Chapter XII: The Drive Across the Central Pacific

Having seized the Gilberts, American forces were in a position to continue the major drive across the Pacific. Four thousand miles still separated them from Tokyo. There was but one way to reach the goal—seize enemy-held islands and build airfields and bases on them to provide support for the next assault farther west. But building airfields and bases would be a major construction job, especially when the work had to be done on isolated islands, 1,000 miles from the nearest supply base. A strategy that looked almost hopeless at the time of Pearl Harbor now held great promise of success. Many seemingly insurmountable problems in amphibious warfare of the type required in the Central Pacific had been solved. Naval transports and landing craft, particularly LSTs, ECMs, and Dukws, made possible the rapid loading and unloading of troops, supplies, and heavy construction equipment on distant islands where no docks or wharves existed. To expedite landings in shallow water, floating steel ponton cubes that could be bolted together to form piers of various lengths and widths, were developed. Equipment for distilling sea water, lacking before the war, and without which the maintenance of bases on waterless coral islands would have been impossible, was now available. Engineer construction had been simplified. Crossed runways and huge parking aprons were a thing of the past. Plentiful supplies of coral and landing mat made possible the expeditious construction of landing strips. Safety factors were kept to the minimum. The use of prefabricated buildings was widespread. Engineering had been adapted to amphibious warfare.1

The Marshalls

Plans and Preparations

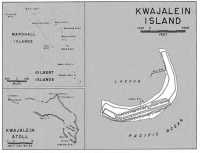

The first objective in 1944 was the Marshall Islands. Two thousand five hundred miles southwest of Honolulu and 500 miles northwest of the Gilberts, the Marshalls consisted of more than thirty atolls. (Map 23) According to information available at the time, Kwajalein Island, in the atoll of the same name, was well suited for airfield construction. A crescent-shaped coral island, it was 3 miles long and a mile wide. To the north, in the same atoll, were two islets, Roi and adjacent Namur, large enough for a base and an airfield. The Japanese had been active in the atoll. They had built an airstrip, a pier,

Map 23: Kwajalein Island

and warehouses on Kwajalein and had constructed an airfield on Roi and a pier and warehouses on Namur. On 20 July 1943 the Joint Chiefs directed Nimitz to begin planning for an assault on the Marshalls to be made the following January. On 1 September they set the date for the initial attack as 1 January; this was postponed in October to 31 January. Kwajalein was to be taken first. Thereafter, Majuro, in the southeastern part of the Marshalls, and Eniwetok, in the northwestern part of the archipelago, were to be captured. The attack on Kwajalein atoll would be a joint Navy-Army affair. The Army component, made up of elements of the 7th Infantry Division. under Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, was to seize Kwajalein Island. The 4th Marine Division would take Roi and Namur.2

Extensive engineer planning was necessary for operations in the Marshalls. Most of it was required for Kwajalein

Island. Three combat units were assigned to the assault phase and their functions clearly defined. The 13th Engineer Combat Battalion, under Lt. Col. Harold K. Howell, as the divisional engineer unit, would go in with the 7th Division. Each of the battalion’s three lettered companies was attached to a regimental combat team; in turn, each platoon was attached to a battalion landing team. Engineers and infantry of the battalion landing teams were trained to work together in special assault groups. Each engineer platoon was broken down into three provisional squads, each of which, including specially attached personnel from platoon headquarters, had about fifteen men. A squad supported a reinforced rifle company. Equipped with explosives, flame throwers, and hand tools, the engineers were to give close support to the infantry in the reduction of enemy strongpoints; since this would probably be their only function, they were to bring in no machinery except bulldozers during the first days. The 50th Engineer Combat Battalion, under Lt. Col. Leonard L. Kingsbury, if not needed in combat, was to turn at once to shore party work. In reserve was Company B, less one platoon, of the 02nd Combat Battalion of the 27th Division, which was to be ready for either combat or shore party work.3

To garrison the island, the same type of organization was set up as had been employed on Makin. Two Army defense battalions were organized—the 3rd and the 4th. Company D of the 34th Combat Regiment was assigned to the former; the 1st Battalion of the 47th General Service Regiment, the 854th Aviation Battalion, and a provisional engineer headquarters, to the latter. If necessary, elements of the garrison force engineers were to go in with the assault troops and help the 50th engineers with shore party work.4

The troops spent considerable time in training. Combat engineers received training in assault landings and coordination with the infantry. The men assigned to the garrison force got instruction in removing mines, operating equipment, installing refrigeration, using water distillation units, and fighting fires. Much attention was given to planning for the air base on Kwajalein. The engineers of Headquarters, Seventh Air Force, and in General Kramer’s office prepared most of the layouts. Those of the air engineers called for facilities for four medium bomber squadrons and their servicing units. Final plans were based on standard drawings modified to fit the conditions expected. The commanding officer of the 4th Defense Battalion spent much time and effort in helping to put plans for base construction in final shape. Engineer supply required a great deal of effort. Kramer’s staff prepared detailed lists of materials which were then reviewed by unit engineers and the base commander’s staff. Three shipping priorities were set up. The first included 221 prefabricated portable buildings, mostly kitchens and

mess halls, to be shipped with the assault forces. The second and third included, for the most part, materials for building warehouses, shops, and hangars.5

The Assault on Kwajalein

During the last week of January a task force of more than sixty vessels was on its way to the Marshalls. An engineer observer, Maj. C. N. Shaffer, aboard one of the transports loaded principally with engineers, infantrymen, and tankers, reported that “the trip ... was uneventful, the morale of the men was noticeably high, and their spirit on the evening prior to D-Day ... was at a peak.” Dawn of the 31st found the armada six to ten miles west of its objective. The four islets to the northwest of Kwajalein were attacked first, and, by midday, the two outermost ones were secured. Few Japanese were found on them. At the same time the two islands nearest Kwajalein were under assault. The first waves of infantry and elements of the 13th engineers, expert with rocket grenades, explosives, flame throwers, and wire cutters, had come ashore soon after 0900. Major Shaffer, landing on one of the islands shortly before noon, found the assault had met with no resistance. The fifty or so enemy soldiers had been evacuated the night before. The first waves of landing craft had crossed the coral reefs without mishap, but several of the later waves had a hard time. By early afternoon a number of boats were stuck and were forced to unload supplies and equipment some sixty yards short of the beach. It was especially difficult to get jeeps, trucks, and trailers to shore. Bulldozer operators helped pull the vehicles to the beach and then went to work to clear positions for the artillery. By 1600 the job was finished, and soon thereafter the 105s had completed their registration fires.6

Soon after 0800 the next day, the landing craft lined up in waves for the assault on Kwajalein. Infantry and engineers clambered down the ships’ nets to their boats and, protected by a powerful naval bombardment, sped toward the beaches in orderly formations. There was little enemy fire aside from a few antiaircraft shells. At 0930 the first troops came ashore. The preliminary bombardment had been effective. Fortifications near the water’s edge had been pounded into rubble; a seawall under construction had been smashed. The plan of attack called for two regimental combat teams to land abreast and move up the length of the island. Protected by a heavy naval and air bombardment, the landing teams advanced inland for 150 yards before meeting resistance. Then, amidst piles of rubble, they came upon a few small pillboxes, which the Infantry-Engineer teams, in their first test opt such installations, easily eliminated.7

Soon after the first elements had landed, the first shore party engineers came in with Col. Brendan A. Burns, the

shore party commander. Organizing two beaches for receiving supplies on the island’s western shore, the men collected supplies brought in by LVTs and Dukws and put them in a dump about 50 yards inland. Meanwhile, the combat engineers had fewer problems than expected, and some of them joined the shore party engineers. With their bulldozers they smoothed the rough ground from the beach to the western section of the highway skirting the island and repaired part of the highway. When darkness fell, the front lines crossed the island at a point more than one-fourth of the distance from the landing beaches to the northeastern tip. The next morning the advance continued past great mounds of rubble. Again, enemy resistance was slight. The Infantry-Engineer assault teams knocked out some pillboxes; the wrecked airfield was captured. By nightfall of the second day half of the island was in American hands.8

