Chapter VII: The Far North

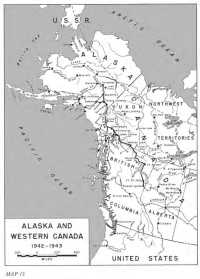

The outbreak of war with Japan brought the northwestern part of the North American continent very much into the foreground. The disaster at Pearl Harbor meant that the United States had lost naval control of the northern Pacific. It was not known whether the Japanese would attack Alaska, or, if they did so, what size force they would use. The defenses of Alaska would have to be strengthened insofar as it could be done without detriment to the buildup in more vital theaters of war. Engineer operations in the Territory were expanded. At the same time the engineers were called upon to construct projects in northwestern Canada to strengthen Alaska. Soon after the outbreak of war they were directed to build a road—the Canada-Alaska, or Alcan Highway—to link Alaska with the United States, and they were directed to develop the oil resources on the Mackenzie River—a project known as Canol. (Map 15) The Japanese attack on Dutch Harbor in June 1942 and the seizure of Attu and Kiska increased fears that Alaska was in danger and made engineer construction appear even more urgent. The threat was not entirely removed until the Japanese were driven from the Aleutians in mid-1943. In retrospect, the alarm over the danger seems much exaggerated, but to many at the time it seemed very real. Much of the construction at first glance appears to have had little to do with the war against Japan. Yet the fact remains that most of it in all probability would never have been undertaken had the United States not been at war with that country. Because of the war with Japan, the Engineers had to do extensive work in a region with which just a few years previously they had been little concerned.

Strengthening Alaska’s Defenses Plans for Alaska

After Pearl Harbor General DeWitt, who, as commander of the Fourth Army and of the Western Defense Command established in 1941, was responsible for the defense of Alaska, estimated that the Territory might be subjected to surprise attack and, possibly, invasion. He wanted more ground troops and an immediate increase in the number of planes. Washington authorities in considering his demands did not believe Alaska to be in imminent danger. But the possibility that the Japanese might launch an attack could not be ignored. On December the Western Defense Command, including Alaska, was made a theater of operations. The alert of late November was intensified. No new construction was contemplated, but the War Department directed speedy completion of approved or planned projects

Map 15: Alaska and Western Canada

that were considered urgent. In December a number of jobs, some of them under review since July, were quickly approved. Improvements were to be made at Ladd, Elmendorf, Annette, and Yakutat. All airfields, including those built by the Civil Aeronautics Authority, were to have storage for aviation gasoline and tor bombs and ammunition. Army posts were to be enlarged. The camp for the Army garrison at the CAA field at Nome was almost finished; similar facilities were to be built at nine other CAA fields. Eleven of the aircraft warning stations were to be completed. At long last, work was to be started on an airfield and Army post on Umnak; on 9 December Reybold got the signal to go ahead with this construction, which DeWitt had been urging since July. The two fields which CAA was planning to construct on the Alaska Peninsula at Cold Bay and at Port Heiden were to be built by the Army. At all installations dispersion and concealment, hitherto largely ignored, were to be stressed. Refinements, such as family quarters for married officers and fencing around military installations, were to be eliminated. The estimated cost of construction as of 31 December was approximately $90 million. Various projects of benefit to the Army would be undertaken by civilian agencies. The Department of the Interior was getting ready to improve the Richardson Highway, and the Public Roads Administration was preparing to build or improve other roads. The Department of Commerce planned to hard-surface the CAA runways.1

The expanded and accelerated construction program meant a great increase in the workload of the engineers. Lt. Col. George J. Nold as engineer of the Alaska Defense Command and Major Talley as area engineer would have far greater responsibilities than before. The Seattle District under Colonel Dunn would likewise have much more to do. At the close of 1941 there were in Alaska Company D of the 29th Topographic Battalion at Seward, the 32nd Combat Company at Fort Richardson, the 802nd Aviation Battalion at Annette, the 807th Aviation Company at Yakutat, and the st battalion of the 151st Combat Regiment, elements of which were at various Army posts from Dutch Harbor to Fairbanks. Contractors for the Navy were building the posts for the Army garrisons at Sitka, Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor. Projects not being built by troops or Navy contractors were the responsibility of the Seattle District. Most of this work was being done by hired labor. Colonel Dunn had made no large contracts, except the one with the West Construction Company for work on the railroad cutoff. More troops and civilians were urgently needed.2

Shortages

It was difficult to get either troops or civilians for Alaskan projects after Pearl Harbor. Enlistments and the draft cut

deeply into the supply of civilian manpower; deferments were as a rule not granted to men who wanted to work in the Territory. Governor Gruening believed more use should be made of local residents. In his opinion, salmon fishermen and packers, unemployed because of war conditions, would make good construction workers. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes suggested that the 4,000 prospectors in the Territory, many of whom owned construction equipment, could be of help. The Seattle District, while glad to take any qualified residents, could not draw appreciable numbers of workmen from sparsely inhabited Alaska. Because of the great distances and poor transportation, it would, as a rule, have been more of a problem to assemble a working force within the Territory for a project than to send one in from the United States. Local civilians could not always be relied upon to stay on the job. Some of the fishermen who had been hired were planning to quit when the fishing season began in the spring. With the outbreak of war, many workers from the United States wanted to return home. Even if they could be persuaded to renew their contracts, most insisted on interim vacations. Neither local nor imported civilian labor could fill the need. The shipment of more engineer troops was imperative, but few could be spared for Alaska. The first unit to arrive after Pearl Harbor was the 2nd Battalion of the 151st Combat Regiment, which reached Cold Bay in January. The next was the 42nd General Service Regiment, the first battalion disembarking at Juneau on 28 February, and the second reaching Cordova in the middle

of March. After Pearl Harbor, almost all jobs west of Fort Richardson except those at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor were assigned to troops. To ease the manpower shortage, some work was done by troops of other arms and services under engineer supervision.3

A persistent problem was the shortage of materiel. Almost all supplies and equipment had to be procured in the United States. Before January 1942, Colonel Park’s approval was necessary for all purchases; after that date, the Seattle District was permitted to buy in the open market, but this new freedom was of little value. Despite Alaska’s high priority of A-1-a, sufficient quantities of supplies could not be obtained to meet requirements. The greatest need by far was for heavy earth-moving equipment, but prospects of getting any were slight. “After Pearl Harbor,” Nold wrote later, “we were practically limited to the equipment we had in hand or could obtain locally. ...” All such machinery was kept going around the clock and used under very unfavorable conditions. Tractors churned through mud, snow, muskeg, salt water, and sandy beaches. Many of the operators were inexperienced or untrained in handling equipment under such conditions. Repairs were constantly necessary, and there were no maintenance units in the Territory. Spare parts were scarce. Not enough came in with the

machinery, and follow-up shipments were inadequate. Units had to maintain their equipment as best they could. Efforts were made to cut down on needs; projects not essential to the war effort were discontinued. Local resources were exploited insofar as possible—particularly lumber. Yet it was difficult to curb extravagance. Talley recalled that a number of post commanders insisted on requisitioning “tapered steel flagpoles in a land of tall timber” where “it was only necessary to select and cut a spruce of any height you might desire.” The steel poles were not delivered.4

The shortage of ships, severe enough in the months before Pearl Harbor, was now much more pronounced. Dunn’s office estimated that demand for cargo space would be four to six times as much as that of the last months before the war. As needs grew, the number of ships fell off. Oceangoing vessels that might have been available were put on more distant overseas routes. Fishing boats which had been leased would have to be returned to their owners when the season opened. Deliveries to Alaska were slowed by the threat of Japanese submarines in Alaskan waters; vessels were forced to travel in convoys or to go by way of the Inland Passage. Dunn did what he could to keep supplies moving northward. He rented such barges and tugs as he could find. But, on the whole, the number of ships on the Alaska run could not be increased. More effective use would have to be made of what was available. Early in 1942 the Seattle subport was made an independent port of embarkation to serve Alaska primarily. Increasing quantities of supplies were sent by way of Prince Rupert in Canada, the first and most important of the subports established in western Canada and southeastern Alaska, and activated on 6 April 1942. Shipping stocks to that port via Canadian railways meant a saving of 600 miles in water transportation. Supplies for Alaskan projects began to accumulate on the docks and in the warehouses at Seattle. Some way would have to be found to get them to Alaska.5

