Chapter IX: After Midway

The Battle of Midway was followed by an uneasy period as work on defenses continued and base buildup was accelerated to make possible the launching of offensives. Construction needs, despite the Japanese defeat, were still great. On 14 June Emmons wrote to Somervell that $50 million more was required for work in the Islands. Much remained to be done on airfields; Hickam, especially, needed a great deal of attention, since the runways were in danger of crumbling under the continuous, heavy traffic. The Seventh Air Force was pressing for the completion of additional construction—shops, warehouses, and storage for reserve gasoline. More aircraft warning stations were needed and considerable effort was still required on seacoast defenses, field fortifications, and bombproof storage for ammunition. The growing numbers of troops called for many more camps, warehouses, and hospitals. And there remained innumerable minor jobs, such as fencing critical areas, camouflaging, splinter-proofing, and constructing and maintaining utilities. All this work required additional supplies. Some 200,000 tons were still needed—about 35,000 a month. The most pressing demands were for lumber, cement, and asphalt.1

Work on Defensive Installations Slows Down

As the weeks went by and the Army garrison increased to 100,000, the fear of invasion almost vanished and made work on purely defensive installations less urgent. Some defenses could even be eliminated. The Navy was no longer greatly interested in the seaplane basin in Keehi Lagoon. The request for large numbers of antitank mines was dropped. By July the Hawaiian Department had received 14,000, but there was no indication from Washington that any more would be sent. The need for antipersonnel mines had likewise lessened. Boat obsta.cles placed offshore lost most of their effectiveness, since the action of the waves had loosened them from their moorings, and they were removed in August.

The growing sense of security had an adverse effect on those projects still deemed important, and much of the work progressed slowly. This was particularly true of the coastal batteries. Headway on the 8-inch gun turrets, for example, was far less rapid than had been expected, and at some of the larger batteries, also, work was considerably behind schedule. One of the main difficulties at the coastal batteries was the short workday. The men had to be taken by car or bus to the job sites, some coming from as far as Honolulu. They

started work anywhere from 0800 to 0930, depending on the distance they had to travel; some quit at 1500. Absenteeism was common. Shortages of equipment, especially of power shovels, further slowed construction.2

Construction Tailored to Hawaii’s Needs

Stress was now being placed on building up Hawaii as a base to support offensives and as a staging area to move troops westward. From December 1941 to October 1942 alone, the number of Army troops in the Islands rose from 42,000 to 132,000, and the archipelago was also crowded with Navy personnel and civilian war workers. Once again, the engineers had to make as much use as possible of existing facilities, and once again, they had to revise standard theater of operations drawings to meet local conditions. In an important overseas base such as Hawaii, where structures might be needed for an indefinite period after the war, the flimsiest possible construction consistent with safety was not necessarily the most desirable. Where standard theater of operations drawings were modified, it was done to improve and strengthen the buildings and at the same time make as much use ‘as possible of local materials. In some cases the engineers even used critical materials if that was necessary to produce a more adequate building. Standard drawings prescribed earth floors for barracks and latrines; in Hawaii, the engineers installed floors of wood or concrete. The drawings prescribed waterborne sewage for hospitals only; in the Islands it was a feature of other buildings as well. Officers’ quarters had interior plumbing and lounge space not called for in the original designs.3

Among the greatest changes were those made in troop housing. The first men to arrive in the Islands had been quartered in buildings on permanent posts; soon all space was filled. Quarters of the type built before Pearl Harbor were expensive to construct and required great amounts of now scarce materials. Construction of the 2-story, 63-man, mobilization-type barracks was also discontinued for still another reason. It could not be evacuated as rapidly as a one-story structure. During the attack on Pearl Harbor, men had been trapped on the upper floors in several of these structures.4

In any case, shortages, especially of lumber, made imperative the building of a more economical type of barracks. In January 1942 the district office prepared designs for “demountable buildings”—one-story prefabricated structures that could serve as barracks, and, if necessary, as warehouses or administration buildings. Sixteen and one-half feet wide, these buildings, which could be extended in multiples of ten feet, were erected rapidly. Roofs and inside

walls were made of “canec,” a local wall-board, manufactured from the waste products of sugar refineries. On all of the Islands, large numbers of the troops were quartered in pyramidal tents with wooden floors.5

More warehouses were needed. Late in March, Emmons wrote to Reybold, “... the expansion of the facilities to accommodate increasing storage needs in this Department requires that fifty ... T/O type warehouses be constructed.”6 These fifty were in addition to the twelve requested in a letter of 5 March. In a number of ways, the theater of operations type of warehouse, like most theater-type structures, was not suitable for Hawaii. The district office designed a new model, from 50 to 1 o feet wide, which could be erected in variable lengths and made the maximum use of local materials. The trussed roof made possible a 30-foot span, without the row of center posts that was such an objectionable feature of the theater of operations buildings. Eaves were wider because the roofs of the standard structures were too narrow to keep out the driving rains of the Islands. In most cases the prescribed floors of earth were covered with asphalt or concrete. The new design also made possible more economical construction. It required 19 percent less lumber and cost only two-thirds as much to erect. Originally warehouses were spaced 00 feet apart. As time passed and the chances of bombing became negligible, the distance was reduced to 50 feet.7