On the morning of the third day the troops, expecting to capture all of Kwajalein by nightfall, prepared to advance against the enemy holed up in the mile-long tip of the island. Japanese prisoners and natives warned that enemy defenses were strong. As the men advanced, they found them far stronger than had been anticipated. Amidst rubble and mounds of twisted wreckage were numerous defensive installations, many of them largely intact. Most common were air-raid shelters that had been converted into pillboxes; a considerable number were built of concrete, heavily reinforced with steel; some were constructed of coconut logs and sand. Nearly all of the latter were near the shore. Some of the shelters were occupied by as many as 75 men. Next in order of frequency were the pillboxes. Usually of concrete and hexagonal in shape, they had walls from one to oneand-one-half feet thick, but only a few had enough vents to permit all-around firing. In addition, there were circular cisterns, about seven feet high, apparently so constructed that, if necessary, they could he used as pillboxes, but their concrete walls were thin. The enemy troops in all these defenses were ready to resist to the death.9

The engineer-infantry teams were now put fully to the test. While the infantrymen shot at the apertures of the enemy strongpoints, the engineers ran forward with flame throwers, explosives, and bangalore torpedoes, then crawled to within inches of the structures, which they would prepare for destruction. The best procedure was to put a charge through an opening and let concussion do the rest. If a charge could be exploded in a pillbox, probably all the occupants would he killed. Flame throwers were effective if the men could get close enough to put one burst inside. Bangalore torpedoes, used rather infrequently, were poked through machine gun slits or pushed down ventilator pipes of the larger structures. The Infantry-Engineer teams had the support of tanks in the destruction of the more massive defense works. The tanks preceded the troops by about 150 feet, firing their

A Japanese pillbox, Kwajalein

75-mm. guns point-blank at the installation under attack, thus enabling the engineers and infantry to close in on it.

Though barbed-wire entanglements were rare, the Infantry-Engineer teams had been trained to deal with them also. If the advancing troops were held up by small arms fire aimed at the barbed wire from a pillbox, the infantry “buttoned up” the pillbox while the engineers ran or crawled to the wire, placed bangalore torpedoes, and withdrew. The ensuing explosion, with its noise and smoke, was the signal for the infantry to rush through the opening in the obstacle. Once safely past, the infantry again placed fire on the pillbox while the engineers moved forward with satchel charges and flame throwers. In some cases, the occupants of an installation, only stunned, would come to hours later and re-man their guns. Infiltrators would reoccupy some of the pillboxes that had been left intact. After the second day on Kwajalein, clean-up details were organized to reduce all fortifications to rubble.10

The engineer shore parties were carrying

on equally important if less dramatic work. As his staff, Colonel Burns had a provisional group headquarters of sixty-two officers and men. Under his command were the 50th Battalion, one battalion of the 47th General Service Regiment, and one company of the 34th Combat Regiment. Each company supported one battalion landing team. At the two original beaches on the western and southern shores of the island, reefs interfered considerably with unloading. Engineers making a reconnaissance of the lagoon side of the island discovered an excellent place for bringing in supplies, and by noon of the second day all shore party activities had been diverted to it. Rather slow at first, unloading speeded up on the third day, when cranes, trucks, and bulldozers were brought in. The shore parties were soon handling supplies faster than landing craft could transport them. About 300 yards inland, the engineers set up supply dumps and cut roads to them from the unloading sites. They constructed eight causeways in the lagoon to unload the heavier supplies and equipment. Enemy interference was slight. After the third day work went on without interruption even at night on the brightly lighted beaches.11

By the morning of 4 February more than three-fourths of Kwajalein was in American hands. The enemy, bottled up in a litter-strewn area 1,000 yards long and 400 yards wide, was in a hopeless position. But this part of the island abounded with defenses—shelters, pill boxes, machine gun emplacements, earth and log hunkers, and barricades against tanks—all of them still formidable even though they had been heavily pounded by naval guns, artillery, and aerial bombardment. Enemy resistance was tenacious; the fighting, savage. To the troops the action seemed “indescribably chaotic; it was like trying to fight your way across the landscape of a nightmare.”12 Nevertheless, the advance continued. At four in the afternoon General Corlett radioed Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner, commander of the Joint Expeditionary Force: “All organized resistance ... has ceased.”13

Majuro

The assault on Majuro, in the southeastern Marshalls, made on 31 January, began with the disembarkment on the atoll of a battalion landing team of the 106th RCT, 27th Division. Two engineer units went in with the assault forces—the 2nd platoon of Company B of the 102nd Combat Battalion to support the infantry, and Company B of the tooth Combat Battalion to do shore party work. The BLT commander with a special staff, including the commander of Company B of the tooth engineers, went ashore on the major island of the atoll for a reconnaissance. The party found large quantities of construction supplies and explosives, including many 5-inch and 8-inch naval shells. There were no booby traps or mines. Japanese installations were

fairly extensive, but only one enemy soldier was found. The engineers destroyed the unexploded naval shells, began clearing away the wreckage, and prepared to rehabilitate the facilities of the island.14

Eniwetok

Some 325 miles northwest of Kwajalein, Eniwetok atoll consisted of about thirty islets arranged in an almost perfect ring, twenty miles in diameter. Plans called for an assault by Army and Marine units on three of the islets, Eniwetok and Parry in the south and Engebi in the north, and the subsequent construction of a naval base. After the unexpectedly rapid capture of Kwajalein, Admiral Nimitz decided to move up the assault on Eniwetok, originally scheduled for about 1 May. Begun on 3 February, preparations for the stepped-up attack were completed twelve days later and the assault force set out for its destination; exact planning in this short time had not been possible.15

The marines came ashore on Engebi on 17 February. Two days later the 106th Regimental Combat Team, less a battalion landing team, arrived off Eniwetok. Company B, less one platoon, of the 102nd Combat Battalion, provided combat support, and the 104th Combat Battalion, less one company, served as shore party. The 102nd engineers, most of them organized in squads of sixteen men, had been teamed with infantry platoons as on Kwajalein and equipped with flame throwers and demolitions. Progress was slow against such enemy pillboxes and fortifications as remained after the bombardment. Eniwetok was one of the highest islands in the Marshalls. Because underground defenses were deep and “well-recessed,” few of them had been detected on aerial photographs. Infantry-Engineer teams again destroyed pillboxes, emplacements, and dugouts with demolitions and flame throwers. Operations on Parry Island, to the northeast of Eniwetok, were similar. Parry was cleared in one day.16

Shore party work was carried on as on Kwajalein. The I04th Battalion went in early on Eniwetok. Company C, the first unit to hit the beach, came ashore six minutes after the initial wave of infantry landed; it was quickly evident that the engineers had arrived too soon. Since the Japanese were putting up unexpected resistance in back of the beaches, congestion of troops and supplies at the landing points was marked. Only after more than two hours had passed was any cargo brought in for the shore party to handle. The engineers cut ramps through the high banks in back of the beaches so that tanks and trucks could move inland more easily. They set up water points, collected discarded equipment, and buried enemy dead. On Parry Island, Company C of the 104th performed similar duties.17

