Chapter 7: The Reorganization of Late 1940

While defense preparations went forward, a concatenation of circumstances led to changes in the War Department’s construction organization. As emphasis shifted from civil works to military projects, the Corps of Engineers sought new assignments. As men identified with the old Construction Division of the Army reappeared on the scene, agitation for a separate corps revived. Under emergency pressures, flaws in the existing setup became increasingly apparent. An issue evaded for twenty years demanded solution. Long-smoldering controversies rekindled and old rivalries intensified. The ensuing struggle brought reorganization, decentralization, and new leadership for the construction effort.

The Engineers’ Predicament

From 1919 to 1939 the Engineers expended nearly $2.5 billion dollars on rivers and harbors, flood control, and fortifications. Their civil activities, including such large projects as the Bonneville and Fort Peck Dams, extended into every state and territory. The red crenelated castle, emblem of the Corps, was displayed at hundreds of sites where work went forward on levees, dikes, breakwaters, jetties, locks, dams, reservoirs, channel improvements, and seacoast defenses. To carry out its construction mission, the Corps maintained the Engineer Department, a permanent field organization consisting of 11 Divisions and 46 Districts in 1939. During the year preceding the outbreak of war in Europe, 225 officers and 49,000 civilian employees conducted the department’s work.1

With the upsurge in military construction, civil works began to decline. In fiscal year 1940, $180,141,467 was available for rivers and harbors and flood control projects as against $289,244,842 in the preceding fiscal year.2 In the spring of 1940, as Congress considered budgets for the coming year, President Roosevelt called for drastic cuts in public works and opposed new construction not urgently needed for defense. When Congress passed an authorization bill for rivers and harbors, the President vetoed it. “Regardless of every other consideration,” he said in his veto message of 21 May, “it seems to me that the nonmilitary activities of the War Department should give way at this time to the need for military preparedness.”3 He did not retreat from this position. Discussing the

Bonneville Dam

next budget with newsmen in November 1940, he stated:–

Now, of course, you have to remember this, that if the Congressmen from a portion of Chesapeake Bay wanted such and such a creek deepened from four to six feet, so that the oyster boats could get in and out more handily, we probably would have all kinds of briefs up here to prove it was a matter vital to national defense. Almost everything in the way of public works, some people try to tie in with national defense. Now, I am trying to lay down a very strict rule that national defense means actually national defense, primarily munitions, and not things like highways.

“And oysters?” a reporter asked. “And oysters,” said the President.4

While they still had plenty of work to do, the Engineers were in a precarious position. A $133 million backlog of authorized projects and an unexpended balance of $380,258,000, which General Schley reported in mid-1940, were residue from better years. An appropriation of $172,800,000, approved on 24 June 1940, was for projects already on the books. Few, if any, new jobs were in sight. The

stream of civil projects was drying up. As the civil workload diminished, the Engineer Department would face drastic cuts in personnel—a prospect Schley viewed with serious apprehension. Because the Corps had too few Regulars to cope with its expanding military functions, he foresaw no difficulty in finding new assignments for surplus officers. But surplus employees would have to go. The civilian organization, the backbone of the Engineer Department, was in danger of being crippled.5

To make matters worse, the Engineers’ old adversaries were rallying again. Surrounding Hartman were veterans of the Construction Division of the Army, most of whom were still intensely loyal to their wartime outfit and its chief. Coldshouldered by Quartermaster Regulars, General “Puck” Marshall was nevertheless much in evidence, the center of a devoted group of oldtimers who wished to resurrect the separate construction corps of World War I. A brigadier general in the Reserve Corps, Marshall was a possible candidate for chief of an independent Construction Division. In the late spring of 1940 members of his group tried unsuccessfully to enlist the support of the Hogan committee. Overtures to Colonel Hartman were rebuffed. But with the return of Benedict Crowell to the War Department, the outlook changed. As one of Stimson’s closest advisers, Crowell was highly influential. The years had not dimmed his enthusiasm for a separate construction corps. Shortly after he assumed his new duties, the General Staff had before it a proposal for divorcing the Construction Division from the Quartermaster Corps. Construction appeared to be heading down the same road it had followed in World War 1—a road that led to trouble for the Corps of Engineers.6

General Schley had a battle on his hands to preserve his organization and forestall formation of a separate corps. It was a battle the Engineers could not afford to lose.

Growth of the Engineer Mission

On 10 June 1940 the newly formed Hogan committee made its initial report to the Army and Navy Munitions Board. Calling attention to the limited size of Hartman’s technical staff, the committee recommended that construction for the Ordnance Department be done by the Engineers. Otherwise, the committee revealed, half of the Corps’ 6,000 civilian engineers would face dismissal. The report continued: “We would further recommend that the Corps of Engineers be consulted in regard to their ability to undertake the preparation of additional plans and drawings. ..., rather than to attempt at this late date to organize a new and independent engineering force for the purpose as was done in the last war.”7 While the report was in preparation, Hogan and his colleagues solicited advice from the Engineers but had little contact with the Quartermaster Corps. The report produced no tangible results.8 Even so, the committee’s stand strengthened the Engineer position.

While the Hogan committee took the lead in advocating a change, General Schley limited his activities to missionary work. Visiting appointees to key posts in the new defense setup, he told them about his organization, its record and its capabilities. After one such interview, he reminded Knudsen: “I called on you a few days ago to give you a brief outline of the construction work which is normally done by the Corps of Engineers of the Army and to explain that the reduction in appropriations for that purpose in the current fiscal year makes it possible for us to take on some national defense construction not already undertaken by other agencies.”9 The delicacy of Schley’s position was illustrated by a story he later told. Among the men to whom he talked was Harrison. When, a short time after their conversation, the two men met by accident, Harrison asked Schley what he was trying to do—pressure him, Harrison, into giving Quartermaster construction to the Engineers. Schley answered that since the Engineers would fall within Harrison’s purview an explanation of their duties and potential had seemed in order.10

In his quest for additional projects, General Schley was sure to have strong support. The Engineers’ strength on Capitol Hill was a well-known fact. The preference of the Chief of Staff and Assistant Secretary Johnson for the Engineers was plainly apparent. What some failed to appreciate was the number of Engineer officers who held high-level posts in the War Department and the number of friends the Corps had within the industry. Since his appointment as Chief in 1937, General Schley had done his best to convince top military leaders that Engineer officers were “naturals for G-4” and other positions of broad responsibility. On 30 June 1940 six Engineer officers, including General Moore, were serving with the General Staff and seven, among them Colonel Schulz, were on duty with the Assistant Secretary. The Inspector General, Maj. Gen. Virgil L. Peterson, was also a member of the Corps. However impartial they wished to be, these men still tended to think as Engineers. As for the industry, one important segment, the heavy construction contractors, generally favored the Engineers. “The Corps, for several years, had been progressively doing more of its construction work by contract and less by hired labor,” Schley explained.11 Moreover, dissatisfaction among contractors with Seaman’s handling of the Panama and Alaska projects in 1939 and the coolness of many construction men toward “Puck” Marshall reacted in the Engineers’ favor.