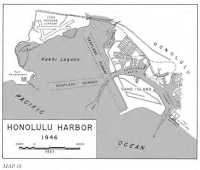

Honolulu Harbor

Before the Japanese attack the engineers were dredging Keehi Lagoon and Kapalama Basin and had started placing the fill for John Rodgers Airport. (Map 18) After 8 December they had the added responsibility of constructing piers and warehouses along the northeastern shore of the basin, a job previously charged to the Quartermaster Corps. The scope of most of this work greatly increased now that Honolulu harbor was jammed with ships. John Rodgers had high priority. This field, being built in an area of marshes and old fishing ponds, required an immense amount of fill, almost all of it taken from the seaplane runway areas in Keehi Lagoon. The engineers packed the coral at John Rodgers to an average height of 8 feet above low water level. At Kapalama, the dredge S. G. Hindes continued work on clearing a channel 1,500 by 1,800 feet to a depth of 36 feet to enable ocean-going vessels to come safely to the docking area. Along the shore, construction was under way on a host of piers, warehouses, and storage yards. The concentration of so many facilities in this small section of northwestern Honolulu was leading to serious overcrowding. In August Lyman suggested that the Army put some of its docks, warehouses, and storage yards on nearby Sand Island, thus providing badly needed facilities without increasing the congestion on the already overcrowded Honolulu waterfront.8

Map 18: Honolulu Harbor

Ammunition Storage

Ammunition was arriving in enormous quantities. Pre-Pearl Harbor estimates of the amount of storage space required had to be discarded. General Emmons, fully in accord with General Burgin’s plan for dispersing ammunition, wanted storage at various places on Oahu. Smaller facilities were to be above the ground; large ones, underneath. After making reconnaissances, the engineers chose Wahiawa Gulch, about five miles northeast of Schofield

Barracks, as the best site for the first large underground storage chamber, and began construction in March. Further investigation indicated that Kipapa and Waikakalaua Gulches in central Oahu afforded even better sites. Tunnels driven into the almost vertical walls of the two gorges would have entrances invisible from the air. To keep out bomb fragments, passageways to the storage chambers would be dog-legged or provided with baffles. The only drawbacks to these sites were lava formations and cinder pockets which would

necessitate timbering or concreting considerable portions of the chambers. By midsummer, the construction of storage areas above and below ground was well along.9

Road and Highway Repair

Deterioration of the highways was causing widespread alarm. “The main roads of Oahu,” Emmons wrote to Somervell on 14 June, “are nearly destroyed now from heavy military traffic. These, in addition to some new roads, must be built.” Meanwhile, the engineers were fully occupied in their struggle to keep the roads and trails on military reservations open. At the time of Pearl Harbor, the combat engineers, together with the units which used the roads and trails, were responsible for this work. The 34th Combat Regiment was busy mainly on the southern half of Oahu; the 47th General Service Regiment, having arrived in the Islands early in 1942, gradually took over from the 3rd and 65th Combat Battalions on northern Oahu. Keeping roads on military posts in good repair was the responsibility of the district. Various civilian authorities maintained arterial highways, country roads, and the streets of Honolulu. The civilian authorities were fighting a losing battle. In March 1942, representatives of civilian and military agencies held a conference in Honolulu to work out a plan whereby equipment and manpower could be pooled for work on Oahu’s principal highways. It was agreed that

the civilian agencies would prepare a program of road maintenance for the island, and submit to the department engineer and the Navy an estimate of the total number of workmen and the amount of materials and equipment needed. Lyman and representatives of the Navy were to determine the relative importance of the various projects and fix priorities of construction. The engineers and the Navy would provide the means to carry out the work. Plans were made, but little, if any, improvement of the public roads resulted, principally because more important jobs had higher priority.10

A New Engineer

Lyman died suddenly of a heart attack on 12 August, two days after his promotion to brigadier general. The next day Emmons asked the War Department for a suitable replacement. Col. Holland L. Robb served temporarily as engineer while a search was made for a permanent successor to General Lyman. Reybold radioed Emmons that he believed Col. Hans Kramer, engineer of the Panama Canal Department, was “eminently qualified because of past construction experience, including the construction of additional locks for the Panama Canal.” Emmons requested Kramer’s transfer to Hawaii, and the Governor of the Panama Canal agreed to his release. Promoted to brigadier general on 18 September, Kramer arrived

in the Islands on the 26th and took over as department and district engineer.11

Base Buildup Continues

Kramer soon learned that the Engineers in Hawaii were still responsible for an extensive construction effort. The work yet to be done on airfields, even if of a minor nature, was of considerable scope; in the fall of 1942, the engineers were working on eight fields on Oahu alone. Not the least of the many projects on Oahu was the huge 3-story subterranean airplane repair shop. A still sizable job was the construction of the tunnels for reserve gasoline. In Waikakalaua Gulch, nine tanks, each to hold 40,000 barrels, were nearing completion. Enormously increased requirements for gasoline had necessitated construction of more tanks; storage for an additional 240,000 barrels had been approved. Soon after arriving in the Islands, Kramer proposed that tunnels be drilled in Kipapa Gulch, and late in 1942 work on the new tunnels began.

A striking feature of construction in Hawaii was that so many installations were being put underground. Among the big subterranean projects, besides the airplane repair shop and the gasoline storage tanks, which were either under construction or about to be started, were the joint Army-Navy operating center at Aliamanu Crater and the tunnels for ammunition in Kipapa and Waikakalaua Gulches. Many smaller installations, also, including even the telephone exchanges, were being put underground. These underground structures, built on a tropical island that at times had extremely heavy rains, were most unusual; they were “bone dry.” In most tunnels in the tropics, even without leakage through rock faults, condensation was a serious problem. On Oahu, because of the remarkably low humidity (60 to 65 percent) and the small range in temperature (25 degrees) the installation of drainage or even the drying of the air was seldom necessary.12

