Chapter V: First Offensives: The Solomons and Papua

The war in the Pacific had reached a critical juncture by the summer of Rip. A still formidable enemy threatened the line of communication between Australia and the United States. The Japanese had suffered two reverses at sea, but they remained undefeated on land and in the air. Their invasion of Papua and their advance through the Solomons, if unchecked, might yet develop into a major setback for the defenders in the South and Southwest Pacific. By launching a limited offensive, the Allies hoped to halt the Japanese and begin pushing them back on a broad front stretching across New Guinea and extending eastward for hundreds of miles. While containing the enemy, the Allies would gather strength for future large-scale assaults against the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul. The task of carrying out a stopgap offensive while continuing to prepare for an all-out drive would fall with special weight on the engineers, who would have to support the combat forces in the field and at the same time build the bases from which future sustained offensives could be launched.

Strengthening the South Pacific

The South Pacific was hardly less important in the Allied strategy than Australia itself. Through this immense ocean area ran the lines of communication from the United States to the southern continent—lines which would have to be kept open. The South Pacific could do little in its own defense. The widely scattered and more or less isolated islands of the region had, for the most part, sparse populations, primitive industries, and few natural resources. Only New Zealand had a modern industrial system, but with a population of some 1,600,000 and limited resources, that dominion was unable to make substantial contributions to the defense of the area. Having sent one division to the Near East in 1941, New Zealand had few troops left for home defense, and of these one brigade had already been dispatched to Fiji. Australia had agreed to reinforce New Caledonia, but was able to send only one company of troops to the island. In the first weeks after the outbreak of war with Japan, the strengthening of the South Pacific was not immediately urgent. That area did not appear so directly threatened as Australia was. Insofar as the United States was concerned, primary responsibility for defense of the region rested with the Navy. Only with the fall of the East Indies and the emergence of Australia as a great Allied base did the South Pacific become of vital interest to the Army.1

The South Pacific Ferry Route

The engineers, at work on the ferry route when war began, were the first American troops in the South Pacific. At the time of Pearl Harbor, engineer officers were reporting good progress on the airfields. On Christmas and Canton, troops and civilian workmen were clearing and grading runways. On Fiji, natives were lengthening the airstrips, and New Zealand was sending in more men, materials, and equipment. On New Caledonia, the Free French were making headway on the fields at Tontouta and Plaines des Gaiacs. Just before the attack on Pearl Harbor, General Short had assured Washington that the route would be open by 15 January. Events of the following weeks rendered completion more urgent than ever. Heavy bombers were desperately needed to stem the Japanese tide in the Philippines. The Central Pacific route through Midway and Wake was lost in the first days of the war. The only alternate besides that through the South Pacific was the long, roundabout way across the Atlantic, Africa, and the Indian Ocean—two-thirds of the distance around the globe.2

In Hawaii Colonel Wyman ordered work on the ferry route pushed with all possible speed. In carrying out his instructions, the engineers in the South Pacific islands were confronted with mounting difficulties. The islands were almost completely isolated. Peacetime sailing schedules were disrupted, and there were few vessels to carry cargo to the South Pacific. Even the project’s A–i–a priority was of little help. Wyman complained that, while he assumed the rating to be in effect, it had proven virtually useless for getting materials and equipment to places where they were needed. Shipping was not to be had for the stocks piled up in the San Francisco port. On Christmas and Canton even supplies of food and water ran low. Poor communications complicated matters.3 “[The] greatest obstacle ... toward the proper direction of the jobs down here,” one of the civilian employees on the ferry route wrote Wyman from New Caledonia, “is the lack of communication whereby detailed information can be transmitted between jobs. Cables and radios are fine, but you cannot say enough, and we always have a certain amount of garbling which sometimes is not recognized as such.”4 General Short’s efforts to get a Navy or Pan American plane to fly couriers back and forth among the Pacific islands were unavailing, as were those of his successor, Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons, who assumed command of the Hawaiian Department on 17 December. The situation was alleviated to some extent when Wyman

obtained a yacht and put it into service early in January.

The enemy’s swift advance toward the South Pacific greatly increased the tension under which work had to be carried on. The islands were practically defenseless. Initially the small detachments of engineers on Canton and Christmas had been equipped only with carbines, rifles, and a few machine guns. Late in November, Short had sent to Christmas two 75-mm. guns with 800 rounds of ammunition and a sergeant to train men from the 804th Aviation Battalion as artillerymen. Neither the New Zealanders on Fiji nor the Australians on New Caledonia had any illusions about their ability to hold the islands against determined assaults. On Fiji, the New Zealand troops were expending great efforts fortifying the capital city of Suva, meanwhile leaving the airfields on the opposite side of the island extremely vulnerable to attack. So weak were the forces on New Caledonia that preparation even of minimal defenses was out of the question.5

There was near panic on Christmas. When news of the attack on Pearl Harbor reached the island, fantastic rumors began to spread. Three days after the outbreak of war, reports were circulating that a Japanese submarine was based on the shores of the lagoon. The general consternation heightened when an engineer officer was quoted as having told workmen that they would all end up before a Japanese firing squad. Many of the civilians began clamoring for passage to Honolulu. On 19 December Major Shield, the engineer officer in charge, put Christmas Island under martial law, declaring that no one would be permitted to leave. He ordered the men to work seven days a week, with no time off. In an effort to keep work moving, he endeavored personally to run the Hawaiian Constructors’ organization, which had been hastily pulled together and was not functioning well. Displaying what appeared to be little respect for the company’s foremen, he countermanded their orders so frequently that the men did not know whose instructions to follow. In the words of one of the supervisors, “orders were given indiscriminately to anyone and everyone.” The Hawaiian Constructors became less a contracting organization than a gang of hired laborers. When the War Department imposed radio silence on the island and deliveries of mail were delayed, discontent increased. The men promptly blamed Shield for their inability to get in touch with their families. The military as well as the civilians were becoming more and more difficult to deal with. A lieutenant from Wyman’s office, inspecting the island in mid-December, noted a “complete lack of cooperation” between Shield and the officers and men of the 804th. Work proceeded, but at a very slow pace.6

A calmer atmosphere prevailed on Canton and Fiji, although these islands were more directly in the enemy’s path. Convinced that Canton could not be successfully

defended, General Short ordered the civilians evacuated. On 14 December the ship to take them off the island arrived, bringing with it ten artillerymen, two 75s, and a dozen machine guns. After the civilians departed, the engineer troops, under Captain Baker’s direction, continued work on the airfield, and not without success, since they had plenty of equipment for what they were trying to do. On Fiji, natives, helped by increasing numbers of skilled workmen from New Zealand, continued improving and enlarging Nandi Field. Urged by Short to strengthen the garrison and to step up construction of the airfield, New Zealand replied on 20 December that additional reinforcements were being rushed to the Crown Colony. Within a short time thereafter, the Dominion had 3 infantry battalions on Fiji and had increased the number of skilled workmen to 1,200.7

New Caledonia, the most westerly island of the route in the South Pacific, was almost completely cut off from Wyman’s office. On 7 December the engineers were represented on the island by Lieutenant Sauer. He was shortly joined by Captain MacCasland, who henceforth served as area engineer. As the. only American officers in the French colony, their responsibilities were heavy. When Pan American Airways evacuated its employees soon after hostilities began, MacCasland and Sauer took over the company’s property and kept the important seaplane base in operation. When an outbreak of bubonic plague on New Caledonia prevented the firm of Sverdrup and Parcel from sending in civilian engineers and draftsmen from the States, the officers in New Caledonia undertook to do the work of the architect-engineers. When Rear Adm. Thierry d’Argenlieu, the new Free French High Commissioner for the Pacific, announced that he would negotiate only with representatives of the U.S. Army with regard to the airfield program, the engineers had to take a turn at diplomacy. The French were most cooperative. They diverted the bulk of their scant stock of dilapidated equipment to airfield work and hired every man who could be recruited in New Caledonia and nearby islands, even going as far afield as Australia to get skilled labor. The New Caledonia Bureau of Public Works assumed the complicated task of administering a motley force of some 400 men at work on the airfields—Frenchmen, Australians, Javanese, Tonkinese, Indochinese, and Kanakas. Efforts centered on Tontouta. Though the engineers knew this field was poorly located and part of it would probably be under water during the rainy season, construction there was considerably further along than at Plaines des Gaiacs. The outbreak of war rendered imperative the completion of an emergency runway that could serve until Plaines des Gaiacs was ready. Urged on by MacCasland and Sauer, the French set themselves the task of finishing Tontouta before the deadline of 15 January.8

