Chapter 3: The Fall of the Philippines

When Japanese fighters and bombers struck at the Philippines, a few hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the engineers in those islands were building airfields and strengthening fortifications. Mobilization of engineer units of the Philippine Army was under way, and stocks of supplies and equipment were being increased. After the Japanese landed, the engineers strove to delay their advance by blocking roads and wrecking bridges. They strengthened Philippine defenses by erecting field fortifications, keeping open lines of communication, providing maps, and building in rear areas. Toward the end, the engineers became infantrymen. Determined effort and devoted service could not prevent the tragic outcome. Like the other defenders of the Philippines, the engineers were not prepared to withstand the Japanese forces.

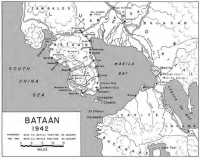

Before World War II it had not been U.S. policy to maintain a strong force in the Philippines, and, apparently, the War Department had no plan for sending reinforcements if war broke out. War Plan ORANGE-3 (WPO-3), the Philippine Department’s defense plan being prepared in 1940, stipulated that if the American and the Filipino forces could not beat off an invasion at the beaches, they were to withdrew to Bataan Peninsula. (Map 5) There and on Corregidor they were to make a 6-month stand and thus deny the enemy access to Manila Bay. Although it was widely assumed that help would reach the beleaguered defenders within six months, WPO-3 made no mention of reinforcements from the United States.1

Late in 1940 the War Department’s policy regarding the Philippines began to change. Among the men responsible for modifying the War Department’s policy was Maj. Gen. George Grunert, who had become commander of the Philippine Department in June of that year. His insistent pleas for reinforcements at length led the War Department to make a beginning toward bolstering the islands’ defenses. Also influential was General Douglas MacArthur, since 1935 military adviser to the Philippine Government. In February 1941 he informed Marshall of his rather extensive plans for building up the military forces of the commonwealth. There was henceforth an increasing emphasis in Washington on strengthening the defenses of the islands. By the summer of 1941 the General Staff believed the Philippines might be reinforced to the

Philippine Islands

point of not only being able to hold off an invasion, but also, of deterring Japanese expansion southward. Perhaps a deciding factor in altering American policy was the successful development of the B–17 heavy bomber. Now for the first time the Army had a weapon which, if based in the Philippines, could deliver effective blows against the Japanese.2

In line with the new policy of strengthening the Philippines, President Roosevelt on 26 July 1941 established in the islands an overall command, United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). Headed by General MacArthur, who had been recalled to active duty in the United States Army, the command included both the Philippine Department and the Philippine Army. MacArthur had in mind not merely holding Bataan Peninsula and Manila Bay. With an increasing number of B-17’s at his disposal and with a Philippine Army of some 125,000 men to be mobilized by the end of the year and an even larger force in prospect, he believed he could successfully defend the entire archipelago, provided he had time to complete his preparations. On October he asked permission to prepare a new war plan to replace WPO-3, and early in November Marshall told him to proceed. The outbreak of war one month later found MacArthur in the midst of revising his plans for defense.3

Preparations f or Defense

Plans and Appropriations

The decision to reinforce the Philippines placed a heavy load on the engineers. Col. Henry H. Stickney, an officer of long experience, who had become department engineer in May 1940, had only a small staff to supervise construction, supply, and map making. MacArthur had no engineer in USAFFE until October 1941, when Lt. Col. Hugh J. Casey arrived from the United States. Colonel Stickney thus directed the engineer effort during most of the prewar period. Construction was to be his first concern.

Earliest efforts were aimed at strengthening the harbor installations in Manila and Subic Bays. Guarding the entrance to Manila Bay were four fortified islands, Corregidor, Caballo, El Fraile, and Carabao. Guarding Subic Bay was Grande Island. Corregidor claimed the major share of attention. Construction there, begun in 1904, had continued until after World War I. The result was a maze of defensive works—tunnels, artillery batteries, communications centers, and shops. The island appeared to be impregnable against any probable naval attack, but little, if any, consideration had been given to defense against aerial bombardment. Corregidor’s fortifications were becoming obsolete and the same was true of the defenses of the other fortified islands. During the twenties and thirties appropriations for the fortified islands were pitifully meager.4 For

the fiscal years 1939-41 inclusive, funds allotted to the Army for harbor defense projects amounted to but $39,000 annually; in May 1939, however, the Navy transferred $500,000 to the Engineers for the construction of tunnels on Corregidor. With this money, Maj. Lloyd E. Mielenz, the engineer in charge of fortification work at the harbor defenses, built two-thirds of a mile of concrete-lined tunnel. By stretching the Navy funds he was also able to provide Panama mounts (makeshift concrete mountings that permitted the trail of a field gun to be swung in a full circle), access roads for the big guns, and other minor improvements.5

War Plan ORANGE-3 linked Bataan Peninsula with the fortified islands in the defense of Manila Bay. Except for a few roads and trails, most of Bataan was virtually a wilderness. On 25 July 1940 Grunert, after outlining for the General Staff what he considered to be the “minimum requirements for an efficient defense” of the peninsula, requested $1,939,000 for roads, docks, and bomb-proof storage. Marshall replied that it was against War Department policy to put money into large projects of this nature.6 Grunert nevertheless persisted, and in fact broadened his request to include $346,000 for the harbor defenses. He made little progress until early 1941, by which time the War Department’s attitude had begun to change. In March of that year Congress appropriated $946,000 and in June $3,688,000 for work on Bataan and Corregidor. In November 1940 Major Mielenz had recommended that an inter-service board be appointed “without delay to formulate a workable plan for modernizing the Harbor Defense protection against heavy shelling and aerial bombing.” The commanding general of the Harbor Defenses appointed the board at once, and by early May 1941 it had prepared plans calling for underground protection, gas proofing, and air conditioning. This program was to cost $3,500,000 and take three years to complete. In June, Grunert submitted the plan to the War Department, but he received no money until early October.7

Airfields, according to General Grunert, were the most vital element in the defense of the islands.8 In 1940 and early 1941 there were but two Army airfields in the Philippines—Nichols, just south

of Manila, and Clark, about 50 miles northwest of the capital. Nichols had the distinction of being the only military field in the islands with a paved runway. But this runway, like the turf strips at Clark, was too small to take B-17’s safely. Indeed, there was not a paved runway in the entire Philippines that could accommodate a fully loaded B-17.9 In October 1940 Grunert began to plan a network of modern military airfields. He envisioned 6 major fields—4 on Luzon and 2 on Mindanao—and a score of smaller ones dispersed throughout the islands. By July 1941 the War Department had obtained $2,773,000 for Grunert’s projects.10 MacArthur, after his appointment as Commanding General, USAFFE, insisted on an even larger sum. By October a total of $4,187,130 had been allotted for airfields in the Philippines, and MacArthur was calling for $5 million more. The War Department immediately allotted him three of the five million, and it promised him the rest in the near future.11 Part of the construction was to be carried out by the Civil Aeronautics Authority and the Philippine Commonwealth, but the bulk was assigned to the Engineer Department.