Problems of Administration

Surveying the construction effort in Hawaii, Kramer found a number of areas where improvement was possible. He believed many engineers gave in too easily to commanders who wanted to expand their projects; the result was unnecessary construction. Numerous projects had “too many frills.” Some installations were being graced with such features as concrete sidewalks and curbed streets. The demand for luxuries was widespread; requests were even coming in for chromium-plated coat hangers. “Engineers,” Kramer stated at a conference with his key men, “particularly military engineers—must be realists. ... Refined design is not needed for ... most war installations. ...” In numerous instances, Kramer

felt, the engineers were adding to the cost by inadequate planning. For example, with the rainy season approaching, or already under way in some areas, buildings were going up without access roads or with roads so poor that the first rains washed them out entirely. Plans for one underground shop provided for gravity drainage, but water was being pumped out during construction, when permanent drainage could have been installed and utilized from the first. “Don’t trust to dry weather from now on,” Kramer warned.13

The new district engineer soon had to turn his attention to the contract with the Hawaiian Constructors. Quite a few changes had been made during the preceding months. In May, Lyman had informed the Constructors that the amount of work would be curtailed. Soon thereafter, the first jobs were transferred to the government, to be completed by hired labor, engineer troops, or, in a few cases, by local firms working under lump-sum contracts. By midsummer numerous jobs had been transferred. The canceling of some projects, the transfer of others, and last-minute additions to still others required a revision of the figure of $84,436,887 which the engineers and the Hawaiian Constructors had agreed in May was a fair estimate of the total cost of the work up to that time. In weeks, even months, of conferring, the two sides could come to no agreement. A number of preliminary matters had been settled, however. Late in August the

engineers and the contractors reached agreement as to the extent of the cutback in the contractor’s efforts up to that time, and early in September they arrived at an accord on how much work was covered. by the forty-three supplemental agreements. Still to be decided was the question of how much work the Constructors had under way or had finished which was not included in the original contract and the supplemental agreements.14

After Kramer arrived, the burden of the discussions centered on how the contract should be terminated. This led to an acrimonious wrangle. Some of the engineers believed it should be terminated because of the fault of the contractors; Kramer’s position was that since both government and contractor had made mistakes, termination should be at the convenience of the government. Ending the contract on that basis would probably mean retaining, at least for a time, the good will of the contractor and his employees. Another matter of contention coming more to the fore was the amount of the fixed fee. The Hawaiian Constructors felt that the many supplemental agreements and the countless changes in the work had made the fee hitherto agreed upon entirely inadequate. Meanwhile, confusion increased as job after job was transferred to the government. Many of the contractors’ employees did not look forward to working for the government any more than the government employees relished the

prospect of working with the contractors’ men. “Some feeling exists,” Kramer remarked, “that, by and large, every Hawaiian Constructors’ man is a scoundrel.” To make the transition as smooth as possible, Kramer held numerous conferences attended by key engineer employees and representatives of the Hawaiian Constructors.15

On 31 January 1943 the contract was terminated at the convenience of the government. Up to that time the engineers had paid a fixed fee of $541,031. They had bought $625,051.75 worth of used equipment from the Hawaiian Constructors and had paid them $124,105.05 for the rental and recapture of new equipment. The debate over the full amount of the contract and the fixed fee continued. Two of the most vexing problems were to determine what changes had been made in various jobs and how much work had been done which had not been stipulated in the original contract and in the supplemental agreements. Representatives of the Hawaiian Constructors and the engineers held many meetings to iron out differences; they were to have months of work ahead of them.16

On the whole, the Honolulu District seemed to be plagued by more than the usual difficulties and inefficiencies. To improve the work, General Kramer set up the “Bottleneck Busting Division” in January.17 Headed by Colonel Nurse, the new unit had a difficult assignment. Its major job, Kramer announced, was “locating and removing ... all forms of obstruction—too much or too little labor, slackers who cheat and chisel ... favoritism and cliques, grievances and jealousies, boondoggling, lack or misuse of equipment.”18 The division was to deal at first primarily with problems on Oahu; those on the outlying islands would be gone into later. Insofar as possible, the members of the division were to make use of the technical assistance of men working on the jobs being investigated; a small force would do administrative and supervisory work in the district office. Colonel Nurse’s men found the greatest inefficiencies in connection with the assignment of the workmen to the various projects. Many, improperly classified, were not doing the jobs they were best qualified for. Some projects had too many workers; others, not enough. Low morale and loafing on the job were all too common. A number of projects were administered haphazardly at best; at some, the workmen did not even have regular paydays. By mid-February, about 400 “bottlenecks” had been broken—an average of 14 a day. Difficulties nevertheless continued, and complaints about inefficiency kept coming in. A new problem arose. Because the amount of construction required was diminishing, there was a surplus of some types of labor. “We have been fighting absenteeism,” Kramer told key officers and civilians of the district as late as 10 April. “I assure

you that loafing, idleness, and laxness on the job are going to disappear.”19

Despite two years of continuous construction, there was still a great demand for new projects. Kramer’s office made an analysis of all requests received by the engineers during the period from 15 February to 15 April 1943; during these two months, 576 came in, of which o were disapproved. Of those approved, most were for more troop housing, more water, power, or sewerage facilities, especially for the Seventh Air Force, the improvement of piers, the construction of more warehouses, and the strengthening of fortifications. Of the projects approved, only 14 could be regarded as of major importance.20 There were great numbers of requests for minor construction. “The current uninterrupted flow of directives authorizing minor ... work at stations where the major program has already been completed ... is unduly delaying the desired reduction of overhead and construction personnel,” The Adjutant General stated in a memorandum of 2 April, addressed to the Army as a whole.21 Another memorandum sent out on 15 April directed: “Spartan simplicity must be observed. Nothing will be done merely because it contributes to beauty, convenience, comfort, or prestige.”22