Base Construction—Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Majuro

With the end of organized resistance on Kwajalein, the commander of the garrison force took over and directed that work on the airfield and base facilities begin. The most important job—the building of the airfield—was the mission of the 854th Aviation Battalion. The unit had arrived off the island on 30 January. Two days later Lt. Col. Herbert E. Brown, Jr., the commanding officer, with members of his staff and four survey crews, came ashore to make initial surveys for the runway. The best site they could find was the one the Japanese had selected for their field. The runway was a heap of rubble, littered with live shells and grenades. “We experienced some close calls from sniper fire and random shots from the direction of the battle, but suffered no casualties,” wrote Colonel Brown, “and surveying proceeded with little interruption.” When the first equipment operators came ashore with their bulldozers on 2 February they headed straight for the airfield, cleared away debris, and filled in bomb craters. Most of the battalion did not come ashore till 6 February. The next day around-the-clock operations began. The strip was to be coral surfaced not only because the Air Forces preferred this to steel plank, but also because coral was plentiful. The main problem was to locate satisfactory deposits. The aviation engineers found coarse coral and sand in the center of the island, which they scooped out with a dragline. A more difficult job was locating satisfactory material for surfacing. After days of reconnoitering, the men found a satisfactory layer about one foot thick, some five feet underground. Carryalls placed it on the runways. To determine the bearing qualities of the material, a strip seventy-five feet long was constructed with two layers of well-compacted coral rock, topped with a lighter surface layer. The engineers tested the strip with a 20-ton crane loaded with steel mat, the closest approximation to a B-24 that could be obtained with the material and equipment on hand. Even after the crane had passed 150 times over the compacted strip, the latter showed no visible deflection. The adjoining subgrade showed a deflection of three-fourths of an inch for the same number of trips. On 12 February a Navy plane landed on the runway and took off without difficulty. By 17 February, a 5,000-foot strip had been cleared, graded, and surfaced sufficiently to be suitable for all types of aircraft then in the Central Pacific. On the 21 st, heavy bomber squadrons began carrying out regular tactical missions from Kwajalein. During their first month on the island, the aviation engineers built seventy-six acres of runways, taxiways, aprons, and hardstands.18

Although Eniwetok atoll was to be primarily a naval base, Army engineer units helped build it. The engineers did most of their work on Engebi. The 3rd

Defense Battalion, the garrison force for the island, included the 1st Battalion of the 47th Engineers, numbering about 1,800 men. They were to start work on the airfield and continue with the job until relieved by a naval construction battalion. The Japanese airstrip, with a reinforced concrete runway four inches thick, was repaired, and by 25 February a 3,000-foot fighter strip was usable. Progress was not as rapid as it might have been for a number of reasons. The engineers had to remove a large number of unexploded bombs because ordnance personnel was lacking. There was also a serious shortage of supplies, partly because of a difference of opinion over who should supply the island—one of the consequences of the speed-up in operations.

After a naval construction battalion reached Eniwetok, some of the 102nd and 104th engineers remained to help construct the naval base. They were at first used in an inefficient manner. Their main jobs were to straighten out supply dumps for the infantry and bury enemy dead. The engineers pointed out to the naval commander that little work was being done on the naval base and that they could help in base construction with their heavy equipment. The atoll commander agreed, and the combat engineers set out to help the Seabees. Early in March they began an extensive construction program on an around-the-clock basis with 12-hour shifts, erecting Quonset huts, clearing areas for runways, taxiways, and roads, blasting coral for surfacing, and building revetments. The naval commander gave the engineers tentage and lumber to enable them to build a semi-permanent camp for themselves, including screened mess halls, kitchens, latrines, and a floor for each tent.19

On Majuro, meanwhile, the engineers continued to be busy. They helped the infantry unload supplies, cleared and repaired a road running from the north to the south of the island, and, within a few days, had established supply dumps, waterpoints, and camps. They then aided the Seabees in building a minor base. They remodeled and repaired a Japanese pier, resurfaced roads with coral and sand, built causeways between a number of islands, and helped in the construction of the airfield. The Army engineers left Majuro at the end of February for Oahu; the base was henceforth operated by the Navy.20

Kwajalein Island remained the scene of greatest activity. On the lagoon side near the northeast end of the island, the engineers rebuilt Nob Pier, 1,600 feet long, where five LSTs and numerous smaller craft could unload at one time. They also rebuilt a small pier, 250 feet long, near the center of the island on the lagoon side. By June 1944 they had provided storage for 800,000 barrels of gasoline, extensive camps, numerous administrative buildings, and hospitals. A network of coral-surfaced roads crisscrossed the island.

Construction was not carried on without some difficulties. Engineer planning

had been incomplete, and changes made in plans by higher headquarters after construction began complicated the construction effort. It had not been anticipated that so many tons of rubble would have to be cleared away before work could begin. Engineer supplies were not received rapidly enough, and unloading was not always in accordance with priorities that had been established. The Air Forces insisted on having tons of its supplies moved across the beaches before badly needed engineer construction equipment was brought in, even though the air supplies could not be used until the airfield was operational.21

Logistical Support From Hawaii Organization

In Hawaii, during the first months of 1944, the dual engineer organization of department and district under General Kramer continued to provide support for the combat zones of the Central Pacific Area. Colonel Wisner continued to be in charge of the district office; Colonel Brown, of the department office. Colonel Brown’s staff was principally engaged in planning; the district office supervised construction in Hawaii and furnished supplies. The building program, while tapering off, was still considerable. Some of the work was now being done under lump-sum contracts; by i July there were fourteen such contracts in effect. Engineer troop units, responsible to General Kramer, were being used more and more to replace civilian labor.22

Construction

In the first months of 1944 quite extensive work was still required on airfields because of the anticipated expansion of the Air Forces in the Central Pacific. In February the airmen proposed far-reaching improvements to fields on Oahu and the outlying islands. Some required more housing; most needed additional parking aprons. Much construction was required aside from that for the Air Forces. Still extensive was the need for warehousing and refrigerated storage space. During April the engineers provided 491,360 square feet of the former and 46,800 cubic feet of the latter. By the end of that month the demands for cold storage space were met for the time being, but the engineers were scheduled to provide an additional 954,968 square feet of warehousing during the next three months. Because of the steadily increasing quantities of cargo arriving at Honolulu, more piers were needed at Kapalama Basin, and construction of the piers at the basin continued. More hospitals were urgently needed. Three of the largest schools in Honolulu were still being used as hospitals, two of them as units of Tripler General, the largest Army hospital in the islands, which was filled to overflowing. Tripler itself, because of its age and design, was no longer satisfactory. The engineers had begun preliminary surveys for a new structure in 1943, and Kramer was now convinced that the time had come to begin long-range planning for a new Tripler Hospital and for other hospitals as well. The War Department did not approve the construction of new hospitals, but directed that planning could

begin. A continuing problem was the deterioration of the roads in the islands, particularly at Oahu. Conferences were held, but, as before, little or nothing was done to improve the roads.23

The Hawaiian Constructors

Negotiations between the Honolulu District and the Hawaiian Constructors to arrive at a final settlement of the contract dragged on. By late 943 the Engineers had been able to show additional progress. In mid-October, agreement had been reached as to the completion status of the work on 31 January 1943 and the estimated cost of the projects not covered by the contract. In January 1944 substantial agreement was reached on the estimated cost of the changes made in the basic contract and the first forty-three supplemental agreements. Still a bone of bitter contention was the fee. The contractors continued to feel they were entitled to special compensation because the government had terminated the contract just when they were making strenuous efforts to fulfill their obligations. The engineers, particularly Kramer and Wimer (the contracting officer), thought their demands unreasonable. In mid-February, negotiations reached an impasse.24 The contractors believed they were not being treated fairly and voiced their complaints to General Richardson, stating they had “not been able to obtain from the Contracting Officer a satisfactory explanation of his actions, which appear to be direct and clear violations of the original contract, the change orders and supplemental agreements approved by the War Department in Washington, D.C. ...” The contractors went on to say that, in their opinion, “. . the action of the Contracting Officer is so arbitrary and obviously erroneous that we must construe it as an act of bad faith motivated by bias and prejudice and intended to injure the contractor.”25 General Richardson expressed the view that “... it would appear that there does not obtain between the respective parties that degree of mutual confidence which is deemed essential to an early settlement of the contract.” He directed Kramer to confer with the contractors’ representatives and, having done so, explain why settlement of the contract was “so unduly prolonged.” The contractors were permitted to tell their side of the story at the meetings held early in March. Late that month the Office of the Chief of Engineers, at General Richardson’s request, sent two experts in cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contracts—Harry W. Loving, head of the Price Adjustment Branch, and Col. Clio E. Straight, chief of the Contract and Claims Branch—to Hawaii to review the Hawaiian Constructors’ contract.