By 30 November 1941, $4,654,350 had been turned over to Colonel Stickney for construction of airfields. To help protect not only the airfields but the islands themselves against attack, an air warning service was needed. During the latter part of 1941 Stickney received $265,000 to build ten warning stations and an underground information center.12

Construction Gets Under Way

By early 1941, the growing program threatened to overwhelm the engineer department. Stickney appealed to OCE for help. On 28 April he wrote to General Kingman that the department engineer’s office had until recently been “a sleepy inactive place with two ... American civilian employees, and was able to transact its business in a few hours each morning. It was similar to all other offices in this headquarters. There were no funds available for new work and all duties were routine.” Now the situation had changed completely, and Stickney lacked the wherewithal to carry out a high-speed construction program. With but one regular officer to assist him, he considered personnel to be his “most crying need.” The several reservists who had recently arrived from the United States were not acquainted with local conditions and required time “to take hold.” Few American civilians were available and only limited use could be made of Filipinos. Stickney nevertheless succeeded in finding enough Reserve officers and civilian engineers to

form a skeleton organization in his office and in the field.13

The department engineer was anxious to get construction under way before the start of the rainy season, which, on western Luzon, where most of the work was to be undertaken, lasted from June to November. Unless started before the onset of the rains, construction would be almost impossible at some locations. Meanwhile, there was heavy pressure from General Grunert to get things done which everyone now felt “should have been done years ago.14

Formidable difficulties stood in Stickney’s way. Among them were his remoteness from the United States and the necessity of having to deal with a semi-independent government. Contractors were scarce as were skilled labor, materials, and equipment. The engineer effort and an $11.5 million dollar building program under the department quartermaster’s direction severely taxed the resources of the islands.15 Some of Stickney’s most serious difficulties arose from having to follow procedures designed for normal peacetime conditions. He was determined to overcome these obstacles, proposing “to do what is necessary ... even though the regulations may be temporarily violated.”16

Construction was in some instances held up by the long time required to obtain title to land. Although large projects such as those at Clark and Nichols were to be built on land already owned by the government, sites for many of the smaller jobs had to be acquired. Without the power to condemn, the department quartermaster was forced into protracted negotiations with land owners. Not until 21 October 1941 did MacArthur and President Manuel L. Quezon agree upon a procedure for breaking this bottleneck. Where few property holders were involved, titles were clear, and the land could be acquired at reasonable cost, USAFFE would continue to obtain land by direct negotiation; otherwise, the Philippine Government would expropriate the land. The agreement speeded up real estate transactions.17

Stickney did not have to look far for construction firms as there were only three in the islands with the equipment and experience necessary for doing work on a large scale within a reasonable time—the Benguet Consolidated Mining Company, Marsman and Company (also a mining firm); and the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific Company of Manila. The last was the only concern capable of building docks and erecting steel hangars. The two mining companies were specialists at tunneling but were not well equipped to handle airfield construction, though they volunteered to do this type of work in order to aid the defense effort. For less complicated projects Stickney could rely on Filipino contractors, who

generally had small staffs and little equipment. He could also hire workmen and organize a work force of his own. No troops were available. The only U.S. Army engineer unit in the islands in early 1941 was the understrength 14th Engineers (Philippine Scouts), a combat regiment of the Philippine Division, already engaged in improving tactical roads and trails on Bataan. In this situation, Stickney had to make the best use of the construction and engineering talent at his disposal.18

One obstacle to speed was the traditionally slow method of awarding lump-sum contracts by advertising for competitive bids. With so few large construction firms in the islands and with their capabilities quite well known to the department engineer, competitive bidding would cause needless delay. Besides, the tunnels the engineers were to construct on the fortified islands and Bataan were of a highly secret nature, the details of which it was not advisable to make public through advertising. Accordingly, on 2 May Stickney radioed to Washington asking authority to negotiate contracts. Under Secretary of War Patterson on 19 May directed the department engineer to use cost-plus-a-fixed-fee agreements. After Stickney wired back that he did not need to make fixed-fee contracts but urgently required authority to negotiate lump-sum and unit-price contracts, Washington on 13 June gave him that authority. Even though he could now negotiate, there still remained the time-consuming tasks of making estimates, preparing plans, and arriving at terms of agreement.19

Construction got under way slowly. During April and May, Stickney managed to start 4 projects, including Bataan Field in the southeastern part of the peninsula, a bombproof shelter for general headquarters at Fort McKinley, just south of Manila, and a runway at Nichols Field. June marked the beginning of work on a depot at San Juan del Monte, just east of Manila, and on already existing Kindley Field on Corregidor. Within the next three months the engineers broke ground for 16 projects, among them a dock on Bataan, 2 air warning stations, and 3 new airfields—Del Monte and Malabang on Mindanao and O’Donnell on Luzon. By the end of September construction was in progress at 26 jobs estimated to cost $1,500,000.20

Colonel Stickney had barely started to build when the southwestern monsoons began. For the next five months construction crews battled mud and torrential rains. Maj. Wendell W. Fertig, assigned to Bataan early in the summer, later recounted: “[The] rainy season was in full swing and the forest was a morass. ... Thousands of cubic yards of rock had been placed as surfacing on the secondary roads, but under the pounding of 10-wheel ammunition trucks, all vestiges of hard surfacing disappeared in a

sea of mud. Two tractors were kept busy hauling these monstrous trucks out of mud holes.” Transferred to Clark Field in August, Fertig remarked that construction had become a “nightmare.”21 Conditions were so bad at Nichols Field that the Air Corps suspended operations there in July.22 The engineers continued work on the runways at Nichols but with “25 percent efficiency.” The weather had a hampering effect on construction throughout western Luzon.23

At the outset the department engineer had little construction machinery. An inventory of 28 December 1940 listed the following items of power-driven equipment: 6 bulldozers, 2 shovels, 2 rock crushers, an earth auger, and a grader. Little help could be expected from the Philippine Government, for, in order to keep down unemployment, the commonwealth used practically no equipment. Few contractors in the islands had machinery, and delivery from the United States would take months. Stickney proposed to rent and buy locally as much equipment as he could and to order from the United States, although shipments from America would arrive too late “to be of much benefit this working season.” The Chief of Engineers refused to let him rent but gave him permission to negotiate purchases in the local market, and promised to send equipment from the States along with the first shipment of troops.24 Stickney hastened to buy the

few items of new and used equipment held by local dealers. He begged a few pieces from the Philippine Department of Public Works and borrowed from American commanders. Brig. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., commanding Fort Stotsenburg, loaned two new 1½-ton trucks to the, O’Donnell project. “Without them,” wrote an Engineer officer, “it would have been impossible to begin construction ... [in an area] which could normally be reached only by horse-drawn units and then only during the dry season.” Notwithstanding cooperation of this sort, there was never enough machinery. Only by constant shifting of equipment from one location to another could Stickney keep all of his jobs moving.25

Efficient maintenance and repair of equipment were hard to come by. Most natives were unacquainted with machines, and the skilled mechanic was “nearly nonexistent.” Too often the Filipino was concerned primarily with the appearance of his equipment. Capt. Harry O. Fischer, area engineer at Clark Field, got hold of some tractors belonging to the commonwealth’s Bureau of Public Works, “which looked beautiful—freshly painted and shined.” “But, I found to my sorrow,” he wrote, “that Filipino maintenance went only skin deep—what they couldn’t see didn’t bother them. One D-8 [tractor] I got had had 7,000 operating hours and had

had nothing done to it. It sounded like a corn grinder.” There was, besides, virtually no local supply of spare parts. Almost all replacements had to be requisitioned from the United States and delivered over a 7,000-mile-long supply line. These were conditions the engineers could do little to correct.26

The islands produced many of the materials needed for construction, including lumber, slag, cement, lime, and aggregate. Local dealers stocked pumps and other common items of installed equipment. Access to these markets was at first restricted by regulations which forbade Stickney to purchase in amounts of more than $500 or to alter standard plans and specifications without consulting the Chief of Engineers. OCE lifted the first restriction in March and the second in May when Stickney made it known that shortages of steel would force him to build hangars of wood. Since time could not be spared for sending the new drawings back to the States for approval, General Schley gave Stickney authority to alter plans whenever necessary. The department engineer could now draw freely on the resources of the Philippines, but many of the supplies he most desperately needed still had to come from the United States. Though shipments of structural steel, steel siding, heavy cable, switchboards, and lighting equipment were anxiously awaited, months were to pass before any of these items would be received.27

Construction During the Latter Half of 1941

The arrival of U.S. Engineer units gave an impetus to the airfield construction program. First to come was the 809th Engineer Aviation Company, which, upon disembarking at Manila on 10 July, was assigned to Nichols Field. Well supplied with modern equipment, the 176 men of the 809th worked around the clock, operating their own machinery and serving as foremen of the 800 unskilled native laborers employed on the project. A second unit, the 803rd Engineer Aviation Battalion (less Company C), arrived from the United States on 23 October. Headquarters Company began extending the turf runways at Clark to transform this field into a huge base for B-17’s. Company A took over the project at O’Donnell, some twenty miles north of Clark, while Company B went to Del Carmen, near the base of Bataan Peninsula, where on 10 November it started construction of a complete airdrome estimated to cost $432,500. On 1 December the 809th became Company C of the 803rd. These engineer troops helped greatly to make key airfields operative at an early date.28

