Chapter 11: The Public Image

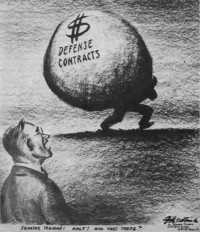

Directly or indirectly, military construction affected the life of every American. Farmers who gave up their land for the common defense, workers who took jobs at rush projects, young men who entered military service—all these had a personal stake in the conduct and progress of the program. The contractors, engineers, architects, and suppliers, who made up the vast construction industry, took a deep interest in the undertaking. Residents in hundreds of communities witnessed camps, plants, and airfields building on their home grounds. In fact, all citizens had an investment in the program, for as taxpayers they defrayed the cost. The construction effort thus provided a natural target for critics. From the beginning a vigilant public bombarded the War Department with letters of complaint. Many writers obviously had an axe to grind. Equipment owners attacked the recapture clause of the rental agreement. Unemployed workmen cried discrimination. Manufacturers deplored the use of rival products. Nevertheless, many correspondents appeared to be civic-minded men and women with patriotic motives. Some maintained that contractors were burying nails and burning lumber. Some denounced cost-plus contracts and labor racketeers. Some reproached the Army for housing men in tents during cold weather. One man objected to the drab appearance of the camps, another to the lack of camouflage.1 These letters revealed much dissatisfaction with the conduct of the program and widespread ignorance of the problems involved.

During the first fall and winter of defense preparations, newspapers and magazines presented a sketchy and one-sided picture of military construction. Preoccupied with national politics and the European war, the press gave scanty coverage to the building program. Too often stories on defense projects had to be sensational to be considered newsworthy. Troops shivering in tents or wading through mud, Army reservations blotting small towns from the map, jobs falling behind schedule—items like these appeared. Much space was devoted to high costs and alleged union shakedowns.2 Such events as the postponement of inductions and the relief of General Hartman were duly reported, but accounts of builders’ accomplishments were rare. Popular magazines did little to supplement information their readers may have

gleaned from dailies. Most periodicals ignored construction. Occasional articles in leading journals were harshly unfavorable in tone. Harper’s printed the memoir of an erstwhile worker at Camp Edwards, who recounted his “adventures in wood butchery” in the company of a clergyman, a lawyer, a barber, a jeweler, an undertaker’s assistant, two cooks, and dozens of Cape Cod fishermen—all employed as carpenters by the Walsh Construction Company.3 The Saturday Evening Post featured an account of the way construction workers had transformed the peaceful little town of Starke, Florida, into a modern replica of a frontier boom town.4 Life ran pictures of Camp Blanding; the caption of one shot read: “Among the 21,000 workers there was once such confusion that when 3 men died, other men drew dead men’s pay for a month.”5 Time referred to the “deplorable lag in Army housing” and the fanciful assumptions of “armchair constructors.”6 The general implication seemed to be that thickheaded construction officers were bungling the program.

Gradually, a different story emerged, an incomplete story with many inaccurate details, but one which had a good side as well as a bad and which told something of causes as well as of effects. The opening chapters were written by Somervell and an army of public relations men, headed by George S. Holmes.

Publicity and Public Relations

An admirer of Theodore Roosevelt and a student of his well-headlined career, Somervell knew the uses of publicity. “The whole country is extremely interested in the program,” he noted at the time of his appointment to the Construction Division. “As the men of the National Guard and draftees arrive in camp this interest will be intensified.” He saw an opportunity to enlist popular support. He would hire a public relations man and put him to work at once. He would employ all the mass media—newspapers, magazines, radio, and motion pictures. He would hold public ceremonies with prominent officials participating. He would utilize every possible means “to bring the program before the public.”7 Within a week, Holmes was on the scene.

Soon a campaign was under way to obtain nationwide coverage. On 26 December Somervell’s deputy, Colonel Styer, directed all Constructing Quartermasters to cooperate in the “effort to keep the people of the United States advised as to what is going on in the construction program.” Every project would have a qualified public relations man to gather information, write it up in readable form, and furnish it to the local press. These same men would forward weekly newsletters to Holmes by airmail every Friday. They would also send photographs—pictures illustrating special features of the work and aerial views showing general progress. Stressing the need for “terse, timely, and interesting” news and accurate facts and

figures, Styer wrote:–

The public is entitled to know the essential details of the construction program; the obstacles that have had to be overcome in many instances, the sacrifices frequently made by all concerned in maintaining schedules in the face of serious difficulties, the innovations and improvements over previous ... construction methods developed on the job, and other interesting and important achievements. These things are a legitimate source of news on every project.8

The response was generally enthusiastic. Some Constructing Quartermasters put local reporters on their payrolls as part-time employees, an arrangement that facilitated placement of news. Before long, weekly bulletins, photographs, and clippings from local newspapers were coming into the central office.9

Meanwhile, Holmes had “loosed a flood” of press releases—“exuberant” handouts, Time described them.10 The tone was reassuring. Past mistakes were being corrected. The program was receiving excellent direction. Somervell was portrayed reorganizing the Construction Division, conferring with the newly appointed Zone Constructing Quartermasters, instituting a program of accident prevention, congratulating contractors whose projects were on schedule, and in other conspicuous roles. The division made a better showing by reporting projects ready for “beneficial occupancy” as soon as some troops moved in or one production unit started operating instead of waiting to report actual completion. Bit by bit, the message began to go over. The New York Times gave the program fuller, more balanced coverage than before. Pearson and Allen, in a column on construction, praised Somervell and concluded that a major reason for earlier delays was “the fact that the job was not supervised by the Army Engineers” from the beginning.11 Time reported that “Army performance had improved since the Corps of Engineers’ able Brigadier General Brehon B. Somervell moved in on the Quartermaster Corps.”12