Engineer Construction

Despite handicaps, work moved ahead on strengthening the defenses of the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutians. Dutch Harbor and nearby Fort Mears, and installations on the Alaskan mainland as well, had nothing between them and Japan but the ocean and a string of unfortified, largely uninhabited islands. As soon as construction was authorized at Umnak and Cold Bay, Dunn prepared to ship equipment and supplies. The greatest secrecy was maintained. Materials shipped from Seattle to the airfields were marked to indicate they were to be used by private firms for building fish

canneries. On 18 January, sixty-four officers and men of the 807th Aviation Company arrived at Umnak from Yakutat. Since the island had no harbor facilities, supplies were landed at Chernofski Bay on Unalaska to the east and barged twelve miles across the strait. This job was not easy. The repeated loading and unloading of equipment caused a great deal of breakage, and some of the barges sank in the stormy waters. It was not the best time of year for airfield construction. Bulldozer operators, trying to level off a runway on Umnak’s treeless wastes, were sometimes lost for hours in blinding snow storms. Work also began on the Alaska Peninsula. When, in early February, the second battalion of the 151st Combat Regiment reached Cold Bay from the United States, it took over construction of the runway from the CAA. Here, also, the subarctic winter greatly slowed work. More rapid progress was made on Umnak with the arrival of more troops. By mid-March the entire 807th, now an aviation battalion, was working on the airfield, and by the end of the month, helped by men from the infantry and field artillery, the battalion had finished a landing strip of steel mat. The first plane came in on the 31st. By this time a strip was in at Cold Bay, but its surface was soft and full of ruts. No construction had been started at Port Heiden, reported by Colonel Park, visiting Alaska late in March, as “still frozen in.”6

Drastic measures were needed to get supplies to Alaska. Toward the end of March, Dunn estimated that by the fall of 1942 some 150,000 tons of materials would be piled up on the Seattle docks awaiting shipment. Completion of important construction during the summer would be impossible. Dunn proposed an ambitious plan. He suggested sending barges loaded with supplies and equipment up the Inland Passage to Juneau. Seagoing vessels would be taken off the Seattle-Alaska run and assigned to Juneau to ply back and forth across the Gulf of Alaska. The haul of oceangoing vessels carrying cargo to western Alaskan ports would be greatly shortened. On 28 March, Dunn proposed building a barge terminal at Cape Spencer near Juneau, complete with covered and open storage. It would be an expensive undertaking, but unless it were done he did not see how urgent materials would reach Alaska in time. DeWitt was enthusiastic. On L5 May, Somervell gave his approval and the Seattle District began to prepare plans for construction. Meanwhile, additional barges were put into service and began carrying materials to Juneau.7

Problems of Organization

Some of the engineers’ difficulties in the Territory resulted from an apparent conflict in War Department directives. Before the outbreak of war, the right to

authorize construction had been reserved to the Secretary of War. Soon after Pearl Harbor the War Department had directed DeWitt to undertake emergency work on his own responsibility. Directives for construction now came from Washington and from DeWitt. In February the War Department suspended DeWitt’s authority to initiate emergency work, and DeWitt assumed that henceforth he could not start any projects without approval from Washington. On I March the War Department made General DeWitt solely responsible for construction and real estate in the Alaskan theater of operations. Henceforth, the responsibility of Colonel Dunn and, after 15 April, of his successor, Col. Peter P. Goerz, to the Chief of Engineers for work in Alaska was limited to flood control and the improvement of rivers and harbors. The Seattle District, however, continued to do work of a technical and administrative nature for all Alaskan projects. It still prepared designs, made up fiscal, accounting, and cost statements, and took care of civilian personnel matters. The district also continued to purchase supplies and equipment. In the words of Colonel Park, “Though our authority is theoretically nil, our responsibility remains about as before.”8

Further changes in organization were made. On May, DeWitt made the Army commander, Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr., entirely responsible for the execution of military construction in Alaska. Buckner’s headquarters absorbed Talley’s office in Anchorage, and Talley’s title was changed to Officer in Charge, Alaska Construction. Although Talley was now directly under Buckner, his office was not consolidated with Nold’s. No overall organization had been set up in Alaska to repair and maintain buildings which had been completed and turned over to post commanders. In May three colonels, sent from the Corps of Engineers’ Mountain Division office in Salt Lake City to investigate the matter, found a pressing need for repair and maintenance. Two were assigned to Buckner’s headquarters as liaison officers. They began to recruit qualified civilians in the United States and searched for enlisted men to do repairs and utilities work at Alaskan stations. Some delays had heretofore resulted because project engineers lacked authority to initiate construction. Frequently they had to hold up work of even minor scope for months while awaiting approval from Talley’s office, Buckner’s office, the Seattle District, or General DeWitt. Now authority was partly decentralized. After May area engineers could build projects costing less than $20,000 without reference to higher authority, and they could start those costing up to $50,000 without getting prior approval from higher authority.

While a great deal was done to improve organization, little could be done to increase the number of troops or civilians. Only two engineer units arrived during the spring. In March the 639th Engineer Camouflage Company reached Fort Richardson and began construction of a

depot for the newly established Eleventh Air Force. In May the 813th Engineer Aviation Battalion arrived to begin work on satellite fields for Elmendorf. By June, approximately 4,500 engineer troops and 3,000 civilian workmen were in the territory.9

Construction Progress

The engineers could show considerable progress by June. Annette and Yakutat were virtually complete. Cold Bay had a good gravel runway which, while not finished, tvas usable. No work had as yet been done at Port Heiden because of bad weather. Since their arrival in February, the 42nd Engineers had been building camps for the Army garrisons at the CAA fields at Juneau and Cordova. Facilities for gasoline storage were being erected at major airfields, At all projects the engineers were putting in access roads. By the end of May drilling of the tunnels for the railroad cutoff was about half finished, and work on the roadbed was about one-fourth done. With the beginning of spring the strategically important Seward Peninsula began to receive more attention. In March and April Air and Engineer officers made a reconnaissance of that area for a site for an airfield away from the coast where weather conditions would be better than at Nome. A site was found sixty-five miles to the north of the city. In May several groups from Talley’s office made a 3-week air and ground survey of the almost unknown region west of Fairbanks in an effort to find a route for a highway or railroad from Fairbanks to the coast and a site for an ocean terminal. The preliminary investigation indicated a route along the Yukon Valley would be feasible. Two locations were found on the Bering Sea deep enough for port construction.10

Progress on the eleven aircraft warning stations approved for construction was disappointingly slow. Differences of opinion still existed over where some of the stations should be located. In March the Eleventh Air Force wanted, at its major bases, additional information and filter centers to receive signals from and transmit signals to nearby detector stations. Work was further retarded when a new type of radar detector was developed that permitted 360-degree coverage. Buckner believed 20 of these would be required, but the War Department would allow only to; after plans for installing to of the devices had been prepared, only 5 turned out to be available. Work on the aircraft warning stations, most of them in isolated places, was difficult. At some, cableways had first to be built so that supplies could be brought up. At most stations, the Alaskan winter slowed construction; at four, work was impossible before spring. By the beginning of May only the mobile

station at Anchorage and the fixed one at Kodiak were in operation.11

Concentrating on the Aleutians

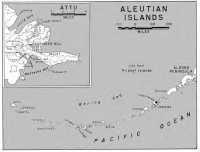

The attack on the Territory, which many had regarded as almost inevitable, was soon to come. Early in May Navy intelligence learned that the Japanese were planning to strike at Midway and the Aleutians. On 3 June two enemy carriers launched their planes for an attack on Dutch Harbor. (Map z6) Despite the bad weather 17 aircraft got through to their target, demolishing barracks and killing about 25 men. On the afternoon of the next day about 30 planes came in and again caused some loss of life and considerable damage to installations. Eight men of Company C of the 151st Engineer Combat Regiment were killed. After the attack some of the enemy airmen chose a rendezvous point near Umnak almost directly over the airfield, of whose existence they were unaware. Here U.S. fighters shot down 4 enemy planes. Meanwhile, two Japanese occupation forces approached the Aleutians. On 7 June one landed on Attu, the most remote island of the chain, and the next day the other came ashore on Kiska. As soon as enough planes could be concentrated on the strip on Umnak, bombing of the Japanese foothold on Kiska began.12

