branch, W. A. Rogers of Bates & Rogers, and several more who had agreed to come to help their wartime buddy, “Baldy” Hartman, get started. Though most of them were now too old for active duty, these veterans were to serve their country again, this time in a different capacity. Forming an unofficial advisory board, they were soon furnishing valuable suggestions as to how to run the program.40

Much that Hartman did or attempted to do in the late spring and early summer of 1940 reflected the World War 1 experience. In 1917 the Army had had to use wood stave piping. With that fact in mind, he persuaded the foundries to start casting two thousand miles of iron pipe. He did this on his own initiative and with no funds in hand. Similar moves which needed War Department backing failed. Knowing that centralized procurement had worked well before, he asked Generals Moore and Marshall to help him obtain $50,000,000 from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) for a lumber stockpile. They turned him down. Recalling that confused and slow-moving audits had occasionally handicapped the earlier effort, he appealed to Johnson for money to develop an accounting system for fixed-fee contracts. This, too, met refusal. To obviate the overcrowding and frequent moves that had plagued the wartime division, he proposed to erect temporary offices on the parking lot behind the Munitions Building. As Gregory recalled it, General Moore just “pooh-poohed” the idea.41 It was with this kind of help from above that Hartman set out to build an emergency organization.

Creating an Organization

The Construction Division was unequal to the task that confronted it. The organization Hartman had inherited from his predecessor was geared to the programs of the past. On the eve of the defense effort the Washington office consisted of three branches—New Construction, Real Estate, and Repairs and Utilities—and four independent sections—Legal, Administrative, Labor, and Funds and Estimates. Manning the division were 14 officers and 1,470 civilians. Field operations were under the supervision of some 75 constructing quartermasters and 8 Vicinity offices. Field employees totaled 2,921. The organization that had performed creditably for many years now required considerable strengthening. Needed were large numbers of officers—Hartman put the total at 3,500—and a host of civilians. Needed, too, was an administrative framework capable of quick expansion.42 Recalling his struggles to bolster the Construction Division, Hartman said, “We in effect started from scratch.”43

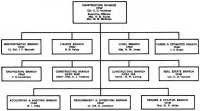

On 15 June he reorganized his office along the lines of the World War I division.44 With the help of two executives, Major Nurse and Maj. Mortimer B. Birdseye, Hartman planned to direct the defense program through eleven branches, eight of which would be new. (Chart 3) Heading the older units were long-time members of the division: Major Violante, Construction-Lump Sum (formerly New Construction); Colonel Valliant, Real Estate; and Major White, Repairs and Utilities. Mr. Bayer was a logical choice for the Funds and Estimates assignment. To head the Legal Branch, Hartman picked Maj. Homer

Chart 3: Organization of Construction Division, OQMG, June–November 1940

Source: Orgn Charts, Constr Div, OQMG, 1940, EHD Files.

W. Jones, an attorney who, after serving many years in the Quartermaster Corps, had transferred in 1939 to The Judge Advocate’s Department. A veteran Quartermaster supply officer, Lt. Col. Simon Jacobson brought a wealth of purchasing know-how to the new Procurement and Expediting group. Other branch chiefs came from private life. Burnside R. Value, a distinguished consulting engineer, headed Liaison; Oscar I. Koke, a prominent C.P.A., Auditing and Accounting. Ira F. Bennett, a top engineer at Charles T. Main and a lieutenant colonel in the Quartermaster Reserve, took charge of Administrative. Mr. Lamphere, who had won high praise for his recent work on the Pennsylvania Turnpike project, returned to his old position as chief of Engineering. For the Fixed Fee post, Colonel Whitson suggested Harry W. Loving, secretary of the Carolinas Branch of the AGC, who joined the Division in July. Seven of Hartman’s key assistants—Nurse, Violante, White, Jones, Koke, Bennett, and Lamphere—had served with Construction in World War I. All were experts in their fields.

An important adjunct to the division came into being in July. During June Hartman had stressed the need for a board of outstanding civilians who could, like the Starrett committee of World War I, assist in selecting firms for fixed-fee projects. Without contractors of high integrity and superior ability, the fixed-fee system would fail. Hartman insisted that applicants be judged on merit alone and that politics never be a factor. His first thought was to have either NDAC or the Hogan committee handle the work of selection. When both declined—they were not set up to do the job, they said—Hartman decided to go it alone. Early in July he formed the Construction Advisory Committee, OQMG, composed of Francis Blossom, Forrest S. Harvey, and Ferdinand J. C. Dresser. Blossom, a senior partner of the prominent New York firm of Sanderson & Porter, had received wide recognition for his work as chairman of the Board of Review of Construction in 1919. Harvey, a veteran of the Construction Division of the Army, was a civil engineer of unusually broad experience. He came to the committee from Leeds, Hill, Barnard and Jewett of Los Angeles. Dresser, director of the American Construction Council and president of the Dresser Company of Cleveland, had served as a member of the National Board for Jurisdictional Awards, the now defunct “supreme court of the building industry.” He had later held important posts in PWA. Since Blossom, the most distinguished member, was approaching seventy, the chairmanship went to Harvey. On 15 July General Gregory took the committee under his wing, making it directly responsible to him, and giving it a threefold mission:–

to serve as a point of contact with the construction industry; to collect and analyze data relating to architectural, engineering, and construction firms; and to advise Hartman in the choice of contractors for fixed-fee projects.45