If the Engineers had important allies, they also had determined opponents. Hartman was not one to give up a single project without a fight. Nor did he lack support. Chairman Morris Sheppard of the Senate Military Affairs Committee was in accord with the Quartermaster position and so were a number of other legislators. Two sizable groups within the industry—the building construction contractors and the American Society of Civil Engineers—were generally pro-Quartermaster. Moreover, proponents of a separate corps were certain to resist a transfer of defense work to Schley’s organization, for it would hurt their own chances of success.

During June and July the Engineers made slight gains. First, the Corps received approximately $10 million for fortifications. This money, which covered projects in the United States, Panama, and the Insular Departments, was to go primarily for seacoast defenses.12 Second, General DeWitt obtained permission to have Engineer troops build two landing fields in the Alaska panhandle. Earlier plans had contemplated construction of these airstrips by the Civil Aeronautics Authority.13 Third, General Schley persuaded Assistant Secretary Johnson to let the Corps build a plant at Cincinnati to produce metal mirrors for antiaircraft searchlights—an Engineer responsibility. The President allotted $520,000 for the purpose from the appropriation for expediting production. At Hartman’s insistence, the Quartermaster Corps maintained a measure of control. The Engineer officer in charge of the project was the CQM and reported to the Construction Division.14 These additions to the Engineer program, however welcome, were too small to be consequential.

Writing to Secretary Stimson on 23 July, Maj. Walter E. Lorence of OCE indicated that districts and divisions were feeling the pinch. The Civil Service Commission had recently classified all federal agencies as defense or nondefense. Those in the first category enjoyed important advantages: they could refuse to let their employees transfer to other government departments and they could draft employees of nondefense agencies. The Corps of Engineers fell within the second, nondefense, category. Protesting that many power and navigation projects and all fortifications work could “be properly described only as defense,” Lorence asked that the Engineers be reclassified. The Secretary’s office refused on the grounds that “the Engineer Department as a whole cannot be termed a national defense agency, particularly with reference to its river and harbor work.”15 While Schley’s organization seemed headed downhill, Hartman’s was coming up. Declining an offer of technical assistance from Interior Secretary Ickes, Stimson noted on 2 August: “The Quartermaster General has greatly augmented the engineering personnel of his department and expects to handle satisfactorily with his own force the routine design work involved.”16

Meanwhile, something was stirring in Congress. On 24 July, at hearings of the House Subcommittee on Military Appropriations, a significant exchange took place between Representative John Taber and General Gregory:–

Mr. Taber. Would you not be a good deal better off if you turned most of that construction of barracks and storehouses, and things of that sort, over to the Engineers?

General Gregory. I do not think so; no.

Mr. Taber. Give them that job.

General Gregory. We have a construction division which we feel is fully adequate to meet the current construction problems. It has been operating for the last 20 years very satisfactorily.17

Another member of the subcommittee, Representative Clarence Cannon, questioned whether the Quartermaster Corps could do the job as efficiently as the Corps of Engineers.18 Senator John E. Miller was also active in the Engineers’ behalf. On 5 August he announced that he would offer an amendment to a rivers and harbors authorization bill pending on the Senate calendar. The amendment would empower the Secretary to transfer any part of defense construction to the Engineers.19 Whether Miller had chosen the best bill for the purpose was questionable, the President’s attitude toward new rivers and harbors legislation being what it was. But the idea of an amendment was promising.

When Senator Miller’s amendment came to the War Department for comment. Secretary Stimson was out of town and General Marshall was acting in his stead. The Chief of Staff’s reaction to the proposal was entirely favorable. On 17 August, he wrote the Senate Committee on Commerce:–

The U.S. Army Engineer Corps has an existing, widely extended field organization, fully equipped, and highly trained and experienced in all types of construction work, which due to limitations contained in the National Defense Act of 1920, cannot be fully and expeditiously utilized under the present Defense Program. This amendment, if enacted, will ... make all of the established facilities of the Corps of Engineers immediately available for the expeditious and efficient prosecution of such work. Its passage will greatly facilitate the vigorous prosecution of the National Defense Program.

The Department accordingly recommends favorable consideration of the amendment.20

Although the future of both branches was involved, the Engineers knew of Marshall’s action; the Quartermaster Corps did not.21

Even before Marshall endorsed the amendment to the rivers and harbors bill, efforts were under way to attach the rider to another measure—the second supplemental defense appropriation for 1941. High on the President’s list of “must” legislation, the second supplemental had far better prospects than the controversial, slow-moving rivers and harbors bill. On 15 August, the day the Senate concluded hearings on the appropriation measure, Assistant Secretary Patterson asked Senator Miller to sponsor the amendment.22 Patterson later explained his reasons for supporting the rider:–

It was pointed out to me by General Schley ... that he had large forces, integrated organizations on river and harbor work, in the Corps of Engineers, and the work was drying up, there was not any more work coming out, and was he to disband these forces that had worked well together, a group of, say, 30 men, each of whom had his task in a going concern, and just scatter them to the winds and lose the benefits of years of contact and organization that they had, when the construction program of the Army needed exactly that organization, when we had none in the Quartermaster Corps comparable to the Corps of Engineers for the program that was right in front of us.23

It was Senator McKellar of the Appropriations Committee, rather than Senator Miller, who put forward the

proposal. On 19 August he notified the Senate that he would move to suspend the rules for the purpose of amending the appropriation bill as follows: “The Secretary of War may allocate to the Corps of Engineers any of the construction works required to carry out the national-defense program and may transfer to that agency the funds necessary for the execution of the works so allocated.”24 As one senator remarked, the proposed amendment was “slight in verbiage but rather important in consequence.”25

After reading McKellar’s proposal in the Congressional Record, Hartman went to Secretary Stimson, who was sympathetic but said his hands were tied. Stimson explained that in his absence Schley and Schulz had brought in a letter favoring the amendment and Patterson had signed it. With Hartman present, Stimson called the Assistant Secretary into his office and inquired why he had signed. Patterson replied that the two Engineer officers had “very forcibly presented the matter as one in the national defense,” and that inasmuch as he had been in office only two weeks, he “necessarily had to take the recommendations of senior officers such as General Schley, the Chief of Engineers, and Colonel Schulz, one of his own assistants.” Because Patterson had acted in good faith, Stimson was unwilling to ask that the amendment be stricken from the bill. But it was Hartman’s understanding that any steps taken by the Quartermaster Corps to kill the provision would meet with the Secretary’s approval.26

Hartman was at a disadvantage. For the first time, the AGC refused to take the Quartermaster’s side against the Engineers. At the September meeting of his executive committee, Managing Director Harding explained:–

On the question of the amendment to the last appropriation bill, the heat was terrible here. But I consulted with the President, Mr. Zachry, and we felt that there was only one course for us to follow and that was to be neutral. A great many of our members are doing work for the Army and a great many are doing work for the Engineer Corps. In addition to that, it was a family fight and we felt very definitely that it should be handled inside the Army. ... We knew that the Assistant Secretary of War, who is in charge of the construction program, and the Chief of Staff, General Marshall, were in sympathy with this legislation; that they had recommended to the Congress that this legislation be passed and, therefore, it would be very ungracious for us to tell them that they weren’t running the Army right.