Although the Japanese thrust at Alaska, as is now known, served mainly as a feint, preliminary to the major strike against Midway, General DeWitt saw in it the possible beginning of a full-scale invasion and suggested to the War Department on 14 June that an expedition be launched against the Japanese in the western Aleutians. DeWitt’s recommendations evoked no enthusiastic response. As far as the Joint Chiefs were concerned, there were more urgent combat theaters than the North Pacific. DeWitt then proposed that an airfield be built on Tanaga Island, about 200 miles east of Kiska, so that the Japanese-occupied islands could be effectively bombed. No time was lost in making a reconnaissance. Talley, together with an Air officer and a Navy officer, landed on Tanaga on 27 June. They found the island to be similar to Umnak and estimated that a runway could be built in three weeks. But the Navy preferred Adak, 60 miles farther east, because of its good harbor. Whichever site was chosen, the engineers would have a formidable construction job. The islands of the Aleutian chain extended south-westward for 1,100 miles. Peaks of a partially submerged mountain range, they were treeless and much of the time shrouded in fog. They were uninhabited; the natives, about 1,300 Aleuts, of Eskimo stock, had been evacuated by the U.S. Navy after the attack on Dutch Harbor. Those on Attu and Kiska had been removed by the Japanese. During the summer the Joint Chiefs ordered airfields put in on Atka and Adak, and on small St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea, 300 miles north of Umnak. Airfields on these various islands would

Map 16 Aleutian Islands

provide a fairly effective harrier against Japanese air fleets operating from carriers or from Attu and Kiska.13

Work began first on Adak. Having completed its job on Umnak, the 807th Aviation Battalion, less a company which had begun work at Port Heiden, was scheduled to start the new undertaking. At Unalaska, the men assembled a motley collection of some 250 craft, including tugboats, barges, fishing scows, and a four-masted schooner, to take them to their new destination. They were to go with the task force which would occupy the island. On 26 August, the engineer “fleet,” escorted hy five destroyers, headed into the Bering Sea in the teeth of a rising gale. The crews worked hard to keep their supplies from being washed overboard. A route well up into the Bering Sea was taken to avoid enemy aircraft and submarines. During the night some vessels became separated

from the convoy, and the destroyers had a busy time locating and bringing back the wanderers. One barge was lost. After five days, Adak was sighted. Destroyers and boats headed into Kuluk Bay on the island’s eastern shore, just as a heavy fog closed in. Several of the barges were beached and some of the tractors and light cranes unloaded. The tractors dozed sand ramps to two scows sunk in tandem to provide access to an oceangoing barge being used as a floating dock. Troops, bivouacked in tents, found living conditions extremely uncomfortable.14

The mountainous island seemed to have no good location for an airfield. The sand dunes along the shores of Kuluk Bay appeared promising but would require much more earth moving than could be done with the small amount of machinery on hand. Beyond the dunes was a low, flat area of firmly packed sand, about two miles long. Along the western edge flowed Sweeper Creek, which emptied into Kuluk Bay through a narrow gap in the dunes just to the south of the flat. Tidal waters which entered through the mouth of the creek covered the area twice a day. If the tide could be shut out and, at the same time, the waters of the creek controlled, a strip could be provided quickly. On September the engineers, after bulldozing dikes along the banks of the creek, dozed a sand dam across its mouth to shut out the tide. To keep the pent-up waters from overflowing the dikes, they gouged a new channel into the bay through the dunes, two and one-half miles from the creek’s original mouth. On o September the sand strip could take a B-18 bomber. In order that planes might operate more effectively, 3,000 feet of landing mat were laid down. On the 13th forty-three planes took off to bomb Kiska. A second runway was ready five days later. To allow water accumulating in the lower reaches of the creek to escape, bulldozers had to break open the dike across the mouth of the creek daily. To eliminate this repeated opening and closing, culverts with gates were installed. Sometimes the accumulated water flooded the runways, especially when rainfall was heavy during high tide, and the gates had to remain closed. The airmen, ignoring shallow flooding, would take off in a cloud of spray. In November water pumps arrived and were put in operation later that month. In dry weather, the sand was kept moist and stable by means of controlled pumping.15

In September construction began on Atka and St. Paul. On the 17th Company A of the 802nd Aviation Battalion came ashore on Atka near an abandoned fishing village of some fifteen buildings. The men took over a number of the empty structures. As the dock was too small, the engineers provided a temporary pier by turning a barge upside down at the water’s edge. They were soon at work leveling nearby sand dunes for an airstrip with mat surfacing. Work was soon well in hand on Atka; two days after Christmas a 3,000-foot runway was ready. One company of the 42nd General

Service Regiment reached St. Paul late in September, its job to build a fighter strip surfaced with steel mat. The men found a deserted village of fifty-five buildings. Some of the 1,400 officers and men of the garrison were sheltered in the houses, with about one-third living in winterized tents. On 14 November the runway, surfaced with volcanic ash, was completed. From this time on, little work could be done, for blizzards, occurring almost daily, filled the roads with drifts so high that equipment could not get through. Rough seas and masses of floating ice destroyed or damaged almost every boat and barge moored to the island.16

Alaska: July–December 1942

During the last half of 1942 the engineers did a substantial amount of work on the defenses of the Alaskan mainland. They undertook additional construction at Ladd and Elmendorf, most of it to house more troops. During the summer elements of the 176th General Service Regiment arrived to build camps for garrisons at the remaining CAA fields in the interior of Alaska. At the naval air stations, Seabees took over from the contractors and finished the facilities for the Army garrisons. The runways were in at Cold Bay and Port Heiden by the end of the year. At long last, work had got under way on the seacoast batteries. Before Pearl Harbor, Alaska’s only seacoast defenses were a few 155-mm. gun batteries on Panama mounts at Dutch Harbor, Kodiak, Sitka, and Seward. Work on additional defenses authorized in late 1941 had been held up by delays in site selection and revisions in the numbers and sizes of the batteries. It was finally decided to have the Navy build the defenses at the naval bases and to have the Engineers improve the harbor defenses at Seward. The Corps made a contract with the West Construction Company for this job and work began in September. Work on the railroad cutoff was shaping up well. The 714th Railroad Battalion, men from the 42nd and 177th General Service Regiments, and employees of the Alaska Railroad were laying the tracks and the job was expected to be finished by the end of the year. A dock terminal was under construction at Whittier on Prince William Sound. Late in July the War Department authorized going ahead with the barge terminal which Dunn had advocated in March. Plans called for establishing a terminal for nine oceangoing vessels on the eastern shore of Excursion Inlet on Icy Straits to the west of Juneau. In August the Engineers awarded the contract to the Guy F. Atkinson Company of San Francisco. Toward the end of the month the contractor’s employees began work on piers and warehouses. In October the 2nd Battalion of the 331st General Service Regiment, about 1,300 officers and men, arrived to help the civilian forces. Meantime, the port of Juneau was being enlarged so that it could be used until the barge terminal was operational. Still far behind schedule were the air warning stations. After the Japanese defeat at Midway, previously chosen sites in the Alaskan interior and on the

west coast in the Bristol Bay and Norton Sound areas were abandoned for sites on the Alaska Peninsula and in the Aleutians. Construction plans had to be revised and work started anew.17