These instructions seemed especially applicable to Hawaii. The Islands were in a theater of operations and were considered a better than average training area for combat troops. In camps where the troops were to be toughened, such comforts as electric lights, hot water, and flush toilets were not essential. To make matters worse, some commanders in the Islands seemed to feel that tactical troops should be exempt from labor duties. The engineers held that this belief was incorrect. Troops occupying an area should perform such simple jobs as clearing weeds and underbrush, digging ditches for drainage, and doing minor road repair. But, as in other theaters, restricting construction to essentials was difficult. Lt. Col. W. H. Johnson of the Supply Division, OCE, in a memorandum of 26 May 1943 stated, “Hawaii recently submitted a very comprehensive and bulky estimate in six parts embracing over 400 pages and calling for a large amount of air compressors, air diffusers, water valves, thermostats and coils, all of which are to be used principally in installing air conditioning equipment.” Johnson went on to say that all these supplies were being requested despite the fact that the status reports from the Hawaiian Department indicated that depots were well stocked with these items.23

Construction Progress

Much progress was made in 1943. Work on airfields on Oahu moved ahead steadily, and the underground airplane repair shop was beginning to take shape. By fall, the military outlook had improved so much that the blocking of airfields on the outlying island was dis continued

and at the same time obstacles on grazing lands and pineapple and cane fields on all the islands were removed. Improvement of Honolulu harbor was continuing. By early 1943, five new warehouses at Kapalama Basin were almost finished, and work was well along on two new piers. Army and Navy officials and businessmen in Honolulu had for years stressed the need for a second harbor entrance; now something was being done about it. In February the engineers began to clear underwater obstacles for a second entrance across Keehi Lagoon to Kapalama Basin; at the same time they prepared plans for piers and warehouses to be built on Sand Island. Although the Navy was no longer greatly interested in the seaplane runways in Keehi Lagoon, dredging continued mainly as a quarrying operation to provide coral for John Rodgers Airport. The engineers provided more camps, staging areas, and rest and recreation centers; in midyear, they started work on a number of general, field, and evacuation hospitals, and began surveys for a huge new structure to replace Tripler General Hospital, located north-west of Honolulu. At the same time, some of the schools taken over for hospitals were being returned to the civilian authorities. Still two of the most unusual projects were the drilling of tunnels in Kipapa Gulch for the storage of reserve gasoline and the emplacement of the big naval guns. The tunnels consisted of four parallel, cylindrical excavations, 938 feet long and 22 feet in diameter, with a cover of zoo feet of solid rock. They were being lined with steel plate. Insofar as the engineers in Hawaii could determine, these were the first steel-lined tunnels for storing gasoline ever constructed. Final locations for the big guns were selected by April. The Navy, making good progress in salvaging the turrets, had them ashore by midyear; installing the batteries proved to be even more complicated than earlier engineer estimates had indicated. Detailed plans for the design and assembly of of naval turrets on land were nonexistent. Kramer set up a warehouse near Pearl City to store the hundreds of small parts which were salvaged or newly fabricated, and Emmons appointed a board of four officers, including an engineer, to expedite the work of emplacement. One project on which no progress was made was the repair of disintegrating roads and highways. Army commanders were inclined to feel it was the responsibility of local civilian officials to maintain and repair roads and streets, particularly since local tax revenues had increased enormously during the war, with much of the additional money coming from the armed services. The civilian authorities did not agree, and a workable program of road improvement was not initiated. On the whole, by late 1943, much of the major construction in the islands had been completed. The new work the engineers received was mainly for additional facilities at some of the airfields.24

Supply

The supply system was working satisfactorily after mid-1942. During the remainder of that year, stocks were, as a rule, arriving from the mainland in ample amounts and in excellent condition. Only occasionally were they poorly packed or improperly labeled. If an item was in short supply, local merchants could often furnish it; this was generally true with regard to fortifications materials. Shortages remained in lumber and in parts needed for the tanks for reserve gasoline storage. Machinery was fairly plentiful.25 “The largest part of the equipment ordered and required is now on hand,” Emmons had written to Somervell on 14 June 1942. “Some additional items have been ordered. The tonnage involved is not appreciable.”26

Spare parts were scarce in 1942. None of the stocks requisitioned from the mainland arrived that year; most of those on hand came from local sources. Parts supply units were lacking. Arriving three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the st platoon of the 452nd Depot Company had taken over spare parts supply from the 34th Engineers, but the platoon was not much better trained than its predecessor in the work of stocking and distributing parts. There were no maintenance units, but this was not so serious a matter because local mechanics were available for servicing machinery.27

In 1943 stocks of materials, equipment, and spare parts constantly increased as requisitions sent to the mainland were being filled and shiploads of items reached Honolulu. With construction tapering off late that year, supplies were no longer so urgently needed and the amounts on hand were adequate in most respects. Stocks of equipment were sufficient. Even spare parts became fairly plentiful. The first shipments ordered from the mainland had begun to arrive in January 1943, and by April fairly large quantities were coming in. As before, local firms manufactured some parts and reconditioned others. As in other theaters, principal shortcomings in supply were the lack of a continuous inventory and the absence of overall stock control. Steps were taken to improve matters. Early in 1943 the 452nd Depot platoon was expanded into a company, and one of its platoons was assigned to the spare parts section of the engineer depot. Progress was slow. A representative of the Engineer Spare Parts Depot in Columbus, Ohio, inspecting spare parts supply in Hawaii in January 1944, commented on the need for better organization and stock control.28 So far, there had been no great pressure on engineer supply in Hawaii. The coming offensive would undoubtedly change this unusual state of affairs. “Hawaii has been on the receiving end for some time,” Somervell

wrote to General Marshall from Hawaii in September. “It must now reorient its thinking and its organization to be on the sending end of the performance.”29

