Chapter VI: The Drive Toward Rabaul

Preparing for CARTWHEEL

With victory in Papua and on Guadalcanal virtually assured, the joint Chiefs were ready to consider further offensive moves. On 14 January 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill met with the Combined Chiefs at Casablanca to discuss strategic objectives for the year. By 23 January overall goals were fairly well agreed upon. Insofar as the South and Southwest Pacific were concerned, the main objectives in 1943 would be the carrying out of Tasks Two and Three of the directive of 2 July 1942. MacArthur’s plan of campaign against the Japanese entrenched in New Guinea and the Solomons was named ELKTON. Basically it provided for a two-pronged drive toward Rabaul by Southwest Pacific forces along the coasts of eastern New Guinea and western New Britain and by South Pacific forces through the Solomons. (Map 12) But the assault could not be undertaken at once. There were not enough troops or supplies in the two theaters in early 1943, nor had MacArthur and Halsey worked out a coordinated plan. On February, Rear Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson, Halsey’s deputy, reached Brisbane for conferences with MacArthur and his staff. In mid-February, the Joint Chiefs scheduled a conference of delegates from the South and Southwest Pacific to be held in March in Washington. There the conferees would review the numbers of men and the amounts of supplies available and determine in general how they were to be allocated.1 Meanwhile, the engineers in the two theaters were fully occupied in preparing plans for the support of the combat forces in the coming campaign, to be known as CARTWHEEL. Since the capture of Rabaul would require the progressive advance of air and naval forces, not only combat support but also the construction of airfields and naval bases in areas captured from the enemy would continue to be a most important task.

Additional Engineers Arrive

The number of engineers in the South and Southwest Pacific was increased in the first months of 1943. On 17 February, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, the commander of Sixth Army, together with members of his advance echelon, arrived by air at Brisbane; five days later, his engineer, Col. Samuel D. Sturgis, Jr., with an engineer officer and an enlisted man came in at Amberley Field.

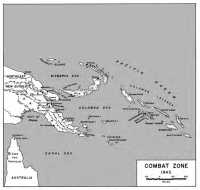

Map 12: Combat Zone, 1943

Colonel Sturgis set up his headquarters at nearby Camp Columbia. The remainder of the engineer section, on its way to Australia by ship, was expected in mid-April. By visits to engineer offices and installations in and near Brisbane, including Casey’s office and the engineer section of Headquarters, Base Section 3, and by trips through eastern

Australia and Papua, Colonel Sturgis soon became acquainted with current operations and learned of some of the major engineer problems in the theater.2 In February and March, several units

arrived in the Southwest Pacific—the first since the preceding June. Among them were two aviation battalions, a heavy shop company, and a maintenance company. Also earmarked for SWPA and scheduled to leave the United States in March, were an aviation battalion, a depot company, a base equipment company, two airborne aviation battalions, and a dump truck company. Scheduled to arrive in the South Pacific in the first half of 1943 were three general service regiments, two depot companies, and a heavy shop company.3

The Engineer Special Brigades

Engineer units of a novel type were to be employed in the coming campaign in New Guinea. These were the engineer special brigades (ESBs). Originally called engineer amphibian brigades, they had been organized and developed in the United States beginning in June 1942 in accordance with new concepts for putting a landing force ashore. The required techniques devised by top military and naval planners called for moving fully equipped infantry units in small craft from one shore to another where the distance involved was less than a hundred miles. Because it would obviate using large naval vessels close to shore, where they would be exposed to attacks from land-based aircraft, such a technique would be invaluable not only for operations against continental Europe but also for driving the Japanese out of the many islands of the western Pacific.

When this new concept of amphibious warfare was developed, the invasion of Europe took precedence over operations in the Pacific. The innovation was devised primarily to move troops across the English Channel for an invasion of the Continent. Sole reliance on small craft was a departure from traditional naval concepts. Landing craft had always been carried to the target area aboard transports. When an assault force arrived off an enemy-held shore, the craft were lowered over the side of the ships into the water, the troops boarded them by climbing down the ships’ nets and, protected by fire from ‘cruisers and battleships, headed for the enemy-held beach.

Moving troops and supplies from island to island in small craft and organizing newly won beachheads would appear to be a joint Army-Navy responsibility. In the first months of 1942, the Navy, still relying on enlistments, was short of men for its ships and shore installations, and so could not embark on a program of organizing and training new types of amphibious units. Responsibility for developing and training the amphibious brigades was given to the Army and assigned to the Services of Supply. Mainly because moving troops across short stretches of sea resembled river-crossing operations, the Services of Supply gave the Corps of Engineers the responsibility of organizing and training the units. Twelve brigades were to be organized, each an integrated but flexible unit capable of transporting one division.

In September, MacArthur had requested one brigade. Col. Arthur G. Trudeau, a pioneer in developing the

brigades, visited MacArthur’s headquarters in November to discuss the advisability of sending three to the Southwest Pacific. MacArthur strongly favored getting these new units. It was readily apparent to him that they would be ideal for operations against the Japanese in the islands north of Australia. It would now be possible to move men and supplies along the coasts of New Guinea and to nearby islands, through narrow channels, across uncharted, shallow, reef-choked waters, without the use of naval vessels. And the perplexing question of whether amphibious operations in the Southwest Pacific should be largely under Army or Navy control would be solved.4 In Casey’s words, the brigades would “afford [the Army] an independence of operation and unity of control not otherwise attainable if dependence had to be placed on the Navy for such movement.”5

The initial brigade to go to the Southwest Pacific was the 2nd, commanded by Brig. Gen. William F. Heavey. During February and March 1943 the elements of the organization arrived in Australia at various ports from Sydney to Townsville. The entire brigade consisted of just under 7,400 officers and men. Major components were a headquarters and headquarters company and three boat and shore regiments.6 Each regiment, with approximately 1,950 officers and men, had two battalions: a boat battalion to man the craft that would transport the infantry and other troops from island to island, and a shore battalion to help troops embark on the near shore and establish and organize the beachhead on the far shore. Each brigade had five auxiliary units—a boat maintenance company, a quartermaster battalion, an ordnance platoon, a signal company, and a medical battalion. The brigade got its 180 boats from the Navy. The amphibian engineers arrived in the Southwest Pacific equipped mainly with LCVPs (landing craft, vehicle, personnel). These wooden boats were 36 feet long and had 11-foot beams. Powered with 225 horsepower diesel engines, they had a speed of 9 knots. They could carry 36 fully-equipped infantrymen or 4 tons of cargo. Protection was provided by quarter-inch armor plate on the bow and sides. The amphibian engineers hoped to add soon to their small stock of the newer and larger LCM(3)s (landing craft, mechanized), which were 50 feet long, 14 feet wide, were made entirely of steel, and had a speed of 10 knots. They could carry 60 men or 18 tons of supplies. Before long, the elements of the brigade were concentrated at Cairns and Rockhampton, and joint training began at nearby beaches with American and Australian infantry units. Some of the amphibian engineers attended specialist schools in reconnaissance, signal communications, and boat maintenance. Others trained in the Australian “bush” in infantry tactics and in fighting in jungle country.7 The

arrival of the amphibian engineers was not greeted with enthusiasm on all sides. General Heavey found “considerable antagonism” on the part of many Navy officers, a number of whom expressed serious doubts that the brigades could operate successfully.8

Late in January the 411th Engineer Base Shop Battalion, 1,145 officers and men, arrived with the first elements of the brigade. The 411th had originally been organized to repair and maintain the amphibian engineers’ landing craft. When the decision was subsequently made to send the craft overseas knocked down, the mission of the 411th was changed to boat assembly. The unit was reorganized so that all three companies could put landing craft together. The first job in Australia was the building, with the help of a regiment of amphibian engineers, of an assembly plant at Cairns. Here LCVPs, and later LCMs, were to be launched and used in the drive up the New Guinea coast toward Rabaul. The 411th had not been organized or trained to build an assembly plant; it turned to this job when it arrived at its destination only to find “the plant not even started and the site encumbered with an old saw mill whose owners were holding out for a high settlement.” It was many weeks before the battalion retrieved its equipment from the various Australian ports. Thereafter followed the struggle to build the assembly plant with its three production lines.9

