Chapter VIII: Hawaii After Pearl Harbor

The war had begun with an attack on the Hawaiian Islands. Thereafter, other areas of the Pacific had borne the brunt of the Japanese onslaughts. The Philippines, Australia, and even the Aleutians had been in the limelight. The possibility of a Japanese assault constantly remained, however, and a great deal of work was necessary to fortify the Hawaiian chain. The Engineers not only strengthened the Islands but also built them up as a tremendous base through which passed the troops headed for the South and Southwest Pacific. At a relatively late date—November 1943—the Central Pacific began to engage in offensive operations. By this time, the Allies had advanced far along the road to Rabaul, and the enemy had been expelled from the Aleutians. Henceforth, he was to be on the defensive in the Central Pacific also.

The Engineers Organize for War

When the Japanese planes made their first attack on Oahu on the morning of 7 December tgo at five minutes before eight, a number of employees of the Honolulu District were already at work in the offices in the Young Hotel Building, at Hickam Field, and in the supply yard at nearby Ft. Kamehameha, on the southern shore of Oahu. In a broadcast sent out over Honolulu’s two radio stations soon after nine o’clock, Colonel Wyman, the District Engineer, directed all employees to report at once to their jobs or to a new headquarters being organized in the Tuna Packers cannery at Kewalo Basin on the Honolulu water front. The additional headquarters, being set up in accordance with plans prepared before the war, was expected to expedite work required for the defense of the Islands; it would function as a forward base and operate independently of the office in the Young Hotel Building, which would continue to carry on the “routine” duties of the district. By half past nine that morning, the new headquarters was in operation.1

The first hours after the attack were hectic. There was widespread fear of additional bombings; many expected an enemy landing. One of the engineers’ first tasks was to make certain that the principal runways on Oahu were operational and would remain so. The raids were hardly over when the 804th Aviation Battalion set out for Wheeler and Hickam to clear and repair the landing areas. The latter field was highly important

as it was the only one in the Islands with runways capable of taking B-17’s safely. During the evening, workmen from the district began repairing Hickam’s broken water mains and damaged utilities. Bellows also received attention. One of the 12 B-17’s that happened to arrive in Hawaii during the attack on Pearl Harbor made an emergency landing at this field; the Hawaiian Constructors that same day began lengthening the second runway so that it could take more of the B-17’s expected from the mainland within the next few days.2

Wyman believed it imperative to move the district’s advance headquarters from its exposed position at Kewalo Basin to a safer place. A trustee of Punahou, Honolulu’s exclusive and venerable private school, suggested that he move the district office into the school buildings. Located back in the hills, Punahou offered a more sheltered location, had adequate office and storage space, and possessed superior messing and dormitory facilities, a most important consideration, since civilian employees who worked at night were not permitted to travel to and from work while blackouts were in effect. The school’s authorities appeared to have no inkling of what was about to happen when, at two o’clock in the morning of 8 December, the first cars from the district arrived at Punahou’s gates. When the night watchman rushed out to learn what was going on, he was informed the engineers were taking over. During the next few hours, a stream of cars, buses, and trucks arrived on the campus. Keys not being readily available, some of the doors of the building were forced open. A number of the faculty, hurriedly called in, helped clear out furniture and equipment and made inventories of the items being removed; Monday morning found the new headquarters ready for work.3

Martial law went into effect in the Islands on the afternoon of the 7th. General Short became military governor. As stipulated in the defense plans, Colonel Lyman, the Hawaiian Department engineer, became the head of the military engineer organizations in Hawaii.4 He henceforth directed all engineering activities in connection with defense, except those under the control of the U.S. Navy. He was authorized to spend money without limit on engineer work. Wyman’s job was to help Lyman give the commanders in the Islands the defenses they needed. Specifically, he was to maintain permanent fortifications in a state of readiness, help civilian authorities keep the roads and other means of communications open, construct shelters in and around Honolulu, relieve the 804th engineers as soon as possible of the responsibility of keeping permanent airdromes repaired, and lastly, as directed by Lyman, furnish workmen and equipment to the military forces in the Islands. These various tasks got under way immediately. On the 8th

Wyman took over all building materials, supplies, and equipment, called all construction companies into service, and started constructing bunkers and extending runways at the airfields. Lyman distributed material to the troops and got work on field fortifications under way. No sooner had the engineer organization been consolidated than it was also enlarged. The transfer of the constructing quartermaster’s staff and field organization to the Engineers had been scheduled for the 16th. Short directed that it take place on the 8th. The constructing quartermaster’s 200 employees were transferred to the district. Wyman acquired from the Quartermaster Corps 63 construction contracts for work estimated to cost $12,793,942, about one-fourth of which was finished. He continued to be responsible for the efforts of the Hawaiian Constructors. They moved their main offices to Punahou, so that they could cooperate better with the district. Wyman was still responsible to the Chief of Engineers for the improvement of rivers and harbors and flood control, but such civil work not in some way pertaining to defense was now negl igible.5

Lyman, besides looking to the district for help, had made plans to use as many civilian organizations as possible. He was prepared to turn to contractors and suppliers of building materials, public roads departments, the Oahu Railway and Land Company, and the pineapple and sugarcane plantations. The plantations were of vital importance. They had extensive repair shops, sizable quantities of heavy construction equipment, and many trained mechanics. Their electric generating facilities could be tied into commercial power circuits. Each plantation was so organized and equipped that its workers could be used as corps engineer troops. Besides helping the engineers, the plantations were expected to contribute to civilian defense. The director of Civilian Defense divided rural Oahu into districts; men from the plantations were organized in each to carry out such jobs as repairing airfields, maintaining roads, railroads, and utilities, fighting fires, and rounding up saboteurs.6

Besides the district and civilian organizations, Lyman could rely on troop units. The 34th Combat Regiment, under the direction of the department commander, was already busy on roads and trails; so were the two divisional combat battalions, the 3rd and the 65th. The 804th engineers, assigned to the Hawaiian Air Force, were responsible for keeping all airfields used by military aircraft in a state of repair, until relieved by the district. The few troops on hand were hardly adequate to do the work that now had to be done, and Lyman appealed to the War Department for more units. He asked for two aviation battalions, a camouflage company, a topographic company (corps), a depot

company, and a mobile shop company.7 He pointed out that his staff was too small for the multitudinous jobs ahead. “I have been making strenuous efforts to obtain suitable officers for the engineer service,” he wrote to Reybold on 3 January, “... and I find myself blocked by inaction in Washington and cumbersome regulations.”8 He went on to say that he had few military men, Regular or Reserve, who had had much experience. Members of his staff were working from sixteen to twenty hours a day trying to “handle the great volume of Engineer work that has to be done as fast as possible because it was not done before the war began. ...” “Between overworked officers and inexperienced officers,” Lyman concluded, “the Engineer service is in a serious condition.” With the overall shortage of engineers, General Reybold could do little to fill Lyman’s request in the near future.9