An article in Fortune and a War Department picture book surveyed accomplishments. “Camps for 1,418,000,” a 17-page spread in the magazine’s May 1941 issue, capped weeks of effort by Holmes to place “a readable article” in a periodical “with broad national circulation.”13 Breezily written and copiously illustrated, the story told how forty-six Constructing Quartermasters, “half horse, half alligator,” had “conjured forty-six cantonments and tent camps out of prairie mud or pine barrens or rocky defiles.”14 Citadels of Democracy: Camps and Plants for Men and Munitions, a handsome 44-page booklet run off by the Government Printing Office in June 1941, was a pictorial record “of six months of toil and sweat—to triumph over tremendous problems, handicaps, and the forces of nature—in achieving completion of the greatest Army building program of all time.”15 Somervell distributed thousands of free copies of Citadels, an action he

Flag raising at Radford Ordnance Works, Virginia

defended by stating that “the public is entitled to be informed.”16

A variety of public relations gimmicks stimulated interest and created good will. Somervell took time out from his other duties to assist in cutting a film on Camp Blanding and in editing its subtitles. A photographic exhibit, held at the Walker Art Galleries in Minneapolis shortly after the opening of the Twin Cities Ordnance Plant, attracted favorable notice. A guided tour of Fort Riley proved instructive to 100 members of the Topeka Engineering Club. Ground breakings, flag raisings, and dedications were public occasions. Typical of these ceremonies were the touching off of a stick of dynamite by Texas Governor W. Lee O’Daniel to mark the start of work at the San Jacinto Ordnance Depot, the presentation of a flag to the Army by a group of workmen at the Kankakee Ordnance

Works, and the turning over of a group of warehouses at Fort Houston to the commanding officer by the CQM. Local radio stations frequently broadcast proceedings of this sort.17

The construction industry received special attention. At the annual convention of the Associated General Contractors at Houston in February 1941, Somervell was a prominent participant—featured speaker, chairman of a conference on defense work, and guest of honor at the banquet. To the spring meeting of the American Society of Civil Engineers at Baltimore in April went Colonel Casey, an officer highly respected by civilian professionals. One or another of the division’s members generally appeared when such groups convened. Recognition of industry’s contribution and praise for its endeavors were favorite Somervellian themes. Addressing the contractors at Houston, he declared:–

No unbiased critic of the vast billion-dollar building job thrust upon the peacetime facilities of the construction industry overnight can fail to acknowledge the splendid manner in which it has risen to the occasion. It has been a gigantic task. Hammers did not begin to ring until well into October. Spades were not wielded in many locations until heavy frosts had penetrated the ground. The wonder is that so much has been accomplished in so short a time. The man with the contract, in my opinion, has more than made good.18

Several months later, in a paper for an AGC symposium on defense construction, he wrote:–

In this unparalleled achievement of housing more than a million officers and men within a period of much less than a year, and in providing ordnance factories and facilities under extreme pressure, members of the Associated General Contractors of America have played an important part.

They have brought to the task the “skill, responsibility, and integrity” upon which they pride themselves and have been vital factors in enabling the Temporary Emergency Construction Program to advance at a rate equal to, and perhaps greater than, that of any ether phase of the national defense effort.19

In “The Miracle of Defense Construction,” an advertisement in The Saturday Evening Post paid for by Johns-Manville, publicist Frazier Hunt reported how the “blue eyes of hard-working, super-efficient, 49-year old Brigadier General Brehon Somervell ... twinkled with pride when he talked to me in his Washington office about the all-important part the building industry is playing.” Hunt quoted Somervell:–

You can’t exaggerate what has already been accomplished. It’s like the statement made by the great General Goethals about the Panama Canal, “Birds were singing in the trees one week and ships sailing by the next.” Americans, working for America, have done it again! The whole building industry has come forward in unbelievably fine shape. The results speak for themselves. The efficiency and patriotism of these splendid men have been inspiring.20

As a eulogist of the industry, the former WPA administrator had few equals.

Holmes kept the trade press liberally

supplied with copy. Writeups on the Army’s building program regularly greeted readers. Flipping through the weekly Engineering News-Record, they would come across articles like these:– “Sewage Treatment for Army Camps,” “A Thousand Buildings in Five Months,” “Chrysler Builds a Tank Arsenal,” “Fighting Mud at Camp Wallace,” “Building a Camp in the Wilderness,” and “Handling a 20,000-Man Crew on a Camp Job.” As many as three such articles appeared in a single issue. News items, such as these, were even more plentiful: “Cantonment construction approaches peak,” “Defense housing at Fort Knox goes into high,” “Army construction now ‘on or ahead of schedule,’ “ “More civilian experts in army construction set-up,” “Camp Shelby completed on time and below cost,” “Production started at Charlestown powder plant,” and “Labor troubles on Army construction negligible.”21 Leading construction monthlies also featured reports on the program. For example, “Defense Construction On and Ahead of Schedule,” “Radford Ordnance Works Opens 3 Months Early,” and “Rolling Out the Barracks” were topics covered in one issue of The Constructor.22

In promoting better public relations, Somervell did not neglect Congress. Late in January 1941 he created a Contract Information Bureau, gave it a ground floor office, and placed Maj. Joseph F. Battley in charge. Explaining the bureau’s purpose to his branch chiefs, Somervell said:–