Problems of Organization

If CARTWHEEL were to have proper Engineer support, the continuing disagreement in the Southwest Pacific between the Engineers and the Army Air Forces over the control of airfield construction would have to be resolved. The Air Forces persisted in its attempts to get control of the aviation units, and Casey continued to oppose strongly the demands of Kenney and Whitehead. He maintained, as he had done previously, that if the aviation units were placed under the control of the Air Forces and were used solely on airfield construction, there would in effect be two construction agencies in the theater. They would have to compete for the limited amounts of materials, equipment, and spare parts. Overall planning for construction would become needlessly complicated, and control of the construction program would become much more difficult. It was Casey’s view that, in the communications zone, there should be not two construction organizations, but one, and it should be under the operational control of USASOS, to be used on any type of work that MacArthur believed was most urgent.10 The question was settled late in February. MacArthur directed that the construction of airfields continue as

before. USASOS would be responsible for all construction for American forces in the communications zone. Task force commanders would be responsible for construction in the combat zone until that responsibility was transferred to USASOS. When airfields were completed, they would be released to the Air Forces for maintenance.11

To provide for better administration of the growing number of American units, MacArthur reconstituted, under his direct command, United States Army Forces in the Far East on 26 February. The headquarters was to provide administrative control for all American units in the Southwest Pacific, including those in USASOS, the Fifth Air Force, and the newly arrived Sixth Army. MacArthur appointed Casey Chief Engineer, USAFFE. Casey transferred some of the men for his new office from his staff in GHQ SWPA; a few came from USASOS. Most were officers and men who had recently arrived from the United States. As Chief Engineer, USAFFE, Casey had duties similar to those he concurrently had as chief engineer of SWPA. But in his new position, he was concerned mainly with providing technical supervision over American units only; as Chief Engineer, GHQ, he was responsible for coordinating the entire Allied engineer effort in the theater. Since the functions of the two offices were so much alike, it soon proved difficult to prevent overlapping of functions and duplication of work.12

Engineers in Forward Areas

The engineers continued their explorations and studies of the forward regions where the coming campaign was to be fought. Reconnaissance from the air and on the ground provided considerable information about the most desirable sites for airfields and bases. As early as December 1942, Colonel Sverdrup and others had traveled through the Markham Valley in east central New Guinea—a crucial area in any further advance against the Japanese. They found many suitable sites for airfields. Near the native village of Nadzab, the favorable terrain and the long dry season would make construction of runways for heavy bombers and fighters fairly easy. Aerial photographs indicated that at the coastal village of Lae the Japanese had two airfields that could be enlarged and developed, and that the road from Lae to Nadzab could undoubtedly be readily improved to make possible trucking in gasoline and other supplies. Sites would also have to be found for airfields farther west.13 The Air Forces was concerned about growing Japanese strength in northwestern New Guinea and in the islands of the Netherlands Indies. The enemy apparently was building up his potential for offensive action in the Darwin–Merauke–Cape York area. Kenney therefore wanted to strengthen the airfields at Horn Island, at Jacky

Jacky, and in the Millingimbi area near Darwin. These projects were to proceed “simultaneously and with the greatest possible speed.”14 In the South Pacific aerial reconnaissances were being made of the Solomons, especially of those places where Japanese installations were located.15 In February reconnaissance parties sent out by Casey’s office investigated two little-known islands—Woodlark and Kiriwina—midway between Papua and the Solomons and found excellent sites for airfields.

Engineer work was already under way in the most forward areas. A continuing task was improving communications in northeastern New Guinea, where airfields, roads, and trails were primitive, to say the least. A promising link between southern New Guinea and the Markham Valley was the 68-mile-long trail stretching from the native village of Bulldog north over the Owen Stanleys to Wau. Improvement of this track would make possible transporting substantial quantities of supplies overland from the Gulf of Papua to Lae and Salamaua. On 18 February a company of Royal Australian Engineers began work at Bulldog, and three days later another company started in at Wau. American units could not be spared from high priority airfield construction, but a number of bulldozers were sent to the Australians for this difficult construction job. The terrain was rugged, little material could be found for surfacing, and downpours

were frequent; the Australians had to do much of the work with picks, shovels, and crowbars. Progress was slow. In out-of-the-way areas to the north, work was speeded on runways.16 Early in March, Sverdrup directed Lieutenant Leahy to prepare one strip at Mt. Hagen and two at Ogelbang, four miles to the northwest.17 For these jobs Leahy rounded up 5,000 Papuans who worked with great energy in the way they knew best: They hauled earth in their native baskets, Colonel Robinson wrote later in describing this project, “and compaction was accomplished by thousands of bare native feet tramping in time with their weird chant or ‘sing-sing.’ ”18

Troop Requirements for ELKTON

By 22 February, Casey’s office had completed a preliminary study of engineer troop requirements for ELKTON. More exact needs, to be worked out later, would in large measure depend on the time allotted for the various phases of the operation, the number of native laborers who could be recruited, and the demands for additional construction which might be made. Principal engineer tasks would include supporting the combat troops, building airfields, ports, and roads in the combat zone, and preparing and distributing maps. It was estimated that 15 new runways would have to be built, 16 improved, and possibly

45 maintained. Port facilities in the South Pacific would be built principally by naval construction battalions; in the Southwest Pacific, by engineer units. In both theaters the combat engineers, though handicapped by inadequate equipment, would have to do virtually all road construction and maintenance. Mapping units would be hard pressed. The South Pacific area, which already had one aviation topographic company, needed, in addition, a corps topographic company. All told, a large number of additional units would be required for the campaign—ten general service regiments, two aviation battalions, two port construction and repair groups, two equipment companies, one topographic battalion, one topographic company, two depot companies, and two maintenance companies. Some of these units were already en route to the theaters.19

The South Pacific

In the South Pacific the engineers had begun to prepare in January for the coming campaign. Organization in that theater was complicated. Halsey had many more subordinate commanders reporting directly to him than MacArthur had. There were two major ground forces—the Army and the Marine Corps—as well as various Air Forces elements. The bulk of the U.S. Pacific Fleet was serving in the South Pacific. A multiplicity of service commands supported the Army, Navy, and Air Forces. The South Pacific had no chief engineer to supervise and coordinate engineer work. There was, instead, a Base Plans Section, consisting of Colonel Beadle and two Navy captains from Halsey’s staff. The three members reviewed requests for projects received from island commanders or from the Base Plans Board in Halsey’s headquarters. They then approved or disapproved construction, fixed priorities, and designated the constructing agency. Projects were built under the direction of the island commanders. Insofar as the Engineers were concerned, the most important service force was SOS USAFISPA, under Maj. Gen. Robert G. Breene. On Halsey’s orders, it and other supply agencies began assembling supplies and developing bases early in 1943. Colonel Beadle, as SOS engineer, and his staff were thus fully occupied during the months before the campaign was scheduled to start.20

Engineer units worked with Seabees and Marine engineers to strengthen various islands of the South Pacific. The marines were building up Guadalcanal as a forward base. Engineer construction units were scheduled to be sent in by the middle of the year. In the New Hebrides the 822nd and 828th aviation engineers were improving Bauer and Quoin Hill fields.21 On Fiji the 821st was continuing to improve Nandi airdrome. The battalion was also working on such projects as hospitals and infantry and artillery positions in the

Nandi area. An extensive road improvement program was under way. The commanding general of the island selected a plateau 2,000 feet above sea level as the site for a rest camp. After conducting an extensive survey, the unit began work on an 18-mile road from Nandi to the camp, a difficult job, as much of the route had to be blasted from almost sheer rock.22