Meanwhile, the engineers were trying to straighten out their accounts and pay what they owed for supplies they had received from local merchants. As old bills were paid off, new ones kept coming in. At the end of 1943 payment of $1,000,000 was held up because the district contracting officer and the finance officer could not agree on the validity of numerous vouchers. Because payments were so slow, the engineers were still not popular with many of the local businessmen.30

Maps

Since the Central Pacific was not involved in combat during 1942 and the first months of 1943, the engineers had to devote only a minimum effort to preparing maps. The department engineer was responsible for supplying maps to the troops; needs were in large part met by the Hawaiian Department Reproduction Plant, operating under the department engineer’s command. Draftsmen periodically revised the topographic maps of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey and printed the revised versions needed for military purposes. Before the war, Lyman had maintained his small stock of maps, together with hydrographic charts, in concrete vaults at Fort Shafter. The 64th Topographic Company, arriving late in 1942, was the only mapping unit in the Islands. With little to do, part of the men were sent out to make surveys of tracts of land the War Department had acquired or was interested in.31

This easygoing state of affairs changed in mid-1943. The 64th engineers, henceforth working under “war” conditions, had to prepare maps of Japanese-held islands from photographs supplied by Army or Navy fliers. The men had had little or no experience in preparing such things as “beachstrip mosaics” or in using indifferent photography, obtained by aircraft in spite of bad weather and enemy opposition, but they secured the needed equipment and began work. In 1943 Navy fliers, taking off from carriers west of Hawaii, provided a constantly growing number of photographs for the 64th to work with. The unit cooperated closely with other Army and Navy elements in Hawaii interested in map production and the gathering of intelligence, such as the Seventh Air Force, the Intelligence Center, POA, and the reproduction plant of the engineer department. Soon the men were able to produce on short notice the maps expected of them. The 64th engineers, in addition, made maps and did drafting for the Navy. By late 1943, their work load had increased so much that more men were needed, especially those skilled in drafting, photomapping, and reproduction. Also needed was more equipment for interpreting data supplied by aerial reconnaissance. Best suited for

the Central Pacific was a GHQ topographic battalion, less one company. The plan was to expand the 64th into such a unit in 1944.32

Training

In the rush to complete construction after Pearl Harbor, the engineers had to neglect training. As a rule, the men learned by doing—by going out and building runways, warehouses, roads, fortifications, and obstacles. From time to time, the combat engineers participated in maneuvers designed to test various aspects of the defense plans. The coming offensives forced the engineers to emphasize training as never before. It was especially important to prepare the men for combat. Soon after arriving in Hawaii, Kramer stressed the need for something better than the sketchy instruction being given. He believed, for example, that more training in removing mines was necessary and that qualified instructors—men who had had actual experience in removing enemy mines in a combat zone—should teach the troops. Despite the increased emphasis on training, inadequacies persisted. In March 1943 the Inspector General reported that there was still insufficient stress on preparing troops for combat. The difficulty was that commanders were expected to get the work done and train the troops at the same time. In the fall of 1943, engineer training was stepped up. The troops received more training in small arms fire. Some men were given instruction in laying Marston mat, and specialists were trained in using flame throwers. A school was started to provide instruction in operating water stills. A major drawback in the Hawaiian Islands was the absence of sizable rivers. Little could be done to give the combat engineers adequate training in putting up ponton bridges and in using expedients for crossing streams. In any event, Kramer wanted all units that were alerted for movement to the combat zones to get at least some “catch-as-catch-can training.”33

Plans for the Offensive

Early in 1943 the Joint Chiefs of Staff began to make plans for an offensive in the Central Pacific to start later that year. At the TRIDENT Conference in Washington in May, they obtained British agreement to a drive from Hawaii to Japan that would begin with the capture of the Gilbert Islands, to be followed by the seizure of the Marshalls. These assaults were to have a higher priority than any possibly conflicting operations in the South or Southwest Pacific. On June Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr., replaced Emmons as commander of the Hawaiian Department. On 14 August General Richardson became the head of the newly activated United States Army Forces in the Central Pacific Area (USAFICPA). He chose Kramer as his engineer. On September Kramer merged the department and district organizations into the Engineer Office,

Central Pacific Area, but the two components continued to have their separate functions. Kramer appointed two deputies—Lt. Col. Desloge Brown, to supervise the activities of the department, and Col. Benjamin R. Wimer, those of the district.34

For the coming offensives, Admiral Nimitz set up a joint Army-Navy staff to replace the Joint Logistical Board, POA, which had heretofore resolved supply problems pertaining to both services. The new Joint Staff, POA, directly under Nimitz, had four divisions. Two of them, J-1 and J-3, were headed by Navy officers, and two, J-2 and J-4, by Army engineers. J-2 was under Col. Joseph J. Twitty. He established close contact with Kramer’s office with regard to engineer intelligence and mapping. J-4 was headed by Brig. Gen. Edmond H. Leavey, who for many years had worked under Somervell as one of his most capable assistants. In 1943, while Leavey was serving in the Mediterranean Theater, Somervell recommended him for the important assignment on Nimitz’ staff. There had been some feeling among high ranking Navy officers, among them Admiral King, over having Army men on Nimitz’ staff. Somervell, visiting Hawaii during his tour of the Pacific areas in the fall of 1943, reported to Marshall that Leavey’s arrival in Hawaii had been “more or less of a bombshell.” But owing to his “outstanding capabilities” he had been “well received.” Harmony had apparently been established, since Leavey was living in Navy quarters with the other three members of the Joint Staff. Somervell expected that Leavey would “secure the proper arrangements in the logistics field” through his “tact and downright capacity.”35