We must ... set up a foolproof system for informing Senators and Congressmen of the awarding of contracts in their states and districts and other matters of interest on which they have a right to be informed. We must establish a reputation for prompt, accurate and courteous information to these men, who are in fact the Board of Directors of our organization.23

In letters to individual congressmen, Somervell pointed out that Battley was “available to anyone in your office or to any of your constituents who may desire information,” at the same time adding, “I shall, of course, continue to render you such services as I can personally.”24 The bureau was a success. Battley gave immediate attention to inquiries and complaints. He sent each congressman a monthly bulletin listing contracts in force alphabetically and by state. He arranged for Senators and Representatives to make the first public announcements of contracts awarded for projects in their states and districts. So active did the bureau become that Maj. Alexander P. Gates, who succeeded Battley in June, required five telephones.25

Congressmen found Somervell friendly and considerate. Unlike Hartman, who had sometimes kept them waiting in the halls of the Construction Division, Somervell was never too busy to see them. If he did not always accede to their requests, he nevertheless gave them sympathetic hearings. Ranking members of important committees received invitations

to the general’s home to talk over upcoming legislation. Somervell welcomed opportunities to do congressmen good turns. For example, when he learned that 200 of their secretaries, members of the so-called “Little Congress,” were planning an outing to New York City, he asked General Gregory to arrange for a luncheon at the Fort Jay mess.26 On one thing Somervell’s colleagues generally agreed, he knew how to get along on the Hill.

Not everyone was favorably impressed by Somervell’s endeavors. Among construction officers there was a feeling that he had hogged the show, that he had made it a point rarely to give public credit to subordinates. After all, they reasoned, the first Roosevelt, while publicizing Teddy, had publicized the Rough Riders, too. Some laid Somervell’s actions to a mania for publicity; others, to intense ambition. Many grew to dislike and distrust him. Nor was Congressional approbation unanimous. Citadels of Democracy made Representative Taber boil with indignation. In a letter to Stimson, the New York Republican complained:–

I am grieved and surprised that the War Department would do such a thing. The “picture book” can have no possible use, can have no effect upon anyone except one of complete disgust. ... It savors of the War Department’s attempting to sabotage the Defense Program by wasting thousands of dollars upon such a fantastic document with the money so sorely needed for actual defense.27

Taking a stand as a member of the House Appropriations Committee, Taber admonished General Marshall:–

I want you in the War Department to realize the very bad impression that the sending of this booklet has had upon those in Congress who have the burden of sending and protecting the War Department’s requests for funds. Such a sabotaging of the Defense Program is utterly unfair to those of us who have taken the burden of asking the House of Representatives to trust the War Department with the enormous sums with which they have been entrusted.28

Somervell got publicity but not always the kind that would do him the most good.

His intensive public relations effort nevertheless produced some good results. The country received much information about the military construction program. During the first four and one-half months of 1941, newspapers throughout the nation gave Quartermaster projects nearly a quarter-million column lines.29 Somervell moved into the limelight and acquired new friends in Congress and in industry. His enhanced prestige and influence proved of benefit not only to him personally but also to the organization he headed.

Brilliant accomplishment and glittering success—such was the picture presented by Somervell. A sobering view opened to the public as Congress inquired into construction difficulties and the reasons behind them.

Congressman Engel Investigates

Representative Albert J. Engel was the first to attempt a systematic inquiry. A member of the House Appropriations Committee, the Michigan Republican

had long advocated giving all military construction to the Corps of Engineers. Throughout the summer of 1940 he followed the progress of appropriations for sheltering Guardsmen and selectees. Engel wished to examine the War Department’s estimates closely before voting construction funds but found his plans blocked by the tactics of the Majority. He later recalled his experiences on the September day in 1940 when the House voted the bulk of the money for Army housing: “A clerk of the Appropriations Committee came to my office at 5 minutes to 12 and asked me to approve the Regular Army housing bill, which amounted to $338,000,000, without a full committee meeting. I refused to do this. When I got to the floor, the House was in session, and the bill was being considered. I reserved the right to object, but finally realizing the need of immediate Army housing for the draftees, did not object.” Engel continued to pursue the matter. During October he obtained a breakdown of Hartman’s building estimates and inserted it into the Record. He expected the Army “to account to Congress for every dollar.” About the first of December he began a one-man investigation of camp construction.30

On 16 January 1941, in a speech before the House, Engel described his efforts to find out “just how this money is being spent.” So far he had collected cost data on twenty-three projects. On the basis of this information, he put the construction deficit at $300 million, a figure remarkably close to the War Department’s own estimate. He had also made an exhaustive study of Camp Edwards. “In view of the fact that all the projects are handled ... in the same way,” he told his colleagues, “I thought that an analysis of this one job might give us an idea of what happened on a majority of all the jobs.” But after dissecting the operations of the Walsh Construction Company, Engel had concluded that it “would be presumptuous for me to make definite, permanent recommendations ... when I have so small a proportion of the facts before me.” Announcing his decision to broaden the investigation, he indicated what he expected to learn. Three years earlier he had suggested to General Craig “that the construction quartermaster work be transferred to the Army Engineering Corps.” Promising Congress “definite recommendations” soon, he now stated:–

The Army housing program ... actually places Army engineers into the Construction Quartermaster Corps. But we still have practically the same conditions existing as before. Construction work requires trained men. It is the engineers’ and architects’ job; and the sooner we learn this, the sooner we are going to eliminate a great deal of inefficiency, including waste and extravagance.31