On their arrival in Honolulu, one of Loving and Straight’s first jobs was to examine the records in the Hawaiian offices of the inspector general, the judge advocate, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Military Governor. General Kramer had voiced the suspicion

that the contractors might have been guilty of fraud, having arrived at this view because cost estimates for many jobs, for no apparent reason, had been increased by 10 and sometimes even 20 percent. Loving and Straight immediately and thoroughly studied the possibility of fraud but found no evidence of it. On 5 April Kramer, Wimer, Loving, and Straight held a meeting. “We have come to the conclusion,” Loving and Straight reported, “that the situation here is not extraordinary, not entirely unusual in that a lot of fixed fee contracts were confused [and] disagreements resulted ... the contractor in many such cases comes to the conclusion that the contracting officer has acted in bad faith, ... contractors many times, not having previously worked under fixed fee contracts, don’t always understand their rights and there is sincere disagreements on all sides.”26 Loving and Straight spent several weeks more in their investigations. Early in April, they went to Canton and Christmas with Capt. C. D. Baker to inspect the work which had been done on those islands. Early in May, they flew to Port Moresby, New Guinea, where they talked with Sverdrup and Robinson and learned of the difficult conditions the contractors had had to contend with in Hawaii. Meanwhile, progress was made toward a settlement. In May, the Engineers and the Hawaiian Constructors reached a final agreement. The total cost of the work was set at $112,031,375. The fixed fee was $1,2 15,597, plus a supplementary fee of $1,060,000 resulting from termination. Purchases of equipment by the government were considered binding. The contract was exempted from renegotiation.

By this time interest in the contract of the Engineers with the Hawaiian Constructors had become nationwide. It was touched on by a number of governmental committees delving into the background of the Pearl Harbor attack. It was thoroughly reviewed by the Army Pearl Harbor Board, the principal members of which were Lt. Gen. George Grunert, then commanding general of the First Army and Eastern Defense Command; Maj. Gen. Henry D. Russell, an infantry commander; and Maj. Gen. Walter H. Frank, of the Army Air Forces. From 20 July to 20 October, members of the Army board heard testimony from civilians and officers in Washington, San Francisco, and Hawaii. Colonel Wyman, then commanding officer of Cherbourg Base Section in France, testified at Fort Shafter on 14 September and Col. Bernard L. Robinson, who had flown in from Hollandia, was heard the next day. Many others who had worked in the Honolulu District were questioned.27

The Army board, in its report made public after the war, did not deal gently with Wyman as Honolulu District engineer,

nor with the Hawaiian Constructors. It charged Wyman with poor administration, with causing inexcusable delays in construction, and with showing favoritism toward the grossly inefficient Hawaiian Constructors. Much was made of the fact that Hans Wilhelm Rohl, president of the Rohl-Connolly Company when the original contract was signed, was a German alien and did not become an American citizen until a few weeks before Pearl Harbor.28 Additional investigations and a judicious review of the evidence raised doubts that the charges of the board could be substantiated. Secretary Stimson stated that nothing indicated “that any conduct on the part of Colonel Wyman or of Rohl or of any of the other contractors in Hawaii contributed in any way to the Pearl Harbor disaster.” It was not illegal to give a defense contract to a firm, one or more of whose officers was an alien; the law merely prohibited showing secret plans and specifications to an alien. No evidence was adduced that Rohl ever saw such plans or specifications before he became a citizen. There was no convincing proof that Wyman had shown undue favoritism to the Hawaiian Constructors or had awarded them contracts against the best interests of the United States. There was no evidence of fraud. The confusion, waste, and slowness in defense construction that existed before and after Pearl Harbor could not be blamed on one arm or service, much less on one man. Stimson conceded that Wyman was guilty of indiscretion, adding that there was “creditable evidence” that the social and personal relationship of Rohl and Wyman was quite close, and that “Colonel Wyman acted unwisely in permitting this close association to continue during the progress of the work.” This, together with Wyman’s undiplomatic handling of some people, unnecessarily added to his difficulties, which would undoubtedly have been only a fraction of what they were had they occurred in an inconspicuous place or at a less critical time.29 Many in the Army considered Wyman a capable officer. In 1942 he was recommended for the Distinguished Service Medal for his services in Hawaii and subsequently he received the Legion of Merit for his services in Europe.

Maps

Mapping units had an increasing work load in 1944. “We have been putting out a tremendous number of maps here lately ... ,” Kramer wrote in late 1943 to Col. Herbert B. Loper, head of the Military Intelligence Division of the Chief’s Office. “Both the 64th Engineers and the old Department reproduction plant are sorely taxed.” Still, with only small islands to be mapped, the Central Pacific did not require a great number of mapping units. Late in 1943, Kramer had asked for a GHQ topographic battalion, a type of unit which had substantial amounts of equipment and could produce and reproduce large quantities of maps. The Corps had only four such units and could spare none for the Central Pacific. Loper

suggested that Kramer take one of the Army topographic battalions instead. These units, with less equipment, some of it mobile, produced fewer maps, but they had recently been reorganized to meet more adequately the demands of modern war. Their photomapping platoons had been expanded into companies and the survey companies cut to platoons. The Office of the Chief of Engineers decided the 651st Topographic Battalion, Army, would best meet the needs of the Central Pacific. Kramer wanted the 651st to merge with the 64th Topographic Company and take the latter’s number because of the 64th’s fine record. The 651st arrived in Honolulu in April and was thereupon absorbed into the 64th, which was then reorganized as a battalion. The new and enlarged unit of 451 men, under the operational control of Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Twitty, chief of J-2 of the Joint Staff, went to work on maps of the Marianas and the Carolines.30

In February 1944 Colonel Loper suggested that the 29th Topographic Battalion, GHQ, stationed at Portland, Oregon, help make maps for the Central Pacific. He believed this unit could be of substantial aid in the preparation of some of the badly needed large-scale maps of the Marianas and Carolines. The Navy would supply the photographs. Kramer thought Loper’s suggestion an excellent one. It proved, moreover, timely. The troops on Kwajalein had just found a fairly complete set of maps of all Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific, mostly at a scale of to 50,000, containing a wealth of hydrographic and topographic detail. These maps could be compared with aerial photographs of the Marianas, particularly of the islands of Saipan and Tinian, just coming in. The 29th was given the job of making maps for the Central Pacific. Using aerial negatives received from Hawaii, the men compiled preliminary topographic maps of the islands of the Central Pacific, then sent the drafts to the 64th TopogTaphic Battalion, which put them in final form, making use of the latest intelligence data. The engineers could do little to determine what specifications would be used for aerial photography, since Navy squadrons took practically all the pictures. But the engineers and naval fliers did try to work out a plan whereby photographs would be available for maps sufficiently far in advance of scheduled assaults to “… insure the availability of adequate detailed maps for planning, as well as for operations.”31

Training

By 1944 training schedules for engineer units in Hawaii were rather extensive. Since the troops in the Islands might be sent to any part of the western Pacific, all divisional engineer units received a week’s training in jungle warfare. Included were scouting and patrolling, working with dogs, close-quarter

fighting, stream crossing, and placing and deactivating mines and booby traps. Two officers, who as naturalists in civilian life had studied the islands of the Pacific, gave the men pointers on how to live in the jungle. Their basic idea was that the jungle, far from being something to be feared, should be regarded as the “friend and protector of man,” since it could be made to provide shelter and food. Exercises were held in areas of the Hawaiian Islands where heavy tropical growth existed and could provide a realistic background. At the Waianae Amphibious Training Center on Oahu, most engineer units were given a week’s refresher course in amphibious landings. Included were exercises in embarkation, debarkation, and swimming with equipment. Training was completed with a battalion exercise at night on the beach with live ammunition. There were, in addition, many specialist schools to provide instruction in such subjects as mine clearance, water distillation, refrigeration, and the operation of mechanical equipment. The mine clearance school, surprisingly enough, by the fall of 1944 had more than forty hard-to-get Japanese mines and various types of fuses—enough to lay a small mine field for the trainees to practice on. The school’s commanding officer explained that having long and unsuccessfully tried to get Japanese mines through official channels, he had finally gotten some by trading his liquor ration for souvenirs brought back by the troops from the combat areas.32

