Chapter X: The China–Burma–India Theater, 1941–August 1943

On the defensive in the Pacific after Midway, the Japanese were under pressure in still another quarter. This was the China–Burma–India (CBI) theater. Operations there, reaching their full stride by the beginning of 1944, had by then been under way for more than two years. Soon after the outbreak of war, Japanese forces had marched on Burma to cut off China’s last land communications to the west. (Map 20) The United States had reacted by dispatching commanders, troops, planes, equipment, and supplies to help keep China in the war and prepare for ground and air offensives against enemy forces in eastern China and the Japanese home islands. Japanese successes in isolating China by land and sea made it extremely difficult to send in men and supplies. The obstacles encountered in developing an effective fighting force of Americans, British, Indians and other Commonwealth troops, and Chinese proved all but insurmountable. The immense distances in the theater, the conflict of national interests in that part of the globe, and the isolation of China and India from each other and from Burma made the task of organizing the theater’s resources effectively an impossible one and led to repeated diplomatic and military crises. The plan to develop China together with Burma and India into a major theater of war never fully materialized. As time passed the strategic importance of CBI declined as it became increasingly evident that the war against Japan would, in the main, be fought and won in the Pacific.

The attempts to develop a major theater of operations in Asia would require prodigies of engineering. Before China could receive material assistance from the outside, a line of communications would have to be created. The only feasible route of entry was from India. But India and China were separated by the lofty Himalayan range, and with the Japanese holding most of Burma by the end of May 1942, supply by air remained the only alternative. Thus, for the first engineers in the theater, construction of airfields, not only to defend India but also to support an airlift to China, was of paramount importance. Late in 1942, when the Allies had completed plans for a campaign to recapture northern Burma, the engineers were given the primary mission of building ground communications to support a campaign in Burma and to make possible the sending of large quantities of supplies overland to China. American engineers

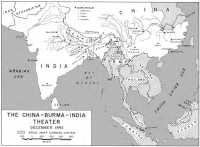

Map 20: The China–Burma–India Theater, December 1942

were to help the Chinese improve the world-famous Burma Road linking China with northeastern Burma, and were to take sole charge of constructing the Ledo Road from northeastern India across northern Burma to a junction with the Burma Road.

By the time of the QUADRANT Conference at Quebec in August 1943, the development of the B-29 bomber had opened up the possibility of long-range air assaults against the Japanese home-land from bases in China. The engineers in CBI were consequently the first to build airfields overseas for the big bombers. As a further consequence of the decisions made at Quebec, the engineers were called upon to link eastern India and southwestern China with the most extensive military pipeline system ever constructed—to supply the airlift to China, facilitate combat in Burma, and supply American air units in China. Many of the engineer feats in CBI actually contributed little to defeating Japan. But the fact remains that engineer projects in the CBI because of their sheer magnitude were among the most impressive of the war. In no other theater were engineer officers to fill so many key positions in the chain of command.

Priority on Airfields

Prewar Efforts To Help China

The United States began to support China in her fight against Japan well before Pearl Harbor. In April 1941, President Roosevelt approved sending lend-lease aid; by late spring the War Department was administering a program of assistance totaling nearly $125,000,000. Part of this money was being used to buy materiel and rolling stock for a railroad the Chinese and British were building from Kunming, in southwestern China, to Lashio, in northeastern Burma, where it would connect with the Burmese railroad system. In June the United States set aside a hundred new fighter planes for China to form the nucleus of a modern air force. The War and Navy Departments released over a hundred pilots to fly these planes as members of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) being organized in China by retired Air Corps Capt. Claire L. Chennault.1 In July the War Department established the American Military Mission to China to advise the Chinese in Washington and Chungking with regard to the procurement, shipment, care, and use of American equipment. That same month General Schley sent an officer expert in railway construction to the Far East to act as adviser to the Yunnan–Burma Railroad Authority, which was building the Chinese section of the railroad between Kunming and Lashio. To provide the first of the approximately 30,000 tons of rails needed, the Corps of Engineers procured and started dismantling a 125-mile stretch of abandoned narrow-gauge railway of the Denver, Rio Grande, and Western in New Mexico and Colorado.2

In September the Shell Oil Company, which had just perfected a light, “invasion-weight” petroleum pipeline, interested the military mission in having such a line installed between Kunming and Bhamo in northern Burma. In agreement with the mission, the oil company sent one of its specialists to Burma to prepare a plan for constructing the pipeline. General Kingman, Assistant Chief of Engineers, had an investigation made of the proposed route. He reported in October that such a line appeared to have “sufficient merit ... to justify further investigation.”3

Help for China After Pearl Harbor

After Pearl Harbor all these efforts to strengthen China were in jeopardy. The course of the war soon threatened to bring all of southeast Asia under Japanese control. The capitulation of Thailand in mid-December enabled the enemy to make gargantuan strides toward attainment of his two main objectives, one of which was to seize the British naval bastion of Singapore, and the other to capture southern Burma and cut the railway running northward from Rangoon to Lashio. The latter was not only an important railhead, but also the southern terminus of the Burma Road, a narrow, graveled highway winding 700 miles northeastward to Kunming—China’s last line of surface communication with the outside world. The Japanese moved swiftly into Malaya and Burma, and Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. After entering southern Burma in mid-January, the Japanese drove hard for Rangoon. If they captured that key port, China would be isolated.

At the ARCADIA Conference in Washington Roosevelt and Churchill agreed that China should constitute a separate theater and as such be under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, head of the National Military Council governing Free China. Because he was also the head of a state, Chiang would not be under the Combined Chiefs. Churchill and Roosevelt proposed that he establish a planning staff to include American, British, and Chinese officers. Chiang agreed and asked that a high-ranking American general be sent to Chungking to act as chief of the Allied staff. Stimson and Marshall conferred the post on Maj. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, who had served for many years in China as military attaché. On 2 February the War Department appointed him Commanding General of the United States Army Forces in the Chinese Theater of Operations, Burma, and India. Stilwell was to go to the Far East with about thirty American officers composing the U.S. Task Force in China.4

As his engineer, Stilwell chose Col. William H. Holcombe. In late December 1941, the War Plans Division had designated Holcombe, at that time assistant commandant of the Engineer School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, to serve

as engineer adviser to Stilwell in the planning for the invasion of North Africa. When Stilwell received his assignment to serve with Chiang instead, he transferred Colonel Holcombe from the North African project. On 11 February, Stilwell and his staff left New York by plane for India.5

On the 25th Stilwell and his group reached New Delhi. To the ensuing round of conferences with the British commander-in-chief in India, General Wavell, and his officers in General Headquarters (India), Stilwell brought an impressive catalog of American plans. He emphasized that his major missions were to modernize and rearm the Chinese Army and to step up American participation in the air war over China. To carry out his plans, he intended to increase lend-lease tonnages moving up the railway from Rangoon to Lashio. Should Rangoon fall, he hoped to fly supplies from the Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter field at Dinjan, in Assam, to Myitkyina, in northern Burma, barge them from there down the Irrawaddy River to Bhamo, and then truck them to the Burma Road and China. This roundabout way could possibly be shortened. Work was already in progress on a road to extend eastward from the coal mining community of Ledo, in eastern Assam, across northern Burma to link up with the Burma Road. The Chinese and British had agreed to cooperate in its construction when Chiang visited India the first week of February. Stilwell instructed Holcombe to help the British and Chinese who were preparing plans for this road in the office of Maj. Gen. Richard L. Bond, Wavell’s engineer-in-chief.6

On 3 March Stilwell flew to Chungking to set up his task force headquarters there. Three days later Chiang announced that Stilwell would head the Chinese Expeditionary Force, which during the past week had been moving into Burma to bolster the British forces, consisting for the most part of Burmese and Indian troops. All available hands were needed now in southern Burma, where the situation was growing more serious by the hour. On 6 March the Japanese occupied Rangoon. The British retreated northward toward Mandalay. Completing his staff assignments and command arrangements, Stilwell hastened to Lashio to assume control of the six Chinese divisions there. He had certain definite strategic aims. His most cherished plan was to drive the Japanese out of Rangoon and reopen the supply line to Kunming. Failing this, he hoped to dig in around Mandalay to protect the future line of communications from India across northern Burma to China.