One of the shortcomings of the Joint Logistical Board had been that it did not provide sufficient overall direction and coordination in Army and Navy planning for construction and supply at new bases. The board merely coordinated plans already prepared independently by the services. Thus, in advance of each operation, Army and Navy would arrive at a formal agreement as to which facilities and what supplies each would provide for its own use and which each would provide for joint use. Difficulties arose in coordinating Army and Navy plans already prepared, especially to prevent unnecessary duplication of such facilities as hospitals, post exchanges, and communications systems. At times, Army and Navy disagreed considerably on how joint supply should be handled. Since the operations so far undertaken had involved the occupation of small islands with no enemy resistance, the difficulties had not been insurmountable. As planning began for more extensive operations, the problems of coordination loomed larger.36

The Joint Staff, patterned after the concept of the Army General Staff, modified

to meet conditions in the theater, provided greater overall direction and coordination. In accordance with directives from Admiral Nimitz, it was to prepare a master plan for each operation in advance. J-3 developed the overall operational plan; J-4 worked out a detailed logistics plan. Both plans were coordinated and then discussed with the senior staffs of the various service commands in Hawaii and, if necessary, altered to meet available means. Meanwhile, the Joint Staff prepared the final command directives, which it discussed informally with the staff members of the task force scheduled to conduct the operation. These directives set forth responsibilities for construction and supply, allocated shipping space, and established shipping priorities. Upon receiving their formal directives, task force commanders completed the details of their plans and set out to obtain such additional men and supplies as they needed. Major Army and Navy administrative commands screened requests from task force commanders and computed overall space and tonnage requirements, which they forwarded to the Joint Staff for final review. Insofar as the Engineers were concerned, the new system not only eliminated some unnecessary duplication in construction and supply, but also centralized responsibility for construction. Each new base would have one engineer, either Army or Navy, directly responsible to the base commander for all construction.37

One of the most important responsibilities of the Joint Staff was the shipping of supplies in the proper priorities. Leavey’s section had the main responsibility for fixing priorities. Having a representative of the Army in this important job would, Somervell believed, result in better conditions than in the South Pacific, where the Army was at a disadvantage because it was completely dependent on the Navy for getting its supplies sent forward. One of the aims of the staff v^Tas to work toward “direct loading” from San Francisco, that is, sending supplies straight to the islands where they were to be used, which would mean bypassing Hawaii.38

The new procedures had to be developed gradually. Since campaign plans were formulated some time in advance, those already prepared had to be brought under the new system in somewhat piecemeal fashion and coordinated as quickly as possible. When the Joint Staff took over on 6 September 1943, planning for the assault on the Gilberts was already so far along that little could be done to revise arrangements already made. Little could have been done in any case, since the Joint Staff had to spend many weeks in assembling personnel to take care of its multitudinous duties. The staff had to be set up on an experimental basis, since there was no headquarters organization which might have been used as a model. Leavey estimated that 85 officers and 120 enlisted men were needed for J-4 alone; as the war progressed, this estimate proved to be too low. Men began arriving in fairly adequate numbers in the fall of 1943 and

set to work to make the new procedures more effective for operations scheduled to take place after the capture of the Gilberts.39

By the fall of 1943 the Central Pacific was ready to launch its first offensives. Hawaii had been converted into a powerful base. The fleet, having overcome the setback it received in the Pearl Harbor debacle, was prepared to strike. The Army was also ready. By October the number of troops in Hawaii numbered 165,423, with the engineers totaling 10,626. Ample and well-trained manpower was on hand to seize some of the Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific.

First Offensives in the Central Pacific

Baker Island

The offensive got under way in late 1943. The Gilbert Islands, the first objective, were about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii; in Allied hands they would provide sites for bases to support operations farther west and would strengthen the lines of communications from Hawaii to the Southwest Pacific. Before the Gilberts could be attacked, certain preliminary operations were necessary. In August, Nimitz ordered the occupation of three small islands east and southeast of the Gilberts and the building of airfields on them. They were Nukufetau and Nanomea in the Ellice chain, and Baker, a lone islet some 500 miles east of the Gilberts. Marines and naval construction battalions were sent to Nukufetau and Nanomea. An Army task force was to go to Baker, garrison the island, and build an airfield. The 804th Aviation Battalion, commanded by Maj. Edward A. Flanders, had the job of construction.

On the morning of September, the task force reached its destination. The island, one mile long and almost a mile wide, was rimmed by a narrow beach behind which the coral rose to a height of about twenty feet. The sand on the beaches was so deep that no equipment except bulldozers could move forward. Men of the 804th dozed roads across the landing beaches, laid down Sommerfeld mat, and cut roadways through the island’s rim to the central plateau. A reconnaissance party, making a survey the morning of the landing, found the center of the island was a dry basin. The runway site which had been selected was not the best, and a new center line was run so that a longer strip could be built. Grading began shortly after noon. Seven days later it was complete and 3,000 feet of Marston mat was in place. The runway was adequate for fighters, and soon an Army fighter squadron moved in. Bombers taking off from this field could reach the western Marshalls, a feat hitherto impossible from any Allied base.40

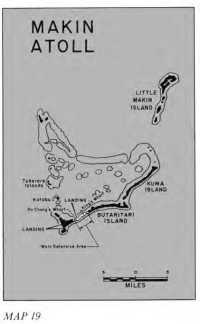

Makin

Three of the Gilbert islands were to be captured—Tarawa and Apamama by the Marines, and Makin by the Army. Makin was one of the northernmost atolls in the island chain. The 165th Regimental Combat Team of the 27th Infantry Division was selected for the assault; Company C and part of Headquarters Company of the division’s 102nd Engineer Combat Battalion were to go in with the infantry. The planners in Hawaii concluded that large numbers of service engineers would be needed during the assault phase; they therefore gave the 152nd Combat Battalion the job of unloading supplies and equipment.