On New Caledonia the major task was improving the airfields. The 811th engineers were at various places—Company A was at Tontouta; B, at Oua Tom; and C, at Plaines des Gaiacs. With the installation of aviation gasoline storage tanks on Penrhyn and Aitutaki, work on the alternate ferry route was almost complete. Such slight construction and maintenance as was still required was done by engineer units of the task forces on the islands.23 Construction was now under way in New Zealand, where work was carried on in and near Auckland. In early 1943 New Zealand’s Public Works Department, using local contractors, was building a 1,000-bed hospital, a replacement and supply depot, a camp, and installations for the Quartermaster Corps. The exploration for oil continued. In January 1943 the managing director of the Shell Oil Company in New Zealand asked Colonel Beard for help in testing a geological formation on South Island. In March the War Department approved, and plans were made to begin drilling in several weeks.24

The combat forces focused their main attention on the Solomons. The steady infiltration of the Japanese down the island chain posed a continuing threat to Guadalcanal. Halsey decided to seize the Russell Islands, about thirty miles to the northwest. Occupation was scheduled for late February, with the 43rd Infantry Division assigned to the operation. The division’s 118th Engineer Combat Battalion sailed with the assault forces for the Russells on 15 February and landed on the 21st. No enemy troops were found. Combat engineer missions comprised, for the most part, road improvement, installation of water points, and clearing of gun positions. Naval construction battalions built the airfields. The 18th engineers found their tasks easy. They were able to establish water points in short order, and, since most of the terrain was flat and coral surfaced, road construction proceeded rapidly.25

As preparations for the offensive increased, engineer supply was given greater attention than before. In March 1943 a general engineer supply depot was organized at Noumea. Subsequently, the Seabees, with some help from Army engineer units, built a large depot, where a heavy shop company was installed. Supplies from the United States were stored there and then distributed to engineer units in the South

Pacific. An additional mission of the depot was to receive, store, and distribute spare parts. Since there was no spare parts company, men had to be taken from the Engineer Section, SOS, and from a maintenance company to man the depot’s spare parts section. The result was that a skeleton force had to carry out the important job of distributing parts to engineer units, with about 20 men trying to do the work of 200.26

Further Overall Planning for the Campaign

With plans for the campaign well along, representatives from the Southwest and South Pacific arrived in Washington early in March for a series of conferences with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and War Department planners. General Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, made it plain that large forces would be needed. At least 22% divisions and over 4,000 additional aircraft would be required. The Pacific delegates found that there was no chance of getting that number of men and planes; the shortage of shipping alone precluded sending them. The decision was made to limit operations in the two theaters in 1943 to Task Two—that is, the seizure of the northern Solomons, northeastern New Guinea, and western New Britain—but with the additional objective of seizing the small islands of Woodlark and Kiriwina to the east of New Guinea. Bombers based on these islands could easily reach Rabaul, about 300 miles away. General MacArthur would command operations outlined by ELKTON. The matter of timing was left to the theater commanders. On 28 March, the Joint Chiefs issued their directive for the forthcoming campaign. MacArthur and Halsey were to establish airfields on Woodlark and Kiriwina, seize various areas along the northeast New Guinea coast, including Lae, Salamaua, Finschhafen, and Madang, occupy western New Britain, and occupy the Solomon Islands as far as southern Bougainville. Late in March, Halsey and MacArthur met at Brisbane to work out the many details. They agreed to carry out a series of approximately thirteen assaults in a period of eight months. They planned to begin the campaign with simultaneous invasions of Woodlark, Kiriwina, and New Georgia. Thereafter, Southwest Pacific forces would seize areas along the eastern New Guinea coast while South Pacific forces would move through the Solomons as far as southern Bougainville. Finally, MacArthur’s forces would seize parts of western New Britain. CARTWHEEL was to begin about June.27

General Casey repeatedly stressed that even with the lowered requirements, the engineer force contemplated for CARTWHEEL was too small. The Air Forces alone required a tremendous amount of construction. On 8 April the total air strength in the Southwest Pacific was 516 planes. There were expected to be 1,330 by the end of the year, plus a 25-percent reserve. If the airfields for this enlarged force were to be provided, a substantial increase in engineer strength was

necessary. The engineers would have to do much work for the ground and service forces. It was essential to have a balanced engineer force, but such a force was not in the theater in early 1943. Urgently needed were construction units, general service regiments, and dump truck companies. Requirements for such units were so heavy that it was not possible under the troop basis to provide light or heavy ponton units, camouflage, water supply, or additional topographic units. There was a critical need for a forestry company to provide timber in the forward areas and thus reduce shipping requirements. In a campaign such as that contemplated in ELKTON, to be waged in the jungles of New Guinea and the Solomons, engineer work, especially construction, would be particularly heavy during the first three months. From now on the engineers would not be able to count on civilian workmen to meet most or a large part of their construction needs. All that would be available, besides troops, would be the natives of New Guinea and the Solomons.28

Further Engineer Preparation in SWPA

By April engineer work for the coming offensive was moving ahead satisfactorily. The 2nd Special Brigade was training for its missions. On the 7th the first LCVP slid down the ways of the boat assembly plant at Cairns, and before long the men were completing six a day. The first LCMs were expected from the United States in May.29 On 17 April the remainder of the Engineer Section, Sixth Army, reached Australia and Colonel Sturgis now had a more adequate staff to help him plan for combat. As rapidly as possible the units arriving from the United States were being sent to New Guinea and were employed around the clock. In mid-April, the 46th, 91st, and 96th engineers were working on airfields, roads, docks, and hospitals at Port Moresby. The 808th Aviation Battalion, which had recently left for Sydney for rest and recuperation, was replaced by the 857th Aviation Battalion, which reached Port Moresby early in April. The 43rd engineers were continuing work on airdromes and roads at Milne Bay and Dobodura. Their effectiveness, Casey noted, had been lowered by “a high sickness rate resulting from continued hard physical activity under severe tropical conditions with much of their operations in malarial infested regions.” Two companies of the 96th were to be transferred to Dobodura and two to Milne Bay to help the 43rd. The 842nd Aviation Battalion, just arrived in the Southwest Pacific, was to go to Port Moresby to become acclimatized and to replace other units being moved to more forward areas. A heavy shop company and a maintenance company, which had recently landed in Australia and which had been urgently needed to repair equipment, were to be moved to New Guinea as soon as shipping became available. The American units in New Guinea were being supplemented by

increasing numbers of Australians. By April, four mobile works squadrons of the RAAF, about 2,000 men, were working at Port Moresby, Milne Bay, and Goodenough. In order to release some of the engineers employed in the Port Moresby area, Casey asked for 700 men of the Civil Constructional Corps to take over part of the work there. Heavy demands on the engineers elsewhere in New Guinea made such arrangements imperative. Of the organization, thirty-nine men who had volunteered for service arrived at Port Moresby in April to work for the American forces, but the Civil Constructional Corps could not send the relatively large numbers of men which the engineers needed.30

Engineer units continued to be hampered by shortages of supplies and equipment. “Considerable difficulty has been encountered,” Casey wrote to Reybold on 2 March, “in replenishing worn out construction equipment and in building up a suitable stock to take care of operational needs...” Colonel Harrison, the engineer officer expert in spare parts supply, on a tour of the theater in late 1942 and early 1943, suggested to Casey that it might be possible to obtain overhauled and rebuilt machinery from the Construction Division of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, now that building in the United States had begun to taper off. Casey wrote General Reybold, asking if there were any chance of getting a number of items urgently needed and almost impossible to procure in the theater: 25 shovels with pile driver and dragline, 18 truck-mounted cranes, 54 D-7 and D-8 tractors with bulldozers or angledozers, 12 Tournapulls, and 200 dump trucks.31 It turned out that prospects of getting used equipment were slight. On I May, Somervell informed MacArthur that it would not be “feasible to ship used equipment to overseas theaters” and that there was no rebuilt equipment on hand for shipment.32

