Chapter IV: Build-up in the Southwest Pacific

Concurrently with their campaign in the Philippines, the Japanese swept rapidly southward into the Netherlands Indies, and were, before long, menacing Australia and the islands of the South Pacific. In all of that vast area Australia remained as the one practicable base of resistance. Because of its great size, the country could not easily be overrun. With its small but expanding munitions industry, its armed strength, and its factories and farms, the Commonwealth could contribute substantially to the Allied effort against Japan. But Australia’s resources were too slender, its population too sparse, and its defenses too weak to resist a possible Japanese invasion effectively or to launch offensives without aid from its allies. The continent had to be transformed into an Allied bastion and a base from which to strike back. To reach such a goal, the amount of engineer work required would be enormous.

Australia—The First Days

Defense Plans

During the early weeks after Pearl Harbor, Australia had assumed an ever greater importance in Allied strategy. Within ten days Secretary Stimson and General Marshall had decided to establish a base on the southern continent from which to supply the Philippines and provide air support for General MacArthur. By Christmas it was apparent that efforts to help the forces in the Philippines, the bulk of them already withdrawing to Bataan, would be of little use. The Allies had to concentrate on holding farther south, and their hope now was to save the Netherlands Indies. Although Roosevelt and Churchill, meeting at the ARCADIA Conference in Washington in late December, agreed to direct the main Allied effort against Germany first, the seriousness of the situation in the Far East prompted them to divert additional strength to the western Pacific. America’s chief contribution was to be air power based on Australia. Toward the close of the year the War Department took steps to send nine air groups to the southwest Pacific.1

The outbreak of war with Japan was to put a heavy strain on Australia’s resources. As large as the United States, the Commonwealth had a population of

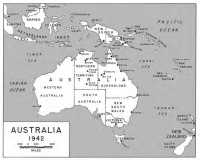

Map 7: Australia, 1942

but seven million. Only the southeastern areas were highly developed; two-thirds of the total population lived in the two states of Victoria and New South Wales. (Map 7) Natural resources were limited, with agricultural and pastoral products forming the foundation of the country’s economy. By American or European standards, Australia’s industrial system was small. Its communications network was poor. Except in the southeast, there were few paved roads. Most rail lines were single track and gauges in the various states ranged from three feet six inches to five feet three inches.

Most of the Commonwealth’s trained fighting forces were overseas at the time of Pearl Harbor. Nearly all of the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) were fighting in Europe and the Mediterranean or helping to protect the Middle East and Malaya. The two heavy and three light cruisers, which comprised the bulk of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), had only recently returned to home waters after serving in the Mediterranean

and the Indian Ocean. The air force assigned to defend Australia consisted of forty-three British and American bombers and an equally small number of Australian-built training planes. The troops on hand included the Australian Military Forces (AMF)—a militia poorly equipped and with little training—and one AIF armored division without its tanks. There was, besides, the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC), an organized reserve of some 50,000 men, most of them veterans of World War I.2

Because their means were limited, the Australians understandably adopted a defensive strategy. Soon after the Japanese began their rapid thrust southward, the Australian Chiefs of Staff had come to the conclusion that any attempt to hold the islands northeast of the continent or even the underdeveloped, sparsely inhabited areas of the northern part of the Commonwealth would be ill advised. Should the Japanese invade, the Australians would have no choice but to abandon all territories except the southeastern corner of the continent containing the major cities of Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne. Most of the military forces in the Commonwealth were therefore concentrated in this important industrial and agricultural area. Only small forces were sent to such distant

outposts as Darwin in the northwest and the Cape York Peninsula in the northeast.3 Not unless the Australians received substantial reinforcements would they be inclined to adopt a more aggressive plan of action.

Reinforcements Arrive

A few reinforcements were soon to come from the United States. When Japan declared war, a convoy of eight transports, carrying men and supplies to the Philippines, was approaching the Fiji Islands. Instructed by General Marshall not to return to Hawaii but to go on to Australia, the convoy headed for Brisbane, arriving there on 22 December. The 4,600 men aboard, commanded by Brig. Gen. Julian F. Barnes, included a regiment and two battalions of field artillery and the ground echelon of a bomber group. There were no engineer units. Late in December Maj. Gen. George H. Brett, Chief of the Air Corps, at that time on a mission to Chungking, flew down to take command of the American troops. On 1 January his command was designated United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA). Marshall gave Brett two major tasks: get supplies to the Philippines and transform Australia into a major air base. As hope of getting help to MacArthur dimmed, Brett concentrated on his second objective.4

Australia, Brett declared, must be a “second England.” On 4 January he laid before the Commonwealth’s Chiefs of Staff his plans for strengthening the continent, placing special emphasis on the northern regions. His program called for constructing air bases at Darwin, Brisbane, and Townsville. He considered Darwin, centrally located on the north coast of Australia, an ideal site from which to launch operations against the Indies and the Philippines. This city would be both an advance air base and a port of embarkation for troops and supplies moving northward. Shipments of planes and airmen from the United States would put in at Brisbane, 1,800 miles to the southeast, where Brett wished to establish his main assembly plant and repair shops for all types of aircraft. Townsville, 750 miles north of Brisbane, was to be a secondary port and a subsidiary base for assembling and maintaining planes. To stage fighters to the Indies, Brett proposed to develop still further the existing air ferry route from Brisbane and Townsville to Darwin. He chose Melbourne as the major port of entry for troops and supplies and as the site for his headquarters. The Australians, while pointing out that the areas north of Brisbane would be difficult to defend, agreed to go along with Brett’s plan.5

A quick trip by plane over eastern and northern Australia revealed to Brett the magnitude of the job ahead. Melbourne and Brisbane would present little difficulty. They were large, modern cities, with deep harbors, well-developed roads and railroads, manufacturing plants, and indeed all the facilities of metropolitan centers. In the surrounding countryside were most of the airfields, camps, and depots of the Australian Army. Townsville and Darwin offered a sharp contrast. A commercial center for the sheepherders, farmers, and miners of northern Queensland, Townsville was a provincial city of 25,000. It was linked with the south by a single-track railroad and a rough coastal highway, neither of them designed to carry heavy traffic. Its harbor was too shallow for large ships. Except for nearby Garbutt Field, being developed for the air ferry route to the Philippines, and the field at Charters Towers, 65 miles to the southwest, Townsville had few of the facilities that go to make up an air base. Darwin, with 1,500 inhabitants, was about 2,000 miles from Melbourne and 1,800 from Brisbane. It had no rail connection with the rest of the continent. The only line out of the city, “two streaks of rust without much rolling stock,” extended southeastward for a distance of 300 miles and ended in the desert at Birdum. Not much better than cattle tracks were the roads leading to the more populous parts of the continent. Darwin’s docks could take only two ships at a time. Near the city were two small airfields—Darwin RAAF Field and Darwin Civil; a third, Batchelor Field, was located 40 miles to the south. Brereton, while visiting Australia in November 1941, had arranged for the improvement of Batchelor to enable it to take heavy

bombers, and the RAAF had begun work two days later. Circumstances now required not one, but a whole series of bomber fields in the Darwin area. As a result of his trip, Brett saw clearly that carrying out his plans would require large-scale construction, but he was convinced his program was necessary if the enemy advance southward was to be halted.6

Asked by the War Department for a rough estimate of his needs, Brett called for a large contingent of engineer troops and generous quantities of construction supplies. In cable after cable, he detailed his requirements—three engineer airdrome units, two labor battalions, one service unit, and one general service regiment; rock crushers, jack hammers, trucks, compressors, landing mat, trucks, 32,000 tons of rail, and 100,000 tons of asphalt. Marshall, when he saw the tack Brett was taking, became somewhat concerned and asked him to trim his sails. The Chief of Staff could not go along with plans for developing “a second England.” He explained to Brett that he did not intend to send many service troops to Australia and reminded him that the shortage of shipping was critical and that the War Department had to save “every possible ton of ship space.” American forces in Australia would therefore have to exploit local resources to the limit. Brett persisted in asking for large shipments, but Marshall refused to yield.7

