Chapter 8: Completing the Camps

When Somervell succeeded Hartman in December 1940, he faced a stiff ordeal. Eight National Guard divisions and some eighty miscellaneous units were due for induction during January and February 1941. Five general hospitals were to open on 1 March. Twenty-one replacement training centers were to begin operation around 15 March. In all, more than sixty projects were due for completion before April 1941.1 This construction had to be accomplished on limited budgets, in the face of continuing shortages and changing requirements, and at a season of the year when outdoor building work throughout most of the country was normally suspended. War was moving closer. The situation did not permit further delay in getting troops into training.

The Deficit Problem

During December the question arose in the War Department whether economy or speed should govern construction. The growing construction deficit—$100 million on 2 December, $140 million five days later—was a source of official embarrassment. Huge amounts were owing to contractors and materialmen. Money to keep the program going would be hard to find. Large additional appropriations would be necessary, how large no one knew. Nor could anyone be certain how Congress and the public would react. Marshall, Stimson, and Roosevelt were frankly concerned. The situation gave rise to various proposals for saving money, including some for slowing construction.

On 7 December, General Reybold suggested a common-sense approach to the problem of the deficit. Referring to the high cost of labor and materials and the inaccuracy of original estimates, he wrote to the Chief of Staff:–

The requirements for housing and caring for our large Army are considered generally modest. ... It is not believed that these requirements may be decreased in order to reduce the deficit, nor will the world situation permit a slowing of the program to reduce cost or a delay to obtain more funds. It is believed that the program based on authorized requirements must proceed to a rapid conclusion irrespective of the deficit caused thereby. G-4 does believe, however, that every effort should be made, short of reduction of requirements and delay in the program, to prevent this deficiency from becoming of undefendable size.

Reybold went on to outline a course of action. First, he would ask the President for permission to incur a deficit of $150 million; second, he would ask General Gregory to prevent the overrun from becoming any larger; and third, he would ask the using services to save construction funds by requesting only bare necessities,

by using WPA, and by reviving “the American Army principle of extemporizing facilities in the field.” General Marshall agreed to try the plan.2

Two days before he presented this proposal, Reybold agreed to a new schedule for housing the National Guard. Since late November he had been debating camp completion dates with Col. Harry L. Twaddle, the new Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3. By 1 December, the two men had agreed on induction dates for all Guard units except those slated for Indiantown Gap, Forrest, and Wood. In Reybold’s opinion the first of these three camps could not be finished until February, the others not until April. Twaddle insisted that all be ready in January. The two men settled their differences on 5 December. Next day they issued a new timetable: Camp Robinson in December; Camps Edwards, Claiborne, Shelby, and San Luis Obispo in January; and Camps Forrest, Meade, Blanding, and Indiantown Gap in February. With the exception of Camp Leonard Wood, now listed for 1 April, the remaining projects in the original Guard program would be ready by the end of January.3 Committed to the new schedule, Reybold wrote to Gregory, “It is vitally important that the accommodations be completed on the dates specified.”4

The postponement of induction dates led Inspector General Peterson to demand stricter economy. Unnecessary haste, he maintained, was costing the Army millions. Reports from his inspectors indicated that attempts to rush completion had inspired reckless spending. Overtime, duplicate purchases, and “other costly procedures” were prevalent. Peterson proposed to put a stop to all this. Soon after learning of the new induction schedule, he wrote General Marshall, “This postponement ... materially increases the time available for completion of the various construction projects ... and, in my opinion, should permit their completion in an orderly and economical manner.” He went on to suggest that General Gregory be ordered to “eliminate all unnecessary expenditures.”5

Peterson became the proponent of a new scheme for saving money. Twaddle had recently recommended that Guard units inducted after mid-February remain at peace strength until June. Selectees earmarked for these units would not go directly to the Guard camps as originally intended, but instead would receive thirteen weeks of basic training at replacement training centers before joining the Guardsmen. This plan, if approved by the Chief of Staff, would affect three divisions and a number of separate regiments slated for Blanding, Dix, Indiantown Gap, Forrest, and Wood. While Marshall deliberated, Peterson discovered that these projects were working overtime in an effort to complete by March accommodations which, under Twaddle’s plan, would not be fully occupied until June. The replacement training centers were also going full speed. The Inspector General warned Marshall that using expensive methods to complete buildings

which would stand vacant for several months could “only result in just and unfavorable criticism of the War Department.” Anticipating Marshall’s approval of Twaddle’s proposal, Peterson recommended that The Quartermaster General wait until spring to house selectees at Guard camps.6

G-4 considered Peterson’s plan ill-advised. Acting in Reybold’s absence, Colonel Chamberlin commented on the scheme. To postpone construction for selectees, Chamberlin maintained, the Army would have to follow one of two courses. First, it could ask each contractor to complete a section of his camp large enough to house the peace-strength units. Guardsmen would take over the finished sections, with pairs of half-strength units occupying quarters intended eventually for single units at full strength. Then the contractor would complete the camp. When selectees arrived, each unit would jump to full strength and move to its permanent area. Second, the Army could ask a contractor to build throughout an entire camp, leaving out every other barracks, omitting parts of the hospital, and in general completing enough of the camp to enable peace-strength units to move into their permanent areas. Later on, the contractor could retrace his steps, putting in the buildings he had skipped before. Chamberlin opposed both courses. He said of the first: “This method would entirely defeat the principle of mobilization. Each unit when it comes in should be put in its own area so that it can organize that area ... to receive the additional men in orderly fashion”; and of the second: “Since the area would have to be gone back over again it would probably cost more than the payment of overtime to complete the entire facility at one time.”7

Colonel Groves, who carried major responsibility for the camp projects, was also against Peterson’s proposal. He had already adopted some of the suggested methods to save time but doubted they could save money. Groves shared with civilian engineers the opinion “that it costs more money to bring troops into your camp before the camp is completed.”8 Moreover, he contended, since premium pay was necessary to hold labor at defense jobs, any attempt to reduce costs by cutting overtime would deprive the projects of essential workers and thus delay construction for peace-strength units as well as for selectees.9 General Moore soon joined Groves in opposing the Inspector’s plan.

On 19 December, in a memorandum for Marshall, Moore attacked Peterson’s position, warning that the Army must focus on its objective—“the mobilization and training of our troops in the least practicable time.” Noting that Congress had appropriated almost one billion dollars for expediting production of munitions and airplanes, he stated:–

Under such circumstances I think we are justified in incurring additional expense in “expediting production” of shelter for troops in spite of “hell and high water” (particularly the latter), so that we may have a trained force ready at the earliest practicable date. …

Although we may be subject to some

economy minded criticism for pushing construction at additional expense under adverse winter conditions, we would be subject to more justified criticism if we permit “logistical” financial considerations to govern under the present situation.

Besides, he said, carrying out Peterson’s plan would be difficult if not impossible. Agreeing with his deputy, Marshall penciled “O.K., GCM” on Moore’s memorandum.10

Although Peterson’s scheme fell through, it did serve to underline the necessity for thrift. On 20 December Somervell asked camp CQMs to justify their use of crash methods.11 A short time later he felt called upon to defend continued use of overtime at Indiantown Gap. “It will not be possible,” he told Reybold, “to stop working overtime at present without seriously jeopardizing the work.”12 Hard pressed for funds, Somervell endorsed every means of reducing expenditures short of slowing inductions. He encouraged contractors to cut payrolls and to hold construction to essentials. He cut out unnecessary overtime. He substituted gravel roads for concrete and asphalt. He eliminated tie rods, exterior paint, floor seals, and skirting from building plans. He postponed landscaping and fine grading. He denied requests for additional buildings.13 In January he warned his branch chiefs:– “Nothing aside from crookedness will subject this office to criticism as will exorbitant costs. Dementia dollaritis must be stamped out.”14 As long as the big construction deficit remained, this attitude would prevail.