On 28 December Wyman announced

that the South Pacific ferry route was open. Canton, Tontouta, and Nandi were far enough along to take heavy bombers. Runways were 5,000 feet in length at the first two fields, 4,200 at the third. On 12 January the first flight of B-17’s completed its trip over the route, landing at Canton, Nandi, Tontouta, and Townsville. The pilots pronounced the runways excellent. The strip at Christmas, which lagged behind the rest, was reported ready on 20 January, and the next day a flight of B-17’s landed there. From this time on, increasing numbers of planes flew over the route. The work of providing adequate gasoline storage and other facilities still remained to be done. There remained, too, the problem of defense.9

Arrival of Task Forces

By late December top-ranking Allied strategists were considering means of reinforcing the South Pacific. The danger here had become apparent a few weeks after Pearl Harbor, when the Japanese occupied the Gilbert Islands. At the ARCADIA Conference, the Americans voiced fears that Australia might be isolated, while the British expressed apprehension over the growing threat to New Zealand as well. The Americans promised to strengthen Canton and Christmas and to aid New Caledonia and Fiji if it appeared that Australia and New Zealand could not adequately protect those islands. Steps were soon under way to send 2,000 men to Christmas, 1,500 to Canton, and a pursuit group (700 men) to Fiji. New Caledonia also stood in need of reinforcements, but Australia could spare nothing more for the island. Reports had reached Washington that Admiral D’Argenlieu was threatening to stop work on Plaines des Gaiacs unless more troops and weapons were forthcoming. The War Department assembled a task force of some 16,000 men under Brig. Gen. Alexander M. Patch for shipment to New Caledonia late in January.10

Reinforcements reached Christmas and Canton in February. On the loth, a task force under Col. Paul W. Rutledge landed at Christmas, and three days later another under Col. Herbert D. Gibson arrived at Canton. Soon after going ashore, Colonel Rutledge inspected the air base and was shocked by what he found. There was bickering among the engineer officers and “much friction” between Shield and the workmen. So complete was the demoralization of the civilians that, in Rutledge’s opinion, they could not be expected to accomplish anything worthwhile. One runway was completed and another half-finished, but there was “no evidence of any other satisfactory work.” Indications of inept planning and weak administration were numerous. Building materials were strewn around and equipment was rusting. Sanitary conditions were intolerable; garbage and filth littered the

camp area and formed breeding grounds for swarms of flies. Rutledge asked Emmons to relieve Shield immediately. The situation on Canton, while not so bad as on Christmas, left room for considerable improvement. Colonel Gibson found that much construction remained to be done, that morale was low, and that living conditions were deplorable.

Steps were shortly taken to set matters right on the islands. The disgruntled civilians on Christmas were returned to Honolulu. Shield and Baker were replaced. Both officers had had difficult assignments, starting out as they had with pioneer expeditions to build on remote and undefended islands.11 Colonel Wyman supported both officers, stating that he found little fault with their performance. They had, he maintained, “accomplished their missions ... with remarkable speed” and in accordance with directions.12 Nevertheless, conditions improved noticeably after the construction forces on the islands were placed under the task force commanders.13

Meanwhile, on New Caledonia, Sauer, who succeeded MacCasland as area engineer in January, was making strenuous efforts to get Plaines des Gaiacs finished. Upon completion of the emergency strip at Tontouta, he transferred every available man and piece of equipment to the new project. He received an unlooked for addition to his slender labor force when the 125 civilians taken off Canton unexpectedly appeared at Noumea on to January and 100 remained. These men built a camp at Plaines des Gaiacs, while the French, who insisted on retaining direct supervision of their workers, concentrated on the runways. Initial specifications had called for strips of asphaltic concrete, but since there was now small chance of importing this material into New Caledonia, a substitute had to be found. About four miles from the field was a bed of gravel composed of about 50 percent iron ore. The gravel proved to be satisfactory for surfacing. The French made rapid progress; one reason, undoubtedly, being their method of working. It consisted in placing the surfacing material on the ground with little if any grading and no compaction of the soil. As a result, the runways, from which roots and snags protruded, had many bumps and dips. But the iron ore made an exceptionally hard surface, and planes were able to land. On 15 February one strip was complete and two days later the first heavy bomber put down at Plaines des Gaiacs. Work on a second runway began immediately.14

The first ships carrying General Patch’s task force steamed into Noumea harbor on 12 March. Only days before, the Japanese had established a foothold in the northern Solomons, and New Caledonia now appeared to be directly in the enemy’s path. Patch’s tersely worded orders read, “Hold New Caledonia

Noumea, New Caledonia

against attack.” Making plans for carrying out this directive was the first order of business for the task force commander, his engineer, Col. Joseph D. Arthur, Jr., and other members of his staff. It was obvious that 16,000 men could not garrison the whole island. A mobile defense would have to be ruled out until communications were improved. Almost all of New Caledonia was mountainous. There was but one main highway, a narrow, twisting road running parallel to the western shore line. The only railroad, a line extending a short distance northward from the capital, had been abandoned in 1940. Noumea was the one port worth mentioning. In the

light of these conditions, Patch concluded that he must first of all protect Noumea. That being the case, the Allied forces could not be stretched to Plaines des Gaiacs, 158 miles away. Patch therefore selected Tontouta as the principal airfield for defense. The work of maintaining Tontouta and completing Plaines des Gaiacs could for a time be left to Sauer. Patch’s engineers must at once begin improving the island’s system of communications.15

Three engineer units had come with the task force, the 57th Combat Battalion, commanded by Maj. George H. Lenox, and two aviation battalions, the 8 loth, commanded by Maj. R. P. Burt, Jr., and the 811th, under Maj. Charles H. McNutt. Except for a detachment of the 57th which remained near Noumea to rehabilitate the railway, all engineers were put to work on roads. Most were assigned to the coastal highway, which was crumbling under heavy traffic. By early April the engineers were fully occupied in patching and widening this main artery. Though the bulk of their equipment had yet to arrive, the men built several new sections of road. One such project was a detour, eighteen miles long, around a mountain pass, at a place where a direct hit would have isolated the northern half of the island. But even with these improvements, the road was inadequate. Moving heavy construction machinery up to the airfields was no easy feat, as the engineers learned when most of their equipment finally reached New Caledonia in April. To eliminate the need for trucking all supplies from Noumea, Colonel Arthur started construction of piers near Tontouta and Plaines des Gaiacs.16

Dispatching engineer troops to the airfields could not be long deferred. Under heavy use, the emergency strip at Tontouta was beginning to break up. A second runway completed by the Australians on 17 March was too short for heavy bombers to use safely. Plaines des Gaiacs was operational but needed much more work. In April, General Patch began giving special attention to the fields. He ordered one company of the 811th Battalion to Tontouta to repair the runway and build dispersals, which pilots who had been in the Philippine and Java campaigns insisted were necessary. Construction of a pursuit field at Bourake, a short distance north of Tontouta, was undertaken by another company of the 811th. Since the site had good natural drainage, sandy soil, and only scrub vegetation, the task was comparatively easy. In eight days the men were able to clear a 3,000-foot runway. The job at Plaines des Gaiacs was gaining momentum. The Australian crew. their work at Tontouta done, moved with a considerable stock of equipment to this project late in March. On 24 April the entire 8 oth went to Plaines des Gaiacs and began operations on a three-shift basis. On to May, Major Burt assumed direction of all work. When Sauer relinquished control of the project to the commander of the 8 loth, a second runway was usable, dispersals were almost complete, thirteen miles of access roads were in, and housing and utilities were well along. The job of the Sloth was to lengthen the runways, install gasoline storage, provide lighting, and maintain a base from which heavy bombers could attack enemy forces moving south.17