To carry out their emergency assignment, Hartman and his principal assistants would need a large number of experienced helpers. The Washington

Ferdinand J. C. Dresser, Forrest S. Harvey, and Francis Blossom

staff would have to double in size. By early summer dozens of jobs were waiting for engineers, architects, draftsmen, lawyers, real estate men, and consultants of various sorts. The field had countless openings. Scores of projects would soon be starting up and every one of any size had to have a constructing quartermaster along with a crew of assistants. The proposed changeover to fixed-fee contracts would create work for a host of new employees, for these agreements, unlike fixed-price, demanded meticulous government supervision. Since the Army would, in effect, be paying the contractors’ bills, the Comptroller General would insist on a thorough scrutiny of all expenditures. In order to safeguard the public interest, Hartman planned to put auditors, accountants, inspectors, timekeepers, and materials checkers on Quartermaster payrolls at fixed-fee projects. Together, the home office and the field would offer jobs to some 40,000 persons in the months to come.46 Finding so many qualified people was to be immensely difficult.

Public indifference, red tape, and failure of top officials to appreciate what he was up against hampered Hartman’s efforts. The mobilization of 1940 evoked no such patriotic response as had the declaration of war in 1917. Throughout the country an atmosphere of business-as-usual prevailed. And the construction business was, at long last, beginning to boom. Since a full colonel received about $6,000 in 1940 and Civil Service pay rates were correspondingly low, men needed a strong sense of civic duty to leave prospering firms or high-salaried jobs and take service with the Constructing Quartermaster General. Some were willing to make the sacrifice. But many of those who offered to help

found their way barred by rules suited rather to peacetime conditions than to a crisis that was bordering on war. The Army stuck, for the most part, to the letter of its regulations. The Civil Service Commission was slow to change its procedures. With adequate topside support, Hartman might have surmounted some of these obstacles. Such support was not forthcoming.

A drive for recruits was under way before the fall of France. Late in May Hartman summoned Major Thomas, then constructing quartermaster at Hill Field, Utah, back to Washington to help. A short time later August G. Sperl, another alumnus of the wartime division, was called down from New York. He arrived to find Major Thomas run ragged. Applications from contractors were pouring in and there was as yet no one else to handle them. The entire division was swamped with work. Reporting to Hartman, Sperl got orders to start organizing. Men were needed at once. It was up to him to get them. Assured of Hartman’s backing, Sperl rounded up some more old-timers and got down to business. Hard-pressed though he was, Major Thomas found time to give advice and direction. In mid-June the call went out to professional societies, contracting firms, and colleges and universities: “Send us men.” Considering the temper of the times, the response was good. During the next few weeks, some 1,600 construction men offered their services.47

Military custom decreed that positions of authority be held by officers. As a rule, only men in the chain of command made decisions and issued orders. That was the Army system. To keep within it would not be easy. Of the 824 Quartermaster Regulars on active duty in June 1940, barely more than 100 were experienced in construction work. The division had no Reserve of its own, and although the parent corps had a sizable one of 6,249 officers, few of them were engineers or builders. Colonel Hartman considered three methods of getting additional officers: one, obtaining Regulars from other branches of the Army; two, tapping the Reserves of other branches; and, three, commissioning men from civil life. The first held little promise. An early request to General Schley for the loan of fifty officers was refused on the grounds that the Corps of Engineers was already stretched too thin, and the Chief of Staff declined to intercede on the Quartermaster’s behalf. Of the remaining possibilities, the second method offered easiest access to large numbers of officers; the third, the surest means of obtaining competent professionals.48