Additional Funds

Wiping out the deficit was high on Somervell’s agenda. When he took over the Construction Division, the known deficit stood at about $150 million. This figure he suspected was too low. “I do not believe they can finish the camps for that,” he told Reybold. “I am just a little worried about it. ... I do not want to embarrass you and the Secretary by running up and saying we need more million dollars.”15 On 13 December he told architect-engineers to re-estimate, this time correctly, the final costs of their projects. The result was startling. The new estimates indicated that approximately $337 million would be necessary to complete the program. Somervell added $25 million for contingencies, putting the total deficit at $362 million.16 Having decided how much to ask, he prepared to make a strong bid for early passage of a deficiency appropriation.

On 3 January he presented the bill to the Chief of Staff. Marshall was perturbed. The Secretary, he explained, had understood that the deficit would be $150 million. “If he had that impression,” said Somervell, “he was wrong. We can’t build for any less than this sum. These estimates cannot be pared.” Marshall interjected, “I understand that. What I want to do is to get the matter straight before the Budget.” Stimson had already

requested the smaller sum. Should he ask for the balance now or later? After some discussion Marshall and Somervell decided to tell the “whole story.” They would put in for $362,000,000. “However,” the Chief of Staff remarked, “I am also concerned with the diplomatic way to handle this matter.”17

The administration would have to be ready with an explanation. That much was generally agreed. But opinions differed as to what the explanation ought to be. Hartman had wished to stress the reduction of his original estimate by General Moore, the lack of advance information about camp sites, and union demands for higher wages. Stimson wished to emphasize advancing materials and labor costs and the adversities of winter weather. Reybold attributed most of the increase to haste.18 Somervell listed hastily prepared layouts, changes in plans, rising prices and wages, unskilled workmen, overtime, speed, and bad weather. “Then,” he added, “some of the estimates were just plain dumb.”19 In the midst of all this conjecture, the President asked for an “ honest-to-God” statement of the reasons for the overrun.20

A word from Roosevelt and the Construction Division set to work. Picking up the telephone, Groves summoned to Washington contractors whose projects showed a deficit. Costs, he declared, had gone “sky high.”21 The size of the overrun seemed “inexcusable.”22 “But,” he told one man, “we have to explain it and so does the President. ... That’s why we are so anxious to have this meeting and get our explanation as to just what can be said other than ‘we are sorry to have spent more money than we have.’ “23 The conference took place on 29 December. A short time later the President had his answer. The “honest” statement gave three major causes for the overrun. It attributed 25 to 35 percent to increased costs of labor and materials, 50 or 60 percent to additional requirements, and 15 to 25 percent to changes in plans and underestimation of costs. These percentages were approximate. Precise figures were not yet available and, indeed, might never be.24

A somewhat different appraisal came from Slaughter, Saville & Blackburn, Inc., of Richmond, an engineering firm hired by Somervell to make an independent study. On 30 December General Gregory wired Constructing Quartermasters, asking them to forward plans, layouts, and cost data to the Virginia firm.25 Forty-four fixed-fee and fifty-eight lump sum projects sent replies. This information formed the basis of a 66-page report submitted to Somervell on 13 January. After comparing the original estimate with the actual costs of labor, materials, buildings, and utilities, and after analyzing an imposing array of figures, Slaughter, Saville & Blackburn concluded that “the reasons for the deficiency are speed of action in preparation

of the original estimates before sites were selected and the speed of construction required of the field forces.” Costs of utilities and labor bulked large, but neither rises in prices nor changes in plans could account for a substantial portion of the deficit.26 These findings did not go unchallenged. On discovering that many of the figures given the Richmond firm were “well-nigh valueless,”27 Groves concluded that “the Slaughter, Saville & Blackburn report is based on uncertain data and hypotheses and that the figures it gives cannot be relied upon for comparative purposes—nor indeed for any other useful purposes.”28 Groves’ criticism notwithstanding, Somervell believed the report told “the general story” and drew heavily upon it in defending the deficit.29

The day Slaughter, Saville & Blackburn submitted their report, Somervell appeared before the Budget to ask for approximately $535 million in construction money. Over and above the $362 million, he wanted $32.6 million for maintenance and repairs and something in the neighborhood of $140 million for land and for such additional items as chapels, ice plants, recreational facilities, repair shops, and access roads. Asked to guarantee that these funds would be sufficient, he refused. The Budget Director thereupon struck out the allowance for contingencies and cut the maintenance item by almost forty percent, and he reduced the deficiency fund to $338,880,000 and the fund for maintenance to $19,835,000. The request to Congress would be some $36 million less than Somervell felt he required.30

The Budget Director promised the money for 1 March. The question was whether the Construction Division could keep going until then. Ten days before the Budget hearing, at his conference with General Marshall, Somervell had estimated that funds on hand would last until the end of January. He now promised to hold out one month longer. While Somervell was making this commitment, Groves, who was also present, grew “very uncomfortable.”31 He later told a member of the Budget staff: “I was signalling frantically. If you’d watched me up there, you’d have seen me shaking my head most vigorously when General Somervell was agreeing to March 1.” It appeared to Groves that appropriations for construction would again be too little and too late.32

By early February the known deficit for troop projects had climbed beyond the $360 million mark. Architect-engineers were admitting that their previous calculations had been optimistic. Blanding, Forrest, and Shelby showed a combined increase of $19 million over December estimates. As other projects swelled the total, Groves complained,

“These engineers are fine engineers, I must say. The thing that makes me so mad is that ... the estimate of December 15 was just a joke, apparently, to them.”33 While he shared Groves’ dissatisfaction, Somervell hoped to turn the new estimates to advantage. On 11 February, the day before Congress began hearings on the fourth supplemental appropriation bill, he asked for restoration of the contingency fund, arguing that the money was needed at once.34 His eleventh-hour appeal failed. The War Department would defend a deficit of $338,880,000.

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Deficiencies of the House Appropriations Committee began on the morning of 12 February, with a company of distinguished officers on hand, among them Marshall and Gregory. The spotlight centered, however, on the chief of the Construction Division. Somervell, who had but two weeks before exchanged the oak leaves of a lieutenant colonel for a brigadier general’s stars, was the principal witness. He presented the case expertly. His detailed explanation of the overrun seemed frank and reasonable. His replies to leading questions were at once adroit and witty. The subcommittee agreed to the request turned in by the Bureau of the Budget. But, although Somervell twice introduced the subject, he could not persuade the group to add $25 million for contingencies.35 The committee bill, which the House passed on 27 February, was something of a disappointment.

Not until 3 March did the bill come before the Senate Subcommittee. This time Somervell had little opportunity to express his views. Having read the lengthy testimony taken by the House group, the Senators did not wish to have the deficit explained again. They were less concerned with the reasons for the overrun than with the failure to foresee it. “I am not complaining so much about the expenditure of funds,” one committee member said, “and I do not think that Congress is. We have all become calloused to that, ... but it is rather amazing that the original estimates could have varied as much as the amount that was really necessary to complete the jobs.”36 “In our usual search for economy,” General Moore testified, “the original estimates were made dangerously low. ... There was some argument about it, but I kept it low with the hope that ... the quartermaster and people in the field would be able to observe economies, but my hopes were dashed to the ground.”37 Somervell, who knew the latest estimate was likewise founded on false hopes, had no chance to say so. Most of the Senators’ queries were directed to General Moore. Somervell found himself confined largely to routine subjects. On 6 March the Committee on Appropriations reported the Army sections of the bill favorably and without change. The measure passed the Senate on 10 March and on the 17th the President signed it.38

The appropriation eased but did not end the Construction Division’s financial troubles. Final solution of the budgetary problem came only after completion of the projects.