Meanwhile, the War Department had begun sending some air reinforcements. On 2 2 February Col. Clayton Bissell, selected as Stilwell’s air adviser by Lt. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, commanding the Army Air Forces, left Washington for India to handle arrangements for receipt in the theater of several consignments of aircraft for the Tenth Air Force and for Chennault’s volunteers, about to be inducted

into the U.S. Army. In an independent action approved by Marshall, General Brett, Deputy Chief of Staff, ABDA Command, ordered General Brereton to evacuate doomed Java and reestablish the remnants of his FEAF task force at Karachi.7 Here, early in March, Brereton activated his base and training center. General Marshall made Brereton commander of the Tenth Air Force and directed him to provide combat air support to Chiang in China and to the British in Burma and at the same time make plans for supplying China by air. He was to be directly subordinate to Stilwell, although as regards the campaign in Burma the War Department expected him to “cooperate with the British as [they] requested.”8

Engineer Work Begins

Soon after arriving at Lashio, Stilwell directed Holcombe to join him. While waiting in his hotel room at New Delhi for a plane to take him to Burma, Holcombe got word that Stilwell had made him temporarily engineer of the Tenth Air Force. In his new assignment he would have to advise Brereton as to the most feasible way of providing the facilities the airmen needed. He and Brereton had to deal with several fundamental problems. Organization of a port of debarkation and of a training base at Karachi would require major improvements in facilities there. The 2,000-mile supply line to China would necessitate building or improving numerous fields capable of handling transports—particularly in Assam and in Yunnan Province in southwestern China. To accommodate American aircraft which would help to defend India, either bomber fields would have to be built in the central and eastern parts of the country or British fields taken over and improved. Providing adequate facilities for the Air Forces in the Indian subcontinent would necessitate a major construction effort. Holcombe worked in Brereton’s office, helping to draw up plans for a headquarters for the Air Forces at Willingdon Airdrome near New Delhi, expansion of Karachi Airdrome, construction of five bomber fields near Calcutta, construction of an air depot at Agra, and the building of four airfields in Assam for the airlift to China. Holcombe gave his preliminary layouts to the airmen for their approval. As soon as satisfactory drawings were ready, they were forwarded to the architects in British General Headquarters (India), who put them in final form.9

Since there were no U.S. engineer troops and none could be expected soon, the Americans had to turn to the British for construction. The reverse lend-lease procedure, as worked out between British and American headquarters in India, provided that major U.S. Army commands would send their requests for construction to General Headquarters (India). General Bond would then call upon the Royal Engineers to “put the work in hand” or would ask the government of India to assign the projects to

the Central Public Works Department or some other civilian government agency. Whether civilian or military organizations controlled a particular project, the work was usually done by Indian contractors employing their own labor gangs.10

Brereton and Holcombe could not fail to be impressed by the immensity of the Asian scene and its challenge to the engineers. In China, Burma, and India lived nearly half the human race—900,000,000 people—largely undernourished, unlettered, and indifferent to the issues which had brought the war to their homelands. The towering Himalayas isolated the Indian subcontinent from China, and spurs of that range, called the Hump by the airmen, shut off Burma from China. Throughout the year, malaria, typhus, intestinal infestations, and other serious endemic diseases sapped the vitality of native and newcomer alike. The monsoon rains, lasting from May to October, drenched Burma and much of India annually; the world’s heaviest rainfall, more than 400 inches a year, fell in the Khasi hills of Assam.11 In various ways the summer downpours would create engineering problems. Constant repair of the waterlogged roads would be necessary. Workmen would be scarce because they would be needed in great numbers for work on the rice and tea plantations. In general, land communications were far from ideal. In the 1,800 miles between Karachi and Assam, rail gauges changed four times. Nowhere in India were there long stretches of highway capable of sustaining high-speed truck traffic the year around. The scanty Burmese road and rail net was not connected with the transportation system of India. The long and virtually uncharted mountainous frontier between the two countries was an almost impenetrable jungle haven for primitive tribes. In China, the Japanese were in firm control of all the modern highways and most of the railroads of the country. Such control as Chiang’s government exercised was confined to the under-developed part of the country.12

In attempting to have bomber bases and transport fields constructed, Brereton encountered almost insurmountable obstacles. It seemed to him and to other Americans that GHQ (India), despite the threat of invasion, did not shake off its peacetime routine. The government of India, fearful of provoking Indian nationalist outbursts by stepping up demands on the country’s agrarian economy, appeared to show little energy in meeting requests for construction and materiel for the American forces. In a diary entry for 20 March, Brereton fumed, “... practically nothing had been done in the northeastern area on airfield construction. No one has shown any initiative in assembling labor. ...”13 A month later he complained to Stilwell of the “... lack of central

control and proper coordination in construction projects in Assam and Burma. There are on order various projects in these areas ... and all apparently have first priority. As a result ... progress is slow.”14

As March drew to a close, new disasters overtook the campaign in Burma. With the Allied front in the south crumbling, the defenders resumed their withdrawal up the Irrawaddy Plain. Unwilling to continue without Holcombe’s services, Stilwell late in March ordered him to finish his work for Brereton at once and report to the command post near Mandalay. Arriving there on April, Holcombe undertook various assignments. For a few days he was Stilwell’s liaison officer with the Chinese division in the Mandalay area. Then, after arranging with the British to allow the Chinese to use the railway to the north during the impending withdrawal, he rejoined Stilwell in mid-April. During the next two weeks, before the collapse of Allied resistance and the fall of Mandalay, he served on a number of liaison and reconnaissance missions.15

Establishment of a Services of Supply

The expanding scope of American projects in India pointed up the urgent need for an American logistics organization. In late February the War Department had directed the head of the U.S. Military Mission to Iran, General Wheeler, an engineer officer of wide experience, to report to Stilwell and assume the additional task of creating a “Services of Supply, United States Army Forces in India, Burma and China. ...” The War .Department instructed Wheeler to “initiate required action to push through to Gen[eral] Stilwell all equipment. ...” and to “Investigate ... and report upon such matters as special supply requirements; supplies locally procurable; special supply difficulties and availability of skilled labor.” Wheeler, whom Stilwell had regarded highly ever since their days at West Point, was to have considerable latitude in determining his mode of operation. He was the first of many engineer officers to achieve a prominent command position under Stilwell.16

During March and April, Wheeler, with a small staff borrowed from his Iranian mission, strove to establish order in the supply and construction situation in India. He worked out with British officials a program for expanding storage and dock facilities at Karachi and carried on discussions with members of Stilwell’s staff in India and Burma regarding the organization and responsibilities of the proposed services of supply. On 17 April, Stilwell agreed to a directive according to which Wheeler was to operate lines of communication from ports in India to the airfields in Assam and furnish technical advice to the Chinese Army in the operation of its communications zone. Brereton, disgusted with the

General Wheeler

slow progress of construction under reverse lend-lease and having no engineer troops in his command, suggested to Stilwell that all American construction be put under Wheeler to insure maximum effectiveness. On 24 April Stilwell charged Wheeler with all U.S. Army construction in India, Assam, and Burma. To provide him with at least the nucleus of an engineer force sufficiently flexible to perform either airfield or highway construction, Stilwell asked the War Department to send a general service regiment, an aviation battalion, and a dump truck company.17