An especially heavy burden fell on the district office. As military governor, Short charged Wyman with the “supervision and direction of all normal civilian engineer activities, including operation of utilities.”10 Under martial law, all employees of essential industries had to stay in their jobs. Construction machinery and materials, vital supplies, and wages were frozen. Wyman signed contracts with a joint committee made up of representatives of the Sugar Plantations and the Pineapple Growers Associations. The plantation owners agreed to make available their equipment, materials, and workers as needed. The Hawaiian Constructors were geared for war. General Short directed that all construction for the Army being done by civilian firms in the Islands be placed under the Hawaiian Constructors; the other firms would henceforth be considered their subcontractors. Many jobs were suspended while Short and his staff reviewed the overall program. For the time being, work was to continue on only the most urgent projects. Many of the contractors’ forces were switched to what were now deemed emergency jobs. Blackouts and restrictions on traffic forced the engineers to provide quarters and subsistence to men who were working in remote or barely accessible places from which they could not return home after the day’s work.11

Besides his mounting engineer responsibilities, Wyman was given a number of special jobs. He shared with the navy yard supply officer the responsibility for apportioning gasoline and other petroleum products to the armed forces and for rationing them to the public. Huge quantities of war materials and civilian goods were piling up on the piers of west coast ports for shipment to the islands. Much of the accumulating merchandise was destined for Honolulu stores for the Christmas shopping season. Wyman got the job of determining shipping priorities. He appointed a local shipping man to review all orders placed by the local stores and recommend shipment in accordance with the military

importance of the material. This complex task required a most diplomatic handling of the Honolulu firms.12 Since the Islands did not produce enough food to support the population, General Emmons, who replaced Short as Department Commander on 17 December, directed that certain pineapple and sugarcane fields be turned into vegetable gardens, which should be producing “in four months.” He put Wyman in charge of this program. The South Pacific Division office in San Francisco began to buy seeds, fertilizer, and farm machinery for the gardens. “It is evident,” Colonel Hannum, South Pacific Division engineer, wrote to General Reybold on 15 December, “that the Commanding General leans heavily upon the District Engineer and the forces under his charge.”13

Protection Against Air Raids

One of the urgent tasks after Pearl Harbor was to quiet the fears of the civilian population, which lived in dread of another air raid. A great clamor arose in Honolulu for shelters to provide at least some degree of protection. The engineers were asked to advise what kind of shelter would, on the whole, be best for the population at large. This was a question hard to answer. Since the fear of another raid was widespread, shelters which offered at least some protection against light bombs and machine gun fire would have to be provided quickly. “I would hesitate,” Lyman said, “to recommend that people stay inside their houses no matter how well reinforced ... the single or double frame walls of the residences in Honolulu offer little or no protection from shrapnel or machine gun bullets. In addition, there is the serious danger of falling debris or the ever present danger of fire. ...” Lyman recommended the digging of trenches. Most practical would be an excavation about 6 feet deep and from 3 to 6 feet wide. To give added protection against machine gun bullets and bomb fragments, the trench could be covered with timbers 2 inches thick, topped with about 6 inches of earth. A bench put in along one side would make a stay in one of the shelters more endurable. Simpler to construct would be a slit trench 4 to 5 feet deep and 20 inches wide. It would be rather uncomfortable during a prolonged raid, but since an attack would probably be by carrier-borne planes, the cruising time of which was relatively short, attacks would most likely not last long and elaborate shelters would not be necessary. On 9 December Lyman ordered trenches be dug on military posts, in parks, and near schools.14

Joseph P. Poindexter, Governor of Hawaii, requested Wyman to undertake a “program of construction for protection of the civilian population of Honolulu.”15 Major stress was to be placed on slit trenches. Emmons subsequently

directed that they be at least two feet wide and up to five feet deep. Insofar as possible, they were to be dug under trees, were to have zigzag patterns, and were to be “well away from buildings.” As time permitted, they were to be improved by widening, trimming, and removing rocks and debris, and by “planting the revetments with grass for camouflage purposes.” Two and one-half feet lengthwise would be allowed for each adult; one and one-half feet, for each child.

The Director of Civilian Defense, assigned to the Office of the Military Governor, shared with Wyman the responsibility for providing shelters. On 24 December the director added Lt. Col. G. K. Larrison, CE, to his staff. With the help of two civilian engineers, and under Lyman’s general direction, Colonel Larrison was to help provide protection for the people of Honolulu. He “borrowed” two engineers from the office of the chief engineer of the City and County of Honolulu, and soon he and his organization were working closely with the district office, using materials and workmen supplied by Wyman. Civilians, helped by some fifty volunteers from Hawaiian prisons, dug trenches in parks and on the grounds of public buildings “to provide immediate protection for the general public.”16

Many thought more adequate protection was needed. Some urged the building of shelters to withstand heavy bombs, or at least of shelters which were splinter-proof. The latter were structures which could withstand fragments from 500-pound bombs exploding fifty feet away. Required would be a concrete wall at least fifteen inches thick. There were few buildings in Honolulu with walls so sturdily built that they could withstand splinters even from 100-pound bombs. Building enough splinter-proof shelters for the inhabitants of the city would be a considerable, even impossible, task. It was ruled that splinter-proof protection was to be provided for employees of vital industries and key installations and for parts of the installations themselves. One of Larrison’s duties was to lay out, approve, and construct splinter-proof shelters in Honolulu with labor, equipment, and material furnished by Wyman. Larrison’s men built splinter-proof shelters of concrete or wood. Generally 6 feet square and 6 feet high, they were provided with benches. If possible, each shelter was placed to take advantage of the protection of trees, was at least 25 feet from other shelters, and was topped with about 2 feet of earth free from rock. Entrances to first-aid stations and hospitals were protected against shell fragments by wooden baffle walls 2.5 feet thick, filled with earth or sand.17

In case of dire necessity, the civilian population of the city was to be evacuated. Governor Poindexter directed construction of evacuation centers near Honolulu, a job which Wyman gave to the Hawaiian Constructors. Soon three centers were under construction in the Kalihi and Palolo Valleys. Structures,

of a temporary nature, were for the most part long, shed-type buildings, with individual quarters for families, together with small sheds which could be used as one- or two-family units. The camps would have public wash houses and latrines. Protective measures against air raids were generally limited to Oahu. On the other islands, the population and the few important installations were so well dispersed that little or nothing could be done to give added protection.18