Winter Construction

To those engaged in camp construction—contractors, engineers, and workmen—the winter of 1940–41 was a time of unusual challenges and strenuous effort. It was a time of mud, high winds, frozen ground, and stalled equipment; of urgent demands, unremitting pressure, long hours of work, and increased personal hazards. It was also a period of changing schedules, critical shortages, and maddening delays. Few construction men had experienced anything like it before. One engineer declared, “There is no work in the world as hard as building a cantonment under the conditions imposed.”39 But if the difficulties were great, great too was the accomplishment. During the winter months, the camp projects were virtually completed.

At the center of the effort to complete the camps was the Operations Branch. (Chart 8) The December reorganization had augmented both its duties and its staff. Among the persons assigned to Colonel Groves at that time were Violante’s top assistants, including Winnie W. Cox, an able administrator who had been with the division since World War I, Maj. Orville E. Davis, Capt. William A. Davis, Capt. Donald Antes, Creedon, and Kirkpatrick. While Groves relied heavily upon such stalwarts as these, he strengthened his organization by bringing in more officers. Recalled to duty as a lieutenant colonel, former CE Regular Thomas F. Farrell gave up his post as chief engineer of the New York Department of Public Works to become Groves’ executive. Lt. Col. Garrison H. Davidson, CE, became Groves’ special assistant. George F. Lewis, formerly an Engineer lieutenant colonel, took charge of Repairs and Utilities. Four of the Quartermaster’s West Point careerists also joined Groves’ team; Maj. Kester L. Hastings, Capt. Clarence Renshaw, Capt. Howard H. Reed, and Capt. Carl M. Sciple. With these four, plus Lewis, Davidson, Kirkpatrick, W. A. Davis, and Groves himself, the branch now had nine Academy graduates. To fill longstanding needs, Groves created two new sections. The first, headed by Lloyd A. Blanchard, inaugurated a program of accident prevention; the second, under George E. Huy, maintained a uniform system of cost accounting. The improved organization enabled Groves to give the program better direction and to help the field surmount numerous obstacles.

The winter of 1940–41 was unusually severe. Contrary to the hopes of construction men it began early. While September and October had been abnormally dry in most parts of the country, November rainfall was above average in thirty-two states. Bad weather set in around Thanksgiving. Cloudbursts hit camps in Texas and Arkansas late in November. During the next month steady rains settled over the states along the lower Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. Meanwhile, in New England frosts were occurring nightly. Soon the ground began to freeze, and by Christmas northern camps were blanketed with snow. Across the continent, California was

Chart 8: Organization of Operations Branch, Construction Division, OQMG, January to March 1941

experiencing the wettest December in living memory. The new year brought no improvement. During January and February storms swept the West, South, and Midwest. In the North freezing temperatures prevailed and blizzards raged. Old-timers avowed that this was the worst winter in many years. Official statistics confirmed their view. Baton Rouge recorded “its worst rainy season in ten years;”40 Los Angeles, its “heaviest and most continuous rainfall ... in forty-three years;”41 Topeka, the wettest winter “in the history of the Weather Bureau.”42

This weather was extremely unfavorable to construction. In the South, where a majority of the camps were located, rains turned unfinished projects into seas of mud. Serious floods occurred at Wallace, Hulen, and Shelby.43 This story was repeated in the West and Midwest. At one point high waters threatened key projects in California and Missouri. On 27 December the contractor at San Luis Obispo telephoned Groves: “We are completely flooded out here. ... We have had a whole season’s rainfall in about ten days. ... It is still raining.”44 That same day one of Groves’ inspectors reported that prolonged rains at Camp Leonard Wood had made field work “hazardous and in some cases impossible.”45 Nowhere were conditions worse than in the North and East. There workmen battled snow, sleet, high winds, and subnormal temperatures. By the first of January the ground at Pine Camp, New York, had frozen to a depth of twenty-six inches. At Devens frost penetrated to a depth of four feet. At Meade intermittent freezes and thaws harassed construction crews.46 Few projects escaped the crippling effects of inclement weather.

The onset of winter found many jobs in the midst of paving and grading. Unfinished roads washed out at a number of locations. Traffic in wet weather ruined $200,000 worth of subgrade at Camp Bowie. Similar losses occurred at Robinson, Claiborne, Livingston, and Wood.47 Roadbuilding was everywhere a tough and expensive job. Prolonged rains forced contractors to plow out mud with heavy equipment and to lay down huge quantities of rock and gravel. Where thermometers dropped below freezing, builders had to use heated concrete and early-strength cement and to protect freshly poured concrete for at least seventy-two hours with straw, tarpaulins, and salamanders.

Winter was a period of low production. Bad weather cut deeply into construction

Scene at Camp San Luis Obispo After Heavy Downpour, February 1941

time. Meade lost 30 out of a total of 116 possible working days; Bowie, 38 out of a total of 150. At the Presidio of Monterey, operations were suspended on 16 days within a 2-month span. During a single week in December, Camp Leonard Wood missed 4½ days.48 Occasionally, goldbricking prolonged layoffs. Writing from Camp Davis, Major Davidson complained, “Local labor is so spoiled by their unaccustomed income that they not only lose the rainy days but also the following day when they steer clear of the job until the ground dries out.”49 Somervell gave another view of labor’s performance during this period:–

I went to Devens, Edwards, Pine Camp, Madison Barracks, and Fort Ontario, and the blizzard followed me all around, so that I had a good opportunity to see what was going on. It was below zero at Pine Camp and at Devens, and the men were out there trying to do their work, and they were doing it, but obviously at a very much reduced efficiency.

I visited Fort Meade ... during a moderate drizzle, where the mud was up to your knees, and where the workmen were

Pouring Concrete in Subzero Weather, Pine Camp, New York

trying to dig trenches, lay pipe, and things of that kind, which they were doing at, I should say, about 25 percent efficiency.50

Increased cost was a corollary of lowered efficiency. To make up for lost time, projects worked long hours and double shifts. The contractor at San Luis Obispo operated 10 hours, 5 days a week, and 8 hours on Saturdays during the winter months, thereby adding $600,000 to the cost of his camp. Overtime and multiple shifts increased the payroll at Camp Leonard Wood by $1,839,690 between December and April. Coupled with the expense of sheltering men and equipment from the elements, removing snow and mud, employing special techniques for cold weather construction, and replacing facilities damaged by storms, bills for overtime and shift work brought the cost of winter operations to a sizable total. Bad weather increased project costs an average of 10 percent. Of thirty-four contractors questioned by a congressional committee, all but one reported that costs had risen sharply as a result of winter conditions.51

As costs rose, contractors came under increasing financial strain. More money was being paid out and less was coming in. Slow to begin with, reimbursements lagged further and further behind as appropriated funds dwindled. By February 1941 contractors had more than $325 million tied up in Quartermaster projects. Groves tried by various means to ease their distress. He became adept at “trading dollars,” transferring money from projects which had funds to projects which were short. He put more pressure on the field auditors, urging them to speed up reimbursements and place available funds in contractors’ hands as soon as possible. Lastly, he arranged for contractors to tap additional sources of capital. Under the Act of October 9, 1940, claims against the United States could be assigned to private financial institutions. By invoking this law, Groves helped a number of contractors to borrow. Among the first concerns to do so was Starrett Brothers and Eken, which obtained a loan of $915,000 by assigning the Blanding contract to the Manufacturers Trust Company of New York in late December. Other firms followed suit.52 The situation could not go on indefinitely. By early March Groves and the contractors had reached the end of their financial tether. On the 4th Reybold notified Gregory that he could go ahead with construction “even though funds may not be on hand.”53 Deficit spending could continue until money from the new supplemental appropriation became available late in March.