Harding had received assurances that the Engineers would do the work by contract rather than by day labor.27 Unlike the general contractors, the specialty group opposed the amendment, but their protests came too late to affect the outcome.28 With no time to rally effective support, Hartman resorted to a stratagem. “Steps were taken,” he related, “to have the Senate change the wording of the bill in any manner possible so that it would be thrown into conference, at which time I hoped that we could present our side of the case and show the lack of need for such a law.”29

On 29 August, as the second supplemental moved toward a vote in the upper house, Senator McKellar offered the

amendment on behalf of the Appropriations Committee. Four words had been added to the text—the Engineers could be assigned construction work “in their usual line.” Little was said on the Senate floor. The only comment came from Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg, who called attention to the long-standing controversy between the construction services. “This is the first time that the Quartermaster Corps has lost,” he said, “and the first time the Corps of Engineers has won.” A routine question by Senator Wallace H. White, Jr., a reply by Senator McKellar, and that was all there was to it. The Senate agreed to the amendment.30

The House and Senate conferees met to consider the bill early in September. Reports reaching Hartman indicated that all but one of the conferees had agreed to eliminate the rider and that the Chief of Staff had then been called to testify.31 One of the conferees, Representative Clifton A. Woodrum of Virginia, summarized Marshall’s testimony:–

General Marshall very emphatically endorsed this provision. He pointed out the fact that it in no way was an effort to tread upon the prerogatives of the Quartermaster General, that the Quartermaster General of the Army customarily was geared up to do a construction total of about $10,000,000 a year, that under the defense program that figure had been skyrocketed to something like half a billion dollars, and that he did not have the set-up to do this work, whereas they had in many places over the country district engineers of the Army all set up and ready to go, especially qualified to do this work, and they could go right into the program immediately.32

Although Marshall made a deep impression, the issue remained in doubt. Reported in disagreement by the conference committee, the amendment still had to clear the House of Representatives.33

The final hurdle was quickly crossed. When the Joint Conference Committee reported the bill to the House on 5 September, Representative Woodrum suggested two changes in the amendment—that the new authority be limited to 30 June 1942 and that the phrase “in their usual line” be eliminated. In answer to objections against the rider, Woodrum emphasized that General Marshall had expressed his complete approval of the amendment when he appeared before the conferees. There were no further questions. The House approved the bill as amended, with the changes Woodrum had proposed, on 6 September 1940; the Senate agreed to the House version the following day; and on 9 September the President signed the bill.34

A week before this bill became law, the Destroyer-Base Agreement was signed at Washington. In exchange for fifty overage warships, Great Britain granted the United States the right to establish bases in the Bahamas, Trinidad, Jamaica, Antigua, St. Lucia, and British Guiana and, as a “gift” to the American people, added leaseholds in Newfoundland and Bermuda. Anticipating approval of the McKellar amendment, General Marshall on 6 September assigned construction at these bases to the Corps of Engineers. By the 25th Schley’s office had completed a rough estimate based on plans of the General Staff. The cost would be upwards of $200 million. An immediate allotment of $25 million from the President’s emergency fund enabled the

Engineers to make an early start. An order from Marshall that $175 million be made available before the end of the fiscal year for work in the British possessions indicated the urgency of the task.35

The Engineer program assumed new dimensions as the Corps received additional funds and fresh responsibilities. Under the supplemental defense appropriation acts of 9 September and 8 October 1940, the Engineers got $6.7 million for seacoast fortifications. The First Supplemental Civil Functions Appropriation Act for 1941, approved on 9 October 1940, carried some $13 million for navigation improvements, flood control work, and enlargement of the power plant at Bonneville Dam. This same act appropriated $40 million for airport construction by the Civil Aeronautics Authority. The Department of Commerce viewed this as the beginning of a large-scale effort which would cost $500 million and include 3, 100 airfields. By agreement between Secretary Jesse H. Jones and Secretary Stimson, the Engineer Department would perform extensive survey and construction work for CAA. An act of 17 October 1940 further enlarged the Engineers’ role in emergency construction by authorizing twenty-two new rivers and harbors projects in the interest of national defense. By early November the Corps was in line for yet another assignment—supervision of all WPA projects at military and civilian airfields.36

The Engineers had made impressive gains. They had a substantial program and more work was in prospect. Many of their new projects, civil as well as military, were vital to defense. The Civil Service Commission recognized the Corps as a defense agency and placed the Engineer Department and all of its employees in the protected category.37 But General Schley could not rest easy. He still had to contend with the faction that favored a separate construction corps.

A Separate Corps?

By September 1940 Benedict Crowell was deep in plans for reorganizing the War Department. Working with Arthur E. Palmer, a young attorney from Stimson’s law firm, he reviewed the existing setup in the light of his World War I experience. A strong assistant secretary, centralized control over all Army procurement, and close ties with industry were among his principal objectives. Describing Crowell’s plan for an independent Construction Division, another of Stimson’s assistants, John J. McCloy, said: “[He] felt that a separate agency should be set up ... and that it should not be exclusively under the direction of the Quartermaster General. ... He placed a great deal of stress on the use of officials from the construction industry and he did feel that civilian control of it was essential.”38 Crowell intended to re-establish the Construction Division of the Army and place it under Patterson.

While Crowell’s construction plan was taking shape, a fundamental weakness in the Quartermaster organization was

becoming apparent. As early as 19 September 1940 Maj. Sidney P. Simpson of Patterson’s staff had concluded that shortages of personnel, particularly of officers, lay at the root of Hartman’s difficulties. A study of the Construction Division had convinced Simpson that the organizational machinery was sound and that all would go well if only enough qualified men could be found to run it. But enough such men could not be found. Throughout the fall of 1940 Hartman had to struggle along with two to three hundred fewer officers than he needed.39 Moreover, numbers told an incomplete story, for, as Hartman pointed out, the Division had “to take any officer even with remote construction experience in order to get the jobs ... staffed.”40 The makeup of his civilian staff reflected this same expediency. The lack of qualified personnel was unquestionably Hartman’s crudest handicap.

Some of his critics failed to recognize this fact. Madigan and Harrison seemed to think that the crying need was for better management. They displayed growing impatience with Quartermaster systems of cost control, job planning, and progress reporting. When Hartman continually disregarded their advice, they came to view him as “a complete road block.”41 Hogan agreed with them. He attributed confusion in the program “to Hartman’s ignorance of the principles of delegation of authority. ..., his lack of judgment and vacillation under pressure.”42 This attitude was contagious. Unsatisfactory progress and rising costs were generally ascribed to bungling by the Quartermaster Corps. Stimson and Patterson became more and more concerned. After Armistice Day events moved rapidly toward a showdown.