Camouflage

Frantic efforts were made to camouflage important installations. Before the war, some interesting experiments had been made in concealment, but little effective work had been done to disguise telltale targets. Now the aim was to hide, insofar as possible, most, if not all, of the conspicuous structures, both military and civilian, on Oahu. The engineers used paint extensively on large buildings, canneries, oil tanks, piers, and even such a prominent landmark as famed Aloha Tower on the Honolulu water front, covering them with bizarre splotches of green and brown. Netting and garlands were used to conceal smaller targets such as ammunition dumps and gun emplacements. Many of Honolulu’s lei sellers wove and dyed the garlands and prepared the netting. Two 8-inch guns at the outskirts of a village were concealed under a dummy house. Fake planes of wood and burlap were placed in open fields to draw enemy fire. To hide, at least partially, some installations, the engineers began extensive plantings of trees and shrubbery. They bought 250,000 seedlings from the Territorial Board of Agriculture and Forestry and replanted many of them on the Punahou football field, which they had turned into a nursery. Most of the camouflage was of little value. Netting hid small buildings and dumps and concealed the entrances to tunnels, but large installations could not be disguised. No way could be found to conceal runways. In flying over Oahu, one could readily recognize camouflaged buildings and airfields.19

Military Defenses

Meanwhile, work was being rushed on strictly military defenses. To bring about some kind of order in construction, Emmons set up a list of priorities. At the head of the list was the protection of existing aircraft warning stations and the building of additional ones. Next came the construction of more airfields, complete with revetments, and the strengthening of coastal defenses. This was followed by the protection of vital public utilities, the building of shelters at the airfields, the dispersion of supplies for the Hawaiian Air Force, and the building of underground air depots. Of second priority were slit trenches for military personnel and expansion of existing hospitals. Of third priority were the construction of field fortifications, the improvement of roads and trails, and the erection of minimum housing for the troops arriving from the mainland.20

Aircraft Warning Service

At the time of Pearl Harbor, the permanent aircraft warning system was not operating. Among other things, there was a shortage of such important parts as vacuum tubes and oscillators. To give the troops experience in detection with radar, the Signal Corps had set up mobile stations on a temporary basis. By making the best use of the small number of parts on hand, the signalmen were able to have part of the warning service in operation soon after Pearl Harbor. The engineers began to splinterproof all structures at the permanent stations. Early in January General Emmons ordered the structures bomb-proofed. This meant that each site would have to have a number of subterranean rooms with a cover of at least forty feet of earth or rock for vital equipment and living quarters. At some of the stations, the 100-foot-high steel tower with its revolving antenna would have to be moved so that it would be directly over the chambers, and at all the stations a vertical shaft would have to be drilled through the rock or earth between the tower and the rooms. The district office hurriedly redesigned the stations while continuing work on them. When the equipment at the high altitude stations was tested, the sites proved to be unsatisfactory. Planes zooming in low over the water escaped detection. After the engineers had accomplished the difficult feat of building the cableway to the top of Mount Kaala, the site there was abandoned because it was too high. When the radar equipment was installed atop o,000-foot-high Haleakala it was found to be unsatisfactory for close-in detection—there was a dead space about thirty miles out. Another place would have to be found. Kokee, at an elevation of 2,000 feet, was satisfactory. Although work on the stations was progressing, it would be some time before any of them would be operating. The Signal Corps hoped to have the system in working order by midyear.21

Airfields

Work on airfields was rushed. Within a few days after Pearl Harbor, the engineers had cleared and repaired the runways at Wheeler and Hickam. At Bellows the second runway, lengthened from 2,200 t0 4,900 feet in five days, was able to take the B-17’s coming in from the mainland. The war had reversed the roles of the Army and Navy in the defense of the Islands. Until 7 December, the Army had garrisoned Oahu primarily to protect the fleet at Pearl Harbor against attack by land. After 7 December, the Islands had to rely for their protection mainly on land-based planes. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who took over from Admiral Husband E. Kimmel soon after the outbreak of war, declared this would necessarily continue to be the case because the fleet would have to fight the enemy at widely separated points and could not always remain near Hawaii. The Engineers would have to build more airfields, and not only on Oahu; now of vital importance was

the improvement of airfields on the outlying islands. Maj. Gen. Clarence L. Tinker, commander of the Hawaiian Air Force, was pressing for a speed-up of work everywhere. Wyman placed all work on airfields for which he was responsible under the Hawaiian Constructors; on 13 December, the contract with the Territorial Airport Contractors was terminated. Hickam and Wheeler continued to receive special attention. Traffic was heavy on Hickam’s runways, which had been in service for four years and were not designed to take the new heavy bombers and transports. Additional work was needed not only on runways but also on parking areas. Because of the many aircraft using the field, the runways could not be closed down for complete reconstruction; it was decided to repair the weak spots only, and to apply a one-inch coat of asphaltic concrete to keep water from penetrating through the pavement and softening the subbase. The field was kept in full operation. Bellows likewise had high priority. The airmen were pressing for completion of this field because they wanted to move some of their units from overcrowded Wheeler. The engineers pushed work on a number of additional fields on Oahu, two of exceptional importance being Kahuku on the northern tip of the island and Mokuleia on the north central coast. (Map /7) Three more were planned for the central plateau. Work was speeded up on Morse and Hilo on Hawaii and on Barking Sands on Kauai. Additional fields were to be built, even including one on small Lanai island.22

General Emmons ordered obstructions placed on all level areas over 400 feet long on which enemy planes could land or take off. “Level areas” meant primarily grazing lands and fields of pineapple and sugarcane. The Hawaiian Pineapple Company, the California Packing Company, and other firms with extensive holdings were enlisted for this work and supplied most of the workmen and materials. The companies were to make every effort to block the level areas as soon as possible, using any practicable means at their disposal. They would be reimbursed by the government. Lyman chose Capt. George E. White, Jr., of the 804th Aviation Battalion, as his representative to approve and coordinate plans and inspect the work. On many of the fields, the workers erected posts at least eight inches in diameter, stacked boxes in piles at least five feet high, or parked junked machinery. On some, they dug ditches with embankments three feet high. By mid-March all pineapple fields and 60 percent of the other likely landing areas on Oahu had been blocked, and many level areas on the outlying islands had been similarly treated. On the latter islands, major emphasis was put on rendering all airfields useless to the enemy, except those necessary for defense. The engineers placed mine chambers on the runways at Hilo airport and Upolo Field on the