In February Engel set out to inspect camps in the East and South. Before leaving Washington he asked for a letter giving him entree to any project and permission to examine anything he wished. Somervell furnished the letter and offered the services of Captain Davidson as companion and guide. Engel took the letter but left Davidson behind.32 His visits were intended to surprise. “I

do not want the camp to know when I’m coming,” he said.33 For the next few weeks the specter of the ubiquitous Mr. Engel haunted Constructing Quartermasters. Engel would arrive on the scene at an early hour, unannounced and unobserved. He would spend the morning touring the project, taking pictures, talking to workmen, examining materials and equipment, poking into scrap piles, looking everywhere for irregularities. By the time camp authorities became aware of his presence he would be ready to go over the contractors’ books and to question the project manager, the auditor, and the Constructing Quartermaster. His departure was as unceremonious as his arrival. Before sundown he would be off to another undisclosed destination and would drive “to the next project that night so as to be able to join the caravan of workers as they arrived at the camp at or before 7 a.m., the next morning.”34

The uninvited guest taxed the patience of his hosts. The New York Times portrayed the congressman at Fort Bragg, backing four generals into a corner.35 During Engel’s visit the Constructing Quartermaster at Bragg, Lt. Col. Lawrence L. Simpson, made an excited telephone call to Washington. “I wanted to assure you that we are being just as diplomatic as possible,” he told Groves. But efforts to “ease him along” did not divert Engel. Simpson complained: “He won’t let any of us go with him. He wanted to get those pictures and didn’t let us know he was here. ... In the meantime, if he does see anything he can pick up that would look bad, he will do it.” Simpson reported that Engel had announced he was going to censure the Quartermaster Corps when he got back to the capital. On hearing this, Groves exclaimed, “Encourage him to go further away.”36 Engel went as far as Blanding; then he headed home. Late in March the Construction Division learned of his return.

Engel was soon ready to lay his findings before Congress. During the first week in April he delivered two lengthy addresses, one on Camp Blanding, the other on Camp Meade. At the Florida camp, Engel had uncovered the following information: 54,000,000 board feet of lumber had been bought for the project at an average price of $40 per thousand; 580,000 tons of lime rock costing $1,250,000 had been used for roads and parkways; rentals on equipment valued at $4,628,605 had totaled $1,992,080 by 20 February; $1,079,400 had been paid out in overtime; half of the 5,000 men who had drawn carpenters’ wages had “very little, if any previous experience.” Engel implied that the Quartermaster Corps had paid too much for labor, equipment, and materials and hinted at collusion on bids for the limestone contract. His chief target was the Blanding site. After pointing out that 40 percent of the building area was below the level of nearby Kingsley Lake, he went on to contend that the location had added $5,000,000 to the cost of the camp. In conclusion he stated, “There is no question in my mind but that the selection of this site … was not only unfortunate and extremely expensive, but shows gross inefficiency and a total disregard for taxpayers’

interests.”37 Two days later Engel spoke on Meade. Once again he presented an array of figures as “evidence of waste and extravagance due to incompetency and inefficiency.” As before, he directed his ire against men who had chosen the site. “I say here and now,” he declared, “that the officers in the United States Army who ... are responsible for this willful, extravagant, and outrageous waste of the taxpayers’ money, ought to be court-martialed and kicked out of the Army.”38

Interest in the one-man probe flared briefly and subsided. Warmly applauded by his colleagues at first, Engel commanded dwindling audiences in the House. After reporting his early sallies, the press fell silent. The morning after Engel’s address on Meade, Somervell remarked to his staff, “I have been speculating, without being able to get an answer in my own mind, as to just what help these speeches are going to be to National Defense.”39 Groves put his finger on one of Engel’s difficulties: “He’s a better man than I am if he can go to a camp and wander around it for a day and then come up with the whole story.”40 A rigorous investigation of the building program was not a one-man job.

Engel took the floor again on 17 April. His subject was a different camp, Indiantown Gap, but his speech had a familiar ring. Predicting a deficit of $10.3 million, he asserted that prices paid for lumber were 20 to 25 percent too high, that rentals on equipment amounted to 50 percent of appraised valuations, and that one of every five men paid carpenters’ wages lacked carpenters’ skills. He noted that $15,000 had gone for termite shields in an area where a wooden building had stood since the 17th century without suffering damage from insects. Criticism of the rocky, mountainous site climaxed his remarks. “There is no question in my mind,” he said, “that the selection of this site has cost the taxpayers millions of dollars.” In a lively exchange, one Democratic congressman insisted that, in fairness to the War Department, evidence of negligence, bad judgment, and waste of public funds be spelled out in the Record. Engel countered: “I have had information that the War Department has had engineers go over my Blanding and Meade speeches, made on April 1 and April 3. They have had 2 weeks but no answer has been made by them thus far.”41

When the War Department continued silent, Engel did not persist. A speech on Camp Edwards, scheduled for 1 May, went undelivered. Offered as an extension of remarks, it was interred in the Record’s appendices. An address on Fort Belvoir met the same fate.42 The one-man probe was over. Engel’s findings were obscured by those of other, more thoroughgoing investigators.

House and Senate Committee Investigations

Sooner or later there was bound to be a full-dress Congressional probe. World War I had produced the Chamberlain and Graham investigations; the Spanish-American War, the Dodge; and the Civil War, the Wade. As far back as the

Revolution, Congress had looked into the conduct of military preparations. In fact, as one scholar has pointed out, “of all administrative departments the Department of War has come most often under the inquisitorial eye of Congress.”43 During the fall of 1940 there were rumblings of a Congressional investigation into the Army’s defense activities.44 Early in the new year committees of the House and Senate launched formal inquiries. Military construction was the initial target.