Shortages of materials and installed equipment drew more complaints from contractors than weather and money. During the third week in January shortages were listed as delaying factors by 45 percent of the projects; the weather, by 28 percent; and lack of funds, by only 2 percent. Progress reports submitted on 7 February showed 42 percent held up for lack of supplies and equipment as against 22 percent for weather and less than 4 percent for funds. Both contractors and CQMs consistently named scarcity of critical items as the leading cause of delay.54 Somervell was skeptical of these reports. “I am wondering,” he confided to Groves, “how much of this alleged shortage is real and how much of it is an alibi of the contractors for not getting on with the work.”55 No doubt there was some exaggeration. Nonetheless, some shortages were truly desperate. On 7 March the contractor at Camp Wallace appealed to his CQM:–

We are now short of lumber with which to complete the project. We, today, will have to lay off two hundred carpenters. This lumber was purchased by the War Department ... and has been dribbling in promiscuously without any regard to our requirements. Today, we have structures standing with [out] roof sheathing, others without siding, and [on] others we have nothing but the foundation sills, and on still others we have the foundation sills and first

floor joists. We have to rob materials from one building to do something with another, and it makes the progress very slow and costly.56

Items reportedly in short supply fell into three classes: those purchased by Major Wilson’s Procurement and Expediting Section, those purchased by The Surgeon General, and those purchased locally by contractors. Included in the first category were lumber, millwork, boilers, furnaces, and equipment for kitchens and laundries. Hospital equipment was in the second category; sheet metal, structural steel, plumbing and electrical supplies, and hardware were in the third. An investigation ordered by Groves in February indicated which items were critically short and some of the reasons why. “With regard to lumber and millwork,” the investigator stated, “the shortages are not critical at the present time, unless the contractor has delayed placing his orders through the Procurement and Expediting Branch until he has run out of these materials.” The same was true of furnaces and boilers. The scarcity of kitchen equipment was nothing more than a lack of luxury items, such as puree mixers and potato peelers; all stations had received essential items, such as refrigerators and stoves. The demand for laundry equipment had exceeded production, but deliveries were gradually coming through. The supply of hospital equipment was gravely inadequate. The Surgeon General had promised to report on the situation but so far had not done so. Among items procured by contractors, serious shortages existed in structural steel, plumbing supplies, and electrical equipment. The report did not comment on reasons for these troubles.57

Contractors were feeling the effects of the priorities system. Established during the summer of 1940, this system was administered by NDAC until January 1941, when the newly established OPM took it over. The two agencies’ procedures were essentially the same. Both established a Critical List of materials. ANMB issued priority ratings applicable to items on these lists. Preference ratings, issued by purchasing officers whose projects had priorities, governed the sequence in which suppliers filled orders. Although ANMB had considerable freedom of action, NDAC and OPM had final say on major questions of policy. From the beginning, military construction jobs rated low priorities, so low, in fact, as to be practically meaningless. Because some key construction commodities, such as lumber, were not on the Critical List, and because shortages of listed items, such as steel, did not become acute until late 1940, camp contractors for a time were able to get along without priority assistance. But by early 1941 they were calling for help. Efforts during February to obtain higher priorities for camps met with little success. The best OPM would do was to grant an A-1-j priority, the same rating assigned to naval vessels scheduled for completion in several years.58 Recalling OPM’s action, Groves denounced “the viciousness of the priority system, particularly with respect to the tremendous

disadvantages under which military construction had to operate.”59 To improve the situation would require a long, hard fight.

Major Wilson in P&E gave the projects what help he could. He kept delivery schedules for centrally procured items under constant review and channeled shipments to neediest sites. In January he created an expediting unit to investigate each shortage reported from the field and to try to find a cure. In February he established closer ties with the projects by placing a supply officer in each of the nine zones. Throughout the early months of 1941 he exerted steady pressure upon vendors to speed deliveries. Wilson achieved a better distribution of building supplies, but there was little or nothing he could do toward solving basic problems of production and priorities. As long as demand exceeded output and Quartermaster projects had no prior claim upon supplies, some contractors had to wait.60 Not until the program neared completion did the percentage of projects delayed for want of materials and equipment show a marked decline. On 4 April Groves reported. “All requirements for critical items have been met by actual delivery, but minor articles cannot be delivered from the factories on time.”61 As late as 2 May orders for kitchen, heating, and hospital equipment and for structural steel and plumbing fixtures were still outstanding.62

Shortages of skilled labor also ranked high among delaying factors. Thirteen percent of the projects needed additional craftsmen on 25 January. The figure stood at 11 percent on 7 February and at 10 percent two weeks later.63 Among the trades most often listed as critical were plumbers, steamfitters, electricians, rod setters, and sheet metal workers. Although the Construction Division occasionally tried to alleviate these shortages by raising wage rates or authorizing overtime, it did so only in extreme cases. For the most part it left the problem to contractors and the unions. While reminding contractors “that full responsibility for the employment and management of labor”64 rested with them, the division notified the unions that they “must accept some responsibility for endeavoring to man these jobs.”65

Although they willingly took up the challenge, the unions were unable to satisfy demands for skilled workmen. Appraising their effort, one contractor said: “We have been trying to get additional men through the local unions. We get a few each day, but almost the same number leave the job.”66 Another reported that requests for 325 plumbers and steamfitters had brought only 172 workmen to his project. A third protested that the union had certified 19 men as rod setters, although only 4 had any

experience in that trade.67 Project after project echoed these complaints. Against the nationwide shortage the combined efforts of contractors and unions were of little avail. The program suffered throughout from a scarcity of skilled mechanics.

Strikes also had adverse effects. Between 17 March and 30 June 1941, the earliest period for which full information was available, twenty-two strikes occurred at troop projects. Twelve of these walkouts involved jurisdictional disputes and protests of various sorts; they accounted for a total of 366 man-days lost. The other ten, all involving wage disputes, accounted for a total of 9,230 man-days lost. Man-days lost because of strikes were only a tiny fraction of total man-days at the projects.68 Nevertheless, effects of work stoppages could not be measured solely by time lost. The report on a 2-day strike at Camp Davis early in March was revealing:–

Job operations were proceeding at full speed before the strike, and a high point of efficiency of operations had been reached. The strike killed the momentum of operations, and efficiency had to be developed again through weeks of hard effort. The loss has been figured by comparison of percentages of progress during month of February with percentages of progress through month of March. That comparison shows that 7 percent of progress was lost during March.69

Production suffered less from strikes than from union restrictions on output and resistance to timesaving methods and machines. Union rules designed to spread work and maintain traditional methods were in force at many projects. Bricklayers continued their normal practices of using only one hand and of beginning a new course only when the preceding course was complete. Plumbers refused to install made-to-order pipe, insisting that they do cutting and threading by hand at the site. Painters opposed use of spray guns; cement workers, use of finishing machines. Several crafts demanded that skilled men perform unskilled tasks. Although the Construction Division occasionally succeeded in having working rules suspended, restrictive practices continued to prevail.70

Belated and oft-changed plans presented an added handicap to constructors. According to the Fuller Company, tardy deliveries of specifications and layouts hindered the project at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, from start to finish. Long-Manhattan-Watson gave “inadequate or delayed plans” as one reason for high costs and slow progress at Riley. Almost three months after work began at Devens, Coleman Brothers Corporation and John Bowen Company were still awaiting designs for several buildings.71 Plans

contractors had received were under constant revision. So great was the confusion at Camp Leonard Wood, where plans were changing “all the time,” that the exasperated architect-engineer predicted completion of the project “within about five years.”72 So frequent were changes in the layout at San Luis Obispo that the contractor “actually considered constructing the buildings on skids so that their location could be changed without delaying the work.”73 The difficulties increased in the weeks that followed. Interference by troop commanders grew as the time neared for occupying camps. Demands for cheaper designs intensified as the deficit rose. The Engineering Branch, unable to cope with a mounting backlog of requests for new plans, fell further behind in its work.74