Begun in May, the quest for Reservists was at first unsuccessful. The Quartermaster General and the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1, were unable to provide lists of Reserve officers qualified for construction assignments. Neither could the corps area commanders. Moreover, not until Congress acted, as it did four months later, could Reservists be forced to come on active duty. Drawing on his own acquaintance among construction men, Hartman lined up a number of experienced officers but then had difficulty getting them appointed. Other

branches had prior right to many of these men, a right they were unwilling to surrender. The Adjutant General ruled that men past fifty would not be called to active service. The Surgeon General listed flat feet, false teeth, glasses, high blood pressure, and overweight as grounds for rejection. Yet because the depression years, with their crippling effect on the industry, had produced few construction specialists, most of the men who were best equipped to do the job at hand were of the older generation. To make matters worse, The Adjutant General barred members of the inactive Reserve, a group that included many outstanding professionals who had been too busy with civilian work to take time for training. Deprived of men he badly wanted, Hartman asked to have the rules relaxed. He argued that age, physical condition, and military experience had little bearing on the suitability of officers for desk jobs. Still, The Adjutant and Surgeon Generals refused to take men who might be unacquainted with military customs or who might later claim pensions and disability pay. Even when men turned up who met the War Department’s requirements, it took a long time for their orders to go through. Flooded with emergency requests, The Adjutant General’s Office was fast becoming an almost impassable bottleneck.49

On 22 June Hartman appealed to the corps areas for help. In a radiogram he asked the nine commanding generals to circularize all Reserve officers and invite those with construction experience to apply to The Quartermaster General. The plan was to have qualified Reservists called to duty not by The Adjutant General but by the corps area commanders, who would then detail or transfer the men to the Quartermaster Corps. Hartman would thus be able to get around some of the difficulties that delayed appointments by the War Department. The commanders were cooperative. Soon Sperl was working night and day poring over the papers of some 6,000 applicants. Meanwhile, Gregory persuaded Marshall to give him priority on all Reservists, regardless of branch. Hartman might now enlist any member of the active Reserve who could pass a physical examination and was willing to serve. Although a large percentage of the volunteers were not full-fledged construction men, the arrangement with the corps areas did enable the division to obtain a number of highly qualified officers whose subsequent record of performance was outstanding. It also saved valuable time that would have been lost in awaiting action by The Adjutant General.50

Even with the influx of Reservists, the demand for officers far exceeded the supply. In mid-July 1940 the Construction Division had 200 vacancies—10 for colonels, 50 for lieutenant colonels, 105 for majors, and 35 for captains—and 700 more openings were about to materialize. Writing to The Adjutant General on the 18th, General Gregory indicated that it might soon be necessary to commission men from civil life.

As a matter of fact, Colonel Hartman was already moving in that direction. From among the civilians whose applications were on file he had selected sixty who were well qualified by experience and training to head construction projects. These men became the first candidates for direct commissions, many in the coveted grades of colonel and lieutenant colonel. But Hartman had reckoned without the Reserve Officers Association, which stepped in to demand that its members get preference over civilians. He had also reckoned without Stimson and Marshall, who, in contrast to their opposite numbers in the Navy Department, were reluctant to grant direct commissions.51 “We would have a good man we wanted to commission,” General Gregory related. “They would refuse to do it at the General Staff. Mr. Stimson would say that he would have to go to camp first. Then the Navy would make him a lieutenant commander right off the bat.”52 Thus, Hartman lost the services of many of the best men available.

Similar difficulties attended the hiring of civilians. Just as Army regulations limited the choice of officers, so Civil Service rules restricted employment. Wishing to preserve its usual standards of selection, the Civil Service Commission adhered closely to the customary formalities. Hartman was seeking to put through appointments in twenty-four hours. Yet one step in the Civil Service procedure took anywhere from one week to two months; another, from two weeks to three months; a third, about a fortnight. During the seemingly interminable wait, many good prospects gave up in disgust and took other jobs.53 Equally distressing to Hartman was the commission’s insistence that he draw personnel from its lists of eligibles:–

The Civil Service rosters contained many misfits who had lost their positions due to the depression [he later wrote]. A substantial number of these did not live in the Washington area. We found they did not have the money to travel to Washington for an interview and a heavy percentage were not qualified for our undertaking.54

An early report from Fort Ord, California, forecast trouble in the field. The constructing quartermaster at Ord had asked the local Civil Service office to furnish him with high-grade administrative and technical personnel. The registers had yielded one draftsman, one engineering aide, two clerks, and four laborers.55

Anticipating difficulties of this sort, Hartman had started early to make arrangements for hiring his own top-level personnel. At his request, Congress had on 2 July enacted legislation empowering the Secretary of War to “authorize the employment of supervising or construction engineers without regard to the requirements of civil-service laws, rules, or regulations.”56 Hartman hoped to get a sizable number of building experts on the payroll quickly. He intended to place some of them under

bond and put them in complete charge of projects.57 But this was not to be, for the President opposed the plan. On 9 July the White House asked Acting Secretary Johnson to tell appointing officers “that no employments should be made under this exemption until after consultation is had with the Civil Service Commission to ascertain its ability to handle the recruiting problems involved.”58 Two days later Stimson gave Gregory his orders. Hartman was not to go outside the Civil Service structure without the commission’s leave. The legislation may nevertheless have served to strengthen Hartman’s hand, for the Commission now displayed a somewhat greater willingness to relax its regulations. Personnel for the Washington office no longer had to come from lists of eligibles. Although employment in the field continued slow, appointments to Hartman’s immediate staff began going through more rapidly.59