Eager to do their part, the Australians promised Brett a “maximum measure of cooperation.” The Commonwealth government quickly agreed to furnish supplies, provide workmen, hire contractors, and turn over such buildings as could be spared. The Treasury foresaw little difficulty in financing projects. The Australians were careful to point out the limitations of their resources. They emphasized that construction machinery was scarce, that most of their manpower was already committed to defense, and that many materials, among them asphalt and bitumen, now so urgently needed for airfields, would have to be imported. The “most vital and difficult factors” in construction, they warned, “would be materials, labor, and time.”8

Engineer Tasks

Even though the Australians would do their utmost, the U.S. Army engineers

would have to assume heavy responsibilities. They would have to provide plans and specifications, advise in the selection of sites, and guide the Australians in the unfamiliar task of building for the American Army. The officers who had reached Australia by early January were far too few to carry the load. Brett informed the War Department that more engineer officers were urgently needed. He asked that Brig. Gen. Raymond A. Wheeler be sent posthaste to Australia, but since Wheeler was then on an important mission to Iran, General Reybold chose Col. Dwight F. Johns for assignment to the southwest Pacific. The Chief of Engineers also selected several officers of lower rank for Brett’s staff. Meanwhile, Maj. George T. Derby, who had come over on the convoy, served as Brett’s first engineer. Because Brett had so few men to staff his headquarters, Derby served also as finance officer and briefly as G-4.9

On 5 January, Derby moved from Brisbane to Melbourne and before long had set up his office on the top floor of an empty, ramshackle warehouse. During the course of the month, he added an engineer and two infantry officers to his staff and hired a small number of civilians. At the same time he fell heir to a ready-made engineering organization. The firm of Sverdrup and Parcel had built up a staff of Australian civilians for work on airfields for the South Pacific air ferry route. Derby negotiated a contract with the firm whereby he secured the services of about thirty skilled architects, engineers, and draftsmen. The Australians saw to it that he was well supplied with money. The story goes that he went to one of the Melbourne banks, introduced himself, and explained his needs for funds. The bank promptly made out a note for 1,000,000 pounds, adding that he was welcome to more if he needed it.10 Derby scarcely had time to do more than assemble a staff and secure funds before leaving early in February for Java. He was replaced temporarily by Maj. Elvin R. Heiberg.11

To decentralize operations, Brett had established four base sections on 5 January. Base Section One, with headquarters at Darwin, included Northern Territory. Two and Three were set up in Queensland, with headquarters in Townsville and Brisbane, respectively. Base Section Four, with headquarters in Melbourne, included Victoria in southeastern Australia. When the base sections were first organized, there were not enough engineer officers to staff them all. Capt. Willard Farrar was assigned to Brisbane and Maj. Ward T. Abbott to Townsville, while Derby himself, before his departure, assumed the duties of base section engineer in Melbourne. Darwin was left to the RAAF. Base section engineers, like the chief engineer, were to be staff officers only. Under the technical

supervision of Derby and his successors, they were to take orders only from their base section commanders.12

The engineers found themselves almost totally dependent on the Australians. Although the War Department gave Brett authority to use fixed-fee or negotiated lump-sum contracts to lease whatever properties he needed and to overobligate funds if necessary for urgent construction, the engineers could do little without Australian advice and assistance. Not acquainted with local contracting or supply firms, they called on the RAAF, which controlled most airfield work, and on government works agencies for help in getting projects started and pushing them to completion. Lacking knowledge of real estate prices. methods of acquisition, or terms of leasing, they turned to the Australian Army’s Hiring Service for land and buildings. Because of the Americans’ unfamiliarity with the local scene, setting up a procedure whereby the engineers as well as other branches of the Army could work together with the Australians was of fundamental importance. To bring about coordination at the highest level, Brett and the Australian chiefs of staff established three joint committees, made up of representatives of USAFIA and the Commonwealth’s armed services. The Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Joint Planning Committee, the latter composed of the deputy chiefs, were responsible for formulating “policies concerning the distribution of troops and facilities for the U.S. Army in Australia.” In other words, they would decide what to build and where. The Administrative Planning Committee had the task of recommending ways in which the construction effort could best be organized, materials and equipment equitably apportioned between Australians and Americans, and the work of the supply services coordinated. The decisions of these three predominantly Australian committees would greatly affect the progress of construction.13

Work for the Americans would have to be superimposed on a broad defense program which the Commonwealth government was already carrying out. Soon after the outbreak of hostilities in Europe, Australia had launched a large construction effort, designed both to strengthen the nation for war and to develop the postwar economy. By the time of Pearl Harbor, work had been undertaken on some thirty-five new munitions plants and on seventy-seven additions to existing ones. The RAAF was building fields for forty-two squadrons in the southern half of the continent. Tanks for motor gasoline were being erected at various points located inland at least one hundred miles from

the eastern and southern coasts, and storage for aviation gasoline was being provided at army and oil company depots. Two major links in the transcontinental highway system were being improved: one, the North-South Road from the railhead at Alice Springs to Darwin, the other, the East-West Road from Mt. Isa in western Queensland to Tennant Creek on the North-South Road. A huge drydock for capital ships was building at Sydney. Two large permanent hospitals were going up, one at Brisbane, the other at Adelaide. These undertakings were already taxing the Commonwealth’s slender resources to near capacity, and with the war coming close to Australia’s shores, a great deal of additional construction would be needed. In the south, where much could be turned over to the Americans, cooperation with the engineers imposed no great burden, but any help the Australians could give for the new projects in the north would have to be at the expense of their own program and in violation of their own strategic concepts.14

Construction Begins

At Melbourne, consequently, the engineers found their task fairly easy. Even though the city was crowded, the headquarters of the Australian Army, Navy, and Air Force being located there,

the Commonwealth government found space for the Americans. Headquarters of Base Section Four moved into the Seamen’s Mission, which Derby converted into an office building. He had the Sailor’s Home altered to accommodate the military police and turned a wool warehouse into an engineer depot. The engineers leased the Royal Melbourne Hospital, 95 percent complete when the war began, thus obtaining space for over 700 beds. They built barracks for enlisted men on the hospital grounds and provided lodgings for nurses and medical officers inside the hospital buildings. Many Americans found quarters in private homes, apartments, and hotels; others pitched tents on cricket fields, race tracks, and other flat ground.15

The establishment of a major base at Brisbane was to require more extensive work. In mid-January, Col. Alexander L. P. Johnson, the base section commander, together with his engineer, Captain Farrar, began pushing base development. Here, as at Melbourne, the Australians made a number of properties available, among them two large airfields, Amberly and Archerfield, a wharf near the mouth of the Brisbane River, and several warehouses. Queensland Agricultural College at Gatton, fifty-five miles west of the city, was also turned over to the Americans. Contractors were soon adapting these facilities to American requirements. At Amberly and Archerfield, they began building additional barracks, operations buildings, and bombproof shelters. Near the

wharf they erected frame office buildings, a warehouse, and a 40-ton crane. They began converting Queensland Agricultural College into a hospital with 250 beds. Quite a few new projects had to be undertaken. Colonel Johnson directed the building of eight frame warehouses to be dispersed throughout the city and arranged for contractors to build an ordnance depot in suburban Derra. Camps were a major requirement. Johnson selected a site near Wacol, fifteen miles southwest of Brisbane, and soon work was under way on a 5,000-man staging camp, later named Camp Columbia. He also set work in motion on a 1,000-man camp near Archerfield. Farrar designed both camps on a dispersal basis, with buildings to be constructed in wooded areas and concealed from air observation. By far the largest of the jobs was Eagle Farm air base, which was to be Brett’s main depot for assembling planes. Designing and laying out the two all-weather runways, assembly plant, hardstandings, shops, and warehouses and finding contractors, workmen, plant, and materials presented Johnson and Farrar with a real challenge, but, with Australian help, they soon succeeded in getting construction started.16

Farther north the engineers faced a tough assignment. At Townsville, destined to be the great base in northeastern Australia, most construction would have to be from the ground up. Brett wanted a plant for assembling fighters, shops for repairing them, and a great deal besides.