In late April Wheeler began to organize his Engineer Section. His chief of staff, Col. Fabius H. Kohloss, an engineer who had come to India in February as a member of a War Department observer group, recommended setting up a section of seven officers. Whether that many would be available in the near future was doubtful. On 27 April Wheeler chose as his chief engineer, Maj. John P. Johnson, a member of the mission to Iran. On 27 May, he moved his headquarters from Karachi to New Delhi. Johnson remained in Karachi on another assignment. There was a rapid succession of chief engineers at New Delhi from the end of May until August. All had to get along as best they could with small staffs of two officers or less.18

In May Wheeler set up his field organization. Kohloss prepared a plan of organization calling for two base sections and two advance sections in India and one advance section in China. Wheeler put engineers over four of his five field organizations. Col. Paul F. Yount, formerly of the Iranian mission, took command at Karachi of Base Section 1, which covered roughly the western half of India. Maj. H. Case Wilcox, also transferred from the Iranian mission, went to Agra to set up Advance Section

in central India. Maj. Henry A. Byroade, recently arrived from the United States with a small party of Air Forces engineers, took charge of Advance Section 2, which included a large part of Assam. In early June another veteran

of the Iranian mission, Maj. Charles F. B. Price, flew to Kunming to establish Advance Section 3, which was to include the southern half of China. Only Base Section 2, with headquarters at Calcutta and including most of southeastern India, was not commanded by an engineer. Its chief was Col. Edwin M. Sutherland of the Infantry. In each section, the commander, directly subordinate to Wheeler, would control all engineer supply and construction activities. Although shortages of personnel made it impossible for the field commands to organize adequate engineer staffs, this lack was offset somewhat by the fact that engineers headed SOS and four of its major subdivisions.19

Construction Progress

Work was urgently needed at Karachi. This city had become the major port of entry for the American forces, since British shipping had already overtaxed harbor facilities at Bombay, and Calcutta was too exposed to enemy attack. When Major Johnson left his job as Engineer, SOS, on 27 May he became engineer of Base Section . He had the task of expediting a variety of projects designed to make Karachi an efficient base and port of entry. With contractors and native laborers working under him and the Royal Engineers, construction went forward on a 5,600-foot concrete .runway at the former civil airdrome and on two outlying fighter strips. Various improvements were under way at the New Malir and Landhi airports, twelve miles east of the city. Other projects undertaken during the late spring of 1942 were extensions to the wharves and warehousing in the port, remodeling of hotels to provide additional billets in the city, and construction of a cantonment for 20,000 men at Malir.20

There was a great need for engineer work in northeastern Assam. Arriving at his post in May, Byroade set out to organize the SOS effort to support the airlift across Burma to China. He found the British engaged in improving four airfields, known as the Hump fields. The area assigned to him, so crucial for the supply line to China and the defense of India, was a scene of confusion. The Japanese forces were approaching India. Retreating and disorganized Chinese troops were straggling over the frontier mountains; the natives were panic-stricken. The Royal Engineers and the Central Public Works Department, supposedly cooperating to prepare the needed airfields, were engaged in a bitter struggle for the control of construction. Fortunately, soon after Byroade’s arrival, General Headquarters (India) interceded and placed the Royal Engineers firmly in charge of work at the airfields. “The change,” Byroade formed Wheeler, “has been entirely for the better, as the military has many more means at its disposal.” Byroade was not alarmed by the absence of personnel with which to man his engineer section. He believed his participation in the airfield program should be “solely a matter of liaison ... in clearly establishing

the needs of United States Forces. ...”21

At Calcutta and in central India work made little headway. The exposure of Calcutta to enemy sea and air assaults obliged Wheeler to mark time there. Matters were critical in central India. Brereton was especially anxious to complete the large depot field at Agra and the bomber bases across northern India at Cawnpore, Fyzabad, Allahabad, and Gaya. Contractors were far behind schedule. The onset of the monsoon rains made it difficult to keep laborers on the job. Supervisors seemed lax about informing contractors as to specifications and priorities. Critical materials did not arrive either on time or in desired quantities. American airmen, forced to live in tents while awaiting completion of their barracks, became increasingly irritated over the slowness of the British effort.

The campaign in Burma had in the meantime come to its disastrous end. By the time Stilwell emerged onto the plains of eastern India late in May, the Japanese had overrun all of Burma except the northern tip and had occupied part of China’s Yunnan Province west of the Salween gorge. Contact between Stilwell’s elements in India and his bases in China was impossible except by air. All supplies, fuel, guns, ammunition, and men needed in China would henceforth have to be flown in. The critical lack of air facilities in India and China would necessitate a major construction effort. Early in June, Stilwell decided to consolidate engineer responsibilities under Wheeler. Colonel Holcombe, seriously ill with dysentery, to which was added malaria contracted during the harrowing, 3-week trek out of Burma, went on convalescent leave to Kashmir. Stilwell left Holcombe’s post vacant with the understanding that on his return to duty he would be assigned to the Services of Supply.22

The Broadening of Stilwell’s Mission

Since the plan for keeping China in the war would require efforts much greater than those contemplated earlier, Stilwell was faced with the necessity of broadening the scope of his mission. By the latter part of June he had begun referring to his command as a “theater” instead of a task force. On 6 July he formally set up a theater-type organization. He established a forward headquarters in Chungking and a rear headquarters in New Delhi. Wheeler and Brereton were his two major subordinate commanders. Although General Marshall approved the reorganization, no formal orders were ever published by the War Department concerning it. By mid-July Stilwell’s command was generally known as the China–Burma–India Theater. For that part lying in India and Burma, Stilwell was under Wavell. For the part in China, he was under Chiang, who, as ruler of China, was accountable to no one. Stilwell had other responsibilities. When he took over the personnel and the responsibilities of the

American Military Mission to China, he came under the direct command of General Marshall. He also served as President Roosevelt’s military representative in Chungking. Stilwell’s diverse and exacting responsibilities imposed on him numerous and sometimes conflicting obligations; the resulting confusion made more difficult the work of the engineers and hampered the development of an effective engineer organization.23

First Engineer Troops Arrive

Fortunately for Stilwell’s construction program, engineer troops were on the way. At the end of July, two units, the 45th General Service Regiment under Col. John C. Arrowsmith and the 823rd Aviation Battalion under Maj. Ferdinand J. Tate, disembarked at Karachi. Soon thereafter the 195th Engineer Dump Truck Company, commanded by Capt. Clyde L. Koontz, arrived. The landing of these units coincided with the heightening of domestic tensions in India, where nationalist firebrands were urging the natives to violence against British rule. With a minimum of fanfare, the SOS port authorities issued ammunition to the nearly 2,000 engineers, loaded them on trucks, and sped them to Malir Cantonment through the streets of Karachi, lined with “Americans, Quit India” signs. If the natives were not happy to see the newcomers, Wheeler and Brereton were. In a temporary departure from Stilwell’s policy of concentrating engineer resources in

Wheeler’s hands, the 823cI was assigned to the Tenth Air Force; its first job was the construction of a bomb shelter at the Karachi air base. Within a few days Wheeler’s staff had worked out plans for deploying the rest of the men. The dump truck company was placed on transportation detail at the port. Arrowsmith’s regiment was split. The 1st Battalion was held in reserve at Karachi to be sent wherever it would be needed in central and eastern India. The 2c1 Battalion was kept in Base Section to improve roads, erect buildings, and provide camouflaging. Since the engineer units arrived without their equipment, SOS was obliged to give them machinery from lend-lease stocks earmarked for China. Most of these items were of nonstandard types and in most categories ill-suited to the tasks ahead.24