On 21 April USASOS expanded its system of bases in New Guinea. It designated Milne Bay, Oro Bay, and Port Moresby Advance Sub-Bases A, B, and D. Six days later, USASOS set up Advance Sub-Base C on Goodenough Island. These four bases were under the supervision of U.S. Advanced Base at Port Moresby. In New Guinea, as in Australia, decentralization of authority was emphasized in order to expedite work as much as possible. The Commanding General, U.S. Advanced Base, placed responsibility for engineer construction on the base commanders, who in turn assigned to their engineers the planning and execution of the work. It was impossible, however, to find enough engineers to staff adequately the offices at the forward bases.33

Early in May, Casey and Sverdrup, accompanied by engineer and naval officers, made an inspection of the forward bases. Visiting Dobodura first, they were impressed by the amount of work which had been done there. Excellent progress had been made on the airstrips. One of the runways was surfaced with 5,000 feet of steel mat. Maj. Gen.

section of the Oro Bay–Dobodura road

Horace H. Fuller, commander of the 1st Division, joined the group for an inspection trip of the 25-mile-long road connecting Dobodura with Oro Bay. This was the road on which the Australians had begun work the previous December. The 116th and two companies of the 43rd Engineers had taken over from the Australians in February. Just out of Dobodura, the road was “in excellent condition on the long flat reach up to the Embogo River.” Beyond was a stretch of about eleven miles, “the high-level road,” which was being put through hilly country. A great deal of effort was still necessary here; excessive grades would have to be reduced, and in one area where a cut was made through an artesian well formation, better drainage was required. Engineers of the 116th and 43rd, helped by native workmen, had, Casey reported, “performed a tremendous amount of work in the construction of the high-level road under most difficult conditions of terrain and weather.” A more thorough reconnaissance of the alternate low-level route had indicated that construction there would not be as difficult as originally supposed. A road had already been put in part way to serve as a cutoff which bypassed much of the hilly section, but

it could not be depended upon during heavy rains. Casey directed that after the high-level road was finished, the low-level route be worked on to provide an alternate highway. Both roads were to be completed eventually to take the heavy traffic which would soon be moving inland from Oro Bay to Dobodura. The party found that facilities at Oro Bay were well advanced. Hastily constructed warehouses, well dispersed, provided excellent storage for the large amounts of supplies arriving daily. On Goodenough, also, Casey found that the RAAF works units had made noteworthy progress on the airfields.34

Milne Bay, from which the advance up the New Guinea coast and against the nearby islands would have to be mounted and largely supplied, presented a different picture. Construction was far behind schedule. Some work was going on at three areas on the northern shore—Ahioma, K. B. Mission, and Gili Gili—and at one area on the southern shore—Waga Waga. Farthest along was Gili Gili, where work had been started as far back as July 1942. Here were two airfields, two docks, several warehouses, and a fair network of roads. At the other areas, work was just beginning. Waga Waga was the only other place where piers had been built. Casey believed that K. B. Mission, Ahioma, and Waga Waga were excellent for base development. They had extensive, well-drained areas, ample supplies of water, and beaches with deep water close to shore, well suited for piers. There might be problems at Waga Waga, where, in some places, swamps extended half a mile inland. A major handicap was the almost complete lack of engineer troops. Only Company F of the 96th Engineers was at Milne Bay, together with some Australian troops and natives. The units which had built the airfields the year before were gone; Company E of the 46th Engineers had been transferred to Port Moresby and Companies D and F of the 43rd Engineers to Dobodura and Oro Bay. Most of the Papuans at Milne Bay were working for the Australians; 2,500 of them were building facilities for the Australian Army, but only 250 had been assigned to the Americans. Malaria reduced the effectiveness of troops and natives further. Shortages of equipment and materials were serious. Casey, in a radio to Sutherland on 9 May, recommended that the principal advance base be located at Ahioma and that the K. B. Mission area be developed for staging troops. He emphasized the need for sending in more engineer units. USASOS was hard pressed to find additional troops; it had practically none to spare.35

At the time of Casey’s visit, the prospects were dim that the base would be ready to support combat operations by early June. Colonel Sturgis was greatly concerned over the slow rate of progress. Members of his staff, having made a reconnaissance of Milne Bay in mid-May, reported that much additional work was necessary. On 26 May, General Krueger, with the approval of MacArthur, ordered an advance echelon of Headquarters, Sixth Army, including

Colonel Sturgis with a staff of thirteen officers and men, to go to Milne Bay to help with the development of the base. The advance echelon reached Gili Gili the next day. Borrowing a launch from the base commander, Sturgis, with part of his staff, cruised along the northern shore, stopping off at K. B. Mission and Ahioma for a closer look at sites for docks, warehouses, camps, and staging areas. A number of units, recently arrived from the United States, were rushed to Milne Bay; included were the 339th General Service Regiment, the 198th Dump Truck Company, and the 445th Heavy Shop Company. The 46th General Service Regiment, a USASOS unit, was put under Sixth Army control; on June, the second battalion and Company B arrived at Milne Bay from Port Moresby. The next day, Sturgis directed that a staging area for 10,000 men be ready east of Ahioma by the 15th of the month. Required were clearing the jungle, putting in access roads, wharves, and water supply points, and erecting buildings for an advanced command post. By 5 June, 2,824 engineers and 700 natives were cutting out patches of jungle, building piers, and erecting native-type structures. It was slow work. Shortages of supplies, especially of piling, were extreme. Sturgis had the natives cut mangrove; the logs, some of them seventy-five feet long, made excellent piling and could also be used for decking. Engineer blacksmiths cut and shaped spikes from lengths of concrete reinforcing rods. The rains were almost continuous, and vehicles became hopelessly mired on the primitive roads, which, for the most part, paralleled the beaches and streams and meandered through swamps. “It was common,” the historian of the 46th Engineers wrote, “to see three D-8 tractors stuck in the same mud hole.” Meantime, Sturgis readied two advance detachments, one under Col. Orville E. Walsh, the other under Lt. Col. William J. Ely, to go to Woodlark and Kiriwina about a week before the assault and select good landing areas, locate sites for airfields, and find possible routes for roads.36

Despite growing efforts being made in New Guinea, Australia remained the major base in the Southwest Pacific, and an extensive construction program was still under way there. On 30 June 1943, 48,000 civilians were at work on military projects—an all-time peak. An impressive amount of building had been accomplished. Over 300 airfields had been provided, from unpretentious grass strips without facilities to large airdromes with four or five paved runways. (Map 13) The Allied Works Council reported having built or reconditioned 4,621 miles of road. The Queensland Island Defense Road was finished, and about two-thirds of the North-South Road from Alice Springs to Larrimah had been surfaced with bitumen. Hard surfacing of the road from Larrimah to Darwin was in progress, and sealing of the road from Mt. Isa to Tennant Creek was nearing completion. Work had been finished on storage for gasoline—174 tanks with a capacity of 110,092,000 gallons had been provided. The AWC had built hospitals in all the states and Northern Territory. The largest one,

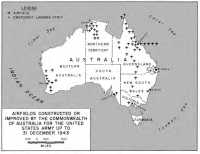

Map 13: Airfields constructed or improved by the Commonwealth of Australia for the U.S. Army up to 31 December 1943

the Temperate Zone Hospital at Herne Bay in Sydney—being built for the American forces—was to be finished by September, and the slightly smaller Holland Park Hospital in Brisbane, likewise being built for the U.S. Army, was also to be finished that same month. Millions of cubic feet of warehouse space had been provided, and construction was still going on. Again, the largest project under construction was a group of forty-seven warehouses being built for the American forces at Meeandah, near Brisbane. (Map 14) The program of camp construction was vast, particularly in Queensland. The harbors of Townsville, Darwin, Fremantle, and other cities were being dredged and their port facilities improved. The Brisbane graving dock was more than half finished. Excavation for the dock at Sydney was complete. The largest maritime project was the transshipment port being built at Cairns for American forces at an estimated cost of ,£3,500,000, work on which was just getting under way by the end of June. Cairns harbor was to be dredged, wharves totaling more than a mile were to be built, almost 100 warehouses were to be erected, and 15 miles of road and 10 miles of railroad were to be put in. When finished the trans-shipment