Construction gained added momentum after the arrival of Colonel Casey on 8

October. Having served in the. Philippines from 1937 to 1940 as assistant to General MacArthur, Casey was familiar with conditions in the islands. At the time of his appointment as Engineer, USAFFE, he was chief of the Design Section of the Construction Division, Office of The Quartermaster General. There he had worked under General Somervell and had had an opportunity to observe how construction could be pushed at high speed. Casey, losing no time in trying to find out where Stickney’s program stood, called for information on the status of major projects. On November Stickney submitted his first semi-monthly progress report, and from it Casey concluded that work would have to be greatly expedited. He urged Stickney to intensify pressure on contractors and suggested that certain jobs be switched from purchase and hire to contract. He induced the commonwealth’s Bureau of Public Works to undertake additional projects, and used all the influence he could muster to speed deliveries from the United States and to streamline procedures.29

Casey was especially concerned over the inadequate progress on the air warning stations. Reconnaissance parties led by Barney Clark, an American civil engineer who had spent many years in

the islands, had selected sites on Luzon and on nearby Mindoro and Lubang. Construction of two stations, one on Bataan and the other on the Bicol Peninsula, was begun in September, but at eight other locations nothing had as yet been done. Since many stations were in out-of-the-way places, the engineers had to build hard-surfaced access roads and strengthen many bridges before the detection units, each weighing over eight tons, could be hauled to the sites. On 15 November plans and specifications for eight of the stations were but 5 percent complete. Casey insisted that every effort be made to get these “high priority projects underway.” Of even greater concern to him was the underground chamber at Fort McKinley where the headquarters of the air warning service was to be located. This complicated tunneling job was not begun until 15 October. Casey suggested that Stickney bring pressure on the contractor, explaining that this tunnel was “a vital item of the entire Air Warning Service.”30

With the end of the southwestern monsoons, construction of airfields on western Luzon progressed rapidly. The soil of the Central Plains, composed largely of marine deposits, had admirable bearing qualities. Even without surfacing, the runways at Clark, O’Donnell, and Del Carmen could carry the heaviest aircraft then in use. Because the soil was porous, drainage was easily provided. As one engineer expressed it, Clark Field

had “vertical drainage.” Dust proved to be the major problem. The increasingly large numbers of planes arriving at Clark wore off the turf, with the result that such clouds of dust arose from the runways that the air was seldom clear unless a strong wind was blowing. At Del Carmen the dust was even thicker. There, as at Clark, the engineers had neither equipment nor material for hard surfacing. Nor did they have any calcium chloride, the chemical commonly used for dust control. Fertig, the area engineer at Del Carmen, recalling his tennis-playing days in Colorado, remembered that clay courts were often treated with water and beet sugar syrup to make them dust proof. He decided to experiment by applying to the runway a mixture of water and waste molasses from a nearby sugar refinery. War came before the experiment could be completed, but it was successfully carried out later on Bataan Field.31

Although plans for fields on the southern islands developed slowly, considerable work had been done by 15 November. Malabang, a small commercial airport on the southwest coast of Mindanao, was easily enlarged. Its runway, surfaced with fine volcanic cinders, was lengthened by the removal of a few coconut trees. Del Monte, located in the midst of the pineapple plantations of northern Mindanao, was originally nothing more than the fairway of a golf course. By removing a few rocks from a strip of land which extended out into the

Tagoloan River and by mowing the grass of a large neighboring meadow, natives quickly prepared two additional strips. Late in 1941 Del Monte was transformed into a second base for B-17’s. Zamboanga, the third large field, showed little progress. The War Department had insisted on the construction of a bomber base near the tip of Zamboanga Peninsula, where the only feasible site was in the rice paddies of that area. Local farmers would not give up their land willingly and the government resorted to expropriation. After the land was acquired on 3 November, the engineers drained the paddies, a task that consumed much valuable time. By mid-November runways at Malabang and Del Monte were in use, but construction at Zamboanga had not yet started.32

Meanwhile, work was under way on Corregidor, where Mielenz encountered difficulties similar to Stickney’s. His chief problem was to find contractors for the big modernization program; begun late, negotiations dragged on throughout the fall. Mielenz did manage to begin a number of smaller projects in the summer of 1941. At the height of the rainy season, convicts from Bilibid Prison in Manila laid four-and-one-half miles of cable six feet underground for the controlled

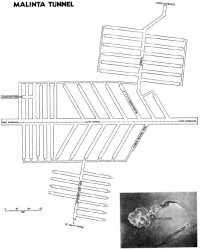

mine system. In July a construction crew began blasting additional space for the hospital in the great tunnel under Malinta Hill and enlarging five laterals to be used for storage. Other projects included construction of a bombproof command post, strengthening beach defenses, and sandbagging.33

General MacArthur found the progress of construction encouraging, and there was much to support his view. In October Stickney launched projects estimated to cost one-third of a million dollars at Nichols, Clark, and Fort McKinley. The following month he added nine jobs to the list of going projects; included were warehouses and docks on Bataan, an air warning station on Lubang Island, additional facilities at Clark, Bataan, Cabanatuan, and Nielson Fields, and the two new airbases, Del Carmen and Zamboanga. By late November Stickney had a program of $3,600,000 under way. Meanwhile, the Corps of Engineers of the Philippine Army was improving numerous military fields on Luzon, among them Tuguegarao, Aparri, and Legaspi; the Civil Aeronautics Authority was readying commercial fields for military use; and the Bureau of Aeronautics of the Philippine Government was building a considerable number of emergency landing strips throughout the islands. All told, about forty fields, ranging from large installations such as Clark and Nichols to mere strips for emergency landings, were being developed for military aircraft.34

Combat Engineers

Concurrently with the construction program, the Engineers prepared for combat. For many years successive department engineers had been at work on defense plans under War Plan ORANGE. Upon mobilization, the department engineer’s organization was to be expanded rapidly by the addition of reservists and civilians. Labor companies of Filipinos were to be formed, and full use was to be made of the employees of the commonwealth’s Bureau of Public Works. Should the enemy invade Luzon, demolitions were to retard his advance, and the engineers planned to put up road-blocks, mine highways, and destroy bridges. Especially marked for destruction were roads on the sides of precipitous mountains and long bridges over deep gorges and unfordable streams. In the department engineer’s office was a “demolition book” containing sketches of every bridge of any importance on Luzon, together with wiring diagrams and computations of the charges required for destruction. Some 400,000 pounds of TNT or the equivalent would be needed. If supplies of TNT were low, the engineers planned to draw on the stocks of dynamite held by mining companies, although dynamite was not as effective

Malinta Tunnel

for hasty demolitions. Mining engineers would be called upon to help destroy roads and bridges. Colonel Casey began to formulate a plan in line with MacArthur’s new strategy of defending the whole archipelago, but war prevented its completion.35

The one U.S. engineer combat unit in the islands, the 14th Engineers (Philippine Scouts), a part of the Philippine Division and commanded by Lt. Col. Harry A. Skerry, consisted in mid-1940 of 322 officers and men. While most of the officers were Americans, the enlisted men were Filipinos. When not training or on maneuvers, the 14th built military roads and bridges and cut trails through the jungles of Bataan. In January 1941, when the Scouts were authorized an increase from 6,500 to 12,000, the 14th was ordered to add 544 men to its roster. By late November the regiment had been expanded to include 938 officers and men. Most of the recruits came from the Baguio gold mining area and were old hands at construction.36