Because of the grave danger of Japanese raids, a strong air defense was needed, but placing more fighter planes at Townsville would necessitate construction of at least one new airdrome to supplement the bomber fields at Garbutt and Charters Towers. If oceangoing vessels were to use the port, the harbor would have to be deepened, new wharves built, and roads to the docks improved. On 5 January the base section commander, Brig. Gen. Henry B. Clagett, and his engineer, Major Abbott, arrived. After checking in at their hotel, they set out for a conference at the local headquarters of the RAAF. Having discussed their needs with the Australian airmen, they inspected several airfield sites selected earlier by General Brereton and found them suitable. A tour of the town and the surrounding countryside convinced them that there were “acres of open country on which to build” but little else. Labor was scarce, many residents having fled to the south. Since local merchants stocked few of the items needed for large-scale construction projects, supplies were low. Despite the discouraging outlook, Clagett and Abbott went ahead. Within a few days, they had obtained the RAAF’s permission to award fixed-fee contracts and sent out a call for workmen to all the towns within a radius of 200 miles. By the ninth, contractors had been hired, workmen recruited, and construction started on barracks at Garbutt and on a fighter strip at Charters Towers.17

Brett considered Darwin the key point in the fight for the Indies and

Camp Columbia

Australia, and believed the establishment of a major base there was “absolutely necessary.” He nevertheless recognized that construction in the town and surrounding territory would be extremely difficult. Living conditions in this forbidding tropical outpost were almost unbearable. There were few workmen to be had, and supplies would have to be brought in by tortuous overland routes or shipped by sea from southeastern Australia. To develop Darwin fully would be a long-term proposition. For the time being it would have to serve merely as a staging area for air units moving northward. Brett called initially only for construction of a field for fighters, shops for emergency repairs, and housing for 2,500 troops. Since no American engineer could be spared for Darwin, he persuaded the RAAF to take charge of construction and asked the Australian Government to speed work on the road and railroad leading into the town. Although little could be accomplished immediately, Darwin continued to figure prominently in Brett’s long-range plans.18

The construction program, modest as it was, got off to a faltering start. During their first weeks, the engineers had to grope their way along. Since those who had arrived with the convoy had expected to serve in the Philippines, they

had not even brought along sets of drawings or field manuals.19 The engineers knew little or nothing of the local terrain, rainfall, or wind directions. “The rocks, trees, and soil,” wrote one, “were without parallel in our previous experience. The very stars and constellations were strange.”20 Derby, in Melbourne, at first had difficulty finding out what his engineers one or two thousand miles away were doing or what their needs were. They, on the other hand, with few regulations to guide them, did not always know how far to go in hiring contractors, buying supplies, and dealing with the Australian authorities. Small wonder that construction appeared to be slow in getting under way. When General Brereton visited Australia in late January he complained that “conditions at Darwin were unsatisfactory” and that projects at Brisbane had not “progressed beyond the planning stage.”21

Difficulties in procuring scarce building materials and equipment also had a hampering effect. Of the raw materials needed for construction, only iron ore and timber were plentiful, and the country’s capacity for turning them into finished products was limited. The output of hardware, steel plate, and lumber fell far short of wartime demands, as did the production of roofing and pipe. Cement was the only manufactured product produced in ample quantities. Bitumen was almost impossible to get. Manufacturers

turned out fairly large numbers of concrete mixers and light tractors and trucks. They also produced certain other items of equipment, but without essential parts, which had to be imported; bearings for carryalls, for example, had to come from abroad, as did motors for graders. Spare parts for all types of machinery were at a premium. Only a thin trickle of supplies came from the United States. The Chief of Engineers had little to spare for overseas, and the European Theater of Operations got first priority on that. And, to make matters worse, the shipping shortage slowed delivery of such items as could be earmarked for the southwest Pacific.22

Competition for such supplies as there were further aggravated a bad situation. The Australians placed orders without reference to the needs of the Americans, who also bought up meager stocks, heedless of the requirements of their allies. The American services likewise bid against each other. On 21 January the Commanding General, USAFIA, in an attempt to bring about more orderly procurement, ruled that all supplies procured locally must be obtained through Australian military channels. Also, base section commanders could purchase on their own authority only in amounts up to $500; purchases costing more had to be approved by USAFIA. While this order prevented a good deal of indiscriminate buying, it did not put an end

to competition among the American services. Nor did it stop the Australians from pouring materials into projects which some engineers were beginning to think were unnecessary.23

Total War

By the beginning of 1942 the Japanese had bottled up MacArthur’s forces on Bataan and Corregidor, and enemy troops in Malaya were driving on Singapore. In mid-January, in order to have more unified direction of the war against Japan, the Allied governments had established the ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian) Command, under General Sir Archibald Wavell, commander in chief of the British Forces in India. Wavell’s main task was to hold the Malay Peninsula and the Netherlands Indies. General Brett was named his deputy. The American forces in Australia now became in effect a supply service of ABDA. Wavell’s hastily organized command could not contain the Japanese; the enemy continued to advance, ‘fanning out in several directions. On 23 January the Australian base of Rabaul, at the northeast tip of New Britain, fell. On 15 February Singapore capitulated. The enemy was already invading Borneo and Sumatra and preparing to strike at Java. On the 19th Darwin was heavily bombed. The entire Indies appeared to be doomed, and on 25 February, the ABDA Command was dissolved. Wavell returned to India and Brett to Australia, which now seemed threatened not only from the northwest but also from the northeast.24

Where the Japanese would strike next was a question. Brett believed they would launch an attack from the northwest and seize Darwin. The Australian Chiefs of Staff held that the real danger lay to the northeast; the Japanese would want to sever lines of communication between the United States and Australia to prevent reinforcement of the southern continent. Immediately threatened, the Chiefs of Staff believed, were not only New Caledonia and Fiji, but also Port Moresby on the southern coast of New Guinea. To meet the growing peril, Australia would need air power and considerable numbers of ground troops as well. Prime Minister John Curtin had already ordered the AIF divisions home. Roosevelt and Marshall, reversing their earlier stand that only air and service troops were to be shipped to Australia, decided to send ground troops. On 17 February Marshall ordered the 41st Infantry Division to Australia and in early March Roosevelt promised Curtin the 32nd Infantry Division also, if the Commonwealth would keep one of its divisions in the Near East. Curtin agreed. With the first troops of the AIF scheduled to return in mid-March and with the American 41st Division due to arrive in April and the 32nd in May, the outlook for the defense of Australia appeared to be less desperate.25