On the morning of 12 February, the House Military Affairs Committee began hearings. First to testify was Forrest S. Harvey of the Construction Advisory Committee. Chairman Andrew J. May opened the proceedings by asking “just how” the Quartermaster Corps let its contracts. Harvey started to explain but was soon deluged with questions.45 Representative Dow W. Harter inquired why most of the work was going to large concerns. Representative Matthew J. Merritt asked why some firms had received two contracts while other firms went begging. Representative John M. Costello wanted to know why the Army had not broken up large contracts so that more firms could participate.46 Harvey’s explanation of the reasons for giving industrial projects to a few select firms was dismissed by Pennsylvania’s Charles I. Faddis with the remark, “I am not convinced that there is as much specialization on contractors as maybe we have been led to believe.”47 His statement that the advisory committee granted interviews to all comers was contradicted by Louisiana’s Overton Brooks, who said he knew several contractors turned away by the committee.48 When Harvey stated that he could appraise contractors’ qualifications from their answers to a questionnaire, Representative Paul J. Kilday rejoined, “I think you are a genius.”49 Several of the Congressmen questioned the advisory committee’s impartiality. Representative Andrew Edmiston implied that political considerations had influenced its selections. Kilday suggested that the Associated General Contractors had had a hand in its decisions. Brooks made pointed reference to the fact that Harvey had worked for Leeds, Hill, Barnard and Jewett, the architect-engineer at San Luis Obispo. In two days before the House Committee, Harvey failed to dispel these doubts.50

The next witness, Francis Blossom, underwent a cruel ordeal. After a few preliminary questions, one committee member asked him: “Now, since you have been ... a member of this board has the firm of Sanderson & Porter received any contracts from the War Department?” Blossom’s affirmative answer evoked a storm of questions. Was he an active partner in the firm? He was. What would be his share of the fee for the Elwood Ordnance Plant? Approximately $125,000. Although testimony revealed that Sanderson & Porter was eminently qualified for the job and that neither Blossom nor the Construction Advisory Committee had participated in

this selection, the Congressmen showed no disposition to let the matter drop.51 On 15 February, the day after Blossom’s appearance, Stimson noted in his diary, “There is no evidence of any impropriety or corruption on the part of Blossom but they are making a big hue and cry over it and it is a very unpleasant thing.”52 The hue and cry continued as Somervell, Patterson, Campbell, and others were questioned about the Elwood contract.53 Recalled by the committee at his own request, Blossom announced his decision not to participate in the profits of his firm for the years 1940 and 1941. “I trust that it will be understood,” he told the House group, “that this is not an inconsiderable sacrifice for me to make. Nevertheless, I make it freely and willingly as my contribution to the welfare of my country.”54 Shortly afterward, he resigned from the advisory committee and returned to private life. “I think,” Patterson commented, “that a man of proper sensibilities, being criticized, even though he might not think the criticism just, might be prompted to say, ‘I would stand clear of it all together.’ I am sure that he came down here from the most patriotic and high-minded motives.”55

A procession of witnesses passed before the House group. A third member of the Construction Advisory Committee, Mr. Dresser, repeated much of Harvey’s testimony. General Somervell defended cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contracts. John J. O’Brien and Congressman Clarence Cannon presented their views on real estate brokers. General Brett reported on the progress of the Air Corps program. On 1 April Chairman May suspended hearings on defense construction.

Thus far the House investigation had aroused only moderate interest. Except for the disclosures concerning Blossom, little new information had come to light. On the whole, questioning had been unmethodical and desultory, and testimony had lagged. The committee had asked many of the officials who came before it to discuss matters of which they had little or no direct knowledge. The practice of permitting members to take turns interrogating each witness had led to tedious repetition. Moreover, the Congressmen were not sufficiently well grounded in construction to conduct a comprehensive inquiry. Chairman May occasionally lost patience with his colleagues. From time to time he urged them to “get along a little faster” or chided them for “going far afield.”56 But his efforts to keep the discussion from bogging down were not entirely successful. After six weeks of hearings the investigation appeared to have run its course.

Then, on 2 April, the inquiry received a new lease on life. That day the House adopted a resolution, authorizing the Military Affairs Committee to make a thorough study of the Army’s defense activities. Immediately after passage of this resolution, the committee met to discuss procedures for conducting its probe. It agreed to form three special committees, the second of which would consider real estate and construction. Special Committee No. 2 would have nine members; R. Ewing Thomason of Texas would be the chairman. Soon after

its formation, the Thomason group began to lay plans for carrying out its work.57

News that the May committee was preparing to widen its investigation caused some consternation in the War Department. A full-scale Congressional inquiry would place a heavy burden on the Department’s staff, which would have to search out data, answer questions, and produce witnesses. The probability that the committee would call for secret information raised a ticklish question—should the Department refuse to furnish classified data and thus raise suspicions that it was hiding behind a security cloak or should it comply with the committee’s requests and thus run the risk of aiding potential enemies of the United States.58 If officials also feared an outbreak of muckraking, this fear soon subsided. During early stages of the inquiry a Quartermaster observer noted: “The House Committee does not appear to be in a belligerent or tense attitude. ... While the committee is on a ‘fishing expedition,’ they are entirely relaxed and will investigate in as cooperative a spirit as possible.”59 This spirit of cooperation continued throughout the life of the investigation. By agreeing to take secret testimony in executive session and by limiting requests for information, the committee showed consideration for the War Department. The House inquiry furnished a notable example of good relations between an investigating committee and an executive department.60