On August Colonel Arrowsmith became Wheeler’s chief engineer. Borrowing officers from his own regiment, Arrowsmith filled out the undermanned SOS Engineer Section for the first time. He organized the office into four main branches, with seven officers usually present for duty. The Administrative and Supply Branches had the duties customarily assigned to such units. The Planning and Operations Branch carried out supervision and analysis of all construction in the field. The Utilities Branch had purely local jurisdiction over construction and utilities in the New Delhi area. The vastness of the theater and the almost complete dependence

on the local authorities made the task of Arrowsmith and his staff difficult.25

Soon after his appointment, Arrowsmith set out to inspect many of the projects for which the engineers were responsible. At New Delhi itself, the British were improving housing and hangar facilities for the Tenth Air Force’s section of Willingdon Airdrome. The work was a month behind schedule and the Tenth Air Force representatives were growing increasingly concerned. Arrowsmith took to the air to visit other projects. Across northern India, the Royal Engineers were continuing their expansion of RAF fields into bomber bases; in southern India they were developing the field at Bangalore and in central India the fields at Guskhara, Nawadih, and Pandaveswar, near Calcutta. Brereton had chosen Ondal, north of Calcutta, as his air service center and Agra, near New Delhi, as his main air depot. Progress at most projects was not satisfactory. At Agra, work was far behind schedule. The British stated that the incessant summer rains, the frequent Moslem and Hindu holidays, and the slow procurement of cement—which the British insisted on using for runways since they believed only concrete would stand up under the monsoon rains—had retarded construction. Arrowsmith returned to New Delhi in mid-August, convinced that engineer troops would have to be concentrated in the most vital areas—Karachi, Agra, and Assam.26

Capt. Robert A. Hirshfield, who replaced Major Johnson as base section engineer at Karachi late in July, was soon able to report fairly constant progress. Civilian contractors had under way a large number of projects, including workshops and parking areas at the port, 38 mess halls and 175 ammunition sheds at Malir, and parking aprons and an operations building at the civil airdrome. Early in August, the 2nd Battalion of the 45th Engineers was assigned to Hirshfield. He thereupon expanded his construction effort to include a 20-mile road westward from Karachi to the radar station on Cape Muari, wire entanglements and camouflaging at the various airfields in the area, and refrigeration and electric power plants.27 There were, to be sure, dark spots in the picture, such as shortages of cement and inadequate transportation. The local representatives of the Tenth Air Force registered their dissatisfaction with the quality of the concrete work and the flimsiness of the roofing put in by the native contractors. Nevertheless, of the critical areas in India, Karachi was, by the late summer of 1942, the least source of concern to the Americans.28

To expedite work at Agra, Arrowsmith on 23 August asked Wheeler to send the 1st Battalion and half of Headquarters

and Service Company of the 45th to supplement the efforts of the contractors. The men arrived on 5 September to take over construction of warehouses, repair shops, and steel hangars. Work was by this time about six weeks behind schedule. The assumption by the 45th Engineers of all trucking details for American forces at Agra somewhat relieved the British transportation problem. But the Royal Engineers continued to have trouble obtaining the necessary labor and materials to keep work going on the runways and other operational facilities remaining under their jurisdiction. Because of the Indian nationalists’ sabotage campaign, one engineer company had to be kept constantly on guard duty at a time when every man was badly needed for construction.29

Most critical of all was the situation in Assam. By late July Byroade’s Engineer Section had acquired two officers and two enlisted men, but the section’s many responsibilities made it impossible to spare more than one officer to prepare layouts and inspect work at the four fields. Byroade found himself increasingly concerned with the details of airfield construction, as the Royal Engineers turned to him time and again for decisions on the phasing of various portions of the airfield program. Contractors and laborers continued to make disappointingly slow progress during the long rainy season. Byroade could do little except to resort to friendly persuasion.30 The British did not fail to

point out that their efforts suffered from the inadequacy of materials and transportation. On 18 August Brig. Gen. Clayton Bissell, who had just succeeded Brereton as commander of the Tenth Air Force, took the 823rd off bomb shelter construction at Karachi and ordered them to Assam. By the end of September most of the men had arrived at their new location.31

Byroade welcomed Tate and the 823rd, for there was no end of work. About half of Company A was put on camouflaging the airfield at Chabua. The other half and Company B took over the loading and unloading of air freight at Chabua and the other three Hump fields at nearby Mohanbari, Dinjan, and Sookerating, from which planes took off for China. While such use of the aviation engineers was not to the liking of Byroade and Tate, there were compensating factors; the 823rd could be counted upon for efficient loading and unloading with a minimum of pilferage and breakage, and the assumption of freight handling by the Americans released large numbers of natives for return to airfield construction. Meanwhile, Company C, encamped at nearby Dibrugarh, began assembling urgently needed trucks. The surveyors, draftsmen, and truck drivers of Headquarters Company were also welcome reinforcements to Byroade’s hard-pressed Engineer Section. One recurring discordant note was the insistence of the Royal Engineers upon concrete runways. Byroade held out for asphalt, which was procurable not only from

lend-lease materials destined for China and stored in Assam but also from an oil refinery in the province. As far back as May, Byroade had attempted to reverse local British decisions to use concrete. By summer, he had succeeded in getting specifications for asphalt.32

With the end of the monsoon in October, the Japanese launched a series of air raids on the airfields in Assam. On the 25th of the month, about a hundred enemy planes bombed and strafed, concentrating their attacks on Dinjan and Chabua. The enemy airmen returned the next day for a second attack. Two days later they made a reconnaissance-in-force. The effects of the raids went far beyond the destruction of runways, housing, and parked aircraft. The ensuing panic materially reduced the number of native workmen at the fields. Meanwhile, the Americans were alarmed by the apparent apathy of the British. Colonel Kohloss, after witnessing the raids and their aftermath while on an inspection tour of the area, was especially critical of British laxity in airfield construction and repair; he noted that at one field Byroade’s engineers were repairing the runway hours before the British ‘garrison engineer” appeared with his coolies.33

Problems of Reverse Lend-Lease

By autumn the Americans had many complaints with regard to construction under reverse lend-lease. Elaborately departmentalized British civil and military offices seemed exasperatingly slow in untangling red tape and approving requests for construction. Delays in getting projects started were frequent. Few local officials would turn a hand before receiving the written “sanction” or directive authorizing construction. More than once American works suffered from the preoccupation of the British with their own projects. A noticeably weak link in the chain was the native contractor, as a rule poorly educated, little concerned with specifications or deadlines, and scarcely familiar with machinery. Further retarding the British effort was the shortage of supervisors, without whom the Indian laborer was almost certain to adopt a lackadaisical attitude toward his work. The last phases of an airfield project frequently ushered in an administrative crisis when it became evident that the British could not meet the target date. Arrowsmith would express his concern in appropriate British quarters, while his engineers in the field encountered the dissatisfaction of Air Forces commanders over the “failure” to finish air bases on schedule. It had been agreed at the outset that the British would build accommodations for the Americans on the same scale as for equivalent British units. Nevertheless, the airmen all too often sought greater refinements than those standards allowed. Their insistence on showers and sewerage at airfields caused several disagreements with SOS, which was carrying out construction according to theater policy. In general, Arrowsmith could point out that, while British standards must govern, American airmen were receiving more elaborate accommodations

than those they would have gotten under War Department specifications for theater of operations construction.34

Equipment and Supplies

Engineer troops assigned to construction were hampered by the scarcity of supplies and the lack of equipment. The units that had arrived in July had not received their machinery by fall. SOS had to provide them with makeshift allowances to enable them to get their work under way. For months, most of their equipment and a good part of their supplies came from the stockpiles of lend-lease materiel scheduled for China. This source furnished trucks, trailers, rock crushers, air compressors, road rollers, generators, power shovels, pneumatic drills, and concrete mixers. However, each diversion of lend-lease machinery was a major operation, requiring Chiang’s personal approval. Besides, the engineers had to put forth much effort just to find the equipment stored haphazardly at various points across India.35 The British were able

to lend the Americans considerable numbers of trucks and trailers. Lesser amounts of supplies and equipment were gotten through local procurement, diverted shipments, and distress cargo. But it simply was not possible to build up large stores. By the fall of 1942 the engineer supply officer of Base Section

had succeeded in assembling in the general depot at Karachi a small and unbalanced assortment consisting mostly of pioneer-type equipment and drafting supplies—the only stockpile of engineer materials and equipment belonging to the American forces in India.36