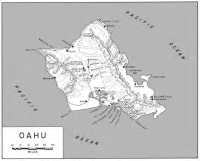

Map 17: Oahu

island of Hawaii, but did not load them. On Kauai they mined Burns Field and Barking Sands.23

Coastal Defenses

Should the Hawaiian air defenses be incapable of holding off an approaching fleet, the Islands’ next line of defense would be the guns of the Coast Artillery. Under Wyman’s direction, the Hawaiian Constructors worked around the clock on all the fixed batteries along Oahu’s southern coast. Among their main jobs were the casemating of the 16-inch guns of Batteries Hatch and Williston and the 12-inch guns of Closson. At each gun site, casemates, magazines, and store-rooms were combined into a single structure of reinforced concrete with walls twelve feet thick, which supported roofs of concrete slabs, eight feet thick. On

the east and west coasts of Oahu, workmen began to casemate the 8- and 6-inch guns, and at numerous gun sites they built projectile stands and powder storage chambers, replaced disintegrating sandbags, built splinter-proof plotting rooms, camouflaged positions, built access roads, and provided adequate utilities. Where the terrain permitted, they drove tunnels to house magazines and operational facilities.24

Soon after Pearl Harbor the engineers got an unlooked-for job. They were directed to install various types of guns which the Navy had removed from its warships and turned over to the Army for emplacement on land. On 15 February the Navy gave the Army 5-inch gun batteries, which the Coast Artillery wanted installed at four points on Oahu. Next, the Navy offered the Army 12 old 7-inch guns; 2 of these were to be installed on Oahu and 2 on Kauai. The additional armament was expected to provide many advantages. Since practically all fixed seacoast guns had been emplaced at or near the beaches, it was highly desirable to have additional large-caliber guns placed well back from the shore, preferably at an elevation high enough to assure the batteries not being overrun by small landing parties. Considerable ingenuity was required to plan layouts and prepare barbettes for these guns to ensure efficient operation on land; plans for standard batteries proved to be of little help.25 Lyman considered these jobs of gun installation so important that he directed they be carried on “day and night, seven days a week, until they [were] completed.”26

The biggest job was yet to come. In mid-December Emmons’ G-3 informed Maj. Gen. Harry T. Burgin, chief of the Hawaiian Coast Artillery Command, that there was a good chance that some of the big guns of the battleships and aircraft carriers sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor could be salvaged and emplaced on land. In numerous conferences, Army and Navy authorities discussed the practicality of the scheme. Under consideration were the 8-inch guns of the aircraft carrier Saratoga and the 14-inch guns of the battleships Arizona and Pennsylvania. On 16 January General Burgin wrote Emmons that the “Navy authorities” believed that “two 3-gun turrets, 14-inch, with all their appurtenances could be obtained and in all probability a third ... might be obtained for use by the Army.”27 Burgin’s staff began to investigate various sites on Oahu where the guns might be emplaced. Nimitz doubted that the 14-inch guns of the Arizona and the Pennsylvania could be easily installed on land; he thought the turrets with their guns too heavy. But he believed the Army could make good use of the 8-inch guns of the Saratoga. Burgin wanted both and requested Emmons to have the engineers make a survey to determine if they could be moved “to locations some 300 feet up on the ridges to the north and east of Pearl Harbor and installed in usable condition with magazines and ammunition servicing from below as ... on

battleships.”28 On the basis of the survey, made by Lyman on orders from Emmons, the engineers concluded that the transfer would be practical. The Coast Artillery decided to take both types. On 8 February Emmons directed Wyman to begin work on four emplacements for the 8-inch guns, two of them at Diamond Head and two in the pineapple fields north of Schofield Barracks. He considered this job extremely important; Colonel Robinson was to give it the “highest priority equal to flying fields,” and the engineers were to work around the clock on it.29 The 14-inch guns of the Arizona and the Pennsylvania, to be emplaced at Barber’s Point and Ulupau Head, were a different matter. It was soon apparent that their tremendous size and weight, their intricate construction, and the vast number of parts would create the most complex problems. Months of planning and preparation would be necessary before the job of moving the big guns to their sites could even begin.

Despite growing defenses, amphibious landings by an enemy force were a distinct possibility. In Lyman’s opinion, a most serious problem for an attacking force was the one of providing sufficient protective cover for the first troops to hit the beaches. Naval guns of the attacking force would have to lift their fire just as the landing craft were nearing shore; the enemy would then have to use his planes, which, to give protection, would have to fly so low that they would be

vulnerable to the defenders’ machine gun fire. To meet such tactics, defensive positions on Oahu, especially those on the beaches and in the foothills close to the shore line, were being strengthened, principally by the construction of “heavy overhead cover” which would “give adequate protection against enemy machine guns and bomb and shell fragments.”30 Little was being done or could be done to increase antiaircraft fire. Few of the coastal guns on Oahu were so emplaced that they could fire on planes. The Navy removed a few antiaircraft guns from its ships for installation on Oahu. Wyman took over this work in February.

Beach defenses had a large number of machine guns emplaced in a single line near the shore. Most were so close to the water that it was impossible to maintain effective wire entanglements at a reasonable distance in front of them, and, as a consequence, penetration of the beach line would be fairly easy. Lyman stressed the need for organizing defenses in depth. It was imperative that these defenses have strongpoints so organized that heavy fire could be placed in any direction. In addition, the defending forces should be kept as mobile as possible. In the positions already organized on hilltops, machine gun emplacements in many instances were so sited that they could deliver only plunging fire in support of the beach defenses. Many were poorly camouflaged. Lyman emphasized that emplacements should be concealed from aircraft, that beach positions close to the water should be moved inland and set up to deliver fire

in more than one direction, that the silhouettes of positions should blend with their surroundings, and that antipersonnel mines should be used extensively in the natural avenues of approach. Work was being undertaken along all these lines. At the same time boat obstacles were placed off the shores of Oahu. They consisted for the most part of railroad and streetcar rails, many of them pulled up from the streets of Honolulu, and driven into the coral sea bottom to form tetrahedrons submerged at high tide.31

Mines and Demolitions

If worst came to worst, and the Hawaiian air and coastal defenses could not halt an attacking force, mobile ground troops would have to prevent the landings and, if unable to do so, would be responsible for stopping or retarding the enemy’s advance across the Islands. Preparing roads, bridges, airfields, and buildings for demolition to slow down a successful enemy invasion would require considerable effort. Because of the Islands’ peculiar topography, the use of demolitions was a complicated matter. Normally, local commanders decided when the charges should be set off, but in Hawaii this would not be good practice because the main routes of communication were limited, and the destruction of a vital bridge during retreat, for example, might make an effective counterattack later on impossible. It was suggested that in each critical area two types of roadblock be prepared; a temporary one strong enough to hold off an initial assault, and a permanent one requiring demolition to be executed by the engineers as part of the overall tactical plan of the combat forces. Coordination of major demolitions would have to be worked out between the local commanders of the beach defenses and the combat forces. The engineers placed various kinds of obstacles and prepared demolitions. The 3rd and 65th engineers readied roads, highway bridges, and railway bridges, principally by drilling holes for explosives but, except in a few cases, they did not put the charges in place.32