The planned concentration of Allied power in Australia made necessary a

vastly expanded construction program. Upon his return from the Indies, Brett called for a redoubling of efforts to strengthen the northern bases. Runways at Darwin and Townsville were to be lengthened and the fields provided with camouflaged dispersals. The capacity of the assembly plants at Brisbane and Townsville was to be increased and work on them speeded up. In fact, nearly all the going projects were to be enlarged and given new impetus. Brett knew that this was not enough, and that many new jobs would have to be undertaken. He proposed to build 6 more bomber fields—three near Darwin, 2 near Brisbane, and 1 to the west of Townsville—and 4 more fighter fields—2 south of Darwin and 2 near Townsville. At Darwin he projected a host of smaller jobs, among them increasing the water supply and replacing the bombed-out wharf. He also planned to build a score of aviation fuel depots to be scattered over the continent. The Australian Chiefs of Staff agreed with Brett on the importance of all these projects and at his request gave top priority to those in the Darwin area. But since the steady Japanese advance had forced Allied supply lines southward and increased the danger to the southern part of the continent, Americans and Australians alike recognized the need for additional construction there. Camps and depots would have to be clustered around Melbourne and Adelaide, the safest ports of entry. Airfields would have to be developed in southwestern Australia, particularly around Perth, to defend the continent against attack from the Indian Ocean. On 3 March Brett established two new base sections: Base Section Five

in South Australia, with headquarters at Adelaide, and Base Section Six in Western Australia, with headquarters at Perth.26

Engineer Problems

The engineers were in no position to plan for and direct adequately such a constantly growing construction program. Their staff sections in USAFIA were hardly bigger than they had been in January. Now headed by Brig. Gen. Dwight F. Johns, who had arrived from the United States by way of Java on 28 February, the engineer office in Headquarters, USAFIA, consisted of 4 officers, 3 enlisted men, and 45 civilians. The offices in the base sections in Victoria and Queensland were still undermanned. Engineers had yet to be found for Darwin, Adelaide, and Perth. The difficulties of building in a foreign land were becoming more apparent. Like the other defenders of Australia, the engineers speculated daily on the next Japanese move and had to plan for the construction program in an atmosphere of growing tension. Worried about the future and uncertain over how to proceed, they had the task, as one high-ranking officer put it, of “developing a country the size of the United States.”27

Because so much construction had to be done in the north, reconnaissance alone required a vast amount of time

and effort. In order to find suitable sites for airfields in this largely unexplored region, the engineers took to the air. General Johns chartered a private plane to fly his engineers on inspections. He was fortunate in finding a civilian pilot who “knew well the behavior of soils under traffic, the class and quality of timber which grew on the various soils and possessed the ability to recognize these.” The pilot usually flew at an altitude of 5,000 feet. When he spotted a promising site, he dropped down for a closer look, sometimes circling not much higher than the treetops. Ground parties later surveyed about one-fifth of the areas recommended by the aerial observers and chose the best ones. This method of selection worked so well that it soon became common practice.28

A severe handicap was the lack of plans and specifications. Having no American blueprints, Derby had directed the men transferred from Sverdrup and Parcel to develop suitable designs. Because these men had no acquaintance with the American Army’s standards of construction, they had to gather information from every possible source. They questioned officers who came into engineer headquarters, visited Australian camps occupied by U.S. troops, and studied Australian plans. At length they succeeded in producing some tentative drawings, though still too few to fill the needs of contractors, who consequently adopted designs of their own choosing. The result was that many facilities were overelaborate. Cables

were sent to the Chief of Engineers for complete sets of the standard drawings for theater of operations buildings, which the Engineers had prepared in 1939 and 1940 to simplify overseas construction in time of war. Some time elapsed before the drawings arrived. One package containing plans for different types of airdrome structures was lost in a plane crash. After the engineers had received fairly complete sets of standard drawings, they discovered that quite a few alterations were necessary. Australian hardwoods, among the strongest in the world, had such unusual bearing qualities that much less timber was needed than the theater of operations drawings called for. The plans also had to be modified to conform to Australian sizes of materials. In fact, such radical changes were required that there was some question as to whether the drawings should be used at all. The engineers debated whether it would not be preferable to switch to Australian designs or perhaps develop entirely new plans. The matter was not to be settled for some weeks.29

The growing construction program placed a tremendous strain on Australia’s manpower and production. Early in February the Administrative Planning Committee had recommended that the Commonwealth government set up more effective machinery to direct construction for the armed forces, Australian and American. On the day Singapore fell, 15 February 1942, Prime Minister Curtin determined to put Australia’s

manpower and resources on a “total war basis.” In line with this policy, the Australian Government established the Allied Works Council (AWC) on 26 February. The council was to direct and control “the carrying out of works of whatever nature required for war purposes by Allied Forces in Australia.” Curtin appointed Mr. Edward G. Theodore, former Commonwealth treasurer, as director general, and Mr. C. A. Hoy, head of the works agency of the Department of the Interior, as assistant director. General Brett, asked to nominate a third member, chose Major Heiberg, who was succeeded within a few days by General Johns. The council was given broad powers, including the right to commandeer supplies and equipment, condemn property, and adopt any form of contract that would expedite construction.30

Theodore and his colleagues strove to bring order into the building program. Meeting in Melbourne, they began at once to assemble a staff and to establish offices in each of the states and in Northern Territory. The state organizations would hire contractors, recruit workers, and obtain materials and equipment. Finding it almost impossible to use peacetime methods of contracting, the council adopted the fixed-fee contract for the bulk of the jobs, offering builders an average profit of 3 percent of the estimated cost. In order to alleviate shortages of supplies and equipment, the AWC surveyed existing stocks, impressed privately owned machinery, searched for ways to increase production, and sent urgent requests to the American government for lend-lease aid. One of their major tasks, the members of the council believed, was the recruitment of workers. At first, they relied on private industry and on state construction agencies, such as roads commissions, to round up additional laborers. Appeals for volunteers met with little success. Men could not be readily persuaded to leave defense jobs in Melbourne and Sydney to go to work in the inhospitable regions of the north. When the manpower shortage continued acute, the council considered drafting workers but hesitated to take this unpopular step unless there was no alternative.31

The Allied Works Council was no panacea. It could not alter the basic fact that Australia’s resources were limited, nor could its members simply ignore political considerations and insist on unpopular measures. It had, moreover, to operate as part of a cumbersome system. Before work on a project could begin, the council had to obtain the approval of what many thought was an inordinately large number of governmental bodies, military and civilian. Among them were the Administrative Planning Committee and the Chiefs of Staff Committee, who assigned priorities. The

ministers of the Australian armed services were notified of pending construction so that they might determine if existing facilities could be used. The Treasury reviewed projects for American forces to arrange for financing through reverse lend-lease. The war Cabinet reserved the right to pass upon all large projects or those of a controversial nature. Only after all these agencies had approved was the Allied Works Council permitted to go ahead with construction. All too often this procedure proved to be exasperatingly slow.32

Yet, despite many obstacles, the Allied Works Council could by mid-March report considerable progress. The number of going projects was mounting steadily. Most of the new jobs were in the south, where the council was to perform extensive construction for the Australian services and provide numerous key facilities for the Americans. Expansion of camps near Melbourne and Brisbane was continuing. A beginning had been made on the largest job in the entire airfield program—the Tocumwal Repair and Assembly Depot in New South Wales, located on the Murray River, which formed the boundary with Victoria. This gigantic project, covering sixteen square miles, was to include 4 runways for heavy bombers, seventy miles of roads, and 608 buildings. But while the bulk of its effort was in Victoria and New South Wales, the council was beginning to devote some attention to the north. Work on roads leading from South Australia and Queensland to Darwin was being speeded up. An accomplishment the AWC took particular pride in was the launching of work on new runways at Charters Towers. The council’s field representative in Queensland received the request for this job on a Saturday night early in March. He at once suspended operations at most of the other projects in the area and ordered the equipment sent to Charters Towers. He requisitioned three trains to haul the machinery and called workmen from their homes to get everything in readiness at the airfield for construction to begin. By Monday morning 200 men, with 100 trucks, i 2 bulldozers, and a large number of scoops, tractors, and graders, were hard at work. The Australians, well aware that they were just embarking on a vast undertaking, were eager to get on with the program as a whole.33

