Chapter 8: From Salerno to the Volturno

At the TRIDENT Conference in Washington in May 1943, the British and Americans agreed that after Sicily they should undertake further operations in the Mediterranean “calculated to eliminate Italy from the war and to contain maximum German forces.”1 That statement glossed over disagreements between British and Americans about the relative emphasis to be given the Mediterranean, the British insisting that resources should be concentrated there in 1943 while the Americans wanted to prepare for a cross-Channel attack in 1944. As the Allies swept through Sicily, however, growing signs of Italian collapse produced agreement on an immediate invasion of Italy to follow up on the victory in Sicily. On 16 August General Eisenhower decided to move British Eighth Army forces across the Strait of Messina at the earliest opportunity and to launch Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark’s Fifth Army (with a British corps attached) on a major invasion of the Italian mainland on 9 September.

Engineer preparation for the invasion began with the establishment of Fifth Army headquarters on 5 January 1943 at Oujda, French Morocco. The army engineer, Col. Frank 0. Bowman, had organized his section on paper a month earlier, but his staff, drawn largely from the American II Corps engineers, was hardly versed in engineer planning at the army level. Bowman provided what direction he could from his experience as the AFHQ engineer in England and in North Africa, but his temporary reassignment from April to August 1943 as SOS, NATO-USA, engineer left the section to Col. Mark M. Boatner, Jr., who presided over the interim work on other proposed invasions in the Mediterranean.

Fifth Army headquarters considered a number of proposals, and the engineers contributed map plans, supply schemes, and terrain studies to nearly all of them. An inherited plan, Operation BACKBONE, called for a foray into Spanish Morocco should Spain change its nominally neutral stance in the war. In the summer of 1943 the engineer staff entered the planning for BRIMSTONE, the invasion and occupation of Sardinia. Several plans involved a thrust into Italy itself, and many of the accumulated concepts coalesced into the final assault plan. BARRACUDA aimed directly at the harbor of Naples, GANGWAY

at the beaches immediately north of the city. MUSKET would have brought Fifth Army into Taranto and required a much longer overland campaign to the Italian capital. Operation BAYTOWN was the British move across the Strait of Messina to Reggio di Calabria. The Combined Chiefs of Staff ruled out BRIMSTONE on 20 July, and after the twenty-seventh the main features of BARRACUDA and GANGWAY were combined into planning for AVALANCHE. Through August the Fifth Army staff wrestled with choosing a target for the invasion. General Clark favored the Naples operation for the leverage it would provide in landing slightly farther north and cutting off German forces in southern Italy. With the cooperation of British engineers from 10 Corps, scheduled to make the landing as part of Fifth Army, and with reliance upon American terrain analyses and British Inter-Service Information Series (ISIS) reports, Colonel Bowman formulated his own recommendations, leaving room for the attack near either Naples or Salerno, 150 miles southwest of Rome on the Italian coast. Since Naples lay just outside the extreme range of Allied fighters operating from Sicilian airfields, the beaches at Salerno, just within range, became the primary choice for the assault.2

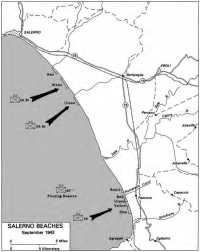

The Salerno beaches had advantages and disadvantages for the invaders. (Map 7) Slightly steeper than those in the Gulf of Naples, they afforded transport craft closer access to the shore. Sand dunes at Salerno were low and narrow and tended to run easily into beach-exit routes. The topography behind the beaches was suited for dispersed supply dumps, and a roadnet close to shore could support forward troop and supply movement. Though there were no clearly organized defensive positions in the area, the mountains behind the beaches formed a natural amphitheater facing the sea. Enemy observation posts would detect any movement below, and artillery fire from the high ground could reach the attacking forces easily. Once ashore, troops would find the way to Naples obstructed by the rugged Sorrento ridge, which sloped out into the sea on the northern arm of the Gulf of Salerno. The actual landing zone was split almost exactly in two by the mouth of the Sele River, which would hinder communication between the two halves of the beachhead until the engineers could bridge the stream.

Enemy strength in the area was considerable. Under the command of Tenth Army, German forces were withdrawing from the southern tier of the Italian boot throughout the latter part of August in accordance with rough plans to concentrate a strong defense just south of Rome. The movement accelerated after the British jump into Italy early in September, with the XIV Panzer Corps, composed of the reconstituted Hermann Göring Division, the 16th Panzer Division, and the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, strung along the Italian west coast from Salerno north to Gaeta.

Recognizing that the Salerno beaches were suitable for an Allied incursion, the 16th Panzer Division’s engineers in the area emplaced mines and beach obstacles along the dunes from Salerno to Agropoli, at the southern extent of the bay—but not so extensively as might

Map 7: Italy Invasion plans

have been expected. The Germans, regarding the Italian will to fight as negligible amid rumors of imminent defection, took over the coastal defenses of the Salerno area, executing the protesting commander of an Italian division in the process. They supplemented local batteries with their own heavy pieces in the mountains behind the beaches, especially on the imposing 3,566-foot Monte Soprana. They also emplaced a series of strongpoints in the foothills fronting the sea, with a particularly heavy concentration back of the southern complex of beaches in the area eventually chosen for the VI Corps attack. Panzer forces were expected to support these points with mobile counterassaults and supplementary fire. An Italian minefield offshore completed the defenses of the beaches.3

Unit assignments for the invasion force continued all summer. In the final operation plan of 26 August, the American VI Corps, with five divisions, was to seize the right-hand half of the landing zone south of the Sele River around the Roman ruin of Paestum while the British 10 Corps assaulted the northern half of the beachhead closer to the town of Salerno. All veterans of the theater, the 3rd, 34th, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions would accompany the 1st Armored and 82nd Airborne Divisions. Apart from the support provided for the invasion, each division had its assigned organic engineer battalion, the 10th Engineer Battalion with the 3rd Division, the 109th with the 34th Division, the 111th with the 36th, and the 120th with the 45th; the 1st Armored Division had the services of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, and the airborne division had the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion. As one of the most practiced units in amphibious attacks, the 36th Infantry Division was assigned the actual beach assault. The division’s 141st Infantry Regiment was on the extreme right, landing on Yellow and Blue beaches, where a medieval stone tower at Paestum afforded a good point of reference for incoming boats. The 142nd Infantry, to land on Red and Green beaches to the left of the 141st, covered the area north to an artificial waterway, the Fiumarello Canal; the two regiments were assaulting an expanse of 3,740 yards of contiguous beach front.