The construction ranks swelled gradually, and by August 1940 the small central office was filled to overflowing. Reinforcements were coming from all parts of the country. Many competent technicians responded to the call of old-timers like Colonel Whitson, who worked zealously to round up qualified men. Some of the newcomers persuaded friends and associates to join them, and these, in turn, persuaded others. A sizable group of experts transferred from PWA, which was going out of existence. Meanwhile, the professional societies kept a steady stream of applications coming. On the whole, the new civilians were well suited for their tasks. As a group the new officers left more to be desired. The supply of qualified Reservists had run out all too soon. Unable to obtain officers from other sources, Hartman dipped more deeply into the Reserve. With the big push in construction about to begin, he took the only expedient course accepting men who were available without quibbling over their qualifications. One of Loving’s assistants afterward estimated that only four out of every ten new officers had the necessary background. This lack of experience was in part offset by training. Major Thomas established a school for Constructing Quartermasters, which Reservists had to attend before they went to the field.60

By late summer Hartman and his colleagues had put together a serviceable organization. In the months to come they would direct their efforts toward expanding and perfecting it.

Site Selection

As Chief of Construction, Hartman had a vital interest in the location of facilities to house, train, and supply the expanding Army. If mobilization objectives were to be met—if a citizen army were to be quickly raised, the Air Corps speedily enlarged, and a munitions industry created within a year or eighteen

months—and if the cost were not to be exorbitant, building sites must lend themselves to rapid and economical construction. Climate, terrain, vegetation, soil, subsurface conditions, and the availability of transportation, utilities, labor, and materials would to a large extent determine both the rate of progress and the final cost. And if acquisition were not to be a stumbling block, sites must be readily obtainable. Balky owners and uncertain titles would force the Quartermaster Corps to take legal action before it could get possession of the land. Even so, Hartman’s role in choosing new locations was often that of a bystander.

Military considerations were of first importance in deciding where to build. Troops and planes must guard the coasts against invasion. Divisions must train in varied climates, some in the North where they could accustom themselves to the rigors of winter weather, some in the South where long summers and vast acreage made uninterrupted training and extended maneuvers possible. Pilot instruction must be carried on where weather permitted flying the year round. The munitions industry must be placed well inland, away from likely areas of attack, and plants must be located where conditions favored maximum production.

But the Army was not free to choose locations for purely military reasons. In virtually no other area of defense activity did it feel the pull of so many diverse interests. Establishment of hundreds of new military installations and transfer of large tracts of land from private to public ownership had wide significance. The War Department’s choice of sites might mean financial prosperity to communities and individuals—or substantial sacrifice. Many cities entered strong bids for defense projects, while some fought desperately to keep the Army out. Nor was military site selection without political and social implications. The situation presented Senators and Representatives, as well as local officials, with an opportunity to promote the welfare of their constituents. On 31 May 1940 an Oklahoma Congressman told his fellow members of the House Appropriations Committee: “I am enthusiastically supporting the President’s billion-dollar program … and I am going to insist that at least one of these bases be established in Oklahoma.”61 Such statements were by no means uncommon. The program also opened a way for the Roosevelt administration to spur recovery by locating plants in distressed areas.62 The Army received many demands for special consideration which were sometimes too strong to be ignored.

Front runner in the race for sites was the Air Corps. Late in May, while Congress was considering a proposal to train 7,000 pilots a year, General Arnold submitted to the General Staff a plan for establishing three large Air Corps training centers. The first, the Southeast, was to consist of Maxwell, Barksdale, and Eglin Fields, and a new station in Alabama. The second, the Gulf Coast, was to include Randolph, Brooks, and Kelly Fields, and two new stations in Texas. The third, the West Coast, was to be made up of Moffett Field and a new station in California. The Staff

Barksdale Field, Louisiana, in late 1930s

approved the plan on 6 June, and on the 13th, the same day that funds became available, Arnold convened a site board composed entirely of air officers. After a cursory investigation, the board recommended new flying schools at the municipal airports at Montgomery, Alabama, and Stockton, California, old Ellington Field (a World War I flying field near Houston), and an unimproved site at San Angelo, Texas. They suggested placing a fifth school near Selma, Alabama.63 Arnold promptly sent the board’s report to the General Staff, where it got a mixed reception. The Air Corps had acted with great dispatch; no one questioned that. But, according to General Moore, the Staff was “somewhat embarrassed by the lack of detail furnished.” While advising Marshall to accept the board’s selections, the G-4 warned: “A great deal of basic information had to be taken for granted in the hurry to institute these projects. The system followed is eventually certain to result in the selection of some localities which may be regretted at a later date.” On 3 July Moore and Marshall agreed that sites for Air Corps projects should be picked by War Department boards, appointed by the General Staff.64