The Engineers in China

There was little activity in Advance Section of SOS in China. The Engineer Section, set up by Major Price on 4 July, consisted during the next few months of Lt. Francis C. Card. Card gave most of his attention to finding ways of improving the airfield at Kunming and planning new fields near the city. He persuaded the local officials of the Committee on Aeronautical Affairs, a department of Chiang’s government, to extend the runways at the Kunming field to about 6,800 feet, begin expansion of hangar and storage facilities, and construct a headquarters for Chennault’s airmen, now known collectively as the China Air Task Force. By September the Americans had worked out plans for two new transport fields, one to be built at Chengkung, just outside Kunming, and

another at Yangkai, forty miles to the north. Chinese civilian and military agencies were to be in charge of construction, and the Chinese Government was to pay for the work. Such nonoperational features as housing and recreational facilities would be paid for by reverse lend-lease. The hiring of contractors and the direction of work at the fields was to be the responsibility of the Committee on Aeronautical Affairs or of the Military Engineering Commission, a subordinate office of the Ministry of Communications, also a department of Chiang’s government. The Yunnan-Burma Railroad Authority, idle since the fall of Burma, was now given the job of helping to build the airfields. The

first two organizations were to employ civilian contractors; the Railroad Authority was to use both contractors and peasants, the latter to be conscripted by Governor Lung Yun of Yunnan. By October 1942 work was under way on the airfields at Chengkung and Kunming.37

Training

Having won Chiang’s consent for the organization of a Chinese corps in India to be used eventually for the recapture of Burma, Stilwell planned to provide the corps first of all with adequate training. He got from the British a camp which they had built at Ramgarh, about 200 miles west of Calcutta, to house Italian prisoners taken in the North African campaign. Here he assembled the Chinese survivors of the retreat from Burma and filled out their ranks with raw replacements flown in from China. Taking over Ramgarh in August 1942, the Americans found that much work had to be done to put it in shape. SOS, organizing the station complement, established an Engineer Section under Capt. George J. Mason to build access roads, firing ranges, utilities, and housing.38 One officer and 42 enlisted men of the 195th Dump Truck Company were at Ramgarh from August on, providing transportation and helping with the engineer phases of the training program worked out between Stilwell and the Chinese officers there.39 For the training program, Stilwell set up an Engineer Section under Lt. Col. Edwin B. Green, who would give basic and unit training. The program included a course for Chinese engineer officers on bridges, road construction and maintenance, mine warfare, battlefield recovery of materiel, rigging, knots, lashings, explosives, river crossing, engineer reconnaissance, camouflaging, field fortifications, mapping, water supply, and assault tactics. Green’s staff, consisting usually of over a dozen engineer officers, also helped organize a Chinese task force by setting up and training pioneer-type engineer units modeled after German pioneer organizations described in Chinese field manuals paraphrasing German training literature. Chinese officers

trained the Chinese troops, applying precepts conveyed, often through interpreters, by Green and his assistants.40

The close of October found the engineers at work in an area stretching from Karachi some 2,200 miles eastward into Yunnan. Numbering only 14 in late spring, their strength had risen to 1,986 by i October 1942. But even this force was hardly adequate to meet the demands of an airfield construction program embracing seven transport fields in eastern India and southwestern China and about twenty bomber fields scattered across northern India. Although the greater part of the work was being done by the Indians, British, and Chinese, U.S. engineer troops were applying their efforts in the most crucial links of the chain—Karachi, Agra, and Assam. Far too weak in personnel and equipment for the tasks at hand, the engineers had at least achieved an organization which was making the best possible use of available resources.

Ground Communications for a Campaign in Burma

Campaign Plans

While the engineers were striving to build airfields for Stilwell’s expanding air establishment, high-level planners in the War Department gave them an additional mission—that of constructing ground communications to support a future offensive in Burma. Since the close of the campaign in Burma, Allied strategic planning for developing overland communications across the foothills of the Himalayas had hung fire mainly because domestic turbulence in India was casting grave doubts on that country’s usefulness as a base for military operations. On 25 August 1942 General Marshall gave an impetus to planning for an offensive by warning the Combined Chiefs that only by reopening land communications across northern Burma could China be kept in the war and the Pacific front spared the disastrous consequences of a total collapse of Chinese resistance. During September, the War Department worked out a plan for a combined Chinese-British advance into Burma. By the beginning of October, the plan had developed to the point where it could be referred to the theater for detailed arrangements among American, British, and Chinese commanders. On 14 October, after receiving a radio from President Roosevelt stressing the need for operations to open the Burma Road, Chiang directed Stilwell to take the lead in planning for a concerted Allied drive to achieve that objective. In mid-October, Stilwell flew to New Delhi to confer with Wavell and arrange a series of conferences to work out a strategic plan, with I March 1943 as the date for the opening of the attack. Wavell informed Stilwell almost at once that, mainly because of logistical difficulties, the British could do no more than occupy the western fringes of Burma during the first part of 1943. The conferees consequently prepared a plan for clearing only northern Burma. As finally developed, the plan of campaign called for the brunt of the fighting to fall on the Chinese. Stilwell’s Ramgarh-trained Chinese, organized as

X-Force, would advance eastward from Assam, while a Chinese force to be known as Y-Force would advance westward from Yunnan. The meeting of the two would mean the expulsion of the Japanese from a large part of northern Burma.41

The Ledo and Burma Roads

The clearing of northern Burma would make possible the construction of a road to link India with China. With Wavell’s assignment of the campaign in northern Burma to Stilwell, Lt. Col. Frank D. Merrill, Stilwell’s G-3, suggested on 28 October that Wheeler’s engineers start to build a base at Ledo and gradually replace the British on their languishing road project. A road across Burma could be built during the course of the campaign and the completed portion used as a supply line. To build a road across Burma to link India and China would be an extensive undertaking. The most likely route ran east from Ledo to the Patkai Range on the Burmese border and then veered south to the towns of Myitkyina and Bhamo. From the latter it ran east to the Burma Road. The entire distance was about 500 miles. The rugged country from Ledo to Myitkyina, a distance of some 275 miles, was largely uncharted jungle. Beyond Myitkyina, a one-lane, dry-weather track extended to Bhamo. From there a one-lane blacktop road went to the Burma Road. The first 275 miles would require by far the greatest construction effort. The first stage of road construction by the Americans, Merrill believed, should be a short stretch running eastward from Ledo to the Patkais and then southward to Shingbwiyang in Burma, a total distance of about 120 miles. Shingbwiyang would be the jumping-off place for the coming offensive.42 On 29 October, Stilwell told Wheeler to carry out Merrill’s proposals, emphasizing that he wanted the road open to Shingbwiyang by I March 1943. “The importance of this mission is obvious,” he declared, “and far-reaching results depend upon its successful accomplishment.”43

Thereupon, Stilwell flew back to Chungking to persuade Chiang to assemble an expeditionary force along the Salween and to authorize early reconstruction of the demolished sections of the Burma Road in western Yunnan. The latter project was equal in importance to the building of a road out of Ledo, not only from the standpoint of its short-range usefulness as a tactical supply route, but also because of its eventual importance in the strategic line of communications linking India with China. On the surface, matters appeared to be progressing smoothly as Stilwell explained to the Generalissimo the Anglo-American plans for 1943. Chiang agreed to organize along the Salween a group of armies, 15 divisions strong—the Y-Force. But he reserved the right to cancel Chinese participation

in the offensive should the British Navy fail to demonstrate a “dominance” of the Bay of Bengal sufficient to prevent sea-borne reinforcements from reaching the Japanese in Burma. Anxious to get repair of the Burma Road started, Stilwell called Wheeler to Chungking in mid-November to open discussions with the Chinese high command looking toward formation of a services of supply for the Y-Force in addition to the development of a line of communications.44