On 12 November, in a confidential memorandum to Patterson, Major Simpson recommended removing the Construction Division from the Quartermaster Corps and placing it directly under the Assistant Secretary. An investigation of the division’s persistent shortage of officers had convinced Simpson that such a step was “basic to the effective carrying out of the construction program.” Under the existing arrangement, Hartman was unable to select and assign his own personnel. Moreover, Gregory’s insistence that “all papers to or from the Construction Division” be routed through his office was delaying orders for sorely needed officers. Before the personnel problem could be solved, Simpson believed the division would have to be freed from the “straight-jacket organizational set-up in the Quartermaster Corps.” Citing the precedent of World War I, he argued the necessity of “relieving what is fundamentally a civilian undertaking from the dead hand of orthodox military organization.” Having learned from Crowell that the Secretary’s office was studying a plan for a separate corps, Simpson suggested that Patterson sit back and await developments. The Assistant Secretary passed the memo on to Madigan for comment.43

News of Simpson’s proposal traveled fast and had immediate repercussions. Madigan lost no time in discussing the memorandum with Harrison and Hogan. All three agreed that something drastic ought to be done, but they were not yet ready to go as far as Simpson. They consulted General Burns who put them in touch with General Moore. After talking at length with the Deputy Chief of Staff, the three industry men took the position that construction was an Army “show” and ought to stay within the Army. A civilian corps would be “too commercial.” Nonetheless, if the Army fell down on the job, Crowell and Simpson were likely to have their way. Apprehensive, General Moore decided to take the initiative. On 13 November he and Reybold proposed that Marshall turn over airfield construction to the Engineers. Somewhat reluctantly, the Chief of Staff agreed.44 He later testified, “I questioned seriously the transfer of the Air Corps construction to the Engineer Corps in the middle of the program.” But, he continued, “I found myself compelled to accede to the recommendations of the principal staff officers concerned ... because we had had to quickly reduce the load on the Quartermaster Corps.”45 Moore viewed this as the first step. He believed it would also be necessary to replace Hartman and “to effect a complete reorganization.”46

Learning what was afoot, Gregory called a conference for Thursday, 14 November. Madigan, Harrison, Hogan, Reybold, Hartman, and Groves attended. “I gathered that they were preparing to remove Hartman and Gregory had demanded that he be faced with his critics,” Hogan afterward related. “Madigan and I had a little skull practice and decided to pull no punches.”47 Talk at the meeting was blunt and acrimonious. Opening the discussion with a plea for better management, Harrison stressed the need for a system of cost control. Hartman replied that such a system was already in operation. Harrison contradicted him and warned that unless a change took place the Construction Division would be unable to give an accounting of its funds. Madigan. Dismissing this criticism, Hartman had already lost track of progress and expenditures, he demanded that contractors submit progress schedules and cost estimates periodically during the course of their work. Reybold backed up Madigan. Dismissing this criticism, Hartman pointed out that his organization was “very much undermanned.” His statement got a cold reception.48 The discussion went on for several hours but produced no agreement. Hogan observed that Gregory “looked increasingly disheartened.”49

Meanwhile, General Moore was attempting to clear the way for transferring airfield construction to the Engineers. On the afternoon of the 14th he discussed the matter with Colonel Kennedy of the Air Corps Buildings and Grounds Division. Kennedy recommended against the transfer. Writing to Moore the

following day he explained his reasons:–

The construction under the Air Corps Expansion Program so far has gone forward without any delays that could have been avoided. ...

I am convinced that if, in the midst of this program, decision is made to take all of this construction work out from under The Quartermaster General and place it under the Corps of Engineers the amount of confusion that would accrue would result in chaos for weeks and fatal delay when these Air Corps new stations are so badly needed for early occupancy.

If a transfer took place, he wanted to confine it to projects not yet well underway. He also wanted assurance that jobs costing $ 1 million or more would be done by fixed-fee contract.50 Kennedy’s opposition was ineffective. On the 18th, after a second conference with Moore and Reybold, General Marshall ordered that construction at all Air Corps stations, except those in Panama, go over to the Engineers without delay. On 19 November Reybold issued the directive.51

That same day, Marshall held a conference in his office to discuss the Quartermaster construction effort. Among those present were Madigan, Harrison, Hogan, Moore, and Reybold. No Quartermaster officer attended. Madigan set the tone of the meeting. After expounding his ideas on estimates, schedules, and progress reports, he told the others, “Take it from one who came up from waterboy that you can’t reorganize a job by keeping the same superintendent.” Hogan, Moore, and Reybold joined in an indictment of Hartman. “Hartman does too much himself,” Hogan said. “Hartman takes no suggestions,” said Moore. “No planning in his office or in the field,” Reybold declared. Harrison had some words of appreciation. “Hartman and his six top men are faced with the hardest job in the Army,” he said. “They are getting a lot done and well done, but,” he agreed, “there could be great improvement.”52 Marshall asked each man, in turn, whether Hartman ought to go. All replied yes. The Chief of Staff rose, shook hands all around, and thanked each man for coming. Whether he intended to follow their advice, he did not say.53

Within a short time after this conference, an effort was under way to sidetrack Hartman. Whether because, as some believed, Marshall was reluctant to act or because, as others reported, Gregory fought stubbornly for Hartman, the strategy had changed. A search was on for a man who could go in as Deputy Chief of Construction and assume authority. Groves was Gregory’s choice for the deputy’s job, and Hartman agreed to take him.54 “It had been or was about to be announced that I was appointed as Deputy to Hartman,” Groves reminisced. “When I first joined the Construction Division on November 14th, I was designated Chief of the Fixed Fee Branch. A short time later I took over all operations and had already assumed many of the prerogatives of Deputy Chief.”55 This arrangement did not long

Colonel Somervell

continue. Speaking for himself and Harrison, Madigan explained, “We were not having any part of that Engineer major.”56

In Washington at the time, awaiting assignment to Camp Leonard Wood, was Lt. Col. Brehon B. Somervell, CE. A 1914 West Point graduate, Somervell had had a varied and somewhat unusual career. During World War I he served in France, first with the 15th Engineer Regiment and later with the 89th Division. After the Armistice he stayed on in Europe as G-4 of the Third Army. Returning to the United States in 1920 he took up the peacetime duties of an Engineer officer. His service during the next fifteen years included three tours in the Chiefs office and assignments to the New York, Memphis, and Washington Districts. During this same period he completed courses at the Engineer School, the Command and General Staff School, and the Army War College. Twice he received leaves of absence for special missions abroad. In 1925 he aided Walker D. Hines in a study of navigation on the Danube for the League of Nations. Eight years later he again assisted Hines, this time in an economic survey of Turkey. In 1935 he became district engineer at Ocala, Florida. There, in the course of work on the Florida Ship Canal, he met Harry Hopkins, with whom he formed a close association. In 1936 Somervell became WPA administrator in New York City. In four years with the relief agency he gained a reputation as an able executive and adroit politician. As his tour in New York drew to a close in the fall of 1940, he began casting about for a new assignment. He approached General Marshall about a field command and he also talked to General Moore. The results were disappointing. General Schley selected him to be executive officer of the new Engineer Training Center at Camp Wood, a responsible position but hardly what Somervell had in mind. One day in November over luncheon, Madigan told him about the Construction Division job. Somervell said he would “love” it. Madigan, who was familiar with WPA operations in New York City, believed he had found the right man.57