By this time Arnold had formed

another board to select locations for the tactical units to be pulled out of Maxwell, Barksdale, and Moffett Fields and for the additional combat groups authorized by the supplemental appropriation of 26 June. The Air Corps board was short-lived. On 12 July General Moore named three War Department site boards, one for the East, one for the South, and one for the Pacific coast. Each had a Quartermaster representative and an airman along with a General Staff officer who served as president. Barely a week passed before the boards were out inspecting municipal airports. Acting on instructions from G-4, the members checked each place to see what technical facilities, what utilities, and how many acres of land were available and what additional construction would be necessary. They also rioted the distance to population centers and surveyed housing, recreation, and public transportation facilities. Finally, they ascertained whether the field could be leased and on what terms.65

Finding fields for the Air Corps proved to be a relatively simple task. News that the War Department planned to develop civil airports brought an enthusiastic response from hundreds of cities. The site boards were warmly received everywhere they went. Most of the cities they visited offered to lease municipal fields for one dollar a year and to extend water and power lines. Many pledged land adjacent to the airports. Some went still further. The city of Albuquerque promised to build two new runways. Manchester, New Hampshire, and Spokane, Washington, promised to improve their fields. Fort Wayne, Indiana, agreed to sponsor a housing project for officers and their families. With so many inviting prospects, the boards had little trouble filling their quotas. During the first week in August they recommended no fewer than six sites to the War Department. Even so, General Arnold was sharply critical of their progress. Displaying characteristic impatience, he began early in August to demand more speed. On the 6th The Adjutant General wired the boards to expedite their work, but when Arnold continued to complain, G-4 countered with the allegation that such lags as were occurring could be traced to the Air Corps itself.66 Lt. Col. Vincent Meyer, the Acting Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, writing to General Moore, who had recently become Marshall’s Deputy, explained:–

The greatest delay in all of this procedure of getting out the construction orders for the Air Corps stations is the inability of G-4 to get accurate data as to what units are going where ... it has been necessary to change every program that we have so far issued that relates to the Air Corps … because of inaccurate or inadequate information from the office of the Chief of the Air Corps.67

Arnold’s protests thus served not only to put more pressure on the boards but also to spotlight bottlenecks in his own office. By 17 August the Air Corps and the General Staff had agreed on a tentative station list, and in mid-September

directives went out for construction at twenty-four fields.68 By selecting municipal airports, the Army had saved considerable time and expense and, at the same time, satisfied demands of twenty-four cities for defense projects. It had also avoided the multiplicity of problems that attended the location of facilities which were to be built from the ground up.

Of the thirty-five manufacturing plants in the first industrial program, all but six were to be on new sites. Thus the War Department had to find twenty-nine tracts for its munitions projects.69 The Army’s industrial services, principally Ordnance and Chemical Warfare, had long been studying problems of plant location and knew in general where they wanted to put new production and what factors they wished to consider in picking individual sites. The Ordnance Department had in 1938 and 1939 actually chosen sites for two smokeless powder plants, one near Charlestown, Indiana, the other, at Radford, Virginia. Also exemplifying this type of planning were surveys conducted by the Chemical Warfare Service, seeking inland locations for manufacturing war chemicals and equipment. But selection of plant sites was not left to the using services alone. Final decision in every case awaited concurrence of other interested parties, the President, the NDAC, the Assistant Secretary of War, and the industrialists who would run the plants.70

As plans matured for a government-owned, privately operated munitions industry, the question—where to build—required a definite answer. On 25 June Acting Secretary Johnson appointed a 6-man War Department Site Committee. Three of its members, including the chairman, Col. Harry K. Rutherford, director of the Planning Branch, OASW, were Ordnance officers. A representative of the Air Corps, a General Staff officer, and Colonel Hartman completed the membership. Johnson asked the committee to establish criteria for choosing plant sites. His instructions were: disperse plants so that an attack will not seriously cripple production; keep out of highly developed industrial areas; and pay close attention to the technical, production, and transportation requirements of individual plants.71 Rutherford and his colleagues promptly set to work.