Preparation for Work on the Ledo Road

Wheeler took immediate steps to get work started on a road from Ledo. On 29 October, he placed Arrowsmith in command of the Ledo base and road projects and instructed him to draft a plan of construction for Stilwell’s approval. Arrowsmith made determined efforts to put “the show on the road.” He spent five days in New Delhi in conference with members of Wheeler’s staff in order to get information regarding the project and the problems involved. Little was known about routes which might be followed. The plan was to use the “refugee route,” which the British had used in withdrawing from Burma. It was roughly the same as the one suggested by Merrill. The road when finished would be all-weather and one-lane with turnouts. In estimating troop requirements and the amounts of materials and equipment needed, Arrowsmith found the situation bleak. There were still but three engineer units in the theater. Only part of the equipment of the 823rd and 45th engineers had arrived, and only that of the 823rd was heavy enough for efficient road construction. During the first week of November Arrowsmith asked Wheeler to request from the United States, among other units, a general service regiment, a maintenance company, and a depot company. He sent a lengthy requisition to the supply depot at Karachi for items that would be needed. He suggested to Wheeler that the War Department be asked for several thousand tons of equipment, including 40 D-7 bulldozers, 30 H-20 steel bridges, and a 6-month supply of spare parts—all to reach Ledo by March 1943. On 5 November Arrowsmith flew to Assam as a member of a British-American reconnaissance party to collect data with regard to constructing the road and a base at Ledo. He soon formulated his general plans for building the road. On 7 November, his operations officer flew to Chungking to hand Stilwell a copy of the road construction plan. The theater commander approved it at once and radioed Wheeler’s requests for troops and equipment to the War Department.45

Implementing the plan would be more difficult than drawing it up. The 45th and 823rd engineers were alerted for movement to Ledo early in November; the work they were doing on airfields was to be taken over by the British. It

Native bridge on the refugee trail

would, however, be about a month before the American units would arrive at Ledo. To get the project started, the British in the middle of November put several hundred natives on the job of extending the existing road out of Ledo. Later that month, part of an Indian excavation company arrived to help. Arrowsmith directed Lt. Col. James W. Sloat, executive officer of the 45th Engineers, and Maj. Robert A. Hirshfield, Base Section I engineer, both members of the reconnaissance party, to initiate work on the road and base. On 19 November he returned to New Delhi with the report of the reconnaissance party and prepared to “arrange the details” of getting the work started. The British exhibited little enthusiasm for Stilwell’s plans for an offensive or for the construction of a road out of Ledo through the jungles of northern Burma. Wavell’s staff believed that the British military establishment in India could not spare the engineering and transportation resources even to tide the Americans over until March, when reinforcements from the United States would arrive. The British stated they had been taxed to the limit during 1942 to build or modernize 222 airfields, develop training centers and other installations

for the expanding Indian Army, and, at the same time, furnish materiel to the hard-pressed Eighth Army in Egypt. Weather, terrain, and disease would be formidable obstacles to any road construction project in Assam and Burma.46 To the British staff’s insistence that mud and malaria would drive the Americans out of Burma, Arrowsmith bluntly retorted on 24 November that he intended to carry out the road project “even if he had only one man.”47 The Ledo Road was started with a minimum of planning and few resources. As Arrowsmith observed later, “It was a case of kicking a cat out the door and telling him to scat.”48

Preparation for Work in China

Meanwhile, the Chinese showed little inclination to get on with preparations for an offensive beyond the Salween or for improving the Burma Road. Unknown to Stilwell, they had become enamored of Brig. Gen. Claire L. Chennault’s new plan for a vigorous air offensive aimed at destroying Japanese air power in eastern China and compelling the enemy to evacuate Chinese soil. This line of thought appealed to the Chinese because it involved little or no effort on their part and put off indefinitely the politically explosive task of modernizing the army. During the last week of November, Stilwell learned that the War Department was cutting in half his request for troops and equipment because of the shipping shortage. The engineer contingent would be substantially intact, but other categories would be drastically reduced or eliminated.49 Stilwell likened himself and Chiang to two men “on a raft, with one sandwich between ... [them] and the rescue ship ... heading away from the scene.”50

Despite the rather discouraging outlook, General Wheeler concentrated on organizing a communications zone for the Y-Force. After extensive conferences with the Chinese War Ministry, he decided on 26 November to place his chief of staff, Colonel Kohloss, in command of the new Eastern Section. Kohloss’ headquarters would be in Kunming. He was to work with the Y-Force headquarters wherever it operated. His primary mission was that of advising Y-Force in the organization and operation of its SOS. Arriving in Kunming with his staff at the end of November, Kohloss directed his engineer, Maj. Louis Y. Dawson, Jr., to work with the Yunnan-Burma Highway Engineering Administration, the Chinese agency responsible for rehabilitating and reconstructing the Burma Road in the rear of the Chinese divisions which would be moving southward against the Japanese in Burma.51

Work Begins on the Ledo Road

General Marshall, in steering the Ledo Road project through to its final approval

by President Roosevelt on 8 December 1942, indicated the reasons why War Department planners placed such great stress on ejecting the Japanese from northern Burma and on opening land communications with China. The great American objective in China, Marshall declared, was “the buildup of air operations ... with a view to carrying out destructive attacks against Japanese shipping and sources of supply.”52 A dependable overland line of communications with China was essential. But before this could be provided, the Chinese, with some help from the British, would have to advance from Assam and Yunnan across northern Burma and get control of the route for the road. So important did the Combined Chiefs consider the proposed operations in northern Burma that they gave them a priority surpassed only by that of the North African campaign, then in its critical phase. A most difficult matter would be supplying men and equipment in time for work on the line of communications. Marshall gave Stilwell “some hope” on 10 December that the needed 6,000 American service troops and 63,000 tons of road construction and maintenance equipment could be delivered at Ledo by early March.53

Arrowsmith pushed preparations for building the road. At the beginning of December he assumed command in the Ledo area. The British units, supported by a growing number of laborers, were barely making headway. An advance detachment of the 45th Regiment had arrived at Ledo late in November; the remainder of the unit and the 823rd Battalion were scheduled to arrive early in December. Arrowsmith, intending to take over activities around Ledo gradually, planned to leave most of the work on the road, for a time, in the hands of the Royal engineer already in command—an able colonel determined to do things his own way until the formal transfer of authority. Dissatisfied with the slow advance of the grading and the colonel’s emphasis on graveling, Arrowsmith soon moved up the date of the takeover to the first week of December. Relegating the British commander to a liaison role, he gave command of the road force to Colonel Sloat, who was henceforth “Road Engineer.”54 Discarding “boulevard specifications,” Sloat proceeded to carry out Arrowsmith’s instructions to “put the leading piece of equipment ahead as fast as we could and ... [build] the best road we could to keep up with it.”55 With the arrival of the 823rd and most of the 45th in the first half of December, work speeded up considerably.