Reorganization

When General Richardson visited Washington in February, he was successful in obtaining War Department approval for a major reorganization of his headquarters. What he had wanted was an “integrated communications zone command.” He planned to have General Kramer as his theater engineer; Kramer would plan for and exercise technical supervision mainly over engineer operations in the combat zone. At the same time a chief engineer would be needed to provide technical supervision over engineer work in the communications zone. In response to Richardson’s request of 29 March for Loper, Reybold released him for assignment to the Islands. In May Kramer consolidated the two offices of district and department engineer, which henceforth were designated the Office of the Engineer, CPA. Late in May, Kramer returned to the United States because of poor health. In June Colonel Loper arrived and became Kramer’s replacement. On the 29th of that month the logistics organization Richardson had wanted was established with the activation of the Central Pacific Base Command (CPBC). But for the time being, no change was made in the engineer organization in the Hawaiian Islands, and no engineer was appointed. to exercise technical supervision over engineer work in the Central Pacific Base Command.33

The Marianas

Plans and Preparations

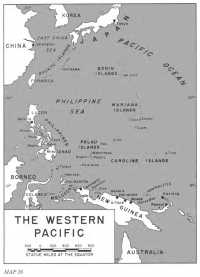

In mid-January 1944 Admiral Nimitz released the general plan of campaign approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff for the latter part of the year. The main Japanese bastion to be seized was Truk, one of the Caroline Islands, and the target date for the assault was 15 June. After Truk had been taken, three islands in the Marianas—Saipan, Guam, and Tinian—were to be captured. These islands, 3,800 miles west of Hawaii, were a most important objective. They would provide a site for an advance naval base for the Fifth Fleet, thus enabling it to attack and destroy Japanese warships and transports and eventually gain control of the rest of the Central Pacific. Air bases in the Marianas would help isolate and neutralize the remaining enemy-held islands in the central Carolines. Most important of all, the Marianas, only 1,500 miles from Tokyo, would be ideal sites for airfields for the B-29’s, now coming off the production line in quantities. Capture of the Marianas was scheduled as the concluding phase of the 1944 campaign. Initial planning centered almost entirely around Truk, a base that had to be captured in order to safeguard the American flank in an assault on the Marianas. In a series of powerful carrier thrusts in February, the Navy exposed the vulnerability of that enemy bastion. Truk could be bypassed. The Joint Chiefs, in a directive sent to Nimitz and MacArthur on 12 March, directed that the attack on the Marianas begin on 15 June. On 20 March Nimitz issued a staff study for FORAGER—the code name for the conquest of the Marianas—and detailed planning soon got under way in full force for the capture of Saipan and Tinian, the main Japanese islands in the group, and for the recapture of Guam. D-Day for Saipan was to be 15 June; for Guam, 18 June. The V Amphibious Corps, consisting of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, with the Army’s 27th Infantry Division in reserve, was to take Saipan and Tinian. The III Amphibious Corps, made up of the 3rd Marine Division and the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade, with the 77th Infantry Division in reserve, was to take Guam. Marine Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith was to have tactical command of all troops ashore on the three islands until the tactical phase was completed, and he would be directly responsible to Vice Adm. Richmond K. Turner, who commanded the joint Army-Navy-Marine task force. The Army would have primary responsibility for base development on Saipan. The Army and Navy would be jointly responsible for base construction on Guam. The Navy was to be responsible for base construction on Tinian.34

The Engineers had begun long-range planning for operations against Truk in January. When the decision was made to bypass that atoll, they concentrated their studies on the Marianas, directing most of their attention to Saipan. That island, like others of the Marianas, except

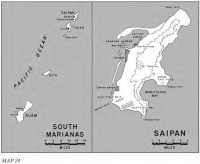

Guam—a U.S. possession since 1898—had been held by the Japanese since World War I. Information about Saipan was meager. No aerial photographs were to be had. The engineers studied German maps made before World War I, when the Marianas (except Guam) were a German possession; they analyzed information found in the records of the Japanese Diet; and they interviewed people who had lived on Guam, since it was known that the terrain features of Guam and Saipan were similar. Unlike the flat coral islands to the east, the Marianas were of volcanic origin. Saipan, about twelve miles long and five wide, was mountainous, with a line of low peaks running in a north-south direction. (Map 24) The highest, Mount Tapotchau, near the center of the island, rose to an altitude of 1,554 feet. The eastern side of the island had steep wooded hills bordering the ocean. On the western side, the high points sloped gradually to level areas cultivated principally with sugarcane. On the western coast were two major towns, Garapan, the capital, to the north, and Charan Kanoa, to the south. The western side of the island was most promising for an amphibious assault. In late February the first photographs of Saipan, taken from carrier planes, came in. They were rather poor because many of the features were obscured by clouds and the flight lines were irregular.35

The most important construction mission in the Marianas was the building of airfields for the B-29’s. On Saipan and Guam, the engineers were to construct six runways for the long-range bombers. On Tinian, Navy engineers were to build six more with materials furnished by the Army. Runways were to be 8,500 feet long and surfaced with asphalt. Planning was involved and time consuming. After the planners in Hawaii had determined airfield requirements, they began estimating other construction needs, such as camps, hospitals, and warehouses. Kramer’s staff prepared construction annexes for the base development plan for Saipan, with layout plans showing the tentative location of all major installations to be built. Because of the few aerial photographs of the islands, the engineers had to make their layouts somewhat flexible. After Kramer’s engineers had completed their work on the Base Development Plan, they turned it over to Colonel Burns, who had served as head of the shore party on Kwajalein, and was to be garrison force engineer on Saipan. His staff prepared detailed designs and layout maps and computed supply requirements. Civilians from the Honolulu District office, aided by a special staff of officers, worked on the extensive engineer supply needs. The effectiveness of the Joint Staff had increased constantly; the Marianas operation was the first in which its new procedures were to be fully applied. For one thing, ships carrying supplies from the United States were to bypass the Hawaiian Islands and go directly to the Marianas. The engineers planned to send 150,000 ship tons to the islands by

October 1944 and 350,000 tons more by the following April. If supplies

Map 24: South Marianas

were sent directly from the United States, requisitions would have to be submitted to the ports of embarkation at least three months before the date the items were to be delivered. Very important was proper echeloning of the shipments. The engineer liaison officer at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation had the authority to load engineer cargo for each base as he thought necessary in order to fill engineer tonnage allowances. Meeting supply needs in the Marianas would not be easy because construction deadlines would require great quantities of materials at an early date. One weakness in planning persisted: task force commanders, after receiving their final directives, had too little time to finish their own planning and found that when they needed additional supplies, the items were almost impossible to get.36

Engineer troop requirements for Saipan were similar to those for Kwajalein. Although Saipan was considerably larger and enemy forces stationed there were estimated to total many thousands, Army troop requirements were not so

great as originally expected because the marines were to participate in the assault. As part of the 27th Division, the 02nd combat engineers, under Lt. Col. Harold F. Gormsen, their experiences on Makin and Eniwetok behind them, were scheduled to take part in the attack. Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the 1165th Combat Group, recently split off from the 34th Engineers when that unit was converted to a battalion, and commanded by Col. Horace L. Porter, was to supervise the shore party work of three combat battalions—the 34th, 1341st, and 152nd; all shore party personnel were attached to the 27th Division. After the assault phase of the operation, the shore party was to be transferred to the Saipan Garrison Force. It was believed that the terrain which would be encountered and the nature of the operation did not require bridging, topographic, depot, or maintenance units during the combat phase. Army engineer units of the garrison force would be directly under the Headquarters of the 1176th Construction Group, which had been formed from the 47th General Service Regiment when that unit was converted into a battalion. Colonel Burns, commander of the 1176th, was to be responsible to Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman, commander of the garrison force. Engineer units assigned to Burns’s command were principally aviation and construction battalions and elements of supply and maintenance companies.37