The mobilization of the Philippine Army, begun in September 1941, was expected to provide the great majority of the engineer units urgently needed by MacArthur. Shortly after Casey arrived, MacArthur ordered him to develop a force “equipped and trained to meet the heavy demands now required of the Engineers in modern warfare.” Each of the 12 Philippine Army divisions was to include an engineer combat battalion of 500 officers and men. Also to be organized were 3 engineer combat regiments, 6 separate battalions, 2 heavy ponton battalions, 3 topographic companies, and enough additional units to provide a complete engineer component for a Philippine Army of 160,000 men to be fully mobilized by October 1942. To accomplish this program would be no easy task. Casey had no engineer officer to assist him until 20 November, when Capt. Emilio Viardo of the Philippine Army was assigned. Occasionally officers and men from other arms and services helped out. Casey would have to try to build the force from a cadre with but limited training. Most Filipino officers did not have the necessary background to command technical units, and few American officers could be expected. The bulk of supplies and equipment would have to come from the United States.37

Engineer combat battalions of the Philippine Army mobilized with disappointing slowness. As late as December 1941 not a single battalion was completely manned and equipped, with actual strength closer to 400 men than to the authorized 500. Equipment consisted chiefly of hand tools, and there were not enough of these to go around. The Philippine Army as a whole was no better prepared than its engineers, a state of affairs that did not augur well for the future.38

To make matters worse, MacArthur’s

order to reduce the four regiments of the Philippine Division to three, in accordance with the War Department policy of converting square divisions to triangular, decreased the number of U.S. engineers. The conversion of the Philippine Division in early December reduced the 14th Engineers to a battalion. Despite protests by Casey, Stickney, and Skerry, several hundred officers and men of the regiment were transferred to other arms and services. Fortunately, the 14th was allowed to keep its equipment, which it later put to good use.39

By early December U.S. Army engineer troops in the Philippines numbered approximately 1,500, the combined strength of the 14th and 803rd Battalions. These units made up less than 5 percent of the total U.S. force. Estimates of the engineer strength of the Philippine Army are difficult to arrive at, because that army was never fully mobilized. When war broke out, the engineer component of the Philippine Army amounted to roughly 5 percent of the total, far below the 20 percent generally considered by engineer officers to be the ideal proportion. In the large force which MacArthur and Casey planned, development of engineer units was to receive high priority and the ratio of engineer troops was to approach the optimum.40

Supply

The task of providing engineer supplies and equipment for the growing U.S.-Filipino forces fell to Maj. Roscoe Bonham, Stickney’s supply officer. In January 1941 the Supply Division, in addition to Major Bonham, consisted of one enlisted man and two native clerks. The Philippine Engineer Depot, which Bonham also commanded, was run by half a dozen enlisted men and roughly 25 native employees. A vigorous program of recruitment produced good results. By December the Supply Division included 5 officers, 4 enlisted men, and 31 American and Filipino civilians; the depot was staffed by 3 officers, 18 enlisted men, and 90 civilians. Located in the Manila port area, the depot had been adequate in the past but was too small to hold the enormous quantities now required. Bonham succeeded in increasing facilities during the summer and fall by constructing a shop and several warehouses and sheds along the Pasig River. But despite his extraordinary efforts, he never succeeded in getting enough people or providing sufficient space.41

Bonham found it even more difficult to assemble stocks of engineer items than to find employees and build warehouses. He scoured the islands for steel, wire, hand tools, camouflage materials, explosives, and machinery. Importers, local

merchants, manufacturers, and mining companies all contributed to Bonham’s stores. No likely source escaped his attention. Learning that the Cadwallader-Gibson Lumber Company was to be liquidated, he quickly bought up its stock of one and a quarter million feet of lumber, paying 40 percent less than the current market price. Devising an “unorthodox plan” whereby he himself guaranteed payment, Bonham was able to import from India enough burlap to make more than half a million sandbags. Ingenuity notwithstanding, scientific instruments, mechanical equipment, and other special engineer items could not be procured in the Orient. These would have to come from the United States.42

Colonel Stickney asked the Chief of Engineers to send searchlights, bridging, and water purification units in addition to construction equipment for the troops. He also appealed for spare parts. General Schley promised to fill the requisitions as quickly as possible. Meanwhile, Bonham ordered equipment from American manufacturers through the Pacific Commercial Company of Manila. The U.S. defense program and lend-lease requirements took precedence over the needs of the Philippines, however, and consignments to the islands had a low priority. By 19 September Bonham had accumulated sufficient stocks of earth augurs, assault boats, and gas shovels to equip the U.S. troops at initial war strength. Nevertheless, his inventories showed great shortages of such basic items as explosives, searchlights, ponton bridges, water purification units, tractors, trailers, and gas-motored timber saws. Not until autumn did the War Department take decisive action to speed deliveries to the islands.43

Early in September MacArthur expressed dissatisfaction with the low priority assigned to the Philippines. Unless his orders for supplies and equipment were filled more promptly, he would be unable to put the Army on a war footing as rapidly as he considered necessary. Marshall, fully aware of the difficulties that faced MacArthur, agreed to give the Philippines highest priority. The engineers in the islands could now hope to get the troops, supplies, and equipment they so sorely needed. By mid-November a general service regiment—the 47th—was being readied for movement overseas, and equipment for two aviation battalions was en route. OCE was making an all-out effort to speed reinforcements. Encouraged by the Chief’s attempts to aid them, Casey, Stickney, and Mielenz sent back a huge requisition. They asked for 2 ,000 tons of construction materials and equipment costing $5 million dollars, but this request did not reach the Chief of Engineers until after Pearl Harbor.44

Construction Progress

By the first week of December construction was progressing satisfactorily, but the program was far short of accomplishment. Farthest advanced were Clark and Nichols. Yet several runways at these fields were still building. Bataan Field was 68 percent complete; Del Monte had one usable runway, and the construction of housing was just beginning; and 70 percent of the work on Malabang’s runway had been done. The remaining fields were far behind these. Other types of projects were also lagging. The Mariveles dock and the Limay wharf were nearing completion, but the important tunnels on Bataan had not yet been started. Progress on the air warning stations was slow; only two were operating—one at Nielson, the other at Iba. Contracts for the first items in the new program to modernize fortifications on Corregidor were still in process of negotiation. The engineers had succeeded in getting most of their projects under way, but much of the work of construction remained to be done.45

To some the prospect was not encouraging. Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, commanding the Far East Air Force (FEAF), pronounced the progress of airfield construction “disappointing.” He observed that work was proceeding more or less on a peacetime basis. It was difficult to change the age-old customs of the tropics. “The idea of an imminent war seemed far removed from the minds of most,” wrote Brereton in his diary under the date of 9 November.46 On the eve of the Japanese attack, Col. Francis M. Brady of FEAF described the outlook as “quite discouraging.” In a personal letter to Brig. Gen. Carl Spaatz, he stated: “Construction of airdromes is lagging due to lack of engineer personnel and inability to secure competent civilian assistance from among the Filipinos or local contractors. The dearth of equipment is also a serious factor.”47 The engineers were no better satisfied but offered no apologies. Considering the handicaps under which they labored, they felt their showing was a creditable one.

Except those high-ranking officers who had been informed of the breakdown of negotiations between the United States and Japan, few were aware of the seriousness of the situation and the imminence of war. A peaceful atmosphere still pervaded the islands. How remote war seemed is suggested by Col. Wendell W. Fertig’s description of an excursion on the last day of peace:–

Sunday, December 7th, dawned a perfect day for a picnic at Lake Taal. The four officers from our mess had already made arrangements for an old-fashioned steak fry. ... loading the outboard motor we set out for the lake. ... [The] entire day

was spent in lazy fishing and in enjoyment of the huge steaks prepared over a driftwood fire. The brilliant sunset illuminated the lake and we started home across the reddened waters.