Interest in improving communications within Alaska heightened in the summer and fall. At the time of Pearl Harbor, Canada was building a string of airfields in the western part of the Dominion from Edmonton to Whitehorse. These fields, soon being used to fly planes from the United States to Alaska, formed part of the Northwest Staging Route. Six fields in Alaska—Northway, Tanacross, Big Delta, Ladd, Galena, and Nome—formed the other part. After the attack on Dutch Harbor, the Engineers got the task of improving the runways at the fields in Alaska. Since the fall of 1941 negotiations had been under way with the Soviet Union to fly planes from Alaska to Siberia. In September 1942 the Russians accepted the first planes via the northern route. Work on the Alaskan fields of the route, now called the Alaskan Siberian Ferry Route (ALSIB), was pushed even more, so that larger numbers of planes could be ferried to Siberia in the spring. Much thought was now given to developing ground communications westward from Fairbanks. During the fall of 1942 the Seattle District made additional surveys for a road or railroad and a pipeline from Fairbanks to the Seward Peninsula. Since building a road or railroad would take too long, a study was made of the possibility of developing river routes. Two were planned—one from Fairbanks to Tanana on the Yukon and another from Fairbanks to McGrath on the Kuskokwim. Supplies could be stored at these two points and, after the spring thaws, loaded on barges and sent down the rivers to the Bering Sea, whence they could be forwarded to various points on the Seward Peninsula. In order to have transportation out of Fairbanks as soon as possible, General Somervell in January 1943 instructed the Engineers to build the winter roads to Tanana and McGrath and develop and operate the barge lines on the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers when the ice broke up.18

Amchitka

In early November 1942 Admiral Nimitz, conjecturing that the Japanese might be planning to occupy Amchitka Island, between Kiska and Adak, advised sending an American force there to develop an advanced air base. The Joint Chiefs tentatively approved this move on 18 December, providing a good site for an airfield could be found on the island. Colonel Talley, with a party of engineers, went to Amchitka by Navy plane on 17 December, and after a 2-day survey reported finding a site on which a fighter strip could be built in less than three weeks. Accordingly, on January

1943 the first U.S. troops, including the 813th Aviation Battalion, came ashore at Constantine Harbor. The engineers, finding the flat coastal area excellent for airfield construction, began to put the strip in on a tidal flat, using the methods employed on Adak. The heavily overcast skies required the use of artificial lighting even in the daytime. Operations were not too onerous because the men had an adequate amount of heavy construction equipment. Almost daily visits by Japanese patrol planes with intermittent bombings made it highly urgent to complete the runway quickly. The first American plane landed in mid-February. Henceforth, there was only light enemy activity. Earlier that month, the 1st Battalion of the 151st Combat Regiment had arrived to construct base facilities on the island, and in March the 2nd Battalion of the 177th General Service Regiment arrived to build storage tanks for aviation gasoline. The aviation engineers meanwhile began work on the main bomber runway on a high, flat area above Constantine Harbor.19

Supplies, Equipment, and Spare Parts

By early 1943 the most critically needed supplies were reaching Alaska in fairly adequate amounts. During 1941 the Seattle District had sent 182,531 measurement tons of construction materials and equipment. In 1942, the amount rose to 585,443 tons. Still larger and speedier shipments to the Territory were possible in 1943 because of improved transportation. By the beginning of that year the expanded rail facilities at the Canadian port of Prince Rupert were being put into use. Additional docks had been built at Juneau, Seward, and Anchorage. The cutoff to the Alaska Railroad and the port of Whittier were finished by June. The barge terminal was in use. Shortages had so stimulated production of local materials that some surpluses accumulated. More lumber was being produced than was required, and Alaskan strip mines were furnishing more than enough coal. But the procurement of some items not produced locally became difficult during late 1942 and early 1943 as needs became greater and Alaska lost its relatively high priority to more active combat theaters. The short shipping season added to the troubles. Supplies for many projects west and north of Juneau had to be delivered after July and before mid-October, when the ice pack began to form. To complete a project during a given year, it was necessary to have most of the materials on hand by the previous fall. But this was extremely hard to do because of the shortage of vessels and the lack of adequate planning in the scheduling of shipments. “It was impossible,” Nold later wrote, “for agencies and authorities within the United States to visualize the necessity for ... early shipment of supplies to permit construction ... in the short working season.”20

Especially severe was the shortage of spare parts. Maintenance of equipment under adverse operating conditions was a formidable task and for the most part had to be carried out by the using units in any way they could. Soon after Pearl Harbor, Nold wanted to send the better equipment to Seattle for repair, but was informed that, if sent, it would probably be shipped to theaters with higher priorities, and no replacements for Alaska would be forthcoming. In August 1942 the 468th Maintenance Company arrived at Dutch Harbor. It took over the repair shop there, began building additional facilities, and started repairing machinery on an around-the-clock schedule. Its first job was the rehabilitation of the equipment of the 802nd aviation engineers. In January the 2nd platoon of the 468th Engineer Maintenance Company went to Adak and found that, as elsewhere in Alaska, maintenance facilities were inadequate and spare parts scarce.21

Maps

Work on the three major mapping projects started before Pearl Harbor—the making of maps of the Seward–Anchorage region, mapping the area traversed by the Richardson Highway, and making maps of the major air routes—continued. In the spring and summer of 1942 Company D of the 29th Topographic Battalion established ground control for the Seward–Anchorage region. By December photomapping of this part of Alaska was about three-fourths complete and reproduction of initial editions about one-third done. The engineers were not able to show much progress in mapping the area traversed by the Richardson Highway—an area comprising about 7,000 square miles—or with the making of maps of the major air routes, mainly because poor weather kept the airmen from furnishing adequate quantities of good photographs. By late 1942 the Aleutians were much more important than the Alaskan mainland. The principal effort now had to be concentrated on preparing maps for the troops who would eventually assault enemy positions on Attu and Kiska. The 29th Topographic Battalion at Portland, Oregon, did all the mapping for the planned operations in the Aleutians. It produced a 1:25,000 series from aerial photographs with a coverage of 1: 10,000 for critical areas. Again because of bad weather, the Air Forces found it hard to supply good photographs in sufficient numbers. The engineers had to make a large part of their maps from obliques, which were not especially suitable material for the multiplex. Meanwhile, the Army Map Service supplied copies of such maps as it had of the Aleutians.22

Camouflage

Within a few months after Pearl Harbor, a comprehensive camouflage program was authorized for Alaska, funds being allotted in excess of $6 million. Great quantities of camouflage materials

were shipped to each of the projects under way, but little effective work was done. Except for the dispersal of structures, concealment was as a rule neglected in the haste to complete construction. When the 639th Camouflage Company arrived at Fort Richardson in March 1942, it was put to work not on what it was trained to do but on the building of a depot for the Air Forces. As the likelihood of a Japanese attack increased, more attention was given to camouflage. Nevertheless, by June 1942 so much of the construction had inadvertently made the installations conspicuous that little could now be done to hide them. To make Army posts less noticeable, nets and garlands were hung and trees and shrubs replanted, and at some posts camouflage discipline was observed. In the interior of Alaska, camouflage was limited to dispersing buildings and toning them down with paint. Concealment, highly important in the Aleutians, was at the same time most difficult to accomplish. The absence of trees made effective camouflage seemingly impossible. Ingenious treatments were sometimes devised. Buildings and other installations were dug into hillsides, and the more brightly colored buildings were toned down, often with the use of mud. Driftwood, weeds, grass, tin cans, and chicken wire were used to blend structures into their surroundings. In the winter deep snow often hid installations more effectively than any camouflage could have done. On the whole, camouflage, even in the Aleutians, had very low priority; at a number of bases it was all but ignored.23

Building in Subarctic Regions

After two years in Alaska and the Aleutians the engineers had acquired considerable experience in building in subarctic regions. They had gained most of it after Pearl Harbor. Before the war engineer work, not very extensive, had been restricted almost entirely to a few points along the coast where conditions, on the whole, were similar to those in the northern United States. In the interior the engineers had worked only at Ladd, where much of the construction had already been done by the Quartermaster Corps. After hostilities began, the engineers had to build at many points in both the Alaskan interior and the Aleutians. They constructed airfields, wharves, gasoline storage, seacoast fortifications, roads, utilities, barracks, warehouses, shops, mess halls, and hospitals. Information about the various areas was scanty. Since speed was of paramount importance, there was no time to make on-the-spot investigations. “In designing facilities for the Aleutian bases,” wrote one of the men working in the Seattle District office, “interesting and perplexing difficulties were encountered, which called for every trick in the engineer’s bag.” The engineers likewise had to use many “tricks” in actual construction, both in the Aleutians and on the Alaskan mainland, in order to deal with the unusual conditions they encountered.24

One of the great hindrances was the long Alaskan winter. During this time of the year, daylight hours were few.