Should the Japanese make a successful landing, they would probably attempt to advance first across the low-lying areas and plains of the islands. There were few natural obstacles to slow such an advance, particularly on Oahu. The central plateau had practically no trees, and, in general, streams and marshes were few. On all the islands, the defenders would have to rely heavily on mines. On 23 December Emmons asked the War Department for 160,000 antitank mines. While awaiting shipment, the engineers placed the few on hand and prepared to improvise. Howitzer shells were satisfactory substitutes but would be used only as a last resort. The engineers improvised hand grenades by filling bottles with gasoline and petroleum which would ignite upon striking a tank. Hawaii had a scorched earth plan; it would go into effect in whole or in part only upon orders of the

department engineer or sector commanders, as the case might be. All demolitions and destruction were to be total, since any supplies and equipment falling into the hands of the enemy would have to be regarded as lost in any case.33

Problems of Administration

With the avalanche of work descending on the engineer troops and the Honolulu District, it was highly important to have the most efficient type of organization. Spheres of responsibility were quite well defined: all work not performed by troops under Lyman was to be done by the Hawaiian Constructors and their subcontractors under Wyman. On 3 January, the Constructors’ organization was enlarged with the addition of the Hawaiian Contracting Company. Wyman was responsible for more than 1,000 jobs, which ranged from the building of large airfields and elaborate underground chambers for storing gasoline and ammunition to the paving of access roads and the minor repair of buildings. He issued job orders almost daily. Supplemental agreements were made with the Constructors, by which the contract was expanded to cover most of the work ordered after the start of the war. Within two months the amount of the contract rose from $15 million to approximately $75 million. Extraordinary efforts were needed to manage such a mushrooming construction program successfully.

Numerous problems arose concerning the work of the Hawaiian Constructors. In the days of frenzied activity after Pearl Harbor, projects had been assigned willy-nilly, and before long no one knew how much work the contract covered. Wyman, Robinson, and the contractor’s representatives had many conferences in which they tried to find some way of arriving at a fair estimate of the sum total of the work and its cost. Figures prepared by the Engineering Division of the Honolulu District office were based on what a lump sum contractor would probably bid on the work in peacetime, with no allowance made for the wholly unforeseen conditions arising from the war. Moreover, these estimates did not take into account the fact that work done under a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract was often more costly than if done on a lump-sum basis. To the estimates of the Engineering Division, Wyman and Robinson added o percent for the cost of mobilizing and demobilizing the working forces, another to percent for the expense to the contractor of maintaining offices on the west coast and in Honolulu, and an additional 20 percent for contingencies, including overhead costs, which were exceptionally large because of the many changes in the program. Priorities were, moreover, being continuously revised, which made it necessary to move men and materials from one project to another. Often men and equipment had to be kept on a job with nothing to do because supplies did not arrive as scheduled. Meanwhile, largely because of conditions beyond their control, the Hawaiian Constructors were being

subjected to mounting criticism for incompetence and inefficiency, not a little of it coming from the contractors who had been placed under their direction.34

Wyman had other troubles, among them his inability to resist the demands of many military commanders. Stating they had verbal authorization for their projects, the commanders insisted that Wyman get started on the work at once. Pressure was especially strong from the Hawaiian Air Force, redesignated the Seventh Air Force on 5 February. Insofar as the district engineer knew or could determine, many of the requests from the air force, and from others as well, had not been officially approved by higher authority. More confusion arose because it was not clear what the chain of command really was. The engineer organization had supposedly been consolidated under Lyman; nevertheless, Emmons gave orders directly to Wyman, and the district engineer at times attended the department commander’s staff conferences. Inquiries from Wyman to the Office of the Chief of Engineers brought rather vague replies. On 1 2 January, General Reybold radioed “Wyman is in complete charge of all construction working directly under the commanding general” of the Hawaiian Department. Reybold stressed the need for caution in accepting construction requests. He told Wyman to do “only that construction specifically authorized by the commanding general preferably in writing, but in any event in definite terms and confirmed in writing by proper authority.” But commanders in Hawaii continued to press Wyman to get started on their projects. His well-meaning efforts to be helpful to everybody only made his position more difficult.35

Supplies and Equipment

Since there was a chance that the shipping lanes from the mainland would be cut, the engineers had to give special attention to supply. Stocks for the troops, stored for the most part at Schofield and Fort Kamehameha, were dangerously low. After Pearl Harbor, Lyman began building up his reserves, particularly of fortifications materials. It was not hard to find and distribute sufficient quantities of supplies for the few engineer units assigned to the Hawaiian Department. Dealers had quite a few items. Lyman stored his new acquisitions at various points on Oahu, including the district’s yards in Honolulu. Ample numbers of civilians could be hired as clerks for sorting and distributing. Since Oahu had good roads and excellent rail lines, transportation was adequate. Already evident was the lack of spare parts and of units to distribute them. Fortunately, some spare parts could be procured in Honolulu, and requisitions for additional items were sent to the mainland. The 34th Engineers organized a stopgap parts supply unit at Schofield. The lack of maintenance units was noticeable; civilian

repair shops were called upon for help insofar as possible.36

For Wyman and the Hawaiian Constructors, with their huge construction program, supply was much more complex. Measures had to be taken immediately lest construction bog down. An engineer officer, Maj. Louis J. Clatterbos, arriving in Honolulu on 5 December, bound for Africa by way of the Pacific, was temporarily detained by the tide of war. Reporting to Army headquarters on Pearl Harbor day, he was assigned to the Honolulu District office. He arrived at Punahou at 0900 the next morning, and Wyman made him his supply officer. Hitherto a responsibility of the Operations Division, supply had not been one of the district’s most important functions; the division office in San Francisco had taken care of most procurement. Wyman directed Clatterbos to set up a separate supply division, pointing out the rapid expansion that would be necessary to meet wartime needs. Soon requisitions to San Francisco for large amounts of supplies, especially lumber, cement, corrugated iron, and camouflage materials, were being prepared. Wyman was responsible for procuring these supplies and determining the priorities in which they were to be shipped. How much material would actually arrive depended as much on how many ships were available as on anything else. Clatterbos had just gotten started on his many tasks when he left for Africa on 20 December.37