To defend the bases to be built on the islands seized from the Japanese, General Richardson organized a new type of unit, the defense battalion, patterned after a similar kind of organization in the Marine Corps. Engineer service units and Seabees would be responsible for building bases and, together with the defense battalions, would constitute the “garrison forces” of the islands. Some of the islands would have garrison forces composed solely of Marine and Navy units; others, entirely of Army units; still others of all three. An Army or Navy officer would serve as island commander. If both Army and Navy units were used, care would have to be taken to prevent duplication of functions and organization; as already indicated, each island commander would have one staff engineer.

Elements of the 34th Combat and 47th General Service Regiments, both of which had seen long service in the Hawaiian Islands, were scheduled to serve in the first garrison forces being organized. Any island worth taking in the Central Pacific would probably already have an enemy-built airfield which could be rehabilitated. If none existed, one would have to be built. In that case, aviation engineers would be assigned to the garrison force until the field was finished, whereupon they would return to Hawaii. All other construction would be the responsibility of the 34th or 47th Engineers. If an airfield already existed, the 34th or 47th Engineers would rehabilitate it, build fortifications, erect housing, and operate and maintain utilities. Two companies of the 47th and the entire 804th Aviation Battalion were assigned to the Makin operation; the service engineers totaled 1,169 in a garrison force of some 4,000 men.41

The engineers did detailed planning for assault and construction. Planners in major theater headquarters and on the newly organized staff of Col. Clesen H. Tenney, garrison force commander, made estimates of the amount of construction needed. Kramer’s staff reviewed the requests, and prepared a plan for base development which listed in detail all the construction the engineers would do. Estimates were then made of the amount of supplies required, and detailed lists of materials needed during the first ninety days were prepared. Supplies earmarked for the operation were to be shipped in three priorities. The 64th Topographic Company furnished

Map 19: Makin Atoll

about 100,000 copies of maps prepared from aerial photographs.42

The task force reached Makin atoll on 20 November. The troops were scheduled to land on narrow, heavily wooded, 9-mile-long Butaritari Island, on the southeastern side of Makin’s triangular-shaped lagoon. (Map 19) The men came ashore at two points: on the western end of the island and on the lagoon side. Each of the three platoons of Company C, 02nd, went in with its battalion landing team, an engineer squad equipped with bangalore torpedoes going ashore with the first wave to remove obstacles which might impede the landing. Enemy opposition was light, and both beaches were clear of obstructions. As soon as the beachheads were established, the 152nd engineers began unloading supplies, each company supporting one battalion landing team. The men did not have an easy time of it. The beaches at the western end of the island were rocky; and on the lagoon side the landing craft grounded in shallow water 600 feet from shore, forcing the troops to reload supplies on Alligators and Buffaloes. Two of the objectives of the infantry landing on the lagoon side were King’s Wharf on the east and On Chong’s Wharf, on the west. The first fell without a fight; the second, taken after a brief struggle, was heavily damaged. The engineers soon had the former in operating condition, and by the second day, all shore parties of the 152nd were busy at this pier unloading LSTs, soon helped by the 804th engineers, part of whom landed that day.43

Aerial photographs indicated that almost all defenses were between two tank barriers which extended across ‘the island, one of them about a half mile west of the lagoon landing area and the other about a mile to the east of it. At both the Japanese had dug moats and placed coconut logs in the ground to stop tanks. A most important task of the landing forces was to capture the defenses between the barriers. The troops advancing inland from the west end of the island continued

to meet light resistance. Those coming ashore at the lagoon pushed across the island and then veered to the east and west. Here too opposition was unexpectedly light. Only a few defense works—antitank gun positions, machine gun emplacements, pillboxes, and air raid shelters—were encountered. The infantry bypassed the strongest of these, leaving a few riflemen to cover them. The 102nd engineers then moved up and demolished them with explosives.44

Some of the troops moving westward from the lagoon area were stopped by a concrete shelter, about thirty feet long. It had blast-proof entrances at either end. When the men tried to reduce the obstacle by tossing in hand grenades, the occupants threw them out again. A tank moved up, firing 75-mm. shells, but without effect. A new maneuver was tried. The tank, followed by 2 infantrymen with automatic rifles and 4 engineers, 2 with rifles and 2 carrying a flame thrower and pole charges, moved up slowly to one of the entrances and stopped within a few feet of it. While the riflemen covered the opening, the 2 engineers with flame thrower and pole charges crept toward the shelter. The flame thrower, still wet from the landing, failed to function. One of the men, taking about a minute, placed a pole charge with a 15-second fuse attached just inside the entrance. The group scrambled for cover. The explosion killed the occupants.45