Engineers dressed for -37° F

For about four months, the sun shone less than eight hours a day; at Fairbanks, in December, there were three hours of sunshine out of twenty-four. In the interior, probably the greatest obstacle was the extreme cold, with temperatures from 50 to 70 degrees F. below zero not uncommon. Drums of pure antifreeze were sometimes frozen solid. The engineers used steam to soften the ground for excavating and to keep newly prepared concrete from freezing. At many Alaskan projects, they placed water and sewerage pipes on the ground in heated wooden conduits called utiladors. “The ‘Old Timers’ said work could not continue through the winter,” Talley wrote later. The engineers proved them wrong. As Talley said, “We poured concrete ... at -15° F., erected steel at -20° F. ... We stopped wooden construction sooner since the wood froze.” The 176th engineers, who worked on camps for garrisons at the CAA fields in central Alaska, had more experience than most units in living and working in the frigid Alaskan interior. At Northway “... frostbitten ears, noses, and feet were common during the first part of the winter,” the 176th reported, “but we gradually learned from the Indians and through experience how to prevent this.” The men found that keeping their feet warm was their hardest job. Shoes were soon discarded, since “any use of leather or rubber footwear was asking for trouble.” Wearing three pairs of socks and Indian-made hide moccasins helped. On one occasion, when the thermometer stood at -60° F., a group of men was sent out to cut wood, with instructions to come in when the cold became unbearable. The men stayed out for two hours. Such assignments were rare. “Only the Indians venture out in these periods and their health shows the results,” the unit historian wrote. “... approximately 90 percent ... frost their lungs and develop T.B.” At the various stations in the interior, work was usually so arranged that when the temperature fell to -35°F., the men were put on inside jobs.25

Building in areas of “permafrost” or permanently frozen ground was a new experience for most engineers. In a

large part of the Arctic and subarctic regions, permafrost, possibly a remnant of the Ice Age, was encountered from 2 to 5 feet beneath the surface of the earth and it extended downward sometimes to a depth of 1,500 feet. It was invariably found in regions where the average annual temperature was below 32 °F. Permafrost was widespread in Alaska, but there was little of it in the Aleutians. If the thin layer of topsoil which thawed in the summer and froze in the winter was removed, the permanently frozen ground underneath was left without its insulating cover. If subjected to heat, it became soft and lost its bearing power. Unpredictable results followed; the ground might shrink, crack, slide, or creep. When permafrost froze again, it produced an upward thrust. A number of buildings constructed by the engineers were heavily damaged when warm currents of air from the heated structures softened the underlying permafrost and caused parts of the structures to sink. Flowing water presented a constant hazard because it might cause the permafrost to melt. One of the runways at Ladd Field was believed to have failed because the waters of a nearby river inexplicably seeped into the frozen ground underneath the runway. Little was known about permafrost. No scientific studies of it had been made before World War II, except by the Russians as a consequence of structural failures on the Trans-Siberian railroad. Attempts to get information from the Soviet Government were fruitless. The engineers had to learn from experience how best to deal with permafrost. Before constructing buildings and runways, they had to make a thorough study of the conditions at the building site. The most effective treatment generally consisted of excavating the top layer of the permanently frozen ground and replacing it with insulating materials. Sometimes the damage caused by settling could be remedied rather quickly. At Fairbanks a well was drilled in one corner of a powerhouse through more than zoo feet of permafrost to water-bearing gravel. The passage of the water through the pipe softened the permafrost and caused the corner of the building to settle. The pumping was stopped, the soil refroze, and the settling ceased. “Thereafter,” Talley wrote, “we located wells from 00 to 200 feet away from buildings.”26

Muskeg and tundra were troublesome obstacles until the engineers learned how to deal with them effectively. Muskeg was the heavy growth of moss found in bogs, sometimes to a depth of twenty feet, and often extending many square miles in area. In many instances, the semi-decayed matter at the bottom had turned into peat; often buried in the muskeg were logs and branches. The surface was spongy. A man walking on it had the feeling of treading on a mattress. Once its surface was broken, muskeg could sustain little weight, and anyone venturing across would sink in to his knees or even deeper. Shallow patches were not a serious hindrance and neither were deeper ones, provided sufficient precautions were taken. If heavy machinery was to be moved across

Digging out tundra

muskeg, the engineers usually dumped gravel or laid mats over the route beforehand. Sometimes they built trestles over the more treacherous sections. If a runway was to be constructed or a building put up, the muskeg had to be scooped out and replaced with rock or sand. Rare on the Alaskan mainland, tundra was common in the Aleutians. Tundra was the term used by the local inhabitants for the heavy, wet, partly decayed masses of grass from two to ten feet deep. When left undisturbed, tundra could support considerable weight. Like muskeg, once its surface was ruptured, it lost its bearing capacity. It usually had to be removed so that runways and buildings could be constructed on the solid base of sand, gravel, or rock underneath. When it could not be easily taken out and extensive construction was not called for, tundra was covered with sand or gravel and would cause no further trouble.27

During much of the year, and especially from October to March, violent winds, called the williwaws, swirled over the Aleutians or sped across Alaskan

wastelands, sometimes reaching speeds of more than a hundred miles an hour. Frequently they were accompanied by heavy snow. Transferred to Adak in March 1943, the 18th Engineer Combat Regiment, although used to subarctic weather, found living on the island extremely uncomfortable. “This was the day of the Big Wind,” the regimental historian wrote under the date of 7 April. “At breakfast a man emerging from a ... tent with hotcakes in his messkit saw them take off and gain altitude. ...” By noon, men were getting lost in a raging snowstorm. By mid-afternoon it was hard to see a tent at twenty-five yards. Walking against the wind was almost impossible. “The sleet driving against your eyeballs was extremely painful,” the writer continued. “You involuntarily turned your back and then with nothing visible but snow you started in a wrong direction.” Soon almost every tent had a whirlpool of snow forced in through even the smallest openings. A major job was to keep men and tents on the ground. Similar accounts came from other islands. At one project in the Aleutians nine men trying to reach the mess hall during a snow storm were lost for five hours. At some camps, men followed ropes stretched from one building or tent to another, though the distance was only a thousand feet. Buildings of conventional design were quickly leveled. Some caught fire from downdrafts in chimneys.28

Many projects remained virtually isolated despite efforts to improve communications. Even some near the coast were hard to reach because the shallow waters prevented oceangoing vessels from approaching closely. Much lightering and transfer of supplies was necessary. Construction materials for the airfield at Naknek had to be transferred from oceangoing vessels to barges at high tide and then towed 15 miles up the Naknek River to the construction site. After the supplies were ashore, they had to be moved across the muddy flats. Lumber needed at Bethel had to be floated 85 miles down the Kuskokwim River; gravel had to be barged down the same river for too miles. Supplies needed at Galena were brought by two small steamers and by barges which plied the distance of 435 miles down the Tanana and Yukon Rivers from Nenana, the transfer point on the Alaska Railroad. Supplies and equipment for the base at Northway were barged from Big Delta via the Tanana and Nabesna Rivers. These out-of-the-way places were readily accessible by plane, but aircraft could carry only limited amounts of supplies. And during Alaska’s frequent winter storms, the airplane was often of less use than the Eskimo’s dog sled. It sometimes took thirty days for mail from an engineer project to reach Talley’s office in Anchorage. To provide an even partially adequate road network would ‘nave been impossible. Road construction was limited principally to the areas around important installations at Fairbanks,