While headquarters staffs were engaged in planning, troop units were undergoing intensive training. The 102nd engineers were alerted for FORAGER in the latter part of February. They were given considerable training in attacking fortified positions; some of the men attended specialist schools. The three battalions selected for shore party operations were familiarized with unloading and storing supplies and in using demolitions; classroom instruction was followed by rehearsals at the beaches. Units assigned to the garrison force were trained in their specialties by working on construction jobs. The men worked with well-drilling rigs, hot-mix asphalt plants, and quarrying equipment; some got additional training in civilian shops and factories in Honolulu. To insure around-the-clock operations in the Marianas, extra operators were selected and trained on earth-moving and other construction equipment. Plans for base development could be prepared with greater accuracy in April, when l3-24’s operating from the newly constructed airfields in the Marshalls obtained complete photographic coverage of Saipan. By early May the base development plan was complete.38

The Assault on Saipan

Late in May a task force with the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions and the 27th Division sailed from Hawaii for the Marshalls. Somewhat earlier a similar force carrying the III Amphibious Corps, including the Marine 3rd Division and the 1st Provisional Brigade, had left Guadalcanal for the same destination.

The two fleets met near Kwajalein, the staging base for the operation. FORAGER was by far the largest assault yet undertaken in the Central Pacific. For Saipan alone, plans called for transporting 78,000 men and 100,000 tons of supplies from Hawaii. The Fifth Fleet, commanded by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, was the largest American naval force so far assembled in the Pacific. The combat engineers spent their time en route to the fighting zone in listening to orientation lectures, doing physical exercises, practicing loading and unloading supplies and equipment, and just relaxing. Meanwhile, planes and warships were pounding the island. “Saipan was smoking when we arrived. ...” wrote General Holland Smith.39

On 15 June the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions landed near Charan Kanoa. Enemy troops and defenses near the beaches were few. But the Japanese, skillfully using the guns they had emplaced on hills and in ravines farther back, put enough fire on the landing forces to hold them to a half-mile deep beachhead during the day. Early on the morning of the 17th, two regimental combat teams—the 105th and the 165th—of the 27th Division landed to the south of the Marine positions. Company A of the t 02nd engineers came ashore with the 105th; Company C, with the 165th. Again combat engineers and infantry had been organized into fighting teams. Each RCT came ashore with its company of engineers, part of which had been formed into assault groups, each consisting of one noncommissioned officer and five men. Three of the men carried satchel charges, one had a Browning automatic rifle, and one carried a flame thrower. The groups remained at or near company headquarters to be assigned to rifle platoons as needed. Engineer company and platoon headquarters had the job of bringing in reserve supplies of tools, equipment, explosives, Bangalore torpedoes, mine detectors, and liquid for flame throwers.

From the engineer standpoint, the beach defenses of southwestern Saipan were poor. They consisted for the most part of hastily constructed trenches and foxholes and a few log obstacles to stop tanks. In the advance toward the airfield, named Aslito, the combat engineers had to destroy only a few pillboxes, caves, and dugouts. Their biggest job was to find their supplies and equipment, dumped indiscriminately on the beaches and “hopelessly scattered.”40

One of the first tasks of the shore party engineers was to make a reconnaissance of the beaches. On the third day of the landing, at 0830, three officers and two enlisted men from headquarters of the 1165th Group set out on a survey of one of the beaches and its offshore coral reef to determine if it would be possible to unload palletized supplies from LCMs and LSTs, move them across the reef, and then have Alligators haul them from there to the beach. Ninety percent of the cargo and supplies of the 27th Division had been palletized. The reconnaissance party had a rough time. Caught in an enemy air raid and unable to return to their ship, the group had to

spend the night in an LCVP. “With our tow boat, we floated about until a Jap plane came into view and began strafing various boats around us,” the men reported in their diary. “We hopped into the tow boat and dodged about until the plane had gone, then returning to our own LCVP. There was much confusion and firing. Whenever one boat would open up at some target, fancied or otherwise, every other would join in and bullets were thick in the air.” Unloading began as planned but could be carried out only with difficulty. Dukws and Buffaloes, clambering over the reef, brought in the first supplies; landing craft with stores for all three divisions used a single narrow channel in the reef.41

Shore party operations in the 27th Division area were entirely under engineer control. The engineers were responsible for organizing the beachhead, selecting sites for dumps, hauling supplies to the dumps, and providing security. Men from other arms, naval beach parties, members of the Signal and Medical Corps, and other troops in the shore party area were subject to engineer shore party command. The plan was that supplies of all the arms and services would be landed at the appropriate beaches, near their dumps. But unloading was haphazard from the first. For the engineers it was almost disastrous. Units searched for days for their equipment; some items were never found. The chances were that construction on the airfield would not get started on time.42

The Japanese had begun too late to build up the island’s permanent defenses. At the time of the American landing, their program was only about 25 percent complete. “We found coastal defense guns up to 200 mm. crated, or uncrated and not installed, and large quantities of equipment and materiel waiting to be used,” General Smith wrote.43 The Japanese had, however, set up strong makeshift defenses by cleverly exploiting the natural features of the island. Artillery and mortars had been placed in advantageous positions in the mountains and trained on the roads and defiles leading inland. Army and Marine units pushed forward against stubborn and sometimes skillful resistance. Yet the defensive positions with which the engineers had to deal were few. The troops came across a number of pillboxes with sides of palm logs and roofs of sheet metal topped with sand. There were some blockhouses, generally with walls of weak concrete, 2½ to 4 feet thick, usually with 4 ports and mounts for 20-mm. guns. Most of the emplacements were either just finished or under construction. The combat engineers, sometimes with the help of shore party engineers, knocked out cave emplacements and pillboxes with demolitions and flame throwers. The few mines that were found revealed a “complete lack of thought” with regard to their

placement, concealment, and tactical use.44

By 18 June Aslito airfield, together with the southern part of the island except a pocket at Nafutan Point, was in American hands. The next day the 4th Marine Division reached Magicienne Bay on the eastern side of the island. The 2nd Marine Division was north of Garapan. The two divisions reformed their lines and advanced northward. Despite the makeshift Japanese defenses, it was apparent that the capture of Saipan would take longer than anticipated. Naval and military commanders held a conference on shipboard and decided to prepare for a three weeks’ campaign.

After Aslito airfield was captured, it was renamed Isley in memory of a naval aviator45 killed during one of the preliminary strikes on the island. On 19 June a naval construction battalion reached the field and began filling in craters and smoothing one of the runways. The next day a strip 4,500 feet long was usable. At this time the 804th Aviation Battalion, under Maj. John W. Paxton, arrived, having been delayed two days because of the unfavorable tactical situation and the haphazard unloading. The three LSTs carrying the battalion had beached on a coral reef, partly submerged at high tide, about 600 feet from shore. Heavy dozers were unloaded first. A roadway was smoothed over the reef and through shallow water to the bluff at the water’s edge; a blasting crew charged the bluff’s 50-foot-high face with dynamite. After blasting, dozers and carryalls completed a road up to the plateau of the island; construction equipment and personnel poured ashore “through chest-deep water.” The aviation engineers took over from the Seabees and continued improving the airfield for fighters. The men graded the shoulders and approach zones to make the strip safe for fighters and provided parking facilities for four squadrons of planes. They then began work on storage for aviation gasoline.46 The 804th engineers were the first of the units assigned to the 1176th Construction Group to reach Saipan. The advance echelon of group headquarters arrived on the 25th, and, under Colonel Burns, who had landed a week before, set up camp just west of Isley.47