First Engineer Units

While the Australians were intensifying their efforts, the first engineer troops arrived from the United States. On 2 February the 808th Aviation Battalion had landed at Melbourne. The people of the city, says the battalion chronicler, “were very glad to see the U.S. forces come in” and gave the 808th a “rousing welcome.” But the men so warmly received were in some ways unprepared for the task ahead. Activated in September 1941, the 808th, like most of the early aviation battalions, had received only haphazard training. The unit arrived without its heavy equipment, except for three dump trucks and two

tractors. The bulk of its machinery was to follow later. Brett lost no time in giving the unit its assignment. Under Capt. Andrew D. Chaffin, Jr., the 808th was soon on its way to build airdromes in the Darwin area.34

The long journey northward introduced the engineers to the Australian transportation system. On 12 February the men went by truck to Baccus Marsh near Melbourne, where they boarded a special train. The next day, on reaching Terowie, in the state of South Australia, where the broad gauge ended, they transferred to the narrow gauge line which ran through the desert to Alice Springs, a thousand miles to the north. Having a top speed of twenty miles an hour, the train did not reach Alice Springs until 2130 of the 15th. Since there was no railroad northward out of the town, trucks carried the troops on to Larrimah, 635 miles distant. The passengers found the road rough and the “vibration ... terrific.” Arriving in Larrimah on the 18th the men “broke out laughing” when they saw the train that was to take them on to Darwin. “It consisted,” one wrote, “of cattle cars for personnel, small open cars (trucks) for baggage, and a small wheezy locomotive which looked as though each hour of existence would be its last.” The Australian crew’s custom of stopping every few hours to have a “spot of tea” was an added irritation to the Americans, who were impatient to get to their destination. On 19 February the battalion left the train at Katherine, the site of one of the new bomber fields, instead of going on to Darwin, 200 miles to the north, which that day had been hard hit by an air attack. After experiencing the difficulties of movement between Melbourne and the Darwin area, the men of the 808th, deep in what the Australians called the “Never-Never” land, felt “completely isolated as far as the remainder of the U.S. Army was concerned.”35

The 808th got orders to turn the civil airdrome at Katherine into a field for medium bombers and to find sites for new fields in the area. On his own initiative, Chaffin undertook another project in order to eliminate the need for transshipping cargoes at Larrimah. He decided to improve the road from that point northward so that supplies could be trucked all the way from Alice Springs. The battalion quickly settled down to work. Survey parties, sent out daily, located several good sites for airfields. Men of Company B began removing trees and providing detours around bad spots on the road to the south. At first, the 808th made scant progress on runways. On 6 March Captain Chaffin reported “little ... has been done towards building airfields in this vicinity because of the complete absence of equipment.” The battalion had brought to Katherine only the three dump trucks and two tractors it had unloaded at Melbourne in early February. Chaffin had been able to obtain it cargo trucks and 2 old bulldozers at Darwin. But at least 7 of his 14 trucks were needed to keep the battalion supplied with food and water. The others were

used to haul gravel for the Katherine runway. The cargo trucks were of the type which had to be emptied by hand; unloading these trucks in the tropical sun was so exhausting that the men could work only six hours a day. Still, in spite of these handicaps, occasional Japanese bombings, and the ever-present dread of enemy invasion, the battalion persevered. By mid-March the Katherine runway had been lengthened and was being surfaced with gravel, and the clearing of three sites for new strips had begun.36

Prospects for construction in Australia brightened with the arrival at Melbourne on 26 February of two general service regiments—the 43rd, commanded by Lt. Col. Heston R. Cole, and the 46th, commanded by Lt. Col. Albert G. Matthews. Since these units were older than the aviation battalion, they had received more extensive training in the United States. The 43rd, activated in April 1941 and given seven weeks of basic training, had in June taken part in army maneuvers in Tennessee, where, according to an observer from the Office of the Chief of Engineers, the men had performed “as nearly like veteran troops as could possibly be expected from such a short training period.” The 46th, activated in July 1941, had undergone training in road building, airfield construction, bridging, fortification, and demolitions—the usual instruction given to general service regiments—and in addition had had the benefit of experience in the Louisiana maneuvers in the fall. On 23 January 1942 the 46th and the 43rd had sailed for Australia; three weeks

later the bulk of their equipment was shipped. The units were at full strength when they landed, but did not long remain so. “USAFIA shanghaied both officers and men ruthlessly ... ,” Matthews wrote. Brett took the 46th’s motor repairmen for the base motor pool at Melbourne. When their vehicles arrived early in March, the commanders discovered that the spare tires had been removed in the States. The first days in Australia seemed to portend difficult times ahead.37

The 43rd Engineers began work almost at once preparing Camp Seymour near Melbourne for the 4 1st Division, expected in April. Seymour was an old Australian tent camp. With the addition of huts for kitchens, mess halls, showers, latrines, recreation buildings, and hospitals, it was quickly made ready to accommodate the American division. In mid-March, when the 43rd received its vehicles, the headquarters and service company and the 1st Battalion left to join the 808th in Northern Territory. Except for one company which remained at Seymour, the 2nd Battalion moved to Adelaide to enlarge Australian camps there for the 32nd Division. Using materials supplied by the Commonwealth’s Department of Defence, the Engineers strove to complete the facilities by the time the 32nd would arrive in May.38

After two weeks of combat training near Melbourne, the 46th Engineers left by rail for northern Queensland, an area which might at any time become a battle zone. To protect themselves against enemy air attack the men mounted machine guns on the flatcars of their trains. During the trip they passed trainload after trainload of refugees headed southward. On 13 March the first of the troops reached Woodstock, a town twenty miles southwest of Townsville. Here and in the surrounding countryside the regiment was to build airstrips so vital to the defense of the Townsville area. Colonel Matthews was under exceptional orders. Since the officer who commanded Base Section Two was a major, Matthews was to report directly to General Johns. Matthews was to be largely responsible for the development of airfields in northeastern Australia in the critical days of early 1942.39

On 18 March the entire regiment began the work of clearing and grading three runways for a giant airfield at Woodstock. Matthews ordered around-the-clock operations, scheduling three 8-hour shifts a day. Because general service troops were trained as jacks of all engineering trades rather than as specialists in airfield construction, their equipment included no rooters, rollers, or scrapers. The troops worked mainly with picks and shovels, keeping their trucks and few dozers in reserve for pushing over trees and pulling out stumps. Even final grading often had to be done by hand. Still, the regimental historian reports, “the men were eager and enthusiastic, and went about their work with vigor ... troops laboring under the intense heat of the sun, and in clouds of dust, slashed away at trees and stumps. ...” Four days after construction began, the first plane landed on one of the runways. Matthews had meanwhile lined up sites for additional strips, but soon the regiment was dispersed. On 22 March Company A arrived at Torrens Creek, a small town about 180 miles southwest of Townsville. Here the men rapidly cleared the site and laid steel mat, 2,500 by 100 feet, in five days—possibly, they thought, a speed record for putting down mat up to that time.40 On 29 March, Companies B, C, and F moved to Reid River, 40 miles south of Townsville, where they began building a third airfield. Although this job, undertaken in a heavily wooded area, required much clearing, the first landing strip was ready by 15 April.41

Matthews described the construction of these airstrips as “field improvisation at its ... best.” The officers of the 46th were largely on their own and “did what seemed good to them and in most cases their engineering common sense was the primary and single qualification for the work.” Construction was held to the simplest standards. Because equipment was short, dispersal taxiways,

hardstands, and revetments were omitted. As the long dry season was just beginning, drainage was dispensed with. Since the engineers had no asphalt or tar, they surfaced the runways with rotted granite, semi-decomposed shale, or sometimes merely with gravel and clay. The fields were rough and crude, but planes could land on them. Construction took a heavy toll of equipment. Machinery broke down quickly under hard usage. Constant turning and twisting over rough ground wore out the front tires of the graders, and the tires of many of the trucks were slashed by the stumps of eucalyptus trees, cut off by Australian surveyors just above the ground. Having no maintenance repair truck, Matthews converted a motorized earth augur, “which wasn’t any good anyway,” into a mobile shop and equipped it with tools obtained from the Air Forces and the Australians. For repair work, he relied on men “who ... weren’t experts but ... learned fast.” The shortage of tires was remedied when the 46th took over a retreading plant whose workmen had been evacuated from the Townsville area.42 Despite the regiment’s many difficulties, building in the bush country of northern Queensland was, as Matthews pointed out, “excellent training for the officers and men engaged in doing much with nothing, [and] ... living under the most primitive conditions. ...”43