The picnickers were awakened at 4:30 the next morning to the news that the Japanese had attacked Hawaii. “We stood by ... awaiting the inevitable blow. ... ,” wrote Fertig. “We could only hope that, in matching our puny weapons against the aggressor, somehow help would reach us before too late.”48

Withdrawal to Bataan and Corregidor

War came to the Philippines with overwhelming suddenness. On the morning of 8 December enemy planes appeared over the islands to bomb strategic targets. About noon Japanese bombers carried out devastating attacks on Iba and Clark Fields. So effective were these and succeeding raids on airfields that within a few days the striking power of the Far East Air Force was almost completely destroyed. On 10 December Japanese troops landed at Vigan on the northwestern coast of Luzon and near Aparri on the northern coast. Two days later a third force came ashore at Legaspi near the southeastern tip of the island. From these three points enemy troops began moving inland—their major objective, the nearby airfields. In the Visayan Islands and on Mindanao no landings of decisive or even critical importance were made until fairly late in the campaign.49 The story of the defense of the Philippines is thus almost entirely one of fighting on Luzon. It was here that the engineers had to make their greatest effort.

The engineers urgently required a large increase in troop strength, but because of Japan’s naval superiority, no more units could be expected from the United States, at least not in the near future. All that could be done to increase the number of men in the field was to speed mobilization of the combat battalions of the Philippine Army. Most retired and Reserve officers had already been ordered to active duty and the remaining few were called up immediately.50 Casey appealed to civilian engineers to serve with the Army. Many volunteered, with some being commissioned at once and others serving as civilians.51 American mining engineers, who came to be known as “Casey’s dynamiters,” were to be of inestimable value.52 “These men,” Casey wrote, “although they in general knew little of the military, were ideally qualified to perform all phases of engineer operations. They were of a pioneer type accustomed to doing crude engineer[ing] under great difficulties ... and capable of improvising and getting the work done.”53 Since the number of mining engineers was small, each man knew

most of the others either personally or by reputation. This simplified recruiting. Many of the mining engineers, moreover, brought with them their crews of loyal Filipino workmen.54

When war began, two Army ground forces were mobilizing on Luzon. North Luzon Force (NLF), commanded by Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, was responsible for the defense of the part of the island north of Manila. The part south and east of the capital was to be defended by South Luzon Force (SLF), commanded by Brig. Gen. George M. Parker, Jr. A third force, USAFFE Reserve, under the immediate command of General MacArthur, was to hold Manila and the area immediately to the north along the shore of Manila Bay. In USAFFE Reserve were the 14th engineers. The 803rd, under Stickney’s direction, was kept hard at work repairing bomb damage at Clark and Nichols and rushing Del Carmen and O’Donnell to completion. Each of the divisions in the North and South Luzon Forces had its engineer combat battalion. The first engineer units to see combat were the battalions with Wainwright’s North Luzon Force.55

Engineers With North Luzon Force

On 4 December, Colonel Skerry had turned the command on the 14th engineers over to Capt. Frederick G. Saint and left to take up his new duties as Engineer, North Luzon Force. When, on the following day, he reported to Wainwright’s headquarters at Fort Stotsenburg, he found he was the only engineer on the scene. On 7 December three enlisted men were loaned to him, and he was told he could expect an officer within a few weeks. Four divisional combat battalions were mobilizing, the th, 21st, 31st, and 71st. The 91st, also mobilizing, was attached to NLF but was not to be assigned until a week later. There were no force engineer units for work in rear areas; neither was there any equipment. For work behind the front lines Skerry was expected to make use of the divisional combat battalions, insofar as possible. In accordance with plans of long standing, he could also employ the district engineers of the commonwealth’s Bureau of Public Works.56

The engineers of NLF were to operate in an area some 275 miles long and 00 miles wide. In the north it was mountainous. On the west was a narrow coastal plain and in the east the mountains extended directly to the sea. The only passageway south through the northern ranges was the narrow Cagayan River valley. Southeast of Lingayen Gulf was an extensive level area, the Central Plains. About 40 miles wide and stretching 00 miles from the Gulf to Manila, the plains provided a natural avenue of approach to the Philippine capital. Northern Luzon had three principal rivers, the Cagayan flowing

northward through the mountains, the Agno following a westerly course and emptying into Lingayan Gulf, and the Pampanga cutting southwestward across the Central Plains to Manila Bay. Except in their upper reaches and in a few other places, these rivers were unfordable. Northern Luzon boasted a fairly good road net. Along the west coast from Lingayen Gulf to Bataan was a graveled highway capable of taking heavy military traffic during the dry season. An all-weather road, Highway 5, ran from Aparri through the Cagayan Valley and across the Central Plains to Manila. Another all-weather road, Highway 3, extended down the northwest coast to Lingayen Gulf and thence across the Central Plains to the capital. Northern Luzon was also served by the main line of the narrow-gauge Manila Railroad, which ran from Manila to San Fernando, La Union, on the coast north of Lingayen Gulf.57

On the day the Japanese landed at Vigan and Aparri, Casey ordered the destruction of roads, bridges, and ferries in the Cagayan Valley and the mountainous regions of northern Luzon. Skerry called upon the engineers of the Bureau of Public Works to do this job. No TNT was available, nor were there any tetryl caps or electrical cap exploders, but mining companies of the Baguio region had ample stocks of dynamite, and Skerry asked three of the largest to send him 180 tons. Within a few days shipments began to arrive. Lacking the

most powerful explosive and the best types of detonators, Skerry prescribed exceptionally large charges of dynamite and ordered the use of time fuses. One expert described this method as “plainly a matter of loading heavy charges of dynamite, sandbagging or tamping them as much as possible, and ... pray[ing] for a complete job of demolition.” Steel bridges with concrete floors proved especially difficult to destroy. In the confusion of the times, no use was made of the demolition book, so carefully prepared over the years. It remained in Stickney’s office in Manila, to be destroyed shortly before the capital was evacuated. By 9 December, the engineers had completed their demolitions in north central Luzon and had sealed off the region with roadblocks. The enemy advance southward from Aparri to the Central Plains would be difficult.58

A greater menace was the Japanese thrust along the coastal road southward from Vigan. On learning of the enemy landing, Casey had issued orders for large-scale demolitions between Vigan and San Fernando. Since no engineer units were available, he asked the Bureau of Public Works to take this assignment. By 1 6 December enemy troops had penetrated as far south as Tagudin, about twenty-five miles above San Fernando. That same day USAFFE received word that its orders for demolitions were not being carried out. Casey telephoned

Skerry at once, ordering him to blow the bridges to the north of San Fernando. The next morning Skerry made a hurried reconnaissance of advance positions and found that bridges south of Tagudin had already been destroyed. He saw, however, that the situation called for more engineers. On the afternoon of the 17th he visited the local district engineer to urge greater speed in the preparation of demolitions around San Fernando and the following day persuaded the manager of a nearby mine to lend him twelve foremen. Meanwhile, on orders from USAFFE, Skerry’s engineers destroyed the large concrete pier, the telephone exchange, and the oil and gasoline tanks at San Fernando. Although demolitions did not appreciably retard the Japanese advancing down the coast, they entered the city to find little of military value remaining.59

A major enemy landing at Lingayen Gulf appeared imminent. On 18 December Wainwright ordered Skerry to prepare for demolition the roads and bridges from Lingayen Gulf to as far south as the towns of Tarlac and Cabanatuan—an area about forty miles wide and sixty miles deep. Holding up enemy forces by demolitions on the Central Plains would be much more difficult than delaying them in the mountainous regions of the north. In the upper Central Plains, there were only two rivers that would be serious obstacles to an invader equipped for modern war—the Agno and the Tarlac. During the dry season even these were fordable at certain points. Because the land was flat, there were few good sites for roadblocks. Tanks could easily traverse the dry rice paddies of the almost treeless Central Plains.60

Given this terrain, Skerry prepared a plan of defense in depth, making use of the only important obstacles in the entire region—the natural barriers of the rivers. Under his direction, the engineers of the Philippine Army and employees of the Bureau of Public Works set out to prepare all major highway bridges from the Agno to Tarlac and Cabanatuan for instant demolition. Casey furnished groups of miners under the command of Lt. Col. Narciso L. Manzano (Philippine Scouts) to help with this work. Colonel Manzano and his miners were temporarily attached to North Luzon Force. Casey’s office also sent a special detail—a second lieutenant and three miners—to NLF to help Skerry prepare the large railroad bridges for destruction. Small spans and culverts in the area were to be taken care of by the rearmost divisions if and when Wainwright’s force withdrew through the Central Plains.61