The danger to the South Pacific line of communications was becoming acute. On 3 May the Japanese occupied Tulagi, an island of the southern Solomons, some Boo miles north of New Caledonia, just as their task force at Rabaul was preparing to leave for Port Moresby. Shortly after the Battle of the Coral Sea, the enemy prepared to strike again as a mighty task force assembled in home waters. The islands of the South Pacific seemed a probable objective. Among the most likely targets were the ferry bases. Although the islands had been reinforced, their defenses were still pitifully weak, and reports from the bases were uniformly pessimistic. After inspecting the three easternmost islands in April, Maj. Robert J. Fleming, Jr., of Emmon’s G-4 section, confirmed the findings of earlier official visitors. Although he observed that the engineers were making good progress toward completing facilities, he considered the efforts to strengthen the islands against attack largely ineffectual. Needed were ammunition, guns, barbed wire, and, above all, troops. Even camouflage was lacking. The installations on Christmas could be clearly seen from the air, and the acres of brilliant red drums used for storing gasoline on Canton were visible for many miles. Weakly fortified and lightly held, the islands of the ferry route, except possibly New Caledonia, could have been taken with very little effort.18

The Alternate Ferry Route

As early as January, Wyman had anticipated the need for a second ferry route—one less in danger of being overrun. On the 25th, he had recommended to General Emmons that a series of airfields be developed in the Marquesas, Society, and Tonga Islands. Late in February, after receiving permission from Washington, Emmons ordered a survey of the proposed route. Wyman picked Sverdrup, at that time still working as a civilian on the ferry route, as the man for the job, and recalled him from Suva to Honolulu for instructions. The district engineer wished to make sure that lessons learned on the first route would be taken into account and that the peculiarities of the weather in the region would be considered.19 Experiences on Christmas and Canton had demonstrated that American workmen were “not temperamentally suited for construction work on these islands, largely due to the foreign environment, danger of enemy action, and the confinement in a small area without ... amusement and recreation.”20 Wyman insisted that Sverdrup select islands “with a native population engaged in agriculture or mining.”21 Because the unloading of supplies at Christmas and Canton had been complicated by reefs and shoals, he also instructed Sverdrup to find good natural harbors or lagoons.

The violent storms that swept the area just south of the equator would present an added problem. Since the many low atolls of the region were frequently awash in rough weather, Sverdrup was cautioned to pay particular attention to elevation. Early in March, after signing a contract with the Honolulu District, Sverdrup boarded a Navy plane for Tahiti to begin his reconnaissance.22

During the latter part of March, he visited some thirteen islands and found a number of good sites. One was on Penrhyn, a possession of New Zealand, 770 miles south of Christmas. Most of this atoll was awash during high seas, as only one of the many islets was more than two feet above sea level. But this one, 4 miles long arid a quarter mile wide, offered ample room for a runway, and planes could be dispersed under the numerous coconut trees. All the land was native owned. It was passed down from generation to generation within the family and for a native to dispose of any was illegal. The local representative of New Zealand assured Sverdrup that he did not believe there would be any trouble in arranging for its use. He also estimated that at least 75 of the 500 natives could probably be recruited for work on the runway. Some 800 miles south of Penrhyn, Sverdrup found another promising site on Aitutaki, an island in the Middle Cook Group, also a possession of New Zealand. Of volcanic origin, Aitutaki was rugged, but there was one fairly flat area where two runways could be readily graded and compacted. With a population of 2,000, the island could provide all the common labor needed. The Government of New Zealand would undoubtedly be able to send in a few skilled equipment operators. About 1,000 miles to the southwest, Sverdrup found a third desirable site on Tongatabu in the Tonga group, a protectorate of Great Britain that he had visited before in the fall of 1941. Tongatabu had one great advantage—it already had an airfield. Sverdrup believed little effort would be required to develop three 6,000-foot runways. On 1 April he sent word to the Honolulu District that Penrhyn, Nitutaki, and Tongatabu met Wyman’s specifications. Shortly thereafter Emmons informed Washington that an alternate ferry route was feasible. On 11 May authority was given to go ahead with construction.23

Further Strengthening of the South Pacific

While the Army had been reluctant to commit itself heavily in the South Pacific during the first months of 1942, the Navy had strongly urged a build-up of forces there. Admiral Ernest J. King, who in March became Chief of Naval Operations, wanted to garrison additional islands, especially Efate in the New Hebrides, an archipelago to the

north of New Caledonia, and Tongatabu. General Marshall was at first hesitant to adopt King’s views but finally agreed to go along with them. The Joint Chiefs in May issued two basic plans: one for the occupation and defense of Tongatabu and another for Efate. Tongatabu was to be primarily a Naval base, while Efate was first to be an “outpost for supporting both New Caledonia and Fiji and later was to serve as a minor advance air and naval base for future offensive operations.” On 17 March General Patch, following instructions from Marshall, sent a battalion of infantry and a platoon of the 57th engineers to Efate. A small beginning had been made toward strengthening the New Hebrides.24

With the formal delimitation of the Pacific theaters on 30 March, responsibility for the South Pacific was more sharply defined. The Pacific Ocean Area was divided into three subordinate areas—the North, Central, and South Pacific. The first included all the region above 42 degrees north. The second was bounded by the 42nd parallel and the equator. The third took in the area south of the equator, west of longitude 110 degrees west, and east of the Southwest Pacific Area. Except for the forces responsible for the land defense of New Zealand, which were controlled by the New Zealand Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Nimitz was commander in chief of all Allied forces in POA. His missions were similar to MacArthur’s. The two commanders were to hold the lines of communications between the United States and Australia, contain the enemy in the western Pacific, and prepare for major amphibious offensives. Each was to support his neighbor’s undertakings. Nimitz was to command the Central and North Pacific Areas directly but was to appoint a subordinate to command the South Pacific. In April he selected Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley for the post.25

Strenuous efforts were made to strengthen the New Hebrides. On 8 April the small force of infantry and engineers on Efate was joined by a marine defense battalion. Sauer, now a captain, going to the island later that month to line up sites for airfields, found that the engineers, the marines, and some 200 natives had already cleared 2,000 feet for a fighter strip and had begun the arduous task of providing roads. Most of the island was a jungle wilderness. The only roads to speak of were the 15-odd miles of track near the town of Vila. In order to penetrate into the interior, even on the existing trails, it was necessary to have native cutting parties out in front.26 “[The] ... roads,” wrote one engineer who explored the island by jeep in May, “[were] ... absolutely the worst in the world—it took us 2½ hours to go about 10 miles. ...”27 On 4 May, the day after the

enemy moved into Tulagi, the Efate Task Force arrived from the States, bringing with it Company B of the 116th Engineer Combat Battalion and two companies of Seabees. The newcomers at once buckled down to extend the airstrip to 6,000 feet. With the Japanese about 700 miles to the northwest, pressure for completion of a runway for bombers was intense. By prodigious efforts, the engineers, seabees, marines, and natives completed the field on 28 May. That same day, a small party of infantry and engineers moved 200 miles northwest to Espiritu Santo, the largest island of the group, where extensive defense works would soon be needed.28

Efforts to bolster other islands of the South Pacific were intensified. In May the 37th Infantry Division, then being readied for shipment to New Zealand, was ordered to Fiji instead. The unit, which included the 117th Engineer Combat Battalion, reached its destination in June. Later that month steps were taken to enlarge an old French runway at Koumac, near the northern tip of New Caledonia, to enable it to take heavy bombers. The 810th engineers, assisted by Australian workmen, had the field operational by the end of the month. Construction of the alternate ferry route got under way when natives began clearing runway sites on Aitutaki and Tongatabu in June and on Penrhyn in July. The construction program on Fiji received a boost on 8 July with the landing of 687 officers and men of the 821st Aviation Battalion. Work commenced the same day on an airfield at Espiritu Santo. The men on this project were involved in a race against Japanese construction forces who had only recently begun building an airfield on the northern shore of Guadalcanal in the Solomons, within easy bombing distance of the advanced Allied bases.29