Supplies

If Brett and Johns were cheered by the coming of engineer units, they were no less gratified by the decreasing competition for supplies. On 21 February the Commanding General, USAFIA, had set up the American Procurement Commission, in response to General Marshall’s suggestion that a central purchasing board be established in Australia, “along the lines which were so successful ... in France during the last war.” The new commission included representatives of all the Army’s procurement services, with Heiberg serving as the Engineer member. Henceforth the services had to send requests for supplies to the commission, which determined priorities and placed orders with the Australians. On 20 March the organization was renamed the General Purchasing Board. It soon succeeded in bettering relations with the Australians and in effecting a more equitable distribution of supplies among the American services.44

Ships fleeing before the Japanese advance through Malaya and the Indies meanwhile were bringing large quantities of “distress cargo” to Australia. Ports were crowded with fugitive merchantmen; so great was the mass of material dumped at Sydney that the wharves threatened to collapse. Many ships had to anchor in the harbor to await their turn to unload, and once they docked, supplies were hurriedly removed and thrown into warehouses. The Australian Department of Import Procurement took possession of the cargoes and began

sorting them, after which the Commonwealth government gave the U.S. Army first choice of all goods brought in by American and Dutch vessels. Distress cargo proved to be a windfall for the engineers, providing them with more tools, steel plate, pipe, cable, generators, and construction machinery than any other source.45

One of the ships which had escaped from Java brought Mr. Albert Wright, a petroleum executive of many years’ experience in the Indies. The engineers immediately pressed him into service, commissioning him a major. Named Johns’ supply officer, Wright was ordered to get equipment quickly. After conferences with officers of the 808th, the 43rd, and the 46th, all of whom stressed the urgent need for earth-moving machinery, Wright began requisitioning farm tractors from the Australians. But these machines were too light for the job, and, since most of them were secondhand, large stocks of spare parts would have to be found. When Wright’s efforts to get parts from dealers met with slight success, distress cargo again proved a godsend; a shipload of parts for caterpillar tractors enabled the engineers to keep most of their equipment running. Meanwhile, rock drills, wire rope, and hand tools from Australian gold mines supplemented the engineers’ meager stocks of equipment, and carbon dioxide cylinders from breweries were rebuilt to hold oxygen for use in welding. While the engineers still had too few supplies and too little equipment, their lot was gradually improving.46

A New Command

On the morning of 17 March the planes bringing MacArthur and his staff from the Philippines to Darwin landed at Batchelor Field. From there the group traveled by plane, train and automobile to Melbourne, where MacArthur set up his headquarters. He and his staff at once began to take stock of the situation. General Casey was particularly anxious to get out into the field and see construction projects firsthand. On 28 March, accompanied by Johns and Theodore, he flew to Amberley Field near Brisbane, which he found “well provided with paved runways.” Proceeding to Eagle Farm, he noted that one 5,000-foot runway had been surfaced and another was under construction. The strips at nearby Archerfield were of turf, soft in spots and slippery when wet. Troops were moving into the recently finished camps near the fields. Inspecting these camps, Casey was disturbed by the “relatively high type construction,” which included tongue and groove flooring, asbestos roofing, and waterborne sewage systems. He suggested that “temporary and less costly shelter ... be provided.” The members of the party continued on to Townsville, where they were met by Colonel Matthews, who took them to see the fields being built by the 46th Engineers. Casey pronounced the fields “excellent” and was

pleased to find the troops still out working at 2200. The activities of the Australians at Townsville evoked less enthusiasm. Much effort was going into the dredging of the harbor and the improvement of the road to Brisbane; Casey wondered if such jobs might not be suspended and the men and equipment put to work on airfields. Nor was he overly impressed with Charters Towers. He noted much equipment on hand but remarked that there were not enough men to run it. The job, he felt, should be reorganized and given a “general push.” The tour convinced him that designs must be simpler, equipment and manpower allocated more wisely, and efforts centered first of all on airfield construction. Much good work had been done, but the program required better overall direction.47

Toward a More Aggressive Strategy Strategic Plans

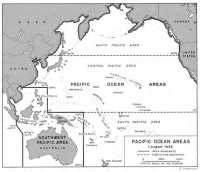

While MacArthur had been making good his escape from Corregidor, American and British plans for carrying on the war against Japan were beginning to crystallize. On 9 March President Roosevelt proposed that the United States assume responsibility for the conduct of the war in the Pacific; on the 18th Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill agreed. The Joint Chiefs of Staff meanwhile were dividing the Pacific into two main theaters, the Pacific Ocean Area (POA) and the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). (Map 8) The latter was to include the large land masses, Australia, New Guinea, the East Indies (except Sumatra), and the Philippines, as well as the Bismarck Archipelago and part of the Solomon Islands. POA was to include most of the remainder of the Pacific. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who already commanded naval forces in this area, was named commander in chief of Allied forces. Roosevelt’s choice for command of all Allied air, sea, and ground forces in the Southwest Pacific Area was MacArthur. The Australians received Roosevelt’s nomination of the general with great enthusiasm. Almost from the time of his arrival in the Commonwealth, MacArthur had had the prerogatives if not the title of commander in chief. His nomination as supreme commander approved by the governments concerned, MacArthur on 18 April officially assumed his position as the leader of the Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific. He organized three new commands under his own General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area: Allied Land Forces under Australian General Sir Thomas Blarney, Allied Air Forces under General Brett, and Allied Naval Forces under Vice Adm. Herbert F. Leary. Continuing under MacArthur’s direction were USFIP, commanded by General Wainwright, and USAFIA, now headed by General Barnes. As set forth in Marshall’s orders, MacArthur’s mission was threefold: to hold Australia, prevent the Japanese from cutting supply lines to the United States, and prepare to take the offensive.48

Map 8: Pacific Ocean Areas, 1 August 1942

MacArthur, on arrival at Melbourne, had learned of the plans of the Australian Chiefs of Staff which called for a defense of the southeastern part of the Commonwealth. He almost at once came to the conclusion that a different strategy was needed. Plans for continental defense he rejected as impractical. To hold the vast stretches of the sparsely inhabited country would require a large army; even

twenty-five divisions might not be enough. Considerable air and naval power would also be necessary, and no such force was available or in prospect. In the near future, the Southwest Pacific could count on having only two American and possibly three Australian divisions and small naval and air forces. But, MacArthur reasoned, it might be possible, with only limited forces, to ward off invasion by striking enemy-held islands and enemy naval forces and shipping during an attempted approach to

Australia. The Japanese seemed most apt to try to seize the rich industrial regions of Victoria and New South Wales rather than the barren deserts of the west and north. Consequently, the islands to the northeast appeared most liable to attack. Port Moresby, on the southern coast of New Guinea, would be a particularly valuable prize, since it controlled the air and sea lanes southward along the Australian coast. MacArthur decided not to wait for the Japanese to come to Australia, but to go north to meet them. With the forces allotted to the Southwest Pacific a good defensive position could be maintained, and it might even be possible to launch limited offensives.49

Role of the Engineers

In choosing to defend Australia in the islands to the north, MacArthur gave the engineers a decisive role. The battle would be joined on mountainous, jungled, rain-drenched islands, where overland movement and supply would be all but impossible. The airplane would be a principal weapon and heavy reliance would have to be placed on water transport. What MacArthur envisioned was a war in which airfields, ports, and bases would be the prerequisites of victory. Northern Australia had few facilities for waging modern war; New Guinea and the nearby islands had almost none. The engineers would have to build what was needed from the ground up and under the most difficult conditions. Construction would be their chief mission, but not their only one. Before Allied troops could advance, the engineers would have to provide maps of the uncharted, enemy-held regions. Once an offensive was launched, they would have to support the infantry in combat, help reduce enemy strongpoints, and perform many of their traditional functions in moving the army forward. Though MacArthur would employ the engineers in many ways, the effectiveness of his strategy would, in large measure, depend on the speed with which they could build bases and, above all, airfields from which fighters and bombers could strike at enemy targets.