On 15 December General Wheeler activated Base Section 3, with headquarters at Ledo. Arrowsmith was now in formal command of work on the Ledo Road, as it was henceforth called. At the same time he continued to be Engineer, SOS. For the time being, he, and Wheeler as well, were so preoccupied with reconnaissance and planning for the road that they had to leave their New

Delhi offices almost entirely in the hands of assistants. Since the frontier area was largely uncharted, several officers and men of the 823rd were sent to Arrowsmith’s headquarters to produce much-needed maps. Maj. James A. Walker, Arrowsmith’s supply officer in SOS, set up a supply depot in a group of brick godowns at Likhapani, four miles northeast of Ledo. Major Hirshfield took over as base engineer and started converting Ledo into a major supply point and staging area. Working closely with British civil affairs officers, he took over houses and tea sheds for use as quarters, offices, and depots. The Chinese divisions and American service units expected soon would be bivouacked on the tea estates. Hirshfield hired native labor to build more administrative buildings and warehouses and enlarge the railhead facilities at Likhapani.56

Of the various routes that might be followed, the refugee trail appeared best, since it reportedly had been used for many years as a caravan route and would therefore probably follow the easiest way into Burma. An alternative was the route of a proposed railway which had been surveyed about twenty years earlier. This was eliminated as a possibility because of the large tunnels and long river crossings which would be required. Arrowsmith decided to follow the refugee trail wherever possible. The British in building their highway out of Ledo had followed the railroad route; soon after taking over, Arrowsmith directed that the road builders switch to the higher ground of the refugee trail.57

By late December, the road team had taken shape. Out in front, a group of Tate’s 823rd engineers were in charge of reconnaissance. Several Royal Engineer surveyors helped to select the exact course the route was to follow. Most of the 823rd followed close on the heels of the surveyors, clearing a roadhead through the jungle. The unit’s six bulldozers, the only available machines with the power and traction to clear a trail, had arrived in India without blades, which were being sent from the United States on another ship. Four months after the 823rd arrived in India the blades had still not come. To get work started, Tate had borrowed a blade from a British engineer unit on the road. It was attached to the lead tractor. When the machine was returned to the rear for servicing or repairs, another was moved up and the blade attached to it. In back of the 823rd, the 45th did final grading and graveling. A British excavating company and a mechanical equipment section worked briefly on the road before withdrawing to British projects. Progress was gratifying to the Americans. The 823rd advanced a fresh graded trace five miles during the last week of December.58

By mid-January 1943, the lead dozer was thirty miles from Ledo and nearing the mountains. A more rapid advance was possible after Arrowsmith got two more blades from a training school in Lahore. Chinese troops moved in to

protect the road force; a battalion of infantry and a battery of field artillery took up positions beyond the Patkais near Shingbwiyang, and other Chinese troops were ordered to remain at least a day’s march ahead of the engineers. The road was rather winding. This was inevitable because of the way it was being built. The method was to bulldoze a narrow path through the jungle, move up all additional equipment to clear out trees and underbrush on both sides, and then fit the road into the best part of the clearing. Because the light D-4 bulldozers of the 45th could not always cope with the rugged terrain, detours had to be made around the many large stumps which the machines could not pull out. The men put temporary timber bridges across the major streams and installed culverts at the minor water courses. In the flat sections, the road could easily take two lanes of traffic, but on the sides of hills it was quite narrow.59 On 21 January Wheeler reported to Stilwell that graveling had reached Mile 26.60 The theater commander was jubilant, but agreed with Wheeler’s suggestion that satisfaction be kept “in the American family” to avoid embarrassment should the units on the road be unable to maintain their pace.61

Progress continued during February, but at a much slower pace. By the end of the month, the roadhead had reached Pangsau Pass on the Burmese border, 38 miles from Ledo, still some 80 miles from Shingbwiyang. The slowdown was caused mainly by the rugged terrain of the Patkais. Earthmoving was especially troublesome. The engineers had to apply greater and greater efforts to widening the road and sloping the high banks. In mid-March, a brief rainy spell—the “early monsoon”—temporarily halted work. An 8-mile stretch of the road in the mountains soon became so sodden that trucks could not get through. Tate had to use natives to carry supplies to the 823rd. After the weather cleared, operations were back to normal. By the end of the month, the leading elements were 48 miles from Ledo and still 70 miles from their goal.62

The monsoon season was approaching. Arrowsmith hoped to receive his first reinforcements before it struck. Early in March Shipment 4201 landed at Bombay; it included the 330th Engineer General Service Regiment, the 479th Engineer Maintenance Company, and a platoon of the 456th Engineer Depot Company. Only the depot platoon was on the road by the end of the month. It took over operation of the engineer depot at Likhapani. General Wheeler persuaded Chiang to send in the loth Chinese Independent Engineer Regiment, a crack outfit which reported directly to the Generalissimo. The Chinese engineers, who arrived in mid-March, cleared the jungle and did pioneering ahead of the 823rd. During March and April the 823rd’s blades and the D-7 tractors and other heavy equipment on order since November arrived at Calcutta and began moving up the rickety railroad to Assam. Whether the

blades and equipment would arrive soon enough before the rains to be of much good was doubtful.63

Early in April Stilwell visited Ledo. As he looked over the various projects with Arrowsmith, doubts rose in his mind. In a letter to Wheeler, he expressed the view that the buildings constructed for the base were not sturdy enough and suggested that a greater effort be made to provide better housing. He believed Arrowsmith was concentrating too much on pushing the road, when he should be expanding the system of access roads in the base and preparing supply trails for jeeps through the jungles to Chinese outposts along the eastern slopes of the Patkais. In order to have this additional work done, Stilwell was willing to accept the “sacrifice of a little progress on the road.” But, after considering the critical shortage of troops and equipment, he conceded that “there has been so much done here, and everybody is so willing and interested that I have no business to criticise anything. So I won’t.”64

The monsoon, unusually early, was in full swing by the first week of April. Viewing the extreme difficulties with mud slides and drainage in the Patkais, and realizing that his meager force was stretched too thin, Arrowsmith on 8 April instructed Colonel Tate to give top priority to sloping, widening, and ditching. Late that month, advance elements of the 330th Engineers came up to reinforce the 823rd at the roadhead. The 1st Battalion of the 45th Engineers then turned to road maintenance while the 2nd Battalion moved back to Ledo to repair the vital access roads before they disintegrated completely. By May, the engineers were struggling to restore or save more than 120 miles of roads in and out of the base. The rains did not cause as much damage to the bridges as had been feared. Some of the temporary structures turned out to be too low for the swollen streams and a number were washed away, but by the time the rains began, the permanent bridges were nearly ready. American and British engineers put steel spans over the larger rivers, while the Chinese loth Engineer Regiment built hand-hewn timber bridges over the smaller streams.65

The monsoon struck just as the condition of the equipment on the road was nearing an all-time low. There were almost no spare parts. A few pieces of machinery did arrive from Calcutta in April and May, but by far the greater part of Shipment 4201 would not be available until summer. In the meantime, the winter-long operations had taken their toll. By the end of April a third of the 823d’s tractors and trucks were awaiting repairs. A month later two-thirds of its tractors and half its trucks were out of service. The 45th Engineers fared no better.66 The rains were not so severe that all work had to be

stopped, but with their equipment in such a poor state the engineers would not be able to extend the roadhead much beyond Mile 50 during the remainder of the monsoon.67

Engineer Work in China

In China, likewise, work on the all-important roads was the main concern during the first months of 1943. Chinese and American officers were generally agreed that the main Chinese drive beyond the Salween would follow the route of the Burma Road toward Lashio. A secondary thrust would be made along the partially completed right-of-way of the Yunnan-Burma railway. The latter route left the Burma Road near Mitu some 225 miles west of Kunming and wound south through the mountains east of the Burma Road. Kohloss believed the Chinese should establish depots along the Burma Road—their main supply route—and put the road itself in shape. They should also build a highway from Mitu into Burma along the right-of-way of the railroad. At the same time, Kohloss strove to persuade General Chen Cheng, the Y-Force commander, to organize a services of supply. In the winter of 1942-43, Kohloss and Dawson set themselves the task of achieving these primary goals, despite such obstacles as official apathy in Chungking and Kunming, the runaway inflation of the Chinese currency, and the technological backwardness of the Chinese.68