A Navy beachmaster was to maintain all communications with the ships and control all the operational landings. A port headquarters, consisting of two Transportation Corps port battalions, was to coordinate all unloading into small craft offshore, but the pivot of beach supply operations was the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment and the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, the former assuming responsibility during the assault phase. The 531st, a component of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade for the invasion, replaced the 343rd Engineer General Service Regiment, which was trained in beach support operations but had neither the experience nor the equipment to carry out this function. Alerted in Sicily only two weeks before the invasion, the 531st traveled to Oran, the staging area for part of the invasion force, while the 540th reported to the assembly area of the 45th Infantry Division around Palermo. Neither regiment participated in the planning for the invasion, nor did their officers see the maps for the operation or the stowage plans for the vessels to be unloaded off the beaches; for the most part, they saw the troops they were supporting for the first time on the sand under German fire.4

In other respects engineer preparations for the Salerno invasion were more thorough. Fifth Army and NATOUSA engineers requisitioned supplies, trained engineer troops, analyzed terrain, and produced detailed maps. After the final selection of the Salerno site the engineer mapping subsection, Fifth Army, studied in detail the terrain of the region, its ridge and drainage systems, communications, water supply, ports, and beaches. These studies gave the engineers vital information for annotating maps.

Planning for engineer supply at Salerno rested ultimately with the engineer of SOS, NATOUSA. On 25 July Maj. Irving W. Finberg, chief of the Fifth Army Engineer Supply Section, reported to the SOS engineer as Fifth Army liaison officer to prepare requisitions covering the estimated needs of Fifth Army engineers. Within two weeks Finberg submitted the basic requirements. Wherever possible, his listing became the basis for freeze orders on SOS, NATOUSA, stocks in North Africa, which eventually reserved 10,545 long tons of engineer supply for the invasion. Base section depots reported items not available in the theater pipeline, and units in the theater not scheduled for the forthcoming operation gave supplies and equipment to units going into the assault. The SOS, NATOUSA, command made up shortages by ordering critical items directly from the New York Port of Embarkation, requisitions amounting to 3,638 long tons. Confusion still reigned in some quarters, especially since engineer, quartermaster, and ordnance supply was intermixed in theater stocks, and inadequate inventory procedures frequently led to ordering materiel already on hand but unidentified.5

As the supply planning and acquisition proceeded, Fifth Army operated eight training schools. At Port-aux-Poules, near Arzew in Algeria, Brig. Gen. John W. O’Daniel opened the Fifth Army Invasion Training Center on 14 January 1943. Relieved of its function in Sicily late in the summer, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade practiced combined operations with naval units and coordinated air cover over beach areas serving the center. The 17th Armored Engineer Battalion, the 334th Engineer Combat Battalion, the 540th and 39th Engineer Combat Regiments, and two separate engineer battalions, the 378th and the 384th, took part in training exercises with live fire, the object being to make men battle-wise in the shortest possible time. Outside the center, elements of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, the 109th Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade headquarters had joint and combined training in beach operations which included mine-clearing work. The 16th Armored Engineer Battalion also ran two mine schools at Ste.-Barbe-du-Tlélat for the men of the 1st Armored Division and organized its own refreshers in infantry tactics, bridging, and field fortifications.

A separate engineer training center opened on 12 March 1943, near Ain Fritissa in French Morocco at an abandoned French Foreign Legion fort. Under Lt. Col. Aaron A. Wyatt, Jr., the school concentrated on practical work under simulated battle conditions. British Eighth Army instructors taught mine and countermine warfare. The final problem, usually undertaken at night, split the students into two groups, one of which planted mines for the second to unearth. Though the mines employed were training devices with only igniter fuses attached, several live and armed standard charges were interspersed with the dummies. As the engineer students struggled in the darkness, assembled tanks and infantry fired 37-mm. shells and automatic and small-arms rounds overhead, and instructors stationed in towers detonated buried artillery shells on the field. By the time

of the invasion over a thousand officers and noncoms had completed the courses at the engineer center, with twenty-seven casualties and one fatality during the exercises.

An adjunct to the center was a research and development staff that investigated and tested new mechanical mine-clearing devices such as the Scorpion flail as it became available from British sources. As soon as they appeared in the theater, the German Schu mines were also the object of the staff’s attention. Though the center operated with unqualified success, it labored constantly under the disadvantages of being an ad hoc organization with no standard organization tables. Originally blessed with one armored engineer company and four combat engineer companies as demonstration units, Colonel Wyatt could rarely keep on hand enough veteran technicians in mine warfare and never had enough transportation.

The engineers produced maps and charts by the thousands for the American invasion force. Originally relying on existing small-scale charts on hand, some of foreign manufacture, the map-makers found their enlargements poor. Urgent requisitions for new maps scaled at the standard 1:25,000, 1:50,000, 1:100,000, and 1:250,000 soon supplied adequate coverage for nearly the whole of the south-central Italian peninsula from the latitude of Salerno to that of Anzio. Larger scale maps, 1:500,000 and l:1,000,000, covered the area north of Rome. Finally the engineers obtained detailed road maps of the Naples area and beach defense overlays for Salerno which gave annotated legends for points of concealment, lines of communications, water supply, and ridge lines in the immediate area of assault. A single map unit, the 2699th Engineer Map Depot Detachment (Provisional), attached to the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment for the operation, spent most of the time before the invasion virtually imprisoned in a large garage in Oran while it packed 1:50,000 and 1:1,000,000 maps, fifty to the sealed roll. The map depot detachment carried enough maps into the invasion to resupply each combat unit with 100 percent of its original issue.

Amphibious exercises in the two weeks before the invasion suffered from too little realism. In COWPUNCHER; run from 26 to 29 August, the 36th Infantry Division acted as attacker at Port-aux-Poules and Arzew against the defending 34th Infantry Division. Loath to expose vessels to enemy submarine attacks during the exercise, the Navy could not support the rehearsal in detail, and only a token unloading of vehicles, supply, and munitions over the beaches was possible. On 29 August Company I, 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, demonstrated beach organization procedure to 1,000 sailors; three days later Company H participated in a simulated beach exercise with the Navy, but no small boats were used. On Sicily, the 45th Infantry Division staged one rehearsal for the coming landing.