That Casey would be chief engineer of SWPA had been a foregone conclusion, and on 19 April MacArthur issued the necessary orders. Having already had several weeks to study conditions in Australia, Casey was aware of the immense task ahead. As chief engineer of an Allied headquarters, he would coordinate the activities of all engineers, Australian and American, under MacArthur’s command, frame the policies under which they would work, and give them technical direction. To handle this assignment, he believed he would need a staff of at least 25 officers and men. But the number of officers in the theater was so scant that at first he could set up only a small section consisting of 5 officers and 5 enlisted men. Heiberg, transferred from Johns’s office, became his executive officer; Maj. Emil F. Klinke, transferred from the 43rd General Service Regiment, became chief of operations and training. Lacking experts in construction, Casey asked Reybold to send him Lt. Col. Bernard L. Robinson, then in Wyman’s office in Honolulu, and Leif J. Sverdrup, at that time about to

General Casey and General Sverdrup (photograph taken in 1944)

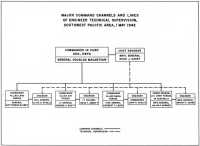

return to the United States in connection with work on the air ferry route and soon to be commissioned a colonel. Sverdrup and Robinson reached Australia in late May. Sverdrup became chief of the Construction Section and Robinson, assistant chief. Although his staff was part of an Allied headquarters, Casey had but one subordinate who was not American, an Australian major who served as liaison officer. He nevertheless intended to work closely with Maj. Gen. Clive S. Steele, who was both Engineer in Chief of the Royal Australian Engineers (RAE) and Engineer in Chief of the Allied Land Forces under General Blamey. Working with the Australians and integrating their engineer effort into the Allied program would require not a little tact and diplomacy, since the Commonwealth’s Department of Defence lay outside MacArthur’s jurisdiction.50 (Chart)

Chart: Major Command Channels and lines of engineer technical supervision, Southwest Pacific Area, 1 May 1942

At conferences held during the last weeks of April, Casey and Steele took stock of their resources. They had to assume that they would not have large numbers of American engineers at their disposal. One aviation battalion, 2 general service regiments, 2 separate battalions, and 2 dump truck companies would be in Australia by the end of April. Scheduled to arrive in May and June were 2 divisional combat battalions, 2 topographic units, and a depot company, the only additional engineer units approved by the War Department for SWPA at that time. This small contingent would hardly be sufficient for the tasks ahead, but fortunately, increasing numbers of Australian engineers were available. Units of the RAE were returning home with their divisions, and Steele had launched a strenuous recruiting drive. The engineers of the Australian Military Forces, while poorly trained and equipped, were receiving intensive instruction from veterans of the RAE. Steele expected soon to be in a position to furnish not only combat, construction, and supply units, but also all the camouflage and railway troops MacArthur needed. He was further prepared to supply the Americans with bridging, landing barges, barbed wire, and camouflage nets. Casey reasoned that water supply units from the United States could be dispensed with, since providing water would be difficult only in the parched deserts in the interior of Australia, and in his opinion the Allies did “not propose to have any operations there.” He did believe, however, that more troops trained in general and combat engineering must be sent from the United States. Urgently needed were an additional aviation battalion, 2 separate battalions, and 2 dump truck companies, a depot company, and a combat battalion, all fully equipped, and a heavy ponton battalion without its equipage. This was the absolute minimum but probably all that could be expected in view of the shortage of trained units in the United States, the lack of shipping, and the priority of operations planned for Europe. With a few reinforcements from the United States, Casey and Steele believed they could support the kind of strategy MacArthur had in mind. But engineer strength would have to be spread thin in the Southwest Pacific.51

While Casey drew long-range plans for the coming offensive, he had to supervise a construction program that was growing rapidly larger and more difficult of accomplishment. In announcing his strategy, MacArthur had indicated the need for prodigies of engineering in northern Australia and New Guinea. Port Moresby, northeastern Queensland, and Darwin were now areas of primary military importance. Greatest stress would have to be placed on developing Port Moresby, which MacArthur regarded as the key to the defense of Australia and the springboard for future offensives. Building an air and supply base in this exposed area would require much more than an ordinary engineer effort. Large numbers of men and

quantities of material and equipment needed to improve facilities in the town and to construct roads and airfields in the surrounding countryside would have to be sent in over supply lines that were vulnerable to enemy attack. If Moresby were to serve as the main air base for operations to the north, a string of supporting airfields would have to be constructed along the coast of northern Queensland. This, too, would be a formidable job, for little was known about terrain and soil conditions of the bush and jungles of the Cape York Peninsula. Darwin figured less prominently in MacArthur’s plans, but because the enemy might attack from the northwest and because the Allies might decide to invade the Indies, the hard work of building in remote Northern Territory would have to be continued and indeed stepped up. While emphasis was now on the north as never before, MacArthur could not neglect his flanks; western Australia would have to be provided with more airfields to guard against a Japanese thrust at that part of the continent. Moreover, logistical facilities in southern Australia would have to be expanded. MacArthur chose Sydney, the largest city and port of Australia, as the principal supply center for the American forces, rather than Melbourne, some 400 miles to the south. Thus, not only would a vast new program have to be undertaken, but the existing one would have to be continued.52 Only after base development was fairly well along would MacArthur be able to take the offensive.

Organizing the Engineer Effort

Since the war in the Southwest Pacific was clearly destined to be a “poor man’s war,” the engineers would have to make the most of what they had. As Casey saw it, they would have to build “what is wanted within the minimum time and with the minimum expenditure of manpower and material resources.” This ideal had not yet been attained. There was evidence of waste, duplication of effort, poor management, and inefficient administration. Too much was being done on “a peacetime basis of permanency.” Too many projects were long-term and would be of no help in furthering immediate military objectives and, “in addition, might seriously endanger other urgent military projects direly needed now.” Priorities were almost meaningless. In one case, a dressing room for women in a defense plant carried a higher priority than a hospital for the RAAF. It seemed that nearly every project of any importance was rated A-1. Although the shortage of equipment was acute, many contractors were not operating on a multiple shift basis. Agencies were duplicating each other’s work. In Queensland, the RAAF, the U.S. Air Forces, the Commonwealth government, and the engineers were all engaged in picking sites for airfields. Machinery for working with the Australians was slowed by red tape. It took the Allied Works Council an excessively long time not only to get approval to start a project but also to obtain permission

to make minor changes in specifications. Casey concluded that this state of affairs would force him to take a strong stand.53

One of his prime objectives was to give the program unified direction. He therefore set out to view construction in broad perspective, to consider projects not on an individual basis but as parts of an integrated program. As a first step toward this goal, he directed his staff to inventory jobs, under way and projected, and to make a survey of available manpower, materials, and equipment. He next attempted to formulate “a planned program of ... construction with definite time limits based on ... a knowledge of requirements and resources.” Once the program had been defined, he intended to keep close check on rates of progress and percentages of completion. He asked for uniform progress reports from each project, explaining that “the purpose is to see that the job is approximately up to date and if behind ... [what] action can be taken to bring it up to schedule.”54 Merely analyzing the program and diagnosing its ills were not enough. Casey would have to persuade others to follow his suggestions. Under the command-staff setup, he could not issue orders, but since he was MacArthur’s chief engineer, his recommendations would carry great weight.