One of the district engineer’s biggest jobs was to find construction machinery and allocate it to the various projects. The plantations supplied some machinery and local contractors managed to scrape together a few odds and ends. These were makeshift arrangements. It would soon be necessary to turn equipment back to the plantations so that they could begin planting foodstuffs, and equipment would have to be returned to the contractors to enable them to “proceed with the large and complicated fortifications items.” Because of the shortage of transports, great amounts of machinery earmarked for Hawaii were piling up on the docks at San Francisco. All ships arriving at Honolulu were thoroughly searched for the equipment they might have aboard. The engineers requisitioned any new automobiles, station wagons, and trucks they could find. Under authority from Emmons, Wyman directed that practically all construction equipment which the engineers could get hold of be turned over to the Hawaiian Constructors.38

By the end of the year a start had been made in coping with major supply problems. On 2 9 December, Wyman sent his first order to San Francisco. It called for 3,740,000 dollars’ worth of materials. In January, Capt. Carl H. Trik, transferred from the Quartermaster Corps about a month before, became chief of the Supply Division. Despite the improvement in the outlook for

supply, Captain Trik had numerous difficulties. Hawaiian projects now had an A-1—a rating, but their high priority did not seem to expedite the sending of cargo. Distribution was slowed because of the poor condition of supplies when they arrived. Manifests were often garbled or were not received before the arrival of a vessel, and identification tags on boxes and crates were frequently indecipherable. Early in February Wyman set up a separate field area on Oahu to operate the base yards, shops, gas stations, and factories which served more than one field area. The district engineer, meantime, had been freed of a few of his more burdensome and rather extraneous supply chores, for shortly after the beginning of the year the Office of the Military Governor took over the rationing of gasoline and construction materials and the allocation of shipping for civilian goods from the mainland.39

A muddle developed over equipment. The Honolulu District had turned over practically all the machinery it could get to the Hawaiian Constructors. Because equipment was so scarce, Wyman wanted to buy a large part of the stocks of the Hawaiian Constructors, but they were willing to sell only if the district engineer took over everything they owned. Since there was small chance of getting enough machinery from the mainland, Wyman and Robinson thought it best to buy everything the Constructors had. Poor pieces could be repaired or used to repair other items. The engineers and the Constructors were far apart as to price. Meanwhile, spare parts shortages were causing increasing trouble.40

Real Estate

After Pearl Harbor the acquisition of real estate, a function transferred from the Quartermaster Corps, was added to Wyman’s growing list of responsibilities. The pressure of events forced the engineers to streamline procedures, particularly those for acquiring tracts for a temporary period. Under the new system, a military unit wishing a piece of land sent its request to the commanding general of the major echelon concerned. If he approved, he informed Wyman, who thereupon directed his real estate officer to acquire property. It took about six weeks to get legal possession. From December 1941 to 16 February 1942, the Real Estate Division of the Honolulu District processed some 200 cases, involving all types of transactions. The Army tried to take as few residential areas or cultivated tracts as possible. For the most part, it occupied forest preserves, pastures, and wasteland. It leased many hotels, offices, shops, warehouses, and schools. In the tense days after Pearl Harbor, numerous tracts and buildings had to be occupied without proper authorization.41

Financial Problems

The feverish efforts to build up defenses after Pearl Harbor produced

growing disorder in the district’s finances. To speed up construction, procurement of supplies in the Islands was partially decentralized. Each of the district’s fifteen field areas was authorized to purchase at least some of its supplies, and the Hawaiian Constructors were permitted to buy part of what they needed in the open market. As the number of purchases mounted, invoices and vouchers sent to the district office piled up. Not enough bookkeepers and auditors could be found for the swelling volume of paper, and effective control over the purchase of supplies became impossible. Apparently the magic words “Charge it to the District Engineer” were sufficient to get construction supplies from local dealers, who believed that defense required rapid delivery to any purchaser who appeared to be bona fide. The district’s Procurement Section often did not know what materials had been contracted for and delivered, and it was frequently not informed when orders for materials had been changed or canceled. Vouchers began coming in from department engineer units, and not always for construction materials; some were for food, lodging, or clothing, and even such extraordinary items as “medicinal liquors.” Some supplies ordered from dealers by telephone never reached their destination, yet they were undoubtedly delivered somewhere, if the more or less undecipherable signatures on the receipted invoices meant anything. One invoice came back with the notation “Received by Captain Blackjack of the Horse Marines.” Much of the confusion was the result of good intentions, of a laudable desire to cut through red tape, to dispense with the now intolerably slow peacetime procedures, and to get on with vital construction with the greatest possible speed.42

A tremendous number of bills from local merchants accumulated. Businessmen pressed the district’s Finance Section for the payment of accounts long overdue. By March 1942 the Honolulu District owed local merchants about $3 million, most of which had been outstanding since December. A number of businessmen threatened to protest to Washington, and others stated they would make no more deliveries unless the amounts owed them were paid and they were given assurance that payments for new purchases would be made within a reasonable time.43

Mounting Difficulties

The district office was so swamped with work that administrative procedures almost collapsed. The sudden expansion of the organization and the lack of clear-cut lines of authority were largely to blame. In November 1941, the district office had directed or supervised the work of about 3,500 civilians and spent approximately $1,700,000 a month. By March 1942 the number of personnel had risen to 17,000, and expenditures to $8,000,000 a month.44 Many of the thousands of newcomers were not well qualified for their jobs,

and time-consuming efforts were necessary to train them. Lt. Col. Howard B. Nurse, before the transfer one of the Quartermaster Corps’ top construction men and now Wyman’s executive officer, observed that the development of “a smooth-running, well-organized business of that magnitude requires years’in civil life.” Wyman’s place in the chain of command in the Islands remained vague, despite his efforts to have it clarified. Many local commanders in Hawaii continued to put pressure on him to expedite or finish their projects. He was under the additional handicap of being responsible for such jobs as rationing gasoline and planting vegetable gardens—somewhat unusual functions for an engineer district. Colonel Nurse believed that if Wyman had not had to assume so many extra responsibilities, he would have been “more free to pursue the usual functions of a district engineer.”45