The Invasion

On 3 September the British Eighth Army struck across the Strait of Messina, and the long and bitter Italian campaign was under way. On 5 September the first of the invasion convoys for AVALANCHE left Oran and Mers-el-Kebir, and at precisely scheduled

intervals thereafter, convoys moved out of other ports in North Africa and Sicily. They came together north of Palermo and converged on the Gulf of Salerno during the evening of 8 September. Aboard were the U.S. VI Corps’ 36th Division, the British 10 Corps’ 46th and 56th Divisions, three battalions of American Rangers and two of British commandos, and a floating reserve, the American 45th Division less one regimental combat team. The 141st had the southern Yellow and Blue beaches as assault targets; the 142nd was to take the northern Red and Green beaches on the left, closer to the Fiumarello Canal. (Map 8)

Fortune seemed to favor the landings. As the convoys approached the mainland under air cover, the ships’ radios picked up the voice of General Eisenhower declaring that “hostilities between .the United Nations and Italy have terminated, effective at once.” When the assault began shortly before 0330 on 9 September, the weather was good, the sea was calm, and the moon had set. As the first wave of LCVPs carrying VI Corps’ troops grounded south of the Sele River, the men saw flashes of gunfire to the north where the British were landing, but their own beaches were dark and silent. Then, as they were leaving their craft and making their way ashore through the shallows, flares suddenly illuminated the shoreline, machine-gun and mortar fire erupted from the dunes, and from the arc of hills enclosing the coastal plain artillery shells rained down.

The heaviest concentration of German fire fell on the southernmost beaches, Yellow and Blue. The 3rd Battalion of the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, coming in on the second wave in support of the 141st Infantry, was unable to land on Yellow and had to turn to Blue, where things were not much better. No boats could land on Blue after daybreak, and for most of the day the engineer battalion’s Company I was pinned down. At one time the company’s command post was only 300 yards from a point where the infantry was fending off a German attack.

The regiment’s 2nd Battalion, supporting the 142nd Infantry, was able to land on Red and Green beaches. The unit suffered several casualties but reported at 0530 that Red Beach was ready for traffic. Landing craft and DUKWs floundering offshore converged on Red, but the concentration drew heavy artillery fire that knocked many of them out. The disruption made it impossible to open any of the beaches for several hours; much of the engineers’ equipment was scattered or sunk, and the mine-clearing and construction crews could not land as units. The delay in opening the beaches, as well as enemy fire on boat lanes, prevented VI Corps from landing tanks and artillery before daylight, as had been planned.

At daylight another menace appeared. A German tank came down to the shore between Yellow and Blue beaches and fired on each landing craft that approached. More enemy tanks began firing from the main road behind the dunes. The landing parties, without tanks and heavy artillery, had to repel the Germans with 40-mm. antiaircraft guns, 105-mm. howitzers, and bazookas, an effort in which the engineers of the 531st played an important part. When five Mark IV tanks tried to break through to Blue Beach, seven engineers of Company I helped to repel them with bazookas. At Yellow Beach, where

Map 8: Salerno Beached, September 1943

DUKWs head for the Salerno beaches

40-mm. antiaircraft guns and 105-mm. howitzers had been hastily set up at the water’s edge, a bulldozer operator of Company H, T/5 Charles E. Harris, pulled the guns into position in the dune line. He was wounded by machine-gun fire from a German tank but continued to operate his bulldozer until it went out of action. On all the beaches the big bulldozers were easy targets, their operators working under constant fire.

The first beaches open were Red and Green. Not until shortly after noon were landing craft discharging at Yellow, while Blue remained closed most of the afternoon. By nightfall all were in operation, and tanks, tank destroyers, and heavy artillery were landing and moving out of the beachhead. The engineers cut through wire obstructions, laid steel matting, and improved exit roads, while the 36th Division’s infantry regiments advanced inland. That night two companies of the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, landing on D-day as part of 36th Division’s infantry reserve, served as a screen against armor along the Sele River.6

Next morning German planes came over Red Beach and dropped a bomb squarely on the command post of the 531st Engineers’ 2nd Battalion, killing

LSTs and auxiliary ships unload men and supply at Salerno

two officers and seriously wounding two others. Artillery shells also fell on the beachhead, but there was no ground fighting in the American sector near Paestum on 10 or 11 September. The Germans were concentrating their forces in the north against the British 10 Corps.

General Clark became concerned about a group of American Rangers that had landed on the west flank of 10 Corps on the Sorrento peninsula between the tiny ports of Amalfi and Maiori to help the British secure the mountain passes leading to Naples. On Clark’s orders a task force built around an infantry battalion moved by sea from the VI Corps’ beaches to support the Rangers. Aboard the eighteen landing craft that started north on 11 September were two companies of engineers, one from the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment and the other from the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, the latter having landed with the 45th Division on D plus 1.7

The bulk of the 540th pitched in to aid the 531st in organizing the beaches. Goods of all description crowded the shoreline, barracks bags accumulated on the narrow beachhead, and the congestion finally forced the closing of Red and Green beaches. Unsorted stacks of ammunition, gas, food, water, and

equipment extended seaward into several feet of water, while ships offshore could not unload. This situation improved somewhat after a new beach, Red 2, opened to the left of Red Beach and north of the Fiumarello Canal.8

Naval officers criticized engineer operation of the beaches and attributed traffic jams to poor beach exits and the failure of some engineers to make adequate arrangements to transfer supplies from the beaches to dispersal areas farther inland. A major Navy complaint was that Navy boat crews had to do most of the unloading with little assistance from the engineers, whose responsibility it was. The Navy beach-master estimated that during the assault phase Navy crews unloaded or beached 90 percent of the supplies and equipment.9

In fact, the beach engineers could not possibly have handled all the tonnage that came to the beaches during the assault phase. Combat units and equipment grew out of all proportion to service troops. The 531st went ashore on the morning of D-day more than 200 men understrength and soon was weakened further by casualties. To assist the 531st in unloading, setting up dumps, maintaining roads, and clearing minefields, a battalion of the 337th Engineer General Service Regiment, a Fifth Army unit, landed on Red Beach at 1630 but could accomplish little because its equipment did not come in for several days. Both the 531st and the 540th Engineer Regiments arrived short of equipment, notably mine detectors and trucks. Few engineer supplies began arriving before D plus 1, and most of what came in was not what was most wanted. The first engineer supply item ashore was a forty-gallon fire extinguisher, while other items landed early were sandbags, lumber, and tools. Later, a few cranes came in. Once ashore, the two regiments felt they did not get enough information from the Navy beachmaster as to what LSTs or cargoes were arriving and where they would land. As in TORCH and HUSKY, the line between Army and Navy responsibility remained vague.10

The Fifth Army engineer, Colonel Bowman, came ashore on D plus 1 and set out in a jeep to find a suitable place for the army command post. He turned north from the congested beachhead, and near the juncture of the Sele and Calore Rivers, not far from the boundary between VI Corps and 10 Corps, he found the house of Baron Roberto Ricciardi, set in a lovely Italian garden.