Plans for a separate corps were still very much alive. By 22 November a proposal for an independent, civilian-run Construction Division had reached

General Marshall. He took the matter up with General Moore.58 Recalling this interview, Moore commented:–

General Marshall called me into his office and told me verbally that it had been suggested that all construction work be placed in the hands of civilians. I replied vigorously that, in the past, it had been the civilian branches of the Government that had called upon the Army to help them in construction matters and cited the help given by Corps of Engineers officers in the Panama Canal and, more recently, the large operations of the WPA and other relief organizations. I thought the Army could do a better job than a civilian organization.59

There were others to be persuaded besides the Chief of Staff. The White House favored Crowell’s idea. Stimson believed that the construction “problem would only be solved by getting a man, be he a civilian or a soldier, who had the necessary drive to invigorate the program and bring it to fruition.”60 Madigan was in a position to influence the decision. According to his own account, he laid down the law to Moore. Either the military would do what Madigan thought necessary or he would come out “flat-footed” and state that the Army could not handle the job.61

On 28 November Somervell reported for temporary duty with General Peterson. His orders to Camp Wood were a dead letter and General Moore was attempting to arrange his transfer to the Construction Division. Gregory, Madigan recalled, was averse to taking him, considered him too aggressive; but others gave him enthusiastic backing. Hopkins had high praise for his work with WPA. Hogan, a personal friend, expressed confidence in his abilities. Harrison went along with Madigan and Hogan. Inquiries by members of Stimson’s staff disclosed that the 48-year-old lieutenant colonel had a reputation as a driver and a good administrator. Operating out of Peterson’s office, Somervell prepared for the Quartermaster assignment. He conferred with various persons familiar with Hartman’s difficulties and lined up Engineer officers to serve with him in the Construction Division. Between 30 November and 4 December he visited Chicago, St. Louis, Charlestown, Indiana, and Louisville, Kentucky, on a whirlwind tour of inspection. He presented his findings in a 14-page report criticizing the Quartermaster effort.62

Meanwhile Gregory, smarting from slaps at the Quartermaster Corps, had taken the situation in hand. In a series of quick moves, he tried to quiet the commotion. On 25 November he gave his deputy a list of complaints against the Construction Division and told him to take corrective action. That same day the first of a series of orders canceling old instructions and establishing new procedures went to the field. Within a short time persons sympathetic to the separate corps idea were being ousted from their posts. Quartermaster Regulars who had had no connection with the Construction Division of the Army replaced Lamphere, White, and Bennett. Decentralization was

the next step. Invoking the example of the Corps of Engineers, Gregory early in December ordered Hartman to set up regional offices similar to those that administered rivers and harbors projects. Convinced that centralized control of military construction was essential, Hartman refused. Gregory thereupon decided to relieve him. The decision, Gregory insisted, was his and his alone.63

Colonel Danielson was the logical man to succeed General Hartman. A Quartermaster officer since 1920, he was particularly well qualified to head the Construction Division. He was, by general agreement, one of the best engineers in the Army. With degrees from Iowa State College and MIT, he had a sound academic background. He was a recognized authority on utilities design and airport development; and he had served as chairman of the research committee of the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers. He knew from experience the workings of the Quartermaster organization and understood the problems that it faced. His assignments had included tours as CQM, post QM, corps area utilities officer, and branch chief in the central office. During the 1920s he had played a leading role in modernizing Army posts. In 1934 he had directed the $50 million emergency relief construction program. As CQM for Panama since 1939 his record was outstanding. From friends who were in Gregory’s office at the time, Danielson afterward learned that his name went on the bulletin board as Chief of Construction on Friday, 6 December. The following Monday the notice came down and Somervell’s name went up. Reportedly, the White House had called the turn.64

On Wednesday, 11 December, the change in command took place. Recalling the event, General Hartman wrote:– “General Gregory came into my office early in the afternoon of December 11th and I knew by the scared look on his face that he had bad news for me. He informed me that I was relieved from the Construction Division at once. I did not give him the courtesy of a reply. I immediately closed my desk and departed.”65 As Hartman left by one door, Somervell came in the other. That day Secretary Stimson wrote in his diary:–

Another crisis has come up in the Department. General Hartman, who has had charge of construction in the Quartermaster Corps, is being relieved and Lt. Col. Somervell is being placed in his place. It is a pathetic situation because Hartman has been a loyal and devoted man. He has conducted the difficult and delicate work of choosing these contractors in these bids on numerous projects without a taint of scandal of any sort thus far. But he apparently lacks the gift of organization and he has been running behind in the work. Accordingly, General Marshall came in this morning to tell me that it was his advice that this change should be made and I gave my approval to it as a matter of course, for I knew very well that Marshall has given careful and fair consideration of it and felt just as kindly towards Hartman as I did. But it makes another problem to be handled at the coming Press conference.66

At Stimson’s weekly news conference

on 12 December, the “ticklish” question of

Hartman’s relief did not arise.67 War Department press release dated 13 December announced Somervell’s appointment. The release disclosed that Hartman had entered Walter Reed Hospital “for observation and treatment following a long period of overwork” and stated “that the delays in certain of the construction projects ... had no bearing on the assignment of Colonel Somervell; that these delays had been due to causes beyond the control of the Construction Division.”68 At his next press conference, Stimson introduced Somervell to the reporters and made a statement “designed to protect poor old Hartman, who has been as faithful as could be and has broken down under the task, from being unjustly criticized.”69 Press reaction was mixed. “All the dead generals were not sleeping under statues last week,” began an item in Time, which lambasted Stimson and “the bumbling quartermasters.”70 Publishing an interview with William F. Carey of Harrison’s staff, the New York Times presented a different picture. “The Lord Himself could not meet the construction timetables and cost estimates first set for the camps,” it quoted Carey. “It was a literal impossibility to finish the work in the time originally set. I don’t know who made out the original time and cost estimates, but whoever did was expecting the impossible.”71 Hartman’s long career in construction was over. Admitted to Walter Reed on 11 December, he remained on sick leave until April 1941, when he took command of the Quartermaster Replacement Center at Fort Lee. He served at Lee until March 1942, when he suffered a near-fatal heart attack brought on, friends believed, by grief over his removal as Chief of Construction. On 30 April 1943 General Hartman retired on disability after 39 years’ service. Five years before his death in 1962 he stated: “I have no apologies, and if I had it to do over I would do the same thing again.”72

Reorganization and Restaffing

Two days before his appointment, Somervell outlined plans for overhauling the construction setup. Writing to Gregory on 9 December, he recommended drastic changes: reorganize the Construction Division, reduce the number of branches, and create several new sections; strengthen the field, establish regional offices, and decentralize authority “to the maximum extent possible”; and review the qualifications of construction personnel and replace incompetents with top-flight engineers and executives.73 Left free to make these changes, Somervell promised to get results.

