Chapter 10: Planning Ahead

“Anyone may be excused for being defeated,” said Somervell in December 1940, “but he certainly can have no excuse for being surprised.” He intended to foresee developments and to be prepared to meet them. World conditions being what they were, a second, larger building program seemed inevitable, and he would plan accordingly.1 Soon after taking charge of the Construction Division, he put the question to his staff: what would increasing the Army to 4 million men mean in terms of sites, engineering, personnel, materials, and so forth.2 Thorough preparations, clear responsibility, sound policies, workable procedures, and a strong organization, ready when the need arose—these were Somervell’s goals. Hartman had cherished similar goals but had been unable to achieve them. Commanding far greater support than his predecessor, more flexible and more persuasive, Somervell, in large part, succeeded.

Inspector General Peterson, Somervell’s friend and sometime collaborator, started the ball rolling. On 23 December 1940, he wrote General Marshall:–

With the world situation as it is today, no assurance can be given that within a year the War Department will not be undertaking another major housing program. It seems expedient that steps be taken to provide for such a condition, to prevent a recurrence of the major difficulties that have been experienced with the present program, and to insure maximum economy consistent with rapid construction.

Peterson suggested a line of action. The War Department would forecast its requirements and translate them into terms of projects. It would choose sites acceptable not only to users but to builders as well. It would improve standard layouts and revise structural plans in light of recent experience. It would perfect purchasing methods and establish better labor relations. It would develop a more forward-looking organization. Site plans, specifications, estimates, bills of materials, and even personnel assignments would be worked out in advance. Somervell would be all set, ready to call for lump sum bids, when orders came to build.3 As proposed by Peterson, the idea gained adherents rapidly. Long-range planning—“advance planning” in Armyese—became a cooperative endeavor, embracing many different activities and producing many needed reforms.

Advance Planning: Camps and Cantonments

Additional troop housing was the first planning objective. Meeting on 30

December at General Marshall’s request, Reybold, Twaddle, Peterson, Gregory, and Somervell, together with Brig. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, who headed WPD, charted a course of action. General Twaddle as G-3 would prepare a schedule of prospective camp requirements for each corps area, giving the type and purpose of each post, the strength and composition of its garrison, and the priorities that would govern construction. Somervell would confer with NDAC on procedures for purchasing materials and with Labor Secretary Frances Perkins on labor policies. On the highly important question of sites, the officers believed the first step ought to be a statement of “general requirements.” All agreed that Somervell should take an active part in selection. Accordingly, they adopted a new procedure: G-3 would mark out general areas; Quartermaster officers would then “make a thorough field reconnaissance with a view to developing more specific locations and for the purpose of reporting upon the advantages and disadvantages of alternate sites, insofar as engineering and structural requirements are concerned”; this information would go to corps area and army commanders “for further investigation and final recommendation.” Once sites were firm, detailed construction planning would commence. The conferees opened the way for further innovations by proposing that all War Department construction policies “be thoroughly reviewed and brought up to date.”4

Encouraged by the results of the meeting, Somervell pushed ahead. One after another he issued orders to Colonel Leavey: draw up criteria for selecting camp sites; begin figuring housing requirements for another million men; start revising standard plans and layouts; consider using brick, tile, and other products excluded by the original specifications. He asked the Bureau of the Budget to add $15 million for engineering surveys to supplemental estimates which soon would go to Congress. He conferred with representatives of NDAC and OPM. He probed into the labor situation. Although progress on most fronts was good, on some it was poor. The Budget turned down the $15-million request. No solution to labor relations problems was in sight.5 Somervell was undismayed by these difficulties; sooner or later, he would overcome them.

One of his first tries was remarkably successful. In conversations with Donald Nelson of OPM, he stressed the advantages of stockpiling lumber. The Army could accumulate lumber gradually, entering the market when prices were low and spacing orders to help maintain production. There would be time for proper drying. Most important, reserve stocks would stand ready against sudden demands. On 15 January, Nelson recommended that the Construction Division stockpile half a billion board feet. Within 24 hours Somervell had the General Staff’s approval.6 By the 30th OPM was demanding to know “rather quickly”

types, quantities, sizes, and destinations.7 Anxious for the experiment to succeed, Somervell went slowly. Three weeks would go by before he made his first purchase.

In the Engineering Branch, the center of planning activity, January was a strenuous month. Developments proceeded rapidly, as Colonel Leavey rolled up his sleeves. Intensive review of the 700-series plans resulted in numerous changes. The technical staff altered details, refigured stresses, and rewrote specifications. It also prepared new drawings for several types of buildings and issued bulletins for use in planning roads and sewage treatment plants. During January Leavey signed 23 circular letters, nearly half the monthly total for the entire division. A study group investigated commercially available prefabs. The CQM at Camp Polk tested eight experimental barracks, four of steel, two of masonry, and two of hollow tile.8 Somervell announced that Leavey was creating a special unit to weigh “all these suggestions that have been made with regard to tile buildings, steel buildings, plastic buildings, and every kind of building you have ever heard of.”9 In the midst of these preparations, criteria for camp sites received first attention.

On 26 January, in an 8-page letter to the zones, Somervell detailed new criteria. After outlining military requirements for camps to accommodate at least 30,000 men each, he took up items of interest to the Construction Division—climate, topography, geology, soil conditions, labor, transportation, real estate, and utilities. These matters would receive careful investigation. For every site surveyed, field parties would furnish full particulars on terrain, subsurface rock, natural drainage, flood levels, vegetation, real estate values, availability of adjacent tracts, location of railways and highways, the size of the local labor force, the amount of housing in the area, and more. Water supply, sewerage, electrical power, and fuel would get especially close attention. “Too much stress cannot be laid on the question of utilities,” Somervell wrote. “Past experience has shown that where original estimates have been greatly exceeded in actual construction, the failure to properly study in advance the conditions affecting the design of utilities has caused most of the deficits.” Groves’ yardstick of one hundred gallons per man per day would be the gauge for water supplies. Survey teams would cover all nearby sources, including reservoirs, streams, lakes, and springs. They would measure ground water levels and investigate the cost of drilling wells. Where treatment plants, pumping stations, and connecting lines would be necessary, they would fix locations and estimate costs. They would take equally great care with other utilities.10

The site selection machinery soon went into motion. In his letter of the 26th, Somervell directed zone Constructing Quartermasters to begin work at once. He enclosed a map showing general areas G-3 had designated for eighteen

Experimental steel barracks

triangular division camps. The zones would select three sites desirable from a construction standpoint in each of the G-3 areas and submit their findings to corps area commanders. On the 27th Reybold alerted commanding generals of armies and corps areas: reports from the zones would soon be coming to them. Boards of officers, to be appointed by corps area commanders and to include a zone Constructing Quartermaster, a Medical officer, an Engineer officer, and a representative of the army commander concerned, would then make followup investigations. The boards’ recommendations would go to the army commanders, who would forward them with their comments to the War Department for final decision.11 Explaining the procedure to a meeting of corps area quartermasters late in January, Somervell expressed the hope “that by this new system we won’t have to build these camps on places where rock is a few inches beneath the surface and where we have to blast out entire sewer and water lines for a population of 30,000 people.”12

Investigations were soon under way. The first zone Constructing Quartermaster to report progress was Colonel Green. On 31 January he informed Leavey that maps of general areas in the Fourth Zone were under study and survey teams were at work. A few days later Casey heard from Major Vandervoort that engineering firms from Ohio and Kentucky were exploring sites in the Fifth Zone. During the first week in February Major Hayden inspected a

tract in southern Illinois and Colonel George began the search for sites in California and Washington. By the end of the month, field parties had surveyed most of the general areas originally named by G-3 and were visiting ten others recently designated for antiaircraft firing centers and armored division camps. Meanwhile, corps area boards were beginning to function.13

The new procedure, involving more people and moving more slowly than the old, increased the chance of information leaks and gave interested parties more time to bring pressure to bear. Both Reybold and Somervell had cautioned investigators against publicity of any kind, but with survey teams scouring the countryside, questioning chambers of commerce, and talking to local officials, rumors began to fly. One of the first serious leaks occurred on 2 February, when the Douglas, Arizona, Daily Dispatch blazoned the headline:– “Some City in the Southwest Will Get New Cantonment, Says Colonel Winston, Investigating Douglas.”14 Winston, a member of a corps area board, had told officials at Douglas that his was a fact-finding expedition, nothing more, and had pledged them to strictest secrecy. Nevertheless, someone talked. The article in the Dispatch indicated that the Army was about to build more camps. Other papers picked up the item. General Reybold warned the field that publicity would being pressure on the War Department and members of Congress.15 But keeping secrets proved impossible.