In the next three days, the sound of artillery fire in the north, where the Germans were concentrating against 10 Corps, came close; and it was in this sector between the two corps that engineer troops first manned frontline positions. On a warning from General Clark that a German counterattack might hit the north flank, the VI Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley, reinforced two regiments of the 45th Division with the 3rd Battalion of the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment. The

engineers moved into the line a few miles north of the Sele River shortly after midnight on 12 September, along with a battery of 105-mm. howitzers; by dawn they were in contact with British 10 Corps patrols. At 1000 the division launched an attack. The Germans counterattacked with tanks and artillery, killing two engineer officers, and by dusk had infiltrated and cut off a forward body of engineers that included the battalion commander. The engineer regimental commander, Lt. Col. George W. Gardes, took over the battalion. Before daybreak on 13 September the battalion attained its objective, which turned out to have been one of the strongpoints of the German defense system.11

During 12 September German fire increased in the American sector and an enemy attack dislodged a 36th Division battalion from its position on hills near Altavilla, south of the Calore River. The increased German pressure resulted from the reinforcement of the 16th Panzer Division, which had borne the full force of the invasion, by the 29th Panzer Division, moving up from Calabria. Not only divisional engineers of the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion but also corps and even army engineers bolstered 36th Division defenses. On 13 September two battalions of the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment were called off beach work for combat. One went inland to act as reserve, the other took up defensive positions on high ground south and southeast of the beachhead.12

The situation worsened during the day, indicating that the Germans were trying to break through to the beachhead, and the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment had to furnish another battalion to act as infantry. Moving out at midnight, the regiment’s 2nd Battalion occupied high ground along the south bank of the Galore River astride a road leading into the beachhead from Alta-villa. This position came under heavy artillery fire throughout 14 and 15 September, and tank and infantry attacks also menaced it. On the afternoon of 14 September German tanks clanked over a stone bridge spanning the Calore and began to move up a narrow, one-way road winding toward the engineers’ position. The engineers were ready for them. From a quarry recessed into the hillside, they fired a 37-mm. cannon and a .50-caliber machine gun pointblank at the lead tank, knocking it out to form a roadblock in front of the following tanks, which then withdrew under American artillery fire. The next afternoon the engineers saw German infantrymen getting off trucks on the north side of the river, apparently readying for an attack. The engineers brought the German infantry under fire, inflicting observed losses.

In the 45th Division sector north of the Sele River, a tank-infantry attack hit the 3rd Battalion, 36th Engineers, on 14 September. German tanks overran part of one company’s position, but the engineers stayed in their foxholes and stopped the following infantry while U.S. tank destroyers engaged the tanks. Another company of the 3rd Battalion stopped a Mark IV tank with bazookas and that night captured a German scout car and took three prisoners. During the day the battalion was reinforced by part of the 45th Division’s 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, all

of which had operated as infantry since 13 September.13

General Clark, who had hastily moved Colonel Bowman’s command post to the rear, was so concerned about a German breakthrough to the beachhead that at one point on 13 September he contemplated a withdrawal to the 10 Corps’ zone. But the lines held long enough for reinforcements to come from Sicily. Parachute troops of the 82nd Airborne Division, dropped on the beachhead in the early hours of 14 September and trucked to the southern flank, turned the tide. When the 3rd Infantry Division began landing from LSTs on the morning of 18 September the enemy was withdrawing.14

Plans for the advance beyond Salerno were determined at a conference General Clark called on 18 September. Naples on the west coast, one of the two prime objectives, was to be the target of Fifth Army; the other objective, the airfields around Foggia near the east coast, was to be the target of General Montgomery’s Eighth Army, which by 18 September was in a position-to move abreast of Fifth Army up the Italian peninsula. In the Fifth Army effort, 10 Corps was to move north along the coast to capture Naples and drive to the Volturno River twenty-five miles beyond while VI Corps made a wide flanking movement through the mountains to protect the 10 Corps advance.

A Campaign of Bridges

In addition to active German resistance, terrain was a principal obstacle in the flank march that opened on 20 September. Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas took over the VI Corps advance just as it started, arraying the 3rd Division on the left and the 45th on the right, but found his troops entirely road-bound. Italian terrain was far worse for military maneuver than that in Sicily; cross-country movement was next to impossible, not only over mountain heights but even in the valleys, where vehicles were likely to be stopped by stone walls, irrigation ditches, or German mines. The enemy had blown all the bridges carrying roadbeds over the numerous gullies, ravines, and streams. Forward movement in Italy became for the engineers a campaign of bridges.

According to policies Colonel Bowman laid down, divisional engineers were to get the troops across streams any way they could: bypasses when possible, fills when culverts had been blown, or Bailey bridging. Corps engineers were to follow up, replacing the small fills with culverts and the bypasses with Bailey bridges. Army engineers were to replace the larger culverts and the Baileys with fixed pile bridges. All bridges were to be two-way, Class 40 structures.

Even veteran units had rough going. The 10th Engineer Combat Battalion, supporting the 3rd Division in the advance to the Volturno, was the battalion that had built the “bridge in the sky” in Sicily. The divisional engineers of the 45th Division, the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, had also had hard service in the mountains during the Sicily campaign. The corps engineers behind them came from the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, which had distinguished itself in the defense of

the beachhead. Yet it took these experienced, battle-hardened engineers ten days to get the troops sixty miles over the mountains to the first major VI Corps objective, Avellino, a town about twenty-five miles east of Naples on the Naples-Foggia road.

The Germans had blown nearly every bridge and culvert, made abatis of tree trunks, sown mines, and emplaced booby traps. Demolitions, shelling, and bombing had cratered road surfaces. In the towns, rubble from destroyed stone buildings blocked traffic. But the weather was still good, so engineers could bulldoze bypasses around obstructions. “There was no weapon more valuable than the engineer bulldozer,” General Truscott attested, “no soldiers more effective than the engineers who moved us forward.” Bypasses around blown bridges saved the time required to bring up bridging. In the advance to the Volturno the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion constructed sixty-nine bypasses but only a few timber and Bailey bridges.15

The Bailey seemed made for the steep-banked, swiftly flowing rivers and the narrow gorges of the Italian countryside. It could be launched from one side or bank without intermediate supports. In the early phase of the Italian campaign the Germans did not comprehend its potential, so they were satisfied with destroying only parts of long bridges instead of all the spans and piers. The engineers quickly used those parts left standing to throw a Bailey over a stream or ravine.16

The Bailey became all the more essential when the engineers discovered that timber for wooden bridges was scarce, at times as much as seventy-five miles distant. Yet the supply of Baileys was woefully inadequate. The 36th Engineer Combat Regiment built more than eighty bridges and sizable culverts between the breakout at Salerno and the end of December but during that time received only three Baileys.17 In the first month after the landings, the Fifth Army engineers had only five sets of the much sought after 120-foot double-double Baileys.