By June problems of administration and supply had assumed formidable proportions. A well-knit Army organization had yet to be evolved. Each base handled its own affairs. The War Department, the San Francisco Port of Embarkation, the Hawaiian Department, and USAFIA all had a part in supplying the area. Local procurement was not regulated in any way. When Ghormley took command of the South Pacific Area on 19 June, one of his first acts was to set up the Joint Purchasing Board at Wellington, New Zealand. Composed of three officers, representing the Army, the Navy, and the Marine Corps, the board was to control the procurement of all supplies except those obtained from the United States. The War Department was also taking steps to rectify the situation. On 25 June Emmons was relieved of responsibility for directing and supplying Army forces in the South Pacific, except those working on the alternate ferry route. The War Department would henceforth administer the Army forces in the South Pacific, while

the San Francisco Port of Embarkation and the Joint Purchasing Board would see to their supply.30

Preparations for the Offensive

Admiral Ghormley had no sooner set up his headquarters at Noumea than he was plunged into preparations for the coming offensive. With the Japanese making frantic efforts to complete the airstrip on Guadalcanal, it appeared that another, perhaps final, blow would soon be directed at the South Pacific. In their directive for the offensive issued on 2 July, the Joint Chiefs of Staff took cognizance of the acute danger. They combined the plans of Nimitz and Ghormley for a campaign in the southern Solomons with those of MacArthur for an offensive against Rabaul. The joint operation was to be carried out in three phases: first, the taking of Tulagi and adjacent islands; second, the seizure of the northern Solomons, northeastern New Guinea, and western New Britain; and third, the capture of Rabaul. Ghormley was to command the first phase; MacArthur, the second and third. The target date for the invasion of Tulagi was 1 August.31

The imminence of the campaign in the Solomons led the War Department to establish an over-all command, United States Army Forces in the South Pacific (USAFISPA)—with Maj. Gen. Millard F. Harmon in command. As Ghormley’s subordinate, he was to have direct responsibility for administering and supplying the 52,000 Army troops now in the area and, although he was to have no part in directing tactical operations, he was to make plans for employing Army units in combat. On 21 July Harmon left the United States, accompanied by members of his staff, including his engineer, Col. Frank I,. Beadle. Eight days later, the party arrived in Noumea. Six engineer units had preceded Beadle to the South Pacific—three aviation battalions, two combat battalions, and one combat company, about 3,500 men in all. There was little Beadle could do in the way of building an effective engineer organization or planning for the coming campaign, now only a few days away.32

On 7 August the marines landed on the northern coast of Guadalcanal near the airfield. The landing apparently caught the enemy by surprise. The next day the field was in American hands. In the course of violent sea, land, and air battles in the ensuing weeks, the Americans not only held but expanded their positions. But the advance was slow. Guadalcanal was well suited for defensive warfare, and the Japanese poured in reinforcements. The marines, in their efforts to compress the enemy into the northwestern tip of the island, were to have months of fighting ahead of them. While Marine engineers and Navy construction battalions had initial missions on the island, Army engineers contributed by helping with the development

Map 9: Papua

of bases and airfields on islands to the rear. Since the Marine Corps and Navy carried full responsibility for fighting the Japanese on Guadalcanal during the first two months of combat on that island, the story of the engineers in the first offensives in the South and Southwest Pacific is largely one of their operations in New Guinea.

Preparing To Fight in New Guinea

When the marines landed on Guadalcanal, the enemy forces in New Guinea advancing along the Kokoda Trail had reached Isurava, sixty miles from Port Moresby. (Map 9) Intercepts of radio messages indicated the Japanese were planning to land troops on the island of Samarai, at the mouth of Milne Bay. From this vantage point, the enemy could control the waters near the southeast tip of New Guinea and would be in a better position to strike along the island’s southern coast. Early in August, MacArthur moved to meet the growing danger. In order to have a unified command in the combat area, he placed all

Allied troops in Australian New Guinea under New Guinea Force, henceforth commanded by Australian Maj. Gen. Sydney F. Rowell. Rowell was given a large assignment. He was to stop the enemy advance toward Port Moresby, recapture Kokoda and Buna, and eventually drive the Japanese from Salamaua and Lae. The 7th Australian Division was being readied in Australia for movement forward; advance elements were already on their way. MacArthur placed one limitation on Rowell’s authority: While he had complete command over combat forces, he was to exercise no control over American service troops engaged in base construction unless an attack was under way or imminent.33

The sending of so much Allied strength to the forward areas increased enormously the task of the engineers. Though base development had come a long way, much remained to be done. Of the seven fields planned for Moresby, two all-weather airfields and two dry-weather strips were operational. They could not accommodate the great numbers of planes that would have to operate continuously against the advancing enemy. The sole deep-water dock of the city’s harbor was so inadequate that only one vessel could discharge cargo at a time. Key installations, some of them many miles inland, were connected to the port by dirt roads. Milne Bay, with its single operational airstrip and its primitive piers and jetties, could not serve as an adequate base for strikes to the north.34

With an ever-growing construction program in prospect, a better organization of the Engineer effort in New Guinea was imperative. Visiting Port Moresby early in August, Colonel Sverdrup, now head of construction in Casey’s office, concluded that “all construction work under US supervision should be reorganized from top to bottom.” Believing that engineer output could be stepped up 30 percent if the work were properly organized and directed, he recommended that a “senior officer well qualified in construction and planning” be sent to the New Guinea port at once.35 Sverdrup was not alone in this opinion. GHQ SWPA was already preparing plans to set up a more adequate supply and construction organization in New Guinea. On I i August General Richard Marshall, the commanding general of USASOS, established U.S. Advanced Base at Port Moresby.36 Naming Matthews base commander, Marshall made him responsible for construction and supply for American forces in the Port Moresby and Milne Bay areas. The next day Matthews arrived by plane at his new headquarters, and was hardly settled before an avalanche of demands descended on him. General Kenney was calling for two additional fields at Moresby to bring the total number there to nine; at Milne Bay he wanted not two but three strips, and by late August, he was asking for the construction of 227 revetments at Moresby alone. Meanwhile, USASOS could not

ignore the fact that, in view of the shortage of ships in the theater, the ports at Moresby and Milne Bay would have to be enlarged to permit faster unloading and quicker turn around. These demands were only the beginning of many additional requirements the engineers would have to meet. Taking stock of his resources—the few engineer troops and the meager stocks of supplies and equipment—and viewing the task ahead, Matthews could only conclude that the job would not be completed before November and that it could be finished by then only with “weather permitting and God helping.”37

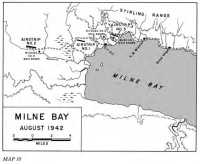

Battle of Milne Bay

While preparations for the offensive were going ahead in Papua, the enemy struck again. Having learned in mid-August of the airfields at the head of Milne Bay, the Japanese decided to land there rather than on Samarai. On the morning of 25 August reports reached the forces at the bay that nine enemy ships were approaching. Three engineer companies—D and F of the 43rd and E of the 46th—were in the threatened area, battling mud and almost incessant rains to complete the airstrips. (Map 10) All of Company F and part of D were working on Strip No. 3, recently begun at the northwest tip of the bay. They had just finished clearing a site 6,000 feet long and 300 feet wide. Three miles to the west, detachments of Company D were working on Strip No. 1, which, despite its poor foundation, was being regularly used by planes. Company E of the 46th was preparing Strip No. 2, some four miles southwest of No. 1 and five miles from the bay. There were 9,458 Allied troops in the area—the Americans, including the engineers and an airborne antiaircraft battery, numbered 1,365; Australian strength totaled 8,093. On 22 August, Australian Maj. Gen. Cyril A. Clowes had assumed command of all forces at Milne Bay. The engineers and antiaircraft gunners of Clowes’ command were to be the first American ground troops to meet the Japanese in combat in New Guinea.38