Neither in 1917 nor in 1940 had so many letters, resolutions, and petitions flooded Congress and the War Department and so many delegations descended on Washington urging particular sites. Citizens demanding camps for their communities besieged Capitol Hill. Pressure on the Chief of Staff was extremely heavy. “As long as this agitation exists,” one sympathetic Senator told General Marshall, “there will be hundreds of letters received in your office and my office demanding that something be done about the situation.”16 Appearing before a Senate committee in April 1941, the Chief of Staff referred to the investigations going forward under Reybold and Somervell’s direction. “They have been at that for three months,” he said. “They have had me involved, it seems, with every chamber of commerce in the United States in one way or another. I am not very popular, I might say.”17 To divorce site selection from politics was immensely difficult; but Marshall attempted to do so, insisting that location of training camps be based “on purely military needs.”18 Among those who received one of his polite but firm refusals was no less a personage than the Senate Majority

Leader Alben W. Barkley. Barkley took Marshall’s explanation in good grace, and so did most other legislators.19 A few continued to press. When one Senator implied that the Army was discriminating against some states, Marshall assured him “that such is not the case and that the War Department is motivated solely by the desire to proceed on the basis of efficiency in obtaining the maximum amount of training in the shortest possible time.”20

If political pressure could not bring the Army to an area, public opposition could sometimes keep it out. In May 1941, for example, G-3 designated two general areas for mountain and winter warfare training centers. One was near West Yellowstone, Montana, on the edge of the national park. Zone and corps area groups surveyed the area and settled upon a site which was in many ways ideal for both construction and training. They failed to note that nearby Henry’s Lake was a refuge for the last remnant of trumpeter swans in North America. News that the Army intended to build a camp near the bird sanctuary provoked angry protests.21 Secretary Ickes informed Stimson of the “violent criticism ... brewing among wildlife interests and nature lovers” and appealed for abandonment of the site. “To install a training camp in the vicinity of Henry’s Lake, with artillery practice as one of its principal activities,” he wrote, “is certain to endanger the future existence of these splendid birds. ... From a wildlife standpoint, no more objectionable selection could have been made in the entire Rocky Mountain region.”22 Stimson at first refused to give up the site, but the opposition of naturalists and bird lovers at length caused him to yield. The Army abandoned West Yellowstone.23

While site surveys were in progress, Somervell focused on other aspects of long-range planning. Emphasizing that site selection was “just a part of the job,” he stated:–

I hope we will ... also [be] able to lay out the work, complete the plans, so that when the time comes for construction, if it ever does come, we will have completed plans ready and give them to the contractors and tell them to go to work and not just hand out a piece of paper and say, “Here are the plans—let’s see some buildings on the lot next week.” We have found ourselves in that predicament before and we are now trying to get away from that and want to get the work laid out in a systematic and orderly way.24

Experts in many fields participated in this effort. In the Legal and P&E Sections, Majors Jones and Wilson worked out innovations in contracting and procurement. Major Casey, who became chief of Design and Engineering late in January, directed a large and able staff in planning tasks. Bergstrom was his key adviser on architectural matters; Boeckh, on estimates. Leon H. Zach, a Harvard-trained landscape architect and former associate of Olmsted Brothers, who joined Casey in February,

master-planned site development. While he followed closely the work these men were doing, Somervell tackled a job on his own.

On 11 February, the day before the House opened hearings on the big deficiency appropriation bill, he made a second bid for a $15-million engineering survey fund. In a strongly worded memorandum, prepared for Gregory’s signature, he reminded General Moore that the money would provide “plans of critical importance to the Nation’s defenses.” Somervell referred to the international situation and the need for having construction plans “ready for instant action.” For years, he pointed out, the Corps of Engineers had received funds for long-range planning of civil projects. He attributed the Corps’ ability to carry out construction “in an efficient and economical way” to “this very businesslike and commonsense” procedure. Should not the same procedure be followed on highly important defense projects? Gregory signed the memo and sent it to Moore by special messenger.25 But nothing came of it. When Harrison telephoned later that day to inquire about the budget, Groves told him the $15 million was out. “Is that final?” Harrison asked. “That’s the way we have to present it to Congress,” Groves replied, “and we are not allowed to mention the fact that it has been trimmed unless we are asked and I don’t know whether General Somervell is going to get asked or not.”26

Whether by chance or prearrangement, Somervell was asked. Representative D. Lane Powers of New Jersey put the question: “Do you have any funds for planning jobs?” Somervell replied:– “No sir. The whole essence of this thing is to have proper plans. In other words, if we could have had a small sum for plans prior to this time, I think I can say conservatively that we would have saved $100,000,000.”27 This statement was to cause Somervell some embarrassment. The press misquoted him as having said that the hundred million would have been saved had he, rather than Hartman, been Chief of Construction at the start of the program. Three months later he was still trying to correct this erroneous impression. But the statement led to other, happier results. The House concluded and the Senate agreed that Somervell should have funds for advance planning. The supplemental appropriation voted in March gave him the $15 million—an important gain toward planning goals.28 Meanwhile, there were other gains.

Stockpiling of lumber commenced on 24 February, when Major Wilson placed orders for deferred delivery of 95,150,000 board feet. Fifty-one vendors shared in the award; they agreed to process the lumber and hold it in their yards for shipment after 1 May. Their average price, $26.41 per thousand, was well below the average of $33.25 for current delivery which Wilson paid during February. Market conditions being favorable, Wilson continued to buy. In a

few weeks he had obligated over $7 million for a stockpile of 265,155,550 board feet. At that point Somervell called a halt. A quarter of a billion board feet would fill 65 percent of known future requirements. With plans for further construction still nebulous, he hesitated to build the reserve higher. The accumulation of a second stockpile could wait until fall. Meanwhile, the division had insurance against a serious shortage.29

Changes in the standard lump sum agreement raised hopes for a return to conventional methods of contracting. The lump sum form originally adopted for emergency work carried the usual damages clause, which penalized contractors for delays. Most firms were understandably reluctant to bid competitively on defense contracts containing this clause. A further deterrent was the absence of an escalator clause providing for adjustment of the contract price should materials and labor costs rise. In February 1941, at Somervell’s direction, Major Jones set about liberalizing the contract. Assisting him in this work was Joseph P. Tanney, his principal civilian aide. The going was hard, for there were various legal angles to consider and numerous objections to overcome. After soliciting opinions widely—from OPM, the AGC, the Bureau of Yards and Docks, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Under Secretary’s office, Jones and Tanney came up with the following ideas: an escalator clause for long-term contracts; a clause exempting contractors from payment of damages when delays resulted from priority regulations; a more liberal policy on granting extensions of time; and lower damages rates. Patterson gave the necessary approvals.30 Whether contractors would compete on these terms and submit reasonable bids remained to be seen. Somervell, apparently, thought they would. “Doing jobs on a lump sum basis,” he confidently declared, “that is our policy.”31