One major reason for the shortage of bridging in this early stage of the Italian campaign was a faulty estimate by planners at AFHQ. They had foreseen that highway destruction would be tremendous, had assumed that the enemy would demolish all bridges, and had figured that an average of thirty feet of bridging per mile of main road would be required. But the estimate did not take into account the secondary roads that had to be used to support the offensive.18

A shortage of bridge-building material and heavy equipment also hampered the work of engineers building a bridge over the Sele River to carry Highway 18 traffic northward from the beachhead to Avellino. This bridge was crucial because the beaches continued to be the main source of supplies for Fifth Army for a considerable time after Naples fell.

A company of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion put in the first bridge over the Sele, a floating treadway, on 10 September. It was replaced the following day

by a 120-foot trestle tread-way to carry forty-ton loads. During 12 and 13 September a battalion of the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment emplaced two more floating bridges, and on 22 September the 337th Engineer General Service Regiment began building the first fixed bridge the U.S. Army constructed in Italy over the Sele. It was of trestle bent construction, 16 spans, and 240 feet long. In spite of the equipment shortage, the job was completed by 28 September.19

However, the bridge was undermined by the shifting sands of the river bottom and from the start required constant maintenance. When heavy rains fell early in October, making a rushing torrent of the normally sluggish Sele, the bridge went out. The 531st Engineer Shore Regiment altered the railroad bridge over the Sele to take trucks so that the vital supply line would not be interrupted. Then they repaired the road bridge by driving piling through the floor and jacking the bridge up and onto the new pile bents. After this experience, engineers abandoned trestle construction in favor of pile bridges. In the construction of a 100-foot pile-bent bridge about halfway between Salerno and Avellino, near Fisciano, the engineers of the 531st improvised a pile driver, using the barrel of a German 155-mm. gun and a D-4 tractor.20

Naples

When Naples fell on 1 October 1943, Fifth Army’s supply situation was deteriorating rapidly. Truck hauls from the Salerno beaches were becoming longer and more difficult. Unloadings over the Salerno beaches were at the mercy of the elements, and the elements had just struck a blow for the enemy. A violent storm that blew up on 28 September halted unloading for 2½ days and wrecked a large number of landing craft and ponton ramps. Supplies dwindled. On 6 October the army had only three days’ supply of gasoline, and during the first half of October issues of Class I and Class III supplies from army dumps outstripped receipts. The early reconstruction of Naples and of transportation lines was of prime importance.21

Naples, with a natural deep-water harbor, was the second ranking port in Italy and had a normal discharge capacity of 8,000 tons per day.22 The water alongside most of its piers and quays was thirty feet deep or more, enough to accommodate fully loaded Liberty ships. There was virtually no tide; the water level varied only a foot or two, a result of wind swell as much as tidal action.

Naples was the most damaged port U.S. Army engineers had yet encountered during the war. Allied aerial bombardment had probably caused one-third to one-half the destruction in the port area and more than half that in the POL tank farm and refinery areas. Carefully planned German demolition had been effective. Damage to the quays

and piers was slight, for they were built of huge blocks of masonry and not easily demolished. Most of the damage to them came incidentally from demolitions that destroyed pier cranes and other port-operating equipment. The Germans had directed their destruction toward cargo-handling equipment, and they blocked the waters with every piece of once-floating equipment available. When Fifth Army troops entered the city, thirty-two large ships and several hundred smaller craft lay sunk in Naples harbor, blocking fifty-eight of the sixty-one berths available and cutting the normal capacity of the port by 90 percent.23

On the land side, a wall of debris isolated the dock area from the rest of the city; Allied bombing and German demolitions had destroyed most of the buildings near the docks. Only steel reinforced buildings stood, and most of them were badly damaged and littered with debris. The enemy destroyed all of some 300 cranes in the port area; in many cases the demolition charges were placed so as to tip the structure into the waters alongside the quays. Tons of rubble from nearby buildings were also blown into the water to block access to the quays.24

Despite the widespread destruction, engineer and survey parties had reasons for optimism. Sea mines were found only in the outer harbor. Also, the enemy had sunk ships adjacent to the quays or randomly about the harbor, not in the entrance channels where they could have denied the Allies use of the port for weeks, perhaps months.

Within the city debris blocked several streets. Rails and bridges on the main lines had been systematically destroyed. Ties and ballast, on the other hand, were generally undisturbed in Naples itself. Most of the large public buildings were either demolished or gutted by fire, and others were mined with time-delay charges. Large industrial buildings and manufacturing plants generally were prepared for demolitions, but most charges had not been fired. No booby traps were found in the harbor area and not a great many throughout the city.

Public utilities—electricity, water, sewage—were all disrupted. With the great Serino aqueducts cut in several places, the city had been without water for several days, for most of the wells within the city had long since been condemned and plugged. The only electricity immediately available came from generators Allied units brought in. Local generating stations were damaged, and transmission lines from the principal source of power, a hydroelectric plant fifty miles south of Naples, were down. The distribution system within the city was also damaged, and demolitions had blocked much of the sewer system.

Fifth Army engineer units entering the city from the land side started clearing debris from the port. Detachments of the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion (divisional engineers of the 36th Division) went to work clearing a road around the harbor. The 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, bivouacking in a city park overlooking the Bay of Naples, had the job of clearing the harbor. With dynamite, bulldozer, torch, crane,

and shovel, the men of the 540th filled craters, hacked roads through debris, cleared docks, and leveled buildings. Within twenty-four hours the harbor was receiving LSTs and LCTs, and exit roads were making it possible for DUKWs to bring cargoes inland from Liberty ships in the bay.25 The 1051st Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group, attached to the Fifth Army Base Section, arrived on 2 October but could do little more than survey the chaos until base engineer troops came on the scene.