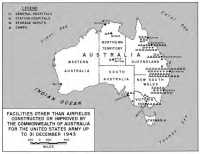

Map 14: Facilities other than airfields constructed or improved by the Commonwealth of Australia for the U.S. Army up to 31 December 1943

port would. be able to receive and distribute up to 25 percent of all supplies and equipment sent from the United States to Australia. During the fiscal year ending 30 June 1943, the Allied Works Council spent £55,961,398 for military construction. About one-third of this amount went for facilities for the American forces.37

The AWC still found it impossible to get enough workmen and equipment for its projects. As before, the jobs in northern Australia were the hardest to complete. In early June 167 major projects, costing from £6,000 to £3,050,000, were under way in Queensland and Northern Territory. The four largest, each costing more than £1,000,000, were the transshipment port at Cairns, the camp at Atherton Tablelands, the road from Mt. Isa to Tennant Creek, and the road from Alice Springs to Larrimah. On 12 June, Theodore wrote to Air Marshal George Jones, Chief of the Air Staff, RAAF, that the council was “experiencing the greatest difficulty in providing sufficient plant, materials and manpower to enable ...

works [in Queensland and Northern Territory] to be completed within the period asked for by the Services, and it is safe to say that there are few, if any, works in these areas which are proceeding at the desired rate.” As exasperating as the lack of manpower and the shortages of supplies was the transportation bottleneck. On 12 June there were 3,775 tons of supplies piled up at Brisbane, Townsville, and Sydney awaiting shipment to projects in the northern part of the continent.38

Procedure for construction, already involved, became still more elaborate—partly the result of the establishment of the additional commands. After Headquarters, USAFFE, was set up, it was empowered to approve all requests for construction before USASOS could forward them to the various Australian-American committees, a procedure instituted principally to curb requests from the Army Air Forces. Moreover, headquarters of both Sixth Army and Fifth Air Force first reviewed all requests from their lower echelons before submitting them to USAFFE for approval. In April 1943, USAFFE directed that all requests for construction in the service areas, whatever their cost, be submitted for approval, if construction required building a new installation or expanding an existing one in order to increase the scope of operations.39 Considerable confusion resulted. Many base section commanders would not authorize any construction without first getting a decision from higher headquarters. Dissatisfaction with “red tape” grew. Some kind of action was required to simplify procedures.40

Little could be done to expedite procedures on the Australian side. The Commonwealth authorities insisted on reviewing all requests for construction from the U.S. Army for which Australia, from its limited resources, had to provide workmen and materials. The Australian authorities studied each request to determine if it was in line with MacArthur’s operational and strategic plans and made surveys to ascertain whether Australian facilities were already available. They reviewed all requests for construction of permanent type installations to determine if the standards of construction were in harmony with those of the Australian services. The Australians agreed that confusion and red tape existed; the remedy, they said, was not to change the system but to operate it more efficiently. They complained that full details, plans, and estimates for American projects were not furnished soon enough. Casey stressed the need for prompt submission of the necessary data. But in other respects, the system would have to go on as before.41

The South Pacific by Midyear

In the South Pacific Area, construction in the rear areas, except in Fiji, was largely complete by mid-1943. There

was little left to do on the islands of the ferry route. In New Zealand, the camp, depot, and hospital near Auckland had been finished in April. The drilling for oil, resumed in May, had been discontinued after about two weeks when it appeared fairly certain that no oil would be found,42

The engineer aviation battalions had initially been assigned to the Services of Supply in the South Pacific. In January 1943 the Thirteenth Air Force was activated, and shortly thereafter the XIII Air Force Service Command. The latter was responsible for the administration and operations of engineer aviation units. The first unit was transferred on 19 April. The remote location of many units and poor communications resulted in a great deal of local autonomy. On many of the outlying islands, the aviation engineers were supervised by the base engineer, and they remained under his supervision. On the islands more centrally located—New Caledonia, New Hebrides, and Guadalcanal—the Air Forces took direct responsibility for the administration and operation of engineer aviation units. On such islands as New Caledonia and Fiji, the aviation battalions were largely responsible for the building of airfields. In the combat zone of the Solomons the Navy directed airfield planning and construction, and work on the fields was done for the most part by the naval construction battalions and Marine engineer units. Army engineer aviation battalions did such minor work as extending and maintaining runways, constructing housing and storage, and building roads.43

By 30 June there were 145,443 United States Army troops in SOPAC, of whom 13,434 were engineers. In SWPA, U.S. Army troops at this time numbered 176,254, of whom 23,909 were engineers. The Southwest Pacific, with a more extensive engineer organization, had four major engineer offices, one each for GHQ, USAFFE, USASOS, and the Sixth Army. The Australian military engineer organization worked closely with the U.S. Army Engineers. In the South Pacific during the first months of 1943, there was but one overall Army engineer office—that of Colonel Beadle in headquarters of the Services of Supply at Noumea. On o June, Beadle reconstituted the theater Engineer Section, which had been discontinued the previous December. The new section had 2 officers and 2 enlisted men. As Engineer, USAFISPA, Beadle was henceforth responsible for formulating policies with regard to Army engineer activities in the theater, advising General Harmon on engineer matters, and coordinating Army engineer work in the theater. Col. Lacey V. Murrow took over from Beadle as engineer for the Services of Supply; his staff numbered 2 1 officers and 53 enlisted men. Even with their expanded setup, the engineers of SOPAC had nothing like the engineer organization of SWPA.44

Operations Instructions for CARTWHEEL

General MacArthur issued operations instructions for CARTWHEEL on 13 June. There were to be three major drives. The most extensive assaults were assigned to General Blamey. American and Australian troops under his command were to seize a large part of northeastern New Guinea. Advancing by air, land, and sea, they were to capture Salamaua. Lae, the Markham Valley, and Finschhafen. They were then to prepare to seize, by airborne, overland, and shore-to-shore operations, the northern coast of New Guinea, including Madang and its surrounding area. Meanwhile, elements of Sixth Army under General Krueger were to seize Kiriwina Island and, using South Pacific forces, were to capture nearby Woodlark. Airfields were to be constructed on both islands. South Pacific Force under Halsey was to take Japanese-held areas in the central Solomons and hold off enemy air and naval forces operating from bases in the northern part of the island chain. As soon as possible USASOS was to develop advance bases in the parts of New Guinea to be taken from the Japanese.45

The engineers would have to make a maximum effort to insure the success of CARTWHEEL. They would have to support the combat forces by constructing airfields, roads, ports, warehouses, camps, and hospitals in the forward areas and by furnishing technical assistance in connection with the building of field fortifications. If necessary, they would have to fight as infantry. Most construction would have to be done in eastern New Guinea. In the jungles of that part of the island the engineers would have to improve the existing airfield at Bena Bena and build a new one at Tsili Tsili. In the Markham Valley, their chief task would be enlargement of the airstrip at Nadzab, followed by the construction of a second strip nearby. They would have to enlarge the airfields and port facilities at Lae and improve the road from Lae to Nadzab and extend it to the Leron River. They would have to construct oil storage tanks at Lae and pipelines from there to the airfields in the Markham Valley. On hand to do all this work would probably be, by D plus 30, 2 airborne aviation battalions for Tsili Tsili, 3 aviation battalions for the upper Markham Valley, and 6 aviation battalions, one depot platoon, one heavy shop company, one maintenance platoon, two equipment companies, and one engineer shore battalion for Lae and the lower Markham Valley. Engineer units under Sixth Army would meanwhile do construction on Kiriwina and Goodenough as requested by the Air Forces, and on Woodlark in accordance with specifications furnished by the Commander, South Pacific Force. For these operations the Southwest Pacific theater was to furnish 2 aviation battalions, a general service regiment, and RAAF units; the South Pacific, a naval construction battalion. Of first priority on each island was the construction of a landing strip with dispersals. In the Solomons, Navy and Marine units would undertake major combat and construction missions, supported by Army engineer units. In the Southwest Pacific, USASOS engineers

would begin base construction as soon as the Japanese had been cleared from a newly won area. The commanding general of USASOS was directed to push completion of facilities on the Cape York Peninsula, and at Port Moresby, Dobodura, and Milne Bay. He was to put special emphasis on building up Milne Bay, as this was to be the major supply base in southeastern New Guinea. General Blamey was to begin the development of the base at Lae at the earliest possible time and was to get reinforcements from USASOS for that purpose. As soon as the tactical situation permitted, USASOS would be made responsible for developing the base.46

CARTWHEEL Combat Engineers on New Georgia

CARTWHEEL was to begin with an assault on New Georgia in the central Solomons. A task force including the Army’s 43rd Division and two Marine raider battalions had been organized for the operation. Landings were to be made at various points on New Georgia and nearby islands. The principal objective was Munda Airfield, the capture of which was to be followed by the destruction of the major concentrations of the Japanese forces. Since the islands of the New Georgia group were mountainous and blanketed with tropical forests and tangled undergrowth, the destruction of the enemy was expected to be a laborious process.