The new chief was in a far stronger position than Hartman had been. It was rumored at the time of his appointment that he had demanded and got a blank check from Gregory. McCloy in Stimson’s office thought he had “full and independent powers.”74 Major Thomas

in the field sensed that Somervell, “a much bigger fish” than Hartman, had taken over the construction duties of The Quartermaster General.75 Questioned about this later, General Gregory said:–

My policy has always been if anybody is placed in charge of a job, let him do it. I don’t try to run it for them. So if he was put in charge of Construction Division, he was in charge of Construction Division, although I expected if anything went wrong and I said to correct it, I wanted it corrected. As far as his demanding anything like that [a blank check], I don’t think that is true.

Somervell hardly needed a carte blanche agreement, such was the high-level support he could count on. He had, as Gregory put it, “a pipeline to General Marshall” and could “go around Moore and Reybold and get what he wanted.”76 He enjoyed Stimson’s admiration and respect. Most important, he had the confidence of Hopkins and the President. The door to the White House was always open to him and those with whom he dealt were not likely to forget it.77 Somervell knew what he wanted in the way of an organization. He favored a type of setup known as line and staff and characterized by a high degree of decentralization, a minimum number of bosses, and a sharp distinction between those who gave orders and those who advised. Applied to the Quartermaster structure, line and staff principles suggested three levels of authority—Construction Division, regional offices, and project offices. The Chief of Construction would issue orders to his regional representatives, who would, in turn, direct the Constructing Quartermasters. At each level of authority, the responsible officer would have his own advisers. Policy matters would be decided in Washington; local problems would be settled on the spot. Up-to-date management methods and good public relations completed Somervell’s organizational formula.78

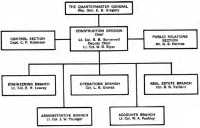

On 16 December 1940, his fifth day in office, Somervell reorganized the Construction Division. (Chart 6) He reduced Hartman’s eleven branches to five—Administrative, Accounts, Engineering, Operations, and Real Estate. Administrative absorbed personnel functions which had been in the Executive Office. Accounts took in the former Funds and Estimates and Accounting and Auditing Branches. Engineering annexed the Liaison and Legal Branches and contracting groups from other sections of the office. Operations incorporated the former Fixed Fee, Lump Sum, Procurement and Expediting, and Repairs and Utilities Branches. Of all Hartman’s branches, only Real Estate remained unchanged. Somervell added two new sections to the Executive Office; the first, Control, was to be a management unit, preparing statistics and reports and coordinating the work of the various branches; the second, Public Relations, was to place the construction story before the public.79 Details of the new organization were left for later. Further changes would take place after the branch chiefs had conferred. With the program at a

Chart 6: Organization of Construction Division, OQMG, 16 December 1940

Source: Incl with OQMG, Office Order 137, 14 Dec 40, Opns Br Files, Orgn and Consolidation.

Colonel Leave, Major Robinson, and Colonel Styer

critical stage, Somervell believed “the reorganization should be one of evolution rather than revolution.” From his office came the reminder: “The Construction Division is a going concern in the midst of a huge program. Our efforts should strive to help this living organization run more efficiently, more smoothly with a bit more speed.”80

Of the old branch chiefs, only two retained their positions. Groves headed Operations and Valliant continued as chief of Real Estate. Other top posts went to newcomers. Lt. Col. James W. Younger, QMC, recently of the Assistant Secretary’s office, took over the Administrative Branch. Lt. Col. Walter A. Pashley, QMC, holder of a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Harvard University, became head of the Accounts Branch. Engineering went to Lt. Col. Edmond H. Leavey, CE, former deputy administrator of the New York City WPA, Control, to Capt. Clinton F. Robinson, CE, another alumnus of the New York City relief agency. The public relations assignment fell to George S. Holmes, veteran newspaperman and former Washington correspondent for the Scripps-Howard chain. As his deputy and executive officer, Somervell chose an old friend and fellow Engineer officer, Lt. Col. Wilhelm D. Styer. Most of these men were relatively young and promising. Except for Holmes and Valliant, none had reached his forty-eighth birthday. Younger later rose to be a brigadier general; Leavey and Robinson, to be major generals; Styer and Groves, to be lieutenant generals. Significantly, Somervell’s staff included four Engineer officers. This group began almost at once to transform the Construction Division. Branch chiefs soon were busy with plans for internal reorganization and before long were shifting units from one office to another, seeking additional space, and studying personnel requirements. On 20 December Somervell inaugurated a series of weekly staff conferences. A short time later Holmes issued his first press release.

By the end of the month Robinson was ready to begin publishing a weekly progress report.81 Meanwhile, the new Chief of Construction pushed on toward his next objective, establishment of regional offices.

Within a week of Somervell’s coming, rumors of impending change had begun to circulate. The press carried reports that building work would soon go to the corps areas. Old construction hands came forward with advice and encouragement. On 17 December Somervell acknowledged that he wished to make a change but said that details were still uncertain. Behind the scenes he worked to clear the way for territorial zones. He instructed Styer to draft an order setting forth the authority and responsibilities of the zones. He told Younger to decide whether the new offices should be established by law, Army Regulation, or official instructions. He asked Groves to recommend men who could serve as Zone Constructing Quartermasters.82 By Christmas, all was in readiness.

A War Department Circular of 30 December 1940 established nine territorial construction zones having the same boundaries and headquarters as the nine corps areas. (Map 2) Heading each zone would be a Zone Constructing Quartermaster (ZCQM), responsible to The Quartermaster General. The zone offices would be miniature Construction Divisions, doing much of the work previously done in Washington. The ZCQM would supervise and control all CQMs within his territory; make frequent inspections of projects; award advertised contracts for $500,000 or less without consulting Washington; represent The Quartermaster General in dealing with respective corps area commanders; and, in fact, relieve the chief of the Construction Division of “any problems which are susceptible of proper solution locally.”83 Somervell called the zones the “backbone” of his organization. “The Zone Quartermasters must function,” he told his staff. “If they don’t, we won’t.”84 Nevertheless, Somervell, like Hartman, recognized the need for strong centralized control over design, contract negotiations, and other advisory and directive functions. Such functions remained in his own office.

The nine newly appointed zone constructing quartermasters who reported to General Gregory early in January had been singled out by Groves as the best men available. Three came from CQM and Vicinity offices, the archetypes, if such there were, of the zones. Five came from important projects, where they had made excellent records as CQMs. All were Quartermaster Regulars and career construction officers. When the group had assembled, Gregory announced their assignments. Maj. Ralph G. Richards would head the First Zone; Lt. Col. Murdock A. McFadden, the Second; Maj. Joseph H. Burgheim, the Third; Col. Henry L. Green, the Fourth; Maj. Benjamin F. Vandervoort, the Fifth; and Capt. Everett C. Hayden, the Sixth. Maj. Morton E. Townes, Lt. Col. Edwin

Map 2: Quartermaster Construction Zones

V. Dunstan, and Lt. Col. Edward M. George were named to Zones Seven, Eight, and Nine, respectively. After three days of conferences, the Zone Constructing Quartermasters left to take up their duties in the field.85