Anchorage, Yakutat, Kodiak, and Unalaska.29

Designs

Charged with preparing designs for buildings to be erected in Alaska, tile Seattle District was faced with unusual and sometimes perplexing problems. Designs often had to be based on scanty information supplemented by an extensive use of the imagination. The district prepared a set of “typical drawings” for airfields, buildings, docks, gasoline storage, electric utilities, and other installations which could be used as a basis for the procurement of supplies and as a guide in construction. About five hundred copies of this set were made. In Alaska these drawings usually had to be modified to make them suitable for local conditions. As long as the modifications did not affect key points, the designs were useful. The Seattle District also furnished plans for hundreds of specific installations which were built at various projects.30

Practically all work the engineers did in Alaska was in some way related to the development of a network of airfields. As a rule, runways were built according to prewar designs. If two or more were put in at one field, they were almost always crossed in the direction of the prevailing winds. Whether built in the coastal, interior, or Aleutian areas, runways, taxiways, parking areas, and

revetments were similarly constructed. Although the Seattle District designed airfields for the Alaskan interior, the engineers built only one there. This was the field southeast of Fairbanks known as Mile 26, where contractors put in two parallel 6,000-foot runways. CAA was responsible for building or improving all other runways in the interior for military use. The engineers gained most of their experience in airfield construction on the Alaska Peninsula and in the Aleutians. Here pumice stone, volcanic cinder or ash, gravel, and sand were all used for surfacing. Extensive use was made of steel mat. Concrete and asphalt were rarely used. The only runways of either type put in by the engineers were those at Annette, Yakutat, and Elmendorf.31

In the erection of buildings the emphasis was on speed. Prewar types of troop housing, such as permanent structures of brick and stone and mobilization-type buildings requiring skilled labor to put up, were discontinued with a few exceptions, as for example, the reinforced concrete barracks which had been started at Ladd before the outbreak of war. Troops arriving in Alaska or the Aleutians were usually housed in tents for the first few weeks or even months. Several types of housing to provide more adequate shelter, especially in winter, were developed. Among these were winterized tents, consisting of floors and sides of wood, topped with a light skeleton framework over which the 16’ x 16’ Army pyramidal tents could be placed.

Various types of prefabricated structures were developed. Among the most popular were the boxlike Stout houses, built of panels 8 feet high and 8 feet wide. Very satisfactory was the Pacific hut, the prefabricated sections of which were manufactured near Seattle, almost entirely of noncritical materials. The arched sides and roof, inexpensively built of plywood, were lightweight and highly windproof and waterproof, and could be easily assembled. Equally satisfactory was the theater of operations type, which had prefabricated panels of rough lumber and tar paper. The panels could be manufactured and assembled even by inexperienced workmen or troops to form almost any kind of building. Widely used were the Yakutat and Quonset huts. All structures had to be especially designed to make them suitable for Alaskan conditions. The thickness of structural members had to be increased, additional bracing put in, diagonal sheathings applied, and the distance between studs narrowed to reduce the possibility of damage from the wind. Sidings almost invariably had to be put on all important buildings because the wind tore the tar paper off. Air exhaust systems were added to larger heating units to eliminate downdrafts in chimneys. Special chimney caps were put on stoves. Vapor barriers were built into buildings to prevent damage to insulation and interiors which might result from the high humidity. Buildings used as offices or quarters had to be provided with vestibules or storm entrances.32

In building harbor facilities, the engineers had to contend with extremely rough seas, particularly in the Aleutians. Before tackling the job of building docks, they had to put supplies ashore as best they could. The 807th aviation engineers, when they landed at Umnak, were among the first who had to deal with this problem. The heavy surf pounded the beach even in calm weather. Before barges bringing supplies and machinery across the strait from Unalaska could be unloaded, a way had to be found to keep them on the beach. At first they were held by winch cables of tractors placed well back from shore, but this kept badly needed equipment from construction jobs. Mooring lines from the barges were then attached to piles driven into the ground back from the shore line. Unloading the barges was even more difficult than keeping them near the shore, and at times almost impossible. At first, the troops unloaded their supplies by hand and put them on tracked trailers. They then installed a trolley hoist which permitted unloading even when the waves rose to tremendous heights, but this method was not entirely satisfactory because only one barge could be unloaded at a time. Three months after the first barge landed the first dock, a T-shaped affair, was near enough to completion to permit its use. The dock was built about ten feet above high tide level so that it would not be flooded by the pounding waves. Barges were tied

Constructing a Pacific hut on Kiska

up alongside and cranes hoisted the supplies directly into trucks. The dock withstood the battering of the sea, but its excessive height made unloading extremely slow. Two docks built later at a lower level were destroyed, when heavy seas floated the decking off the posts. It was found that it was easier to unload barges in the turbulent surf if they were docked perpendicular rather than parallel to the beach.33

By the beginning of 1943 the defenses of Alaska, particularly the airfields, had been built up sufficiently to make it highly improbable that the Japanese, especially after their defeat at Midway, would be able to expand their foothold in the Aleutians or launch a successful attack on the Alaskan mainland. While the engineers were strengthening Alaska and helping to prepare the Territory as a possible springboard for an offensive, they were at the same time at work on two important projects in northwestern Canada, the purpose of which was, at least in part, to strengthen Alaska. One project was the construction of the Alaska-Canada, or Alcan Highway; the other was the development of Canol.

The Alcan Highway

Plans for a Highway

For many years groups of Americans and Canadians had urged their governments to construct a highway through British Columbia and Yukon Territory to Alaska. They advocated such a project primarily for the purposes of developing the resources and promoting the settlement of those regions. In the Imo’s the United States and Canada established commissions to investigate possible routes. The Alaskan International Highway Commission, headed by Warren G. Magnusson, Congressman from the State of Washington, favored a route as near the Pacific coast as the terrain would permit. The British Columbia—Yukon—Alaska Highway Commission of Canada preferred locating the highway farther east, in the Rocky Mountain Trench. Both commissions advocated starting the highway at Prince George in east central British Columbia and terminating it at Big Delta, Alaska, a town about ninety miles southeast of Fairbanks and on the Richardson Highway. In February 1941, Anthony J. Dimond, delegate from Alaska in the House of Representatives, introduced a bill for a road through Canada to Alaska along whatever route President Roosevelt would consider best in the interest of national defense. The War Department, questioned on the military value of such a road, and believing it could continue to rely almost exclusively on ships for transporting troops, equipment, and supplies to Alaska, concluded that while such a highway might be desirable as a “long-range defense measure,” it could be justified “only under low priority.”34

The disaster at Pearl Harbor caused military planners to take a stronger interest in an overland link with Alaska. The War Plans Division now recommended building a road to provide an emergency overland supply line to isolated Alaskan outposts. Such a road could also be used to supply the airfields which were under construction as the Canadian part of the Northwest Staging Route. These fields were located at Edmonton, Fort St. John, Fort Nelson, “Watson Lake, and Whitehorse. The Air Forces were already using the partially completed runways, but flights were restricted because of the shortage of supplies and servicing facilities. In a Cabinet meeting held on 16 January 1942, President Roosevelt asked Secretaries Stimson, Knox, and Ickes to study the need for a highway to Alaska, and, if construction appeared practicable, to decide on the best route. Heeding the advice of the General Staff, the Air Staff, and the Engineer members of the War Plans Division, the three Cabinet members recommended building the road along the line of the staging fields from Fort St. John to Big Delta. Construction would begin at Dawson Creek, the end of the rail line fifty miles southeast

of Fort St. John. The Chief of Engineers would be responsible for the work. On 2 February the War Plans Division informed Brig. Gen. Clarence L. Sturdevant, Assistant Chief of Engineers in charge of the Troops Division, of its decision to build the road and directed him to submit within the next few days a plan for surveys and construction.35