He encountered resistance almost at once. The American airmen, not content to be dependent on the base sections, wished to handle their own construction. They were quick to cite examples of waste and inefficiency in the existing arrangement. To strengthen their position, they had already made a beginning toward setting up their own engineer establishment with the appointment on 6 March of Abbott as air engineer. After reminding Casey of the many difficulties the base sections had encountered in getting Air Forces projects finished on time, Brett on 18 April proposed that a separate field organization be created to handle the building of airfields. He asked that each air area commander be assigned an engineer who would be responsible to USAFIA for all Air Forces jobs in the area, selecting the sites and supervising the construction. Casey was unalterably opposed to such an arrangement. Not only would the authority of the air engineers conflict with that of the base section commanders, but this might well be the first step toward the establishment of a dual engineer organization with control of the aviation battalions exclusively by the Air Forces. Because the number of engineers in SWPA was so small, Casey believed that having two separate field systems would merely slow down progress. He countered Brett’s proposal with one of his own. What was needed, he suggested, was not another field organization but better coordination between the existing one and the Air

Forces. He persuaded Brett to let Johns assign engineers from the base sections to air commands in areas where extensive airfield construction was under way. These air engineers would act as liaison officers between the air areas and the base sections. They would also help select sites and inspect projects and could order minor changes in plans and specifications, but they would not be responsible for construction. Thus, Casey was able to forestall the setting up of a separate engineer organization under the Air Forces.55

Casey had no sooner come to an understanding with Brett than he found himself at odds with the RAAF. Although this organization was engaged in an extensive construction program, Casey was unable to get a list of its projects. Nor was the RAAF inclined to tell him how many fields it planned to build or what its overall requirements would be. He learned indirectly that it was concentrating heavily on the southeast and was planning to work on some eighty fields in the Sydney area alone. While these matters were not, strictly speaking, his affair, Casey believed that the concentration of so much effort in the southeast was detrimental to Allied strategy. He prepared a memorandum for Brett, indicating that there was not “complete coordination,” between the American and Australian air forces. He expressed the belief that it was “desirable that the broad picture of Allied Air Force construction requirements be pulled together into an all-embracing program.” He went on to say that if “we are to be forced back into the southeastern Australian area, an extensive construction program in that area is undoubtedly wanted” but implied that if MacArthur’s strategy were sound, many of the southern projects could be dropped. While this memo was still on his desk, Casey received a letter from General Steele of the RAE, telling him of the RAAF’s plan to organize four works units for building airfields, each unit to consist of 1,000 men and to be equipped with heavy machinery. “I feel a little diffident,” Steele wrote, “but in view of [the] manpower shortage feel that I should ... [suggest] that their establishment seems somewhat top-heavy.” Casey had additional grounds for objecting—the works units would probably be used exclusively on RAAF projects. He quickly drafted a second memo to Brett in which he recommended that smaller units, modeled on U.S. engineer aviation companies, be formed and placed under Steele. Taking both memos, he set off for the headquarters of the AAF. Brett glanced over the documents and passed them on to his chief of staff, Australian Air Vice-Marshal William D. Bostock.56

Two days later Bostock held a meeting of air officers and engineers. Casey, away on a field inspection trip, could not attend. Among those present were Lt. Col. Ward T. Abbott, Col. E. S. Bres of Johns’ office, and 1st Lt. Max D. Lovett

of Casey’s staff. A rather heated discussion developed. Bostock opened the conference with the statement that he thought a great many of Casey’s misgivings about the RAAF’s construction program were the result of “incomplete information” and suggested that the chief engineer possibly had not “had an opportunity of thoroughly dealing with ... [the] problem.” Bostock was not inclined to discuss the question of how RAAF works units should be organized. This, he said “was the concern of the Australian Government and a matter for the Ministry of Air to decide. ... It was not a question for Allied Air Forces to worry about.” Remarking that Casey seemed “somewhat worried” over the amount of construction going on in the southeast, Bostock stated that manpower and materials available there could not always be sent elsewhere. On the island of Tasmania, for example, there were plenty of laborers ready to work at home but unwilling to go to New Guinea. When Colonel Abbott asked if the equipment in Tasmania could not be sent north, Bostock retorted that that was a matter for the Allied Works Council. As Colonel Heiberg put it later, the “general attitude ... seemed to be that works are now progressing satisfactorily, and no external control is desired or necessary.” The RAAF nevertheless agreed to make one concession; it would furnish a statement of its airfield program to Brett.57

Even as he attempted to coordinate construction work and to centralize responsibility, Casey, together with other engineers, favored the policy of giving more authority to the field. In the early days the men directly in charge of projects had had little leeway. Approval for even the most trifling jobs had to come from Melbourne. The granting of more power to the base section commanders had been advocated for some time. On 26 March Brett had ruled that jobs costing less than £1,000 (about $3,200) could be undertaken by base section commanders on their own authority. On 3 April he raised the ceiling to £5,000 (about $16,000). Since the vast majority of projects were to cost less than this sum, Brett thus decentralized his authority over most of the program. Many engineers believed that Theodore would have to follow suit. Contractors were having to get the AWC’s approval for practically everything they did. When Colonel Matthews tried to stop certain work he considered unnecessary at Charters Towers and Cloncurry, the contractor refused to quit, saying that he took “his orders from Brisbane.” Both Casey and Steele proposed that the AWC send to the projects representatives clothed with authority comparable to that of the base section commanders. Then, if Matthews wanted a few buildings more or less at Charters Towers, he could get approval directly from the AWC’s man at the site. Theodore at first objected, maintaining that a telephone call to him would bring action within twenty-four hours. To this Steele replied that “he was interested in a method of operation that can go on in the event a bomb should cut the telephone lines.” Finally Theodore agreed

to send out men empowered to make on-the-spot decisions. Soon “coordinating engineers” were on their way to many of the large projects with orders to remove bottlenecks and improve efficiency.58

Minimum Construction Requirements

It was difficult to escape the conclusion that much of the construction was overelaborate and some of it unnecessary. On the road from Townsville to Charters Towers Casey observed workmen putting in a heavy type of culvert, better suited for a permanent peacetime highway than for a temporary military supply route. He learned that the RAAF was planning to build an officers’ club costing $100,000 at Darwin. There were many projects which would not be finished for years but would benefit the Australian economy after the war. Insisting that construction be held to “bare essentials,” Casey suggested that long-term projects be deferred. “The tactical situation might materially alter ...,” he pointed out, and works which will not be completed for say a year or more hence will be of no value insofar as near term operations are concerned.” Many of the AWC officials agreed with him. They too wished to avoid “spit and polish” construction and to eliminate jobs which would not contribute to the winning of the war. But paring down to essentials was no easy matter. Many commanders, American and Australian, were interested in building elaborate installations for themselves and in promoting their own pet projects. Many jobs had been started before Japan declared war, and supplies and materials had already been allocated. Yet the situation was not quite so hopeless as it appeared. Officials of the AWC through their control of manpower, materials, and equipment could do much to correct abuses, and Casey kept up unremitting pressure to make them do so.59

The chief engineer saw still another opportunity to economize. Believing an enemy landing imminent, the Australians were making frantic preparations in the southeast to hold back the invader and, failing that, to destroy everything in his path. Around Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, large numbers of men were mining roads and bridges, digging trenches, preparing tank traps, and making ready to put a scorched-earth policy into effect. Undoubtedly much of this work could be suspended. Fixed positions would be of little value since the enemy could easily bypass most