Aware that no organization, however streamlined, was better than the men who composed it, Somervell gave considerable thought to personnel. He set exacting standards. His subordinate officers would have to be aggressive leaders, capable of hard work and sound judgment; his civilian advisers, eminent professionals, top men in their fields. His staff would include “operators” with important industrial connections.86 Somervell put a premium on youth and drive. Given “an enthusiastic younger man” and “an older, more experienced person who has lost some of his steam,” he generally preferred the former.87 Gogetters, crack executives, and prominent consultants—these were the men who would henceforth run the program. Anyone who failed to measure up would have to go. Once convinced that a man was unsuited for his job, Somervell intended to act fast. “I will not talk. ...,” he told Reybold. “I will just move.”88

A personnel shakeup accompanied the reorganization. Key members of Hartman’s team received less important posts. Birdseye became Styer’s assistant; Nurse, Leavey’s executive. Men like Bayer and Leisenring, who had been prominent in the division’s affairs, found themselves in the background. Others resigned or transferred out. Koke left in mid-December, following a disagreement with Somervell over auditing procedures.89 Violante was relieved at his own request early in January, after informing Somervell that he “was not in tune with his administration.”90 Some twenty Constructing Quartermasters were ousted from their projects. Scores of lesser figures were struck down by what some called the “Somervell blitz.” Yet the number affected was comparatively small; a majority of Hartman’s people continued in their jobs. “That we have not had more poor ones, I think, is a question of luck, to a considerable extent,” Somervell commented, “and also the good judgment of the people who picked them out.”91

The need for more officers sparked a recruiting drive. The search led naturally to the Corps of Engineers. Two days after Christmas, Styer asked the Chief’s office for the loan of several Regulars, but the Engineers, also short of officers, refused. “This source of supply,” Styer concluded, “cannot be considered at the present time.”92 Somervell was not so easily discouraged. At his prompting, Gregory on 30 December appealed to Schley for three officers to fill key positions in the Construction Division. Gregory’s letter, reinforced by an appeal from Somervell to Marshall, turned the trick. Early in January two Engineers, Maj. Hugh J. Casey and Capt. Edmund K. Daley, joined Colonel Leavey, and a third, Capt. Garrison H. Davidson, joined Colonel

Groves. Schley made the loan on one condition—Gregory had to agree to release the three officers in June.93

The hunt fanned out in many directions. Gregory asked The Surgeon General and the Chief of Ordnance to lend officers who could help design hospitals and industrial plants. Somervell requested twenty West Point graduates of the class of 1941. Styer meanwhile tried to borrow officers from other divisions in Gregory’s office. A search of Retired and Reserve lists yielded many good possibilities. Members of the Construction Division were constantly on the lookout for prospects. A chance meeting with an old acquaintance or a letter from a fellow officer was often enough to start negotiations. While some of these schemes came to naught, others bore fruit. The list of officers on construction duty grew steadily longer. Many of the men Somervell brought in did excellent work; most, though by no means all, proved competent.94

Somervell set out to acquire a staff of outstanding civilians and in this he succeeded. The list of prominent men who came to work for the Construction Division read like a roster of “who’s who” in engineering and allied professions. Alonzo J. Hammond, president of the American Engineering Council, joined the Construction Advisory Committee. Henry A. Stix, vice president and comptroller of the Associated Gas and Electric Company, agreed to manage the division’s finances. Among those who accepted full-time employment with the Engineering Branch were George E. Bergstrom, president of the American Institute of Architects; Frederick H. Fowler, president of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Warren H. McBryde, past president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers; Albert D. Taylor, president of the American Society of Landscape Architects; and Leonard C. Urquhart, professor of structural engineering at Cornell. Discussing these appointments, Groves wrote:–

The reason for selecting these prominent men was not so much for the expected accomplishments, but rather to have a group in whom the professional men and professional societies, as well as the public, would have full confidence. Somervell hoped, and his hopes were fulfilled, that this would improve the public attitude toward the Construction Division.95

Besides the distinguished men who became regular employees, there were some who agreed to act as consultants. Rudolph W. Van Norden and Malcolm Pirnie, both well-known engineers, put their knowledge and experience at Somervell’s disposal. Richmond H. Shreve, whose firm, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, had designed the Empire State and other large buildings, advised on architectural matters. Among others who served on a part-time basis were Earnest Boyce, professor of sanitary engineering at the University of Kansas; John G. Eadie, member of Eadie, Freund and Campbell, consulting engineers of New York City; George B. Hills, an authority on the design of docks and terminals; Alfred L. Jaros, an expert on installation of mechanical equipment; and Charles R. Velzy, works superintendent of the

Buffalo Sewer Authority. Engineers, architects, professors, and attorneys received anywhere from $17 to $100 per day plus expenses as consultants. By mid-1941 about two dozen were on the rolls.96

Hardly less notable than Somervell’s own advisers were those of the Zone Constructing Quartermasters. Early in February each of the regional offices had an engineer, an architect, and a construction man—every one of them a leader in his field. Some, such as C. Herrick Hammond, past president of the American Institute of Architects, and Edward T. Foley, a director of the internationally known firm of Foley Brothers, Inc., had reached the pinnacle of their professions. Of the twenty-seven new officials, two came out of retirement; the rest left high-salaried positions, flourishing practices, and successful businesses to take jobs with the Quartermaster Corps. Their appointments climaxed a month-long drive by the ANMB Advisory Committee, the American Society of Civil Engineers, and the Associated General Contractors to sign up men for the zone offices.97

In his first months as Chief of Construction Somervell had made substantial progress toward a stronger organization. Nevertheless he still had some distance to go before the reorganized central office and the newly established zones were fully staffed and running smoothly.

Transfer of Air Corps Construction

The transfer of Air Corps construction in November 1940 lifted a sizable burden from the shoulders of The Quartermaster General. By 30 March 1941, eighty-one Air Corps projects with a total estimated cost of $200 million had gone over to the Corps of Engineers. In January, at General DeWitt’s urging, the Engineers assumed responsibility for all construction in Alaska, ground as well as air. Except for real estate and maintenance activities, the Engineers took over all work in connection with their new projects.98 While longtime Quartermaster construction officers deplored the loss of the airfields, Groves thought the change was advantageous. Some years later he recalled:–

I did not consider it unfortunate for the Quartermaster Corps at the time and I don’t believe that General Gregory did either. Actually, I believed it was beneficial, as it reduced. ...[the Quartermaster Corps’ ] overwhelming responsibilities. It also eliminated the difficulties encountered in dealing with the Buildings and Grounds Division of the Air Corps. This division always wished to interfere excessively in the details of construction.99

With the shift in responsibility, direction of the Air Corps program devolved on Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Robins, Assistant Chief of Engineers. A man of mature ability and quiet manner, Robins had behind him thirty-six years as an Engineer officer. Since 1939 he had headed the Civil Works Division, OCE, which oversaw all Engineer construction except fortifications. In the fall of 1940 Robins’ organization consisted of four principal sections: Engineering, under William H. McAlpine; Finance and

General Robins

Accounting, under Lt. Col. Earl E. Gesler; Miscellaneous Civil, under Maj. Mark M. Boatner, Jr.; and Construction, under Maj. John R. Hardin. Lt. Col. William F. Tompkins was Robins’ executive assistant. (Chart 7) A graduate of MIT, “Mr. Mac” McAlpine had been with the Engineers since 1902. Robins’ officers, like their chief, were all West Point graduates who had spent their entire careers in the Corps, and most held additional degrees from top civilian engineering schools. Upon the assignment of emergency construction to his office, Robins made certain changes. He dropped the Civil Works designation. He set up a National Defense Projects Branch in the Construction Section and named Maj. Ewart G. Plank to head it. He appointed Maj. Henry F. Hannis liaison officer with the Air Corps. Both Plank and Hannis were West Pointers and both were graduates of Rensselaer Poly. In keeping with the Engineers’ policy of decentralization, Robins and his assistants concerned themselves largely with matters of policy and administration, leaving the main work of supervising and executing construction to the districts and divisions.