Most disconcerting to contractors was military control of building schedules. By January the old scheme of final completion dates had all but disappeared. In its place was a system of “priority schedules” calling for completion in successive stages. The contractor who had originally agreed to turn over a finished camp on a given date now had to turn over housing for a few units at a time. At Camp Roberts, for example, instructions to be ready for 178 men on 1 January, 2,882 on 15 February, 7,893 on 15 March, and 5,179 on 15 June superseded the completion date of 15 March.75 Priorities reflected induction dates. When a commander determined the size, composition, and arrival dates of various units and designated the buildings each unit would occupy, he imposed a construction schedule on the contractor. Each time the commander changed his plans, he compelled the contractor to do likewise. Builders disliked this system because it denied them “the leeway that a contractor should have in order to prosecute and expedite a job placed under his care.”76 Contractors were not the only critics. “One item that has cost millions of dollars,” Captain Renshaw told Groves, “has been the shifting of construction forces from area to area to meet the changing requirements of Commanding Officers.” Citing the case of a contractor ordered to rip equipment out of one group of barracks and install it in another group at the opposite end of the camp, Renshaw commented, “The change in flow of materials ... created a confusion just as great as if the Ford Manufacturing Company tried to finish the last car on the production line first.”77

Illustrative of the workings of the priorities system were events at Camp Meade, Maryland. Late in September, when Hartman awarded Consolidated Engineering of Baltimore a fixed-fee contract for a cantonment for the 29th Division, he assigned the project a completion date of 6 January 1941. Work began on 9 October. Adhering to orthodox methods, Consolidated divided the job into seven areas; appointed superintendents, foremen, and pushers for each area; and scheduled the work so that

crews of excavators, foundation workers, carpenters, and so forth, would follow one another “in proper sequence and in proper rotation” from area to area. Since all of the seven areas would reach completion within a short time of one another, this arrangement was consistent with the principle of final completion dates. The contractor ran the job along these lines for three weeks. Then, relaying orders from the General Staff, Hartman on 31 October asked Consolidated to finish buildings for two battalions of tank and antitank troops by 11 November. In an effort to meet this date, the contractor pulled men off jobs in other parts of the camp and worked twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. No sooner were these buildings completed than Hartman forwarded a second rush order, this one for facilities for the 30th Ordnance Company. These directives were the first of twenty-five or thirty priority orders—some originating with the General Staff, some with the corps area commander, and some with the commanding general of the 29th Division—which disrupted Consolidated’s plans.78

Noteworthy among the Meade priorities was one established late in November by the General Staff. Issued shortly after the new corps area commander, Maj. Gen. Walter S. Grant, had predicted that the camp would not reach completion before March, this order stipulated that housing for 12,000 men, the peace strength of the 29th Division, would have to be ready by 8 January. When he got this order, the contractor hurriedly reorganized the job, concentrating his forces in half the building areas and discontinuing work in the other half.79 This approach, though sound from the constructor’s point of view, was militarily undesirable. Around 15 December, Maj. Gen. Milton A. Reckord, the commander of the 29th, asked that construction “be so arranged that each regiment could go into its own area when it arrived from home station.”80 General Grant made a similar request.81 Agreeing that the commanders were “entirely justified for use considerations,” Groves issued the necessary instructions. The contractor reorganized the job again. Part of the construction force moved back to locations deserted a few weeks earlier, abandoning partially finished buildings and starting new ones. Work now focused on half the buildings in all the areas rather than on all the buildings in half the areas. With these changes, hopes of meeting the 8 January date collapsed. A few days after Christmas, Groves pushed the deadline back to 3 February.82

Throughout January the contractor worked furiously. The project again adopted a 7-day week. No effort was spared. On the 23rd, the project received a severe blow—the project engineer, the spark plug of the job, died in an automobile accident. By the first of February

considerable work remained on the artillery area and the station hospital. Inducted on 3 February the men of the 29th Division remained at home stations for fifteen days, instead of the usual ten. Not until there was steam in the hospital boiler did General Reckord order his men into camp. Meade was completed some months later at a cost of more than $21 million. Among factors affecting its cost and progress were the site, the layout, bad weather, labor troubles, and the loss of the project engineer. Nevertheless, both the architect-engineer and the Constructing Quartermaster placed particular emphasis on priority scheduling.83 Reviewing his experience at the project, W. C. Roberts of the Greiner Company offered the Army this advice:–

In order to hold a contractor for the economy in that particular respect [building construction], he should be allowed to build his cantonment without interruption during the construction period. In other words, he should be held responsible for finishing all of his buildings in the whole camp by just one date, and he shouldn’t, to obtain that ultimate economy, be held responsible for finishing various portions of the regimental areas prior to the general completion of the whole camp.84

In view of the military situation, such a procedure would, of course, have been impossible.

Despite heroic efforts by contractors, the program made faltering progress. Again and again Somervell had to play for time. The Surgeon General eased the pinch by extending hospital deadlines and G-3 relaxed the schedules for occupying replacement centers. But the Guard camps posed a tougher problem. Late in 1940 the General Staff had agreed to call no Guard units until Colonel Groves had set dates for housing them. But calls to the Guard had to go out forty days in advance. With the uncertainty of winter operations, no one could possibly predict so far ahead how much construction would be in place on a given date. Groves wrung a small concession from G-3, a promise to hold newly inducted Guardsmen at home stations for fourteen days instead of the usual ten. But two weeks’ grace on construction deadlines was seldom enough. Time after time the General Staff had to cancel orders calling units to active duty. Each cancellation further disrupted mobilization and inconvenienced Guardsmen waiting to begin their training.85

The plight of the Guardsmen attracted wide notice. These men had arranged their affairs with the original dates in mind. Some had resigned from their jobs. Others had trained substitutes to do their work. Lawyers and physicians had turned their practices over to civilian colleagues. Households had been broken up, homes sublet, and dependents provided for. Postponements worked appreciable hardship on the men and their families. Guard

Camp Blanding, Florida, Late November 1940

officers, public officials, and others protested the delay. Some advocated calling the men immediately and quartering them in public buildings until camps were ready.86 In the face of mounting pressure for early inductions Assistant Secretary Patterson stated, “I have resolved that, unless the international situation becomes acutely critical, I shall postpone induction of National Guard units until the War Department is prepared to safeguard the health and well-being of the members of such units through the provision of adequate shelter and sanitary facilities.”87 Despite Patterson’s determined stand, agitation served to hasten the calling of the Guard.

A number of camps were occupied prematurely. Units went to unfinished projects, where discomfort awaited them. At Shelby troops quartered in undrained areas had to wade through water to get to their tents. At Barkeley there were not enough latrines. At Blanding the men of the 31st Division underwent a painful ordeal.88 Representative Joe Starnes, an officer of this division, gave a firsthand account of conditions at the Florida camp: “A regiment of 1,815 men was moved in with not a single kitchen, latrine, or bathhouse available. This occurred in December in a pouring rain and conditions were such that it was impossible to use the straddle latrine. Only the grace of Almighty God prevented an epidemic.”89

Elsewhere epidemics did occur. Flu struck Fort Lewis early in December. From there it traveled down the Pacific Coast, across the Southern States, and up the east coast to New England. At many camps there were also outbreaks of measles. At one point San Luis Obispo reported 970 sick out of a total population of 11,500. At Lewis the sick rate for a time was more than 11 percent. Fortunately, the Army was prepared, having learned that flu epidemics go hand in hand with troop mobilizations and that newly inducted men who have not acquired immunity almost always come down with measles. Hospital beds were waiting for most of the sick. At camps where the number of cases exceeded expectations, barracks had to serve as wards.90

The presence of troops hindered construction. Military traffic clogged roads to building sites, blocking the flow of supplies. Commanders drew labor from important jobs to make quarters more comfortable. Soldiers pilfered construction materials and wrecked expensive equipment. Workmen, arriving in the morning to find that their supplies had vanished during the night, waited in enforced idleness until replacements came in over congested roads. Under such circumstances disputes were bound to occur. The Constructing Quartermaster at Bowie had a hard time stopping troops from carrying off black top to pave their company areas. Men of the 37th Division became unruly when the CQM at Shelby tried to stop them from stealing five truckloads of materials. When soldiers altered unfinished buildings, this same CQM quarreled so bitterly with the division commander that Groves sent Captain Sciple to restore peace. Fresh arrivals usually brought fresh troubles. Colonel Styer tried to forestall shipment of troops to half-completed camps—but without much success.91

Once begun, movement of troops to construction projects continued. Between 23 December and 5 March nine National Guard divisions entered federal service. The strength of the Army increased by about 100,000 during January, by about 150,000 during February, and by nearly 200,000 during March. By 1 April it had passed the 1-million mark.92 Meanwhile, construction went forward. In the midst of huge concentrations of troops builders pushed toward completion.