On 20 June the marines landed at the southern tip of New Georgia island, and soon thereafter Seabees began to build a fighter strip and a base for motor torpedo boats (PT’s). Ten days later elements of the 43rd Division landed on small Rendova island. On 2 July they crossed the narrow channel and came ashore on New Georgia, some five miles southeast of Munda Airfield. The engineers of the 18th Combat Battalion went in with the infantry. They first cleared beach areas and developed water points and then prepared to support the infantry in the drive toward Munda Airfield. Though the objective was not far away, it was hard to get to because of the almost impenetrable jungle, the swamps, and the skillful resistance of the enemy. The engineers had more than enough to do to clear trails, cut roads through the jungle, and build timber bridges. On 14 July a second landing was made on New Georgia at a more favorable point to the west, named Laiana. The combat engineers again supported the infantrymen in the advance. Early in July Company C of the 118th had landed on southern New Georgia. They helped the marines with base construction and destroyed enemy pillboxes with flame throwers. In mid-July this company moved to Laiana to support the advance on Munda. Meantime, a force of marines had landed on the northern coast and was moving south. Everywhere the forward movement was slow; Munda would not be easy to take.47

Construction on Woodlark and Kiriwina

There was a different story on the small islands of Woodlark and Kiriwina. Six days before the assault was scheduled, the engineer advance parties under Colonels Walsh and Ely went to the two islands, where their work in clearing and blasting obstacles from the beaches and coral reefs and removing obstructions from the trails—all of it unobserved by the Japanese—was to be of great help to the landing forces. The main assaults, made on 30 June, were unopposed, and, enemy resistance did not materialize during the operation. On Kiriwina two engineer units—the 59th Combat Company (separate), and Headquarters and Service Company and the 2nd Battalion, 46th General Service Regiment—came in on D-day, ready to begin work on docks, roads, and two airdromes. Since there were no wharves, the combat engineers, with the help of native workers, first prepared landing areas on the beaches. Because of the heavy rains and the lack of roads, the 46th Engineers, charged with airfield construction, had first of all to build roads to the two sites for the airfields. Within a few days, after a road had been completed from the landing beach to one of the airfield sites, the 46th began work on the first field. On Woodlark, as on Kiriwina, the main concern was construction. The 404th Engineer Combat Company went in with the task force. During the first few days the men had as their main jobs operating water points and opening trails through the forests and widening them into roads. On 2 July the company began work on the airfield. Since the Navy was primarily interested in Woodlark, the naval construction battalion which arrived on D-day did most of the work on the single-runway airfield. On 16 July, when the first plane put down, the landing strip was operational for about 4,000 feet.48

Amphibian Engineers in Eastern New Guinea

Simultaneously with the attack on New Georgia and on Woodlark and Kiriwina, a landing was scheduled for the eastern New Guinea coast. This, the amphibian engineers’ first combat mission, would be of crucial importance; Navy commanders in the theater, skeptical of the capabilities of the special brigades, were exerting strong pressure to have them turned into “stevedore” outfits with shore duty only.49 The amphibian engineers were scheduled to land on the night of 29-30 June at Nassau Bay, some 175 miles up the coast from Oro Bay and to miles southeast of Japanese-held Salamaua. At Morobe, 50 miles south of Nassau Bay, the 532nd Boat and Shore Regiment of the 2nd Special Brigade loaded infantrymen, artillerymen, and a few members of the 116th Combat Battalion—some 740 men all told—together with supplies and

equipment on 29 LCVPs, an LCM, and 2 captured Japanese landing barges. The small force started out in stormy weather. Rain fell continuously during the trip along the coast, and the winds churned the sea into 12-foot waves. A few minutes before midnight a landing was attempted. All the men reached shore, but 2 2 of the boats and many pieces of equipment were lost when the craft were swamped on the beach. There was no enemy resistance. The infantry soon established a beachhead; the shore engineers helped to organize the defense perimeter. The next night the Japanese attacked the beachhead on both flanks. The shore engineers, along with the infantry, fought on the southern sector. In hand-to-hand combat, in the course of which an amphibian officer and 6 enlisted men were killed, the enemy was driven off, leaving from 30 to 40 dead. The Japanese made no further attacks. The following day reinforcements and badly needed supplies began to arrive. In the latter part of July the amphibian engineers established a similar beachhead at Tambu Bay, five miles north of Nassau. Soon they were moving supplies to the new location. The men were so close to enemy positions near Salamaua that they were frequently under fire.50 “Every night our boats carried up more troops, artillery, ammunition, tractors, jeeps, and the hundred other items an army must have,” General Heavey wrote. “Every return trip brought something back; casualties, sick, mail, relieved troops.” In the course of these operations the shore engineers did considerable construction, including roads, bomb shelters, and a bridge over a stream near Nassau Bay to carry 10-ton loads. Meanwhile, combat engineers supported elements of the 41st Division and Australian troops moving up from the southwest toward Salamaua. Progress was slow. The men had to push through jungle and swamp and struggle across steep mountain ranges. Without amphibious movement up the coast, the capture of Salamaua would be well-nigh impossible.51

Airborne Engineers in the Markham Valley

Soon after operations began in the Solomons and on the New Guinea coast, they were also under way in the Markham Valley. In May and June two airborne aviation battalions, the 871st and 872nd, arrived in Australia; each had about 30 officers and 500 men. Equipment was lightweight and specially designed to be carried in C-47 transports or 15-man gliders. The heaviest piece, the tractor without its bulldozer blade, weighed about one and one-half tons. Twenty C-47’s could carry one company, fully equipped, 1,100 miles. The airborne engineers’ primary job was to land with paratroops and rehabilitate captured airdromes or to land with an amphibious force and build new landing strips quickly. Airborne engineers

could also be used to build airfields in remote, out-of-the-way places into which machinery could not be moved overland. The battalions were ideal for construction in Markham Valley. Airfields built there would enable the Allies to maintain continuous fighter cover over Lae at an early date and make possible raids on Wewak, a sizable enemy base on the northern New Guinea coast.52