Resentment against the Honolulu District mounted. It seemed the engineers were blamed for everything that had gone wrong, except the disaster at Pearl Harbor itself. Perhaps nothing caused a greater furor than the taking over of Punahou School. Rumors circulated that when the engineers moved in, they smashed the doors, broke the windows, dumped valuable pianos on the lawn during a rain, and unconcernedly threw out a statue of Venus de Milo, since “it was already broken; its arms were off.”46 Weeks later, some workmen, while putting up a barbed-wire fence around the school grounds, needlessly hacked down part of a superb hedge of night-blooming cereus which was “the pride and joy of Punahou, and of all Honolulu.” This led to a furious outburst, particularly from the school’s alumni, many of them prominent in the city’s business and civic affairs. “For two or three days,” wrote O. F. Shepard, the school’s president, “it seemed as if the Pacific War were a small event in comparison to the partial destruction of the cereus hedge.”47 There were reports that after the engineers had commandeered the Pleasanton Hotel, across the street from Punahou, they tossed chairs and tables out of the windows to make room for the more comfortable furniture they had taken from the swank Royal Hawaiian Hotel. A prominent resident of Honolulu reported that on one Sunday afternoon he counted thirty-five cars with district licenses, most of them “filled with women and children out joy riding.”48 Driving hard to get things done, Wyman had alienated many. The inability of the district to deal with many of its numerous problems in a satisfactory manner irritated most of those who had to deal with it. Wyman’s sometimes abrupt manner further incensed the easygoing islanders. “The District Engineer,” Lyman wrote to Reybold on 14 February, “has antagonized a great many of the local people as well as some of the new employees and officers who have recently been assigned to this office.” He went on to say, “... whenever any condition arises ... even ... if beyond

the control of the District Engineer, the people wrathfully rise up ... against him.”49 Many engineer officers concurred in these views.50 When an editorial favorable to the district engineer appeared in one of the Honolulu dailies, a reader called up the editor to find out when the district engineer had taken the newspaper over.51 This, Colonel Nurse relates, “was considered the joke of the day, and was kicked around with a great deal of glee.’’52 Even relations between Lyman and Wyman became so strained that an almost intolerable situation resulted.53

The rumors were, of course, almost entirely unfounded. The take over of Punahou was orderly with only a minimum of disturbance, and care was taken to safeguard property. Some damage was inevitable but “much ... [could] be forgiven,” the school’s president wrote, “... because of the emergency and of the confusion into which everybody was thrown.” Furniture was not tossed out of the Pleasanton, and the few items taken from the Royal Hawaiian were obtained in the proper manner. Nevertheless, the fact remains that many residents of Honolulu believed the stories and some still do. In an effort to get at the truth of the charges regarding district employees and their families out joy riding, Colonel Nurse posted eight commissioned officers one Sunday with orders to stop every military vehicle and ascertain the reason for its being on the road. Only one was spotted; its driver was on his way to Bellows Field to make some repairs on a bulldozer. When Colonel Nurse reported his findings to the “prominent resident,” the latter replied that he “was glad to hear it ... turned on his heel, and walked off without further comment.”54 In the growing controversy, the valuable work being done by the district was deliberately ignored.

Perhaps much of the clamor could have been avoided had an effective public relations program been instituted early. Before the war the Honolulu District had been a relatively small and little-known government department; the civilian population could not understand why, after Pearl Harbor, this particular organization had suddenly become so important with so many things to do so fast and on such a large scale. Many people, from lack of information, misconstrued the intentions of the engineers. President Shepard, who had a sympathetic attitude toward the district, relates that he was present when Wyman “in no uncertain terms” told Mr. Ralph Wooley, one of the Hawaiian Constructors, an alumnus of Punahou and a horticulture expert, to replant the destroyed part of the cereus hedge and make sure that no further harm was done to it. But the public was never informed

of this, and “the Colonel got all the blame for the mutilation of the hedge.” On the advice of members of his staff, Wyman eventually started a public relations program. He hired a writer to prepare a series of articles setting forth the importance of the work of the engineer district. Two appeared in one of the Honolulu dailies, the second one along with the favorable editorial. The public reaction was so adverse that the project was dropped.55

Change in Organization

For some time the War Department had been making plans to consolidate the engineer organization in the Islands more fully. Despite the reorganization made on 8 December, the explanatory letters from the Chief’s Office, and statements by General Emmons, the organization was not functioning well. On 28 February the Secretary of War wrote to Emmons delimiting the responsibilities of the commanding general in Hawaii with regard to engineer work. Emmons, as commanding general, was completely responsible for “military construction ... in the Department, including administration of existing construction contracts.”56 Within the limits set by Congressional legislation and War Department regulations he could transfer contracts of the department and the district to any command he wished. It was made clear that the district engineer was responsible to the Chief of Engineers only for work in connection with the improvement of rivers and harbors and flood control. All employees and all funds, equipment, and supplies of the district which were not included in the last categories were to be transferred to the department. Henceforth, whoever was department engineer would also be district engineer. Emmons, empowered to set the day for the consolidation, designated it as 15 March.57 Wyman was returned to the United States and subsequently was assigned to the Canol project.

Colonel Lyman became head of the Honolulu District and at the same time continued to serve as department engineer. For the first time district and department were under one head. Lyman did not try to reorganize or unite the two offices; any attempt to do so would very likely have increased the confusion. The great gain was that Lyman had under him the military engineer organization in the islands and that his place in the chain of command was abundantly clear. He would be able to advise Emmons on the best course of action from the engineer standpoint, and as a member of his staff would not be subject to direct pressure from other commanders in Hawaii. Partly of native Hawaiian descent, Colonel Lyman was a member of an old and widely known island family; a graduate of Punahou and of West Point, where he had been a classmate of General Emmons, he understood well the local temperament and made every effort to improve public

relations. Soon a marked change for the better was noticeable. There was no lessening in the urgency of the situation. The Japanese continued to enjoy naval preponderance in the Pacific and were still strong enough to attempt an assault on Hawaii.