After reviewing testimony before the full committee, Thomason concluded that “open hearings did not constitute the best vehicle for development of facts.” He also saw that few committee members could cope with complexities of military construction. Methods employed by his committee reflected this realistic attitude. Thomason and his colleagues assembled a staff of experts in real estate, labor relations, engineering, business, and accounting. They persuaded the Comptroller General to lend them Albert W. Perry, who became their chief counsel. They made extensive use of questionnaires. They sent investigators to jobs throughout the country and visited a number of sites themselves. They assembled a mass of documentary evidence. Such hearings as they held were closed. In short, the Thomason investigation took on the character of a research project.61

On 2 May the Thomason committee sent out its first questionnaire. Addressed to Secretary Stimson, the questions covered such subjects as site selection, land acquisition, plans and specifications, and costs. The committee asked for data on all building projects costing in excess of $5,000,000 and all real estate transactions involving $200,000 or more. The Secretary reacted promptly to Thomason’s request. Maj. Carlisle V. Allan of the General Staff took charge of coordinating the War Department’s work with

that of the committee. Capt. Clarence Renshaw of Groves’ staff drew liaison duty with the Thomason group. Chief responsibility for answering the questionnaire fell to Maj. Garrison Davidson, another of Groves’ officers. By 7 May Davidson had a force of six men at work. Two weeks later General Gregory replied informally to Perry. The committee meanwhile had prepared two more questionnaires. One, calling for detailed discussions of the quality and cost of construction, delays, equipment rentals, and fees, was for individual contractors. The other, dealing with the Army’s plans for building additional camps, was for the War Department. By the middle of June, answers to most of these queries were in Thomason’s hands. During the next two months the special committee inspected construction projects, questioned officials, and analyzed the information it had gathered. Not until the third week of August was Thomason ready to report.62 Meantime, public interest centered on another investigation.

Among the visitors at the first hearing of the May committee was the junior Senator from Missouri, Harry S Truman.63 Two days earlier, on 10 February, he had told the Senate that he planned to ask for an investigation of the defense effort. In his speech on that occasion, Truman said that the government’s procurement policies were apparently designed “to put the little man completely out of business.” After picturing the plight of the little manufacturer and the owner of the little machine shop, he discussed the little contractor. The Senator outlined the criteria adopted by the Construction Advisory Committee. “Were these requirements religiously carried out,” he stated, “no one could find fault with them; but the rules do not fit the facts.” He charged that Dresser, whom he characterized as the committee’s leader, was giving contracts to friends. At the same time, Truman contended, “It is considered a sin for a United States Senator from a State to make a recommendation for contractors, although we may be more familiar with the efficiency and ability of our contractors at home than anybody in the War Department.” Like many another member of Congress, Truman believed that the fixed-fee method worked considerable mischief and that it not only stifled competition but encouraged contractors to defraud the government. Recalling his experiences with public works as a county judge in Missouri, he assured the Senate that contractors would take full advantage of their current opportunity to fleece the government. “I consider public funds to be sacred funds,” he declared in closing, “and I think they ought to have every safeguard to prevent their being misused and mishandled.” Only by getting at the bottom of the present situation could Congress prevent a recurrence of the profiteering of World War I.64 Three days later, on 13 February, Truman introduced a resolution for a special

investigating committee, and on I March the resolution carried.65 The chairmanship went to Truman. Named to serve with him were old-line Democrats: Tom Connally of Texas, James M. Mead of New York, Mon C. Wallgren of Washington, and Carl A. Hatch of New Mexico. Republican members were Joseph H. Ball of Minnesota and Ralph O. Brewster of Maine. This investigation, which continued throughout the war, brought its first chairman into national prominence.

The emergence of Senator Truman as inquisitor plunged the War Department into elaborate preparations to defend its record. Even before passage of the Senate Resolution, Patterson had called for reports on matters Truman might look into.66 Such a request was more or less routine. Early in March, however, Patterson’s advisers began advocating a “real attempt ... to present an affirmative case.” “As you know, in many Congressional investigations those in charge attempt each day to make headline news,” wrote Special Assistant Howard C. Peterson. “For this reason and because the results of a full-dress investigation will have an important effect on the relations of the War Department with the Congress and the public, I think it is imperative that the testimony of representatives of the War Department be carefully presented and adequately prepared.”67 Patterson took this advice. He put able men on the case: Julius H. Amberg, past president of the Michigan Bar Association and now assistant to Secretary Stimson, would direct the War Department’s presentation; Lt. Col. Arthur R. Wilson of G-4, an officer of considerable political acumen, became the War Department’s liaison with the committee; Major Davidson became Somervell’s. Together with Peterson, these men helped determine the War Department’s strategy.

By late March preparations were in full swing. On the 28th Amberg held a meeting with Quartermaster officers, including Gregory, Somervell, and Groves. After outlining the probable scope of the investigation—geographic distribution of defense contracts, favoritism in awards, profits on fixed-fee jobs, selection of camp sites, original estimates and final costs, delays in completion, methods of land acquisition, and union activities—he “urged the frank admission of mistakes where they existed and a full statement of the measures that had been taken to correct them.” In a point-by-point discussion, Amberg took the part of devil’s advocate while the officers postulated the case for the Construction Division. The sense of the meeting was “that the Quartermaster Corps had very little to apologize for, that in presenting its case to the Committee, every effort should be made to make an affirmative case ... , rather than to take a purely defensive attitude on all matters that the Committee cares to bring up.”68 Also on the 28th, Secretary Stimson began planning his appearance before the committee. Under that date he wrote in his diary:–

I began to prepare my speech which I am going to make to the Senate Investigating Committee. ... It is a big chore

but I think a very necessary one. We are confronted with an investigation which will undoubtedly try to maximize the blemishes and defects of this great effort that has been made by the War Department for the past year and will entirely obscure the difficulties and the achievements. ... As I am the first witness, I am going to try to forestall that by making a careful written presentation which will show what we have done and what our difficulties have been and how magnificent the accomplishments have been; in other words, to start the thing off on the right foot and to, if possible, put to shame the attempts to belittle it.