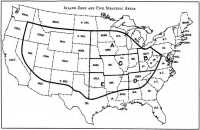

Within two weeks they had drawn the boundaries of the new munitions industry. As long ago as 1915 the War College Division of the General Staff had recommended that “as a general military principle, no supply depot, arsenal, or manufacturing plant of any considerable size ... should be established or maintained east of the Appalachian Mountains, west of the

Cascade or Sierra Nevada Mountains, nor within 200 miles of our Canadian or Mexican borders.”72 As the range of aircraft increased, the need for such a policy became strikingly apparent. The Rutherford group agreed that plants must be located between the Appalachians and the Rockies within a zone roughly two hundred miles from the nation’s borders. Networks of related factories were to be placed in five general areas within the eastern portion of this zone. (Map I) The committee planned a well-integrated industry centered in the Middle West. Turning to the matter of specific locations, it urged careful study of conditions which might affect construction and maintenance. Rutherford left the initial choice of sites to the using services; he nevertheless reserved the right to veto their selections.73

Ordnance, as the service sponsoring the largest number of new plants, was responsible for selecting most of the sites. Its primary aim was greatest production at lowest cost. Rutherford’s committee furnished site investigators with a checklist including, among other points, the availability of water, power, fuel, transportation, labor, and materials.74 General Wesson and his assistants did not rely entirely on their own judgment but continued the long-established practice of consulting such firms as DuPont and Hercules. These companies, as well as others chosen to be operators, played a large part in deciding where to locate the new plants. Indeed, one Ordnance officer said that his department “never selected a site” without the assent of the operator.75 Both Ordnance and industry believed that quantity production could be achieved most quickly if plants were near centers of industrial activity. As Brig. Gen. Charles T. Harris, Jr., chief of the Ordnance Industrial Service, put it, “The general consideration was to locate the plants conforming to the ... pattern of existing industry.”76

The course taken by Ordnance ran counter to the aims of the President’s Advisory Commission. Ralph Budd and Chester C. Davis, the advisers on transportation and farm products, fought for a decentralized munitions industry in order to balance regional economic development and help nonindustrial areas in the South and West. Sidney Hillman, who hoped to create more jobs in depressed areas, often joined forces with Davis and Budd. These men found their efforts balked by the War Department’s insistence on speed. Because requests for approval of sites were generally coupled with warnings that delay would endanger national security, the NDAC felt obliged to do what the Army asked. Not until December did the commission take a firmer stand. Then it served notice that it would “not ... accept in the future the arguments of speed and pressure as the

Map 1: Inland Zone and Five Strategic Areas

controlling reasons for approving plant sites.”77 The commission acted too late. By December sites for nearly all the early munitions projects had been chosen.

The War Department’s refusal to adopt the Advisory Commission’s views left the using services in control. Production and transportation thus became the decisive factors in the location of industrial projects. The early ammonia plants, Morgantown and Ohio River, were near the coal fields of West Virginia and Kentucky, where coke, the key ingredient, was readily available. Since oleum was the chief component of TNT, the first plants for the manufacture of that explosive, Kankakee, Weldon Spring, and Plum Brook, were near the heavy acid industries of Chicago, St. Louis, and Cleveland. Smokeless powder factories, which required large quantities of water, were alongside rivers. Radford was on the New River, the Alabama Ordnance Works was on the Coosa, and the Indiana plant was on the Ohio. The location of TNT and powder factories determined the location of loading plants. For example, Elwood, a shell loader, adjoined Kankakee, and New River, a bag loader, was seven miles from Radford. Because a good deal of manpower would be needed in their operation, the original small arms ammunition plants were put just outside St. Louis, Kansas City, and Denver. In locating several types of facilities, safety was a vital consideration. Units for making, loading, and storing explosives had to be dispersed over large tracts so that an explosion would not trigger a chain reaction. Hence, the Ravenna shell loading plant required over 22,200 acres and Kankakee, 21,000.78

Despite the fact that the Quartermaster Corps played no major role in selecting industrial sites, places picked by the using services generally met construction standards reasonably well. There were engineering problems, to be sure. Subsurface rock and poor natural drainage threatened to complicate the building of the Indiana Ordnance Works. Unfavorable terrain spelled trouble ahead at the New River bag loading plant. The difficulty of removing three large pipelines that ran beneath the Kankakee-Elwood tract caused General Harris to remark that the Joliet, Illinois, site was “the greatest mistake we made.”79 Yet, serious errors were relatively few. Level, well-drained sites, having access to adequate labor and transportation, were essential to both builder and user. Because the new munitions industry would be centered in the rich Midwestern agricultural and manufacturing region, most of the Quartermaster’s troubles were in acquiring the land rather than in building on it.