The coming of spring enabled contractors to make a better showing. The number of projects on or ahead of schedule rose steadily. A few camps continued to lag but nevertheless met their troop arrival dates.93 On 15 April 1941 Secretary Stimson declared: “The status of our construction is in such an advanced

Men of the 29th Division at Camp Meade, Maryland, May 1941

condition that we can confidently assure the country that all of the remaining men in our proposed military program will find their quarters awaiting them ready and completed for their occupancy.” On the 22nd General Marshall stated, “We have gotten over the hump.”94 Two days later Somervell announced, “The new Army is housed.”95 Remaining work went smoothly. Contractors made a fine record at replacement training centers, finishing all but one by mid-May. Of the 760 buildings that comprised the nine general hospitals, 665 were ready for occupancy in June. By the end of the fiscal year the program had met its goals.96

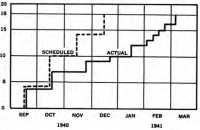

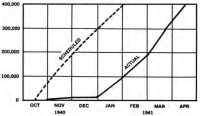

The time and cost estimates made by the General Staff in the summer of 1940 had proved to be grossly erroneous. Inability of construction forces to meet impossible deadlines had made necessary substantial changes in plans for expanding the Army. Induction of Guardsmen and selectees for the Protective Mobilization Force was not complete until two to three months after the time originally set. (Charts 9 and 10) The program had cost about double the figure initially given to Congress. Referring to the original camp completion dates, General Hastings later said:–

In the general concept of the time required to prepare, I don’t think General Staff, or Congress, or the President himself realized the amount of time it takes to do things—to create the supplies, to build your facilities. They thought ... “A million men will spring into arms overnight.” Months go into years to do these things. They always have and they always will.97

Commenting on the time and money that went into construction, General

Barnes General Hospital, Vancouver, Washington

Chamberlin stated:–

Actually a phenomenal standard was set, one in which all Americans can glory. As far as wasting a few dollars was concerned, the construction effort cannot hold a candle to lease-lend, the Marshall Plan, or the Military Assistance Program. Had it not been for the courageous performance of those in charge of the War Department in the emergency, we might well have been defeated, and how then would the expenditure of a few millions have loomed in the long-range picture.98

At the conclusion of the program, the Quartermaster Corps received congratulations. “Taken as a whole,” Patterson said, “the job was well and speedily accomplished.”99 Secretary Stimson stated, “I think I am speaking in measured language when I say that in no country in the world, including our own, has its military forces ever before been provided for in so brief a time and upon so adequate a scale.”100 Speaking before the House of Representatives, Congressman John W. McCormack declared, “The record of accomplishment during the six months that the present construction program has been in force is astounding in comparison with that of the 18 months of the World War period which has always been pointed to as

Chart 9: Rate of National Guard Inductions, Scheduled and Actual

Source: (1) Incl w/WD Ltr AG 325 (7-22-40) M-C-M, 30 Jul 40, sub: Induction of certain NG Units into the Federal Service. G-4/31948.R. (2) Memo, G-3 WD for C/S, 14 Aug 40. sub: Determination of addn costs for F.Y. 1941. … G-4/31453-18. (3) Inch w/Ltr BOWD to Chiefs of Estimating Agencies. 26 Aug 40, sub: Determination of addn costs for F.Y. 1941. … Nat Arch AG 111 9-24-38 (1) Sec. 3. (4) The Army Almanac. 1950. pp. 528.--44.

Chart 10: Rate of Selective Service Inductions, Scheduled and Actual

Source: (1) Memo. G-3 for CofS. 14 Aug 40, sub: Determination of addn costs for F.Y. 1941. … G-4/31453-18. (2) ASF, Mil Pers Div. The Procurement of Military Personnel, 1 Sep 1939 to 1 Sep 1945, Vol. II, p. 415.

bordering on the miraculous.”101 Praise was by no means universal. Nevertheless, the Construction Division could take pride in its achievement.

Closing Out Contracts

As troops began moving into camp, Somervell decided to get fixed-fee contractors off the jobs as soon as possible. To be sure, much work remained. Construction of chapels, theaters, field houses, and two or three other “extras” awaited funds. At many projects, painting, screening, paving, and cleanup operations awaited warm weather. At several camps, large-scale undertakings were in the planning phase. There were strong arguments in favor of letting contractors finish the camps—their familiarity with the sites, their proved capability, and their seasoned organizations—but economy indicated another course. Overhead on fixed-fee work was averaging about 5.6 percent as compared with 4.4 percent on lump sum and purchase and hire.102 Part of this difference was no doubt due to the higher cost of administering fixed-fee contracts; part, to the higher price of first-rate management. Not only was overhead higher on fixed-fee jobs, but, many believed, construction itself cost more. With speed no longer a pressing concern, emergency contracts seemed unnecessary. On 1 March 1941 Somervell sent orders to the field: “It is essential that construction projects which are nearing completion be promptly terminated at the earliest practicable date.” Minor construction needed to complete the camps would be done by lump sum contract or by purchase and hire.103

As big construction jobs generally do, the fixed-fee projects tended to drag on. At camps nearing completion, Somervell noted an inclination on the part of CQMs, contractors, and architect-engineers “to continue their organizations at greater strength than necessary in anticipation of the assignment of additional work.”104 “You could almost say it is a universal tendency,” Groves observed. “I think it is a human trait.”105 Styer foresaw difficulty in terminating contracts “as long as there is any prospect of additional work because the architect-engineer, the contractor, and the CQM will all want to hold their organizations together.”106 With the aim of shutting off fixed-fee operations as soon as the main job was over, Somervell notified the field: “Neither rumors, requests by troop commanders for additional work, nor knowledge of future work still under consideration by the Washington office are any justification for delaying the prompt termination of existing contracts.”107 Going a step further, he adopted a system of cutoff dates. When authorized work was substantially complete, or when contractors reached convenient stopping points, CQMs would issue letters of acceptance or stop orders to the contractors, giving them so much time to wind up operations.108 On

learning that Somervell intended “to really have a cutoff date at each one of these jobs,” Harrison telephoned Groves:– “That is the only way to handle it.” Groves agreed. “I learned that years ago,” he said, “after going to Boulder Dam and seeing that after three years the payroll was still 1500 men.”109