On learning of the enemy’s approach, General Clowes began at once to deploy his forces. The Australian infantrymen were readied, and the RAAF pilots at Strip No. 1 were briefed for a strike at the enemy convoy. The engineers were likewise ordered to prepare for combat. On the 22nd Company D was taken off the airfields and directed to fortify its bivouac area. Later that day, Company F stopped work on Strip No. 3, and the men were issued rifles and 128 rounds of ammunition each. Farther west, at Strip No. 2, Company E of the 46th was in no immediate danger. General Clowes assigned that unit to the rear sector, about

Map 10: Milne Bay, August 1942

four miles square, where it was to construct fortifications and patrol jungle trails. One platoon was to defend the airstrip, about 75 percent cleared, and smash any paratroop landing the enemy might attempt to make. Protected against air attack by overcast skies, 1,171 Japanese landed that night on the northern shore near Waga Waga, about 6 miles east of Strip No. 3, and began advancing westward along the swampy, mile wide, coastal shelf. Since the jungle track skirting the northern shore crossed the center of the runway site, the enemy was expected shortly. The airfield clearing was an ideal location for a defensive stand. It was improbable that the enemy could successfully carry out an encircling movement. Just to the north were the rugged foothills of the Stirling Range. Between the foothills and the northwestern edge of the clearing flowed Wehuria Creek, which continued on behind the airstrip in a southerly direction. The southeastern end of the clearing was only 500 feet from an inlet of Milne Bay. At 0200 on 26 August most of the men of Company F were sent to join the Australians and the antiaircraft troops already in position

along the southwestern edge of the clearing. Most of the engineers were assigned to the center of the line. Company D, meanwhile, continued digging trenches and foxholes around its bivouac area to the rear and prepared its 37-mm. gun and half-track for action.

The first night was a quiet one for the defenders along the airstrip. No attack materialized. The next day Japanese warships shelled Strip No. 3 and planes raided Strip No. 1. There was no serious damage to either field, but many engineers had narrow escapes. Slowed by soggy terrain and the Australians, enemy ground troops doggedly continued their advance westward. On the 26th some 1,200 more Japanese were landed, and on the night of the 27th the enemy approached the clearing. By early morning they stood at the northern edge, directly opposite the positions occupied by Company F. After exchanging fire with the defenders for about half an hour, the Japanese withdrew. During the daylight hours of the 28th there was no further activity, except for occasional enemy rifle fire on the clearing. Since Allied air superiority had forced the Japanese to restrict themselves to night attacks, the defenders, aware that additional troops had landed, looked for a more determined assault that night. They were not mistaken. Under cover of darkness, the enemy made what appeared to be several haphazard attempts, to cross the strip. All ended in failure. Two or three riflemen got through the defenders’ line and penetrated into Company F’s bivouac area but did not inflict any damage.

Ashore for three days, the Japanese had still made no determined effort to seize the airstrip. On the 29th more reinforcements landed, raising the number of enemy troops to some 3,100 men. Convinced an attack was not far off, the defenders again strengthened their line on the 29th and 30th. Three officers and 132 men of Company F, flanked on both sides by Australian infantry, were already fully committed to the defense of the clearing. The remaining 27 men of the company had moved miles to the rear with the company’s heavy construction equipment and supplies. Members of Company D who could be spared from their work on Strip No. 1 and on the roads leading from the wharf to the airfields were sent to help man the defenses along the clearing. The company’s half-track and 37-mm. gun were moved up to the line alongside those of Company F.

At 0330 on 31 August the attack came. The Japanese laid down heavy rifle and machine gun fire as 300 men prepared to storm across the clearing. Strong counterfire disrupted the enemy’s plans, a hail of bullets stopping the advance before it got started. The Japanese failed even to set foot on the clearing. Nor did they break through along the beach or at Wehuria Creek. At dawn they withdrew, pursued by the Australians. The attack had failed completely. Later that day the engineers counted 160 bodies, most of them in the wooded area opposite the position held by Company F. As the surviving Japanese made their way back to Waga Waga, the engineers bulldozed shallow graves for the enemy dead. Although the enemy had been repulsed, General Clowes did not believe the danger of surprise attack had passed. During the first week in September, Companies D

and F exchanged defensive positions daily. Air attacks continued, and on the 8th, Japanese planes bombed Company F’s bivouac area, killing 4 men and wounding 7. But ground fighting was over. By the second week of September Japanese warships had evacuated most of the enemy troops. The battle of Milne Bay, which was soon to assume legendary aspects for the engineers of the Southwest Pacific, had ended in a complete victory for the Allies.

Allied Preparations Continue

The beaten invaders withdrew from Milne Bay, but the enemy force on the Kokoda Trail continued to advance through the Owen Stanley Range. Outnumbered and poorly supplied, General Rowell’s Australians fell back from one ridge to another. In early September Australian reinforcements were rushed to the front to contain the Japanese advance. MacArthur and Rowell believed the Japanese, overextended as they were, could now be contained. In order to put additional pressure on the enemy, MacArthur planned to execute a flanking movement by sending an American regimental combat team (RCT) from the 32nd Division on foot over the mountains to attack the enemy from the rear. Of the trails that led north through the Owen Stanleys, two seemed most practicable. One, starting from Kapa Kapa, a few miles southeast of Port Moresby, wound through the mountains to Jaure on the eastern slopes. But it presented difficult obstacles since it crossed innumerable hogbacks and at the divide reached an elevation of 5,000 feet. The second track, leading northward from Abau to Jaure, crossed what was believed to be gentler terrain; its highest elevation was about 5,000 feet. On 15 September, a reconnaissance party organized by MacArthur’s G-4, Brig. Gen. Lester J. Whitlock, began to explore the Kapa Kapa Trail. The day before, a company of the gist Engineers had begun improving the dirt track from Moresby to Kapa Kapa. On the 16th, Casey and Sverdrup, who were in Moresby at the time, took charge of investigating the Abau Trail. The march through the mountains would have to wait until the reconnaissance reports were in.39

Casey and Sverdrup reached Abau on the morning of 18 September. They wanted the answers to two questions: could the harbor be made to serve as a base of supply for a regimental combat team and would it be possible to send jeeps and mule trains up over the trail?40 Casey took on the job of exploring the harbor. For “hours that stretched into days” the chief engineer lay off shore in a native canoe sounding the depths of the waters.41 Meanwhile, Sverdrup had started out for Jaure with a party of one American, 2 Australians, 10 native policemen, and 26 carriers. The first day’s march was easy and the party covered 13 miles. But the following morning when they reached the foothills

of the Owen Stanleys, the going got rougher. “Some of the hills we climbed are over 45 degrees—would like to see a mule climb that,” Sverdrup wrote in a letter he sent back to Casey by native bearer. At noon of the fourth day, he noted in his log, “elevation 3,380 and still going up.” After scaling heights of almost 5,000 feet and toiling up precipitous grades of 80 percent, Sverdrup and the members of his party began to suspect that they were “on a wild goose chase,” and would never be able to “build a motor transport road in here and probably not a mule track either.” By the time the group reached Jaure on 25 September, after eight days on the trail, Sverdrup doubted whether it would be possible even to march troops over the route. On the 27th the party began its trek back to Abau, arriving there on 3 October. By this time, Casey, having concluded that the harbor was too shallow even for lightering, much less for use by cargo vessels, had returned to Moresby.42