The engineers working on the docks undertook their tasks in three phases. The first, based on quick estimates, was the clearing of debris to provide access to those berths not blocked by sunken ships. The second involved expedient construction, and this the engineers undertook after a reasonably comprehensive survey made it feasible to plan for future activities. The third phase, reconstruction, involved more time-consuming projects that started only after the possibilities of providing facilities by expedient construction had been exhausted.

The first phase, which occurred from 3 to 5 October, was the most critical one. Since demands for berthing and unloading space were urgent, there was no time for deliberate, planned activity. All available army and base section engineers and equipment had to be committed against obstacles blocking the initial unloading points. Navy salvage units, equipped with small naval salvage vessels and aided by Royal Navy salvage units with heavy lifting equipment, entered the harbor on 4 October to locate ships and craft that obstructed berthing space. Coordinating with the naval units, the 1051st Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group surveyed landward obstructions.

Although only 3½ Liberty berths were available on 7 October, berthing space grew rapidly with the expedient construction. On 16 October, 6,236 tons of cargo came ashore, a figure that included 263 vehicles. By the end of the month 13½ Liberty berths and 6 coaster berths were available for use (the goal set early in October was 15 Liberty berths and 5 coaster berths by 1 November). The most urgent requirements had been met, and supplies in the dumps amounted to 3,049 tons.

Ramps of standard naval pontons, laid two units wide, were built far enough out into the harbor to accommodate Liberty ships. These ramps were easy to build and feasible enough in tideless waters, but they were too narrow for cargo and were used only for unloading vehicles. More widely used were steel and timber ramps which engineers were able to construct across the decks of sunken ships alongside the piers. These ramps became the trademark of the engineers in the rehabilitation of Naples.

All but two of the large ships blocking the piers were too badly damaged to patch and float aside immediately; but most of them lay alongside the quays, with their decks above or just below the surface of the water. When engineers cleared away the superstructures and built timber and steel ramps across the decks, Liberty ships could tie up alongside the sunken hulks and unload directly onto trucks on the ramps. As a rule T-shaped ramps ten to fifteen feet wide were built at each berth and spaced

Decking placed over sunken vessels to enable loading in Naples harbor

to correspond with the five hatches of a Liberty ship. The head of the T was twenty to twenty-five feet long, allowing room on the ramp for temporary cargo storage and for variations in the spacing of hatches on individual ships. At first these ramps went out only over ships sunk on an even keel; later they were built on ships that lay on their sides or at an angle to the quay. Eventually engineers filled the spaces between the ramps with decking to provide more working room.

Another improvisation made the larger of two dry docks into a Liberty berth. The caisson-type gates had been damaged and two ships lay inside the dock. Leaks in the gate were sealed with tremie concrete, which cures under water, and the ships were braced to the sides of the dock. The basin was then emptied so the ships could be patched. Since the walls of the docks were not perpendicular, steel scaffolding had to be built out over the stepped masonry walls and covered with timber decking. After the ships were refloated and pulled away, both sides of a Liberty ship could be unloaded at the same time in the dry dock. The smaller dry dock was used for ship repairs once a sunken destroyer had been patched and floated out.

At the foot of one pier a cargo vessel lay sunk with one side extending eight to ten feet above water. The vessel was flat bottomed, so a Liberty ship could come in close alongside. Engineers built

General Pence

a working platform on the ship with a bridge connecting to the pier. At another pier, where a large hospital ship lay sunk with its masts and funnels resting against the quays, walkways and steps leading across the hulk and down to the pier made a berth for discharging personnel.

Clearing away underwater debris also released berthing space. Floating and land-based cranes removed debris along the piers and quays, while port construction and repair group divers went down to cut loose sunken cranes and other steel equipment.

Peninsular Base

With the arrival of more service troops from North Africa, the Fifth Army Base Section assumed more responsibility for supply in the army’s rear. Through summer 1943, Fifth Army’s support organization was only a skeleton, designated 6665th Base Area Group (Provisional) and modeled after the NATOUSA Atlantic Base Section. It changed its provisional character and its name to the full-fledged Fifth Army Base Section on 28 August. Under Brig. Gen. Arthur W. Pence, an advance echelon accompanied Fifth Army headquarters to Italy, landing at Salerno on D plus 2. General Pence established his headquarters at Naples the day after the city was captured, and on 25 October his command became the Peninsular Base Section, with its Engineer Service under Col. Donald S. Burns.26

By 10 October the first full-sized convoy brought the 345th Engineer General Service Regiment to the base section. The Base Section Engineer Service also had at its disposal the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, two engineer general service regiments (the 345th and 94th), the 386th Engineer Battalion (Separate), one company of a water supply battalion (attached from Fifth Army), an engineer port construction and repair group, an engineer maintenance company, a depot company, and a map depot detachment—in all, about 6,000 engineers.27

Colonel Burns ran all engineer functions in the base section area, was responsible

for building and operating bulk petroleum installations, and was also responsible for new railroad construction without regard to the army rear boundary. When the army’s advance was slow, base section engineers were able to carry both pipeline and railroad work well into the army area. As for air force construction, the Engineer Service was responsible not only for bulk POL systems in the vicinity of airfields, but it also was to provide common engineer supplies to aviation engineers operating in the area. All engineer units assigned to the base area, except for fire-fighting detachments (under the base section provost marshal), were under the command of the base section engineer.28

The Engineer Service had six branches: administration, operations, construction, supply, real estate, and petroleum. An important function of the administrative branch involved negotiating with the Allied Military Government Labor Office (AMGLO) and with the labor administration office of the base purchasing agent for civilians to work with engineer units and for office personnel to work at engineer headquarters. By the end of 1943 3,126 civilians worked directly for engineer units or on contracts the base section engineers supervised. Workers employed by individual engineer units were paid semi-monthly by specially appointed agent finance officers at wages the AMGLO established.

The operations branch was responsible for issuing administrative instructions to engineer units, coordinating engineer troop movements, and keeping strength, disposition, and status reports of personnel and equipment. It also issued orders to engineer units for minefield clearance.

The construction branch, heart of the Engineer Service organization, applied the Engineer Service’s resources against the mass of requests for construction that poured in. It provided technical assistance to engineer units, allocated priorities among jobs, and established and enforced standards of construction. The number of jobs was staggering: reconstructing the Naples port area; restoring public utility services in Naples and removing public dangers such as time bombs and building skeletons; reopening lines of communications; providing troop facilities such as hospitals, rest camps, replacement camps, quarters, stockades and POW enclosures, laundries, and bakeries; building supply depots and maintenance shops; and helping local industries get back into production.29

The supply branch received material requirements estimates from the Fifth Army engineer, the III Air Service Area Command, the petroleum branch, and, later, from the various branches of the Engineer Service, Peninsular Base Section. It consolidated these requisitions for submission to the engineer, SOS, NATOUSA, through the base section supply office (G-4). Fifth Army had requisitioned supplies for a thirty-day maintenance period and had forecast its needs through November. Thereafter, responsibility for requisitioning engineer supplies rested with

the base section engineer. Except for emergency orders, engineer requisitions were submitted monthly and were filled from depots in North Africa; items not available there were requisitioned from the New York POE. The supply branch also coordinated local procurement.