Just as Ordnance and Chemical Warfare decided questions of plant location, so the General Staff controlled the choice of camp sites. In the late spring of 1940, as plans went forward for mobilization, the Staff considered how to group and where to train a force of 1,200,000 men. General Marshall

decided to set up divisional camps and cantonments and to build a network of reception and training centers. Troops would be trained in all nine corps areas, and divisions would be placed so that they could readily form corps and armies. Adhering closely to the Protective Mobilization Plan, Marshall proposed to save time and money by expanding old posts before establishing new ones and, if additional stations were needed, to build on federal- and state-owned land. Having affirmed this policy, he left the rest to G-3 and G-4. Responsible for molding draftees, Guardsmen, and Regulars into an effective fighting force, Brig. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, was interested primarily in sites that offered training advantages. Such features as large acreage, varied terrain, streams for bridging exercises, and observation points for artillery practice were high on his list of requirements. It was G-4’s prerogative to veto any site that was unacceptable from the constructor’s standpoint. General Moore reviewed Andrews’ selections until early August, when another Engineer officer, Col. Eugene Reybold, took over the G-4 post.80

Deciding where to concentrate the Regular Army divisions and where to build the reception centers was relatively easy. General Andrews planned to apportion the nine Regular Infantry divisions among the four existing armies and to pick the best available places for training the two Cavalry and two new Armored divisions. The big permanent posts—Fort Bragg, North Carolina, with 122,000 acres, Fort Benning, Georgia, with nearly 98,000, Fort Lewis, Washington, with 62,500, and Fort Knox, Kentucky, with 33,500—were obvious choices as sites for the Regulars. Also selected as a matter of course were Fort Jackson, South Carolina, Fort Riley, Kansas, and Fort Ord, California, each of which possessed some 20,000 acres and well-developed transportation and utilities systems. Fort Devens, Massachusetts, Fort Houston, Texas, and Fort Custer, Michigan—posts which held divisions in World War 1 and had since shrunk, but which could again expand—were also earmarked for the Regulars, as was Fort Bliss, a small station in western Texas with practically unlimited room for growth. Only one new reservation, a 40,000-acre tract near Leon, Iowa, which Congress had approved for acquisition in 1936, figured in plans for the Regular divisions.81 Locating reception centers for inductees was an even less complicated task. “We must have a certain amount of distribution for these reception centers,” one member of the General Staff explained. “We can’t ship these men long distances to ... their processing, because some may be rejected and have to be sent home.”82 But because the reception centers were small—the largest was to

hold only 3,000 men—Andrews had no trouble finding spots for them at posts throughout the country.83

Only when he had to choose sites for National Guard camps and for unit and replacement training centers did the G-3 run into real difficulty. Stations for the Guardsmen and centers for trainees had been selected several years before. Attached to the Protective Mobilization Plan was a list of places where the eighteen National Guard divisions would assemble upon the outbreak of war. Some of the Guardsmen were to go to big reservations like Benning and Lewis, but since posts of that size were too few even for the Regulars, the General Staff had been forced to fall back on smaller forts, summer training grounds belonging to the States, and sites used in 1917. The planners had thought of these places as concentration points where troops would spend thirty to sixty days in preparation for shipment overseas, not as camps where divisions would train for one year. Also annexed to the PMP was a blueprint for a system of training centers, but these facilities, like the camps, were designed to meet a war situation in which units and replacements would move rapidly to the righting front.84 That numerous shifts in location became necessary was an early sign of weakness in the mobilization plans.

Construction men were the first to challenge the sites named in the PMP. On 20 May, after conferring with the Chief of Staff, General Moore sent Hartman the list of stations for the Guard together with a questionnaire. Moore wished to know what utilities there were at each location, where tents would serve, where barracks would be necessary, and how much it would cost to house the divisions. An authoritative answer would require on-the-spot surveying, and Hartman had no money for that. The most that he could do was to compile data on hand in his office and in the National Guard Bureau. Even this meager information indicated that some of the places were unfit not only for construction but for training as well.85 Meantime, Capt. Leslie R. Groves, an Engineer officer attached to G-3, had raised objections to the PMP list. On 12 June he wrote and General Andrews signed a memorandum asking G-4 if the stations in the plan were “in such a state as to permit full use in the contemplated manner by the scheduled time.”86 Hartman, replying to Moore’s questionnaire on 24 June, also stressed the need for thoroughgoing site investigations. At least six of the proposed locations were likely to cause trouble, he warned. Camp Blanding, Florida, was wooded and probably swampy. Fort Eustis, Virginia, abounded in marshes and streams. Fort Huachuca, Arizona, was too hilly for motorized units. Camps San Luis Obispo, California, and Hulen, Texas, were too small to train divisions. Fort Clark, a second Texas post, was ten miles from the nearest railroad. Information on some of the other Guard camps was so sketchy that Hartman

did not know what to expect. He urged Moore to take the only practical course, to run an “actual physical survey and study on the ground of the sites under consideration. “87