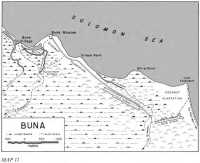

The day Casey and Sverdrup went to Abau the Japanese had reached the native village of Ioribaiwa on the southwestern slopes of the mountains overlooking Moresby and the coastal plain. The Allied position was less precarious than it seemed. The enemy column had overreached itself, and Kenney’s airmen had been knocking out the enemy’s supply line along the Kokoda Trail most effectively. Nor was the war going well for the Japanese elsewhere. The setback at Milne Bay and serious reverses on Guadalcanal induced Imperial General Headquarters to change its strategy temporarily. It planned to withdraw the troops on the Kokoda Trail and concentrate them for the time being on the coastal flats at Buna. Operations in New Guinea were to be held to a minimum until Guadalcanal was secured. In Allied eyes, however, the Japanese were still a powerful adversary. On 23 September, General Blamey assumed direct command of New Guinea Force and two days later launched the Allied counter-drive. Soon the Japanese were in full retreat along the Kokoda Trail.43

As the enemy withdrew, MacArthur adopted a more aggressive plan of action. He envisioned a three-pronged advance on Buna. The Australians were to pursue the Japanese along the Kokoda Trail. One American force was to cross the Owen Stanleys on either the Kapa Kapa or the Abau Trail. A second was to move in small boats from Milne Bay up the northeastern coast. When all these forces were sufficiently close to Buna, MacArthur would order a concerted attack. The success of such tactics hinged largely on getting the troops across the mountains. Casey’s report on the Abau Trail, which he gave to Sutherland on 5 October, indicated a tremendous effort would have to be made to convert the track into a practicable route. The Kapa Kapa Trail appeared to be the more feasible way. By late September, a regimental combat team had been readied for the march. On 6 October, one company of infantry with a platoon of twenty-three engineers set out across the mountains as the advance

detachment. On their backs the engineers carried axes, saws, machetes, and shovels to clear the trail for the troops who would follow. The expedition would be supplied by airdrop. None doubted the march would be difficult, but there seemed to be no other way of getting the men to Buna.44

While on the Abau Trail, Sverdrup had chanced upon a plateau in the northern foothills of the Owen Stanleys which appeared to offer a good site for an airstrip. On returning to Abau he discussed the possibility of building landing fields beyond the mountains and flying the troops across. The practicality of such a scheme was confirmed by Cecil Abel, a missionary who owned a plantation near Abau and knew well the territory north of the divide. The possibility of flying troops and supplies across Papua had been considered before. As far back as July, air and engineer officers had suggested that a field at Wanigela Mission, sixty-five miles southeast of Buna, on the eastern Papuan coast be developed to make possible ferrying troops and supplies from Moresby. At various times during August and September, Kenney had urged that troops be flown to Wanigela and then be moved up the coast to Buna. MacArthur had held back, waiting to see if the Australians could stop the Japanese on the Kokoda Trail. When the enemy began retreating toward Buna, he accepted the plan. On 6 October, Australians were flown from Milne Bay to Wanigela. Under their direction, natives began cutting the grass and readying the landing strip. But Wanigela was many miles from Buna and surrounded by almost impenetrable swamp and jungle. Sverdrup, as a result of his reconnaissances north of the Owen Stanleys, believed that fields could be constructed rapidly in terrain from which Buna would be easier to get to. Early in October, Mr. Abel, who was flown to Port Moresby to talk to Allied commanders, assured them that a landing field could be readily developed near Fasari in the upper valley of the Musa River. From there the troops could make their way on foot along trails over relatively flat, though heavily jungled, terrain. The idea was enthusiastically received all around and MacArthur approved the project. Sverdrup was to round up natives, hand tools, and supplies and march north from Abau to carry out this mission. On 11 October, Abel was flown to Wanigela, where he recruited over a score of natives and set out with them for Fasari. Sverdrup, after laying in a store of tobacco, calico, boy scout knives, garden seeds, and other trade goods, left Abau on 14 October with 185 natives and 5 white men, among them Flight Lt. Michael J. Leahy, who had spent most of his life in New Guinea and knew personally many of the tribal chieftains.45

Reaching Fasari on the afternoon of 18 October, Sverdrup found that Mr. Abel “had made a fine start on the strip.” The site had been burned over and all that remained to be done was to remove some stumps and widen and smooth the clearing. The next morning Sverdrup’s natives joined Abel’s in finishing up the work. Later that day a DC-3 put down at the field, henceforth known as Abel’s Landing. On the loth Sverdrup and Leahy headed north over jungle trails, leaving an Australian officer and the Papuans to put in refinements at Fasari. Near the native villages of Embessa and Kinjaki Barige, they located two fairly level sites, overgrown with kunai grass some eight to twelve feet high. Lured by the prospect of getting trade goods, entire villages turned out to help with the cutting. Soon the work force numbered in the thousands. By pitting villages “against one another as teams,” Sverdrup got the natives to put forth a tremendous effort. At Embessa, “the Musa boys won hands down and got an extra one-half stick of tobacco each as a reward and damn near killed themselves earning it,” he wrote. As the natives were rapidly exhausting the expedition’s stores, Sverdrup appealed frantically to Moresby for additional supplies. The first airdrop, made on 24 October at Kinjaki, disrupted the work there for some time. “At 9:45,” Sverdrup noted in his log, “a B-25 came ... roaring down ... with bomb doors open, and then it rained rice and corned beef. ... When we started to pick up [the] stuff, we found forty percent of [the] corned beef tins smashed and opened. No holding [the] boys after that. Had to go to camp and eat themselves out of shape.” The plane having dropped a note instructing him to go to Pongani, Sverdrup on 25 October hiked to that coastal village. Fifty men of Company C of the 14th Combat Battalion were already there, having been part of a group flown from Moresby to Wanigela in mid-October and moved up the coast by boat. Since the troops seemed to be making little progress, Sverdrup went back to Kinjaki to bring up several hundred natives, and returned to Pongani with them on 28 October. Working twelve hours a day in oppressive heat, the natives and engineers completed the Pongani airstrip in two and one half days. By the end of October planes could land there, at Kinjaki, and at Abel’s Landing. Sverdrup was proud of his “Papuan Aviation Battalion,” defying anyone to beat its performance at Pongani. “One thing has been definitely proven,” he wrote. “If strips are to be built by hand in this country, native labor competently led is the only answer.”46

Meanwhile, the engineers at Port Moresby and Milne Bay were struggling against almost insurmountable odds. Colonel Matthews was hard put to find the wherewithal to push construction at these advance bases. His staff was too small. His engineer, Yoder, was borrowed from the 96th Engineers. He had almost no personnel to help him organize and direct the work, and the troops at his disposal were too few to carry the load. He had the 808th, the

96th, one battalion of the 91st, and Company E of the 43rd at Moresby and two companies of the 43rd and one of the 46th at Milne Bay—a total of some 3,200 men.47 But more annoying than the shortage of troops and personnel was the absence of even a general statement of what he was to build. “No one at GHQ, at Hq, Fifth Air Force, or at Hq, USASOS, ever revealed, to me at least,” Matthews later wrote, “the probable plan and garrison to be supported.”48 The Australian commanders, asserting the authority granted them of exercising operational control when an enemy attack threatened, took the engineers off important construction projects. When the Japanese were approaching Moresby, General Rowell had ordered the 808th to stop work on airfields and sent them into combat reserve along the Goldie River northeast of Moresby. There they remained until the arrival of the 114th in mid-September. After the Japanese withdrew from Milne Bay, General Clowes refused to let the engineers resume work on Strips No. 2 and No. 3, despite the fact that Matthews had ordered this work expedited. Casey, inspecting Milne on 15 September, discovered that Clowes had overruled Matthews’ instructions and had diverted the engineers to repairing strip No. 1, building a dock, and standing guard. It took a direct order from MacArthur to Blarney to get the men back on airfield construction. Marshall, the commanding general of USASOS, meanwhile tried unsuccessfully to get the 11 6th Combat Battalion to stop training in Queensland and go to Moresby, where under USASOS direction it would help improve port facilities. At the same time, the Allied Air Forces opposed taking engineers off airfields to improve ports and to build such things as the road to Kapa Kapa.49