“Of course,” Major Casey commented, “all of this work is planned to be done on the lump-sum basis and is going to require the preparation of plans and specifications for soliciting bids on the work.”32 Completing the revision of the 700 series was, hence, his first objective. During February and March of 1941, Casey and his staff made innumerable changes in the Quartermaster drawings. On the whole, the new designs were a decided improvement over the old. Heavy timbers and durable roofing materials made for stronger, more lasting structures. The addition of screens, clothing hooks, and balustrades assured troops greater comfort and safety. Substitutions, such as shellac for aluminum paint, promised savings in critical materials. Omission of skirting, “aqua medias,” and termite shields made possible substantial savings in funds. Standard station hospitals, widely considered as firetraps, were equipped with fire alarms, sprinkler systems, and draft stops. Hundreds of other changes corrected and

refined the 700 series.33 By April Casey had prepared lithographic prints of the revised drawings. Continuing his review of the plans, he said, “We don’t feel at any time they are finished to the last word.” Suggestions for further “improvements and economies” were always welcome.34

As Casey revised the drawings, he opened up specifications “to permit alternative types of construction.”35 For several months, he and Bergstrom explored the uses of masonry, tile, cinder blocks, plaster, and stucco and tested many types of prefabricated buildings. Their findings took the form of recommendations. They suggested, first, that the Army adopt a plan for two-story hospitals of fire-resistant materials; second, that tents give way to portable prefab huts; and, third, that sturdier materials come into competition with wood. While these proposals gained acceptance in principle, two of them were impracticable during the defense period. Detailed plans for semipermanent hospitals were not complete until December 1941. Money to convert tent camps into hutments did not become available until early 1942. The rule that all changes in standard plans had to clear G-4 at first blocked moves to let field officers substitute other products for wood. At length, with General Robins’ help, Somervell persuaded Reybold to rescind the ruling. In April 1941 the construction services received authority to deviate from standard plans. Although wood continued to predominate, other products found a growing market in the Army program.36

While the 700 series was undergoing revision, a new set of plans was in the making. Early in January Leavey discovered that the standard 63-man barracks was, by reason of its size, ill suited to many Army units. To illustrate, each infantry heavy weapons company had to have four such barracks, because these companies were slightly too large for three. Of the 81 companies in a triangular division, 51 fitted more easily into bigger barracks. Going into the problem, Casey found that a switch to a larger structure would not only reduce the number of barracks but also pare the size of cantonment areas and shorten roads and utility lines. He lost no time in having drawings prepared. Plans for a 74-man barracks were among the first in the new 800 series.37

Completed during the spring of 1941 by Bergstrom and his staff, the 800 series drawings were markedly different from the old 700’s. Structures were stronger, utilities more elaborate, and quarters more spacious. Warehouses were larger, and mess halls were arranged for more efficient service. Better ventilated, better insulated, and equipped with better heating systems, the buildings

incorporated scores of new features, ranging from rat-proofing in kitchens to exit lights in recreation halls. Conferring with representatives of OCE on designs for Air Corps stations, Casey stressed the following advantages of the 800 series: first, barracks were sized to fit most Army units; second, buildings were safer, sounder, and more livable; and, third, while the cost of individual structures would run higher, the cost of complete installations would be “about the same as under the 700 series.” He did not concede what many thought was true—that facilities built to the new designs would be semi-permanent rather than temporary.38

The new drawings had their critics and opponents. “Unnecessary,” “a mistake” were typical comments of regular Quartermaster construction officers. Such changes as were desirable could have been made in the 700’s, they contended, and all the features added to the buildings did not compensate for the discarded “aqua medias.”39 Veteran employees of the Engineering Branch, alluding to Bergstrom’s home state, scathingly referred to the 800 plans as “California earthquake-proof drawings.”40 Even Leavey acknowledged that there were “too many ‘long life’ precautions” and “too much use of first grade or ‘best quality’ materials for temporary construction.”41 The Chief of Engineers was lukewarm toward the plans. Opposition from OPM threatened for a time to block General Staff approval of the series. Noting that the blueprints called for many uncommon and outsized lengths of lumber, Nelson protested that deliveries would be slow and that carpenters would waste a great deal of time and material sawing ordinary boards to fit. By yielding a little, Somervell overcame Nelson’s objections. Though still preferring the rigid frames made possible by extra-long lengths of lumber, he agreed to include alternate specifications providing for shorter lengths in areas where hurricanes and earthquakes were not likely to occur. This concession opened the way for early approval of the series. Used sparingly on going projects, the 800 plans were ready for the next expansion of the Army.42

New site plans and layouts developed by Zach were superior to the originals. Detailing the “motivating factors” which influenced his thinking, Zach wrote:– “Efficiency of operation, usefulness of the project for its particular phase of troop training, must of necessity take first place. A strong second place, however, was given to economy of construction, and every effort was continually made to consolidate functions and to compact areas to the utmost.” Assuming the role of a city planner, he first determined his clients’ requirements. Discussions with troop commanders revealed the need to locate cantonment areas no more than half an hour’s march from small arms firing ranges. Discussions with The Surgeon General led to improvements in hospital layouts; talks

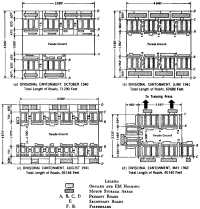

Chart 11: Progressive Improvements in Divisional Cantonment Layouts

Source: Leon Zach, “Site Planning of Cantonment and Community Housing,” Civil Engineering, August 1945, pp. 364-65.

with the Provost Marshal General, to schemes for special lighting and fences. Having satisfied the users’ needs, Zach considered construction costs. “The real estate promoter who built houses and sold properties on only one side of his streets would soon go bankrupt,” he reasoned. With that thought in mind, he proceeded, through successive revisions of typical layouts, to reduce roadage at divisional cantonments by 44 percent and graded areas by 25 percent. (Chart 11) Applying the same method to airfield cantonments, he reduced graded areas by 43 percent and roadage by 51.6 percent. He effected similar economies in water and sewer lines.43 His fresh approach to an old problem produced spectacular results.

A contribution toward better planning, made by Major Boeckh, took much of the guesswork out of building estimates. During the spring of 1941, Boeckh rounded up 70 or 80 qualified engineers and introduced his own copyrighted estimating system.44 Somervell, who called Boeckh “the best estimator in the United States,” described his method:–

Briefly this system consists of finding the unit costs of the materials that go into these various. ... [structures] by getting quotations from the various parts of the country. ... To that ... we add the cost of labor for the erection of the units that go into these various types of structures. Having done that, we establish what is a base price, a zero price. Then, with fluctuations in the price of materials and the price of labor, we establish an index for various parts of the country.