Strengthening of Defenses Continues Under Lyman

Under Colonel Lyman, work continued on all engineer projects in the Islands. After mid-March great empHasis was put on construction for the air forces. In a conference held on the 30th of March, Emmons, Tinker, and Lyman discussed the construction effort still required. It was agreed that as regards Oahu, work on Bellows was especially urgent and that efforts would have to be speeded up on runways and housing at Mokuleia and Kahuku. At Kipapa, a new field on the central plateau, where some construction had already been done, activities for the time being would be limited to clearing cane, building runways to minimum standards, and providing housing for 225 officers and men. Greater efforts were needed on the airfields on the outlying islands. There the engineers were to remove the demolitions at Hilo and pave two of the runways. They were to pave the runways at Barking Sands as soon as they could get a hot-mix asphalt plant and transport it to the field. They were to continue construction at Homestead on the island of Molokai, the runways of which were to be surfaced with Marston mat or paved with asphaltic concrete. Work on a number of fields, including the one on small Lanai island, was canceled because the terrain and flying conditions were found to be unsuitable.58

A special type of project for the air forces was now requiring a considerable construction effort—this was the underground bombproof shop for repairing airplanes. The Honolulu District Office and Hawaiian Air Depot had started preliminary studies for such a shop early in 1941. In September General Short had asked the War Department to authorize construction near Wheeler Field; the War Department disapproved the project. Later the department reversed itself and authorized construction. General Short selected a site in a pineapple field southwest of Wheeler. Two days after Pearl Harbor, Wyman directed the Hawaiian Constructors to begin work. Since the project had the highest priority, it was soon under way. Late in February the Seventh Air Force proposed a different layout; Emmons approved, and in mid-April a new directive was issued. Plans now called for a bombproof cut and cover shop of three floors, air-conditioned throughout, with an elevator of iozqton capacity. Diesels and generators taken from obsolete submarines would serve as a power plant of about 100,000-kilowatt capacity. A concrete slab roof, 10 feet thick, under a 5-foot layer of earth was considered sufficient to withstand ½-ton bombs and at the same time would be deep enough to permit the growing of pineapples for camouflage. The entrance, in a sheer

cliff on the west side of Waiele Gulch and practically invisible from the air, was to be large enough to admit B-17s. Planes going to the repair shop would land on a runway to be built at the bottom of Waiele Gulch or would approach on ramps leading from Wheeler Field.59 By May construction was proceeding satisfactorily.

By June, the Hawaiian Islands were far more secure than they had been six months before. Airfields, coastal guns, fortified positions, antiaircraft batteries, offshore obstacles, underground shelters, and an alerted defense force would make an assault anything but easy. Lyman believed there were still certain weaknesses in the defensive system. For one thing, although the engineers had finished their share of construction on 12 of the aircraft warning stations—7 on Oahu and the rest on the outlying islands—none of the stations was as yet operating on a permanent basis, a deficiency made up to a considerable extent by the Signal Corps’ use of mobile stations. He was also perturbed by the continued shortage of mines. The Hawaiian Department had requested 160,000 on 23 December, but by June only a few thousand had been received. In Lyman’s view, large quantities were needed because of the few natural obstacles in the Hawaiian chain, and because so many airfields, close to excellent landing beaches, could be easily overrun. Yet, despite these minor deficiencies, the state of defenses could, on the whole, be considered encouraging.60

Some problems that had appeared earlier persisted under Colonel Lyman—notably shortages of equipment. Shortages existed while large amounts of machinery continued to pile up in San Francisco and Los Angeles for lack of shipping. Members of the Truman Committee, investigating the equipment situation late in March, came across large numbers of items at the Albany Race Track near Oakland that were scheduled for shipment to the Hawaiian Constructors.61 On 28 March Col. Raymond F. Fowler, assistant chief of engineers for supply, in a memorandum to the Director of Procurement and Distribution, SOS, stated, “... every effort is being made to expedite shipment of available articles to San Francisco within the next 30 days.” He explained that supplies and equipment were accumulating in California because of the scarcity of transports. “All requisitions received from Hawaii,” Fowler stated, “have at present either been shipped from available stocks or placed on expedite procurement requisition.”62 On April Colonel Hannum reported that 57,140 tons of equipment were on hand in Los Angeles and San Francisco for shipment overseas. But the shortage of ships was so great that

the materials would probably remain on the wharves for months.63

Efforts to Resolve Administrative Problems

Also persistent were the difficulties of administering the contract with the Hawaiian Constructors. By 15 May forty-three supplemental agreements had been added to the original contract. The number of projects had risen to about 1,400. It was impossible to amend the contract and make supplemental agreements fast enough to keep pace with the changes and additions to the construction program. Nevertheless, Colonel Robinson and the Constructors reached agreement as to the overall cost and the fixed fee as of mid-May—the total estimated cost of the work was $84,436,887; the fixed fee, $1,014,690.64

Criticism of the Hawaiian Constructors, growing in volume during the first months of 1942, became still louder. Colonel Lyman chose two officers and a civilian from the Honolulu District to review the question of whether the contract should be terminated. Having made their study, two of the men believed it should be; the third thought the interests of the government would be better served “by continuing the contract with clearly defined lines of responsibility and with the Government performing the function of administering and inspecting the work.” All three believed the work should not continue under the contract unless a more efficient administration and more effective cooperation between the contractors and the government were achieved. A committee made up of representatives of the Hawaiian Constructors agreed. Lyman informed the Constructors on 9 May that a “substantial revision” would probably soon be made in the handling of construction in the Islands. The contract would not be terminated, but work thereunder would be greatly curtailed. In view of the changes, bound to ensue, the program of work included in the contract and the supplemental agreements would have to be reviewed again.65

Meanwhile the district initiated action to eliminate the confusion in finances by hiring additional help to prepare vouchers for payment. It set up a special “detective” section, whose job it was to find out who had signed the vouchers with illegible and unknown signatures; in turn area offices set up their own special “detective” sections to help with this work. Lyman accepted responsibility for vouchers which indicated the goods had been delivered to military units. Trying to find out who had received the materials was often a slow and laborious process; as a rule, the search began with the questioning of the clerk or driver who had delivered the goods. But progress was made. By May the Finance Section was forwarding some 300 certified vouchers a day to Lt. Col. Herbert Baldwin, finance officer of the Hawaiian Department. Some further delays resulted because Baldwin thought

the evidence presented with some vouchers that materials had been delivered to people entitled to them was not good enough. Numerous Honolulu merchants were still of the opinion that payments were much too slow.66

Early in June the war in the Pacific took a crucial turn. In the first months after Pearl Harbor, Hawaii had not been on the list of Japanese objectives. Japan’s main concern had been to seize southeast Asia, the Philippines, and the Netherlands Indies, and, if possible, to cut the lines of communications from the United States to Australia. Having attained most of these goals in the first months of 1942, the Japanese prepared to strengthen their position still further by establishing a defense line to the east and northeast of their home islands—they would seize Midway and part of the Aleutians. By occupying Midway, Japan could extend her air coverage eastward from that island by 1,300 miles. Japanese planes could then sweep over the Hawaiian chain. In June, the Japanese successfully occupied Attu and Kiska, but their thrust at Midway met with disaster. In a battle between a Japanese task force and U.S. air and naval units northwest of Midway on 3 and 4 June, the enemy lost 4 aircraft carriers, heavy cruiser, and some 250 planes, together with 100 of his best pilots.67 The possibility of a serious attack on the Hawaiian Islands after that was considered most unlikely.