As the Americans advanced northward, they came upon a series of cliffs and deep ravines, pitted with caves, from which the Japanese fought back stubbornly. The enemy, astride Mount Tapotchau, had a full view of the battlefield, which gave him a considerable advantage. Company B of the 102nd Combat Battalion was active around Mount Tapotchau. The men had a rough time. They had to reduce innumerable machine gun positions and neutralize a large

number of enemy caves. They used their bulldozers to close the mouths of caves which were so located that the machines could be used effectively. Sometimes the operators pushed dirt and other material down a slope over a cave entrance or inched their machines along a shelf of the hillside to the cave’s mouth. When the Japanese fired at approaching dozers, they aimed, as a rule, at the driver, protected by his armored cab and raised blade, instead of at the vulnerable parts of the engine. The engineers could reach some caves located in sheer cliffs only by following goat tracks on which enemy weapons were trained. They usually demolished these hideouts by lowering satchel charges from above, putting them in place in accordance with directions from observers stationed at a distance. After the explosion, the infantry went in with rifles, grenades, and flame throwers. Sometimes large charges were set off above the cave, causing the roof to collapse. The Japanese had laid their mine fields clumsily, without plan, and did not cover them with fire. A field of about seventy-five mines was discovered alongside a road near Mount Tapotchau. These mines, apparently laid in haste, were easily rendered harmless. A few booby traps were found near a radio station; poorly concealed, they were quickly deactivated.48

Base Construction on Saipan

As the enemy was being forced back, the work of transforming the island into a major base began. In General Jarman’s words, “I knew the primary job was to push the very long-range [bomber] program as rapidly as possible. There were three things we had to do. First, we had to build the strips for the Superfortresses; second, we had to have docks to unload the equipment to build the airstrips; third, we had to have the roads from the docks to the fields to bring the equipment. Everything else was secondary.”49

Work began first on the B-29 runway, to be 8,500 feet long and surfaced with asphalt. It was to be built at Isley. On 20 June, when the original Japanese runway was rehabilitated sufficiently to take fighters, work began on the B-29 runway. Survey parties of the 804th made experimental profiles to determine runway directions, sometimes under rifle fire. Intelligence reports had indicated the topsoil was about two feet deep, but it turned out to be only a few inches. Underneath was hard coral rock, which required much blasting. The aviation engineers used about five tons of dynamite a day. During the first week and a half, work was slowed by Japanese bombers overhead, usually at night. The engineers were forced to impose blackouts and all work stopped.50

Base development plans called for putting in a fighter field north of Charan Kanoa, where the Japanese had been at work on an airfield. Late in June the

805th aviation engineers, just in from Panama, surveyed the site. They regarded the area as unsuitable because of the strong cross winds and operational hazards. The local air force commander decided to build a field on the eastern side of the island at Kagman Point. On 3 July, when the enemy was cleared from the area, construction began. The engineers used their earth-moving equipment on a 24-hour basis, and on 8 July, they put the first coral from a nearby pit on the runway. Rapid progress had meanwhile been made on storage of aviation gasoline on Saipan. On i July the 804th Aviation Battalion began the rehabilitation of the Japanese storage facilities. Materials were beginning to arrive for the additional tanks to be constructed.51

The Japanese were being slowly forced back to the northern tip of the island. On 30 June a platoon of Company A, 102nd Combat Battalion, was attached to BLT 3 of the 105th Regimental Combat Team and continued the attack, using flame throwers and dynamiting caves and dugouts. Fighting was savage. U.S. troops suffered 25-percent casualties. The Japanese commander on Saipan ordered a last desperate counterattack for the night of 6-7 July. At 0300, the enemy attacked just north of Tanapag harbor. Armed with rifles, grenades, and knives, several thousand Japanese advanced shoulder to shoulder. They overran and wiped out two American infantry battalions and a number of field artillery units. “They came along the road adjacent to the beach about woo yards above the Tanapag seaplane base,” the 102nd Combat Battalion historian reported, “and kept pushing in and in. All the weapons of the BLTs were used to stop them, and as a last resort flame-throwers were used.” The attack lasted for two and a half hours. The first platoon of Company A, hit hard, lost several men killed and wounded in action. Some of the engineers, after firing their last rounds, escaped by swimming out to destroyers in the harbor. Many of the surviving Japanese committed suicide, as did the commander of the enemy garrison on the island. On 9 July organized resistance came to an end. There had been twenty-four days of fighting. A large number of Japanese had retreated to the caves and jungle of northern Saipan, where mop-up operations continued for months.52

With the island secure, work on airfields and base facilities progressed at a more rapid pace. Additional units of the 11 76th Construction Group arrived. Progress continued on the B-29 runway, but more slowly than had been expected. In some places the engineers had to cut coral down to a depth of fifteen feet; in others they had to fill as much as twenty-two feet. Good coral rock for the base course came from a quarry about two miles away. To speed up work, the men built a road from quarry to runway, to be used only by trucks hauling coral; stoplights at intersections gave the trucks the right of way at all times. To build this road, the engineers discontinued work on the runway for four days, but in about two days the increase in the amount of coral hauled made up for the

time spent on constructing the road. In building the runway, the engineers placed a coral base from twelve to eighteen inches deep. Asphalt for surfacing was produced at two plants located near the field. The rehabilitated Japanese runway crossed the B-29 strip near the middle. In order not to interfere with the flights of the fighter planes, the men worked on the two ends of the B-29 runway and left the fighter strip untouched in between. Heavy rains in July slowed construction somewhat. Drainage required little attention. The runways were constructed to drain to the shoulders, and from there the water percolated down through the coral. Early in July the 804th engineers began rehabilitation of the Japanese aviation gasoline fueling system. They had one of the tank farms in operation by the 12th; work on a second was under way.53

Working conditions on Saipan were not ideal. “Tropical downpours drenched the men, the heat was intense, water was scarce,” wrote war correspondent Clinton Green. The flies pressed unmercifully against sweaty bodies and had to be pried from one’s eyes, ears, and nostrils. Yet the work went on—twelve to eighteen hours a day.” There were heavy, almost continuous rains from the middle to the end of July, but by this time enemy air raids were becoming less frequent.54

The Army and Navy were jointly responsible for rehabilitating ports and harbors. The Army was charged with building piers and clearing areas for storing cargo; the Navy, for removing sunken ships and debris offshore and doing dredging. Saipan had one well-developed port—Tanapag, on the west coast, north of Garapan. A 200-foot-wide channel, 22 feet deep, led to three piers. The 47th engineers, organized as a construction battalion in April 1944, were slated to carry out the Army’s responsibilities at Tanapag. The unit arrived on 25 June and bivouacked in a cane field near Isley. Early in July, it moved to a hillside near Tanapag, prepared to work on docks and storage areas. Harbor facilities were a shambles. The three piers were wrecked. The 47th would have to repair them as quickly as possible. The northernmost one, an L-shaped structure built of large concrete blocks, with 200 feet of water along its northern face, appeared best suited for immediate repair. The other two were in water too shallow for American transports. The engineers could make all three suitable by lengthening them with floating piers. They began work by clearing debris from the L-shaped pier; the plan was to lengthen it to 570 feet and provide berthing facilities on both sides. The center pier could be similarly extended for about 460 feet. The third pier was to be improved with the construction of an 800-foot-long marginal pier, from which four floating finger piers were to be extended. When the engineers went to work, they found Japanese riflemen still present in the area. On the 10th of July guards posted by the 47th engineers on a dredge in Tanapag harbor found seven Japanese soldiers in the boiler room, and that same day two enemy soldiers were caught prowling in the 47th’s camp area. The presence of enemy soldiers, while somewhat

nerve-racking, did not slow construction.55

Saipan was to be not only an important air base but also an important supply, staging, and rehabilitation center. The number of installations was in-Creased so many times that the original base development plan had to be drastically revised. Extensive covered storage was required. Because of the danger of an enemy landing, the engineers at first built only small frame warehouses; some of this construction was done by troops from other arms and services, supplied with materials and supervised by the engineers. The larger warehouses, built later, were standardized structures 304 feet long, wo feet wide, and 16 feet high, designed to withstand winds with velocities up to 60 miles an hour. At the same time the engineers began work on hundreds of hardstands and igloos for ammunition. The main housing area for the troops was placed on the narrow coastal plain south of Isley. Pup tents or pyramidal tents with floors provided the first living quarters for the troops; these gradually gave way to prefabricated barracks and Quonset huts. The first hospitals, also, were in tents. Operating rooms were put in Quonset huts. Station and general hospitals of Quonset huts and prefabricated buildings were built around these operating rooms. Added later were water, sewer, and electric systems, air conditioning, asphalt roads, and concrete sidewalks. By the beginning of September, 6,000 beds were in Quonset huts or prefabricated buildings; 3,000 were still in tents.56