This index enabled the Engineering Branch to forecast with a high degree of accuracy the cost of building any structure anywhere. Owing to Boeckh’s generosity, the Army paid nothing in the way of royalties for a service which had more than twenty thousand commercial subscribers.45

By early May 1941 reports of site investigations were arriving in the War Department. Many locations were recommended—several in each of the general G-3 areas. The task was to choose among them. After study by G-3 and G-4, the site reports went, first, to The Surgeon General for comment and, then, to The Quartermaster General for review. Specialists in Casey’s office analyzed each report. Some of the recommended sites seemed unfit for construction. One such site was at Bend, Oregon; a heavy layer of lava rock lay just below its surface, and the nearest source of electric power was 50 miles away, on the other side of the Cascade Mountains. Many of the sites had one or two bad features which, though undesirable, did not warrant disapproval. As they O.K.’d these locations, Casey and Leavey spelled out the difficulties construction would entail. They noted, for example, that it would cost about $300,000 to remove high tension lines crossing a site near Marysville, California, and that subsurface rock would increase the sewer excavation costs at a site near Waco, Texas, by about $200,000. After medical and

construction officers had had their say, the General Staff made final selections. At General Marshall’s recommendation, Secretary Stimson approved nine new sites in May and fourteen in July.46

The time devoted to selecting these locations and the emphasis placed on engineering stood out in sharp contrast to the speed of earlier investigations and their neglect of builders’ problems. Between orders for preliminary surveys and approval of the first 9 sites, over three months elapsed. Another nine weeks went by before final agreement on the 14 additional sites. Zone and corps area boards had inspected more than 150 locations. In narrowing the choice, the boards had recommended and the Engineering Branch had reviewed 46 sites for camps and training centers. The twenty-odd sites finally chosen received approval for planning purposes only.47

Once he knew where the Army planned to build, Somervell took the next step forward—putting architect-engineers to work. Among the firms chosen to plan the new camps were some of the best and most experienced in the country. Somervell wished to negotiate exclusively with those who had already handled a camp project successfully. Patterson, on the other hand, believed that the War Department ought to spread its work among a larger number of contractors. The two agreed to compromise. The list of architect-engineers for advance planned camps included such firms as J. B. McCrary, Charles T. Main, Black & Veatch, and Leeds, Hill, Barnard and Jewett—all of which had previously designed a camp. It also included a number of newcomers to the program, all reputable though untried. The architect-engineers took fixed-fee contracts and agreed to work under Casey’s supervision. Within 90 days of award, Somervell hoped to be ready to build the camps by advertised lump sum contract.48

Writing in the July 1941 issue of The Constructor, Somervell assured his readers:– “If the need to house a larger army becomes apparent, construction can be started with maximum economy and minimum delay.”49 He had attained the first of his planning goals.

A New Approach—Munitions Projects

Keeping pace with plans for additional troop housing were plans for industrial expansion. The munitions program of 30 June 1940 had as its goal productive capacity to equip two million men and maintain them in combat. But since the War Department’s mobilization plans visualized a force of four million, the Army regarded the first wave plants as a down payment on preparedness. Thinking ahead to the next installment, Patterson in January 1941 appointed an informal committee of three to draw up a new plant program. Representing the “major production interests involved,” this group consisted of General

Harris, chief of the Ordnance Industrial Service, General Rutherford of the Assistant Secretary’s office, and General Somervell.50 Through the committee, Patterson hoped to avoid “some of the difficulties and delays encountered in the planning and execution of the first phase of this program.”51

Somervell, who shared this hope, believed it could be realized through careful planning, sound engineering, and the marriage of responsibility to authority. Compelled to follow his predecessor’s lead in building the first-wave plants, he sought to handle the second wave differently. He wished to map out the program well in advance of construction. He wished to have a strong voice in site selection. He wished to standardize plans and layouts and to design plants of more or less uniform size. Above all else, he wished to see the Construction Division, the agency responsible for building the plants, equipped with full authority to direct the work. Thanks to Patterson, he was now in a position to make his demands heard.

The first meeting of the informal committee took place on 5 February in General Harris’ office. Present, in addition to Rutherford, Harris, and Somervell, were two colonels and a major of Ordnance and two men from OPM. Most of the talk was of strategic boundaries, of distances from sources of raw materials, of proximity to centers of industry, and of availability of power and labor to operate the plants—topics of interest to Ordnance and OPM. But, whenever the opportunity presented, Somervell put in an oar. When General Harris mentioned that an appropriation was unlikely before summer and construction would therefore continue into the winter months, Somervell interrupted: “Have you got any money that you could let us have for planning and we could get these architectural engineers selected, get the plans drawn, and have something that will approach a real estimate. That is what we are going to do in the camps.” Harris replied that this might be arranged and passed on to other matters. Again, in the midst of a discussion of locations for small arms ammunition plants, Somervell broke in to ask if the designs would be of permanent or 5-year type. Harris informed him that 5-year would be standard. “Good,” said Somervell. While most of the topics covered that day did not directly concern him, Somervell had touched on two matters of importance to the Construction Division—advance planning and standardized design.52

On 12 February the committee met again. Somervell did not attend, for that was the day he went before the House Appropriations Committee to defend the overrun. Colonel Leavey, sent to represent the Quartermaster Corps, found himself in a room full of men from Ordnance, OPM, and the Assistant Secretary’s office. General Harris opened the meeting, reading off a list of locations that Ordnance had picked for twenty-two plants and the operators it had chosen. A lively debate ensued as to whether the program was too

ambitious. Madigan, there on Patterson’s behalf, suggested that the Army could plan a large number of projects well in advance, “without spending too much money,” and then build the ones it needed. Leavey listened while the others spoke, noting perhaps that Madigan was a strong partisan of advance planning and that Harris recognized the advantages of standardized layouts. Then he took the floor: “I would like to suggest a plan similar to what we have prepared for cantonment construction.” “What is that?” Harris asked. Leavey described at length the procedure he had worked out for selecting camp sites, how he had prepared engineering criteria, how the site boards went out to select locations, how “our people present these sites on a silver platter.” The others raised immediate objections. Madigan pointed out that Ordnance had had “fair success with sites.” Colonel Miles reminded Leavey that operating costs were “far more important over a continuing period of time” than construction costs. General Harris stated, “Well, I am not in favor of changing horses in the middle of the stream myself.” Leavey stuck to his guns, scoring in the following exchange:–

Mr. Madigan. Someone has to get down to brass tacks and say whether it is to be left to Ordnance or Quartermaster. I agree with Colonel Miles. The operating features must be considered.

General Harris. We are the landlords.

Mr. Johnson (OPM). Quartermaster shouldn’t be ignored, however.

Colonel Leavey. I think if we are going to build the plants we should have some voice in saying the spots they are going to be built on. Naturally, we would say that only after Ordnance has had their say. The constructor should know where he is going to build before he starts. ... If we can make plans ahead, we should take advantage of it. …

General Harris. What we have lacked so far is not having sufficient engineering analysis.

Colonel Leavey. That is what I am trying to offer.

General Harris. I see your point and we like assistance.

That the Quartermaster Corps would henceforth have some part in locating plants seemed fairly well assured.53

Establishment of a new organization for selecting plant sites soon confirmed this assurance. On 13 March 1941, following passage of the Lend-Lease Act, Patterson abolished the old War Department Site Committee, which had long reflected the Ordnance viewpoint. In its place, he set up the War Department Facilities Board, with General Rutherford as chairman. The other members were Brig. Gen. Oliver P. Echols of the Air Corps, Lt. Col. Theron D. Weaver of the Assistant Secretary’s office, and Generals Harris, Reybold, Robins, and Somervell. The board would, first, “investigate the necessity for additional productive capacity” and, then, submit a program to be financed with War Department and lend-lease funds. Finally, after considering recommendations of the Arms and Services and requirements of the Navy and other government agencies, it would select sites. Since four of the members, Reybold, Robins, Weaver, and Somervell, were Engineer officers, construction aspects of selection were likely to receive due weight.54

At a meeting on 26 March, the board

outlined its course. It would observe the strategic boundary and avoid unnecessary concentration. It would cooperate fully with OPM. It would investigate proposed sites thoroughly, considering such factors as estimated cost, labor requirements and supply, power, transportation, and housing. It would clear all projects and all sites with OPM before presenting them to the Assistant Secretary of War and the President for approval.55

So far the Army had done nothing to insure thorough engineering investigations of new sites, but this situation soon changed. On 5 April Patterson revised the procedure for locating plants. The Quartermaster Corps would survey proposed sites and the Facilities Board would consider only those Somervell had approved. By May Colonel Leavey had developed criteria for use by architect-engineers in reporting on proposed locations for Ordnance and Chemical Warfare projects. The new system was not infallible. Despite an unfavorable report by the Construction Division, General Wesson insisted that he had to build a plant at Crab Orchard, Illinois. This site, in a depressed area, had the backing of Sidney Hillman and, even more important, of Harry Hopkins, who evidently wished to please an intimate, ex-Congressman Kent E. Kellar.56 But such cases were rare. For the most part, locations for the secondwave plants, unlike those for the first wave, had the Construction Division’s approval.