In a letter to the Chief of the Air Corps on 4 December 1940, Colonel Tompkins described the Engineer Department and the way it operated. Covering the entire continental United States and the insular possessions, the department consisted of twelve divisions and fifty districts. The divisions conformed geographically to major river basins; the districts to smaller natural watersheds. In contrast with the Quartermaster field, Engineer field officers had considerable authority. District and division engineers issued specifications for jobs costing up to $10,000 and $50,000, respectively. Districts advertised contracts amounting up to $50,000; divisions, contracts in any amount. “These Districts and Divisions,” Tompkins wrote, “function as closely knit but self-contained units, all responsible successively to a single administrative authority, namely the Chief of Engineers.” Terming decentralization “a great feature in the strength of our organization,” Tompkins looked forward to effective cooperation between Engineer field officers and Air Corps station and area commanders.100

During the last week in November Tompkins met with Nurse to block out procedures for expediting the transfer. The two men established a system of priorities. Projects not yet started they labeled Priority One—to be transferred almost immediately. Projects involving

Chart 7 Organization of Office of Assistant Chief of Engineers, December 1940

permanent structures went into Priority Two—to be transferred within two weeks. Projects involving temporary construction already under contract but not well advanced received Priority Three. Projects involving temporary construction and those nearing completion were in Priority Four—last and least likely to be transferred. A partial listing made on 2 December showed 14 jobs in the first priority, 35 in the second, 8 in the third, and 11 in the fourth. Tompkins set a target date of 1 January 1941 for completing the operation. Nurse agreed to try to meet this deadline.101 On 30 November he instructed the CQMs concerned to work out details of the transfer with local Engineer districts. Urging full cooperation, Nurse directed:–

You will extend to the officer representing the Corps of Engineers every courtesy and will acquaint him fully with the details of the project concerned and give him every aid in establishing himself and acquiring responsibility for his new duties. Until such time as the transfer is effected you will vigorously prosecute all work under your jurisdiction and there will be no slowing or slacking up of the work.102

District engineers began almost at once to prepare for the changeover, surveying projects and setting dates for transferring them.103

A difficult problem remained. By late 1940 General Schley was critically short of officers. Increases in Engineer troops, burgeoning demands for Engineers on general staffs and in training centers, and details of Engineers to other activities had strained the Corps’ commissioned strength to the limit. In early December only 61 officers were on river and harbor duty, though a minimum of 124 was needed. Schley would need an additional 120 for the Air Corps projects, and these he hoped to get through the transfer. Although Gregory readily agreed to reassign civilian employees along with the projects they were working on, he was reluctant to release sorely needed officers. When Schley, in an initial request, asked for twelve Reservists—five Engineers, two Quartermasters, and five from other branches, Gregory turned over the Engineer Reservists but refused to give up the rest. It became his policy not to transfer officers. There seemed to be but one course Schley could follow. On 23 December he directed the division engineers to look for qualified Reservists, able and willing to serve with the Corps. By summer, 1941, more than 150 Reserve officers were on active duty with the Engineer construction program.104

Beginning, on 27 November 1940, with the air base at Manchester, New Hampshire, Air Corps projects passed rapidly to Engineer control. By the end of the year, 53 had changed hands. Twenty more made the transition in January, one in February, and 7 in March. Along with these projects, Gregory turned over to the Engineers some 200 construction contracts and approximately $80 million. Roughly 20 jobs, some primarily housing

projects and most near completion, continued under the Quartermaster Corps. By 1 April 1941 the transfer was over and done with.105

During and after the changeover, the Corps of Engineers and the Quartermaster Corps maintained close liaison. Somervell placed the facilities of his office at General Robins’ disposal. Sheafs of Quartermaster circulars, manuals, reports, and standard drawings and specifications went to OCE for distribution to the field. Colonel Leavey’s staff continued work on plans and layouts for Air Corps stations until May 1941, when the Engineers were able to dispense with this help. The Construction Advisory Committee opened its files to the Engineers and, upon request, recommended contractors for Air Corps projects. To simplify real estate transactions, General Gregory in the spring of 1941 delegated his responsibility for negotiating leases and acquiring land at air bases to General Schley. Successful cooperation between the two Corps enabled construction to go forward without disruption or delay.106 This cooperation was due largely to the example set by Schley and Gregory. As Groves observed: “It was not so hard for Schley to be cooperative, as he was on the receiving end. Many men in Gregory’s position would have been inclined to wash their hands of it all.”107

During the winter of 1940–41 the Air Corps program expanded, as directives came out for sixteen big new projects and for dozens of additions to going ones.

Table 11: Cost of Air Corps Projects

| Projects by Type | Estimated Cost |

| Total | $286,674,000 |

| Tactical stations | $155,913,000 |

| Pilot schools | 26,612,000 |

| Technical schools | 28,577,000 |

| Air Corps depots | 31,572,000 |

| Experimental depots | 6,800,000 |

| Aircraft assembly plants | 37,200,000 |

Source: Ltr, OCE to BOB, 28 Mar 41. 686 (Airfields) Part 9.

Largest of the new projects were four aircraft assembly plants authorized by the President in December and January. Designed to produce light and heavy bombers, these plants were to be at Fort Crook, Nebraska; Kansas City, Kansas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Fort Worth, Texas. Next in size were eight pilot training schools to be in the South and Southwest. Three stations for General Headquarters, Air Force, and one for observation units completed the list.108 By 1 April Air Corps projects under Engineer direction had a total estimated cost of $286,674,000.109(Table II) Together with the Atlantic bases, these Air Corps projects represented almost one-third of the Army’s construction program—from a monetary standpoint. But, as Groves emphasized, owing to the simpler nature of airfield work, the Engineer program presented nothing “like a third of the difficulties.”110

On 1 April 1941 General Marshall reported to Stimson that the transfer had gone “smoothly.” “The construction projects which have been allocated to the Corps of Engineers,” he went on to say, “are being actively and efficiently prosecuted and are generally meeting the requirement dates. ... The spread of the work between the two organizations is resulting in closer supervision in Washington and more expert direction on the job by both agencies.”111 But while Marshall considered the arrangement practical, he could not regard it as final. Unless Congress acted beforehand, airfield construction would revert to the Quartermaster Corps on 1 July 1942.