A serious weakness in the defense was the lack of antitank mines. On 18 December Casey asked the USAFFE ordnance officer to order 70,000 from the United States. Meanwhile, Bonham, using designs supplied by Casey, furnished makeshift mines. Consisting of a wooden box about ten inches on a side, with approximately five pounds of dynamite,

a flashlight battery, and a detonator, each mine was put together and placed by the troops. Bonham could not supply enough materials to mine extensive areas. The most the engineers could hope for was that an enemy tank would occasionally blunder into a mine field. Skerry’s success in delaying the enemy would have to depend mainly on the destruction of bridges.62

Fears of a landing at Lingayen Gulf proved well founded. On 22 December a large Japanese force came ashore between Bauang and Damortis. The enemy troops were too numerous to be beaten back by the few NLF units near the gulf, and reinforcements were not available. Hopes of defeating the enemy at the beaches vanished. On the night of 23 December, General MacArthur declared War Plan ORANGE-3 in effect. Wainwright would withdraw southward and attempt to hold back Japanese forces coming down from the gulf long enough to enable South Luzon Force to fall back through Manila, cross the Pampanga, and continue on to Bataan. NLF was to carry out its withdrawal in five phases, designated D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5. Making his first stand midway between Lingayen Gulf and the Agno, Wainwright would retire to four successive positions, the last of which, D5, stretched from the town of Bamban on the west to Sibul Springs at the foot of the mountains on the east. This was the critical line. It had to be held until South Luzon Force was safely across the Pampanga.63

Because there were few planes left to interfere with the enemy’s progress and because the untrained Philippine troops could not withstand the powerful Japanese onslaughts, Wainwright had to rely heavily on his engineers. It was they who had to keep open roads and bridges ahead of the retreating columns—not an easy task in view of the Japanese supremacy in the air. It was the engineers, too, who had to prepare all bridges for demolition and assure their destruction after friendly troops had passed over.

Four of Wainwright’s five engineer combat battalions participated in the withdrawal—the 11th, 21st, 71st, and 91st. The 31st had gone with its division to help guard the western coast just above Bataan and on 14 December had been removed from NLF control. Wainwright decided to keep the 11th, 21st, and 71st Battalions with their divisions until they reached San Fernando, Pampanga. Then each battalion, less one company, was to be detached to maintain the roads leading into Bataan.

By Christmas Eve, Wainwright’s forces were retreating toward the D2 position, located along the southern bank of the Agno. The engineers had been at work here for more than a week. Anticipating bottlenecks when the heavy traffic from the north reached the bridges at Bayambang and Carmen, Skerry had put men from the Bureau of Public Works to work building two bridges of palm

logs at Wawa and Urbiztondo. Charges had been placed on all the bridges over the Agno. When the Japanese bombed the big highway bridge at Carmen on 23 December, some of the charges exploded, dropping the southernmost span to the river bed. Wainwright, alarmed because most of his tanks were still north of the river, ordered immediate repair. The 91st engineers, under constant enemy air attack, built a temporary span within 24 hours.64 After the last of the American and Philippine troops had crossed the river, the engineers demolished all the bridges along the 50-mile front. Wainwright’s forces had reached the south bank of the Agno and temporary safety.65

During most of the ensuing withdrawal, the front-line engineer battalions were kept intact. They moved in a definite pattern: on completing an assignment in a given area, a unit leap-frogged over the one behind it and continued working farther to the rear. These battalions, with other covering forces, prepared and executed demolitions and put in roadblocks near the front. To the rear, all important demolitions, whether of bridges and roads or of equipment and supplies, were carried out by engineers under Skerry’s command. Much of this work was done by the 9 1st Engineers. On 21 December the entire battalion was placed under Skerry, and, except for one company which later returned to its division, remained with him throughout the withdrawal. Still farther to the rear, other engineers readied roads and bridges for destruction. When War Plan ORANGE-3 went into effect, Wainwright ordered Skerry to prepare demolitions and erect obstacles in the territory south of Tarlac and Cabanatuan. In the large new area, stretching southeast toward Manila and southward to Bataan, mining engineers and district engineers of the Bureau of Public Works again rendered valuable service.66

As NLF withdrew farther south, the engineers made ready to blow up every bridge in the path of the Japanese. Skerry personally directed the placing of the charges at the critical highway bridges across the Tarlac and the Bamban Rivers and over the Pampanga at Cabanatuan, Arayat, and Candaba. The special detail of miners, with the aid of troops, prepared the spans on the Manila Railroad, taking special care with the great bridge at Bamban. At all the large bridges on the highways and the railroad the engineers managed to place their charges well ahead of time.67

Groups of miners, getting the innumerable smaller spans ready for destruction, had to work rapidly, for they had much to do and time was short. W. L. McCandlish, a demolitions expert who had arrived in the islands shortly before the outbreak of war, worked with a small group under Manzano which operated north of San Fernando, Pampanga. McCandlish’s

description of the group’s activities furnishes an example of how such parties operated. While fighting was going on at Tarlac, about twenty-five miles to the north, McCandlish and his men prepared the bridge at Angeles. After placing the charges, the blasting cap, and six feet of fuse, they arranged to have three Scouts stationed at the south end of the bridge to guard against premature detonation, and then moved southward. Between Angeles and Mexico, they found only small timber structures. They drenched these with fuel oil and directed the troops stationed as guards to ignite them when the order was issued by the proper divisional staff officer. At Mexico, McCandlish and his miners found a 30-foot concrete bridge over a deep gorge. At both sides of the north and south abutments they dug pits six feet deep, and in each of the four holes they placed 150 pounds of dynamite, attaching a cap and a fuse three feet long. They then instructed the detachment at the bridge how to fire the charges, cautioning the men that it would take only two minutes for the fuses to burn through to the blasting caps.68

Inexperienced Filipino engineers left to blow up bridges found it difficult to determine when to set the charges off. They frequently could not ascertain whether all friendly forces had crossed, for the Philippine infantrymen very often did not arrive at the right place at the right time. Sometimes the engineers could not find the divisional staff officer who was to notify them when to

light the fuses. An engineer would then have to take upon himself the responsibility of destroying the bridge. Sometimes officers, with but incomplete knowledge of the tactical situation, ordered demolitions too soon. Occasionally, Filipino engineers grew panicky and set the charges off without waiting for any orders at all. The foot soldier who found himself stranded on the wrong side of a wrecked span might somehow manage to get across and rejoin his outfit, but to the tanker, a prematurely blown bridge could spell disaster.. Since tanks operated under USAFFE control, the engineers made special efforts to get information on their movements but were not always successful. One tank commander, Col. Ernest B. Miller, concluded that he would have to place his own men at each bridge over which his tanks must pass, “with orders to shoot anyone who attempted to blow it without our authority.” On at least one occasion Miller’s tankers had to rebuild a bridge before they could move south. Colonel Skerry pointed out that demolition at the proper time was his greatest problem by far. As a rule, the engineers tried to keep a bridge intact until strong enemy action on the far bank made destruction imperative, but the fact remained that some bridges were blown too soon.69

In these tense days the engineers were called upon not only to destroy but also

Colonel Fertig (photograph taken in 1953)

to build. On 18 December MacArthur directed Stickney to prepare temporary landing fields for the “large reinforcements of airplanes” expected from the United States. These fields were first to be developed for pursuit craft and later to be enlarged for bombers. Every likely site was to be turned to use. Ordered to move to Bataan, the companies of the 803rd Aviation Battalion built a number of fields while on their way to their new location. On 21 December, Company A left O’Donnell for Dinalupihan, near the base of Bataan Peninsula, where it put in three emergency strips in as many days and then began work on revetments. On Christmas Day, headquarters company left Clark to loin Company A. Four days later, both moved south to Orani to build another strip there. Company B, meanwhile, having finished one runway at Del Carmen, moved on to construct two bomber strips at Hermosa and Pilar on Bataan’s eastern coast. Company C left Nichols and went to the tip of Bataan to push work on Bataan and Cabcaben fields. Filipino civilians helped greatly in the preparation of these fields. Under the direction of Colonel Fertig, who in October had been appointed chief of Stickney’s Construction Division, thousands worked to improve existing runways and rough out additional fighter strips. The engineers provided the fields, but there were few planes to use them. Most of the newly constructed strips were soon to be overrun by the enemy.70