The initial unit selected for work in the Markham valley was the 871st. Early in July the men trained a few days in loading equipment on C-47’s and taking it off again. A major objective was to cut down the time for unloading one plane to three minutes. Since the airborne engineers would have to rely mainly on their own resources to protect themselves against enemy planes and ground troops while working in forward areas, each company of the battalion received additional machine guns. Soon the men learned where they were going. At Marilinan and Tsili Tsili, natives, working under Australian and American officers, had for several days been clearing some old turf runways, once used by missionaries and gold miners. On 7 July a plane carrying five men of Company C, a tractor, and a mowing machine took off for Marilinan along with other planes carrying an antiaircraft battery. Two days later, the remainder of the company—about 125 men—together with equipment and supplies, was loaded on thirty planes and flown over the Owen Stanleys to Tsili Tsili. The thirty planes were unloaded and, except one, were on their way back to Port Moresby by 00, just two hours after they had first taken off. The engineers immediately began to improve one of the strips at Tsili Tsili, continuing this work until nightfall. The next day they began work with their airborne equipment on a 2-shift basis. By the end of the second day, the runway was in fair shape to take transports. The men then began work on a nearby fighter strip that Colonel Abbott, engineer of the Fifth Air Force, said he wanted as “smooth as a billiard table,” an assignment the engineers considered “a pretty big order for airborne equipment.” The men were soon working around the clock. Since the kunai was six feet high, the mowing machines brought from Port Moresby were a godsend. About 400 natives helped on the field, clearing, grubbing, and ditching. Defense was provided by two companies of Australian infantrymen “astride all the trails leading into the area.” According to intelligence reports, there were about 9,000 Japanese troops at Lae and Salamaua, some forty miles away. The engineers found conditions ideal for construction with airborne equipment. The natural drainage and bearing value of the soil were excellent. The skies were clear with no sign of rain. Company C worked alone until 21 July, when the rest of the battalion landed, after having been held back by bad weather over the Owen Stanleys. By this time the transport runway had been extended to 5,000 feet and the fighter strip to 4,600. On 26 July two fighters landed.53 “Had

you been here this morning you too would have been proud of your aviation engineers,” Lt. Col. Harry G. Woodbury, Jr., the battalion commander, wrote to Brig. Gen. Stuart C. Godfrey, engineer of the Army Air Forces.54

Progress in the Central Solomons

Meanwhile, in the Central Solomons the campaign moved ahead. By late July the troops on New Georgia were slowly closing in on Munda. Engineer support was continuous. The 118th Combat Battalion built a small boat pier at Laiana, cut roads through the jungle, and established water points. Responsible for the defense of the beachhead, the men established a peripheral defense with barbed wire and automatic weapons. At various times, both companies of the battalion went into the front lines with the infantry, using flame throwers with excellent results. Engineer machine gunners shot down an enemy plane. On 22 July the first elements of the 117th Combat Battalion of the 37th Division arrived. Part of the men served as infantry. All regular engineer work had to be carried on under fire and the threat of ambush. Bulldozer operators, to protect themselves from snipers, improvised cabs with armor plates taken from captured or beached Japanese barges. On 5 August, Munda Airfield was captured. Eight days later the first planes landed. Engineer work continued as the enemy troops were destroyed piecemeal or driven into

the interior of the island. In mid-August elements of the 65th Combat Battalion landed to help the 117th and 118th engineers in the jungles around Munda. By the 25th of the month organized resistance on New Georgia had ended.55

Henceforth, the main engineer job on the island was the building or improving of roads in support of the infantry trying to eliminate isolated pockets of resistance. Even when completed, most of the roads were merely narrow clearings through the tangled vegetation and were just wide enough to take 2½-ton trucks. Many of the routes were located by native guides and with excellent results. Because the advance of the infantry was now so rapid, the engineers found it impossible to provide drainage, not to mention surfacing. The numerous bridges and culverts required were made of local timber and discarded gasoline drums. During the rainy season, the roads became impassable; the engineers attempted to provide surfacing with coral, but the coral was too badly weathered to be suitable. Considerable corduroying was necessary. Although the rainy season lasted, as a rule, from November to May, rains occurred in the dry season too.56

Additional airfields were needed in the

A corduroy road, New Georgia, capable of supporting 155-mm. howitzers

Solomons. The question arose whether Vila Airfield on Kolombangara Island, the other Japanese-held field in the New Georgia group, was worth taking. Aerial photographs indicated it was not suitable for further development; Kolombangara was therefore bypassed, and Vella Lavella, about fifty miles northwest of New Georgia Island, was chosen for a landing. After ground reconnaissance had disclosed that the island was not held in force, Admiral Halsey decided to seize part of it in order to construct an airstrip. Vella Lavella had a mile-wide coastal plain, beyond which the ground rose abruptly to a central ridge about 3,000 feet high. Almost the entire island was heavily wooded. On 8 August, 6,000 men of the 25th Division landed on the southeast coast. Company C of the 65th Combat Battalion arrived seven days later. Principal engineer tasks included clearing landing areas and locating supply dumps. Subsequently the men worked on roads. Because of the heavy rains, the engineers had to corduroy about 10 percent of the roads they built or improved; coconut trees provided ample material for this job. Miscellaneous tasks included installation of radar, operating the engineer supply depot, and putting in floors for a field hospital.57

Work was under way on several smaller islands near New Georgia. On Arundel, Company B of the 65th began work in September on roads and piers. Coral outcroppings and potholes made road construction difficult, and considerable blasting and fill were required. Engineer equipment was too light for the rough work. If building roads was arduous, supplying water was easy. As on the other large islands, there were many springs, streams, and wells to take care of all needs. On the smaller islands, where no fresh water could be located, salt water distillation units were set up. In the New Georgia operations, the 65th did not take part in combat as did the 117th and 118th. Nevertheless, the men worked so near the infantry that they were frequently exposed to fire. They usually had to organize their own security parties for each bulldozer and, in addition, had to send patrols to the front, flanks, and rear. All told, the 65th suffered 17 casualties from machine gun and rifle fire on New Georgia.58

The benefits resulting from the operations in the central Solomons were well worth the effort made. “The results of the New Georgia Campaign almost exceeded expectations,” General Harmon wrote, “... the Munda airdrome site proved more advantageous than we had anticipated. [With] four splendid airdromes ... , all of Bougainville [was] within easy bombardment range with fighter cover.”59

Satisfactory Progress Elsewhere

Meantime, operations were progressing on Kiriwina and Woodlark. On Kiriwina a 6,000-foot coral strip was ready for emergency landings by mid-August. By the end of the month one runway was complete and work was going ahead satisfactorily on a second. At North Drome, about four miles distant, work was also progressing on the runway. The 59th engineers were providing roads and storage facilities. In New Guinea, the Allies were slowly converging on the enemy at Salamaua. The amphibious move along the shores of northeast New Guinea continued. In the Markham Valley things were going well for the airborne engineers. The work went so fast during late July and early August that numerous planes were soon stationed at this new field in the Markham Valley. Not until 15 August did the Japanese attempt to bomb the area, and then their raids were largely ineffectual. Salamaua, beleaguered since early July, was still holding out at the beginning of September, but the end appeared near.60

The Assault on Lae

Late in August elements of the Australian 9th Division and the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment began assembling at Morobe for an assault on Lae, about twenty-five miles north of Salamaua. On the evening of 3 September the task force left Morobe. The U.S. Navy used its own landing craft to transport the Australian troops; the amphibian engineers, using 44 LCVPs, to LCMs and a few miscellaneous craft, carried their own boat and shore personnel, equipment, and supplies forward. On the morning of the 4th the task force arrived offshore, twenty miles east of Lae. Three engineer amphibian officers and 12 enlisted amphibian scouts went ashore with the first wave, their job to set up beach markers and direct landing craft toward shore. The remainder of the shore engineers, landing with subsequent waves, unloaded ESB and Navy craft, helped by about 2,000 Australian troops. The few Japanese in the area put up only slight resistance; enemy air attacks were a greater danger. Japanese planes knocked out 2 LCIs (landing craft, infantry) on the beach but had difficulty in hitting the small amphibian craft. About 12 officers and men were casualties. Despite enemy interference, the shore engineers were able to unload supplies quickly, move them away from the beach over hastily constructed roads, and disperse them in supply dumps. By D plus 3 the shore battalion had the beach so well organized that operations could henceforth bc carried on in a routine manner.61 “Our part of this

operation turned out so successfully,” Heavey wrote to Col. Henry Hutchings, Jr., head of the 4th Brigade in the United States, “and our Shore Engineers proved so efficient that I think some of our disbelievers will have to have more faith in us in the future.”62 Soon the advance westward along the shore toward Lae was under way. The men found it slow going through the jungle and swamp. Conditions ashore were worse than aerial photographs had indicated, rains having turned most of the area into a quagmire. Almost all supplies had to be forwarded along the coast by the amphibian engineers.