Responsibility for requisitioning real estate for all military purposes in connection with U.S. base section forces also rested with the engineer. Ultimately, a separate real estate branch was established.

The designation of a petroleum branch underscored the importance of this new engineer mission. POL products represented nearly half the gross tonnage of supplies shipped into Italy, and engineer pipelines were the principal means for moving motor and aviation gasoline once it was discharged from tankers at Italian ports.30

Petroleum, Oil, and Lubricants

Petroleum facilities in Naples were heavily damaged. Allied bombers had hit the tank farms as early as July 1942, and many tanks and connecting pipelines had been pierced by bomb fragments; others had buckled or had been severed by concussion. German demolitionists had added some finishing touches at important pipe connections, discharge lines, and tanker berths. However, existing petroleum installations in Naples were large and much could be salvaged.31

Sixteen men from the 696th Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company entered Naples on 2 October. This advance party surveyed existing installations, recruited civilian petroleum workers, and began clearing away debris and salvaging materials. The 345th Engineers furnished teams of mine sweepers. After the main body of the 696th arrived two weeks later, the connecting pipelines in the terminal area were traced, patched, cleaned, and tested, and new threaded pipe was laid. One after another the huge steel storage tanks were patched and cleaned. This work often involved cutting a door in the bottom of a tank, shoveling out accumulated sludge, and scrubbing the walls with a mixture of diesel oil and kerosene.

Some of this early work proved wasteful. It began before any master plan for the POL terminal was available. Engineers repaired some tanks with floating roofs before they discovered that the tanks were warped. The 696th had no training or experience in such work, and plates welded over small holes cracked when they cooled until the company learned how to correct the problem. Other practices, such as the best method for scrubbing down tanks, had to come from trial and error.32

Not until 24 October did the 696th company have the terminal ready to receive gasoline, and the first tanker, the Empire Emerald, did not actually discharge

Engineer officer reads pressure gauges at pumping station, Foggia, Italy

its cargo until five days later. In the meantime engineers set up dispensing and refueling stations in the terminal area, and once the Empire Emerald discharged, Fifth Army and base section units were able to draw some of their fuel supply from the bulk installations. The petroleum engineers did not limit their operations to providing facilities for ground force units. The 696th company readied separate lines and storage tanks to receive 100-octane aviation fuel, as well as storage tanks, discharge lines, and fueling facilities for naval forces.

The engineer work to make possible the discharge of POL and other supplies at Naples became increasingly urgent as October advanced. By the end of the first week in October advance elements of Fifth Army were at the Volturno River, and a week later the crossings began.

The Volturno Crossings

To the engineers involved in getting the troops across the river, where all bridges were down, the most important feature of the Volturno was that it was shallow. From 150 to 220 feet wide, the river was normally only 3 to 5 feet deep; even after the rains of early October began, spots existed on the VI Corps front where men could wade across and tanks could ford. The VI Corps crossings were to be made by the 3rd and 34th Divisions abreast between

Triflisco (the boundary with British 10 Corps on the west) and Amorosi, where the Volturno, flowing down from the northwest, joins the Galore and turns west toward the sea. The corps’ 45th Division was east of Amorosi in a sector adjoining British Eighth Army and would not be involved in the Volturno crossings.

By 6 October the 3rd Division was at the river, but for days rains and stiffening German resistance made it impossible to bring up the 34th Division, as well as 10 Corps, which was to cross simultaneously with VI Corps. Flooded swamplands and enemy demolitions held the British back; and in the path of the 34th Division the fields were so deep in mud that cross-country movement was impossible. Punishing military traffic deepened the mud on the few roads and continually ground down and, destroyed surfaces already cratered from heavy shelling. Enormous quantities of gravel and rock had to be used, even timber for corduroy cut from the banks of the Volturno.33

The 3rd Division made good use of the week’s delay. Reconnoitering the banks, patrols found wheel tracks where the Germans had crossed. At night patrols waded or swam the Volturno and marked fording spots. The troops were to cross in assault boats or wade, in either case holding on to guide ropes anchored to trees on the opposite bank. Heavy weapons were to be carried in assault boats. The 3rd Division’s 10th Engineer Combat Battalion rounded up five miles of guide rope and found some life jackets in a Naples warehouse. Some assault boats had to be improvised. Naval officers in Naples provided some life rafts; other rafts were manufactured and floated by oil or water drums; and rubber pontons from treadway bridges came in handy.

At the place where waterproofed tanks were to ford, the engineers built a road to the riverbank. Bridges would be required for vehicles unable to ford. A railway yard in the neighborhood yielded material for a prefabricated cableway and some narrow-gauge railroad track which, overlaid with Sommerfeld matting and supported by floats, made a usable bridge for jeeps.34

Waiting on the mountain heights beyond the now racing, swollen Volturno, the Germans were prepared to repel the crossings. They had emplaced heavy artillery, laid mines, dug gun pits, and sighted machine guns to cover the riverbanks with interlocking fields of fire. They killed many men probing for crossing sites, but still did not know where the attack would come. General Truscott misled them into thinking the main crossing would be made on the American left at Triflisco Gap, then crossed the river in the center, spearheading the advance with the 7th Infantry of his 3rd Division.

At 0200 on 13 October, after a heavy preliminary bombardment of German positions, troops of the 7th Infantry entered the river under a smoke screen, one battalion in rafts and assault boats,

two battalions wading the icy waters and holding their rifles above their heads. The men in the boats had the worst of it; many of the trees anchoring the guide ropes tore away from sodden banks; rafts broke up in the swift current; and the rubber boats tended to drift downstream and were held back only with great difficulty by a party from the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment. Despite the struggle against the river, daylight found all the combat troops of the initial waves on the far bank picking their way through the minefields.

By 0530 General Truscott had word that all of the 7th Infantry was over the river and that two battalions of the 15th Infantry had crossed in the same manner and with much the same problems. On the right of the 3rd Division two battalions of the 34th Division had crossed the Volturno with relative ease.