So negligible had been the influence of The Quartermaster General in the design and layout of munitions plants that any change would have to be in the direction of increasing his powers—and there were many indications that a change was necessary. Blueprints were too long on operators’ drawing boards, and constructors marked time while plans underwent painstaking review by Ordnance. Even Knudsen, in OPM, remarked how long it took for drawings to reach the field. “It would seem to me,” he wrote Patterson, “that drawings of simple structures could be pushed ahead so as to get the contracting work done.”57 Ordnance excused delays by pointing out that the plants were large and complex and most engineers were relatively inexperienced in munitions work.58 But when plans for roads, utilities, and administration buildings were not forthcoming, this argument was hardly convincing. Observers noted that designs were neither uniform nor economical. Harrison stated that “construction costs of certain powder and TNT plants ... have disclosed rather wide variations due to details of design and to construction refinements.”59 One of Groves’ inspectors made “the alarming observation” that “the interpretation of safety requirements is different at almost every shell loading plant.”60 Still another practice of

Ordnance attracted unfavorable notice. Frequent expansions of projects, after construction had begun, complicated orderly planning and made necessary radical revisions in layout.61

Ordnance was reluctant to give the Construction Division a larger role in design, but Somervell persisted. Early in March Colonel Leavey approached one of Campbell’s assistants, only to be rebuffed: Ordnance provided the money and Ordnance would furnish the design, and “after this design was furnished it was not the function of the Quartermaster Department to change it in any respect.” Leavey replied that he could not accept such an interpretation and hurried to his chief.62 Challenging Ordnance’s stock statement about the complex nature of the plants, Somervell pointed out to Patterson: “Most of the construction involved in Ordnance plants is of the type daily encountered in industrial engineering. The most complicated structures in all of the work for the Ordnance Department are the power houses, concerning which that Department and its operating agents claim little knowledge.” After arguing at length that there was nothing complicated about the jobs and no excuse for handling them differently from other construction jobs, he stated, “This office and the industrial engineers whom it employs, or may employ, are in a position to make an important contribution to the design and construction of all these facilities unless the sciences of engineering and architecture are to be completely disregarded.”63 Patterson, partly won over, ruled that the Quartermaster Corps would design all facilities except the manufacturing buildings, though all plans would be subject to Wesson’s approval.64

Controversy was forgotten, as the Engineering Branch buckled down to work. Ordnance provided funds for advance planning a dozen plants, and Somervell hired experienced architect-engineers for the jobs. Leavey began to standardize plans and layouts. Lake City would serve as the model for future small arms ammunition plants, and plans for other types of plants would incorporate all recent improvements.65 The Construction Division was trying hard and Ordnance seemed appreciative. When General Harris appeared before a group of Quartermaster officers on 10 April, cordiality was the keynote. After Somervell had introduced him as “our best client,” Harris apologized for past delays. He told the meeting: “Cooperation is absolutely necessary and ...

this is the War Department as a unit in which we are all cogs. If there is anything that we are not doing we want you to say so and say so plainly. Let’s not have any misunderstanding arise and the passing the buck from one to another.”66

Designs for the second-wave plants were a triumph of cooperation. In

Lake City Ordnance Plant, Missouri

the interests of economy, all agreed that new facilities would be “somewhat less permanent” than the first-wave plants and that greater emphasis would be laid on curtailing construction costs.67 It remained for user and builder to translate these broad aims into detailed plans and specifications. Accordingly, on 26 May, General Wesson appointed a board of Ordnance officers to recommend “general layouts, together with types of construction and equipment to be used in these future plants.” The board submitted its recommendations on 6 June: substitute sheet siding for brick and tile; let trucks partly replace railroads in intraplant transportation; build mostly one-story structures; use fencing, lightning protection, and sprinkler systems sparingly; and employ standard plans whenever possible. Wesson passed the report on to Somervell, who was already at work on the same problem.68

On 17 June representatives of Ordnance, OPM, and the Construction Division met for an all-day conference on the second-wave plants. Among those

present were Somervell, Leavey, Casey, Harris, Campbell, and Harrison. Somervell opened the meeting with a call for coordination “in the interest of effecting economies of construction and increasing speed of construction.” He went on to present plans newly developed by the Engineering Branch. Ordnance accepted practically all of Somervell’s suggestions, and he, in turn, agreed to the proposals advanced by Harris and Campbell. The conferees then adopted certain general principles and procedures. Where new buildings would duplicate older ones, original plans and bills of materials would be used in order to save time. Whenever possible, however, additions to existing plants would be of temporary design and only “bare necessities” would be provided. Ordnance would submit schematic layouts of process equipment to the Construction Division for review and analysis.69 Continued cooperation seemed assured when the two services scheduled further meetings and Somervell agreed to establish a suboffice in Wilmington to work with the Ordnance office there.70

But all was not harmonious. On 3 March Somervell sent Campbell a note suggesting that contracting procedures were due for an overhauling. When the two men met a few days later, Somervell brought the subject up again. On the 12th he received a memorandum from Campbell defending the existing arrangement. Pointing out that the Construction Division had itself defined the position of Ordnance as “analogous to that of a client in private construction practice,” Campbell stated that the operator was “an adjunct of the Ordnance Office ... with all that implies.” The architect-engineer, under contract to the Quartermaster Corps, received from the operator “the basic and general plans and layouts of the work for the detailing of such, for the ordering of material, and for the actual construction of the plant by the constructing contractor.” Indeed, the architect-engineer had to regard the operator as his only source of information. The constructor, also under contract to the Quartermaster Corps, received his instructions from the architect-engineer. Ignoring the Constructing Quartermaster, Campbell wrote of the commanding officer: “He, as the representative of the owner for whom the plant is being built, with funds appropriated to the Ordnance Department for that purpose, is charged, and rightly so, with the duty of being head man at the plant.” Campbell pronounced the arrangement sound and asked Somervell if he did not agree.71

Somervell emphatically did not. There were, he insisted, two “more satisfactory methods by which the construction of ordnance facilities can be better prosecuted from the standpoint of efficiency, speed, and economy.” Under the first, he and Campbell together would select and contract with a design consultant, who would prepare basic layouts and designs in collaboration with Ordnance. The Construction Division would hire the architect-engineer, after considering the recommendations of the design consultant who would advise the

architect-engineer during construction. The division would also hire the constructor, apparently without reference to Ordnance. Under the second method, Ordnance would contract with the design consultant and the architect-engineer. Upon completion, plans and specifications would go to The Quartermaster General, who would then make a separate contract with the architect-engineer for supervisory services during construction and would hire his own construction contractor. Though Somervell favored the first method, he was willing to settle for the second. Both offered clear-cut advantages. “The division of authority and responsibility is more clearly delineated,” he argued, “and there would be but one boss of the construction activities in the field.” And since the interests of Ordnance would be safeguarded, the sending of a commanding officer to construction projects would be “inadvisable and not necessary.”72