Dawson’s main job was to help the Yunnan-Burma Highway Engineering Administration improve the Burma Road. As his first order of business, he set out in December 1942 on a trip down the road as far as the Salween to gather the data necessary for making intelligent plans and estimates. He discovered that the celebrated Burma Road, started by the Yunnanese administration in the 1920’s and completed by the central government in 1940, was not a highway in the American sense of the word. Construction had proceeded without benefit of specifications, with the result that each “hsien” or local district had built its section as economically as possible. The road was two-lane in some sectors, but poorly surfaced, and partially demolished as a result of the defensive measures carried out the previous spring. With a surface consisting for the most part of crushed rock and clay, with some sections asphalted but in poor condition, the road was dusty when dry and slippery when wet. Dangerous hairpin curves were frequent, grades were steep, and shoulders were eroded.69 There were fourteen passes with an elevation of more than 7,000 feet. The bridges, as a rule one-lane and usually lower than the level of the road, consisted of fairly sound masonry abutments, but some had superstructures of rotting wood. The more he saw, the more Dawson was convinced that only a major construction effort could put the Burma Road in shape

either as a supply route for the coming campaign or as the Chinese portion of a truck highway from Ledo to Kunming.70

Fortified with Dawson’s description of the road and his recommendations for improving it, Kohloss succeeded in getting Lt. Gen. Chen Chinchieh, commander of the SOS of Y-Force, to make an inspection tour of the road from Kunming to Paoshan, some 40 miles east of the Salween. The first week in February, Chen, accompanied by Kohloss, Dawson, and Dr. Lee Wenping, a senior engineer of the Highway Administration, set out on the 430-mile trip. Thus, the Americans had at last been able to get key Chinese officials “on the road”—two months after the Eastern Section was established. Kohloss discussed with Chen and Lee Major Dawson’s role in the proposed improvement of the Burma Road. The Chinese agreed to accept Dawson’s participation in their planning work. At the same time, the Highway Administration, complying with American urging, ordered a thorough road survey, the first in the road’s history.71 Having discovered that the Highway Administration had about a dozen pieces of mechanical equipment, including three American tractors, two German air compressors, and a British power shovel—all in poor condition—Dawson got the Chinese to promise that they would assemble this machinery and have it repaired.72

In the latter part of February Dawson and the officials of the Highway Administration completed their estimates of how much it would cost to transform the Burma Road into an all-weather, two-lane highway. Dawson brought to the meetings with the Chinese engineers his estimate of 79,823,400 Chinese dollars for improving the 370-mile stretch between Kunming and the Mekong River and 37,601,000 dollars for restoring the 226 miles of demolished roadway beyond the Mekong to the Burmese border, a total of 117,424,400 dollars, equivalent to $5,871,220 in American money at the official rate of exchange which fixed the Chinese dollar at 5 cents. The uncertainties caused by the runaway inflation in China were difficult to contend with. It was impossible to determine what the purchasing power of the money might be even in the near future. The Chinese, therefore, almost tripled Dawson’s estimates. Believing that their figures would not be accepted in Chungking, he persuaded the Highway Administration to reduce them by about 25 percent. The figure eventually agreed upon was 295,566,000 Chinese dollars. Late in February, this estimate was sent to the Ministry of Communications at Chungking with a request for an early allotment of funds.73 There was nothing to do but wait.

A long period of inaction ensued. A few laborers remained on the road performing desultory maintenance. When the April rains started, they withdrew to their homes. It was Dawson’s unpleasant duty to report periodically to Kohloss

on the progressive deterioration of the Burma Road. In May, the Highway Administration, in the throes of merging with the Yunnan-Burma Railroad organization, acquired a new director, C. C. Kung, who promptly installed his own group of railway-construction specialists. They had almost no knowledge of modern road machinery and little desire to see it used. Dawson encountered only indifference when he importuned the Chinese to have their rusty equipment repaired. The road survey, for which funds had been borrowed against future appropriations, was being carried out with neither centralized direction nor a common benchmark; the data gathered would represent an almost complete waste of time and money. In spite of Dawson’s insistence that final plans be formulated for the best utilization of the coming appropriation for improving the road, the engineers of the Highway Administration declined to bestir themselves on the grounds that Chungking would never make the appropriation. It would appear that the only solid engineering achievement of the first half of 1943 was a 160-mile reconnaissance of the route for the road out of Mitu to a point 50 miles west of the Mekong, carried out during April and May by an infantry officer, one of Kohloss’ deputies.74 The Americans, trying to persuade the Chinese to prepare Y-Force for action, were frustrated at every level of command. While Kohloss was able with his own small organization to construct and stock depots at Yunnanyi and Kunming, he could not get the Chinese to do anything toward organizing a supply service.

Underlying the official apathy was the Chinese disagreement with the basic American strategy for the theater, a strategy that emphasized the need for a successful campaign in Burma to make possible the establishment of ground communications between India and China. The Chinese, far more interested in aerial supply and air power, displayed an altogether different attitude toward airfield construction. Back in November and December 1942, Yunnanese authorities had impressed thousands of laborers to enable the Yunnan-Burma Railroad organization to complete the airfield at Chengkung. Chiang himself ordered a bonus paid to the conscripted laborers. By late January 1943 Advance Section 3 had three transport fields in operation at Chengkung, Kunming, and Yangkai. By spring Capt. Harry F. Kirkpatrick, Advance Section engineer, and his staff began making improvements at two fields near Kunming formerly used by Chennault’s volunteers—Chanyi and Yunnanyi. Each field originally had a runway and small hostel. Kirkpatrick extended the runway at Yunnanyi and put in more taxiways and hardstands at both fields. By 31 May major construction at Yunnanyi was complete. Progress was less spectacular at Chanyi, but this field had been in better shape from the start.75

The Office of the Theater Engineer

Ever since Colonel Holcombe had gone on convalescent leave in June 1942, Stilwell had been without an engineer on his staff. When Holcombe returned to duty it was as Wheeler’s deputy. The position of engineer was filled once more on 3 January 1943 with the arrival in New Delhi of Col. Francis K. Newcomer. Newcomer soon came to the conclusion that his office was little needed in India, where Arrowsmith, as SOS engineer, with the major engineer responsibilities and resources at his disposal, was “well established and well equipped” to handle all tasks. Because of the distance involved, Arrowsmith could exercise little control over the American construction program in China. Consequently, Newcomer in March transferred his office to Chungking. His functions included coordination with the Chinese military in matters relating to airfield construction for the Americans in China, policy making in such matters as mapping and supplying Chinese troops in training at Ramgarh and in Yunnan, and a “considerable amount of housekeeping for the forward echelon of theater headquarters.” Newcomer was able shortly after his arrival in Chungking to add an assistant theater engineer and three enlisted men to his office. Stilwell rarely consulted Newcomer, and there was little the latter could do to further the engineer effort in China.76

Airfields in India

Since the principal American effort in late 1942 and early 1943 was directed toward opening ground communications across Burma, the airfields in India received comparatively little attention. Work on them was beset with difficulties, and the slow rate of progress, especially on those in central India, severely strained relations among the engineers, Tenth Air Force, and the British. Keeping an anxious eye on the bomber fields near Calcutta, General Bissell during December and January repeatedly taxed the engineers with failure to inspect regularly the work being done by native contractors.77 Maj. James F. Hyland, area engineer at Chakulia, stated that he and his one assistant were giving “a prorata share” of their time to each of the five fields in their area. In Hyland’s view progress was not what it should have been, because of the inefficiency of many of the native contractors and the inability of the Public Works Department’s few engineers to give effective supervision.78

Work on the four Hump fields in Assam, left almost entirely to the British since the start of the Ledo projects, showed definite signs of floundering. The plan to complete work on the fields before the rains could not be carried out. From the American point of view, the failure of “slow acting and unsympathetic” echelons in British command