Moore had the sites surveyed but not by the Construction Division. To Hartman’s astonishment, the assignment went to the corps area commanders. Quartermaster protests were in vain. “I had never considered the Corps Area Commanders as being responsible for any of the work until I received a peremptory order to permit them to select the sites for the camps. ... I did not believe it was the intention of the War Department until General Moore insisted that it be done,” Hartman wrote.88 What followed confirmed his misgivings. One commander completed the “investigation” of a site nearly 500 miles from his headquarters twenty-four hours after the War Department asked for a report. Other commanders sent staff officers or went themselves to take the lay of the land. Several, adopting more formal methods, convened site boards. In no case was much attention paid to construction factors. Even when Quartermaster and Engineer officers visited the sites, their examinations were necessarily perfunctory, since no time was available for detailed surveys and tests. The corps area reports seldom mentioned engineering features. A number of sites were rejected but not because they would be difficult to build on.89

When authority was decentralized, the political pot began to boil. Corps area people were more sympathetic to local problems and more easily approached than that remote and impersonal entity, the War Department. Businessmen, politicians, Guardsmen, and others who sought to influence the choice of camp sites now besieged corps area headquarters. Though some of the petitioners were disappointed, a number got what they wanted. When the Chamber of Commerce of Brownwood, Texas, offered to lease a sizable tract at a nominal rent and to provide water, electricity, and natural gas at low rates, the Army, on the advice of Eighth Corps Area headquarters, accepted. Local interest groups likewise succeeded in bringing projects to Spartanburg, South Carolina, Macon, Georgia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee. In some localities, Guard commanders were also influential. Illustrative of the part they played is the case of Camp Blanding. In 1939 Brig. Gen. Vivian B. Collins, adjutant general of Florida, had chosen a 27,000-acre tract in Clay County to replace Camp Foster, a Guard reservation transferred to the Navy. Situated on Kingsley Lake and lush with palmettos, oaks, and vines, the place was a landscape architect’s dream. The climate was salubrious. Nearby was a 66,000-acre ranch, available for lease. Envisioning a splendid camp, Collins late in 1939 began to develop the site. An enthusiastic supporter of the project was Lt. Gen. Stanley D. Embick, commander of the Fourth Corps Area. Named for the Floridian who headed the National Guard Bureau, Camp Blanding soon found a place on the PMP list. When in June 1940 construction men began to talk of swamps and timber, Generals Moore and Andrews flew to Atlanta to consult General Embick, who assured them that Blanding

would make a superb division camp. A visit to the site dissolved any lingering doubts they may have had. Further protests from the Quartermaster Corps were unavailing. The Blanding episode was not unique. The story of San Luis Obispo followed much the same outline, and the fine hand of the state adjutants was elsewhere visible.90 From the sidelines Hartman watched, dismayed, while corps area commanders demonstrated what he regarded as “their lack of understanding and their lack of ability to select a proper camp site.”91

As reports came in from the corps area commanders, General Andrews revised the list of Guard camps again and again. With the discovery that Fort Eustis had no adequate maneuver area, plans for sending a division there went by the board. Terrain unsuitable for training ruled out Camp Hulen. Their isolation eliminated Forts Clark and Huachuca. Other changes originated not in the corps areas but in Washington. Plans for stationing Guardsmen at Knox and Benning fell by the way when Andrews assigned those posts to the newly created Armored Force. At the request of General Strong, who as head of WPD had care of the Army’s strategic deployment, G-3 substituted sites in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts for locations in Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Pressure for a camp in the vicinity of the Capital caused Andrews to shift the 29th Division from the Sabine River area of Louisiana to Fort Meade, Maryland. Of the seventeen preferred sites named in PMP only seven remained by late July. On the 31st General Marshall approved the revised list of National Guard camps.92 This was the first of many such lists that he was to accept before the Construction Division gained a voice in selection.

Viewed purely from a military angle, the ground forces sites were well chosen. While stations would be scattered through some thirty states, most of the training would be in the South. Geographic distribution of the division posts matched General Andrews’ requirements and General Strong’s as well. Clusters of camps and cantonments reflected the G-3 plan to organize and train nine corps under the existing armies. The heaviest troop concentrations would be in the eastern portion of the country, where in 1940 the danger of attack seemed greatest; yet no corner of the United States would be without protection. Reception centers were conveniently placed to funnel recruits from populous areas to training establishments. Most of the unit and replacement training centers likewise appeared to be ideally located. Some, like the Signal center at Fort Monmouth and the Engineer center at Fort Belvoir, were at the long-time homes of their branches and services, where excellent facilities were already available. Others, like the Field Artillery post at Fort Ethan Allen, in the hills of western Vermont, and the Coast Artillery station at Camp Davis, in the Onslow Bay area of North

Excavation at Fort Devens, Massachusetts

Carolina, were highly suitable for specialist training.