The roads on Saipan were in deplorable condition. The Japanese had built about fifty miles of roads, many of them not much better than oxcart trails. The one highway that could support American military traffic was the 20-foot-wide thoroughfare from Garapan to Charan Kanoa. During the fighting the roads almost disappeared. “Under the milling of thousands of feet and hundreds of heavy-tracked vehicles, the dirt roads had disintegrated into a fine, penetrating dust,” General Holland Smith observed, and added, possibly with some exaggeration, “a passing jeep could put up a smoke screen more effective than our chemical services could produce and blot out the sun. ...” “When it rained,” General Smith continued, “jeeps became amphibians caught in quagmires that had been roads a few hours before.”57 The engineers found it more profitable to build a new system of roads than to try to rehabilitate the old one. They built a perimeter road along the shores of the island and put in three main cross connections. They made most of the main roads thirty-two feet wide and paved them with coral. An unusual job was rehabilitating the railroad. A narrow-gauge line, which the Japanese used mainly for hauling sugarcane and military supplies, circled the island. The shore party engineers, soon after landing, went to work on it. They put one diesel and three steam locomotives back in use and repaired 100 flatcars. The 1398th Engineer Construction Battalion operated the railroad and by the end of July was hauling 350-ton miles a day on it.58 Since the railroad was not,

on the whole, a practical form of transportation, the tracks were taken up and a road built along the right of way. Two of the locomotives made excellent sterilizers for garbage cans.

The All-out effort on the airfields continued. By 6 August the engineers had extended the heavy bomber strip at Isley to 6,000 feet and had lengthened the B-29 runway to nearly 7,000. The hard coral, which required so much blasting, was still the principal hindrance to rapid construction. Heavy rains in August added to the problems. It had been hoped initially that a second B-29 field could be built on the west coast to the north of the field the Japanese had been building. The site looked good on aerial photographs, but it proved to be unsuitable because of extensive marshes; part of the area was below sea level. Reconnaissance indicated the second B-29 field could be built northwest of Isley. Construction was authorized, and the 1878th Engineer Aviation Battalion got the job of building the field. Storage tanks for aviation gasoline were being completed rapidly. The first job, the erection of four 5,000-gallon tanks, was finished on 12 July. The second—the erection of twelve 1,000-barrel tanks, begun on to July—was finished on 7 August. It would still be some time before the B-29 base would be completed.59

The Assaults on Guam and Tinian

While the Japanese were being mopped up on Saipan and airfield and base construction was well under way, preparations went ahead for the capture of Guam and Tinian. Plans had originally called for an assault on Guam on 18 June; when it was learned late on the first day of the landing on Saipan that a Japanese task force was headed for the Marianas, the assault was postponed indefinitely. After the defeat of the Japanese force in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, 19-24 June, preparations for Guam were further delayed by the stubborn resistance on Saipan. With the end of fighting on that island, preparations for the attack on Guam, and Tinian as well, were resumed.60 Plans now called for an attack on Guam on 21 July and on Tinian three days later. Marine units were to be mainly responsible for combat on both. The 3rd Marine Division, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, and the Army’s 77th Infantry Division, including the 302nd Engineer Combat Battalion, were to take Guam. The 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions would capture Tinian. Engineer combat and shore party units were to go into Guam, but only engineer shore party units would take part in the assault on Tinian.

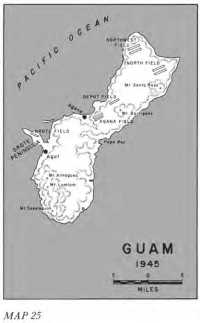

The 77th Division arrived off the west coast of Guam on 21 July; the marines had already secured beachheads to the north and south of Orote Peninsula. (Map 25) Early in the afternoon the 305th RCT, with part of the 302nd Combat Battalion, began to debark; the remaining elements of the division completed their landing by dusk. A lettered company had been attached to each of the division’s regimental combat teams. The landing was unopposed, since the preliminary bombardment had driven

Map 25: Guam

the Japanese away from the beaches. Some of the enemy returned during the night and attacked the American perimeter at a point held by a platoon of engineers. In hand-to-hand fighting, 18 Japanese and 3 engineers were killed. A combat group headquarters with three combat battalions, the 132nd, 233rd, and 242nd, arrived for shore party operations. Unloading of supplies and equipment was routine. The main hindrances were shortages of unloading gear and the troublesome fringing reef. Fortunately the Japanese made no determined attack at night when the beaches were flooded with light. The shore party engineers were subjected to only occasional enemy fire and had little contact with the enemy, though engineer and Japanese patrols sometimes clashed over water points.61

The plan of campaign called for uniting the two beachheads by capturing Orote Peninsula and then splitting the enemy forces with a drive eastward across the island to Pago Bay. As the troops moved inland, enemy resistance stiffened noticeably, but the Japanese could not stop the advance. After five days Orote Peninsula was captured. The 3rd Marine Division and the 77th Division then drove eastward to Pago Bay, getting possession of the one road across the island by 31 July. The 1st Provisional Brigade mopped up enemy positions on southern Guam.

The main job of the engineers on the southern part of the island was to keep the supply roads open. The terrain was rugged; beyond the beaches the ground rose in a series of hills and ridges; the soil, a reddish clay, was sticky when wet. Guards posted at critical points protected the work parties. The rapid advance of the infantry across the island made almost impossible the maintenance of the narrow existing roads with their thin surfaces of crushed coral. In building new roads, a route was first selected on foot or by jeep, a D-6 dozer leveled a two-lane width, and the excess dirt was then shoved aside. If time permitted and the tactical situation was sufficiently

Guam landing

stable, coral and rubble were hauled in for surfacing.62 “It is readily seen,” the 302nd engineers reported, “that the above system violated good road building practice. The road was in general below the surrounding ground, and side drainage was not provided for. As the road rutted, bulldozers shoved off the mud until a firm base was found farther down.”63 This system, apparently the best one possible in the deep clay of southern Guam, assured rapid supply of the division. The low parts of the road had to be filled in with logs or rocks.

The Japanese, as they withdrew to the northern plateau, put up a strong and skillful resistance. The 3rd Marine Division was on the right, the 77th Division on the left. The enemy concentrated his forces at the two peaks of Mount Santa Rosa and Mount Barrigada. Northern Guam was a limestone plateau about 400 feet above sea level. Except for Mount Santa Rosa and Mount Barrigada, it was gently rolling and offered excellent sites for airfields. On this part of the island, the combat engineers were engaged mainly in maintaining old roads and trails and building new ones. Here their task was somewhat easier than in the south because only about a foot of clay covered the

limestone. The jungle was heavy, but there were no streams. An engineer bulldozer operator, protected by his armored cab and closely supported by riflemen, usually moved ahead of each infantry column, opening a passageway through the dense growth. A second dozer, behind the first, widened the trail to 20 or 30 feet. Little work was needed on surfacing because the limestone base held up under all kinds of weather. Maintenance required only filling in shell craters and potholes, shaping up the crown, and, if necessary, constructing drainage ditches.64

Assault of fortified positions was a negligible task for the 302nd engineers on Guam. The only instance of demolition work was the destruction of an elaborate Japanese underground headquarters, which required three-quarters of a ton of TNT. On 10 August all organized enemy resistance was at an end. Mopping up continued, however, and for many months it was necessary to search for enemy troops entrenched in caves and in isolated mountain areas.65