For the Japanese entrenched at Lae there was a growing threat from the west, also. The airborne engineers had maintained their rapid progress in constructing runways at Tsili Tsili, and plans were soon under way to prepare additional strips closer to the enemy positions. On 5 September the 503rd Parachute Infantry landed at an abandoned turf strip near Nadzab, about 50 miles northeast of Tsili Tsili and 25 miles west of Lae. The same day some 200 Australian pioneers with light engineer equipment reached Nadzab, having paddled from Tsili Tsili in rubber boats down the Watut and Markham Rivers. While the paratroopers guarded the trails in the vicinity, the pioneers. quickly prepared the landing strip for the 7th Australian Division, the first units of which flew in as scheduled the next morning. The following day, Company A of the 871st landed with most of its equipment. After setting up a temporary camp, the men laid out a new and better landing strip, and then began dozing away the heavy kunai grass and leveling the ground. Enemy patrols and ground troops were only 8 miles away. A continual rumble of bombings and artillery fire could be heard from the direction of Lae and Salamaua. Expecting an enemy attack at any time, the men rushed to get the runway in shape as soon as possible. During the next two days, a brigade of the Australian 7th Division began to advance down the Markham Valley toward Lae. The engineers meantime continued to enlarge and improve the runways at Nadzab.63 Conditions were more difficult at Nadzab than at Tsili Tsili. Rains were heavy, and the light equipment was not satisfactory for the vast amount of earth moving required. But the airborne engineers’ work helped speed the advance. The Japanese on the eastern New Guinea coast were in a hopeless position. On September Salamaua was captured; four days later, Lae fell.64

Finschhafen

MacArthur had originally planned to attack Finschhafen four weeks after the fall of Lae. Since an earlier assault now appeared practicable and would undoubtedly take the Japanese by surprise, the date for the attack was moved up to 22 September. It was to be carried out by Australian forces, who were

to be moved to the area on American transports. About 500 men of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade with ten LCMs and fifteen LCVPs were to help forward men and supplies from Lae along the New Guinea coast to the landing beaches. Finschhafen was situated on a coastal plain about half a mile wide, in back of which were steep, heavily wooded mountains. The assault was made as planned two miles north of the town. The Japanese were at least partially prepared. The amphibian scouts, coming ashore with the first wave, were met by enemy troops. After helping the infantry beat off the attack, the scouts put up beach markers. Landing with the second and third waves, the shore engineers came under intermittent fire from well-concealed enemy pillboxes on the beach. The infantry soon wiped out these emplacements. When the LCTs (landing craft, tank) and LSTs (landing ships, tank) came in, the shore engineers were ready to unload them.65

The Australians easily overcame the scattered enemy resistance near the beach, and on the second day, the airstrip was captured. The town of Finschhafen, however, proved to be strongly defended and would not be taken without prolonged fighting. Japanese planes made repeated attacks on the landing beaches, especially during the first four days. The craft of the amphibian engineers, moving about or anchored in the open seas, were prime targets. As the fighting continued, the amphibians brought in supplies and equipment and evacuated casualties. They began operating a supply service between Lae and the Finschhafen beaches. On 2 October, Finschhafen fell. The Japanese retreated into the mountainous region to the west of the town. Despite the retreat of the enemy ground forces, the Allied troops along the shore continued to be in constant danger of attack by air and sea.

On the morning of 17 October, an hour or so before daybreak, three barges approached one of the landing beaches. About 600 yards from shore, the occupants turned off the motors and silently rowed their craft toward the beach. An amphibious engineer happened to see the approaching craft and, alerting the American and Australian defenders, opened fire with his 37-mm. gun. One of the barges withdrew; the other two, crippled, managed to land. Ten yards away was a .50-caliber machine gun position manned by 19-year-old Pvt. Junior N. Van Noy and his loader, Cpl. Stephen Popa, both of the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. Van Noy, a skilled gunner, held his fire until the Japanese had lowered the ramps and started to jump ashore. An enemy grenade, landing in the gun position, badly mangled one of Van Noy’s legs and wounded Popa. Van Noy opened up a murderous fire on the Japanese, who tried to annihilate him with flame throwers, rifle fire, and grenades. Few of the other guns on the beach could be trained on the landing party, and, because of the darkness, the gunners were largely forced to fire blindly. In the course of the fighting, Popa was evacuated. Van Noy, heedless of calls to get

back to a defense line being formed a hundred yards to the rear, remained in his pit and continued to fire point-blank at the enemy, now bent on wiping out his position. An Australian rifle platoon moved to the beach to mop up the Japanese. Van Noy was found dead from numerous wounds, his last round of ammunition fired. Estimates were that he killed at least half of the 39 enemy troops who had come ashore. “Van Noy’s gallant action,” an Australian observer wrote, “gained time for all troops to get into position to repel the landing and undoubtedly saved lives,” an opinion shared by the Australians and Americans alike at Finschhafen. Van Noy was awarded, posthumously, the Medal of Honor, the highest award for bravery given by the United States Army.66

Airfields in the Interior of New Guinea

During September the engineers continued work on the airfield at Nadzab, concentrating on the construction of a second runway. During October they worked chiefly on graveling and asphalting a third strip. They employed several hundred natives, who cleared camp sites, unloaded aircraft, and worked on the runways, sorting rock and spreading gravel by hand. Although designed as fair-weather strips and gravel-surfaced only, the first two runways constructed at Nadzab remained serviceable in all kinds of weather and required little maintenance in the following months. Meanwhile, the airborne engineers had begun a third major airfield at Gusap in the far northwest part of the Markham Valley, near the source of the Ramu River. After the area had been reconnoitered in September, the decision was made to develop an all-weather airfield including complete servicing and repair facilities and runways to handle zoo transports daily. Early in October an advance party of the 872nd laid out the landing strips and taxiways. Later that month, the entire unit arrived and began work. By mid-November, a 6,000-foot gravel-surfaced runway was almost finished. Arriving at Gusap in November, the 871st Battalion supplemented the efforts of the 872nd. In December, a 5,000-foot section of the initial strip was given an asphalt surface, the fair-weather strips, previously cleared by the 872nd, were maintained and repaired, and a number of buildings well erected. At Gusap the men were fortunate in that they could build comfortable quarters for themselves. For their mess halls all companies erected portable huts with concrete floors. They had screened buildings with walls of lumber and roofs of canvas for their dispensaries and recreation rooms. These were almost unheard of luxuries in the out-of-the-way reaches of New Guinea.67

Bougainville

The final operation in the Solomons in which the engineers participated was the

one on Bougainville. The largest island in the chain, Bougainville, for the most part mountainous and jungle covered, had swampy coastal plains. The assault was to be under the direction of I Marine Amphibious Corps. The 3rd Marine Division was scheduled to go in first, followed by the Army’s 37th Division. On 1 November, the marines landed at Empress Augusta Bay on the western part of the island. Naval construction battalions began work on a base and an airfield. A week later a combat team of the 37th Division, including elements of the 117th Combat Battalion, came in. During their first two days ashore, the engineers cut supply trails through the jungle east of the Koromokina River so that the infantry could be supplied. Late in November they put a 3-span all-traffic bridge across the river in five days. The 117th engineers gained considerable experience in building roads through virgin jungles. Using bulldozers and explosives, the men first cleared a strip a hundred feet wide. Next, shovels and “cats” scooped out drainage ditches ten feet wide and up to ten feet deep on either side of the planned 30-foot road. Under the top soil, about one foot thick, was volcanic sand, which proved to be adequate for surfacing. The sand was excavated, piled up on the road, and then leveled by bulldozers and graders. Dump trucks were not necessary. By 15 December the engineers had completed most road construction. On that date responsibility for operations on the island passed from the Marine I Amphibious Corps to the Army’s XIV Corps. A service command was organized for Bougainville, and engineer work thereafter was directed by it. Additional engineer units were scheduled to arrive to begin work on a sizable base.68