Once Ordnance knew the tack Somervell was taking, it moved to head him off. On 29 March Wesson wrote to Patterson, “It is my matured judgment that the ends of economy and celerity of completion will best be met by entering into a single contract with a firm to cover management servicedesign consultant, equipping, operation, architect-engineering, and construction.” The contractor would usually sublet architect-engineering and construction work, in which case the subcontractors would be selected by the Construction Division and approved by Ordnance. But he might in some instances elect to do all the work himself. Ordnance would administer the contract titles dealing with management, design consultant services, equipment, and operation, while the Quartermaster Corps would administer the subtitles having to do with architect-engineering and construction.73 The setup proposed by Wesson was the same one Hartman had successfully resisted in 1940. Somervell did not learn what Ordnance was up to until the morning of the 31st, when Wesson read the memorandum to him over the telephone and asked for his concurrence. Not only did Somervell refuse to concur, he promptly declared war. He spent the rest of the day drafting an angry letter to Patterson. The gist of his argument was contained in the opening paragraphs:–

This office strongly objects to the method outlined by General Wesson, because it would be contrary to the National Defense Act, since it precludes the QM Corps from discharging the responsibility given it thereunder. In order to discharge its duties and obligations properly, the QM Corps must exercise direct control over all phases of the work entering into the construction of a plant. Where the prime contract includes operation and management, design consultation, architect-engineering and construction, to all intents and purposes, it is administered solely by Ordnance and no direct control by the QM Corps can be exercised. Such a situation would result in a waste of many millions of dollars, since the prime contractor is chosen primarily for his operating ability, and often has little or no knowledge and experience in matters involving design, engineering, and construction.

The whole effect of such a procedure, in addition to the objections just cited, would

be to leave this office with the responsibility for mistakes which might be made, and no authority to prevent such mistakes.

Somervell was not content to stop there, but went on page after page. He quoted liberally from the law and the Army Regulations to prove that Congress and the Secretary of War clearly intended The Quartermaster General to have all construction, not just the part of it that Ordnance deigned to give him. He stated that the Chief of Ordnance, “although not possessed of officers or staff skilled in matters of construction,” insisted on “placing the control of all this work in the hands of persons having no continuing responsibility to the United States.” He implied that operators were taking advantage of Wesson’s innocence. Unorthodox contracts were in use. Ordnance was approving insurance contrary to Patterson’s policies. Superintendents and engineers were receiving excessively high salaries. Some arrangements with utilities companies were questionable. Returning at last to Wesson’s proposal, Somervell wrote:–

The construction agencies of the War Department are a clearing house of information on construction practice and materials. All large organizations such as the War Department maintain engineering or construction organizations to carry out this part of their work. Unless there were a sound reason for this, the railroads, the telephone companies, public utilities, and other large concerns would not maintain such organizations. ... Following General Wesson’s reasoning, there is no need for such an organization. He submits nothing to support his statement. Although ex cathedra statements of this kind from the Chief of Ordnance are, of course, entitled to consideration, for them to be at all convincing some cogent reasons and, most of all, facts should support them. There is nothing in the program to date to indicate that the interests of the United States will be better served by officially sanctioning the practices cited above than by placing the construction work in line with customary practice and with the law which states that the Quartermaster General shall have direction of all work pertaining to construction.

He ended by recommending that Patterson tell Wesson to confine himself to operating the plants and to stay out of construction.74

Five days after Somervell’s outburst Patterson adopted the single contract. The Chief of Ordnance would choose a prime contractor, who would have responsibility for all work from designing a plant to operating it, and who would subcontract architect-engineering and construction. Ordnance and Quartermaster would “together negotiate and execute the contract,” but the Quartermaster would be responsible primarily for the parts pertaining to construction. The two subcontractors, the architect-engineer and the constructor, would be “selected and recommended” by the Quartermaster, “subject to the concurrence of the prime contractor.” Patterson was careful to state that The Quartermaster General would “supervise the construction of the entire project,” but whether that supervision could be effective under these circumstances was debatable. It appeared that the fight was over and that Ordnance had won.75

But Somervell would not be bested. After recurrent agitation against the single contract, he persuaded Patterson

to yield.76 On 14 July 1941 the Under Secretary abolished the single contract. The Quartermaster General would henceforth have “full responsibility” for choosing architect-engineers and constructors. Subject only to Patterson’s approval, Somervell would award separate contracts to these firms. Wesson would make arrangements with operators and approve plans and specifications. But he would have no authority for construction in the field. Somervell was at last in a position to control effectively the operations of architect-engineers and builders.77

It had been a hard fight, but Somervell had come out on top. He could reasonably expect that future munitions projects would present fewer engineering and construction difficulties than those built in the past.

A Stronger Organization

In an address before the annual convention of the Associated General Contractors on 20 February 1941, Somervell spoke of his “determination to make the Construction Division as competent an agency as exists in the Government.”78 In pursuing this objective, he spared no effort and shunned no opportunity. The big reorganization of December 1940 was followed by innumerable smaller ones. The division underwent a thorough housecleaning. Personnel shake-ups were an almost daily occurrence. Many new faces appeared and some old ones dropped out of sight. Dreyer recalled “a constant gyration in the Engineering Branch.”79 But Somervell knew what he was after—a construction capability second to none. He was aiming high. Whether he could hit the mark remained to be seen.

During the first half of 1941, new names appeared on the division’s roster of key personnel. Douglas I. McKay, who became Somervell’s special assistant, was a former police commissioner of New York City. John J. O’Brien, who replaced Colonel Valliant as chief of Real Estate, had been a top attorney in the Lands Division of the Department of Justice. Lt. Col. William E. R. Covell, who became Leavey’s executive when Nurse, at his own request, went to the Ninth Zone, was a retired Engineer officer, first man in the West Point class of 1915. There were two former employees of the New York City WPA—one was James P. Mitchell, afterward Secretary of Labor in the Eisenhower cabinet, who succeeded Brigham as head of the Labor Relations Section; the other was Oliver A. Gottschalk, who became assistant chief and later chief of the Accounts Branch. As Hartman’s men faded from the scene, Somervell brought in his own team.

Other noteworthy personnel changes took place in the Construction Advisory Committee. Seeking to remove all doubt of the committee’s impartiality, Somervell decided to enlarge its membership and to place an experienced military engineer at its head. General George R. Spalding, an officer of the highest reputation who had retired as G-4 of the Army in 1938, became chairman on 18 February 1941. Later that

month the appointment of Alonzo J. Hammond gave the group a membership of five. When Blossom resigned on 31 March, a victim of unjust criticism, Tatlow replaced him. General Spalding’s term was brief, possibly because he found Somervell’s methods distasteful, possibly because he clashed with the committee. Quite likely it was a little bit of both. Upon Spalding’s resignation in May Somervell brought in another retired Engineer officer, Maj. Gen. William D. Connor. The choice was a fortunate one. A distinguished soldier and a former superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, General Connor worked well with his civilian colleagues.80 From the time of his appointment until March 1942, the committee’s membership remained unchanged.81

Time and again, Somervell emphasized the importance of good leadership. At a conference with his principal assistants in February 1941, he declared:–

This is a world of people and as Napoleon used to say—I’m very glad he said it because I have repeated it two or three hundred times—“There aren’t any poor regiments; there are only poor colonels.” Think that one over if you are a boss. Everyone here is a colonel in a sense. Remember there are no poor sections, no poor branches, and no poor units—only poor section leaders and poor branch chiefs and poor unit chiefs.