Aided by McCloy and Somervell, the Secretary toiled for days over “this confounded speech.” He found it “one of the hardest jobs that I have ever had.”69

Late in March, amid reports that he was headline seeking,70 Truman went on the radio. Rumors were rife in Washington, he said, of irregularities in awarding contracts and locating plants, of lobbyists at work, of “outrageous prices” paid for land, and of unconscionable profits and avoidable waste. He intended to get to the bottom of things. “There will be no attempt to muckrake the defense program,” he assured his listeners, “neither will the unsavory things be avoided.” Coming to the crux of his message, he said:–

We recognize the importance of conducting this investigation so as not to add delay and confusion to an accelerated defense program; yet a properly conducted investigation now can be valuable both for its deterrent effect on those who might otherwise go wrong, and for constructive suggestions which it can offer to the Congress for legislative action and to the Executive for administrative improvement. So that instead of being a witch-hunt after the mistakes are made and the crimes committed, this committee can be of immense constructive help in bringing the defense program to successful accomplishment.71

Shortly after the Senator’s radio address, the committee’s chief counsel, Hugh A. Fulton, conferred with Amberg. Fulton wanted more information about the War Department’s “soft spots” and specific examples of abuses. He mentioned lobbyists, excessive prices, discrimination against small contractors, and mistakes in site selection as topics of special interest. Amberg pointed out “that it would be difficult to get our personnel to inform us that they had done something wrong which should be investigated.”72 Nevertheless, the committee was soon receiving suggestions. Somervell, for one, was closemouthed at first, but, according to Truman, he came around when he realized the committee might be useful to him.73

On the morning of 15 April Secretary Stimson took the stand to open the committee’s first public hearing. In his carefully prepared statement, he described the sudden and unexpected nature of the emergency. By comparing the situation of 1940 with that of 1917, he brought the Army’s current problems into sharp relief. By recalling the prolonged debates of the previous summer, he drew attention to the fact that Congress had allowed the War Department little time to do its job. The Secretary then launched into a discussion of construction and procurement. Leaving

explanations to later witnesses, he kept his remarks general. The burden of his testimony was a plea for recognition of the War Department’s achievement.74 “With the magnitude of the task and the speed and pressure under which it was performed, it is inevitable that some mistakes have been made,” he told the Senators, “but when the work of this committee is completed, I am confident that it will be found that the total of these mistakes will appear quite insignificant when set against the value of the time saved and the size, of the task performed.”75 Patterson, who presented a detailed account of the Army’s procurement and construction programs at the afternoon session, followed much the same line as Stimson. “It is fitting,” he told the committee, “that we render an account of the manner in which we are performing our trust. We have been vigilant, we believe; but if abuses have crept in despite our vigilance, they must be eradicated.”76 The statements of the Secretary and the Under Secretary seemed to make a favorable impression. After answering the Senators’ polite questions and receiving their compliments, the two witnesses stepped down.77 Describing their treatment by the committee, Stimson wrote later that day:– “They were mild as milk and I couldn’t help feeling that there was ... no latent hostility in the air around me.”78

After a week of eliciting “background information” from such top defense officials as Knudsen and Hillman, the committee got down to the business of construction.79 On 22 April it called the Chief of Staff to testify on mobilization and troop housing. A parade of construction experts followed him to the stand. Appearing for the Construction Division were Somervell, Harvey, Loving, and Groves. The list of witnesses lengthened to include members of the General Staff, Constructing Quartermasters, contractors, architect-engineers, and renters of equipment. In time the committee quizzed virtually every major actor in the construction drama and many minor ones besides. In its investigation of the building program, the Truman group at first pursued the same line of inquiry as the May committee. The Senators wished to learn the reasons for the overrun in camp expenditures and to uncover dishonesty and extravagance. Early testimony revolved around questions of contracts, real estate, and sites. Such subjects as profits, salaries, wages, and equipment rental rates evoked special interest. The committee bore down heavily on the evils of cost-plus contracts, making no sharp distinction between fixed-fee and percentage types. The probe revealed costly mistakes—General Parsons’ layout of Camp Meade was one—and pinpointed instances of waste, such as the payment of $150 monthly rental for a 1917-model truck. It also raised challenging questions: for example, were too many contracts going to big concerns. But it failed to unearth any real evidence of fraud or corruption.80

The one major construction scandal that came to light involved General R. C. Marshall. Acting, purportedly, on a tip from Somervell, the committee

summoned the former Chief of Construction to answer charges of influence peddling. During the early months of the defense effort, Marshall had served as consultant to the following construction firms: Mason & Hanger Company, Dunn and Hodgson, Consolidated Engineering Company, J. A. Jones Construction Company, MacDougald Construction Company, and Taylor & Byrne. All these concerns had received fixed-fee contracts from the Quartermaster Corps. The committee’s investigation, during which Marshall destroyed his files, failed to produce any evidence of official wrongdoing.81 Nevertheless, disclosure of his activities brought action by the War Department against Marshall and his clients. Secretary Stimson demanded Marshall’s resignation from the Reserve Corps. General Gregory deducted the amount of Marshall’s fees from payments due his clients.82 If, as was alleged, Somervell had vowed to fix “Puck” Marshall so “he won’t be able to hold his head up in this town,” he came near to succeeding.83 But Marshall, always a dangerous opponent, got his licks in, too. In the course of his testimony, he had managed to place before the committee a proposal for a separate construction corps.84