Truscott’s main worry was a delay in getting the tanks across. At the ford in the 7th Infantry sector, bulldozer operators at first light had begun trying to break down the riverbank so the tanks could get to the water’s edge without tipping over; but the bulldozers were unarmored, and enemy shelling caused so many casualties among the operators that the work stopped. Around 1000, Truscott learned from the commanding officer of the 7th Infantry, Col. Harry B. Sherman, that German tanks were advancing toward the riflemen on the far bank and that the enemy was probably about to launch a counterattack.

Leaving Sherman’s command post, Truscott encountered a platoon of engineers from Company A of the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion on their way to the site where work was starting on the division bridge. “In a few brief words,” Truscott later recalled, “I painted for them the urgent need for courageous engineers who could level off the river bank even under fire so that tanks could cross and prevent our infantry battalions being overrun by the enemy. Their response was immediate and inspiring. I left them double-timing toward the river half a mile away to level off the bank with picks and shovels—which they did, while tanks and tank destroyers neutralized enemy fire from the opposite bank.35 By 1240 fifteen tanks and three tank destroyers had reached the opposite bank and were moving to the aid of the riflemen.

By that time the jeep bridge in the 7th Infantry area, being built by Company A of the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion, was almost finished. But work the battalion’s Company B was doing on the division bridge in the 15th Infantry area to the east had been stopped by German artillery fire, which caused casualties among the engineers, punctured pontons, and damaged trucks. General Truscott hurried to the site and told the engineers they would have to disregard the shelling and finish the bridge. The company “returned to work as nonchalantly as though on some engineer demonstration” and completed the bridge that afternoon, although shelling continued to cause casualties.36

Sites for the division bridge and for a thirty-ton bridge to carry tanks, corps artillery, and heavy engineer equipment had been selected entirely from aerial photographs. Later, ground reconnaissance

justified this method of selection.37

The thirty-ton corps bridge went in near Capua about 500 yards from a blown bridge that had carried Highway 87 across the river at Triflisco. Aware that this site was the only one suitable for a heavy bridge, the Germans stubbornly dominated the heights all through the day on 13 October, and not until the next day could work begin. To build the 270-foot-long treadway VI Corps had to call on the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, which had tread-way equipment and experienced men. Engineers from the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion and the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment prepared the approaches across muddy fields connecting the bridge with Highway 87. Construction began under a blanket of smoke which seemed to draw artillery fire. In spite of casualties and damaged pontons the engineers finished the treadway early in the afternoon, in only six hours. Later that same afternoon General Clark changed the boundary between VI Corps and British 10 Corps, giving the British responsibility for the 3rd Division’s objective on the left flank. This change gave the bridge to the British. In its first five days the tread-way carried 7,200 vehicles across the Volturno.38

In the 34th Division’s zone to the east, south of Caiazzo, the task of building a division bridge over the Volturno fell to Company A of VI Corps’ 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, the regiment that had helped repel German counterattacks after the Salerno landing and had contributed its Company H to the Rangers at Amalfi. Company H had marched into Naples with the Rangers to clear mines and booby traps. At the Italian barracks where the company was billeted, a German delayed-action demolition charge exploded on 10 October, killing twenty-three men and wounding thirteen.39

Misfortune also dogged the efforts of Company A to build the division bridge over the Volturno at Annunziata. According to plan, infantrymen on the far bank were to have taken a first phase line, including heights where German artillery was emplaced, before the engineers moved forward to the river from their assembly area three miles to the rear. On orders, the engineer convoy got under way at 0700 on 13 October, with trucks carrying floats already inflated to save time. But the high ground had not yet been taken, and no one had informed the engineers.

At Annunziata an enemy barrage began, and by the time the first three floats were launched the German fire had become so accurate that all were destroyed. During the day engineer casualties amounted to 3 men killed, 8 wounded, and 2 missing. Not until well after dark did the infantrymen take the first phase line. By that time the engineers had found another site upstream. Working under a smoke screen that (as at Triflisco) attracted enemy fire, they were able to finish the bridge by midmorning on 14 October. That afternoon a company of the 16th Armored

Wrecked M2 floating treadway on the Volturno

Engineer Battalion began building near Caiazzo a 255-foot, 30-ton treadway bridge and finished it before midnight. Next morning, although German planes made several passes at it, the bridge was carrying the 34th Division’s heavy vehicles over the Volturno.40

From the time troops crossed the lower Volturno at Capua and Caiazzo to the time they crossed the upper Volturno a few weeks later at Venafro and Colli, the engineers were so short of bridging material that they had to resort to low-level bridges, sometimes constructed of any material they could scrounge from the countryside. They speedily slapped temporary bridges (largely treadways) across the river. Flash floods in November and December washed them out. On one occasion when the Volturno rose eighteen feet in ten hours, all the bridges but one were out for some time. Alternate routes—long, difficult, and circuitous—slowed supplies and added to traffic congestion. The one bridge sturdy enough to resist the torrent was a semi-permanent structure the 343rd Engineer General Service Regiment built at Capua between 16 October and 9 November. This pilebridge was for six months thereafter a major link in the

Fifth Army lifeline. It was 32 feet high, some 370 feet long, and was classified as a two-way Class 40, one-way Class 70 bridge. In the first twenty-four hours after the bridge opened to traffic, 10,000 vehicles crossed; during the campaign, a million.41

In spite of this experience at the Volturno the engineers built a number of temporary bridges too low to withstand the swift currents of Italian streams and lost several more to flash floods. Any floating bridge was built at the existing level of the river or stream. As the rivers rose or fell, floating or fixed spans had to be added or removed. When Italian streams rose rapidly the engineers could not always extend the bridge fast enough to save it. The height of the bridge also depended upon the availability of construction materials, hard to come by in Italy. As the supply of Baileys improved, longer and higher structures were built.42

During the early part of November the enemy reinforced his units in front of the Fifth Army in an attempt to establish and hold the “Winter Line,” increasing their strength from three to five divisions. By 15 November the British 10 Corps was stopped on a front approximately sixteen miles from the sea to Caspoli, while VI Corps was stalled on a front extending through the Mignano Gap past Venafro and north to the Eighth Army’s left wing near Castel San Vincenzo. General Alexander called a halt and General Clark set about regrouping Fifth Army. Allowing the 34th and 45th Divisions time to rest and refit, he sent the 36th Division into the line and withdrew the 3rd Division, which, slated for Anzio, came to the end (as General Truscott remarked) of “fifty-nine days of mountains and mud.”43