Even as he worked to improve administrative procedures—to eliminate duplication, to shorten channels of communication, to couple responsibility with authority, and to limit the number of persons any one individual supervised—he kept coming back to the proposition that “personnel is the first thing.”82 One of his strongest efforts was a search for talent. Assessing the results, he stated late in April 1941, “Now we have got the best people you can get to do the job and nobody can do any better than the best.”83

While attempting to provide better leadership, Somervell expanded his administrative force. As recruitment accelerated, a bottleneck developed in the hiring of civilians. The situation seemed serious. By late winter an average of twenty-eight days was elapsing between the date requests went to the Civil Service Commission and the date new employees reported for work. Several branches were complaining of personnel shortages. On 7 March, 400 persons were awaiting appointments. When the delays continued, Somervell appealed to the Civil Service Commission for help. Commissioner Flemming disclaimed responsibility for the trouble and advised the Quartermaster Corps to mend its ways. First, said Flemming, Somervell should stop recruiting on his own. Second, and more important, he should deal directly with the commission instead of going through General Gregory’s office.84

Although Somervell showed little inclination to follow Flemming’s first suggestion, he welcomed the second. General Gregory’s control over appointments had not always worked to the advantage of the Construction

Division and was believed, in some quarters, to have contributed measurably to Hartman’s difficulties. No less an authority than the commission was now advocating that the division handle its own affairs. On 4 April, Somervell forwarded Flemming’s recommendation to The Quartermaster General. “This seems to me to be a very constructive suggestion,” he wrote Gregory, “and it could be put into effect immediately if your office ... would be willing to grant authority to the Construction Division to deal directly with the Civil Service Commission.” Somervell added that he had no wish to usurp any of Gregory’s powers and he pointed out that The Quartermaster General could still cancel any action taken by the Construction Division.85

About a month later, after “very careful consideration,” Gregory turned down the proposal. Although he wished to give his subordinates as much responsibility as possible, he held that “certain functions” could not be delegated to division chiefs. “I feel,” he explained, “that central control of personnel policies and management is necessary. Grades, classifications, and rates of pay should not differ too widely in the various operating Divisions of the office.” There had been delays, certainly, and some “creaking and groaning” of the hiring system. However, hundreds of employees had been added to the Construction Division since mid-December. If ever central control hindered the division’s work, Gregory would “be only too glad to consider very definite modifications.” Until then, the present arrangement would stand.86 Gregory’s decision could hardly have been otherwise. By late April the Construction Division had 2,933 employees as compared with 1,989 in all other divisions of his office.87 It was no easy matter to keep the tail from wagging the dog.

Somervell was furious. Making little effort to disguise his feelings, he drafted a reply. The Quartermaster General was a “disinterested” party, “remote from the scene of operations” and out of “direct contact with the work.” His control of appointments was preventing quick action in situations where success might “hinge directly on our ability to move fast.” “It is believed to be a generally accepted principle,” Somervell noted, “that an organization the size of the Construction Division, performing a definite type of function and not closely related to the parent organization, should be responsible for the appointment, training and supervision of its personnel.” After presenting evidence of “significant delays,” he declared, “It would not be an exaggeration to say that much of the lack of proper coordination which I find in various Branches of the Construction Division today is due to the present system of procuring civilian personnel.”88 Styer felt this reply went too far. Substituting his own more diplomatic version, he chided Somervell for “wasting time arguing.” Besides, he said, the Construction Division was not entirely blameless.89 That ended the

affair. Commenting afterward on the unsent draft, Groves stated: “This particular memorandum was indicative of Somervell’s attitude toward The Quartermaster General during the time that he was head of the Construction Division. Like most aggressive and brilliant leaders (and such he certainly was), Somervell resented control. He wanted to be independent and he was constantly working in that direction.”90

General Gregory continued to handle appointments of construction personnel, both civilian and military, and with success. By the end of June 1941, the Washington office had 3,210 civilians and 216 officers. Manning the field offices were 11,679 civilians and 966 officers. In addition, 16,183 persons were engaged in maintenance. At the close of the fiscal year, orders were in the works calling 452 Reservists to active duty. In the twelve months since the fall of France, the size of the construction organization had increased several fold.91 For the second big building program currently taking shape, it appeared to be adequate.

Despite its relatively large size and high level of competence, Somervell’s organization had a somewhat makeshift character, a certain make-believe quality. As one skeptical observer remarked, the new setup looked “very good on paper.”92 Viewed closely, it displayed major defects. Many of the men on whom Somervell relied most heavily—Engineer officers and industry bigwigs—were with him temporarily. During the summer of 1941, the exodus began. Among the first to go was Colonel Casey, summoned to the Far East by General MacArthur. A look at the zones was revealing. For all his talk of creating miniature Construction Divisions, Somervell had decentralized some of his functions only partially and others not at all. The transfer of leasing and maintenance work from the corps areas helped the zones but not enough. Intended to be copies of the Engineer divisions, they were pale imitations at best.

All things considered, Somervell had done well. His organization was a vast improvement over Hartman’s. What he did not and could not do was to build a stable structure in a few months time and to duplicate the Engineer Department within the Quartermaster framework.

The Building Trades Agreement

Among the hottest issues faced by long-range planners were those involving the construction trades. Problems of labor costs and productivity cried out for solution. Uniform policies on overtime and shift work, firm controls over basic wage rates, an end to strikes and disputes—these were musts in the War Department’s view. But prospects of achieving them were dim. NDAC policies aided organized labor. The unions, strong and growing stronger, wanted more, not less. Somervell, thinking, perhaps, of his own White House connections, showed little disposition to challenge Sidney Hillman or the AFL. During the early months of his regime, he won no real concessions from the building trades.

Soon after his appointment to the Labor Relations Section, Mitchell took up the question of overtime, weekend,

James P. Mitchell

and holiday pay. Working with him on the problem was Edward F. McGrady, former Assistant Secretary of Labor, who had replaced Major Simpson on Patterson’s staff late in 1940. In mid-January Mitchell prepared a study showing how much money could be saved by scrapping the local practices formula in favor of a universal time-and-one-half rate for work in excess of 40 hours a week. Of 44 projects studied, only 5 were working a regular 4o-hour week, and only 6 were operating on a straight-time basis on weekends and holidays. At 13 projects, workers were getting time and a half for over 40 hours and for Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays regardless of time worked during the week; at 20 jobs, they were getting double time. On these 44 projects alone, Mitchell figured the net saving would average out to $935,931 per week, or 1.4 percent of total weekly payrolls.93 McGrady passed the study along to John P. Coyne for consideration by the AFL Building Trades Department.

At Coyne’s request, a meeting took place in Patterson’s office on 24 January. Among those invited were Assistant Secretary of Labor Tracy, Maxwell Brandwen of Hillman’s office, a representative of the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks, and Mitchell. Coyne announced that he would ask the AFL Executive Council to “indorse a policy which would establish a 40-hour week from Monday to Friday and payment of time and one-half for all hours worked over 8 hours a day and Saturday, Sunday, and holiday work for all trades on all construction jobs in the country.” The announcement fell flat. As Mitchell pointed out, Coyne’s plan would “result in serious dislocation of normal practice” in the South and Southwest, where straight time was the going rate for weekend and holiday work, and might “bring about criticism from Congressmen and contractors in that area.” Besides, Mitchell said, “The financial saving, if any, on payroll costs would be negligible.”94 Madigan agreed with Mitchell.95 And another of Patterson’s advisers, Huntington Thorn, reported: “We are miles apart from the Building Trades for even President Coyne in his proposal ... would not consider altering the status of premium rates for Saturday and Sunday. As a result, we would be sticking our necks out in vain

were we to recommend what we think is a fair solution.”96 Patterson decided to let well enough alone, and on 8 February he so informed Coyne. For the next two months, Mitchell made no attempt to reopen the question. Quartermaster projects continued to pay premium rates according to local practice.97