The situation confronting Wainwright grew progressively more serious. Six days after their landing at Lingayen Gulf, the Japanese reached the D4 line, and on the night of 30 December Wainwright ordered a withdrawal to the D5 position. That the retreat from Lingayen Gulf had been a planned and orderly withdrawal was owing in no small measure to the demolitions of the engineers.71 With Wainwright’s men now making a determined effort to hold, much depended upon the speed with which the troops of South Luzon Force

could clear the bridges over the Pampanga at Calumpit on their way to Bataan.72

Engineers With South Luzon Force

When war broke out, South Luzon Force was mobilizing in the mountainous country below Manila. An engineer organization had barely begun to take form. Arriving at headquarters at Fort McKinley on 8 December, Capt. William C. Chenoweth, the engineer, SLF, found he had a staff consisting of two enlisted men from the 14th Engineers. Force engineers were entirely lacking, nor were any divisional engineers available for work behind the front lines; the only battalions in SLF, the 41st and 51st, could not be spared by their divisions. Chenoweth quickly mobilized the employees of the Bureau of Public Works. Within a few days after the first enemy landings on Luzon, he had 2,000 men at work stockpiling materials to be used in repairing roads and rebuilding bomb-damaged bridges.73

With the landing at Legaspi on 12 December, much of southern Luzon was in danger of being overrun by the enemy. About 250 miles southeast of Manila, Legaspi was connected with the capital by a good highway and the main line of the Manila Railroad. The only obstacles in the way of the advancing Japanese were the numerous ravines, gorges, and isthmuses of the long and narrow Bicol Peninsula. Because of its length and the small number of troops at his disposal, MacArthur had decided not to defend the peninsula. He relied chiefly upon the engineers to impede the enemy’s advance toward the capital.74

Upon learning of the landing, General Parker ordered an engineer detachment to the peninsula, and a group from the 5 st Engineer Battalion, under the command of 2nd Lt. Robert C. Silhavy, left at once to destroy highway and railroad bridges. The Japanese rushed small motorized units forward in an attempt to head off demolition parties. On 17 December, while placing charges on the railroad bridge near Ragay, 75 miles northwest of Legaspi, Silhavy and his men were fired on by a Japanese patrol. The engineers returned the fire and proceeded with their work. After demolishing the bridge, they took up positions on the near bank of the gorge and soon thereafter the Japanese retired. This was the first encounter with enemy ground forces on southern Luzon. Silhavy and his men continued demolition work on the peninsula until ordered to move to Bataan.75

On 14 December Casey directed the district engineers to destroy the bridges and “critical road cuts and fills” on the main highway running along the length of the peninsula. Their work in wrecking many highway bridges and roads greatly hampered the enemy’s progress

toward Manila. Casey, meanwhile, instructed the Manila Railroad to prepare to dynamite its principal bridges. The president of the railroad, Mr. Jose Paez, on 16 December told Casey that he had ordered all rolling stock and materials moved toward the capital. His crews had already pulled spikes out of thirty kilometers of track. Stocks of gasoline and oil which could not be hauled northward were being burned or dumped into the sea. He agreed to destroy all bridges and promised to give special attention to the destruction of spans over deep gorges. These pledges were in large part fulfilled. By the 17th the piers of the bridges at Libmanan and Banga Caves had been partly wrecked, the trusses dropped about three feet, and the ties and rails thrown into the river. The destruction of the 150-foot center span of the bridge across the gorge at Del Gallego effectively ended all rail traffic between Legaspi and Manila for months to come.76

Lack of coordination between the Manila Railroad and South Luzon Force increased the difficulties of evacuating supplies. Around 14 December, before any trains could be moved out of the peninsula, the bridges at Malicbuy and Pagbilao, both west of the Bicol Peninsula, were blown on orders of a tactical commander of South Luzon Force. Casey ordered the bridges rebuilt at once. Since they had not been seriously damaged, reconstruction was completed in thirty-six hours. On the 16th a wreck southeast of Manila damaged three cars and tore up a section of track. Casey attributed the accident to “interference by the local military authorities with railroad operation.” Seeking an end to mishaps of this sort, he arranged a meeting between officials of the railroad and officers of SLF. Better timing in the destruction of vital bridges and improved scheduling of trains resulted.77

With but few mining engineers in his part of the island, Chenoweth had to rely heavily on men from the Bureau of Public Works. McCandlish, who made several inspection trips in southern Luzon, reported that in many instances demolitions were not expertly handled. On the eastern Luzon coast, for example, he happened upon a district engineer and a group of Filipino workmen who were preparing to destroy a section of road near the mouth of the Tignuan River. The road ran along the side of a steep cliff about 500 feet above the river. The men were digging holes two feet deep in the road and loading each of them with two cartridges of dynamite. McCandlish considered these measures entirely inadequate. A tunnel with crosscuts blasted out of the cliff and loaded with three or four tons of dynamite “would have taken out the road, brought down the cliff, and stopped all transportation for a considerable period.” With little experience in complicated demolitions work, and lacking the time for adequate planning and preparation, district engineers nevertheless carried out hundreds of small jobs successfully.78

A Japanese landing on 24 December at Atimonan, at the base of the Bicol Peninsula, threatened to cut off all troops to the east. The day before, MacArthur had decided to withdraw to Bataan. The rapid movement of SLF northward was doubly urgent. The only troops east of Atimonan by the 24th were two reinforced infantry companies and several detachments of the 5 1st Engineers. These were recalled at once. On 28 December, MacArthur informed SLF of Wainwright’s precarious position and urged greater speed in the movement to Bataan. He directed SLF to cross the vital Calumpit bridges not later than 0600 of New Year’s Day.79

As SLF withdrew across southern Luzon, the engineers destroyed highway and railroad bridges. They dynamited steel and stone structures and soaked wooden spans with fuel oil and burned them. Rolling stock, food, automobiles, trucks, and gasoline were evacuated or destroyed. Brig. Gen. Albert M. Jones, in command of SLF during its withdrawal to Bataan, stated that demolitions in southern Luzon were so effective that if so ordered his troops could have held back the enemy for a much longer time.80

Last Days of the Withdrawal

With both SLF and NLF troops converging on Calumpit, much depended on the effectiveness of demolitions in the

vital area between the D5 line and Manila. Many small groups were at work here. One party of fifteen miners with Colonel Manzano helped clear fields of fire and erect barbed wire entanglements along the D5 line. Thousands of civilians, recruited by the mayor of San Fernando and the district engineer, aided in this work. After helping to strengthen Wainwright’s positions, Manzano and his men moved southward to the region between the Pampanga River and Manila to prepare bridges for demolition. Engineers from Stickney’s office placed charges along roads and railroads leading to the capital. Colonel Casey organized several parties who were to destroy important installations in and near Manila.81

Of all the bridges being prepared for destruction, those at Calumpit were to furnish the most exacting test of the engineers’ skill in demolitions. The Pampanga, 500 feet wide and 16 feet deep at this point, was spanned by two bridges, one carrying Highway 3, and the other the main line of the Manila Railroad. Charges for blasting the great steel and concrete spans had to be figured and laid with exceeding care. Because SLF and some units of NLF were still east of the river, the greatest precaution had to be taken not only against premature blowing but also to insure setting off the charges at precisely the right time.82 The story of the engineers’ work at Calumpit is one of the most dramatic of the Philippine campaign.