MacArthur, visiting Moresby in late September, quickly concluded that centralized co-ordination of all service activities in New Guinea was urgently needed. On 5 October he established the Combined Operational Service Command (COSC) for New Guinea under the direction of New Guinea Force. This was to be a joint Australian-American logistical organization; its function was to co-ordinate all service activities in the forward areas. General Johns, now Chief of Staff, USASOS, was designated commander both of Advance Base and of COSC. Each of the sections in Headquarters, COSC, had two chiefs, one an American and the other an Australian. Matthews was henceforth Engineer, Advance Base, and together with an Australian lieutenant colonel, head of COSC’s Engineer Construction Section. Operating under priorities laid down by Blarney, Johns was to be responsible for all engineer work in the advance bases. He was to prepare a coordinated plan for building airdromes, roads, ports, and other installations. Under him were all Australian and American engineer

units in the service areas. He was to allot them to the various projects in such a way as to carry out most expeditiously Blarney’s wishes. This was an attempt, insofar as construction was concerned, Johns wrote later, “to provide the maximum utilization of the meager means available. ...” But bringing about an integration of effort would take considerable time.50

As Johns took over his new duties, more and more of the engineer effort was going into port development. On 11 September MacArthur had sent Casey to New Guinea to find out what could be done to increase the capacity of the ports at Moresby and Milne Bay. Casey had seen that it would not be easy to enlarge the Moresby port. Shoal water ran out to about 1,500 feet from shore. With from 11 to 18 feet of water at low tide, the harbor was too shallow for large ships and too deep for construction of a causeway. A piling approach dock seemed to be the only answer, but there was no piling at Moresby and little prospect of getting any from Australia. A deep-water dock had existed at Bootless Inlet, a few miles to the east, but the Australians had destroyed this and mined the harbor without plotting the mines. Matthews had learned that oceangoing vessels could come to within 50 to 100 feet of Tatana Island, about 4 miles northwest of Moresby. The island was separated from the mainland by half a mile of water from 6 to 12 feet deep at high tide. One of Matthews’ officers had waded from the mainland to Tatana at low tide and was never in water above his chest. Matthews suggested that a causeway be constructed across this shallow water and that a floating pier be built on the island first and permanent docks later as labor and materials became available. Casey readily accepted this plan. Visiting Milne Bay, he found that docking facilities could be easily expanded. Two crib piers already in could be extended with the addition of pile piers into deeper water 250 feet from shore to provide berths for large vessels. Casey sent word back to USASOS that launches, pontons, lumber decking, and piling would have to be sent to Moresby and Milne Bay immediately.51

Once construction started, the engineers made rapid progress. On 6 October Matthews reported the new pier at Milne could take a ship up to 430 feet long and with a 22-foot draft. Two days later he began construction of the causeway to Tatana Island. Part of the 2nd Battalion of the 96th Engineers opened borrow pits on the island and on the mainland from which to take rock and dirt. The men loaded their trucks, drove them out on the lengthening causeway, and dumped the loads into the shallows. The gap was gradually closed and the roadway packed by the traffic of the trucks. The floating pier was built concurrently on the north side of the

The Port Moresby causeway, looking toward Tatana Island (General Johns in the foreground, third from left)

island. On 30 October the causeway was opened to traffic, and on 3 November, the floating pier took its first ship.52

Work was proceeding on airfields but far too slowly to satisfy Kenney and his generals. As the tempo of the air war quickened, their discontent with the engineers’ progress grew. At Port Moresby increasing numbers of planes were being based on the dusty fields, which had neither camouflage nor adequate revetments. The airmen, among them Brig. Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead, Kenney’s deputy and commander of the advance echelon of the Fifth Air Force at Port Moresby, were obsessed with the fear that the Moresby dromes might not be ready for all-weather operations when the rainy season began in late November. Their appeals for the assignment of more engineers to Air Force projects were coupled with predictions that fields would be washed out and planes grounded if the “wet” commenced before runways, taxiways, dispersals, and access roads were hard surfaced. But

concern over the progress of the fields did not deter the air force from heaping new demands on the engineers. Among the items they requested were steel huts, electric lighting, and screened mess halls with concrete floors.53 “As long as we were the only ones doing any fighting in the American forces,” Kenney later explained, “I was going to see that if any gravy was passed around, we got first crack at it.”54 One of the Fifth Air Force’s frequent protests against the slowness of airfield work was made at the same time that Colonel Matthews was being asked to construct “water-borne sanitary facilities [and] install wash bowls and other china fixtures” at air force installations near Port Moresby. The engineers of Advance Base refused to sanction such departures from theater of operations plans. Unable to get what he wanted through the usual channels, Kenney began procuring materials for air force projects himself and shipping them from Australia to Moresby. Matthews, learning what was afoot, invoked the authority of General Johns as base commander to control construction supplies and confiscated the cargoes. In order to bypass such control, Kenney began flying materials directly to his units in New Guinea. Relations between air and engineer officers were rapidly deteriorating. The air force kept up an almost constant complaint that the engineers were devoting too much effort to projects which, in the eyes of the airmen, were of relatively small importance. The engineers made no secret of the fact that they believed the airmen were too demanding. When, on 8 October, General Whitehead issued a stinging indictment of Colonel Matthews, stating, in effect, that Advance Base was going back on its commitments to the Fifth Air Force, Casey felt obliged to intervene.55

Writing to Kenney on 14 October, Casey pointed out that the construction program at Moresby consisted of a good deal besides jobs for the Army Air Forces. “The Air Corps,” he reminded Kenney, “is vitally concerned in the program as a whole, as airdromes without access roads will not be usable during the wet season nor will air operations be effective unless unloading facilities and transport facilities in the harbor area are materially improved.” The engineers were putting first things first. Not having enough manpower to undertake all the projects requested of them at once, Casey explained, they had to split the program into two parts—jobs which were “absolutely essential” and jobs which were “useful but which can be postponed.” In the first category were all-weather dromes, improved ports, minimum shelter and utilities, and hard surfacing for key roads; in the second were blast-proof revetments, additional roads, more ample water supplies, and more comfortable quarters. Since the essential projects must be usable before the others were tackled, the Fifth Air Force would have to wait for much of the construction

it wanted. But they could rest assured, Casey said, that the Moresby fields would be ready for the rains. Apparently mollified, Kenney sent to his airmen at Moresby a radio prepared for him by Casey’s office. The chief engineer, the message read, was “fully cognizant of the situation” and would have the dromes “in shape to operate from” when the rains began.56

During October the engineers made great strides toward completing the New Guinea dromes. The “roller coaster” runway at Three-Mile was torn up, regraded, and hard surfaced. The field at Rorona was lengthened to take heavy bombers. New strips were begun at Bomana and Ward’s Drome. Dispersals were provided for twenty-six planes, revetments for twelve. At Milne Bay, Strip No. 3 was graveled and covered with mat. Still, much essential work remained. The gravel runways at Laloki and Seven-Mile Drome had yet to be sealed or surfaced with mat. Most access roads had to be paved, and nearly half of the three hundred dispersals and plane pens provided so far were suitable only for use in dry weather, and many more were needed. Drainage systems left much to be desired, and taxiways, hardstands, and warm-up areas were far from adequate. Believing that the engineers at Moresby were doing all that was humanly possible to hasten construction, Casey was trying hard to move the units that remained in Australia to New Guinea, but without success. Because of the acute shortage of ships, USASOS could spare no vessels for the engineers. The units already in New Guinea continued to carry the load alone.57

The strain of constant operations was beginning to tell. Men and machines were wearing out. Sverdrup, stopping at Moresby on his way back to Brisbane from Pongani, found the situation alarming. The engineer troops were tired and large numbers were reporting for sick call. Many were suffering from malaria, dengue, dysentery, and disease of the skin. Accidents were frequent. “I am much worried,” he wrote to Casey, “about how these same Engineer troops will be able to perform when we advance, as we hope to do. ...” The condition of the units’ equipment was just as discouraging. A large part of it was sidelined for repairs. Mechanics were scarce. Spare parts were almost nonexistent. Such cargoes of equipment and parts as were reaching Australia seldom found their way to New Guinea. USASOS could not arrange for shipping space, and cargo space on planes was at a premium.58