General Sturdevant at once. consulted with members of his staff and with Thomas H. MacDonald, Commissioner of the Public Roads Administration (PRA). Two days later, he submitted a plan that called for building the 1,500-mile highway in two phases. First, the Engineers would push through a pioneer road. Public Roads would then transform it into a permanent road. The main obstacle to building any kind of highway would stem from the fact that there were so few points of access from which the construction forces could start working. To avoid losing any of the short subarctic working season, Sturdevant advised using engineer troops rather than taking time to assemble and organize a civilian construction force. If the troops could be moved over the frozen expanses of the north before the spring thaws made the terrain impassable and could begin work at several points at once, it might be possible to finish a pioneer road by fall. Along with construction units, topographic units would have to be moved in to reconnoiter the terrain over which the road would pass, and ponton units would have to transport men and equipment across rivers and lakes. Through the access afforded by the pioneer road, civilian contractors, working under the Public Roads Administration, would soon be able to work on many stretches and put in a permanent highway. On 14 February, three days after Presidential approval of the program, the War Department directed the Chief of Engineers to proceed with the project. Because most of the route passed through British Columbia and the Yukon Territory, the consent of the Canadian Government had to be obtained. On 26 February the Permanent Joint Board of Defense, Canada-United States, reported favorably on the project, and less than two weeks later William L. Mackenzie King, the Canadian Prime Minister, announced his government’s approval of the board’s recommendation.36

Organizing for Construction

While discussions between the Canadian and the United States Governments were under way, General Sturdevant organized a task force for Wilding the highway. In mid-February ;Col. William M. Hoge was named commander and ordered to report directly to Reybold. Two combat regiments, the 18th, commanded by Lt. Col. Earl G. Paules, and the 35th, under Col. Robert D. Ingalls,

were the first units assigned. They were to start work on the highway and, at the same time, furnish cadres for new regiments which would move up later for work on the road. On 9 March Maj. Alvin C. Welling, executive officer of the task force, arrived at the town of Dawson Creek, at the end of the rail line from Edmonton, and proceeded northward by way of the provincial road to Fort St. John, situated on the far bank of the Peace River. Here he set up a command post from which Colonel Hoge would supervise the construction of 650 miles of the highway northwestward from Dawson Creek to the town of Watson Lake. A second command post for the remainder of the route was to be set up later.37

No time was lost in moving the first troops up. Elements of the 35th Engineers under Colonel Ingalls, forming the vanguard, were on the train with Major Welling. Company A of the 648th Topographic Battalion reached Dawson Creek on the 13th, and the 74th Light Ponton Company came in the next day. The last elements of the 35th arrived on the 16th. Men, vehicles, and supplies were moved northward to Fort St. John. At this point, the Peace River was 1,800 feet wide. There was no bridge, and ice on the river ruled out ferrying men and equipment to the other bank. Speed was imperative because a warm spell made the crossing of the troops with their heavy machinery hazardous. The 35th Engineers laid planks and sawdust over the ice and drove across to Fort St. John without mishap. The men then pushed ahead over 265 miles of frozen muskeg in an effort to reach Fort Nelson before the thaws set in. A drop in temperature from 50 degrees above to 35 degrees below hardened the winter road sufficiently to permit the equipment to move forward easily. But the men suffered greatly from the cold, the bitter wind, and the roughness of the trail. Truck drivers, hauling load after load of troops and supplies, went for days with little rest. The most grueling task was driving the tractors, graders, and power shovels. Frostbitten and shivering operators approached the limits of physical endurance in “walking” their ponderous machines for 40 to 80 miles at a stretch without relief. Upon reaching Fort Nelson, the men were so exhausted from cold and exposure that they could scarcely move. On 5 April the last of the equipment crawled into Fort Nelson, shortly before the spring thaw made the trail impassable. The 35th Regiment and its auxiliary units were ready to begin work westward out of Fort Nelson.38

Meanwhile, in a formal exchange of notes on 17 and 18 March, Canada and the United States agreed to cooperate in the construction, maintenance, and use of the highway. The United States agreed to make surveys and to send in engineer troops to construct a pioneer road; to have contractors, Canadian or American, complete the highway under the supervision of the Public Roads Administration; to maintain the road for

six months after the war, unless Canada should prefer to assume maintenance of the Canadian portion sooner; and to turn the Canadian part of the highway over to Canada at the end of the war with the understanding that citizens of the United States would not suffer discrimination in its use. The Canadian Government, in turn, agreed to provide the right of way, to permit the use of local timber, gravel, and rock, to waive all import duties, sales taxes, and license fees in connection with work on the road, and to exempt American citizens employed on the project from paying Canadian income taxes.39

Early in April, Hoge, now a brigadier general, set up his second command post at Whitehorse, a point from which he would direct construction of the 850 miles of road from Watson Lake to Big Delta. On the 9th of the month, the 73rd Light Ponton Company disembarked at Skagway and during the next two weeks set up camp at Whitehorse. Soon thereafter Company D of the 29th Topographic Battalion reached the town. Meanwhile, the 18th Combat Regiment under Colonel Paules, the 340th General Service Regiment under Lt. Col. F. Russel Lyons, and the 93rd General Service Regiment under Col. Frank M. S. Johnson had sailed from Seattle. The 18th Engineers, the first to arrive, set up their headquarters at Whitehorse on the 15th and, with the little equipment they had, began work on the wagon trail leading westward to Kluane Lake. The next week the other two units disembarked at Skagway. They had none of their heavy equipment, though it was expected shortly. Weeks passed with no sign of it. In mid-May, General Hoge flew to the United States to find out the reasons for the delay. In Seattle, he came across tractors, graders, and trucks lined up on the docks and in nearby yards because too few vessels had either sufficient space to carry the machinery or booms capable of putting it aboard. To relieve the overburdened facilities at Seattle, Hoge arranged to have the E. W. Elliott Company send some heavy equipment by barge out of Prince Rupert. After mid-May prospects that the equipment would soon arrive at Skagway were brighter, and, late that month, it began to appear. A major feat was to get it from the docks to its destination. The White Pass and Yukon Railroad, an antiquated, narrow-gauge line, miles long, was the only link between Skagway and Carcross and Whitehorse, the transportation hubs of the Canadian North-west, both of them on the route of the highway. During the latter part of May the railroad, which had but twelve locomotives, was taxed far beyond its capacity to transport the machinery needed on the highway. But despite the difficulties, the equipment began to arrive for work on the road.40

The 18th Engineers, having received

General Hoge (center) with staff officers

most of their machinery by late May, continued working on the trail leading to Kluane Lake. The 93rd Engineers had about 60 percent of their machinery by the end of the month; with this and two tractors borrowed from the 18th, they began clearing a trail eastward out of Carcross toward the Teslin River, some fifty miles away. The 340th Engineers remained at Skagway till June, when they received enough trucks and equipment to make work on the highway practicable. One platoon remained at Skagway and another went to Whitehorse to do stevedoring. The remainder of the regiment went by train to Carcross,

then marched to the Teslin River, part of the way over the trail being blazed by the 93rd Engineers, and sailed up the river to Lake Teslin. The men arrived at their destination east of the lake on 18 June and started hacking out a trail. Work had also begun on the part of the route in Alaska. On 7 May, the 97th General Service Regiment, commanded by Col. Stephen C. Whipple, disembarked at Valdez, the southern terminus of the Richardson Highway. The men had brought only a few items of heavy equipment. Before embarking at Seattle they had turned in their wornout trucks and requisitioned new ones. They