On 27 December McCandlish, together

with other experts from Casey’s office and a company of soldiers, began preliminary tasks. They first turned their attention to the highway bridge, breaking holes through the concrete deck directly over the piers. Blowing the north abutment would be easy, since at its base was a recess three feet deep in which a half ton of dynamite could be loaded and tamped with sandbags and boulders. While one group of soldiers packed charges in the holes on the highway bridge, another placed explosives under the railroad bridge. Japanese planes dropped several bombs, but apparently made no determined efforts to destroy the bridges. Still, even near misses were dangerous to the heavily loaded structures. During one raid, a bomb hit a sugar warehouse near the south end of the highway bridge; another landed in the river only fifty yards downstream. At first, air raid warnings delayed the work, but as the men gained confidence, they continued to pack dynamite and fill sandbags, heedless of the wailing sirens.83

When Skerry inspected the bridges on 30 December, he found that heavier charges would be required at the lower panel points to insure complete destruction. The highway bridge needed additional dynamite on its concrete deck. Intending. to take no chances, he prescribed an extra ton for each of the two structures and ordered an alternate system of firing for the deck charges on the highway bridge. Inspecting the bridges again on the morning of the 31st, he noted that more dynamite had been placed at the critical panel points and covered with sandbags. Before leaving, Skerry instructed his men to lay still more explosives across the decks of the structures after all traffic had passed over. The bridges would then be ready.84

By the early morning hours of New Year’s Day SLF and NLF had cleared the bridges. A flank guard which had been stationed at Plaridel, some seven miles to the southeast, crossed over between 0430 and 0500. All U.S. and Filipino forces were now safely across the Pampanga—all except Manzano and his men, who were somewhere between Manila and Calumpit. Skerry asked Wainwright to delay the destruction of the bridges as long as possible in order to give Manzano’s party time to get across. Wainwright agreed to wait until 0600, even though he felt the situation was becoming more and more serious. Dawn was beginning to break, and rifle fire was increasing on the south bank of the Pampanga. Enemy patrols were getting close to the river. “In weighing the tactical importance of blowing the bridges and making the ... unfordable Pampanga a real obstacle,” wrote Skerry, “against waiting for a small group, that ... could withdraw to Bataan by other routes, ... [there could be] but one answer. ...” Wainwright directed Skerry to blow the bridges. At 0600, the engineer went to the men waiting at the two abutments and instructed them to fire the highway bridge at 0615, the railroad bridge immediately thereafter. Wainwright and the members of his staff took cover, and

the engineers lit the fuses. After a few minutes the huge charges went off with a tremendous roar and the spans fell into the river. The broad Pampanga lay in the path of the enemy.85

As the Japanese columns neared Manila, the engineers touched off large-scale demolitions in and around the city. Preparations for denying the enemy everything of military value had been under way for more than a week. Industrial plants, radio stations, warehouses and shops of the Manila Railroad, Nichols and Nielson Fields, and Fort McKinley were to be wrecked. Supplies which could not be moved to Bataan were to be destroyed, all except food, the loss of which would inflict greater hardship on the Filipinos than on the Japanese. Casey was especially anxious to leave no oil, since the enemy’s stocks were extremely limited. He had therefore made elaborate plans for setting on fire the large oil tank farm in the Pandacan district. Roads and bridges within Manila were to be left intact. On 30 December the work of destruction began. On that day and the next, the city was dotted with fires and rocked by explosions, as the engineers put into effect their scorched earth policy.86

Demolition engineers were among the last to leave the city. One of the many to remain behind was Earle Bedford, before the war a civilian engineer in the islands, and now in charge of demolition work south and east of Manila in the provinces of Cavite, Batangas, Laguna,

and Rizal. Casey had instructed Bedford to stay in Manila as long as possible to destroy any military equipment he could find, and to make his way to Bataan by whatever means he could command. Bedford and his men destroyed three large bridges and many small ones south of the city. They wrecked the piers at Wawa. While mining bridges, they noticed about twenty-seven native houseboats and barges moored in the tidal waters of the rivers. Bedford succeeded in burning four in the Imus River, but the strenuous objections of the owners stopped him from setting the rest on fire. On New Year’s Day he and his crew of Filipinos destroyed quantities of abandoned supplies at Fort McKinley. With another American civilian he went to Pandacan to ignite any remaining supplies of gasoline and oil. The two men found three tanks still intact but surrounded by moats of burning oil. Unable to get near enough to place explosives against the valves, they used rifle fire to perforate the center tank and then ran to escape the ensuing explosion. On 2 January, the day the Japanese occupied the capital, Bedford arranged to leave for Bataan by boat. But while on his way to a rendezvous with two of his Filipino foremen in Intramuros, the old walled city of Manila, he was picked up by the Japanese and interned at Santo Tomas University for the duration of the occupation. Many who stayed behind shared Bedford’s fate, but others managed to escape, some finding small boats to take them across the Bay. Among those eluding the enemy were Manzano and his men, who, after destroying six bridges just north of the city, made their way to

Bataan by walking across country and slipping through the Japanese lines at night.87

Meanwhile, American and Philippine forces were completing their withdrawal to Bataan. After clearing the bottleneck at San Fernando, troops of NLF and SLF withdrew southwestward. The rearmost units passed through Layac Junction, at the entrance to the peninsula, in the early morning of 6 January. Here was the last bridge over which the troops had to pass. Before destroying the bridge, Captain Chanco asked the officer commanding the covering force of tanks whether his last tank was across. He replied it was, Skerry later recalled, “taking the usual position for a military oath and swearing by all that was holy all his tanks had crossed. The enemy was not immediately at hand, so a delay was ordered. Suddenly from out of the darkness one of his own tanks came rumbling along!”88 When the last tank had crossed, Chanco destroyed the bridge. The withdrawal to Bataan was complete.

Bataan

The Philippine campaign, so far a war of movement, was henceforth to be a war of position. The defenders of Bataan were to undergo one of the most protracted sieges of World War II. How long they could hold out would depend to a considerable extent on the strength of their fortified positions. One of the oldest arts of the military engineer is the construction of field-works, and here was a situation requiring all his skill and experience. Lines had to be drawn that would give the weak American and Filipino forces the greatest advantage. Positions had to be made as strong as possible and given the utmost support. As they dug in, the beleaguered troops were conscious of their desperate situation but were sustained by the hope that help would come before an overwhelming attack or attrition forced them to surrender.

The terrain was on the side of the defenders. About twenty-five miles long and twenty miles wide, rugged, jungled Bataan provided many areas where a small force could hold off a superior one. (Map 6) Down the center of the peninsula ran a steep mountain range, with two prominent peaks, Mount Natib in the north and Mount Bataan in the south. The deep jungles of western Bataan, especially, favored the stationary defender rather than the attacker. Here trails afforded the principal means of communication. During the day the oppressive heat made travel through the forests exhausting. Nights were cool, but the dense vegetation reduced visibility almost to zero; even when the moon was full, movement was almost impossible except along well-worn trails. Less primitive was the eastern half of Bataan. Along the coast were several towns, among them Limay, Orion, and Pilar, soon to figure prominently in the fighting. While the many rice paddies would furnish the defenders with good fields of fire, there were fewer strong positions than in the western half of the peninsula. Bataan had two roads suitable for vehicular traffic. One, a single-

Map 6: Bataan, 1942

lane coastal highway, ran south along the eastern shore to Mariveles at the tip, crossed over to the western side, and extended north as far as Moron. The other stretched across the middle of the peninsula from Bagac to Pilar.89

Early in January, Casey and Stickney went to Bataan to help organize the defenses, setting up their offices at “Little Baguio,” high on the southern slopes of the Mariveles Mountains. As Engineer, USAFFE, Colonel Casey was to supervise all engineer activities during the siege. By early January he had eight officers to assist him. Five remained with their chief on Bataan; three were sent to MacArthur’s headquarters on Corregidor. As service command engineer, Colonel Stickney was to be responsible for work in the rear areas, including all construction. A week after war began, Washington had ordered the duties of the constructing quartermaster in the islands transferred to the department engineer.