Closing out fixed-fee jobs went more slowly than Somervell had hoped. At 45 camp and general hospital projects nearing completion in March 1941, there were 85 fixed-fee architect-engineer and construction contracts. By 15 April all but seven of these contracts were still on the books.110 Efforts to expedite the setting of cutoff dates intensified. In mid-April Somervell notified the zones: “I, of course, do not want the jobs closed out prematurely, but I do want them stopped as soon as you have reached a logical stopping place.”111 Early in May, when the number of closed-out contracts totaled twenty, he asked Groves to bear down on the field.112 Groves put more pressure on the CQMs and told contractors frankly, “We just have to get you boys off our payrolls.”113 Knowing that many of the firms would soon be taking on new projects, he encouraged them to hold their organizations together, but not at the government’s expense. He suggested instead a few weeks’ vacation. The closing out operation gathered speed. Eighteen contracts ended in May; twenty-four, in June; and eleven, in July. By late August fixed-fee contracts were still in force at only four projects. At Aberdeen, Polk, and Knox, the Army extended the original contracts to cover major additions. At San Luis Obispo the contractor stayed on to build a $3-million water supply system—a dam across the Salinas River, a pumping station, a mile-long tunnel, and a 12-mile pipeline to bring water through the mountains.114

To shut down projects and terminate contracts was no simple undertaking. There were many details involved: transferring police forces, fire departments, and maintenance crews to post jurisdiction; disposing of surplus materials, salvaging scrap, and clearing away debris; recapturing or releasing rented equipment; completing paperwork, bringing audits up to date, and clearing records of pending items such as unclaimed wages and unpaid bills; and lastly, reaching final settlements with contractors. While some of these were routine tasks, others proved troublesome. Recurring false reports of buried nails and burned lumber needed refutation. Contractors’ complaints that delays in the government’s audit were preventing them from closing their books needed looking into.115 Major problems arose in

Spillway under construction at dam site, Camp San Luis Obispo, March 1941

connection with recapturing equipment and settling contractors’ claims.

Under its agreements with fixed-fee contractors and third-party renters, the government could recapture leased equipment when projects reached completion. As the program neared its end, the question arose—how much equipment to capture. The nationwide shortage was still critical, and the recently approved lend-lease program promised to make it even worse. The Army needed large fleets of equipment to maintain newly built installations and to equip Engineer construction units. WPA and CCC, both heavily engaged in defense work, were short of trucks and machinery. Here was an opportunity not only to get the needed items but to get them cheap. After consulting the Engineers, WPA, and CCC, Somervell outlined a recapture policy. Generally, he would take only late models which were in good repair and in which the government’s equity was 60 percent or more. He would capture no item until one of the interested agencies had spoken for it. The zones would coordinate the effort, serving as clearing houses for

requests and lists of items available, refereeing disputes among government agencies, and overseeing transfer of titles and funds.116

Unlooked-for complications soon developed. Many pieces of equipment desired by the government were heavily mortgaged and, thus, subject to prior liens. Some rental agreements contained loopholes which enabled the equipment to escape. Some valuations were so inflated that recapture was out of the question. These were relatively simple matters. The big headache was with the owners. When they learned that their equipment would be captured, many complained. Some pleaded hardship, maintaining that the loss of their equipment would force them out of business. Others, outraged and indignant, quoted promises they had received from Quartermaster officers that the recapture clause would be inoperative. Congressmen and AGC officials backed the owners’ protests. Nevertheless, Somervell refused to yield, taking the position that a contract was a contract and the owners ought to have known that when they signed.117

Recapture went forward. By 1 June 1941, the Army had taken over 44,554 items of equipment valued at $12,890,097. By the spring of 1942 the total value of captured items had climbed to $30 million; by fall, to $70 million. The Army put this equipment to good use in construction and training and eventually shipped the bulk of it overseas for use by troops in theaters of operations.118 “This actually saved the Army a tremendous amount of money,” said Groves, “and enabled it to have equipment which it otherwise could not have obtained even by throwing a tremendous additional burden on the manufacturers of construction equipment.”119

Even more challenging than the problems of recapture were those of final settlement with fixed-fee contractors. As the program neared an end, claims piled up rapidly. Contractors found many reasons for asking higher fees. Their projects had cost far more than the estimates on which their fees were based. They had done much work not covered by the original contracts and had remained on the jobs long past the original completion dates. Many had paid out sums for travel, entertainment, advertising, telephone calls and telegrams, and legal and banking services, expecting reimbursement, only to have their vouchers disapproved. By February 1941, requests for additional payments were flooding the Legal Section of the Engineering Branch. In handling this spate of claims, Major Jones, chief of Legal, relied heavily on the Contract Board. Established during the reorganization of December 1940 and having as its principal function the negotiation of contracts, the board consisted of Loving, who was chairman, Tatlow, and Maj. Clyde M. Hadley of the Judge Advocate General’s Department. Because Loving and Tatlow had negotiated most of the contracts, they

were in a particularly good position to advise on matters of interpretation and intent.120

Disputes were many and involved. The government had agreed to pay all costs of construction except interest and home office overhead and to adjust fees whenever there were “material changes” in the amount or character of work described in the contract or in the time required for performance. Which expenditures were chargeable to home office overhead? Which to the cost of the projects? Were some improper and therefore nonreimbursable? What constituted a material change? Did painting all the buildings entitle a contractor to a larger fee? Did putting up a few additional structures? Could a contractor who had accepted the Army’s original estimate of $110,000 for “all necessary utilities” at a camp point to the actual cost of $1.8 million as evidence of material change? These questions and others like them had to be resolved to the satisfaction of both parties if lawsuits were to be avoided.

In reaching settlements with the contractors, Jones had first reference to the contract documents and to the laws governing emergency agreements. When the contracts were vague or the law silent, he consulted the Contract Board and reviewed the record of negotiations. He referred particularly complex questions to the Comptroller and Judge Advocate Generals for decision. Because the contracts provided reimbursement for certain unspecified items, he paid practically all disputed vouchers. Only damages resulting from a contractor’s negligence and such obviously improper items as entertainment met with disapproval. Because Congress had outlawed percentage contracts, Jones turned down claimants who argued that costs had exceeded original estimates, denying additional fees even to contractors who had constructed utilities costing many times the figure mentioned during negotiations.121 In adjusting fees to cover material changes in the scope of the work and the duration of the contract, he generally proceeded as if the agreement “as originally negotiated ... had included the subject change.”122

As the volume of claims increased, Jones urged establishment of a fact-finding board to assist in settlement of disputes. On 29 July Somervell informed the Under Secretary that the Construction Division wished to organize such a group but pointed out that the plan depended upon Patterson’s willingness to set up a board of appeal. Patterson waited four months before taking the necessary action. Jones meanwhile was receiving about eighty claims each week. Finally on 7 November 1941 the Under Secretary established the War Department Board of Contract Appeals and Adjustments. Three weeks later Gregory formed the Contract Settlement Board, OQMG. Henceforth claims went to one

or the other of these boards. The Contract Settlement Board had jurisdiction over cases involving $50,000 or less; its counterpart in Patterson’s office handled larger claims and heard appeals from decisions of the Quartermaster group. That most contractors considered the boards’ decisions fair was evidenced by the fact that few went to court to obtain additional concessions.123

Months and sometimes years went by before final settlements were reached with camp contractors. Meanwhile, the camps were fully operational as Army training centers.