Not so crucial as premium rates but nevertheless important was the question of shift work. Since November 1940 the Construction Division had reimbursed contractors for seven-and-a-half hours’ pay on the first shift, one-half hour being allowed for lunch on the employee’s time; the second-shift lunch period counted as time worked where this was local practice. Authorized only “under extraordinary conditions,” third shifts consisted of seven and one-half hours, including a half-hour for lunch counted as time worked; the pay rate on these “graveyard” shifts was one and one-fifteenth times the basic rate.98 Although Coyne had informally approved this arrangement, local unions had not ratified it.99

In April 1941, when it became apparent that continuous 3-shift operations would be necessary to expedite completion of small arms ammunition plants, Mitchell pressed for a firmer understanding. On the 22nd he approached Herbert Rivers of the Building Trades Department, who agreed to cooperate. On the 28th, accompanied by Rivers, Mitchell went to St. Louis to lay his proposal before the local unions. The conference was a failure. After most of the locals refused to go along with Mitchell, Rivers came out in favor of eight hours’ pay for seven and one-half hours’ work on all shifts. Under pressure for increased speed, Somervell accepted Rivers’ alternative on 1 May. The new shift policy, which gave workers one-half hour more pay on first and second shifts than the Army had advocated, applied at small arms ammunition projects and other urgent Ordnance jobs.100

Faced in the midst of the Ordnance speedup with the prospect of more jobs ahead, Somervell recognized the need for cutting labor costs. So far, basic wage rates had been kept from spiraling. But Mitchell and his staff, noting that more requests were coming in for raises at jobs in progress, feared they could not stem the tide much longer. The trend on overtime rates was to substitute time and a half for straight time in the South, double time for time and a half in the Middle West, and double and a half for double time in the Northeast. Unless wages were stable, labor pirating would be uncontrollable. Moreover, ruling on so many requests for pay boosts and overtime premiums placed an enormous administrative burden on the Labor Relations Section. Under the circumstances, Coyne’s earlier proposal now seemed advantageous.101

On 9 May Somervell asked Sidney Hillman to modify NDAC labor policies by substituting Coyne’s formula for the local practices rule. Hillman suggested instead that the unions and the federal construction agencies negotiate. Contractors would have no part in the talks. One reason for excluding them was that the government, not the contractors, was paying the bill. Another was that the industry, broken up into at least three interest groups (builders, heavies, and subcontractors), had no single spokesman. Informal talks were soon under way. After sounding out union officials, Mitchell concluded that an understanding was possible. By the first week in June, Hillman thought the time for a formal meeting had come. Somervell promptly drew up an agenda. Included as topics for discussion, along with basic wages, overtime, and shift-work rates, were predeterminations, initiation fees, and a no-strike pledge.102

To representatives of the War and Navy Departments, Maritime Commission, Federal Works Agency, and AFL assembled in his office on 23 June, Hillman stated that the purpose of the conference was to agree to a “uniform policy and procedure” about wages, overtime rates, working conditions, and other matters touching labor relations. He then threw the meeting open to discussion. Several of the conferees recommended additions to Somervell’s list. Colonel Lorence of OCE suggested two: subcontracting of mechanical items and use of WPA labor. Richard J. Gray of the Building Trades Department proposed a ceiling on the number of civil servants in construction jobs. Others talked of the need for clearer policies and better coordination. Then, George Masterson of the Plumbers and Steamfitters’ union blew the meeting wide open, by declaring that all labor difficulties on defense jobs stemmed from the failure of government agencies to live up to NDAC policies. At that Coyne stepped in to propose that a committee try to reach an understanding. There was general assent. Each government agency named a man to meet with representatives of the Building Trades on 25 June. The conference then adjourned.103

The result of the committee’s work was a document, Memorandum of Agreement Between the Representatives of Government Agencies Engaged in Defense Construction and the Building and Construction Trades Department of the American Federation of Labor, better known as the Building Trades Agreement. Signed on 22 July, the agreement took effect on August 1st. Although it omitted some of the proposed topics, it included all the “musts.” It eliminated double-time premiums in favor of a universal time and one-half rate as suggested by Coyne in January 1941. Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays would remain premium days regardless of the time worked during the preceding week. Principal sources of supply would be the basis for predeterminations; thus rates for projects in rural areas would be those prevailing in the nearest large city. Once determined, rates would remain

fixed for the duration of the job but no longer than one year. Second and third shifts would work seven and a half hours for eight hours’ pay, but first shift workers would not receive this bonus. The government agencies proclaimed it “policy” to use specialty subcontractors where this was customary. The unions strengthened their no-strike pledge. Finally, the parties to the agreement set up a three-man Board of Review. Representing the federal construction agencies, OPM, and AFL, this board would settle any disputes arising under the agreement. Its decisions would be final.104

Within the ranks of the building trades, the pact encountered bitter opposition. Local unions balked at accepting its terms, calling strikes to protest loss of double time and cuts in shift-work premiums, while other protests took the form of slowdowns and absenteeism. National officers of the unions tried to pacify members by pointing out that the agreement would enable the AFL to organize all defense construction workers. As the president of the electrical workers put it, the agreement recognized “the Building Trades Department ... as the bargaining agency on defense construction jobs.” And he added:–

Never before in the history of our country has such material progress been made in the matter of an agreement requiring representatives of national agencies of our government, sitting with national representatives of the building trades organizations for the purpose of bringing about an understanding to cover construction work performed by, or for, federal agencies. ... This is a national recognition that has never before been attained and it must be admitted is of paramount value in the matter of negotiating with government officials concerning work on a nationwide basis rather than for only those parts of the country which are well organized.105

As the truth of this statement sank in, as the newly constituted board of review began its work of mediation and conciliation, and as shift work and longer hours boosted take-home pay, discipline improved.

Strong opposition to the agreement came from the Construction Workers Organizing Committee, which had followed the United Mine Workers out of the CIO. Charging discrimination, the Construction Workers’ president accused the government of negotiating a closed shop contract with the AFL.106 Questioned on this point by congressmen, Hillman explained: “The reason why the Government agencies dealt with the AFL is very simple. It was merely that the AFL Building Trades Group represented virtually all of organized labor in the construction industry. It was a matter of practical common sense for the agencies to make this choice.” Nevertheless, he insisted, “There is nothing in this agreement which prevents the Government agencies from awarding any contract to any employer, regardless of whether he operates under an AFL Contract, a CIO Contract, or with a nonunion shop.”107

Somervell and Mitchell considered the agreement a good one. The advantages they hoped to gain would outweigh the time lost in strikes and the accusations of impropriety. The agreement established uniformity in overtime rates, thereby saving the time of administrative personnel. Although Saturdays and Sundays continued as premium days and on some projects workers began to get premium pay on those days for the first time, the government would probably save money in the long run. On 30 July, Mitchell predicted that 38.1 percent of 750 classifications at 84 projects would cease receiving double time for time worked over eight hours a day; almost 45 percent of the rates paid for work done on Saturdays would decrease, and 57 percent for work done on Sunday; while only 10 percent would increase. Mitchell expected the number of requests for wage increases to decline. And he anticipated fewer strikes.108 Four months after the agreement went into effect, Somervell reported: “The adoption of this agreement has resulted in the stabilization of major working conditions on defense construction, economies in the cost of overtime work, and a consequent speeding up of the entire program.”109

With the Building Trades Agreement, well-selected sites, improved plans and procedures, and a stronger organization, Somervell was confident of the future. In November 1941 he informed General Gregory: “The Construction Division is ready to meet any demands the American people shall consider necessary in building for the defense of the United States.”110