The infantry advancing eastward from the lagoon landing area ran into the island’s most strongly fortified area; it consisted of a system of pillboxes and shelters, a number of them connected by passageways, some underground and some above ground. Shelters and tunnels had a covering of logs and earth up to six feet thick. One tunnel, some 00 feet long, had machine gun emplacements at both ends; various well-concealed openings were just large enough for a man to squeeze through. Nearby taro pits served as moats, and kept tanks from approaching. Artillery, bazookas, and hand grenades were largely ineffective, and the flame throwers on hand were too wet to be of value. The infantry commander directed the engineers to reduce the obstacle. They dropped TNT charges into the machine gun positions at both ends; when the Japanese emerged from the openings with bayonets drawn, they were shot down. Having been delayed about four hours, the advance eastward was resumed. On the third day the east tank barrier was taken without opposition; the west tank barrier had been taken the day before. Makin was in American hands. The island was captured easily—in contrast to the bloody battle the marines were waging on Tarawa.46

On the fourth day, the 804th Aviation Battalion began work on the airfield. Plans called for a fighter runway, surfaced with Marston mat, to be extended eventually for bombers; if possible, a

King’s wharf, Butaritari Island, Makin Atoll

second runway was to be built. Making a reconnaissance of the site, the engineers found that a large swamp covered part of the area, making rapid construction impossible. Nevertheless, the men began work, since there was little chance of having the plans altered without undue delay. When a D-8 dozer almost immediately bogged down in the marshy ground along the center line, work was stopped. A reconnaissance group which had just finished a detailed survey reported that the swamp extended for about half a mile. The engineers ran another center line and began clearing anew. The only complication was a series of taro pits. The men assembled

a large amount of equipment, borrowing light and heavy dozers from the infantry, tractors from the artillery, and equipment from service units of the garrison force. Soon the work was proceeding systematically. A D-8 with one push would topple a coconut tree; a second push freed the root mass from the ground; a tractor then towed the tree away. The men removed about a foot of top soil. Underneath was well-compacted sand with a considerable amount of silt. Clean coral from the lagoon was used for surfacing. By to December the runway, surfaced with Marston mat, together with a parallel coral taxiway, was operational. The

first fighter planes arrived four days later. The aviation engineers were well on the way toward completion of their first combat mission in the Central Pacific.47

Coral

Makin was one of the many coral atolls the engineers would encounter on the road to Tokyo. From now on, the little-known islets of the Central Pacific were to acquire a tremendous significance. They were the steppingstones, the “stationary aircraft carriers” on the way to Japan. For the constructing engineers they were almost ideal “aircraft carriers” because they furnished a valuable, and up to this time little-known, construction material—coral. The great quantities of this material, so readily accessible, would make possible the rapid construction of runways and roads. Coral had long been used in some tropical countries for construction, but little was known in the United States regarding its use before the outbreak of World War II. The Engineers had had little information regarding either coral islands or construction with coral. They had learned from experience on Canton and Christmas and on the islands of the South Pacific, and they collected additional data. The studies made yielded much information not only about construction with coral but also about the formation and structure of coral atolls, information of vital importance in preparing and making amphibious assaults.48

Coral, made up of the skeletons of minute spherical animals, was chemically similar to limestone. About one-eighth of an inch in diameter, the animals could live only in tropical or subtropical waters. Most species grew only in salt water. They flourished best if the salt content was between 2.7 and 3.8 percent and the depth of the water less than 150 feet, with temperatures ranging from 66° to 100° F. Coral fed on plankton washed toward them by the waves and currents of the ocean. On an island’s windward side, where food was plentiful and the water well aerated, coral grew rapidly. Reefs proliferated and were found from a few yards to several miles offshore. Approaching an island on this side was, as a rule, dangerous, as the reefs were almost invariably numerous and rocky. On the leeward side, the reefs were generally flat, had few rocky patches, and were often submerged at high tide. Coral islands, encircling a lagoon, formed an atoll which usually opened to the sea on the leeward side. In the central Pacific, coral islands were low and flat, being only four or five feet above sea level. In the volcanic islands of the western Pacific, upward thrusts of land accounted for the presence of hills or cliffs of solid coral.49

Whether dead or alive, whether taken from the top of a cliff or the bottom of the sea, coral was suitable for roads and runways. The surface of an island usually consisted of coarse coral sand packed hard when dry. In the interior, the soil was often a sandy loam. Coral could be

easily quarried; the engineers had to use explosives only occasionally. The coarser the coral—up to particles about two and one-half inches in diameter—the easier the job of surfacing. Using sheepsfoot rollers, the engineers broke the pieces sufficiently to fill the interstices with the right amount of fines. A smooth, hard runway was the result. Coral had to be kept wet continuously to keep it from becoming dusty. If dry, it rutted easily and blew away. It could be wetted with either fresh or salt water. Some coral runways were sprinkled daily. Roads and runways which were subjected to heavy use were surfaced with asphaltic concrete. In some cases, the engineers first applied a binder while in others, they sprinkled the coral and immediately paved over it. Sometimes they rolled a surface until it was hard and tight and then applied a coating of oil, which bound the surface temporarily and made it waterproof. But such a runway had to be repaired almost daily. It required special attention near the ends where aircraft did considerable turning.50

Progress on Makin

Work on Makin moved ahead rapidly. By mid-January 1944, the 8a4th engineers, helped for a time by the 152nd, which had been attached to the Garrison Force, had extended the runway to 7,000 feet, paving the extra 3,000 feet with coral. Two taxiways paralleled the runway. There were hardstands, revetments, and some forty prefabricated buildings. An aviation gasoline storage system was in operation, the tanks of which were filled by means of a submarine pipeline extending out to an anchorage for tankers. The Japanese had reacted violently to the seizure of the Gilberts. After the first American landings they bombed the islands frequently. The heaviest raid took place on 15 January; bombs dropped on the 152nd Battalion area on that day killed 6 men and wounded 30.51 But despite Japanese air attacks, the American hold on the Gilberts was secure. By mid-January, preparations were already well along for further thrusts against Japanese islands in the Central Pacific.