Maintenance and Operation

With their roads, streets, and rail terminals, their water, sewage, and electric systems, and their hospitals, laundries, bakeries, cold storage buildings, warehouses, fire stations, post offices, telephone exchanges, clubs, and theaters, the 46 new camps and cantonments resembled modern cities. There were, in all, 700 miles of gas lines, 804 miles of railroad tracks and sidings, 1,500 miles of sewers, 1,557 miles of roads, 2,000 miles of water conduits, and 3,500 miles of electric cables to keep up at these posts. There were nearly 46,000 furnaces, boilers, and heaters to fire. There were sewage disposal plants with a combined daily capacity of 86,729,866 gallons to operate; dams with a total capacity of 4,000 acre-feet to tend; and water tanks and reservoirs with a total capacity of 118,570,600 gallons to maintain. In addition there were matters of fire prevention, pest control, sanitation, and housekeeping. Vast though the undertaking was, it received little attention during 1940. Occupied fully with getting the camps built, Hartman could do little in the way of planning how to run them later on.124

In December 1940, finding the Repairs and Utilities Section almost totally unprepared to operate soon-to-be-completed camps, Somervell swung into action. Money was the first consideration. Totaling approximately $60 million, the sums so far appropriated were inadequate for the purpose. On 20 December Somervell asked Groves to prepare new estimates; by mid-January the battle for funds was under way. The second need was for equipment. Plans took shape for transferring recaptured equipment to maintenance crews. The third requirement, competent administrators, would be most difficult to fill. Experienced officers could not be spared for maintenance assignments at all the big new posts.125

Early in January Somervell hit upon the idea of calling in city managers. On the 8th he wrote to Groves: “I talked this thing over last night with Mr. Loving and he seemed to think there are many such people we can get ... people who are tops in their professions.”126

Aerial view of Camp Jackson, South Carolina

A short time later he got in touch with Col. Clarence O. Sherrill, who had resigned from the Corps of Engineers in 1926 to become city manager of Cincinnati, a post he still held. Sherrill agreed to round up experienced city managers and city engineers who would be willing to serve as majors and lieutenant colonels in the Quartermaster Corps. These men would become utilities officers on the staffs of corps area and post quartermasters. Sherrill made rapid progress. “We have got a surprising number of acceptances,” he told Groves on 28 January. “We will be ready in a few days.”127 With this assurance Somervell prepared to tell the corps areas that city managers were on the way.

The news broke on the 29th, when Groves announced to a meeting of corps area quartermasters: “These camps are big cities, and ... we should have commissioned City Managers and City Engineers, who have managerial capacity.” Fifty such officers would soon be available, and, said Groves: “We realize that when we send them out, that under present regulations, Post

Commanders or Post Quartermasters decide which Officer will be the Utility Officer, but we expect that when an experienced man of this character is sent there that he will be used for that purpose.” This announcement brought a flurry of excitement. Brig. Gen. James L. Frink of the Fourth Corps Area was on his feet immediately. “Regardless of rank?” he exclaimed. Groves replied that the new men would be junior to the post quartermasters. In a moment Frink was back:– “It should be thoroughly understood that, when these boys come down in the Fourth Corps Area, I am the boss.” Several other corps area quartermasters questioned whether men used to dealing with city politicians would “play the game the military way.” At this point Somervell joined the discussion. “I do not know how much experience any of you have had in politics,” he said, “but I have been exposed to it for a considerable period of time, and if you can get along with a bunch of politicians—well, getting along with a bunch of Army officers is just ‘duck soup’.” After giving the assembled officers a few facts of political life, he went on to remonstrate: “Now, I gathered from what General Frink said that we were trying to ram something down your throats. Quite the contrary. What we are trying to do is to get the best people we can find in these United States to do that job for you.” At the end, the corps area men seemed mollified.128 The following day Groves wrote Sherrill that the corps area people were “unanimous in their approval and appreciation of the plan.”129

Meanwhile, on 23 January, the new head of Repairs and Utilities, George F. Lewis, had arrived on the scene. Son of the inventor of the Lewis machinegun, he was a 1914 West Point graduate, a classmate of Somervell. Commissioned in the Corps of Engineers, he had served with the Punitive Expedition into Mexico and with the First Division in France. Resigning from the Army in 1919, he afterward held positions as vice president and treasurer of the Anderson Rolled Gear Company; president and treasurer of Foote, Pierson and Company, Inc.; town commissioner and public safety director of Montclair, New Jersey; and managing engineer of the J. G. White Engineering Corporation. With his military background and his wide experience in management, engineering, and construction, Lewis was particularly well qualified for the job of reorganizing the Army’s repairs and utilities work.

While awaiting appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the Quartermaster Corps, Lewis looked into the existing setup. He found that repairs and utilities was commonly regarded as one of the worst headaches in the Army. Although The Quartermaster General was legally responsible for all post maintenance, successive Chiefs of Staff had insisted that commanders on the ground have complete control. As a result authority vested in the corps areas, and post quartermasters took their orders from station commanders. Diverting maintenance funds to pet projects of local military authorities was an almost universal practice. Because few enlisted specialists were available and funds were seldom sufficient for hiring civilians, post quartermasters had to draw men from the line. Gunners helped run sewage plants,

infantrymen fired furnaces, and tankers patched roofs and improved roads. Lewis noted other weaknesses. Budgetary controls were lax and spending was unscientific. There were no uniform procedures of cost accounting, stock control, or work load measurement; no regular inspections and reports; and no systematic studies of personnel utilization. Technical manuals and bulletins were few and out of date. Complicating the maintenance task were the temporary character of the new camps and the speed of construction. Already, some roofs were leaking and some floors were beginning to warp.130

One of Lewis’ first assignments was to work with Groves on the city manager proposition. Unlooked-for complications endangered the plan. Word that city officials would receive direct commissions prompted inquiries from congressmen. Candidates appeared whose chief recommendation was political backing. Groves made it clear that there would be no patronage appointments. He told one congressman that the choice of city managers was up to Sherrill. He informed another that no commissions were available.131 Finally, he adopted a standard reply: “We’re anxious to get men who are city manager experienced, and these men aren’t, that’s all.”132 A more serious difficulty arose when Sherrill submitted his recommendations. Somervell had asked for men who had successfully managed cities of at least forty or fifty thousand. Sherrill’s list named many who did not fill the bill. One man, recommended for the rank of lieutenant colonel, had managed a town of 4,700 since 1921; another candidate for a lieutenant colonelcy had once run a town of 10,000 but had been out of work since 1934. Somervell let Sherrill know that he was “quite surprised to learn that so many of the individuals recommended were not in fact eminently successful in private life.”133 Only fifteen of the fifty men Sherrill had named seemed qualified for commissions. Lewis regarded Sherrill’s effort as a failure.134 “We were,” said Groves, “possibly a bit misled by Colonel Sherrill’s initial optimism.”135

While reviewing applications forwarded by Sherrill, Lewis combed the Army Reserve lists. For days he worked in the Military Personnel Branch of Gregory’s office, studying the files. His efforts were rewarding, for he turned up thirty-three likely prospects, among them the city manager of Dallas, Texas, the city engineers of Elyria, Ohio, and Mamaroneck, New York, and the chief public works engineer of St. Paul, Minnesota. There were also engineers and officials of telephone and electric companies. Called to active duty early in March, these Reservists went to the new camps and cantonments and to Repairs and Utilities Branches in the zones.136 Pleased with their performance, Lewis later

wrote: “Our Army was dependent on our reserve and National Guard forces for trained and skilled personnel and they should be given credit for the fine material they supplied.”137

After receiving his commission on 11 February, Lewis concentrated on plans for reorganizing the Army’s maintenance system. For the next few weeks his calendar was crowded with appointments. He called on William H. Harrison in the new Office of Production Management and on Comdr. Thomas S. Combs in the Bureau of Yards and Docks. He consulted two vice presidents of the Western Union Telegraph Company and the works manager of Standard Oil of New Jersey. He talked matters over with members of G-4, the Bureau of the Budget, and OQMG. After studying other maintenance setups, in both industry and government, Lewis took a closer look at his own. By early March he was ready to offer Somervell some concrete suggestions.138

Lewis proposed to bring all repairs and utilities under Construction Division control. Post utilities officers would be appointed and relieved, not by the corps area commanders, but by The Quartermaster General. The supervisory functions exercised by the corps area quartermasters would be transferred to the zones. Estimates would be prepared by post utilities officers and zone Constructing Quartermasters. Corps area and station commanders could concur or comment on these estimates but could not disapprove them. The bulk of the funds appropriated for maintenance would be allotted by The Quartermaster General directly to the post utilities officers. The meaning of Lewis’ proposal was clear—local commanders would lose their power.139 If the plan was logical, it was also revolutionary.