As the rainy season approached, the airmen grew increasingly impatient. An unseasonable downpour on the night of 21 October seemed to confirm their forebodings. Seven-Mile, Three-Mile, and Rorona were unserviceable for a time. The road to Waigani was barely passable, and the bridge to Laloki was washed out. Greatly perturbed, Kenney again brought pressure to bear on the engineers. In a

letter to MacArthur on 26 October he predicted that with the onset of the rains at least two squadrons would have to be returned to Australia. He conceded that the strips themselves were nearly finished but stressed the fact that dispersals, hardstands, and access roads were not. Stating that he could not operate effectively without the missing facilities, he insisted that they be supplied at once. “Otherwise,” he warned, “reliance on aviation operations is not well founded.” Both Sutherland and Casey hastened to reassure him. Casey again pointed out that there was a big job to be done at Moresby and few engineers to do it, but he promised that “all work necessary to provide maximum use of the New Guinea airdromes during the wet weather season [would] be pushed to the maximum within the limitations of plant and men.”59

At this juncture Kenney again began to press for operational control of the 808th Aviation Battalion. Early in November he raised the question as to what authority there was for having the unit under USASOS. Protesting to Sutherland that aviation engineers were being taken off the airfields to work on the Tatana causeway and to operate cranes on the docks, he asked that the battalion be placed under him. Casey, as before, strongly opposed placing the aviation engineers under Air Forces’ control. Given the tremendous scope of the construction program and the small size of the engineer force, he believed the existing arrangement to be the most efficient. The pooling of construction units and resources had, he felt, worked to the advantage of all concerned. Actually, only twenty-five men had been diverted from the 808th to other jobs, whereas the bulk of the service engineers had been employed in building airdromes. “If it is regarded that the aviation Engineers are an Air Corps unit and the only engineers [intended] primarily for airdrome construction,” he told Sutherland, “the counter view may be taken that all other engineer units had been diverted from other assignments to work for the Air Corps. ...” Engineer dump truck companies and details from general service regiments had worked for long periods hauling gasoline and bombs for the air force and loading planes. This work, Casey said, had been undertaken in the knowledge “that the job had to be done by whatever means were available.” As the chief engineer saw it, nothing would be gained by setting up two independent construction organizations to compete for materials and equipment, duplicate each other’s planning, and get in each other’s way. Casey’s views prevailed. The 808th remained under the control of USASOS.60

The stir created by the Fifth Air Force had served to emphasize the need for sending more engineers to New Guinea, and Casey was now able to persuade Marshall to make shipping available. By 8 November the 576th Dump Truck Company and elements of

the 43rd and 46th General Service Regiments were loading to ship out within a week, and USASOS was promising to transport more units to New Guinea at an early date. Meanwhile, at Moresby additional engineers were being pulled off nonair-force projects and sent to work on the dromes. Australians took over operation of the quarry and construction of docks and dumps as the Americans moved in with their equipment to finish up access roads, hardstands, and dispersals. By mid-November, the first reinforcements from Australia were unloading their gear on the Moresby docks. On 18 November the chief engineer sent word to Kenny that “every effort [was] being made to get and hold all airfields here to wet weather operational condition.”61

Maps

The days before the attack on Buna were scarcely less hectic for the topographic engineers than for the engineers engaged in construction. The coming offensive was generating a brisk demand for maps. Top commanders and their staffs had to be furnished with strategic maps of the combat zones. Ranging in scale from 1:500,000 to 1:1,200,000 and depicting large areas with such salient features as mountains, large bodies of water, important lines of communications, and major centers of population, maps of this type were indispensable to men who were planning campaigns. Commanders in the field were calling for tactical maps with scales varying from 1:62,500 to 1:300,000. The scale 1:63,360 was especially popular because it was one inch to the mile. Necessary in moving large bodies of men across unfamiliar terrain, these maps supplied much the same information as strategic maps but in far greater detail. For artillery batteries and small infantry units, the engineers had to provide battle or terrain maps with a scale of 1:20,000. Since these large-scale projections were used in firing on unseen targets, their delineation of distance, direction, and elevation had to be very precise. All these varieties of maps had to be supplied quickly, some of them by the thousands; and because Ghormley had no military mapping units, MacArthur’s topographers not only had to cover New Guinea but the Solomons as well.62

Among the least explored areas of the world, the islands north and northeast of Australia had been mapped haphazardly or not at all. In months of searching, the engineers of USAFIA had failed to turn up much information of value on the now vital parts of Melanesia. The Army Map Service at Washington, an agency of the Corps of Engineers responsible for providing maps to the Armed Services, could supply but few of the far Pacific. Nor could the Australians do much better. Their topographical surveys had been confined primarily to the continent itself—in fact, almost entirely to the southeastern coastal region. Good maps of Papua and the

mandated territories were simply not to be had. The only military maps of the Buna area—Australian sketches drawn to a scale of four miles to the inch—were so seriously in error that they showed some rivers flowing up over mountains. Just as disheartening was the situation with regard to the South Pacific. Although sketches had been made of some of the Solomons, no comprehensive effort to map the islands had ever been made. Data on the topography of Guadalcanal, now the scene of desperate fighting, was both incomplete and unreliable. In mapping the combat zone, a vast land and water area much larger than the United States, the engineers had to start virtually from scratch.63

To map the forward areas by the time-honored method of surveying the ground was impossible. Much of the contested territory was occupied by the enemy, and even where the ground was accessible, there was no time for painstaking measurements with transits, tapes, and levels. Chief reliance had to be placed on aerial photography. New techniques, just coming into use, enabled cartographers to make maps from photographs of the terrain furnished them by airmen. Mapping, once the exclusive province of the engineers, was now a joint responsibility of the Corps of Engineers and the Air Forces. A recent development was trimetrogon photography, which involved mounting three cameras in a plane with one pointing straight down and the others pointing sideways. Three cameras arranged in this manner could, of course, photograph a much wider area than could one camera aimed directly down. But aerial photographs had their limitations. Unless the elevation of some point in the picture were known, there was no way of determining the elevation of any of the terrain features. Because the photographs were taken from an altitude of 20,000 feet or more, many objects appearing on the prints, each about nine inches square, were hard to make out. Photo interpreters had to try to identify an object mainly from its outline and its shade of gray. It was not easy to deduce what might lie beneath the heavy jungle growth directly below the camera or behind the mountain off to one side. Shots taken from oblique angles presented an added difficulty—that of determining the elevation of the terrain features and their distance from one another.64

The men of the Australian Survey Corps, the only topographers in Mac-Arthur’s command at the outset, were surveyors of the ground with little or no experience in photomapping. Although the 8th Photo Squadron, an Air Forces unit trained in trimetrogon photography, began arriving in Australia in April, few, if any, engineers were yet available to transform photographs into maps. Johns, soon after becoming Chief Engineer, USAFIA, had requested two mapping units from the United States—an army topographic battalion and a corps topographic company, but some time was to elapse before these units

would reach the Southwest Pacific. Casey, who assumed over-all direction of the mapping effort on becoming chief engineer of SWPA, was meanwhile planning to co-ordinate the work of Australian and American topographers. Shortly after the signing in Washington on 12 May of the Loper-Hotine Agreement, a convention between the British and the Americans that gave the latter primary responsibility for mapping in the Pacific, Casey reserved for the American topographic units a dominant role in SWPA’s mapping program. The Americans, under USAFIA, were to concentrate mainly on mapping the forward areas; the Survey Corps, operating under General Blamey, on mapping Australia. While the Allies would cooperate fully in all they did, the Australians would, as a rule, be the surveyors, the Americans the photo-mappers of the Southwest Pacific.65