Skagway Harbor

spent their first weeks in Alaska in maintaining the Richardson and Nabesna Highways. Early in June their equipment arrived, including the same trucks they had turned in, still in need of a complete overhauling. The men began working on a pioneer road from the village of Slana, on an arm of the Richardson Highway, northeastward toward the Tanana River.41

As overall commander, General Hoge found he was needed at both Whitehorse and Fort St. John for resolving many important matters regarding construction. There were neither telephone lines nor passable trails between the two towns, which were 600 miles apart by air, and atmospheric disturbances made communication by radio uncertain. To remedy the situation, Reybold late in April split the project into two independent commands, placing Col. James A. O’Connor in charge of the Fort St. John, or Southern Sector, and leaving General Hoge in charge of the Whitehorse, or Northern Sector. Watson Lake was the dividing point. Colonel O’Connor assumed command at

Fort St. John on 6 May. Both he and General Hoge reported directly to the Chief of Engineers.42

Construction Progress

In the Southern Sector little progress could be made during the first weeks. Rain and mud held up the 35th Engineers, working westward out of Fort Nelson. In May, two more units arrived, the 341st General Service Regiment, commanded by Col. Albert L. Lane, reaching Dawson Creek on May, and the 95th General Service Regiment, under Col. David L. Neumann, arriving on the 3 1st. Both units were assigned to the section between Fort St. John and Fort Nelson. The 341st bulldozed the pioneer trail through forests of alder and poplar; the 95th, directly behind, improved and maintained the completed trail. Both units had come without their road-building machinery. Of all the units on the highway, only Colonel Ingall’s 35th Engineers had arrived adequately equipped. But shortages were no major obstacle in the Southern Sector, for excellent rail connections permitted a fairly steady flow of machinery and supplies from Chicago and other centers of the industrial Midwest. More difficult to contend with was the unpredictable weather. At times, the temperature soared to 80 degrees and frozen earth turned into sticky mud. This dried up and became dust, which, under heavy rain, turned into mud again. Soon the men ran into many patches of muskeg. Insofar as possible, the route was detoured around them. Short strips proved to be unavoidable. Shallow patches were usually scooped out and filled with gravel; deeper ones were corduroyed.43

Meanwhile, Sturdevant and MacDonald prepared a plan whereby the Engineers and the Public Roads Administration would cooperate on building the road. MacDonald envisioned a smoothly surfaced highway for two-way traffic, with gentle grades and curves, built according to specifications for roads in national forests. It would normally be 36 feet wide but, where construction was difficult, would be temporarily limited to 20 or 22 feet. Local materials would be used for surfacing and for small culverts and temporary bridges. If desired, permanent structures could be put in later. Public Roads would help make reconnaissances for routing the permanent highway, but the military commanders would have the final decision on location because their mission required opening a road for military traffic as soon as possible. If time permitted, engineer troops could improve any section beyond pioneer road standards if this could be done without interfering with the contractors’ operations.44

Construction had begun before a thorough investigation of the route could be made. Considerable information existed on the sections located in Alaska and the Yukon Territory and on the section between Fort St. John and Fort Nelson, but for the remainder, almost

Trucking supplies through the mud by tractor train

all terrain data had to be gotten from small-scale, incomplete, and contradictory maps. On these, “lakes were out of position and critical elevations almost wholly useless. ... The indicated courses of many considerable rivers were largely schematic.” Promising trails used by guides and hunters often passed over swampy terrain and were serviceable only when the ground was frozen or were confined to tortuous river valleys where game was most plentiful. The men from the 648th and 29th and surveyors from Public Roads had more than enough to do during the first few weeks. Military and civilian

surveyors dovetailed their efforts in order to incorporate as much of the pioneer road as possible into the final route for the highway. Of great help were the local “bush flyers,” who knew considerably more about the terrain than most other inhabitants. Going aloft with them, Army and PRA engineers got a general impression of the lay of the land. A bright spot in the picture was that the engineers had a great deal of latitude in locating the road. Restrictions as to the right of way were not a problem.45

By early June, all engineer troops scheduled for work on the highway had arrived. Colonel O’Connor at Fort St. John had a combat regiment, 2 general service regiments, a light ponton company, and a topographic company, totaling 4,354 officers and men. General Hoge at Whitehorse had a combat regiment, 3 general service regiments, a light ponton company, and a topographic company, totaling 5,806. Auxiliary signal, finance, quartermaster, and medical troops numbered approximately 340 in the Southern Sector and 165 in the Northern. Two gaps remained in the building of the highway. One, at the extreme northern end, extended from Big Delta to Tanacross, a distance of a hundred miles. The other ran south-eastward for fifty miles from Whitehorse to Jake’s Corner, midway between Carcross and the Teslin River. It was planned to assign these stretches eventually to PRA contractors.46

In all sections, the pioneer road was pushed through in more or less the same manner. As stretches were located and surveyed, clearing crews, driving 23-ton D-8 tractors with bulldozers, smashed a corridor through brush and woods. The shallow-rooted trees of the north were easily toppled. While the lead dozer opened a pathway, others widened the clearing and shoved aside fallen trees and debris. General Hoge had originally specified a clearing thirty-two feet wide, but it soon became evident that in wooded areas a corridor two or three times as great was necessary to admit enough sunlight to dry out the ground. Clearing crews readily accomplished this additional work without excessive effort because most of their time was spent in turning and lining up for new cuts. By June the many hours of sunlight of the northern summer day made it possible to work two and sometimes three shifts every twenty-four hours. Working around the clock, crews could clear from three to four miles a day. Behind the clearing echelon, engineer units built log bridges and culverts over gulleys and small streams. Using hand tools and the versatile air compressor with attachments, a platoon could build a bridge, or a squad a culvert, in less than a day. Farther to the rear, other units smoothed the trail with scrapers and graders, corduroying where necessary. Still farther back, others widened narrow spaces, reduced the worst grades, and filled soft spots with gravel. The tactics of rapid construction depended on the use of special equipment, particularly the heavy bulldozer. Every other piece of machinery was auxiliary to this item. Strenuous efforts had been made to supply the units with plentiful amounts of equipment. Under normal circumstances, a combat or general service regiment was furnished 8 medium tractors, but on the highway each regiment was allotted 20 heavy and 24 medium tractors with bulldozers and winches. Equipment lists further included 6 12-yard carryalls, 3 motor patrols, and 2 power shovels; from 50 to go dump trucks and many other vehicles; one portable sawmill, two pile drivers, water purification sets, electrical generators, and radio receivers and transmitters. Men sent to northern

Canada and Alaska were also furnished arctic clothing, sleeping bags, and tents, as well as mosquito bars and head nets for protection against the great swarms of mosquitoes and flies which infested the northern regions in the summer.47

Back in the United States, critics were waging a vigorous campaign against the construction of the highway. Their most violent attacks were directed against the route which had been selected. After the bombing of Dutch Harbor, the project attracted unusual interest. In response to various charges, among them that the road was an “engineering monstrosity because of the muskeg swamp along the major portion of the route,” the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee held hearings in June to consider a formal probe of the matter. Witnesses appearing before the subcommittee contended that in the Southern Sector a road might be built for a few miles out of Fort St. John, but it would be swallowed up in the hundreds of miles of muskeg near Fort Nelson. The engineers had obviated most of these criticisms before they were made. They had relocated the pioneer road westward on the foothills of the Rockies and thus avoided the poor drainage along the original route. They blazed the trail on the ridges west of the Blueberry River and then east of the Minaker and Prophet Rivers into Fort Nelson. By painstaking care in routing, they bypassed a great deal of muskeg, save for scattered stretches from 200 to 400 yards in length. In the last sixty miles into Fort Nelson, where much muskeg was expected, less than four miles of it were encountered. On 17 June the Senate subcommittee recommended that no further investigation be made of construction on the Alcan Highway.48

Reconnaissance