As the committee probed deeper into building problems, it became apparent that responsibility for much of the construction muddle lay outside the Quartermaster Corps. Turning his attention to the Army’s mobilization plans, Truman called six officers of the General Staff, several of them retired, for questioning. Their testimony revealed that the Staff had not foreseen mobilization short of war. The absence of a blueprint for peacetime mobilization explained many conditions underlying high construction costs: hasty selection of sites, lack of plans and specifications, and reliance on the fixed-fee contract.85 Convinced that the Army’s M-Day plan had been in fact “an Indian-war plan,”86 Truman declared that its author “ought to get a currying.” “I am going to keep on digging,” he told General Seaman, “until I find the fellow who is responsible for this situation, because I labor under the impression that . concrete plans for a mobilization of a million men contemplate a place to put them and a place to train them. Evidently you did not have it.”87 Truman’s attempt to assess guilt solely in terms of individuals was doomed to failure. Congress and the people shared with the Army responsibility for the nation’s unpreparedness. But if Truman’s hope of finding a culprit was futile, his opinion of the mobilization plans was well founded. By showing the effects of unrealistic planning on the construction program, he projected a valuable lesson for future military leaders.

With two committees, Thomason’s and Truman’s, inquiring into construction, speculation arose as to which would be first to report its findings. The House group began writing its initial report around Memorial Day. Within a few weeks Truman was pushing work on his own report. On 12 June, Counsel Perry of the Thomason committee told Captain Renshaw: “I am preparing material to show that the Quartermaster Corps is

doing one of the most efficient jobs of any of the departments, if not the most. After having been kicked around so much I imagine you won’t mind that encouragement.”88 Truman’s counsel, Fulton, promised to let the War Department assist in presenting his committee’s findings. On 15 July he sent an 80-page draft to Amberg and gave him one week to propose amendments. Amberg replied with 32 pages of suggestions. While Truman adopted some of these changes, he disregarded most of them.89 On 13 August, Amberg warned Stimson that the “confidence of the country may be somewhat shaken by the Senate report.”90 Truman made his findings public the following day. On the 19th the Thomason committee released its report to the press.

The report of the Senate committee constituted a stinging indictment of military ineptitude, shortsightedness, and extravagance. Stating that “the lack of adequate plans” had been the principal reason for the overrun in construction costs, the report cited a number of other contributing factors, among them, inadequate organization, inexperience, speed, winter weather, fixed-fee contracts, and poor sites. Although the stress given to mobilization plans put the bulk of the blame on the General Staff, the Quartermaster Corps was sharply criticized for mistakes in original estimates, for mishandling the land acquisition program, for failing to centralize all purchases of lumber, for permitting contractors to make faulty layouts, for using slipshod administrative methods, for neglecting to take advantage of land grant freight rates, and for paying too much for equipment rentals. With respect to charges of fraud and dishonesty, the committee stated on the one hand that it had found no evidence and on the other called for a “most careful check into this phase of the program.” The Senators’ recommendations included an unexpected bombshell: they urged “the creation of a separate division of the War Department to be charged directly with ... construction and maintenance and to be entirely separate and distinct from the Quartermaster Corps.”91

Thomason’s findings to some extent offset the effects of Truman’s. “From a military point of view,” read Thomason’s statement, “there can be no question but that the Construction Division has done a magnificent and unparalleled job of preparing housing accommodations for an Army that was created almost literally overnight.” The committee defended some procedures attacked by the Truman group and cited instances of “unjustified criticism.” It held that the Construction Division had “been diligent in discovering and frank in acknowledging its mistakes, and, more important, in taking remedial action.” On the question of mobilization plans, the committee commented, “It is more than obvious that Congress must share with the Army any censure for failing to foresee a situation that seems so clear today.” Yet the Thomason report was not a whitewash—far from it. It emphasized the “staggering” cost of the building program. It revealed instances of nepotism at

construction projects. It called attention to “indiscriminate and exorbitant” pay raises granted by fixed-fee contractors to their employees. Nevertheless, the general tone of the report was complimentary to the War Department.92

Although the House and Senate committees continued their surveillance over construction throughout the war emergency—holding hearings, visiting job sites, and issuing reports—after the summer of 1941, “the spotlight of inquiry,” as Truman phrased it, “was to be turned elsewhere, as well—on other agencies of the government, on big business, on labor, and on other segments of the economy involved in the total defense effort.”93 As far as construction was concerned, the fundamental investigative work had been accomplished and the most significant contributions had been made in the year before Pearl Harbor. Basic flaws had been exposed and remedies suggested. Those charged with construction had received a clear-cut challenge to do a better job. Moreover, the public record had been extended by hundreds of pages of testimony and public understanding had been deepened by several bipartisan reports.

From the mass of details presented to him by reporters, publicists, and investigators, the man in the street could draw his own conclusions. But whether he saw success or failure, triumph over difficulties or inept bungling, he could hardly escape the conviction that construction was vitally important to defense and that its conduct should be of serious concern to every thoughtful citizen.